User login

Empowering Culture Change and Safety on the Journey to Zero Harm With Huddle Cards

Empowering Culture Change and Safety on the Journey to Zero Harm With Huddle Cards

Safety event reporting plays a vital role in fostering a culture of safety within a health care organization. The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has shifted its focus from eradicating medical errors to minimizing or eliminating harm to patients.1 The National Center for Patient Safety’s objective is to prevent recurring errors by identifying and addressing systemic problems that may have been overlooked.2

Taking inspiration from industries known for high reliability, such as aviation and nuclear power, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) patient safety program aims to identify and eliminate system vulnerabilities, such as medical errors. Learning from near misses, which occur more frequently than actual adverse events, is a crucial part of this process.3 By addressing these issues, the VHA can establish safer systems and encourage continuous identification of potential problems with proactive resolution.

All staff should participate actively in event reporting, which involves documenting and communicating details, outcomes, and relevant data about an event to understand what occurred, evaluate success, identify areas for improvement, and inform future decisions. This helps identify system weaknesses, create opportunities to standardize procedures and enhance patient care.

At the high complexity Central Texas Veterans Health Care System (CTVHCS), the fiscal year (FY) 2023 All Employee Survey (AES) found that staff members require additional education and awareness regarding the reporting of patient safety concerns.4 The survey highlighted areas such as lack of education on reporting, doubts about the effectiveness of reporting, confusion about the process after a report is made, and insufficient feedback.

BACKGROUND

To improve the culture of safety and address deficiencies noted in the AES, the CTVHCS patient safety (PS) and high reliability organization (HRO) teams partnered to develop a quality improvement initiative to increase staff understanding of safety event reporting and strengthen the safety culture. The PS and HRO teams developed an innovative education model that integrates Joint Patient Safety Reporting System (JPSR) education into huddles.

