User login

Tylenol Cold Products and Children's Benadryl, Motrin Recalled

The Food and Drug Administration has announced recalls of three types of over-the-counter medications since Nov. 15, all made by McNeil Consumer Healthcare.

Consumers may continue to take previously purchased products, and no action is required by healthcare providers.

Three Tylenol Cold Multi-Symptom liquid products sold in the United States (Daytime 8-ounce Citrus Burst liquid, Severe 8-ounce Cool Burst Liquid, and Nighttime 8-ounce Cool Burst Liquid) were recalled Nov. 24. No adverse events were reported, but the product labeling needs to be updated to more prominently note the small (less than 1%) presence of alcohol from flavoring agents as an inactive ingredient. This ingredient had been listed on the package but not on the front of the medicine bottle. Tylenol’s maker, McNeil Consumer Healthcare, began the recall after an internal company review identified this issue. The FDA says that healthcare providers do not need to take any action as a result of the recall, and consumers may continue to use the medicine.

McNeil also issued a voluntary recall of all product lots of Children’s Benadryl Allergy Fastmelt Tablet in cherry and grape flavors that were sold in the United States, Belize, Barbados, Canada, Puerto Rico, St. Martin and St. Thomas, as well as all Junior Strength Motrin Caplets 24 count that were sold in the United States. These recalls, issued Nov. 15, are the result of a review that found insufficiencies in the development of the manufacturing process. Consumers may continue to use these products, and no action is required for healthcare providers, according to the FDA. There is no reason to believe that the products are unsafe, and no adverse events have been reported.

Questions about the recalls should be directed to the company’s Consumer Care Center at 1-888-222-6036.

The Food and Drug Administration has announced recalls of three types of over-the-counter medications since Nov. 15, all made by McNeil Consumer Healthcare.

Consumers may continue to take previously purchased products, and no action is required by healthcare providers.

Three Tylenol Cold Multi-Symptom liquid products sold in the United States (Daytime 8-ounce Citrus Burst liquid, Severe 8-ounce Cool Burst Liquid, and Nighttime 8-ounce Cool Burst Liquid) were recalled Nov. 24. No adverse events were reported, but the product labeling needs to be updated to more prominently note the small (less than 1%) presence of alcohol from flavoring agents as an inactive ingredient. This ingredient had been listed on the package but not on the front of the medicine bottle. Tylenol’s maker, McNeil Consumer Healthcare, began the recall after an internal company review identified this issue. The FDA says that healthcare providers do not need to take any action as a result of the recall, and consumers may continue to use the medicine.

McNeil also issued a voluntary recall of all product lots of Children’s Benadryl Allergy Fastmelt Tablet in cherry and grape flavors that were sold in the United States, Belize, Barbados, Canada, Puerto Rico, St. Martin and St. Thomas, as well as all Junior Strength Motrin Caplets 24 count that were sold in the United States. These recalls, issued Nov. 15, are the result of a review that found insufficiencies in the development of the manufacturing process. Consumers may continue to use these products, and no action is required for healthcare providers, according to the FDA. There is no reason to believe that the products are unsafe, and no adverse events have been reported.

Questions about the recalls should be directed to the company’s Consumer Care Center at 1-888-222-6036.

The Food and Drug Administration has announced recalls of three types of over-the-counter medications since Nov. 15, all made by McNeil Consumer Healthcare.

Consumers may continue to take previously purchased products, and no action is required by healthcare providers.

Three Tylenol Cold Multi-Symptom liquid products sold in the United States (Daytime 8-ounce Citrus Burst liquid, Severe 8-ounce Cool Burst Liquid, and Nighttime 8-ounce Cool Burst Liquid) were recalled Nov. 24. No adverse events were reported, but the product labeling needs to be updated to more prominently note the small (less than 1%) presence of alcohol from flavoring agents as an inactive ingredient. This ingredient had been listed on the package but not on the front of the medicine bottle. Tylenol’s maker, McNeil Consumer Healthcare, began the recall after an internal company review identified this issue. The FDA says that healthcare providers do not need to take any action as a result of the recall, and consumers may continue to use the medicine.

McNeil also issued a voluntary recall of all product lots of Children’s Benadryl Allergy Fastmelt Tablet in cherry and grape flavors that were sold in the United States, Belize, Barbados, Canada, Puerto Rico, St. Martin and St. Thomas, as well as all Junior Strength Motrin Caplets 24 count that were sold in the United States. These recalls, issued Nov. 15, are the result of a review that found insufficiencies in the development of the manufacturing process. Consumers may continue to use these products, and no action is required for healthcare providers, according to the FDA. There is no reason to believe that the products are unsafe, and no adverse events have been reported.

Questions about the recalls should be directed to the company’s Consumer Care Center at 1-888-222-6036.

Mandatory Flu Shots Urged for Health Workers

All health care workers should be vaccinated annually against influenza, and doing so should be a condition of new or continued employment, according to a position paper from the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America.

This is the first time the organization has recommended mandatory vaccination of all health care workers; and its position was also endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

“I am very hopeful that this guideline will encourage the adoption of more mandatory policies at all health care institutions,” said Dr. Neil Fishman, president of SHEA and director of health care epidemiology and infection control for the University of Pennsylvania Health System, Philadelphia.

A variety of vaccinations already are required at health care facilities, including measles, mumps and rubella, and some facilities also require vaccination against chickenpox, pertussis, and hepatitis B. “So there are precedents for having vaccines as a condition of employment,” Dr. Fishman said.

The hope is that SHEA's new recommendation – published Aug. 31 in the journal Infection Control and Healthcare Epidemiology – will improve the current influenza vaccination rates for health care workers, which now hover in the 30%-40% range, Dr. Fishman said. The recommendation applies to all workers, students, and volunteers in all health care facilities, regardless of whether they have direct patient contact.

Under the SHEA position paper, the only exceptions to the mandatory vaccination policy would be for medical reasons, such as a severe allergy to eggs, Dr. Fishman said.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommends that all health care professionals get an annual influenza vaccine and that health care facilities provide the vaccine to its workers with a goal of vaccinating 100% of staff.

Researchers at the Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle – believed to be the first in the country to institute mandatory influenza vaccination for its health care workers in 2005 – recently studied their institution's efforts to improve influenza vaccination rates.

They found that in the first year after the mandatory influenza requirement was put in place, 97.6% of the facility's 4,703 health care workers were vaccinated, followed by adherence rates of more than 98% in the following 4 years. Less than 0.7% of the center's workers were exempted from vaccination for medical or religious reasons, and less than 0.2% refused to be vaccinated or left employment at the center (Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2010;31:881–8).

Dr. Fishman reported no conflicts of interest. The authors of SHEA's position paper reported having served as consultants for or having received honoraria from various companies that make vaccines, influenza diagnostics, and pharmaceuticals.

All health care workers should be vaccinated annually against influenza, and doing so should be a condition of new or continued employment, according to a position paper from the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America.

This is the first time the organization has recommended mandatory vaccination of all health care workers; and its position was also endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

“I am very hopeful that this guideline will encourage the adoption of more mandatory policies at all health care institutions,” said Dr. Neil Fishman, president of SHEA and director of health care epidemiology and infection control for the University of Pennsylvania Health System, Philadelphia.

A variety of vaccinations already are required at health care facilities, including measles, mumps and rubella, and some facilities also require vaccination against chickenpox, pertussis, and hepatitis B. “So there are precedents for having vaccines as a condition of employment,” Dr. Fishman said.

