User login

Herbal medicine can reduce pain, fatigue in SCD patients

Convention Center, site of

the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting

SAN DIEGO—Results of a phase 1 study suggest that SCD-101, a botanical extract based on an herbal medicine used in Nigeria to treat sickle cell disease (SCD), can reduce pain and fatigue in people with SCD.

The anti-sickling drug also improves the shape of red blood cells but doesn’t produce a change in hemoglobin, according to researchers.

Peter Gillette, MD, of SUNY Downstate in Brooklyn, New York, reported these results at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 121*).

A 6-month phase 2b study conducted previously in Nigeria showed that the herbal medicine Niprisan reduced pain crises and school absenteeism and raised hemoglobin levels compared to placebo.

Based on this study and positive preclinical activity, Dr Gillette and his colleagues undertook a phase 1 study to determine the safety of escalating doses of SCD-101.

Dr Gillette pointed out that Niprisan had been produced commercially in Nigeria but was later removed by the government from the commercial market because of production problems.

The researchers evaluated 23 patients with homozygous SCD or S/beta0 thalassemia.

Patients were aged 18 to 55 years with hemoglobin F of 15% or less and hemoglobin levels between 6.0 and 9.5 g/dL.

Patients could not have had hydroxyurea treatment within 6 months of enrollment, red blood cell transfusion within 3 months, or hospitalization within 4 weeks.

Patients received SCD-101 orally for 28 days administered 2 times daily (BID) or 3 times daily (TID). Doses were 550 mg BID, 1100 mg BID, 2200 mg BID, 4400 mg BID, and 2750 mg TID.

Dr Gillette explained that by distributing the highest dose 3 times over the course of a day, the researchers were able to decrease the side effects of bloating and flatulence on the highest dose.

“Interestingly, with the dose-distributed TID, we found that the hemoglobin had increased by 10%,” he said. “In other words, it appears that the effects are very short-acting, and that by going from a Q12 to a Q8 dosage, the hemoglobin suddenly looks like it might be significant, although this is not a significant change.”

Laboratory outcomes included hemoglobin and hemolysis (LDH, bilirubin, and reticulocyte measurements). Patient-reported outcomes included pain and fatigue.

The most common adverse events (AEs) were pain, flatulence, bloating, diarrhea, constipation, nausea, and headache.

Seven patients in the 2200 mg BID and 4400 mg BID cohorts had dose-related bloating, gas, flatulence or diarrhea, which subsided in a few days.

Patients in the 2750 mg TID cohort did not experience gas side effects.

The gastrointestinal symptoms were most likely dose-related from an excipient of SCD-101, Dr Gillette said.

He and his colleagues found no significant side effects after 28 days of dosing, and there were no dose reductions or interruptions due to drug-related AEs.

There were also no laboratory or electrocardiogram abnormalities.

“Almost all pain AEs stopped by day 13 in 22 of 23 patients,” Dr Gillette said.

“And unexpectedly, patients began to report that they slept better and had improved energy and cognition,” he noted.

Six patients in the 2200 and 4400 mg BID cohorts reported reduced fatigue as measured by the PROMIS fatigue questionnaire.

And 2 patients with ankle ulcers in the 2 highest dose cohorts reported improved healing.

Two weeks after treatment stopped, patients were almost back to baseline in terms of their chronic pain and fatigue levels, Dr Gillette said.

A parallel design, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of the 2750 mg TID dose is ongoing.

Future studies include a crossover-design, exploratory study of the 2750 mg TID dose and a phase 2 parallel design study of the 2200 mg BID and 2750 mg TID doses.

While the researchers are uncertain about the mechanism of action of SCD-101, they hypothesize that its effects could be due to increased vascular flow, increased oxygen delivery, or a reduction in inflammation.

“This is a promising drug potentially for low-income countries or middle-income countries elsewhere in the world where gene therapy and transplant are really not that feasible,” Dr Gillette said.

Research for this study was supported in part by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health of the National Institutes of Health. ![]()

*Information presented at the meeting differs from the abstract.

Convention Center, site of

the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting

SAN DIEGO—Results of a phase 1 study suggest that SCD-101, a botanical extract based on an herbal medicine used in Nigeria to treat sickle cell disease (SCD), can reduce pain and fatigue in people with SCD.

The anti-sickling drug also improves the shape of red blood cells but doesn’t produce a change in hemoglobin, according to researchers.

Peter Gillette, MD, of SUNY Downstate in Brooklyn, New York, reported these results at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 121*).

A 6-month phase 2b study conducted previously in Nigeria showed that the herbal medicine Niprisan reduced pain crises and school absenteeism and raised hemoglobin levels compared to placebo.

Based on this study and positive preclinical activity, Dr Gillette and his colleagues undertook a phase 1 study to determine the safety of escalating doses of SCD-101.

Dr Gillette pointed out that Niprisan had been produced commercially in Nigeria but was later removed by the government from the commercial market because of production problems.

The researchers evaluated 23 patients with homozygous SCD or S/beta0 thalassemia.

Patients were aged 18 to 55 years with hemoglobin F of 15% or less and hemoglobin levels between 6.0 and 9.5 g/dL.

Patients could not have had hydroxyurea treatment within 6 months of enrollment, red blood cell transfusion within 3 months, or hospitalization within 4 weeks.

Patients received SCD-101 orally for 28 days administered 2 times daily (BID) or 3 times daily (TID). Doses were 550 mg BID, 1100 mg BID, 2200 mg BID, 4400 mg BID, and 2750 mg TID.

Dr Gillette explained that by distributing the highest dose 3 times over the course of a day, the researchers were able to decrease the side effects of bloating and flatulence on the highest dose.

“Interestingly, with the dose-distributed TID, we found that the hemoglobin had increased by 10%,” he said. “In other words, it appears that the effects are very short-acting, and that by going from a Q12 to a Q8 dosage, the hemoglobin suddenly looks like it might be significant, although this is not a significant change.”

Laboratory outcomes included hemoglobin and hemolysis (LDH, bilirubin, and reticulocyte measurements). Patient-reported outcomes included pain and fatigue.

The most common adverse events (AEs) were pain, flatulence, bloating, diarrhea, constipation, nausea, and headache.

Seven patients in the 2200 mg BID and 4400 mg BID cohorts had dose-related bloating, gas, flatulence or diarrhea, which subsided in a few days.

Patients in the 2750 mg TID cohort did not experience gas side effects.

The gastrointestinal symptoms were most likely dose-related from an excipient of SCD-101, Dr Gillette said.

He and his colleagues found no significant side effects after 28 days of dosing, and there were no dose reductions or interruptions due to drug-related AEs.

There were also no laboratory or electrocardiogram abnormalities.

“Almost all pain AEs stopped by day 13 in 22 of 23 patients,” Dr Gillette said.

“And unexpectedly, patients began to report that they slept better and had improved energy and cognition,” he noted.

Six patients in the 2200 and 4400 mg BID cohorts reported reduced fatigue as measured by the PROMIS fatigue questionnaire.

And 2 patients with ankle ulcers in the 2 highest dose cohorts reported improved healing.

Two weeks after treatment stopped, patients were almost back to baseline in terms of their chronic pain and fatigue levels, Dr Gillette said.

A parallel design, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of the 2750 mg TID dose is ongoing.

Future studies include a crossover-design, exploratory study of the 2750 mg TID dose and a phase 2 parallel design study of the 2200 mg BID and 2750 mg TID doses.

While the researchers are uncertain about the mechanism of action of SCD-101, they hypothesize that its effects could be due to increased vascular flow, increased oxygen delivery, or a reduction in inflammation.

“This is a promising drug potentially for low-income countries or middle-income countries elsewhere in the world where gene therapy and transplant are really not that feasible,” Dr Gillette said.

Research for this study was supported in part by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health of the National Institutes of Health. ![]()

*Information presented at the meeting differs from the abstract.

Convention Center, site of

the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting

SAN DIEGO—Results of a phase 1 study suggest that SCD-101, a botanical extract based on an herbal medicine used in Nigeria to treat sickle cell disease (SCD), can reduce pain and fatigue in people with SCD.

The anti-sickling drug also improves the shape of red blood cells but doesn’t produce a change in hemoglobin, according to researchers.

Peter Gillette, MD, of SUNY Downstate in Brooklyn, New York, reported these results at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 121*).