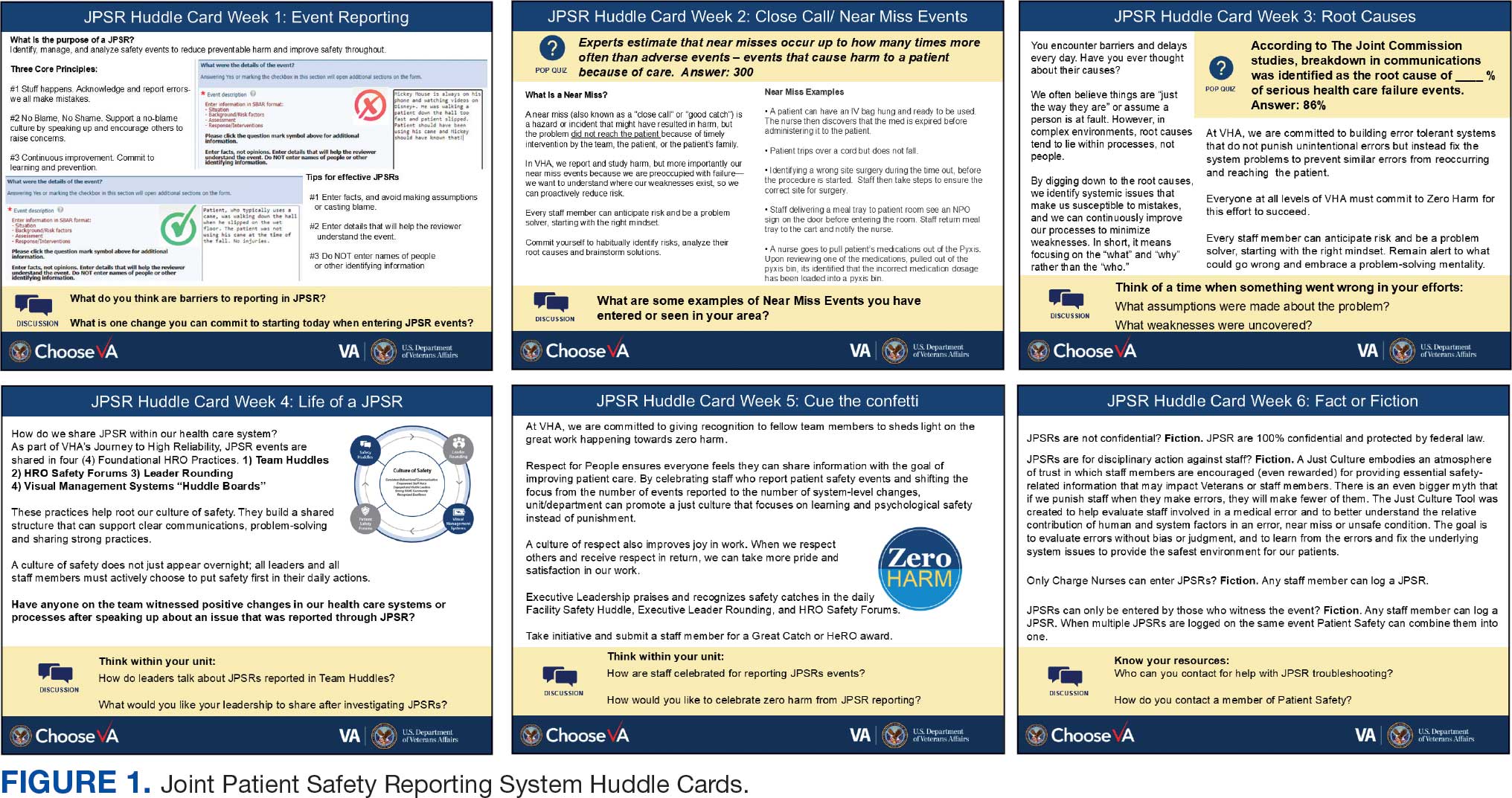

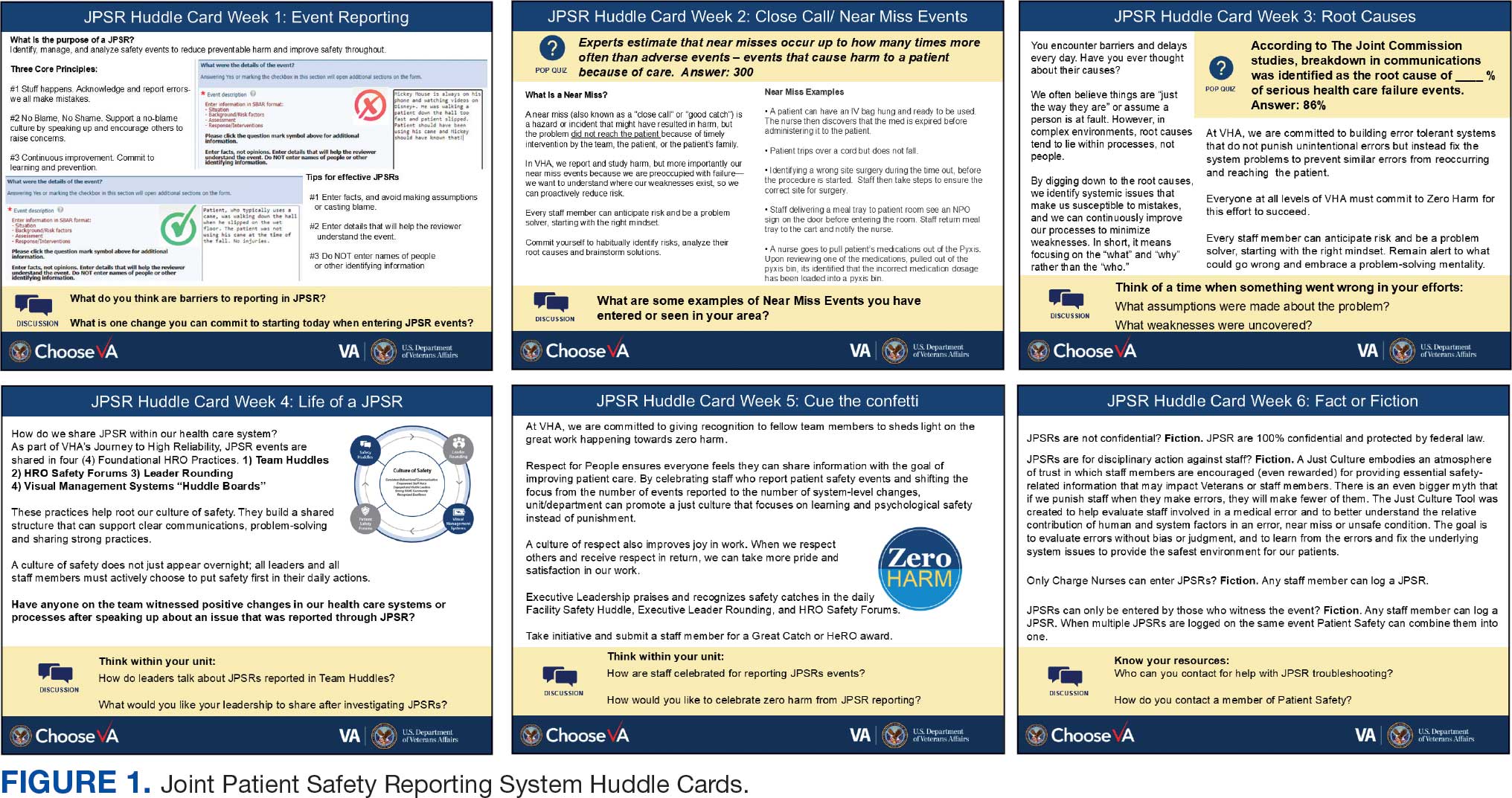

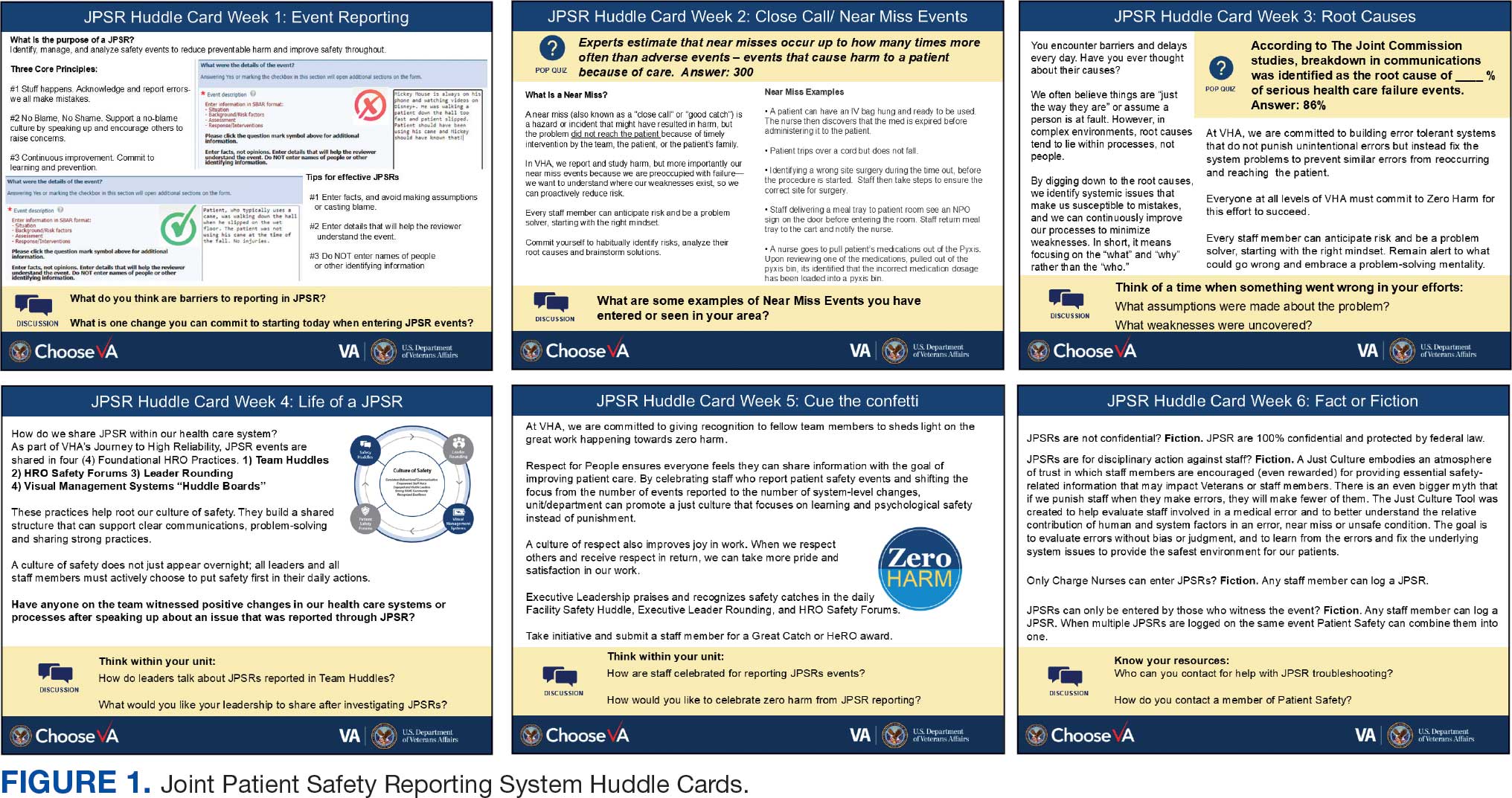

This initiative, called the JPSR Huddle Card Toolkit, sought to assess the impact of the toolkit on staff knowledge and behaviors related to patient safety event reporting. The toolkit consisted of educational materials encompassing 6 key areas: (1) reporting incidents; (2) close calls and near misses; (3) identification of root causes; (4) understanding the life cycle of a JPSR; (5) celebrating achievements; and (6) distinguishing between facts and fiction. Each JPSR huddle card included discussion points for the facilitator and was formatted on a 5 × 7-inch card (Figure 1). Topics were addressed during weekly safety huddles conducted in the pilot unit over a 6-week period. To evaluate its effectiveness, a pilot unit was selected and distributed an anonymous questionnaire paired with the JPSR huddle card toolkit to measure staff responses.

The pilot was conducted from November 2023 to January 2024. The participating pilot unit was a 10-bed critical care unit with 42 full-time employees. Nursing leadership, quality safety, and value personnel, and the Veterans Integrated Services Network (VISN) PS Team reviewed and approved the pilot.

Reporting of adverse events and near misses provides an opportunity to learn about latent systems errors.2 In 2018, the VHA began using the JPSR to standardize the capture and data management on medical errors and close calls across the Defense Health Administration (DHA) and VHA.1 The JPSR software is a joint application of the VHA and DHA. It improves the identification and documentation of patient safety-related events for VA medical centers, military hospitals and clinics, active-duty personnel, veterans and their families.

Event reporting is a key element in advancing high reliability and achieving zero preventable harm.1 Teams use these data to identify organizational patient safety trends and preempt common safety issues. All data are protected under 38 USC §5705 and 10 USC §1102.5 The JPSR single-source system standardizes the collection of core data points and increases collaboration between the DHA and VHA. This partnership increases insight into safety-related incidents, allowing for earlier detection and prevention of patient harm or injury incidents.

