User login

Is the tide turning on the ‘grubby’ affair of EXCEL and the European guidelines?

“I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.” The choice of the secretary general of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery to open with this quote was the first hint that the next presentation at the 2019 annual meeting would be anything but dull. The session chair followed with a reminder to keep the discussion polite and civil.

Presenter David Taggart, MD, PhD, did not disappoint. The professor of cardiovascular surgery at the University of Oxford (England) began with the announcement that he had withdrawn his name from a recent paper in the New England Journal of Medicine. He then proceeded to accuse his coinvestigators of misrepresenting the findings of a major clinical trial.

Dr. Taggart was chair of the surgical committee for the Abbott-sponsored EXCEL trial, which compared two procedures for patients who had blockages in their left main coronary artery: percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) using coronary stents, and coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG). The investigators designed the trial to compare outcomes for the two treatments using a composite endpoint of death, stroke, and MI. The 3-year follow-up data had been published in NEJM without controversy – or, at least, without public controversy.

But when it came time to publish the 5-year follow-up, there was a significantly higher rate of death in the stent group, and both Dr. Taggart and the journal editors were concerned that this finding was being downplayed in the manuscript.

In their comments to the authors, the journal editors had recommended including the mortality difference (unless clearly trivial) ‘”in the concluding statement in the final paragraph.” Yet, the concluding statement of the published paper read that there “was no significant difference between PCI and CABG.”

In Dr. Taggart’s view, that claim was dangerous for patients, and so he was left with no choice but to remove himself as an author, a first for the academic with over 300 scientific papers to his name.

Earlier publications from the EXCEL trial had influenced European treatment guidelines. But subsequent allegations of misconduct and hidden data spurred the EACTS to repudiate those guidelines out of concern “that some results in the EXCEL trial appear to have been concealed and that some patients may therefore have received the wrong clinical advice.”

The controversy pitted cardiothoracic surgeons against interventional cardiologists, who were seen as increasingly encroaching on the surgeons’ turf. Dr. Taggart was a long-time critic of the subspecialty.

Surgeons demanded an independent analysis of the EXCEL trial data – a demand that the investigators have yet to satisfy. Dr. Taggart was the first to speak publicly, but others had major reservations about the trial reporting and conduct years earlier.

Mortality data held back

One such person was Lars Wallentin, MD, a professor of cardiology at Uppsala (Sweden) University Hospital, who chaired the independent committee that monitored the safety and scientific validity of the EXCEL trial.

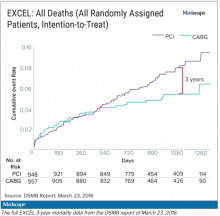

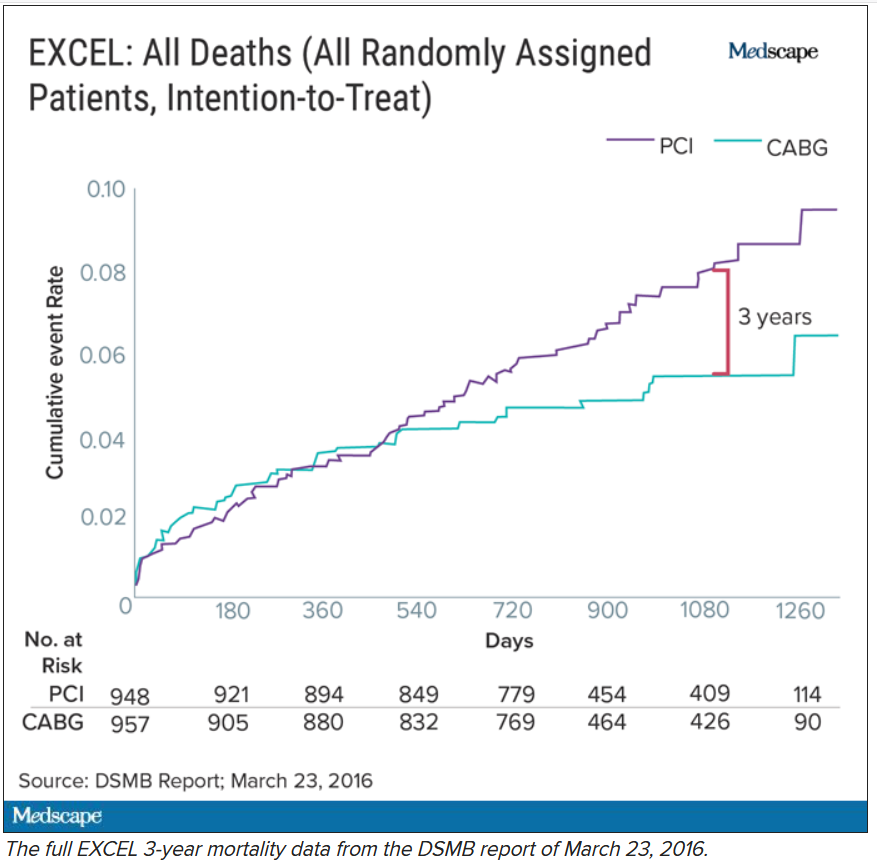

The committee, known as the data and safety monitoring board (DSMB), received a report on March 23, 2016, that showed that increasingly more patients who had received stents were dying, compared with the group of patients that had undergone CABG. A graph of the survival curves showed the gap between the two groups widening after 3 years (Figure 1).

By September of that year, Dr. Wallentin and other members of the DSMB were anxious to share the concerning mortality difference with the broader medical community.

