User login

Specialty Hospitalists May Be Coming to Your Hospital Soon

Nearly 20 years ago, Bob Wachter, MD, coined the term “hospitalist,” defining a new specialty caring for the hospitalized medical patient. Since that time, we’ve seen rapid growth in the numbers of physicians who identify themselves as hospitalists, dominated by training in internal medicine and, to a lesser extent, family practice and pediatrics.

But, what about other specialty hospitalists, trained in the medicine or surgical specialties? How much of a presence do they have in our institutions today and in which specialties? To help us better understand this, a new question in 2014 State of Hospital Medicine survey asked whether specialty hospitalists practice in your hospital or health system.

—Carolyn Sites, DO, FHM

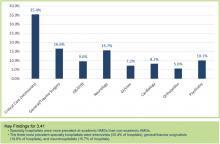

Results show the top three specialty hospitalists to be critical care, at (35.4%), followed by general surgery/trauma (16.6%) and neurology (15.7%), based on the responses of survey participants representing hospital medicine groups (HMGs) that care for adults only. Other specialties included obstetrics (OB), psychiatry, GI, cardiology, and orthopedics (see Figure 1).

Perhaps not too surprising, the greatest number of specialty hospitalists are found in university and academic settings. These are our primary training centers, offering fellowship programs and further subspecialization programs. Much like in our own field of hospital medicine, some academic centers have created one-year fellowships for those interested in specific hospital specialty fields, such as OB hospitalist.

For reasons that are less clear, the survey also shows percentages are highest in the western U.S. and lowest in the East.

Critical care hospitalists, also known as intensivists, dominate the spectrum, being present in academic and nonacademic centers, regardless of the employment model of the medical hospitalists at those facilities. This is not unexpected, given the Leapfrog Group’s endorsement of ICU physician staffing with intensivists.

What’s driving the other specialty hospitalist fields? I suspect the reasons are similar to those of our own specialty. OB and neuro hospitalists at my health system cite the challenges of managing outpatient and inpatient practices, the higher inpatient acuity and focused skill set that are required, immediate availability demands, and work-life balance as key factors. Further drivers include external quality/safety governing agencies or groups, such as the Leapfrog example above, or The Joint Commission’s requirements for certification as a Comprehensive Stroke Center with neurointensive care units.

Much like our own field’s exponential growth, we are likely to see further expansion of specialty hospitalists over the next several years. It will be interesting to watch how much and how fast this occurs, and what impact and influence these groups will bring to the care of the hospitalized patient. I’m already looking forward to next year’s SOHM report to see those results.

Dr. Sites is regional medical director of hospital medicine at Providence Health Systems in Oregon and a member of the SHM Practice Analysis Committee.

Nearly 20 years ago, Bob Wachter, MD, coined the term “hospitalist,” defining a new specialty caring for the hospitalized medical patient. Since that time, we’ve seen rapid growth in the numbers of physicians who identify themselves as hospitalists, dominated by training in internal medicine and, to a lesser extent, family practice and pediatrics.

But, what about other specialty hospitalists, trained in the medicine or surgical specialties? How much of a presence do they have in our institutions today and in which specialties? To help us better understand this, a new question in 2014 State of Hospital Medicine survey asked whether specialty hospitalists practice in your hospital or health system.

—Carolyn Sites, DO, FHM

Results show the top three specialty hospitalists to be critical care, at (35.4%), followed by general surgery/trauma (16.6%) and neurology (15.7%), based on the responses of survey participants representing hospital medicine groups (HMGs) that care for adults only. Other specialties included obstetrics (OB), psychiatry, GI, cardiology, and orthopedics (see Figure 1).

Perhaps not too surprising, the greatest number of specialty hospitalists are found in university and academic settings. These are our primary training centers, offering fellowship programs and further subspecialization programs. Much like in our own field of hospital medicine, some academic centers have created one-year fellowships for those interested in specific hospital specialty fields, such as OB hospitalist.

For reasons that are less clear, the survey also shows percentages are highest in the western U.S. and lowest in the East.

Critical care hospitalists, also known as intensivists, dominate the spectrum, being present in academic and nonacademic centers, regardless of the employment model of the medical hospitalists at those facilities. This is not unexpected, given the Leapfrog Group’s endorsement of ICU physician staffing with intensivists.

What’s driving the other specialty hospitalist fields? I suspect the reasons are similar to those of our own specialty. OB and neuro hospitalists at my health system cite the challenges of managing outpatient and inpatient practices, the higher inpatient acuity and focused skill set that are required, immediate availability demands, and work-life balance as key factors. Further drivers include external quality/safety governing agencies or groups, such as the Leapfrog example above, or The Joint Commission’s requirements for certification as a Comprehensive Stroke Center with neurointensive care units.

Much like our own field’s exponential growth, we are likely to see further expansion of specialty hospitalists over the next several years. It will be interesting to watch how much and how fast this occurs, and what impact and influence these groups will bring to the care of the hospitalized patient. I’m already looking forward to next year’s SOHM report to see those results.

Dr. Sites is regional medical director of hospital medicine at Providence Health Systems in Oregon and a member of the SHM Practice Analysis Committee.

Nearly 20 years ago, Bob Wachter, MD, coined the term “hospitalist,” defining a new specialty caring for the hospitalized medical patient. Since that time, we’ve seen rapid growth in the numbers of physicians who identify themselves as hospitalists, dominated by training in internal medicine and, to a lesser extent, family practice and pediatrics.

But, what about other specialty hospitalists, trained in the medicine or surgical specialties? How much of a presence do they have in our institutions today and in which specialties? To help us better understand this, a new question in 2014 State of Hospital Medicine survey asked whether specialty hospitalists practice in your hospital or health system.

—Carolyn Sites, DO, FHM

Results show the top three specialty hospitalists to be critical care, at (35.4%), followed by general surgery/trauma (16.6%) and neurology (15.7%), based on the responses of survey participants representing hospital medicine groups (HMGs) that care for adults only. Other specialties included obstetrics (OB), psychiatry, GI, cardiology, and orthopedics (see Figure 1).

Perhaps not too surprising, the greatest number of specialty hospitalists are found in university and academic settings. These are our primary training centers, offering fellowship programs and further subspecialization programs. Much like in our own field of hospital medicine, some academic centers have created one-year fellowships for those interested in specific hospital specialty fields, such as OB hospitalist.

For reasons that are less clear, the survey also shows percentages are highest in the western U.S. and lowest in the East.

Critical care hospitalists, also known as intensivists, dominate the spectrum, being present in academic and nonacademic centers, regardless of the employment model of the medical hospitalists at those facilities. This is not unexpected, given the Leapfrog Group’s endorsement of ICU physician staffing with intensivists.

What’s driving the other specialty hospitalist fields? I suspect the reasons are similar to those of our own specialty. OB and neuro hospitalists at my health system cite the challenges of managing outpatient and inpatient practices, the higher inpatient acuity and focused skill set that are required, immediate availability demands, and work-life balance as key factors. Further drivers include external quality/safety governing agencies or groups, such as the Leapfrog example above, or The Joint Commission’s requirements for certification as a Comprehensive Stroke Center with neurointensive care units.

Much like our own field’s exponential growth, we are likely to see further expansion of specialty hospitalists over the next several years. It will be interesting to watch how much and how fast this occurs, and what impact and influence these groups will bring to the care of the hospitalized patient. I’m already looking forward to next year’s SOHM report to see those results.

Dr. Sites is regional medical director of hospital medicine at Providence Health Systems in Oregon and a member of the SHM Practice Analysis Committee.

Hospitalist Compensation Models Evolve Toward Production, Performance-Based Variables

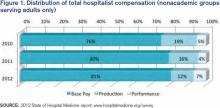

Hospitalists have long recognized that compensation varies significantly by geographic location and by the type of hospitalist medicine group (HMG) you work in: private vs. hospital-owned vs. national-management-owned. A review of SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report suggests that hospitalist compensation is also evolving toward a model that more routinely includes both some production variable and performance-based pay (see Figure 1). Although the proportion of compensation paid as a base salary has been trending up over the last few years, so has the proportion paid as a performance incentive.

Source: 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report; www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey

The pay distribution of adult-medicine hospitalists employed by management companies is composed of a high base percentage (mean 88.3% by survey data) and relatively low production and performance variables (mean 6.8% and 4.9%, respectively) compared with other employment models. Contrast that with private hospitalist-only groups, where the mean base is 76.3% with an emphasis on a production component (19.4%) and slightly less on performance pay at 4.2%.

Of the three employment models, however, hospital-/health-system-employed groups have the highest proportion of compensation based on performance metrics with a mean of 7.8%. This makes sense given the financial penalties hospitals and health systems are facing from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) around pay-for-performance measures. Hospitals are looking for help from hospitalists in improving quality of care and patient satisfaction and avoiding incurring future penalties. Compensation models in these groups reflect the goals of aligning performance on these measures with financial incentives/risk for hospitalists working in these environments.

What are the top performance metrics hospitalists are being compensated for? CMS’ hospital value-based purchasing (HVBP) core measures and patient satisfaction scores are at the top of the list. More than 70% of all HMGs identify these two measures as part of their performance pay incentive, which is seen consistently by geographic location and by type of hospitalist group.

Beyond these top two metrics, management-company-employed groups also focus on ED throughput measures and early morning discharge times, with more than 70% of these groups having pay incentives aligned with these goals. They also have a higher proportion of their groups participating in several other measures, such as clinical protocols, medication reconciliation, EHR utilization, transitions of care, and readmission rates. In comparison, both hospital-employed and private groups have a wider variety of performance measures in which they participate. Differences are seen geographically, too, with hospitalists located in the Western region having a wider variety of performance measures than other regions.

How hospitalists are compensated for their work will likely continue to evolve. Overall, for nonacademic HMGs serving adults only, we are seeing an upward trend in percentage paid as base pay (from 76% in 2010 to 81% in 2012) and in performance (from 5% in 2010 to 7% in 2012). Hospitalists should anticipate that performance-based pay will continue to account for an increasingly larger percentage of their overall compensation, especially as CMS’ pay-for-performance measures for hospital systems really start to take effect.

Hospital CEOs and CFOs are looking to hospitalists to help deliver on quality, satisfaction, and other performance measures. Incentives will be put in place to reward those groups who do it well.

Dr. Sites is senior medical director of hospitalist programs at Providence Health and Services in Oregon. She is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Hospitalists have long recognized that compensation varies significantly by geographic location and by the type of hospitalist medicine group (HMG) you work in: private vs. hospital-owned vs. national-management-owned. A review of SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report suggests that hospitalist compensation is also evolving toward a model that more routinely includes both some production variable and performance-based pay (see Figure 1). Although the proportion of compensation paid as a base salary has been trending up over the last few years, so has the proportion paid as a performance incentive.

Source: 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report; www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey

The pay distribution of adult-medicine hospitalists employed by management companies is composed of a high base percentage (mean 88.3% by survey data) and relatively low production and performance variables (mean 6.8% and 4.9%, respectively) compared with other employment models. Contrast that with private hospitalist-only groups, where the mean base is 76.3% with an emphasis on a production component (19.4%) and slightly less on performance pay at 4.2%.

Of the three employment models, however, hospital-/health-system-employed groups have the highest proportion of compensation based on performance metrics with a mean of 7.8%. This makes sense given the financial penalties hospitals and health systems are facing from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) around pay-for-performance measures. Hospitals are looking for help from hospitalists in improving quality of care and patient satisfaction and avoiding incurring future penalties. Compensation models in these groups reflect the goals of aligning performance on these measures with financial incentives/risk for hospitalists working in these environments.

What are the top performance metrics hospitalists are being compensated for? CMS’ hospital value-based purchasing (HVBP) core measures and patient satisfaction scores are at the top of the list. More than 70% of all HMGs identify these two measures as part of their performance pay incentive, which is seen consistently by geographic location and by type of hospitalist group.

