User login

Meaningful Use – Stage 2 (Part 2 of 2)

In last month’s column, we began our discussion of Stage 2 of meaningful use. As a reminder, we noted that clinicians must meet or exceed the thresholds for the 17 core objectives and three of six menu objectives, as well as report on defined Clinical Quality Measures. We reviewed in detail the rationale for the program, as well as details of the core and menu measures.

For Stage 2 of meaningful use, the menu items and quality measures are aimed at enhancing actionable decision support to improve the quality of medical care and enable population management for patients who come into our office (and even for those who don’t). Stage 2 is also meant to facilitate physician-patient communication.

As a point of reminder and clarification, on August 29th the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services published a final rule allowing certain eligible providers the flexibility to continue using the Stage 1 criteria for the 2014 attestation year, even if they were due to start Stage 2. Unfortunately, this only applies to those who have been unable to obtain the 2014-certified software in time because of vendor delays. The reprieve does not extend to those who can’t meet Stage 2 due to measure difficulty or procrastination in purchasing software or adopting new work flow. As always, we recommend speaking with a meaningful use expert or consultant before attempting to take advantage of this flexibility. Either way, you’ll need to proceed with the 2014 Clinical Quality Measures, as these new definitions are now required by both the Stage 1 and Stage 2 goals. In this month’s EHR Report, we will highlight the most noteworthy 2014 Clinical Quality Measures.

Clinical Quality Measures are meant to measure and track the quality of health care services that are provided by the practitioner. Clinical Quality Measures are constructed to measure these aspects of care:

• Health outcomes

• Cinical processes

• Patient safety

• Efficient use of health care resources

• Care coordination

• Patient engagements

• Population and public health

• Adherence to clinical guidelines

Beginning in 2014, practitioners must select and report on 9 out of a list of 64 approved Clinical Quality Measures for the EHR Incentive Programs.

Clinical Quality Measures may be reported electronically through the EHR if this function is available through your EHR software. It can also be done through CMS’s Physician Quality Reporting System Portal. In order for a practice to report through the portal, the practice needs to sign up through CMS, which can be done through the CMS website. In addition, reporting can be done through a number of group reporting options if a practice is part of a large group of practices or an ACO, or via attestation as before. While the details go of how to report go beyond what we can cover in this column, your IT support person or consultant should be well acquainted with the process.

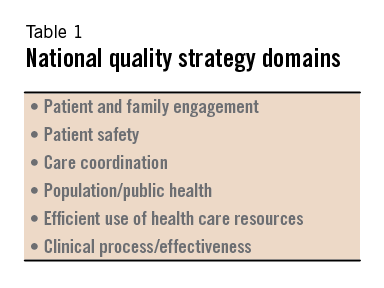

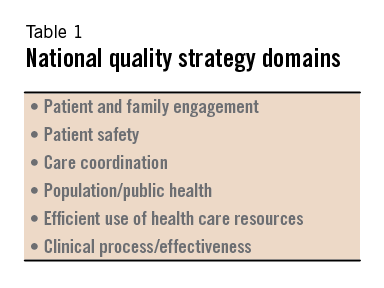

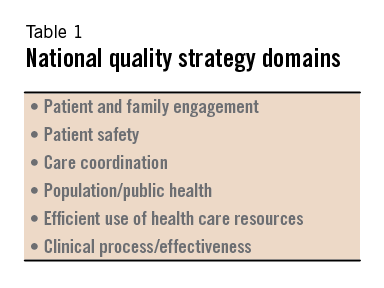

The Clinical Quality Measures are divided into six different domains of care, and providers must report on Clinical Quality Measures from at least three different domains (Table 1).