The hope is that SHEA's new recommendation – published Aug. 31 in the journal Infection Control and Healthcare Epidemiology – will improve the current influenza vaccination rates for health care workers, which now hover in the 30%-40% range, Dr. Fishman said. The recommendation applies to all workers, students, and volunteers in all health care facilities, regardless of whether they have direct patient contact.

Under the SHEA position paper, the only exceptions to the mandatory vaccination policy would be for medical reasons, such as a severe allergy to eggs, Dr. Fishman said.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommends that all health care professionals get an annual influenza vaccine and that health care facilities provide the vaccine to its workers with a goal of vaccinating 100% of staff.

Researchers at the Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle – believed to be the first in the country to institute mandatory influenza vaccination for its health care workers in 2005 – recently studied their institution's efforts to improve influenza vaccination rates.

They found that in the first year after the mandatory influenza requirement was put in place, 97.6% of the facility's 4,703 health care workers were vaccinated, followed by adherence rates of more than 98% in the following 4 years. Less than 0.7% of the center's workers were exempted from vaccination for medical or religious reasons, and less than 0.2% refused to be vaccinated or left employment at the center (Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2010;31:881–8).

Dr. Fishman reported no conflicts of interest. The authors of SHEA's position paper reported having served as consultants for or having received honoraria from various companies that make vaccines, influenza diagnostics, and pharmaceuticals.

All health care workers should be vaccinated annually against influenza, and doing so should be a condition of new or continued employment, according to a position paper from the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America.

This is the first time the organization has recommended mandatory vaccination of all health care workers; and its position was also endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

“I am very hopeful that this guideline will encourage the adoption of more mandatory policies at all health care institutions,” said Dr. Neil Fishman, president of SHEA and director of health care epidemiology and infection control for the University of Pennsylvania Health System, Philadelphia.

A variety of vaccinations already are required at health care facilities, including measles, mumps and rubella, and some facilities also require vaccination against chickenpox, pertussis, and hepatitis B. “So there are precedents for having vaccines as a condition of employment,” Dr. Fishman said.

The hope is that SHEA's new recommendation – published Aug. 31 in the journal Infection Control and Healthcare Epidemiology – will improve the current influenza vaccination rates for health care workers, which now hover in the 30%-40% range, Dr. Fishman said. The recommendation applies to all workers, students, and volunteers in all health care facilities, regardless of whether they have direct patient contact.

Under the SHEA position paper, the only exceptions to the mandatory vaccination policy would be for medical reasons, such as a severe allergy to eggs, Dr. Fishman said.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommends that all health care professionals get an annual influenza vaccine and that health care facilities provide the vaccine to its workers with a goal of vaccinating 100% of staff.

Researchers at the Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle – believed to be the first in the country to institute mandatory influenza vaccination for its health care workers in 2005 – recently studied their institution's efforts to improve influenza vaccination rates.

They found that in the first year after the mandatory influenza requirement was put in place, 97.6% of the facility's 4,703 health care workers were vaccinated, followed by adherence rates of more than 98% in the following 4 years. Less than 0.7% of the center's workers were exempted from vaccination for medical or religious reasons, and less than 0.2% refused to be vaccinated or left employment at the center (Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2010;31:881–8).

Dr. Fishman reported no conflicts of interest. The authors of SHEA's position paper reported having served as consultants for or having received honoraria from various companies that make vaccines, influenza diagnostics, and pharmaceuticals.

CDC: Adult Tdap Rates Lag as Pertussis Spikes

Despite 2005 recommendations that people aged 10-64 years receive the tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine every 10 years, vaccination rates remain suboptimal, according to researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2008, just 5.9% of adults aged 18-64 years were estimated to have received the Tdap vaccine. Tdap vaccination rates were higher for health care personnel – 15.9% – than for adults who have contact with infants − 5.0%. And for adults in this age range for whom Tdap vaccination history could be determined, 36.5% were overdue for a tetanus booster shot, which the Tdap vaccine would now replace.

These findings are especially alarming given the recent spike in the number of pertussis cases across the United States, and they underscore the need for more aggressive vaccination efforts, the researchers reported.

The analysis of data from the National Health Interview Survey showed that about 62% of adults aged 18-64 years reported having been vaccinated against tetanus in the previous 10 years in 2008, and 60% reported having updated vaccinations in 1999 (MMWR 2010;59:1302-6).

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices that made the 2005 Tdap recommendations suggested that the vaccine may be used to provide protection against infection with pertussis.

It is particularly important for health care personnel and adults who have contact with infants to be vaccinated against pertussis, because they are at higher risk for transmitting the illness to susceptible groups.

While tetanus infections are rare in the United States, pertussis is considered a common illness, according to the CDC. In 2008, 13,278 cases of pertussis were reported in the United States, although that is likely to be an underestimate given that the illness typically has nonspecific symptoms and often isn't properly diagnosed. Infants less than age 6 months who are too young to have completed pertussis vaccinations themselves are at risk of contracting the infection from their adult caretakers.

To improve Tdap vaccination rates, the CDC advises health care providers to recommend the Tdap vaccination to adults aged 18-64 years whose last tetanus shot was more than 10 years ago. For health care providers and adults who have contact with infants younger than age 1 year, the interval between the last tetanus shot and a new Tdap vaccine can be as little as 2 years.

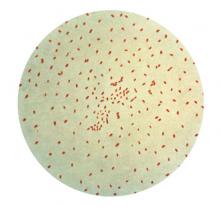

Vaccine-preventable Haemophilus pertussis infection is on the rise.

Source ©CDC

Despite 2005 recommendations that people aged 10-64 years receive the tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine every 10 years, vaccination rates remain suboptimal, according to researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2008, just 5.9% of adults aged 18-64 years were estimated to have received the Tdap vaccine. Tdap vaccination rates were higher for health care personnel – 15.9% – than for adults who have contact with infants − 5.0%. And for adults in this age range for whom Tdap vaccination history could be determined, 36.5% were overdue for a tetanus booster shot, which the Tdap vaccine would now replace.

These findings are especially alarming given the recent spike in the number of pertussis cases across the United States, and they underscore the need for more aggressive vaccination efforts, the researchers reported.

The analysis of data from the National Health Interview Survey showed that about 62% of adults aged 18-64 years reported having been vaccinated against tetanus in the previous 10 years in 2008, and 60% reported having updated vaccinations in 1999 (MMWR 2010;59:1302-6).

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices that made the 2005 Tdap recommendations suggested that the vaccine may be used to provide protection against infection with pertussis.

It is particularly important for health care personnel and adults who have contact with infants to be vaccinated against pertussis, because they are at higher risk for transmitting the illness to susceptible groups.

While tetanus infections are rare in the United States, pertussis is considered a common illness, according to the CDC. In 2008, 13,278 cases of pertussis were reported in the United States, although that is likely to be an underestimate given that the illness typically has nonspecific symptoms and often isn't properly diagnosed. Infants less than age 6 months who are too young to have completed pertussis vaccinations themselves are at risk of contracting the infection from their adult caretakers.

To improve Tdap vaccination rates, the CDC advises health care providers to recommend the Tdap vaccination to adults aged 18-64 years whose last tetanus shot was more than 10 years ago. For health care providers and adults who have contact with infants younger than age 1 year, the interval between the last tetanus shot and a new Tdap vaccine can be as little as 2 years.

Vaccine-preventable Haemophilus pertussis infection is on the rise.

Source ©CDC

Despite 2005 recommendations that people aged 10-64 years receive the tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine every 10 years, vaccination rates remain suboptimal, according to researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2008, just 5.9% of adults aged 18-64 years were estimated to have received the Tdap vaccine. Tdap vaccination rates were higher for health care personnel – 15.9% – than for adults who have contact with infants − 5.0%. And for adults in this age range for whom Tdap vaccination history could be determined, 36.5% were overdue for a tetanus booster shot, which the Tdap vaccine would now replace.