Beyond these top two metrics, management-company-employed groups also focus on ED throughput measures and early morning discharge times, with more than 70% of these groups having pay incentives aligned with these goals. They also have a higher proportion of their groups participating in several other measures, such as clinical protocols, medication reconciliation, EHR utilization, transitions of care, and readmission rates. In comparison, both hospital-employed and private groups have a wider variety of performance measures in which they participate. Differences are seen geographically, too, with hospitalists located in the Western region having a wider variety of performance measures than other regions.

How hospitalists are compensated for their work will likely continue to evolve. Overall, for nonacademic HMGs serving adults only, we are seeing an upward trend in percentage paid as base pay (from 76% in 2010 to 81% in 2012) and in performance (from 5% in 2010 to 7% in 2012). Hospitalists should anticipate that performance-based pay will continue to account for an increasingly larger percentage of their overall compensation, especially as CMS’ pay-for-performance measures for hospital systems really start to take effect.

Hospital CEOs and CFOs are looking to hospitalists to help deliver on quality, satisfaction, and other performance measures. Incentives will be put in place to reward those groups who do it well.

Dr. Sites is senior medical director of hospitalist programs at Providence Health and Services in Oregon. She is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Hospitalists have long recognized that compensation varies significantly by geographic location and by the type of hospitalist medicine group (HMG) you work in: private vs. hospital-owned vs. national-management-owned. A review of SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report suggests that hospitalist compensation is also evolving toward a model that more routinely includes both some production variable and performance-based pay (see Figure 1). Although the proportion of compensation paid as a base salary has been trending up over the last few years, so has the proportion paid as a performance incentive.

Source: 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report; www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey

The pay distribution of adult-medicine hospitalists employed by management companies is composed of a high base percentage (mean 88.3% by survey data) and relatively low production and performance variables (mean 6.8% and 4.9%, respectively) compared with other employment models. Contrast that with private hospitalist-only groups, where the mean base is 76.3% with an emphasis on a production component (19.4%) and slightly less on performance pay at 4.2%.

Of the three employment models, however, hospital-/health-system-employed groups have the highest proportion of compensation based on performance metrics with a mean of 7.8%. This makes sense given the financial penalties hospitals and health systems are facing from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) around pay-for-performance measures. Hospitals are looking for help from hospitalists in improving quality of care and patient satisfaction and avoiding incurring future penalties. Compensation models in these groups reflect the goals of aligning performance on these measures with financial incentives/risk for hospitalists working in these environments.

What are the top performance metrics hospitalists are being compensated for? CMS’ hospital value-based purchasing (HVBP) core measures and patient satisfaction scores are at the top of the list. More than 70% of all HMGs identify these two measures as part of their performance pay incentive, which is seen consistently by geographic location and by type of hospitalist group.

Beyond these top two metrics, management-company-employed groups also focus on ED throughput measures and early morning discharge times, with more than 70% of these groups having pay incentives aligned with these goals. They also have a higher proportion of their groups participating in several other measures, such as clinical protocols, medication reconciliation, EHR utilization, transitions of care, and readmission rates. In comparison, both hospital-employed and private groups have a wider variety of performance measures in which they participate. Differences are seen geographically, too, with hospitalists located in the Western region having a wider variety of performance measures than other regions.

How hospitalists are compensated for their work will likely continue to evolve. Overall, for nonacademic HMGs serving adults only, we are seeing an upward trend in percentage paid as base pay (from 76% in 2010 to 81% in 2012) and in performance (from 5% in 2010 to 7% in 2012). Hospitalists should anticipate that performance-based pay will continue to account for an increasingly larger percentage of their overall compensation, especially as CMS’ pay-for-performance measures for hospital systems really start to take effect.

Hospital CEOs and CFOs are looking to hospitalists to help deliver on quality, satisfaction, and other performance measures. Incentives will be put in place to reward those groups who do it well.

Dr. Sites is senior medical director of hospitalist programs at Providence Health and Services in Oregon. She is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.