User login

Things We Do For No Reason: Echocardiogram in Unselected Patients with Syncope

The “Things We Do for No Reason” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but which may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

Syncope is a common cause of emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalizations. Echocardiogram is frequently used as a diagnostic tool in the evaluation of syncope, performed in 39%-91% of patients.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A 57-year-old woman presented to the ED after a syncopal episode. She had just eaten dinner when she slumped over and became unresponsive. Her husband estimated that she regained consciousness 30 seconds later and quickly returned to baseline mental status. She denied chest pain, shortness of breath, or palpitations. Her medical history included hypertension and hypothyroidism. Her medication regimen was unchanged.

Vital signs, including orthostatic blood pressures, were within normal ranges. A physical examination revealed regular heart sounds without murmur, rub, or gallop. ECG showed normal sinus rhythm, normal axis, and normal intervals. Chest radiograph, complete blood count, chemistry, pro-brain natriuretic peptide (pro-BNP), and troponin were within normal ranges.

BACKGROUND

Syncope, defined as “abrupt, transient, complete loss of consciousness, associated with inability to maintain postural tone, with rapid and spontaneous recovery,”1 is a common clinical problem, accounting for 1% of ED visits in the United States.2 As syncope has been shown to be associated with increased mortality,3 the primary goal of syncope evaluation is to identify modifiable underlying causes, particularly cardiac causes. Current guidelines recommend a complete history and physical, orthostatic blood pressure measurement, and ECG as the initial evaluation for syncope.1 Echocardiogram is a frequent additional test, performed in 39%-91% of patients.4-8

WHY YOU MAY THINK ECHOCARDIOGRAM IS HELPFUL

Echocardiogram may identify depressed ejection fraction, a risk factor for ventricular arrhythmias, along with structural causes of syncope, including aortic stenosis, pulmonary hypertension, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.9 Structural heart disease is the underlying etiology in about 3% of patients with syncope.10

Prior guidelines stated that “an echocardiogram is a helpful screening test if the history, physical examination, and ECG do not provide a diagnosis or if underlying heart disease is suspected.”11 A separate guideline for the appropriate use of echocardiogram assigned a score of appropriateness on a 1-9 scale based on increasing indication.12 Echocardiogram for syncope was scored a 7 in patients with “no other symptoms or signs of cardiovascular disease.”12 Only 25%-40% of patients with syncope will have a cause identified after the history, physical examination, and ECG,13,14 creating diagnostic uncertainty that often leads to further testing.

WHY ECHOCARDIOGRAM IS NOT NECESSARY IN ALL PATIENTS

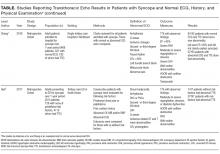

Mendu et al.5 performed a single-center, retrospective study of the diagnostic yield of testing for syncope in 2106 consecutive patients older than 65 admitted over the course of 5 years. They retrospectively applied the San Francisco Syncope Rule (SFSR), which patients met if they had congestive heart failure, hematocrit <30%, abnormal ECG, shortness of breath, or systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg. There were 821 patients (39%) who underwent echocardiogram. Among the 488 with no SFSR criteria, 10 patients (2%) had echocardiogram results that affected management, and 4 patients (1%) had results that helped determine the etiology of syncope.

Anderson et al. studied 323 syncope patients in a single ED observation unit over 18 months.6 Patients with high-risk features, including unstable vital signs, abnormal cardiac biomarkers, or ischemic ECG changes, were excluded from the unit. The initial ECG was considered abnormal if it contained arrhythmia, premature atrial or ventricular contractions, pacing, second- or third-degree heart block, or left bundle branch block. Of the 235 patients with a normal ECG who underwent echocardiogram, none had an abnormal study.

Chang et al.7 performed a retrospective review of 468 patients admitted with syncope at a single hospital. Charts were reviewed for ECG and echocardiogram results. Abnormal ECGs were defined as those containing arrhythmias, Q waves, ischemic changes, second- and third-degree heart block, paced rhythm, corrected QT interval (QTc) >500 ms, left bundle branch or bifasicular block, Brugada pattern, or abnormal axis. Among 321 patients with normal ECGs, echocardiograms were performed in 192. Eleven of those echocardiograms were abnormal: 3 demonstrated aortic stenosis in patients who already carried the diagnosis, and the other 8 abnormal echocardiograms revealed unexpected left ventricular ejection fractions <45% or other nonaortic valvular pathology. None of the findings were felt to be the cause of syncope.

Han et al.8 performed a retrospective cohort study of all syncope patients presenting to a single ED over the course of 1 year. Patients were stratified as high risk if they had chest pain, palpitations, a history of cardiac disease (defined as prior arrhythmia, heart failure, coronary artery disease, or structural heart disease), abnormal cardiac biomarkers, or an abnormal ECG (defined as sinus bradycardia, arrhythmia, premature beats, second- or third-degree heart block, ventricular hypertrophy, ischemic Q or ST changes, or abnormal QT interval). Patients with none of those symptoms or findings were considered low risk. Of those categorized as low risk (n = 115), 47 underwent echocardiogram, only 1 of which was abnormal.

Across studies, the percentage of patients with a normal cardiac history, examination, and ECG with new, significant abnormalities on echocardiogram was 0% in 3 studies (n = 340),4,6,15 2% in 1 study (10/488 patients),5 2.1% in 1 study (1/47 patients),8 and 4.2% in 1 study (8/192 patients).7 The 11 echocardiograms with significant findings in the studies by Mendu et al.5 and Han et al.8 were not further described. The 8 patients with abnormal echocardiograms reported by Chang et al.7 had depressed left ventricular ejection fraction or nonaortic valvular disease that did not represent a definitive etiology of their syncope. Given the cost of $1,000 to $2,220 per study,16 routine echocardiograms in patients with a normal history, examination, and ECG would thus require $60,000 to $132,000 in spending to find 1 new significant abnormality, which may be unrelated to the actual cause of syncope.

SITUATIONS IN WHICH ECHOCARDIOGRAM MAY BE HELPFUL

The diagnostic yield of echocardiogram is higher in patients with a positive cardiac history or abnormal ECG. In the prospective study by Sarasin et al.15 a total of 27% of patients with a positive cardiac history or abnormal ECG were found to have an ejection fraction less than or equal to 40%. Other studies reporting percentages of abnormal echocardiograms in patients with abnormal history, ECG, or examination found rates of 8% (26/333),5 20% (7/35),6 28% (27/97),8 and 29% (27/93).7 It should be noted that not all of these abnormalities were felt to be the cause of syncope. For example, Sarasin et al.15 reported that only half of the patients with newly identified depressed ejection fraction were diagnosed with arrhythmia-related syncope. Chang et al7 reported that 6 of the 27 patients (22%) with abnormal ECG and echocardiogram had the cause of syncope established by echocardiogram.

Finally, some syncope patients will have cardiac biomarkers sent in the ED. Han et al.8 found that among patients with syncope, those with abnormal versus normal echocardiogram were more likely to have elevated BNP (70% vs 23%) and troponin (36% vs 12.4%). Thus, obtaining an echocardiogram in patients with syncope and abnormal cardiac biomarkers may be reasonable. It should be noted, however, that while some studies have suggested a role for biomarkers in differentiating cardiac from noncardiac syncope,17-20 current guidelines state that the usefulness of these tests is uncertain.1

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD OF ECHOCARDIOGRAM FOR ALL PATIENTS

Clinicians should carefully screen patients with syncope for abnormal findings suggesting cardiac disease on history, physical examination, and ECG. Relevant cardiac history includes known coronary artery disease, valvular heart disease, arrhythmia, congestive heart failure, and risk factors for cardiac syncope (supplemental Appendix). The definition of abnormal ECG varies among studies, but abnormalities that should prompt an echocardiogram include arrhythmia, premature atrial or ventricular contractions, second- or third-degree heart block, sinus bradycardia, bundle branch or fascicular blocks, left ventricular hypertrophy, ischemic ST or T wave changes, Q waves, or a prolonged QTc interval. New guidelines from the American College of Cardiology state, “Routine cardiac imaging is not useful in the evaluation of patients with syncope unless cardiac etiology is suspected on the basis of an initial evaluation, including history, physical examination, or ECG.”1

RECOMMENDATIONS

- All patients with syncope should receive a complete history, physical examination, orthostatic vital signs, and ECG.

- Perform echocardiogram on patients with syncope and a history of cardiac disease, examination suggestive of structural heart disease or congestive heart failure, or abnormal ECG.

- Echocardiogram may be reasonable in patients with syncope and abnormal cardiac biomarkers.

CONCLUSIONS

While commonly performed as part of syncope evaluations, echocardiogram has a very low diagnostic yield in patients with a normal history, physical, and ECG. The patient described in the initial case scenario would have an extremely low likelihood of having important diagnostic information found on echocardiogram.

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

1. Shen WK, Sheldon RS, Benditt DG, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Patients With Syncope: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines, and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(5):620-633. PubMed

2. Sun BC, Emond JA, Camargo CA Jr. Characteristics and admission patterns of patients presenting with syncope to U.S. emergency departments, 1992-2000. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11(10):1029-1034. PubMed

3. Soteriades ES, Evans JC, Larson MG, et al. Incidence and prognosis of syncope. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(12):878-885. PubMed

4. Recchia D, Barzilai B. Echocardiography in the evaluation of patients with syncope. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10(12):649-655. PubMed

5. Mendu ML, McAvay G, Lampert R, Stoehr J, Tinetti ME. Yield of diagnostic tests in evaluating syncopal episodes in older patients. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(14):1299-1305. PubMed

6. Anderson KL, Limkakeng A, Damuth E, Chandra A. Cardiac evaluation for structural abnormalities may not be required in patients presenting with syncope and a normal ECG result in an observation unit setting. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(4):478-484.e1. PubMed

7. Chang NL, Shah P, Bajaj S, Virk H, Bikkina M, Shamoon F. Diagnostic Yield of Echocardiography in Syncope Patients with Normal ECG. Cardiol Res Pract. 2016;2016:1251637. PubMed

8. Han SK, Yeom SR, Lee SH, et al. Transthoracic echocardiogram in syncope patients with normal initial evaluation. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35(2):281-284. PubMed

9. Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Syncope, European Society of Cardiology, European Heart Rhythm Association, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009). Eur Heart J. 2009;30(21):2631-2671.

10. Alboni P, Brignole M, Menozzi C, et al. Diagnostic value of history in patients with syncope with or without heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37(7):1921-1928. PubMed

11. Strickberger SA, Benson DW, Biaggioni I, et al. AHA/ACCF Scientific Statement on the evaluation of syncope: from the American Heart Association Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Cardiovascular Nursing, Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and Stroke, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group; and the American College of Cardiology Foundation: in collaboration with the Heart Rhythm Society: endorsed by the American Autonomic Society. Circulation. 2006;113(2):316-327. PubMed

12. American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Society of Echocardiography, American Heart Association, et al. ACCF/ASE/AHA/ASNC/HFSA/HRS/SCAI/SCCM/SCCT/SCMR 2011 Appropriate Use Criteria for Echocardiography. A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Society of Echocardiography, American Heart Association, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Critical Care Medicine, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, and Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Endorsed by the American College of Chest Physicians. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(9):1126-1166. PubMed

13. Crane SD. Risk stratification of patients with syncope in an accident and emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2002;19(1):23-27. PubMed

14. Croci F, Brignole M, Alboni P, et al. The application of a standardized strategy of evaluation in patients with syncope referred to three syncope units. Europace. 2002;4(4):351-355. PubMed

15. Sarasin FP, Junod AF, Carballo D, Slama S, Unger PF, Louis-Simonet M. Role of echocardiography in the evaluation of syncope: a prospective study. Heart. 2002;88(4):363-367. PubMed

16. Echocardiogram Cost. http://health.costhelper.com/echocardiograms.html. 2017. Accessed January 26, 2017.

17. Thiruganasambandamoorthy V, Ramaekers R, Rahman MO, et al. Prognostic value of cardiac biomarkers in the risk stratification of syncope: a systematic review. Intern Emerg Med. 2015;10(8):1003-1014. PubMed

18. Pfister R, Diedrichs H, Larbig R, Erdmann E, Schneider CA. NT-pro-BNP for differential diagnosis in patients with syncope. Int J Cardiol. 2009;133(1):51-54. PubMed

19. Reed MJ, Mills NL, Weir CJ. Sensitive troponin assay predicts outcome in syncope. Emerg Med J. 2012;29(12):1001-1003. PubMed

20. Tanimoto K, Yukiiri K, Mizushige K, et al. Usefulness of brain natriuretic peptide as a marker for separating cardiac and noncardiac causes of syncope. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93(2):228-230. PubMed

The “Things We Do for No Reason” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but which may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

Syncope is a common cause of emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalizations. Echocardiogram is frequently used as a diagnostic tool in the evaluation of syncope, performed in 39%-91% of patients.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A 57-year-old woman presented to the ED after a syncopal episode. She had just eaten dinner when she slumped over and became unresponsive. Her husband estimated that she regained consciousness 30 seconds later and quickly returned to baseline mental status. She denied chest pain, shortness of breath, or palpitations. Her medical history included hypertension and hypothyroidism. Her medication regimen was unchanged.

Vital signs, including orthostatic blood pressures, were within normal ranges. A physical examination revealed regular heart sounds without murmur, rub, or gallop. ECG showed normal sinus rhythm, normal axis, and normal intervals. Chest radiograph, complete blood count, chemistry, pro-brain natriuretic peptide (pro-BNP), and troponin were within normal ranges.

