User login

2014 Update on sexual dysfunction

Since the last installment of this Update on Sexual Dysfunction, three new drugs have been added to the armamentarium for menopausal symptoms and dyspareunia:

- paroxetine 7.5 mg (Brisdelle)

- conjugated estrogens and bazedoxifene (Duavee)

- ospemifene (Osphena).

In this article, I present a case-based approach to incorporating these drugs into practice and restoring sexual function in the setting of vulvovaginal atrophy and dyspareunia. As is often the case, decision-making requires sifting through multiple layers of information.

How to “tease out” the problem and help the patient regain sexual function

Simon JA, Portman DJ, Kazempour K, Mekonnen H, Bhaskar S, Lippman J. Safety profile of paroxetine 7.5 mg in women with moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(suppl 1):132S–133S.

Conjugated estrogens/bazedoxifene (Duavee) for menopausal symptoms and prevention of osteoporosis. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2014;56(1441):33–34.

DeGregorio MW, Zerbe RL, Wurz GT. Ospemifene: a first-in-class, non-hormonal selective estrogen receptor modulator approved for the treatment of dyspareunia associated with vulvar and vaginal atrophy [published online ahead of print August 1, 2014]. Steroids. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2014.07.012.

Goldstein SR, Archer DF, Simon JA, Constantine G. Endometrial safety of ospemifene and the ability of transvaginal ultrasonography to detect small changes in endometrial thickness. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(suppl 1):96S–97S.

CASE: LOW DESIRE AND DISCOMFORT DURING INTERCOURSE

Your 58-year-old patient, G2P2, mentions during her annual visit that she’s not that interested in sex anymore. Her children are grown, she’s been happily married for 28 years, and she enjoys her job and denies any symptoms of depression. She says her relationship with her husband is good and, aside from her low desire, she has no worries about the marriage. Her only medication is paroxetine 7.5 mg/day (Brisdelle) for management of her moderate hot flashes, which she initiated at her last annual visit. She reports improvement in her sleep and menopausal symptoms as a result. She has an intact uterus.

You perform a pelvic exam and find atrophic vulva and vagina with mild erythema, and thinned epithelium. When you ask if she has experienced any discomfort, she reports that she needs to use lubrication for intercourse and that, even with lubrication, she has pain upon penetration and a burning sensation that continues throughout intercourse. She also reports that it seems to take her much longer to achieve arousal than in the past, and she often fails to reach orgasm.

How would you manage this patient?

As always, begin with the history

The transition to menopause creates multiple layers of potential symptoms and problems for our patients, and sometimes medical therapy can generate additional ones.

In a patient reporting the onset of low desire and dyspareunia, you would want to first consider her medication history, despite the clear evidence of vaginal atrophy. Begin by asking whether she is taking any new medications prescribed by another provider. In some cases, antihypertensive drugs, psychotropic agents, and other medications can affect sexual function.

This patient has been taking Brisdelle for 1 year and is happy with its effect on her sleep and hot flashes. Simon and colleagues found this nonhormonal agent for moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms to produce no notable effects in weight, libido, or sleep, compared with placebo.

Nevertheless, in this case, because selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as paroxetine can affect arousal and orgasm, it is unclear whether the ultra-low dose of paroxetine she is taking is contributing to her problems. If you were to discontinue the drug to find out, her vasomotor symptoms and sleep disruption would likely recur.

Your decision-making is important here and should involve the patient in an extensive discussion. If there is not enough time for this discussion at the current visit, schedule a follow-up to address her issues fully.

Vulvovaginal atrophy has its own timeline

In many cases, vasomotor symptoms such as hot flashes occur years before the skin begins to atrophy in the vulva and vagina, particularly in women who enter menopause naturally. Among menopausal women who continue to have intercourse on a regular basis, however, these skin changes often are much less troublesome than they are for women who have sex more rarely.

In this patient, one possible scenario is that paroxetine caused a slight reduction in sexual interest, and the frequency of intercourse went down as a result. In women who have little or no intercourse, the vagina begins to shrink and the tissues lose elasticity. This patient may have been undergoing the natural process of menopause, and that process may have been compounded by a decrease in the frequency of sex.

If you were to discontinue the paroxetine, it would still be necessary to treat the vulvovaginal skin and work on manual techniques to gently dilate the introitus.

Option 1: Systemic hormone therapy

Systemic estrogen is the most effective treatment for menopausal vasomotor symptoms, reducing hot flashes by 50% to 100% within 4 weeks of initiation. However, because our patient has an intact uterus, any systemic estrogen she opts to use must be opposed by a progestin for safety reasons.

In terms of estrogen, her options are oral or nonoral formulations. Not only would estrogen manage our patient’s hot flashes but, over time, it would improve her sexual problems and atrophy, which might or might not improve her current complaint of low desire. You likely would need to add a short regimen of topical estrogen and perhaps even a dilator to restore her sexual function completely, however.

Since our patient chose the nonhormonal agent Brisdelle to manage her menopausal symptoms, she may be worried about the increased risk of breast cancer associated with use of a progestin in combination with estrogen. One hormonal option now available that eliminates the need for a progestin is conjugated estrogens and bazedoxefine (Duavee). Bazedoxefine is a third-

generation selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM). This drug has estrogen-like effects on bone and antiestrogen effects on the uterus.

Duavee is indicated for use in women with a uterus for treatment of:

- moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms of menopause

- prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis.

Among the risks are an increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and stroke. It is not approved specifically for the treatment of dyspareunia.

Another hormonal option is ospemifene (Osphena), an estrogen agonist/antagonist indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe dyspareunia in menopausal women. Among the drugs in its class, such as tamoxifen and raloxifene, ospemifene is the only agent that maintains a full estrogenic effect on vaginal tissues. Its risks include VTE and stroke.

Although the labeling includes a warning about the risk of endometrial hyperplasia associated with its use, Goldstein and colleagues found no significant difference in the rate of endometrial thickening greater than 5 mm between women taking ospemifene and those taking placebo after 1 year of daily oral treatment. No carcinomas were found in either group.

Option 2: Local estrogen

If our patient declines all systemic hormone therapy, the topical approach should resolve her vulvovaginal symptoms, and she could continue taking Brisdelle for her menopausal symptoms. Vaginal estrogen would address the skin problems, provided the patient applies it correctly. Many women are afraid to use estrogen creams and compensate by applying them only to the vulva, thinking that, by limiting their use to external tissues, they are avoiding any associated risks.

If she opts for the local approach, this patient should be encouraged to use transvaginal estrogen in small doses to increase the elasticity of the vulvovaginal tissue, even though it may require daily use for a week or two to improve her symptoms, after which once- or twice-weekly administration should suffice.

The use of low-dose vaginal cream for a short duration is unlikely to increase her risks in any way.

Local estrogen is available as a tablet, cream, or ring.

Option 3: A nonhormonal approach

If the patient refuses any hormonal agent—even topical estrogen—I would recommend the use of silicone-based lubricants and a dilator and prescribe more frequent penetration to increase elasticity and reduce pain.

Brisdelle could be continued to address her menopausal symptoms.

Don’t overlook behavioral techniques

Before this patient leaves your office with the option of her choice, a bit of counseling is necessary to instruct her about methods of restoring full sexual function.

Pain is a powerful aversive stimulus. This patient clearly states that she has had less frequent intercourse as a result of dyspareunia. It is not unusual for patients to develop a “habit” of avoidance in response to the behavior that causes their pain.

One recommendation is to talk to this patient about putting sex back into her life by encouraging her to increase sexual activity without penetration until she begins to arouse easily again. Arousal produces physiologic effects, increasing the caliber and length of the vagina as well as lubrication. The use of fingers or dilators may help restore caliber.

The patient can be encouraged to engage in snuggling and cuddling to regain those activities without the fear of pain associated with penetration. Follow-up after 2 weeks of this therapy can confirm the restoration of tissue elasticity, and the green light can be given for penetration to begin again. Couples can be encouraged to plan a “honeymoon weekend” and put some fun back into their sex lives so that this phase of healing doesn’t become an onerous task.