These findings are especially alarming given the recent spike in the number of pertussis cases across the United States, and they underscore the need for more aggressive vaccination efforts, the researchers reported.

The analysis of data from the National Health Interview Survey showed that about 62% of adults aged 18-64 years reported having been vaccinated against tetanus in the previous 10 years in 2008, and 60% reported having updated vaccinations in 1999 (MMWR 2010;59:1302-6).

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices that made the 2005 Tdap recommendations suggested that the vaccine may be used to provide protection against infection with pertussis.

It is particularly important for health care personnel and adults who have contact with infants to be vaccinated against pertussis, because they are at higher risk for transmitting the illness to susceptible groups.

While tetanus infections are rare in the United States, pertussis is considered a common illness, according to the CDC. In 2008, 13,278 cases of pertussis were reported in the United States, although that is likely to be an underestimate given that the illness typically has nonspecific symptoms and often isn't properly diagnosed. Infants less than age 6 months who are too young to have completed pertussis vaccinations themselves are at risk of contracting the infection from their adult caretakers.

To improve Tdap vaccination rates, the CDC advises health care providers to recommend the Tdap vaccination to adults aged 18-64 years whose last tetanus shot was more than 10 years ago. For health care providers and adults who have contact with infants younger than age 1 year, the interval between the last tetanus shot and a new Tdap vaccine can be as little as 2 years.

Vaccine-preventable Haemophilus pertussis infection is on the rise.

Source ©CDC

CDC: With Pertussis Spike, Adult Tdap Vaccination Rates Must Rise

Despite 2005 recommendations that people aged 10-64 years receive the tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine every 10 years, vaccination rates remain suboptimal, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2008, just 5.9% of adults aged 18-64 years were estimated to have received the Tdap vaccine. Tdap vaccination rates were higher for health care personnel – 15.9% – than for adults who have contact with infants – 5.0%.

And for adults in this age range for whom Tdap vaccination history could be determined, 36.5% were overdue for a tetanus booster shot, which the Tdap vaccine would now replace.

The findings are especially alarming given the recent spike in the number of pertussis cases across the United States, and they underscore the need for more aggressive vaccination efforts, according to researchers from the CDC.

The analysis of data from the National Health Interview Survey showed that about 62% of adults aged 18-64 years reported having been vaccinated against tetanus in the previous 10 years in 2008, and 60% reported having updated vaccinations in 1999 (MMWR 2010;59:1302-6).

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices that made the 2005 Tdap recommendations suggested that the vaccine may be used to provide protection against infection with pertussis.

It is particularly important for health care personnel and adults who have contact with infants to be vaccinated against pertussis, because they are at higher risk for transmitting the illness to susceptible groups.

While tetanus infections are rare in the United States, pertussis is considered a common illness, according to the CDC. In 2008, 13,278 cases of pertussis were reported in the United States, although that is likely to be an underestimate given that the illness typically has nonspecific symptoms and often isn't properly diagnosed. Infants less than age 6 months who are too young to have completed pertussis vaccinations themselves are at risk of contracting the infection from their adult caretakers.

To improve Tdap vaccination rates, the CDC advises health care providers to recommend the Tdap vaccination to adults aged 18-64 years whose last tetanus shot was more than 10 years ago. However, for health care providers and for adults who have contact with infants younger than age 1 year, the interval between the last tetanus shot and a new Tdap vaccine can be as little as 2 years.

Despite 2005 recommendations that people aged 10-64 years receive the tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine every 10 years, vaccination rates remain suboptimal, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2008, just 5.9% of adults aged 18-64 years were estimated to have received the Tdap vaccine. Tdap vaccination rates were higher for health care personnel – 15.9% – than for adults who have contact with infants – 5.0%.

And for adults in this age range for whom Tdap vaccination history could be determined, 36.5% were overdue for a tetanus booster shot, which the Tdap vaccine would now replace.

The findings are especially alarming given the recent spike in the number of pertussis cases across the United States, and they underscore the need for more aggressive vaccination efforts, according to researchers from the CDC.

The analysis of data from the National Health Interview Survey showed that about 62% of adults aged 18-64 years reported having been vaccinated against tetanus in the previous 10 years in 2008, and 60% reported having updated vaccinations in 1999 (MMWR 2010;59:1302-6).

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices that made the 2005 Tdap recommendations suggested that the vaccine may be used to provide protection against infection with pertussis.

It is particularly important for health care personnel and adults who have contact with infants to be vaccinated against pertussis, because they are at higher risk for transmitting the illness to susceptible groups.

While tetanus infections are rare in the United States, pertussis is considered a common illness, according to the CDC. In 2008, 13,278 cases of pertussis were reported in the United States, although that is likely to be an underestimate given that the illness typically has nonspecific symptoms and often isn't properly diagnosed. Infants less than age 6 months who are too young to have completed pertussis vaccinations themselves are at risk of contracting the infection from their adult caretakers.

To improve Tdap vaccination rates, the CDC advises health care providers to recommend the Tdap vaccination to adults aged 18-64 years whose last tetanus shot was more than 10 years ago. However, for health care providers and for adults who have contact with infants younger than age 1 year, the interval between the last tetanus shot and a new Tdap vaccine can be as little as 2 years.

Despite 2005 recommendations that people aged 10-64 years receive the tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine every 10 years, vaccination rates remain suboptimal, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2008, just 5.9% of adults aged 18-64 years were estimated to have received the Tdap vaccine. Tdap vaccination rates were higher for health care personnel – 15.9% – than for adults who have contact with infants – 5.0%.

And for adults in this age range for whom Tdap vaccination history could be determined, 36.5% were overdue for a tetanus booster shot, which the Tdap vaccine would now replace.

The findings are especially alarming given the recent spike in the number of pertussis cases across the United States, and they underscore the need for more aggressive vaccination efforts, according to researchers from the CDC.

The analysis of data from the National Health Interview Survey showed that about 62% of adults aged 18-64 years reported having been vaccinated against tetanus in the previous 10 years in 2008, and 60% reported having updated vaccinations in 1999 (MMWR 2010;59:1302-6).

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices that made the 2005 Tdap recommendations suggested that the vaccine may be used to provide protection against infection with pertussis.

It is particularly important for health care personnel and adults who have contact with infants to be vaccinated against pertussis, because they are at higher risk for transmitting the illness to susceptible groups.

While tetanus infections are rare in the United States, pertussis is considered a common illness, according to the CDC. In 2008, 13,278 cases of pertussis were reported in the United States, although that is likely to be an underestimate given that the illness typically has nonspecific symptoms and often isn't properly diagnosed. Infants less than age 6 months who are too young to have completed pertussis vaccinations themselves are at risk of contracting the infection from their adult caretakers.

To improve Tdap vaccination rates, the CDC advises health care providers to recommend the Tdap vaccination to adults aged 18-64 years whose last tetanus shot was more than 10 years ago. However, for health care providers and for adults who have contact with infants younger than age 1 year, the interval between the last tetanus shot and a new Tdap vaccine can be as little as 2 years.

Pradaxa Approved for Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Patients

The Food and Drug Administration approved the direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran (Pradaxa) on Oct. 19 to prevent stroke and blood clots in people with atrial fibrillation.

It is the first approval of an oral anticoagulant in more than 50 years.

About 2 million Americans have atrial fibrillation, and that condition puts them at a “higher risk of developing blood clots, which can cause a disabling stroke if the clots travel to the brain,” Dr. Norman Stockbridge, director of the division of cardiovascular and renal products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a written statement.