They were aware that EACTS and the European Society of Cardiology had started the process of updating their guidelines on myocardial revascularization, and were keen for the guideline writing committee to see all of the data.

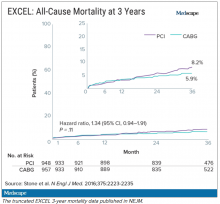

Meanwhile, the trial investigators, led by principal investigator Gregg Stone, MD, then at New York–Presbyterian Hospital and Columbia University Medical Center, were preparing to publish a report of the 3-year outcomes. Recruitment for EXCEL started in September 2010, so at the time of the 3-year analysis in 2016, some patients had been followed up for over 5 years. But the data, published in NEJM in October 2016, were capped at 3 years (Figure 2). It didn’t show the widening gap in late mortality that Dr. Wallentin and the rest of the DSMB had seen.

When asked about this, the investigators said they were transparent about their plans to cap the data at 3 years in an amendment to the study protocol. Stone’s coprincipal investigators were interventional cardiologist Patrick Serruys, MD, then of Imperial College London; and two surgeons: Joseph Sabik, MD, then of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation, and A. Pieter Kappetein, MD, PhD, then at Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam. The four principal investigators all declared financial payments from stent manufacturers either to themselves or their institutions.

Study sponsor Abbott has distanced itself from the decisions made and has referred all questions about the trial to the EXCEL investigators. Charles Simonton, chief medical officer at Abbott (now at Abiomed) was a coauthor on both the 3- and 5-year papers. Dr. Wallentin believes that the sponsor must have been aware of the DSMB’s concerns.

Continuing DSMB concerns

A year later, the DSMB was still troubled. Dr. Wallentin emailed Dr. Stone in September 2017 asking for an updated analysis of the mortality data without any capping in time.

Dr. Wallentin added that he didn’t think that unblinding the mortality results would be an issue at that stage because these were late deaths in a trial where the interventions were long completed. But, he warned, “it might be very concerning if, in the future, suspicions were raised that already available information on mortality was withheld from the cardiology and thoracic surgery community.”

The investigators took a month to respond. They declined the request, saying that the trial was not statistically powered to measure mortality. In his email to Dr. Wallentin, Dr. Stone stressed that they were committed to complete disclosure of all of the EXCEL data and that the responsible time point to unblind was after 4 years. His coprincipal investigators (Dr. Serruys, Dr. Sabik, and Dr. Kappetein) as well as EXCEL statistical committee chair Stuart Pocock, PhD, and Mr. Simonton were all copied on the email.

Dr. Wallentin deferred to the principal investigators’ arguments.

Missing MI data

Death was not the only outcome of the EXCEL trial to draw scrutiny.

The EXCEL investigators used a unique definition of MI that was almost exclusively based on a rise in the cardiac biomarker CK-MB. This protocol definition of MI was later adapted into the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions definition in a paper coauthored by Dr. Stone. The investigators agreed to also measure MIs that met the more commonly used Third Universal Definition as a secondary endpoint. The Third Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction uses a change in biomarkers – preferably troponin or alternatively CK-MB – coupled with other clinical signs.

It is standard practice to report secondary endpoints in any analysis of the main findings of a study. Yet, the EXCEL investigators did not report the universal definition of MI in either the 3-year or 5-year publications.

This is critical because MI according to one definition may not count according to the other, and the final tally could tip the trial results positive, negative, or neutral for coronary stents.

In Dr. Taggart’s opinion, the protocol definition puts CABG at a disadvantage because it uses the same biomarker threshold for procedural-related MI for both PCI and CABG. Because surgery involves more manipulation of the heart, cardiac enzyme levels will naturally be higher after CABG than PCI. These procedure-related enzyme elevations are not “true clinical MIs,” according to Dr. Taggart and others.

Late last year, a dataset containing the 3-year follow-up of EXCEL, including the information on the universal definition of MI, was leaked to the BBC. Working with biostatisticians, the BBC confirmed that according to this definition, there were more MIs in the stent group.

Originally, the investigators disputed the finding, calling the BBC data “imaginary.” They claimed that they were unable to calculate a rate of MI according to the universal definition because they lacked routine collection of troponins, although the universal definition also allows use of CK-MB. They have since published an analysis of 5-year MI data according to the universal definition, which showed twice the rate of MI in the PCI group.

From the leaked data, the BBC calculated the main composite endpoint of death, stroke, and MI using the universal definition of MI. Now the results swung in favor of CABG.

Impact on guidelines

None of this was known at the time the European cardiology societies convened a committee to write their new guidelines on myocardial revascularization. The writing panel disagreed about whether PCI and CABG were equivalent for patients with left main coronary artery disease (CAD).

Besides EXCEL, another study, the NOBLE trial, compared PCI and CABG in left main CAD and came to opposite conclusions – conclusions that matched the leaked data. In that trial, European investigators chose a slightly different primary endpoint: a composite of death, MI, stroke, and the need for a repeat procedure. They used the universal definition of MI exclusively, and notably, they omitted procedural MI from their clinical event count. The results, published at the same time as the EXCEL 3-year findings, suggested that CABG was better.

Given the discrepant findings of two large trials, the guideline committee considered all of the available data comparing the two methods of revascularization for left main CAD. But even then, things weren’t clear-cut. One draft meta-analysis, supported by the National Institute for Health Research, suggested that results were worse for first- and second-generation drug-eluting coronary stents – including those used in EXCEL – compared with surgery.

Another meta-analysis, later published in The Lancet, drew a different conclusion and found that PCI was just as good as surgery. The main author, Stuart Head, a cardiothoracic surgeon on the ESC/EACTS guideline committee, was a research fellow with EXCEL investigator Dr. Kappetein at Erasmus. EXCEL investigators Dr. Stone, Dr. Kappetein, and Dr. Serruys were coauthors of the Lancet meta-analysis.

There was heated discussion about the committee’s draft recommendations, which gave both CABG and PCI a Class IA recommendation in patients with left main CAD and low anatomical complexity. In October 2017, the ESC commissioned an anonymous external reviewer to weigh in. James Brophy, MD, PhD, a cardiologist and professor of medicine and epidemiology at McGill University, Montreal, confirmed that he was the reviewer after he published an updated version in June 2020.

Looking at all of the data available at the time comparing the procedures for left main CAD, Dr. Brophy’s analysis suggested a 73% chance that the excess in death, stroke, or MI represents at least two excess events per 100 patients treated with PCI rather than CABG.

Dr. Brophy thought that most patients would find these differences clinically meaningful and advised against giving both procedures the same class of recommendation. He was also concerned that many readers will skip to the summary recommendation table without reading the entire guideline document.

“I feel this is misleading in its present form,” he wrote in 2017.

Despite Dr. Brophy’s review, the guideline committee stuck with its original recommendations. The final 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization gave equal weight to both CABG and PCI in patients with left main CAD and low anatomical complexity. In contrast, US guidelines do not put PCI and CABG on the same footing for any group of patients with left main CAD.

The lead author of the ESC/EACTS guidelines section on left main disease, and around a third of those on the writing task force, all declared financial payments from stent manufacturers either to themselves or their institutions. The EXCEL principal investigator, Dr. Kappetein, was secretary general of EACTS and oversaw the guidelines process for the surgical organization. He left to work for Medtronic midway through the process and was later joined there by his former research fellow, Stuart Head.

Dr. Brophy said in an interview that given the final guideline recommendations, he assumed that the committee had other reviews and went with the majority opinion.

But not everyone involved in the guidelines saw Dr. Brophy’s review. Nick Freemantle, a statistical reviewer appointed by EACTS, expected to see it but didn’t. This omission calls into question the neutrality of the whole process, in his view.

Mr. Freemantle believes that the deck was stacked so that he only saw the pieces of evidence that supported the conclusions that were already decided and that he was not shown “the bits that don’t fit that neatly.”

“And without that narrative, it all feels a bit grubby, to be honest,” he said.

Professor Barbara Casadei, ESC president, disputed this, saying that the guidelines were approved by all surgical members, including the EACTS council.

Missing from Dr. Brophy’s review were the later data from EXCEL. As he had told the DSMB in 2017, Stone presented the 4-year data from EXCEL at the TCT conference in September 2018. At this point, the analysis showed that 10.3% of people had died after PCI and 7.4% after CABG.

But this presentation was not given much prominence at the conference, which Dr. Stone organized, and occurred during a didactic session in a small room rather than on one of the main stages where the 3-year data from EXCEL were announced with much fanfare. The presentation also took place 3 weeks after the European guidelines were published.

Surgeons withdraw support

After the BBC report last year that the universal definition of MI data had been collected but not published in the 3-year follow-up manuscript, and showed more MI in the PCI group than the protocol definition, the EACTS withdrew its support for the guidelines. The ESC continued to uphold the guidelines «until there is robust scientific evidence (as opposed to allegations) indicating we should do otherwise,” said Ms. Casadei.

A spokesperson for NEJM said the journal stood by the EXCEL papers because “there is no credible harm to patients from the publication of the paper and accurate reporting of trial results.” NEJM has since conducted a review and published a series of letters in response. The letters have reinvigorated rather than appeased the dissenters, as reported by Medscape.

A number of cardiologists and researchers started a petition on change.org to revise the EACTS/ESC left main CAD guidelines, and surgical societies across the globe have written to the editor of NEJM asking him to retract or amend the EXCEL papers.

This has not happened. The journal’s editor maintains that the letters containing the analyses are “sufficient information” to allow readers and guideline authors to “evaluate the trial findings.”

Dr. Taggart was dismissive of that response. “There is still no recognition or acknowledgment that failure to publish these data in 2016 ‘misled’ the guideline writers for the ESC/EACTS guidelines, and there is still no formal correction of the 2016 and 2019 NEJM manuscripts.”

Over a year after the BBC received the leaked data, the EXCEL investigators published an analysis of the primary outcome using the universal definition of MI data in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

It shows 141 events in the PCI arm, compared with 102 in the CABG arm. The investigators acknowledge that the rates of procedural MI differ depending on the definition used. According to their analysis, the protocol definition was predictive of mortality after both treatments, whereas the universal definition of procedural MI was predictive of mortality only after CABG. Not everyone agrees with this interpretation, and an accompanying editorial questioned these conclusions.

For Dr. Wallentin, it’s a relief that these data are in the public domain so that their interpretation and clinical consequences can be “openly discussed.” He hoped that the whole experience will result in something constructive and useful for the future.

As for the guidelines, the tide may be turning.

In a joint statement with EACTS on Oct. 6, 2020, the ESC agreed to review its guidelines for left main disease in the light of emerging, longer-term outcome data from the trials of CABG versus PCI.

Dr. Taggart has no regrets about speaking out despite this being “an exceedingly painful and bruising experience.”