CASE RESOLVED After a discussion of her options, the patient chooses to stick with Brisdelle and use behavioral therapy alone to resolve her dyspareunia. At her follow-up visit 2 weeks later, she reports that she has enjoyed the period of pain-free “sex” and feels ready to add penetration into her activities.

You encourage her to continue sexual intercourse on a regular, relatively frequent basis to prevent a recurrence of dyspareunia. She continues to use silicone-based lubricants.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Since the last installment of this Update on Sexual Dysfunction, three new drugs have been added to the armamentarium for menopausal symptoms and dyspareunia:

- paroxetine 7.5 mg (Brisdelle)

- conjugated estrogens and bazedoxifene (Duavee)

- ospemifene (Osphena).

In this article, I present a case-based approach to incorporating these drugs into practice and restoring sexual function in the setting of vulvovaginal atrophy and dyspareunia. As is often the case, decision-making requires sifting through multiple layers of information.

How to “tease out” the problem and help the patient regain sexual function

Simon JA, Portman DJ, Kazempour K, Mekonnen H, Bhaskar S, Lippman J. Safety profile of paroxetine 7.5 mg in women with moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(suppl 1):132S–133S.

Conjugated estrogens/bazedoxifene (Duavee) for menopausal symptoms and prevention of osteoporosis. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2014;56(1441):33–34.

DeGregorio MW, Zerbe RL, Wurz GT. Ospemifene: a first-in-class, non-hormonal selective estrogen receptor modulator approved for the treatment of dyspareunia associated with vulvar and vaginal atrophy [published online ahead of print August 1, 2014]. Steroids. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2014.07.012.

Goldstein SR, Archer DF, Simon JA, Constantine G. Endometrial safety of ospemifene and the ability of transvaginal ultrasonography to detect small changes in endometrial thickness. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(suppl 1):96S–97S.

CASE: LOW DESIRE AND DISCOMFORT DURING INTERCOURSE

Your 58-year-old patient, G2P2, mentions during her annual visit that she’s not that interested in sex anymore. Her children are grown, she’s been happily married for 28 years, and she enjoys her job and denies any symptoms of depression. She says her relationship with her husband is good and, aside from her low desire, she has no worries about the marriage. Her only medication is paroxetine 7.5 mg/day (Brisdelle) for management of her moderate hot flashes, which she initiated at her last annual visit. She reports improvement in her sleep and menopausal symptoms as a result. She has an intact uterus.

You perform a pelvic exam and find atrophic vulva and vagina with mild erythema, and thinned epithelium. When you ask if she has experienced any discomfort, she reports that she needs to use lubrication for intercourse and that, even with lubrication, she has pain upon penetration and a burning sensation that continues throughout intercourse. She also reports that it seems to take her much longer to achieve arousal than in the past, and she often fails to reach orgasm.

How would you manage this patient?

As always, begin with the history

The transition to menopause creates multiple layers of potential symptoms and problems for our patients, and sometimes medical therapy can generate additional ones.

In a patient reporting the onset of low desire and dyspareunia, you would want to first consider her medication history, despite the clear evidence of vaginal atrophy. Begin by asking whether she is taking any new medications prescribed by another provider. In some cases, antihypertensive drugs, psychotropic agents, and other medications can affect sexual function.

This patient has been taking Brisdelle for 1 year and is happy with its effect on her sleep and hot flashes. Simon and colleagues found this nonhormonal agent for moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms to produce no notable effects in weight, libido, or sleep, compared with placebo.

Nevertheless, in this case, because selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as paroxetine can affect arousal and orgasm, it is unclear whether the ultra-low dose of paroxetine she is taking is contributing to her problems. If you were to discontinue the drug to find out, her vasomotor symptoms and sleep disruption would likely recur.

Your decision-making is important here and should involve the patient in an extensive discussion. If there is not enough time for this discussion at the current visit, schedule a follow-up to address her issues fully.

Vulvovaginal atrophy has its own timeline

In many cases, vasomotor symptoms such as hot flashes occur years before the skin begins to atrophy in the vulva and vagina, particularly in women who enter menopause naturally. Among menopausal women who continue to have intercourse on a regular basis, however, these skin changes often are much less troublesome than they are for women who have sex more rarely.

In this patient, one possible scenario is that paroxetine caused a slight reduction in sexual interest, and the frequency of intercourse went down as a result. In women who have little or no intercourse, the vagina begins to shrink and the tissues lose elasticity. This patient may have been undergoing the natural process of menopause, and that process may have been compounded by a decrease in the frequency of sex.

If you were to discontinue the paroxetine, it would still be necessary to treat the vulvovaginal skin and work on manual techniques to gently dilate the introitus.

Option 1: Systemic hormone therapy

Systemic estrogen is the most effective treatment for menopausal vasomotor symptoms, reducing hot flashes by 50% to 100% within 4 weeks of initiation. However, because our patient has an intact uterus, any systemic estrogen she opts to use must be opposed by a progestin for safety reasons.

In terms of estrogen, her options are oral or nonoral formulations. Not only would estrogen manage our patient’s hot flashes but, over time, it would improve her sexual problems and atrophy, which might or might not improve her current complaint of low desire. You likely would need to add a short regimen of topical estrogen and perhaps even a dilator to restore her sexual function completely, however.

Since our patient chose the nonhormonal agent Brisdelle to manage her menopausal symptoms, she may be worried about the increased risk of breast cancer associated with use of a progestin in combination with estrogen. One hormonal option now available that eliminates the need for a progestin is conjugated estrogens and bazedoxefine (Duavee). Bazedoxefine is a third-

generation selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM). This drug has estrogen-like effects on bone and antiestrogen effects on the uterus.

Duavee is indicated for use in women with a uterus for treatment of:

- moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms of menopause

- prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis.

Among the risks are an increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and stroke. It is not approved specifically for the treatment of dyspareunia.

Another hormonal option is ospemifene (Osphena), an estrogen agonist/antagonist indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe dyspareunia in menopausal women. Among the drugs in its class, such as tamoxifen and raloxifene, ospemifene is the only agent that maintains a full estrogenic effect on vaginal tissues. Its risks include VTE and stroke.

Although the labeling includes a warning about the risk of endometrial hyperplasia associated with its use, Goldstein and colleagues found no significant difference in the rate of endometrial thickening greater than 5 mm between women taking ospemifene and those taking placebo after 1 year of daily oral treatment. No carcinomas were found in either group.

Option 2: Local estrogen

If our patient declines all systemic hormone therapy, the topical approach should resolve her vulvovaginal symptoms, and she could continue taking Brisdelle for her menopausal symptoms. Vaginal estrogen would address the skin problems, provided the patient applies it correctly. Many women are afraid to use estrogen creams and compensate by applying them only to the vulva, thinking that, by limiting their use to external tissues, they are avoiding any associated risks.

If she opts for the local approach, this patient should be encouraged to use transvaginal estrogen in small doses to increase the elasticity of the vulvovaginal tissue, even though it may require daily use for a week or two to improve her symptoms, after which once- or twice-weekly administration should suffice.

The use of low-dose vaginal cream for a short duration is unlikely to increase her risks in any way.

Local estrogen is available as a tablet, cream, or ring.

Option 3: A nonhormonal approach

If the patient refuses any hormonal agent—even topical estrogen—I would recommend the use of silicone-based lubricants and a dilator and prescribe more frequent penetration to increase elasticity and reduce pain.

Brisdelle could be continued to address her menopausal symptoms.

Don’t overlook behavioral techniques

Before this patient leaves your office with the option of her choice, a bit of counseling is necessary to instruct her about methods of restoring full sexual function.

Pain is a powerful aversive stimulus. This patient clearly states that she has had less frequent intercourse as a result of dyspareunia. It is not unusual for patients to develop a “habit” of avoidance in response to the behavior that causes their pain.