BACKGROUND

Syncope, defined as “abrupt, transient, complete loss of consciousness, associated with inability to maintain postural tone, with rapid and spontaneous recovery,”1 is a common clinical problem, accounting for 1% of ED visits in the United States.2 As syncope has been shown to be associated with increased mortality,3 the primary goal of syncope evaluation is to identify modifiable underlying causes, particularly cardiac causes. Current guidelines recommend a complete history and physical, orthostatic blood pressure measurement, and ECG as the initial evaluation for syncope.1 Echocardiogram is a frequent additional test, performed in 39%-91% of patients.4-8

WHY YOU MAY THINK ECHOCARDIOGRAM IS HELPFUL

Echocardiogram may identify depressed ejection fraction, a risk factor for ventricular arrhythmias, along with structural causes of syncope, including aortic stenosis, pulmonary hypertension, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.9 Structural heart disease is the underlying etiology in about 3% of patients with syncope.10

Prior guidelines stated that “an echocardiogram is a helpful screening test if the history, physical examination, and ECG do not provide a diagnosis or if underlying heart disease is suspected.”11 A separate guideline for the appropriate use of echocardiogram assigned a score of appropriateness on a 1-9 scale based on increasing indication.12 Echocardiogram for syncope was scored a 7 in patients with “no other symptoms or signs of cardiovascular disease.”12 Only 25%-40% of patients with syncope will have a cause identified after the history, physical examination, and ECG,13,14 creating diagnostic uncertainty that often leads to further testing.

WHY ECHOCARDIOGRAM IS NOT NECESSARY IN ALL PATIENTS

Mendu et al.5 performed a single-center, retrospective study of the diagnostic yield of testing for syncope in 2106 consecutive patients older than 65 admitted over the course of 5 years. They retrospectively applied the San Francisco Syncope Rule (SFSR), which patients met if they had congestive heart failure, hematocrit <30%, abnormal ECG, shortness of breath, or systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg. There were 821 patients (39%) who underwent echocardiogram. Among the 488 with no SFSR criteria, 10 patients (2%) had echocardiogram results that affected management, and 4 patients (1%) had results that helped determine the etiology of syncope.

Anderson et al. studied 323 syncope patients in a single ED observation unit over 18 months.6 Patients with high-risk features, including unstable vital signs, abnormal cardiac biomarkers, or ischemic ECG changes, were excluded from the unit. The initial ECG was considered abnormal if it contained arrhythmia, premature atrial or ventricular contractions, pacing, second- or third-degree heart block, or left bundle branch block. Of the 235 patients with a normal ECG who underwent echocardiogram, none had an abnormal study.

Chang et al.7 performed a retrospective review of 468 patients admitted with syncope at a single hospital. Charts were reviewed for ECG and echocardiogram results. Abnormal ECGs were defined as those containing arrhythmias, Q waves, ischemic changes, second- and third-degree heart block, paced rhythm, corrected QT interval (QTc) >500 ms, left bundle branch or bifasicular block, Brugada pattern, or abnormal axis. Among 321 patients with normal ECGs, echocardiograms were performed in 192. Eleven of those echocardiograms were abnormal: 3 demonstrated aortic stenosis in patients who already carried the diagnosis, and the other 8 abnormal echocardiograms revealed unexpected left ventricular ejection fractions <45% or other nonaortic valvular pathology. None of the findings were felt to be the cause of syncope.

Han et al.8 performed a retrospective cohort study of all syncope patients presenting to a single ED over the course of 1 year. Patients were stratified as high risk if they had chest pain, palpitations, a history of cardiac disease (defined as prior arrhythmia, heart failure, coronary artery disease, or structural heart disease), abnormal cardiac biomarkers, or an abnormal ECG (defined as sinus bradycardia, arrhythmia, premature beats, second- or third-degree heart block, ventricular hypertrophy, ischemic Q or ST changes, or abnormal QT interval). Patients with none of those symptoms or findings were considered low risk. Of those categorized as low risk (n = 115), 47 underwent echocardiogram, only 1 of which was abnormal.

Across studies, the percentage of patients with a normal cardiac history, examination, and ECG with new, significant abnormalities on echocardiogram was 0% in 3 studies (n = 340),4,6,15 2% in 1 study (10/488 patients),5 2.1% in 1 study (1/47 patients),8 and 4.2% in 1 study (8/192 patients).7 The 11 echocardiograms with significant findings in the studies by Mendu et al.5 and Han et al.8 were not further described. The 8 patients with abnormal echocardiograms reported by Chang et al.7 had depressed left ventricular ejection fraction or nonaortic valvular disease that did not represent a definitive etiology of their syncope. Given the cost of $1,000 to $2,220 per study,16 routine echocardiograms in patients with a normal history, examination, and ECG would thus require $60,000 to $132,000 in spending to find 1 new significant abnormality, which may be unrelated to the actual cause of syncope.

SITUATIONS IN WHICH ECHOCARDIOGRAM MAY BE HELPFUL

The diagnostic yield of echocardiogram is higher in patients with a positive cardiac history or abnormal ECG. In the prospective study by Sarasin et al.15 a total of 27% of patients with a positive cardiac history or abnormal ECG were found to have an ejection fraction less than or equal to 40%. Other studies reporting percentages of abnormal echocardiograms in patients with abnormal history, ECG, or examination found rates of 8% (26/333),5 20% (7/35),6 28% (27/97),8 and 29% (27/93).7 It should be noted that not all of these abnormalities were felt to be the cause of syncope. For example, Sarasin et al.15 reported that only half of the patients with newly identified depressed ejection fraction were diagnosed with arrhythmia-related syncope. Chang et al7 reported that 6 of the 27 patients (22%) with abnormal ECG and echocardiogram had the cause of syncope established by echocardiogram.

Finally, some syncope patients will have cardiac biomarkers sent in the ED. Han et al.8 found that among patients with syncope, those with abnormal versus normal echocardiogram were more likely to have elevated BNP (70% vs 23%) and troponin (36% vs 12.4%). Thus, obtaining an echocardiogram in patients with syncope and abnormal cardiac biomarkers may be reasonable. It should be noted, however, that while some studies have suggested a role for biomarkers in differentiating cardiac from noncardiac syncope,17-20 current guidelines state that the usefulness of these tests is uncertain.1

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD OF ECHOCARDIOGRAM FOR ALL PATIENTS

Clinicians should carefully screen patients with syncope for abnormal findings suggesting cardiac disease on history, physical examination, and ECG. Relevant cardiac history includes known coronary artery disease, valvular heart disease, arrhythmia, congestive heart failure, and risk factors for cardiac syncope (supplemental Appendix). The definition of abnormal ECG varies among studies, but abnormalities that should prompt an echocardiogram include arrhythmia, premature atrial or ventricular contractions, second- or third-degree heart block, sinus bradycardia, bundle branch or fascicular blocks, left ventricular hypertrophy, ischemic ST or T wave changes, Q waves, or a prolonged QTc interval. New guidelines from the American College of Cardiology state, “Routine cardiac imaging is not useful in the evaluation of patients with syncope unless cardiac etiology is suspected on the basis of an initial evaluation, including history, physical examination, or ECG.”1

RECOMMENDATIONS

- All patients with syncope should receive a complete history, physical examination, orthostatic vital signs, and ECG.

- Perform echocardiogram on patients with syncope and a history of cardiac disease, examination suggestive of structural heart disease or congestive heart failure, or abnormal ECG.

- Echocardiogram may be reasonable in patients with syncope and abnormal cardiac biomarkers.

CONCLUSIONS

While commonly performed as part of syncope evaluations, echocardiogram has a very low diagnostic yield in patients with a normal history, physical, and ECG. The patient described in the initial case scenario would have an extremely low likelihood of having important diagnostic information found on echocardiogram.

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

The “Things We Do for No Reason” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but which may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

Syncope is a common cause of emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalizations. Echocardiogram is frequently used as a diagnostic tool in the evaluation of syncope, performed in 39%-91% of patients.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A 57-year-old woman presented to the ED after a syncopal episode. She had just eaten dinner when she slumped over and became unresponsive. Her husband estimated that she regained consciousness 30 seconds later and quickly returned to baseline mental status. She denied chest pain, shortness of breath, or palpitations. Her medical history included hypertension and hypothyroidism. Her medication regimen was unchanged.

Vital signs, including orthostatic blood pressures, were within normal ranges. A physical examination revealed regular heart sounds without murmur, rub, or gallop. ECG showed normal sinus rhythm, normal axis, and normal intervals. Chest radiograph, complete blood count, chemistry, pro-brain natriuretic peptide (pro-BNP), and troponin were within normal ranges.

BACKGROUND

Syncope, defined as “abrupt, transient, complete loss of consciousness, associated with inability to maintain postural tone, with rapid and spontaneous recovery,”1 is a common clinical problem, accounting for 1% of ED visits in the United States.2 As syncope has been shown to be associated with increased mortality,3 the primary goal of syncope evaluation is to identify modifiable underlying causes, particularly cardiac causes. Current guidelines recommend a complete history and physical, orthostatic blood pressure measurement, and ECG as the initial evaluation for syncope.1 Echocardiogram is a frequent additional test, performed in 39%-91% of patients.4-8

WHY YOU MAY THINK ECHOCARDIOGRAM IS HELPFUL

Echocardiogram may identify depressed ejection fraction, a risk factor for ventricular arrhythmias, along with structural causes of syncope, including aortic stenosis, pulmonary hypertension, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.9 Structural heart disease is the underlying etiology in about 3% of patients with syncope.10

Prior guidelines stated that “an echocardiogram is a helpful screening test if the history, physical examination, and ECG do not provide a diagnosis or if underlying heart disease is suspected.”11 A separate guideline for the appropriate use of echocardiogram assigned a score of appropriateness on a 1-9 scale based on increasing indication.12 Echocardiogram for syncope was scored a 7 in patients with “no other symptoms or signs of cardiovascular disease.”12 Only 25%-40% of patients with syncope will have a cause identified after the history, physical examination, and ECG,13,14 creating diagnostic uncertainty that often leads to further testing.

WHY ECHOCARDIOGRAM IS NOT NECESSARY IN ALL PATIENTS

Mendu et al.5 performed a single-center, retrospective study of the diagnostic yield of testing for syncope in 2106 consecutive patients older than 65 admitted over the course of 5 years. They retrospectively applied the San Francisco Syncope Rule (SFSR), which patients met if they had congestive heart failure, hematocrit <30%, abnormal ECG, shortness of breath, or systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg. There were 821 patients (39%) who underwent echocardiogram. Among the 488 with no SFSR criteria, 10 patients (2%) had echocardiogram results that affected management, and 4 patients (1%) had results that helped determine the etiology of syncope.

Anderson et al. studied 323 syncope patients in a single ED observation unit over 18 months.6 Patients with high-risk features, including unstable vital signs, abnormal cardiac biomarkers, or ischemic ECG changes, were excluded from the unit. The initial ECG was considered abnormal if it contained arrhythmia, premature atrial or ventricular contractions, pacing, second- or third-degree heart block, or left bundle branch block. Of the 235 patients with a normal ECG who underwent echocardiogram, none had an abnormal study.

Chang et al.7 performed a retrospective review of 468 patients admitted with syncope at a single hospital. Charts were reviewed for ECG and echocardiogram results. Abnormal ECGs were defined as those containing arrhythmias, Q waves, ischemic changes, second- and third-degree heart block, paced rhythm, corrected QT interval (QTc) >500 ms, left bundle branch or bifasicular block, Brugada pattern, or abnormal axis. Among 321 patients with normal ECGs, echocardiograms were performed in 192. Eleven of those echocardiograms were abnormal: 3 demonstrated aortic stenosis in patients who already carried the diagnosis, and the other 8 abnormal echocardiograms revealed unexpected left ventricular ejection fractions <45% or other nonaortic valvular pathology. None of the findings were felt to be the cause of syncope.

Han et al.8 performed a retrospective cohort study of all syncope patients presenting to a single ED over the course of 1 year. Patients were stratified as high risk if they had chest pain, palpitations, a history of cardiac disease (defined as prior arrhythmia, heart failure, coronary artery disease, or structural heart disease), abnormal cardiac biomarkers, or an abnormal ECG (defined as sinus bradycardia, arrhythmia, premature beats, second- or third-degree heart block, ventricular hypertrophy, ischemic Q or ST changes, or abnormal QT interval). Patients with none of those symptoms or findings were considered low risk. Of those categorized as low risk (n = 115), 47 underwent echocardiogram, only 1 of which was abnormal.

Across studies, the percentage of patients with a normal cardiac history, examination, and ECG with new, significant abnormalities on echocardiogram was 0% in 3 studies (n = 340),4,6,15 2% in 1 study (10/488 patients),5 2.1% in 1 study (1/47 patients),8 and 4.2% in 1 study (8/192 patients).7 The 11 echocardiograms with significant findings in the studies by Mendu et al.5 and Han et al.8 were not further described. The 8 patients with abnormal echocardiograms reported by Chang et al.7 had depressed left ventricular ejection fraction or nonaortic valvular disease that did not represent a definitive etiology of their syncope. Given the cost of $1,000 to $2,220 per study,16 routine echocardiograms in patients with a normal history, examination, and ECG would thus require $60,000 to $132,000 in spending to find 1 new significant abnormality, which may be unrelated to the actual cause of syncope.

SITUATIONS IN WHICH ECHOCARDIOGRAM MAY BE HELPFUL

The diagnostic yield of echocardiogram is higher in patients with a positive cardiac history or abnormal ECG. In the prospective study by Sarasin et al.15 a total of 27% of patients with a positive cardiac history or abnormal ECG were found to have an ejection fraction less than or equal to 40%. Other studies reporting percentages of abnormal echocardiograms in patients with abnormal history, ECG, or examination found rates of 8% (26/333),5 20% (7/35),6 28% (27/97),8 and 29% (27/93).7 It should be noted that not all of these abnormalities were felt to be the cause of syncope. For example, Sarasin et al.15 reported that only half of the patients with newly identified depressed ejection fraction were diagnosed with arrhythmia-related syncope. Chang et al7 reported that 6 of the 27 patients (22%) with abnormal ECG and echocardiogram had the cause of syncope established by echocardiogram.

Finally, some syncope patients will have cardiac biomarkers sent in the ED. Han et al.8 found that among patients with syncope, those with abnormal versus normal echocardiogram were more likely to have elevated BNP (70% vs 23%) and troponin (36% vs 12.4%). Thus, obtaining an echocardiogram in patients with syncope and abnormal cardiac biomarkers may be reasonable. It should be noted, however, that while some studies have suggested a role for biomarkers in differentiating cardiac from noncardiac syncope,17-20 current guidelines state that the usefulness of these tests is uncertain.1

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD OF ECHOCARDIOGRAM FOR ALL PATIENTS

Clinicians should carefully screen patients with syncope for abnormal findings suggesting cardiac disease on history, physical examination, and ECG. Relevant cardiac history includes known coronary artery disease, valvular heart disease, arrhythmia, congestive heart failure, and risk factors for cardiac syncope (supplemental Appendix). The definition of abnormal ECG varies among studies, but abnormalities that should prompt an echocardiogram include arrhythmia, premature atrial or ventricular contractions, second- or third-degree heart block, sinus bradycardia, bundle branch or fascicular blocks, left ventricular hypertrophy, ischemic ST or T wave changes, Q waves, or a prolonged QTc interval. New guidelines from the American College of Cardiology state, “Routine cardiac imaging is not useful in the evaluation of patients with syncope unless cardiac etiology is suspected on the basis of an initial evaluation, including history, physical examination, or ECG.”1

RECOMMENDATIONS

- All patients with syncope should receive a complete history, physical examination, orthostatic vital signs, and ECG.

- Perform echocardiogram on patients with syncope and a history of cardiac disease, examination suggestive of structural heart disease or congestive heart failure, or abnormal ECG.

- Echocardiogram may be reasonable in patients with syncope and abnormal cardiac biomarkers.

CONCLUSIONS

While commonly performed as part of syncope evaluations, echocardiogram has a very low diagnostic yield in patients with a normal history, physical, and ECG. The patient described in the initial case scenario would have an extremely low likelihood of having important diagnostic information found on echocardiogram.

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

1. Shen WK, Sheldon RS, Benditt DG, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Patients With Syncope: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines, and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(5):620-633. PubMed

2. Sun BC, Emond JA, Camargo CA Jr. Characteristics and admission patterns of patients presenting with syncope to U.S. emergency departments, 1992-2000. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11(10):1029-1034. PubMed

3. Soteriades ES, Evans JC, Larson MG, et al. Incidence and prognosis of syncope. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(12):878-885. PubMed

4. Recchia D, Barzilai B. Echocardiography in the evaluation of patients with syncope. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10(12):649-655. PubMed

5. Mendu ML, McAvay G, Lampert R, Stoehr J, Tinetti ME. Yield of diagnostic tests in evaluating syncopal episodes in older patients. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(14):1299-1305. PubMed

6. Anderson KL, Limkakeng A, Damuth E, Chandra A. Cardiac evaluation for structural abnormalities may not be required in patients presenting with syncope and a normal ECG result in an observation unit setting. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(4):478-484.e1. PubMed

7. Chang NL, Shah P, Bajaj S, Virk H, Bikkina M, Shamoon F. Diagnostic Yield of Echocardiography in Syncope Patients with Normal ECG. Cardiol Res Pract. 2016;2016:1251637. PubMed

8. Han SK, Yeom SR, Lee SH, et al. Transthoracic echocardiogram in syncope patients with normal initial evaluation. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35(2):281-284. PubMed

9. Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Syncope, European Society of Cardiology, European Heart Rhythm Association, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009). Eur Heart J. 2009;30(21):2631-2671.

10. Alboni P, Brignole M, Menozzi C, et al. Diagnostic value of history in patients with syncope with or without heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37(7):1921-1928. PubMed

11. Strickberger SA, Benson DW, Biaggioni I, et al. AHA/ACCF Scientific Statement on the evaluation of syncope: from the American Heart Association Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Cardiovascular Nursing, Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and Stroke, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group; and the American College of Cardiology Foundation: in collaboration with the Heart Rhythm Society: endorsed by the American Autonomic Society. Circulation. 2006;113(2):316-327. PubMed

12. American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Society of Echocardiography, American Heart Association, et al. ACCF/ASE/AHA/ASNC/HFSA/HRS/SCAI/SCCM/SCCT/SCMR 2011 Appropriate Use Criteria for Echocardiography. A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Society of Echocardiography, American Heart Association, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Critical Care Medicine, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, and Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Endorsed by the American College of Chest Physicians. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(9):1126-1166. PubMed

13. Crane SD. Risk stratification of patients with syncope in an accident and emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2002;19(1):23-27. PubMed

14. Croci F, Brignole M, Alboni P, et al. The application of a standardized strategy of evaluation in patients with syncope referred to three syncope units. Europace. 2002;4(4):351-355. PubMed

15. Sarasin FP, Junod AF, Carballo D, Slama S, Unger PF, Louis-Simonet M. Role of echocardiography in the evaluation of syncope: a prospective study. Heart. 2002;88(4):363-367. PubMed

16. Echocardiogram Cost. http://health.costhelper.com/echocardiograms.html. 2017. Accessed January 26, 2017.

17. Thiruganasambandamoorthy V, Ramaekers R, Rahman MO, et al. Prognostic value of cardiac biomarkers in the risk stratification of syncope: a systematic review. Intern Emerg Med. 2015;10(8):1003-1014. PubMed

18. Pfister R, Diedrichs H, Larbig R, Erdmann E, Schneider CA. NT-pro-BNP for differential diagnosis in patients with syncope. Int J Cardiol. 2009;133(1):51-54. PubMed

19. Reed MJ, Mills NL, Weir CJ. Sensitive troponin assay predicts outcome in syncope. Emerg Med J. 2012;29(12):1001-1003. PubMed

20. Tanimoto K, Yukiiri K, Mizushige K, et al. Usefulness of brain natriuretic peptide as a marker for separating cardiac and noncardiac causes of syncope. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93(2):228-230. PubMed

1. Shen WK, Sheldon RS, Benditt DG, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Patients With Syncope: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines, and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(5):620-633. PubMed

2. Sun BC, Emond JA, Camargo CA Jr. Characteristics and admission patterns of patients presenting with syncope to U.S. emergency departments, 1992-2000. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11(10):1029-1034. PubMed

3. Soteriades ES, Evans JC, Larson MG, et al. Incidence and prognosis of syncope. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(12):878-885. PubMed

4. Recchia D, Barzilai B. Echocardiography in the evaluation of patients with syncope. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10(12):649-655. PubMed

5. Mendu ML, McAvay G, Lampert R, Stoehr J, Tinetti ME. Yield of diagnostic tests in evaluating syncopal episodes in older patients. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(14):1299-1305. PubMed

6. Anderson KL, Limkakeng A, Damuth E, Chandra A. Cardiac evaluation for structural abnormalities may not be required in patients presenting with syncope and a normal ECG result in an observation unit setting. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(4):478-484.e1. PubMed

7. Chang NL, Shah P, Bajaj S, Virk H, Bikkina M, Shamoon F. Diagnostic Yield of Echocardiography in Syncope Patients with Normal ECG. Cardiol Res Pract. 2016;2016:1251637. PubMed

8. Han SK, Yeom SR, Lee SH, et al. Transthoracic echocardiogram in syncope patients with normal initial evaluation. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35(2):281-284. PubMed

9. Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Syncope, European Society of Cardiology, European Heart Rhythm Association, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009). Eur Heart J. 2009;30(21):2631-2671.

10. Alboni P, Brignole M, Menozzi C, et al. Diagnostic value of history in patients with syncope with or without heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37(7):1921-1928. PubMed

11. Strickberger SA, Benson DW, Biaggioni I, et al. AHA/ACCF Scientific Statement on the evaluation of syncope: from the American Heart Association Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Cardiovascular Nursing, Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and Stroke, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group; and the American College of Cardiology Foundation: in collaboration with the Heart Rhythm Society: endorsed by the American Autonomic Society. Circulation. 2006;113(2):316-327. PubMed

12. American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Society of Echocardiography, American Heart Association, et al. ACCF/ASE/AHA/ASNC/HFSA/HRS/SCAI/SCCM/SCCT/SCMR 2011 Appropriate Use Criteria for Echocardiography. A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Society of Echocardiography, American Heart Association, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Critical Care Medicine, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, and Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Endorsed by the American College of Chest Physicians. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(9):1126-1166. PubMed

13. Crane SD. Risk stratification of patients with syncope in an accident and emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2002;19(1):23-27. PubMed

14. Croci F, Brignole M, Alboni P, et al. The application of a standardized strategy of evaluation in patients with syncope referred to three syncope units. Europace. 2002;4(4):351-355. PubMed

15. Sarasin FP, Junod AF, Carballo D, Slama S, Unger PF, Louis-Simonet M. Role of echocardiography in the evaluation of syncope: a prospective study. Heart. 2002;88(4):363-367. PubMed

16. Echocardiogram Cost. http://health.costhelper.com/echocardiograms.html. 2017. Accessed January 26, 2017.

17. Thiruganasambandamoorthy V, Ramaekers R, Rahman MO, et al. Prognostic value of cardiac biomarkers in the risk stratification of syncope: a systematic review. Intern Emerg Med. 2015;10(8):1003-1014. PubMed

18. Pfister R, Diedrichs H, Larbig R, Erdmann E, Schneider CA. NT-pro-BNP for differential diagnosis in patients with syncope. Int J Cardiol. 2009;133(1):51-54. PubMed

19. Reed MJ, Mills NL, Weir CJ. Sensitive troponin assay predicts outcome in syncope. Emerg Med J. 2012;29(12):1001-1003. PubMed

20. Tanimoto K, Yukiiri K, Mizushige K, et al. Usefulness of brain natriuretic peptide as a marker for separating cardiac and noncardiac causes of syncope. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93(2):228-230. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine