User login

Ergonomics 101 for trainees

To the early trainee, often the goal of performing a colonoscopy is to reach the cecum using whatever technique necessary. Although the recommended amount of colonoscopies for safe independent practice is 140 (with some sources stating more than 500), this only relates to the safety of the patient.1 We receive scant education on how to form good procedural habits to preserve our own safety and efficiency over the course of our career. Here are some tips on how to prevent injury:

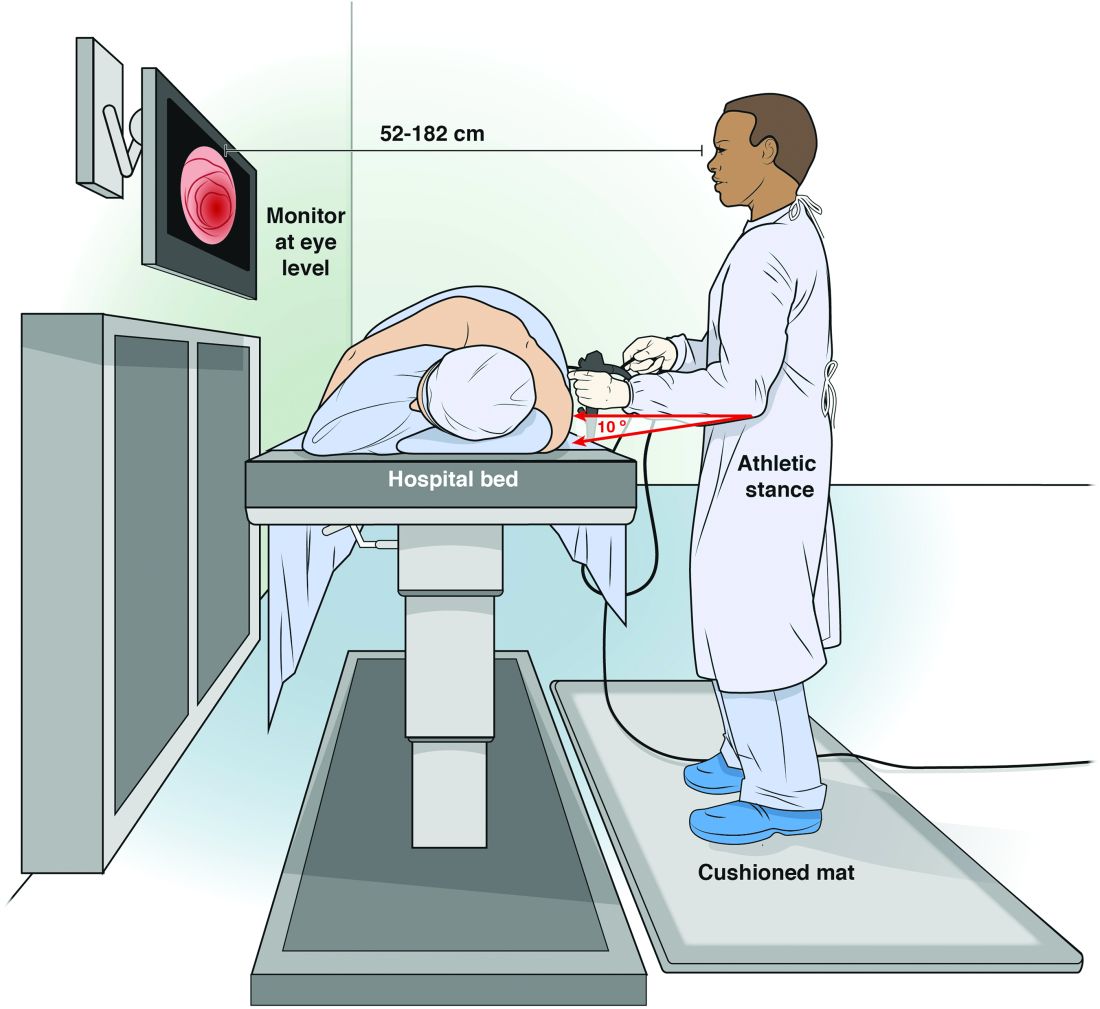

Maintain an appropriate stance. The optimal stance during endoscopy is an athletic stance: chest out, shoulders back to facilitate ease of neck movements, and a slight bend in the knees to facilitate good blood return and distribute weight. Feet should be hip width apart with toes pointed at the endoscopy screen to allow for easy pivoting of the hips and torque of upper body if needed. Ideally, this stance is complemented by the use of proper footwear and a cushioned mat to facilitate weight distribution while standing. An athletic stance facilitates a fluidity for movements from head to toe and an ability to use larger muscles groups to accomplish fine movements.