Numerous studies consistently commend huddles for their effectiveness in promoting teamwork and their positive impact on patient safety.6-8 Huddles facilitate connections between employees who may not typically interact, provide opportunities for discussions, and serve as a platform to encourage employees to voice their opinions. By fostering these interactions, huddles empower employees and create an environment for shared understanding, building trust, and promoting continuous learning.8

OBSERVATIONS

The JPSR huddle card initiative aimed to improve understanding of the JPSR process and promote knowledge and attitudes about patient safety and event reporting, while emphasizing shared responsibility. The goals focused on effective communication, respect for expertise, awareness of operational nuances, voicing concerns, and ensuring zero harm.

The facilitator initiated huddles by announcing their start to cultivate a constructive outcome.8 The JPSR huddle cards used a structured format designed to foster engagement and understanding of the topic. Each card begins with a factual statement or an open-ended question to gauge participants’ awareness or understanding. It then provides essential facts, principles, and relevant information to deepen knowledge. The card concludes with a discussion question, allowing facilitators to assess shared learning and encourage group reflection. This format promotes active participation and ensures that key concepts are both introduced and reinforced through dialogue.

The PS team standardized the format for all huddle cards, allowing 5 to 10 minutes for discussing training materials, receiving feedback, and concluding with a discussion question and call to action. Prior to each huddle, the facilitator would read a scripted remark that reviewed the objectives and ground rules for an effective huddle.

The PS and HRO teams promoted interactive discussions and welcomed ongoing feedback. Huddles provided a psychologically safe environment where individuals were encouraged to voice their thoughts and ideas.

Each weekly huddle card addressed a different patient safety topic. The Week 1 huddle card focuses on event reporting for safety improvement. The card outlines the purpose of JPSR as a tool to identify, manage, and analyze safety events to reduce preventable harm. The card emphasizes 3 core principles: (1) acknowledging mistakes, recognizing that errors happen; (2) no blame, no shame (encouraging a no-blame just culture to raise concerns); and (3) continuous improvement (committing to ongoing learning and prevention). It provides guidance on event details entry, advising staff to include facts in an SBAR (Situation, Background, Assessment, Response) format, avoid assumptions, and exclude personal identifiers. Tips include entering only relevant facts to help reviewers understand the incident. The card ends with discussion questions on reporting barriers and potential improvements in event reporting practices.

The Week 2 huddle card focuses on understanding and reporting near miss events, also known as close calls or good catches. A near miss is an incident where a potential hazard was identified and prevented before it reached the patient, avoiding harm due to timely intervention. The card emphasizes the importance of identifying these events to understand weaknesses and proactively reduce risks. Examples of near misses include discovering expired medication before use, catching a potential wrong-site surgery, and noticing incorrect medication dosages. Staff are encouraged to develop a mindset for anticipating and solving risks. The card ends with a discussion asking participants to share examples of near misses in their area.

The Week 3 huddle card covers root causes in preventing errors. The card highlights that errors in health care often stem from flawed processes rather than individual faults. By identifying root causes, systemic weaknesses can be addressed to reduce mistakes and build more error-tolerant and robust systems. All staff are advised to adopt a mindset of continuous improvement, error trapping behaviors and problem-solving. It concludes with discussion questions prompting reflection on assumptions and identifying weaknesses when something goes wrong.

The Week 4 huddle card covers the life of a JPSR, detailing that after entry JPSR events are viewed by the highest leadership levels at the morning report, and that lessons learned are distributed through frontline managers and chiefs in a monthly report to be shared with frontline staff. Additionally, JPSR trends are shared during monthly HRO safety forums. These practices promote a culture of safety through open communication and problem-solving. Staff and leaders are encouraged to prioritize safety daily. Discussion prompts ask team members if they had seen positive changes from JPSR reporting and what they would like leadership to communicate after investigations.

The Week 5 huddle card covers celebrating safety event reporting called Cue the Confetti. The VHA emphasizes recognizing staff who report safety events as part of their commitment to zero harm. By celebrating these contributions, the VHA fosters respect, joy, and satisfaction in the work. Staff are encouraged to nominate colleagues for recognition, reinforcing a supportive environment. Prompts invite teams to discuss how they celebrate JPSR reporting and how they’d like to enhance this culture of appreciation.

The Week 6 huddle card covers common misconceptions about JPSR. Key facts include that JPSRs are confidential, not for disciplinary action, and can be submitted by any staff member at any time. Only PS can view reporter identities for clarification purposes. The card concludes with prompts to ensure staff know how to access JPSR support and resources.