A 6-month phase 2b study conducted previously in Nigeria showed that the herbal medicine Niprisan reduced pain crises and school absenteeism and raised hemoglobin levels compared to placebo.

Based on this study and positive preclinical activity, Dr Gillette and his colleagues undertook a phase 1 study to determine the safety of escalating doses of SCD-101.

Dr Gillette pointed out that Niprisan had been produced commercially in Nigeria but was later removed by the government from the commercial market because of production problems.

The researchers evaluated 23 patients with homozygous SCD or S/beta0 thalassemia.

Patients were aged 18 to 55 years with hemoglobin F of 15% or less and hemoglobin levels between 6.0 and 9.5 g/dL.

Patients could not have had hydroxyurea treatment within 6 months of enrollment, red blood cell transfusion within 3 months, or hospitalization within 4 weeks.

Patients received SCD-101 orally for 28 days administered 2 times daily (BID) or 3 times daily (TID). Doses were 550 mg BID, 1100 mg BID, 2200 mg BID, 4400 mg BID, and 2750 mg TID.

Dr Gillette explained that by distributing the highest dose 3 times over the course of a day, the researchers were able to decrease the side effects of bloating and flatulence on the highest dose.

“Interestingly, with the dose-distributed TID, we found that the hemoglobin had increased by 10%,” he said. “In other words, it appears that the effects are very short-acting, and that by going from a Q12 to a Q8 dosage, the hemoglobin suddenly looks like it might be significant, although this is not a significant change.”

Laboratory outcomes included hemoglobin and hemolysis (LDH, bilirubin, and reticulocyte measurements). Patient-reported outcomes included pain and fatigue.

The most common adverse events (AEs) were pain, flatulence, bloating, diarrhea, constipation, nausea, and headache.

Seven patients in the 2200 mg BID and 4400 mg BID cohorts had dose-related bloating, gas, flatulence or diarrhea, which subsided in a few days.

Patients in the 2750 mg TID cohort did not experience gas side effects.

The gastrointestinal symptoms were most likely dose-related from an excipient of SCD-101, Dr Gillette said.

He and his colleagues found no significant side effects after 28 days of dosing, and there were no dose reductions or interruptions due to drug-related AEs.

There were also no laboratory or electrocardiogram abnormalities.

“Almost all pain AEs stopped by day 13 in 22 of 23 patients,” Dr Gillette said.

“And unexpectedly, patients began to report that they slept better and had improved energy and cognition,” he noted.

Six patients in the 2200 and 4400 mg BID cohorts reported reduced fatigue as measured by the PROMIS fatigue questionnaire.

And 2 patients with ankle ulcers in the 2 highest dose cohorts reported improved healing.

Two weeks after treatment stopped, patients were almost back to baseline in terms of their chronic pain and fatigue levels, Dr Gillette said.

A parallel design, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of the 2750 mg TID dose is ongoing.

Future studies include a crossover-design, exploratory study of the 2750 mg TID dose and a phase 2 parallel design study of the 2200 mg BID and 2750 mg TID doses.

While the researchers are uncertain about the mechanism of action of SCD-101, they hypothesize that its effects could be due to increased vascular flow, increased oxygen delivery, or a reduction in inflammation.

“This is a promising drug potentially for low-income countries or middle-income countries elsewhere in the world where gene therapy and transplant are really not that feasible,” Dr Gillette said.

Research for this study was supported in part by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health of the National Institutes of Health. ![]()

*Information presented at the meeting differs from the abstract.

Combine flow and HTS for sensitive MRD detection in CLL, speaker says

laser beam

Photo courtesy of NIH

NEW YORK—Combining 2 technologies—flow cytometry and high-throughput sequencing (HTS)—produces a very sensitive approach to detecting minimal residual disease (MRD) in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), according to a speaker at Lymphoma & Myeloma 2016.

The approach is both reproducible and widely accessible, added the speaker, Peter Hillmen, MB ChB, PhD, of St James’s University Hospital in Leeds, UK.

“PCR [polymerase chain reaction] is more sensitive than flow cytometry,” he noted, “but it is probably not necessary to assess response by that criteria.”

Features to consider when choosing a technology for detecting MRD include sensitivity, specificity for the patient and/or the disease, applicability to all patients or to an individual, the platform—flow cytometry, conventional molecular PCR, or next-generation sequencing—and which tissue to use, blood or bone marrow.

In the era of immunotherapy, Dr Hillmen said, assessment should be performed at least 2 months after completion of immunotherapy to get a reliable assessment of MRD, particularly after treatment with alemtuzumab, rituximab, and other antibodies targeting CLL.

History of MRD analysis

The definition of MRD hasn’t changed since 2008, when the International Workshop on CLL updated National Cancer Institute guidelines. It is still 1 single cell in 10,000 (10-4) leukocytes, regardless of the tissue used.

Prior to the mid-1990s, there were limited options for assessing MRD, Dr Hillmen said.

Based on the profound remissions patients experienced with alemtuzumab, investigators began to develop assays to assess MRD.

“[W]e started standardizing these assays around 2007,” Dr Hillmen said, and a standardized assay was used prospectively in clinical trials beginning in 2012.

Technologies

Several technologies can be used to assess MRD.

Flow cytometry using 6 colors or 8 colors—to simplify the assay and to make it more sensitive—is a multiparameter assessment of CLL phenotype that is not clonality-based.

Allele-specific oligonucleotide PCR (ASO-PCR) is laborious to perform, Dr Hillmen said, but it’s very sensitive.

“[I]t probably shouldn’t be considered as an MRD test,” he said, since it uses patient-specific primers, not consensus primers.

HTS provides an increasing amount of information on B-cell sequences and enumeration of the CLL-specific immunoglobulin gene, “and I would move it towards being approved as a regulatory endpoint,” Dr Hillmen asserted.

Flow cytometry and HTS

A consensus document by the European Research Initiative on CLL (ERIC) identified and validated a flow cytometric approach to MRD assessment in parallel with HTS.

According to the ERIC investigators, flow cytometry had to utilize a core panel of 6 antigens used by most labs—CD19, CD20, CD5, CD43, CD79b, and CD81. And the markers used had to quantitate cells to a level of 0.01% (10-4).

Assays had to be independent and compatible with older, established therapies as well as newer treatments.

For example, 6-color flow had to be effective with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (FCR) regimens, as well as effective with the novel agents ibrutinib and venetoclax (ABT-199).

Compared to PCR, multiparameter flow cytometry is more convenient, Dr Hillmen noted.

And while PCR is more sensitive than flow cytometry (sensitive to 10-5 to 10-6), it is more difficult to apply to large clinical trials because the assay must be validated for each patient.

The investigators validated the flow cytometric approach in 450 patients on FCR-type therapy enrolled in the ADMIRE and ARCTIC trials.

They assessed MRD in patients’ bone marrow 3 months after the last course of treatment and presented the data at EHA 2015 (Rawstron AC, abstract S794).

They found that all patients who were MRD negative, including 9 patients with partial responses, achieved a significantly better progression-free survival (PFS) than patients who had achieved a complete response but were still MRD positive.

The parallel analysis of HTS showed good concordance with flow cytometry at the 0.01% (10-4) level.

Peripheral blood or bone marrow?

“[T]he blood is a tissue which can be used, but it’s certainly not as sensitive as the bone marrow,” Dr Hillmen said. “And depending upon what we are using MRD for, the marrow is probably a better tissue, with some exceptions.”

Data from the ADMIRE and ARCTIC trials confirmed that 177 patients on FCR-based therapy who were negative in the bone marrow were always negative in the blood. However, a quarter of patients negative in the blood were positive in the bone marrow.

Investigators followed the same patients on FCR-based therapy for 3 years and found no difference in outcome in terms of PFS for patients negative in peripheral blood and positive in the bone marrow (PB-/BM+) and those negative in peripheral blood and negative in the bone marrow (PB-/BM-) (Rawstron abstract S794).

But for patients on alemtuzumab, with the same analysis, those who were PB-/BM+ did less well and had similar PFS to those who were PB+/BM+.

And at a follow-up of 4 years or longer, patients on FCR-based therapy who were PB-/BM- had superior outcomes than those who were PB-/BM+.