Dabigatran, manufactured by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc., will be distributed in 75-mg and 150-mg capsules. Dosage recommendations are based on the patient’s creatinine clearance: For patients with a creatinine clearance greater than 30 mL/min, the recommended dosage is 150 mg twice daily; for those with a level of 15-30 mL/min, the recommended dosage is 75 mg twice daily. There is no dosage recommendation for those with a creatinine clearance below 15 mL/min.

The medication does not require periodic international normalized ratio (INR) testing of patients, as is required for those taking warfarin, Dr. Stockbridge said. Patients converting from warfarin to dabigatran should discontinue warfarin and start dabigatran when their INR is below 2.0, according to the prescribing information.

The approval was based on the results of the Randomized Evaluation of Long Term Anticoagulant Therapy (RE-LY) trial, a noninferiority study of 18,113 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and at least one other risk factor for stroke. The annual rate of stroke and systemic embolism in RE-LY was 1.5% among the patients on the 110-mg dose and 1.1% among those on the 150-mg dose, compared with 1.7% among those on warfarin, representing risk reductions of 10% and 35% for the 110-mg and 150-mg doses, compared with warfarin. Both doses of dabigatran were considered noninferior to warfarin for preventing stroke and systemic embolism, and the 150-mg dose was more effective than warfarin and the 110-mg dose in preventing stroke and systemic embolism, according to the trial’s sponsor, Boehringer Ingelheim. Both doses were associated with a reduction in hemorrhagic stroke, and compared with warfarin, the higher dose was associated with a reduction in vascular death risk.

The 150-mg dose was associated with a significantly increased risk of major GI bleeding, compared with warfarin, but also with a significant reduction in life-threatening and total bleeding. In a September meeting of the FDA’s Cardiovascular and Renal Drugs Advisory Committee, the panel agreed that the study provided strong evidence that both dabigatran doses studied had clearly been shown to be noninferior to warfarin therapy in the study, and several said they believed the 150-mg dose had been shown to be superior to warfarin. That committee voted unanimously that dabigatran should be approved.

Because dabigatran carries a risk of serious bleeding, a medication guide describing this risk will be given to patients who take it. Other less serious reactions included gastrointestinal symptoms such as dyspepsia, stomach pain, nausea, heartburn, and bloating, the FDA statement said.

The Food and Drug Administration approved the direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran (Pradaxa) on Oct. 19 to prevent stroke and blood clots in people with atrial fibrillation.

It is the first approval of an oral anticoagulant in more than 50 years.

About 2 million Americans have atrial fibrillation, and that condition puts them at a “higher risk of developing blood clots, which can cause a disabling stroke if the clots travel to the brain,” Dr. Norman Stockbridge, director of the division of cardiovascular and renal products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a written statement.

Dabigatran, manufactured by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc., will be distributed in 75-mg and 150-mg capsules. Dosage recommendations are based on the patient’s creatinine clearance: For patients with a creatinine clearance greater than 30 mL/min, the recommended dosage is 150 mg twice daily; for those with a level of 15-30 mL/min, the recommended dosage is 75 mg twice daily. There is no dosage recommendation for those with a creatinine clearance below 15 mL/min.

The medication does not require periodic international normalized ratio (INR) testing of patients, as is required for those taking warfarin, Dr. Stockbridge said. Patients converting from warfarin to dabigatran should discontinue warfarin and start dabigatran when their INR is below 2.0, according to the prescribing information.

The approval was based on the results of the Randomized Evaluation of Long Term Anticoagulant Therapy (RE-LY) trial, a noninferiority study of 18,113 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and at least one other risk factor for stroke. The annual rate of stroke and systemic embolism in RE-LY was 1.5% among the patients on the 110-mg dose and 1.1% among those on the 150-mg dose, compared with 1.7% among those on warfarin, representing risk reductions of 10% and 35% for the 110-mg and 150-mg doses, compared with warfarin. Both doses of dabigatran were considered noninferior to warfarin for preventing stroke and systemic embolism, and the 150-mg dose was more effective than warfarin and the 110-mg dose in preventing stroke and systemic embolism, according to the trial’s sponsor, Boehringer Ingelheim. Both doses were associated with a reduction in hemorrhagic stroke, and compared with warfarin, the higher dose was associated with a reduction in vascular death risk.

The 150-mg dose was associated with a significantly increased risk of major GI bleeding, compared with warfarin, but also with a significant reduction in life-threatening and total bleeding. In a September meeting of the FDA’s Cardiovascular and Renal Drugs Advisory Committee, the panel agreed that the study provided strong evidence that both dabigatran doses studied had clearly been shown to be noninferior to warfarin therapy in the study, and several said they believed the 150-mg dose had been shown to be superior to warfarin. That committee voted unanimously that dabigatran should be approved.

Because dabigatran carries a risk of serious bleeding, a medication guide describing this risk will be given to patients who take it. Other less serious reactions included gastrointestinal symptoms such as dyspepsia, stomach pain, nausea, heartburn, and bloating, the FDA statement said.

The Food and Drug Administration approved the direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran (Pradaxa) on Oct. 19 to prevent stroke and blood clots in people with atrial fibrillation.

It is the first approval of an oral anticoagulant in more than 50 years.

About 2 million Americans have atrial fibrillation, and that condition puts them at a “higher risk of developing blood clots, which can cause a disabling stroke if the clots travel to the brain,” Dr. Norman Stockbridge, director of the division of cardiovascular and renal products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a written statement.

Dabigatran, manufactured by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc., will be distributed in 75-mg and 150-mg capsules. Dosage recommendations are based on the patient’s creatinine clearance: For patients with a creatinine clearance greater than 30 mL/min, the recommended dosage is 150 mg twice daily; for those with a level of 15-30 mL/min, the recommended dosage is 75 mg twice daily. There is no dosage recommendation for those with a creatinine clearance below 15 mL/min.

The medication does not require periodic international normalized ratio (INR) testing of patients, as is required for those taking warfarin, Dr. Stockbridge said. Patients converting from warfarin to dabigatran should discontinue warfarin and start dabigatran when their INR is below 2.0, according to the prescribing information.

The approval was based on the results of the Randomized Evaluation of Long Term Anticoagulant Therapy (RE-LY) trial, a noninferiority study of 18,113 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and at least one other risk factor for stroke. The annual rate of stroke and systemic embolism in RE-LY was 1.5% among the patients on the 110-mg dose and 1.1% among those on the 150-mg dose, compared with 1.7% among those on warfarin, representing risk reductions of 10% and 35% for the 110-mg and 150-mg doses, compared with warfarin. Both doses of dabigatran were considered noninferior to warfarin for preventing stroke and systemic embolism, and the 150-mg dose was more effective than warfarin and the 110-mg dose in preventing stroke and systemic embolism, according to the trial’s sponsor, Boehringer Ingelheim. Both doses were associated with a reduction in hemorrhagic stroke, and compared with warfarin, the higher dose was associated with a reduction in vascular death risk.

The 150-mg dose was associated with a significantly increased risk of major GI bleeding, compared with warfarin, but also with a significant reduction in life-threatening and total bleeding. In a September meeting of the FDA’s Cardiovascular and Renal Drugs Advisory Committee, the panel agreed that the study provided strong evidence that both dabigatran doses studied had clearly been shown to be noninferior to warfarin therapy in the study, and several said they believed the 150-mg dose had been shown to be superior to warfarin. That committee voted unanimously that dabigatran should be approved.

