User login

In the Literature: Research You Need to Know

Clinical question: What is the relative efficacy of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/sulfa) versus ciprofloxacin for the treatment of severe exacerbations of COPD?

Background: The use of antimicrobials in the treatment of COPD exacerbations is well accepted, with the original studies using amoxicillin, TMP/sulfa, and tetracyclines. Whether newer antimicrobial agents offer greater efficacy versus these standard agents remains uncertain.

Study design: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled (double-dummy), noninferiority trial.

Setting: Two academic medical ICUs in Tunisia.

Synopsis: Consecutive patients (n=170) with severe exacerbations of COPD requiring mechanical ventilation were randomized to standard medical therapy plus either TMP/sulfa or ciprofloxacin. Patients had a prior diagnosis of COPD and the clinical presence of purulent sputum and respiratory failure. The study excluded those who were immunosuppressed, had significant hepatic or renal disease, pneumonia, recent antibiotic use, active cancer, or inability to take oral medications.

The primary endpoint of hospital death and the need for an additional course of antibiotics was no different between the groups (16.4% with TMP/sulfa versus 15.3% with ciprofloxacin). The mean exacerbation-free interval, days of mechanical ventilation, and length of stay were no different. Noninferiority was defined as <10% relative difference.

Bottom line: TMP/sulfa was noninferior to ciprofloxacin in the treatment of severe exacerbations of COPD requiring mechanical ventilation.

Citation: Nouira S, Marghli S, Besbes L, et al. Standard versus newer antibacterial agents in the treatment of severe acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized trial of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole versus ciprofloxacin. Clin Inf Dis. 2010;51:143-149.

For more physician reviews of HM-related research, visit our website.

Clinical question: What is the relative efficacy of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/sulfa) versus ciprofloxacin for the treatment of severe exacerbations of COPD?

Background: The use of antimicrobials in the treatment of COPD exacerbations is well accepted, with the original studies using amoxicillin, TMP/sulfa, and tetracyclines. Whether newer antimicrobial agents offer greater efficacy versus these standard agents remains uncertain.

Study design: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled (double-dummy), noninferiority trial.

Setting: Two academic medical ICUs in Tunisia.

Synopsis: Consecutive patients (n=170) with severe exacerbations of COPD requiring mechanical ventilation were randomized to standard medical therapy plus either TMP/sulfa or ciprofloxacin. Patients had a prior diagnosis of COPD and the clinical presence of purulent sputum and respiratory failure. The study excluded those who were immunosuppressed, had significant hepatic or renal disease, pneumonia, recent antibiotic use, active cancer, or inability to take oral medications.

The primary endpoint of hospital death and the need for an additional course of antibiotics was no different between the groups (16.4% with TMP/sulfa versus 15.3% with ciprofloxacin). The mean exacerbation-free interval, days of mechanical ventilation, and length of stay were no different. Noninferiority was defined as <10% relative difference.

Bottom line: TMP/sulfa was noninferior to ciprofloxacin in the treatment of severe exacerbations of COPD requiring mechanical ventilation.

Citation: Nouira S, Marghli S, Besbes L, et al. Standard versus newer antibacterial agents in the treatment of severe acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized trial of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole versus ciprofloxacin. Clin Inf Dis. 2010;51:143-149.

For more physician reviews of HM-related research, visit our website.

Clinical question: What is the relative efficacy of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/sulfa) versus ciprofloxacin for the treatment of severe exacerbations of COPD?

Background: The use of antimicrobials in the treatment of COPD exacerbations is well accepted, with the original studies using amoxicillin, TMP/sulfa, and tetracyclines. Whether newer antimicrobial agents offer greater efficacy versus these standard agents remains uncertain.

Study design: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled (double-dummy), noninferiority trial.

Setting: Two academic medical ICUs in Tunisia.

Synopsis: Consecutive patients (n=170) with severe exacerbations of COPD requiring mechanical ventilation were randomized to standard medical therapy plus either TMP/sulfa or ciprofloxacin. Patients had a prior diagnosis of COPD and the clinical presence of purulent sputum and respiratory failure. The study excluded those who were immunosuppressed, had significant hepatic or renal disease, pneumonia, recent antibiotic use, active cancer, or inability to take oral medications.

The primary endpoint of hospital death and the need for an additional course of antibiotics was no different between the groups (16.4% with TMP/sulfa versus 15.3% with ciprofloxacin). The mean exacerbation-free interval, days of mechanical ventilation, and length of stay were no different. Noninferiority was defined as <10% relative difference.

Bottom line: TMP/sulfa was noninferior to ciprofloxacin in the treatment of severe exacerbations of COPD requiring mechanical ventilation.

Citation: Nouira S, Marghli S, Besbes L, et al. Standard versus newer antibacterial agents in the treatment of severe acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized trial of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole versus ciprofloxacin. Clin Inf Dis. 2010;51:143-149.

For more physician reviews of HM-related research, visit our website.

In the Literature: HM-Related Research You Need to Know

In This Edition

Literature at a Glance

A guide to this month’s studies

- Characteristics of CA-MRSA

- Association of gurgling with morbidity and mortality

- Antibiotics for active ulcerative colitis

- TIPS for cirrhosis-induced variceal bleeding

- Steroid dose, route in COPD exacerbations

- Effect of reminders and stop orders on urinary catheter use

- Outcomes of chest-compression-only CPR

- Albumin levels and risk of surgical-site infections

Characteristics of Community-Acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus Pneumonia in an Academic Medical Center

Clinical question: What are the clinical features and epidemiology of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) pneumonia?

Background: CA-MRSA is an emerging cause of pneumonia. The genetic makeup of most CA-MRSA strains is different than that of nosocomial MRSA. Typically, CA-MRSA is resistant to methicillin, beta-lactams, and erythromycin, but it retains susceptibility to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP/sulfa) and clindamycin.

In addition, the most common strain of CA-MRSA carries the Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) toxin, which is associated with necrotizing pneumonia and high mortality rates.

Study design: Retrospective case series.

Setting: A 1,100-bed teaching hospital in Chicago.

Synopsis: Of the 5,955 discharges with a diagnosis-related group (DRG) code of pneumonia, 15 met criteria for CA-MRSA, or <1% of all inpatient community-acquired pneumonia cases. All 15 CA-MRSA strains were positive for PVL.

Seven of the 15 patients never were admitted to the ICU, while seven patients required mechanical ventilation. Seven patients were immunocompromised; one patient presented with preceding influenza; seven patients presented with hemoptysis; and eight patients demonstrated findings of lung necrosis on CT scan. Two patients died; both were immunocompromised.

Although the initial antibiotic regimen varied considerably, 14 patients ultimately received either clindamycin or linezolid.

Bottom line: CA-MRSA pneumonia is an uncommon subset of community-acquired pneumonia admissions. Approximately half the patients admitted with CA-MRSA presented with features of severe pneumonia. Nearly all were treated with antibiotics that inhibit exotoxin production, and the associated mortality rate of 13% was lower than previously reported.

Citation: Lobo JL, Reed KD, Wunderink RG. Expanded clinical presentation of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. Chest. 2010;138(1):130-136.

Gurgling Breath Sounds in Hospitalized Patients Might Predict Subsequent Pneumonia Development

Clinical question: Can gurgling sounds over the glottis during speech or quiet breathing predict hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP)?

Background: HAP is a relatively frequent complication of hospitalization. HAP usually portends an increase in morbidity and mortality. Patients in the hospital might have disease states that inhibit the reflexes that normally eliminate secretions from above or below their glottis, increasing the risk of pneumonia.

Study design: Prospective cohort.

Setting: A 350-bed community teaching hospital in Bridgeport, Conn.

Synopsis: All patients admitted to a respiratory-care unit and general medical ward from December 2008 to April 2009 underwent auscultation over their glottis by study personnel. Patients with gurgles heard during speech or quiet breathing on auscultation and patients without gurgles were entered into the study in a 1:3 fashion, until 20 patients with gurgles and 60 patients without gurgles had been enrolled. Patients were followed for the development of clinical and radiographic evidence of HAP, ICU transfer, and in-hospital death.

Both dementia and treatment with opiates were independent predictors of gurgle in multivariate analysis. HAP occurred in 55% of the patients with gurgle versus 1.7% of patients without gurgle. In addition, 50% of the patients with gurgle required transfer to the ICU, compared with only 3.3% of patients without gurgle. In-hospital mortality was 30% among patients with gurgle versus 11.7% among patients without gurgle.