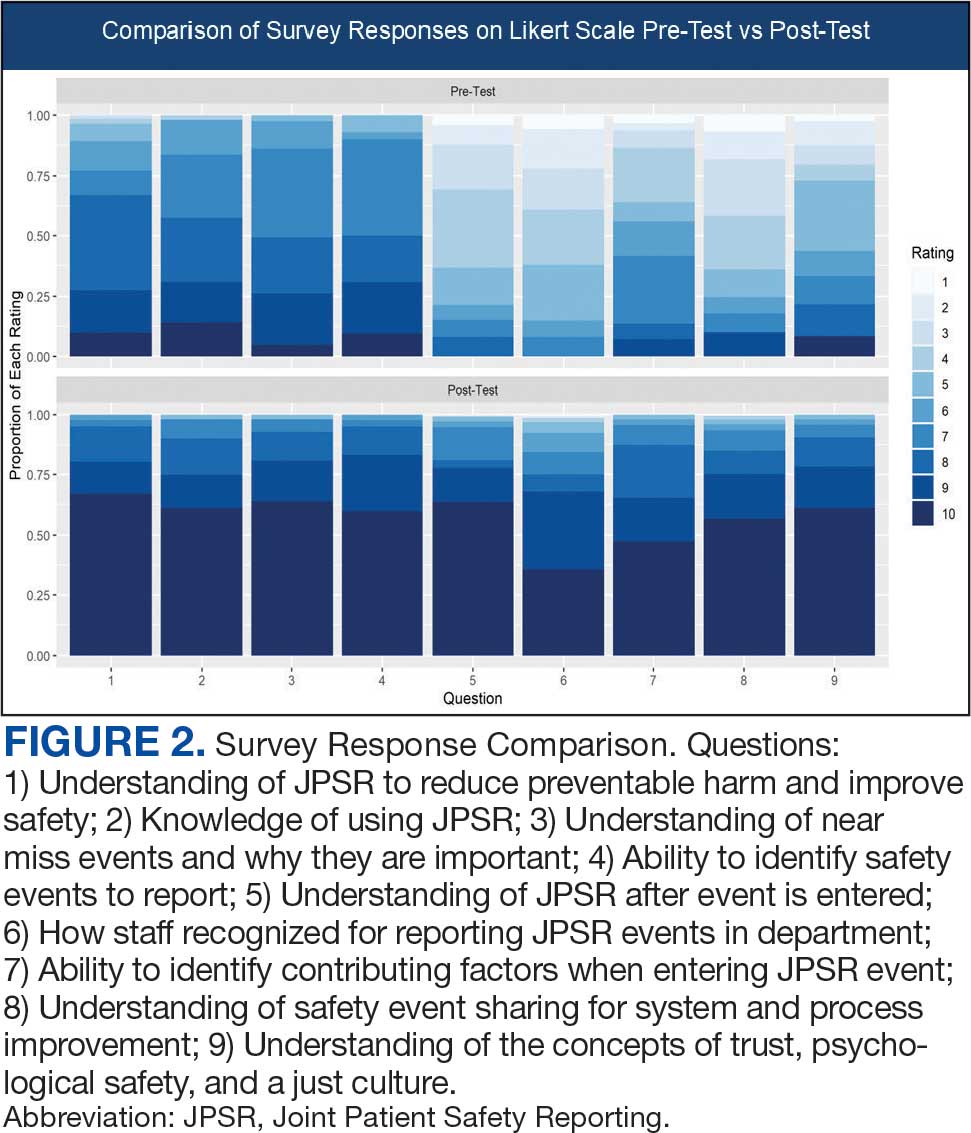

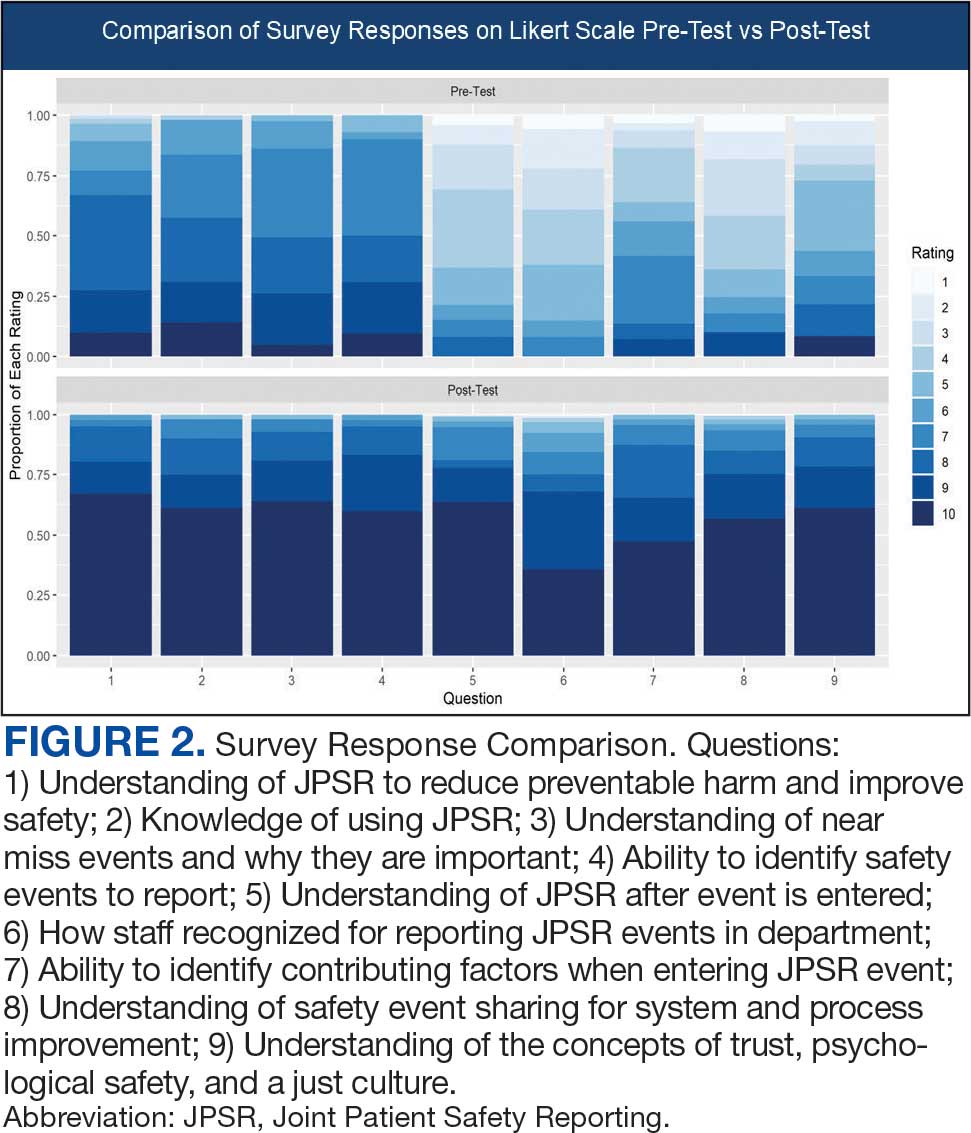

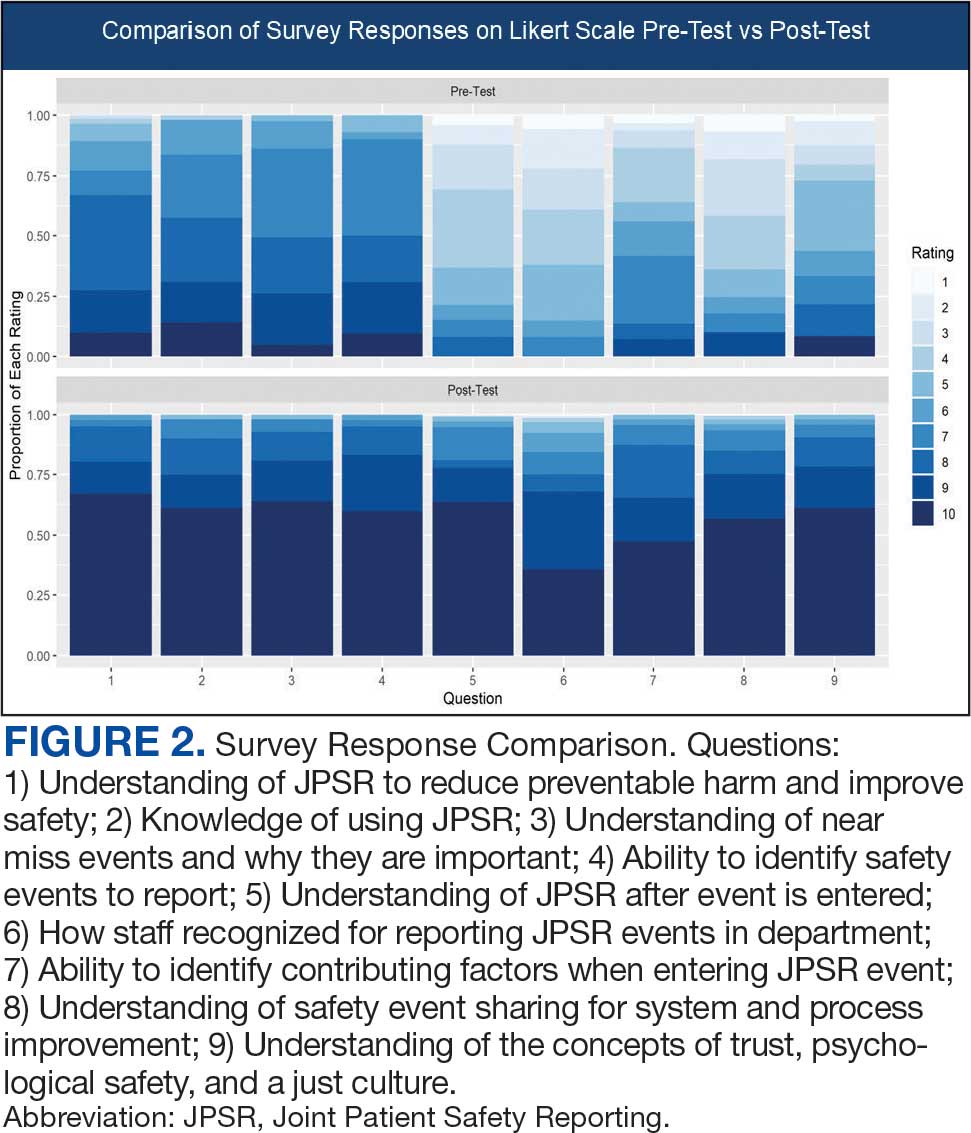

Measuring the impact on staff was essential to assess effectiveness and gather data for program improvement. To evaluate the impact of the huddle cards on the staff, the team provided a voluntary and anonymous 9 question survey (Figure 2). The survey was completed before the pilot began and again at the end of Week 6.

Questions 1 through 5 and 7 through 9 pertained to participants’ perceived knowledge and understanding of aspects of the JPSR. Perceived improvement among intensive care unit (ICU) participants ranged from 15% to 53%. There was a positive increase associated with every question with the top improvements: question 8, “How do you rate your understanding of how we share safety events for system and process improvement?” (53.4% increase); question 5, “How do you rate your understanding of what happens to a JPSR after it is entered?” (51.9% increase), and question 9, “How do you rate your understanding of the concepts of trust, psychological safety and a just culture?” (47.8% increase).

The survey analysis was not able to track individual changes. As a result, the findings reflect an overall change for the entire study group. Moreover, the questions assessed participants’ perceived knowledge rather than actual knowledge gained. It is important to note that there may be a significant gap between the actual knowledge gained and how participants perceive it. Additionally, improvement in knowledge and comprehension does not necessarily translate into behavior changes.

CONCLUSIONS

The use of JPSR huddle cards and direct engagement with staff during safety huddles yielded positive outcomes. On average, participants demonstrated higher scores in posttest questions compared to pretest questions. The posttest scores were consistently higher than the pretest scores, showing an average increase of around 2 standard deviations across all questions. This indicates an improvement in participants’ perceived knowledge and comprehension of the JPSR material.

During the pilot implementation of the huddle cards, there was a notable improvement in team member engagement. The structured format of the cards facilitated focused and meaningful discussions during safety huddles, encouraging open dialogue and fostering a culture of safety. Team members actively participated in identifying potential risks, sharing observations, and proposing actionable solutions, which reflected an enhanced sense of ownership regarding safety practices.

The support dialogue facilitated by the huddle cards highlighted the significance of mutual accountability and a collective commitment to achieving zero harm. This collaborative environment strengthened trust among team members and underscored the importance of shared vigilance in preventing adverse events. The pilot demonstrated the potential of huddle cards as an essential tool for enhancing team-based safety initiatives and promoting a culture of high reliability within the organization.

The total number of JPSR events in the ICU rose from 156 in FY 23 to 170 in FY 24. Adverse events increased from 19 to 31, while close calls saw a slight uptick from 137 to 139. Despite the overall rise in adverse events, a detailed analysis indicated that incidents of moderate harm decreased from 4 in FY 23 to 2 in FY 24. Furthermore, there was 1 reported case of death or severe harm in FY 23, which decreased to 0 in FY 24. This trend is consistent with the overarching objective of a high-reliability organization to achieve zero harm.

The next step is to expand this initiative across CTVHCS. This initiative aims to make this an annual education for all areas. The JPSR huddle card toolkit will be formatted by the media department for easy printing and retrieval. Leaders within units, clinics, and services will be empowered to facilitate the sessions in their safety huddles and reap the same outcomes as in the pilot. CTVHCS PS will monitor the effectiveness of this through ongoing CTVHCS patient safety rounding and future AES.

- Essen K, Villalobos C, Sculli GL, Steinbach L. Establishing a just culture: implications for the Veterans Health Administration journey to high reliability. Fed Pract. 2024;41:290-297. doi:10.12788/fp.0512

- Louis MY, Hussain LR, Dhanraj DN, et al. Improving patient safety event reporting among residents and teaching faculty. Ochsner J. 2016;16:73-80.

- Pimental CB, Snow AL, Carnes SL, et al. Huddles and their effectiveness at the frontlines of clinical care: a scoping review. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:2772-2783. doi:10.1007/s11606-021-06632-9

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Appendix C: Nature of Veterans Health Administration Facilities Management (Engineering) Tasks and Staffing. Facilities Staffing Requirements for the Veterans Health Administration-Resource Planning and Methodology for the Future. National Academies Press. 2020:105-116. Accessed August 11, 2025. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/25454/chapter/11

- Woodier N, Burnett C, Moppett I. The value of learning from near misses to improve patient safety: a scoping review. J Patient Saf. 2023;19:42-47. doi:10.1097/pts.0000000000001078

- Ismail A, Khalid SNM. Patient safety culture and its determinants among healthcare professionals at a cluster hospital in Malaysia: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e060546. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-060546

- Ngo J, Lau D, Ploquin J, Receveur T, Stassen K, Del Castilho C. Improving incident reporting among physicians at south health campus hospital. BMJ Open Qual. 2022;11:e001945. doi:10.1136/bmjoq-2022-001945

- Oweidat I, Al-Mugheed K, Alsenany SA, et al. Awareness of reporting practices and barriers to incident reporting among nurses. BMC Nurs. 2023;22:231. doi:10.1186/s12912-023-01376-9

Safety event reporting plays a vital role in fostering a culture of safety within a health care organization. The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has shifted its focus from eradicating medical errors to minimizing or eliminating harm to patients.1 The National Center for Patient Safety’s objective is to prevent recurring errors by identifying and addressing systemic problems that may have been overlooked.2

Taking inspiration from industries known for high reliability, such as aviation and nuclear power, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) patient safety program aims to identify and eliminate system vulnerabilities, such as medical errors. Learning from near misses, which occur more frequently than actual adverse events, is a crucial part of this process.3 By addressing these issues, the VHA can establish safer systems and encourage continuous identification of potential problems with proactive resolution.

All staff should participate actively in event reporting, which involves documenting and communicating details, outcomes, and relevant data about an event to understand what occurred, evaluate success, identify areas for improvement, and inform future decisions. This helps identify system weaknesses, create opportunities to standardize procedures and enhance patient care.

At the high complexity Central Texas Veterans Health Care System (CTVHCS), the fiscal year (FY) 2023 All Employee Survey (AES) found that staff members require additional education and awareness regarding the reporting of patient safety concerns.4 The survey highlighted areas such as lack of education on reporting, doubts about the effectiveness of reporting, confusion about the process after a report is made, and insufficient feedback.

BACKGROUND

To improve the culture of safety and address deficiencies noted in the AES, the CTVHCS patient safety (PS) and high reliability organization (HRO) teams partnered to develop a quality improvement initiative to increase staff understanding of safety event reporting and strengthen the safety culture. The PS and HRO teams developed an innovative education model that integrates Joint Patient Safety Reporting System (JPSR) education into huddles.

This initiative, called the JPSR Huddle Card Toolkit, sought to assess the impact of the toolkit on staff knowledge and behaviors related to patient safety event reporting. The toolkit consisted of educational materials encompassing 6 key areas: (1) reporting incidents; (2) close calls and near misses; (3) identification of root causes; (4) understanding the life cycle of a JPSR; (5) celebrating achievements; and (6) distinguishing between facts and fiction. Each JPSR huddle card included discussion points for the facilitator and was formatted on a 5 × 7-inch card (Figure 1). Topics were addressed during weekly safety huddles conducted in the pilot unit over a 6-week period. To evaluate its effectiveness, a pilot unit was selected and distributed an anonymous questionnaire paired with the JPSR huddle card toolkit to measure staff responses.

The pilot was conducted from November 2023 to January 2024. The participating pilot unit was a 10-bed critical care unit with 42 full-time employees. Nursing leadership, quality safety, and value personnel, and the Veterans Integrated Services Network (VISN) PS Team reviewed and approved the pilot.