“So as a predictive marker, the bone marrow is a better tissue to look at, but peripheral blood negativity also can predict with FCR but not with agents such as alemtuzumab,” Dr Hillmen summarized.

Prognostic value of MRD assessment

Multivariate analysis of a 10-year follow-up of 133 CLL patients revealed that MRD level and adverse cytogenetics were the only significant parameters in terms of PFS.

And in terms of overall survival (OS), MRD level, prior treatment, Binet stage, and age were significant.

Sixty-seven of these patients had been treated with chemoimmunotherapy, 31 with single-agent chemotherapy, 7 had autologous stem cell transplants, and 28 had prior exposure to alemtuzumab.

In terms of survival beyond 10 or 15 years, previously untreated patients who were MRD negative after their first therapy had significantly better PFS and OS than previously treated patients who were MRD negative and patients with or without prior treatment who were MRD positive (P<0.001).

“Consistently, MRD, regardless of therapy, is the most important prognostic marker,” Dr Hillmen said.

Data from MD Anderson Cancer Center showed that 75% of patients treated first-line with FCR who achieved a complete response were MRD negative.

And patients who achieved MRD negativity had significantly better PFS (P<0.001) and OS (P=0.006) than patients who remained MRD positive.

In the ADMIRE and ARCTIC trials mentioned earlier, patients who achieved MRD negativity in the marrow at 3 months post-therapy also had significantly better PFS (P<0.0001) and OS (P=0.0002) than those who were MRD positive.

For every log of positivity, Dr Hillmen said, patients have a worse survival. Conversely, for every log reduction in MRD level, there is a 33% reduction in risk for disease progression.

“MRD is probably the most important prognostic marker we have,” he said. “We need to look at MRD levels with novel agents and use it to define duration of therapy, maybe use it to define additional therapy if patients are stalled in their response.” ![]()

laser beam

Photo courtesy of NIH

NEW YORK—Combining 2 technologies—flow cytometry and high-throughput sequencing (HTS)—produces a very sensitive approach to detecting minimal residual disease (MRD) in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), according to a speaker at Lymphoma & Myeloma 2016.

The approach is both reproducible and widely accessible, added the speaker, Peter Hillmen, MB ChB, PhD, of St James’s University Hospital in Leeds, UK.

“PCR [polymerase chain reaction] is more sensitive than flow cytometry,” he noted, “but it is probably not necessary to assess response by that criteria.”

Features to consider when choosing a technology for detecting MRD include sensitivity, specificity for the patient and/or the disease, applicability to all patients or to an individual, the platform—flow cytometry, conventional molecular PCR, or next-generation sequencing—and which tissue to use, blood or bone marrow.

In the era of immunotherapy, Dr Hillmen said, assessment should be performed at least 2 months after completion of immunotherapy to get a reliable assessment of MRD, particularly after treatment with alemtuzumab, rituximab, and other antibodies targeting CLL.

History of MRD analysis

The definition of MRD hasn’t changed since 2008, when the International Workshop on CLL updated National Cancer Institute guidelines. It is still 1 single cell in 10,000 (10-4) leukocytes, regardless of the tissue used.

Prior to the mid-1990s, there were limited options for assessing MRD, Dr Hillmen said.

Based on the profound remissions patients experienced with alemtuzumab, investigators began to develop assays to assess MRD.

“[W]e started standardizing these assays around 2007,” Dr Hillmen said, and a standardized assay was used prospectively in clinical trials beginning in 2012.

Technologies

Several technologies can be used to assess MRD.

Flow cytometry using 6 colors or 8 colors—to simplify the assay and to make it more sensitive—is a multiparameter assessment of CLL phenotype that is not clonality-based.

Allele-specific oligonucleotide PCR (ASO-PCR) is laborious to perform, Dr Hillmen said, but it’s very sensitive.

“[I]t probably shouldn’t be considered as an MRD test,” he said, since it uses patient-specific primers, not consensus primers.

HTS provides an increasing amount of information on B-cell sequences and enumeration of the CLL-specific immunoglobulin gene, “and I would move it towards being approved as a regulatory endpoint,” Dr Hillmen asserted.

Flow cytometry and HTS

A consensus document by the European Research Initiative on CLL (ERIC) identified and validated a flow cytometric approach to MRD assessment in parallel with HTS.

According to the ERIC investigators, flow cytometry had to utilize a core panel of 6 antigens used by most labs—CD19, CD20, CD5, CD43, CD79b, and CD81. And the markers used had to quantitate cells to a level of 0.01% (10-4).

Assays had to be independent and compatible with older, established therapies as well as newer treatments.

For example, 6-color flow had to be effective with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (FCR) regimens, as well as effective with the novel agents ibrutinib and venetoclax (ABT-199).

Compared to PCR, multiparameter flow cytometry is more convenient, Dr Hillmen noted.

And while PCR is more sensitive than flow cytometry (sensitive to 10-5 to 10-6), it is more difficult to apply to large clinical trials because the assay must be validated for each patient.

The investigators validated the flow cytometric approach in 450 patients on FCR-type therapy enrolled in the ADMIRE and ARCTIC trials.

They assessed MRD in patients’ bone marrow 3 months after the last course of treatment and presented the data at EHA 2015 (Rawstron AC, abstract S794).

They found that all patients who were MRD negative, including 9 patients with partial responses, achieved a significantly better progression-free survival (PFS) than patients who had achieved a complete response but were still MRD positive.

The parallel analysis of HTS showed good concordance with flow cytometry at the 0.01% (10-4) level.

Peripheral blood or bone marrow?

“[T]he blood is a tissue which can be used, but it’s certainly not as sensitive as the bone marrow,” Dr Hillmen said. “And depending upon what we are using MRD for, the marrow is probably a better tissue, with some exceptions.”

Data from the ADMIRE and ARCTIC trials confirmed that 177 patients on FCR-based therapy who were negative in the bone marrow were always negative in the blood. However, a quarter of patients negative in the blood were positive in the bone marrow.

Investigators followed the same patients on FCR-based therapy for 3 years and found no difference in outcome in terms of PFS for patients negative in peripheral blood and positive in the bone marrow (PB-/BM+) and those negative in peripheral blood and negative in the bone marrow (PB-/BM-) (Rawstron abstract S794).

But for patients on alemtuzumab, with the same analysis, those who were PB-/BM+ did less well and had similar PFS to those who were PB+/BM+.

And at a follow-up of 4 years or longer, patients on FCR-based therapy who were PB-/BM- had superior outcomes than those who were PB-/BM+.

“So as a predictive marker, the bone marrow is a better tissue to look at, but peripheral blood negativity also can predict with FCR but not with agents such as alemtuzumab,” Dr Hillmen summarized.

Prognostic value of MRD assessment

Multivariate analysis of a 10-year follow-up of 133 CLL patients revealed that MRD level and adverse cytogenetics were the only significant parameters in terms of PFS.

And in terms of overall survival (OS), MRD level, prior treatment, Binet stage, and age were significant.

Sixty-seven of these patients had been treated with chemoimmunotherapy, 31 with single-agent chemotherapy, 7 had autologous stem cell transplants, and 28 had prior exposure to alemtuzumab.

In terms of survival beyond 10 or 15 years, previously untreated patients who were MRD negative after their first therapy had significantly better PFS and OS than previously treated patients who were MRD negative and patients with or without prior treatment who were MRD positive (P<0.001).

“Consistently, MRD, regardless of therapy, is the most important prognostic marker,” Dr Hillmen said.

Data from MD Anderson Cancer Center showed that 75% of patients treated first-line with FCR who achieved a complete response were MRD negative.

And patients who achieved MRD negativity had significantly better PFS (P<0.001) and OS (P=0.006) than patients who remained MRD positive.

In the ADMIRE and ARCTIC trials mentioned earlier, patients who achieved MRD negativity in the marrow at 3 months post-therapy also had significantly better PFS (P<0.0001) and OS (P=0.0002) than those who were MRD positive.

For every log of positivity, Dr Hillmen said, patients have a worse survival. Conversely, for every log reduction in MRD level, there is a 33% reduction in risk for disease progression.

“MRD is probably the most important prognostic marker we have,” he said. “We need to look at MRD levels with novel agents and use it to define duration of therapy, maybe use it to define additional therapy if patients are stalled in their response.” ![]()

laser beam

Photo courtesy of NIH

NEW YORK—Combining 2 technologies—flow cytometry and high-throughput sequencing (HTS)—produces a very sensitive approach to detecting minimal residual disease (MRD) in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), according to a speaker at Lymphoma & Myeloma 2016.

The approach is both reproducible and widely accessible, added the speaker, Peter Hillmen, MB ChB, PhD, of St James’s University Hospital in Leeds, UK.

“PCR [polymerase chain reaction] is more sensitive than flow cytometry,” he noted, “but it is probably not necessary to assess response by that criteria.”

Features to consider when choosing a technology for detecting MRD include sensitivity, specificity for the patient and/or the disease, applicability to all patients or to an individual, the platform—flow cytometry, conventional molecular PCR, or next-generation sequencing—and which tissue to use, blood or bone marrow.

In the era of immunotherapy, Dr Hillmen said, assessment should be performed at least 2 months after completion of immunotherapy to get a reliable assessment of MRD, particularly after treatment with alemtuzumab, rituximab, and other antibodies targeting CLL.

History of MRD analysis

The definition of MRD hasn’t changed since 2008, when the International Workshop on CLL updated National Cancer Institute guidelines. It is still 1 single cell in 10,000 (10-4) leukocytes, regardless of the tissue used.

Prior to the mid-1990s, there were limited options for assessing MRD, Dr Hillmen said.

Based on the profound remissions patients experienced with alemtuzumab, investigators began to develop assays to assess MRD.

“[W]e started standardizing these assays around 2007,” Dr Hillmen said, and a standardized assay was used prospectively in clinical trials beginning in 2012.

Technologies

Several technologies can be used to assess MRD.

Flow cytometry using 6 colors or 8 colors—to simplify the assay and to make it more sensitive—is a multiparameter assessment of CLL phenotype that is not clonality-based.

Allele-specific oligonucleotide PCR (ASO-PCR) is laborious to perform, Dr Hillmen said, but it’s very sensitive.

“[I]t probably shouldn’t be considered as an MRD test,” he said, since it uses patient-specific primers, not consensus primers.

HTS provides an increasing amount of information on B-cell sequences and enumeration of the CLL-specific immunoglobulin gene, “and I would move it towards being approved as a regulatory endpoint,” Dr Hillmen asserted.

Flow cytometry and HTS

A consensus document by the European Research Initiative on CLL (ERIC) identified and validated a flow cytometric approach to MRD assessment in parallel with HTS.

According to the ERIC investigators, flow cytometry had to utilize a core panel of 6 antigens used by most labs—CD19, CD20, CD5, CD43, CD79b, and CD81. And the markers used had to quantitate cells to a level of 0.01% (10-4).

Assays had to be independent and compatible with older, established therapies as well as newer treatments.

For example, 6-color flow had to be effective with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (FCR) regimens, as well as effective with the novel agents ibrutinib and venetoclax (ABT-199).

Compared to PCR, multiparameter flow cytometry is more convenient, Dr Hillmen noted.

And while PCR is more sensitive than flow cytometry (sensitive to 10-5 to 10-6), it is more difficult to apply to large clinical trials because the assay must be validated for each patient.

The investigators validated the flow cytometric approach in 450 patients on FCR-type therapy enrolled in the ADMIRE and ARCTIC trials.

They assessed MRD in patients’ bone marrow 3 months after the last course of treatment and presented the data at EHA 2015 (Rawstron AC, abstract S794).

They found that all patients who were MRD negative, including 9 patients with partial responses, achieved a significantly better progression-free survival (PFS) than patients who had achieved a complete response but were still MRD positive.

The parallel analysis of HTS showed good concordance with flow cytometry at the 0.01% (10-4) level.

Peripheral blood or bone marrow?

“[T]he blood is a tissue which can be used, but it’s certainly not as sensitive as the bone marrow,” Dr Hillmen said. “And depending upon what we are using MRD for, the marrow is probably a better tissue, with some exceptions.”

Data from the ADMIRE and ARCTIC trials confirmed that 177 patients on FCR-based therapy who were negative in the bone marrow were always negative in the blood. However, a quarter of patients negative in the blood were positive in the bone marrow.

Investigators followed the same patients on FCR-based therapy for 3 years and found no difference in outcome in terms of PFS for patients negative in peripheral blood and positive in the bone marrow (PB-/BM+) and those negative in peripheral blood and negative in the bone marrow (PB-/BM-) (Rawstron abstract S794).

But for patients on alemtuzumab, with the same analysis, those who were PB-/BM+ did less well and had similar PFS to those who were PB+/BM+.

And at a follow-up of 4 years or longer, patients on FCR-based therapy who were PB-/BM- had superior outcomes than those who were PB-/BM+.

“So as a predictive marker, the bone marrow is a better tissue to look at, but peripheral blood negativity also can predict with FCR but not with agents such as alemtuzumab,” Dr Hillmen summarized.

Prognostic value of MRD assessment

Multivariate analysis of a 10-year follow-up of 133 CLL patients revealed that MRD level and adverse cytogenetics were the only significant parameters in terms of PFS.

And in terms of overall survival (OS), MRD level, prior treatment, Binet stage, and age were significant.

Sixty-seven of these patients had been treated with chemoimmunotherapy, 31 with single-agent chemotherapy, 7 had autologous stem cell transplants, and 28 had prior exposure to alemtuzumab.

In terms of survival beyond 10 or 15 years, previously untreated patients who were MRD negative after their first therapy had significantly better PFS and OS than previously treated patients who were MRD negative and patients with or without prior treatment who were MRD positive (P<0.001).

“Consistently, MRD, regardless of therapy, is the most important prognostic marker,” Dr Hillmen said.

Data from MD Anderson Cancer Center showed that 75% of patients treated first-line with FCR who achieved a complete response were MRD negative.

And patients who achieved MRD negativity had significantly better PFS (P<0.001) and OS (P=0.006) than patients who remained MRD positive.

In the ADMIRE and ARCTIC trials mentioned earlier, patients who achieved MRD negativity in the marrow at 3 months post-therapy also had significantly better PFS (P<0.0001) and OS (P=0.0002) than those who were MRD positive.

For every log of positivity, Dr Hillmen said, patients have a worse survival. Conversely, for every log reduction in MRD level, there is a 33% reduction in risk for disease progression.

“MRD is probably the most important prognostic marker we have,” he said. “We need to look at MRD levels with novel agents and use it to define duration of therapy, maybe use it to define additional therapy if patients are stalled in their response.” ![]()

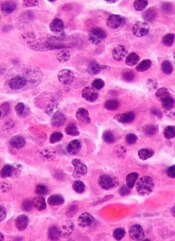

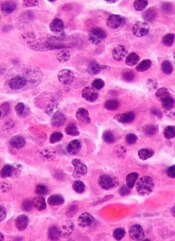

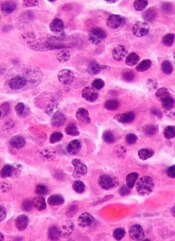

Rethinking testing in multiple myeloma

NEW YORK—As the number of therapeutic options for multiple myeloma (MM) increases, so too does the need to reassess prognostic markers for the disease, according to a speaker at Lymphoma & Myeloma 2016.

“A good prognosticator for one patient may have little meaning for another patient,” said Scott Ely, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, New York.

“It’s really important before doing any testing to ask, ‘Will the result of this test affect patient care?’”

To answer this question, Dr Ely reviewed the different testing methods used in MM patients and explained the advantages of each.

“[I]t’s really important to understand that a lot of methods are really great for research but don’t work or are not feasible for real-life diagnostic purposes,” he added.

Dr Ely also said it’s important to consider who wants the data, how much the test costs, and who will pay for it, keeping in mind that, these days, the patient’s share of the bill is increasing.

Dr Ely stressed that, until more precise targets or a better understanding of drug mechanisms exist, clinical features—patient age, performance status or frailty, renal function, and disease stage—remain the most important prognosticators.

“But still, 2 patients in the same box based on clinical features will often have very different outcomes,” he said. “So in addition to clinical factors, we need prognosticators for tumor cell behavior. We need to know how fast they are growing and how they will respond to treatment.”

Methods to assess myeloma cell proliferation

Cytogenetics (FISH), gene array technology, and genomics using next-generation sequencing can provide some information, but they are not necessarily good methods to assess proliferation, Dr Ely explained.

