User login

Getting back in the game

"When can I go back to play, doc?" is a question you’ll hear often when treating athletes with concussions. For many of them, the answer would be in 7-10 days, but for more moderate or severe cases, that could go up to a month or more. It all depends on the athlete and his or her concussion history. However, there are some general guidelines to follow to determine when an athlete is ready to get back on the field.

First of all, athletes should not be allowed to return to play in the current game or practice in which they were injured. From there, they should be medically managed and given adequate physical and cognitive rest until they are asymptomatic.

This means that all symptoms have resolved, the neurologic examination is normal and their cognitive function has returned to baseline, if this was established prior to injury. They also should not be on any medications for concussion, that is, they should not be popping acetaminophen for headaches.

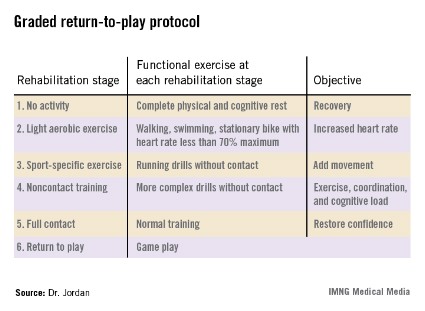

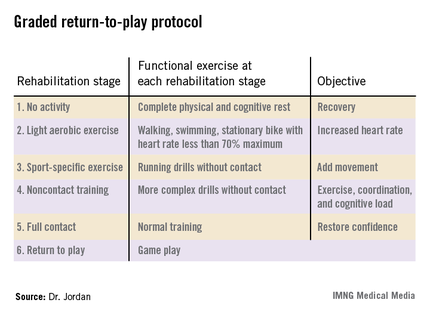

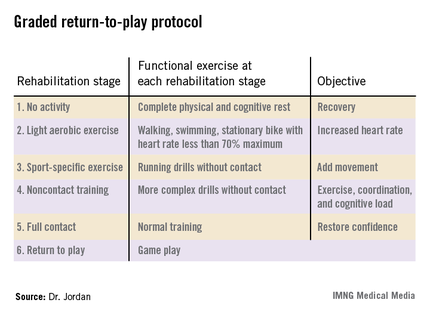

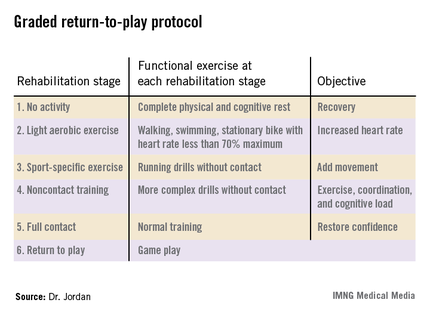

Another way to determine if the athlete is ready to get back in the game is by using the graded return-to-play protocol.

Typically, athletes move up the stages one level a day, although that is not necessary. You can certainly accelerate the process depending on the sport and the athlete. Those who are in noncontact sports like swimming can probably go through the levels quicker than someone who plays soccer.

I would suggest documenting how the athlete is doing throughout the process so everyone has a record of the athlete’s progress. I don’t think you can ever overdocument, and it’s a good habit to get into.

Along with the protocol, there’s also a computerized neuropsychological testing tool that’s fairly short and really focuses on what functions are affected. People tend to rely on this tool but you have to keep in mind that this is only one tool and should not be used alone.

Tools cannot replace a thorough cognitive evaluation. Just as there are no tests that can diagnose a concussion, there’s no tool that’ll say the athlete is ok to return to play. Ultimately, it is up to you to make that call, but the evaluation tools should certainly be used to help.

Dr. Barry Jordan is the director of the brain injury program and the memory evaluation treatment service at Burke Rehabilitation Hospital in White Plains, N.Y. He currently serves as the chief medical officer of the New York State Athletic Commission, a team physician for U.S.A. Boxing, and as a member of the NFL Players Association Mackey-White Traumatic Brain Injury Committee and the NFL Neuro-Cognitive Disability Committee.