One recommendation is to talk to this patient about putting sex back into her life by encouraging her to increase sexual activity without penetration until she begins to arouse easily again. Arousal produces physiologic effects, increasing the caliber and length of the vagina as well as lubrication. The use of fingers or dilators may help restore caliber.

The patient can be encouraged to engage in snuggling and cuddling to regain those activities without the fear of pain associated with penetration. Follow-up after 2 weeks of this therapy can confirm the restoration of tissue elasticity, and the green light can be given for penetration to begin again. Couples can be encouraged to plan a “honeymoon weekend” and put some fun back into their sex lives so that this phase of healing doesn’t become an onerous task.

CASE RESOLVED After a discussion of her options, the patient chooses to stick with Brisdelle and use behavioral therapy alone to resolve her dyspareunia. At her follow-up visit 2 weeks later, she reports that she has enjoyed the period of pain-free “sex” and feels ready to add penetration into her activities.

You encourage her to continue sexual intercourse on a regular, relatively frequent basis to prevent a recurrence of dyspareunia. She continues to use silicone-based lubricants.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Since the last installment of this Update on Sexual Dysfunction, three new drugs have been added to the armamentarium for menopausal symptoms and dyspareunia:

- paroxetine 7.5 mg (Brisdelle)

- conjugated estrogens and bazedoxifene (Duavee)

- ospemifene (Osphena).

In this article, I present a case-based approach to incorporating these drugs into practice and restoring sexual function in the setting of vulvovaginal atrophy and dyspareunia. As is often the case, decision-making requires sifting through multiple layers of information.

How to “tease out” the problem and help the patient regain sexual function

Simon JA, Portman DJ, Kazempour K, Mekonnen H, Bhaskar S, Lippman J. Safety profile of paroxetine 7.5 mg in women with moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(suppl 1):132S–133S.

Conjugated estrogens/bazedoxifene (Duavee) for menopausal symptoms and prevention of osteoporosis. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2014;56(1441):33–34.

DeGregorio MW, Zerbe RL, Wurz GT. Ospemifene: a first-in-class, non-hormonal selective estrogen receptor modulator approved for the treatment of dyspareunia associated with vulvar and vaginal atrophy [published online ahead of print August 1, 2014]. Steroids. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2014.07.012.

Goldstein SR, Archer DF, Simon JA, Constantine G. Endometrial safety of ospemifene and the ability of transvaginal ultrasonography to detect small changes in endometrial thickness. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(suppl 1):96S–97S.

CASE: LOW DESIRE AND DISCOMFORT DURING INTERCOURSE

Your 58-year-old patient, G2P2, mentions during her annual visit that she’s not that interested in sex anymore. Her children are grown, she’s been happily married for 28 years, and she enjoys her job and denies any symptoms of depression. She says her relationship with her husband is good and, aside from her low desire, she has no worries about the marriage. Her only medication is paroxetine 7.5 mg/day (Brisdelle) for management of her moderate hot flashes, which she initiated at her last annual visit. She reports improvement in her sleep and menopausal symptoms as a result. She has an intact uterus.

You perform a pelvic exam and find atrophic vulva and vagina with mild erythema, and thinned epithelium. When you ask if she has experienced any discomfort, she reports that she needs to use lubrication for intercourse and that, even with lubrication, she has pain upon penetration and a burning sensation that continues throughout intercourse. She also reports that it seems to take her much longer to achieve arousal than in the past, and she often fails to reach orgasm.

How would you manage this patient?

As always, begin with the history

The transition to menopause creates multiple layers of potential symptoms and problems for our patients, and sometimes medical therapy can generate additional ones.

In a patient reporting the onset of low desire and dyspareunia, you would want to first consider her medication history, despite the clear evidence of vaginal atrophy. Begin by asking whether she is taking any new medications prescribed by another provider. In some cases, antihypertensive drugs, psychotropic agents, and other medications can affect sexual function.

This patient has been taking Brisdelle for 1 year and is happy with its effect on her sleep and hot flashes. Simon and colleagues found this nonhormonal agent for moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms to produce no notable effects in weight, libido, or sleep, compared with placebo.

Nevertheless, in this case, because selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as paroxetine can affect arousal and orgasm, it is unclear whether the ultra-low dose of paroxetine she is taking is contributing to her problems. If you were to discontinue the drug to find out, her vasomotor symptoms and sleep disruption would likely recur.

Your decision-making is important here and should involve the patient in an extensive discussion. If there is not enough time for this discussion at the current visit, schedule a follow-up to address her issues fully.

Vulvovaginal atrophy has its own timeline

In many cases, vasomotor symptoms such as hot flashes occur years before the skin begins to atrophy in the vulva and vagina, particularly in women who enter menopause naturally. Among menopausal women who continue to have intercourse on a regular basis, however, these skin changes often are much less troublesome than they are for women who have sex more rarely.

In this patient, one possible scenario is that paroxetine caused a slight reduction in sexual interest, and the frequency of intercourse went down as a result. In women who have little or no intercourse, the vagina begins to shrink and the tissues lose elasticity. This patient may have been undergoing the natural process of menopause, and that process may have been compounded by a decrease in the frequency of sex.

If you were to discontinue the paroxetine, it would still be necessary to treat the vulvovaginal skin and work on manual techniques to gently dilate the introitus.

Option 1: Systemic hormone therapy

Systemic estrogen is the most effective treatment for menopausal vasomotor symptoms, reducing hot flashes by 50% to 100% within 4 weeks of initiation. However, because our patient has an intact uterus, any systemic estrogen she opts to use must be opposed by a progestin for safety reasons.

In terms of estrogen, her options are oral or nonoral formulations. Not only would estrogen manage our patient’s hot flashes but, over time, it would improve her sexual problems and atrophy, which might or might not improve her current complaint of low desire. You likely would need to add a short regimen of topical estrogen and perhaps even a dilator to restore her sexual function completely, however.

Since our patient chose the nonhormonal agent Brisdelle to manage her menopausal symptoms, she may be worried about the increased risk of breast cancer associated with use of a progestin in combination with estrogen. One hormonal option now available that eliminates the need for a progestin is conjugated estrogens and bazedoxefine (Duavee). Bazedoxefine is a third-

generation selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM). This drug has estrogen-like effects on bone and antiestrogen effects on the uterus.

Duavee is indicated for use in women with a uterus for treatment of:

- moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms of menopause

- prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis.

Among the risks are an increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and stroke. It is not approved specifically for the treatment of dyspareunia.

Another hormonal option is ospemifene (Osphena), an estrogen agonist/antagonist indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe dyspareunia in menopausal women. Among the drugs in its class, such as tamoxifen and raloxifene, ospemifene is the only agent that maintains a full estrogenic effect on vaginal tissues. Its risks include VTE and stroke.

Although the labeling includes a warning about the risk of endometrial hyperplasia associated with its use, Goldstein and colleagues found no significant difference in the rate of endometrial thickening greater than 5 mm between women taking ospemifene and those taking placebo after 1 year of daily oral treatment. No carcinomas were found in either group.

Option 2: Local estrogen

If our patient declines all systemic hormone therapy, the topical approach should resolve her vulvovaginal symptoms, and she could continue taking Brisdelle for her menopausal symptoms. Vaginal estrogen would address the skin problems, provided the patient applies it correctly. Many women are afraid to use estrogen creams and compensate by applying them only to the vulva, thinking that, by limiting their use to external tissues, they are avoiding any associated risks.

If she opts for the local approach, this patient should be encouraged to use transvaginal estrogen in small doses to increase the elasticity of the vulvovaginal tissue, even though it may require daily use for a week or two to improve her symptoms, after which once- or twice-weekly administration should suffice.

The use of low-dose vaginal cream for a short duration is unlikely to increase her risks in any way.

Local estrogen is available as a tablet, cream, or ring.