To determine the proliferation rate of a patient’s cancer, you can look at tens of thousands of genes by gene array, he said, “or you can just look at one thing, which is Ki67.”

If the cell has Ki67, it’s proliferating, and if it doesn’t have Ki67, it’s not.

“Often, looking at all the other upstream molecules can be confusing and even misleading,” he noted. “So Ki67 is the best way to look for proliferation when it comes to myeloma.”

Other methods include the plasma cell labeling index (PCLI), gene expression profiling, flow cytometry, and multiplex immunohistochemistry (mIHC).

Dr Ely, as a hematopathologist, has found IHC to be the best method to determine proliferation, most likely because the other methods use bone marrow aspirate and IHC uses core biopsy of histologic sections.

It’s the gold standard, he said, for determining the percentage of plasma cells because core biopsy takes a “complete, intact piece of marrow that’s truly representative of what’s going on in the patient.”

In a study of more than 350 bone marrow samples comparing core biopsy with aspirate smears, plasma cells were under-represented in approximately half the aspirate specimens by about 20%.

In addition, Dr Ely noted that myeloma cells die very quickly once they are removed from the stroma.

“So if you take myeloma cells out as an aspirate,” he said, “myeloma cells die and others survive.”

And if the aspirate is sent overnight to the lab, the number of plasma cells in the specimen will already be reduced when the lab gets it.

Aspirates are best for leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes, Dr Ely said, while core biopsies are best for lymphoma and myeloma.

Plasma cell proliferation indices

Proliferation is a myeloma-defining criterion, Dr Ely said. It predicts an 80% probability of progression in 2 years.

And PCLI has shown conclusively that plasma cell proliferation is a good prognosticator in all types of myeloma patients. However, it is not really feasible to use or easy to perform.

On the other hand, core biopsy combined with IHC is a feasible way of measuring plasma cell proliferation for routine clinical use.

Using standard IHC, it’s difficult to distinguish proliferating from non-proliferating cells, Dr Ely said.

“The solution to this problem is multiplex IHC,” he said, using 3 stains—red for CD138 (the plasma cell marker), brown for Ki67 (the proliferation marker), and blue as a negative nuclear counter stain.

A red membrane around the stained cell indicates a myeloma cell. Non-proliferating MM cells have blue nuclei, and proliferating MM cells have brown nuclei.

This assay is called the plasma cell proliferation index (PCPI).

“[A]ny lab that can do standard IHC can do multiplex IHC,” Dr Ely added.

It uses the same machines, the same reagents, the same expertise, and it’s easy to set up.

Validation studies

Dr Ely and his colleagues performed extensive laboratory validation to make sure the new PCPI correlated with the old PCLI.

They also performed 3 clinical validation studies, the first in bone marrow transplant patients. The investigators followed the patients for 12 years and found the PCPI correlated with survival.

The investigators performed a second clinical validation in 151 newly diagnosed patients. On multivariate analysis, the team found PCPI to be an independent prognostic indicator.

Each 1% increase in PCPI was associated with a 3% increased risk of disease progression (hazard ratio=1.03, 95% CI, 1.01-1.05, P=0.02).

The third clinical validation the investigators conducted was a retrospective cohort study in which they evaluated the effect of rising PCPI at relapse in 37 patients. The team defined rising PCPI as a 5% or greater increase in plasma cells.

Nineteen patients had a rising PCPI, and 17 patients had stable or decreased PCPI.

Patients with a rising PCPI at relapse had a shorter median overall survival than patients with stable or decreased PCPI—72 months and not reached, respectively (P=0.0069).

Patients with a rising PCPI also had a shorter median progression-free survival on first post-relapse treatment compared to patients with stable or decreased PCPI—25 months and 47 months, respectively (P=0.036).

“It’s also important to note that if you’re getting high-risk by PCPI plus β2-microglobulin albumin, I’d advise that, for all high-risk patients, getting the cytogenetics doesn’t really help,” Dr Ely said

Three patients considered high-risk by cytogenetics were standard-risk by PCPI plus β2 microglobulin.

“So we found that cytogenetics isn’t really adding anything except the cost,” Dr Ely asserted.

Other labs are now using PCPI for prognostication, he noted, adding, “We hope PCPI will be incorporated into the International Myeloma Working Group diagnosis of MM.” ![]()

NEW YORK—As the number of therapeutic options for multiple myeloma (MM) increases, so too does the need to reassess prognostic markers for the disease, according to a speaker at Lymphoma & Myeloma 2016.

“A good prognosticator for one patient may have little meaning for another patient,” said Scott Ely, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, New York.

“It’s really important before doing any testing to ask, ‘Will the result of this test affect patient care?’”

To answer this question, Dr Ely reviewed the different testing methods used in MM patients and explained the advantages of each.

“[I]t’s really important to understand that a lot of methods are really great for research but don’t work or are not feasible for real-life diagnostic purposes,” he added.

Dr Ely also said it’s important to consider who wants the data, how much the test costs, and who will pay for it, keeping in mind that, these days, the patient’s share of the bill is increasing.

Dr Ely stressed that, until more precise targets or a better understanding of drug mechanisms exist, clinical features—patient age, performance status or frailty, renal function, and disease stage—remain the most important prognosticators.

“But still, 2 patients in the same box based on clinical features will often have very different outcomes,” he said. “So in addition to clinical factors, we need prognosticators for tumor cell behavior. We need to know how fast they are growing and how they will respond to treatment.”

Methods to assess myeloma cell proliferation

Cytogenetics (FISH), gene array technology, and genomics using next-generation sequencing can provide some information, but they are not necessarily good methods to assess proliferation, Dr Ely explained.

To determine the proliferation rate of a patient’s cancer, you can look at tens of thousands of genes by gene array, he said, “or you can just look at one thing, which is Ki67.”

If the cell has Ki67, it’s proliferating, and if it doesn’t have Ki67, it’s not.

“Often, looking at all the other upstream molecules can be confusing and even misleading,” he noted. “So Ki67 is the best way to look for proliferation when it comes to myeloma.”

Other methods include the plasma cell labeling index (PCLI), gene expression profiling, flow cytometry, and multiplex immunohistochemistry (mIHC).

Dr Ely, as a hematopathologist, has found IHC to be the best method to determine proliferation, most likely because the other methods use bone marrow aspirate and IHC uses core biopsy of histologic sections.

It’s the gold standard, he said, for determining the percentage of plasma cells because core biopsy takes a “complete, intact piece of marrow that’s truly representative of what’s going on in the patient.”

In a study of more than 350 bone marrow samples comparing core biopsy with aspirate smears, plasma cells were under-represented in approximately half the aspirate specimens by about 20%.

In addition, Dr Ely noted that myeloma cells die very quickly once they are removed from the stroma.

“So if you take myeloma cells out as an aspirate,” he said, “myeloma cells die and others survive.”

And if the aspirate is sent overnight to the lab, the number of plasma cells in the specimen will already be reduced when the lab gets it.

Aspirates are best for leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes, Dr Ely said, while core biopsies are best for lymphoma and myeloma.

Plasma cell proliferation indices

Proliferation is a myeloma-defining criterion, Dr Ely said. It predicts an 80% probability of progression in 2 years.

And PCLI has shown conclusively that plasma cell proliferation is a good prognosticator in all types of myeloma patients. However, it is not really feasible to use or easy to perform.

On the other hand, core biopsy combined with IHC is a feasible way of measuring plasma cell proliferation for routine clinical use.

Using standard IHC, it’s difficult to distinguish proliferating from non-proliferating cells, Dr Ely said.

“The solution to this problem is multiplex IHC,” he said, using 3 stains—red for CD138 (the plasma cell marker), brown for Ki67 (the proliferation marker), and blue as a negative nuclear counter stain.

A red membrane around the stained cell indicates a myeloma cell. Non-proliferating MM cells have blue nuclei, and proliferating MM cells have brown nuclei.

This assay is called the plasma cell proliferation index (PCPI).

“[A]ny lab that can do standard IHC can do multiplex IHC,” Dr Ely added.

It uses the same machines, the same reagents, the same expertise, and it’s easy to set up.

Validation studies

Dr Ely and his colleagues performed extensive laboratory validation to make sure the new PCPI correlated with the old PCLI.