"When can I go back to play, doc?" is a question you’ll hear often when treating athletes with concussions. For many of them, the answer would be in 7-10 days, but for more moderate or severe cases, that could go up to a month or more. It all depends on the athlete and his or her concussion history. However, there are some general guidelines to follow to determine when an athlete is ready to get back on the field.

First of all, athletes should not be allowed to return to play in the current game or practice in which they were injured. From there, they should be medically managed and given adequate physical and cognitive rest until they are asymptomatic.

This means that all symptoms have resolved, the neurologic examination is normal and their cognitive function has returned to baseline, if this was established prior to injury. They also should not be on any medications for concussion, that is, they should not be popping acetaminophen for headaches.

Another way to determine if the athlete is ready to get back in the game is by using the graded return-to-play protocol.

Typically, athletes move up the stages one level a day, although that is not necessary. You can certainly accelerate the process depending on the sport and the athlete. Those who are in noncontact sports like swimming can probably go through the levels quicker than someone who plays soccer.

I would suggest documenting how the athlete is doing throughout the process so everyone has a record of the athlete’s progress. I don’t think you can ever overdocument, and it’s a good habit to get into.

Along with the protocol, there’s also a computerized neuropsychological testing tool that’s fairly short and really focuses on what functions are affected. People tend to rely on this tool but you have to keep in mind that this is only one tool and should not be used alone.

Tools cannot replace a thorough cognitive evaluation. Just as there are no tests that can diagnose a concussion, there’s no tool that’ll say the athlete is ok to return to play. Ultimately, it is up to you to make that call, but the evaluation tools should certainly be used to help.

Dr. Barry Jordan is the director of the brain injury program and the memory evaluation treatment service at Burke Rehabilitation Hospital in White Plains, N.Y. He currently serves as the chief medical officer of the New York State Athletic Commission, a team physician for U.S.A. Boxing, and as a member of the NFL Players Association Mackey-White Traumatic Brain Injury Committee and the NFL Neuro-Cognitive Disability Committee.

"When can I go back to play, doc?" is a question you’ll hear often when treating athletes with concussions. For many of them, the answer would be in 7-10 days, but for more moderate or severe cases, that could go up to a month or more. It all depends on the athlete and his or her concussion history. However, there are some general guidelines to follow to determine when an athlete is ready to get back on the field.

First of all, athletes should not be allowed to return to play in the current game or practice in which they were injured. From there, they should be medically managed and given adequate physical and cognitive rest until they are asymptomatic.

This means that all symptoms have resolved, the neurologic examination is normal and their cognitive function has returned to baseline, if this was established prior to injury. They also should not be on any medications for concussion, that is, they should not be popping acetaminophen for headaches.

Another way to determine if the athlete is ready to get back in the game is by using the graded return-to-play protocol.

Typically, athletes move up the stages one level a day, although that is not necessary. You can certainly accelerate the process depending on the sport and the athlete. Those who are in noncontact sports like swimming can probably go through the levels quicker than someone who plays soccer.

I would suggest documenting how the athlete is doing throughout the process so everyone has a record of the athlete’s progress. I don’t think you can ever overdocument, and it’s a good habit to get into.

Along with the protocol, there’s also a computerized neuropsychological testing tool that’s fairly short and really focuses on what functions are affected. People tend to rely on this tool but you have to keep in mind that this is only one tool and should not be used alone.

Tools cannot replace a thorough cognitive evaluation. Just as there are no tests that can diagnose a concussion, there’s no tool that’ll say the athlete is ok to return to play. Ultimately, it is up to you to make that call, but the evaluation tools should certainly be used to help.

Dr. Barry Jordan is the director of the brain injury program and the memory evaluation treatment service at Burke Rehabilitation Hospital in White Plains, N.Y. He currently serves as the chief medical officer of the New York State Athletic Commission, a team physician for U.S.A. Boxing, and as a member of the NFL Players Association Mackey-White Traumatic Brain Injury Committee and the NFL Neuro-Cognitive Disability Committee.