User login

What is your diagnosis?

Natural course of primary hepatic angiosarcoma with rupture

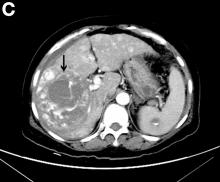

The pathology demonstrated slitlike vascular channels lined by spindle-shaped endothelial cells with large and hyperchromatic nuclei (Figure C). Primary hepatic angiosarcoma (PHA) was diagnosed. The patient declined operation because of poor prognosis and body performance. Ascites tapping was performed, and the fluid was bloody. The patient received a blood transfusion and died 2 days later.

PHA is an aggressive malignant tumor that originates from the endothelium of liver blood vessels. It is a rare condition and accounts for 0.6%-2.0% of all primary liver tumors and less than 5% of all angiosarcomas.1

Most PHAs exhibit no obvious symptoms and signs, particularly when they are small. As the disease progresses, symptoms and signs including abdominal pain, weakness, fatigue, weight loss, hepatomegaly, and ascites occur. The spontaneous rupture of PHA was reported in 15%-27% of patients in a previous study.2 As in our case, no obvious symptoms were noted in the early stage, and spontaneous rupture was observed in the later stage.

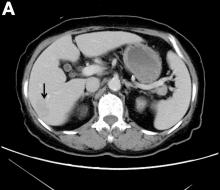

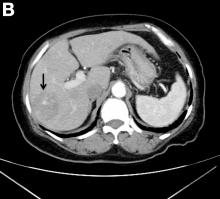

A CT scan of PHA reveals multiple nodules or a dominant mass and a diffusely infiltrating lesion. The tumor is composed of low-density lesions with small heterogeneous hypervascular foci.3 In our patient, a CT scan revealed a hepatic tumor that had a low density when it was small and multiple heterogeneous hypervascular foci when it grew large.

PHAs are very aggressive tumors, and most cases are diagnosed at an advanced stage. The median survival was reported to be 6 months without treatment. Complete resection with clear margins is the choice of treatment; however, the prognosis is poor even after complete resection.2 In our case, operation after diagnosis was declined because of the patient’s poor prognosis and body performance. She lived for 18 months after the diagnosis. The entire natural course of PHA from initial diagnosis to rupture was well presented in our case.

References

1. Zheng YW, Zhang XW, Zhang JL, et al. Primary hepatic angiosarcoma and potential treatment options. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:906–11.

2. Cawich SO, Ramjit C. Herald bleeding from a ruptured primary hepatic angiosarcoma: a case report. Mol Clin Oncol. 2015;3:1063–6.

3. Huang IH, Wu YY, Huang TC, et al. Statistics and outlook of primary hepatic angiosarcoma based on clinical stage. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:3218–22.

Natural course of primary hepatic angiosarcoma with rupture

The pathology demonstrated slitlike vascular channels lined by spindle-shaped endothelial cells with large and hyperchromatic nuclei (Figure C). Primary hepatic angiosarcoma (PHA) was diagnosed. The patient declined operation because of poor prognosis and body performance. Ascites tapping was performed, and the fluid was bloody. The patient received a blood transfusion and died 2 days later.

PHA is an aggressive malignant tumor that originates from the endothelium of liver blood vessels. It is a rare condition and accounts for 0.6%-2.0% of all primary liver tumors and less than 5% of all angiosarcomas.1

Most PHAs exhibit no obvious symptoms and signs, particularly when they are small. As the disease progresses, symptoms and signs including abdominal pain, weakness, fatigue, weight loss, hepatomegaly, and ascites occur. The spontaneous rupture of PHA was reported in 15%-27% of patients in a previous study.2 As in our case, no obvious symptoms were noted in the early stage, and spontaneous rupture was observed in the later stage.

A CT scan of PHA reveals multiple nodules or a dominant mass and a diffusely infiltrating lesion. The tumor is composed of low-density lesions with small heterogeneous hypervascular foci.3 In our patient, a CT scan revealed a hepatic tumor that had a low density when it was small and multiple heterogeneous hypervascular foci when it grew large.