Because dabigatran carries a risk of serious bleeding, a medication guide describing this risk will be given to patients who take it. Other less serious reactions included gastrointestinal symptoms such as dyspepsia, stomach pain, nausea, heartburn, and bloating, the FDA statement said.

Pradaxa Approved for Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Patients

The Food and Drug Administration approved the direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran (Pradaxa) on Oct. 19 to prevent stroke and blood clots in people with atrial fibrillation.

It is the first approval of an oral anticoagulant in more than 50 years.

About 2 million Americans have atrial fibrillation, and that condition puts them at a “higher risk of developing blood clots, which can cause a disabling stroke if the clots travel to the brain,” Dr. Norman Stockbridge, director of the division of cardiovascular and renal products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a written statement.

Dabigatran, manufactured by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc., will be distributed in 75-mg and 150-mg capsules. Dosage recommendations are based on the patient’s creatinine clearance: For patients with a creatinine clearance greater than 30 mL/min, the recommended dosage is 150 mg twice daily; for those with a level of 15-30 mL/min, the recommended dosage is 75 mg twice daily. There is no dosage recommendation for those with a creatinine clearance below 15 mL/min.

The medication does not require periodic international normalized ratio (INR) testing of patients, as is required for those taking warfarin, Dr. Stockbridge said. Patients converting from warfarin to dabigatran should discontinue warfarin and start dabigatran when their INR is below 2.0, according to the prescribing information.

The approval was based on the results of the Randomized Evaluation of Long Term Anticoagulant Therapy (RE-LY) trial, a noninferiority study of 18,113 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and at least one other risk factor for stroke. The annual rate of stroke and systemic embolism in RE-LY was 1.5% among the patients on the 110-mg dose and 1.1% among those on the 150-mg dose, compared with 1.7% among those on warfarin, representing risk reductions of 10% and 35% for the 110-mg and 150-mg doses, compared with warfarin. Both doses of dabigatran were considered noninferior to warfarin for preventing stroke and systemic embolism, and the 150-mg dose was more effective than warfarin and the 110-mg dose in preventing stroke and systemic embolism, according to the trial’s sponsor, Boehringer Ingelheim. Both doses were associated with a reduction in hemorrhagic stroke, and compared with warfarin, the higher dose was associated with a reduction in vascular death risk.

The 150-mg dose was associated with a significantly increased risk of major GI bleeding, compared with warfarin, but also with a significant reduction in life-threatening and total bleeding. In a September meeting of the FDA’s Cardiovascular and Renal Drugs Advisory Committee, the panel agreed that the study provided strong evidence that both dabigatran doses studied had clearly been shown to be noninferior to warfarin therapy in the study, and several said they believed the 150-mg dose had been shown to be superior to warfarin. That committee voted unanimously that dabigatran should be approved.

Because dabigatran carries a risk of serious bleeding, a medication guide describing this risk will be given to patients who take it. Other less serious reactions included gastrointestinal symptoms such as dyspepsia, stomach pain, nausea, heartburn, and bloating, the FDA statement said.

The Food and Drug Administration approved the direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran (Pradaxa) on Oct. 19 to prevent stroke and blood clots in people with atrial fibrillation.

It is the first approval of an oral anticoagulant in more than 50 years.

About 2 million Americans have atrial fibrillation, and that condition puts them at a “higher risk of developing blood clots, which can cause a disabling stroke if the clots travel to the brain,” Dr. Norman Stockbridge, director of the division of cardiovascular and renal products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a written statement.

Dabigatran, manufactured by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc., will be distributed in 75-mg and 150-mg capsules. Dosage recommendations are based on the patient’s creatinine clearance: For patients with a creatinine clearance greater than 30 mL/min, the recommended dosage is 150 mg twice daily; for those with a level of 15-30 mL/min, the recommended dosage is 75 mg twice daily. There is no dosage recommendation for those with a creatinine clearance below 15 mL/min.

The medication does not require periodic international normalized ratio (INR) testing of patients, as is required for those taking warfarin, Dr. Stockbridge said. Patients converting from warfarin to dabigatran should discontinue warfarin and start dabigatran when their INR is below 2.0, according to the prescribing information.

The approval was based on the results of the Randomized Evaluation of Long Term Anticoagulant Therapy (RE-LY) trial, a noninferiority study of 18,113 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and at least one other risk factor for stroke. The annual rate of stroke and systemic embolism in RE-LY was 1.5% among the patients on the 110-mg dose and 1.1% among those on the 150-mg dose, compared with 1.7% among those on warfarin, representing risk reductions of 10% and 35% for the 110-mg and 150-mg doses, compared with warfarin. Both doses of dabigatran were considered noninferior to warfarin for preventing stroke and systemic embolism, and the 150-mg dose was more effective than warfarin and the 110-mg dose in preventing stroke and systemic embolism, according to the trial’s sponsor, Boehringer Ingelheim. Both doses were associated with a reduction in hemorrhagic stroke, and compared with warfarin, the higher dose was associated with a reduction in vascular death risk.

The 150-mg dose was associated with a significantly increased risk of major GI bleeding, compared with warfarin, but also with a significant reduction in life-threatening and total bleeding. In a September meeting of the FDA’s Cardiovascular and Renal Drugs Advisory Committee, the panel agreed that the study provided strong evidence that both dabigatran doses studied had clearly been shown to be noninferior to warfarin therapy in the study, and several said they believed the 150-mg dose had been shown to be superior to warfarin. That committee voted unanimously that dabigatran should be approved.

Because dabigatran carries a risk of serious bleeding, a medication guide describing this risk will be given to patients who take it. Other less serious reactions included gastrointestinal symptoms such as dyspepsia, stomach pain, nausea, heartburn, and bloating, the FDA statement said.

The Food and Drug Administration approved the direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran (Pradaxa) on Oct. 19 to prevent stroke and blood clots in people with atrial fibrillation.

It is the first approval of an oral anticoagulant in more than 50 years.

About 2 million Americans have atrial fibrillation, and that condition puts them at a “higher risk of developing blood clots, which can cause a disabling stroke if the clots travel to the brain,” Dr. Norman Stockbridge, director of the division of cardiovascular and renal products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a written statement.

Dabigatran, manufactured by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc., will be distributed in 75-mg and 150-mg capsules. Dosage recommendations are based on the patient’s creatinine clearance: For patients with a creatinine clearance greater than 30 mL/min, the recommended dosage is 150 mg twice daily; for those with a level of 15-30 mL/min, the recommended dosage is 75 mg twice daily. There is no dosage recommendation for those with a creatinine clearance below 15 mL/min.

The medication does not require periodic international normalized ratio (INR) testing of patients, as is required for those taking warfarin, Dr. Stockbridge said. Patients converting from warfarin to dabigatran should discontinue warfarin and start dabigatran when their INR is below 2.0, according to the prescribing information.

The approval was based on the results of the Randomized Evaluation of Long Term Anticoagulant Therapy (RE-LY) trial, a noninferiority study of 18,113 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and at least one other risk factor for stroke. The annual rate of stroke and systemic embolism in RE-LY was 1.5% among the patients on the 110-mg dose and 1.1% among those on the 150-mg dose, compared with 1.7% among those on warfarin, representing risk reductions of 10% and 35% for the 110-mg and 150-mg doses, compared with warfarin. Both doses of dabigatran were considered noninferior to warfarin for preventing stroke and systemic embolism, and the 150-mg dose was more effective than warfarin and the 110-mg dose in preventing stroke and systemic embolism, according to the trial’s sponsor, Boehringer Ingelheim. Both doses were associated with a reduction in hemorrhagic stroke, and compared with warfarin, the higher dose was associated with a reduction in vascular death risk.

The 150-mg dose was associated with a significantly increased risk of major GI bleeding, compared with warfarin, but also with a significant reduction in life-threatening and total bleeding. In a September meeting of the FDA’s Cardiovascular and Renal Drugs Advisory Committee, the panel agreed that the study provided strong evidence that both dabigatran doses studied had clearly been shown to be noninferior to warfarin therapy in the study, and several said they believed the 150-mg dose had been shown to be superior to warfarin. That committee voted unanimously that dabigatran should be approved.

Because dabigatran carries a risk of serious bleeding, a medication guide describing this risk will be given to patients who take it. Other less serious reactions included gastrointestinal symptoms such as dyspepsia, stomach pain, nausea, heartburn, and bloating, the FDA statement said.

CDC: Adult Tdap Vaccination Rates Need to Be Improved

Despite 2005 recommendations that people ages 10-64 years receive the tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine every 10 years, vaccination rates remain suboptimal, according to an Oct. 15 report in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

In 2008, just 5.9% of adults ages 18-64 years were estimated to have received the Tdap vaccine. Tdap vaccination rates were higher for health care personnel – 15.9% – than for adults who have contact with infants – 5.0%. And for adults in this age range for whom Tdap vaccination history could be determined, 36.5% were overdue for a tetanus booster shot, which the Tdap vaccine would now replace.

These findings are especially alarming given the recent spike in the number of pertussis cases across the United States, and they underscore the need for more aggressive vaccination efforts, according to researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The analysis of data from the National Health Interview Survey showed that about 62% of adults ages 18-64 years reported having been vaccinated against tetanus in the previous 10 years in 2008, and 60% reported having updated vaccinations in 1999 (MMWR 2010;59:1302-6).

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices that made the 2005 Tdap recommendations suggested that the vaccine may be used to provide protection against infection with pertussis.

It is particularly important for health care personnel and adults who have contact with infants to be vaccinated against pertussis, because they are at higher risk for transmitting the illness to susceptible groups.

While tetanus infections are rare in the United States, pertussis is considered a common illness, according to the CDC. In 2008, 13,278 cases of pertussis were reported in the U.S., although that is likely to be an underestimate given that the illness typically has nonspecific symptoms and often isn’t properly diagnosed. Infants less than age 6 months who are too young to have completed pertussis vaccinations themselves are at risk of contracting the infection from their adult caretakers.

To improve Tdap vaccination rates, the CDC advises health care providers to recommend the Tdap vaccination to adults ages 18-64 years whose last tetanus shot was more than 10 years ago. However, for health care providers and for adults who have contact with infants younger than age 1 year, the interval between the last tetanus shot and a new Tdap vaccine can be as little as 2 years.

Despite 2005 recommendations that people ages 10-64 years receive the tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine every 10 years, vaccination rates remain suboptimal, according to an Oct. 15 report in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

In 2008, just 5.9% of adults ages 18-64 years were estimated to have received the Tdap vaccine. Tdap vaccination rates were higher for health care personnel – 15.9% – than for adults who have contact with infants – 5.0%. And for adults in this age range for whom Tdap vaccination history could be determined, 36.5% were overdue for a tetanus booster shot, which the Tdap vaccine would now replace.

These findings are especially alarming given the recent spike in the number of pertussis cases across the United States, and they underscore the need for more aggressive vaccination efforts, according to researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The analysis of data from the National Health Interview Survey showed that about 62% of adults ages 18-64 years reported having been vaccinated against tetanus in the previous 10 years in 2008, and 60% reported having updated vaccinations in 1999 (MMWR 2010;59:1302-6).

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices that made the 2005 Tdap recommendations suggested that the vaccine may be used to provide protection against infection with pertussis.

It is particularly important for health care personnel and adults who have contact with infants to be vaccinated against pertussis, because they are at higher risk for transmitting the illness to susceptible groups.

While tetanus infections are rare in the United States, pertussis is considered a common illness, according to the CDC. In 2008, 13,278 cases of pertussis were reported in the U.S., although that is likely to be an underestimate given that the illness typically has nonspecific symptoms and often isn’t properly diagnosed. Infants less than age 6 months who are too young to have completed pertussis vaccinations themselves are at risk of contracting the infection from their adult caretakers.

To improve Tdap vaccination rates, the CDC advises health care providers to recommend the Tdap vaccination to adults ages 18-64 years whose last tetanus shot was more than 10 years ago. However, for health care providers and for adults who have contact with infants younger than age 1 year, the interval between the last tetanus shot and a new Tdap vaccine can be as little as 2 years.

Despite 2005 recommendations that people ages 10-64 years receive the tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine every 10 years, vaccination rates remain suboptimal, according to an Oct. 15 report in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

In 2008, just 5.9% of adults ages 18-64 years were estimated to have received the Tdap vaccine. Tdap vaccination rates were higher for health care personnel – 15.9% – than for adults who have contact with infants – 5.0%. And for adults in this age range for whom Tdap vaccination history could be determined, 36.5% were overdue for a tetanus booster shot, which the Tdap vaccine would now replace.

These findings are especially alarming given the recent spike in the number of pertussis cases across the United States, and they underscore the need for more aggressive vaccination efforts, according to researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The analysis of data from the National Health Interview Survey showed that about 62% of adults ages 18-64 years reported having been vaccinated against tetanus in the previous 10 years in 2008, and 60% reported having updated vaccinations in 1999 (MMWR 2010;59:1302-6).

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices that made the 2005 Tdap recommendations suggested that the vaccine may be used to provide protection against infection with pertussis.

It is particularly important for health care personnel and adults who have contact with infants to be vaccinated against pertussis, because they are at higher risk for transmitting the illness to susceptible groups.

While tetanus infections are rare in the United States, pertussis is considered a common illness, according to the CDC. In 2008, 13,278 cases of pertussis were reported in the U.S., although that is likely to be an underestimate given that the illness typically has nonspecific symptoms and often isn’t properly diagnosed. Infants less than age 6 months who are too young to have completed pertussis vaccinations themselves are at risk of contracting the infection from their adult caretakers.

To improve Tdap vaccination rates, the CDC advises health care providers to recommend the Tdap vaccination to adults ages 18-64 years whose last tetanus shot was more than 10 years ago. However, for health care providers and for adults who have contact with infants younger than age 1 year, the interval between the last tetanus shot and a new Tdap vaccine can be as little as 2 years.

FROM MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY WEEKLY REPORT

CDC: Adult Tdap Vaccination Rates Need to Be Improved

Despite 2005 recommendations that people ages 10-64 years receive the tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine every 10 years, vaccination rates remain suboptimal, according to an Oct. 15 report in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

In 2008, just 5.9% of adults ages 18-64 years were estimated to have received the Tdap vaccine. Tdap vaccination rates were higher for health care personnel – 15.9% – than for adults who have contact with infants – 5.0%. And for adults in this age range for whom Tdap vaccination history could be determined, 36.5% were overdue for a tetanus booster shot, which the Tdap vaccine would now replace.

These findings are especially alarming given the recent spike in the number of pertussis cases across the United States, and they underscore the need for more aggressive vaccination efforts, according to researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The analysis of data from the National Health Interview Survey showed that about 62% of adults ages 18-64 years reported having been vaccinated against tetanus in the previous 10 years in 2008, and 60% reported having updated vaccinations in 1999 (MMWR 2010;59:1302-6).

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices that made the 2005 Tdap recommendations suggested that the vaccine may be used to provide protection against infection with pertussis.

It is particularly important for health care personnel and adults who have contact with infants to be vaccinated against pertussis, because they are at higher risk for transmitting the illness to susceptible groups.

While tetanus infections are rare in the United States, pertussis is considered a common illness, according to the CDC. In 2008, 13,278 cases of pertussis were reported in the U.S., although that is likely to be an underestimate given that the illness typically has nonspecific symptoms and often isn’t properly diagnosed. Infants less than age 6 months who are too young to have completed pertussis vaccinations themselves are at risk of contracting the infection from their adult caretakers.

To improve Tdap vaccination rates, the CDC advises health care providers to recommend the Tdap vaccination to adults ages 18-64 years whose last tetanus shot was more than 10 years ago. However, for health care providers and for adults who have contact with infants younger than age 1 year, the interval between the last tetanus shot and a new Tdap vaccine can be as little as 2 years.

Despite 2005 recommendations that people ages 10-64 years receive the tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine every 10 years, vaccination rates remain suboptimal, according to an Oct. 15 report in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

In 2008, just 5.9% of adults ages 18-64 years were estimated to have received the Tdap vaccine. Tdap vaccination rates were higher for health care personnel – 15.9% – than for adults who have contact with infants – 5.0%. And for adults in this age range for whom Tdap vaccination history could be determined, 36.5% were overdue for a tetanus booster shot, which the Tdap vaccine would now replace.

These findings are especially alarming given the recent spike in the number of pertussis cases across the United States, and they underscore the need for more aggressive vaccination efforts, according to researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The analysis of data from the National Health Interview Survey showed that about 62% of adults ages 18-64 years reported having been vaccinated against tetanus in the previous 10 years in 2008, and 60% reported having updated vaccinations in 1999 (MMWR 2010;59:1302-6).

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices that made the 2005 Tdap recommendations suggested that the vaccine may be used to provide protection against infection with pertussis.

It is particularly important for health care personnel and adults who have contact with infants to be vaccinated against pertussis, because they are at higher risk for transmitting the illness to susceptible groups.

While tetanus infections are rare in the United States, pertussis is considered a common illness, according to the CDC. In 2008, 13,278 cases of pertussis were reported in the U.S., although that is likely to be an underestimate given that the illness typically has nonspecific symptoms and often isn’t properly diagnosed. Infants less than age 6 months who are too young to have completed pertussis vaccinations themselves are at risk of contracting the infection from their adult caretakers.

To improve Tdap vaccination rates, the CDC advises health care providers to recommend the Tdap vaccination to adults ages 18-64 years whose last tetanus shot was more than 10 years ago. However, for health care providers and for adults who have contact with infants younger than age 1 year, the interval between the last tetanus shot and a new Tdap vaccine can be as little as 2 years.

Despite 2005 recommendations that people ages 10-64 years receive the tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine every 10 years, vaccination rates remain suboptimal, according to an Oct. 15 report in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

In 2008, just 5.9% of adults ages 18-64 years were estimated to have received the Tdap vaccine. Tdap vaccination rates were higher for health care personnel – 15.9% – than for adults who have contact with infants – 5.0%. And for adults in this age range for whom Tdap vaccination history could be determined, 36.5% were overdue for a tetanus booster shot, which the Tdap vaccine would now replace.

These findings are especially alarming given the recent spike in the number of pertussis cases across the United States, and they underscore the need for more aggressive vaccination efforts, according to researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The analysis of data from the National Health Interview Survey showed that about 62% of adults ages 18-64 years reported having been vaccinated against tetanus in the previous 10 years in 2008, and 60% reported having updated vaccinations in 1999 (MMWR 2010;59:1302-6).

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices that made the 2005 Tdap recommendations suggested that the vaccine may be used to provide protection against infection with pertussis.

It is particularly important for health care personnel and adults who have contact with infants to be vaccinated against pertussis, because they are at higher risk for transmitting the illness to susceptible groups.

While tetanus infections are rare in the United States, pertussis is considered a common illness, according to the CDC. In 2008, 13,278 cases of pertussis were reported in the U.S., although that is likely to be an underestimate given that the illness typically has nonspecific symptoms and often isn’t properly diagnosed. Infants less than age 6 months who are too young to have completed pertussis vaccinations themselves are at risk of contracting the infection from their adult caretakers.

To improve Tdap vaccination rates, the CDC advises health care providers to recommend the Tdap vaccination to adults ages 18-64 years whose last tetanus shot was more than 10 years ago. However, for health care providers and for adults who have contact with infants younger than age 1 year, the interval between the last tetanus shot and a new Tdap vaccine can be as little as 2 years.

FROM MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY WEEKLY REPORT

SHEA Calls for Mandatory Flu Shots for Health Care Workers

All health care workers should be vaccinated annually against influenza, and doing so should be a condition of new or continued employment, according to a position paper from the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America.

This is the first time the organization has recommended mandatory vaccination of all health care workers; and its position was also endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

“I am very hopeful that this guideline will encourage the adoption of more mandatory policies at all health care institutions,” said Dr. Neil Fishman, president of SHEA and director of health care epidemiology and infection control for the University of Pennsylvania Health System, Philadelphia.

A variety of vaccinations already are required at health care facilities, including measles, mumps and rubella, and some facilities also require vaccination against chickenpox, pertussis, and hepatitis B. “So there are precedents for having vaccines as a condition of employment,” Dr. Fishman said.

The hope is that SHEA’s new recommendation – published Aug. 31 in the journal Infection Control and Healthcare Epidemiology – will improve the current influenza vaccination rates for health care workers, which now hover in the 30%-40% range, Dr. Fishman said. The recommendation applies to all workers, students, and volunteers in all health care facilities, regardless of whether they have direct patient contact.

Under the SHEA position paper, the only exceptions to the mandatory vaccination policy would be for medical reasons, such as a severe allergy to eggs, Dr. Fishman said.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommends that all health care professionals get an annual influenza vaccine and that health care facilities provide the vaccine to its workers with a goal of vaccinating 100% of staff.

Some health facilities and systems already require influenza vaccination as a condition of employment. The University of Pennsylvania Health System, where Dr. Fishman works, has required flu vaccination for its workers since 2009.

Researchers at the Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle – believed to be the first in the country to institute mandatory influenza vaccination for its health care workers in 2005 – recently studied their institution’s efforts to improve influenza vaccination rates.

They found that in the first year after the mandatory influenza requirement was put in place, 97.6% of the facility’s 4,703 health care workers were vaccinated, followed by adherence rates of more than 98% in the following 4 years. Less than 0.7% of the center’s workers were exempted from vaccination for medical or religious reasons, and less than 0.2% refused vaccinated or left employment at the center (Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2010;31:881-8).

“Influenza vaccination of health care providers is a professional and ethical obligation … to prevent the spread of influenza, an infection that can spread rapidly through an institution,” Dr. Fishman said.

Disclosures: Dr. Fishman reported no conflicts of interest. The authors of SHEA’s position paper reported having served as consultants for or having received honoraria from various companies that make vaccines, influenza diagnostics, and pharmaceuticals.

All health care workers should be vaccinated annually against influenza, and doing so should be a condition of new or continued employment, according to a position paper from the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America.

This is the first time the organization has recommended mandatory vaccination of all health care workers; and its position was also endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

“I am very hopeful that this guideline will encourage the adoption of more mandatory policies at all health care institutions,” said Dr. Neil Fishman, president of SHEA and director of health care epidemiology and infection control for the University of Pennsylvania Health System, Philadelphia.

A variety of vaccinations already are required at health care facilities, including measles, mumps and rubella, and some facilities also require vaccination against chickenpox, pertussis, and hepatitis B. “So there are precedents for having vaccines as a condition of employment,” Dr. Fishman said.

The hope is that SHEA’s new recommendation – published Aug. 31 in the journal Infection Control and Healthcare Epidemiology – will improve the current influenza vaccination rates for health care workers, which now hover in the 30%-40% range, Dr. Fishman said. The recommendation applies to all workers, students, and volunteers in all health care facilities, regardless of whether they have direct patient contact.

Under the SHEA position paper, the only exceptions to the mandatory vaccination policy would be for medical reasons, such as a severe allergy to eggs, Dr. Fishman said.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommends that all health care professionals get an annual influenza vaccine and that health care facilities provide the vaccine to its workers with a goal of vaccinating 100% of staff.

Some health facilities and systems already require influenza vaccination as a condition of employment. The University of Pennsylvania Health System, where Dr. Fishman works, has required flu vaccination for its workers since 2009.

Researchers at the Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle – believed to be the first in the country to institute mandatory influenza vaccination for its health care workers in 2005 – recently studied their institution’s efforts to improve influenza vaccination rates.

They found that in the first year after the mandatory influenza requirement was put in place, 97.6% of the facility’s 4,703 health care workers were vaccinated, followed by adherence rates of more than 98% in the following 4 years. Less than 0.7% of the center’s workers were exempted from vaccination for medical or religious reasons, and less than 0.2% refused vaccinated or left employment at the center (Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2010;31:881-8).

“Influenza vaccination of health care providers is a professional and ethical obligation … to prevent the spread of influenza, an infection that can spread rapidly through an institution,” Dr. Fishman said.

Disclosures: Dr. Fishman reported no conflicts of interest. The authors of SHEA’s position paper reported having served as consultants for or having received honoraria from various companies that make vaccines, influenza diagnostics, and pharmaceuticals.

All health care workers should be vaccinated annually against influenza, and doing so should be a condition of new or continued employment, according to a position paper from the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America.

This is the first time the organization has recommended mandatory vaccination of all health care workers; and its position was also endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

“I am very hopeful that this guideline will encourage the adoption of more mandatory policies at all health care institutions,” said Dr. Neil Fishman, president of SHEA and director of health care epidemiology and infection control for the University of Pennsylvania Health System, Philadelphia.

A variety of vaccinations already are required at health care facilities, including measles, mumps and rubella, and some facilities also require vaccination against chickenpox, pertussis, and hepatitis B. “So there are precedents for having vaccines as a condition of employment,” Dr. Fishman said.

The hope is that SHEA’s new recommendation – published Aug. 31 in the journal Infection Control and Healthcare Epidemiology – will improve the current influenza vaccination rates for health care workers, which now hover in the 30%-40% range, Dr. Fishman said. The recommendation applies to all workers, students, and volunteers in all health care facilities, regardless of whether they have direct patient contact.

Under the SHEA position paper, the only exceptions to the mandatory vaccination policy would be for medical reasons, such as a severe allergy to eggs, Dr. Fishman said.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommends that all health care professionals get an annual influenza vaccine and that health care facilities provide the vaccine to its workers with a goal of vaccinating 100% of staff.

Some health facilities and systems already require influenza vaccination as a condition of employment. The University of Pennsylvania Health System, where Dr. Fishman works, has required flu vaccination for its workers since 2009.

Researchers at the Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle – believed to be the first in the country to institute mandatory influenza vaccination for its health care workers in 2005 – recently studied their institution’s efforts to improve influenza vaccination rates.

They found that in the first year after the mandatory influenza requirement was put in place, 97.6% of the facility’s 4,703 health care workers were vaccinated, followed by adherence rates of more than 98% in the following 4 years. Less than 0.7% of the center’s workers were exempted from vaccination for medical or religious reasons, and less than 0.2% refused vaccinated or left employment at the center (Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2010;31:881-8).

“Influenza vaccination of health care providers is a professional and ethical obligation … to prevent the spread of influenza, an infection that can spread rapidly through an institution,” Dr. Fishman said.

Disclosures: Dr. Fishman reported no conflicts of interest. The authors of SHEA’s position paper reported having served as consultants for or having received honoraria from various companies that make vaccines, influenza diagnostics, and pharmaceuticals.

SHEA Calls for Mandatory Influenza Vaccination for Health Care Workers

All health care workers should be vaccinated annually against influenza, and doing so should be a condition of new or continued employment, according to a position paper from the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America.

This is the first time the organization has recommended mandatory vaccination of all health care workers; and its position was also endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

“I am very hopeful that this guideline will encourage the adoption of more mandatory policies at all health care institutions,” said Dr. Neil Fishman, president of SHEA and director of health care epidemiology and infection control for the University of Pennsylvania Health System, Philadelphia.

A variety of vaccinations already are required at health care facilities, including measles, mumps and rubella, and some facilities also require vaccination against chickenpox, pertussis, and hepatitis B. “So there are precedents for having vaccines as a condition of employment,” Dr. Fishman said.

The hope is that SHEA’s new recommendation – published Aug. 31 in the journal Infection Control and Healthcare Epidemiology – will improve the current influenza vaccination rates for health care workers, which now hover in the 30%-40% range, Dr. Fishman said. The recommendation applies to all workers, students, and volunteers in all health care facilities, regardless of whether they have direct patient contact.

Under the SHEA position paper, the only exceptions to the mandatory vaccination policy would be for medical reasons, such as a severe allergy to eggs, Dr. Fishman said.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommends that all health care professionals get an annual influenza vaccine and that health care facilities provide the vaccine to its workers with a goal of vaccinating 100% of staff.

Some health facilities and systems already require influenza vaccination as a condition of employment. The University of Pennsylvania Health System, where Dr. Fishman works, has required flu vaccination for its workers since 2009.

Researchers at the Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle – believed to be the first in the country to institute mandatory influenza vaccination for its health care workers in 2005 – recently studied their institution’s efforts to improve influenza vaccination rates.

They found that in the first year after the mandatory influenza requirement was put in place, 97.6% of the facility’s 4,703 health care workers were vaccinated, followed by adherence rates of more than 98% in the following 4 years. Less than 0.7% of the center’s workers were exempted from vaccination for medical or religious reasons, and less than 0.2% refused vaccination or left employment at the center (Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2010;31:881-8).

“Influenza vaccination of health care providers is a professional and ethical obligation ... to prevent the spread of influenza, an infection that can spread rapidly through an institution,” Dr. Fishman said.

Dr. Fishman reported no conflicts of interest. The authors of SHEA’s position paper reported having served as consultants for or having received honoraria from various companies that make vaccines, influenza diagnostics, and pharmaceuticals.

All health care workers should be vaccinated annually against influenza, and doing so should be a condition of new or continued employment, according to a position paper from the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America.

This is the first time the organization has recommended mandatory vaccination of all health care workers; and its position was also endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

“I am very hopeful that this guideline will encourage the adoption of more mandatory policies at all health care institutions,” said Dr. Neil Fishman, president of SHEA and director of health care epidemiology and infection control for the University of Pennsylvania Health System, Philadelphia.

A variety of vaccinations already are required at health care facilities, including measles, mumps and rubella, and some facilities also require vaccination against chickenpox, pertussis, and hepatitis B. “So there are precedents for having vaccines as a condition of employment,” Dr. Fishman said.

The hope is that SHEA’s new recommendation – published Aug. 31 in the journal Infection Control and Healthcare Epidemiology – will improve the current influenza vaccination rates for health care workers, which now hover in the 30%-40% range, Dr. Fishman said. The recommendation applies to all workers, students, and volunteers in all health care facilities, regardless of whether they have direct patient contact.