User login

Obstetric anal sphincter injury: How to avoid, how to repair: A literature review

- Avoiding obstetrical injury to the anal sphincter is the single biggest factor in preventing anal incontinence among women (A). Any form of instrument delivery has consistently been noted to increase the risk of obstetric anal sphincter injury and altered fecal continence by between 2- and 7-fold (A).

- Routine episiotomy is not recommended (A). Episiotomy use should be restricted to situations where it directly facilitates an urgent delivery (A). A mediolateral incision, instead of a midline, should be considered for persons at otherwise high risk of obstetric anal sphincter injury (A).

- The internal anal sphincter needs to be separately repaired if torn (A).

- Women with injuries to the internal anal sphincter or rectal mucosa have a worse prognosis for future continence problems (A). All women, particularly those with risk factors for injury, should be surveyed for symptoms of anal incontinence at postpartum follow-up (C).

Do you routinely check with new first-time mothers at a postpartum visit about changes in anal continence? They are at particular risk for obstetric anal sphincter injury and could be too embarrassed to raise the issue.

Sphincter injury following labor is the most common cause of anal incontinence (including flatus) in women, which can severely diminish quality of life and lead to considerable personal and financial costs.1 Endoanal ultrasound can detect these injuries, even in the absence of clinically obvious damage to the anal sphincter (occult obstetric anal sphincter injury).2

In this article, we review measures to reduce the occurrence of obstetric anal sphincter injury, proper primary repair when it does occur, and appropriate long-term follow-up. Women with known obstetric anal sphincter injury must also be counseled about the risk of further damage during a future vaginal delivery.

Injury more common than symptoms would suggest

The conventional definitions of the 4 grades of perineal laceration in the US have been supplemented by more recent modifications included in a recent British Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) guideline (TABLE 1).3 The definition of third-degree laceration now reflects the various degrees of anal sphincter injury that may occur: partial (3a), full-thickness (3b), external anal sphincter injury, with or without injury to the internal anal sphincter (3c).

The incidence of clinical third- and fourth-degree lacerations varies widely; it is reported at between 0.5% and 3.0% in Europe and between 5.85% and 8.9% in the US.2,4-6 A landmark British paper from 1993 revealed that though only 3% had a clinical third- or fourth-degree perineal laceration, 35% of primiparous women (none of whom had any defect before delivery) had ultrasound evidence of varying degrees of anal sphincter defect at 6 weeks postpartum that persisted at 6 months.2 However, only about a third of these women had symptoms of bowel disturbance during the time of study.

These findings are supported by a meta-analysis in which 70% of women with a documented obstetric anal sphincter injury were asymptomatic.7 This meta-analysis concluded that clinical or occult obstetric anal sphincter injury occurs in 27% of primigravid women, and in 8.5% of multiparous women.

The long-term significance of occult obstetric anal sphincter injury and any relationship with geriatric fecal incontinence is unknown, although 71% of a sample of women with late-onset fecal incontinence were found to have ultrasound evidence of an anal sphincter defect thought to have occurred at a previous vaginal delivery.8 A recent English study9 reveals that when women were carefully re-examined after delivery by a skilled obstetrician looking specifically at the anal sphincter, the prevalence of clinically diagnosed third-degree lacerations rose sharply from the 11% initially diagnosed by the delivering physician or midwife to 24.5%. A subsequent endoanal ultrasound detected only an additional 1.2% (3 injuries, 2 of which were in the internal anal sphincter and therefore clinically undetectable). This strongly suggests that the vast majority of obstetric anal sphincter injuries can be detected clinically by a careful exam and that, when this is done, true occult injuries will be a rare finding.

TABLE 1

Classification of perineal injury9

| INJURY | DEFINITION |

|---|---|

| First degree | Injury confined to vaginal mucosa |

| Second degree | Injury of vaginal mucosa and perineal muscles, but not the anal sphincter |

| Third degree | Injury to the perineum involving the anal sphincter complex (external and internal) |

| 3a | <50% of external sphincter thickness is torn |

| 3b | >50% of external sphincter thickness is torn |

| 3c | Internal sphincter is torn |

| Fourth degree | Injury to external and internal sphincter and rectal mucosa/anal epithelium |

Mechanisms of injury

Maintenance of fecal continence involves the coordinated action of several anatomical and physiological elements (FIGURE 1).10 An intact, innervated anal sphincter complex (both external and internal) is necessary. The sphincter complex can be damaged during childbirth in 3 ways.

Direct mechanical injury. Direct external or internal anal sphincter muscle disruption can occur, as with a clinically obvious third- or fourth-degree perineal laceration or an occult injury subsequently noted on ultrasound.

Neurologic injury. Neuropathy of the pudendal nerve may result from forceps delivery or persistent nerve compression from the fetal head.14 Traction neuropathy may also occur with fetal macrosomia and with prolonged pushing during Stage 2 in successive pregnancies, or with prolonged stretching of the nerve due to persistent poor postpartum pelvic floor tone. Injured nerves often undergo demyelination but usually recover with time.

Combined mechanical and neurologic trauma. Isolated neurologic injury, as described above, is believed to be rare. Neuropathy more commonly accompanies mechanical damage.15

Who is at risk?

Several risk factors are unavoidable. One of these is primiparity, a consistently reported independent variable also associated with other risk factors for obstetric anal sphincter injury, such as instrument delivery (TABLE 2).

TABLE 2

Major risk factors for obstetric anal sphincter injury

| RISK FACTOR | ODDS RATIO |

|---|---|

| Nulliparity (primigravidity) | 3–4 |

| Inherent predisposition: | |

| Short perineal body | 8 |

| Instrumental delivery, overall | 3 |

| Forceps-assisted delivery | 3–7 |

| Vacuum-assisted delivery | 3 |

| Forceps vs vacuum | 2.88* |

| Forceps with midline episiotomy | 25 |

| Prolonged second stage of labor (>1 hour) | 1.5–4 |

| Epidural analgesia | 1.5–3 |

| Intrapartum infant factors: | |

| Birthweight over 4 kg | 2 |

| Persistent occipitoposterior position | 2–3 |

| Episiotomy, mediolateral | 1.4 |

| Episiotomy, midline | 3–5 |

| Previous anal sphincter tear | 4 |

| All variables are statistically significant at P<.05. | |

| *Relative risk of altered fecal symptoms based on RCT findings, vacuum vs forceps.17 Data from randomized controlled trials are lacking for most labor variables. Due to differing methods of analysis (univariate vs regression) and outcome measures, risk ratios reported in the literature vary considerably. This table presents the approximate odds ratios for risk factors that have been reported most consistently from 1 prospective cohort study,16 1 randomized controlled trial,14 and, otherwise higher-quality retrospective analyses.18-23 | |

Preventing obstetric anal sphincter injury

Sphincter injury can occur even when obstetrical management is optimal. Although evidence from RCT data is often lacking, sufficient observational and retrospective data support the following recommendations to reduce the likelihood of injury.

Choose vacuum delivery before forceps

Any form of instrument delivery increases the risk of obstetric anal sphincter injury and altered fecal continence by between 2- and 7-fold.2,16,24 An RCT found clinical third-degree tears in 16% of women with forceps-assisted deliveries, compared with 7% of vacuum-assisted deliveries; the authors concluded that, when circumstances allow, vacuum delivery should be attempted first (acknowledging however that 23% of vacuum deliveries failed and proceeded to a forceps extraction, a sequence associated with increased injury).17 A meta-analysis confirmed that vacuum extraction is preferred when instrumental delivery is necessary (SOR: A).25

When midline episiotomy was performed during instrument delivery, the risk of obstetric anal sphincter injury approximately doubled again, such that, in one study, forceps delivery with episiotomy caused a 25-fold increase in obstetric anal sphincter injury.24

Any steps that may safely reduce the need for instrument delivery should be supported. Toward this end, the Canadian Clinical Practices Obstetrics committee has recommended evidence-based labor interventions such as one-to-one support in labor, the increased use of a partogram in labor and appropriate oxytocin use, all in an effort to reduce needs for operative interventions.26

If episiotomy necessary, mediolateral less risky than midline

Episiotomy was long promoted as a means of preserving the integrity of the perineal musculature and of avoiding damage to the anal sphincter, and it has been practiced routinely by some.27 Strong evidence now indicates that routine episiotomy (midline or mediolateral) is unhelpful and should be abandoned.25,27-29

Observational evidence overwhelmingly shows that midline episiotomy is strongly associated with obstetric anal sphincter injury.19,22,23,30,31 One of the few RCTs comparing midline with mediolateral episiotomy, although flawed in its design, noted that a clinical third-degree laceration occurred as an extension of episiotomy in 11.6% of midline incisions compared with just 2% of mediolateral cuts.32

Another RCT, designed to examine routine versus restrictive episiotomy, noted that all but 1 (98%) of the 47 third- or fourth-degree lacerations in a group of 700 women followed midline episiotomy.29 A retrospective database analysis noted a 6-fold higher risk of third-degree perineal lacerations for women undergoing midline episiotomy compared with mediolateral incision.23 Elsewhere, midline episiotomy was associated with a 5-fold increase in symptoms of fecal incontinence at 3 months postpartum when compared with women with an intact perineum.24

Even when midline episiotomies do not extend into clinical third-degree lacerations, the incidence of resultant postpartum fecal incontinence triples when compared with spontaneous second-degree perineal lacerations.30 The authors postulate that a perineum cut by midline episiotomy allows for more direct contact to occur between the fetal hard parts and the anal sphincter complex during delivery, thereby increasing occult obstetric anal sphincter injury.