They also performed 3 clinical validation studies, the first in bone marrow transplant patients. The investigators followed the patients for 12 years and found the PCPI correlated with survival.

The investigators performed a second clinical validation in 151 newly diagnosed patients. On multivariate analysis, the team found PCPI to be an independent prognostic indicator.

Each 1% increase in PCPI was associated with a 3% increased risk of disease progression (hazard ratio=1.03, 95% CI, 1.01-1.05, P=0.02).

The third clinical validation the investigators conducted was a retrospective cohort study in which they evaluated the effect of rising PCPI at relapse in 37 patients. The team defined rising PCPI as a 5% or greater increase in plasma cells.

Nineteen patients had a rising PCPI, and 17 patients had stable or decreased PCPI.

Patients with a rising PCPI at relapse had a shorter median overall survival than patients with stable or decreased PCPI—72 months and not reached, respectively (P=0.0069).

Patients with a rising PCPI also had a shorter median progression-free survival on first post-relapse treatment compared to patients with stable or decreased PCPI—25 months and 47 months, respectively (P=0.036).

“It’s also important to note that if you’re getting high-risk by PCPI plus β2-microglobulin albumin, I’d advise that, for all high-risk patients, getting the cytogenetics doesn’t really help,” Dr Ely said

Three patients considered high-risk by cytogenetics were standard-risk by PCPI plus β2 microglobulin.

“So we found that cytogenetics isn’t really adding anything except the cost,” Dr Ely asserted.

Other labs are now using PCPI for prognostication, he noted, adding, “We hope PCPI will be incorporated into the International Myeloma Working Group diagnosis of MM.” ![]()

NEW YORK—As the number of therapeutic options for multiple myeloma (MM) increases, so too does the need to reassess prognostic markers for the disease, according to a speaker at Lymphoma & Myeloma 2016.

“A good prognosticator for one patient may have little meaning for another patient,” said Scott Ely, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, New York.

“It’s really important before doing any testing to ask, ‘Will the result of this test affect patient care?’”

To answer this question, Dr Ely reviewed the different testing methods used in MM patients and explained the advantages of each.

“[I]t’s really important to understand that a lot of methods are really great for research but don’t work or are not feasible for real-life diagnostic purposes,” he added.

Dr Ely also said it’s important to consider who wants the data, how much the test costs, and who will pay for it, keeping in mind that, these days, the patient’s share of the bill is increasing.

Dr Ely stressed that, until more precise targets or a better understanding of drug mechanisms exist, clinical features—patient age, performance status or frailty, renal function, and disease stage—remain the most important prognosticators.

“But still, 2 patients in the same box based on clinical features will often have very different outcomes,” he said. “So in addition to clinical factors, we need prognosticators for tumor cell behavior. We need to know how fast they are growing and how they will respond to treatment.”

Methods to assess myeloma cell proliferation

Cytogenetics (FISH), gene array technology, and genomics using next-generation sequencing can provide some information, but they are not necessarily good methods to assess proliferation, Dr Ely explained.

To determine the proliferation rate of a patient’s cancer, you can look at tens of thousands of genes by gene array, he said, “or you can just look at one thing, which is Ki67.”

If the cell has Ki67, it’s proliferating, and if it doesn’t have Ki67, it’s not.

“Often, looking at all the other upstream molecules can be confusing and even misleading,” he noted. “So Ki67 is the best way to look for proliferation when it comes to myeloma.”

Other methods include the plasma cell labeling index (PCLI), gene expression profiling, flow cytometry, and multiplex immunohistochemistry (mIHC).

Dr Ely, as a hematopathologist, has found IHC to be the best method to determine proliferation, most likely because the other methods use bone marrow aspirate and IHC uses core biopsy of histologic sections.

It’s the gold standard, he said, for determining the percentage of plasma cells because core biopsy takes a “complete, intact piece of marrow that’s truly representative of what’s going on in the patient.”

In a study of more than 350 bone marrow samples comparing core biopsy with aspirate smears, plasma cells were under-represented in approximately half the aspirate specimens by about 20%.

In addition, Dr Ely noted that myeloma cells die very quickly once they are removed from the stroma.

“So if you take myeloma cells out as an aspirate,” he said, “myeloma cells die and others survive.”

And if the aspirate is sent overnight to the lab, the number of plasma cells in the specimen will already be reduced when the lab gets it.

Aspirates are best for leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes, Dr Ely said, while core biopsies are best for lymphoma and myeloma.

Plasma cell proliferation indices

Proliferation is a myeloma-defining criterion, Dr Ely said. It predicts an 80% probability of progression in 2 years.

And PCLI has shown conclusively that plasma cell proliferation is a good prognosticator in all types of myeloma patients. However, it is not really feasible to use or easy to perform.

On the other hand, core biopsy combined with IHC is a feasible way of measuring plasma cell proliferation for routine clinical use.

Using standard IHC, it’s difficult to distinguish proliferating from non-proliferating cells, Dr Ely said.

“The solution to this problem is multiplex IHC,” he said, using 3 stains—red for CD138 (the plasma cell marker), brown for Ki67 (the proliferation marker), and blue as a negative nuclear counter stain.

A red membrane around the stained cell indicates a myeloma cell. Non-proliferating MM cells have blue nuclei, and proliferating MM cells have brown nuclei.

This assay is called the plasma cell proliferation index (PCPI).

“[A]ny lab that can do standard IHC can do multiplex IHC,” Dr Ely added.

It uses the same machines, the same reagents, the same expertise, and it’s easy to set up.

Validation studies

Dr Ely and his colleagues performed extensive laboratory validation to make sure the new PCPI correlated with the old PCLI.

They also performed 3 clinical validation studies, the first in bone marrow transplant patients. The investigators followed the patients for 12 years and found the PCPI correlated with survival.

The investigators performed a second clinical validation in 151 newly diagnosed patients. On multivariate analysis, the team found PCPI to be an independent prognostic indicator.

Each 1% increase in PCPI was associated with a 3% increased risk of disease progression (hazard ratio=1.03, 95% CI, 1.01-1.05, P=0.02).

The third clinical validation the investigators conducted was a retrospective cohort study in which they evaluated the effect of rising PCPI at relapse in 37 patients. The team defined rising PCPI as a 5% or greater increase in plasma cells.

Nineteen patients had a rising PCPI, and 17 patients had stable or decreased PCPI.

Patients with a rising PCPI at relapse had a shorter median overall survival than patients with stable or decreased PCPI—72 months and not reached, respectively (P=0.0069).

Patients with a rising PCPI also had a shorter median progression-free survival on first post-relapse treatment compared to patients with stable or decreased PCPI—25 months and 47 months, respectively (P=0.036).

“It’s also important to note that if you’re getting high-risk by PCPI plus β2-microglobulin albumin, I’d advise that, for all high-risk patients, getting the cytogenetics doesn’t really help,” Dr Ely said

Three patients considered high-risk by cytogenetics were standard-risk by PCPI plus β2 microglobulin.

“So we found that cytogenetics isn’t really adding anything except the cost,” Dr Ely asserted.

Other labs are now using PCPI for prognostication, he noted, adding, “We hope PCPI will be incorporated into the International Myeloma Working Group diagnosis of MM.” ![]()

Genetic screening for CLL premature, speaker says

Photo courtesy of the

National Institute

of General Medical Science

NEW YORK—Research has shown that family history is a strong risk factor for developing chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

First-degree relatives have an 8.5-fold risk of getting CLL and an increased risk of other lymphoproliferative disorders, according to a study published in 2009.

However, despite the strong evidence of a genetic contribution, one expert believes it’s premature to bring genetic testing into the clinic for screening in CLL.

“At this time, we do not recommend genetic screening,” said Susan Slager, PhD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

“There’s no known relationship between the inherited variants and treatment response,” she explained, and the relatively low incidence of CLL argues against active screening in affected families at present.

Dr Slager discussed genetic and non-genetic factors associated with CLL and the clinical implications of these factors at Lymphoma & Myeloma 2016.

Demographic risk factors

Dr Slager noted that age, gender, and race are risk factors for CLL.

Individuals aged 65 to 74 have the highest incidence of CLL, at 28%, while the risk is almost non-existent for those under age 20, she said.

There is a higher incidence of CLL in males than in females, and the reason for this gender disparity is unknown.

There is a higher incidence of CLL in Caucasians than Asians, for both males and females.

“Again, it’s unknown why there’s this variability in incidence in CLL,” Dr Slager said. “Obviously, age, sex, and race—these are things you can’t modify. You’re stuck with them.”

However, several studies have been undertaken to look at some of the potentially modifiable factors associated with CLL.

Beyond demographic factors

The International Lymphoma Epidemiology Consortium, known as InterLymph, was initiated in 2001 to evaluate the association of risk factors in CLL. Study centers are located primarily in North America and Europe, with one in Australia.

In one of the larger InterLymph studies, investigators evaluated risk factors—lifestyle exposure, reproductive history, medical history, occupational exposures, farming exposure, and family history—in 2440 CLL patients and 15,186 controls.

The investigators found that sun exposure and atopy—allergies, asthma, eczema, and hay fever—have a protective effect in CLL, while serological hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections, farming exposure, and family history carry an increased risk of CLL.

This confirmed an earlier study conducted in New South Wales, Australia, that had uncovered an inverse association between sun exposure and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) risk, which fell significantly with increasing recreational sun exposure.

Medical history

Another earlier study from New South Wales revealed a 20% reduction in the risk of NHL for any specific allergy.

However, the investigators of the large, more recent study observed little to no evidence of reduced risk for asthma and eczema.

The underlying biology for atopy or allergies is a hyper-immune system, Dr Slager explained.

“So if you have a hyper-immune system, then we hypothesize that you have protection against CLL,” she said.

Another medical exposure investigators analyzed that impacts CLL risk is HCV. People infected with HCV have an increased risk of CLL, perhaps due to chronic antigen stimulation or possibly disruption of the T-cell function.

Height is also associated with CLL. CLL risk increases with greater height. The concept is that taller individuals have increased exposure to growth hormones that possibly result in cell proliferation.

Another hypothesis supporting the height association is that people of shorter stature experience more infections, which could result in a stronger immune system. And a stronger immune system perhaps protects against NHL.

Occupational exposures

Investigators consistently observed a 20% increased risk of CLL for people living or working on a farm.

Animal farmers, as opposed to crop farmers, experienced some protection. However, the sample size was too small to be conclusive, with only 29 people across all studies being animal farmers.

Among other occupations evaluated, hairdressers also had an increased risk of CLL, although this too was based on a small sample size.

Family history

One of the strongest risk factors for CLL is family history.

Using population-based registry data from Sweden, investigators found that people with a first-degree relative with CLL have an 8.5-fold risk of CLL.

They also have an elevated risk of other lymphoproliferative disorders, including NHL (1.9-fold risk), Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia (4.0-fold risk), hairy cell leukemia (3.3-fold risk), and follicular lymphoma (1.6-fold risk).

GWAS in CLL

Investigators conducted genome-wide association studies (GWAS) to determine what is driving the familial risk.

Dr Slager described these studies as an agnostic approach that looks across the entire genome to determine which regions are associated with a trait of interest.

Typically, many markers are genotyped—somewhere between half a million to 5 million markers—and each is looked at individually with respect to CLL, she said.

Unrelated cases and controls are included in the studies.

The first GWAS study identifying susceptibility loci for CLL was published in 2008. Subsequently, more studies were published with increasing sample sizes—more cases, more controls, and more genetic variants identified.

In the largest meta-analysis for CLL to date (Slager and Houlston et al, not yet published), investigators analyzed 4400 CLL cases and 13,000 controls.

They identified 9 more inherited variances with CLL, for a total of 43 identified to date.

The genes involved follow an apoptosis pathway, the telomere length pathway, and the B-cell lymphocyte development pathway.

“We have to remember, though, that these are non-causal,” Dr Slager cautioned. “We are just identifying the region in the genome that’s associated with CLL . . . . So now we have to dig deeper in these relationships to understand what’s going on.”

Using the identified CLL single-nucleotide polymorphisms, the investigators computed a polygenic risk score. CLL cases in the highest quintile had 2.7-fold increased risk of CLL.

However, the most common GWAS variants explain only 17% of the genetic heritability of CLL, which suggests that more loci are yet to be identified, Dr Slager clarified.

She went on to say that CLL incidence varies by ethnicity. Caucasians have a very high rate of CLL, while Asians have a very low rate. And African Americans have an incidence rate between those of Caucasians and Asians.

Investigators have hypothesized that the differences in incidence are based on the distinct genetic variants that are associated with the ethnicities.

For example, 4 of the variants with more than 20% frequency in Caucasians are quite rare in Chinese individuals and are also quite uncommon in African Americans, with frequencies less than 10%.

Dr Slager suggested that conducting these kinds of studies in Asians and African Americans will take a large sample size and most likely require an international consortium to bring enough CLL cases together.

Impact on clinical practice

Because of the strong genetic risk, patients with CLL naturally want to know about their offspring and their siblings, Dr Slager has found.

Patients who have monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis (MBL), which is a precursor to CLL, pose the biggest quandary.

MBL is detected in about 5% of people over age 40. However, it’s detected in about 15% to 18% of people with a first-degree relative with CLL.

“These are individuals who have lymphocytosis,” Dr Slager said. “They come to your clinic and have an elevated blood cell count, flow cytometry. [So] you screen them for MBL, and these individuals who have more than 500 cells per microliter, they are the ones who progress to CLL, at 1% per year.”

Individuals who don’t have the elevated blood counts do have the clonal cells, Dr Slager noted.

“They just don’t have the expansion,” she said. “The progression of these individuals to CLL is still yet to be determined.”

For these reasons, Dr Slager believes “it’s still premature to bring genetic testing into clinical practice.”

Future directions include bringing together the non-environmental issues and the inherited issues to create a model that will accurately predict the risk of CLL. ![]()

Photo courtesy of the

National Institute

of General Medical Science

NEW YORK—Research has shown that family history is a strong risk factor for developing chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

First-degree relatives have an 8.5-fold risk of getting CLL and an increased risk of other lymphoproliferative disorders, according to a study published in 2009.

However, despite the strong evidence of a genetic contribution, one expert believes it’s premature to bring genetic testing into the clinic for screening in CLL.

“At this time, we do not recommend genetic screening,” said Susan Slager, PhD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

“There’s no known relationship between the inherited variants and treatment response,” she explained, and the relatively low incidence of CLL argues against active screening in affected families at present.

Dr Slager discussed genetic and non-genetic factors associated with CLL and the clinical implications of these factors at Lymphoma & Myeloma 2016.

Demographic risk factors

Dr Slager noted that age, gender, and race are risk factors for CLL.

Individuals aged 65 to 74 have the highest incidence of CLL, at 28%, while the risk is almost non-existent for those under age 20, she said.

There is a higher incidence of CLL in males than in females, and the reason for this gender disparity is unknown.

There is a higher incidence of CLL in Caucasians than Asians, for both males and females.

“Again, it’s unknown why there’s this variability in incidence in CLL,” Dr Slager said. “Obviously, age, sex, and race—these are things you can’t modify. You’re stuck with them.”

However, several studies have been undertaken to look at some of the potentially modifiable factors associated with CLL.

Beyond demographic factors

The International Lymphoma Epidemiology Consortium, known as InterLymph, was initiated in 2001 to evaluate the association of risk factors in CLL. Study centers are located primarily in North America and Europe, with one in Australia.

In one of the larger InterLymph studies, investigators evaluated risk factors—lifestyle exposure, reproductive history, medical history, occupational exposures, farming exposure, and family history—in 2440 CLL patients and 15,186 controls.

The investigators found that sun exposure and atopy—allergies, asthma, eczema, and hay fever—have a protective effect in CLL, while serological hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections, farming exposure, and family history carry an increased risk of CLL.

This confirmed an earlier study conducted in New South Wales, Australia, that had uncovered an inverse association between sun exposure and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) risk, which fell significantly with increasing recreational sun exposure.

Medical history

Another earlier study from New South Wales revealed a 20% reduction in the risk of NHL for any specific allergy.

However, the investigators of the large, more recent study observed little to no evidence of reduced risk for asthma and eczema.

The underlying biology for atopy or allergies is a hyper-immune system, Dr Slager explained.

“So if you have a hyper-immune system, then we hypothesize that you have protection against CLL,” she said.

Another medical exposure investigators analyzed that impacts CLL risk is HCV. People infected with HCV have an increased risk of CLL, perhaps due to chronic antigen stimulation or possibly disruption of the T-cell function.