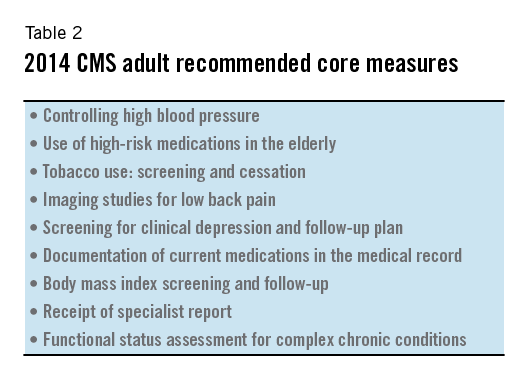

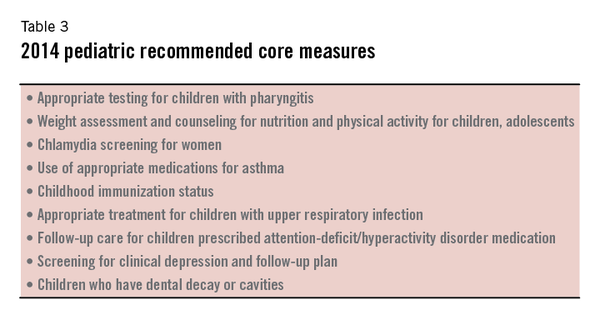

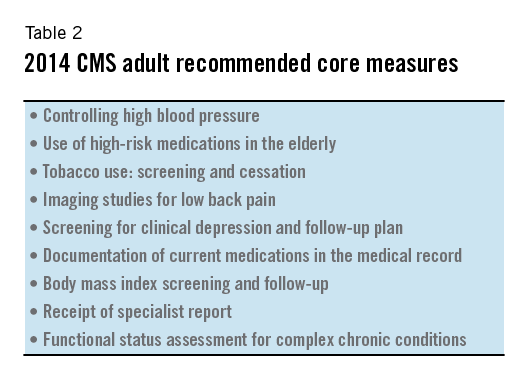

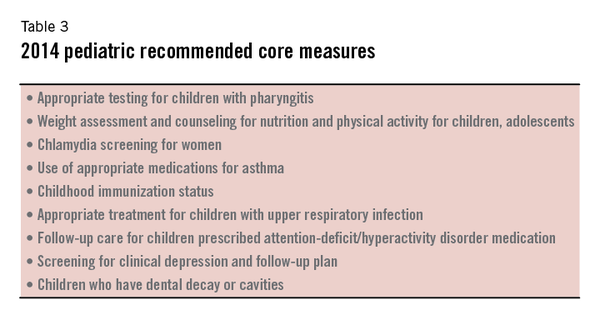

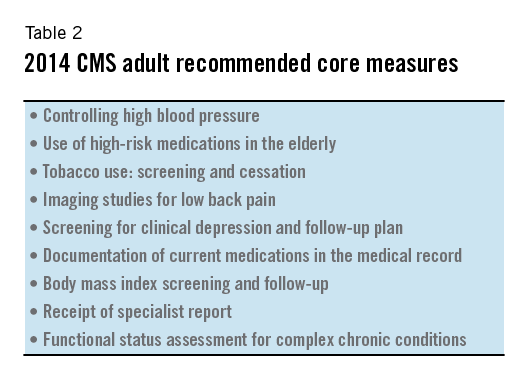

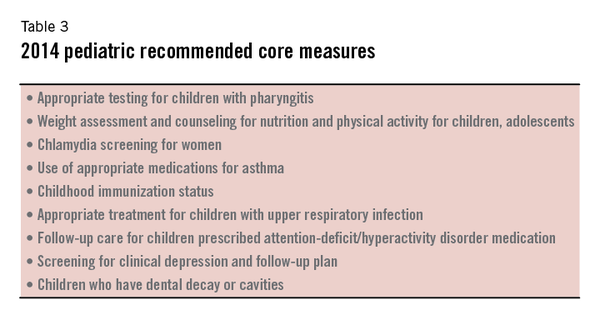

CMS encourages reporting on nine recommended core sets of Clinical Quality Measures, as long as those measures are relevant to a practitioner’s patient population. The recommended core measures focus on aspects of medical care that are felt to have the most significant effect on morbidity and mortality of Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries.

They also focus on aspects of medical care that are consistent with national public health priorities or that particularly increase healthcare costs. The nine measures recommended by CMS for adult and pediatric populations are listed in Tables 2 and 3.

Between Core Objectives, Menu Objectives, and CQMs, the requirements for Stage 2 meaningful use have gotten more complicated and perhaps more confusing to track and implement than before. We recommend that every practice has an identified individual who will become a resource to help others both understand and implement Stage 2 meaningful use. We anticipate a range of opinion about the challenges of Stage 2 and are interested in your thoughts. Please email us, and we will try to publish some of the comments in upcoming columns.

References:

1. An Introduction to EHR Incentive Programs 2014 Clincial Quality Measure (CQM) Electronic Reporting Guide for Eligible Professionals.

http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/Downloads/CQM2014_GuideEP.pdf.

2. Eligible Professionals Guide to Stage 2 of the EHR Incentive Programs http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/Downloads/Stage2_Guide_EPs_9_23_13.pdf.

3. For a comprehensive list of the CQMs, see the 2014 CQMs for eligible professionals PDF (available at http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/Downloads/EP_MeasuresTable_Posting_CQMs.pdf).

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

In last month’s column, we began our discussion of Stage 2 of meaningful use. As a reminder, we noted that clinicians must meet or exceed the thresholds for the 17 core objectives and three of six menu objectives, as well as report on defined Clinical Quality Measures. We reviewed in detail the rationale for the program, as well as details of the core and menu measures.

For Stage 2 of meaningful use, the menu items and quality measures are aimed at enhancing actionable decision support to improve the quality of medical care and enable population management for patients who come into our office (and even for those who don’t). Stage 2 is also meant to facilitate physician-patient communication.

As a point of reminder and clarification, on August 29th the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services published a final rule allowing certain eligible providers the flexibility to continue using the Stage 1 criteria for the 2014 attestation year, even if they were due to start Stage 2. Unfortunately, this only applies to those who have been unable to obtain the 2014-certified software in time because of vendor delays. The reprieve does not extend to those who can’t meet Stage 2 due to measure difficulty or procrastination in purchasing software or adopting new work flow. As always, we recommend speaking with a meaningful use expert or consultant before attempting to take advantage of this flexibility. Either way, you’ll need to proceed with the 2014 Clinical Quality Measures, as these new definitions are now required by both the Stage 1 and Stage 2 goals. In this month’s EHR Report, we will highlight the most noteworthy 2014 Clinical Quality Measures.

Clinical Quality Measures are meant to measure and track the quality of health care services that are provided by the practitioner. Clinical Quality Measures are constructed to measure these aspects of care:

• Health outcomes

• Cinical processes

• Patient safety

• Efficient use of health care resources

• Care coordination

• Patient engagements

• Population and public health

• Adherence to clinical guidelines

Beginning in 2014, practitioners must select and report on 9 out of a list of 64 approved Clinical Quality Measures for the EHR Incentive Programs.

Clinical Quality Measures may be reported electronically through the EHR if this function is available through your EHR software. It can also be done through CMS’s Physician Quality Reporting System Portal. In order for a practice to report through the portal, the practice needs to sign up through CMS, which can be done through the CMS website. In addition, reporting can be done through a number of group reporting options if a practice is part of a large group of practices or an ACO, or via attestation as before. While the details go of how to report go beyond what we can cover in this column, your IT support person or consultant should be well acquainted with the process.

The Clinical Quality Measures are divided into six different domains of care, and providers must report on Clinical Quality Measures from at least three different domains (Table 1).

CMS encourages reporting on nine recommended core sets of Clinical Quality Measures, as long as those measures are relevant to a practitioner’s patient population. The recommended core measures focus on aspects of medical care that are felt to have the most significant effect on morbidity and mortality of Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries.

They also focus on aspects of medical care that are consistent with national public health priorities or that particularly increase healthcare costs. The nine measures recommended by CMS for adult and pediatric populations are listed in Tables 2 and 3.