Observational data conflict as to whether mediolateral episiotomy contributes to, or protects against, obstetric anal sphincter injury—although the burden of evidence favors it as a risk factor that should be avoided when possible.16,23,33 An angle of mediolateral incision cut closer to 45 degrees from the midline has been associated with less obstetric anal sphincter injury than incisions cut at closer angles to the midline.34

Repairing sphincter injury

Detecting injury in labor

With any severe perineal laceration, closely inspect the external and, if exposed, internal anal sphincter and perform a rectal exam, particularly for women with numerous risk factors (although no good evidence supports the role of the rectal exam in diagnosing obstetric anal sphincter injury). Colorectal surgeons have advocated the use of a muscle stimulator to assist in identifying the ends of the external sphincter, but this has not become common practice.35

Immediate vs delayed repair

It is standard practice to repair a damaged anal sphincter immediately or soon after delivery. However, given that a repair should be well done, and since a short delay does not appear to adversely affect healing, be prepared to wait for assistance for up to 24 hours rather than risk a suboptimal repair.36

Better training is needed

Even among trained obstetricians and obgyn residents, 64% have reported no training or unsatisfactory training in management of obstetric anal sphincter injury; 94% of physicians felt inadequately prepared at the time of their first independent repair of the anal sphincter.37,38 To improve your repair skills in a workshop setting, consult the following sources—www.aafp.org/also.xml in the US, or www.perineum.net in UK.

Analgesia and setting

Adequate analgesia is an essential element in a good repair. Complete relaxation of the anesthetized anal sphincter complex facilitates bringing torn ends of the sphincter together without tension.39 Though theoretically this can be attained with local anesthetic infiltration, RCOG recommends that regional or general anesthesia be considered to provide complete analgesia.37 It is further recommended that repair of the anal sphincter occur in an operating room, given the degree of contamination present in the labor room after delivery and the devastating effects of an infected repair (SOR: C).40

Repair technique

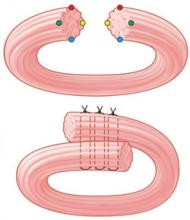

There are 2 commonly used methods of external anal sphincter repair: one, the traditionally taught end-to-end approximation of the cut ends, and the other, overlapping the cut ends of the external sphincter and suturing through the overlapped portions (FIGURE 2).36 Though an RCT from 2000 noted no significant difference in outcomes between these methods,41 other authors have suggested that an overlapping technique is preferred, and it remains the method most often used by colorectal surgeons in elective, secondary anal sphincter repairs.36,39,42

A Cochrane review of which technique is better has been registered in the Clinical Trials Database. General agreement is that closure using interrupted sutures of a monofilament material, such as 2-0 polydioxanone sulfate (PDS), is the preferred closure method for the external sphincter (SOR: C).36,40 It is recommended that a damaged internal sphincter be repaired with a running continuous suture of a material such as 2-0 polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) (SOR: C).36

FIGURE 2

2 methods of anal sphincter repair

Two commonly used methods of external anal sphincter repair are end-to-end approximate of the cut ends (top), and overlapping the cut ends and suturing through the overlapped portions (bottom). (Adapted from Leeman et al, Am Fam Physician 2003.33) ILLUSTRATION BY RICH LaROCCO

Immediate post-repair management

Use a stool softener

It had long been thought that constipation following obstetric anal sphincter injury allowed the sphincter to heal more effectively. However, new evidence from RCTs shows that using a laxative instead of a constipating regimen is more helpful in the immediate postpartum phase.43 Toward this end, use a stool softener, such as lactulose, for 3 to 10 days postpartum for women with obstetric anal sphincter injury.40

Should you prescribe an antibiotic?

Given the devastating effects of post-repair infection, most authorities consider it prudent to prescribe a course of broad-spectrum antibiotics, possibly including metronidazole (SOR: C)37,40 A Cochrane review is registered to further examine this issue. A separate Cochrane review of the use of antibiotics for instrument vaginal delivery concluded that quality data were insufficient to make any recommendations.44

Refer for physical therapy

Some authorities consider an early referral to physical therapy for pelvic floor exercises helpful in the immediate post-partum for all patients with obstetric anal sphincter injury (SOR: C).45

Long-term management

Ask patients about incontinence

Given that some women are too embarrassed to seek assistance, ask those with obstetric anal sphincter injury specific questions about any symptoms of anal incontinence at a follow-up visit, such as the 6-week postpartum visit (SOR: C).37,40 In some practices, all women who have sustained a third- or fourth-degree laceration are routinely scheduled for a 3-month follow-up visit to a dedicated clinic, irrespective of symptoms. Given the prevalence of occult obstetric anal sphincter injury for primigravid women, you may find it best to survey all women postnatally concerning any changes in anal continence. TABLE 3 demonstrates a validated, modified patient survey of anal incontinence.37,40 A score of 6 is often used as a cutoff.

TABLE 3

Fecal Continence Scoring scale

| SYMPTOM |

| 1. Passage of any flatus when socially undesirable |

| 2. Any incontinence of liquid stool |

| 3. Any need to wear a pad because of anal symptoms |

| 4. Any incontinence of solid stool |

| 5. Any fecal urgency (inability to defer defecation for more than 5 minutes) |

| SCALE |

| 0 Never |

| 1 Rarely (<1/month) |

| 2 Sometimes (1/week–1/month |

| 3 Usually (1/day–1/week) |

| 4 Always (>1/day) |

| A score of 0 implies complete continence and a score of 20 complete incontinence. |

| A score of 6 has been suggested as a cut-off to determine need for evaluation. |

| Source: Mahony et al, 2001;43 modified from Jorge and Wexner, 1993.44 |

When additional evaluation is needed

Patients who have symptoms of altered continence at 3 months (or who score above 6 on the Wexner scale) should be seen at a dedicated gynecologic or colorectal surgery clinic,46 where they can receive a more detailed clinical evaluation and undergo anal manometry (during resting and forced squeezing) or endoanal ultrasonography. Some patients respond well to physical therapy, though a few patients ultimately require reconstructive colorectal surgery and temporary colostomy.

Management in a subsequent pregnancy

Women who have had an obstetric anal sphincter injury are at increased risk for repeat injury in a future pregnancy.48 At some units, all such women are routinely offered a prenatal visit at the end of the second trimester to review their symptoms and to evaluate the anal sphincter with manometry or ultrasound. A large prospective study, however, found that recurrence of obstetric anal sphincter injury could not be predicted and that 95% of women with prior injury did not sustain further overt sphincter damage during a subsequent vaginal delivery.49

However, for some women, a repeat anal sphincter laceration could prove devastating. For these women—eg, those with previous severe symptoms that required secondary surgical repair—initiate an in-depth discussion concerning the risks and benefits of elective cesarean delivery versus vaginal delivery.37,40

Historically, fecal incontinence was defined as “the involuntary or inappropriate passage of feces.”10 However, a preferred definition now refers instead to anal incontinence, which is “any involuntary loss of feces or flatus, or urge incontinence, that is adversely affecting a woman’s quality of life.”40 This definition includes urgency of defecation and incontinence of flatus, both of which are much more common symptoms than fecal incontinence.50

Data are lacking on the community prevalence of incontinence, although it is known that women of age 45 experience 8 times the incidence of incontinence as men of the same age and that it increases in prevalence with age.10 A Canadian survey of almost 1000 women at 3 months postpartum revealed that 3.1% admitted to incontinence of feces while 25% admitted to involuntary escape of flatus. The subgroup of women who suffered clinical anal sphincter injury (that is, third- or fourth-degree lacerations) had considerably increased rates of incontinence of feces (7.8%) and of flatus (48%).24 It has been reported that approximately half of women who sustained anal sphincter tears in labor complained of anal, urinary, or perineal symptoms at a mean follow-up of 2.6 years after the injury.51 Most studies agree that many women are embarrassed about symptoms of anal incontinence and are reluctant to self-report them.50

CORRESPONDENCE

David Power, MD, MPH, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Minnesota, Mayo Mail Code 381, 516 Delaware St SE, Minneapolis, MN 55455. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Mellgren A, Jensen LL, Zetterstrom JP, Wong WD, Hofmeister JH, Lowry AC. Long-term cost of fecal incontinence secondary to obstetric injuries. Dis Colon Rectum 1999;42:857-865.

2. Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN, Thomas JM, Bartram CI. Anal-sphincter disruption during vaginal delivery. N Engl J Med 1993;329:1905-1911.

3. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Methods and Materials used in Perineal Repair. Guideline No. 23. London: RCOG Press; 2004.

4. Fitzpatrick M, Behan M, O’Connell PR, O’Herlihy C. A randomized clinical trial comparing primary overlap with approximation repair of third-degree obstetric tears. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000;183:1220-1224.

5. Simhan HN, Krohn MA, Heine RP. Obstetric rectal injury: risk factors and the role of physician experience. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2004;16:271-274.

6. Handa VL, Danielsen BH, Gilbert WM. Obstetric anal sphincter lacerations. Obstet Gynecol 2001;98:225-230.

7. Oberwalder M, Connor J, Wexner SD. Meta-analysis to determine the incidence of obstetric anal sphincter damage. Br J Surg 2003;90:1333-1337.

8. Oberwalder M, Dinnewitzer A, Baig MK, et al. The association between late-onset fecal incontinence and obstetric anal sphincter defects. Arch Surg 2004;139:429-432.

9. Andrews V, Sultan AH, Thakar R, Jones PW. Occult anal sphincter injuries-myth or reality? BJOG 2006;113:195-200.

10. Sultan AH, Nugent K. Pathophysiology and nonsurgical treatment of anal incontinence. BJOG 2004;111 (Suppl 1):84-90.

11. Schafer A, Enck P, Furst G, et al. Anatomy of the anal sphincters. Dis Colon Rectum 1994;37:777-781.

12. Mahony R, Daly L, Behan M, Kirwan C, O’Herlihy C, O’Connell R. Internal Anal Sphincter injury predicts continence outcome following obstetric sphincter trauma. AJOG 2004;191:6s1-s89.

13. Bartram CL, Frudringer A. Handbook of Anal Endosonography. Petersfield, UK: Wrightson Biomedical Publishing; 1997.

14. Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN. Pudendal nerve damage during labor: prospective study before and after childbirth. BJOG 1994;101:22-28.

15. Snooks SJ, Henry MM, Swash M. Fecal incontinence due to external anal sphincter division in childbirth is associated with damage to the innervation of the pelvic floor musculature: a double pathology. BJOG 1985;92:824-828.

16. Donnelly V, Fynes M, Campbell D, Johnson H, O’Connell PR, O’Herlihy C. Obstetric events leading to anal sphincter damage. Obstet Gynecol 1998;92:955-961.

17. Fitzpatrick M, Behan M, O’Connell PR, O’Herlihy C. Randomized clinical trial to assess anal sphincter function following forceps or vacuum assisted vaginal delivery. BJOG 2003;110:424-429.

18. Deering SH, Carlson N, Stitely M, Allaire AD, Satin AJ. Perineal body length and lacerations at delivery. J Reproductive Medicine 2004;49:306-310.

19. Goldberg J, Hyslop T, Tolosa JE, Sultana C. Racial Differences in severe Perineal lacerations after vaginal delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;188:1063-1067.

20. Robinson JN, Norwitz ER, Cohen AP, McElrath TF, Lieberman ES. Epidural analgesia and third- or fourth-degree lacerations in nulliparas. Obstet Gynecol 1999;94:259-262.

21. Carroll TG, Engelken M, Mosier MC, Nazir N. Epidural analgesia and severe perineal laceration in a community-based obstetric practice. J Am Board Fam Prac 2003;16:1-6.

22. Riskin-Mashiah S, O’Brian Smith E, Wilkins IA. Risk factors for severe perineal tear: can we do better? Am J Perinatol 2002;19:225-234.

23. Bodner-Adler B, Bodner K, Kaider A, et al. Risk factors for third-degree perineal tears in vaginal deliveries with an analysis of episiotomy types. J Reprod Med 2001;46:752-756.

24. Eason E, Labrecque M, Marcoux S, Mondor M. Anal incontinence after childbirth. CMAJ 2002;166:326-330.

25. Eason E, Labrecque M, Wells G, Feldman P. Preventing perineal trauma during childbirth: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 2000;95:464-471.

26. Cargill YM, MacKinnon CJ, Arsensault MY, et al. Clinical Practice Obstetrics Committee. Guidelines for operative vaginal birth. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2004;26:747-761.

27. Carroli G, Belizan J. Episiotomy for vaginal birth. Cochrane Database System Rev 1999;(3):CD000081.-

28. Schlomer G, Gross M, Meyer G. Effectiveness of liberal vs. conservative episiotomy in vaginal delivery with reference to preventing urinary and fecal incontinence: a systematic review [in German]. Wien Med Wochenschr 2003;153:269-275.

29. Klein MC, Gauthier RJ, Jorgensen SH, et al. Does episiotomy prevent perineal trauma and pelvic floor relaxation? Online J Curr Clin Trials 1992;Doc No 10.

30. Signorello LB, Harlow BL, Chekos AK, Repke JT. Midline episiotomy and anal incontinence: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2000;320:86-90.

31. Shiono P, Klebanoff MA, Carey JC. Midline episiotomies: more harm than good? Obstet Gynecol 1990;75:765-770.

32. Coats PM, Chan KK, Wilkins M, Beard RJ. A comparison between midline and mediolateral episiotomies. BJOG 1980;87:408-412.

33. Poen AC, Felt-Bersma RJ, Dekker GA, Deville W, Cuesta MA, Meuwissen SG. Third degree obstetric perineal tears: risk factors and the preventive role of mediolateral episiotomy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1997;104:563-566.

34. Eogan M, O’Connell R, O’Herlihy C. Does the angle of episiotomy affect the incidence of anal sphincter injury? BJOG 2006;113:190-194.

35. Cook TA, Keane D, Mortensen NJ. Is there a role for the colorectal team in the management of acute severe third-degree vaginal tears? Colorectal Dis 1999;1:263-266.

36. Leeman L, Spearman M, Rogers R. Repair of obstetric perineal lacerations. Am Fam Physician 2003;68:1585-1590.

37. Fernando RJ, Sultan AH, Radley S, Jones PW, Johanson RB. Management of obstetric anal sphincter injury: a systematic review & national practice survey. BMC Health Serv Res 2002;2:9.-

38. Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN. Obstetric perineal trauma: an audit of training. J Obstet Gynaecol 1995;15:19-23.

39. Sultan AH, Monga AK, Kumar D, Stanton SL. Primary repair of obstetric anal sphincter rupture using the overlap technique. BJOG 1999;106:318-23.

40. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Management of third- and fourth-degree perineal tears following vaginal delivery. Guideline No. 29. London: RCOG Press; 2001.

41. Fitzpatrick M, Behan M, O’Connell PR, O’Herlihy C. A randomised clinical trial comparing primary overlap with approximation repair of third degree tears. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000;183:1220-1224.

42. Kairaluoma MV, Raivio P, Aarnio MT, Kellokumpo IH. Immediate repair of obstetric anal sphincter rupture: medium-term outcome of the overlap technique. Dis Colon Rectum 2004;47:1358-1363.

43. Mahony R, Behan M, O’Herlihy C, O’Connell PR. Randomized, clinical trial of bowel confinement vs. laxative use after primary repair of a third-degree obstetric anal sphincter tear. Dis Colon Rectum 2004;47:12-17.

44. Liabsuetrakul T, Choobun T, Peeyananjarassri K, Islam M. Antibiotic prophylaxis for operative vaginal delivery (Cochrane review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 2, 2004.

45. Fitzpatrick M, O’Herlihy C. Postpartum anal sphincter dysfunction. Current Obstet Gynaecol 1999;9:210-215.

46. Mahony R, O’Brien C, O’Herlihy C. Evaluation of obstetric anal sphincter injury. Reviews in Gynaecological Practice 2001;1:114-121.

47. Jorge M, Wexner S. Etiology and management of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 1993;36:77-97.

48. Fynes M, Donnelly V, Behan M, O’Connell PR, O’Herlihy C. Effect of second vaginal delivery on anorectal physiology and faecal continence: a prospective study. Lancet 1999;354:983-986.

49. Harkin R, Fitzpatrick M, O’Connell PR, O’Herlihy C. Anal sphincter disruption at vaginal deliver: is recurrence predictable? Eur J Obstet Gynaecol 2003;109:149-152.

50. Fitzpatrick M, O’Herlihy C. The effects of labour and delivery on the pelvic floor. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2001;15:63-79.

51. Wood J, Amos L, Rieger N. Third degree anal sphincter tears: risk factors and outcome. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 1998;38:414-417.