Handle the endoscope properly. Preserve energy by understanding your equipment and how to manipulate it. Orienting the endoscope directly in front of the endoscopist for upper endoscopy, and at a 45-degree angle for colonoscopy, places the instrument at optimal location to complete the procedure.5 Reviewing how to perform common techniques such as retroflexion, scope reduction, and instrumentation can also facilitate improved ergonomics and adjustment of incorrect techniques at an early stage of endoscopic training. An area of particular concern for most early trainees is the amount of rotational force placed on the right wrist with administration of torque to the endoscope. This is a foreign movement for most endoscopists and requires use of smaller muscle groups of the forearms. We suggest attempting torque with internal and external rotation of the left shoulder to utilize larger muscle groups. We can also combat fatigue during the procedure with the use of microrests intermittently to reduce prolonged muscle contraction. A common way to utilize microrests is by pinning the scope to the patient’s bed with the endoscopist’s hip to provide stability of endoscope and allow removal and relaxation of the right hand. This can be done periodically throughout the procedure to provide the ability to regroup mentally and physically.

Seek feedback. Because it is difficult to focus on ergonomics while performing a diagnostic procedure, utilize your team of observers to facilitate proper form during procedure. This includes your attending gastroenterologists, nurses, and technicians who can observe posture and technique to help detect incorrect positioning early and make corrections. A common practice is to discuss areas of desired improvement before procedures to facilitate a more vigilant observation of areas for improvement.

Assess and adjust often. As early trainees, these endoscopists perform all endoscopies under the direct supervision and often with significant assistance from a supervising gastroenterologist. This can lead to a sharp differential in psychological size; it can be hard to adjust a room to your needs when you have an intimidating and demanding attending physician who has different needs. Despite this disparity, we strongly encourage all trainees to be vigilant about adjusting the room (monitors and beds) to their own needs rather than their attendings’. A great way to head off potential conflict is to discuss the ergonomic positioning of the room before you start endoscopy with your attending, nurse, and technicians so that everyone is in agreement.

Conclusion

We offer this article as a guide for the novice endoscopist to make small changes early to prevent injuries later. Reaching competency with our skills is difficult, and we hope it can be achieved safely with our health in mind.

Dr. Magee, first-year fellow, NCC Gastroenterology; Dr. Singla, associate program director, NCC Gastroenterology, and gastroenterology service, department of internal medicine, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md.

References

1. Spier B et al. Colonoscopy training in gastroenterology fellowships: determining competence. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010 Feb;71(2):319-24G.

2. Malmström EM et al. A slouched body posture decreases arm mobility and changes muscle recruitment in the neck and shoulder region. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2015;115(12):2491-503.

3. Singla M et al. Training the endo-athlete: an update in ergonomics in endoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Jul;16(7):1003-6.

4. Bexander CS, et al. Effect of gaze direction on neck muscle activity during cervical rotation. Exp Brain Res. 2005 Dec;167(3):422-32.

5. Soetikno R et al. Holding and manipulating the endoscope: A user’s guide. Techn Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;21:124-32.

To the early trainee, often the goal of performing a colonoscopy is to reach the cecum using whatever technique necessary. Although the recommended amount of colonoscopies for safe independent practice is 140 (with some sources stating more than 500), this only relates to the safety of the patient.1 We receive scant education on how to form good procedural habits to preserve our own safety and efficiency over the course of our career. Here are some tips on how to prevent injury:

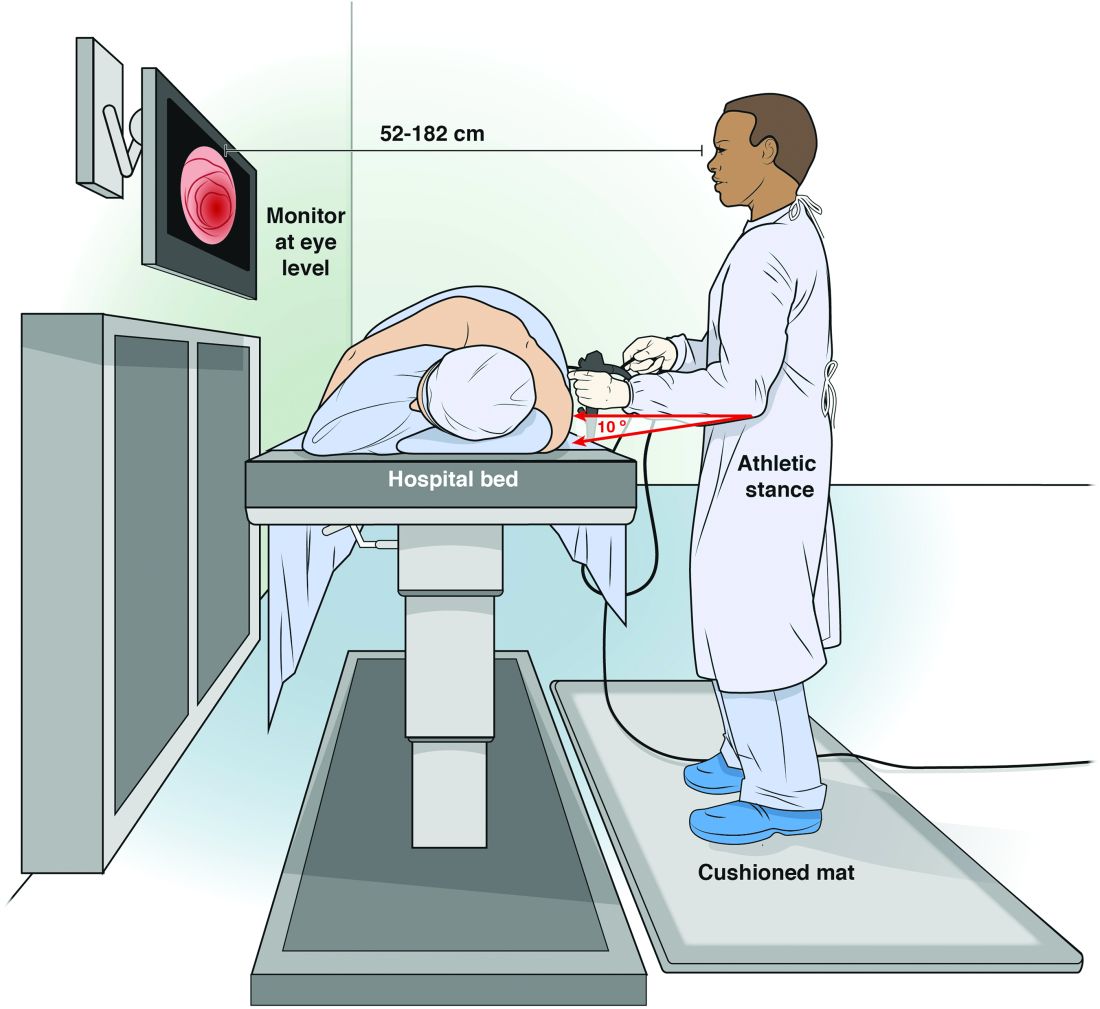

Maintain an appropriate stance. The optimal stance during endoscopy is an athletic stance: chest out, shoulders back to facilitate ease of neck movements, and a slight bend in the knees to facilitate good blood return and distribute weight. Feet should be hip width apart with toes pointed at the endoscopy screen to allow for easy pivoting of the hips and torque of upper body if needed. Ideally, this stance is complemented by the use of proper footwear and a cushioned mat to facilitate weight distribution while standing. An athletic stance facilitates a fluidity for movements from head to toe and an ability to use larger muscles groups to accomplish fine movements.

Handle the endoscope properly. Preserve energy by understanding your equipment and how to manipulate it. Orienting the endoscope directly in front of the endoscopist for upper endoscopy, and at a 45-degree angle for colonoscopy, places the instrument at optimal location to complete the procedure.5 Reviewing how to perform common techniques such as retroflexion, scope reduction, and instrumentation can also facilitate improved ergonomics and adjustment of incorrect techniques at an early stage of endoscopic training. An area of particular concern for most early trainees is the amount of rotational force placed on the right wrist with administration of torque to the endoscope. This is a foreign movement for most endoscopists and requires use of smaller muscle groups of the forearms. We suggest attempting torque with internal and external rotation of the left shoulder to utilize larger muscle groups. We can also combat fatigue during the procedure with the use of microrests intermittently to reduce prolonged muscle contraction. A common way to utilize microrests is by pinning the scope to the patient’s bed with the endoscopist’s hip to provide stability of endoscope and allow removal and relaxation of the right hand. This can be done periodically throughout the procedure to provide the ability to regroup mentally and physically.

Seek feedback. Because it is difficult to focus on ergonomics while performing a diagnostic procedure, utilize your team of observers to facilitate proper form during procedure. This includes your attending gastroenterologists, nurses, and technicians who can observe posture and technique to help detect incorrect positioning early and make corrections. A common practice is to discuss areas of desired improvement before procedures to facilitate a more vigilant observation of areas for improvement.

Assess and adjust often. As early trainees, these endoscopists perform all endoscopies under the direct supervision and often with significant assistance from a supervising gastroenterologist. This can lead to a sharp differential in psychological size; it can be hard to adjust a room to your needs when you have an intimidating and demanding attending physician who has different needs. Despite this disparity, we strongly encourage all trainees to be vigilant about adjusting the room (monitors and beds) to their own needs rather than their attendings’. A great way to head off potential conflict is to discuss the ergonomic positioning of the room before you start endoscopy with your attending, nurse, and technicians so that everyone is in agreement.

Conclusion

We offer this article as a guide for the novice endoscopist to make small changes early to prevent injuries later. Reaching competency with our skills is difficult, and we hope it can be achieved safely with our health in mind.

Dr. Magee, first-year fellow, NCC Gastroenterology; Dr. Singla, associate program director, NCC Gastroenterology, and gastroenterology service, department of internal medicine, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md.

References

1. Spier B et al. Colonoscopy training in gastroenterology fellowships: determining competence. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010 Feb;71(2):319-24G.

2. Malmström EM et al. A slouched body posture decreases arm mobility and changes muscle recruitment in the neck and shoulder region. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2015;115(12):2491-503.

3. Singla M et al. Training the endo-athlete: an update in ergonomics in endoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Jul;16(7):1003-6.

4. Bexander CS, et al. Effect of gaze direction on neck muscle activity during cervical rotation. Exp Brain Res. 2005 Dec;167(3):422-32.

5. Soetikno R et al. Holding and manipulating the endoscope: A user’s guide. Techn Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;21:124-32.

To the early trainee, often the goal of performing a colonoscopy is to reach the cecum using whatever technique necessary. Although the recommended amount of colonoscopies for safe independent practice is 140 (with some sources stating more than 500), this only relates to the safety of the patient.1 We receive scant education on how to form good procedural habits to preserve our own safety and efficiency over the course of our career. Here are some tips on how to prevent injury:

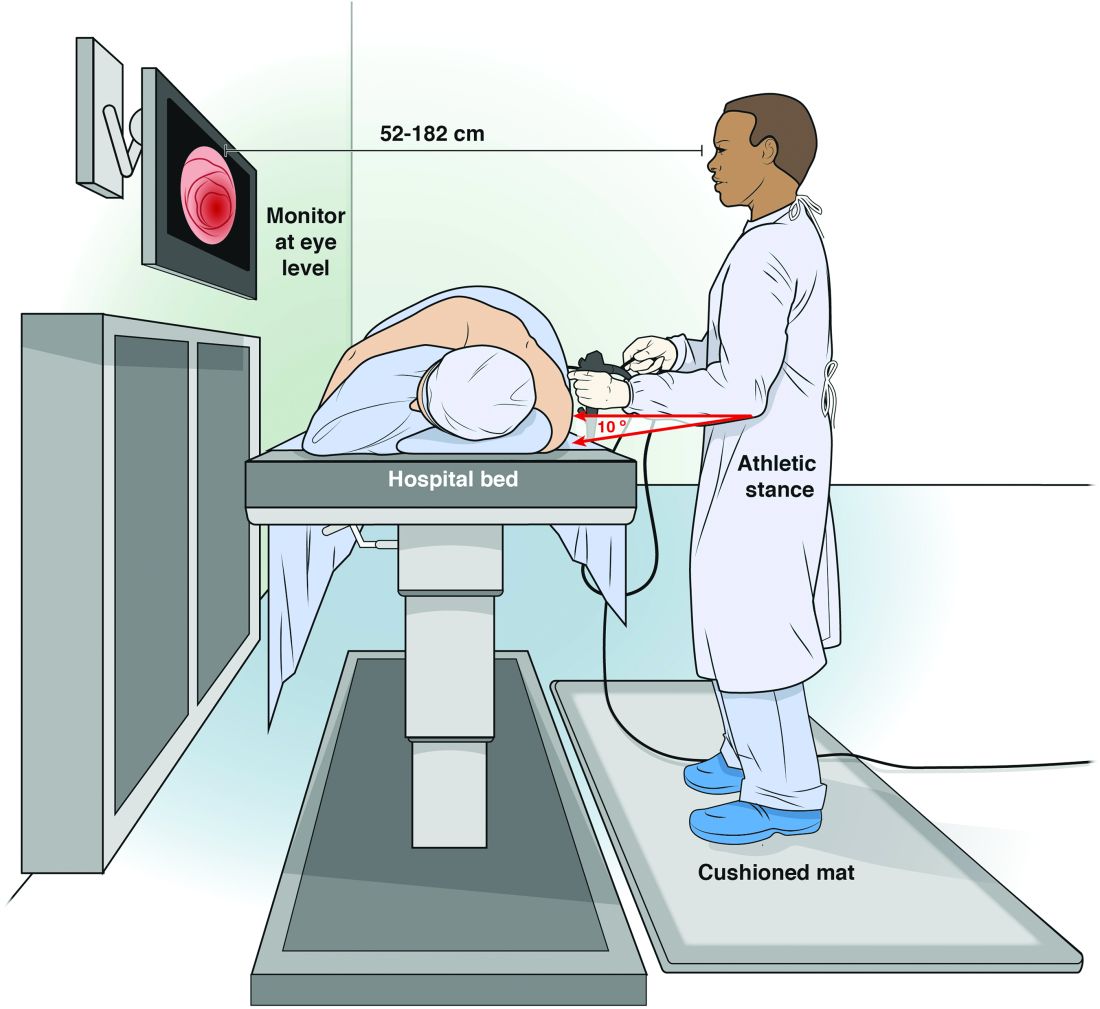

Maintain an appropriate stance. The optimal stance during endoscopy is an athletic stance: chest out, shoulders back to facilitate ease of neck movements, and a slight bend in the knees to facilitate good blood return and distribute weight. Feet should be hip width apart with toes pointed at the endoscopy screen to allow for easy pivoting of the hips and torque of upper body if needed. Ideally, this stance is complemented by the use of proper footwear and a cushioned mat to facilitate weight distribution while standing. An athletic stance facilitates a fluidity for movements from head to toe and an ability to use larger muscles groups to accomplish fine movements.

Handle the endoscope properly. Preserve energy by understanding your equipment and how to manipulate it. Orienting the endoscope directly in front of the endoscopist for upper endoscopy, and at a 45-degree angle for colonoscopy, places the instrument at optimal location to complete the procedure.5 Reviewing how to perform common techniques such as retroflexion, scope reduction, and instrumentation can also facilitate improved ergonomics and adjustment of incorrect techniques at an early stage of endoscopic training. An area of particular concern for most early trainees is the amount of rotational force placed on the right wrist with administration of torque to the endoscope. This is a foreign movement for most endoscopists and requires use of smaller muscle groups of the forearms. We suggest attempting torque with internal and external rotation of the left shoulder to utilize larger muscle groups. We can also combat fatigue during the procedure with the use of microrests intermittently to reduce prolonged muscle contraction. A common way to utilize microrests is by pinning the scope to the patient’s bed with the endoscopist’s hip to provide stability of endoscope and allow removal and relaxation of the right hand. This can be done periodically throughout the procedure to provide the ability to regroup mentally and physically.

Seek feedback. Because it is difficult to focus on ergonomics while performing a diagnostic procedure, utilize your team of observers to facilitate proper form during procedure. This includes your attending gastroenterologists, nurses, and technicians who can observe posture and technique to help detect incorrect positioning early and make corrections. A common practice is to discuss areas of desired improvement before procedures to facilitate a more vigilant observation of areas for improvement.

Assess and adjust often. As early trainees, these endoscopists perform all endoscopies under the direct supervision and often with significant assistance from a supervising gastroenterologist. This can lead to a sharp differential in psychological size; it can be hard to adjust a room to your needs when you have an intimidating and demanding attending physician who has different needs. Despite this disparity, we strongly encourage all trainees to be vigilant about adjusting the room (monitors and beds) to their own needs rather than their attendings’. A great way to head off potential conflict is to discuss the ergonomic positioning of the room before you start endoscopy with your attending, nurse, and technicians so that everyone is in agreement.

Conclusion

We offer this article as a guide for the novice endoscopist to make small changes early to prevent injuries later. Reaching competency with our skills is difficult, and we hope it can be achieved safely with our health in mind.

Dr. Magee, first-year fellow, NCC Gastroenterology; Dr. Singla, associate program director, NCC Gastroenterology, and gastroenterology service, department of internal medicine, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md.

References

1. Spier B et al. Colonoscopy training in gastroenterology fellowships: determining competence. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010 Feb;71(2):319-24G.

2. Malmström EM et al. A slouched body posture decreases arm mobility and changes muscle recruitment in the neck and shoulder region. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2015;115(12):2491-503.

3. Singla M et al. Training the endo-athlete: an update in ergonomics in endoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Jul;16(7):1003-6.

4. Bexander CS, et al. Effect of gaze direction on neck muscle activity during cervical rotation. Exp Brain Res. 2005 Dec;167(3):422-32.

5. Soetikno R et al. Holding and manipulating the endoscope: A user’s guide. Techn Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;21:124-32.