Option 3: A nonhormonal approach

If the patient refuses any hormonal agent—even topical estrogen—I would recommend the use of silicone-based lubricants and a dilator and prescribe more frequent penetration to increase elasticity and reduce pain.

Brisdelle could be continued to address her menopausal symptoms.

Don’t overlook behavioral techniques

Before this patient leaves your office with the option of her choice, a bit of counseling is necessary to instruct her about methods of restoring full sexual function.

Pain is a powerful aversive stimulus. This patient clearly states that she has had less frequent intercourse as a result of dyspareunia. It is not unusual for patients to develop a “habit” of avoidance in response to the behavior that causes their pain.

One recommendation is to talk to this patient about putting sex back into her life by encouraging her to increase sexual activity without penetration until she begins to arouse easily again. Arousal produces physiologic effects, increasing the caliber and length of the vagina as well as lubrication. The use of fingers or dilators may help restore caliber.

The patient can be encouraged to engage in snuggling and cuddling to regain those activities without the fear of pain associated with penetration. Follow-up after 2 weeks of this therapy can confirm the restoration of tissue elasticity, and the green light can be given for penetration to begin again. Couples can be encouraged to plan a “honeymoon weekend” and put some fun back into their sex lives so that this phase of healing doesn’t become an onerous task.

CASE RESOLVED After a discussion of her options, the patient chooses to stick with Brisdelle and use behavioral therapy alone to resolve her dyspareunia. At her follow-up visit 2 weeks later, she reports that she has enjoyed the period of pain-free “sex” and feels ready to add penetration into her activities.

You encourage her to continue sexual intercourse on a regular, relatively frequent basis to prevent a recurrence of dyspareunia. She continues to use silicone-based lubricants.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

As ICD-10 conversion nears, keep these factors in mind to ensure proper reimbursements in 2014

"I am working hard at my job to ensure high-volume gynecologic surgeons receive payment for services rendered," says Dr. Levy. Speaking at the PEP Practice Management Program at the 2013 Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery Symposium, held December 12-14, in Las Vegas, Dr. Levy offered attendees ways to ensure proper reimbursement for their services rendered.

In this video, Dr. Levy extends key points to viewers.

Related article: As the Affordable Care Act comes of age, a look behind the headlines (Lucia DiVenere, MA; January 2014)

"I am working hard at my job to ensure high-volume gynecologic surgeons receive payment for services rendered," says Dr. Levy. Speaking at the PEP Practice Management Program at the 2013 Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery Symposium, held December 12-14, in Las Vegas, Dr. Levy offered attendees ways to ensure proper reimbursement for their services rendered.

In this video, Dr. Levy extends key points to viewers.

Related article: As the Affordable Care Act comes of age, a look behind the headlines (Lucia DiVenere, MA; January 2014)

"I am working hard at my job to ensure high-volume gynecologic surgeons receive payment for services rendered," says Dr. Levy. Speaking at the PEP Practice Management Program at the 2013 Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery Symposium, held December 12-14, in Las Vegas, Dr. Levy offered attendees ways to ensure proper reimbursement for their services rendered.

In this video, Dr. Levy extends key points to viewers.

Related article: As the Affordable Care Act comes of age, a look behind the headlines (Lucia DiVenere, MA; January 2014)

UPDATE ON TECHNOLOGY

The development of new medical technology continues at a brisk pace—and ObGyns and our patients often are the beneficiaries. Notable technological breakthroughs of the past include hormonal contraception, in vitro fertilization, the application of minimally invasive surgical devices and techniques to gynecologic procedures, and many other innovations.

The leaders in our specialty are innovators themselves, ever vigilant for developments that can help improve health and quality of life for our patients. Regrettably, however, many technologies spread widely before they are fully validated by published studies—or continue to be used long after a superior or less invasive intervention has come along. And many claims about new technology are based on marketing information rather than reliable data.

Another common occurrence in regard to published data: Findings in one well-defined sector of the population are extrapolated to all patients. Even clinicians who are careful about adopting new technology can overlook the fact that it was tested, and proven, in a subset of patients that may not be comparable to all their patients.

In this article, I offer two case studies that illustrate some of the challenges we face when it comes to applying scientific findings to our practice and assessing medical technologies. In both settings, the health of the patient should be our primary focus.

When it comes to technology, patient selection is key

CASE 1: Anovulatory patient requests endometrial ablation

A 34-year-old woman (G2P2) who is moderately obese (body mass index of 32 kg/m2) visits your office to request endometrial ablation to manage her irregular and heavy menses. She reached menarche at age 10, and her periods have been somewhat irregular ever since. She required ovarian stimulation with clomiphene citrate to achieve each of her pregnancies, and both children were delivered by cesarean section. She currently uses condoms for contraception but does not have a steady partner, and she desires no additional pregnancies.

The patient reports that her menses occur every 2 to 6 weeks, with flow lasting from 2 to 8 days. She is housebound for 2 days each cycle because of heavy flow and cramping. She takes no medications and has no other medical conditions.

On exam, she is centrally obese with a tender uterus that is 10- to 12-weeks’ size; no adnexal masses are palpable. All other findings are normal. A recent test for diabetes was negative, but her serum cholesterol and triglyceride levels are borderline elevated.

What intervention would you recommend to address the heavy bleeding?

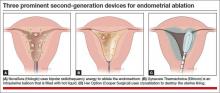

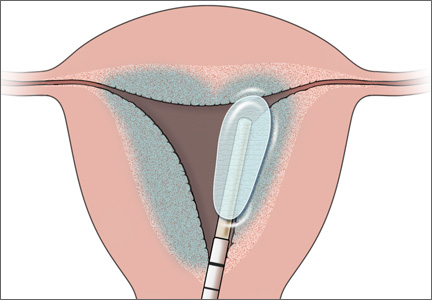

With the advent of second-generation endometrial ablation devices in the late 1990s, women with refractory menorrhagia had a safe, reliable, minimally invasive alternative to hysterectomy that made it possible to treat the endometrial cavity without the technical challenges of resectoscopic surgery. More than 10 million women report menorrhagia each year in the United States—so it is no small problem.1,2 Global endometrial ablation devices make management possible in an office setting, and recovery is significantly shorter than with hysterectomy. The three most prominent nonhysteroscopic ablation devices are (FIGURE):

• NovaSure (Hologic) uses bipolar radiofrequency energy to ablate tissue. Its probe contains stretchable gold-plated fabric that conforms to the endometrial surface.

• Gynecare Thermachoice (Ethicon) consists of an intrauterine balloon that is filled with hot liquid (temperatures of roughly 87°C) to ablate the endometrium

• Her Option (CooperSurgical) is a cryoablation system that consists of an intrauterine probe that forms an ice ball (temperatures of roughly –90°C) that destroys the uterine lining. Several applications are required to treat the majority of the cavity.

Use of these devices is widespread, although a nonsurgical alternative—the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS; Mirena)—was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2009 for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding.

Not only is the efficacy of the LNG-IUS for controlling menorrhagia equal to endometrial ablation, but it provides the additional benefits of reliable contraception and management of dysmenorrhea.

6 questions to ask before applying a technology

1. In which population was it studied?

One of the most important issues to consider when you are evaluating technology is the population in which it was studied. In other words, to whom do the findings apply?

Most endometrial ablation technologies were tested in women who had a uterus of normal size (mean, 8 cm) with no structural abnormalities (ie, no polyps or fibroids) and regular but very heavy periods. The findings from these studies now have been extrapolated in many cases to women who have hormonally induced abnormal bleeding, whose periods are irregular. That extrapolation may not be appropriate.

2. What is the diagnosis?

As the manufacturers of global endometrial ablation devices note, heavy menstrual bleeding may arise from an underlying condition, such as endometrial cancer, hormonal imbalance, fibroids, coagulopathy, and so on—and it is important to rule these conditions out before considering endometrial ablation.