- Avoiding obstetrical injury to the anal sphincter is the single biggest factor in preventing anal incontinence among women (A). Any form of instrument delivery has consistently been noted to increase the risk of obstetric anal sphincter injury and altered fecal continence by between 2- and 7-fold (A).

- Routine episiotomy is not recommended (A). Episiotomy use should be restricted to situations where it directly facilitates an urgent delivery (A). A mediolateral incision, instead of a midline, should be considered for persons at otherwise high risk of obstetric anal sphincter injury (A).

- The internal anal sphincter needs to be separately repaired if torn (A).

- Women with injuries to the internal anal sphincter or rectal mucosa have a worse prognosis for future continence problems (A). All women, particularly those with risk factors for injury, should be surveyed for symptoms of anal incontinence at postpartum follow-up (C).

Do you routinely check with new first-time mothers at a postpartum visit about changes in anal continence? They are at particular risk for obstetric anal sphincter injury and could be too embarrassed to raise the issue.

Sphincter injury following labor is the most common cause of anal incontinence (including flatus) in women, which can severely diminish quality of life and lead to considerable personal and financial costs.1 Endoanal ultrasound can detect these injuries, even in the absence of clinically obvious damage to the anal sphincter (occult obstetric anal sphincter injury).2

In this article, we review measures to reduce the occurrence of obstetric anal sphincter injury, proper primary repair when it does occur, and appropriate long-term follow-up. Women with known obstetric anal sphincter injury must also be counseled about the risk of further damage during a future vaginal delivery.

Injury more common than symptoms would suggest

The conventional definitions of the 4 grades of perineal laceration in the US have been supplemented by more recent modifications included in a recent British Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) guideline (TABLE 1).3 The definition of third-degree laceration now reflects the various degrees of anal sphincter injury that may occur: partial (3a), full-thickness (3b), external anal sphincter injury, with or without injury to the internal anal sphincter (3c).

The incidence of clinical third- and fourth-degree lacerations varies widely; it is reported at between 0.5% and 3.0% in Europe and between 5.85% and 8.9% in the US.2,4-6 A landmark British paper from 1993 revealed that though only 3% had a clinical third- or fourth-degree perineal laceration, 35% of primiparous women (none of whom had any defect before delivery) had ultrasound evidence of varying degrees of anal sphincter defect at 6 weeks postpartum that persisted at 6 months.2 However, only about a third of these women had symptoms of bowel disturbance during the time of study.

These findings are supported by a meta-analysis in which 70% of women with a documented obstetric anal sphincter injury were asymptomatic.7 This meta-analysis concluded that clinical or occult obstetric anal sphincter injury occurs in 27% of primigravid women, and in 8.5% of multiparous women.

The long-term significance of occult obstetric anal sphincter injury and any relationship with geriatric fecal incontinence is unknown, although 71% of a sample of women with late-onset fecal incontinence were found to have ultrasound evidence of an anal sphincter defect thought to have occurred at a previous vaginal delivery.8 A recent English study9 reveals that when women were carefully re-examined after delivery by a skilled obstetrician looking specifically at the anal sphincter, the prevalence of clinically diagnosed third-degree lacerations rose sharply from the 11% initially diagnosed by the delivering physician or midwife to 24.5%. A subsequent endoanal ultrasound detected only an additional 1.2% (3 injuries, 2 of which were in the internal anal sphincter and therefore clinically undetectable). This strongly suggests that the vast majority of obstetric anal sphincter injuries can be detected clinically by a careful exam and that, when this is done, true occult injuries will be a rare finding.

TABLE 1

Classification of perineal injury9

| INJURY | DEFINITION |

|---|---|

| First degree | Injury confined to vaginal mucosa |

| Second degree | Injury of vaginal mucosa and perineal muscles, but not the anal sphincter |

| Third degree | Injury to the perineum involving the anal sphincter complex (external and internal) |

| 3a | <50% of external sphincter thickness is torn |

| 3b | >50% of external sphincter thickness is torn |

| 3c | Internal sphincter is torn |

| Fourth degree | Injury to external and internal sphincter and rectal mucosa/anal epithelium |

Mechanisms of injury

Maintenance of fecal continence involves the coordinated action of several anatomical and physiological elements (FIGURE 1).10 An intact, innervated anal sphincter complex (both external and internal) is necessary. The sphincter complex can be damaged during childbirth in 3 ways.

Direct mechanical injury. Direct external or internal anal sphincter muscle disruption can occur, as with a clinically obvious third- or fourth-degree perineal laceration or an occult injury subsequently noted on ultrasound.

Neurologic injury. Neuropathy of the pudendal nerve may result from forceps delivery or persistent nerve compression from the fetal head.14 Traction neuropathy may also occur with fetal macrosomia and with prolonged pushing during Stage 2 in successive pregnancies, or with prolonged stretching of the nerve due to persistent poor postpartum pelvic floor tone. Injured nerves often undergo demyelination but usually recover with time.

Combined mechanical and neurologic trauma. Isolated neurologic injury, as described above, is believed to be rare. Neuropathy more commonly accompanies mechanical damage.15

Who is at risk?

Several risk factors are unavoidable. One of these is primiparity, a consistently reported independent variable also associated with other risk factors for obstetric anal sphincter injury, such as instrument delivery (TABLE 2).

TABLE 2

Major risk factors for obstetric anal sphincter injury

| RISK FACTOR | ODDS RATIO |

|---|---|

| Nulliparity (primigravidity) | 3–4 |

| Inherent predisposition: | |

| Short perineal body | 8 |

| Instrumental delivery, overall | 3 |

| Forceps-assisted delivery | 3–7 |

| Vacuum-assisted delivery | 3 |

| Forceps vs vacuum | 2.88* |

| Forceps with midline episiotomy | 25 |

| Prolonged second stage of labor (>1 hour) | 1.5–4 |

| Epidural analgesia | 1.5–3 |

| Intrapartum infant factors: | |

| Birthweight over 4 kg | 2 |

| Persistent occipitoposterior position | 2–3 |

| Episiotomy, mediolateral | 1.4 |

| Episiotomy, midline | 3–5 |

| Previous anal sphincter tear | 4 |

| All variables are statistically significant at P<.05. | |

| *Relative risk of altered fecal symptoms based on RCT findings, vacuum vs forceps.17 Data from randomized controlled trials are lacking for most labor variables. Due to differing methods of analysis (univariate vs regression) and outcome measures, risk ratios reported in the literature vary considerably. This table presents the approximate odds ratios for risk factors that have been reported most consistently from 1 prospective cohort study,16 1 randomized controlled trial,14 and, otherwise higher-quality retrospective analyses.18-23 | |

Preventing obstetric anal sphincter injury

Sphincter injury can occur even when obstetrical management is optimal. Although evidence from RCT data is often lacking, sufficient observational and retrospective data support the following recommendations to reduce the likelihood of injury.

Choose vacuum delivery before forceps

Any form of instrument delivery increases the risk of obstetric anal sphincter injury and altered fecal continence by between 2- and 7-fold.2,16,24 An RCT found clinical third-degree tears in 16% of women with forceps-assisted deliveries, compared with 7% of vacuum-assisted deliveries; the authors concluded that, when circumstances allow, vacuum delivery should be attempted first (acknowledging however that 23% of vacuum deliveries failed and proceeded to a forceps extraction, a sequence associated with increased injury).17 A meta-analysis confirmed that vacuum extraction is preferred when instrumental delivery is necessary (SOR: A).25

When midline episiotomy was performed during instrument delivery, the risk of obstetric anal sphincter injury approximately doubled again, such that, in one study, forceps delivery with episiotomy caused a 25-fold increase in obstetric anal sphincter injury.24

Any steps that may safely reduce the need for instrument delivery should be supported. Toward this end, the Canadian Clinical Practices Obstetrics committee has recommended evidence-based labor interventions such as one-to-one support in labor, the increased use of a partogram in labor and appropriate oxytocin use, all in an effort to reduce needs for operative interventions.26

If episiotomy necessary, mediolateral less risky than midline

Episiotomy was long promoted as a means of preserving the integrity of the perineal musculature and of avoiding damage to the anal sphincter, and it has been practiced routinely by some.27 Strong evidence now indicates that routine episiotomy (midline or mediolateral) is unhelpful and should be abandoned.25,27-29

Observational evidence overwhelmingly shows that midline episiotomy is strongly associated with obstetric anal sphincter injury.19,22,23,30,31 One of the few RCTs comparing midline with mediolateral episiotomy, although flawed in its design, noted that a clinical third-degree laceration occurred as an extension of episiotomy in 11.6% of midline incisions compared with just 2% of mediolateral cuts.32

Another RCT, designed to examine routine versus restrictive episiotomy, noted that all but 1 (98%) of the 47 third- or fourth-degree lacerations in a group of 700 women followed midline episiotomy.29 A retrospective database analysis noted a 6-fold higher risk of third-degree perineal lacerations for women undergoing midline episiotomy compared with mediolateral incision.23 Elsewhere, midline episiotomy was associated with a 5-fold increase in symptoms of fecal incontinence at 3 months postpartum when compared with women with an intact perineum.24

Even when midline episiotomies do not extend into clinical third-degree lacerations, the incidence of resultant postpartum fecal incontinence triples when compared with spontaneous second-degree perineal lacerations.30 The authors postulate that a perineum cut by midline episiotomy allows for more direct contact to occur between the fetal hard parts and the anal sphincter complex during delivery, thereby increasing occult obstetric anal sphincter injury.

Observational data conflict as to whether mediolateral episiotomy contributes to, or protects against, obstetric anal sphincter injury—although the burden of evidence favors it as a risk factor that should be avoided when possible.16,23,33 An angle of mediolateral incision cut closer to 45 degrees from the midline has been associated with less obstetric anal sphincter injury than incisions cut at closer angles to the midline.34

Repairing sphincter injury

Detecting injury in labor

With any severe perineal laceration, closely inspect the external and, if exposed, internal anal sphincter and perform a rectal exam, particularly for women with numerous risk factors (although no good evidence supports the role of the rectal exam in diagnosing obstetric anal sphincter injury). Colorectal surgeons have advocated the use of a muscle stimulator to assist in identifying the ends of the external sphincter, but this has not become common practice.35

Immediate vs delayed repair

It is standard practice to repair a damaged anal sphincter immediately or soon after delivery. However, given that a repair should be well done, and since a short delay does not appear to adversely affect healing, be prepared to wait for assistance for up to 24 hours rather than risk a suboptimal repair.36

Better training is needed

Even among trained obstetricians and obgyn residents, 64% have reported no training or unsatisfactory training in management of obstetric anal sphincter injury; 94% of physicians felt inadequately prepared at the time of their first independent repair of the anal sphincter.37,38 To improve your repair skills in a workshop setting, consult the following sources—www.aafp.org/also.xml in the US, or www.perineum.net in UK.

Analgesia and setting

Adequate analgesia is an essential element in a good repair. Complete relaxation of the anesthetized anal sphincter complex facilitates bringing torn ends of the sphincter together without tension.39 Though theoretically this can be attained with local anesthetic infiltration, RCOG recommends that regional or general anesthesia be considered to provide complete analgesia.37 It is further recommended that repair of the anal sphincter occur in an operating room, given the degree of contamination present in the labor room after delivery and the devastating effects of an infected repair (SOR: C).40

Repair technique

There are 2 commonly used methods of external anal sphincter repair: one, the traditionally taught end-to-end approximation of the cut ends, and the other, overlapping the cut ends of the external sphincter and suturing through the overlapped portions (FIGURE 2).36 Though an RCT from 2000 noted no significant difference in outcomes between these methods,41 other authors have suggested that an overlapping technique is preferred, and it remains the method most often used by colorectal surgeons in elective, secondary anal sphincter repairs.36,39,42

A Cochrane review of which technique is better has been registered in the Clinical Trials Database. General agreement is that closure using interrupted sutures of a monofilament material, such as 2-0 polydioxanone sulfate (PDS), is the preferred closure method for the external sphincter (SOR: C).36,40 It is recommended that a damaged internal sphincter be repaired with a running continuous suture of a material such as 2-0 polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) (SOR: C).36

FIGURE 2

2 methods of anal sphincter repair

Two commonly used methods of external anal sphincter repair are end-to-end approximate of the cut ends (top), and overlapping the cut ends and suturing through the overlapped portions (bottom). (Adapted from Leeman et al, Am Fam Physician 2003.33) ILLUSTRATION BY RICH LaROCCO

Immediate post-repair management

Use a stool softener

It had long been thought that constipation following obstetric anal sphincter injury allowed the sphincter to heal more effectively. However, new evidence from RCTs shows that using a laxative instead of a constipating regimen is more helpful in the immediate postpartum phase.43 Toward this end, use a stool softener, such as lactulose, for 3 to 10 days postpartum for women with obstetric anal sphincter injury.40

Should you prescribe an antibiotic?

Given the devastating effects of post-repair infection, most authorities consider it prudent to prescribe a course of broad-spectrum antibiotics, possibly including metronidazole (SOR: C)37,40 A Cochrane review is registered to further examine this issue. A separate Cochrane review of the use of antibiotics for instrument vaginal delivery concluded that quality data were insufficient to make any recommendations.44

Refer for physical therapy

Some authorities consider an early referral to physical therapy for pelvic floor exercises helpful in the immediate post-partum for all patients with obstetric anal sphincter injury (SOR: C).45

Long-term management

Ask patients about incontinence

Given that some women are too embarrassed to seek assistance, ask those with obstetric anal sphincter injury specific questions about any symptoms of anal incontinence at a follow-up visit, such as the 6-week postpartum visit (SOR: C).37,40 In some practices, all women who have sustained a third- or fourth-degree laceration are routinely scheduled for a 3-month follow-up visit to a dedicated clinic, irrespective of symptoms. Given the prevalence of occult obstetric anal sphincter injury for primigravid women, you may find it best to survey all women postnatally concerning any changes in anal continence. TABLE 3 demonstrates a validated, modified patient survey of anal incontinence.37,40 A score of 6 is often used as a cutoff.

TABLE 3

Fecal Continence Scoring scale

| SYMPTOM |

| 1. Passage of any flatus when socially undesirable |

| 2. Any incontinence of liquid stool |

| 3. Any need to wear a pad because of anal symptoms |

| 4. Any incontinence of solid stool |

| 5. Any fecal urgency (inability to defer defecation for more than 5 minutes) |

| SCALE |

| 0 Never |

| 1 Rarely (<1/month) |

| 2 Sometimes (1/week–1/month |

| 3 Usually (1/day–1/week) |

| 4 Always (>1/day) |

| A score of 0 implies complete continence and a score of 20 complete incontinence. |

| A score of 6 has been suggested as a cut-off to determine need for evaluation. |

| Source: Mahony et al, 2001;43 modified from Jorge and Wexner, 1993.44 |

When additional evaluation is needed

Patients who have symptoms of altered continence at 3 months (or who score above 6 on the Wexner scale) should be seen at a dedicated gynecologic or colorectal surgery clinic,46 where they can receive a more detailed clinical evaluation and undergo anal manometry (during resting and forced squeezing) or endoanal ultrasonography. Some patients respond well to physical therapy, though a few patients ultimately require reconstructive colorectal surgery and temporary colostomy.

Management in a subsequent pregnancy

Women who have had an obstetric anal sphincter injury are at increased risk for repeat injury in a future pregnancy.48 At some units, all such women are routinely offered a prenatal visit at the end of the second trimester to review their symptoms and to evaluate the anal sphincter with manometry or ultrasound. A large prospective study, however, found that recurrence of obstetric anal sphincter injury could not be predicted and that 95% of women with prior injury did not sustain further overt sphincter damage during a subsequent vaginal delivery.49

However, for some women, a repeat anal sphincter laceration could prove devastating. For these women—eg, those with previous severe symptoms that required secondary surgical repair—initiate an in-depth discussion concerning the risks and benefits of elective cesarean delivery versus vaginal delivery.37,40

Historically, fecal incontinence was defined as “the involuntary or inappropriate passage of feces.”10 However, a preferred definition now refers instead to anal incontinence, which is “any involuntary loss of feces or flatus, or urge incontinence, that is adversely affecting a woman’s quality of life.”40 This definition includes urgency of defecation and incontinence of flatus, both of which are much more common symptoms than fecal incontinence.50

Data are lacking on the community prevalence of incontinence, although it is known that women of age 45 experience 8 times the incidence of incontinence as men of the same age and that it increases in prevalence with age.10 A Canadian survey of almost 1000 women at 3 months postpartum revealed that 3.1% admitted to incontinence of feces while 25% admitted to involuntary escape of flatus. The subgroup of women who suffered clinical anal sphincter injury (that is, third- or fourth-degree lacerations) had considerably increased rates of incontinence of feces (7.8%) and of flatus (48%).24 It has been reported that approximately half of women who sustained anal sphincter tears in labor complained of anal, urinary, or perineal symptoms at a mean follow-up of 2.6 years after the injury.51 Most studies agree that many women are embarrassed about symptoms of anal incontinence and are reluctant to self-report them.50

CORRESPONDENCE

David Power, MD, MPH, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Minnesota, Mayo Mail Code 381, 516 Delaware St SE, Minneapolis, MN 55455. E-mail: [email protected]

- Avoiding obstetrical injury to the anal sphincter is the single biggest factor in preventing anal incontinence among women (A). Any form of instrument delivery has consistently been noted to increase the risk of obstetric anal sphincter injury and altered fecal continence by between 2- and 7-fold (A).