Bottom line: In patients admitted to the medical service of a community teaching hospital, gurgling sounds heard over the glottis during speech or quiet inspiration are independently associated with the development of HAP, ICU transfer, and in-hospital mortality.

Citation: Vazquez R, Gheorghe C, Ramos F, Dadu R, Amoateng-Adjepong Y, Manthous CA. Gurgling breath sounds may predict hospital-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2010;138(2):284-288.

Treatment of Active Ulcerative Colitis with Triple Antibiotic Therapy Provides Better Response than Placebo

Clinical question: Does combination antibiotic therapy induce and/or maintain remission of active ulcerative colitis (UC)?

Background: Mouse models and other experimental evidence have suggested a pathogenic role for microbes in the development and/or exacerbation of ulcerative colitis, although antibiotic human trials have produced conflicting results. Recently, Fusobacterium varium was shown to be present in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract of most UC patients, and a pilot study using targeted antibacterials demonstrated efficacy in treating active UC.

Study design: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial.

Setting: Eleven hospitals in Japan.

Synopsis: Patients with mild to severe chronic relapsing UC were randomly assigned to either combination antibiotic therapy or placebo. All previous UC treatment regimens were continued in study patients, with the exception of steroids, which were tapered slowly if possible. Patients in the antibiotic group received a two-week combination therapy of amoxicillin, tetracycline, and metronidazole. Patients were followed weekly or monthly and underwent periodic exams and colonoscopies to assess clinical and endoscopic improvement for 12 months.

One hundred five patients were enrolled in each group. The clinical response rate at one year in patients treated with antibiotics was 44.8% versus 22.8% in the placebo group. Remission at one year was achieved in 26.7% of patients treated with antibiotics versus 14.9% of placebo patients. Endoscopic response rates and steroid discontinuation rates were higher in the antibiotic-treated groups. Effects were most pronounced in the group of patients with active disease.

Bottom line: Triple antibiotic therapy with amoxicillin, tetracycline, and metronidazole, when compared with placebo, was associated with improvement in clinical symptoms, endoscopic findings, remission rates, and steroid withdrawal in patients with active ulcerative colitis.

Citation: Ohkusa T, Kato K, Terao S, et al. Newly developed antibiotic combination therapy for ulcerative colitis: a double-blind placebo-controlled multicenter trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(8):1820-1829.

Early TIPS Outperformed Optimal Medical Therapy in Patients with Advanced Cirrhosis and Variceal Bleeding

Clinical question: Does early treatment with a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) improve outcomes in patients with advanced cirrhosis and variceal bleeding?

Background: Current management guidelines for variceal bleeding include treatment with vasoactive drugs and serial endoscopy, yet treatment failure occurs in 10% to 15% of patients. TIPS is highly effective in controlling bleeding in such patients, but it historically has been reserved for patients who repeatedly fail preventive strategies.

Study design: Randomized controlled trial.

Setting: Nine European centers.

Synopsis: Sixty-three patients with advanced cirrhosis and acute esophageal variceal bleeding treated with optimal medical therapy were randomized within 24 hours of admission to either 1) early TIPS (polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stents) within 72 hours of randomization, or 2) ongoing optimal medical therapy with vasoactive drugs, treatment with a nonselective beta-blocker, and endoscopic band ligation.

During the median 16-month follow-up, rebleeding or failure to control bleeding occurred in 45% of patients in the optimal medical therapy group versus 3% of patients in the early TIPS group. One-year actuarial survival was 61% in the optimal medical therapy group versus 86% in the early-TIPS group. Remarkably, encephalopathy was less common in the early-TIPS group, and adverse events as a whole were similar in both groups.

Bottom line: Early use of TIPS was superior to optimal medical therapy for patients with advanced cirrhosis hospitalized for acute variceal bleeding at high risk for treatment failure.

Citation: García-Pagán JC, Caca K, Bureau C, et al. Early use of TIPS in patients with cirrhosis and variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(25):2370-2379.

Low-Dose Oral Corticosteroids As Effective As High-Dose Intravenous Therapy in COPD Exacerbations

Clinical question: In patients hospitalized with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), what are the outcomes of those initially treated with low doses of steroids administered orally compared with those initially treated with higher doses intravenously?

Background: COPD affects 6% of adults in the U.S., and acute exacerbation of COPD is one of the leading causes of hospitalization nationwide. Systemic corticosteroids are beneficial for patients hospitalized with acute exacerbation of COPD; however, optimal dose and route of administration are uncertain.

Study design: Retrospective cohort.

Setting: Four hundred fourteen U.S. acute-care hospitals; most were small to midsize nonteaching facilities serving urban patient populations.

Synopsis: Almost 80,000 patients admitted to a non-ICU setting with a diagnosis of acute exacerbation of COPD from 2006 to 2007, and who received systemic corticosteroids during the first two hospital days, were included in the study. In contrast to clinical guidelines recommending the use of low-dose oral corticosteroids, 92% of study participants were treated initially with intravenous steroids, whereas 8% received oral treatment. The primary composite outcome measure—need for mechanical ventilation after the second hospital day, inpatient mortality, or readmission for COPD within 30 days—was no worse in patients treated with oral steroids. Risk of treatment failure, length of stay, and cost were significantly lower among orally treated patients.

Bottom line: High-dose intravenous steroids appear to be no more effective than low-dose oral steroids for acute exacerbation of COPD. The authors recommend a randomized controlled trial be conducted to compare these two management strategies.

Citation: Lindenauer PK, Pekow PS, Lahti MC, Lee Y, Benjamin EM, Rothberg MB. Association of corticosteroid dose and route of administration with risk of treatment failure in acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA. 2010;303(23):2359-2367.

Reminders and Stop Orders Reduce Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections

Clinical question: Do interventions that remind clinicians of the presence of urinary catheters and prompt timely removal decrease the rate of catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CA-UTI)?

Background: CA-UTI is a common yet preventable hospital-acquired infection. Many catheters are placed unnecessarily, remain in use without physician awareness, and are not removed promptly when no longer needed.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis of 13 preintervention and postintervention quasi-experimental trials and one randomized controlled trial.

Setting: Studies conducted in the U.S., Canada, Europe, and Asia.

Synopsis: This literature search revealed 14 articles that used a reminder or stop-order intervention to prompt removal of urinary catheters and reported pre- and postintervention outcomes for CA-UTI rates, duration of urinary catheter use, and recatheterization need. Five studies used stop orders and nine studies used reminder interventions.

Use of a stop order or reminder reduced the rate of CA-UTI (episodes per 1,000 catheter days) by 52%. Mean duration of catheterization decreased by 37%, which resulted in 2.61 fewer days of catheterization per patient in the intervention versus control groups. Recatheterization rates were similar in the control and intervention groups.

Bottom line: Urinary catheter reminders and stop orders are low-cost strategies that appear to reduce the rate of CA-UTI.

Citation: Meddings J, Rogers MA, Macy M, Saint S. Systematic review and meta-analysis: reminder systems to reduce catheter-associated urinary tract infections and urinary catheter use in hospitalized patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(5):550-560.

Chest-Compression-Only Bystander CPR Increases Survival

Clinical question: Is bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) with chest compressions alone or chest compressions with rescue breathing superior in out-of-hospital adult cardiac arrest?

Background: Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest claims hundreds of thousands of lives each year. Early initiation of CPR by a layperson can increase a patient’s chances of surviving and having a favorable long-term neurologic recovery. Although traditional CPR consists of chest compression with rescue breathing, chest compression alone might be more acceptable to many laypersons and has the potential advantage of fewer compression interruptions.

Study design: Multicenter randomized trial.

Setting: Two EMSs in Washington state and one in London.

Synopsis: Patients were initially eligible for this study if a dispatcher determined that the patient was unconscious and not breathing, and that bystander CPR was not yet under way. If the caller was willing to undertake CPR with the dispatcher’s assistance, a randomization envelope containing CPR instructions was opened. Patients with arrest due to trauma, drowning, or asphyxiation were excluded, as were those under 18 years of age.

No significant difference was observed between the two groups in the percentage of patients who survived to hospital discharge or who survived with a favorable neurologic outcome. However, subgroup analyses showed a trend toward a higher percentage of patients surviving to hospital discharge with chest compressions alone, as compared with chest compressions with rescue breathing for patients with a cardiac cause of arrest and for those with shockable rhythms.

Bottom line: Dispatcher CPR instruction consisting of chest compression alone was noninferior to conventional CPR with rescue breathing, and it showed a trend toward better outcomes in cardiac cause of arrest.

Citation: Rea TD, Fahrenbruch C, Culley L, et al. CPR with chest compression alone or with rescue breathing. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(5):423-433.

Low Albumin Is Associated with Postoperative Wound Infections

Clinical question: What is the relationship between preoperative serum albumin levels and postoperative surgical-site infections (SSI)?

Background: Poor nutritional status is associated with adverse surgical outcomes. Serum albumin can both reflect nutritional status and function as a negative acute phase reactant, i.e., decreases in the setting of inflammation. It is uncertain whether low preoperative albumin levels are associated with postoperative SSI risk.

Study design: Retrospective cohort with multivariate analysis.

Setting: Four centers in Ireland.

Synopsis: Patients undergoing GI surgery (n=524) were prospectively followed as part of an SSI database. Demographic data, American Society of Anesthesia class, serum albumin levels, and presence and severity of SSI data were collected on all patients. Follow-up extended to 30 days.

SSI developed in 20% of patients. Patients who developed a SSI had lower serum albumin levels (mean 3.0 g/dL versus 3.6 g/dL). A serum albumin level less than 3.0 g/dL was associated with greater risk of SSI (relative risk 5.68), deeper SSI, and prolonged length of stay.

Bottom line: After controlling for other variables, serum albumin lower than 3.0 g/dL is independently associated with SSI frequency and severity.

Citation: Hennessey DB, Burke JP, Ni-Dhonochu T, Shields C, Winter DC, Mealy K. Preoperative hypoalbuminemia is an independent risk factor for the development of surgical site infection following gastrointestinal surgery: a multi-institutional study. Ann Surg. 2010;252 (2):325-329. TH

In This Edition

Literature at a Glance

A guide to this month’s studies

- Characteristics of CA-MRSA

- Association of gurgling with morbidity and mortality

- Antibiotics for active ulcerative colitis

- TIPS for cirrhosis-induced variceal bleeding

- Steroid dose, route in COPD exacerbations

- Effect of reminders and stop orders on urinary catheter use

- Outcomes of chest-compression-only CPR

- Albumin levels and risk of surgical-site infections

Characteristics of Community-Acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus Pneumonia in an Academic Medical Center

Clinical question: What are the clinical features and epidemiology of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) pneumonia?

Background: CA-MRSA is an emerging cause of pneumonia. The genetic makeup of most CA-MRSA strains is different than that of nosocomial MRSA. Typically, CA-MRSA is resistant to methicillin, beta-lactams, and erythromycin, but it retains susceptibility to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP/sulfa) and clindamycin.

In addition, the most common strain of CA-MRSA carries the Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) toxin, which is associated with necrotizing pneumonia and high mortality rates.

Study design: Retrospective case series.

Setting: A 1,100-bed teaching hospital in Chicago.

Synopsis: Of the 5,955 discharges with a diagnosis-related group (DRG) code of pneumonia, 15 met criteria for CA-MRSA, or <1% of all inpatient community-acquired pneumonia cases. All 15 CA-MRSA strains were positive for PVL.

Seven of the 15 patients never were admitted to the ICU, while seven patients required mechanical ventilation. Seven patients were immunocompromised; one patient presented with preceding influenza; seven patients presented with hemoptysis; and eight patients demonstrated findings of lung necrosis on CT scan. Two patients died; both were immunocompromised.

Although the initial antibiotic regimen varied considerably, 14 patients ultimately received either clindamycin or linezolid.

Bottom line: CA-MRSA pneumonia is an uncommon subset of community-acquired pneumonia admissions. Approximately half the patients admitted with CA-MRSA presented with features of severe pneumonia. Nearly all were treated with antibiotics that inhibit exotoxin production, and the associated mortality rate of 13% was lower than previously reported.

Citation: Lobo JL, Reed KD, Wunderink RG. Expanded clinical presentation of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. Chest. 2010;138(1):130-136.

Gurgling Breath Sounds in Hospitalized Patients Might Predict Subsequent Pneumonia Development

Clinical question: Can gurgling sounds over the glottis during speech or quiet breathing predict hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP)?

Background: HAP is a relatively frequent complication of hospitalization. HAP usually portends an increase in morbidity and mortality. Patients in the hospital might have disease states that inhibit the reflexes that normally eliminate secretions from above or below their glottis, increasing the risk of pneumonia.

Study design: Prospective cohort.

Setting: A 350-bed community teaching hospital in Bridgeport, Conn.

Synopsis: All patients admitted to a respiratory-care unit and general medical ward from December 2008 to April 2009 underwent auscultation over their glottis by study personnel. Patients with gurgles heard during speech or quiet breathing on auscultation and patients without gurgles were entered into the study in a 1:3 fashion, until 20 patients with gurgles and 60 patients without gurgles had been enrolled. Patients were followed for the development of clinical and radiographic evidence of HAP, ICU transfer, and in-hospital death.

Both dementia and treatment with opiates were independent predictors of gurgle in multivariate analysis. HAP occurred in 55% of the patients with gurgle versus 1.7% of patients without gurgle. In addition, 50% of the patients with gurgle required transfer to the ICU, compared with only 3.3% of patients without gurgle. In-hospital mortality was 30% among patients with gurgle versus 11.7% among patients without gurgle.

Bottom line: In patients admitted to the medical service of a community teaching hospital, gurgling sounds heard over the glottis during speech or quiet inspiration are independently associated with the development of HAP, ICU transfer, and in-hospital mortality.

Citation: Vazquez R, Gheorghe C, Ramos F, Dadu R, Amoateng-Adjepong Y, Manthous CA. Gurgling breath sounds may predict hospital-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2010;138(2):284-288.

Treatment of Active Ulcerative Colitis with Triple Antibiotic Therapy Provides Better Response than Placebo

Clinical question: Does combination antibiotic therapy induce and/or maintain remission of active ulcerative colitis (UC)?

Background: Mouse models and other experimental evidence have suggested a pathogenic role for microbes in the development and/or exacerbation of ulcerative colitis, although antibiotic human trials have produced conflicting results. Recently, Fusobacterium varium was shown to be present in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract of most UC patients, and a pilot study using targeted antibacterials demonstrated efficacy in treating active UC.

Study design: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial.

Setting: Eleven hospitals in Japan.

Synopsis: Patients with mild to severe chronic relapsing UC were randomly assigned to either combination antibiotic therapy or placebo. All previous UC treatment regimens were continued in study patients, with the exception of steroids, which were tapered slowly if possible. Patients in the antibiotic group received a two-week combination therapy of amoxicillin, tetracycline, and metronidazole. Patients were followed weekly or monthly and underwent periodic exams and colonoscopies to assess clinical and endoscopic improvement for 12 months.

One hundred five patients were enrolled in each group. The clinical response rate at one year in patients treated with antibiotics was 44.8% versus 22.8% in the placebo group. Remission at one year was achieved in 26.7% of patients treated with antibiotics versus 14.9% of placebo patients. Endoscopic response rates and steroid discontinuation rates were higher in the antibiotic-treated groups. Effects were most pronounced in the group of patients with active disease.

Bottom line: Triple antibiotic therapy with amoxicillin, tetracycline, and metronidazole, when compared with placebo, was associated with improvement in clinical symptoms, endoscopic findings, remission rates, and steroid withdrawal in patients with active ulcerative colitis.

Citation: Ohkusa T, Kato K, Terao S, et al. Newly developed antibiotic combination therapy for ulcerative colitis: a double-blind placebo-controlled multicenter trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(8):1820-1829.

Early TIPS Outperformed Optimal Medical Therapy in Patients with Advanced Cirrhosis and Variceal Bleeding

Clinical question: Does early treatment with a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) improve outcomes in patients with advanced cirrhosis and variceal bleeding?

Background: Current management guidelines for variceal bleeding include treatment with vasoactive drugs and serial endoscopy, yet treatment failure occurs in 10% to 15% of patients. TIPS is highly effective in controlling bleeding in such patients, but it historically has been reserved for patients who repeatedly fail preventive strategies.

Study design: Randomized controlled trial.

Setting: Nine European centers.

Synopsis: Sixty-three patients with advanced cirrhosis and acute esophageal variceal bleeding treated with optimal medical therapy were randomized within 24 hours of admission to either 1) early TIPS (polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stents) within 72 hours of randomization, or 2) ongoing optimal medical therapy with vasoactive drugs, treatment with a nonselective beta-blocker, and endoscopic band ligation.

During the median 16-month follow-up, rebleeding or failure to control bleeding occurred in 45% of patients in the optimal medical therapy group versus 3% of patients in the early TIPS group. One-year actuarial survival was 61% in the optimal medical therapy group versus 86% in the early-TIPS group. Remarkably, encephalopathy was less common in the early-TIPS group, and adverse events as a whole were similar in both groups.

Bottom line: Early use of TIPS was superior to optimal medical therapy for patients with advanced cirrhosis hospitalized for acute variceal bleeding at high risk for treatment failure.

Citation: García-Pagán JC, Caca K, Bureau C, et al. Early use of TIPS in patients with cirrhosis and variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(25):2370-2379.

Low-Dose Oral Corticosteroids As Effective As High-Dose Intravenous Therapy in COPD Exacerbations

Clinical question: In patients hospitalized with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), what are the outcomes of those initially treated with low doses of steroids administered orally compared with those initially treated with higher doses intravenously?

Background: COPD affects 6% of adults in the U.S., and acute exacerbation of COPD is one of the leading causes of hospitalization nationwide. Systemic corticosteroids are beneficial for patients hospitalized with acute exacerbation of COPD; however, optimal dose and route of administration are uncertain.

Study design: Retrospective cohort.

Setting: Four hundred fourteen U.S. acute-care hospitals; most were small to midsize nonteaching facilities serving urban patient populations.

Synopsis: Almost 80,000 patients admitted to a non-ICU setting with a diagnosis of acute exacerbation of COPD from 2006 to 2007, and who received systemic corticosteroids during the first two hospital days, were included in the study. In contrast to clinical guidelines recommending the use of low-dose oral corticosteroids, 92% of study participants were treated initially with intravenous steroids, whereas 8% received oral treatment. The primary composite outcome measure—need for mechanical ventilation after the second hospital day, inpatient mortality, or readmission for COPD within 30 days—was no worse in patients treated with oral steroids. Risk of treatment failure, length of stay, and cost were significantly lower among orally treated patients.

Bottom line: High-dose intravenous steroids appear to be no more effective than low-dose oral steroids for acute exacerbation of COPD. The authors recommend a randomized controlled trial be conducted to compare these two management strategies.

Citation: Lindenauer PK, Pekow PS, Lahti MC, Lee Y, Benjamin EM, Rothberg MB. Association of corticosteroid dose and route of administration with risk of treatment failure in acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA. 2010;303(23):2359-2367.

Reminders and Stop Orders Reduce Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections

Clinical question: Do interventions that remind clinicians of the presence of urinary catheters and prompt timely removal decrease the rate of catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CA-UTI)?

Background: CA-UTI is a common yet preventable hospital-acquired infection. Many catheters are placed unnecessarily, remain in use without physician awareness, and are not removed promptly when no longer needed.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis of 13 preintervention and postintervention quasi-experimental trials and one randomized controlled trial.

Setting: Studies conducted in the U.S., Canada, Europe, and Asia.

Synopsis: This literature search revealed 14 articles that used a reminder or stop-order intervention to prompt removal of urinary catheters and reported pre- and postintervention outcomes for CA-UTI rates, duration of urinary catheter use, and recatheterization need. Five studies used stop orders and nine studies used reminder interventions.

Use of a stop order or reminder reduced the rate of CA-UTI (episodes per 1,000 catheter days) by 52%. Mean duration of catheterization decreased by 37%, which resulted in 2.61 fewer days of catheterization per patient in the intervention versus control groups. Recatheterization rates were similar in the control and intervention groups.

Bottom line: Urinary catheter reminders and stop orders are low-cost strategies that appear to reduce the rate of CA-UTI.

Citation: Meddings J, Rogers MA, Macy M, Saint S. Systematic review and meta-analysis: reminder systems to reduce catheter-associated urinary tract infections and urinary catheter use in hospitalized patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(5):550-560.

Chest-Compression-Only Bystander CPR Increases Survival

Clinical question: Is bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) with chest compressions alone or chest compressions with rescue breathing superior in out-of-hospital adult cardiac arrest?

Background: Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest claims hundreds of thousands of lives each year. Early initiation of CPR by a layperson can increase a patient’s chances of surviving and having a favorable long-term neurologic recovery. Although traditional CPR consists of chest compression with rescue breathing, chest compression alone might be more acceptable to many laypersons and has the potential advantage of fewer compression interruptions.

Study design: Multicenter randomized trial.

Setting: Two EMSs in Washington state and one in London.

Synopsis: Patients were initially eligible for this study if a dispatcher determined that the patient was unconscious and not breathing, and that bystander CPR was not yet under way. If the caller was willing to undertake CPR with the dispatcher’s assistance, a randomization envelope containing CPR instructions was opened. Patients with arrest due to trauma, drowning, or asphyxiation were excluded, as were those under 18 years of age.

No significant difference was observed between the two groups in the percentage of patients who survived to hospital discharge or who survived with a favorable neurologic outcome. However, subgroup analyses showed a trend toward a higher percentage of patients surviving to hospital discharge with chest compressions alone, as compared with chest compressions with rescue breathing for patients with a cardiac cause of arrest and for those with shockable rhythms.

Bottom line: Dispatcher CPR instruction consisting of chest compression alone was noninferior to conventional CPR with rescue breathing, and it showed a trend toward better outcomes in cardiac cause of arrest.

Citation: Rea TD, Fahrenbruch C, Culley L, et al. CPR with chest compression alone or with rescue breathing. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(5):423-433.

Low Albumin Is Associated with Postoperative Wound Infections

Clinical question: What is the relationship between preoperative serum albumin levels and postoperative surgical-site infections (SSI)?

Background: Poor nutritional status is associated with adverse surgical outcomes. Serum albumin can both reflect nutritional status and function as a negative acute phase reactant, i.e., decreases in the setting of inflammation. It is uncertain whether low preoperative albumin levels are associated with postoperative SSI risk.

Study design: Retrospective cohort with multivariate analysis.

Setting: Four centers in Ireland.

Synopsis: Patients undergoing GI surgery (n=524) were prospectively followed as part of an SSI database. Demographic data, American Society of Anesthesia class, serum albumin levels, and presence and severity of SSI data were collected on all patients. Follow-up extended to 30 days.

SSI developed in 20% of patients. Patients who developed a SSI had lower serum albumin levels (mean 3.0 g/dL versus 3.6 g/dL). A serum albumin level less than 3.0 g/dL was associated with greater risk of SSI (relative risk 5.68), deeper SSI, and prolonged length of stay.

Bottom line: After controlling for other variables, serum albumin lower than 3.0 g/dL is independently associated with SSI frequency and severity.

Citation: Hennessey DB, Burke JP, Ni-Dhonochu T, Shields C, Winter DC, Mealy K. Preoperative hypoalbuminemia is an independent risk factor for the development of surgical site infection following gastrointestinal surgery: a multi-institutional study. Ann Surg. 2010;252 (2):325-329. TH

In This Edition

Literature at a Glance

A guide to this month’s studies

- Characteristics of CA-MRSA

- Association of gurgling with morbidity and mortality

- Antibiotics for active ulcerative colitis

- TIPS for cirrhosis-induced variceal bleeding

- Steroid dose, route in COPD exacerbations

- Effect of reminders and stop orders on urinary catheter use

- Outcomes of chest-compression-only CPR

- Albumin levels and risk of surgical-site infections

Characteristics of Community-Acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus Pneumonia in an Academic Medical Center

Clinical question: What are the clinical features and epidemiology of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) pneumonia?

Background: CA-MRSA is an emerging cause of pneumonia. The genetic makeup of most CA-MRSA strains is different than that of nosocomial MRSA. Typically, CA-MRSA is resistant to methicillin, beta-lactams, and erythromycin, but it retains susceptibility to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP/sulfa) and clindamycin.

In addition, the most common strain of CA-MRSA carries the Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) toxin, which is associated with necrotizing pneumonia and high mortality rates.

Study design: Retrospective case series.

Setting: A 1,100-bed teaching hospital in Chicago.