For example, in Case 1, the patient is experiencing anovulatory cycles, as evidenced by her irregular menses and the need for ovulation induction to achieve her pregnancies. The success rate of endometrial ablation in the setting of chronic anovulation is unknown. Pivotal trials for all of the nonhysteroscopic endometrial ablation technologies required regular menses or failure of cyclic hormonal therapy prior to enrollment.

In addition, in Case 1, the patient has signs (an enlarged, tender uterus) that suggest the presence of adenomyosis. Endometrial ablation is not recommended as a treatment for women with this condition.

3. Will later surgery be required?

In one study from Kaiser Permanente of Northern California, 21% of women who underwent endometrial ablation for menorrhagia later underwent hysterectomy, and 3.9% underwent other uterine-sparing procedures to alleviate heavy bleeding.3

In that study, women younger than age 45 were 2.1 times more likely to require hysterectomy after endometrial ablation, compared with older women (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.8–2.4). The likelihood of hysterectomy increased with each decreasing stratum of age and exceeded 40% in women aged 40 years or younger.3

In a population-based retrospective cohort study from Scotland, 2,779 (19.7%) of 11,299 women who underwent endometrial ablation for heavy menstrual bleeding required hysterectomy later.4 Again, women who required hysterectomy after endometrial ablation tended to be younger than those who did not. Overall, 26.6% of women undergoing endometrial ablation for heavy menstrual bleeding required further surgery.4

And in a 5-year follow-up of patients participating in a randomized trial of uterine balloon therapy versus rollerball ablation, roughly 30% of women required subsequent surgery for heavy menstrual bleeding.5

The need for subsequent surgery following endometrial ablation is likely to be higher among women who do not match the profile of participants in pivotal trials of the devices. All patients considering endometrial ablation should be counseled about the possible need for further surgery.

Related Article The economics of surgical gynecology: How we can not only survive, but thrive, in the 21st Century Barbara S. Levy, MD

4. What is the patient's overall health?

Before selecting an intervention for heavy menstrual bleeding, it is important to consider the patient’s overall health. What comorbidities does she have? Is pain a component of her condition? If so, might she have endometriosis or adenomyosis, as our patient does? If pain is a significant component of her menorrhagia, is it cyclical—that is, does it correspond to the days of heaviest flow? Pain related to the passage of large clots during menses may respond well to endometrial ablation. Pelvic pain occurring before and after the flow probably won’t.

Also keep in mind that the patient in Case 1 has two risk factors for endometrial hyperplasia: anovulatory cycles and obesity. If she undergoes endometrial ablation and subsequently experiences abnormal uterine bleeding, the most prominent sign of endometrial hyperplasia, how will you assess her endometrium 5 years after ablation if she develops abnormal bleeding? Will you be able to adequately sample it?

5. Have less invasive options been tried?

Many of the women studied in pivotal trials of second-generation endometrial ablation devices failed medical therapy prior to undergoing ablation. Because medical therapy is less expensive and noninvasive, it makes sense to offer it before proceeding to surgery. Common pharmacologic approaches include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), oral contraceptives, and tranexamic acid.

In addition, as I mentioned earlier, Mirena is approved for treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding.

Medical therapy and Mirena should be offered prior to surgery because of their noninvasive, reversible nature. Most physicians now consider Mirena to be the first-line option for heavy menstrual bleeding in women who have normal anatomy.6

6. What is the cost of treatment?

With health-care expenses accelerating, we need to be mindful of the cost-effectiveness of the options we recommend.

Let’s assess the expense of managing the patient in Case 1. To address her desire for long-term contraception, we might offer tubal sterilization by laparoscopy followed by endometrial ablation (to address the heavy bleeding), which would require a general anesthetic and management in an ambulatory surgical facility.

If she opts for hysteroscopic sterilization prior to endometrial ablation, the sterilization procedure must be performed at least 3 months prior to ablation (according to FDA labeling) so that tubal occlusion can be demonstrated by hysterosalpingography (HSG) before the uterine cavity is scarred. This means that the patient would require two separate interventions. Although both procedures could be performed in an office setting, the patient would still require time away from work and family.

The cost for sterilization plus ablation in the office without anesthesia would be approximately $4,500 (including HSG) at Medicare rates. For a combined laparoscopic sterilization and endometrial ablation, costs would be higher because of the need for anesthesia and an ambulatory surgical facility. Another option that would address both the heavy bleeding and the need for contraception: oral contraceptives (OCs). The overall cost of this approach over 5 years would be $4,200 (60 months of OCs at $70/month), but it would be fully covered under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), so the patient would have no out-of-pocket expense. The cost of Mirena would be $1,000 ($850 for the device plus $150 for insertion), but it also would be fully covered under the ACA.

CASE 1: Resolved

You discuss the option of cyclic OCs with the patient. This approach would help control her irregular, heavy, and painful menses while providing good contraceptive coverage.

Although sterilization plus endometrial ablation is an option, you counsel the patient that the published “success” rates do not apply to her. Given her young age, obesity, and anovulatory status, endometrial ablation has a greater likelihood of failure. Further, when abnormal bleeding recurs, it may be difficult to assess this high-risk patient’s endometrium.

You also discuss Mirena, which would provide long-term contraception and also manage her menorrhagia and dysmenorrhea; indeed, it is FDA-approved for this indication. In fact, Mirena would address all of this patient’s concerns, offering superb contraception and reliable reductions in bleeding and pelvic pain in the setting of endometriosis and adenomyosis.

Overall, this woman is best served by a highly reliable approach that manages her contraceptive needs and her menorrhagia and dysmenorrhea while reducing her risk for endometrial hyperplasia and cancer. Given the long-term endometrial-sampling problems ablation would create, it is not an optimal solution for this woman.

What this evidence means for practice

When assessing technology, consider which patients it was tested in, your patient’s diagnosis and long-term health risks, the cost and success rate of the technology, and the availability of less invasive options.

How to assess new data on a technology or procedure

Gill SE, Mills BB. Physician opinions regarding elective bilateral salpingectomy with hysterectomy and for sterilization. JMIG. 2013;20(4):517–521.

CASE 2: A healthy patient seeks permanent contraception

At her annual well-woman visit, your 42-year-old patient (G3P3) asks to discuss permanent contraception now that she has completed her family. She has used OCs for more than 10 years without problems. She is a nonsmoker of normal weight (BMI of 22 kg/m2), with normal blood pressure and vital signs. Her family history is remarkable for the health of her parents and siblings: Her mother is 68 years old and well; her father, 70, also is healthy. There is no family history of breast or ovarian cancer, prostate cancer, or significant medical illness.

What options would you offer this patient? Given recent data suggesting that ovarian cancer may originate in the fallopian tubes, would you recommend prophylactic salpingectomy as her contraceptive method of choice?

This patient has many options. In describing them to her, it would be important to focus on the breadth of safe, reversible, long-acting contraceptives now available, including their respective risks, benefits, and long-term outcomes and costs. It also is important to consider the published data on these methods, weighing their relevance to her overall health and medical history. Although some data regarding the origin of ovarian cancer in the fallopian tubes may be especially compelling, it may not be wise to extrapolate it from a specific group of women to all patients, as we shall see.

Option 1: Cyclic OCs

This option should not be excluded, despite the need for daily dosing, because the patient has used it successfully for more than 10 years. OCs are highly effective and have the added benefits of reducing menstrual blood loss, alleviating cramps, and lowering the risks of endometrial and ovarian cancer.7

Option 2: LARC

Long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods include the LNG-IUS, the copper intrauterine device (IUD; ParaGard, Teva), and the etonogestrel implant (Nexplanon, Merck). Each of these contraceptives is similar to sterilization in terms of efficacy. None requires the interruption of sexual activity or weekly or monthly trips to the pharmacy.

The LNG-IUS and the etonogestrel implant have the added benefits of reducing menstrual blood loss and reducing or eliminating premenstrual symptoms and cramps in most women. In addition, they may reduce the risk of unopposed estrogen stimulation of the endometrium associated with perimenopausal anovulatory cycles.

Option 3: Transcervical tubal sterilization

This hysteroscopic method (Essure, Bayer) avoids the risks of general anesthesia, but successful bilateral placement may not be possible in a small percentage of women. It also requires a 3-month interval between placement and confirmation of tubal occlusion (via HSG). During this interval, alternative contraception must be used. Once occlusion is confirmed, this method is highly reliable.

Option 4: Laparoscopic sterilization

This approach was the method of choice prior to the introduction of Essure in 2002. There now is a resurgence of interest in laparoscopic sterilization due to recent publications describing the distal portion of the fallopian tube as the “true source” of high-grade serous ovarian cancers.

In pathologic analyses of fallopian tubes removed prophylactically from women with a BRCA 1 or 2 mutation, investigators found a significant rate of serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma.8 Researchers began to study the genetics of these cancers and concluded that, in women with a BRCA mutation, high-grade serous carcinomas may arise from the distal fallopian tube.

Until recently, all of the literature on these tubal carcinomas related only to women with a specific tumor suppressor gene p53 mutation in the BRCA system. Other investigators then reviewed pathology specimens from women without a BRCA mutation who had high-grade serous carcinomas that were peritoneal, tubal, or ovarian in origin. They found serous tubal intraepithelial carcinomas in 33% to 59% of these women.9

“Research suggests that bilateral salpingectomy during hysterectomy for benign indications or as a sterilization procedure may have benefits, such as preventing tubal disease and cancer, without significant risks,” wrote Gill and Mills.10 In conducting a survey of US physicians to determine how widespread prophylactic salpingectomy is during benign hysterectomy or sterilization, they found that 54% of respondents performed bilateral salpingectomy during hysterectomy, usually to lower the risk of cancer (75%) and avoid the need for reoperation (49.1%). Of the 45.5% of respondents who did not perform bilateral salpingectomy during hysterectomy, most (69.4%) believed it has no benefit.10

Although 58% of respondents believed bilateral salpingectomy to be the most effective option for sterilization in women older than 35 years, they reported that they reserve it for women in whom one sterilization procedure has failed or for women who have tubal disease.10

As for the 45.5% of respondents who did not perform prophylactic salpingectomy, they offered as reasons their concern about increased operative time and the risk of complications, as well as a belief that it has no benefit.10

The lifetime risk of ovarian cancer in the general population is 1 in 70 women. Although it is possible that high-grade serous ovarian cancers originate in the distal fallopian tube, as the research to date suggests, it also is possible that we might find in-situ lesions in tissues other than the distal tube, suggesting a more global genetic defect underlying ovarian cancers in the peritoneal and müllerian tissues. Randomized trials are under way in an effort to determine whether excision of the fallopian tubes will prevent the majority of high-grade serous cancers. It will be many years, however, before the results of these trials are available.

CASE 2: Resolved

This patient has used combination OCs for more than 10 years, so her lifetime risk of ovarian cancer has been reduced by approximately 50%. Because her family history indicates that a BRCA mutation is highly unlikely, her lifetime risk of ovarian cancer now has declined from 1:70 to roughly 1:140.

Prophylactic salpingectomy might offer a very small reduction in this patient’s absolute risk of ovarian cancer—from 0.75% to 0.50% lifetime risk—but the current data are not robust enough to suggest that it should be recommended for her. The operation would carry the risks associated with general anesthesia and peritoneal access. Although these risks are small, there is a documented risk of death from laparoscopic sterilization procedures in the United States, from complications related to bowel injury, anesthesia, and hemorrhage.

For these reasons, I would counsel this patient that her best options for contraception are combination OCs, transcervical tubal sterilization, or a long-acting reversible contraceptive such as the IUD or implant.

Tell us what you think, at [email protected]. Please include your name and city and state.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Blood disor-ders in women: heavy menstrual bleeding. http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/blooddisorders/women/menorrhagia.html. Updated December 12, 2011. Accessed August 15, 2013.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Blood disorders in women: research. http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/blooddis orders/women/research.html. Updated December 12, 2011. Accessed August 15, 2013.

3. Longinotti K, Jacobson GF, Hung YY, Learman LA. Probability of hysterectomy after endometrial ablation. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(6):1214–1220.

4. Cooper K, Lee AJ, Chien P, Raja EA, Timmaraju V, Bhattacharya S. Outcomes following hysterectomy or endometrial ablation for heavy menstrual bleeding: retrospective analysis of hospital episode statistics in Scotland. BJOG. 2011;118(10):1171–1179.

5. Loffer FD, Grainger D. Five-year follow-up of patients participating in a randomized trial of uterine balloon therapy versus rollerball ablation for treatment of menorrhagia. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2002;9(4):429–435.

6. Sayre C. Beyond hysterectomy: Alternative options for heavy bleeding. NY Times. http://www.nytimes.com/ref/health/healthguide/esn-menorrhagia-ess.html. Published October 10, 2008. Accessed August 15, 2013.

7. Havrilesky LJ, Moorman PG, Lowery WJ, et al. Oral contraceptive pills as primary prevention for ovarian cancer. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(1):139–147.

8. Kindelberger DW, Lee Y, Miron A, et al. Intraepithelial carcinoma of the fimbria and pelvic serous carcinoma: evidence for a causal relationship. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007; 31:161–169.

9. Crum CP, McKeon FD, Xian W. The oviduct and ovarian cancer: causality, clinical implications, and “targeted prevention.” Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2012;55(1):24–35.

10. Gill SE, Mills BB. Physician opinions regarding elective bilateral salpingectomy with hysterectomy and for sterilization. JMIG. 2013;20(4):517–521.

The development of new medical technology continues at a brisk pace—and ObGyns and our patients often are the beneficiaries. Notable technological breakthroughs of the past include hormonal contraception, in vitro fertilization, the application of minimally invasive surgical devices and techniques to gynecologic procedures, and many other innovations.

The leaders in our specialty are innovators themselves, ever vigilant for developments that can help improve health and quality of life for our patients. Regrettably, however, many technologies spread widely before they are fully validated by published studies—or continue to be used long after a superior or less invasive intervention has come along. And many claims about new technology are based on marketing information rather than reliable data.

Another common occurrence in regard to published data: Findings in one well-defined sector of the population are extrapolated to all patients. Even clinicians who are careful about adopting new technology can overlook the fact that it was tested, and proven, in a subset of patients that may not be comparable to all their patients.

In this article, I offer two case studies that illustrate some of the challenges we face when it comes to applying scientific findings to our practice and assessing medical technologies. In both settings, the health of the patient should be our primary focus.

When it comes to technology, patient selection is key

CASE 1: Anovulatory patient requests endometrial ablation

A 34-year-old woman (G2P2) who is moderately obese (body mass index of 32 kg/m2) visits your office to request endometrial ablation to manage her irregular and heavy menses. She reached menarche at age 10, and her periods have been somewhat irregular ever since. She required ovarian stimulation with clomiphene citrate to achieve each of her pregnancies, and both children were delivered by cesarean section. She currently uses condoms for contraception but does not have a steady partner, and she desires no additional pregnancies.

The patient reports that her menses occur every 2 to 6 weeks, with flow lasting from 2 to 8 days. She is housebound for 2 days each cycle because of heavy flow and cramping. She takes no medications and has no other medical conditions.

On exam, she is centrally obese with a tender uterus that is 10- to 12-weeks’ size; no adnexal masses are palpable. All other findings are normal. A recent test for diabetes was negative, but her serum cholesterol and triglyceride levels are borderline elevated.

What intervention would you recommend to address the heavy bleeding?

With the advent of second-generation endometrial ablation devices in the late 1990s, women with refractory menorrhagia had a safe, reliable, minimally invasive alternative to hysterectomy that made it possible to treat the endometrial cavity without the technical challenges of resectoscopic surgery. More than 10 million women report menorrhagia each year in the United States—so it is no small problem.1,2 Global endometrial ablation devices make management possible in an office setting, and recovery is significantly shorter than with hysterectomy. The three most prominent nonhysteroscopic ablation devices are (FIGURE):

• NovaSure (Hologic) uses bipolar radiofrequency energy to ablate tissue. Its probe contains stretchable gold-plated fabric that conforms to the endometrial surface.

• Gynecare Thermachoice (Ethicon) consists of an intrauterine balloon that is filled with hot liquid (temperatures of roughly 87°C) to ablate the endometrium

• Her Option (CooperSurgical) is a cryoablation system that consists of an intrauterine probe that forms an ice ball (temperatures of roughly –90°C) that destroys the uterine lining. Several applications are required to treat the majority of the cavity.

Use of these devices is widespread, although a nonsurgical alternative—the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS; Mirena)—was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2009 for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding.

Not only is the efficacy of the LNG-IUS for controlling menorrhagia equal to endometrial ablation, but it provides the additional benefits of reliable contraception and management of dysmenorrhea.

6 questions to ask before applying a technology

1. In which population was it studied?

One of the most important issues to consider when you are evaluating technology is the population in which it was studied. In other words, to whom do the findings apply?

Most endometrial ablation technologies were tested in women who had a uterus of normal size (mean, 8 cm) with no structural abnormalities (ie, no polyps or fibroids) and regular but very heavy periods. The findings from these studies now have been extrapolated in many cases to women who have hormonally induced abnormal bleeding, whose periods are irregular. That extrapolation may not be appropriate.

2. What is the diagnosis?

As the manufacturers of global endometrial ablation devices note, heavy menstrual bleeding may arise from an underlying condition, such as endometrial cancer, hormonal imbalance, fibroids, coagulopathy, and so on—and it is important to rule these conditions out before considering endometrial ablation.

For example, in Case 1, the patient is experiencing anovulatory cycles, as evidenced by her irregular menses and the need for ovulation induction to achieve her pregnancies. The success rate of endometrial ablation in the setting of chronic anovulation is unknown. Pivotal trials for all of the nonhysteroscopic endometrial ablation technologies required regular menses or failure of cyclic hormonal therapy prior to enrollment.

In addition, in Case 1, the patient has signs (an enlarged, tender uterus) that suggest the presence of adenomyosis. Endometrial ablation is not recommended as a treatment for women with this condition.

3. Will later surgery be required?

In one study from Kaiser Permanente of Northern California, 21% of women who underwent endometrial ablation for menorrhagia later underwent hysterectomy, and 3.9% underwent other uterine-sparing procedures to alleviate heavy bleeding.3

In that study, women younger than age 45 were 2.1 times more likely to require hysterectomy after endometrial ablation, compared with older women (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.8–2.4). The likelihood of hysterectomy increased with each decreasing stratum of age and exceeded 40% in women aged 40 years or younger.3

In a population-based retrospective cohort study from Scotland, 2,779 (19.7%) of 11,299 women who underwent endometrial ablation for heavy menstrual bleeding required hysterectomy later.4 Again, women who required hysterectomy after endometrial ablation tended to be younger than those who did not. Overall, 26.6% of women undergoing endometrial ablation for heavy menstrual bleeding required further surgery.4

And in a 5-year follow-up of patients participating in a randomized trial of uterine balloon therapy versus rollerball ablation, roughly 30% of women required subsequent surgery for heavy menstrual bleeding.5

The need for subsequent surgery following endometrial ablation is likely to be higher among women who do not match the profile of participants in pivotal trials of the devices. All patients considering endometrial ablation should be counseled about the possible need for further surgery.

Related Article The economics of surgical gynecology: How we can not only survive, but thrive, in the 21st Century Barbara S. Levy, MD

4. What is the patient's overall health?

Before selecting an intervention for heavy menstrual bleeding, it is important to consider the patient’s overall health. What comorbidities does she have? Is pain a component of her condition? If so, might she have endometriosis or adenomyosis, as our patient does? If pain is a significant component of her menorrhagia, is it cyclical—that is, does it correspond to the days of heaviest flow? Pain related to the passage of large clots during menses may respond well to endometrial ablation. Pelvic pain occurring before and after the flow probably won’t.

Also keep in mind that the patient in Case 1 has two risk factors for endometrial hyperplasia: anovulatory cycles and obesity. If she undergoes endometrial ablation and subsequently experiences abnormal uterine bleeding, the most prominent sign of endometrial hyperplasia, how will you assess her endometrium 5 years after ablation if she develops abnormal bleeding? Will you be able to adequately sample it?

5. Have less invasive options been tried?

Many of the women studied in pivotal trials of second-generation endometrial ablation devices failed medical therapy prior to undergoing ablation. Because medical therapy is less expensive and noninvasive, it makes sense to offer it before proceeding to surgery. Common pharmacologic approaches include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), oral contraceptives, and tranexamic acid.

In addition, as I mentioned earlier, Mirena is approved for treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding.

Medical therapy and Mirena should be offered prior to surgery because of their noninvasive, reversible nature. Most physicians now consider Mirena to be the first-line option for heavy menstrual bleeding in women who have normal anatomy.6

6. What is the cost of treatment?

With health-care expenses accelerating, we need to be mindful of the cost-effectiveness of the options we recommend.

Let’s assess the expense of managing the patient in Case 1. To address her desire for long-term contraception, we might offer tubal sterilization by laparoscopy followed by endometrial ablation (to address the heavy bleeding), which would require a general anesthetic and management in an ambulatory surgical facility.

If she opts for hysteroscopic sterilization prior to endometrial ablation, the sterilization procedure must be performed at least 3 months prior to ablation (according to FDA labeling) so that tubal occlusion can be demonstrated by hysterosalpingography (HSG) before the uterine cavity is scarred. This means that the patient would require two separate interventions. Although both procedures could be performed in an office setting, the patient would still require time away from work and family.

The cost for sterilization plus ablation in the office without anesthesia would be approximately $4,500 (including HSG) at Medicare rates. For a combined laparoscopic sterilization and endometrial ablation, costs would be higher because of the need for anesthesia and an ambulatory surgical facility. Another option that would address both the heavy bleeding and the need for contraception: oral contraceptives (OCs). The overall cost of this approach over 5 years would be $4,200 (60 months of OCs at $70/month), but it would be fully covered under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), so the patient would have no out-of-pocket expense. The cost of Mirena would be $1,000 ($850 for the device plus $150 for insertion), but it also would be fully covered under the ACA.

CASE 1: Resolved

You discuss the option of cyclic OCs with the patient. This approach would help control her irregular, heavy, and painful menses while providing good contraceptive coverage.

Although sterilization plus endometrial ablation is an option, you counsel the patient that the published “success” rates do not apply to her. Given her young age, obesity, and anovulatory status, endometrial ablation has a greater likelihood of failure. Further, when abnormal bleeding recurs, it may be difficult to assess this high-risk patient’s endometrium.

You also discuss Mirena, which would provide long-term contraception and also manage her menorrhagia and dysmenorrhea; indeed, it is FDA-approved for this indication. In fact, Mirena would address all of this patient’s concerns, offering superb contraception and reliable reductions in bleeding and pelvic pain in the setting of endometriosis and adenomyosis.

Overall, this woman is best served by a highly reliable approach that manages her contraceptive needs and her menorrhagia and dysmenorrhea while reducing her risk for endometrial hyperplasia and cancer. Given the long-term endometrial-sampling problems ablation would create, it is not an optimal solution for this woman.

What this evidence means for practice

When assessing technology, consider which patients it was tested in, your patient’s diagnosis and long-term health risks, the cost and success rate of the technology, and the availability of less invasive options.

How to assess new data on a technology or procedure

Gill SE, Mills BB. Physician opinions regarding elective bilateral salpingectomy with hysterectomy and for sterilization. JMIG. 2013;20(4):517–521.

CASE 2: A healthy patient seeks permanent contraception

At her annual well-woman visit, your 42-year-old patient (G3P3) asks to discuss permanent contraception now that she has completed her family. She has used OCs for more than 10 years without problems. She is a nonsmoker of normal weight (BMI of 22 kg/m2), with normal blood pressure and vital signs. Her family history is remarkable for the health of her parents and siblings: Her mother is 68 years old and well; her father, 70, also is healthy. There is no family history of breast or ovarian cancer, prostate cancer, or significant medical illness.

What options would you offer this patient? Given recent data suggesting that ovarian cancer may originate in the fallopian tubes, would you recommend prophylactic salpingectomy as her contraceptive method of choice?

This patient has many options. In describing them to her, it would be important to focus on the breadth of safe, reversible, long-acting contraceptives now available, including their respective risks, benefits, and long-term outcomes and costs. It also is important to consider the published data on these methods, weighing their relevance to her overall health and medical history. Although some data regarding the origin of ovarian cancer in the fallopian tubes may be especially compelling, it may not be wise to extrapolate it from a specific group of women to all patients, as we shall see.

Option 1: Cyclic OCs

This option should not be excluded, despite the need for daily dosing, because the patient has used it successfully for more than 10 years. OCs are highly effective and have the added benefits of reducing menstrual blood loss, alleviating cramps, and lowering the risks of endometrial and ovarian cancer.7

Option 2: LARC

Long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods include the LNG-IUS, the copper intrauterine device (IUD; ParaGard, Teva), and the etonogestrel implant (Nexplanon, Merck). Each of these contraceptives is similar to sterilization in terms of efficacy. None requires the interruption of sexual activity or weekly or monthly trips to the pharmacy.

The LNG-IUS and the etonogestrel implant have the added benefits of reducing menstrual blood loss and reducing or eliminating premenstrual symptoms and cramps in most women. In addition, they may reduce the risk of unopposed estrogen stimulation of the endometrium associated with perimenopausal anovulatory cycles.

Option 3: Transcervical tubal sterilization

This hysteroscopic method (Essure, Bayer) avoids the risks of general anesthesia, but successful bilateral placement may not be possible in a small percentage of women. It also requires a 3-month interval between placement and confirmation of tubal occlusion (via HSG). During this interval, alternative contraception must be used. Once occlusion is confirmed, this method is highly reliable.

Option 4: Laparoscopic sterilization

This approach was the method of choice prior to the introduction of Essure in 2002. There now is a resurgence of interest in laparoscopic sterilization due to recent publications describing the distal portion of the fallopian tube as the “true source” of high-grade serous ovarian cancers.

In pathologic analyses of fallopian tubes removed prophylactically from women with a BRCA 1 or 2 mutation, investigators found a significant rate of serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma.8 Researchers began to study the genetics of these cancers and concluded that, in women with a BRCA mutation, high-grade serous carcinomas may arise from the distal fallopian tube.

Until recently, all of the literature on these tubal carcinomas related only to women with a specific tumor suppressor gene p53 mutation in the BRCA system. Other investigators then reviewed pathology specimens from women without a BRCA mutation who had high-grade serous carcinomas that were peritoneal, tubal, or ovarian in origin. They found serous tubal intraepithelial carcinomas in 33% to 59% of these women.9

“Research suggests that bilateral salpingectomy during hysterectomy for benign indications or as a sterilization procedure may have benefits, such as preventing tubal disease and cancer, without significant risks,” wrote Gill and Mills.10 In conducting a survey of US physicians to determine how widespread prophylactic salpingectomy is during benign hysterectomy or sterilization, they found that 54% of respondents performed bilateral salpingectomy during hysterectomy, usually to lower the risk of cancer (75%) and avoid the need for reoperation (49.1%). Of the 45.5% of respondents who did not perform bilateral salpingectomy during hysterectomy, most (69.4%) believed it has no benefit.10

Although 58% of respondents believed bilateral salpingectomy to be the most effective option for sterilization in women older than 35 years, they reported that they reserve it for women in whom one sterilization procedure has failed or for women who have tubal disease.10

As for the 45.5% of respondents who did not perform prophylactic salpingectomy, they offered as reasons their concern about increased operative time and the risk of complications, as well as a belief that it has no benefit.10

The lifetime risk of ovarian cancer in the general population is 1 in 70 women. Although it is possible that high-grade serous ovarian cancers originate in the distal fallopian tube, as the research to date suggests, it also is possible that we might find in-situ lesions in tissues other than the distal tube, suggesting a more global genetic defect underlying ovarian cancers in the peritoneal and müllerian tissues. Randomized trials are under way in an effort to determine whether excision of the fallopian tubes will prevent the majority of high-grade serous cancers. It will be many years, however, before the results of these trials are available.

CASE 2: Resolved

This patient has used combination OCs for more than 10 years, so her lifetime risk of ovarian cancer has been reduced by approximately 50%. Because her family history indicates that a BRCA mutation is highly unlikely, her lifetime risk of ovarian cancer now has declined from 1:70 to roughly 1:140.

Prophylactic salpingectomy might offer a very small reduction in this patient’s absolute risk of ovarian cancer—from 0.75% to 0.50% lifetime risk—but the current data are not robust enough to suggest that it should be recommended for her. The operation would carry the risks associated with general anesthesia and peritoneal access. Although these risks are small, there is a documented risk of death from laparoscopic sterilization procedures in the United States, from complications related to bowel injury, anesthesia, and hemorrhage.

For these reasons, I would counsel this patient that her best options for contraception are combination OCs, transcervical tubal sterilization, or a long-acting reversible contraceptive such as the IUD or implant.

Tell us what you think, at [email protected]. Please include your name and city and state.

The development of new medical technology continues at a brisk pace—and ObGyns and our patients often are the beneficiaries. Notable technological breakthroughs of the past include hormonal contraception, in vitro fertilization, the application of minimally invasive surgical devices and techniques to gynecologic procedures, and many other innovations.

The leaders in our specialty are innovators themselves, ever vigilant for developments that can help improve health and quality of life for our patients. Regrettably, however, many technologies spread widely before they are fully validated by published studies—or continue to be used long after a superior or less invasive intervention has come along. And many claims about new technology are based on marketing information rather than reliable data.

Another common occurrence in regard to published data: Findings in one well-defined sector of the population are extrapolated to all patients. Even clinicians who are careful about adopting new technology can overlook the fact that it was tested, and proven, in a subset of patients that may not be comparable to all their patients.

In this article, I offer two case studies that illustrate some of the challenges we face when it comes to applying scientific findings to our practice and assessing medical technologies. In both settings, the health of the patient should be our primary focus.

When it comes to technology, patient selection is key

CASE 1: Anovulatory patient requests endometrial ablation

A 34-year-old woman (G2P2) who is moderately obese (body mass index of 32 kg/m2) visits your office to request endometrial ablation to manage her irregular and heavy menses. She reached menarche at age 10, and her periods have been somewhat irregular ever since. She required ovarian stimulation with clomiphene citrate to achieve each of her pregnancies, and both children were delivered by cesarean section. She currently uses condoms for contraception but does not have a steady partner, and she desires no additional pregnancies.

The patient reports that her menses occur every 2 to 6 weeks, with flow lasting from 2 to 8 days. She is housebound for 2 days each cycle because of heavy flow and cramping. She takes no medications and has no other medical conditions.

On exam, she is centrally obese with a tender uterus that is 10- to 12-weeks’ size; no adnexal masses are palpable. All other findings are normal. A recent test for diabetes was negative, but her serum cholesterol and triglyceride levels are borderline elevated.

What intervention would you recommend to address the heavy bleeding?

With the advent of second-generation endometrial ablation devices in the late 1990s, women with refractory menorrhagia had a safe, reliable, minimally invasive alternative to hysterectomy that made it possible to treat the endometrial cavity without the technical challenges of resectoscopic surgery. More than 10 million women report menorrhagia each year in the United States—so it is no small problem.1,2 Global endometrial ablation devices make management possible in an office setting, and recovery is significantly shorter than with hysterectomy. The three most prominent nonhysteroscopic ablation devices are (FIGURE):