The saga, he said, “reflects very badly on our specialty, the investigators, industry, and the world’s ‘leading’ medical journal.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.” The choice of the secretary general of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery to open with this quote was the first hint that the next presentation at the 2019 annual meeting would be anything but dull. The session chair followed with a reminder to keep the discussion polite and civil.

Presenter David Taggart, MD, PhD, did not disappoint. The professor of cardiovascular surgery at the University of Oxford (England) began with the announcement that he had withdrawn his name from a recent paper in the New England Journal of Medicine. He then proceeded to accuse his coinvestigators of misrepresenting the findings of a major clinical trial.

Dr. Taggart was chair of the surgical committee for the Abbott-sponsored EXCEL trial, which compared two procedures for patients who had blockages in their left main coronary artery: percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) using coronary stents, and coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG). The investigators designed the trial to compare outcomes for the two treatments using a composite endpoint of death, stroke, and MI. The 3-year follow-up data had been published in NEJM without controversy – or, at least, without public controversy.

But when it came time to publish the 5-year follow-up, there was a significantly higher rate of death in the stent group, and both Dr. Taggart and the journal editors were concerned that this finding was being downplayed in the manuscript.

In their comments to the authors, the journal editors had recommended including the mortality difference (unless clearly trivial) ‘”in the concluding statement in the final paragraph.” Yet, the concluding statement of the published paper read that there “was no significant difference between PCI and CABG.”

In Dr. Taggart’s view, that claim was dangerous for patients, and so he was left with no choice but to remove himself as an author, a first for the academic with over 300 scientific papers to his name.

Earlier publications from the EXCEL trial had influenced European treatment guidelines. But subsequent allegations of misconduct and hidden data spurred the EACTS to repudiate those guidelines out of concern “that some results in the EXCEL trial appear to have been concealed and that some patients may therefore have received the wrong clinical advice.”

The controversy pitted cardiothoracic surgeons against interventional cardiologists, who were seen as increasingly encroaching on the surgeons’ turf. Dr. Taggart was a long-time critic of the subspecialty.

Surgeons demanded an independent analysis of the EXCEL trial data – a demand that the investigators have yet to satisfy. Dr. Taggart was the first to speak publicly, but others had major reservations about the trial reporting and conduct years earlier.

Mortality data held back

One such person was Lars Wallentin, MD, a professor of cardiology at Uppsala (Sweden) University Hospital, who chaired the independent committee that monitored the safety and scientific validity of the EXCEL trial.

The committee, known as the data and safety monitoring board (DSMB), received a report on March 23, 2016, that showed that increasingly more patients who had received stents were dying, compared with the group of patients that had undergone CABG. A graph of the survival curves showed the gap between the two groups widening after 3 years (Figure 1).

By September of that year, Dr. Wallentin and other members of the DSMB were anxious to share the concerning mortality difference with the broader medical community.

They were aware that EACTS and the European Society of Cardiology had started the process of updating their guidelines on myocardial revascularization, and were keen for the guideline writing committee to see all of the data.

Meanwhile, the trial investigators, led by principal investigator Gregg Stone, MD, then at New York–Presbyterian Hospital and Columbia University Medical Center, were preparing to publish a report of the 3-year outcomes. Recruitment for EXCEL started in September 2010, so at the time of the 3-year analysis in 2016, some patients had been followed up for over 5 years. But the data, published in NEJM in October 2016, were capped at 3 years (Figure 2). It didn’t show the widening gap in late mortality that Dr. Wallentin and the rest of the DSMB had seen.

When asked about this, the investigators said they were transparent about their plans to cap the data at 3 years in an amendment to the study protocol. Stone’s coprincipal investigators were interventional cardiologist Patrick Serruys, MD, then of Imperial College London; and two surgeons: Joseph Sabik, MD, then of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation, and A. Pieter Kappetein, MD, PhD, then at Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam. The four principal investigators all declared financial payments from stent manufacturers either to themselves or their institutions.

Study sponsor Abbott has distanced itself from the decisions made and has referred all questions about the trial to the EXCEL investigators. Charles Simonton, chief medical officer at Abbott (now at Abiomed) was a coauthor on both the 3- and 5-year papers. Dr. Wallentin believes that the sponsor must have been aware of the DSMB’s concerns.

Continuing DSMB concerns

A year later, the DSMB was still troubled. Dr. Wallentin emailed Dr. Stone in September 2017 asking for an updated analysis of the mortality data without any capping in time.

Dr. Wallentin added that he didn’t think that unblinding the mortality results would be an issue at that stage because these were late deaths in a trial where the interventions were long completed. But, he warned, “it might be very concerning if, in the future, suspicions were raised that already available information on mortality was withheld from the cardiology and thoracic surgery community.”

The investigators took a month to respond. They declined the request, saying that the trial was not statistically powered to measure mortality. In his email to Dr. Wallentin, Dr. Stone stressed that they were committed to complete disclosure of all of the EXCEL data and that the responsible time point to unblind was after 4 years. His coprincipal investigators (Dr. Serruys, Dr. Sabik, and Dr. Kappetein) as well as EXCEL statistical committee chair Stuart Pocock, PhD, and Mr. Simonton were all copied on the email.

Dr. Wallentin deferred to the principal investigators’ arguments.

Missing MI data

Death was not the only outcome of the EXCEL trial to draw scrutiny.

The EXCEL investigators used a unique definition of MI that was almost exclusively based on a rise in the cardiac biomarker CK-MB. This protocol definition of MI was later adapted into the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions definition in a paper coauthored by Dr. Stone. The investigators agreed to also measure MIs that met the more commonly used Third Universal Definition as a secondary endpoint. The Third Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction uses a change in biomarkers – preferably troponin or alternatively CK-MB – coupled with other clinical signs.

It is standard practice to report secondary endpoints in any analysis of the main findings of a study. Yet, the EXCEL investigators did not report the universal definition of MI in either the 3-year or 5-year publications.

This is critical because MI according to one definition may not count according to the other, and the final tally could tip the trial results positive, negative, or neutral for coronary stents.

In Dr. Taggart’s opinion, the protocol definition puts CABG at a disadvantage because it uses the same biomarker threshold for procedural-related MI for both PCI and CABG. Because surgery involves more manipulation of the heart, cardiac enzyme levels will naturally be higher after CABG than PCI. These procedure-related enzyme elevations are not “true clinical MIs,” according to Dr. Taggart and others.

Late last year, a dataset containing the 3-year follow-up of EXCEL, including the information on the universal definition of MI, was leaked to the BBC. Working with biostatisticians, the BBC confirmed that according to this definition, there were more MIs in the stent group.

Originally, the investigators disputed the finding, calling the BBC data “imaginary.” They claimed that they were unable to calculate a rate of MI according to the universal definition because they lacked routine collection of troponins, although the universal definition also allows use of CK-MB. They have since published an analysis of 5-year MI data according to the universal definition, which showed twice the rate of MI in the PCI group.

From the leaked data, the BBC calculated the main composite endpoint of death, stroke, and MI using the universal definition of MI. Now the results swung in favor of CABG.

Impact on guidelines

None of this was known at the time the European cardiology societies convened a committee to write their new guidelines on myocardial revascularization. The writing panel disagreed about whether PCI and CABG were equivalent for patients with left main coronary artery disease (CAD).

Besides EXCEL, another study, the NOBLE trial, compared PCI and CABG in left main CAD and came to opposite conclusions – conclusions that matched the leaked data. In that trial, European investigators chose a slightly different primary endpoint: a composite of death, MI, stroke, and the need for a repeat procedure. They used the universal definition of MI exclusively, and notably, they omitted procedural MI from their clinical event count. The results, published at the same time as the EXCEL 3-year findings, suggested that CABG was better.

Given the discrepant findings of two large trials, the guideline committee considered all of the available data comparing the two methods of revascularization for left main CAD. But even then, things weren’t clear-cut. One draft meta-analysis, supported by the National Institute for Health Research, suggested that results were worse for first- and second-generation drug-eluting coronary stents – including those used in EXCEL – compared with surgery.

Another meta-analysis, later published in The Lancet, drew a different conclusion and found that PCI was just as good as surgery. The main author, Stuart Head, a cardiothoracic surgeon on the ESC/EACTS guideline committee, was a research fellow with EXCEL investigator Dr. Kappetein at Erasmus. EXCEL investigators Dr. Stone, Dr. Kappetein, and Dr. Serruys were coauthors of the Lancet meta-analysis.

There was heated discussion about the committee’s draft recommendations, which gave both CABG and PCI a Class IA recommendation in patients with left main CAD and low anatomical complexity. In October 2017, the ESC commissioned an anonymous external reviewer to weigh in. James Brophy, MD, PhD, a cardiologist and professor of medicine and epidemiology at McGill University, Montreal, confirmed that he was the reviewer after he published an updated version in June 2020.

Looking at all of the data available at the time comparing the procedures for left main CAD, Dr. Brophy’s analysis suggested a 73% chance that the excess in death, stroke, or MI represents at least two excess events per 100 patients treated with PCI rather than CABG.

Dr. Brophy thought that most patients would find these differences clinically meaningful and advised against giving both procedures the same class of recommendation. He was also concerned that many readers will skip to the summary recommendation table without reading the entire guideline document.

“I feel this is misleading in its present form,” he wrote in 2017.

Despite Dr. Brophy’s review, the guideline committee stuck with its original recommendations. The final 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization gave equal weight to both CABG and PCI in patients with left main CAD and low anatomical complexity. In contrast, US guidelines do not put PCI and CABG on the same footing for any group of patients with left main CAD.

The lead author of the ESC/EACTS guidelines section on left main disease, and around a third of those on the writing task force, all declared financial payments from stent manufacturers either to themselves or their institutions. The EXCEL principal investigator, Dr. Kappetein, was secretary general of EACTS and oversaw the guidelines process for the surgical organization. He left to work for Medtronic midway through the process and was later joined there by his former research fellow, Stuart Head.

Dr. Brophy said in an interview that given the final guideline recommendations, he assumed that the committee had other reviews and went with the majority opinion.

But not everyone involved in the guidelines saw Dr. Brophy’s review. Nick Freemantle, a statistical reviewer appointed by EACTS, expected to see it but didn’t. This omission calls into question the neutrality of the whole process, in his view.

Mr. Freemantle believes that the deck was stacked so that he only saw the pieces of evidence that supported the conclusions that were already decided and that he was not shown “the bits that don’t fit that neatly.”

“And without that narrative, it all feels a bit grubby, to be honest,” he said.

Professor Barbara Casadei, ESC president, disputed this, saying that the guidelines were approved by all surgical members, including the EACTS council.

Missing from Dr. Brophy’s review were the later data from EXCEL. As he had told the DSMB in 2017, Stone presented the 4-year data from EXCEL at the TCT conference in September 2018. At this point, the analysis showed that 10.3% of people had died after PCI and 7.4% after CABG.

But this presentation was not given much prominence at the conference, which Dr. Stone organized, and occurred during a didactic session in a small room rather than on one of the main stages where the 3-year data from EXCEL were announced with much fanfare. The presentation also took place 3 weeks after the European guidelines were published.

Surgeons withdraw support

After the BBC report last year that the universal definition of MI data had been collected but not published in the 3-year follow-up manuscript, and showed more MI in the PCI group than the protocol definition, the EACTS withdrew its support for the guidelines. The ESC continued to uphold the guidelines «until there is robust scientific evidence (as opposed to allegations) indicating we should do otherwise,” said Ms. Casadei.

A spokesperson for NEJM said the journal stood by the EXCEL papers because “there is no credible harm to patients from the publication of the paper and accurate reporting of trial results.” NEJM has since conducted a review and published a series of letters in response. The letters have reinvigorated rather than appeased the dissenters, as reported by Medscape.

A number of cardiologists and researchers started a petition on change.org to revise the EACTS/ESC left main CAD guidelines, and surgical societies across the globe have written to the editor of NEJM asking him to retract or amend the EXCEL papers.

This has not happened. The journal’s editor maintains that the letters containing the analyses are “sufficient information” to allow readers and guideline authors to “evaluate the trial findings.”

Dr. Taggart was dismissive of that response. “There is still no recognition or acknowledgment that failure to publish these data in 2016 ‘misled’ the guideline writers for the ESC/EACTS guidelines, and there is still no formal correction of the 2016 and 2019 NEJM manuscripts.”

Over a year after the BBC received the leaked data, the EXCEL investigators published an analysis of the primary outcome using the universal definition of MI data in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

It shows 141 events in the PCI arm, compared with 102 in the CABG arm. The investigators acknowledge that the rates of procedural MI differ depending on the definition used. According to their analysis, the protocol definition was predictive of mortality after both treatments, whereas the universal definition of procedural MI was predictive of mortality only after CABG. Not everyone agrees with this interpretation, and an accompanying editorial questioned these conclusions.

For Dr. Wallentin, it’s a relief that these data are in the public domain so that their interpretation and clinical consequences can be “openly discussed.” He hoped that the whole experience will result in something constructive and useful for the future.

As for the guidelines, the tide may be turning.

In a joint statement with EACTS on Oct. 6, 2020, the ESC agreed to review its guidelines for left main disease in the light of emerging, longer-term outcome data from the trials of CABG versus PCI.

Dr. Taggart has no regrets about speaking out despite this being “an exceedingly painful and bruising experience.”

The saga, he said, “reflects very badly on our specialty, the investigators, industry, and the world’s ‘leading’ medical journal.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.” The choice of the secretary general of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery to open with this quote was the first hint that the next presentation at the 2019 annual meeting would be anything but dull. The session chair followed with a reminder to keep the discussion polite and civil.

Presenter David Taggart, MD, PhD, did not disappoint. The professor of cardiovascular surgery at the University of Oxford (England) began with the announcement that he had withdrawn his name from a recent paper in the New England Journal of Medicine. He then proceeded to accuse his coinvestigators of misrepresenting the findings of a major clinical trial.

Dr. Taggart was chair of the surgical committee for the Abbott-sponsored EXCEL trial, which compared two procedures for patients who had blockages in their left main coronary artery: percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) using coronary stents, and coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG). The investigators designed the trial to compare outcomes for the two treatments using a composite endpoint of death, stroke, and MI. The 3-year follow-up data had been published in NEJM without controversy – or, at least, without public controversy.

But when it came time to publish the 5-year follow-up, there was a significantly higher rate of death in the stent group, and both Dr. Taggart and the journal editors were concerned that this finding was being downplayed in the manuscript.

In their comments to the authors, the journal editors had recommended including the mortality difference (unless clearly trivial) ‘”in the concluding statement in the final paragraph.” Yet, the concluding statement of the published paper read that there “was no significant difference between PCI and CABG.”

In Dr. Taggart’s view, that claim was dangerous for patients, and so he was left with no choice but to remove himself as an author, a first for the academic with over 300 scientific papers to his name.

Earlier publications from the EXCEL trial had influenced European treatment guidelines. But subsequent allegations of misconduct and hidden data spurred the EACTS to repudiate those guidelines out of concern “that some results in the EXCEL trial appear to have been concealed and that some patients may therefore have received the wrong clinical advice.”

The controversy pitted cardiothoracic surgeons against interventional cardiologists, who were seen as increasingly encroaching on the surgeons’ turf. Dr. Taggart was a long-time critic of the subspecialty.

Surgeons demanded an independent analysis of the EXCEL trial data – a demand that the investigators have yet to satisfy. Dr. Taggart was the first to speak publicly, but others had major reservations about the trial reporting and conduct years earlier.

Mortality data held back

One such person was Lars Wallentin, MD, a professor of cardiology at Uppsala (Sweden) University Hospital, who chaired the independent committee that monitored the safety and scientific validity of the EXCEL trial.

The committee, known as the data and safety monitoring board (DSMB), received a report on March 23, 2016, that showed that increasingly more patients who had received stents were dying, compared with the group of patients that had undergone CABG. A graph of the survival curves showed the gap between the two groups widening after 3 years (Figure 1).

By September of that year, Dr. Wallentin and other members of the DSMB were anxious to share the concerning mortality difference with the broader medical community.

They were aware that EACTS and the European Society of Cardiology had started the process of updating their guidelines on myocardial revascularization, and were keen for the guideline writing committee to see all of the data.

Meanwhile, the trial investigators, led by principal investigator Gregg Stone, MD, then at New York–Presbyterian Hospital and Columbia University Medical Center, were preparing to publish a report of the 3-year outcomes. Recruitment for EXCEL started in September 2010, so at the time of the 3-year analysis in 2016, some patients had been followed up for over 5 years. But the data, published in NEJM in October 2016, were capped at 3 years (Figure 2). It didn’t show the widening gap in late mortality that Dr. Wallentin and the rest of the DSMB had seen.

When asked about this, the investigators said they were transparent about their plans to cap the data at 3 years in an amendment to the study protocol. Stone’s coprincipal investigators were interventional cardiologist Patrick Serruys, MD, then of Imperial College London; and two surgeons: Joseph Sabik, MD, then of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation, and A. Pieter Kappetein, MD, PhD, then at Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam. The four principal investigators all declared financial payments from stent manufacturers either to themselves or their institutions.

Study sponsor Abbott has distanced itself from the decisions made and has referred all questions about the trial to the EXCEL investigators. Charles Simonton, chief medical officer at Abbott (now at Abiomed) was a coauthor on both the 3- and 5-year papers. Dr. Wallentin believes that the sponsor must have been aware of the DSMB’s concerns.

Continuing DSMB concerns

A year later, the DSMB was still troubled. Dr. Wallentin emailed Dr. Stone in September 2017 asking for an updated analysis of the mortality data without any capping in time.

Dr. Wallentin added that he didn’t think that unblinding the mortality results would be an issue at that stage because these were late deaths in a trial where the interventions were long completed. But, he warned, “it might be very concerning if, in the future, suspicions were raised that already available information on mortality was withheld from the cardiology and thoracic surgery community.”

The investigators took a month to respond. They declined the request, saying that the trial was not statistically powered to measure mortality. In his email to Dr. Wallentin, Dr. Stone stressed that they were committed to complete disclosure of all of the EXCEL data and that the responsible time point to unblind was after 4 years. His coprincipal investigators (Dr. Serruys, Dr. Sabik, and Dr. Kappetein) as well as EXCEL statistical committee chair Stuart Pocock, PhD, and Mr. Simonton were all copied on the email.

Dr. Wallentin deferred to the principal investigators’ arguments.

Missing MI data

Death was not the only outcome of the EXCEL trial to draw scrutiny.

The EXCEL investigators used a unique definition of MI that was almost exclusively based on a rise in the cardiac biomarker CK-MB. This protocol definition of MI was later adapted into the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions definition in a paper coauthored by Dr. Stone. The investigators agreed to also measure MIs that met the more commonly used Third Universal Definition as a secondary endpoint. The Third Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction uses a change in biomarkers – preferably troponin or alternatively CK-MB – coupled with other clinical signs.

It is standard practice to report secondary endpoints in any analysis of the main findings of a study. Yet, the EXCEL investigators did not report the universal definition of MI in either the 3-year or 5-year publications.

This is critical because MI according to one definition may not count according to the other, and the final tally could tip the trial results positive, negative, or neutral for coronary stents.

In Dr. Taggart’s opinion, the protocol definition puts CABG at a disadvantage because it uses the same biomarker threshold for procedural-related MI for both PCI and CABG. Because surgery involves more manipulation of the heart, cardiac enzyme levels will naturally be higher after CABG than PCI. These procedure-related enzyme elevations are not “true clinical MIs,” according to Dr. Taggart and others.

Late last year, a dataset containing the 3-year follow-up of EXCEL, including the information on the universal definition of MI, was leaked to the BBC. Working with biostatisticians, the BBC confirmed that according to this definition, there were more MIs in the stent group.

Originally, the investigators disputed the finding, calling the BBC data “imaginary.” They claimed that they were unable to calculate a rate of MI according to the universal definition because they lacked routine collection of troponins, although the universal definition also allows use of CK-MB. They have since published an analysis of 5-year MI data according to the universal definition, which showed twice the rate of MI in the PCI group.

From the leaked data, the BBC calculated the main composite endpoint of death, stroke, and MI using the universal definition of MI. Now the results swung in favor of CABG.

Impact on guidelines

None of this was known at the time the European cardiology societies convened a committee to write their new guidelines on myocardial revascularization. The writing panel disagreed about whether PCI and CABG were equivalent for patients with left main coronary artery disease (CAD).

Besides EXCEL, another study, the NOBLE trial, compared PCI and CABG in left main CAD and came to opposite conclusions – conclusions that matched the leaked data. In that trial, European investigators chose a slightly different primary endpoint: a composite of death, MI, stroke, and the need for a repeat procedure. They used the universal definition of MI exclusively, and notably, they omitted procedural MI from their clinical event count. The results, published at the same time as the EXCEL 3-year findings, suggested that CABG was better.

Given the discrepant findings of two large trials, the guideline committee considered all of the available data comparing the two methods of revascularization for left main CAD. But even then, things weren’t clear-cut. One draft meta-analysis, supported by the National Institute for Health Research, suggested that results were worse for first- and second-generation drug-eluting coronary stents – including those used in EXCEL – compared with surgery.

Another meta-analysis, later published in The Lancet, drew a different conclusion and found that PCI was just as good as surgery. The main author, Stuart Head, a cardiothoracic surgeon on the ESC/EACTS guideline committee, was a research fellow with EXCEL investigator Dr. Kappetein at Erasmus. EXCEL investigators Dr. Stone, Dr. Kappetein, and Dr. Serruys were coauthors of the Lancet meta-analysis.

There was heated discussion about the committee’s draft recommendations, which gave both CABG and PCI a Class IA recommendation in patients with left main CAD and low anatomical complexity. In October 2017, the ESC commissioned an anonymous external reviewer to weigh in. James Brophy, MD, PhD, a cardiologist and professor of medicine and epidemiology at McGill University, Montreal, confirmed that he was the reviewer after he published an updated version in June 2020.

Looking at all of the data available at the time comparing the procedures for left main CAD, Dr. Brophy’s analysis suggested a 73% chance that the excess in death, stroke, or MI represents at least two excess events per 100 patients treated with PCI rather than CABG.

Dr. Brophy thought that most patients would find these differences clinically meaningful and advised against giving both procedures the same class of recommendation. He was also concerned that many readers will skip to the summary recommendation table without reading the entire guideline document.

“I feel this is misleading in its present form,” he wrote in 2017.

Despite Dr. Brophy’s review, the guideline committee stuck with its original recommendations. The final 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization gave equal weight to both CABG and PCI in patients with left main CAD and low anatomical complexity. In contrast, US guidelines do not put PCI and CABG on the same footing for any group of patients with left main CAD.

The lead author of the ESC/EACTS guidelines section on left main disease, and around a third of those on the writing task force, all declared financial payments from stent manufacturers either to themselves or their institutions. The EXCEL principal investigator, Dr. Kappetein, was secretary general of EACTS and oversaw the guidelines process for the surgical organization. He left to work for Medtronic midway through the process and was later joined there by his former research fellow, Stuart Head.

Dr. Brophy said in an interview that given the final guideline recommendations, he assumed that the committee had other reviews and went with the majority opinion.

But not everyone involved in the guidelines saw Dr. Brophy’s review. Nick Freemantle, a statistical reviewer appointed by EACTS, expected to see it but didn’t. This omission calls into question the neutrality of the whole process, in his view.

Mr. Freemantle believes that the deck was stacked so that he only saw the pieces of evidence that supported the conclusions that were already decided and that he was not shown “the bits that don’t fit that neatly.”

“And without that narrative, it all feels a bit grubby, to be honest,” he said.

Professor Barbara Casadei, ESC president, disputed this, saying that the guidelines were approved by all surgical members, including the EACTS council.

Missing from Dr. Brophy’s review were the later data from EXCEL. As he had told the DSMB in 2017, Stone presented the 4-year data from EXCEL at the TCT conference in September 2018. At this point, the analysis showed that 10.3% of people had died after PCI and 7.4% after CABG.

But this presentation was not given much prominence at the conference, which Dr. Stone organized, and occurred during a didactic session in a small room rather than on one of the main stages where the 3-year data from EXCEL were announced with much fanfare. The presentation also took place 3 weeks after the European guidelines were published.

Surgeons withdraw support

After the BBC report last year that the universal definition of MI data had been collected but not published in the 3-year follow-up manuscript, and showed more MI in the PCI group than the protocol definition, the EACTS withdrew its support for the guidelines. The ESC continued to uphold the guidelines «until there is robust scientific evidence (as opposed to allegations) indicating we should do otherwise,” said Ms. Casadei.

A spokesperson for NEJM said the journal stood by the EXCEL papers because “there is no credible harm to patients from the publication of the paper and accurate reporting of trial results.” NEJM has since conducted a review and published a series of letters in response. The letters have reinvigorated rather than appeased the dissenters, as reported by Medscape.

A number of cardiologists and researchers started a petition on change.org to revise the EACTS/ESC left main CAD guidelines, and surgical societies across the globe have written to the editor of NEJM asking him to retract or amend the EXCEL papers.

This has not happened. The journal’s editor maintains that the letters containing the analyses are “sufficient information” to allow readers and guideline authors to “evaluate the trial findings.”

Dr. Taggart was dismissive of that response. “There is still no recognition or acknowledgment that failure to publish these data in 2016 ‘misled’ the guideline writers for the ESC/EACTS guidelines, and there is still no formal correction of the 2016 and 2019 NEJM manuscripts.”

Over a year after the BBC received the leaked data, the EXCEL investigators published an analysis of the primary outcome using the universal definition of MI data in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

It shows 141 events in the PCI arm, compared with 102 in the CABG arm. The investigators acknowledge that the rates of procedural MI differ depending on the definition used. According to their analysis, the protocol definition was predictive of mortality after both treatments, whereas the universal definition of procedural MI was predictive of mortality only after CABG. Not everyone agrees with this interpretation, and an accompanying editorial questioned these conclusions.

For Dr. Wallentin, it’s a relief that these data are in the public domain so that their interpretation and clinical consequences can be “openly discussed.” He hoped that the whole experience will result in something constructive and useful for the future.

As for the guidelines, the tide may be turning.

In a joint statement with EACTS on Oct. 6, 2020, the ESC agreed to review its guidelines for left main disease in the light of emerging, longer-term outcome data from the trials of CABG versus PCI.

Dr. Taggart has no regrets about speaking out despite this being “an exceedingly painful and bruising experience.”

The saga, he said, “reflects very badly on our specialty, the investigators, industry, and the world’s ‘leading’ medical journal.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.