Synopsis: Of the 5,955 discharges with a diagnosis-related group (DRG) code of pneumonia, 15 met criteria for CA-MRSA, or <1% of all inpatient community-acquired pneumonia cases. All 15 CA-MRSA strains were positive for PVL.

Seven of the 15 patients never were admitted to the ICU, while seven patients required mechanical ventilation. Seven patients were immunocompromised; one patient presented with preceding influenza; seven patients presented with hemoptysis; and eight patients demonstrated findings of lung necrosis on CT scan. Two patients died; both were immunocompromised.

Although the initial antibiotic regimen varied considerably, 14 patients ultimately received either clindamycin or linezolid.

Bottom line: CA-MRSA pneumonia is an uncommon subset of community-acquired pneumonia admissions. Approximately half the patients admitted with CA-MRSA presented with features of severe pneumonia. Nearly all were treated with antibiotics that inhibit exotoxin production, and the associated mortality rate of 13% was lower than previously reported.

Citation: Lobo JL, Reed KD, Wunderink RG. Expanded clinical presentation of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. Chest. 2010;138(1):130-136.

Gurgling Breath Sounds in Hospitalized Patients Might Predict Subsequent Pneumonia Development

Clinical question: Can gurgling sounds over the glottis during speech or quiet breathing predict hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP)?

Background: HAP is a relatively frequent complication of hospitalization. HAP usually portends an increase in morbidity and mortality. Patients in the hospital might have disease states that inhibit the reflexes that normally eliminate secretions from above or below their glottis, increasing the risk of pneumonia.

Study design: Prospective cohort.

Setting: A 350-bed community teaching hospital in Bridgeport, Conn.

Synopsis: All patients admitted to a respiratory-care unit and general medical ward from December 2008 to April 2009 underwent auscultation over their glottis by study personnel. Patients with gurgles heard during speech or quiet breathing on auscultation and patients without gurgles were entered into the study in a 1:3 fashion, until 20 patients with gurgles and 60 patients without gurgles had been enrolled. Patients were followed for the development of clinical and radiographic evidence of HAP, ICU transfer, and in-hospital death.

Both dementia and treatment with opiates were independent predictors of gurgle in multivariate analysis. HAP occurred in 55% of the patients with gurgle versus 1.7% of patients without gurgle. In addition, 50% of the patients with gurgle required transfer to the ICU, compared with only 3.3% of patients without gurgle. In-hospital mortality was 30% among patients with gurgle versus 11.7% among patients without gurgle.

Bottom line: In patients admitted to the medical service of a community teaching hospital, gurgling sounds heard over the glottis during speech or quiet inspiration are independently associated with the development of HAP, ICU transfer, and in-hospital mortality.

Citation: Vazquez R, Gheorghe C, Ramos F, Dadu R, Amoateng-Adjepong Y, Manthous CA. Gurgling breath sounds may predict hospital-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2010;138(2):284-288.

Treatment of Active Ulcerative Colitis with Triple Antibiotic Therapy Provides Better Response than Placebo

Clinical question: Does combination antibiotic therapy induce and/or maintain remission of active ulcerative colitis (UC)?

Background: Mouse models and other experimental evidence have suggested a pathogenic role for microbes in the development and/or exacerbation of ulcerative colitis, although antibiotic human trials have produced conflicting results. Recently, Fusobacterium varium was shown to be present in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract of most UC patients, and a pilot study using targeted antibacterials demonstrated efficacy in treating active UC.

Study design: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial.

Setting: Eleven hospitals in Japan.

Synopsis: Patients with mild to severe chronic relapsing UC were randomly assigned to either combination antibiotic therapy or placebo. All previous UC treatment regimens were continued in study patients, with the exception of steroids, which were tapered slowly if possible. Patients in the antibiotic group received a two-week combination therapy of amoxicillin, tetracycline, and metronidazole. Patients were followed weekly or monthly and underwent periodic exams and colonoscopies to assess clinical and endoscopic improvement for 12 months.

One hundred five patients were enrolled in each group. The clinical response rate at one year in patients treated with antibiotics was 44.8% versus 22.8% in the placebo group. Remission at one year was achieved in 26.7% of patients treated with antibiotics versus 14.9% of placebo patients. Endoscopic response rates and steroid discontinuation rates were higher in the antibiotic-treated groups. Effects were most pronounced in the group of patients with active disease.

Bottom line: Triple antibiotic therapy with amoxicillin, tetracycline, and metronidazole, when compared with placebo, was associated with improvement in clinical symptoms, endoscopic findings, remission rates, and steroid withdrawal in patients with active ulcerative colitis.

Citation: Ohkusa T, Kato K, Terao S, et al. Newly developed antibiotic combination therapy for ulcerative colitis: a double-blind placebo-controlled multicenter trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(8):1820-1829.

Early TIPS Outperformed Optimal Medical Therapy in Patients with Advanced Cirrhosis and Variceal Bleeding

Clinical question: Does early treatment with a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) improve outcomes in patients with advanced cirrhosis and variceal bleeding?

Background: Current management guidelines for variceal bleeding include treatment with vasoactive drugs and serial endoscopy, yet treatment failure occurs in 10% to 15% of patients. TIPS is highly effective in controlling bleeding in such patients, but it historically has been reserved for patients who repeatedly fail preventive strategies.

Study design: Randomized controlled trial.

Setting: Nine European centers.

Synopsis: Sixty-three patients with advanced cirrhosis and acute esophageal variceal bleeding treated with optimal medical therapy were randomized within 24 hours of admission to either 1) early TIPS (polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stents) within 72 hours of randomization, or 2) ongoing optimal medical therapy with vasoactive drugs, treatment with a nonselective beta-blocker, and endoscopic band ligation.

During the median 16-month follow-up, rebleeding or failure to control bleeding occurred in 45% of patients in the optimal medical therapy group versus 3% of patients in the early TIPS group. One-year actuarial survival was 61% in the optimal medical therapy group versus 86% in the early-TIPS group. Remarkably, encephalopathy was less common in the early-TIPS group, and adverse events as a whole were similar in both groups.

Bottom line: Early use of TIPS was superior to optimal medical therapy for patients with advanced cirrhosis hospitalized for acute variceal bleeding at high risk for treatment failure.

Citation: García-Pagán JC, Caca K, Bureau C, et al. Early use of TIPS in patients with cirrhosis and variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(25):2370-2379.

Low-Dose Oral Corticosteroids As Effective As High-Dose Intravenous Therapy in COPD Exacerbations

Clinical question: In patients hospitalized with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), what are the outcomes of those initially treated with low doses of steroids administered orally compared with those initially treated with higher doses intravenously?

Background: COPD affects 6% of adults in the U.S., and acute exacerbation of COPD is one of the leading causes of hospitalization nationwide. Systemic corticosteroids are beneficial for patients hospitalized with acute exacerbation of COPD; however, optimal dose and route of administration are uncertain.

Study design: Retrospective cohort.

Setting: Four hundred fourteen U.S. acute-care hospitals; most were small to midsize nonteaching facilities serving urban patient populations.

Synopsis: Almost 80,000 patients admitted to a non-ICU setting with a diagnosis of acute exacerbation of COPD from 2006 to 2007, and who received systemic corticosteroids during the first two hospital days, were included in the study. In contrast to clinical guidelines recommending the use of low-dose oral corticosteroids, 92% of study participants were treated initially with intravenous steroids, whereas 8% received oral treatment. The primary composite outcome measure—need for mechanical ventilation after the second hospital day, inpatient mortality, or readmission for COPD within 30 days—was no worse in patients treated with oral steroids. Risk of treatment failure, length of stay, and cost were significantly lower among orally treated patients.

Bottom line: High-dose intravenous steroids appear to be no more effective than low-dose oral steroids for acute exacerbation of COPD. The authors recommend a randomized controlled trial be conducted to compare these two management strategies.

Citation: Lindenauer PK, Pekow PS, Lahti MC, Lee Y, Benjamin EM, Rothberg MB. Association of corticosteroid dose and route of administration with risk of treatment failure in acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA. 2010;303(23):2359-2367.

Reminders and Stop Orders Reduce Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections

Clinical question: Do interventions that remind clinicians of the presence of urinary catheters and prompt timely removal decrease the rate of catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CA-UTI)?

Background: CA-UTI is a common yet preventable hospital-acquired infection. Many catheters are placed unnecessarily, remain in use without physician awareness, and are not removed promptly when no longer needed.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis of 13 preintervention and postintervention quasi-experimental trials and one randomized controlled trial.

Setting: Studies conducted in the U.S., Canada, Europe, and Asia.

Synopsis: This literature search revealed 14 articles that used a reminder or stop-order intervention to prompt removal of urinary catheters and reported pre- and postintervention outcomes for CA-UTI rates, duration of urinary catheter use, and recatheterization need. Five studies used stop orders and nine studies used reminder interventions.

Use of a stop order or reminder reduced the rate of CA-UTI (episodes per 1,000 catheter days) by 52%. Mean duration of catheterization decreased by 37%, which resulted in 2.61 fewer days of catheterization per patient in the intervention versus control groups. Recatheterization rates were similar in the control and intervention groups.

Bottom line: Urinary catheter reminders and stop orders are low-cost strategies that appear to reduce the rate of CA-UTI.

Citation: Meddings J, Rogers MA, Macy M, Saint S. Systematic review and meta-analysis: reminder systems to reduce catheter-associated urinary tract infections and urinary catheter use in hospitalized patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(5):550-560.

Chest-Compression-Only Bystander CPR Increases Survival

Clinical question: Is bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) with chest compressions alone or chest compressions with rescue breathing superior in out-of-hospital adult cardiac arrest?

Background: Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest claims hundreds of thousands of lives each year. Early initiation of CPR by a layperson can increase a patient’s chances of surviving and having a favorable long-term neurologic recovery. Although traditional CPR consists of chest compression with rescue breathing, chest compression alone might be more acceptable to many laypersons and has the potential advantage of fewer compression interruptions.

Study design: Multicenter randomized trial.

Setting: Two EMSs in Washington state and one in London.

Synopsis: Patients were initially eligible for this study if a dispatcher determined that the patient was unconscious and not breathing, and that bystander CPR was not yet under way. If the caller was willing to undertake CPR with the dispatcher’s assistance, a randomization envelope containing CPR instructions was opened. Patients with arrest due to trauma, drowning, or asphyxiation were excluded, as were those under 18 years of age.

No significant difference was observed between the two groups in the percentage of patients who survived to hospital discharge or who survived with a favorable neurologic outcome. However, subgroup analyses showed a trend toward a higher percentage of patients surviving to hospital discharge with chest compressions alone, as compared with chest compressions with rescue breathing for patients with a cardiac cause of arrest and for those with shockable rhythms.

Bottom line: Dispatcher CPR instruction consisting of chest compression alone was noninferior to conventional CPR with rescue breathing, and it showed a trend toward better outcomes in cardiac cause of arrest.

Citation: Rea TD, Fahrenbruch C, Culley L, et al. CPR with chest compression alone or with rescue breathing. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(5):423-433.

Low Albumin Is Associated with Postoperative Wound Infections

Clinical question: What is the relationship between preoperative serum albumin levels and postoperative surgical-site infections (SSI)?

Background: Poor nutritional status is associated with adverse surgical outcomes. Serum albumin can both reflect nutritional status and function as a negative acute phase reactant, i.e., decreases in the setting of inflammation. It is uncertain whether low preoperative albumin levels are associated with postoperative SSI risk.

Study design: Retrospective cohort with multivariate analysis.

Setting: Four centers in Ireland.

Synopsis: Patients undergoing GI surgery (n=524) were prospectively followed as part of an SSI database. Demographic data, American Society of Anesthesia class, serum albumin levels, and presence and severity of SSI data were collected on all patients. Follow-up extended to 30 days.

SSI developed in 20% of patients. Patients who developed a SSI had lower serum albumin levels (mean 3.0 g/dL versus 3.6 g/dL). A serum albumin level less than 3.0 g/dL was associated with greater risk of SSI (relative risk 5.68), deeper SSI, and prolonged length of stay.

Bottom line: After controlling for other variables, serum albumin lower than 3.0 g/dL is independently associated with SSI frequency and severity.

Citation: Hennessey DB, Burke JP, Ni-Dhonochu T, Shields C, Winter DC, Mealy K. Preoperative hypoalbuminemia is an independent risk factor for the development of surgical site infection following gastrointestinal surgery: a multi-institutional study. Ann Surg. 2010;252 (2):325-329. TH

How Should Hospitalized Patients with Long QT Syndrome Be Managed?

Case

You are asked to admit a 63-year-old male with a history of hypertension and osteoarthritis. The patient, who fell at home, is scheduled for open repair of his femoral neck fracture the following day. The patient reports tripping over his granddaughter’s toys and denies any associated symptoms around the time of his fall. An electrocardiogram (ECG) reveals a QTc (QT) interval of 480 ms. How should this hospitalized patient’s prolonged QT interval be managed?

Overview

Patients with a prolonged QT interval on routine ECG present an interesting dilemma for clinicians. Although QT prolongation—either congenital or acquired—has been associated with dysrhythmias, the risk of torsades de pointes and sudden cardiac death varies considerably based on myriad underlying factors.1 Therefore, the principle job of the clinician who has recognized QT prolongation is to assess and minimize the risk of the development of clinically significant dysrhythmias, and to be prepared to manage them should they arise.

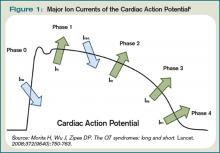

The QT interval encompasses ventricular depolarization and repolarization. This ventricular action potential proceeds through five phases. The initial upstroke (phase 0) of depolarization occurs with the opening of Na+ channels, triggering the inward Na+ current (INa), and causes the interior of the myocytes to become positively charged. This is followed by initial repolarization (phase 1) when the opening of K+ channels causes an outward K+ current (Ito). Next, the plateau phase (phase 2) of the action potential follows with a balance of inward current through Ca2+channels (Ica-L) and outward current through slow rectifier K+ channels (IKs), and then later through delayed, rapid K+ rectifier channels (IKr). Then, the inward current is deactivated, while the outward current increases through the rapid delayed rectifier (IKr) and opening of inward rectifier channels (IK1) to complete repolarization (phase 3). Finally, the action potential returns to baseline (phase 4) and Na+ begins to enter the cell again (see Figure 1, above).

The long QT syndrome (LQTS) is defined by a defect in these cardiac ion channels, which leads to abnormal repolarization, usually lengthening the QT interval and thus predisposing to ventricular dysrhythmias.2 It is estimated that as many as 85% of these syndromes are inherited, and up to 15% are acquired or sporadic.3 Depending on the underlying etiology of the LQTS, manifestations might first be appreciated at any time from in utero through adulthood.4 Symptoms including palpitations, syncope, seizures, or cardiac arrest bring these patients to medical attention.3 These symptoms frequently elicit physical or emotional stress, but they can occur without obvious inciting triggers.5 A 20% mortality risk exists in patients who are symptomatic and untreated in the first year following diagnosis, and up to 50% within 10 years following diagnosis.4

How is Long QT Syndrome Diagnosed?

The LQTS diagnosis is based on clinical history in combination with ECG abnormalities.6 Important historical elements include symptoms of palpitations, syncope, seizures, or cardiac arrest.3 In addition, a family history of unexplained syncope or sudden death, especially at a young age, should raise LQTS suspicion.5

A variety of ECG findings can be witnessed in LQTS patients.4,5 Although the majority of patients have a QTc >440 ms, approximately one-third have a QTc ≤460 ms, and about 10% have normal QTc intervals.5 Other ECG abnormalities include notched, biphasic, or prolonged T-waves, and the presence of U-waves.4,5 Schwartz et al used these elements to publish criteria (see Table 1, right) that physicians can use to assess the probability that a patient has LQTS.7

Types of Long QT Syndromes

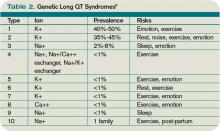

Because the risk of developing significant dysrhythmias with LQTS is dependent on both the actual QT interval, with risk for sudden cardiac death increased two to three times with QT >440 ms compared with QT <440 ms and the specific underlying genotype, it is important to have an understanding of congenital and acquired LQTS and the associated triggers for torsades de pointes.

Congenital LQTS

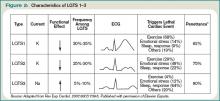

Congenital LQTS is caused by mutations in cardiac ion channel proteins, primarily sodium, and potassium channels.5,6 These defects either slow depolarization or lengthen repolarization, leading to heterogeneity of repolarization of the membrane.5 This, in turn, predisposes to ventricular dysrhythmias, including torsades de pointes and subsequent ventricular fibrillation and death.2 Currently, 12 genetic defects have been identified in LQTS. Hundreds of mutations have been described to cause these defects (see Table 2, right).8 Approximately 70% of congenital LQTS are caused by mutations in three genes and are classified as LQTS 1, LQTS 2, and LQTS 3.8 The other seven mutation types account for about 5% of cases; a quarter of LQTS cases have no identified genetic mutations.8

LQTS usually can be distinguished by clinical features and some ECG characteristics, but diagnosis of the specific type requires genetic testing.8,9 The most common types of LQTS are discussed below.

- Long QT1 is the most common type, occurring in approximately 40% to 50% of patients diagnosed with LQTS. It is characterized by a defect in the potassium channel alpha subunit leading to IKs reduction.9 These patients typically present with syncope or adrenergic-induced torsades, might have wide, broad-based T-waves on ECG, and respond well to beta-blocker therapy.6 Triggers for these patients include physical exertion or emotional stressors, particularly exercise and swimming. These patients typically present in early childhood.1

- Long QT2 occurs in 35% to 40% of patients and is characterized by a different defect in the alpha subunit of the potassium channel, which leads to reduced IKr.9 ECGs in LQTS2 can demonstrate low-amplitude and notched T-waves. Sudden catecholamine surges related to emotional stress or loud noises and bradycardia can trigger dysrhythmias in Long QT2.6 Thus, beta blockers reduce overall cardiac events in LQTS2 but less effectively than in LQTS1.6 These patients also present in childhood but typically are older than patients with LQTS1.6

- Long QT3 is less common than LQTS1 or LQTS2, at 2% to 8% of LQTS patients, but carries a higher mortality and is not treated effectively with beta blockers. LQTS3 is characterized by a defect in a sodium channel, causing a gain-of-function in the INa.4,9 These patients are more likely to have a fatal dysrhythmia while sleeping, are less susceptible to exercise-induced events, and have increased morbidity and mortality associated with bradycardia.4,9 ECG frequently reveals a relatively long ST segment, followed by a peaked and tall T-wave. Beta-blocker therapy can predispose to dysrhythmias in these patients; therefore, many of these patients will have pacemakers implanted as first-line therapy.6

While less common, Jervell and Lange Nielson syndrome is an autosomal recessive form of LQTS in which affected patients have homozygous mutations in the KCNQ1 or KCNE1 genes. This syndrome occurs in approximately 1% to 7% of LQTS patients, displays a typical QTc >550 ms, can be triggered by exercise and emotional stress, is associated with deafness, and carries a high risk of cardiac events at a young age.6

Acquired Syndromes

In addition to congenital LQTS, certain patients can acquire LQTS after being treated with particular drugs or having metabolic abnormalities, namely hypomagnesemia, hypocalcemia, and hypokalemia. Most experts think patients who “acquire” LQTS that predisposes to torsades de pointes have underlying structural heart disease or LQTS genetic carrier mutations that combine with transient initiating events (e.g., drugs or metabolic abnormalities) to induce dysrhythmias.1 In addition to certain drugs, cardiac ischemia, and electrolyte abnormalities, cocaine abuse, HIV, and subarachnoid hemorrhage can induce dysrhythmias in susceptible patients.5

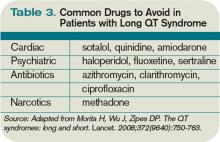

Many types of drugs can cause a prolonged QT interval, and others should be avoided in patients with pre-existing prolonged QT (see Table 3, p. 17). Potentially offending drugs that are frequently encountered by inpatient physicians include amiodarone, diltiazem, erythromycin, clarithromycin, ciprofloxacin, fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, haloperidol, ritonavir, and methadone.1 Additionally, drugs that cause electrolyte abnormalities (e.g., diuretics and lithium) should be monitored closely.

Overall, the goals of therapy in LQTS are:

- Decrease the risk of dysrhythmic events;

- Minimize adrenergic response;

- Shorten the QTc;

- Decrease the dispersion of refractoriness; and

- Improve the function of the ion channels.3

Supportive measures should be taken for patients who are acutely symptomatic from LQTS and associated torsades de pointes. In addition to immediate cardioversion for ongoing and hemodynamically significant torsades, intravenous magnesium should be administered, electrolytes corrected, and offending drugs discontinued.5 Temporary transvenous pacing at rates of approximately 100 beats per minute is highly effective in preventing short-term recurrence of torsades in congenital and acquired LQTS, especially in bradycardic patients.5 Isoproterenol infusion increases the heart rate and effectively prevents acute recurrence of torsades in patients with acquired LQTS, but it should be used with caution in patients with structural heart disease.5

Long-term strategies to manage LQTS include:

- Minimizing the risk of triggering cardiac events via adrenergic stimulation;

- Preventing ongoing dysrhythmias;

- Avoiding medications known to prolong the QT interval; and

- Maintaining normal electrolytes and minerals.5

Most patients with congenital long QT should be discouraged from participating in competitive sports, and patients should attempt to eliminate exposures to stress or sudden awakening, though this is not practical in all cases.5 Beta blockers generally are the first-line therapy and are more effective for LQT1 than LQT2 or LQT3.4,5 If patients are still symptomatic despite adequate medical therapy, or have survived cardiac arrest, they should be considered for ICD therapy.4,5 In addition, patients with profound bradycardia benefit from pacemaker implantation.5 Patients who remain symptomatic despite both beta blockade and ICD placement might find cervicothoracic sympathectomy curative.4,5

Perioperative Considerations

Although little data is available to guide physicians in the prevention of torsades de pointes during the course of anesthesia, there are a number of considerations that may reduce the chances of symptomatic dysrhythmias.

First, care should be taken to avoid dysrhythmia triggers in LQTS by providing a calm, quiet environment during induction, monitoring, and treating metabolic abnormalities, and providing an appropriate level of anesthesia.10 Beta-blocker therapy should be continued and potentially measured preoperatively by assessing heart rate response during stress testing.5 An implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (AICD) should be interrogated prior to surgery and inactivated during the operation.5

Finally, Kies et al have recommended general anesthesia with propofol for induction (or throughout), isoflurane as the volatile agent, vecuronium for muscle relaxation, and intravenous fentanyl for analgesia when possible.10

Back to the Case

While the patient had no genetic testing for LQTS, evaluation of previous ECGs demonstrated a prolonged QT interval. The hip fracture repair was considered an urgent procedure, which precluded the ability to undertake genetic testing and consideration for device implantation. The only medication that was known to increase the risk for dysrhythmias in this patient was his diuretic, with the attendant risk of electrolyte abnormalities.

Thus, the patient’s hydrochlorothiazide was discontinued and his pre-existing atenolol continued. The patient’s electrolytes and minerals were monitored closely, and magnesium was administered on the day of surgery. Anesthesia was made aware of the prolonged QT interval, such that they were able to minimize the risk for and anticipate the treatment of dysrhythmias. The patient tolerated the surgery and post-operative period without complication and was scheduled for an outpatient workup and management for his prolonged QT interval.

Bottom Line

Long QT syndrome is frequently genetic in origin, but it can be caused by certain medications and perturbations of electrolytes. Beta blockers are the first-line therapy for the majority of LQTS cases, along with discontinuation of drugs that might induce or aggravate the QT prolongation.

Patients who have had cardiac arrest or who remain symptomatic despite beta-blocker therapy should have an ICD implanted.

In the perioperative period, patients’ electrolytes should be monitored and kept within normal limits. If the patient is on a beta blocker, it should be continued, and the anesthesiologist should be made aware of the diagnosis so that the anesthethic plan can be optimized to prevent arrhythmic complications. TH

Dr. Kamali is a medical resident at the University of Colorado Denver. Dr. Stickrath is a hospitalist at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Denver and an instructor of medicine at UC Denver. Dr. Prochazka is director of ambulatory care at the Denver VA and professor of medicine at UC Denver. Dr. Varosy is director of cardiac electrophysiology at the Denver VA and assistant professor of medicine at UC Denver.

References

- Kao LW, Furbee BR. Drug-induced q-T prolongation. Med Clin North Am. 2005;89(6):1125-1144.

- Marchlinski F. Chapter 226, The Tachyarrhythmias; Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 17e. Available at: www.accessmedicine.com/resourceTOC .aspx?resourceID=4. Accessed Nov. 21, 2009.

- Zareba W, Cygankiewicz I. Long QT syndrome and short QT syndrome. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2008; 51(3):264-278.

- Booker PD, Whyte SD, Ladusans EJ. Long QT syndrome and anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2003;90(3):349-366.

- Khan IA. Long QT syndrome: diagnosis and management. Am Heart J. 2002;143(1):7-14.

- Morita H, Wu J, Zipes DP. The QT syndromes: long and short. Lancet. 2008;372(9640):750-763.

- Schwartz PJ, Moss AJ, Vincent GM, Crampton RS. Diagnostic criteria for the long QT syndrome. An update. Circulation. 1993;88(2):782-784.

- Kapa S, Tester DJ, Salisbury BA, et al. Genetic testing for long-QT syndrome: distinguishing pathogenic mutations from benign variants. Circulation. 2009;120(18):1752-1760.

- Modell SM, Lehmann MH. The long QT syndrome family of cardiac ion channelopathies: a HuGE review. Genet Med. 2006;8(3):143-155.

- Kies SJ, Pabelick CM, Hurley HA, White RD, Ackerman MJ. Anesthesia for patients with congenital long QT syndrome. Anesthesiology. 2005;102(1):204-210.

- Wisely NA, Shipton EA. Long QT syndrome and anaesthesia. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2002;19(12):853-859.

Case

You are asked to admit a 63-year-old male with a history of hypertension and osteoarthritis. The patient, who fell at home, is scheduled for open repair of his femoral neck fracture the following day. The patient reports tripping over his granddaughter’s toys and denies any associated symptoms around the time of his fall. An electrocardiogram (ECG) reveals a QTc (QT) interval of 480 ms. How should this hospitalized patient’s prolonged QT interval be managed?

Overview

Patients with a prolonged QT interval on routine ECG present an interesting dilemma for clinicians. Although QT prolongation—either congenital or acquired—has been associated with dysrhythmias, the risk of torsades de pointes and sudden cardiac death varies considerably based on myriad underlying factors.1 Therefore, the principle job of the clinician who has recognized QT prolongation is to assess and minimize the risk of the development of clinically significant dysrhythmias, and to be prepared to manage them should they arise.

The QT interval encompasses ventricular depolarization and repolarization. This ventricular action potential proceeds through five phases. The initial upstroke (phase 0) of depolarization occurs with the opening of Na+ channels, triggering the inward Na+ current (INa), and causes the interior of the myocytes to become positively charged. This is followed by initial repolarization (phase 1) when the opening of K+ channels causes an outward K+ current (Ito). Next, the plateau phase (phase 2) of the action potential follows with a balance of inward current through Ca2+channels (Ica-L) and outward current through slow rectifier K+ channels (IKs), and then later through delayed, rapid K+ rectifier channels (IKr). Then, the inward current is deactivated, while the outward current increases through the rapid delayed rectifier (IKr) and opening of inward rectifier channels (IK1) to complete repolarization (phase 3). Finally, the action potential returns to baseline (phase 4) and Na+ begins to enter the cell again (see Figure 1, above).

The long QT syndrome (LQTS) is defined by a defect in these cardiac ion channels, which leads to abnormal repolarization, usually lengthening the QT interval and thus predisposing to ventricular dysrhythmias.2 It is estimated that as many as 85% of these syndromes are inherited, and up to 15% are acquired or sporadic.3 Depending on the underlying etiology of the LQTS, manifestations might first be appreciated at any time from in utero through adulthood.4 Symptoms including palpitations, syncope, seizures, or cardiac arrest bring these patients to medical attention.3 These symptoms frequently elicit physical or emotional stress, but they can occur without obvious inciting triggers.5 A 20% mortality risk exists in patients who are symptomatic and untreated in the first year following diagnosis, and up to 50% within 10 years following diagnosis.4

How is Long QT Syndrome Diagnosed?

The LQTS diagnosis is based on clinical history in combination with ECG abnormalities.6 Important historical elements include symptoms of palpitations, syncope, seizures, or cardiac arrest.3 In addition, a family history of unexplained syncope or sudden death, especially at a young age, should raise LQTS suspicion.5

A variety of ECG findings can be witnessed in LQTS patients.4,5 Although the majority of patients have a QTc >440 ms, approximately one-third have a QTc ≤460 ms, and about 10% have normal QTc intervals.5 Other ECG abnormalities include notched, biphasic, or prolonged T-waves, and the presence of U-waves.4,5 Schwartz et al used these elements to publish criteria (see Table 1, right) that physicians can use to assess the probability that a patient has LQTS.7

Types of Long QT Syndromes

Because the risk of developing significant dysrhythmias with LQTS is dependent on both the actual QT interval, with risk for sudden cardiac death increased two to three times with QT >440 ms compared with QT <440 ms and the specific underlying genotype, it is important to have an understanding of congenital and acquired LQTS and the associated triggers for torsades de pointes.

Congenital LQTS

Congenital LQTS is caused by mutations in cardiac ion channel proteins, primarily sodium, and potassium channels.5,6 These defects either slow depolarization or lengthen repolarization, leading to heterogeneity of repolarization of the membrane.5 This, in turn, predisposes to ventricular dysrhythmias, including torsades de pointes and subsequent ventricular fibrillation and death.2 Currently, 12 genetic defects have been identified in LQTS. Hundreds of mutations have been described to cause these defects (see Table 2, right).8 Approximately 70% of congenital LQTS are caused by mutations in three genes and are classified as LQTS 1, LQTS 2, and LQTS 3.8 The other seven mutation types account for about 5% of cases; a quarter of LQTS cases have no identified genetic mutations.8

LQTS usually can be distinguished by clinical features and some ECG characteristics, but diagnosis of the specific type requires genetic testing.8,9 The most common types of LQTS are discussed below.

- Long QT1 is the most common type, occurring in approximately 40% to 50% of patients diagnosed with LQTS. It is characterized by a defect in the potassium channel alpha subunit leading to IKs reduction.9 These patients typically present with syncope or adrenergic-induced torsades, might have wide, broad-based T-waves on ECG, and respond well to beta-blocker therapy.6 Triggers for these patients include physical exertion or emotional stressors, particularly exercise and swimming. These patients typically present in early childhood.1

- Long QT2 occurs in 35% to 40% of patients and is characterized by a different defect in the alpha subunit of the potassium channel, which leads to reduced IKr.9 ECGs in LQTS2 can demonstrate low-amplitude and notched T-waves. Sudden catecholamine surges related to emotional stress or loud noises and bradycardia can trigger dysrhythmias in Long QT2.6 Thus, beta blockers reduce overall cardiac events in LQTS2 but less effectively than in LQTS1.6 These patients also present in childhood but typically are older than patients with LQTS1.6

- Long QT3 is less common than LQTS1 or LQTS2, at 2% to 8% of LQTS patients, but carries a higher mortality and is not treated effectively with beta blockers. LQTS3 is characterized by a defect in a sodium channel, causing a gain-of-function in the INa.4,9 These patients are more likely to have a fatal dysrhythmia while sleeping, are less susceptible to exercise-induced events, and have increased morbidity and mortality associated with bradycardia.4,9 ECG frequently reveals a relatively long ST segment, followed by a peaked and tall T-wave. Beta-blocker therapy can predispose to dysrhythmias in these patients; therefore, many of these patients will have pacemakers implanted as first-line therapy.6

While less common, Jervell and Lange Nielson syndrome is an autosomal recessive form of LQTS in which affected patients have homozygous mutations in the KCNQ1 or KCNE1 genes. This syndrome occurs in approximately 1% to 7% of LQTS patients, displays a typical QTc >550 ms, can be triggered by exercise and emotional stress, is associated with deafness, and carries a high risk of cardiac events at a young age.6

Acquired Syndromes

In addition to congenital LQTS, certain patients can acquire LQTS after being treated with particular drugs or having metabolic abnormalities, namely hypomagnesemia, hypocalcemia, and hypokalemia. Most experts think patients who “acquire” LQTS that predisposes to torsades de pointes have underlying structural heart disease or LQTS genetic carrier mutations that combine with transient initiating events (e.g., drugs or metabolic abnormalities) to induce dysrhythmias.1 In addition to certain drugs, cardiac ischemia, and electrolyte abnormalities, cocaine abuse, HIV, and subarachnoid hemorrhage can induce dysrhythmias in susceptible patients.5