User login

Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSCR, SFHM, is a hospitalist and the chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) in Charleston. She is former SHM physician advisor, an SHM blogger, and member of SHM's Education Committee. She also serves as faculty of SHM's annual meeting "ABIM Maintenance of Certification (MOC) Learning Session" pre-course. Dr. Scheurer earned her undergraduate degree at Emory University in Atlanta, graduated medical school from the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, and trained at Duke University in Durham, N.C. She has served as physician editor of The Hospitalist since 2012.

Medicare’s Readmission Reduction Program Cuts $420M to U.S. Hospitals This Year

It’s that time of year again … the time when hospitals around the country are being notified of their 30-day readmission penalties from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Now in the fourth year of the program, many hospitals have come to dread the announcement of how much they are being penalized each year.1

This year, the readmission reduction program will decrease Medicare payments within a total of 2,592 U.S. hospitals, for a combined total of $420 million. This year’s program included readmissions from July 2011 to June 2014; the program uses a three-year rolling average for its calculations.2

The readmission program, which initially was implemented through the Affordable Care Act in 2012, aimed to penalize hospitals with higher than expected 30-day readmission rates on select conditions (currently heart attack, heart failure, pneumonia, COPD, and hip/knee replacements). Medicare estimates that it spends $17 billion a year in avoidable readmissions, which prompted the initial support for the program. For each condition, CMS calculates expected readmission rates (based on risk adjustment models that include age, severity of illness, and comorbid conditions) and observed rates, and then calculates an “excess readmission ratio” for each hospital. Based on the overall ratio, the hospital is penalized up to 3% of its Medicare payments for all inpatient stays for that fiscal year. Each year, CMS reassesses the readmission rates for hospitals and readjusts the magnitude of the penalty. The purpose of the program is to incent hospitals to invest in discharge planning and care coordination efforts and do everything possible to avoid readmissions.1

Who Gets Penalized?

This year, most eligible hospitals were penalized to some extent, and all but 209 of the hospitals that were penalized last year were penalized again.

The average Medicare payment reduction will be 0.61% per patient stay.

A total of 506 hospitals will lose at least 1% of their Medicare payments, and 38 hospitals will receive the maximum 3% penalty.

Unfortunately, safety net hospitals were about 60% more likely than other hospitals to have been penalized in all three years of the program. In addition, hospitals with the lowest profit margins were 36% more likely to be penalized than those with higher margins.

Some states were disproportionately affected, with at least three-quarters of hospitals affected in Alabama, Connecticut, Florida, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Virginia, and the District of Columbia. States that fared the best were Idaho, Iowa, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, and South Dakota.

Most of the 2,232 hospitals that avoided a penalty were spared because they were exempted from the program (Veterans Affairs hospitals, children’s hospitals, critical access hospitals, or those with too few Medicare patients), not because of exceptional performance.

Does the Program Work?

Despite criticism, there is no doubt that this program has forced hospitals to pay keen attention to transitions of care and avoidable readmissions. And it does appear to be an effective strategy for CMS to achieve its goals; there has been an overall decrease in 30-day readmission rates among Medicare recipients since the program began, in all types of hospitals.

Compared to 2012, there were 100,000 fewer readmissions among Medicare beneficiaries in the U.S. in 2013. As such, there is no evidence that the program will be discontinued, although it will hopefully be altered in some key aspects.3

What the Future Holds

The program has been criticized on many fronts. For one, it recalculates a three-year rolling average each year, which makes it incredibly difficult to “wash out” older (poor) performance and get off the penalty list.

In addition, critics have pointed out that the program fails to take into account the socioeconomic background of patients when assessing readmission penalties. Many argue that social determinants of readmissions that are beyond the immediate control of a hospital system can have a huge impact on readmission rates.

The National Quality Forum is examining the impact of these factors on readmissions, but this evaluation likely will take years.

In the meantime, the Hospital Readmissions Program Accuracy and Accountability Act of 2014 has been introduced as a bill that would require CMS to factor socioeconomic status into the equation when determining readmission penalties.

What All This Means for Hospitalists

All of us working within the confines of the current program can do a few things to improve our understanding and our hospitals’ performance:

- If your hospital is one that incurred a penalty, know that most “eligible” hospitals also incurred a penalty.

- Look at how your hospital fared within your state and find out if you are above or below average in the amount.3

- Continue to focus on exemplary care transition protocols, policies, and programs within your hospital system, because the penalties are unlikely to go away and are very likely to expand over time.

- Support any advocacy efforts toward improving risk adjustment methodologies for readmissions; all hospitals are likely to benefit from more accurate risk adjustments.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Readmissions reduction program. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Rau J. Half of nation’s hospitals fail again to escape Medicare’s readmissions penalties. August 3, 2015. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Medpac. The hospital readmission penalty: how well is it working?. Accessed October 3, 2015.

It’s that time of year again … the time when hospitals around the country are being notified of their 30-day readmission penalties from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Now in the fourth year of the program, many hospitals have come to dread the announcement of how much they are being penalized each year.1

This year, the readmission reduction program will decrease Medicare payments within a total of 2,592 U.S. hospitals, for a combined total of $420 million. This year’s program included readmissions from July 2011 to June 2014; the program uses a three-year rolling average for its calculations.2

The readmission program, which initially was implemented through the Affordable Care Act in 2012, aimed to penalize hospitals with higher than expected 30-day readmission rates on select conditions (currently heart attack, heart failure, pneumonia, COPD, and hip/knee replacements). Medicare estimates that it spends $17 billion a year in avoidable readmissions, which prompted the initial support for the program. For each condition, CMS calculates expected readmission rates (based on risk adjustment models that include age, severity of illness, and comorbid conditions) and observed rates, and then calculates an “excess readmission ratio” for each hospital. Based on the overall ratio, the hospital is penalized up to 3% of its Medicare payments for all inpatient stays for that fiscal year. Each year, CMS reassesses the readmission rates for hospitals and readjusts the magnitude of the penalty. The purpose of the program is to incent hospitals to invest in discharge planning and care coordination efforts and do everything possible to avoid readmissions.1

Who Gets Penalized?

This year, most eligible hospitals were penalized to some extent, and all but 209 of the hospitals that were penalized last year were penalized again.

The average Medicare payment reduction will be 0.61% per patient stay.

A total of 506 hospitals will lose at least 1% of their Medicare payments, and 38 hospitals will receive the maximum 3% penalty.

Unfortunately, safety net hospitals were about 60% more likely than other hospitals to have been penalized in all three years of the program. In addition, hospitals with the lowest profit margins were 36% more likely to be penalized than those with higher margins.

Some states were disproportionately affected, with at least three-quarters of hospitals affected in Alabama, Connecticut, Florida, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Virginia, and the District of Columbia. States that fared the best were Idaho, Iowa, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, and South Dakota.

Most of the 2,232 hospitals that avoided a penalty were spared because they were exempted from the program (Veterans Affairs hospitals, children’s hospitals, critical access hospitals, or those with too few Medicare patients), not because of exceptional performance.

Does the Program Work?

Despite criticism, there is no doubt that this program has forced hospitals to pay keen attention to transitions of care and avoidable readmissions. And it does appear to be an effective strategy for CMS to achieve its goals; there has been an overall decrease in 30-day readmission rates among Medicare recipients since the program began, in all types of hospitals.

Compared to 2012, there were 100,000 fewer readmissions among Medicare beneficiaries in the U.S. in 2013. As such, there is no evidence that the program will be discontinued, although it will hopefully be altered in some key aspects.3

What the Future Holds

The program has been criticized on many fronts. For one, it recalculates a three-year rolling average each year, which makes it incredibly difficult to “wash out” older (poor) performance and get off the penalty list.

In addition, critics have pointed out that the program fails to take into account the socioeconomic background of patients when assessing readmission penalties. Many argue that social determinants of readmissions that are beyond the immediate control of a hospital system can have a huge impact on readmission rates.

The National Quality Forum is examining the impact of these factors on readmissions, but this evaluation likely will take years.

In the meantime, the Hospital Readmissions Program Accuracy and Accountability Act of 2014 has been introduced as a bill that would require CMS to factor socioeconomic status into the equation when determining readmission penalties.

What All This Means for Hospitalists

All of us working within the confines of the current program can do a few things to improve our understanding and our hospitals’ performance:

- If your hospital is one that incurred a penalty, know that most “eligible” hospitals also incurred a penalty.

- Look at how your hospital fared within your state and find out if you are above or below average in the amount.3

- Continue to focus on exemplary care transition protocols, policies, and programs within your hospital system, because the penalties are unlikely to go away and are very likely to expand over time.

- Support any advocacy efforts toward improving risk adjustment methodologies for readmissions; all hospitals are likely to benefit from more accurate risk adjustments.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Readmissions reduction program. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Rau J. Half of nation’s hospitals fail again to escape Medicare’s readmissions penalties. August 3, 2015. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Medpac. The hospital readmission penalty: how well is it working?. Accessed October 3, 2015.

It’s that time of year again … the time when hospitals around the country are being notified of their 30-day readmission penalties from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Now in the fourth year of the program, many hospitals have come to dread the announcement of how much they are being penalized each year.1

This year, the readmission reduction program will decrease Medicare payments within a total of 2,592 U.S. hospitals, for a combined total of $420 million. This year’s program included readmissions from July 2011 to June 2014; the program uses a three-year rolling average for its calculations.2

The readmission program, which initially was implemented through the Affordable Care Act in 2012, aimed to penalize hospitals with higher than expected 30-day readmission rates on select conditions (currently heart attack, heart failure, pneumonia, COPD, and hip/knee replacements). Medicare estimates that it spends $17 billion a year in avoidable readmissions, which prompted the initial support for the program. For each condition, CMS calculates expected readmission rates (based on risk adjustment models that include age, severity of illness, and comorbid conditions) and observed rates, and then calculates an “excess readmission ratio” for each hospital. Based on the overall ratio, the hospital is penalized up to 3% of its Medicare payments for all inpatient stays for that fiscal year. Each year, CMS reassesses the readmission rates for hospitals and readjusts the magnitude of the penalty. The purpose of the program is to incent hospitals to invest in discharge planning and care coordination efforts and do everything possible to avoid readmissions.1

Who Gets Penalized?

This year, most eligible hospitals were penalized to some extent, and all but 209 of the hospitals that were penalized last year were penalized again.

The average Medicare payment reduction will be 0.61% per patient stay.

A total of 506 hospitals will lose at least 1% of their Medicare payments, and 38 hospitals will receive the maximum 3% penalty.

Unfortunately, safety net hospitals were about 60% more likely than other hospitals to have been penalized in all three years of the program. In addition, hospitals with the lowest profit margins were 36% more likely to be penalized than those with higher margins.

Some states were disproportionately affected, with at least three-quarters of hospitals affected in Alabama, Connecticut, Florida, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Virginia, and the District of Columbia. States that fared the best were Idaho, Iowa, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, and South Dakota.

Most of the 2,232 hospitals that avoided a penalty were spared because they were exempted from the program (Veterans Affairs hospitals, children’s hospitals, critical access hospitals, or those with too few Medicare patients), not because of exceptional performance.

Does the Program Work?

Despite criticism, there is no doubt that this program has forced hospitals to pay keen attention to transitions of care and avoidable readmissions. And it does appear to be an effective strategy for CMS to achieve its goals; there has been an overall decrease in 30-day readmission rates among Medicare recipients since the program began, in all types of hospitals.

Compared to 2012, there were 100,000 fewer readmissions among Medicare beneficiaries in the U.S. in 2013. As such, there is no evidence that the program will be discontinued, although it will hopefully be altered in some key aspects.3

What the Future Holds

The program has been criticized on many fronts. For one, it recalculates a three-year rolling average each year, which makes it incredibly difficult to “wash out” older (poor) performance and get off the penalty list.

In addition, critics have pointed out that the program fails to take into account the socioeconomic background of patients when assessing readmission penalties. Many argue that social determinants of readmissions that are beyond the immediate control of a hospital system can have a huge impact on readmission rates.

The National Quality Forum is examining the impact of these factors on readmissions, but this evaluation likely will take years.

In the meantime, the Hospital Readmissions Program Accuracy and Accountability Act of 2014 has been introduced as a bill that would require CMS to factor socioeconomic status into the equation when determining readmission penalties.

What All This Means for Hospitalists

All of us working within the confines of the current program can do a few things to improve our understanding and our hospitals’ performance:

- If your hospital is one that incurred a penalty, know that most “eligible” hospitals also incurred a penalty.

- Look at how your hospital fared within your state and find out if you are above or below average in the amount.3

- Continue to focus on exemplary care transition protocols, policies, and programs within your hospital system, because the penalties are unlikely to go away and are very likely to expand over time.

- Support any advocacy efforts toward improving risk adjustment methodologies for readmissions; all hospitals are likely to benefit from more accurate risk adjustments.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Readmissions reduction program. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Rau J. Half of nation’s hospitals fail again to escape Medicare’s readmissions penalties. August 3, 2015. Accessed October 3, 2015.

- Medpac. The hospital readmission penalty: how well is it working?. Accessed October 3, 2015.

Hospitalists’ Code of Conduct Needed for Sick Day Callouts

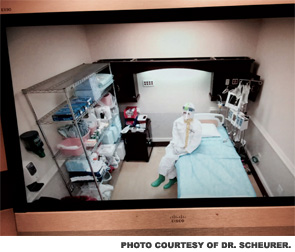

It is Tuesday morning, and I drag myself out of bed after a very restless night. It is day number three of a syndrome of fatigue, headache, and moderate productive cough. I have been on service for eight days of a two-week stretch; I am hoping to “make it to the end of the week.” I convince myself I am “not that sick” and head into work for a long day of rounds, after two cups of coffee and 600 mg of Motrin. Throughout the day, I try to hide my cough from my residents and students, and especially the nurses and my patients. I have a pocket full of cough drops and a cup of ice water at hand to stifle any coughing fits that could reveal how I actually feel. This is not the first time I have come to work only “half well.” I convince myself I am not contagious, as long as I wash my hands and control my cough. Without a fever, how could I possibly justify calling in a colleague to cover for me?

I am not alone in my psychological justifications for coming to work. A recent JAMA Pediatrics article found that 83% of clinicians admitted to coming to work while sick, while 95% admitted to knowing that it could be dangerous to their patients.1,2 The study surveyed approximately 500 attendings and 250 advanced practice providers at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. A substantial minority of providers (9%) admitted to coming to work sick at least five times in the past year.

The reasons these providers gave for working in spite of being ill likely ring true with each and every hospitalist in the field: They were concerned about 1) letting down their patients or 2) hospital staffing in their absence. Most providers also expressed concern about the continuity of care for their patients in their absence. Most also admitted that they feared being ostracized by their colleagues and believed that there were unwritten but real expectations for them to work regardless of personal illness.

Historically, physicians and other healthcare providers have been widely believed to be relatively immune to mundane ailments, by themselves and by others. How incredibly rare it is to hear, “Sorry, your doctor is sick; we have to reschedule your visit.” Even when afflicted by physical impairments, physicians have long considered it more “honorable” to work through these infirmities than to resign to physical limitations and ask for help.

Misguided or Mishandled

This sense of duty starts early in medical training and continues throughout a physician’s early career. I discovered this firsthand during my internship after suffering a stress fracture in my foot. I woke up one morning with significant foot pain and swelling but hobbled through rounds without a word spoken about my limp. By the afternoon, I could hardly bear weight on my foot, so one of my fellow interns suggested I limp over to the orthopedic clinic; thankfully, they saw me the same day, diagnosed the stress fracture, and fitted me in a walking cast. The next day on rounds, when I asked my attending if we could take the elevator up the two floors to the next patient, he looked annoyed and said I could meet them there; they scurried up the stairs. For the next few weeks, I never missed a minute of work but kept trailing behind and missing key pieces of presentations and information from rounds, having to hobble back and forth to the elevator between floors.

The lesson I quickly learned back then was that if I was not “fit for duty” with any sort of physical ailment, it was clearly my problem to make up for my deficits, because the work expectations would go unchanged. Although a stress fracture did not put my patients at risk, the experience sent a strong message: Regardless of the impact on patients, it is always better to come to work than to stay home, whatever the type or degree of affliction.

The JAMA Pediatrics study did find substantial differences in the types of symptoms that would keep a provider at home: While 75% reported they would come to work with a cough and rhinorrhea, 30% would come with diarrhea, 16% would come with a fever, and only 5% would come with vomiting.

To be honest, this sounds about right in comparison to what my threshold would be, and it is about what I would accept as reasonable from a colleague. I do hope that if I were “really sick,” with fever and/or vomiting, I would have the good sense to stay home and ask for coverage, and I hope my colleagues and I would support each other in these decisions.

The study really gets at the sociocultural factors that steer physicians into making such decisions, based on the conditions for being excused that they think are socially acceptable. I suspect these are similar to those that other industries would also consider acceptable. But, of course, the difference is that workers in other industries are less likely to cause harm to large numbers of vulnerable and innocent “bystanders.” Adding to the problem, there is no good “definition” for what is “too sick”; although it is complicated and varies by person, the definition should at least take into account the level of potential contagion and risk to patients.

The authors suggest that, in order to remedy this longstanding situation, open dialogue needs to take place among physician groups to reduce the ambiguity about what is appropriate. A good start would be the generation of clear policies that restrict providers from coming to work with specifics signs/symptoms.

As hospitalists, we should all discuss the article within our groups and honestly determine in advance what our “code of conduct” should be for illnesses, based on our provider mix and our patient populations. (Decisions for ICU, medical-surgical, or oncology may vary.) This would reduce ambiguity and create new social norms about when to stay home. In addition, administrative and provider group leaders need to show strong leadership and support for such policies and ensure adequate staffing in the event of appropriate callouts. Such policies need to ensure that callouts are equitable and non-punitive. These relatively simple measures would go a long way in reducing the risk of illness among ourselves and our patients.

References

- Szymczak JE, Smathers S, Hoegg C, Klieger S, Coffin SE, Sammons JS. Reasons why physicians and advanced practice clinicians work while sick: A mixed methods analysis [published online ahead of print July 6, 2015]. JAMA Pediatr. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0684.

- Starke JR, Jackson MA. When the health care worker is sick: primum non nocere [published online ahead of print July 6, 2015]. JAMA Pediatr. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0994.

It is Tuesday morning, and I drag myself out of bed after a very restless night. It is day number three of a syndrome of fatigue, headache, and moderate productive cough. I have been on service for eight days of a two-week stretch; I am hoping to “make it to the end of the week.” I convince myself I am “not that sick” and head into work for a long day of rounds, after two cups of coffee and 600 mg of Motrin. Throughout the day, I try to hide my cough from my residents and students, and especially the nurses and my patients. I have a pocket full of cough drops and a cup of ice water at hand to stifle any coughing fits that could reveal how I actually feel. This is not the first time I have come to work only “half well.” I convince myself I am not contagious, as long as I wash my hands and control my cough. Without a fever, how could I possibly justify calling in a colleague to cover for me?

I am not alone in my psychological justifications for coming to work. A recent JAMA Pediatrics article found that 83% of clinicians admitted to coming to work while sick, while 95% admitted to knowing that it could be dangerous to their patients.1,2 The study surveyed approximately 500 attendings and 250 advanced practice providers at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. A substantial minority of providers (9%) admitted to coming to work sick at least five times in the past year.

The reasons these providers gave for working in spite of being ill likely ring true with each and every hospitalist in the field: They were concerned about 1) letting down their patients or 2) hospital staffing in their absence. Most providers also expressed concern about the continuity of care for their patients in their absence. Most also admitted that they feared being ostracized by their colleagues and believed that there were unwritten but real expectations for them to work regardless of personal illness.

Historically, physicians and other healthcare providers have been widely believed to be relatively immune to mundane ailments, by themselves and by others. How incredibly rare it is to hear, “Sorry, your doctor is sick; we have to reschedule your visit.” Even when afflicted by physical impairments, physicians have long considered it more “honorable” to work through these infirmities than to resign to physical limitations and ask for help.

Misguided or Mishandled

This sense of duty starts early in medical training and continues throughout a physician’s early career. I discovered this firsthand during my internship after suffering a stress fracture in my foot. I woke up one morning with significant foot pain and swelling but hobbled through rounds without a word spoken about my limp. By the afternoon, I could hardly bear weight on my foot, so one of my fellow interns suggested I limp over to the orthopedic clinic; thankfully, they saw me the same day, diagnosed the stress fracture, and fitted me in a walking cast. The next day on rounds, when I asked my attending if we could take the elevator up the two floors to the next patient, he looked annoyed and said I could meet them there; they scurried up the stairs. For the next few weeks, I never missed a minute of work but kept trailing behind and missing key pieces of presentations and information from rounds, having to hobble back and forth to the elevator between floors.

The lesson I quickly learned back then was that if I was not “fit for duty” with any sort of physical ailment, it was clearly my problem to make up for my deficits, because the work expectations would go unchanged. Although a stress fracture did not put my patients at risk, the experience sent a strong message: Regardless of the impact on patients, it is always better to come to work than to stay home, whatever the type or degree of affliction.

The JAMA Pediatrics study did find substantial differences in the types of symptoms that would keep a provider at home: While 75% reported they would come to work with a cough and rhinorrhea, 30% would come with diarrhea, 16% would come with a fever, and only 5% would come with vomiting.

To be honest, this sounds about right in comparison to what my threshold would be, and it is about what I would accept as reasonable from a colleague. I do hope that if I were “really sick,” with fever and/or vomiting, I would have the good sense to stay home and ask for coverage, and I hope my colleagues and I would support each other in these decisions.

The study really gets at the sociocultural factors that steer physicians into making such decisions, based on the conditions for being excused that they think are socially acceptable. I suspect these are similar to those that other industries would also consider acceptable. But, of course, the difference is that workers in other industries are less likely to cause harm to large numbers of vulnerable and innocent “bystanders.” Adding to the problem, there is no good “definition” for what is “too sick”; although it is complicated and varies by person, the definition should at least take into account the level of potential contagion and risk to patients.

The authors suggest that, in order to remedy this longstanding situation, open dialogue needs to take place among physician groups to reduce the ambiguity about what is appropriate. A good start would be the generation of clear policies that restrict providers from coming to work with specifics signs/symptoms.

As hospitalists, we should all discuss the article within our groups and honestly determine in advance what our “code of conduct” should be for illnesses, based on our provider mix and our patient populations. (Decisions for ICU, medical-surgical, or oncology may vary.) This would reduce ambiguity and create new social norms about when to stay home. In addition, administrative and provider group leaders need to show strong leadership and support for such policies and ensure adequate staffing in the event of appropriate callouts. Such policies need to ensure that callouts are equitable and non-punitive. These relatively simple measures would go a long way in reducing the risk of illness among ourselves and our patients.

References

- Szymczak JE, Smathers S, Hoegg C, Klieger S, Coffin SE, Sammons JS. Reasons why physicians and advanced practice clinicians work while sick: A mixed methods analysis [published online ahead of print July 6, 2015]. JAMA Pediatr. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0684.

- Starke JR, Jackson MA. When the health care worker is sick: primum non nocere [published online ahead of print July 6, 2015]. JAMA Pediatr. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0994.

It is Tuesday morning, and I drag myself out of bed after a very restless night. It is day number three of a syndrome of fatigue, headache, and moderate productive cough. I have been on service for eight days of a two-week stretch; I am hoping to “make it to the end of the week.” I convince myself I am “not that sick” and head into work for a long day of rounds, after two cups of coffee and 600 mg of Motrin. Throughout the day, I try to hide my cough from my residents and students, and especially the nurses and my patients. I have a pocket full of cough drops and a cup of ice water at hand to stifle any coughing fits that could reveal how I actually feel. This is not the first time I have come to work only “half well.” I convince myself I am not contagious, as long as I wash my hands and control my cough. Without a fever, how could I possibly justify calling in a colleague to cover for me?

I am not alone in my psychological justifications for coming to work. A recent JAMA Pediatrics article found that 83% of clinicians admitted to coming to work while sick, while 95% admitted to knowing that it could be dangerous to their patients.1,2 The study surveyed approximately 500 attendings and 250 advanced practice providers at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. A substantial minority of providers (9%) admitted to coming to work sick at least five times in the past year.

The reasons these providers gave for working in spite of being ill likely ring true with each and every hospitalist in the field: They were concerned about 1) letting down their patients or 2) hospital staffing in their absence. Most providers also expressed concern about the continuity of care for their patients in their absence. Most also admitted that they feared being ostracized by their colleagues and believed that there were unwritten but real expectations for them to work regardless of personal illness.

Historically, physicians and other healthcare providers have been widely believed to be relatively immune to mundane ailments, by themselves and by others. How incredibly rare it is to hear, “Sorry, your doctor is sick; we have to reschedule your visit.” Even when afflicted by physical impairments, physicians have long considered it more “honorable” to work through these infirmities than to resign to physical limitations and ask for help.

Misguided or Mishandled

This sense of duty starts early in medical training and continues throughout a physician’s early career. I discovered this firsthand during my internship after suffering a stress fracture in my foot. I woke up one morning with significant foot pain and swelling but hobbled through rounds without a word spoken about my limp. By the afternoon, I could hardly bear weight on my foot, so one of my fellow interns suggested I limp over to the orthopedic clinic; thankfully, they saw me the same day, diagnosed the stress fracture, and fitted me in a walking cast. The next day on rounds, when I asked my attending if we could take the elevator up the two floors to the next patient, he looked annoyed and said I could meet them there; they scurried up the stairs. For the next few weeks, I never missed a minute of work but kept trailing behind and missing key pieces of presentations and information from rounds, having to hobble back and forth to the elevator between floors.

The lesson I quickly learned back then was that if I was not “fit for duty” with any sort of physical ailment, it was clearly my problem to make up for my deficits, because the work expectations would go unchanged. Although a stress fracture did not put my patients at risk, the experience sent a strong message: Regardless of the impact on patients, it is always better to come to work than to stay home, whatever the type or degree of affliction.

The JAMA Pediatrics study did find substantial differences in the types of symptoms that would keep a provider at home: While 75% reported they would come to work with a cough and rhinorrhea, 30% would come with diarrhea, 16% would come with a fever, and only 5% would come with vomiting.

To be honest, this sounds about right in comparison to what my threshold would be, and it is about what I would accept as reasonable from a colleague. I do hope that if I were “really sick,” with fever and/or vomiting, I would have the good sense to stay home and ask for coverage, and I hope my colleagues and I would support each other in these decisions.

The study really gets at the sociocultural factors that steer physicians into making such decisions, based on the conditions for being excused that they think are socially acceptable. I suspect these are similar to those that other industries would also consider acceptable. But, of course, the difference is that workers in other industries are less likely to cause harm to large numbers of vulnerable and innocent “bystanders.” Adding to the problem, there is no good “definition” for what is “too sick”; although it is complicated and varies by person, the definition should at least take into account the level of potential contagion and risk to patients.

The authors suggest that, in order to remedy this longstanding situation, open dialogue needs to take place among physician groups to reduce the ambiguity about what is appropriate. A good start would be the generation of clear policies that restrict providers from coming to work with specifics signs/symptoms.

As hospitalists, we should all discuss the article within our groups and honestly determine in advance what our “code of conduct” should be for illnesses, based on our provider mix and our patient populations. (Decisions for ICU, medical-surgical, or oncology may vary.) This would reduce ambiguity and create new social norms about when to stay home. In addition, administrative and provider group leaders need to show strong leadership and support for such policies and ensure adequate staffing in the event of appropriate callouts. Such policies need to ensure that callouts are equitable and non-punitive. These relatively simple measures would go a long way in reducing the risk of illness among ourselves and our patients.

References

- Szymczak JE, Smathers S, Hoegg C, Klieger S, Coffin SE, Sammons JS. Reasons why physicians and advanced practice clinicians work while sick: A mixed methods analysis [published online ahead of print July 6, 2015]. JAMA Pediatr. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0684.

- Starke JR, Jackson MA. When the health care worker is sick: primum non nocere [published online ahead of print July 6, 2015]. JAMA Pediatr. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0994.

Resident Education, Feedback, Incentives Improve Patient Satisfaction

Editor’s note: This article first appeared on SHM’s “The Hospital Leader” blog.

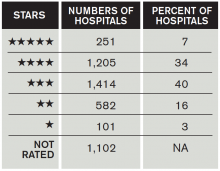

Patient satisfaction survey performance is becoming increasingly important for hospitals, because the ratings are being used by payers in pay-for-performance programs more and more (including the CMS Hospital Value-Based Purchasing program). CMS also recently released its “Five-Star Quality Rating System” for hospitals, which publicly grades hospitals, using one to five stars, based on their patient satisfaction scores.

How Did Hospitals Do in Medicare’s Patient Quality Ratings?

Unfortunately, there is little literature to guide physicians on exactly HOW to improve patient satisfaction scores for themselves or their groups. A recent publication in the Journal of Hospital Medicine found a feasible and effective intervention to improve patient satisfaction scores among trainees, the methodology of which could easily be applied to hospitalists.

Gaurav Banka, MD, a former internal medicine resident (and current cardiology fellow) at UCLA Hospital, was interviewed about his team’s recent publication in the Journal of Hospital Medicine. In the interview, he opined about “improving patient satisfaction through resident education, feedback, and incentives.” The study he published found that this combination of interventions among internal medicine residents improved relevant HCAHPS scores by approximately 8%.

The following are excerpts from a Q&A session I had with Dr. Banka:

Question: Can you briefly summarize the intervention(s)?

Answer: There were three total interventions put in place simultaneously: an educational conference on best practices in patient communication, a recognition-reward program (recognition within the department and a movie package for high performers), and real-time feedback to the residents from their patients via a survey. The last component was the most impactful to the residents. Patients were randomly surveyed on how their residents were communicating with them, and the results were sent to the resident for review and self-reflection within weeks.

Q: How did you become interested in resident interventions to improve HCAHPS?

A: I noticed as an intern [that] there was almost no emphasis placed on patient communication skills, and there was almost no feedback given to residents on how they were performing. I felt that this was a very important piece of feedback that residents were lacking and was very interested in creating a program that would help them learn new communication skills and get feedback on how they were doing.

Q: How should hospitalists use this study information to change their practice?

A: Hospital medicine programs should have some way to measure and give feedback to individual hospitalists on what the patient is experiencing with respect to communication. The intervention from this study should be easily scalable to any practice. There was almost no cost associated with the patient survey distribution, and it gave incredibly valuable individualized feedback about communication skills directly from the patients themselves. It should be feasible to implement this type of audit and feedback within any size hospital medicine program.

Q: Were there any unexpected findings in your study?

A: We were surprised at how much of an impact it had on HCAHPS scores. Not only did it impact physician communication ratings, but [it] also had an impressive impact on overall hospital ratings.

Q: Where does this take us with respect to future research efforts?

A: Our team is now working on expanding this program to other residency programs, as well as expanding it to attending physicians, within and outside the department of medicine.

In summary, Dr. Banka’s team found this relatively simple intervention was able to sizably improve the HCAHPS scores of recipient providers. Such interventions should be seriously considered by hospital medicine programs looking to improve their publicly reported patient satisfaction scores.

Editor’s note: This article first appeared on SHM’s “The Hospital Leader” blog.

Patient satisfaction survey performance is becoming increasingly important for hospitals, because the ratings are being used by payers in pay-for-performance programs more and more (including the CMS Hospital Value-Based Purchasing program). CMS also recently released its “Five-Star Quality Rating System” for hospitals, which publicly grades hospitals, using one to five stars, based on their patient satisfaction scores.

How Did Hospitals Do in Medicare’s Patient Quality Ratings?

Unfortunately, there is little literature to guide physicians on exactly HOW to improve patient satisfaction scores for themselves or their groups. A recent publication in the Journal of Hospital Medicine found a feasible and effective intervention to improve patient satisfaction scores among trainees, the methodology of which could easily be applied to hospitalists.

Gaurav Banka, MD, a former internal medicine resident (and current cardiology fellow) at UCLA Hospital, was interviewed about his team’s recent publication in the Journal of Hospital Medicine. In the interview, he opined about “improving patient satisfaction through resident education, feedback, and incentives.” The study he published found that this combination of interventions among internal medicine residents improved relevant HCAHPS scores by approximately 8%.

The following are excerpts from a Q&A session I had with Dr. Banka:

Question: Can you briefly summarize the intervention(s)?

Answer: There were three total interventions put in place simultaneously: an educational conference on best practices in patient communication, a recognition-reward program (recognition within the department and a movie package for high performers), and real-time feedback to the residents from their patients via a survey. The last component was the most impactful to the residents. Patients were randomly surveyed on how their residents were communicating with them, and the results were sent to the resident for review and self-reflection within weeks.

Q: How did you become interested in resident interventions to improve HCAHPS?

A: I noticed as an intern [that] there was almost no emphasis placed on patient communication skills, and there was almost no feedback given to residents on how they were performing. I felt that this was a very important piece of feedback that residents were lacking and was very interested in creating a program that would help them learn new communication skills and get feedback on how they were doing.

Q: How should hospitalists use this study information to change their practice?

A: Hospital medicine programs should have some way to measure and give feedback to individual hospitalists on what the patient is experiencing with respect to communication. The intervention from this study should be easily scalable to any practice. There was almost no cost associated with the patient survey distribution, and it gave incredibly valuable individualized feedback about communication skills directly from the patients themselves. It should be feasible to implement this type of audit and feedback within any size hospital medicine program.

Q: Were there any unexpected findings in your study?

A: We were surprised at how much of an impact it had on HCAHPS scores. Not only did it impact physician communication ratings, but [it] also had an impressive impact on overall hospital ratings.

Q: Where does this take us with respect to future research efforts?

A: Our team is now working on expanding this program to other residency programs, as well as expanding it to attending physicians, within and outside the department of medicine.

In summary, Dr. Banka’s team found this relatively simple intervention was able to sizably improve the HCAHPS scores of recipient providers. Such interventions should be seriously considered by hospital medicine programs looking to improve their publicly reported patient satisfaction scores.

Editor’s note: This article first appeared on SHM’s “The Hospital Leader” blog.

Patient satisfaction survey performance is becoming increasingly important for hospitals, because the ratings are being used by payers in pay-for-performance programs more and more (including the CMS Hospital Value-Based Purchasing program). CMS also recently released its “Five-Star Quality Rating System” for hospitals, which publicly grades hospitals, using one to five stars, based on their patient satisfaction scores.

How Did Hospitals Do in Medicare’s Patient Quality Ratings?

Unfortunately, there is little literature to guide physicians on exactly HOW to improve patient satisfaction scores for themselves or their groups. A recent publication in the Journal of Hospital Medicine found a feasible and effective intervention to improve patient satisfaction scores among trainees, the methodology of which could easily be applied to hospitalists.

Gaurav Banka, MD, a former internal medicine resident (and current cardiology fellow) at UCLA Hospital, was interviewed about his team’s recent publication in the Journal of Hospital Medicine. In the interview, he opined about “improving patient satisfaction through resident education, feedback, and incentives.” The study he published found that this combination of interventions among internal medicine residents improved relevant HCAHPS scores by approximately 8%.

The following are excerpts from a Q&A session I had with Dr. Banka:

Question: Can you briefly summarize the intervention(s)?

Answer: There were three total interventions put in place simultaneously: an educational conference on best practices in patient communication, a recognition-reward program (recognition within the department and a movie package for high performers), and real-time feedback to the residents from their patients via a survey. The last component was the most impactful to the residents. Patients were randomly surveyed on how their residents were communicating with them, and the results were sent to the resident for review and self-reflection within weeks.

Q: How did you become interested in resident interventions to improve HCAHPS?

A: I noticed as an intern [that] there was almost no emphasis placed on patient communication skills, and there was almost no feedback given to residents on how they were performing. I felt that this was a very important piece of feedback that residents were lacking and was very interested in creating a program that would help them learn new communication skills and get feedback on how they were doing.

Q: How should hospitalists use this study information to change their practice?

A: Hospital medicine programs should have some way to measure and give feedback to individual hospitalists on what the patient is experiencing with respect to communication. The intervention from this study should be easily scalable to any practice. There was almost no cost associated with the patient survey distribution, and it gave incredibly valuable individualized feedback about communication skills directly from the patients themselves. It should be feasible to implement this type of audit and feedback within any size hospital medicine program.

Q: Were there any unexpected findings in your study?

A: We were surprised at how much of an impact it had on HCAHPS scores. Not only did it impact physician communication ratings, but [it] also had an impressive impact on overall hospital ratings.

Q: Where does this take us with respect to future research efforts?

A: Our team is now working on expanding this program to other residency programs, as well as expanding it to attending physicians, within and outside the department of medicine.

In summary, Dr. Banka’s team found this relatively simple intervention was able to sizably improve the HCAHPS scores of recipient providers. Such interventions should be seriously considered by hospital medicine programs looking to improve their publicly reported patient satisfaction scores.

Medical Professionalism: Its Evolution and What It Means to Hospitalists

Professionalism is an overused word in the medical industry. What exactly is meant by professionalism, and what should it mean to hospitalists? Wikipedia notes that a professional is one who earns a living from a specified activity that has standards of education and training that prepare members of the profession with the knowledge and skills necessary to perform the role required. In addition, professionals are subject to strict codes of conduct enshrining rigorous ethical and moral obligations.

Physicians are the consummate professionals; over centuries, we have been afforded the reputation of being one of the “highest-ranking” professionals within societies, along with divinity and law. We are held to very high standards, both in and out of the workplace, including arduous and rigorous standards of education and training. We are in one of the only professions that take the Hippocratic Oath at graduation. This oath requires us to swear to uphold specific ethical standards. Being a professional means we always act within our professional standards and advocate for our patients in all circumstances.1

Threats to Professionalism?

Over the past several decades, concern has been growing about a widespread decline in professionalism among physicians, a decline that extends beyond a single generation. There are many purported reasons for this erosion of professionalism; we need to first understand the threats to professionalism in order to guard against its erosion in ourselves and in the next generation of physicians.1

One major issue is that we do not have a common understanding of the nature of professionalism; the definition is both overused and misused. We often refer to professionalism by what it isn’t, rather than understanding what it is. For example, there are scores of definitions for “unprofessional” conduct in the medical industry, many of which refer to physician behaviors. These include actions that intimidate, berate, or bully others, regardless of the rationale or intent, and encompass any form of physical or psychological harm. The actions of the “disruptive physician” are often thought of as synonymous with unprofessional behavior. But professionalism is so much more than the absence of disruptive behavior. So part of the erosion of professionalism is an oversimplification of what it isn’t, rather than what it is.

Another issue with upholding professionalism over time is that many physicians forget their professional standards, because there are few “booster sessions” to remind us of why we practice medicine. Once we enter the workforce, we are confronted with so many obstacles to delivering good care to patients that we often feel overwhelmed or incapable of removing the real barriers to good care, and therefore incapable of fulfilling our mission. There are no regular “revivals” or checkpoints to refresh our memory of what we went into medicine to accomplish.

Although our ultimate goal is to take good care of patients, another threat to professionalism is that doing this often requires physicians to operate outside their “trained” knowledge and skill sets. It requires us to act on behalf of patients as an advocate in all aspects of their life, not just as a “diagnoser” or “prescriber.” As a result, maintaining the ideals of professionalism has become ever more complex, because the social determinants of health have a major impact on patient well-being and health, including access to food, housing, and transportation. Many times, diagnosing and prescribing have little impact on the patient’s outcome; these social determinants of disease take sole precedence. A patient’s education, income, and home environment have a much greater impact in determining their health outcomes than does access to prescription medications. This means that advocating for patient health and well-being extends far beyond the walls of a hospital or emergency room, a role in which most hospitalists are incapable and/or uncomfortable.1

Another major catalyst in the erosion of professionalism is the complex issue of money and income. Many physicians, including hospitalists, are “judged” by their relative value units, an indicator of the quantity and complexity of patients seen. Services not “billable” are generally delegated to others, or they go undone. Such services include communicating tirelessly with all the stakeholders in the patients’ care, including family members, primary care physicians, other physician specialists, and other disciplines. Untoward behaviors, such as “upcoding,” selecting funded patients for care, creating patient streams for highly lucrative services, and under-resourcing care provisions that “lose money”—regardless of the value to the patient—are inadvertently incentivized on individual and system levels to enhance revenue. Many hospitalists are strapped with student loans early in their careers, requiring them to earn enough to pay back these loans in a timely fashion. These perverse incentives can and often do confound our ability to act solely on behalf of our patients.2

How Do We Overcome These Threats?

The first step in reviving professionalism is to define it by what it is, not by what it isn’t. Professionalism is not the absence of bad behavior. Professionalism is the “commitment to carrying out professional responsibilities and an adherence to ethical principles.”3 Professionalism is the pursuit of the tenets of the Hippocratic Oath. As a litmus test, read and reread the oath, and honestly reflect upon your practice.

Another step is to continuously work in multidisciplinary teams, a skill that comes naturally to most hospitalists. In order to fulfill the oath, you should not work as a social worker, but you should advocate for your patients’ social work needs. You need a plethora of other disciplines to help you fulfill your role as a patient advocate. Know and respect the roles that your team members are playing, all of which are invaluable to you and your patients.

An additional step in helping you fulfill your role as a professional is to get the education and skills you need to function effectively within the complex systems in which we currently work. You should incorporate business and management education into your continuing medical education so that you can help patients traverse a system that is complex. You should know and understand the general concepts of value-based payment, insurance exchanges, federal-state-private insurances, and the basic tenets of health systems. You should know how to recognize and reduce waste and unnecessary variation in the system, and know how to measure and improve upon processes.

In the words of Emanuel Ezekiel, MD, PhD, “Learning clinical medicine is necessary for making patient well-being the physician’s primary obligation. But it is not sufficient. To promote professionalism and all that it entails (reducing errors; ensuring safe, consistent, high-quality, and convenient care; removing unnecessary services; and improving the efficiency in the delivery of services), physicians must develop better management skills … Becoming better managers will make physicians better medical professionals”.2

For those entering medical school, nine core competencies can predict success in medical school and later in practice; we should all commit to excellence in these, which go beyond clinical knowledge:

- ethical responsibility to self and others;

- reliability and dependability;

- service orientation;

- social skills;

- capacity for improvement;

- resilience and adaptability;

- cultural competence;

- oral communication; and

- teamwork.

Lastly, a critical step in preventing the erosion of professionalism in medicine is self-regulation. External regulation comes to those who refuse or are unwilling to regulate themselves. Professionalism is a set of skills that can be taught, learned, and modeled. As a new specialty, we all own the success or failure of the reputation of hospitalists as consummate professionals.1

Professionalism is an overused word in the medical industry. What exactly is meant by professionalism, and what should it mean to hospitalists? Wikipedia notes that a professional is one who earns a living from a specified activity that has standards of education and training that prepare members of the profession with the knowledge and skills necessary to perform the role required. In addition, professionals are subject to strict codes of conduct enshrining rigorous ethical and moral obligations.

Physicians are the consummate professionals; over centuries, we have been afforded the reputation of being one of the “highest-ranking” professionals within societies, along with divinity and law. We are held to very high standards, both in and out of the workplace, including arduous and rigorous standards of education and training. We are in one of the only professions that take the Hippocratic Oath at graduation. This oath requires us to swear to uphold specific ethical standards. Being a professional means we always act within our professional standards and advocate for our patients in all circumstances.1

Threats to Professionalism?

Over the past several decades, concern has been growing about a widespread decline in professionalism among physicians, a decline that extends beyond a single generation. There are many purported reasons for this erosion of professionalism; we need to first understand the threats to professionalism in order to guard against its erosion in ourselves and in the next generation of physicians.1

One major issue is that we do not have a common understanding of the nature of professionalism; the definition is both overused and misused. We often refer to professionalism by what it isn’t, rather than understanding what it is. For example, there are scores of definitions for “unprofessional” conduct in the medical industry, many of which refer to physician behaviors. These include actions that intimidate, berate, or bully others, regardless of the rationale or intent, and encompass any form of physical or psychological harm. The actions of the “disruptive physician” are often thought of as synonymous with unprofessional behavior. But professionalism is so much more than the absence of disruptive behavior. So part of the erosion of professionalism is an oversimplification of what it isn’t, rather than what it is.

Another issue with upholding professionalism over time is that many physicians forget their professional standards, because there are few “booster sessions” to remind us of why we practice medicine. Once we enter the workforce, we are confronted with so many obstacles to delivering good care to patients that we often feel overwhelmed or incapable of removing the real barriers to good care, and therefore incapable of fulfilling our mission. There are no regular “revivals” or checkpoints to refresh our memory of what we went into medicine to accomplish.

Although our ultimate goal is to take good care of patients, another threat to professionalism is that doing this often requires physicians to operate outside their “trained” knowledge and skill sets. It requires us to act on behalf of patients as an advocate in all aspects of their life, not just as a “diagnoser” or “prescriber.” As a result, maintaining the ideals of professionalism has become ever more complex, because the social determinants of health have a major impact on patient well-being and health, including access to food, housing, and transportation. Many times, diagnosing and prescribing have little impact on the patient’s outcome; these social determinants of disease take sole precedence. A patient’s education, income, and home environment have a much greater impact in determining their health outcomes than does access to prescription medications. This means that advocating for patient health and well-being extends far beyond the walls of a hospital or emergency room, a role in which most hospitalists are incapable and/or uncomfortable.1

Another major catalyst in the erosion of professionalism is the complex issue of money and income. Many physicians, including hospitalists, are “judged” by their relative value units, an indicator of the quantity and complexity of patients seen. Services not “billable” are generally delegated to others, or they go undone. Such services include communicating tirelessly with all the stakeholders in the patients’ care, including family members, primary care physicians, other physician specialists, and other disciplines. Untoward behaviors, such as “upcoding,” selecting funded patients for care, creating patient streams for highly lucrative services, and under-resourcing care provisions that “lose money”—regardless of the value to the patient—are inadvertently incentivized on individual and system levels to enhance revenue. Many hospitalists are strapped with student loans early in their careers, requiring them to earn enough to pay back these loans in a timely fashion. These perverse incentives can and often do confound our ability to act solely on behalf of our patients.2

How Do We Overcome These Threats?

The first step in reviving professionalism is to define it by what it is, not by what it isn’t. Professionalism is not the absence of bad behavior. Professionalism is the “commitment to carrying out professional responsibilities and an adherence to ethical principles.”3 Professionalism is the pursuit of the tenets of the Hippocratic Oath. As a litmus test, read and reread the oath, and honestly reflect upon your practice.

Another step is to continuously work in multidisciplinary teams, a skill that comes naturally to most hospitalists. In order to fulfill the oath, you should not work as a social worker, but you should advocate for your patients’ social work needs. You need a plethora of other disciplines to help you fulfill your role as a patient advocate. Know and respect the roles that your team members are playing, all of which are invaluable to you and your patients.

An additional step in helping you fulfill your role as a professional is to get the education and skills you need to function effectively within the complex systems in which we currently work. You should incorporate business and management education into your continuing medical education so that you can help patients traverse a system that is complex. You should know and understand the general concepts of value-based payment, insurance exchanges, federal-state-private insurances, and the basic tenets of health systems. You should know how to recognize and reduce waste and unnecessary variation in the system, and know how to measure and improve upon processes.

In the words of Emanuel Ezekiel, MD, PhD, “Learning clinical medicine is necessary for making patient well-being the physician’s primary obligation. But it is not sufficient. To promote professionalism and all that it entails (reducing errors; ensuring safe, consistent, high-quality, and convenient care; removing unnecessary services; and improving the efficiency in the delivery of services), physicians must develop better management skills … Becoming better managers will make physicians better medical professionals”.2

For those entering medical school, nine core competencies can predict success in medical school and later in practice; we should all commit to excellence in these, which go beyond clinical knowledge:

- ethical responsibility to self and others;

- reliability and dependability;

- service orientation;

- social skills;

- capacity for improvement;

- resilience and adaptability;

- cultural competence;

- oral communication; and

- teamwork.

Lastly, a critical step in preventing the erosion of professionalism in medicine is self-regulation. External regulation comes to those who refuse or are unwilling to regulate themselves. Professionalism is a set of skills that can be taught, learned, and modeled. As a new specialty, we all own the success or failure of the reputation of hospitalists as consummate professionals.1

Professionalism is an overused word in the medical industry. What exactly is meant by professionalism, and what should it mean to hospitalists? Wikipedia notes that a professional is one who earns a living from a specified activity that has standards of education and training that prepare members of the profession with the knowledge and skills necessary to perform the role required. In addition, professionals are subject to strict codes of conduct enshrining rigorous ethical and moral obligations.

Physicians are the consummate professionals; over centuries, we have been afforded the reputation of being one of the “highest-ranking” professionals within societies, along with divinity and law. We are held to very high standards, both in and out of the workplace, including arduous and rigorous standards of education and training. We are in one of the only professions that take the Hippocratic Oath at graduation. This oath requires us to swear to uphold specific ethical standards. Being a professional means we always act within our professional standards and advocate for our patients in all circumstances.1

Threats to Professionalism?

Over the past several decades, concern has been growing about a widespread decline in professionalism among physicians, a decline that extends beyond a single generation. There are many purported reasons for this erosion of professionalism; we need to first understand the threats to professionalism in order to guard against its erosion in ourselves and in the next generation of physicians.1

One major issue is that we do not have a common understanding of the nature of professionalism; the definition is both overused and misused. We often refer to professionalism by what it isn’t, rather than understanding what it is. For example, there are scores of definitions for “unprofessional” conduct in the medical industry, many of which refer to physician behaviors. These include actions that intimidate, berate, or bully others, regardless of the rationale or intent, and encompass any form of physical or psychological harm. The actions of the “disruptive physician” are often thought of as synonymous with unprofessional behavior. But professionalism is so much more than the absence of disruptive behavior. So part of the erosion of professionalism is an oversimplification of what it isn’t, rather than what it is.

Another issue with upholding professionalism over time is that many physicians forget their professional standards, because there are few “booster sessions” to remind us of why we practice medicine. Once we enter the workforce, we are confronted with so many obstacles to delivering good care to patients that we often feel overwhelmed or incapable of removing the real barriers to good care, and therefore incapable of fulfilling our mission. There are no regular “revivals” or checkpoints to refresh our memory of what we went into medicine to accomplish.

Although our ultimate goal is to take good care of patients, another threat to professionalism is that doing this often requires physicians to operate outside their “trained” knowledge and skill sets. It requires us to act on behalf of patients as an advocate in all aspects of their life, not just as a “diagnoser” or “prescriber.” As a result, maintaining the ideals of professionalism has become ever more complex, because the social determinants of health have a major impact on patient well-being and health, including access to food, housing, and transportation. Many times, diagnosing and prescribing have little impact on the patient’s outcome; these social determinants of disease take sole precedence. A patient’s education, income, and home environment have a much greater impact in determining their health outcomes than does access to prescription medications. This means that advocating for patient health and well-being extends far beyond the walls of a hospital or emergency room, a role in which most hospitalists are incapable and/or uncomfortable.1

Another major catalyst in the erosion of professionalism is the complex issue of money and income. Many physicians, including hospitalists, are “judged” by their relative value units, an indicator of the quantity and complexity of patients seen. Services not “billable” are generally delegated to others, or they go undone. Such services include communicating tirelessly with all the stakeholders in the patients’ care, including family members, primary care physicians, other physician specialists, and other disciplines. Untoward behaviors, such as “upcoding,” selecting funded patients for care, creating patient streams for highly lucrative services, and under-resourcing care provisions that “lose money”—regardless of the value to the patient—are inadvertently incentivized on individual and system levels to enhance revenue. Many hospitalists are strapped with student loans early in their careers, requiring them to earn enough to pay back these loans in a timely fashion. These perverse incentives can and often do confound our ability to act solely on behalf of our patients.2

How Do We Overcome These Threats?

The first step in reviving professionalism is to define it by what it is, not by what it isn’t. Professionalism is not the absence of bad behavior. Professionalism is the “commitment to carrying out professional responsibilities and an adherence to ethical principles.”3 Professionalism is the pursuit of the tenets of the Hippocratic Oath. As a litmus test, read and reread the oath, and honestly reflect upon your practice.

Another step is to continuously work in multidisciplinary teams, a skill that comes naturally to most hospitalists. In order to fulfill the oath, you should not work as a social worker, but you should advocate for your patients’ social work needs. You need a plethora of other disciplines to help you fulfill your role as a patient advocate. Know and respect the roles that your team members are playing, all of which are invaluable to you and your patients.

An additional step in helping you fulfill your role as a professional is to get the education and skills you need to function effectively within the complex systems in which we currently work. You should incorporate business and management education into your continuing medical education so that you can help patients traverse a system that is complex. You should know and understand the general concepts of value-based payment, insurance exchanges, federal-state-private insurances, and the basic tenets of health systems. You should know how to recognize and reduce waste and unnecessary variation in the system, and know how to measure and improve upon processes.

In the words of Emanuel Ezekiel, MD, PhD, “Learning clinical medicine is necessary for making patient well-being the physician’s primary obligation. But it is not sufficient. To promote professionalism and all that it entails (reducing errors; ensuring safe, consistent, high-quality, and convenient care; removing unnecessary services; and improving the efficiency in the delivery of services), physicians must develop better management skills … Becoming better managers will make physicians better medical professionals”.2

For those entering medical school, nine core competencies can predict success in medical school and later in practice; we should all commit to excellence in these, which go beyond clinical knowledge:

- ethical responsibility to self and others;

- reliability and dependability;

- service orientation;

- social skills;

- capacity for improvement;

- resilience and adaptability;

- cultural competence;

- oral communication; and

- teamwork.

Lastly, a critical step in preventing the erosion of professionalism in medicine is self-regulation. External regulation comes to those who refuse or are unwilling to regulate themselves. Professionalism is a set of skills that can be taught, learned, and modeled. As a new specialty, we all own the success or failure of the reputation of hospitalists as consummate professionals.1

Hospitalists Should Embrace Advances, Transparency in Health Record Technology

We are definitely in the era of data access and transparency. These days you can find information on anything and everything within a matter of seconds. You can become a subject matter expert on any topic within a matter of hours: music, cooking, foreign language, weather, travel. The possibilities are endless. That is, unless you want information on yourself—specifically, medical information.

Despite all of our advances in technology in the information era, many patients still find it extremely difficult and frustrating to gain full and transparent access to their medical records. Electronic health records (EHRs) have made it easier than ever for practitioners to find information about their patients, including pharmacy and access queries to determine what medications they are (or are not) taking, and where they have recently accessed care. But EHRs have not been widely utilized as a tool to grant extensive, real-time access to patients.

But change is afoot. Both providers and patients are now realizing the value of offering patients more open access to their medical records. Many organizations with EHRs have created patient portals, where patients can access limited portions of their medical records such as medications and allergies, can request items such as prescription refills or appointments, and can ask their providers about their care. Some medical centers are participating in OpenNotes initiatives, which give patients direct access to provider notes within the medical record.

Although these patient portals are a great first step in transparency and engagement, the information granted to patients is limited in content and timeliness. Generally, such items as test results must first be “released” by a provider before they can be viewed by the patient; some organizations have set restrictions, determining that some tests cannot be released at all (i.e., abnormal pathology or HIV test results). The rationale for such restrictions is to prevent patients from finding out sensitive information from a web page; many assume that the patient would be much better off finding out such information from a provider than a computer, and that well may be true, if the information is available in a timely fashion and is shared by a provider who can relay the information better than a computer.

Barriers Aplenty

The medical industry still has a long way to go to realize full medical record transparency for patients. One legitimate barrier is that medical records were never intended for patient view or use. Most do not read like a story; they read more like a ledger, full of medical jargon and text boxes in illogical order. This is primarily due to the fact that EHRs were designed for regulatory and billing purposes, not to eloquently—or even adequately—summarize what the patient is (or was) experiencing.

Another major barrier is that the information in the medical record is often difficult to find, and the record itself is difficult to maneuver. Experienced and trained providers, even those who have dutifully completed medical training, often find it challenging to locate exactly what they are looking for. The burden would be on the patient to learn, understand, and navigate the medical record, and few would likely undertake such a challenge.

There also are legitimate cultural barriers among providers, who will resist giving patients carte blanche access to the EHR; many providers cite concerns that if they honestly summarize sensitive information in the medical record (i.e., social habits or medication compliance issues), patients may be angered, with resultant loss of trust, retaliation, or legal action.

Clear the Hurdles, and Next Steps

There is a great story about how well medical record transparency can work, summarized in a New York Times article a few months ago.1 The story tells of 26-year-old Steven Keating, who had a “slight abnormality” on a brain CT that was done in 2007 as part of a study he had volunteered for.2 Although reassured by a “normal” follow-up scan in 2010, Keating was inquisitive, wanting to understand everything about his condition, and read voraciously about what his initial brain scan could mean. He knew the initial abnormality was near his olfactory nerve, so in 2014, when he started intermittently smelling vinegar, he suspected it might be related to the abnormality noted in his initial scan.

He sought immediate care and follow-up imaging, which showed a very large mass. Within weeks, this large astrocytoma was successfully removed; surgery was followed by chemotherapy and radiation.