PHAs are very aggressive tumors, and most cases are diagnosed at an advanced stage. The median survival was reported to be 6 months without treatment. Complete resection with clear margins is the choice of treatment; however, the prognosis is poor even after complete resection.2 In our case, operation after diagnosis was declined because of the patient’s poor prognosis and body performance. She lived for 18 months after the diagnosis. The entire natural course of PHA from initial diagnosis to rupture was well presented in our case.

References

1. Zheng YW, Zhang XW, Zhang JL, et al. Primary hepatic angiosarcoma and potential treatment options. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:906–11.

2. Cawich SO, Ramjit C. Herald bleeding from a ruptured primary hepatic angiosarcoma: a case report. Mol Clin Oncol. 2015;3:1063–6.

3. Huang IH, Wu YY, Huang TC, et al. Statistics and outlook of primary hepatic angiosarcoma based on clinical stage. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:3218–22.

Natural course of primary hepatic angiosarcoma with rupture

The pathology demonstrated slitlike vascular channels lined by spindle-shaped endothelial cells with large and hyperchromatic nuclei (Figure C). Primary hepatic angiosarcoma (PHA) was diagnosed. The patient declined operation because of poor prognosis and body performance. Ascites tapping was performed, and the fluid was bloody. The patient received a blood transfusion and died 2 days later.

PHA is an aggressive malignant tumor that originates from the endothelium of liver blood vessels. It is a rare condition and accounts for 0.6%-2.0% of all primary liver tumors and less than 5% of all angiosarcomas.1

Most PHAs exhibit no obvious symptoms and signs, particularly when they are small. As the disease progresses, symptoms and signs including abdominal pain, weakness, fatigue, weight loss, hepatomegaly, and ascites occur. The spontaneous rupture of PHA was reported in 15%-27% of patients in a previous study.2 As in our case, no obvious symptoms were noted in the early stage, and spontaneous rupture was observed in the later stage.

A CT scan of PHA reveals multiple nodules or a dominant mass and a diffusely infiltrating lesion. The tumor is composed of low-density lesions with small heterogeneous hypervascular foci.3 In our patient, a CT scan revealed a hepatic tumor that had a low density when it was small and multiple heterogeneous hypervascular foci when it grew large.

PHAs are very aggressive tumors, and most cases are diagnosed at an advanced stage. The median survival was reported to be 6 months without treatment. Complete resection with clear margins is the choice of treatment; however, the prognosis is poor even after complete resection.2 In our case, operation after diagnosis was declined because of the patient’s poor prognosis and body performance. She lived for 18 months after the diagnosis. The entire natural course of PHA from initial diagnosis to rupture was well presented in our case.

References

1. Zheng YW, Zhang XW, Zhang JL, et al. Primary hepatic angiosarcoma and potential treatment options. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:906–11.

2. Cawich SO, Ramjit C. Herald bleeding from a ruptured primary hepatic angiosarcoma: a case report. Mol Clin Oncol. 2015;3:1063–6.

3. Huang IH, Wu YY, Huang TC, et al. Statistics and outlook of primary hepatic angiosarcoma based on clinical stage. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:3218–22.

What was the diagnosis?

What is your diagnosis? - February 2019

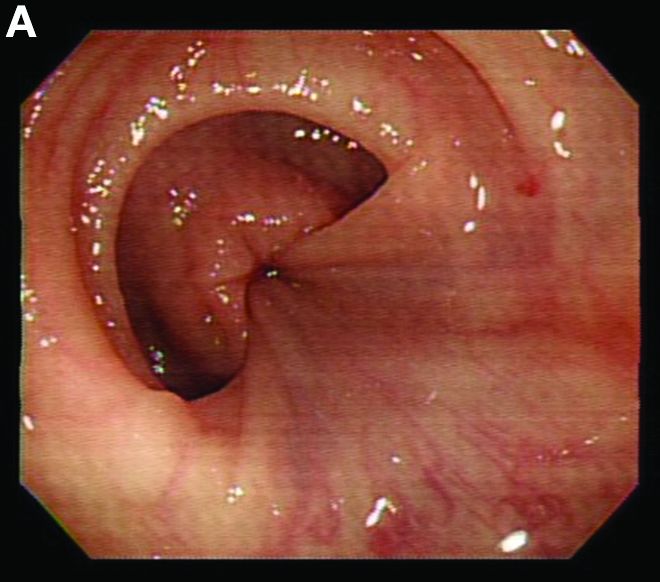

Retrograde colocolic intussusception induced by colonic adenocarcinoma

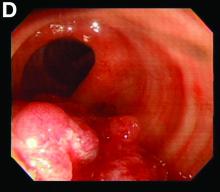

We used biopsy forceps for slow retraction (Figure B) and complete reduction (Figure C). The colonoscope was further inserted up to the cecum and no other lesions were found. A very large polyp was excised partially using a snare for the prevention of repeated intussusception and for histologic examination (Figure D). The pathology revealed adenocarcinoma and the patient underwent surgery. Recovery was uneventful and the patient was discharged 1 week later.

Intussusception is defined as the invagination of a segment of the bowel and its mesentery into the adjacent bowel lumen. It is a common cause of intestinal obstruction in children, but rare in adults. Adult intussusception accounts for 5% of all causes of bowel obstruction and 5%-10% of all intussusception, and usually has a lead point.1 Retrograde colocolic intussusception is especially rare, with only 26 cases reported up to 2014.2 Altered peristalsis in focal areas of the bowel wall can lead to dysrhythmic contractions and cause retrograde intussusception.

Adult colonic intussusception has atypical, nonspecific, intermittent, and vague symptoms and signs, resulting in a diagnostic challenge. Approximately one-half of patients present with symptoms of colonic obstruction with a duration of more than 1 month, as in our case. Many cases involve acute intestinal obstruction and are managed through emergency operation. Ultrasound imaging and computed tomography scans are the most sensitive and most commonly used preoperative diagnostic modalities. Colonoscopy is a useful tool for evaluating intussusception in colocolic intussusception,3 but there is no reported diagnosis of retrograde colocolic intussusception and reduction, as in this case.

Treatment of adult intussusception is more frequently surgical compared with that in children, and leads to resection of the involved bowel segment without reduction before resection.3 In our case, intussusception was reduced easily with biopsy forceps under a direct colonoscopic view and was cured through elective laparoscopic left hemicolectomy after histologic proof was obtained.

References

1. Joseph T, Desai AL. Retrograde intussusception of sigmoid colon. J R Soc Med. 2004;7:127-8.

2.Baba M, Higaki N, Ishida M, et al. A case of retrograde intussusception due to semipedunculated polypiform adenocarcinoma in tubular adenoma of the sigmoid colon in an adult. Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg. 2001;34:282-6.

3. Kamble MA, Thawait AP, Kamble AT. Left side reverse colocolic intussusception secondary to malignant polypoidal growth: a rare clinical entity. Int Surg J. 2014;1:39-42.

Retrograde colocolic intussusception induced by colonic adenocarcinoma

We used biopsy forceps for slow retraction (Figure B) and complete reduction (Figure C). The colonoscope was further inserted up to the cecum and no other lesions were found. A very large polyp was excised partially using a snare for the prevention of repeated intussusception and for histologic examination (Figure D). The pathology revealed adenocarcinoma and the patient underwent surgery. Recovery was uneventful and the patient was discharged 1 week later.

Intussusception is defined as the invagination of a segment of the bowel and its mesentery into the adjacent bowel lumen. It is a common cause of intestinal obstruction in children, but rare in adults. Adult intussusception accounts for 5% of all causes of bowel obstruction and 5%-10% of all intussusception, and usually has a lead point.1 Retrograde colocolic intussusception is especially rare, with only 26 cases reported up to 2014.2 Altered peristalsis in focal areas of the bowel wall can lead to dysrhythmic contractions and cause retrograde intussusception.

Adult colonic intussusception has atypical, nonspecific, intermittent, and vague symptoms and signs, resulting in a diagnostic challenge. Approximately one-half of patients present with symptoms of colonic obstruction with a duration of more than 1 month, as in our case. Many cases involve acute intestinal obstruction and are managed through emergency operation. Ultrasound imaging and computed tomography scans are the most sensitive and most commonly used preoperative diagnostic modalities. Colonoscopy is a useful tool for evaluating intussusception in colocolic intussusception,3 but there is no reported diagnosis of retrograde colocolic intussusception and reduction, as in this case.

Treatment of adult intussusception is more frequently surgical compared with that in children, and leads to resection of the involved bowel segment without reduction before resection.3 In our case, intussusception was reduced easily with biopsy forceps under a direct colonoscopic view and was cured through elective laparoscopic left hemicolectomy after histologic proof was obtained.

References

1. Joseph T, Desai AL. Retrograde intussusception of sigmoid colon. J R Soc Med. 2004;7:127-8.

2.Baba M, Higaki N, Ishida M, et al. A case of retrograde intussusception due to semipedunculated polypiform adenocarcinoma in tubular adenoma of the sigmoid colon in an adult. Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg. 2001;34:282-6.

3. Kamble MA, Thawait AP, Kamble AT. Left side reverse colocolic intussusception secondary to malignant polypoidal growth: a rare clinical entity. Int Surg J. 2014;1:39-42.

Retrograde colocolic intussusception induced by colonic adenocarcinoma

We used biopsy forceps for slow retraction (Figure B) and complete reduction (Figure C). The colonoscope was further inserted up to the cecum and no other lesions were found. A very large polyp was excised partially using a snare for the prevention of repeated intussusception and for histologic examination (Figure D). The pathology revealed adenocarcinoma and the patient underwent surgery. Recovery was uneventful and the patient was discharged 1 week later.

Intussusception is defined as the invagination of a segment of the bowel and its mesentery into the adjacent bowel lumen. It is a common cause of intestinal obstruction in children, but rare in adults. Adult intussusception accounts for 5% of all causes of bowel obstruction and 5%-10% of all intussusception, and usually has a lead point.1 Retrograde colocolic intussusception is especially rare, with only 26 cases reported up to 2014.2 Altered peristalsis in focal areas of the bowel wall can lead to dysrhythmic contractions and cause retrograde intussusception.

Adult colonic intussusception has atypical, nonspecific, intermittent, and vague symptoms and signs, resulting in a diagnostic challenge. Approximately one-half of patients present with symptoms of colonic obstruction with a duration of more than 1 month, as in our case. Many cases involve acute intestinal obstruction and are managed through emergency operation. Ultrasound imaging and computed tomography scans are the most sensitive and most commonly used preoperative diagnostic modalities. Colonoscopy is a useful tool for evaluating intussusception in colocolic intussusception,3 but there is no reported diagnosis of retrograde colocolic intussusception and reduction, as in this case.

Treatment of adult intussusception is more frequently surgical compared with that in children, and leads to resection of the involved bowel segment without reduction before resection.3 In our case, intussusception was reduced easily with biopsy forceps under a direct colonoscopic view and was cured through elective laparoscopic left hemicolectomy after histologic proof was obtained.

References

1. Joseph T, Desai AL. Retrograde intussusception of sigmoid colon. J R Soc Med. 2004;7:127-8.

2.Baba M, Higaki N, Ishida M, et al. A case of retrograde intussusception due to semipedunculated polypiform adenocarcinoma in tubular adenoma of the sigmoid colon in an adult. Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg. 2001;34:282-6.

3. Kamble MA, Thawait AP, Kamble AT. Left side reverse colocolic intussusception secondary to malignant polypoidal growth: a rare clinical entity. Int Surg J. 2014;1:39-42.