User login

Ruling out delirium: Therapeutic principles of withdrawing and changing medications

Ms. M, age 71, was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease several months ago and her clinical presentation and Mini-Mental Status Exam score of 22 indicates mild dementia. In addition to chronic medications for hypertension, Ms. M has been taking lorazepam, 1 mg, 3 times daily, for >15 years for unspecified anxiety.

Ms. M becomes more confused at home over the course of a few days, and her daughter brings her to her primary care physician for evaluation. Recognizing that benzodiazepines can contribute to delirium, the physician discontinues lorazepam. Three days later, Ms. M’s confusion worsens, and she develops nausea and a tremor. She is taken to the local emergency department where she is admitted for benzodiazepine withdrawal and diagnosed with a urinary tract infection.

Because dementia is a strong risk factor for developing delirium,1 withdrawing or changing

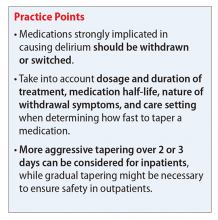

Consider withdrawing or replacing medications that are strongly implicated in causing delirium with another medication for the same indication with a lower potential for

In general, there are no firm rules for how to taper and discontinue potentially deliriogenic medications, as both the need to taper and the best strategy for doing so depends on a number of factors and requires clinical judgement. When determining how quickly to withdraw a potentially offending medication in a patient with suspected delirium, clinicians should consider:

Dosage and duration of treatment. Consider tapering and discontinuing benzodiazepines in a patient who is taking more than the minimal scheduled dosages for ≥2 weeks, especially after 8 weeks of scheduled treatment. Consider tapering opioids in a patient taking more than the minimal scheduled dosage for more than a few days. When attempting to rule out delirium, taper opioids as quickly and as safely possible, with a recommended reduction of ≤20% per day to prevent withdrawal symptoms. In general, potentially deliriogenic medications can be discontinued without tapering if they are taken on a non-daily, as-needed basis.

The half-life of a medication determines both the onset and duration of withdrawal symptoms. Withdrawal occurs earlier when discontinuing medications with short

Nature of withdrawal symptoms. In patients with suspected delirium, tapering over weeks or

Care setting. When tapering and discontinuing a medication, regularly monitor patients for withdrawal symptoms; slow or temporarily stop the taper if withdrawal symptoms occur. Because close monitoring is easier in an inpatient vs an outpatient care setting, more aggressive tapering over 2 to 3 days generally can be considered, although more gradual tapering might be prudent to ensure safety of outpatients.

1. Inouye SK. Delirium in older persons. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(11):1157-1165.

2. Alagiakrishnan K, Wiens CA. An approach to drug induced delirium in the elderly. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80(945):388-393.

3. Clegg A, Young JB. Which medications to avoid in people at risk of delirium: a systematic review. Age Aging. 2010;40(1):23-29.

4. Han L, McCusker J, Cole M, et al. Use of medications with anticholinergic effect predicts clinical severity of delirium symptoms in older medical inpatients. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(8):1099-1105.

5. Carnahan RM, Lund BC, Perry PJ, et al. The Anticholinergic Drug Scale as a measure of drug-related anticholinergic burden: associations with serum anticholinergic activity. J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;46(12):1481-1486.

6. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227-2246.

Ms. M, age 71, was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease several months ago and her clinical presentation and Mini-Mental Status Exam score of 22 indicates mild dementia. In addition to chronic medications for hypertension, Ms. M has been taking lorazepam, 1 mg, 3 times daily, for >15 years for unspecified anxiety.

Ms. M becomes more confused at home over the course of a few days, and her daughter brings her to her primary care physician for evaluation. Recognizing that benzodiazepines can contribute to delirium, the physician discontinues lorazepam. Three days later, Ms. M’s confusion worsens, and she develops nausea and a tremor. She is taken to the local emergency department where she is admitted for benzodiazepine withdrawal and diagnosed with a urinary tract infection.

Because dementia is a strong risk factor for developing delirium,1 withdrawing or changing

Consider withdrawing or replacing medications that are strongly implicated in causing delirium with another medication for the same indication with a lower potential for

In general, there are no firm rules for how to taper and discontinue potentially deliriogenic medications, as both the need to taper and the best strategy for doing so depends on a number of factors and requires clinical judgement. When determining how quickly to withdraw a potentially offending medication in a patient with suspected delirium, clinicians should consider:

Dosage and duration of treatment. Consider tapering and discontinuing benzodiazepines in a patient who is taking more than the minimal scheduled dosages for ≥2 weeks, especially after 8 weeks of scheduled treatment. Consider tapering opioids in a patient taking more than the minimal scheduled dosage for more than a few days. When attempting to rule out delirium, taper opioids as quickly and as safely possible, with a recommended reduction of ≤20% per day to prevent withdrawal symptoms. In general, potentially deliriogenic medications can be discontinued without tapering if they are taken on a non-daily, as-needed basis.

The half-life of a medication determines both the onset and duration of withdrawal symptoms. Withdrawal occurs earlier when discontinuing medications with short

Nature of withdrawal symptoms. In patients with suspected delirium, tapering over weeks or

Care setting. When tapering and discontinuing a medication, regularly monitor patients for withdrawal symptoms; slow or temporarily stop the taper if withdrawal symptoms occur. Because close monitoring is easier in an inpatient vs an outpatient care setting, more aggressive tapering over 2 to 3 days generally can be considered, although more gradual tapering might be prudent to ensure safety of outpatients.

Ms. M, age 71, was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease several months ago and her clinical presentation and Mini-Mental Status Exam score of 22 indicates mild dementia. In addition to chronic medications for hypertension, Ms. M has been taking lorazepam, 1 mg, 3 times daily, for >15 years for unspecified anxiety.

Ms. M becomes more confused at home over the course of a few days, and her daughter brings her to her primary care physician for evaluation. Recognizing that benzodiazepines can contribute to delirium, the physician discontinues lorazepam. Three days later, Ms. M’s confusion worsens, and she develops nausea and a tremor. She is taken to the local emergency department where she is admitted for benzodiazepine withdrawal and diagnosed with a urinary tract infection.

Because dementia is a strong risk factor for developing delirium,1 withdrawing or changing

Consider withdrawing or replacing medications that are strongly implicated in causing delirium with another medication for the same indication with a lower potential for

In general, there are no firm rules for how to taper and discontinue potentially deliriogenic medications, as both the need to taper and the best strategy for doing so depends on a number of factors and requires clinical judgement. When determining how quickly to withdraw a potentially offending medication in a patient with suspected delirium, clinicians should consider:

Dosage and duration of treatment. Consider tapering and discontinuing benzodiazepines in a patient who is taking more than the minimal scheduled dosages for ≥2 weeks, especially after 8 weeks of scheduled treatment. Consider tapering opioids in a patient taking more than the minimal scheduled dosage for more than a few days. When attempting to rule out delirium, taper opioids as quickly and as safely possible, with a recommended reduction of ≤20% per day to prevent withdrawal symptoms. In general, potentially deliriogenic medications can be discontinued without tapering if they are taken on a non-daily, as-needed basis.

The half-life of a medication determines both the onset and duration of withdrawal symptoms. Withdrawal occurs earlier when discontinuing medications with short

Nature of withdrawal symptoms. In patients with suspected delirium, tapering over weeks or

Care setting. When tapering and discontinuing a medication, regularly monitor patients for withdrawal symptoms; slow or temporarily stop the taper if withdrawal symptoms occur. Because close monitoring is easier in an inpatient vs an outpatient care setting, more aggressive tapering over 2 to 3 days generally can be considered, although more gradual tapering might be prudent to ensure safety of outpatients.

1. Inouye SK. Delirium in older persons. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(11):1157-1165.

2. Alagiakrishnan K, Wiens CA. An approach to drug induced delirium in the elderly. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80(945):388-393.

3. Clegg A, Young JB. Which medications to avoid in people at risk of delirium: a systematic review. Age Aging. 2010;40(1):23-29.

4. Han L, McCusker J, Cole M, et al. Use of medications with anticholinergic effect predicts clinical severity of delirium symptoms in older medical inpatients. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(8):1099-1105.

5. Carnahan RM, Lund BC, Perry PJ, et al. The Anticholinergic Drug Scale as a measure of drug-related anticholinergic burden: associations with serum anticholinergic activity. J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;46(12):1481-1486.

6. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227-2246.

1. Inouye SK. Delirium in older persons. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(11):1157-1165.

2. Alagiakrishnan K, Wiens CA. An approach to drug induced delirium in the elderly. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80(945):388-393.

3. Clegg A, Young JB. Which medications to avoid in people at risk of delirium: a systematic review. Age Aging. 2010;40(1):23-29.

4. Han L, McCusker J, Cole M, et al. Use of medications with anticholinergic effect predicts clinical severity of delirium symptoms in older medical inpatients. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(8):1099-1105.

5. Carnahan RM, Lund BC, Perry PJ, et al. The Anticholinergic Drug Scale as a measure of drug-related anticholinergic burden: associations with serum anticholinergic activity. J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;46(12):1481-1486.

6. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227-2246.