- Routine episiotomy is not recommended (A). Episiotomy use should be restricted to situations where it directly facilitates an urgent delivery (A). A mediolateral incision, instead of a midline, should be considered for persons at otherwise high risk of obstetric anal sphincter injury (A).

- The internal anal sphincter needs to be separately repaired if torn (A).

- Women with injuries to the internal anal sphincter or rectal mucosa have a worse prognosis for future continence problems (A). All women, particularly those with risk factors for injury, should be surveyed for symptoms of anal incontinence at postpartum follow-up (C).

Do you routinely check with new first-time mothers at a postpartum visit about changes in anal continence? They are at particular risk for obstetric anal sphincter injury and could be too embarrassed to raise the issue.

Sphincter injury following labor is the most common cause of anal incontinence (including flatus) in women, which can severely diminish quality of life and lead to considerable personal and financial costs.1 Endoanal ultrasound can detect these injuries, even in the absence of clinically obvious damage to the anal sphincter (occult obstetric anal sphincter injury).2

In this article, we review measures to reduce the occurrence of obstetric anal sphincter injury, proper primary repair when it does occur, and appropriate long-term follow-up. Women with known obstetric anal sphincter injury must also be counseled about the risk of further damage during a future vaginal delivery.

Injury more common than symptoms would suggest

The conventional definitions of the 4 grades of perineal laceration in the US have been supplemented by more recent modifications included in a recent British Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) guideline (TABLE 1).3 The definition of third-degree laceration now reflects the various degrees of anal sphincter injury that may occur: partial (3a), full-thickness (3b), external anal sphincter injury, with or without injury to the internal anal sphincter (3c).

The incidence of clinical third- and fourth-degree lacerations varies widely; it is reported at between 0.5% and 3.0% in Europe and between 5.85% and 8.9% in the US.2,4-6 A landmark British paper from 1993 revealed that though only 3% had a clinical third- or fourth-degree perineal laceration, 35% of primiparous women (none of whom had any defect before delivery) had ultrasound evidence of varying degrees of anal sphincter defect at 6 weeks postpartum that persisted at 6 months.2 However, only about a third of these women had symptoms of bowel disturbance during the time of study.

These findings are supported by a meta-analysis in which 70% of women with a documented obstetric anal sphincter injury were asymptomatic.7 This meta-analysis concluded that clinical or occult obstetric anal sphincter injury occurs in 27% of primigravid women, and in 8.5% of multiparous women.

The long-term significance of occult obstetric anal sphincter injury and any relationship with geriatric fecal incontinence is unknown, although 71% of a sample of women with late-onset fecal incontinence were found to have ultrasound evidence of an anal sphincter defect thought to have occurred at a previous vaginal delivery.8 A recent English study9 reveals that when women were carefully re-examined after delivery by a skilled obstetrician looking specifically at the anal sphincter, the prevalence of clinically diagnosed third-degree lacerations rose sharply from the 11% initially diagnosed by the delivering physician or midwife to 24.5%. A subsequent endoanal ultrasound detected only an additional 1.2% (3 injuries, 2 of which were in the internal anal sphincter and therefore clinically undetectable). This strongly suggests that the vast majority of obstetric anal sphincter injuries can be detected clinically by a careful exam and that, when this is done, true occult injuries will be a rare finding.

TABLE 1

Classification of perineal injury9

| INJURY | DEFINITION |

|---|---|

| First degree | Injury confined to vaginal mucosa |

| Second degree | Injury of vaginal mucosa and perineal muscles, but not the anal sphincter |

| Third degree | Injury to the perineum involving the anal sphincter complex (external and internal) |

| 3a | <50% of external sphincter thickness is torn |

| 3b | >50% of external sphincter thickness is torn |

| 3c | Internal sphincter is torn |

| Fourth degree | Injury to external and internal sphincter and rectal mucosa/anal epithelium |

Mechanisms of injury

Maintenance of fecal continence involves the coordinated action of several anatomical and physiological elements (FIGURE 1).10 An intact, innervated anal sphincter complex (both external and internal) is necessary. The sphincter complex can be damaged during childbirth in 3 ways.

Direct mechanical injury. Direct external or internal anal sphincter muscle disruption can occur, as with a clinically obvious third- or fourth-degree perineal laceration or an occult injury subsequently noted on ultrasound.

Neurologic injury. Neuropathy of the pudendal nerve may result from forceps delivery or persistent nerve compression from the fetal head.14 Traction neuropathy may also occur with fetal macrosomia and with prolonged pushing during Stage 2 in successive pregnancies, or with prolonged stretching of the nerve due to persistent poor postpartum pelvic floor tone. Injured nerves often undergo demyelination but usually recover with time.

Combined mechanical and neurologic trauma. Isolated neurologic injury, as described above, is believed to be rare. Neuropathy more commonly accompanies mechanical damage.15

Who is at risk?

Several risk factors are unavoidable. One of these is primiparity, a consistently reported independent variable also associated with other risk factors for obstetric anal sphincter injury, such as instrument delivery (TABLE 2).

TABLE 2

Major risk factors for obstetric anal sphincter injury

| RISK FACTOR | ODDS RATIO |

|---|---|

| Nulliparity (primigravidity) | 3–4 |

| Inherent predisposition: | |

| Short perineal body | 8 |

| Instrumental delivery, overall | 3 |

| Forceps-assisted delivery | 3–7 |

| Vacuum-assisted delivery | 3 |

| Forceps vs vacuum | 2.88* |

| Forceps with midline episiotomy | 25 |

| Prolonged second stage of labor (>1 hour) | 1.5–4 |

| Epidural analgesia | 1.5–3 |

| Intrapartum infant factors: | |

| Birthweight over 4 kg | 2 |

| Persistent occipitoposterior position | 2–3 |

| Episiotomy, mediolateral | 1.4 |

| Episiotomy, midline | 3–5 |

| Previous anal sphincter tear | 4 |

| All variables are statistically significant at P<.05. | |

| *Relative risk of altered fecal symptoms based on RCT findings, vacuum vs forceps.17 Data from randomized controlled trials are lacking for most labor variables. Due to differing methods of analysis (univariate vs regression) and outcome measures, risk ratios reported in the literature vary considerably. This table presents the approximate odds ratios for risk factors that have been reported most consistently from 1 prospective cohort study,16 1 randomized controlled trial,14 and, otherwise higher-quality retrospective analyses.18-23 | |

Preventing obstetric anal sphincter injury

Sphincter injury can occur even when obstetrical management is optimal. Although evidence from RCT data is often lacking, sufficient observational and retrospective data support the following recommendations to reduce the likelihood of injury.

Choose vacuum delivery before forceps

Any form of instrument delivery increases the risk of obstetric anal sphincter injury and altered fecal continence by between 2- and 7-fold.2,16,24 An RCT found clinical third-degree tears in 16% of women with forceps-assisted deliveries, compared with 7% of vacuum-assisted deliveries; the authors concluded that, when circumstances allow, vacuum delivery should be attempted first (acknowledging however that 23% of vacuum deliveries failed and proceeded to a forceps extraction, a sequence associated with increased injury).17 A meta-analysis confirmed that vacuum extraction is preferred when instrumental delivery is necessary (SOR: A).25

When midline episiotomy was performed during instrument delivery, the risk of obstetric anal sphincter injury approximately doubled again, such that, in one study, forceps delivery with episiotomy caused a 25-fold increase in obstetric anal sphincter injury.24

Any steps that may safely reduce the need for instrument delivery should be supported. Toward this end, the Canadian Clinical Practices Obstetrics committee has recommended evidence-based labor interventions such as one-to-one support in labor, the increased use of a partogram in labor and appropriate oxytocin use, all in an effort to reduce needs for operative interventions.26

If episiotomy necessary, mediolateral less risky than midline

Episiotomy was long promoted as a means of preserving the integrity of the perineal musculature and of avoiding damage to the anal sphincter, and it has been practiced routinely by some.27 Strong evidence now indicates that routine episiotomy (midline or mediolateral) is unhelpful and should be abandoned.25,27-29

Observational evidence overwhelmingly shows that midline episiotomy is strongly associated with obstetric anal sphincter injury.19,22,23,30,31 One of the few RCTs comparing midline with mediolateral episiotomy, although flawed in its design, noted that a clinical third-degree laceration occurred as an extension of episiotomy in 11.6% of midline incisions compared with just 2% of mediolateral cuts.32

Another RCT, designed to examine routine versus restrictive episiotomy, noted that all but 1 (98%) of the 47 third- or fourth-degree lacerations in a group of 700 women followed midline episiotomy.29 A retrospective database analysis noted a 6-fold higher risk of third-degree perineal lacerations for women undergoing midline episiotomy compared with mediolateral incision.23 Elsewhere, midline episiotomy was associated with a 5-fold increase in symptoms of fecal incontinence at 3 months postpartum when compared with women with an intact perineum.24

Even when midline episiotomies do not extend into clinical third-degree lacerations, the incidence of resultant postpartum fecal incontinence triples when compared with spontaneous second-degree perineal lacerations.30 The authors postulate that a perineum cut by midline episiotomy allows for more direct contact to occur between the fetal hard parts and the anal sphincter complex during delivery, thereby increasing occult obstetric anal sphincter injury.

Observational data conflict as to whether mediolateral episiotomy contributes to, or protects against, obstetric anal sphincter injury—although the burden of evidence favors it as a risk factor that should be avoided when possible.16,23,33 An angle of mediolateral incision cut closer to 45 degrees from the midline has been associated with less obstetric anal sphincter injury than incisions cut at closer angles to the midline.34

Repairing sphincter injury

Detecting injury in labor

With any severe perineal laceration, closely inspect the external and, if exposed, internal anal sphincter and perform a rectal exam, particularly for women with numerous risk factors (although no good evidence supports the role of the rectal exam in diagnosing obstetric anal sphincter injury). Colorectal surgeons have advocated the use of a muscle stimulator to assist in identifying the ends of the external sphincter, but this has not become common practice.35

Immediate vs delayed repair

It is standard practice to repair a damaged anal sphincter immediately or soon after delivery. However, given that a repair should be well done, and since a short delay does not appear to adversely affect healing, be prepared to wait for assistance for up to 24 hours rather than risk a suboptimal repair.36

Better training is needed

Even among trained obstetricians and obgyn residents, 64% have reported no training or unsatisfactory training in management of obstetric anal sphincter injury; 94% of physicians felt inadequately prepared at the time of their first independent repair of the anal sphincter.37,38 To improve your repair skills in a workshop setting, consult the following sources—www.aafp.org/also.xml in the US, or www.perineum.net in UK.

Analgesia and setting

Adequate analgesia is an essential element in a good repair. Complete relaxation of the anesthetized anal sphincter complex facilitates bringing torn ends of the sphincter together without tension.39 Though theoretically this can be attained with local anesthetic infiltration, RCOG recommends that regional or general anesthesia be considered to provide complete analgesia.37 It is further recommended that repair of the anal sphincter occur in an operating room, given the degree of contamination present in the labor room after delivery and the devastating effects of an infected repair (SOR: C).40

Repair technique

There are 2 commonly used methods of external anal sphincter repair: one, the traditionally taught end-to-end approximation of the cut ends, and the other, overlapping the cut ends of the external sphincter and suturing through the overlapped portions (FIGURE 2).36 Though an RCT from 2000 noted no significant difference in outcomes between these methods,41 other authors have suggested that an overlapping technique is preferred, and it remains the method most often used by colorectal surgeons in elective, secondary anal sphincter repairs.36,39,42

A Cochrane review of which technique is better has been registered in the Clinical Trials Database. General agreement is that closure using interrupted sutures of a monofilament material, such as 2-0 polydioxanone sulfate (PDS), is the preferred closure method for the external sphincter (SOR: C).36,40 It is recommended that a damaged internal sphincter be repaired with a running continuous suture of a material such as 2-0 polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) (SOR: C).36

FIGURE 2

2 methods of anal sphincter repair

Two commonly used methods of external anal sphincter repair are end-to-end approximate of the cut ends (top), and overlapping the cut ends and suturing through the overlapped portions (bottom). (Adapted from Leeman et al, Am Fam Physician 2003.33) ILLUSTRATION BY RICH LaROCCO

Immediate post-repair management

Use a stool softener

It had long been thought that constipation following obstetric anal sphincter injury allowed the sphincter to heal more effectively. However, new evidence from RCTs shows that using a laxative instead of a constipating regimen is more helpful in the immediate postpartum phase.43 Toward this end, use a stool softener, such as lactulose, for 3 to 10 days postpartum for women with obstetric anal sphincter injury.40

Should you prescribe an antibiotic?

Given the devastating effects of post-repair infection, most authorities consider it prudent to prescribe a course of broad-spectrum antibiotics, possibly including metronidazole (SOR: C)37,40 A Cochrane review is registered to further examine this issue. A separate Cochrane review of the use of antibiotics for instrument vaginal delivery concluded that quality data were insufficient to make any recommendations.44

Refer for physical therapy

Some authorities consider an early referral to physical therapy for pelvic floor exercises helpful in the immediate post-partum for all patients with obstetric anal sphincter injury (SOR: C).45

Long-term management

Ask patients about incontinence

Given that some women are too embarrassed to seek assistance, ask those with obstetric anal sphincter injury specific questions about any symptoms of anal incontinence at a follow-up visit, such as the 6-week postpartum visit (SOR: C).37,40 In some practices, all women who have sustained a third- or fourth-degree laceration are routinely scheduled for a 3-month follow-up visit to a dedicated clinic, irrespective of symptoms. Given the prevalence of occult obstetric anal sphincter injury for primigravid women, you may find it best to survey all women postnatally concerning any changes in anal continence. TABLE 3 demonstrates a validated, modified patient survey of anal incontinence.37,40 A score of 6 is often used as a cutoff.

TABLE 3

Fecal Continence Scoring scale

| SYMPTOM |

| 1. Passage of any flatus when socially undesirable |

| 2. Any incontinence of liquid stool |

| 3. Any need to wear a pad because of anal symptoms |

| 4. Any incontinence of solid stool |

| 5. Any fecal urgency (inability to defer defecation for more than 5 minutes) |

| SCALE |

| 0 Never |

| 1 Rarely (<1/month) |

| 2 Sometimes (1/week–1/month |

| 3 Usually (1/day–1/week) |

| 4 Always (>1/day) |

| A score of 0 implies complete continence and a score of 20 complete incontinence. |

| A score of 6 has been suggested as a cut-off to determine need for evaluation. |

| Source: Mahony et al, 2001;43 modified from Jorge and Wexner, 1993.44 |

When additional evaluation is needed

Patients who have symptoms of altered continence at 3 months (or who score above 6 on the Wexner scale) should be seen at a dedicated gynecologic or colorectal surgery clinic,46 where they can receive a more detailed clinical evaluation and undergo anal manometry (during resting and forced squeezing) or endoanal ultrasonography. Some patients respond well to physical therapy, though a few patients ultimately require reconstructive colorectal surgery and temporary colostomy.

Management in a subsequent pregnancy

Women who have had an obstetric anal sphincter injury are at increased risk for repeat injury in a future pregnancy.48 At some units, all such women are routinely offered a prenatal visit at the end of the second trimester to review their symptoms and to evaluate the anal sphincter with manometry or ultrasound. A large prospective study, however, found that recurrence of obstetric anal sphincter injury could not be predicted and that 95% of women with prior injury did not sustain further overt sphincter damage during a subsequent vaginal delivery.49

However, for some women, a repeat anal sphincter laceration could prove devastating. For these women—eg, those with previous severe symptoms that required secondary surgical repair—initiate an in-depth discussion concerning the risks and benefits of elective cesarean delivery versus vaginal delivery.37,40

Historically, fecal incontinence was defined as “the involuntary or inappropriate passage of feces.”10 However, a preferred definition now refers instead to anal incontinence, which is “any involuntary loss of feces or flatus, or urge incontinence, that is adversely affecting a woman’s quality of life.”40 This definition includes urgency of defecation and incontinence of flatus, both of which are much more common symptoms than fecal incontinence.50

Data are lacking on the community prevalence of incontinence, although it is known that women of age 45 experience 8 times the incidence of incontinence as men of the same age and that it increases in prevalence with age.10 A Canadian survey of almost 1000 women at 3 months postpartum revealed that 3.1% admitted to incontinence of feces while 25% admitted to involuntary escape of flatus. The subgroup of women who suffered clinical anal sphincter injury (that is, third- or fourth-degree lacerations) had considerably increased rates of incontinence of feces (7.8%) and of flatus (48%).24 It has been reported that approximately half of women who sustained anal sphincter tears in labor complained of anal, urinary, or perineal symptoms at a mean follow-up of 2.6 years after the injury.51 Most studies agree that many women are embarrassed about symptoms of anal incontinence and are reluctant to self-report them.50

CORRESPONDENCE

David Power, MD, MPH, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Minnesota, Mayo Mail Code 381, 516 Delaware St SE, Minneapolis, MN 55455. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Mellgren A, Jensen LL, Zetterstrom JP, Wong WD, Hofmeister JH, Lowry AC. Long-term cost of fecal incontinence secondary to obstetric injuries. Dis Colon Rectum 1999;42:857-865.

2. Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN, Thomas JM, Bartram CI. Anal-sphincter disruption during vaginal delivery. N Engl J Med 1993;329:1905-1911.

3. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Methods and Materials used in Perineal Repair. Guideline No. 23. London: RCOG Press; 2004.

4. Fitzpatrick M, Behan M, O’Connell PR, O’Herlihy C. A randomized clinical trial comparing primary overlap with approximation repair of third-degree obstetric tears. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000;183:1220-1224.

5. Simhan HN, Krohn MA, Heine RP. Obstetric rectal injury: risk factors and the role of physician experience. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2004;16:271-274.

6. Handa VL, Danielsen BH, Gilbert WM. Obstetric anal sphincter lacerations. Obstet Gynecol 2001;98:225-230.

7. Oberwalder M, Connor J, Wexner SD. Meta-analysis to determine the incidence of obstetric anal sphincter damage. Br J Surg 2003;90:1333-1337.

8. Oberwalder M, Dinnewitzer A, Baig MK, et al. The association between late-onset fecal incontinence and obstetric anal sphincter defects. Arch Surg 2004;139:429-432.

9. Andrews V, Sultan AH, Thakar R, Jones PW. Occult anal sphincter injuries-myth or reality? BJOG 2006;113:195-200.

10. Sultan AH, Nugent K. Pathophysiology and nonsurgical treatment of anal incontinence. BJOG 2004;111 (Suppl 1):84-90.

11. Schafer A, Enck P, Furst G, et al. Anatomy of the anal sphincters. Dis Colon Rectum 1994;37:777-781.

12. Mahony R, Daly L, Behan M, Kirwan C, O’Herlihy C, O’Connell R. Internal Anal Sphincter injury predicts continence outcome following obstetric sphincter trauma. AJOG 2004;191:6s1-s89.

13. Bartram CL, Frudringer A. Handbook of Anal Endosonography. Petersfield, UK: Wrightson Biomedical Publishing; 1997.

14. Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN. Pudendal nerve damage during labor: prospective study before and after childbirth. BJOG 1994;101:22-28.

15. Snooks SJ, Henry MM, Swash M. Fecal incontinence due to external anal sphincter division in childbirth is associated with damage to the innervation of the pelvic floor musculature: a double pathology. BJOG 1985;92:824-828.

16. Donnelly V, Fynes M, Campbell D, Johnson H, O’Connell PR, O’Herlihy C. Obstetric events leading to anal sphincter damage. Obstet Gynecol 1998;92:955-961.

17. Fitzpatrick M, Behan M, O’Connell PR, O’Herlihy C. Randomized clinical trial to assess anal sphincter function following forceps or vacuum assisted vaginal delivery. BJOG 2003;110:424-429.

18. Deering SH, Carlson N, Stitely M, Allaire AD, Satin AJ. Perineal body length and lacerations at delivery. J Reproductive Medicine 2004;49:306-310.

19. Goldberg J, Hyslop T, Tolosa JE, Sultana C. Racial Differences in severe Perineal lacerations after vaginal delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;188:1063-1067.

20. Robinson JN, Norwitz ER, Cohen AP, McElrath TF, Lieberman ES. Epidural analgesia and third- or fourth-degree lacerations in nulliparas. Obstet Gynecol 1999;94:259-262.

21. Carroll TG, Engelken M, Mosier MC, Nazir N. Epidural analgesia and severe perineal laceration in a community-based obstetric practice. J Am Board Fam Prac 2003;16:1-6.

22. Riskin-Mashiah S, O’Brian Smith E, Wilkins IA. Risk factors for severe perineal tear: can we do better? Am J Perinatol 2002;19:225-234.

23. Bodner-Adler B, Bodner K, Kaider A, et al. Risk factors for third-degree perineal tears in vaginal deliveries with an analysis of episiotomy types. J Reprod Med 2001;46:752-756.

24. Eason E, Labrecque M, Marcoux S, Mondor M. Anal incontinence after childbirth. CMAJ 2002;166:326-330.

25. Eason E, Labrecque M, Wells G, Feldman P. Preventing perineal trauma during childbirth: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 2000;95:464-471.

26. Cargill YM, MacKinnon CJ, Arsensault MY, et al. Clinical Practice Obstetrics Committee. Guidelines for operative vaginal birth. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2004;26:747-761.

27. Carroli G, Belizan J. Episiotomy for vaginal birth. Cochrane Database System Rev 1999;(3):CD000081.-

28. Schlomer G, Gross M, Meyer G. Effectiveness of liberal vs. conservative episiotomy in vaginal delivery with reference to preventing urinary and fecal incontinence: a systematic review [in German]. Wien Med Wochenschr 2003;153:269-275.

29. Klein MC, Gauthier RJ, Jorgensen SH, et al. Does episiotomy prevent perineal trauma and pelvic floor relaxation? Online J Curr Clin Trials 1992;Doc No 10.

30. Signorello LB, Harlow BL, Chekos AK, Repke JT. Midline episiotomy and anal incontinence: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2000;320:86-90.

31. Shiono P, Klebanoff MA, Carey JC. Midline episiotomies: more harm than good? Obstet Gynecol 1990;75:765-770.

32. Coats PM, Chan KK, Wilkins M, Beard RJ. A comparison between midline and mediolateral episiotomies. BJOG 1980;87:408-412.

33. Poen AC, Felt-Bersma RJ, Dekker GA, Deville W, Cuesta MA, Meuwissen SG. Third degree obstetric perineal tears: risk factors and the preventive role of mediolateral episiotomy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1997;104:563-566.

34. Eogan M, O’Connell R, O’Herlihy C. Does the angle of episiotomy affect the incidence of anal sphincter injury? BJOG 2006;113:190-194.

35. Cook TA, Keane D, Mortensen NJ. Is there a role for the colorectal team in the management of acute severe third-degree vaginal tears? Colorectal Dis 1999;1:263-266.

36. Leeman L, Spearman M, Rogers R. Repair of obstetric perineal lacerations. Am Fam Physician 2003;68:1585-1590.

37. Fernando RJ, Sultan AH, Radley S, Jones PW, Johanson RB. Management of obstetric anal sphincter injury: a systematic review & national practice survey. BMC Health Serv Res 2002;2:9.-

38. Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN. Obstetric perineal trauma: an audit of training. J Obstet Gynaecol 1995;15:19-23.

39. Sultan AH, Monga AK, Kumar D, Stanton SL. Primary repair of obstetric anal sphincter rupture using the overlap technique. BJOG 1999;106:318-23.

40. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Management of third- and fourth-degree perineal tears following vaginal delivery. Guideline No. 29. London: RCOG Press; 2001.

41. Fitzpatrick M, Behan M, O’Connell PR, O’Herlihy C. A randomised clinical trial comparing primary overlap with approximation repair of third degree tears. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000;183:1220-1224.

42. Kairaluoma MV, Raivio P, Aarnio MT, Kellokumpo IH. Immediate repair of obstetric anal sphincter rupture: medium-term outcome of the overlap technique. Dis Colon Rectum 2004;47:1358-1363.

43. Mahony R, Behan M, O’Herlihy C, O’Connell PR. Randomized, clinical trial of bowel confinement vs. laxative use after primary repair of a third-degree obstetric anal sphincter tear. Dis Colon Rectum 2004;47:12-17.

44. Liabsuetrakul T, Choobun T, Peeyananjarassri K, Islam M. Antibiotic prophylaxis for operative vaginal delivery (Cochrane review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 2, 2004.

45. Fitzpatrick M, O’Herlihy C. Postpartum anal sphincter dysfunction. Current Obstet Gynaecol 1999;9:210-215.

46. Mahony R, O’Brien C, O’Herlihy C. Evaluation of obstetric anal sphincter injury. Reviews in Gynaecological Practice 2001;1:114-121.

47. Jorge M, Wexner S. Etiology and management of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 1993;36:77-97.

48. Fynes M, Donnelly V, Behan M, O’Connell PR, O’Herlihy C. Effect of second vaginal delivery on anorectal physiology and faecal continence: a prospective study. Lancet 1999;354:983-986.

49. Harkin R, Fitzpatrick M, O’Connell PR, O’Herlihy C. Anal sphincter disruption at vaginal deliver: is recurrence predictable? Eur J Obstet Gynaecol 2003;109:149-152.

50. Fitzpatrick M, O’Herlihy C. The effects of labour and delivery on the pelvic floor. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2001;15:63-79.

51. Wood J, Amos L, Rieger N. Third degree anal sphincter tears: risk factors and outcome. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 1998;38:414-417.

1. Mellgren A, Jensen LL, Zetterstrom JP, Wong WD, Hofmeister JH, Lowry AC. Long-term cost of fecal incontinence secondary to obstetric injuries. Dis Colon Rectum 1999;42:857-865.

2. Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN, Thomas JM, Bartram CI. Anal-sphincter disruption during vaginal delivery. N Engl J Med 1993;329:1905-1911.

3. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Methods and Materials used in Perineal Repair. Guideline No. 23. London: RCOG Press; 2004.

4. Fitzpatrick M, Behan M, O’Connell PR, O’Herlihy C. A randomized clinical trial comparing primary overlap with approximation repair of third-degree obstetric tears. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000;183:1220-1224.