Reporting of adverse events and near misses provides an opportunity to learn about latent systems errors.2 In 2018, the VHA began using the JPSR to standardize the capture and data management on medical errors and close calls across the Defense Health Administration (DHA) and VHA.1 The JPSR software is a joint application of the VHA and DHA. It improves the identification and documentation of patient safety-related events for VA medical centers, military hospitals and clinics, active-duty personnel, veterans and their families.

Event reporting is a key element in advancing high reliability and achieving zero preventable harm.1 Teams use these data to identify organizational patient safety trends and preempt common safety issues. All data are protected under 38 USC §5705 and 10 USC §1102.5 The JPSR single-source system standardizes the collection of core data points and increases collaboration between the DHA and VHA. This partnership increases insight into safety-related incidents, allowing for earlier detection and prevention of patient harm or injury incidents.

Numerous studies consistently commend huddles for their effectiveness in promoting teamwork and their positive impact on patient safety.6-8 Huddles facilitate connections between employees who may not typically interact, provide opportunities for discussions, and serve as a platform to encourage employees to voice their opinions. By fostering these interactions, huddles empower employees and create an environment for shared understanding, building trust, and promoting continuous learning.8

OBSERVATIONS

The JPSR huddle card initiative aimed to improve understanding of the JPSR process and promote knowledge and attitudes about patient safety and event reporting, while emphasizing shared responsibility. The goals focused on effective communication, respect for expertise, awareness of operational nuances, voicing concerns, and ensuring zero harm.

The facilitator initiated huddles by announcing their start to cultivate a constructive outcome.8 The JPSR huddle cards used a structured format designed to foster engagement and understanding of the topic. Each card begins with a factual statement or an open-ended question to gauge participants’ awareness or understanding. It then provides essential facts, principles, and relevant information to deepen knowledge. The card concludes with a discussion question, allowing facilitators to assess shared learning and encourage group reflection. This format promotes active participation and ensures that key concepts are both introduced and reinforced through dialogue.

The PS team standardized the format for all huddle cards, allowing 5 to 10 minutes for discussing training materials, receiving feedback, and concluding with a discussion question and call to action. Prior to each huddle, the facilitator would read a scripted remark that reviewed the objectives and ground rules for an effective huddle.

The PS and HRO teams promoted interactive discussions and welcomed ongoing feedback. Huddles provided a psychologically safe environment where individuals were encouraged to voice their thoughts and ideas.

Each weekly huddle card addressed a different patient safety topic. The Week 1 huddle card focuses on event reporting for safety improvement. The card outlines the purpose of JPSR as a tool to identify, manage, and analyze safety events to reduce preventable harm. The card emphasizes 3 core principles: (1) acknowledging mistakes, recognizing that errors happen; (2) no blame, no shame (encouraging a no-blame just culture to raise concerns); and (3) continuous improvement (committing to ongoing learning and prevention). It provides guidance on event details entry, advising staff to include facts in an SBAR (Situation, Background, Assessment, Response) format, avoid assumptions, and exclude personal identifiers. Tips include entering only relevant facts to help reviewers understand the incident. The card ends with discussion questions on reporting barriers and potential improvements in event reporting practices.

The Week 2 huddle card focuses on understanding and reporting near miss events, also known as close calls or good catches. A near miss is an incident where a potential hazard was identified and prevented before it reached the patient, avoiding harm due to timely intervention. The card emphasizes the importance of identifying these events to understand weaknesses and proactively reduce risks. Examples of near misses include discovering expired medication before use, catching a potential wrong-site surgery, and noticing incorrect medication dosages. Staff are encouraged to develop a mindset for anticipating and solving risks. The card ends with a discussion asking participants to share examples of near misses in their area.

The Week 3 huddle card covers root causes in preventing errors. The card highlights that errors in health care often stem from flawed processes rather than individual faults. By identifying root causes, systemic weaknesses can be addressed to reduce mistakes and build more error-tolerant and robust systems. All staff are advised to adopt a mindset of continuous improvement, error trapping behaviors and problem-solving. It concludes with discussion questions prompting reflection on assumptions and identifying weaknesses when something goes wrong.

The Week 4 huddle card covers the life of a JPSR, detailing that after entry JPSR events are viewed by the highest leadership levels at the morning report, and that lessons learned are distributed through frontline managers and chiefs in a monthly report to be shared with frontline staff. Additionally, JPSR trends are shared during monthly HRO safety forums. These practices promote a culture of safety through open communication and problem-solving. Staff and leaders are encouraged to prioritize safety daily. Discussion prompts ask team members if they had seen positive changes from JPSR reporting and what they would like leadership to communicate after investigations.

The Week 5 huddle card covers celebrating safety event reporting called Cue the Confetti. The VHA emphasizes recognizing staff who report safety events as part of their commitment to zero harm. By celebrating these contributions, the VHA fosters respect, joy, and satisfaction in the work. Staff are encouraged to nominate colleagues for recognition, reinforcing a supportive environment. Prompts invite teams to discuss how they celebrate JPSR reporting and how they’d like to enhance this culture of appreciation.

The Week 6 huddle card covers common misconceptions about JPSR. Key facts include that JPSRs are confidential, not for disciplinary action, and can be submitted by any staff member at any time. Only PS can view reporter identities for clarification purposes. The card concludes with prompts to ensure staff know how to access JPSR support and resources.

Measuring the impact on staff was essential to assess effectiveness and gather data for program improvement. To evaluate the impact of the huddle cards on the staff, the team provided a voluntary and anonymous 9 question survey (Figure 2). The survey was completed before the pilot began and again at the end of Week 6.

Questions 1 through 5 and 7 through 9 pertained to participants’ perceived knowledge and understanding of aspects of the JPSR. Perceived improvement among intensive care unit (ICU) participants ranged from 15% to 53%. There was a positive increase associated with every question with the top improvements: question 8, “How do you rate your understanding of how we share safety events for system and process improvement?” (53.4% increase); question 5, “How do you rate your understanding of what happens to a JPSR after it is entered?” (51.9% increase), and question 9, “How do you rate your understanding of the concepts of trust, psychological safety and a just culture?” (47.8% increase).

The survey analysis was not able to track individual changes. As a result, the findings reflect an overall change for the entire study group. Moreover, the questions assessed participants’ perceived knowledge rather than actual knowledge gained. It is important to note that there may be a significant gap between the actual knowledge gained and how participants perceive it. Additionally, improvement in knowledge and comprehension does not necessarily translate into behavior changes.

CONCLUSIONS

The use of JPSR huddle cards and direct engagement with staff during safety huddles yielded positive outcomes. On average, participants demonstrated higher scores in posttest questions compared to pretest questions. The posttest scores were consistently higher than the pretest scores, showing an average increase of around 2 standard deviations across all questions. This indicates an improvement in participants’ perceived knowledge and comprehension of the JPSR material.

During the pilot implementation of the huddle cards, there was a notable improvement in team member engagement. The structured format of the cards facilitated focused and meaningful discussions during safety huddles, encouraging open dialogue and fostering a culture of safety. Team members actively participated in identifying potential risks, sharing observations, and proposing actionable solutions, which reflected an enhanced sense of ownership regarding safety practices.

The support dialogue facilitated by the huddle cards highlighted the significance of mutual accountability and a collective commitment to achieving zero harm. This collaborative environment strengthened trust among team members and underscored the importance of shared vigilance in preventing adverse events. The pilot demonstrated the potential of huddle cards as an essential tool for enhancing team-based safety initiatives and promoting a culture of high reliability within the organization.

The total number of JPSR events in the ICU rose from 156 in FY 23 to 170 in FY 24. Adverse events increased from 19 to 31, while close calls saw a slight uptick from 137 to 139. Despite the overall rise in adverse events, a detailed analysis indicated that incidents of moderate harm decreased from 4 in FY 23 to 2 in FY 24. Furthermore, there was 1 reported case of death or severe harm in FY 23, which decreased to 0 in FY 24. This trend is consistent with the overarching objective of a high-reliability organization to achieve zero harm.

The next step is to expand this initiative across CTVHCS. This initiative aims to make this an annual education for all areas. The JPSR huddle card toolkit will be formatted by the media department for easy printing and retrieval. Leaders within units, clinics, and services will be empowered to facilitate the sessions in their safety huddles and reap the same outcomes as in the pilot. CTVHCS PS will monitor the effectiveness of this through ongoing CTVHCS patient safety rounding and future AES.

Safety event reporting plays a vital role in fostering a culture of safety within a health care organization. The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has shifted its focus from eradicating medical errors to minimizing or eliminating harm to patients.1 The National Center for Patient Safety’s objective is to prevent recurring errors by identifying and addressing systemic problems that may have been overlooked.2

Taking inspiration from industries known for high reliability, such as aviation and nuclear power, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) patient safety program aims to identify and eliminate system vulnerabilities, such as medical errors. Learning from near misses, which occur more frequently than actual adverse events, is a crucial part of this process.3 By addressing these issues, the VHA can establish safer systems and encourage continuous identification of potential problems with proactive resolution.

All staff should participate actively in event reporting, which involves documenting and communicating details, outcomes, and relevant data about an event to understand what occurred, evaluate success, identify areas for improvement, and inform future decisions. This helps identify system weaknesses, create opportunities to standardize procedures and enhance patient care.

At the high complexity Central Texas Veterans Health Care System (CTVHCS), the fiscal year (FY) 2023 All Employee Survey (AES) found that staff members require additional education and awareness regarding the reporting of patient safety concerns.4 The survey highlighted areas such as lack of education on reporting, doubts about the effectiveness of reporting, confusion about the process after a report is made, and insufficient feedback.

BACKGROUND

To improve the culture of safety and address deficiencies noted in the AES, the CTVHCS patient safety (PS) and high reliability organization (HRO) teams partnered to develop a quality improvement initiative to increase staff understanding of safety event reporting and strengthen the safety culture. The PS and HRO teams developed an innovative education model that integrates Joint Patient Safety Reporting System (JPSR) education into huddles.

This initiative, called the JPSR Huddle Card Toolkit, sought to assess the impact of the toolkit on staff knowledge and behaviors related to patient safety event reporting. The toolkit consisted of educational materials encompassing 6 key areas: (1) reporting incidents; (2) close calls and near misses; (3) identification of root causes; (4) understanding the life cycle of a JPSR; (5) celebrating achievements; and (6) distinguishing between facts and fiction. Each JPSR huddle card included discussion points for the facilitator and was formatted on a 5 × 7-inch card (Figure 1). Topics were addressed during weekly safety huddles conducted in the pilot unit over a 6-week period. To evaluate its effectiveness, a pilot unit was selected and distributed an anonymous questionnaire paired with the JPSR huddle card toolkit to measure staff responses.

The pilot was conducted from November 2023 to January 2024. The participating pilot unit was a 10-bed critical care unit with 42 full-time employees. Nursing leadership, quality safety, and value personnel, and the Veterans Integrated Services Network (VISN) PS Team reviewed and approved the pilot.

Reporting of adverse events and near misses provides an opportunity to learn about latent systems errors.2 In 2018, the VHA began using the JPSR to standardize the capture and data management on medical errors and close calls across the Defense Health Administration (DHA) and VHA.1 The JPSR software is a joint application of the VHA and DHA. It improves the identification and documentation of patient safety-related events for VA medical centers, military hospitals and clinics, active-duty personnel, veterans and their families.

Event reporting is a key element in advancing high reliability and achieving zero preventable harm.1 Teams use these data to identify organizational patient safety trends and preempt common safety issues. All data are protected under 38 USC §5705 and 10 USC §1102.5 The JPSR single-source system standardizes the collection of core data points and increases collaboration between the DHA and VHA. This partnership increases insight into safety-related incidents, allowing for earlier detection and prevention of patient harm or injury incidents.

Numerous studies consistently commend huddles for their effectiveness in promoting teamwork and their positive impact on patient safety.6-8 Huddles facilitate connections between employees who may not typically interact, provide opportunities for discussions, and serve as a platform to encourage employees to voice their opinions. By fostering these interactions, huddles empower employees and create an environment for shared understanding, building trust, and promoting continuous learning.8

OBSERVATIONS

The JPSR huddle card initiative aimed to improve understanding of the JPSR process and promote knowledge and attitudes about patient safety and event reporting, while emphasizing shared responsibility. The goals focused on effective communication, respect for expertise, awareness of operational nuances, voicing concerns, and ensuring zero harm.

The facilitator initiated huddles by announcing their start to cultivate a constructive outcome.8 The JPSR huddle cards used a structured format designed to foster engagement and understanding of the topic. Each card begins with a factual statement or an open-ended question to gauge participants’ awareness or understanding. It then provides essential facts, principles, and relevant information to deepen knowledge. The card concludes with a discussion question, allowing facilitators to assess shared learning and encourage group reflection. This format promotes active participation and ensures that key concepts are both introduced and reinforced through dialogue.

The PS team standardized the format for all huddle cards, allowing 5 to 10 minutes for discussing training materials, receiving feedback, and concluding with a discussion question and call to action. Prior to each huddle, the facilitator would read a scripted remark that reviewed the objectives and ground rules for an effective huddle.

The PS and HRO teams promoted interactive discussions and welcomed ongoing feedback. Huddles provided a psychologically safe environment where individuals were encouraged to voice their thoughts and ideas.

Each weekly huddle card addressed a different patient safety topic. The Week 1 huddle card focuses on event reporting for safety improvement. The card outlines the purpose of JPSR as a tool to identify, manage, and analyze safety events to reduce preventable harm. The card emphasizes 3 core principles: (1) acknowledging mistakes, recognizing that errors happen; (2) no blame, no shame (encouraging a no-blame just culture to raise concerns); and (3) continuous improvement (committing to ongoing learning and prevention). It provides guidance on event details entry, advising staff to include facts in an SBAR (Situation, Background, Assessment, Response) format, avoid assumptions, and exclude personal identifiers. Tips include entering only relevant facts to help reviewers understand the incident. The card ends with discussion questions on reporting barriers and potential improvements in event reporting practices.

The Week 2 huddle card focuses on understanding and reporting near miss events, also known as close calls or good catches. A near miss is an incident where a potential hazard was identified and prevented before it reached the patient, avoiding harm due to timely intervention. The card emphasizes the importance of identifying these events to understand weaknesses and proactively reduce risks. Examples of near misses include discovering expired medication before use, catching a potential wrong-site surgery, and noticing incorrect medication dosages. Staff are encouraged to develop a mindset for anticipating and solving risks. The card ends with a discussion asking participants to share examples of near misses in their area.

The Week 3 huddle card covers root causes in preventing errors. The card highlights that errors in health care often stem from flawed processes rather than individual faults. By identifying root causes, systemic weaknesses can be addressed to reduce mistakes and build more error-tolerant and robust systems. All staff are advised to adopt a mindset of continuous improvement, error trapping behaviors and problem-solving. It concludes with discussion questions prompting reflection on assumptions and identifying weaknesses when something goes wrong.

The Week 4 huddle card covers the life of a JPSR, detailing that after entry JPSR events are viewed by the highest leadership levels at the morning report, and that lessons learned are distributed through frontline managers and chiefs in a monthly report to be shared with frontline staff. Additionally, JPSR trends are shared during monthly HRO safety forums. These practices promote a culture of safety through open communication and problem-solving. Staff and leaders are encouraged to prioritize safety daily. Discussion prompts ask team members if they had seen positive changes from JPSR reporting and what they would like leadership to communicate after investigations.

The Week 5 huddle card covers celebrating safety event reporting called Cue the Confetti. The VHA emphasizes recognizing staff who report safety events as part of their commitment to zero harm. By celebrating these contributions, the VHA fosters respect, joy, and satisfaction in the work. Staff are encouraged to nominate colleagues for recognition, reinforcing a supportive environment. Prompts invite teams to discuss how they celebrate JPSR reporting and how they’d like to enhance this culture of appreciation.

The Week 6 huddle card covers common misconceptions about JPSR. Key facts include that JPSRs are confidential, not for disciplinary action, and can be submitted by any staff member at any time. Only PS can view reporter identities for clarification purposes. The card concludes with prompts to ensure staff know how to access JPSR support and resources.

Measuring the impact on staff was essential to assess effectiveness and gather data for program improvement. To evaluate the impact of the huddle cards on the staff, the team provided a voluntary and anonymous 9 question survey (Figure 2). The survey was completed before the pilot began and again at the end of Week 6.

Questions 1 through 5 and 7 through 9 pertained to participants’ perceived knowledge and understanding of aspects of the JPSR. Perceived improvement among intensive care unit (ICU) participants ranged from 15% to 53%. There was a positive increase associated with every question with the top improvements: question 8, “How do you rate your understanding of how we share safety events for system and process improvement?” (53.4% increase); question 5, “How do you rate your understanding of what happens to a JPSR after it is entered?” (51.9% increase), and question 9, “How do you rate your understanding of the concepts of trust, psychological safety and a just culture?” (47.8% increase).

The survey analysis was not able to track individual changes. As a result, the findings reflect an overall change for the entire study group. Moreover, the questions assessed participants’ perceived knowledge rather than actual knowledge gained. It is important to note that there may be a significant gap between the actual knowledge gained and how participants perceive it. Additionally, improvement in knowledge and comprehension does not necessarily translate into behavior changes.

CONCLUSIONS

The use of JPSR huddle cards and direct engagement with staff during safety huddles yielded positive outcomes. On average, participants demonstrated higher scores in posttest questions compared to pretest questions. The posttest scores were consistently higher than the pretest scores, showing an average increase of around 2 standard deviations across all questions. This indicates an improvement in participants’ perceived knowledge and comprehension of the JPSR material.

During the pilot implementation of the huddle cards, there was a notable improvement in team member engagement. The structured format of the cards facilitated focused and meaningful discussions during safety huddles, encouraging open dialogue and fostering a culture of safety. Team members actively participated in identifying potential risks, sharing observations, and proposing actionable solutions, which reflected an enhanced sense of ownership regarding safety practices.

The support dialogue facilitated by the huddle cards highlighted the significance of mutual accountability and a collective commitment to achieving zero harm. This collaborative environment strengthened trust among team members and underscored the importance of shared vigilance in preventing adverse events. The pilot demonstrated the potential of huddle cards as an essential tool for enhancing team-based safety initiatives and promoting a culture of high reliability within the organization.

The total number of JPSR events in the ICU rose from 156 in FY 23 to 170 in FY 24. Adverse events increased from 19 to 31, while close calls saw a slight uptick from 137 to 139. Despite the overall rise in adverse events, a detailed analysis indicated that incidents of moderate harm decreased from 4 in FY 23 to 2 in FY 24. Furthermore, there was 1 reported case of death or severe harm in FY 23, which decreased to 0 in FY 24. This trend is consistent with the overarching objective of a high-reliability organization to achieve zero harm.

The next step is to expand this initiative across CTVHCS. This initiative aims to make this an annual education for all areas. The JPSR huddle card toolkit will be formatted by the media department for easy printing and retrieval. Leaders within units, clinics, and services will be empowered to facilitate the sessions in their safety huddles and reap the same outcomes as in the pilot. CTVHCS PS will monitor the effectiveness of this through ongoing CTVHCS patient safety rounding and future AES.

- Essen K, Villalobos C, Sculli GL, Steinbach L. Establishing a just culture: implications for the Veterans Health Administration journey to high reliability. Fed Pract. 2024;41:290-297. doi:10.12788/fp.0512

- Louis MY, Hussain LR, Dhanraj DN, et al. Improving patient safety event reporting among residents and teaching faculty. Ochsner J. 2016;16:73-80.

- Pimental CB, Snow AL, Carnes SL, et al. Huddles and their effectiveness at the frontlines of clinical care: a scoping review. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:2772-2783. doi:10.1007/s11606-021-06632-9

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Appendix C: Nature of Veterans Health Administration Facilities Management (Engineering) Tasks and Staffing. Facilities Staffing Requirements for the Veterans Health Administration-Resource Planning and Methodology for the Future. National Academies Press. 2020:105-116. Accessed August 11, 2025. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/25454/chapter/11

- Woodier N, Burnett C, Moppett I. The value of learning from near misses to improve patient safety: a scoping review. J Patient Saf. 2023;19:42-47. doi:10.1097/pts.0000000000001078

- Ismail A, Khalid SNM. Patient safety culture and its determinants among healthcare professionals at a cluster hospital in Malaysia: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e060546. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-060546

- Ngo J, Lau D, Ploquin J, Receveur T, Stassen K, Del Castilho C. Improving incident reporting among physicians at south health campus hospital. BMJ Open Qual. 2022;11:e001945. doi:10.1136/bmjoq-2022-001945

- Oweidat I, Al-Mugheed K, Alsenany SA, et al. Awareness of reporting practices and barriers to incident reporting among nurses. BMC Nurs. 2023;22:231. doi:10.1186/s12912-023-01376-9

- Essen K, Villalobos C, Sculli GL, Steinbach L. Establishing a just culture: implications for the Veterans Health Administration journey to high reliability. Fed Pract. 2024;41:290-297. doi:10.12788/fp.0512

- Louis MY, Hussain LR, Dhanraj DN, et al. Improving patient safety event reporting among residents and teaching faculty. Ochsner J. 2016;16:73-80.

- Pimental CB, Snow AL, Carnes SL, et al. Huddles and their effectiveness at the frontlines of clinical care: a scoping review. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:2772-2783. doi:10.1007/s11606-021-06632-9

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Appendix C: Nature of Veterans Health Administration Facilities Management (Engineering) Tasks and Staffing. Facilities Staffing Requirements for the Veterans Health Administration-Resource Planning and Methodology for the Future. National Academies Press. 2020:105-116. Accessed August 11, 2025. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/25454/chapter/11

- Woodier N, Burnett C, Moppett I. The value of learning from near misses to improve patient safety: a scoping review. J Patient Saf. 2023;19:42-47. doi:10.1097/pts.0000000000001078

- Ismail A, Khalid SNM. Patient safety culture and its determinants among healthcare professionals at a cluster hospital in Malaysia: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e060546. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-060546

- Ngo J, Lau D, Ploquin J, Receveur T, Stassen K, Del Castilho C. Improving incident reporting among physicians at south health campus hospital. BMJ Open Qual. 2022;11:e001945. doi:10.1136/bmjoq-2022-001945

- Oweidat I, Al-Mugheed K, Alsenany SA, et al. Awareness of reporting practices and barriers to incident reporting among nurses. BMC Nurs. 2023;22:231. doi:10.1186/s12912-023-01376-9

Empowering Culture Change and Safety on the Journey to Zero Harm With Huddle Cards

Empowering Culture Change and Safety on the Journey to Zero Harm With Huddle Cards