User login

Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist: Anaphylaxis Management in Adults and Children

Anaphylaxis, an acute, life-threatening allergic response, affects multiple organ systems and manifests variably. Anaphylaxis is likely taking place if one or more of the following occurs: (a) sudden- onset skin and mucosal tissue swelling, (b) skin and mucosal abnormalities or respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms after exposure to an allergen, or (c) reduced blood pressure after exposure to an allergen. With an estimated lifetime prevalence of up to 5.1%, it is a significant cause of morbidity in adults and children.1 The 2020 anaphylaxis practice parameter update provides recommendations on treatment, prevention, and assessment of biphasic symptom risk in patients experiencing anaphylaxis.2 The guideline provides five key recommendations and four good-practice statements, which we have consolidated into five recommendations for this update.

KEY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE HOSPITALIST

Recommendation 1. All patients with suspected or confirmed anaphylaxis should be treated with epinephrine. (Good-practice statement)

Self-injectable epinephrine is the first-line treatment for anaphylaxis, with weight-based dosing of 0.15 mg/kg for children weighing less than 30 kg and 0.30 mg/kg for children weighing more than 30 kg and adults. Delayed administration of epinephrine can increase anaphylaxis-associated morbidity and mortality. After epinephrine administration, patients should be observed in a healthcare setting for symptom resolution.

Recommendation 2. For all patients, clinicians should assess the risk for developing biphasic anaphylaxis. (Conditional recommendation, very low quality of evidence)

Biphasic anaphylaxis is defined as the return of anaphylaxis symptoms after an asymptomatic period of at least 1 hour, all during a single instance of anaphylaxis. Biphasic anaphylaxis occurs in up to 20% of patients.3 Biphasic anaphylaxis is more likely among patients receiving repeated doses of epinephrine (odds ratio [OR], 4.82; 95% CI, 2.70-8.58), delayed epinephrine administration greater than 60 minutes (OR, 2.29; 95% CI, 1.09-4.79), or a severe initial presentation (OR, 4.82; 95% CI, 1.23-3.61).2 The presence of any of these risk factors raises the risk for developing biphasic anaphylaxis by 17%.4 Severe anaphylaxis is characterized by life-threatening symptoms, including loss of consciousness, syncope or dizziness, hypotension, cardiovascular system collapse, or neurologic dysfunction from hypoperfusion or hypoxia after exposure to an allergen.5

Other risk factors for biphasic anaphylaxis in all ages include a widened pulse pressure, unknown anaphylaxis trigger, and cutaneous signs and symptoms. Drug triggers are also a risk factor in pediatric patients.2

Recommendation 3. All patients with anaphylaxis and risk factors for biphasic anaphylaxis should undergo extended clinical observation in a setting capable of managing anaphylaxis. (Conditional recommendation, very low quality of evidence)

All patients should be monitored for resolution of symptoms prior to discharge, regardless of age or severity at onset. Patients with all three of the following can be discharged 1 hour after symptom resolution because these three factors together have a 95% negative predictive value for biphasic anaphylaxis: nonsevere anaphylaxis, prompt response to epinephrine, and access to medical care.5 In contrast, extended observation of at least 6 hours should be offered to patients with increased risk of biphasic reactions. Patients who have potentially fatal underlying illnesses (eg, severe respiratory or cardiac disease), poor access to emergency medical services, poor self-management skills, or inability to access epinephrine should also be considered for extended observation or hospitalization. Evidence is lacking to define the optimal observation time because extended biphasic reactions can occur from 1 to 78 hours after initial anaphylaxis symptoms.6

Given the lack of specific evidence around length of observation, there is an opportunity for shared decision-making. Every patient should receive education regarding trigger avoidance, reasons to seek care or activate emergency medical services, and warning signs of biphasic anaphylaxis. Additionally, self-injectable epinephrine and an action plan detailing how and when to administer the epinephrine should be provided. Patients with anaphylaxis should follow up with an allergist.

Recommendation 4. Administration of glucocorticoids or antihistamines for prevention of biphasic anaphylaxis is not recommended. (Conditional recommendation, very low quality of evidence)

This guideline discourages glucocorticoids and antihistamines as a primary treatment as it may delay epinephrine administration. Despite treating the cutaneous manifestations of anaphylaxis, antihistamines fail to treat the life-threatening cardiovascular and respiratory symptoms. No clear evidence exists on whether antihistamines or glucocorticoids prevent biphasic anaphylaxis.

Recommendation 5. In adult patients receiving chemotherapy, premedication with antihistamine and/or glucocorticoid should be used to prevent anaphylaxis or infusion-related reactions for some chemotherapeutic agents in patients with no previous reaction to the drug. (Conditional recommendation, very low quality of evidence)

Premedication with antihistamines and/or glucocorticoids was associated with 51% reduced odds for anaphylaxis and infusion-related reactions to certain chemotherapy agents (pegaspargase, docetaxel, carboplatin, oxaliplatin, and rituximab) in adults who had not previously experienced a reaction to the drug (OR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.37-0.66).2 However, this same benefit was not found with other chemotherapy agents for patients without a prior allergic reaction to the agent, which allows clinicians to defer premedication. The benefit of premedication with antihistamines and/or glucocorticoids to patients with prior anaphylactic reactions to chemotherapy agents was not evaluated in this guideline, nor was the role premedication plays in desensitization to chemotherapy.

CRITIQUE

This guideline was created by a panel of allergists, clinical immunologists, and methodologists using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations) approach to draft recommendations. Conflicts of interest (COI) were disclosed by all panel members according to the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (AAAAI) guidelines. The inclusion of many observational studies and meta-analyses improves the generalizability of the guideline. The authors highlighted the low certainty of evidence due to the lack of randomized controlled trials and significant heterogeneity of the included studies.

Some recommendations in the guideline have implications for costs of care. A recent economic analysis looked at cost-effectiveness for extended observation for anaphylaxis and found it was cost-effective only when patients were at increased risk for biphasic anaphylaxis.7 Although Recommendation 4 advises against the use of glucocorticoids for prevention of biphasic anaphylaxis, one retrospective cohort study demonstrated that glucocorticoid use was associated with decreased length of stay in children admitted with anaphylaxis.8 Therefore, the recommendation to avoid glucocorticoids for prevention of biphasic anaphylaxis could possibly increase hospital length of stay for children. The usefulness of dexamethasone to prevent biphasic anaphylaxis in children 3 to 14 months old is being evaluated in a randomized trial (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03523221).

AREAS OF FUTURE STUDY

Future research should better characterize risk factors for biphasic reactions to aid in clinical triage and diagnosis. Additional studies are needed to determine the optimal observation duration for patients experiencing anaphylactic reactions or requiring multiple doses of epinephrine. The role of premedication in patients receiving chemotherapy is poorly described, with few studies evaluating the benefit of premedication in patients with previous anaphylactic reactions.