Between Core Objectives, Menu Objectives, and CQMs, the requirements for Stage 2 meaningful use have gotten more complicated and perhaps more confusing to track and implement than before. We recommend that every practice has an identified individual who will become a resource to help others both understand and implement Stage 2 meaningful use. We anticipate a range of opinion about the challenges of Stage 2 and are interested in your thoughts. Please email us, and we will try to publish some of the comments in upcoming columns.

References:

1. An Introduction to EHR Incentive Programs 2014 Clincial Quality Measure (CQM) Electronic Reporting Guide for Eligible Professionals.

http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/Downloads/CQM2014_GuideEP.pdf.

2. Eligible Professionals Guide to Stage 2 of the EHR Incentive Programs http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/Downloads/Stage2_Guide_EPs_9_23_13.pdf.

3. For a comprehensive list of the CQMs, see the 2014 CQMs for eligible professionals PDF (available at http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/Downloads/EP_MeasuresTable_Posting_CQMs.pdf).

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

In last month’s column, we began our discussion of Stage 2 of meaningful use. As a reminder, we noted that clinicians must meet or exceed the thresholds for the 17 core objectives and three of six menu objectives, as well as report on defined Clinical Quality Measures. We reviewed in detail the rationale for the program, as well as details of the core and menu measures.

For Stage 2 of meaningful use, the menu items and quality measures are aimed at enhancing actionable decision support to improve the quality of medical care and enable population management for patients who come into our office (and even for those who don’t). Stage 2 is also meant to facilitate physician-patient communication.

As a point of reminder and clarification, on August 29th the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services published a final rule allowing certain eligible providers the flexibility to continue using the Stage 1 criteria for the 2014 attestation year, even if they were due to start Stage 2. Unfortunately, this only applies to those who have been unable to obtain the 2014-certified software in time because of vendor delays. The reprieve does not extend to those who can’t meet Stage 2 due to measure difficulty or procrastination in purchasing software or adopting new work flow. As always, we recommend speaking with a meaningful use expert or consultant before attempting to take advantage of this flexibility. Either way, you’ll need to proceed with the 2014 Clinical Quality Measures, as these new definitions are now required by both the Stage 1 and Stage 2 goals. In this month’s EHR Report, we will highlight the most noteworthy 2014 Clinical Quality Measures.

Clinical Quality Measures are meant to measure and track the quality of health care services that are provided by the practitioner. Clinical Quality Measures are constructed to measure these aspects of care:

• Health outcomes

• Cinical processes

• Patient safety

• Efficient use of health care resources

• Care coordination

• Patient engagements

• Population and public health

• Adherence to clinical guidelines

Beginning in 2014, practitioners must select and report on 9 out of a list of 64 approved Clinical Quality Measures for the EHR Incentive Programs.

Clinical Quality Measures may be reported electronically through the EHR if this function is available through your EHR software. It can also be done through CMS’s Physician Quality Reporting System Portal. In order for a practice to report through the portal, the practice needs to sign up through CMS, which can be done through the CMS website. In addition, reporting can be done through a number of group reporting options if a practice is part of a large group of practices or an ACO, or via attestation as before. While the details go of how to report go beyond what we can cover in this column, your IT support person or consultant should be well acquainted with the process.

The Clinical Quality Measures are divided into six different domains of care, and providers must report on Clinical Quality Measures from at least three different domains (Table 1).

CMS encourages reporting on nine recommended core sets of Clinical Quality Measures, as long as those measures are relevant to a practitioner’s patient population. The recommended core measures focus on aspects of medical care that are felt to have the most significant effect on morbidity and mortality of Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries.

They also focus on aspects of medical care that are consistent with national public health priorities or that particularly increase healthcare costs. The nine measures recommended by CMS for adult and pediatric populations are listed in Tables 2 and 3.

Between Core Objectives, Menu Objectives, and CQMs, the requirements for Stage 2 meaningful use have gotten more complicated and perhaps more confusing to track and implement than before. We recommend that every practice has an identified individual who will become a resource to help others both understand and implement Stage 2 meaningful use. We anticipate a range of opinion about the challenges of Stage 2 and are interested in your thoughts. Please email us, and we will try to publish some of the comments in upcoming columns.

References:

1. An Introduction to EHR Incentive Programs 2014 Clincial Quality Measure (CQM) Electronic Reporting Guide for Eligible Professionals.

http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/Downloads/CQM2014_GuideEP.pdf.

2. Eligible Professionals Guide to Stage 2 of the EHR Incentive Programs http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/Downloads/Stage2_Guide_EPs_9_23_13.pdf.

3. For a comprehensive list of the CQMs, see the 2014 CQMs for eligible professionals PDF (available at http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/Downloads/EP_MeasuresTable_Posting_CQMs.pdf).

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

Commentary: EHRs Failing on Usability

Despite the federal government’s pledges of financial incentives and eventual penalties, adoption rates of electronic health record (EHR) systems remain stubbornly low. When a product or service is still underutilized, even after being subsidized by public funds, we have to ask ourselves why.

Many vendors advise physicians that extensive training is needed to learn how to document a note using their system and that they should be prepared to reduce their patient volume throughout the EHR adoption period. This lost patient volume is the direct result of data collection gone awry.

The concept of “usability” is defined as the ease with which people can use a particular product to accomplish defined goals. The lack of usability has been a major cause of dissatisfaction with EHR systems. It has been estimated that one in every three EHR adoptions fail, with poor usability likely a major contributing factor.

Unfortunately, the true experience of an EHR’s usability only occurs well after an EHR contract is signed, training has completed, and the light patient load has ended. That is when the seriousness of poor EHR usability becomes apparent.

To compensate, many physicians end up using templates, macros, and preset lists. This may help alleviate the slowdown caused by an EHR’s poor design, and the resulting patient notes may be full of data, but they often lack any real substance. The real story in each patient encounter is frequently lost. This is a common complaint reported by physicians attempting to use notes generated by an EHR.

To add insult to injury, there is an ever-growing list of horror stories reported by physicians who have given up on their EHRs. Unfortunately, many EHR vendors do not allow dissatisfied users out of their long-term contracts. Or if a vendor does allow a physician out of the contract at a reduced cost, there are often stipulations. One of the physicians we interviewed for this article said that he was negotiating an early termination of his contract, but to do so he had to sign a nondisclosure statement saying he would never comment on his poor experience with that EHR.

So how can a physician avoid ending up with an EHR that may be unusable? It is essential to review the experience of those who have already purchased an EHR. The American Academy of Family Physicians’ Center for Health IT provides a Web site through which members can rate their own EHR based on a five-point scale measuring quality, price, support, ease of use, and impact on productivity. Sorting the available list of 93 EHR systems by rating provides a clear look at overall user satisfaction (www.centerforhit.org).

User satisfaction studies are another indispensable resource. An October 2009 survey of over 3,700 EHR users published by Medscape.com found that over 30% of respondents would not recommend their EHR (http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/709856).

Similarly, “The 2009 EHR User Satisfaction Survey,” published in the November/December 2009 issue of Family Practice Management, provides a troubling look at how physicians rate many of the best known EHRs. This survey’s final question asked 2,012 family physicians if they agreed or disagreed with the following statement, “I am highly satisfied with this EHR system.” Astoundingly, nearly 50% of all respondents said that they would not agree.

With the current rate of physician dissatisfaction, EHR adoption rates will likely remain low despite the government incentives. Perhaps most ironic is that federal financial incentives to adopt EHR systems may contribute to delays in improvements in EHR usability. Rather than allowing competition to reward vendors who produce better software at lower prices, the stimulus money encourages physicians to purchase mediocre software at inflated prices.

As physicians recognize the perils of signing EHR contracts before they truly know if an EHR is usable, they will begin to demand usable, intuitive EHRs. Increasingly, physicians will come to appreciate how financial incentives and initial system costs are dwarfed by the potential reduction in productivity and revenue when a system proves difficult to use. As they gain more exposure to the EHR market, physicians will start to ask the important questions and demand answers about the critical issue of usability, which ultimately makes or breaks their EHR experience.

This column, “EHR Report,” regularly appears in Family Practice News, an Elsevier publication. Dr. Bertman (photographed above on the right) is a family physician in private practice in Hope Valley, R.I., and clinical assistant professor of family medicine at Brown University in Providence, R.I. He also is the founder and president of AmazingCharts.com, a developer of EHR software. Dr. Skolnik (photographed above on the left) is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia.

Despite the federal government’s pledges of financial incentives and eventual penalties, adoption rates of electronic health record (EHR) systems remain stubbornly low. When a product or service is still underutilized, even after being subsidized by public funds, we have to ask ourselves why.

Many vendors advise physicians that extensive training is needed to learn how to document a note using their system and that they should be prepared to reduce their patient volume throughout the EHR adoption period. This lost patient volume is the direct result of data collection gone awry.

The concept of “usability” is defined as the ease with which people can use a particular product to accomplish defined goals. The lack of usability has been a major cause of dissatisfaction with EHR systems. It has been estimated that one in every three EHR adoptions fail, with poor usability likely a major contributing factor.

Unfortunately, the true experience of an EHR’s usability only occurs well after an EHR contract is signed, training has completed, and the light patient load has ended. That is when the seriousness of poor EHR usability becomes apparent.

To compensate, many physicians end up using templates, macros, and preset lists. This may help alleviate the slowdown caused by an EHR’s poor design, and the resulting patient notes may be full of data, but they often lack any real substance. The real story in each patient encounter is frequently lost. This is a common complaint reported by physicians attempting to use notes generated by an EHR.

To add insult to injury, there is an ever-growing list of horror stories reported by physicians who have given up on their EHRs. Unfortunately, many EHR vendors do not allow dissatisfied users out of their long-term contracts. Or if a vendor does allow a physician out of the contract at a reduced cost, there are often stipulations. One of the physicians we interviewed for this article said that he was negotiating an early termination of his contract, but to do so he had to sign a nondisclosure statement saying he would never comment on his poor experience with that EHR.

So how can a physician avoid ending up with an EHR that may be unusable? It is essential to review the experience of those who have already purchased an EHR. The American Academy of Family Physicians’ Center for Health IT provides a Web site through which members can rate their own EHR based on a five-point scale measuring quality, price, support, ease of use, and impact on productivity. Sorting the available list of 93 EHR systems by rating provides a clear look at overall user satisfaction (www.centerforhit.org).

User satisfaction studies are another indispensable resource. An October 2009 survey of over 3,700 EHR users published by Medscape.com found that over 30% of respondents would not recommend their EHR (http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/709856).

Similarly, “The 2009 EHR User Satisfaction Survey,” published in the November/December 2009 issue of Family Practice Management, provides a troubling look at how physicians rate many of the best known EHRs. This survey’s final question asked 2,012 family physicians if they agreed or disagreed with the following statement, “I am highly satisfied with this EHR system.” Astoundingly, nearly 50% of all respondents said that they would not agree.

With the current rate of physician dissatisfaction, EHR adoption rates will likely remain low despite the government incentives. Perhaps most ironic is that federal financial incentives to adopt EHR systems may contribute to delays in improvements in EHR usability. Rather than allowing competition to reward vendors who produce better software at lower prices, the stimulus money encourages physicians to purchase mediocre software at inflated prices.

As physicians recognize the perils of signing EHR contracts before they truly know if an EHR is usable, they will begin to demand usable, intuitive EHRs. Increasingly, physicians will come to appreciate how financial incentives and initial system costs are dwarfed by the potential reduction in productivity and revenue when a system proves difficult to use. As they gain more exposure to the EHR market, physicians will start to ask the important questions and demand answers about the critical issue of usability, which ultimately makes or breaks their EHR experience.

This column, “EHR Report,” regularly appears in Family Practice News, an Elsevier publication. Dr. Bertman (photographed above on the right) is a family physician in private practice in Hope Valley, R.I., and clinical assistant professor of family medicine at Brown University in Providence, R.I. He also is the founder and president of AmazingCharts.com, a developer of EHR software. Dr. Skolnik (photographed above on the left) is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia.

Despite the federal government’s pledges of financial incentives and eventual penalties, adoption rates of electronic health record (EHR) systems remain stubbornly low. When a product or service is still underutilized, even after being subsidized by public funds, we have to ask ourselves why.

Many vendors advise physicians that extensive training is needed to learn how to document a note using their system and that they should be prepared to reduce their patient volume throughout the EHR adoption period. This lost patient volume is the direct result of data collection gone awry.

The concept of “usability” is defined as the ease with which people can use a particular product to accomplish defined goals. The lack of usability has been a major cause of dissatisfaction with EHR systems. It has been estimated that one in every three EHR adoptions fail, with poor usability likely a major contributing factor.

Unfortunately, the true experience of an EHR’s usability only occurs well after an EHR contract is signed, training has completed, and the light patient load has ended. That is when the seriousness of poor EHR usability becomes apparent.

To compensate, many physicians end up using templates, macros, and preset lists. This may help alleviate the slowdown caused by an EHR’s poor design, and the resulting patient notes may be full of data, but they often lack any real substance. The real story in each patient encounter is frequently lost. This is a common complaint reported by physicians attempting to use notes generated by an EHR.

To add insult to injury, there is an ever-growing list of horror stories reported by physicians who have given up on their EHRs. Unfortunately, many EHR vendors do not allow dissatisfied users out of their long-term contracts. Or if a vendor does allow a physician out of the contract at a reduced cost, there are often stipulations. One of the physicians we interviewed for this article said that he was negotiating an early termination of his contract, but to do so he had to sign a nondisclosure statement saying he would never comment on his poor experience with that EHR.

So how can a physician avoid ending up with an EHR that may be unusable? It is essential to review the experience of those who have already purchased an EHR. The American Academy of Family Physicians’ Center for Health IT provides a Web site through which members can rate their own EHR based on a five-point scale measuring quality, price, support, ease of use, and impact on productivity. Sorting the available list of 93 EHR systems by rating provides a clear look at overall user satisfaction (www.centerforhit.org).

User satisfaction studies are another indispensable resource. An October 2009 survey of over 3,700 EHR users published by Medscape.com found that over 30% of respondents would not recommend their EHR (http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/709856).

Similarly, “The 2009 EHR User Satisfaction Survey,” published in the November/December 2009 issue of Family Practice Management, provides a troubling look at how physicians rate many of the best known EHRs. This survey’s final question asked 2,012 family physicians if they agreed or disagreed with the following statement, “I am highly satisfied with this EHR system.” Astoundingly, nearly 50% of all respondents said that they would not agree.

With the current rate of physician dissatisfaction, EHR adoption rates will likely remain low despite the government incentives. Perhaps most ironic is that federal financial incentives to adopt EHR systems may contribute to delays in improvements in EHR usability. Rather than allowing competition to reward vendors who produce better software at lower prices, the stimulus money encourages physicians to purchase mediocre software at inflated prices.

As physicians recognize the perils of signing EHR contracts before they truly know if an EHR is usable, they will begin to demand usable, intuitive EHRs. Increasingly, physicians will come to appreciate how financial incentives and initial system costs are dwarfed by the potential reduction in productivity and revenue when a system proves difficult to use. As they gain more exposure to the EHR market, physicians will start to ask the important questions and demand answers about the critical issue of usability, which ultimately makes or breaks their EHR experience.

This column, “EHR Report,” regularly appears in Family Practice News, an Elsevier publication. Dr. Bertman (photographed above on the right) is a family physician in private practice in Hope Valley, R.I., and clinical assistant professor of family medicine at Brown University in Providence, R.I. He also is the founder and president of AmazingCharts.com, a developer of EHR software. Dr. Skolnik (photographed above on the left) is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia.