User login

Diversion of Controlled Drugs in Hospitals: A Scoping Review of Contributors and Safeguards

The United States (US) and Canada are the two highest per-capita consumers of opioids in the world;1 both are struggling with unprecedented opioid-related mortality.2,3 The nonmedical use of opioids is facilitated by diversion and defined as the transfer of drugs from lawful to unlawful channels of use4,5 (eg, sharing legitimate prescriptions with family and friends6). Opioids and other controlled drugs are also diverted from healthcare facilities;4,5,7,8 Canadian data suggest these incidents may be increasing (controlled-drug loss reports have doubled each year since 20159).

The diversion of controlled drugs from hospitals affects patients, healthcare workers (HCWs), hospitals, and the public. Patients suffer insufficient analgesia or anesthesia, experience substandard care from impaired HCWs, and are at risk of infections from compromised syringes.4,10,11 HCWs that divert are at risk of overdose and death; they also face regulatory censure, criminal prosecution, and civil malpractice suits.12,13 Hospitals bear the cost of diverted drugs,14,15 internal investigations,4 and follow-up care for affected patients,4,13 and can be fined in excess of $4 million dollars for inadequate safeguards.16 Negative publicity highlights hospitals failing to self-regulate and report when diversion occurs, compromising public trust.17-19 Finally, diverted drugs impact population health by contributing to drug misuse.

Hospitals face a critical problem: how does a hospital prevent the diversion of controlled drugs? Hospitals have not yet implemented safeguards needed to detect or understand how diversion occurs. For example, 79% of Canadian hospital controlled-drug loss reports are “unexplained losses,”9 demonstrating a lack of traceability needed to understand the root causes of the loss. A single US endoscopy clinic showed that $10,000 of propofol was unaccounted for over a four-week period.14 Although transactional discrepancies do not equate to diversion, they are a potential signal of diversion and highlight areas for improvement.15 The hospital medication-use process (MUP; eg, procurement, storage, preparation, prescription, dispensing, administration, waste, return, and removal) has multiple vulnerabilities that have been exploited. Published accounts of diversion include falsification of clinical documents, substitution of saline for medication, and theft.4,20-23 Hospitals require guidance to assess their drug processes against known vulnerabilities and identify safeguards that may improve their capacity to prevent or detect diversion.

In this work, we provide a scoping review on the emerging topic of drug diversion to support hospitals. Scoping reviews can be a “preliminary attempt to provide an overview of existing literature that identifies areas where more research might be required.”24 Past literature has identified sources of drugs for nonmedical use,6,25,26 provided partial data on the quantities of stolen drug,7,8 and estimated the rate of HCW diversion.5,27-29 However, no reviews have focused on system gaps specific to hospital MUPs and diversion. Our review remedies this knowledge gap by consolidating known weaknesses and safeguards from peer- and nonpeer-reviewed articles. Drug diversion has been discussed at conferences and in news articles, case studies, and legal reports; excluding such discussion ignores substantive work that informs diversion practices in hospitals. Early indications suggest that hospitals have not yet implemented safeguards to properly identify when diversion has occurred, and consequently, lack the evidence to contribute to peer-reviewed literature. This article summarizes (1) clinical units, health professions, and stages of the MUP discussed, (2) contributors to diversion in hospitals, and (3) safeguards to prevent or detect diversion in hospitals.

METHODS

Scoping Review

We followed Arksey and O’Malley’s six-step framework for scoping reviews,30 with the exception of the optional consultation phase (step 6). We addressed three questions (step 1): what clinical units, health professions, or stages of the medication-use process are commonly discussed; what are the identified contributors to diversion in hospitals; and what safeguards have been described for prevention or detection of diversion in hospitals? We then identified relevant studies (step 2) by searching records published from January 2005 to June 2018 in MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Scopus, and Web of Science; the gray literature was also searched (see supplementary material for search terms).

All study designs were considered, including quantitative and qualitative methods, such as experiments, chart reviews and audit reports, surveys, focus groups, outbreak investigations, and literature reviews. Records were included (step 3) if abstracts met the Boolean logic criteria outlined in Appendix 1. If no abstract was available, then the full-text article was assessed. Prior to abstract screening, four reviewers (including R.R.) independently screened batches of 50 abstracts at a time to iteratively assess interrater reliability (IRR). Disagreements were resolved by consensus and the eligibility criteria were refined until IRR was achieved (Fleiss kappa > 0.65). Once IRR was achieved, the reviewers applied the criteria independently. For each eligible abstract, the full text was retrieved and assigned to a reviewer for independent assessment of eligibility. The abstract was reviewed if the full-text article was not available. Only articles published in English were included.

Reviewers charted findings from the full-text records (steps 4 and 5) by using themes defined a priori, specifically literature characteristics (eg, authors, year of publication), characteristics related to study method (eg, article type), variables related to our research questions (eg, variations by clinical unit, health profession), contributors to diversion, and safeguards to detect or prevent diversion. Inductive additions or modifications to the themes were proposed during the full-text review (eg, reviewers added a theme “name of drugs diverted” to identify drugs frequently reported as diverted) and accepted by consensus among the reviewers.

RESULTS

Scoping Review

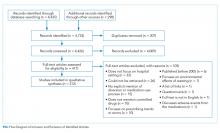

The literature search generated 4,733 records of which 307 were duplicates and 4,009 were excluded on the basis of the eligibility criteria. The reviewers achieved 100% interrater agreement on the fourth round of abstract screening. Upon full-text review, 312 articles were included for data abstraction (Figure).

Literature Characteristics

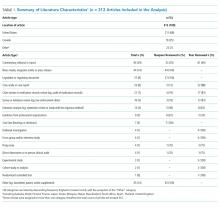

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the included literature. The articles were published in a mix of peer-reviewed (137, 44%) and nonpeer-reviewed (175, 56%) sources. Some peer-reviewed articles did not use research methods, and some nonpeer-reviewed articles used research methods (eg, doctoral theses). Therefore, Table 1 categorizes the articles by research method (if applicable) and by peer-review status. The articles primarily originated in the United States (211, 68%) followed by Canada (79, 25%) and other countries (22, 7%). Most articles were commentaries, editorials, reports or news media, rather than formal studies presenting original data.

Literature Focus by Clinical Unit, Health Profession, and Stage of Medication-Use Process

Most articles did not focus the discussion on any one clinical unit, health profession, or stage of the MUP. Of the articles that made explicit mention of clinical units, hospital pharmacies and operating rooms were discussed most often, nurses were the most frequently highlighted health profession, and most stages of the MUP were discussed equally, with the exception of prescribing which was mentioned the least (Supplementary Table).

Contributors to Diversion

The literature describes a variety of contributors to drug diversion. Table 2 organizes these contributors by stage of the MUP and provides references for further discussion.

The diverse and system-wide contributors to diversion described in Table 2 support inappropriate access to controlled drugs and can delay the detection of diversion after it occurred. These contributors are more likely to occur in organizations that fail to adhere to drug-handling practices or to carefully review practices.34,44

Diversion Safeguards in Hospitals

Table 3 summarizes published recommendations to mitigate the risk of diversion by stage of the MUP.

DISCUSSION

This review synthesizes a broad sample of peer- and nonpeer-reviewed literature to produce a consolidated list of known contributors (Table 2) and safeguards against (Table 3) controlled-drug diversion in hospitals. The literature describes an extensive list of ways drugs have been diverted in all stages of the MUP and can be exploited by all health professions in any clinical unit. Hospitals should be aware that nonclinical HCWs may also be at risk (eg, shipping and receiving personnel may handle drug shipments or returns, housekeeping may encounter partially filled vials in patient rooms). Patients and their families may also use some of the methods described in Table 2 (eg, acquiring fentanyl patches from unsecured waste receptacles and tampering with unsecured intravenous infusions).

Given the established presence of drug diversion in the literature,5,7-9,96,97 hospitals should assess their clinical practices against these findings, review the associated references, and refer to existing guidance to better understand the intricacies of the topic.7,31,51,53,60,79 To accommodate variability in practice between hospitals, we suggest considering two underlying issues that recur in Tables 2 and 3 that will allow hospitals to systematically analyze their unique practices for each stage of the MUP.

The first issue is falsification of clinical or inventory documentation. Falsified documents give the opportunity and appearance of legitimate drug transactions, obscure drug diversion, or create opportunities to collect additional drugs. Clinical documentation can be falsified actively (eg, deliberately falsifying verbal orders, falsifying drug amounts administered or wasted, and artificially increasing patients’ pain scores) or passively (eg, profiled automated dispensing cabinets [ADC] allow drug withdrawals for a patient that has been discharged or transferred over 72 hours ago because the system has not yet been updated).

The second issue involves failure to maintain the physical security of controlled drugs, thereby allowing unauthorized access. This issue includes failing to physically secure drug stock (eg, propping doors open to controlled-drug areas; failing to log out of ADCs, thereby facilitating unauthorized access; and leaving prepared drugs unsupervised in patient care areas) or failing to maintain accurate access credentials (eg, staff no longer working on the care unit still have access to the ADC or other secure areas). Prevention safeguards require adherence to existing security protocols (eg, locked doors and staff access frequently updated) and limiting the amount of controlled drugs that can be accessed (eg, supply on care unit should be minimized to what is needed and purchase smallest unit doses to minimize excess drug available to HCWs). Hospitals may need to consider if security measures are actually feasible for HCWs. For example, syringes of prepared drugs should not be left unsupervised to prevent risk of substitution or tampering; however, if the responsible HCW is also expected to collect supplies from outside the care area, they cannot be expected to maintain constant supervision. Detection safeguards include the use of tamper-evident packaging to support detection of compromised controlled drugs or assaying drug waste or other suspicious drug containers to detect dilution or tampering. Hospitals may also consider monitoring whether staff access controlled-drug areas when they are not scheduled to work to detect security breaches.

Safeguards for both issues benefit from an organizational culture reinforced through training at orientation and annually thereafter. Staff should be aware of reporting mechanisms (eg, anonymous hotlines), employee and professional assistance programs, self-reporting protocols, and treatment and rehabilitation options.10,12,29,47,72,91 Other system-wide safeguards described in Table 3 should also be considered. Detection of transactional discrepancies does not automatically indicate diversion, but recurrent discrepancies indicate a weakness in controlled-drug management and should be rectified; diversion prevention is a responsibility of all departments, not just the pharmacy.

Hospitals have several motivations to actively invest in safeguards. Drug diversion is a patient safety issue, a patient privacy issue (eg, patient records are inappropriately accessed to identify opportunities for diversion), an occupational health issue given the higher risks of opioid-related SUD faced by HCWs, a regulatory compliance issue, and a legal issue.31,41,46,59,78,98,99 Although individuals are accountable for drug diversion itself, hospitals should take adequate measures to prevent or detect diversion and protect patients and staff from associated harms. Hospitals should pay careful attention to the configuration of healthcare technologies, environments, and processes in their institution to reduce the opportunity for diversion.

Our study has several limitations. We did not include articles prior to 2005 because we captured a sizable amount of literature with the current search terms and wanted the majority of the studies to reflect workflow based on electronic health records and medication ordering, which only came into wide use in the past 15 years. Other possible contributors and safeguards against drug diversion may not be captured in our review. Nevertheless, thorough consideration of the two underlying issues described will help protect hospitals against new and emerging methods of diversion. The literature search yielded a paucity of controlled trials formally evaluating the effectiveness of these interventions, so safeguards identified in our review may not represent optimal strategies for responding to drug diversion. Lastly, not all suggestions may be applicable or effective in every institution.

CONCLUSION

Drug diversion in hospitals is a serious and urgent concern that requires immediate attention to mitigate harms. Past incidents of diversion have shown that hospitals have not yet implemented safeguards to fully account for drug losses, with resultant harms to patients, HCWs, hospitals themselves, and the general public. Further research is needed to identify system factors relevant to drug diversion, identify new safeguards, evaluate the effectiveness of known safeguards, and support adoption of best practices by hospitals and regulatory bodies.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Iveta Lewis and members of the HumanEra team (Carly Warren, Jessica Tomasi, Devika Jain, Maaike deVries, and Betty Chang) for screening and data extraction of the literature and to Peggy Robinson, Sylvia Hyland, and Sonia Pinkney for editing and commentary.

Disclosures

Ms. Reding and Ms. Hyland were employees of North York General Hospital at the time of this work. Dr. Hamilton and Ms. Tscheng are employees of ISMP Canada, a subcontractor to NYGH, during the conduct of the study. Mark Fan and Patricia Trbovich have received honoraria from BD Canada for presenting preliminary study findings at BD sponsored events.

Funding

This work was supported by Becton Dickinson (BD) Canada Inc. (grant #ROR2017-04260JH-NYGH). BD Canada had no involvement in study design; in the collection, analysis or interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

1. International Narcotics Control Board. Narcotic drugs: estimated world requirements for 2017 - statistics for 2015. https://www.incb.org/documents/Narcotic-Drugs/Technical-Publications/2016/Narcotic_Drugs_Publication_2016.pdf. Accessed February 2, 2018.

2. Gomes T, Tadrous M, Mamdani MM, Paterson JM, Juurlink DN. The burden of opioid-related mortality in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(2):e180217. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0217. PubMed

3. Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses. National report: apparent opioid-related deaths in Canada (December 2017). https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/apparent-opioid-related-deaths-report-2016-2017-december.html. Accessed June 5, 2018.

4. Berge KH, Dillon KR, Sikkink KM, Taylor TK, Lanier WL. Diversion of drugs within health care facilities, a multiple-victim crime: patterns of diversion, scope, consequences, detection, and prevention. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(7):674-682. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.03.013. PubMed

5. Inciardi JA, Surratt HL, Kurtz SP, Burke JJ. The diversion of prescription drugs by health care workers in Cincinnati, Ohio. Subst Use Misuse. 2006;41(2):255-264. doi: 10.1080/10826080500391829. PubMed

6. Hulme S, Bright D, Nielsen S. The source and diversion of pharmaceutical drugs for non-medical use: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;186:242-256. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.02.010. PubMed

7. Minnesota Hospital Association. Minnesota controlled substance diversion prevention coalition: final report. https://www.mnhospitals.org/Portals/0/Documents/ptsafety/diversion/drug-diversion-final-report-March2012.pdf. Accessed July 21, 2017.

8. Joranson DE, Gilson AM. Drug crime is a source of abused pain medications in the United States. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2005;30(4):299-301. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.09.001. PubMed

9. Carman T. Analysis of Health Canada missing controlled substances and precursors data (2017). Github. https://github.com/taracarman/drug_losses. Accessed July 1, 2018.

10. New K. Preventing, detecting, and investigating drug diversion in health care facilities. Mo State Board Nurs Newsl. 2014;5(4):11-14.

11. Schuppener LM, Pop-Vicas AE, Brooks EG, et al. Serratia marcescens Bacteremia: Nosocomial Clustercluster following narcotic diversion. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017;38(9):1027-1031. doi: 10.1017/ice.2017.137. PubMed

12. New K. Investigating institutional drug diversion. J Leg Nurse Consult. 2015;26(4):15-18. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2155-8256(15)30095-8

13. Berge KH, Lanier WL. Bloodstream infection outbreaks related to opioid-diverting health care workers: a cost-benefit analysis of prevention and detection programs. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89(7):866-868. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.04.010. PubMed

14. Horvath C. Implementation of a new method to track propofol in an endoscopy unit. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2017;15(3):102-110. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000112. PubMed

15. Pontore KM. The Epidemic of Controlled Substance Diversion Related to Healthcare Professionals. Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh; 2015.

16. Knowles M. Georgia health system to pay $4.1M settlement over thousands of unaccounted opioids. Becker’s Hospital Review. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/opioids/georgia-health-system-to-pay-4-1m-settlement-over-thousands-of-unaccounted-opioids.html. Accessed September 11, 2018.

17. Olinger D, Osher CN. Drug-addicted, dangerous and licensed for the operating room. The Denver Post. https://www.denverpost.com/2016/04/23/drug-addicted-dangerous-and-licensed-for-the-operating-room. Accessed August 2, 2017.

18. Levinson DR, Broadhurst ET. Why aren’t doctors drug tested? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/13/opinion/why-arent-doctors-drug-tested.html. Accessed July 21, 2017.

19. Eichenwald K. When Drug Addicts Work in Hospitals, No One is Safe. Newsweek. https://www.newsweek.com/2015/06/26/traveler-one-junkies-harrowing-journey-across-america-344125.html. Accessed August 2, 2017.

20. Martin ES, Dzierba SH, Jones DM. Preventing large-scale controlled substance diversion from within the pharmacy. Hosp Pharm. 2013;48(5):406-412. doi: 10.1310/hpj4805-406. PubMed

21. Institute for Safe Medication Practices. Partially filled vials and syringes in sharps containers are a key source of drugs for diversion. Medication safety alerts. https://www.ismp.org/resources/partially-filled-vials-and-syringes-sharps-containers-are-key-source-drugs-diversion?id=1132. Accessed June 29, 2017.

22. Fleming K, Boyle D, Lent WJB, Carpenter J, Linck C. A novel approach to monitoring the diversion of controlled substances: the role of the pharmacy compliance officer. Hosp Pharm. 2007;42(3):200-209. doi: 10.1310/hpj4203-200.

23. Merlo LJ, Cummings SM, Cottler LB. Prescription drug diversion among substance-impaired pharmacists. Am J Addict. 2014;23(2):123-128. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2013.12078.x. PubMed

24. O’Malley L, Croucher K. Housing and dementia care-a scoping review of the literature. Health Soc Care Commun. 2005;13(6):570-577. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2005.00588.x. PubMed

25. Fischer B, Bibby M, Bouchard M. The global diversion of pharmaceutical drugs non-medical use and diversion of psychotropic prescription drugs in North America: a review of sourcing routes and control measures. Addiction. 2010;105(12):2062-2070. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03092.x. PubMed

26. Inciardi JA, Surratt HL, Cicero TJ, et al. The “black box” of prescription drug diversion. J Addict Dis. 2009;28(4):332-347. doi: 10.1080/10550880903182986. PubMed

27. Boulis S, Khanduja PK, Downey K, Friedman Z. Substance abuse: a national survey of Canadian residency program directors and site chiefs at university-affiliated anesthesia departments. Can J Anesth. 2015;62(9):964-971. doi: 10.1007/s12630-015-0404-1. PubMed

28. Warner DO, Berge K, Sun H et al. Substance use disorder among anesthesiology residents, 1975-2009. JAMA. 2013;310(21):2289-2296. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281954. PubMed

29. Kunyk D. Substance use disorders among registered nurses: prevalence, risks and perceptions in a disciplinary jurisdiction. J Nurs Manag. 2015;23(1):54-64. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12081. PubMed

30. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19-32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. PubMed

31. Brummond PW, Chen DF, Churchill WW, et al. ASHP guidelines on preventing diversion of controlled substances. Am J Health System Pharm. 2017;74(5):325-348. doi: 10.2146/ajhp160919. PubMed

32. New K. Diversion risk rounds: a reality check on your drug-handling policies. http://www.diversionspecialists.com/wp-content/uploads/Diversion-Risk-Rounds-A-Reality-Check-on-Your-Drug-Handling-Policies.pdf. Accessed July 13, 2017.

33. New K. Uncovering Diversion: 6 case studies on Diversion. https://www.pppmag.com/article/2162. Accessed January 30, 2018.

34. New KS. Undertaking a System Wide Diversion Risk Assessment [PowerPoint]. International Health Facility Diversion Association Conference; 2016. Accessed July 14, 2016.

35. O’Neal B, Siegel J. Diversion in the pharmacy. Hosp Pharm. 2007;42(2):145-148. doi: 10.1310/hpj4202-145.

36. Holleran RS. What is wrong With this picture? J Emerg Nurs. 2010;36(5):396-397. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2010.08.005. PubMed

37. Vrabel R. Identifying and dealing with drug diversion. How hospitals can stay one step ahead. https://www.hcinnovationgropu.com/home/article/13003330/identifying-and-dealing-with-drug-diversion. Accessed September 18, 2017.

38. Mentler P. Preventing diversion in the ED. https://www.pppmag.com/article/1778. Accessed July 19, 2017.

39. Fernandez J. Hospitals wage battle against drug diversion. https://www.drugtopics.com/top-news/hospitals-wage-battle-against-drug-diversion. Accessed August 17, 2017.

40. Minnesota Hospital Association. Road map to controlled substance diversion Prevention 2.0. https://www.mnhospitals.org/Portals/0/Documents/ptsafety/diversion/Road Map to Controlled Substance Diversion Prevention 2.0.pdf. Accessed June 30, 2017.

41. Bryson EO, Silverstein JH. Addiction and substance abuse in anesthesiology. Anesthesiology. 2008;109(5):905-917. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181895bc1. PubMed

42. McCammon C. Diversion: a quiet threat in the healthcare setting. https://www.acep.org/Content.aspx?ID=94932. Accessed August 17, 2017.

43. Minnesota Hospital Association. Identifying potentially impaired practitioners [PowerPoint]. https://www.mnhospitals.org/Portals/0/Documents/ptsafety/diversion/potentially-impaired-practitioners.pdf. Accessed July 21, 2017.

44. Burger G, Burger M. Drug diversion: new approaches to an old problem. Am J Pharm Benefits. 2016;8(1):30-33.

45. Greenall J, Santora P, Koczmara C, Hyland S. Enhancing safe medication use for pediatric patients in the emergency department. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2009;62(2):150-153. doi: 10.4212/cjhp.v62i2.445. PubMed

46. New K. Avoid diversion practices that prompt DEA investigations. https://www.pppmag.com/article/1818. Accessed October 4, 2017.

47. New K. Detecting and responding to drug diversion. https://rxdiversion.com/detecting-and-responding-to-drug-diversion. Accessed July 13, 2017.

48. New KS. Institutional Diversion Prevention, Detection and Response [PowerPoint]. https://www.ncsbn.org/0613_DISC_Kim_New.pdf. Accessed August 25, 2017.

49. Siegel J, Forrey RA. Four case studies on diversion prevention. https://www.pppmag.com/article/1469/March_2014/Four_Case_Studies_on_Diversion_Prevention. Accessed July 31, 2017.

50. Copp MAB. Drug addiction among nurses: confronting a quiet epidemic-Many RNs fall prey to this hidden, potentially deadly disease. http://www.modernmedicine.com/modern-medicine/news/modernmedicine/modern-medicine-feature-articles/drug-addiction-among-nurses-con. Accessed September 8, 2017.

51. Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Public health vulnerability review: drug diversion, infection risk, and David Kwiatkowski’s employment as a healthcare worker in Maryland. https://health.maryland.gov/pdf/Public Health Vulnerability Review.pdf. Accessed July 21, 2017.

52. Warner AE, Schaefer MK, Patel PR, et al. Outbreak of hepatitis C virus infection associated with narcotics diversion by an hepatitis C virus-infected surgical technician. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43(1):53-58. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.09.012. PubMed

53. New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services-Division of Public Health Services. Hepatitis C outbreak investigation Exeter Hospital public report. https://www.dhhs.nh.gov/dphs/cdcs/hepatitisc/documents/hepc-outbreak-rpt.pdf . Accessed July 21, 2017.

54. Paparella SF. A tale of waste and loss: lessons learned. J Emerg Nurs. 2016;42(4):352-354. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2016.03.025. PubMed

55. Ramer LM. Using servant leadership to facilitate healing after a drug diversion experience. AORN J. 2008;88(2):253-258. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2008.05.002. PubMed

56. Siegel J, O’Neal B, Code N. Prevention of controlled substance diversion-Code N: multidisciplinary approach to proactive drug diversion prevention. Hosp Pharm. 2007;42(3):244-248. doi: 10.1310/hpj4203-244.

57. Saver C. Drug diversion in the OR: how can you keep it from happening? https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/f066/32113de065ca628a1f37218d18c654c15671.pdf. Accessed September 21, 2017.

58. Peterson DM. New DEA rules expand options for controlled substance disposal. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2015;29(1):22-26. doi: 10.3109/15360288.2014.1002964. PubMed

59. Lefebvre LG, Kaufmann IM. The identification and management of substance use disorders in anesthesiologists. Can J Anesth J Can Anesth. 2017;64(2):211-218. doi: 10.1007/s12630-016-0775-y. PubMed

60. Missouri Bureau of Narcotics & Dangerous Drugs. Drug diversion in hospitals-A guide to preventing and investigating diversion issues. https://health.mo.gov/safety/bndd/doc/drugdiversion.doc. Accessed July 21, 2017.

61. Hayes S. Pharmacy diversion: prevention, detection and monitoring: a pharmacy fraud investigator’s perspective. International Health Facility Diversion Association Conference 2016. Accessed July 5, 2017.

62. Schaefer MK, Perz JF. Outbreaks of infections associated with drug diversion by US health care personnel. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89(7):878-887. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.04.007. PubMed

63. Vigoda MM, Gencorelli FJ, Lubarsky DA. Discrepancies in medication entries between anesthetic and pharmacy records using electronic databases. Anesth Analg. 2007;105(4):1061-1065. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000282021.74832.5e. PubMed

64. Goodine C. Safety audit of automated dispensing cabinets. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2832564/. Accessed September 25, 2017.

65. Ontario College of Pharmacists. Hospital assessment criteria. http://www.ocpinfo.com/library/practice-related/download/library/practice-related/download/Hospital-Assessment-Criteria.pdf. Accessed August 30, 2017.

66. Lizza BD, Jagow B, Hensler D, et al. Impact of multiple daily clinical pharmacist-enforced assessments on time in target sedation range. J Pharm Pract. 2018;31(5):445-449. doi: 10.1177/0897190017729522. PubMed

67. Landro L. Hospitals address a drug problem: software and Robosts help secure and monitor medications. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/hospitals-address-a-drug-problem-1392762765. Accessed June 29, 2017.

68. Hyland S, Koczmara C, Salsman B, Musing ELS, Greenall J. Optimizing the use of automated dispensing cabinets. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2007;60(5):332-334. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4212/cjhp.v60i5.205

69. O’Neal B, Bass K, Siegel J. Diversion in the operating room. Hosp Pharm. 2007;42(4):359-363. doi: 10.1310/hpj4204-359.

70. White C, Malida J. Large pill theft shows challenge of securing hospital drugs. https://www.matrixhomecare.com/downloads/HRM060110.pdf. Accessed August 18, 2017.

71. Crowson K, Monk-Tutor M. Use of automated controlled substance cabinets for detection of diversion in US hospitals: a national study. Hosp Pharm. 2005;40(11):977-983. doi: 10.1177/001857870504001107.

72. National Council of State Boards of Nursing Inc. Substance use disorder in the workplace [chapter 6]. In: Substance Use Disorder in Nursing. Chicago: National Council of State Boards of Nursing Inc. https://www.ncsbn.org/SUDN_11.pdf. Accessed. July 21, 2017.

73. Swanson B-M. Preventing prescription drug diversions at your hospital. Campus Safety. http://www.campussafetymagazine.com/cs/preventing-prescription-drug-diversions-at-your-hospital. Accessed June 30, 2017.

74. O’Neal B, Siegel J. Prevention of controlled substance diversion—scope, strategy, and tactics: Code N: the intervention process. Hosp Pharm. 2007;42(7):633-656. doi: 10.1310/hpj4207-653

75. Mandrack M, Cohen MR, Featherling J, et al. Nursing best practices using automated dispensing cabinets: nurses’ key role in improving medication safety. Medsurg Nurs. 2012;21(3):134-139. PubMed

76. Berge KH, Seppala MD, Lanier WL. The anesthesiology community’s approach to opioid- and anesthetic-abusing personnel: time to change course. Anesthesiology. 2008;109(5):762-764. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31818a3814. PubMed

77. Gemensky J. The pharmacist’s role in surgery: the indispensable asset. US Pharm. 2015;40(3):HS8-HS12.

78. New K. Drug diversion: regulatory requirements and best practices. http://www.hospitalsafetycenter.com/content/328646/topic/ws_hsc_hsc.html. Accessed September 21, 2017.

79. Lahey T, Nelson WA. A proposed nationwide reporting system to satisfy the ethical obligation to prevent drug diversion-related transmission of hepatitis C in healthcare facilities. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(12):1816-1820. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ203. PubMed

80. Gavin KG

81. Tetzlaff J, Collins GB, Brown DL, et al. A strategy to prevent substance abuse in an academic anesthesiology department. J Clin Anesth. 2010;22(2):143-150. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2008.12.030. PubMed

82. Kintz P, Villain M, Dumestre V, Cirimele V. Evidence of addiction by anesthesiologists as documented by hair analysis. Forensic Sci Int. 2005;153(1):81-84. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2005.04.033. PubMed

83. Wolf CE, Poklis A. A rapid HPLC procedure for analysis of analgesic pharmaceutical mixtures for quality assurance and drug diversion testing. J Anal Toxicol. 2005;29(7):711-714. doi: 10.1093/jat/29.7.711. PubMed

84. Poklis JL, Mohs AJ, Wolf CE, Poklis A, Peace MR. Identification of drugs in parenteral pharmaceutical preparations from a quality assurance and a diversion program by direct analysis in real-time AccuTOF(TM)-mass spectrometry (Dart-MS). J Anal Toxicol. 2016;40(8):608-616. doi: 10.1093/jat/bkw065. PubMed

85. Pham JC, Pronovost PJ, Skipper GE. Identification of physician impairment. JAMA. 2013;309(20):2101-2102. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.4635. PubMed

86. Stolbach A, Nelson LS, Hoffman RS. Protection of patients from physician substance misuse. JAMA. 2013;310(13):1402-1403. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.277948. PubMed

87. Berge KH, McGlinch BP. The law of unintended consequences can never be repealed: the hazards of random urine drug screening of anesthesia providers. Anesth Analg. 2017;124(5):1397-1399. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001972. PubMed

88. Oreskovich MR, Caldeiro RM. Anesthesiologists recovering from chemical dependency: can they safely return to the operating room? Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(7):576-580. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60745-3. PubMed

89. Di Costanzo M. Road to recovery. http://rnao.ca/sites/rnao-ca/files-RNJ-JanFeb2015.pdf. Accessed September 28, 2017.

90. Selzer J. Protection of patients from physician substance misuse. JAMA. 2013;310(13):1402-1403. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.277948. PubMed

91. Wright RL. Drug diversion in nursing practice a call for professional accountability to recognize and respond. J Assoc Occup Health Prof Healthc. 2013;33(1):27-30. PubMed

92. Siegel J, O’Neal B, Wierwille C. The investigative process. Hosp Pharm. 2007;42(5):466-469. doi: 10.1310/hpj4205-466.

93. Brenn BR, Kim MA, Hilmas E. Development of a computerized monitoring program to identify narcotic diversion in a pediatric anesthesia practice. Am J Health System Pharm. 2015;72(16):1365-1372. doi: 10.2146/ajhp140691. PubMed

94. Drug diversion sting goes wrong and privacy is questioned. http://www.reliasmedia.com/articles/138142-drug-diversion-sting-goes-wrong-and-privacy-is-questioned. Accessed September 21, 2017.

95. New K. Drug diversion defined: steps to prevent, detect, and respond to drug diversion in facilities. CDC’s healthcare blog. https://blogs.cdc.gov/safehealthcare/drug-diversion-defined-steps-to-prevent-detect-and-respond-to-drug-diversion-in-facilities. Accessed July 21, 2017.

96. Howorun C. ‘Unexplained losses’ of opioids on the rise in Canadian hospitals. Maclean’s. http://www.macleans.ca/society/health/unexplained-losses-of-opioids-on-the-rise-in-canadian-hospitals. Accessed December 5, 2017.

97. Carman T. When prescription opioids run out, users look for the supply on the streets. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/when-prescription-opioids-run-out-users-look-for-the-supply-on-the-streets-1.4720952. Accessed July 1, 2018.

98. Tanga HY. Nurse drug diversion and nursing leader’s responsibilities: legal, regulatory, ethical, humanistic, and practical considerations. JONAs Healthc Law Eth Regul. 2011;13(1):13-16. doi: 10.1097/NHL.0b013e31820bd9e6. PubMed

99. Scholze AR, Martins JT, Galdino MJQ, Ribeiro RP. Occupational environment and psychoactive substance consumption among nurses. Acta Paul Enferm. 2017;30(4):404-411. doi: 10.1590/1982-0194201700060.

The United States (US) and Canada are the two highest per-capita consumers of opioids in the world;1 both are struggling with unprecedented opioid-related mortality.2,3 The nonmedical use of opioids is facilitated by diversion and defined as the transfer of drugs from lawful to unlawful channels of use4,5 (eg, sharing legitimate prescriptions with family and friends6). Opioids and other controlled drugs are also diverted from healthcare facilities;4,5,7,8 Canadian data suggest these incidents may be increasing (controlled-drug loss reports have doubled each year since 20159).

The diversion of controlled drugs from hospitals affects patients, healthcare workers (HCWs), hospitals, and the public. Patients suffer insufficient analgesia or anesthesia, experience substandard care from impaired HCWs, and are at risk of infections from compromised syringes.4,10,11 HCWs that divert are at risk of overdose and death; they also face regulatory censure, criminal prosecution, and civil malpractice suits.12,13 Hospitals bear the cost of diverted drugs,14,15 internal investigations,4 and follow-up care for affected patients,4,13 and can be fined in excess of $4 million dollars for inadequate safeguards.16 Negative publicity highlights hospitals failing to self-regulate and report when diversion occurs, compromising public trust.17-19 Finally, diverted drugs impact population health by contributing to drug misuse.

Hospitals face a critical problem: how does a hospital prevent the diversion of controlled drugs? Hospitals have not yet implemented safeguards needed to detect or understand how diversion occurs. For example, 79% of Canadian hospital controlled-drug loss reports are “unexplained losses,”9 demonstrating a lack of traceability needed to understand the root causes of the loss. A single US endoscopy clinic showed that $10,000 of propofol was unaccounted for over a four-week period.14 Although transactional discrepancies do not equate to diversion, they are a potential signal of diversion and highlight areas for improvement.15 The hospital medication-use process (MUP; eg, procurement, storage, preparation, prescription, dispensing, administration, waste, return, and removal) has multiple vulnerabilities that have been exploited. Published accounts of diversion include falsification of clinical documents, substitution of saline for medication, and theft.4,20-23 Hospitals require guidance to assess their drug processes against known vulnerabilities and identify safeguards that may improve their capacity to prevent or detect diversion.

In this work, we provide a scoping review on the emerging topic of drug diversion to support hospitals. Scoping reviews can be a “preliminary attempt to provide an overview of existing literature that identifies areas where more research might be required.”24 Past literature has identified sources of drugs for nonmedical use,6,25,26 provided partial data on the quantities of stolen drug,7,8 and estimated the rate of HCW diversion.5,27-29 However, no reviews have focused on system gaps specific to hospital MUPs and diversion. Our review remedies this knowledge gap by consolidating known weaknesses and safeguards from peer- and nonpeer-reviewed articles. Drug diversion has been discussed at conferences and in news articles, case studies, and legal reports; excluding such discussion ignores substantive work that informs diversion practices in hospitals. Early indications suggest that hospitals have not yet implemented safeguards to properly identify when diversion has occurred, and consequently, lack the evidence to contribute to peer-reviewed literature. This article summarizes (1) clinical units, health professions, and stages of the MUP discussed, (2) contributors to diversion in hospitals, and (3) safeguards to prevent or detect diversion in hospitals.

METHODS

Scoping Review

We followed Arksey and O’Malley’s six-step framework for scoping reviews,30 with the exception of the optional consultation phase (step 6). We addressed three questions (step 1): what clinical units, health professions, or stages of the medication-use process are commonly discussed; what are the identified contributors to diversion in hospitals; and what safeguards have been described for prevention or detection of diversion in hospitals? We then identified relevant studies (step 2) by searching records published from January 2005 to June 2018 in MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Scopus, and Web of Science; the gray literature was also searched (see supplementary material for search terms).

All study designs were considered, including quantitative and qualitative methods, such as experiments, chart reviews and audit reports, surveys, focus groups, outbreak investigations, and literature reviews. Records were included (step 3) if abstracts met the Boolean logic criteria outlined in Appendix 1. If no abstract was available, then the full-text article was assessed. Prior to abstract screening, four reviewers (including R.R.) independently screened batches of 50 abstracts at a time to iteratively assess interrater reliability (IRR). Disagreements were resolved by consensus and the eligibility criteria were refined until IRR was achieved (Fleiss kappa > 0.65). Once IRR was achieved, the reviewers applied the criteria independently. For each eligible abstract, the full text was retrieved and assigned to a reviewer for independent assessment of eligibility. The abstract was reviewed if the full-text article was not available. Only articles published in English were included.

Reviewers charted findings from the full-text records (steps 4 and 5) by using themes defined a priori, specifically literature characteristics (eg, authors, year of publication), characteristics related to study method (eg, article type), variables related to our research questions (eg, variations by clinical unit, health profession), contributors to diversion, and safeguards to detect or prevent diversion. Inductive additions or modifications to the themes were proposed during the full-text review (eg, reviewers added a theme “name of drugs diverted” to identify drugs frequently reported as diverted) and accepted by consensus among the reviewers.

RESULTS

Scoping Review

The literature search generated 4,733 records of which 307 were duplicates and 4,009 were excluded on the basis of the eligibility criteria. The reviewers achieved 100% interrater agreement on the fourth round of abstract screening. Upon full-text review, 312 articles were included for data abstraction (Figure).

Literature Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the included literature. The articles were published in a mix of peer-reviewed (137, 44%) and nonpeer-reviewed (175, 56%) sources. Some peer-reviewed articles did not use research methods, and some nonpeer-reviewed articles used research methods (eg, doctoral theses). Therefore, Table 1 categorizes the articles by research method (if applicable) and by peer-review status. The articles primarily originated in the United States (211, 68%) followed by Canada (79, 25%) and other countries (22, 7%). Most articles were commentaries, editorials, reports or news media, rather than formal studies presenting original data.

Literature Focus by Clinical Unit, Health Profession, and Stage of Medication-Use Process

Most articles did not focus the discussion on any one clinical unit, health profession, or stage of the MUP. Of the articles that made explicit mention of clinical units, hospital pharmacies and operating rooms were discussed most often, nurses were the most frequently highlighted health profession, and most stages of the MUP were discussed equally, with the exception of prescribing which was mentioned the least (Supplementary Table).

Contributors to Diversion

The literature describes a variety of contributors to drug diversion. Table 2 organizes these contributors by stage of the MUP and provides references for further discussion.

The diverse and system-wide contributors to diversion described in Table 2 support inappropriate access to controlled drugs and can delay the detection of diversion after it occurred. These contributors are more likely to occur in organizations that fail to adhere to drug-handling practices or to carefully review practices.34,44

Diversion Safeguards in Hospitals

Table 3 summarizes published recommendations to mitigate the risk of diversion by stage of the MUP.

DISCUSSION

This review synthesizes a broad sample of peer- and nonpeer-reviewed literature to produce a consolidated list of known contributors (Table 2) and safeguards against (Table 3) controlled-drug diversion in hospitals. The literature describes an extensive list of ways drugs have been diverted in all stages of the MUP and can be exploited by all health professions in any clinical unit. Hospitals should be aware that nonclinical HCWs may also be at risk (eg, shipping and receiving personnel may handle drug shipments or returns, housekeeping may encounter partially filled vials in patient rooms). Patients and their families may also use some of the methods described in Table 2 (eg, acquiring fentanyl patches from unsecured waste receptacles and tampering with unsecured intravenous infusions).

Given the established presence of drug diversion in the literature,5,7-9,96,97 hospitals should assess their clinical practices against these findings, review the associated references, and refer to existing guidance to better understand the intricacies of the topic.7,31,51,53,60,79 To accommodate variability in practice between hospitals, we suggest considering two underlying issues that recur in Tables 2 and 3 that will allow hospitals to systematically analyze their unique practices for each stage of the MUP.

The first issue is falsification of clinical or inventory documentation. Falsified documents give the opportunity and appearance of legitimate drug transactions, obscure drug diversion, or create opportunities to collect additional drugs. Clinical documentation can be falsified actively (eg, deliberately falsifying verbal orders, falsifying drug amounts administered or wasted, and artificially increasing patients’ pain scores) or passively (eg, profiled automated dispensing cabinets [ADC] allow drug withdrawals for a patient that has been discharged or transferred over 72 hours ago because the system has not yet been updated).

The second issue involves failure to maintain the physical security of controlled drugs, thereby allowing unauthorized access. This issue includes failing to physically secure drug stock (eg, propping doors open to controlled-drug areas; failing to log out of ADCs, thereby facilitating unauthorized access; and leaving prepared drugs unsupervised in patient care areas) or failing to maintain accurate access credentials (eg, staff no longer working on the care unit still have access to the ADC or other secure areas). Prevention safeguards require adherence to existing security protocols (eg, locked doors and staff access frequently updated) and limiting the amount of controlled drugs that can be accessed (eg, supply on care unit should be minimized to what is needed and purchase smallest unit doses to minimize excess drug available to HCWs). Hospitals may need to consider if security measures are actually feasible for HCWs. For example, syringes of prepared drugs should not be left unsupervised to prevent risk of substitution or tampering; however, if the responsible HCW is also expected to collect supplies from outside the care area, they cannot be expected to maintain constant supervision. Detection safeguards include the use of tamper-evident packaging to support detection of compromised controlled drugs or assaying drug waste or other suspicious drug containers to detect dilution or tampering. Hospitals may also consider monitoring whether staff access controlled-drug areas when they are not scheduled to work to detect security breaches.

Safeguards for both issues benefit from an organizational culture reinforced through training at orientation and annually thereafter. Staff should be aware of reporting mechanisms (eg, anonymous hotlines), employee and professional assistance programs, self-reporting protocols, and treatment and rehabilitation options.10,12,29,47,72,91 Other system-wide safeguards described in Table 3 should also be considered. Detection of transactional discrepancies does not automatically indicate diversion, but recurrent discrepancies indicate a weakness in controlled-drug management and should be rectified; diversion prevention is a responsibility of all departments, not just the pharmacy.

Hospitals have several motivations to actively invest in safeguards. Drug diversion is a patient safety issue, a patient privacy issue (eg, patient records are inappropriately accessed to identify opportunities for diversion), an occupational health issue given the higher risks of opioid-related SUD faced by HCWs, a regulatory compliance issue, and a legal issue.31,41,46,59,78,98,99 Although individuals are accountable for drug diversion itself, hospitals should take adequate measures to prevent or detect diversion and protect patients and staff from associated harms. Hospitals should pay careful attention to the configuration of healthcare technologies, environments, and processes in their institution to reduce the opportunity for diversion.

Our study has several limitations. We did not include articles prior to 2005 because we captured a sizable amount of literature with the current search terms and wanted the majority of the studies to reflect workflow based on electronic health records and medication ordering, which only came into wide use in the past 15 years. Other possible contributors and safeguards against drug diversion may not be captured in our review. Nevertheless, thorough consideration of the two underlying issues described will help protect hospitals against new and emerging methods of diversion. The literature search yielded a paucity of controlled trials formally evaluating the effectiveness of these interventions, so safeguards identified in our review may not represent optimal strategies for responding to drug diversion. Lastly, not all suggestions may be applicable or effective in every institution.

CONCLUSION

Drug diversion in hospitals is a serious and urgent concern that requires immediate attention to mitigate harms. Past incidents of diversion have shown that hospitals have not yet implemented safeguards to fully account for drug losses, with resultant harms to patients, HCWs, hospitals themselves, and the general public. Further research is needed to identify system factors relevant to drug diversion, identify new safeguards, evaluate the effectiveness of known safeguards, and support adoption of best practices by hospitals and regulatory bodies.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Iveta Lewis and members of the HumanEra team (Carly Warren, Jessica Tomasi, Devika Jain, Maaike deVries, and Betty Chang) for screening and data extraction of the literature and to Peggy Robinson, Sylvia Hyland, and Sonia Pinkney for editing and commentary.

Disclosures

Ms. Reding and Ms. Hyland were employees of North York General Hospital at the time of this work. Dr. Hamilton and Ms. Tscheng are employees of ISMP Canada, a subcontractor to NYGH, during the conduct of the study. Mark Fan and Patricia Trbovich have received honoraria from BD Canada for presenting preliminary study findings at BD sponsored events.

Funding

This work was supported by Becton Dickinson (BD) Canada Inc. (grant #ROR2017-04260JH-NYGH). BD Canada had no involvement in study design; in the collection, analysis or interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

The United States (US) and Canada are the two highest per-capita consumers of opioids in the world;1 both are struggling with unprecedented opioid-related mortality.2,3 The nonmedical use of opioids is facilitated by diversion and defined as the transfer of drugs from lawful to unlawful channels of use4,5 (eg, sharing legitimate prescriptions with family and friends6). Opioids and other controlled drugs are also diverted from healthcare facilities;4,5,7,8 Canadian data suggest these incidents may be increasing (controlled-drug loss reports have doubled each year since 20159).

The diversion of controlled drugs from hospitals affects patients, healthcare workers (HCWs), hospitals, and the public. Patients suffer insufficient analgesia or anesthesia, experience substandard care from impaired HCWs, and are at risk of infections from compromised syringes.4,10,11 HCWs that divert are at risk of overdose and death; they also face regulatory censure, criminal prosecution, and civil malpractice suits.12,13 Hospitals bear the cost of diverted drugs,14,15 internal investigations,4 and follow-up care for affected patients,4,13 and can be fined in excess of $4 million dollars for inadequate safeguards.16 Negative publicity highlights hospitals failing to self-regulate and report when diversion occurs, compromising public trust.17-19 Finally, diverted drugs impact population health by contributing to drug misuse.

Hospitals face a critical problem: how does a hospital prevent the diversion of controlled drugs? Hospitals have not yet implemented safeguards needed to detect or understand how diversion occurs. For example, 79% of Canadian hospital controlled-drug loss reports are “unexplained losses,”9 demonstrating a lack of traceability needed to understand the root causes of the loss. A single US endoscopy clinic showed that $10,000 of propofol was unaccounted for over a four-week period.14 Although transactional discrepancies do not equate to diversion, they are a potential signal of diversion and highlight areas for improvement.15 The hospital medication-use process (MUP; eg, procurement, storage, preparation, prescription, dispensing, administration, waste, return, and removal) has multiple vulnerabilities that have been exploited. Published accounts of diversion include falsification of clinical documents, substitution of saline for medication, and theft.4,20-23 Hospitals require guidance to assess their drug processes against known vulnerabilities and identify safeguards that may improve their capacity to prevent or detect diversion.

In this work, we provide a scoping review on the emerging topic of drug diversion to support hospitals. Scoping reviews can be a “preliminary attempt to provide an overview of existing literature that identifies areas where more research might be required.”24 Past literature has identified sources of drugs for nonmedical use,6,25,26 provided partial data on the quantities of stolen drug,7,8 and estimated the rate of HCW diversion.5,27-29 However, no reviews have focused on system gaps specific to hospital MUPs and diversion. Our review remedies this knowledge gap by consolidating known weaknesses and safeguards from peer- and nonpeer-reviewed articles. Drug diversion has been discussed at conferences and in news articles, case studies, and legal reports; excluding such discussion ignores substantive work that informs diversion practices in hospitals. Early indications suggest that hospitals have not yet implemented safeguards to properly identify when diversion has occurred, and consequently, lack the evidence to contribute to peer-reviewed literature. This article summarizes (1) clinical units, health professions, and stages of the MUP discussed, (2) contributors to diversion in hospitals, and (3) safeguards to prevent or detect diversion in hospitals.

METHODS

Scoping Review

We followed Arksey and O’Malley’s six-step framework for scoping reviews,30 with the exception of the optional consultation phase (step 6). We addressed three questions (step 1): what clinical units, health professions, or stages of the medication-use process are commonly discussed; what are the identified contributors to diversion in hospitals; and what safeguards have been described for prevention or detection of diversion in hospitals? We then identified relevant studies (step 2) by searching records published from January 2005 to June 2018 in MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Scopus, and Web of Science; the gray literature was also searched (see supplementary material for search terms).

All study designs were considered, including quantitative and qualitative methods, such as experiments, chart reviews and audit reports, surveys, focus groups, outbreak investigations, and literature reviews. Records were included (step 3) if abstracts met the Boolean logic criteria outlined in Appendix 1. If no abstract was available, then the full-text article was assessed. Prior to abstract screening, four reviewers (including R.R.) independently screened batches of 50 abstracts at a time to iteratively assess interrater reliability (IRR). Disagreements were resolved by consensus and the eligibility criteria were refined until IRR was achieved (Fleiss kappa > 0.65). Once IRR was achieved, the reviewers applied the criteria independently. For each eligible abstract, the full text was retrieved and assigned to a reviewer for independent assessment of eligibility. The abstract was reviewed if the full-text article was not available. Only articles published in English were included.

Reviewers charted findings from the full-text records (steps 4 and 5) by using themes defined a priori, specifically literature characteristics (eg, authors, year of publication), characteristics related to study method (eg, article type), variables related to our research questions (eg, variations by clinical unit, health profession), contributors to diversion, and safeguards to detect or prevent diversion. Inductive additions or modifications to the themes were proposed during the full-text review (eg, reviewers added a theme “name of drugs diverted” to identify drugs frequently reported as diverted) and accepted by consensus among the reviewers.

RESULTS

Scoping Review

The literature search generated 4,733 records of which 307 were duplicates and 4,009 were excluded on the basis of the eligibility criteria. The reviewers achieved 100% interrater agreement on the fourth round of abstract screening. Upon full-text review, 312 articles were included for data abstraction (Figure).

Literature Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the included literature. The articles were published in a mix of peer-reviewed (137, 44%) and nonpeer-reviewed (175, 56%) sources. Some peer-reviewed articles did not use research methods, and some nonpeer-reviewed articles used research methods (eg, doctoral theses). Therefore, Table 1 categorizes the articles by research method (if applicable) and by peer-review status. The articles primarily originated in the United States (211, 68%) followed by Canada (79, 25%) and other countries (22, 7%). Most articles were commentaries, editorials, reports or news media, rather than formal studies presenting original data.

Literature Focus by Clinical Unit, Health Profession, and Stage of Medication-Use Process

Most articles did not focus the discussion on any one clinical unit, health profession, or stage of the MUP. Of the articles that made explicit mention of clinical units, hospital pharmacies and operating rooms were discussed most often, nurses were the most frequently highlighted health profession, and most stages of the MUP were discussed equally, with the exception of prescribing which was mentioned the least (Supplementary Table).

Contributors to Diversion

The literature describes a variety of contributors to drug diversion. Table 2 organizes these contributors by stage of the MUP and provides references for further discussion.

The diverse and system-wide contributors to diversion described in Table 2 support inappropriate access to controlled drugs and can delay the detection of diversion after it occurred. These contributors are more likely to occur in organizations that fail to adhere to drug-handling practices or to carefully review practices.34,44

Diversion Safeguards in Hospitals

Table 3 summarizes published recommendations to mitigate the risk of diversion by stage of the MUP.

DISCUSSION

This review synthesizes a broad sample of peer- and nonpeer-reviewed literature to produce a consolidated list of known contributors (Table 2) and safeguards against (Table 3) controlled-drug diversion in hospitals. The literature describes an extensive list of ways drugs have been diverted in all stages of the MUP and can be exploited by all health professions in any clinical unit. Hospitals should be aware that nonclinical HCWs may also be at risk (eg, shipping and receiving personnel may handle drug shipments or returns, housekeeping may encounter partially filled vials in patient rooms). Patients and their families may also use some of the methods described in Table 2 (eg, acquiring fentanyl patches from unsecured waste receptacles and tampering with unsecured intravenous infusions).

Given the established presence of drug diversion in the literature,5,7-9,96,97 hospitals should assess their clinical practices against these findings, review the associated references, and refer to existing guidance to better understand the intricacies of the topic.7,31,51,53,60,79 To accommodate variability in practice between hospitals, we suggest considering two underlying issues that recur in Tables 2 and 3 that will allow hospitals to systematically analyze their unique practices for each stage of the MUP.

The first issue is falsification of clinical or inventory documentation. Falsified documents give the opportunity and appearance of legitimate drug transactions, obscure drug diversion, or create opportunities to collect additional drugs. Clinical documentation can be falsified actively (eg, deliberately falsifying verbal orders, falsifying drug amounts administered or wasted, and artificially increasing patients’ pain scores) or passively (eg, profiled automated dispensing cabinets [ADC] allow drug withdrawals for a patient that has been discharged or transferred over 72 hours ago because the system has not yet been updated).

The second issue involves failure to maintain the physical security of controlled drugs, thereby allowing unauthorized access. This issue includes failing to physically secure drug stock (eg, propping doors open to controlled-drug areas; failing to log out of ADCs, thereby facilitating unauthorized access; and leaving prepared drugs unsupervised in patient care areas) or failing to maintain accurate access credentials (eg, staff no longer working on the care unit still have access to the ADC or other secure areas). Prevention safeguards require adherence to existing security protocols (eg, locked doors and staff access frequently updated) and limiting the amount of controlled drugs that can be accessed (eg, supply on care unit should be minimized to what is needed and purchase smallest unit doses to minimize excess drug available to HCWs). Hospitals may need to consider if security measures are actually feasible for HCWs. For example, syringes of prepared drugs should not be left unsupervised to prevent risk of substitution or tampering; however, if the responsible HCW is also expected to collect supplies from outside the care area, they cannot be expected to maintain constant supervision. Detection safeguards include the use of tamper-evident packaging to support detection of compromised controlled drugs or assaying drug waste or other suspicious drug containers to detect dilution or tampering. Hospitals may also consider monitoring whether staff access controlled-drug areas when they are not scheduled to work to detect security breaches.

Safeguards for both issues benefit from an organizational culture reinforced through training at orientation and annually thereafter. Staff should be aware of reporting mechanisms (eg, anonymous hotlines), employee and professional assistance programs, self-reporting protocols, and treatment and rehabilitation options.10,12,29,47,72,91 Other system-wide safeguards described in Table 3 should also be considered. Detection of transactional discrepancies does not automatically indicate diversion, but recurrent discrepancies indicate a weakness in controlled-drug management and should be rectified; diversion prevention is a responsibility of all departments, not just the pharmacy.

Hospitals have several motivations to actively invest in safeguards. Drug diversion is a patient safety issue, a patient privacy issue (eg, patient records are inappropriately accessed to identify opportunities for diversion), an occupational health issue given the higher risks of opioid-related SUD faced by HCWs, a regulatory compliance issue, and a legal issue.31,41,46,59,78,98,99 Although individuals are accountable for drug diversion itself, hospitals should take adequate measures to prevent or detect diversion and protect patients and staff from associated harms. Hospitals should pay careful attention to the configuration of healthcare technologies, environments, and processes in their institution to reduce the opportunity for diversion.

Our study has several limitations. We did not include articles prior to 2005 because we captured a sizable amount of literature with the current search terms and wanted the majority of the studies to reflect workflow based on electronic health records and medication ordering, which only came into wide use in the past 15 years. Other possible contributors and safeguards against drug diversion may not be captured in our review. Nevertheless, thorough consideration of the two underlying issues described will help protect hospitals against new and emerging methods of diversion. The literature search yielded a paucity of controlled trials formally evaluating the effectiveness of these interventions, so safeguards identified in our review may not represent optimal strategies for responding to drug diversion. Lastly, not all suggestions may be applicable or effective in every institution.

CONCLUSION

Drug diversion in hospitals is a serious and urgent concern that requires immediate attention to mitigate harms. Past incidents of diversion have shown that hospitals have not yet implemented safeguards to fully account for drug losses, with resultant harms to patients, HCWs, hospitals themselves, and the general public. Further research is needed to identify system factors relevant to drug diversion, identify new safeguards, evaluate the effectiveness of known safeguards, and support adoption of best practices by hospitals and regulatory bodies.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Iveta Lewis and members of the HumanEra team (Carly Warren, Jessica Tomasi, Devika Jain, Maaike deVries, and Betty Chang) for screening and data extraction of the literature and to Peggy Robinson, Sylvia Hyland, and Sonia Pinkney for editing and commentary.

Disclosures

Ms. Reding and Ms. Hyland were employees of North York General Hospital at the time of this work. Dr. Hamilton and Ms. Tscheng are employees of ISMP Canada, a subcontractor to NYGH, during the conduct of the study. Mark Fan and Patricia Trbovich have received honoraria from BD Canada for presenting preliminary study findings at BD sponsored events.

Funding

This work was supported by Becton Dickinson (BD) Canada Inc. (grant #ROR2017-04260JH-NYGH). BD Canada had no involvement in study design; in the collection, analysis or interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

1. International Narcotics Control Board. Narcotic drugs: estimated world requirements for 2017 - statistics for 2015. https://www.incb.org/documents/Narcotic-Drugs/Technical-Publications/2016/Narcotic_Drugs_Publication_2016.pdf. Accessed February 2, 2018.

2. Gomes T, Tadrous M, Mamdani MM, Paterson JM, Juurlink DN. The burden of opioid-related mortality in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(2):e180217. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0217. PubMed

3. Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses. National report: apparent opioid-related deaths in Canada (December 2017). https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/apparent-opioid-related-deaths-report-2016-2017-december.html. Accessed June 5, 2018.

4. Berge KH, Dillon KR, Sikkink KM, Taylor TK, Lanier WL. Diversion of drugs within health care facilities, a multiple-victim crime: patterns of diversion, scope, consequences, detection, and prevention. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(7):674-682. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.03.013. PubMed

5. Inciardi JA, Surratt HL, Kurtz SP, Burke JJ. The diversion of prescription drugs by health care workers in Cincinnati, Ohio. Subst Use Misuse. 2006;41(2):255-264. doi: 10.1080/10826080500391829. PubMed

6. Hulme S, Bright D, Nielsen S. The source and diversion of pharmaceutical drugs for non-medical use: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;186:242-256. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.02.010. PubMed

7. Minnesota Hospital Association. Minnesota controlled substance diversion prevention coalition: final report. https://www.mnhospitals.org/Portals/0/Documents/ptsafety/diversion/drug-diversion-final-report-March2012.pdf. Accessed July 21, 2017.

8. Joranson DE, Gilson AM. Drug crime is a source of abused pain medications in the United States. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2005;30(4):299-301. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.09.001. PubMed

9. Carman T. Analysis of Health Canada missing controlled substances and precursors data (2017). Github. https://github.com/taracarman/drug_losses. Accessed July 1, 2018.

10. New K. Preventing, detecting, and investigating drug diversion in health care facilities. Mo State Board Nurs Newsl. 2014;5(4):11-14.

11. Schuppener LM, Pop-Vicas AE, Brooks EG, et al. Serratia marcescens Bacteremia: Nosocomial Clustercluster following narcotic diversion. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017;38(9):1027-1031. doi: 10.1017/ice.2017.137. PubMed

12. New K. Investigating institutional drug diversion. J Leg Nurse Consult. 2015;26(4):15-18. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2155-8256(15)30095-8

13. Berge KH, Lanier WL. Bloodstream infection outbreaks related to opioid-diverting health care workers: a cost-benefit analysis of prevention and detection programs. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89(7):866-868. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.04.010. PubMed

14. Horvath C. Implementation of a new method to track propofol in an endoscopy unit. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2017;15(3):102-110. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000112. PubMed

15. Pontore KM. The Epidemic of Controlled Substance Diversion Related to Healthcare Professionals. Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh; 2015.

16. Knowles M. Georgia health system to pay $4.1M settlement over thousands of unaccounted opioids. Becker’s Hospital Review. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/opioids/georgia-health-system-to-pay-4-1m-settlement-over-thousands-of-unaccounted-opioids.html. Accessed September 11, 2018.

17. Olinger D, Osher CN. Drug-addicted, dangerous and licensed for the operating room. The Denver Post. https://www.denverpost.com/2016/04/23/drug-addicted-dangerous-and-licensed-for-the-operating-room. Accessed August 2, 2017.

18. Levinson DR, Broadhurst ET. Why aren’t doctors drug tested? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/13/opinion/why-arent-doctors-drug-tested.html. Accessed July 21, 2017.

19. Eichenwald K. When Drug Addicts Work in Hospitals, No One is Safe. Newsweek. https://www.newsweek.com/2015/06/26/traveler-one-junkies-harrowing-journey-across-america-344125.html. Accessed August 2, 2017.

20. Martin ES, Dzierba SH, Jones DM. Preventing large-scale controlled substance diversion from within the pharmacy. Hosp Pharm. 2013;48(5):406-412. doi: 10.1310/hpj4805-406. PubMed

21. Institute for Safe Medication Practices. Partially filled vials and syringes in sharps containers are a key source of drugs for diversion. Medication safety alerts. https://www.ismp.org/resources/partially-filled-vials-and-syringes-sharps-containers-are-key-source-drugs-diversion?id=1132. Accessed June 29, 2017.

22. Fleming K, Boyle D, Lent WJB, Carpenter J, Linck C. A novel approach to monitoring the diversion of controlled substances: the role of the pharmacy compliance officer. Hosp Pharm. 2007;42(3):200-209. doi: 10.1310/hpj4203-200.

23. Merlo LJ, Cummings SM, Cottler LB. Prescription drug diversion among substance-impaired pharmacists. Am J Addict. 2014;23(2):123-128. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2013.12078.x. PubMed

24. O’Malley L, Croucher K. Housing and dementia care-a scoping review of the literature. Health Soc Care Commun. 2005;13(6):570-577. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2005.00588.x. PubMed

25. Fischer B, Bibby M, Bouchard M. The global diversion of pharmaceutical drugs non-medical use and diversion of psychotropic prescription drugs in North America: a review of sourcing routes and control measures. Addiction. 2010;105(12):2062-2070. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03092.x. PubMed

26. Inciardi JA, Surratt HL, Cicero TJ, et al. The “black box” of prescription drug diversion. J Addict Dis. 2009;28(4):332-347. doi: 10.1080/10550880903182986. PubMed

27. Boulis S, Khanduja PK, Downey K, Friedman Z. Substance abuse: a national survey of Canadian residency program directors and site chiefs at university-affiliated anesthesia departments. Can J Anesth. 2015;62(9):964-971. doi: 10.1007/s12630-015-0404-1. PubMed

28. Warner DO, Berge K, Sun H et al. Substance use disorder among anesthesiology residents, 1975-2009. JAMA. 2013;310(21):2289-2296. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281954. PubMed

29. Kunyk D. Substance use disorders among registered nurses: prevalence, risks and perceptions in a disciplinary jurisdiction. J Nurs Manag. 2015;23(1):54-64. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12081. PubMed

30. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19-32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. PubMed

31. Brummond PW, Chen DF, Churchill WW, et al. ASHP guidelines on preventing diversion of controlled substances. Am J Health System Pharm. 2017;74(5):325-348. doi: 10.2146/ajhp160919. PubMed

32. New K. Diversion risk rounds: a reality check on your drug-handling policies. http://www.diversionspecialists.com/wp-content/uploads/Diversion-Risk-Rounds-A-Reality-Check-on-Your-Drug-Handling-Policies.pdf. Accessed July 13, 2017.

33. New K. Uncovering Diversion: 6 case studies on Diversion. https://www.pppmag.com/article/2162. Accessed January 30, 2018.

34. New KS. Undertaking a System Wide Diversion Risk Assessment [PowerPoint]. International Health Facility Diversion Association Conference; 2016. Accessed July 14, 2016.

35. O’Neal B, Siegel J. Diversion in the pharmacy. Hosp Pharm. 2007;42(2):145-148. doi: 10.1310/hpj4202-145.

36. Holleran RS. What is wrong With this picture? J Emerg Nurs. 2010;36(5):396-397. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2010.08.005. PubMed

37. Vrabel R. Identifying and dealing with drug diversion. How hospitals can stay one step ahead. https://www.hcinnovationgropu.com/home/article/13003330/identifying-and-dealing-with-drug-diversion. Accessed September 18, 2017.

38. Mentler P. Preventing diversion in the ED. https://www.pppmag.com/article/1778. Accessed July 19, 2017.

39. Fernandez J. Hospitals wage battle against drug diversion. https://www.drugtopics.com/top-news/hospitals-wage-battle-against-drug-diversion. Accessed August 17, 2017.

40. Minnesota Hospital Association. Road map to controlled substance diversion Prevention 2.0. https://www.mnhospitals.org/Portals/0/Documents/ptsafety/diversion/Road Map to Controlled Substance Diversion Prevention 2.0.pdf. Accessed June 30, 2017.

41. Bryson EO, Silverstein JH. Addiction and substance abuse in anesthesiology. Anesthesiology. 2008;109(5):905-917. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181895bc1. PubMed

42. McCammon C. Diversion: a quiet threat in the healthcare setting. https://www.acep.org/Content.aspx?ID=94932. Accessed August 17, 2017.

43. Minnesota Hospital Association. Identifying potentially impaired practitioners [PowerPoint]. https://www.mnhospitals.org/Portals/0/Documents/ptsafety/diversion/potentially-impaired-practitioners.pdf. Accessed July 21, 2017.

44. Burger G, Burger M. Drug diversion: new approaches to an old problem. Am J Pharm Benefits. 2016;8(1):30-33.

45. Greenall J, Santora P, Koczmara C, Hyland S. Enhancing safe medication use for pediatric patients in the emergency department. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2009;62(2):150-153. doi: 10.4212/cjhp.v62i2.445. PubMed

46. New K. Avoid diversion practices that prompt DEA investigations. https://www.pppmag.com/article/1818. Accessed October 4, 2017.

47. New K. Detecting and responding to drug diversion. https://rxdiversion.com/detecting-and-responding-to-drug-diversion. Accessed July 13, 2017.

48. New KS. Institutional Diversion Prevention, Detection and Response [PowerPoint]. https://www.ncsbn.org/0613_DISC_Kim_New.pdf. Accessed August 25, 2017.

49. Siegel J, Forrey RA. Four case studies on diversion prevention. https://www.pppmag.com/article/1469/March_2014/Four_Case_Studies_on_Diversion_Prevention. Accessed July 31, 2017.

50. Copp MAB. Drug addiction among nurses: confronting a quiet epidemic-Many RNs fall prey to this hidden, potentially deadly disease. http://www.modernmedicine.com/modern-medicine/news/modernmedicine/modern-medicine-feature-articles/drug-addiction-among-nurses-con. Accessed September 8, 2017.

51. Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Public health vulnerability review: drug diversion, infection risk, and David Kwiatkowski’s employment as a healthcare worker in Maryland. https://health.maryland.gov/pdf/Public Health Vulnerability Review.pdf. Accessed July 21, 2017.

52. Warner AE, Schaefer MK, Patel PR, et al. Outbreak of hepatitis C virus infection associated with narcotics diversion by an hepatitis C virus-infected surgical technician. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43(1):53-58. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.09.012. PubMed

53. New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services-Division of Public Health Services. Hepatitis C outbreak investigation Exeter Hospital public report. https://www.dhhs.nh.gov/dphs/cdcs/hepatitisc/documents/hepc-outbreak-rpt.pdf . Accessed July 21, 2017.

54. Paparella SF. A tale of waste and loss: lessons learned. J Emerg Nurs. 2016;42(4):352-354. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2016.03.025. PubMed

55. Ramer LM. Using servant leadership to facilitate healing after a drug diversion experience. AORN J. 2008;88(2):253-258. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2008.05.002. PubMed

56. Siegel J, O’Neal B, Code N. Prevention of controlled substance diversion-Code N: multidisciplinary approach to proactive drug diversion prevention. Hosp Pharm. 2007;42(3):244-248. doi: 10.1310/hpj4203-244.