User login

Worst comedy audience: far right or far left?

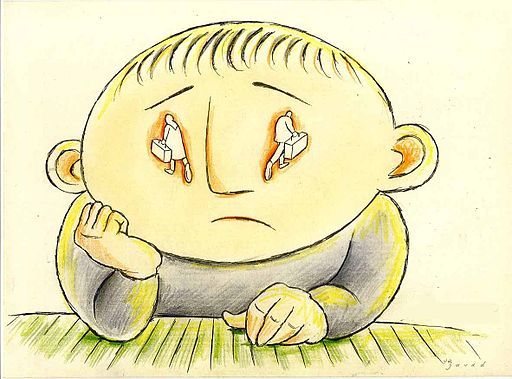

Comedy can be about pushing the limits of topics explored and questioning societal norms. For those comedians bold enough to push hard, the result can be societal pushback. As just one example, consider the arrest of George Carlin by Milwaukee police for allegedly violating public obscenity laws for uttering those seven naughty words not to be said on television (the charge was subsequently dismissed).

David Sedaris is a present-day boundary pusher. His sources of humor have ranged from his early life growing up in a family with five siblings to the challenges of getting older with aging parents, and from American attitudes about race to his own ambivalence about guns.

Pushback against his humor has come from both ends of the political spectrum. “I don’t know which is worse: a far-right audience or a far-left audience. Each of them is a hand around my throat slowly choking the life out of me,” Mr. Sedaris said in an interview with The Economist correspondent Anne McElvoy.

Mr. Sedaris’s take on the oddities of everyday life are side splitting to some, to the tune of millions of book sales and accolades as a giant of humor – and deeply offensive to others.

His career in making people laugh began in art school with monologues on the paintings of fellow students. What has followed is a life of keeping his eyes and ears open, and a notebook at the ready to record the goings-on of daily life.

Often, something bad can happen that can prove to be funny, at least in hindsight, Mr. Sedaris explains. He cites the example of his medical examination for a kidney stone that went sideways, with him ending up in the hospital’s waiting area clad only in his underwear.

“The thought came that someday, this will be funny to me. Today it’s not, but someday it will be,” Mr. Sedaris says.

Such humor seems global. Laughs at his stories may come at different parts, based on the language and cultural interpretations. But the basic premise of the story can hit home in far-flung places.

“It’s so hard to talk about race in the United States. ... The audience thinks: ‘Wait a minute, if I laugh at this, does it mean I’m racist?’ You can feel them getting snagged there, so oftentimes I just leave that element out of the story because I want the story to move,” Mr. Sedaris says.

Does that mean humor has a limit that should not be crossed? Not to Mr. Sedaris.

Click here to listen to the interview.

Comedy can be about pushing the limits of topics explored and questioning societal norms. For those comedians bold enough to push hard, the result can be societal pushback. As just one example, consider the arrest of George Carlin by Milwaukee police for allegedly violating public obscenity laws for uttering those seven naughty words not to be said on television (the charge was subsequently dismissed).

David Sedaris is a present-day boundary pusher. His sources of humor have ranged from his early life growing up in a family with five siblings to the challenges of getting older with aging parents, and from American attitudes about race to his own ambivalence about guns.

Pushback against his humor has come from both ends of the political spectrum. “I don’t know which is worse: a far-right audience or a far-left audience. Each of them is a hand around my throat slowly choking the life out of me,” Mr. Sedaris said in an interview with The Economist correspondent Anne McElvoy.

Mr. Sedaris’s take on the oddities of everyday life are side splitting to some, to the tune of millions of book sales and accolades as a giant of humor – and deeply offensive to others.

His career in making people laugh began in art school with monologues on the paintings of fellow students. What has followed is a life of keeping his eyes and ears open, and a notebook at the ready to record the goings-on of daily life.

Often, something bad can happen that can prove to be funny, at least in hindsight, Mr. Sedaris explains. He cites the example of his medical examination for a kidney stone that went sideways, with him ending up in the hospital’s waiting area clad only in his underwear.

“The thought came that someday, this will be funny to me. Today it’s not, but someday it will be,” Mr. Sedaris says.

Such humor seems global. Laughs at his stories may come at different parts, based on the language and cultural interpretations. But the basic premise of the story can hit home in far-flung places.

“It’s so hard to talk about race in the United States. ... The audience thinks: ‘Wait a minute, if I laugh at this, does it mean I’m racist?’ You can feel them getting snagged there, so oftentimes I just leave that element out of the story because I want the story to move,” Mr. Sedaris says.

Does that mean humor has a limit that should not be crossed? Not to Mr. Sedaris.

Click here to listen to the interview.

Comedy can be about pushing the limits of topics explored and questioning societal norms. For those comedians bold enough to push hard, the result can be societal pushback. As just one example, consider the arrest of George Carlin by Milwaukee police for allegedly violating public obscenity laws for uttering those seven naughty words not to be said on television (the charge was subsequently dismissed).

David Sedaris is a present-day boundary pusher. His sources of humor have ranged from his early life growing up in a family with five siblings to the challenges of getting older with aging parents, and from American attitudes about race to his own ambivalence about guns.

Pushback against his humor has come from both ends of the political spectrum. “I don’t know which is worse: a far-right audience or a far-left audience. Each of them is a hand around my throat slowly choking the life out of me,” Mr. Sedaris said in an interview with The Economist correspondent Anne McElvoy.

Mr. Sedaris’s take on the oddities of everyday life are side splitting to some, to the tune of millions of book sales and accolades as a giant of humor – and deeply offensive to others.

His career in making people laugh began in art school with monologues on the paintings of fellow students. What has followed is a life of keeping his eyes and ears open, and a notebook at the ready to record the goings-on of daily life.

Often, something bad can happen that can prove to be funny, at least in hindsight, Mr. Sedaris explains. He cites the example of his medical examination for a kidney stone that went sideways, with him ending up in the hospital’s waiting area clad only in his underwear.

“The thought came that someday, this will be funny to me. Today it’s not, but someday it will be,” Mr. Sedaris says.

Such humor seems global. Laughs at his stories may come at different parts, based on the language and cultural interpretations. But the basic premise of the story can hit home in far-flung places.

“It’s so hard to talk about race in the United States. ... The audience thinks: ‘Wait a minute, if I laugh at this, does it mean I’m racist?’ You can feel them getting snagged there, so oftentimes I just leave that element out of the story because I want the story to move,” Mr. Sedaris says.

Does that mean humor has a limit that should not be crossed? Not to Mr. Sedaris.

Click here to listen to the interview.

'Follow your passion' not always good career advice

“Follow your passion” has long been a self-help mantra when it comes to a career. The idea has been that doing what you love will provide the fuel for success. The thinking goes back decades to Richard Bolles’s self-published 1972 classic “What Color is Your Parachute”. The thinking has inspired countless career aspirants, including business titans.

“You’ve got to find what you love. … The only way to do great work is to love what you do. If you haven’t found it yet, keep looking, and don’t settle,” related the late Apple founder Steve Jobs in a commencement address delivered in 2005 at Stanford (Calif.) University. For Mr. Jobs and others over the past 4 decades, the bedrock foundation of a career is passion for the work and dreaming the big dream.

Cal Newport, the author of “So Good They Can’t Ignore You” (New York: Business Plus, 2012), takes the polar opposite view. The job-passion trail has little to do with why most people love the work they do, and can spawn anxiety and a pattern of moving from one job to another, according to Mr. Newport. Rather, passion for the job comes after the hours of hard work that are needed to become really good at something. How the work is done is more important than what the work is.

In “Designing Your Life” (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2016), Bill Burnett and Dave Evans go even further, arguing that a career based on passion is usually useless and sometimes dangerous, since many people don’t know what they are passionate about or are passionate about something that is a clunker from a career perspective. Following your passion can lead to chasing pipe dreams.

A better tact might be to insert “interest” instead of “passion” when pondering career choices, according to Crystal Holly, PhD, a clinical psychologist in Ottawa. she said in an interview for the article published on the website of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC).

Looking at interests more abstractly, rather than setting up a score sheet of definitive career goals, can be helpful, according to career coach Jen Polk, PhD, since that approach can lead to work areas not previously considered, which prove to be satisfying and fulfilling.

The path of job passion worked for Steve Jobs. But it might not be the way for many people.

Click here to read the CBC article.

“Follow your passion” has long been a self-help mantra when it comes to a career. The idea has been that doing what you love will provide the fuel for success. The thinking goes back decades to Richard Bolles’s self-published 1972 classic “What Color is Your Parachute”. The thinking has inspired countless career aspirants, including business titans.

“You’ve got to find what you love. … The only way to do great work is to love what you do. If you haven’t found it yet, keep looking, and don’t settle,” related the late Apple founder Steve Jobs in a commencement address delivered in 2005 at Stanford (Calif.) University. For Mr. Jobs and others over the past 4 decades, the bedrock foundation of a career is passion for the work and dreaming the big dream.

Cal Newport, the author of “So Good They Can’t Ignore You” (New York: Business Plus, 2012), takes the polar opposite view. The job-passion trail has little to do with why most people love the work they do, and can spawn anxiety and a pattern of moving from one job to another, according to Mr. Newport. Rather, passion for the job comes after the hours of hard work that are needed to become really good at something. How the work is done is more important than what the work is.

In “Designing Your Life” (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2016), Bill Burnett and Dave Evans go even further, arguing that a career based on passion is usually useless and sometimes dangerous, since many people don’t know what they are passionate about or are passionate about something that is a clunker from a career perspective. Following your passion can lead to chasing pipe dreams.

A better tact might be to insert “interest” instead of “passion” when pondering career choices, according to Crystal Holly, PhD, a clinical psychologist in Ottawa. she said in an interview for the article published on the website of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC).

Looking at interests more abstractly, rather than setting up a score sheet of definitive career goals, can be helpful, according to career coach Jen Polk, PhD, since that approach can lead to work areas not previously considered, which prove to be satisfying and fulfilling.

The path of job passion worked for Steve Jobs. But it might not be the way for many people.

Click here to read the CBC article.

“Follow your passion” has long been a self-help mantra when it comes to a career. The idea has been that doing what you love will provide the fuel for success. The thinking goes back decades to Richard Bolles’s self-published 1972 classic “What Color is Your Parachute”. The thinking has inspired countless career aspirants, including business titans.

“You’ve got to find what you love. … The only way to do great work is to love what you do. If you haven’t found it yet, keep looking, and don’t settle,” related the late Apple founder Steve Jobs in a commencement address delivered in 2005 at Stanford (Calif.) University. For Mr. Jobs and others over the past 4 decades, the bedrock foundation of a career is passion for the work and dreaming the big dream.

Cal Newport, the author of “So Good They Can’t Ignore You” (New York: Business Plus, 2012), takes the polar opposite view. The job-passion trail has little to do with why most people love the work they do, and can spawn anxiety and a pattern of moving from one job to another, according to Mr. Newport. Rather, passion for the job comes after the hours of hard work that are needed to become really good at something. How the work is done is more important than what the work is.

In “Designing Your Life” (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2016), Bill Burnett and Dave Evans go even further, arguing that a career based on passion is usually useless and sometimes dangerous, since many people don’t know what they are passionate about or are passionate about something that is a clunker from a career perspective. Following your passion can lead to chasing pipe dreams.

A better tact might be to insert “interest” instead of “passion” when pondering career choices, according to Crystal Holly, PhD, a clinical psychologist in Ottawa. she said in an interview for the article published on the website of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC).

Looking at interests more abstractly, rather than setting up a score sheet of definitive career goals, can be helpful, according to career coach Jen Polk, PhD, since that approach can lead to work areas not previously considered, which prove to be satisfying and fulfilling.

The path of job passion worked for Steve Jobs. But it might not be the way for many people.

Click here to read the CBC article.

Putting the brakes on ‘virality’

The Internet can be the antithesis of pondering before doing. “Take a breath,” “count to 10,” and “sleep on it” are all pearls of wisdom meant to keep people from doing or saying something that they will regret later. But the world of Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp is rife with rude responses and is a conduit for “virality” – the global dissemination of information.

The information can be silly and harmless. But it also can be false and damaging. A compelling example of the latter is the meddling in the 2016 U.S. presidential election by Russian operatives via Facebook.

The information also can prove lethal. An article in The Economist cites the example of at least two dozen people who were killed in India after stories linking them (falsely) to child abductions went viral on WhatsApp, a messaging service owned by Facebook.

Part of the problem with WhatsApp has been the capability of mass dissemination of a post. Since WhatsApp is not fueled by advertiser revenue, a drop in traffic does not affect the financial bottom line. A similar limit on Facebook and Twitter seems harder to envision.

And yet, the move could prove wise, according to the article. “The short-term pain caused by a decline in virality may be in the long-term interest of the social networks. Fake news and concerns about digital addiction, among other things, have already damaged the reputations of tech platforms. Moves to slow sharing could help see off draconian action by regulators and lawmakers,” according to the authors.

More than half the population of the planet uses the Internet. Fostering a climate of honest exchange of information and limiting the spread of malicious information could have a transformative effect.

Click here to read The Economist article.

The Internet can be the antithesis of pondering before doing. “Take a breath,” “count to 10,” and “sleep on it” are all pearls of wisdom meant to keep people from doing or saying something that they will regret later. But the world of Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp is rife with rude responses and is a conduit for “virality” – the global dissemination of information.

The information can be silly and harmless. But it also can be false and damaging. A compelling example of the latter is the meddling in the 2016 U.S. presidential election by Russian operatives via Facebook.

The information also can prove lethal. An article in The Economist cites the example of at least two dozen people who were killed in India after stories linking them (falsely) to child abductions went viral on WhatsApp, a messaging service owned by Facebook.

Part of the problem with WhatsApp has been the capability of mass dissemination of a post. Since WhatsApp is not fueled by advertiser revenue, a drop in traffic does not affect the financial bottom line. A similar limit on Facebook and Twitter seems harder to envision.

And yet, the move could prove wise, according to the article. “The short-term pain caused by a decline in virality may be in the long-term interest of the social networks. Fake news and concerns about digital addiction, among other things, have already damaged the reputations of tech platforms. Moves to slow sharing could help see off draconian action by regulators and lawmakers,” according to the authors.

More than half the population of the planet uses the Internet. Fostering a climate of honest exchange of information and limiting the spread of malicious information could have a transformative effect.

Click here to read The Economist article.

The Internet can be the antithesis of pondering before doing. “Take a breath,” “count to 10,” and “sleep on it” are all pearls of wisdom meant to keep people from doing or saying something that they will regret later. But the world of Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp is rife with rude responses and is a conduit for “virality” – the global dissemination of information.

The information can be silly and harmless. But it also can be false and damaging. A compelling example of the latter is the meddling in the 2016 U.S. presidential election by Russian operatives via Facebook.

The information also can prove lethal. An article in The Economist cites the example of at least two dozen people who were killed in India after stories linking them (falsely) to child abductions went viral on WhatsApp, a messaging service owned by Facebook.

Part of the problem with WhatsApp has been the capability of mass dissemination of a post. Since WhatsApp is not fueled by advertiser revenue, a drop in traffic does not affect the financial bottom line. A similar limit on Facebook and Twitter seems harder to envision.

And yet, the move could prove wise, according to the article. “The short-term pain caused by a decline in virality may be in the long-term interest of the social networks. Fake news and concerns about digital addiction, among other things, have already damaged the reputations of tech platforms. Moves to slow sharing could help see off draconian action by regulators and lawmakers,” according to the authors.

