User login

Leader Rounding for High Reliability and Improved Patient Safety

The hospital is altogether the most complex human organization ever devised. Peter Drucker 1

The ever-changing landscape of today’s increasingly complex health care system depends on implementing multifaceted, team-based methods of care delivery to provide safe, effective patient care.2 Critical to establishing and sustaining exceptionally safe, effective patient care is open, transparent communication among members of interprofessional teams with senior leaders.3 However, current evidence shows that poor communication among interprofessional health care teams and leadership is commonplace and a significant contributing factor to inefficiencies, medical errors, and poor outcomes.4 One strategy for improving communication is through the implementation of

We describe the importance of leader rounding for high reliability as an approach to improving patient safety. Based on a review of the literature, our experiences, and lessons learned, we offer recommendations for how health care organizations on the journey to high reliability can improve patient safety.

Rounding in health care is not new. In fact, rounding has been a strong principal practice globally for more than 2 decades.6 During this time, varied rounding approaches have emerged, oftentimes focused on areas of interest, such as patient care, environmental services, facilities management, and discharge planning.4,7 Variations also might involve the location of the rounds, such as a patient’s bedside, unit hallways, and conference rooms as well as the naming of rounds, such as interdisciplinary/multidisciplinary, teaching, and walkrounds.7-10

A different type of rounding that is characteristic of high reliability organizations (HROs) is leader rounding for high reliability. The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) formally launched its journey to becoming an

Leader rounding for high reliability includes regularly scheduled, structured visits, with interdisciplinary teams to discuss high reliability, safety, and improvement efforts. The specific aim of these particular rounds is for senior leaders to be visible where teams are located and learn from staff (especially those on the frontlines of care) about day-to-day challenges that may contribute to patient harm.12,13 Leader rounding for high reliability is also an important approach to improving leadership visibility across the organization, demonstrating a commitment to high reliability, and building trust and relationships with staff through open and honest dialogue. It is also an important approach to increasing leadership understanding of operational, clinical, nonclinical, patient experience issues, and concern related to safety.11 This opportunity enables leaders to provide and receive real-time feedback from staff.9,11 This experience also gives leaders an opportunity to reinforce

In preparation for implementing a leader rounding for high reliability process at the VABHS, we conducted an extensive literature review for peer-reviewed publications published between January 2015 and September 2022 regarding how other organizations implemented leader rounding. This search found a dearth of evidence as it specifically relates to leader rounding for high reliability. This motivated us to create a process for developing and implementing leader rounding for high reliability in pursuit of improving patient safety. With this objective in mind, we created and piloted a process in the fall of 2023. The first 3 months were focused on the medical center director rounding with other members of the executive leadership team to assess the feasibility and acceptability of the process. In December 2023, members of the executive leadership team began conducting leader rounding for high reliability separately. The following steps are based on the lessons we have gleaned from evolving evidence, our experiences, and developing and implementing an approach to leader rounding for high reliability.

ESTABLISH A PROCESS

Leader rounding for high reliability is performed by health care organization executive leadership, directors, managers, and supervisors. When properly conducted, increased levels of teamwork and more effective bidirectional communication take place, resulting in a united team motivated to improve patient safety.16,17 Important early steps for implementing leader rounding for high reliability include establishing a process and getting leadership buy-in. Purposeful attention to planning is critical as is understanding the organizational factors that might deter success. Establishing a process should consider facilitators and barriers to implementation, which can include high vs low leadership turnover, structured vs unstructured rounding, and time for rounding vs competing demands.18,19 We have learned that effective planning is important for ensuring that leadership teams are well prepared and ambitious about leader rounding for high reliability.

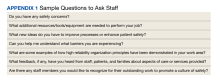

Leader rounding for high reliability involves brief 10-to-15-minute interactions with interdisciplinary teams, including frontline staff. For health care organizations beginning to implement this approach, having scripts or checklists accessible might be of help. If possible, the rounds should be scheduled in advance. This helps to avoid rounding in areas at their busiest times. When possible, leader rounding for high reliability should occur as planned. Canceling rounds sends the message that leader rounding for high reliability and the valuable interactions they support are a low priority. When conflicts arise, another leader should be sent to participate. Developing a list of questions in advance helps to underscore key messages to be shared as well as reinforce principles, practices, behaviors, and attitudes related to high reliability (Appendix 1).11

Finally, closing the loop is critical to the leader rounding process and to improve bidirectional communication. Closed-loop communication, following up on and/or closing out an area of discussion, not only promotes a shared understanding of information but has been found to improve patient safety.19 Effective leader rounding for high reliability includes summarizing issues and opportunities, deciding on a date for resolution for open action items, and identifying who is responsible for taking action. Senior leaders are not responsible for resolving all issues. If a team or manager of a work area can solve any issues identified, this should be encouraged and supported so accountability is maintained at the most appropriate level of the organization.

Instrumental to leader rounding for high reliability is establishing a cadence for when leaders will visit work areas.14 The most critical strategy, especially in times of change, is consistency in rounding.11 At the start of implementation, we decided on a biweekly cadence. Initially leaders visited areas of the organization within their respective reporting structure. Once this was established, leaders periodically round in areas outside their scope of responsibility. This affords leaders the opportunity to observe other areas of the organization. As noted, it is important for leaders to be flexible with the rounding process especially in areas where direct patient care is being provided.

Tracking

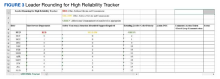

Developing a tracking tool also is important for an effective leader rounding process. This tool is used to document issues and concerns identified during the rounding process, assign accountability, track the status of items, and close the loop when completed. One of the most commonly reported hurdles to staff sharing information to promote a culture of safety is the lack of feedback on what actions were taken to address the concern or issue raised with leadership. Closed-loop communication is critical for keeping staff continually engaged in efforts to promote a culture of safety.20 We have found that a tracking tool helps to ensure that closed-loop communication takes place.

Various platforms can be used for tracking items and providing follow-up, including paper worksheets, spreadsheets, databases, or third party software (eg, SharePoint, TruthPoint Rounds, GetWell Rounds). The tracking tool should have a standardized approach for prioritizing issues.

The stoplight classification system uses color coding (Figure 3).21 Green represents a safe space where there are no or low safety risks and are easily addressed at the local level by the area manager with or without assistance from the leadership team rounding, such as staffing.22,23 The unit manager has control of the situation and a plan is actively being implemented. Yellow signifies that areas are at risk, but with increased vigilance, issues do not escalate to a crisis state.22,23 Yellow-coded issues require further investigation by the leadership team. The senior leader on the team designates a process as well as a person responsible for closing the loop with the area manager regarding the status of problem resolution. For example, if the unit manager mentioned previously needing help to find staff, the area manager would suggest or take steps to help the unit manager. The area manager is then responsible for updating the frontline staff. Red-coded issues are urgent, identifying a state of crisis or high risk. Red issues need to be immediately addressed but cannot be resolved during rounds. Senior leaders must evaluate and make decisions to mitigate the threat. A member of the leadership team is tasked with following up with the area manager, typically within 24 hours. A staffing crisis that requires executive leadership help with identifying additional resources would be coded red.

The area manager is responsible for closing the loop with frontline staff. As frontline staff became more comfortable with the process, we observed an upward trend in the number of reported issues. We are now starting to see a downward trend in concerns shared during rounding as managers and frontline staff feel empowered to address issues at the lowest level.

Measuring Impact

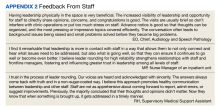

Measuring the impact is a critical step to determine the overall effectiveness of leader rounding for high reliability. It can be as simple as requesting candid feedback from frontline staff, supervisors, managers, and service chiefs. For example, 4 months into the implementation process, the VABHS administered a brief staff survey on the overall process, perceived benefits, and challenges experienced (Appendix 2). Potential measures include the counts of leaders rounding, total rounds, rounds cancelled, and staff members actively participating in rounds. Outcomes that can be measured include issues identified, addressed, elevated, and remaining open; number of extended workdays due to rounds; staff staying overtime; and delays in patient care activities.23 Other measures to consider are the effects of rounding on staff as well as patient/family satisfaction, increase in the number of errors and near-miss events reported per month in a health care organizations’ patient safety reporting system, and increased engagement of staff members in continuous process improvement activities. Since the inception of leader rounding for high reliability, the VABHS has seen a slight increase in the number of events entered in the patient safety reporting system. Other factors that may have contributed to this change, including encouragement of reporting at safety forums, and tiered safety huddles.

DISCUSSION

This initiative involved the development and implementation of a leader rounding for high reliability process at the VABHS with the overarching goal of ensuring efficient communication exists among members of the health care team for delivering safe, quality patient care. The initiative was well received by staff from senior leadership to frontline personnel and promoted significant interest in efforts to improve safety across the health care system.

The pilot phase permitted us to examine the feasibility and acceptability of the process to leadership as well as frontline staff. The insight gained and lessons learned through the implementation process helped us make revisions where needed and develop the tools to ensure success. In the second phase of implementation, which commenced in December 2023, each executive leadership team member began leader rounding for high reliability with their respective department service chiefs. Throughout this phase, feedback will be sought on the overall process, perceived benefits, and challenges experienced to make improvements or changes as needed. We also will continue to monitor the number of events entered in the patient safety reporting system. Future efforts will focus on developing a robust program of evaluation to explore the impact of the program on patient/family satisfaction as well as safety outcomes.

Limitations

Developing and implementing a process for leader rounding for high reliability was undertaken to support the VABHS and VHA journey to high reliability. Other health care organizations and integrated systems might identify different processes for improving patient safety and to support their journey to becoming an HRO.

CONCLUSIONS

The importance of leader rounding for high reliability to improve patient safety cannot be emphasized enough in a time where health care systems have become increasingly complex. Health care is a complex adaptive system that requires effective, bidirectional communication and collaboration among all disciplines. One of the most useful, evidence-based strategies for promoting this communication and collaboration to improve a culture of safety is leader rounding for high reliability.

1. Drucker PF. They’re not employees, they’re people. Accessed November 15, 2023. https://hbr.org/2002/02/theyre-not-employees-theyre-people

2. Adams HA, Feudale RM. Implementation of a structured rounding tool for interprofessional care team rounds to improve communication and collaboration in patient care. Pediatr Nurs. 2018;44(5):229-233, 246.

3. Witz I, Lucchese S, Valenzano TJ, et al: Perceptions on implementation of a new standardized reporting tool to support structured morning rounds: recommendations for interprofessional teams and healthcare leaders. J Med Radiat Sci. 2022;53(4):S85-S92. doi:10.1016/j.jmir.2022.06.006

4. Blakeney EA, Chu F, White AA, et al. A scoping review of new implementations of interprofessional bedside rounding models to improve teamwork, care, and outcomes in hospitals. J Interprof Care. 2021;10:1-16 [Online ahead of print.] doi:10.1080/13561820.2021.1980379

5. Agency for Research and Healthcare Quality. High reliability. Accessed December 4, 2023. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primer/high-reliability

6. Hedenstrom M, Harrilson A, Heath M, Dyass S. “What’s old is new again”: innovative health care leader rounding—a strategy to foster connection. Nurse Lead. 2022;20(4):366-370.

7. Walton V, Hogden A, Long JC, Johnson JK, Greenfield D. How do interprofessional healthcare teams perceive the benefits and challenges of interdisciplinary ward rounds. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2019;12:1023-1032. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S226330

8. Walton V, Hogden A, Johnson J, Greenfield D. Ward rounds, participants, roles and perceptions: literature review. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2016;29(4):364-379. doi:10.1108/IJHCQA-04-2015-0053

9. Sexton JB, Adair KC, Leonard MW, et al. Providing feedback following leadership walkrounds is associated with better patient safety culture, higher employee engagement and lower burnout. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27(4):261-270. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2016-006399

10. Sexton JB, Adair KC, Profit J, et al. Safety culture and workforce well-being associations with positive leadership walkrounds. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2021;47(7):403-411. doi:10.1016/j.jcjq.2021.04.001

11. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. Leader’s guide to foundational high reliability organization (HRO) practices. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://dvagov.sharepoint.com/sites/OHT-PMO/high-reliability/Pages/default.aspx

12. Zajac S, Woods A, Tannenbaum S, Salas E, Hollada CL. Overcoming challenges to teamwork in healthcare: a team effectiveness framework and evidence-based guidance. Front Commun. 2021;6:1-20. doi:10.3389/fcomm.2021.606445

13. Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA’s Vision for a High Reliability Organization. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/forum/summer20/default.cfm?ForumMenu=summer20-1

14. Merchant NB, O’Neal J, Dealino-Perez C, Xiang J, Montoya A Jr, Murray JS. A high-reliability organization mindset. Am J Med Qual. 2022;37(6):504-510. doi:10.1097/JMQ.0000000000000086

15. Verhaegh KJ, Seller-Boersma A, Simons R, et al. An exploratory study of healthcare professionals’ perceptions of interprofessional communication and collaboration. J Interprof Care. 2017;31(3):397-400. doi:10.1080/13561820.2017.1289158

16. Winter M, Tjiong L. HCAHPS Series Part 2: Does purposeful leader rounding make a difference? Nurs Manag. 2015;46(2):26-32. doi:10.1097/01.NUMA.0000460034.25697.06

17. Beaird G, Baernholdt M, White KR. Perceptions of interdisciplinary rounding practices. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(7-8):1141-1150. doi:10.1111/jocn.15161

18. Hendricks S, LaMothe VJ, Kara A. Facilitators and barriers for interprofessional rounding: a qualitative study. Clin Nurse Spec. 2017;31(4):219-228. doi:10.1097/NUR.0000000000000310

19. Diaz MCG, Dawson K. Impact of simulation-based closed-loop communication training on medical errors in a pediatric emergency department. Am J Med Qual. 2020;35(6):474-478. doi:10.1177/1062860620912480

20. Williams S, Fiumara K, Kachalia A, Desai S. Closing the loop with ambulatory staff on safety reports. Jt Comm J Qual Saf. 2020;46(1):44-50. doi:10.1016/j.jcjq.2019.09.009

21. Parbhoo A, Batte J. Traffic lights: putting a stop to unsafe patient transfers. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2015;4(1):u204799.w2079. doi:10.1136/bmjquality.u204799.w2079

22. Prineas S, Culwick M, Endlich Y. A proposed system for standardization of colour-coding stages of escalating criticality in clinical incidents. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2021;34(6):752-760. doi:10.1097/ACO.0000000000001071.

23. Merchant NB, O’Neal J, Montoya A, Cox GR, Murray JS. Creating a process for the implementation of tiered huddles in a Veterans Affairs medical center. Mil Med. 2023;188(5-6):901-906. doi:10.1093/milmed/usac073

The hospital is altogether the most complex human organization ever devised. Peter Drucker 1

The ever-changing landscape of today’s increasingly complex health care system depends on implementing multifaceted, team-based methods of care delivery to provide safe, effective patient care.2 Critical to establishing and sustaining exceptionally safe, effective patient care is open, transparent communication among members of interprofessional teams with senior leaders.3 However, current evidence shows that poor communication among interprofessional health care teams and leadership is commonplace and a significant contributing factor to inefficiencies, medical errors, and poor outcomes.4 One strategy for improving communication is through the implementation of

We describe the importance of leader rounding for high reliability as an approach to improving patient safety. Based on a review of the literature, our experiences, and lessons learned, we offer recommendations for how health care organizations on the journey to high reliability can improve patient safety.

Rounding in health care is not new. In fact, rounding has been a strong principal practice globally for more than 2 decades.6 During this time, varied rounding approaches have emerged, oftentimes focused on areas of interest, such as patient care, environmental services, facilities management, and discharge planning.4,7 Variations also might involve the location of the rounds, such as a patient’s bedside, unit hallways, and conference rooms as well as the naming of rounds, such as interdisciplinary/multidisciplinary, teaching, and walkrounds.7-10

A different type of rounding that is characteristic of high reliability organizations (HROs) is leader rounding for high reliability. The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) formally launched its journey to becoming an

Leader rounding for high reliability includes regularly scheduled, structured visits, with interdisciplinary teams to discuss high reliability, safety, and improvement efforts. The specific aim of these particular rounds is for senior leaders to be visible where teams are located and learn from staff (especially those on the frontlines of care) about day-to-day challenges that may contribute to patient harm.12,13 Leader rounding for high reliability is also an important approach to improving leadership visibility across the organization, demonstrating a commitment to high reliability, and building trust and relationships with staff through open and honest dialogue. It is also an important approach to increasing leadership understanding of operational, clinical, nonclinical, patient experience issues, and concern related to safety.11 This opportunity enables leaders to provide and receive real-time feedback from staff.9,11 This experience also gives leaders an opportunity to reinforce

In preparation for implementing a leader rounding for high reliability process at the VABHS, we conducted an extensive literature review for peer-reviewed publications published between January 2015 and September 2022 regarding how other organizations implemented leader rounding. This search found a dearth of evidence as it specifically relates to leader rounding for high reliability. This motivated us to create a process for developing and implementing leader rounding for high reliability in pursuit of improving patient safety. With this objective in mind, we created and piloted a process in the fall of 2023. The first 3 months were focused on the medical center director rounding with other members of the executive leadership team to assess the feasibility and acceptability of the process. In December 2023, members of the executive leadership team began conducting leader rounding for high reliability separately. The following steps are based on the lessons we have gleaned from evolving evidence, our experiences, and developing and implementing an approach to leader rounding for high reliability.

ESTABLISH A PROCESS

Leader rounding for high reliability is performed by health care organization executive leadership, directors, managers, and supervisors. When properly conducted, increased levels of teamwork and more effective bidirectional communication take place, resulting in a united team motivated to improve patient safety.16,17 Important early steps for implementing leader rounding for high reliability include establishing a process and getting leadership buy-in. Purposeful attention to planning is critical as is understanding the organizational factors that might deter success. Establishing a process should consider facilitators and barriers to implementation, which can include high vs low leadership turnover, structured vs unstructured rounding, and time for rounding vs competing demands.18,19 We have learned that effective planning is important for ensuring that leadership teams are well prepared and ambitious about leader rounding for high reliability.

Leader rounding for high reliability involves brief 10-to-15-minute interactions with interdisciplinary teams, including frontline staff. For health care organizations beginning to implement this approach, having scripts or checklists accessible might be of help. If possible, the rounds should be scheduled in advance. This helps to avoid rounding in areas at their busiest times. When possible, leader rounding for high reliability should occur as planned. Canceling rounds sends the message that leader rounding for high reliability and the valuable interactions they support are a low priority. When conflicts arise, another leader should be sent to participate. Developing a list of questions in advance helps to underscore key messages to be shared as well as reinforce principles, practices, behaviors, and attitudes related to high reliability (Appendix 1).11

Finally, closing the loop is critical to the leader rounding process and to improve bidirectional communication. Closed-loop communication, following up on and/or closing out an area of discussion, not only promotes a shared understanding of information but has been found to improve patient safety.19 Effective leader rounding for high reliability includes summarizing issues and opportunities, deciding on a date for resolution for open action items, and identifying who is responsible for taking action. Senior leaders are not responsible for resolving all issues. If a team or manager of a work area can solve any issues identified, this should be encouraged and supported so accountability is maintained at the most appropriate level of the organization.

Instrumental to leader rounding for high reliability is establishing a cadence for when leaders will visit work areas.14 The most critical strategy, especially in times of change, is consistency in rounding.11 At the start of implementation, we decided on a biweekly cadence. Initially leaders visited areas of the organization within their respective reporting structure. Once this was established, leaders periodically round in areas outside their scope of responsibility. This affords leaders the opportunity to observe other areas of the organization. As noted, it is important for leaders to be flexible with the rounding process especially in areas where direct patient care is being provided.

Tracking

Developing a tracking tool also is important for an effective leader rounding process. This tool is used to document issues and concerns identified during the rounding process, assign accountability, track the status of items, and close the loop when completed. One of the most commonly reported hurdles to staff sharing information to promote a culture of safety is the lack of feedback on what actions were taken to address the concern or issue raised with leadership. Closed-loop communication is critical for keeping staff continually engaged in efforts to promote a culture of safety.20 We have found that a tracking tool helps to ensure that closed-loop communication takes place.

Various platforms can be used for tracking items and providing follow-up, including paper worksheets, spreadsheets, databases, or third party software (eg, SharePoint, TruthPoint Rounds, GetWell Rounds). The tracking tool should have a standardized approach for prioritizing issues.

The stoplight classification system uses color coding (Figure 3).21 Green represents a safe space where there are no or low safety risks and are easily addressed at the local level by the area manager with or without assistance from the leadership team rounding, such as staffing.22,23 The unit manager has control of the situation and a plan is actively being implemented. Yellow signifies that areas are at risk, but with increased vigilance, issues do not escalate to a crisis state.22,23 Yellow-coded issues require further investigation by the leadership team. The senior leader on the team designates a process as well as a person responsible for closing the loop with the area manager regarding the status of problem resolution. For example, if the unit manager mentioned previously needing help to find staff, the area manager would suggest or take steps to help the unit manager. The area manager is then responsible for updating the frontline staff. Red-coded issues are urgent, identifying a state of crisis or high risk. Red issues need to be immediately addressed but cannot be resolved during rounds. Senior leaders must evaluate and make decisions to mitigate the threat. A member of the leadership team is tasked with following up with the area manager, typically within 24 hours. A staffing crisis that requires executive leadership help with identifying additional resources would be coded red.

The area manager is responsible for closing the loop with frontline staff. As frontline staff became more comfortable with the process, we observed an upward trend in the number of reported issues. We are now starting to see a downward trend in concerns shared during rounding as managers and frontline staff feel empowered to address issues at the lowest level.

Measuring Impact

Measuring the impact is a critical step to determine the overall effectiveness of leader rounding for high reliability. It can be as simple as requesting candid feedback from frontline staff, supervisors, managers, and service chiefs. For example, 4 months into the implementation process, the VABHS administered a brief staff survey on the overall process, perceived benefits, and challenges experienced (Appendix 2). Potential measures include the counts of leaders rounding, total rounds, rounds cancelled, and staff members actively participating in rounds. Outcomes that can be measured include issues identified, addressed, elevated, and remaining open; number of extended workdays due to rounds; staff staying overtime; and delays in patient care activities.23 Other measures to consider are the effects of rounding on staff as well as patient/family satisfaction, increase in the number of errors and near-miss events reported per month in a health care organizations’ patient safety reporting system, and increased engagement of staff members in continuous process improvement activities. Since the inception of leader rounding for high reliability, the VABHS has seen a slight increase in the number of events entered in the patient safety reporting system. Other factors that may have contributed to this change, including encouragement of reporting at safety forums, and tiered safety huddles.

DISCUSSION

This initiative involved the development and implementation of a leader rounding for high reliability process at the VABHS with the overarching goal of ensuring efficient communication exists among members of the health care team for delivering safe, quality patient care. The initiative was well received by staff from senior leadership to frontline personnel and promoted significant interest in efforts to improve safety across the health care system.

The pilot phase permitted us to examine the feasibility and acceptability of the process to leadership as well as frontline staff. The insight gained and lessons learned through the implementation process helped us make revisions where needed and develop the tools to ensure success. In the second phase of implementation, which commenced in December 2023, each executive leadership team member began leader rounding for high reliability with their respective department service chiefs. Throughout this phase, feedback will be sought on the overall process, perceived benefits, and challenges experienced to make improvements or changes as needed. We also will continue to monitor the number of events entered in the patient safety reporting system. Future efforts will focus on developing a robust program of evaluation to explore the impact of the program on patient/family satisfaction as well as safety outcomes.

Limitations

Developing and implementing a process for leader rounding for high reliability was undertaken to support the VABHS and VHA journey to high reliability. Other health care organizations and integrated systems might identify different processes for improving patient safety and to support their journey to becoming an HRO.

CONCLUSIONS

The importance of leader rounding for high reliability to improve patient safety cannot be emphasized enough in a time where health care systems have become increasingly complex. Health care is a complex adaptive system that requires effective, bidirectional communication and collaboration among all disciplines. One of the most useful, evidence-based strategies for promoting this communication and collaboration to improve a culture of safety is leader rounding for high reliability.

The hospital is altogether the most complex human organization ever devised. Peter Drucker 1

The ever-changing landscape of today’s increasingly complex health care system depends on implementing multifaceted, team-based methods of care delivery to provide safe, effective patient care.2 Critical to establishing and sustaining exceptionally safe, effective patient care is open, transparent communication among members of interprofessional teams with senior leaders.3 However, current evidence shows that poor communication among interprofessional health care teams and leadership is commonplace and a significant contributing factor to inefficiencies, medical errors, and poor outcomes.4 One strategy for improving communication is through the implementation of

We describe the importance of leader rounding for high reliability as an approach to improving patient safety. Based on a review of the literature, our experiences, and lessons learned, we offer recommendations for how health care organizations on the journey to high reliability can improve patient safety.

Rounding in health care is not new. In fact, rounding has been a strong principal practice globally for more than 2 decades.6 During this time, varied rounding approaches have emerged, oftentimes focused on areas of interest, such as patient care, environmental services, facilities management, and discharge planning.4,7 Variations also might involve the location of the rounds, such as a patient’s bedside, unit hallways, and conference rooms as well as the naming of rounds, such as interdisciplinary/multidisciplinary, teaching, and walkrounds.7-10

A different type of rounding that is characteristic of high reliability organizations (HROs) is leader rounding for high reliability. The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) formally launched its journey to becoming an

Leader rounding for high reliability includes regularly scheduled, structured visits, with interdisciplinary teams to discuss high reliability, safety, and improvement efforts. The specific aim of these particular rounds is for senior leaders to be visible where teams are located and learn from staff (especially those on the frontlines of care) about day-to-day challenges that may contribute to patient harm.12,13 Leader rounding for high reliability is also an important approach to improving leadership visibility across the organization, demonstrating a commitment to high reliability, and building trust and relationships with staff through open and honest dialogue. It is also an important approach to increasing leadership understanding of operational, clinical, nonclinical, patient experience issues, and concern related to safety.11 This opportunity enables leaders to provide and receive real-time feedback from staff.9,11 This experience also gives leaders an opportunity to reinforce

In preparation for implementing a leader rounding for high reliability process at the VABHS, we conducted an extensive literature review for peer-reviewed publications published between January 2015 and September 2022 regarding how other organizations implemented leader rounding. This search found a dearth of evidence as it specifically relates to leader rounding for high reliability. This motivated us to create a process for developing and implementing leader rounding for high reliability in pursuit of improving patient safety. With this objective in mind, we created and piloted a process in the fall of 2023. The first 3 months were focused on the medical center director rounding with other members of the executive leadership team to assess the feasibility and acceptability of the process. In December 2023, members of the executive leadership team began conducting leader rounding for high reliability separately. The following steps are based on the lessons we have gleaned from evolving evidence, our experiences, and developing and implementing an approach to leader rounding for high reliability.

ESTABLISH A PROCESS

Leader rounding for high reliability is performed by health care organization executive leadership, directors, managers, and supervisors. When properly conducted, increased levels of teamwork and more effective bidirectional communication take place, resulting in a united team motivated to improve patient safety.16,17 Important early steps for implementing leader rounding for high reliability include establishing a process and getting leadership buy-in. Purposeful attention to planning is critical as is understanding the organizational factors that might deter success. Establishing a process should consider facilitators and barriers to implementation, which can include high vs low leadership turnover, structured vs unstructured rounding, and time for rounding vs competing demands.18,19 We have learned that effective planning is important for ensuring that leadership teams are well prepared and ambitious about leader rounding for high reliability.

Leader rounding for high reliability involves brief 10-to-15-minute interactions with interdisciplinary teams, including frontline staff. For health care organizations beginning to implement this approach, having scripts or checklists accessible might be of help. If possible, the rounds should be scheduled in advance. This helps to avoid rounding in areas at their busiest times. When possible, leader rounding for high reliability should occur as planned. Canceling rounds sends the message that leader rounding for high reliability and the valuable interactions they support are a low priority. When conflicts arise, another leader should be sent to participate. Developing a list of questions in advance helps to underscore key messages to be shared as well as reinforce principles, practices, behaviors, and attitudes related to high reliability (Appendix 1).11

Finally, closing the loop is critical to the leader rounding process and to improve bidirectional communication. Closed-loop communication, following up on and/or closing out an area of discussion, not only promotes a shared understanding of information but has been found to improve patient safety.19 Effective leader rounding for high reliability includes summarizing issues and opportunities, deciding on a date for resolution for open action items, and identifying who is responsible for taking action. Senior leaders are not responsible for resolving all issues. If a team or manager of a work area can solve any issues identified, this should be encouraged and supported so accountability is maintained at the most appropriate level of the organization.

Instrumental to leader rounding for high reliability is establishing a cadence for when leaders will visit work areas.14 The most critical strategy, especially in times of change, is consistency in rounding.11 At the start of implementation, we decided on a biweekly cadence. Initially leaders visited areas of the organization within their respective reporting structure. Once this was established, leaders periodically round in areas outside their scope of responsibility. This affords leaders the opportunity to observe other areas of the organization. As noted, it is important for leaders to be flexible with the rounding process especially in areas where direct patient care is being provided.

Tracking

Developing a tracking tool also is important for an effective leader rounding process. This tool is used to document issues and concerns identified during the rounding process, assign accountability, track the status of items, and close the loop when completed. One of the most commonly reported hurdles to staff sharing information to promote a culture of safety is the lack of feedback on what actions were taken to address the concern or issue raised with leadership. Closed-loop communication is critical for keeping staff continually engaged in efforts to promote a culture of safety.20 We have found that a tracking tool helps to ensure that closed-loop communication takes place.

Various platforms can be used for tracking items and providing follow-up, including paper worksheets, spreadsheets, databases, or third party software (eg, SharePoint, TruthPoint Rounds, GetWell Rounds). The tracking tool should have a standardized approach for prioritizing issues.

The stoplight classification system uses color coding (Figure 3).21 Green represents a safe space where there are no or low safety risks and are easily addressed at the local level by the area manager with or without assistance from the leadership team rounding, such as staffing.22,23 The unit manager has control of the situation and a plan is actively being implemented. Yellow signifies that areas are at risk, but with increased vigilance, issues do not escalate to a crisis state.22,23 Yellow-coded issues require further investigation by the leadership team. The senior leader on the team designates a process as well as a person responsible for closing the loop with the area manager regarding the status of problem resolution. For example, if the unit manager mentioned previously needing help to find staff, the area manager would suggest or take steps to help the unit manager. The area manager is then responsible for updating the frontline staff. Red-coded issues are urgent, identifying a state of crisis or high risk. Red issues need to be immediately addressed but cannot be resolved during rounds. Senior leaders must evaluate and make decisions to mitigate the threat. A member of the leadership team is tasked with following up with the area manager, typically within 24 hours. A staffing crisis that requires executive leadership help with identifying additional resources would be coded red.

The area manager is responsible for closing the loop with frontline staff. As frontline staff became more comfortable with the process, we observed an upward trend in the number of reported issues. We are now starting to see a downward trend in concerns shared during rounding as managers and frontline staff feel empowered to address issues at the lowest level.

Measuring Impact

Measuring the impact is a critical step to determine the overall effectiveness of leader rounding for high reliability. It can be as simple as requesting candid feedback from frontline staff, supervisors, managers, and service chiefs. For example, 4 months into the implementation process, the VABHS administered a brief staff survey on the overall process, perceived benefits, and challenges experienced (Appendix 2). Potential measures include the counts of leaders rounding, total rounds, rounds cancelled, and staff members actively participating in rounds. Outcomes that can be measured include issues identified, addressed, elevated, and remaining open; number of extended workdays due to rounds; staff staying overtime; and delays in patient care activities.23 Other measures to consider are the effects of rounding on staff as well as patient/family satisfaction, increase in the number of errors and near-miss events reported per month in a health care organizations’ patient safety reporting system, and increased engagement of staff members in continuous process improvement activities. Since the inception of leader rounding for high reliability, the VABHS has seen a slight increase in the number of events entered in the patient safety reporting system. Other factors that may have contributed to this change, including encouragement of reporting at safety forums, and tiered safety huddles.

DISCUSSION

This initiative involved the development and implementation of a leader rounding for high reliability process at the VABHS with the overarching goal of ensuring efficient communication exists among members of the health care team for delivering safe, quality patient care. The initiative was well received by staff from senior leadership to frontline personnel and promoted significant interest in efforts to improve safety across the health care system.

The pilot phase permitted us to examine the feasibility and acceptability of the process to leadership as well as frontline staff. The insight gained and lessons learned through the implementation process helped us make revisions where needed and develop the tools to ensure success. In the second phase of implementation, which commenced in December 2023, each executive leadership team member began leader rounding for high reliability with their respective department service chiefs. Throughout this phase, feedback will be sought on the overall process, perceived benefits, and challenges experienced to make improvements or changes as needed. We also will continue to monitor the number of events entered in the patient safety reporting system. Future efforts will focus on developing a robust program of evaluation to explore the impact of the program on patient/family satisfaction as well as safety outcomes.

Limitations

Developing and implementing a process for leader rounding for high reliability was undertaken to support the VABHS and VHA journey to high reliability. Other health care organizations and integrated systems might identify different processes for improving patient safety and to support their journey to becoming an HRO.

CONCLUSIONS

The importance of leader rounding for high reliability to improve patient safety cannot be emphasized enough in a time where health care systems have become increasingly complex. Health care is a complex adaptive system that requires effective, bidirectional communication and collaboration among all disciplines. One of the most useful, evidence-based strategies for promoting this communication and collaboration to improve a culture of safety is leader rounding for high reliability.

1. Drucker PF. They’re not employees, they’re people. Accessed November 15, 2023. https://hbr.org/2002/02/theyre-not-employees-theyre-people

2. Adams HA, Feudale RM. Implementation of a structured rounding tool for interprofessional care team rounds to improve communication and collaboration in patient care. Pediatr Nurs. 2018;44(5):229-233, 246.

3. Witz I, Lucchese S, Valenzano TJ, et al: Perceptions on implementation of a new standardized reporting tool to support structured morning rounds: recommendations for interprofessional teams and healthcare leaders. J Med Radiat Sci. 2022;53(4):S85-S92. doi:10.1016/j.jmir.2022.06.006

4. Blakeney EA, Chu F, White AA, et al. A scoping review of new implementations of interprofessional bedside rounding models to improve teamwork, care, and outcomes in hospitals. J Interprof Care. 2021;10:1-16 [Online ahead of print.] doi:10.1080/13561820.2021.1980379

5. Agency for Research and Healthcare Quality. High reliability. Accessed December 4, 2023. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primer/high-reliability

6. Hedenstrom M, Harrilson A, Heath M, Dyass S. “What’s old is new again”: innovative health care leader rounding—a strategy to foster connection. Nurse Lead. 2022;20(4):366-370.

7. Walton V, Hogden A, Long JC, Johnson JK, Greenfield D. How do interprofessional healthcare teams perceive the benefits and challenges of interdisciplinary ward rounds. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2019;12:1023-1032. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S226330

8. Walton V, Hogden A, Johnson J, Greenfield D. Ward rounds, participants, roles and perceptions: literature review. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2016;29(4):364-379. doi:10.1108/IJHCQA-04-2015-0053

9. Sexton JB, Adair KC, Leonard MW, et al. Providing feedback following leadership walkrounds is associated with better patient safety culture, higher employee engagement and lower burnout. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27(4):261-270. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2016-006399

10. Sexton JB, Adair KC, Profit J, et al. Safety culture and workforce well-being associations with positive leadership walkrounds. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2021;47(7):403-411. doi:10.1016/j.jcjq.2021.04.001

11. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. Leader’s guide to foundational high reliability organization (HRO) practices. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://dvagov.sharepoint.com/sites/OHT-PMO/high-reliability/Pages/default.aspx

12. Zajac S, Woods A, Tannenbaum S, Salas E, Hollada CL. Overcoming challenges to teamwork in healthcare: a team effectiveness framework and evidence-based guidance. Front Commun. 2021;6:1-20. doi:10.3389/fcomm.2021.606445

13. Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA’s Vision for a High Reliability Organization. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/forum/summer20/default.cfm?ForumMenu=summer20-1

14. Merchant NB, O’Neal J, Dealino-Perez C, Xiang J, Montoya A Jr, Murray JS. A high-reliability organization mindset. Am J Med Qual. 2022;37(6):504-510. doi:10.1097/JMQ.0000000000000086

15. Verhaegh KJ, Seller-Boersma A, Simons R, et al. An exploratory study of healthcare professionals’ perceptions of interprofessional communication and collaboration. J Interprof Care. 2017;31(3):397-400. doi:10.1080/13561820.2017.1289158

16. Winter M, Tjiong L. HCAHPS Series Part 2: Does purposeful leader rounding make a difference? Nurs Manag. 2015;46(2):26-32. doi:10.1097/01.NUMA.0000460034.25697.06

17. Beaird G, Baernholdt M, White KR. Perceptions of interdisciplinary rounding practices. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(7-8):1141-1150. doi:10.1111/jocn.15161

18. Hendricks S, LaMothe VJ, Kara A. Facilitators and barriers for interprofessional rounding: a qualitative study. Clin Nurse Spec. 2017;31(4):219-228. doi:10.1097/NUR.0000000000000310

19. Diaz MCG, Dawson K. Impact of simulation-based closed-loop communication training on medical errors in a pediatric emergency department. Am J Med Qual. 2020;35(6):474-478. doi:10.1177/1062860620912480

20. Williams S, Fiumara K, Kachalia A, Desai S. Closing the loop with ambulatory staff on safety reports. Jt Comm J Qual Saf. 2020;46(1):44-50. doi:10.1016/j.jcjq.2019.09.009

21. Parbhoo A, Batte J. Traffic lights: putting a stop to unsafe patient transfers. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2015;4(1):u204799.w2079. doi:10.1136/bmjquality.u204799.w2079

22. Prineas S, Culwick M, Endlich Y. A proposed system for standardization of colour-coding stages of escalating criticality in clinical incidents. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2021;34(6):752-760. doi:10.1097/ACO.0000000000001071.

23. Merchant NB, O’Neal J, Montoya A, Cox GR, Murray JS. Creating a process for the implementation of tiered huddles in a Veterans Affairs medical center. Mil Med. 2023;188(5-6):901-906. doi:10.1093/milmed/usac073

1. Drucker PF. They’re not employees, they’re people. Accessed November 15, 2023. https://hbr.org/2002/02/theyre-not-employees-theyre-people

2. Adams HA, Feudale RM. Implementation of a structured rounding tool for interprofessional care team rounds to improve communication and collaboration in patient care. Pediatr Nurs. 2018;44(5):229-233, 246.

3. Witz I, Lucchese S, Valenzano TJ, et al: Perceptions on implementation of a new standardized reporting tool to support structured morning rounds: recommendations for interprofessional teams and healthcare leaders. J Med Radiat Sci. 2022;53(4):S85-S92. doi:10.1016/j.jmir.2022.06.006

4. Blakeney EA, Chu F, White AA, et al. A scoping review of new implementations of interprofessional bedside rounding models to improve teamwork, care, and outcomes in hospitals. J Interprof Care. 2021;10:1-16 [Online ahead of print.] doi:10.1080/13561820.2021.1980379

5. Agency for Research and Healthcare Quality. High reliability. Accessed December 4, 2023. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primer/high-reliability

6. Hedenstrom M, Harrilson A, Heath M, Dyass S. “What’s old is new again”: innovative health care leader rounding—a strategy to foster connection. Nurse Lead. 2022;20(4):366-370.

7. Walton V, Hogden A, Long JC, Johnson JK, Greenfield D. How do interprofessional healthcare teams perceive the benefits and challenges of interdisciplinary ward rounds. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2019;12:1023-1032. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S226330

8. Walton V, Hogden A, Johnson J, Greenfield D. Ward rounds, participants, roles and perceptions: literature review. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2016;29(4):364-379. doi:10.1108/IJHCQA-04-2015-0053

9. Sexton JB, Adair KC, Leonard MW, et al. Providing feedback following leadership walkrounds is associated with better patient safety culture, higher employee engagement and lower burnout. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27(4):261-270. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2016-006399

10. Sexton JB, Adair KC, Profit J, et al. Safety culture and workforce well-being associations with positive leadership walkrounds. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2021;47(7):403-411. doi:10.1016/j.jcjq.2021.04.001

11. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. Leader’s guide to foundational high reliability organization (HRO) practices. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://dvagov.sharepoint.com/sites/OHT-PMO/high-reliability/Pages/default.aspx

12. Zajac S, Woods A, Tannenbaum S, Salas E, Hollada CL. Overcoming challenges to teamwork in healthcare: a team effectiveness framework and evidence-based guidance. Front Commun. 2021;6:1-20. doi:10.3389/fcomm.2021.606445

13. Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA’s Vision for a High Reliability Organization. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/forum/summer20/default.cfm?ForumMenu=summer20-1

14. Merchant NB, O’Neal J, Dealino-Perez C, Xiang J, Montoya A Jr, Murray JS. A high-reliability organization mindset. Am J Med Qual. 2022;37(6):504-510. doi:10.1097/JMQ.0000000000000086

15. Verhaegh KJ, Seller-Boersma A, Simons R, et al. An exploratory study of healthcare professionals’ perceptions of interprofessional communication and collaboration. J Interprof Care. 2017;31(3):397-400. doi:10.1080/13561820.2017.1289158

16. Winter M, Tjiong L. HCAHPS Series Part 2: Does purposeful leader rounding make a difference? Nurs Manag. 2015;46(2):26-32. doi:10.1097/01.NUMA.0000460034.25697.06

17. Beaird G, Baernholdt M, White KR. Perceptions of interdisciplinary rounding practices. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(7-8):1141-1150. doi:10.1111/jocn.15161

18. Hendricks S, LaMothe VJ, Kara A. Facilitators and barriers for interprofessional rounding: a qualitative study. Clin Nurse Spec. 2017;31(4):219-228. doi:10.1097/NUR.0000000000000310

19. Diaz MCG, Dawson K. Impact of simulation-based closed-loop communication training on medical errors in a pediatric emergency department. Am J Med Qual. 2020;35(6):474-478. doi:10.1177/1062860620912480

20. Williams S, Fiumara K, Kachalia A, Desai S. Closing the loop with ambulatory staff on safety reports. Jt Comm J Qual Saf. 2020;46(1):44-50. doi:10.1016/j.jcjq.2019.09.009

21. Parbhoo A, Batte J. Traffic lights: putting a stop to unsafe patient transfers. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2015;4(1):u204799.w2079. doi:10.1136/bmjquality.u204799.w2079

22. Prineas S, Culwick M, Endlich Y. A proposed system for standardization of colour-coding stages of escalating criticality in clinical incidents. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2021;34(6):752-760. doi:10.1097/ACO.0000000000001071.

23. Merchant NB, O’Neal J, Montoya A, Cox GR, Murray JS. Creating a process for the implementation of tiered huddles in a Veterans Affairs medical center. Mil Med. 2023;188(5-6):901-906. doi:10.1093/milmed/usac073