Height is also associated with CLL. CLL risk increases with greater height. The concept is that taller individuals have increased exposure to growth hormones that possibly result in cell proliferation.

Another hypothesis supporting the height association is that people of shorter stature experience more infections, which could result in a stronger immune system. And a stronger immune system perhaps protects against NHL.

Occupational exposures

Investigators consistently observed a 20% increased risk of CLL for people living or working on a farm.

Animal farmers, as opposed to crop farmers, experienced some protection. However, the sample size was too small to be conclusive, with only 29 people across all studies being animal farmers.

Among other occupations evaluated, hairdressers also had an increased risk of CLL, although this too was based on a small sample size.

Family history

One of the strongest risk factors for CLL is family history.

Using population-based registry data from Sweden, investigators found that people with a first-degree relative with CLL have an 8.5-fold risk of CLL.

They also have an elevated risk of other lymphoproliferative disorders, including NHL (1.9-fold risk), Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia (4.0-fold risk), hairy cell leukemia (3.3-fold risk), and follicular lymphoma (1.6-fold risk).

GWAS in CLL

Investigators conducted genome-wide association studies (GWAS) to determine what is driving the familial risk.

Dr Slager described these studies as an agnostic approach that looks across the entire genome to determine which regions are associated with a trait of interest.

Typically, many markers are genotyped—somewhere between half a million to 5 million markers—and each is looked at individually with respect to CLL, she said.

Unrelated cases and controls are included in the studies.

The first GWAS study identifying susceptibility loci for CLL was published in 2008. Subsequently, more studies were published with increasing sample sizes—more cases, more controls, and more genetic variants identified.

In the largest meta-analysis for CLL to date (Slager and Houlston et al, not yet published), investigators analyzed 4400 CLL cases and 13,000 controls.

They identified 9 more inherited variances with CLL, for a total of 43 identified to date.

The genes involved follow an apoptosis pathway, the telomere length pathway, and the B-cell lymphocyte development pathway.

“We have to remember, though, that these are non-causal,” Dr Slager cautioned. “We are just identifying the region in the genome that’s associated with CLL . . . . So now we have to dig deeper in these relationships to understand what’s going on.”

Using the identified CLL single-nucleotide polymorphisms, the investigators computed a polygenic risk score. CLL cases in the highest quintile had 2.7-fold increased risk of CLL.

However, the most common GWAS variants explain only 17% of the genetic heritability of CLL, which suggests that more loci are yet to be identified, Dr Slager clarified.

She went on to say that CLL incidence varies by ethnicity. Caucasians have a very high rate of CLL, while Asians have a very low rate. And African Americans have an incidence rate between those of Caucasians and Asians.

Investigators have hypothesized that the differences in incidence are based on the distinct genetic variants that are associated with the ethnicities.

For example, 4 of the variants with more than 20% frequency in Caucasians are quite rare in Chinese individuals and are also quite uncommon in African Americans, with frequencies less than 10%.

Dr Slager suggested that conducting these kinds of studies in Asians and African Americans will take a large sample size and most likely require an international consortium to bring enough CLL cases together.

Impact on clinical practice

Because of the strong genetic risk, patients with CLL naturally want to know about their offspring and their siblings, Dr Slager has found.

Patients who have monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis (MBL), which is a precursor to CLL, pose the biggest quandary.

MBL is detected in about 5% of people over age 40. However, it’s detected in about 15% to 18% of people with a first-degree relative with CLL.

“These are individuals who have lymphocytosis,” Dr Slager said. “They come to your clinic and have an elevated blood cell count, flow cytometry. [So] you screen them for MBL, and these individuals who have more than 500 cells per microliter, they are the ones who progress to CLL, at 1% per year.”

Individuals who don’t have the elevated blood counts do have the clonal cells, Dr Slager noted.

“They just don’t have the expansion,” she said. “The progression of these individuals to CLL is still yet to be determined.”

For these reasons, Dr Slager believes “it’s still premature to bring genetic testing into clinical practice.”

Future directions include bringing together the non-environmental issues and the inherited issues to create a model that will accurately predict the risk of CLL. ![]()

Photo courtesy of the

National Institute

of General Medical Science

NEW YORK—Research has shown that family history is a strong risk factor for developing chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

First-degree relatives have an 8.5-fold risk of getting CLL and an increased risk of other lymphoproliferative disorders, according to a study published in 2009.

However, despite the strong evidence of a genetic contribution, one expert believes it’s premature to bring genetic testing into the clinic for screening in CLL.

“At this time, we do not recommend genetic screening,” said Susan Slager, PhD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

“There’s no known relationship between the inherited variants and treatment response,” she explained, and the relatively low incidence of CLL argues against active screening in affected families at present.

Dr Slager discussed genetic and non-genetic factors associated with CLL and the clinical implications of these factors at Lymphoma & Myeloma 2016.

Demographic risk factors

Dr Slager noted that age, gender, and race are risk factors for CLL.

Individuals aged 65 to 74 have the highest incidence of CLL, at 28%, while the risk is almost non-existent for those under age 20, she said.

There is a higher incidence of CLL in males than in females, and the reason for this gender disparity is unknown.

There is a higher incidence of CLL in Caucasians than Asians, for both males and females.

“Again, it’s unknown why there’s this variability in incidence in CLL,” Dr Slager said. “Obviously, age, sex, and race—these are things you can’t modify. You’re stuck with them.”

However, several studies have been undertaken to look at some of the potentially modifiable factors associated with CLL.

Beyond demographic factors

The International Lymphoma Epidemiology Consortium, known as InterLymph, was initiated in 2001 to evaluate the association of risk factors in CLL. Study centers are located primarily in North America and Europe, with one in Australia.

In one of the larger InterLymph studies, investigators evaluated risk factors—lifestyle exposure, reproductive history, medical history, occupational exposures, farming exposure, and family history—in 2440 CLL patients and 15,186 controls.

The investigators found that sun exposure and atopy—allergies, asthma, eczema, and hay fever—have a protective effect in CLL, while serological hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections, farming exposure, and family history carry an increased risk of CLL.

This confirmed an earlier study conducted in New South Wales, Australia, that had uncovered an inverse association between sun exposure and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) risk, which fell significantly with increasing recreational sun exposure.

Medical history

Another earlier study from New South Wales revealed a 20% reduction in the risk of NHL for any specific allergy.

However, the investigators of the large, more recent study observed little to no evidence of reduced risk for asthma and eczema.

The underlying biology for atopy or allergies is a hyper-immune system, Dr Slager explained.

“So if you have a hyper-immune system, then we hypothesize that you have protection against CLL,” she said.

Another medical exposure investigators analyzed that impacts CLL risk is HCV. People infected with HCV have an increased risk of CLL, perhaps due to chronic antigen stimulation or possibly disruption of the T-cell function.

Height is also associated with CLL. CLL risk increases with greater height. The concept is that taller individuals have increased exposure to growth hormones that possibly result in cell proliferation.

Another hypothesis supporting the height association is that people of shorter stature experience more infections, which could result in a stronger immune system. And a stronger immune system perhaps protects against NHL.

Occupational exposures

Investigators consistently observed a 20% increased risk of CLL for people living or working on a farm.

Animal farmers, as opposed to crop farmers, experienced some protection. However, the sample size was too small to be conclusive, with only 29 people across all studies being animal farmers.

Among other occupations evaluated, hairdressers also had an increased risk of CLL, although this too was based on a small sample size.

Family history

One of the strongest risk factors for CLL is family history.

Using population-based registry data from Sweden, investigators found that people with a first-degree relative with CLL have an 8.5-fold risk of CLL.

They also have an elevated risk of other lymphoproliferative disorders, including NHL (1.9-fold risk), Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia (4.0-fold risk), hairy cell leukemia (3.3-fold risk), and follicular lymphoma (1.6-fold risk).

GWAS in CLL

Investigators conducted genome-wide association studies (GWAS) to determine what is driving the familial risk.

Dr Slager described these studies as an agnostic approach that looks across the entire genome to determine which regions are associated with a trait of interest.

Typically, many markers are genotyped—somewhere between half a million to 5 million markers—and each is looked at individually with respect to CLL, she said.

Unrelated cases and controls are included in the studies.