More than half the population of the planet uses the Internet. Fostering a climate of honest exchange of information and limiting the spread of malicious information could have a transformative effect.

Click here to read The Economist article.

Can celebrity stories about anxiety reduce stigma?

A public figure who chooses to share his or her private burdens can help others cope with a similar circumstance. Or, such actions might inspire feelings of annoyance and ridicule over the human foibles of someone who is rich and successful – and get airtime for something that many others struggle with alone.

Jessica Gold, MD, is with the department in psychiatry at Washington University in St. Louis. As a practicing psychiatrist who treats patients for anxiety-related conditions, she says she has been both grateful and annoyed at celebrity admissions of conditions like anxiety.

“People with mental health issues are still too often stigmatized in our culture, wrongly portrayed as weak or emotional, and this deters people from seeking care. So any increased awareness of what it’s really like to live with a mental health condition is obviously beneficial and extremely needed. I should be happy that anyone – celebrity or not – is speaking up about these topics. So why do I occasionally have a similar “here we go again” reaction when a celebrity talks about dealing with anxiety?” she wrote in an article for Self magazine.

One reason for the absence of empathy can be the perception that, since celebrities’ bread-and-butter is publicity, any pronouncement that makes the entertainment section can be good for their bank accounts.

For others,

Being annoyed with a celebrity proclamation is natural, according to Dr. Gold. But she advises people to think about why they are feeling that way.

“And in the back of your mind, remember that stigma attached to mental illness discourages people from seeking a diagnosis and treatment. So it’s a fantastic thing to see people with a voice and huge platform willingly open up about a mental health issue and help normalize it. This is especially the case when disclosures could uniquely target younger adults who consume media at high rates, and whose long delay to receiving treatment leads to worse outcomes or disability. Seeing a public figure disclose something so personal could save a life – or at least improve the quality of it.”

Click here to read the article.

A public figure who chooses to share his or her private burdens can help others cope with a similar circumstance. Or, such actions might inspire feelings of annoyance and ridicule over the human foibles of someone who is rich and successful – and get airtime for something that many others struggle with alone.

Jessica Gold, MD, is with the department in psychiatry at Washington University in St. Louis. As a practicing psychiatrist who treats patients for anxiety-related conditions, she says she has been both grateful and annoyed at celebrity admissions of conditions like anxiety.

“People with mental health issues are still too often stigmatized in our culture, wrongly portrayed as weak or emotional, and this deters people from seeking care. So any increased awareness of what it’s really like to live with a mental health condition is obviously beneficial and extremely needed. I should be happy that anyone – celebrity or not – is speaking up about these topics. So why do I occasionally have a similar “here we go again” reaction when a celebrity talks about dealing with anxiety?” she wrote in an article for Self magazine.

One reason for the absence of empathy can be the perception that, since celebrities’ bread-and-butter is publicity, any pronouncement that makes the entertainment section can be good for their bank accounts.

For others,

Being annoyed with a celebrity proclamation is natural, according to Dr. Gold. But she advises people to think about why they are feeling that way.

“And in the back of your mind, remember that stigma attached to mental illness discourages people from seeking a diagnosis and treatment. So it’s a fantastic thing to see people with a voice and huge platform willingly open up about a mental health issue and help normalize it. This is especially the case when disclosures could uniquely target younger adults who consume media at high rates, and whose long delay to receiving treatment leads to worse outcomes or disability. Seeing a public figure disclose something so personal could save a life – or at least improve the quality of it.”

Click here to read the article.

A public figure who chooses to share his or her private burdens can help others cope with a similar circumstance. Or, such actions might inspire feelings of annoyance and ridicule over the human foibles of someone who is rich and successful – and get airtime for something that many others struggle with alone.

Jessica Gold, MD, is with the department in psychiatry at Washington University in St. Louis. As a practicing psychiatrist who treats patients for anxiety-related conditions, she says she has been both grateful and annoyed at celebrity admissions of conditions like anxiety.

“People with mental health issues are still too often stigmatized in our culture, wrongly portrayed as weak or emotional, and this deters people from seeking care. So any increased awareness of what it’s really like to live with a mental health condition is obviously beneficial and extremely needed. I should be happy that anyone – celebrity or not – is speaking up about these topics. So why do I occasionally have a similar “here we go again” reaction when a celebrity talks about dealing with anxiety?” she wrote in an article for Self magazine.

One reason for the absence of empathy can be the perception that, since celebrities’ bread-and-butter is publicity, any pronouncement that makes the entertainment section can be good for their bank accounts.

For others,

Being annoyed with a celebrity proclamation is natural, according to Dr. Gold. But she advises people to think about why they are feeling that way.

“And in the back of your mind, remember that stigma attached to mental illness discourages people from seeking a diagnosis and treatment. So it’s a fantastic thing to see people with a voice and huge platform willingly open up about a mental health issue and help normalize it. This is especially the case when disclosures could uniquely target younger adults who consume media at high rates, and whose long delay to receiving treatment leads to worse outcomes or disability. Seeing a public figure disclose something so personal could save a life – or at least improve the quality of it.”

Click here to read the article.

Not all drugs are created equal in the U.S. drug crisis

Conversation surrounding the drug crisis in the United States tends to focus on OxyContin, methamphetamine, fentanyl, and heroin. They are trouble for sure and are ruining the lives of many. But, as argued by Nicole Fisher in an article in Forbes, the discussion needs to be broadened to consider the purity and potency of the drugs being consumed.

“At face value, one might think that OxyContin is OxyContin or heroin is heroin. But that couldn’t be further from the truth,” writes Ms. Fisher.

Illicit drugs can contain other compounds, like methamphetamine and other addictive substances, or even rat poison. The result can be a lethal brew. Only a decade ago, when methamphetamine was cooked up in basement labs, the purity was nowhere near that of the nearly pure product made now by drug cartels.

The purity of meth has skyrocketed from 39% in 2008 to more than 93% now.

Just fighting opioid prescription abuse may be a simplistic response to a more complex problem. The variations in the composition and potency of illicit drugs is important but is being overlooked.

“As we craft ways to fight the opioid crisis in the U.S., it is necessary to ensure that we understand exactly what chemical compositions we are battling against,” Ms. Fisher writes.

Recent data on the purity of drugs seized by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency hammer home this point. The data reveal a varied picture across the country. Whatever the reason – the origin of the product, the distribution network, the dealers involved in the preparation and sale, and more – the result can be a more lethal drug, especially in a user from an area where less pure drugs are the norm.

Click here to read the Forbes article.

Conversation surrounding the drug crisis in the United States tends to focus on OxyContin, methamphetamine, fentanyl, and heroin. They are trouble for sure and are ruining the lives of many. But, as argued by Nicole Fisher in an article in Forbes, the discussion needs to be broadened to consider the purity and potency of the drugs being consumed.

“At face value, one might think that OxyContin is OxyContin or heroin is heroin. But that couldn’t be further from the truth,” writes Ms. Fisher.

Illicit drugs can contain other compounds, like methamphetamine and other addictive substances, or even rat poison. The result can be a lethal brew. Only a decade ago, when methamphetamine was cooked up in basement labs, the purity was nowhere near that of the nearly pure product made now by drug cartels.

The purity of meth has skyrocketed from 39% in 2008 to more than 93% now.

Just fighting opioid prescription abuse may be a simplistic response to a more complex problem. The variations in the composition and potency of illicit drugs is important but is being overlooked.

“As we craft ways to fight the opioid crisis in the U.S., it is necessary to ensure that we understand exactly what chemical compositions we are battling against,” Ms. Fisher writes.

Recent data on the purity of drugs seized by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency hammer home this point. The data reveal a varied picture across the country. Whatever the reason – the origin of the product, the distribution network, the dealers involved in the preparation and sale, and more – the result can be a more lethal drug, especially in a user from an area where less pure drugs are the norm.

Click here to read the Forbes article.

Conversation surrounding the drug crisis in the United States tends to focus on OxyContin, methamphetamine, fentanyl, and heroin. They are trouble for sure and are ruining the lives of many. But, as argued by Nicole Fisher in an article in Forbes, the discussion needs to be broadened to consider the purity and potency of the drugs being consumed.

“At face value, one might think that OxyContin is OxyContin or heroin is heroin. But that couldn’t be further from the truth,” writes Ms. Fisher.

Illicit drugs can contain other compounds, like methamphetamine and other addictive substances, or even rat poison. The result can be a lethal brew. Only a decade ago, when methamphetamine was cooked up in basement labs, the purity was nowhere near that of the nearly pure product made now by drug cartels.

The purity of meth has skyrocketed from 39% in 2008 to more than 93% now.

Just fighting opioid prescription abuse may be a simplistic response to a more complex problem. The variations in the composition and potency of illicit drugs is important but is being overlooked.

“As we craft ways to fight the opioid crisis in the U.S., it is necessary to ensure that we understand exactly what chemical compositions we are battling against,” Ms. Fisher writes.

Recent data on the purity of drugs seized by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency hammer home this point. The data reveal a varied picture across the country. Whatever the reason – the origin of the product, the distribution network, the dealers involved in the preparation and sale, and more – the result can be a more lethal drug, especially in a user from an area where less pure drugs are the norm.

Click here to read the Forbes article.

Prescribing psychotropics to pediatric patients

Writing about prescribing psychotropics to children for depression, anxiety, or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) sometimes brings conspiratorial accusations from readers, pediatrician Perri Klass, MD, writes in her column, “The Checkup” in the New York Times.

Some readers react to these discussions by suggesting that Dr. Klass is beholden to pharmaceutical companies. Others suggest that she wants to medicate young patients for behaviors that are a normal part of childhood. Of course, prescribing those medications to young patients should never be taken lightly, she says.

“It is a big deal, and there are side effects to worry about and doctors should listen to families’ concerns,” writes Dr. Klass, professor of journalism and pediatrics at New York University. “But when a child is suffering and struggling, families need help and medications are often part of the discussion.”

Dr. Klass goes on to interview Doris M. Greenberg, MD, and psychiatrist Timothy Wilens, MD, about the way they approach the treatment of children with psychiatric illness.

Click here to read Dr. Klass’s article in the Times.

Writing about prescribing psychotropics to children for depression, anxiety, or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) sometimes brings conspiratorial accusations from readers, pediatrician Perri Klass, MD, writes in her column, “The Checkup” in the New York Times.

Some readers react to these discussions by suggesting that Dr. Klass is beholden to pharmaceutical companies. Others suggest that she wants to medicate young patients for behaviors that are a normal part of childhood. Of course, prescribing those medications to young patients should never be taken lightly, she says.

“It is a big deal, and there are side effects to worry about and doctors should listen to families’ concerns,” writes Dr. Klass, professor of journalism and pediatrics at New York University. “But when a child is suffering and struggling, families need help and medications are often part of the discussion.”

Dr. Klass goes on to interview Doris M. Greenberg, MD, and psychiatrist Timothy Wilens, MD, about the way they approach the treatment of children with psychiatric illness.

Click here to read Dr. Klass’s article in the Times.

Writing about prescribing psychotropics to children for depression, anxiety, or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) sometimes brings conspiratorial accusations from readers, pediatrician Perri Klass, MD, writes in her column, “The Checkup” in the New York Times.

Some readers react to these discussions by suggesting that Dr. Klass is beholden to pharmaceutical companies. Others suggest that she wants to medicate young patients for behaviors that are a normal part of childhood. Of course, prescribing those medications to young patients should never be taken lightly, she says.

“It is a big deal, and there are side effects to worry about and doctors should listen to families’ concerns,” writes Dr. Klass, professor of journalism and pediatrics at New York University. “But when a child is suffering and struggling, families need help and medications are often part of the discussion.”

Dr. Klass goes on to interview Doris M. Greenberg, MD, and psychiatrist Timothy Wilens, MD, about the way they approach the treatment of children with psychiatric illness.

Click here to read Dr. Klass’s article in the Times.

Children, adolescents of divorcing parents want more say

Parents who are in the midst of a divorce might want to protect their children from details tied to the breakup, such as parenting arrangements. But they might be doing more harm than good.

A survey of 61 children and adolescents who recently had gone through their parents’ divorce suggested that many want a say in how the divorce will affect them, according to a report broadcast by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC).

The parents’ actions are benevolent in their intention, but they “may be associated with the experience of harm on the part of children and young people where their agency and capacity to participate in decision making that affects them isn’t acknowledged and accommodated,” said study lead Rachel Carson, PhD, of the Australian Institute of Family Studies, in an interview.

To conduct the survey, the research team conducted interviews with the children and adolescents, aged 10-17 years. They also interviewed 47 parents of those children.

Most of the children and adolescents interviewed said they felt isolated from their parents’ divorce, with little or no influence on the process. The ABC report included several quotations from the interviewees, including “Phoebe,” who was 15 years old at the time of the survey.

“When a kid goes through a divorce, a lot of the time the adults become very immature, so the children grow up a lot quicker,” Phoebe said.

The survey concluded that a “child-inclusive approach be adopted incorporating the features of effective professional practice. ...A commitment to this approach would importantly be a step towards meeting the loud and clear calls from participating children and young people to ‘give children a bigger voice, more of the time.’ ”

Click here to listen to the ABC story.

Parents who are in the midst of a divorce might want to protect their children from details tied to the breakup, such as parenting arrangements. But they might be doing more harm than good.

A survey of 61 children and adolescents who recently had gone through their parents’ divorce suggested that many want a say in how the divorce will affect them, according to a report broadcast by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC).

The parents’ actions are benevolent in their intention, but they “may be associated with the experience of harm on the part of children and young people where their agency and capacity to participate in decision making that affects them isn’t acknowledged and accommodated,” said study lead Rachel Carson, PhD, of the Australian Institute of Family Studies, in an interview.

To conduct the survey, the research team conducted interviews with the children and adolescents, aged 10-17 years. They also interviewed 47 parents of those children.

Most of the children and adolescents interviewed said they felt isolated from their parents’ divorce, with little or no influence on the process. The ABC report included several quotations from the interviewees, including “Phoebe,” who was 15 years old at the time of the survey.

“When a kid goes through a divorce, a lot of the time the adults become very immature, so the children grow up a lot quicker,” Phoebe said.

The survey concluded that a “child-inclusive approach be adopted incorporating the features of effective professional practice. ...A commitment to this approach would importantly be a step towards meeting the loud and clear calls from participating children and young people to ‘give children a bigger voice, more of the time.’ ”

Click here to listen to the ABC story.

Parents who are in the midst of a divorce might want to protect their children from details tied to the breakup, such as parenting arrangements. But they might be doing more harm than good.

A survey of 61 children and adolescents who recently had gone through their parents’ divorce suggested that many want a say in how the divorce will affect them, according to a report broadcast by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC).

The parents’ actions are benevolent in their intention, but they “may be associated with the experience of harm on the part of children and young people where their agency and capacity to participate in decision making that affects them isn’t acknowledged and accommodated,” said study lead Rachel Carson, PhD, of the Australian Institute of Family Studies, in an interview.

To conduct the survey, the research team conducted interviews with the children and adolescents, aged 10-17 years. They also interviewed 47 parents of those children.

Most of the children and adolescents interviewed said they felt isolated from their parents’ divorce, with little or no influence on the process. The ABC report included several quotations from the interviewees, including “Phoebe,” who was 15 years old at the time of the survey.

“When a kid goes through a divorce, a lot of the time the adults become very immature, so the children grow up a lot quicker,” Phoebe said.

The survey concluded that a “child-inclusive approach be adopted incorporating the features of effective professional practice. ...A commitment to this approach would importantly be a step towards meeting the loud and clear calls from participating children and young people to ‘give children a bigger voice, more of the time.’ ”

Click here to listen to the ABC story.

Company is giving drug users a second chance

An electric wire plant in Richmond, Ind., is bucking the practice of rejecting job applicants who fail drug tests.

Instead, the century-old Belden, a St. Louis-based company that also makes cable products, Internet routers, and other high-tech equipment, is offering Richmond plant applicants a job – if they complete a free 1- to 4-month drug treatment program.

The pilot program – called Pathways to Employment – aims to address two problems: the opioid crisis gripping the country and the worker shortage faced by many U.S. companies. Belden works with several local partners. The initiative was conceived with Mitchell S. Rosenthal, MD, a psychiatrist who serves as president of the Rosenthal Center for Addiction Studies and was founder of Phoenix House, the nonprofit drug treatment group. The program is thought to be the first of its kind.

in hiring the folks we needed,” said Doug Brenneke, Belden’s vice president of research and development, in an interview with National Public Radio.

Belden also is offering the program to the broader community – not just people who are part of the plant’s workforce. “We think part of the solution is offering basically a path out,” Mr. Brenneke told NPR. “It’s not a silver bullet, but it is part of an overall solution, we believe, to the epidemic.”

Click here to hear the NPR story.

An electric wire plant in Richmond, Ind., is bucking the practice of rejecting job applicants who fail drug tests.

Instead, the century-old Belden, a St. Louis-based company that also makes cable products, Internet routers, and other high-tech equipment, is offering Richmond plant applicants a job – if they complete a free 1- to 4-month drug treatment program.

The pilot program – called Pathways to Employment – aims to address two problems: the opioid crisis gripping the country and the worker shortage faced by many U.S. companies. Belden works with several local partners. The initiative was conceived with Mitchell S. Rosenthal, MD, a psychiatrist who serves as president of the Rosenthal Center for Addiction Studies and was founder of Phoenix House, the nonprofit drug treatment group. The program is thought to be the first of its kind.

in hiring the folks we needed,” said Doug Brenneke, Belden’s vice president of research and development, in an interview with National Public Radio.

Belden also is offering the program to the broader community – not just people who are part of the plant’s workforce. “We think part of the solution is offering basically a path out,” Mr. Brenneke told NPR. “It’s not a silver bullet, but it is part of an overall solution, we believe, to the epidemic.”

Click here to hear the NPR story.

An electric wire plant in Richmond, Ind., is bucking the practice of rejecting job applicants who fail drug tests.

Instead, the century-old Belden, a St. Louis-based company that also makes cable products, Internet routers, and other high-tech equipment, is offering Richmond plant applicants a job – if they complete a free 1- to 4-month drug treatment program.

The pilot program – called Pathways to Employment – aims to address two problems: the opioid crisis gripping the country and the worker shortage faced by many U.S. companies. Belden works with several local partners. The initiative was conceived with Mitchell S. Rosenthal, MD, a psychiatrist who serves as president of the Rosenthal Center for Addiction Studies and was founder of Phoenix House, the nonprofit drug treatment group. The program is thought to be the first of its kind.

in hiring the folks we needed,” said Doug Brenneke, Belden’s vice president of research and development, in an interview with National Public Radio.

Belden also is offering the program to the broader community – not just people who are part of the plant’s workforce. “We think part of the solution is offering basically a path out,” Mr. Brenneke told NPR. “It’s not a silver bullet, but it is part of an overall solution, we believe, to the epidemic.”

Click here to hear the NPR story.

Mothers’ parenting decisions and social norms

Leaving children to fend for themselves used to be viewed as a positive aspect of parenting. Now, in an age of fear, a parent, particularly a mother, can be judged as negligent – to the point of criminal prosecution – for actions like leaving a child to play in a park.

In the New York Times, writer Kim Brooks recounted her own story of leaving her 4-year-old son locked in a car on what she calls a “cool March day” so that she could run a quick errand. That fateful decision led to a series of encounters between Ms. Brooks and the criminal justice system, including a charge of “contributing to the delinquency of a minor.”

Ms. Brooks examined the challenges that mothers face in a world quick to pass judgment on their parenting decisions. She called those moral judgments “mother-shaming” and said that the judgments and risk assessments are intertwined.

“People don’t only think that leaving children alone is dangerous and therefore immoral. They also think it is immoral and therefore dangerous. said Barbara W. Sarnecka, PhD, a cognitive science professor at the University of California, Irvine, told Ms. Brooks. Dr. Sarnecka went on to say that, although children do not have the same rights as adults, “they have some rights, and not just to safety. They have the right to some freedom, to some independence, and to a little bit of danger.”

Click here to read the Time article.

Leaving children to fend for themselves used to be viewed as a positive aspect of parenting. Now, in an age of fear, a parent, particularly a mother, can be judged as negligent – to the point of criminal prosecution – for actions like leaving a child to play in a park.

In the New York Times, writer Kim Brooks recounted her own story of leaving her 4-year-old son locked in a car on what she calls a “cool March day” so that she could run a quick errand. That fateful decision led to a series of encounters between Ms. Brooks and the criminal justice system, including a charge of “contributing to the delinquency of a minor.”

Ms. Brooks examined the challenges that mothers face in a world quick to pass judgment on their parenting decisions. She called those moral judgments “mother-shaming” and said that the judgments and risk assessments are intertwined.

“People don’t only think that leaving children alone is dangerous and therefore immoral. They also think it is immoral and therefore dangerous. said Barbara W. Sarnecka, PhD, a cognitive science professor at the University of California, Irvine, told Ms. Brooks. Dr. Sarnecka went on to say that, although children do not have the same rights as adults, “they have some rights, and not just to safety. They have the right to some freedom, to some independence, and to a little bit of danger.”

Click here to read the Time article.

Leaving children to fend for themselves used to be viewed as a positive aspect of parenting. Now, in an age of fear, a parent, particularly a mother, can be judged as negligent – to the point of criminal prosecution – for actions like leaving a child to play in a park.

In the New York Times, writer Kim Brooks recounted her own story of leaving her 4-year-old son locked in a car on what she calls a “cool March day” so that she could run a quick errand. That fateful decision led to a series of encounters between Ms. Brooks and the criminal justice system, including a charge of “contributing to the delinquency of a minor.”

Ms. Brooks examined the challenges that mothers face in a world quick to pass judgment on their parenting decisions. She called those moral judgments “mother-shaming” and said that the judgments and risk assessments are intertwined.

“People don’t only think that leaving children alone is dangerous and therefore immoral. They also think it is immoral and therefore dangerous. said Barbara W. Sarnecka, PhD, a cognitive science professor at the University of California, Irvine, told Ms. Brooks. Dr. Sarnecka went on to say that, although children do not have the same rights as adults, “they have some rights, and not just to safety. They have the right to some freedom, to some independence, and to a little bit of danger.”

Click here to read the Time article.

Native American writer explores identity

The debut novel “There There” by Tommy Orange explores what it means to be Native American in contemporary urban America.

In an interview with the PBS Newshour, Mr. Orange, a member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes who grew up in Oakland, Calif., describes the ways in which living in an urban environment in an ethnically diverse American city can be isolating and lonely for Native Americans.

“We know the sound of the freeway better than we do rivers, the howl of distant trains better than wolf howls,” Mr. Orange said, reading from his book. “We know the smell of gas and freshly wet concrete and burned rubber better than we do the smell of cedar or sage or even frybread. We ride buses, trains, and cars across, over, and under concrete plains. Being Indian has never been about returning to the land. The land is everywhere or nowhere.”

For Mr. Orange, whose mother is white and father is Native American, identity in Oakland has been a fluid concept. “If I’m in the Fruitvale [area of Oakland], people will speak Spanish to me first,” he said in the interview.

Establishing identity can be a difficult task for Native Americans, Mr. Orange said, because parents often do not share stories about history – “sometimes because of pain,” he said.

To watch the PBS Newshour interview with Mr. Orange, click here.

The debut novel “There There” by Tommy Orange explores what it means to be Native American in contemporary urban America.

In an interview with the PBS Newshour, Mr. Orange, a member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes who grew up in Oakland, Calif., describes the ways in which living in an urban environment in an ethnically diverse American city can be isolating and lonely for Native Americans.

“We know the sound of the freeway better than we do rivers, the howl of distant trains better than wolf howls,” Mr. Orange said, reading from his book. “We know the smell of gas and freshly wet concrete and burned rubber better than we do the smell of cedar or sage or even frybread. We ride buses, trains, and cars across, over, and under concrete plains. Being Indian has never been about returning to the land. The land is everywhere or nowhere.”

For Mr. Orange, whose mother is white and father is Native American, identity in Oakland has been a fluid concept. “If I’m in the Fruitvale [area of Oakland], people will speak Spanish to me first,” he said in the interview.

Establishing identity can be a difficult task for Native Americans, Mr. Orange said, because parents often do not share stories about history – “sometimes because of pain,” he said.

To watch the PBS Newshour interview with Mr. Orange, click here.

The debut novel “There There” by Tommy Orange explores what it means to be Native American in contemporary urban America.

In an interview with the PBS Newshour, Mr. Orange, a member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes who grew up in Oakland, Calif., describes the ways in which living in an urban environment in an ethnically diverse American city can be isolating and lonely for Native Americans.

“We know the sound of the freeway better than we do rivers, the howl of distant trains better than wolf howls,” Mr. Orange said, reading from his book. “We know the smell of gas and freshly wet concrete and burned rubber better than we do the smell of cedar or sage or even frybread. We ride buses, trains, and cars across, over, and under concrete plains. Being Indian has never been about returning to the land. The land is everywhere or nowhere.”

For Mr. Orange, whose mother is white and father is Native American, identity in Oakland has been a fluid concept. “If I’m in the Fruitvale [area of Oakland], people will speak Spanish to me first,” he said in the interview.

Establishing identity can be a difficult task for Native Americans, Mr. Orange said, because parents often do not share stories about history – “sometimes because of pain,” he said.

To watch the PBS Newshour interview with Mr. Orange, click here.