1. Wood RA, Camargo CA Jr, Lieberman P, et al. Anaphylaxis in America: the prevalence and characteristics of anaphylaxis in the United States. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(2):461-467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2013.08.016

2. Shaker MS, Wallace DV, Golden DBK, et al. Anaphylaxis-a 2020 practice parameter update, systematic review, and Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(4):1082-1123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2020.01.017

3. Lieberman P, Camargo CA Jr, Bohlke K, et al. Epidemiology of anaphylaxis: findings of the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Epidemiology of Anaphylaxis Working Group. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97(5):596-602. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1081-1206(10)61086-1

4. Kim TH, Yoon SH, Hong H, Kang HR, Cho SH, Lee SY. Duration of observation for detecting a biphasic reaction in anaphylaxis: a meta-analysis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2019;179(1):31-36. https://doi.org/10.1159/000496092

5. Brown AF, Mckinnon D, Chu K. Emergency department anaphylaxis: a review of 142 patients in a single year. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108(5):861-866. https://doi.org/10.1067/mai.2001.119028

6. Pourmand A, Robinson C, Syed W, Mazer-Amirshahi M. Biphasic anaphylaxis: a review of the literature and implications for emergency management. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(8):1480-1485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2018.05.009

7. Shaker M, Wallace D, Golden DBK, Oppenheimer J, Greenhawt M. Simulation of health and economic benefits of extended observation of resolved anaphylaxis. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(10):e1913951. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.13951

8. Michelson KA, Monuteaux MC, Neuman MI. Glucocorticoids and hospital length of stay for children with anaphylaxis: a retrospective study. J Pediatr. 2015;167(3):719-724.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.05.033

Anaphylaxis, an acute, life-threatening allergic response, affects multiple organ systems and manifests variably. Anaphylaxis is likely taking place if one or more of the following occurs: (a) sudden- onset skin and mucosal tissue swelling, (b) skin and mucosal abnormalities or respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms after exposure to an allergen, or (c) reduced blood pressure after exposure to an allergen. With an estimated lifetime prevalence of up to 5.1%, it is a significant cause of morbidity in adults and children.1 The 2020 anaphylaxis practice parameter update provides recommendations on treatment, prevention, and assessment of biphasic symptom risk in patients experiencing anaphylaxis.2 The guideline provides five key recommendations and four good-practice statements, which we have consolidated into five recommendations for this update.

KEY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE HOSPITALIST

Recommendation 1. All patients with suspected or confirmed anaphylaxis should be treated with epinephrine. (Good-practice statement)

Self-injectable epinephrine is the first-line treatment for anaphylaxis, with weight-based dosing of 0.15 mg/kg for children weighing less than 30 kg and 0.30 mg/kg for children weighing more than 30 kg and adults. Delayed administration of epinephrine can increase anaphylaxis-associated morbidity and mortality. After epinephrine administration, patients should be observed in a healthcare setting for symptom resolution.

Recommendation 2. For all patients, clinicians should assess the risk for developing biphasic anaphylaxis. (Conditional recommendation, very low quality of evidence)

Biphasic anaphylaxis is defined as the return of anaphylaxis symptoms after an asymptomatic period of at least 1 hour, all during a single instance of anaphylaxis. Biphasic anaphylaxis occurs in up to 20% of patients.3 Biphasic anaphylaxis is more likely among patients receiving repeated doses of epinephrine (odds ratio [OR], 4.82; 95% CI, 2.70-8.58), delayed epinephrine administration greater than 60 minutes (OR, 2.29; 95% CI, 1.09-4.79), or a severe initial presentation (OR, 4.82; 95% CI, 1.23-3.61).2 The presence of any of these risk factors raises the risk for developing biphasic anaphylaxis by 17%.4 Severe anaphylaxis is characterized by life-threatening symptoms, including loss of consciousness, syncope or dizziness, hypotension, cardiovascular system collapse, or neurologic dysfunction from hypoperfusion or hypoxia after exposure to an allergen.5

Other risk factors for biphasic anaphylaxis in all ages include a widened pulse pressure, unknown anaphylaxis trigger, and cutaneous signs and symptoms. Drug triggers are also a risk factor in pediatric patients.2

Recommendation 3. All patients with anaphylaxis and risk factors for biphasic anaphylaxis should undergo extended clinical observation in a setting capable of managing anaphylaxis. (Conditional recommendation, very low quality of evidence)

All patients should be monitored for resolution of symptoms prior to discharge, regardless of age or severity at onset. Patients with all three of the following can be discharged 1 hour after symptom resolution because these three factors together have a 95% negative predictive value for biphasic anaphylaxis: nonsevere anaphylaxis, prompt response to epinephrine, and access to medical care.5 In contrast, extended observation of at least 6 hours should be offered to patients with increased risk of biphasic reactions. Patients who have potentially fatal underlying illnesses (eg, severe respiratory or cardiac disease), poor access to emergency medical services, poor self-management skills, or inability to access epinephrine should also be considered for extended observation or hospitalization. Evidence is lacking to define the optimal observation time because extended biphasic reactions can occur from 1 to 78 hours after initial anaphylaxis symptoms.6

Given the lack of specific evidence around length of observation, there is an opportunity for shared decision-making. Every patient should receive education regarding trigger avoidance, reasons to seek care or activate emergency medical services, and warning signs of biphasic anaphylaxis. Additionally, self-injectable epinephrine and an action plan detailing how and when to administer the epinephrine should be provided. Patients with anaphylaxis should follow up with an allergist.

Recommendation 4. Administration of glucocorticoids or antihistamines for prevention of biphasic anaphylaxis is not recommended. (Conditional recommendation, very low quality of evidence)

This guideline discourages glucocorticoids and antihistamines as a primary treatment as it may delay epinephrine administration. Despite treating the cutaneous manifestations of anaphylaxis, antihistamines fail to treat the life-threatening cardiovascular and respiratory symptoms. No clear evidence exists on whether antihistamines or glucocorticoids prevent biphasic anaphylaxis.

Recommendation 5. In adult patients receiving chemotherapy, premedication with antihistamine and/or glucocorticoid should be used to prevent anaphylaxis or infusion-related reactions for some chemotherapeutic agents in patients with no previous reaction to the drug. (Conditional recommendation, very low quality of evidence)

Premedication with antihistamines and/or glucocorticoids was associated with 51% reduced odds for anaphylaxis and infusion-related reactions to certain chemotherapy agents (pegaspargase, docetaxel, carboplatin, oxaliplatin, and rituximab) in adults who had not previously experienced a reaction to the drug (OR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.37-0.66).2 However, this same benefit was not found with other chemotherapy agents for patients without a prior allergic reaction to the agent, which allows clinicians to defer premedication. The benefit of premedication with antihistamines and/or glucocorticoids to patients with prior anaphylactic reactions to chemotherapy agents was not evaluated in this guideline, nor was the role premedication plays in desensitization to chemotherapy.

CRITIQUE

This guideline was created by a panel of allergists, clinical immunologists, and methodologists using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations) approach to draft recommendations. Conflicts of interest (COI) were disclosed by all panel members according to the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (AAAAI) guidelines. The inclusion of many observational studies and meta-analyses improves the generalizability of the guideline. The authors highlighted the low certainty of evidence due to the lack of randomized controlled trials and significant heterogeneity of the included studies.

Some recommendations in the guideline have implications for costs of care. A recent economic analysis looked at cost-effectiveness for extended observation for anaphylaxis and found it was cost-effective only when patients were at increased risk for biphasic anaphylaxis.7 Although Recommendation 4 advises against the use of glucocorticoids for prevention of biphasic anaphylaxis, one retrospective cohort study demonstrated that glucocorticoid use was associated with decreased length of stay in children admitted with anaphylaxis.8 Therefore, the recommendation to avoid glucocorticoids for prevention of biphasic anaphylaxis could possibly increase hospital length of stay for children. The usefulness of dexamethasone to prevent biphasic anaphylaxis in children 3 to 14 months old is being evaluated in a randomized trial (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03523221).

AREAS OF FUTURE STUDY

Future research should better characterize risk factors for biphasic reactions to aid in clinical triage and diagnosis. Additional studies are needed to determine the optimal observation duration for patients experiencing anaphylactic reactions or requiring multiple doses of epinephrine. The role of premedication in patients receiving chemotherapy is poorly described, with few studies evaluating the benefit of premedication in patients with previous anaphylactic reactions.

Anaphylaxis, an acute, life-threatening allergic response, affects multiple organ systems and manifests variably. Anaphylaxis is likely taking place if one or more of the following occurs: (a) sudden- onset skin and mucosal tissue swelling, (b) skin and mucosal abnormalities or respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms after exposure to an allergen, or (c) reduced blood pressure after exposure to an allergen. With an estimated lifetime prevalence of up to 5.1%, it is a significant cause of morbidity in adults and children.1 The 2020 anaphylaxis practice parameter update provides recommendations on treatment, prevention, and assessment of biphasic symptom risk in patients experiencing anaphylaxis.2 The guideline provides five key recommendations and four good-practice statements, which we have consolidated into five recommendations for this update.

KEY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE HOSPITALIST

Recommendation 1. All patients with suspected or confirmed anaphylaxis should be treated with epinephrine. (Good-practice statement)

Self-injectable epinephrine is the first-line treatment for anaphylaxis, with weight-based dosing of 0.15 mg/kg for children weighing less than 30 kg and 0.30 mg/kg for children weighing more than 30 kg and adults. Delayed administration of epinephrine can increase anaphylaxis-associated morbidity and mortality. After epinephrine administration, patients should be observed in a healthcare setting for symptom resolution.

Recommendation 2. For all patients, clinicians should assess the risk for developing biphasic anaphylaxis. (Conditional recommendation, very low quality of evidence)

Biphasic anaphylaxis is defined as the return of anaphylaxis symptoms after an asymptomatic period of at least 1 hour, all during a single instance of anaphylaxis. Biphasic anaphylaxis occurs in up to 20% of patients.3 Biphasic anaphylaxis is more likely among patients receiving repeated doses of epinephrine (odds ratio [OR], 4.82; 95% CI, 2.70-8.58), delayed epinephrine administration greater than 60 minutes (OR, 2.29; 95% CI, 1.09-4.79), or a severe initial presentation (OR, 4.82; 95% CI, 1.23-3.61).2 The presence of any of these risk factors raises the risk for developing biphasic anaphylaxis by 17%.4 Severe anaphylaxis is characterized by life-threatening symptoms, including loss of consciousness, syncope or dizziness, hypotension, cardiovascular system collapse, or neurologic dysfunction from hypoperfusion or hypoxia after exposure to an allergen.5

Other risk factors for biphasic anaphylaxis in all ages include a widened pulse pressure, unknown anaphylaxis trigger, and cutaneous signs and symptoms. Drug triggers are also a risk factor in pediatric patients.2

Recommendation 3. All patients with anaphylaxis and risk factors for biphasic anaphylaxis should undergo extended clinical observation in a setting capable of managing anaphylaxis. (Conditional recommendation, very low quality of evidence)

All patients should be monitored for resolution of symptoms prior to discharge, regardless of age or severity at onset. Patients with all three of the following can be discharged 1 hour after symptom resolution because these three factors together have a 95% negative predictive value for biphasic anaphylaxis: nonsevere anaphylaxis, prompt response to epinephrine, and access to medical care.5 In contrast, extended observation of at least 6 hours should be offered to patients with increased risk of biphasic reactions. Patients who have potentially fatal underlying illnesses (eg, severe respiratory or cardiac disease), poor access to emergency medical services, poor self-management skills, or inability to access epinephrine should also be considered for extended observation or hospitalization. Evidence is lacking to define the optimal observation time because extended biphasic reactions can occur from 1 to 78 hours after initial anaphylaxis symptoms.6

Given the lack of specific evidence around length of observation, there is an opportunity for shared decision-making. Every patient should receive education regarding trigger avoidance, reasons to seek care or activate emergency medical services, and warning signs of biphasic anaphylaxis. Additionally, self-injectable epinephrine and an action plan detailing how and when to administer the epinephrine should be provided. Patients with anaphylaxis should follow up with an allergist.

Recommendation 4. Administration of glucocorticoids or antihistamines for prevention of biphasic anaphylaxis is not recommended. (Conditional recommendation, very low quality of evidence)

This guideline discourages glucocorticoids and antihistamines as a primary treatment as it may delay epinephrine administration. Despite treating the cutaneous manifestations of anaphylaxis, antihistamines fail to treat the life-threatening cardiovascular and respiratory symptoms. No clear evidence exists on whether antihistamines or glucocorticoids prevent biphasic anaphylaxis.

Recommendation 5. In adult patients receiving chemotherapy, premedication with antihistamine and/or glucocorticoid should be used to prevent anaphylaxis or infusion-related reactions for some chemotherapeutic agents in patients with no previous reaction to the drug. (Conditional recommendation, very low quality of evidence)

Premedication with antihistamines and/or glucocorticoids was associated with 51% reduced odds for anaphylaxis and infusion-related reactions to certain chemotherapy agents (pegaspargase, docetaxel, carboplatin, oxaliplatin, and rituximab) in adults who had not previously experienced a reaction to the drug (OR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.37-0.66).2 However, this same benefit was not found with other chemotherapy agents for patients without a prior allergic reaction to the agent, which allows clinicians to defer premedication. The benefit of premedication with antihistamines and/or glucocorticoids to patients with prior anaphylactic reactions to chemotherapy agents was not evaluated in this guideline, nor was the role premedication plays in desensitization to chemotherapy.

CRITIQUE

This guideline was created by a panel of allergists, clinical immunologists, and methodologists using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations) approach to draft recommendations. Conflicts of interest (COI) were disclosed by all panel members according to the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (AAAAI) guidelines. The inclusion of many observational studies and meta-analyses improves the generalizability of the guideline. The authors highlighted the low certainty of evidence due to the lack of randomized controlled trials and significant heterogeneity of the included studies.

Some recommendations in the guideline have implications for costs of care. A recent economic analysis looked at cost-effectiveness for extended observation for anaphylaxis and found it was cost-effective only when patients were at increased risk for biphasic anaphylaxis.7 Although Recommendation 4 advises against the use of glucocorticoids for prevention of biphasic anaphylaxis, one retrospective cohort study demonstrated that glucocorticoid use was associated with decreased length of stay in children admitted with anaphylaxis.8 Therefore, the recommendation to avoid glucocorticoids for prevention of biphasic anaphylaxis could possibly increase hospital length of stay for children. The usefulness of dexamethasone to prevent biphasic anaphylaxis in children 3 to 14 months old is being evaluated in a randomized trial (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03523221).

AREAS OF FUTURE STUDY

Future research should better characterize risk factors for biphasic reactions to aid in clinical triage and diagnosis. Additional studies are needed to determine the optimal observation duration for patients experiencing anaphylactic reactions or requiring multiple doses of epinephrine. The role of premedication in patients receiving chemotherapy is poorly described, with few studies evaluating the benefit of premedication in patients with previous anaphylactic reactions.

1. Wood RA, Camargo CA Jr, Lieberman P, et al. Anaphylaxis in America: the prevalence and characteristics of anaphylaxis in the United States. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(2):461-467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2013.08.016

2. Shaker MS, Wallace DV, Golden DBK, et al. Anaphylaxis-a 2020 practice parameter update, systematic review, and Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(4):1082-1123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2020.01.017

3. Lieberman P, Camargo CA Jr, Bohlke K, et al. Epidemiology of anaphylaxis: findings of the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Epidemiology of Anaphylaxis Working Group. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97(5):596-602. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1081-1206(10)61086-1

4. Kim TH, Yoon SH, Hong H, Kang HR, Cho SH, Lee SY. Duration of observation for detecting a biphasic reaction in anaphylaxis: a meta-analysis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2019;179(1):31-36. https://doi.org/10.1159/000496092

5. Brown AF, Mckinnon D, Chu K. Emergency department anaphylaxis: a review of 142 patients in a single year. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108(5):861-866. https://doi.org/10.1067/mai.2001.119028

6. Pourmand A, Robinson C, Syed W, Mazer-Amirshahi M. Biphasic anaphylaxis: a review of the literature and implications for emergency management. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(8):1480-1485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2018.05.009

7. Shaker M, Wallace D, Golden DBK, Oppenheimer J, Greenhawt M. Simulation of health and economic benefits of extended observation of resolved anaphylaxis. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(10):e1913951. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.13951

8. Michelson KA, Monuteaux MC, Neuman MI. Glucocorticoids and hospital length of stay for children with anaphylaxis: a retrospective study. J Pediatr. 2015;167(3):719-724.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.05.033

1. Wood RA, Camargo CA Jr, Lieberman P, et al. Anaphylaxis in America: the prevalence and characteristics of anaphylaxis in the United States. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(2):461-467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2013.08.016

2. Shaker MS, Wallace DV, Golden DBK, et al. Anaphylaxis-a 2020 practice parameter update, systematic review, and Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(4):1082-1123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2020.01.017

3. Lieberman P, Camargo CA Jr, Bohlke K, et al. Epidemiology of anaphylaxis: findings of the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Epidemiology of Anaphylaxis Working Group. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97(5):596-602. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1081-1206(10)61086-1

4. Kim TH, Yoon SH, Hong H, Kang HR, Cho SH, Lee SY. Duration of observation for detecting a biphasic reaction in anaphylaxis: a meta-analysis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2019;179(1):31-36. https://doi.org/10.1159/000496092

5. Brown AF, Mckinnon D, Chu K. Emergency department anaphylaxis: a review of 142 patients in a single year. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108(5):861-866. https://doi.org/10.1067/mai.2001.119028

6. Pourmand A, Robinson C, Syed W, Mazer-Amirshahi M. Biphasic anaphylaxis: a review of the literature and implications for emergency management. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(8):1480-1485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2018.05.009

7. Shaker M, Wallace D, Golden DBK, Oppenheimer J, Greenhawt M. Simulation of health and economic benefits of extended observation of resolved anaphylaxis. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(10):e1913951. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.13951

8. Michelson KA, Monuteaux MC, Neuman MI. Glucocorticoids and hospital length of stay for children with anaphylaxis: a retrospective study. J Pediatr. 2015;167(3):719-724.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.05.033

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Clinical Guideline Highlights for the Hospitalist: 2019 American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America Update on Community-Acquired Pneumonia

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is the second most common cause of hospitalization in the United States, with over 1.5 million unique hospitalizations annually.1 CAP is also the most common infectious cause of death in US adults.2 The 2019 CAP guideline from the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) provides recommendations on the diagnosis and management of CAP. The guideline provides 16 recommendations, which we have consolidated to highlight practice changing updates in diagnostic testing, risk stratification, and treatment.

KEY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE HOSPITALIST

Diagnostic Testing

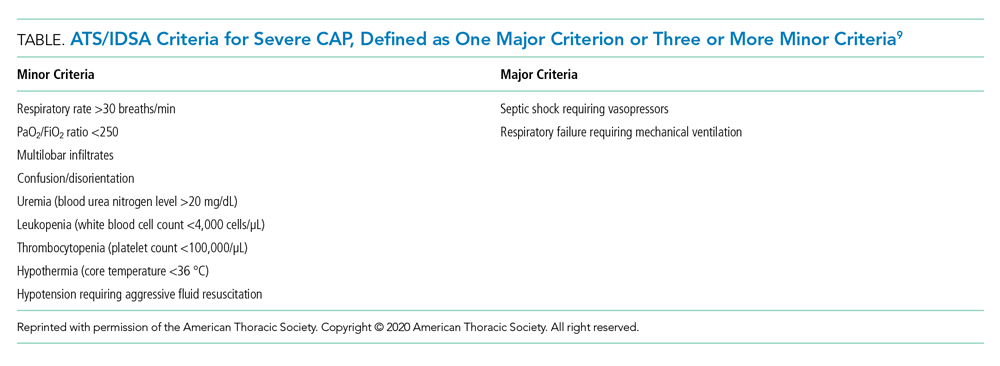

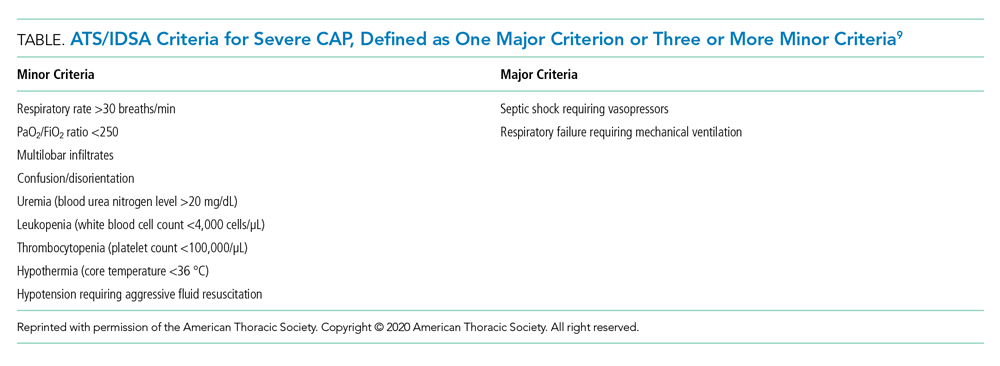

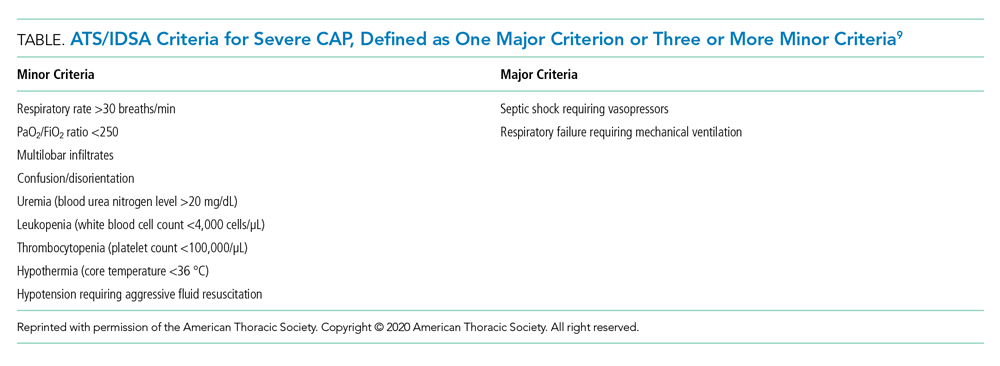

Recommendation 1. In patients with CAP, routine blood cultures, sputum cultures, and urinary antigen tests are not routinely recommended unless severe CAP (Table), history of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and/or Pseudomonas infection, or prior hospitalization for which intravenous antibiotics were administered. (Strong recommendation; very low quality of evidence)

The guideline emphasizes that the diagnostic yield of blood/sputum cultures and urinary antigen testing is low. Additionally, high-quality data showing improved clinical outcomes with routine testing of blood cultures and urinary antigens are lacking. Instead, the guideline suggests obtaining blood cultures, urinary antigens, and sputum gram stain and culture only for patients with severe CAP and those being treated for or having prior infection with MRSA or P aeruginosa. They recommend narrowing therapy as appropriate if cultures are negative for either of these two organisms or previous hospitalization with intravenous antibiotics.

Risk Stratification

Recommendation 2. In patients with CAP, Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) or CURB-65 (tool based on confusion, urea level, respiratory rate, blood pressure, and age 65 years or older) scores should not be used to determine general medical ward vs intensive care unit care (ICU). (Strong recommendation; low quality of evidence)

The PSI and CURB-65 scores are not validated to determine location of hospital care. Multiple prognostic models have been studied to predict the need for ICU-level care including SMART-COP (systolic blood pressure, multilobar chest radiography involvement, albumin level, respiratory rate, tachycardia, confusion, oxygenation, and arterial pH), SCAPA (Study of Community Acquired Pneumonia Aetiology), and the ATS/IDSA criteria (Table). The positive and negative likelihood ratios for needing ICU admission in CAP with either one major or three or more minor ATS/IDSA criteria are 3.28 and 0.21, respectively.

Treatment

Recommendation 3a. In patients with nonsevere CAP and no risk factors for MRSA or Pseudomonas infection, empiric treatment with a ß-lactam plus macrolide or monotherapy with fluoroquinolones is recommended. (Strong recommendation; high quality of evidence)

Recommendation 3b. In patients with severe CAP and no risk factors for MRSA or Pseudomonas infection, empiric treatment with a ß-lactam plus either a macrolide or fluoroquinolone is recommended. (Strong recommendation; low to moderate quality of evidence)

Microbiologic risk assessment is critical. Risk factors for MRSA or P aeruginosa pneumonia include isolation of these agents in culture and recent hospitalization with receipt of parenteral antibiotics. ß-Lactam monotherapy is not recommended because previous randomized clinical trials (RCTs) demonstrated inferiority of ß-lactam monotherapy to combination therapy for resolution of CAP. The recommended combination therapy for patients with severe CAP without risk factors for MRSA or P aeruginosa infection is a ß-lactam plus either a macrolide or a respiratory fluoroquinolone.

Recommendation 4. In patients with suspected aspiration pneumonia, additional anaerobic coverage is not routinely recommended. (Conditional recommendation; very low quality of evidence)

Aspiration often causes a self-limited pneumonitis that will resolve in 24 to 48 hours with supportive care. Use of additional anaerobic coverage in these patients increases risk for complications (eg, Clostridioides difficile infection) without improving outcomes.

Recommendation 5. In patients with nonsevere CAP, corticosteroids are not routinely recommended. (Conditional recommendation; moderate quality of evidence)

There is no direct evidence that steroids reduce mortality or organ failure in nonsevere CAP. Additionally, the use of steroids in CAP can come with considerable risks (eg, secondary infection, hyperglycemia).

Recommendation 6. In hospitalized patients with CAP, empiric coverage for MRSA or P aeruginosa should be limited to patients meeting specific criteria. (Strong recommendation; moderate quality of evidence)

The guideline highlights the current overuse of extended spectrum antibiotics in patients meeting the previous definition of healthcare-associated pneumonia (HCAP). HCAP was defined by the presence of new chest x-ray infiltrates in patients with various exposures to healthcare settings (eg, chronic dialysis, infusion centers, emergency rooms). Antimicrobial therapy covering MRSA or P aeruginosa should be reserved for patients at risk for MRSA or P aeruginosa infection unless microbiologic testing is negative. Empiric antibiotic selection should incorporate local resistance patterns guided by hospital antibiograms.

Recommendation 7. In adults with CAP, antibiotics should be continued for no less than 5 days with documented clinical stability. (Strong recommendation; moderate quality of evidence)

Hospitalists often determine the length of antibiotic therapy for CAP. Recent studies show extended antibiotic treatment for pneumonia increases risk for adverse events without improving outcomes. Studies also demonstrate patients who receive 5 days of antibiotics total after achieving clinical stability by day 3 do no worse than patients receiving 8 or more days of antibiotics.

CRITIQUE

This guideline was created by a panel of pulmonologists, infectious disease specialists, general internists, and methodologists using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluations) approach to draft recommendations. Conflicts of interest were disclosed by all panel members according to the ATS and IDSA policies, and ultimately, two panel members recused themselves owing to conflicts of interest. The inclusion of a large number of RCTs, observational studies, and meta-analyses provides for good generalizability of the guideline published by this group.

Equal support was given in the guideline to all ß-lactams listed, including ampicillin/sulbactam, cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, and ceftaroline, regardless of MRSA risk factors. As the authors explicitly state in the guideline, one of the major reasons for abandoning the HCAP classification was to correct the overuse of anti-MRSA and antipseudomonal therapy.3 It is surprising, then, that the authors would include ceftaroline, a broad-spectrum cephalosporin that covers MRSA, as first-line therapy for patients without risk factors for MRSA.

The guideline also supported the use of a respiratory fluoroquinolone or a ß-lactam with macrolide equally. Although most RCTs have found equal efficacy between these two regimens,4 there is growing concern about the safety of fluoroquinolones.5 While the authors do encourage clinicians to consider these side effects in the main body of the text, a stronger statement could have been made more prominently to warn clinicians of safety concerns with fluoroquinolones.

Finally, while monotherapy with a ß-lactam was supported for the treatment of nonsevere outpatient CAP, it was not included in the recommendations for the treatment of hospitalized patients. There is conflicting data on this topic. One RCT failed to show noninferiority of monotherapy, but this was most pronounced among patients with severe pneumonia (PSI category IV) or cases with proven atypical infections.6 Another RCT found monotherapy to be noninferior to combination therapy for hospitalized patients not admitted to the ICU.7 There is also evidence suggesting that many patients hospitalized with pneumonia have viral rather than bacterial infections,8 which brings into question the need for antibiotics in this subset entirely. When these findings are considered from a stewardship perspective and patient safety profile, monotherapy with a ß-lactam for hospitalized patients without severe pneumonia could have been considered.

AREAS IN NEED OF FUTURE STUDY

Future research should track the effects of this guideline’s recommendation to narrow empiric therapy on patients empirically treated for MRSA or P aeruginosa infection once sputum and blood cultures are negative, particularly with respect to reduction of time on broad spectrum antimicrobials and clinical outcomes. Similarly, better definitions of which patients require empiric MRSA and P aeruginosa antimicrobial coverage are needed. Ideally, further research will facilitate rapid, cost-effective, and individualized therapy, particularly with growing concerns for antimicrobial resistance and safety.

Disclosures

The authors have no relevant financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Ramirez JA, Wiemken TL, Peyrani P, et al. Adults hospitalized with pneumonia in the United States: incidence, epidemiology, and mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(11):1806-1812. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cix647

2. Xu J, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Bastian BA. Deaths: final data for 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2016;64(2):1-119.

3. Jones BE, Jones MM, Huttner B, et al. Trends in antibiotic use and nosocomial pathogens in hospitalized veterans with pneumonia at 128 medical centers, 2006-2010. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(9):1403-1410. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/civ629

4. Fogarty C, Siami G, Kohler R, et al. Multicenter, open-label, randomized study to compare the safety and efficacy of levofloxacin versus ceftriaxone sodium and erythromycin followed by clarithromycin and amoxicillin-clavulanate in the treatment of serious community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(Suppl 1):S16-S23.

5. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Fluoroquinolone antimicrobial drugs information. Accessed February 4, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/ucm346750.htm

6. Garin N, Genné D, Carballo S, et al. ß-Lactam monotherapy vs ß-lactam-macrolide combination treatment in moderately severe community-acquired pneumonia: a randomized noninferiority trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(12):1894-1901. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4887

7. Postma DF, van Werkhoven CH, van Elden LJ, et al. Antibiotic treatment strategies for community-acquired pneumonia in adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(14):1312-1323. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1406330

8. Jain S, Self WH, Wunderink RG, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(5):415-427. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1500245

9. Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia: an official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(7):e45-e67. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201908-1581st

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is the second most common cause of hospitalization in the United States, with over 1.5 million unique hospitalizations annually.1 CAP is also the most common infectious cause of death in US adults.2 The 2019 CAP guideline from the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) provides recommendations on the diagnosis and management of CAP. The guideline provides 16 recommendations, which we have consolidated to highlight practice changing updates in diagnostic testing, risk stratification, and treatment.

KEY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE HOSPITALIST

Diagnostic Testing

Recommendation 1. In patients with CAP, routine blood cultures, sputum cultures, and urinary antigen tests are not routinely recommended unless severe CAP (Table), history of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and/or Pseudomonas infection, or prior hospitalization for which intravenous antibiotics were administered. (Strong recommendation; very low quality of evidence)

The guideline emphasizes that the diagnostic yield of blood/sputum cultures and urinary antigen testing is low. Additionally, high-quality data showing improved clinical outcomes with routine testing of blood cultures and urinary antigens are lacking. Instead, the guideline suggests obtaining blood cultures, urinary antigens, and sputum gram stain and culture only for patients with severe CAP and those being treated for or having prior infection with MRSA or P aeruginosa. They recommend narrowing therapy as appropriate if cultures are negative for either of these two organisms or previous hospitalization with intravenous antibiotics.

Risk Stratification

Recommendation 2. In patients with CAP, Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) or CURB-65 (tool based on confusion, urea level, respiratory rate, blood pressure, and age 65 years or older) scores should not be used to determine general medical ward vs intensive care unit care (ICU). (Strong recommendation; low quality of evidence)

The PSI and CURB-65 scores are not validated to determine location of hospital care. Multiple prognostic models have been studied to predict the need for ICU-level care including SMART-COP (systolic blood pressure, multilobar chest radiography involvement, albumin level, respiratory rate, tachycardia, confusion, oxygenation, and arterial pH), SCAPA (Study of Community Acquired Pneumonia Aetiology), and the ATS/IDSA criteria (Table). The positive and negative likelihood ratios for needing ICU admission in CAP with either one major or three or more minor ATS/IDSA criteria are 3.28 and 0.21, respectively.

Treatment

Recommendation 3a. In patients with nonsevere CAP and no risk factors for MRSA or Pseudomonas infection, empiric treatment with a ß-lactam plus macrolide or monotherapy with fluoroquinolones is recommended. (Strong recommendation; high quality of evidence)

Recommendation 3b. In patients with severe CAP and no risk factors for MRSA or Pseudomonas infection, empiric treatment with a ß-lactam plus either a macrolide or fluoroquinolone is recommended. (Strong recommendation; low to moderate quality of evidence)

Microbiologic risk assessment is critical. Risk factors for MRSA or P aeruginosa pneumonia include isolation of these agents in culture and recent hospitalization with receipt of parenteral antibiotics. ß-Lactam monotherapy is not recommended because previous randomized clinical trials (RCTs) demonstrated inferiority of ß-lactam monotherapy to combination therapy for resolution of CAP. The recommended combination therapy for patients with severe CAP without risk factors for MRSA or P aeruginosa infection is a ß-lactam plus either a macrolide or a respiratory fluoroquinolone.

Recommendation 4. In patients with suspected aspiration pneumonia, additional anaerobic coverage is not routinely recommended. (Conditional recommendation; very low quality of evidence)

Aspiration often causes a self-limited pneumonitis that will resolve in 24 to 48 hours with supportive care. Use of additional anaerobic coverage in these patients increases risk for complications (eg, Clostridioides difficile infection) without improving outcomes.

Recommendation 5. In patients with nonsevere CAP, corticosteroids are not routinely recommended. (Conditional recommendation; moderate quality of evidence)

There is no direct evidence that steroids reduce mortality or organ failure in nonsevere CAP. Additionally, the use of steroids in CAP can come with considerable risks (eg, secondary infection, hyperglycemia).

Recommendation 6. In hospitalized patients with CAP, empiric coverage for MRSA or P aeruginosa should be limited to patients meeting specific criteria. (Strong recommendation; moderate quality of evidence)

The guideline highlights the current overuse of extended spectrum antibiotics in patients meeting the previous definition of healthcare-associated pneumonia (HCAP). HCAP was defined by the presence of new chest x-ray infiltrates in patients with various exposures to healthcare settings (eg, chronic dialysis, infusion centers, emergency rooms). Antimicrobial therapy covering MRSA or P aeruginosa should be reserved for patients at risk for MRSA or P aeruginosa infection unless microbiologic testing is negative. Empiric antibiotic selection should incorporate local resistance patterns guided by hospital antibiograms.

Recommendation 7. In adults with CAP, antibiotics should be continued for no less than 5 days with documented clinical stability. (Strong recommendation; moderate quality of evidence)

Hospitalists often determine the length of antibiotic therapy for CAP. Recent studies show extended antibiotic treatment for pneumonia increases risk for adverse events without improving outcomes. Studies also demonstrate patients who receive 5 days of antibiotics total after achieving clinical stability by day 3 do no worse than patients receiving 8 or more days of antibiotics.

CRITIQUE

This guideline was created by a panel of pulmonologists, infectious disease specialists, general internists, and methodologists using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluations) approach to draft recommendations. Conflicts of interest were disclosed by all panel members according to the ATS and IDSA policies, and ultimately, two panel members recused themselves owing to conflicts of interest. The inclusion of a large number of RCTs, observational studies, and meta-analyses provides for good generalizability of the guideline published by this group.

Equal support was given in the guideline to all ß-lactams listed, including ampicillin/sulbactam, cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, and ceftaroline, regardless of MRSA risk factors. As the authors explicitly state in the guideline, one of the major reasons for abandoning the HCAP classification was to correct the overuse of anti-MRSA and antipseudomonal therapy.3 It is surprising, then, that the authors would include ceftaroline, a broad-spectrum cephalosporin that covers MRSA, as first-line therapy for patients without risk factors for MRSA.

The guideline also supported the use of a respiratory fluoroquinolone or a ß-lactam with macrolide equally. Although most RCTs have found equal efficacy between these two regimens,4 there is growing concern about the safety of fluoroquinolones.5 While the authors do encourage clinicians to consider these side effects in the main body of the text, a stronger statement could have been made more prominently to warn clinicians of safety concerns with fluoroquinolones.

Finally, while monotherapy with a ß-lactam was supported for the treatment of nonsevere outpatient CAP, it was not included in the recommendations for the treatment of hospitalized patients. There is conflicting data on this topic. One RCT failed to show noninferiority of monotherapy, but this was most pronounced among patients with severe pneumonia (PSI category IV) or cases with proven atypical infections.6 Another RCT found monotherapy to be noninferior to combination therapy for hospitalized patients not admitted to the ICU.7 There is also evidence suggesting that many patients hospitalized with pneumonia have viral rather than bacterial infections,8 which brings into question the need for antibiotics in this subset entirely. When these findings are considered from a stewardship perspective and patient safety profile, monotherapy with a ß-lactam for hospitalized patients without severe pneumonia could have been considered.

AREAS IN NEED OF FUTURE STUDY

Future research should track the effects of this guideline’s recommendation to narrow empiric therapy on patients empirically treated for MRSA or P aeruginosa infection once sputum and blood cultures are negative, particularly with respect to reduction of time on broad spectrum antimicrobials and clinical outcomes. Similarly, better definitions of which patients require empiric MRSA and P aeruginosa antimicrobial coverage are needed. Ideally, further research will facilitate rapid, cost-effective, and individualized therapy, particularly with growing concerns for antimicrobial resistance and safety.

Disclosures

The authors have no relevant financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is the second most common cause of hospitalization in the United States, with over 1.5 million unique hospitalizations annually.1 CAP is also the most common infectious cause of death in US adults.2 The 2019 CAP guideline from the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) provides recommendations on the diagnosis and management of CAP. The guideline provides 16 recommendations, which we have consolidated to highlight practice changing updates in diagnostic testing, risk stratification, and treatment.

KEY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE HOSPITALIST

Diagnostic Testing

Recommendation 1. In patients with CAP, routine blood cultures, sputum cultures, and urinary antigen tests are not routinely recommended unless severe CAP (Table), history of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and/or Pseudomonas infection, or prior hospitalization for which intravenous antibiotics were administered. (Strong recommendation; very low quality of evidence)

The guideline emphasizes that the diagnostic yield of blood/sputum cultures and urinary antigen testing is low. Additionally, high-quality data showing improved clinical outcomes with routine testing of blood cultures and urinary antigens are lacking. Instead, the guideline suggests obtaining blood cultures, urinary antigens, and sputum gram stain and culture only for patients with severe CAP and those being treated for or having prior infection with MRSA or P aeruginosa. They recommend narrowing therapy as appropriate if cultures are negative for either of these two organisms or previous hospitalization with intravenous antibiotics.

Risk Stratification

Recommendation 2. In patients with CAP, Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) or CURB-65 (tool based on confusion, urea level, respiratory rate, blood pressure, and age 65 years or older) scores should not be used to determine general medical ward vs intensive care unit care (ICU). (Strong recommendation; low quality of evidence)

The PSI and CURB-65 scores are not validated to determine location of hospital care. Multiple prognostic models have been studied to predict the need for ICU-level care including SMART-COP (systolic blood pressure, multilobar chest radiography involvement, albumin level, respiratory rate, tachycardia, confusion, oxygenation, and arterial pH), SCAPA (Study of Community Acquired Pneumonia Aetiology), and the ATS/IDSA criteria (Table). The positive and negative likelihood ratios for needing ICU admission in CAP with either one major or three or more minor ATS/IDSA criteria are 3.28 and 0.21, respectively.

Treatment

Recommendation 3a. In patients with nonsevere CAP and no risk factors for MRSA or Pseudomonas infection, empiric treatment with a ß-lactam plus macrolide or monotherapy with fluoroquinolones is recommended. (Strong recommendation; high quality of evidence)

Recommendation 3b. In patients with severe CAP and no risk factors for MRSA or Pseudomonas infection, empiric treatment with a ß-lactam plus either a macrolide or fluoroquinolone is recommended. (Strong recommendation; low to moderate quality of evidence)

Microbiologic risk assessment is critical. Risk factors for MRSA or P aeruginosa pneumonia include isolation of these agents in culture and recent hospitalization with receipt of parenteral antibiotics. ß-Lactam monotherapy is not recommended because previous randomized clinical trials (RCTs) demonstrated inferiority of ß-lactam monotherapy to combination therapy for resolution of CAP. The recommended combination therapy for patients with severe CAP without risk factors for MRSA or P aeruginosa infection is a ß-lactam plus either a macrolide or a respiratory fluoroquinolone.

Recommendation 4. In patients with suspected aspiration pneumonia, additional anaerobic coverage is not routinely recommended. (Conditional recommendation; very low quality of evidence)

Aspiration often causes a self-limited pneumonitis that will resolve in 24 to 48 hours with supportive care. Use of additional anaerobic coverage in these patients increases risk for complications (eg, Clostridioides difficile infection) without improving outcomes.

Recommendation 5. In patients with nonsevere CAP, corticosteroids are not routinely recommended. (Conditional recommendation; moderate quality of evidence)

There is no direct evidence that steroids reduce mortality or organ failure in nonsevere CAP. Additionally, the use of steroids in CAP can come with considerable risks (eg, secondary infection, hyperglycemia).

Recommendation 6. In hospitalized patients with CAP, empiric coverage for MRSA or P aeruginosa should be limited to patients meeting specific criteria. (Strong recommendation; moderate quality of evidence)

The guideline highlights the current overuse of extended spectrum antibiotics in patients meeting the previous definition of healthcare-associated pneumonia (HCAP). HCAP was defined by the presence of new chest x-ray infiltrates in patients with various exposures to healthcare settings (eg, chronic dialysis, infusion centers, emergency rooms). Antimicrobial therapy covering MRSA or P aeruginosa should be reserved for patients at risk for MRSA or P aeruginosa infection unless microbiologic testing is negative. Empiric antibiotic selection should incorporate local resistance patterns guided by hospital antibiograms.

Recommendation 7. In adults with CAP, antibiotics should be continued for no less than 5 days with documented clinical stability. (Strong recommendation; moderate quality of evidence)

Hospitalists often determine the length of antibiotic therapy for CAP. Recent studies show extended antibiotic treatment for pneumonia increases risk for adverse events without improving outcomes. Studies also demonstrate patients who receive 5 days of antibiotics total after achieving clinical stability by day 3 do no worse than patients receiving 8 or more days of antibiotics.

CRITIQUE

This guideline was created by a panel of pulmonologists, infectious disease specialists, general internists, and methodologists using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluations) approach to draft recommendations. Conflicts of interest were disclosed by all panel members according to the ATS and IDSA policies, and ultimately, two panel members recused themselves owing to conflicts of interest. The inclusion of a large number of RCTs, observational studies, and meta-analyses provides for good generalizability of the guideline published by this group.

Equal support was given in the guideline to all ß-lactams listed, including ampicillin/sulbactam, cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, and ceftaroline, regardless of MRSA risk factors. As the authors explicitly state in the guideline, one of the major reasons for abandoning the HCAP classification was to correct the overuse of anti-MRSA and antipseudomonal therapy.3 It is surprising, then, that the authors would include ceftaroline, a broad-spectrum cephalosporin that covers MRSA, as first-line therapy for patients without risk factors for MRSA.

The guideline also supported the use of a respiratory fluoroquinolone or a ß-lactam with macrolide equally. Although most RCTs have found equal efficacy between these two regimens,4 there is growing concern about the safety of fluoroquinolones.5 While the authors do encourage clinicians to consider these side effects in the main body of the text, a stronger statement could have been made more prominently to warn clinicians of safety concerns with fluoroquinolones.

Finally, while monotherapy with a ß-lactam was supported for the treatment of nonsevere outpatient CAP, it was not included in the recommendations for the treatment of hospitalized patients. There is conflicting data on this topic. One RCT failed to show noninferiority of monotherapy, but this was most pronounced among patients with severe pneumonia (PSI category IV) or cases with proven atypical infections.6 Another RCT found monotherapy to be noninferior to combination therapy for hospitalized patients not admitted to the ICU.7 There is also evidence suggesting that many patients hospitalized with pneumonia have viral rather than bacterial infections,8 which brings into question the need for antibiotics in this subset entirely. When these findings are considered from a stewardship perspective and patient safety profile, monotherapy with a ß-lactam for hospitalized patients without severe pneumonia could have been considered.

AREAS IN NEED OF FUTURE STUDY

Future research should track the effects of this guideline’s recommendation to narrow empiric therapy on patients empirically treated for MRSA or P aeruginosa infection once sputum and blood cultures are negative, particularly with respect to reduction of time on broad spectrum antimicrobials and clinical outcomes. Similarly, better definitions of which patients require empiric MRSA and P aeruginosa antimicrobial coverage are needed. Ideally, further research will facilitate rapid, cost-effective, and individualized therapy, particularly with growing concerns for antimicrobial resistance and safety.

Disclosures

The authors have no relevant financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Ramirez JA, Wiemken TL, Peyrani P, et al. Adults hospitalized with pneumonia in the United States: incidence, epidemiology, and mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(11):1806-1812. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cix647

2. Xu J, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Bastian BA. Deaths: final data for 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2016;64(2):1-119.

3. Jones BE, Jones MM, Huttner B, et al. Trends in antibiotic use and nosocomial pathogens in hospitalized veterans with pneumonia at 128 medical centers, 2006-2010. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(9):1403-1410. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/civ629

4. Fogarty C, Siami G, Kohler R, et al. Multicenter, open-label, randomized study to compare the safety and efficacy of levofloxacin versus ceftriaxone sodium and erythromycin followed by clarithromycin and amoxicillin-clavulanate in the treatment of serious community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(Suppl 1):S16-S23.

5. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Fluoroquinolone antimicrobial drugs information. Accessed February 4, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/ucm346750.htm

6. Garin N, Genné D, Carballo S, et al. ß-Lactam monotherapy vs ß-lactam-macrolide combination treatment in moderately severe community-acquired pneumonia: a randomized noninferiority trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(12):1894-1901. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4887

7. Postma DF, van Werkhoven CH, van Elden LJ, et al. Antibiotic treatment strategies for community-acquired pneumonia in adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(14):1312-1323. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1406330

8. Jain S, Self WH, Wunderink RG, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(5):415-427. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1500245

9. Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia: an official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(7):e45-e67. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201908-1581st

1. Ramirez JA, Wiemken TL, Peyrani P, et al. Adults hospitalized with pneumonia in the United States: incidence, epidemiology, and mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(11):1806-1812. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cix647

2. Xu J, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Bastian BA. Deaths: final data for 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2016;64(2):1-119.

3. Jones BE, Jones MM, Huttner B, et al. Trends in antibiotic use and nosocomial pathogens in hospitalized veterans with pneumonia at 128 medical centers, 2006-2010. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(9):1403-1410. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/civ629

4. Fogarty C, Siami G, Kohler R, et al. Multicenter, open-label, randomized study to compare the safety and efficacy of levofloxacin versus ceftriaxone sodium and erythromycin followed by clarithromycin and amoxicillin-clavulanate in the treatment of serious community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(Suppl 1):S16-S23.

5. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Fluoroquinolone antimicrobial drugs information. Accessed February 4, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/ucm346750.htm

6. Garin N, Genné D, Carballo S, et al. ß-Lactam monotherapy vs ß-lactam-macrolide combination treatment in moderately severe community-acquired pneumonia: a randomized noninferiority trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(12):1894-1901. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4887

7. Postma DF, van Werkhoven CH, van Elden LJ, et al. Antibiotic treatment strategies for community-acquired pneumonia in adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(14):1312-1323. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1406330

8. Jain S, Self WH, Wunderink RG, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(5):415-427. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1500245

9. Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia: an official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(7):e45-e67. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201908-1581st

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine