User login

Man's Condition Gets Out of Hand

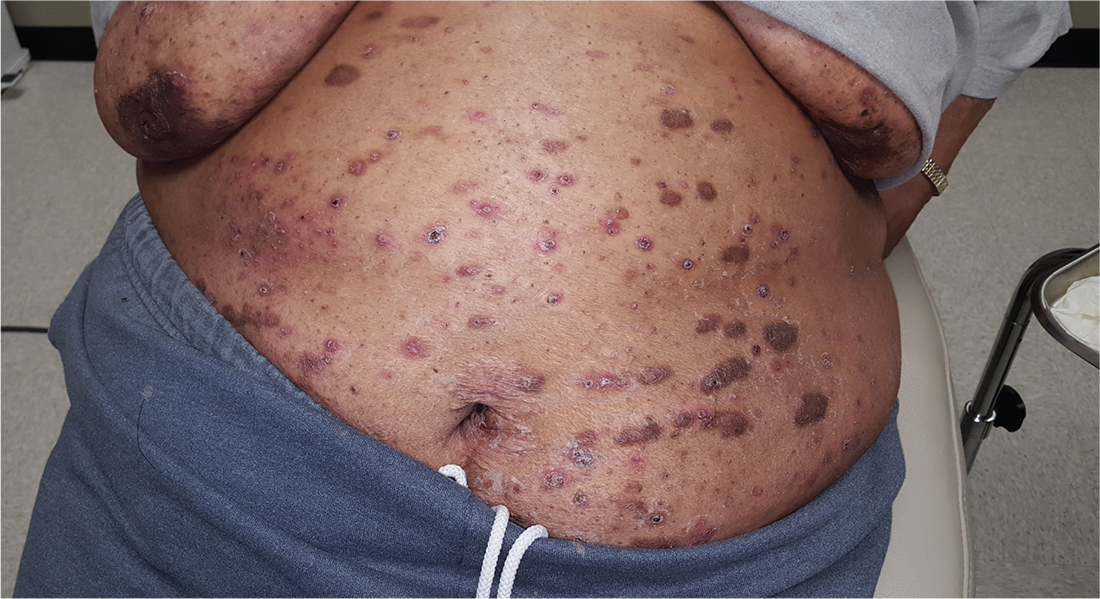

This 46-year-old man’s skin disease has gotten so serious that he is essentially disabled. The problem started about six months ago, with joint pain that particularly affected his left ankle. Now, his hands are fissured and swollen to the point that he is unable to button his shirt or hold a fork. He is referred to dermatology by his attorney, who is helping him pursue possible disability benefits, for evaluation and treatment.

He has been seen by a variety of primary care providers, who have collectively prescribed topical triamcinolone 0.1% and several antifungal medications, including a two-month course of oral terbinafine. When those failed, he was treated with prednisone; at the start of the three-week course, there were signs of improvement but by the end, his hands were worse than ever.

EXAMINATION

The dorsal and palmar surfaces of the patient’s hands are covered with thick, white scales atop salmon-colored erythematous bases. Multiple fissures and marked edema can be seen. Seven of 10 fingernails are dystrophic, yellowed, and thickened.

The patient’s elbows, knees, and upper intergluteal area show less impressive involvement.

There is marked tenderness on palpation of the left Achilles insertion, made worse by dorsiflexion.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Psoriasis can affect one or more areas, typically the hands, scalp, genitals, or feet. When it’s focused in one area, as in this case, it can be baffling to diagnose; sometimes it’s hard to see the forest for the trees. But because the condition affects almost 3% of white Americans, you’ll see it regularly—if you’re looking for it.

Nearly 25% of patients with psoriasis eventually develop psoriatic arthritis (PsA), which not only affects the joints but also can cause complications such as enthesitis, or inflammation of the entheses (the sites of insertion of the tendon into bone; eg, the Achilles). This can be confused with plantar fasciitis, which this patient had been previously diagnosed with.

This diagnosis could have been proved or disproved by a KOH prep (which would have shown evidence of fungal disease) or a biopsy (which would have shown fused rete ridges, microabscesses at the papillary tips, hyperkeratosis, and parakeratosis). Providers should first establish a firm diagnosis to dictate effective treatment. In this case, a visual diagnosis was possible.

Given the severity of the problem, the patient was started on a biologic; he showed vast improvement within a week. He was referred to rheumatology for evaluation and management of PsA, and the severity of his disease was communicated to his attorney.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- In some cases, psoriasis can be isolated to the hands, feet, genitals, or scalp, complicating detection of the condition.

- Almost 25% of patients with psoriasis develop psoriatic arthritis (PsA), which can manifest with dactylitis, arthritis, or enthesitis.

- Left untreated, PsA is potentially debilitating.

- Establishing a firm diagnosis with KOH prep or biopsy will dictate effective treatment.

This 46-year-old man’s skin disease has gotten so serious that he is essentially disabled. The problem started about six months ago, with joint pain that particularly affected his left ankle. Now, his hands are fissured and swollen to the point that he is unable to button his shirt or hold a fork. He is referred to dermatology by his attorney, who is helping him pursue possible disability benefits, for evaluation and treatment.

He has been seen by a variety of primary care providers, who have collectively prescribed topical triamcinolone 0.1% and several antifungal medications, including a two-month course of oral terbinafine. When those failed, he was treated with prednisone; at the start of the three-week course, there were signs of improvement but by the end, his hands were worse than ever.

EXAMINATION

The dorsal and palmar surfaces of the patient’s hands are covered with thick, white scales atop salmon-colored erythematous bases. Multiple fissures and marked edema can be seen. Seven of 10 fingernails are dystrophic, yellowed, and thickened.

The patient’s elbows, knees, and upper intergluteal area show less impressive involvement.

There is marked tenderness on palpation of the left Achilles insertion, made worse by dorsiflexion.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Psoriasis can affect one or more areas, typically the hands, scalp, genitals, or feet. When it’s focused in one area, as in this case, it can be baffling to diagnose; sometimes it’s hard to see the forest for the trees. But because the condition affects almost 3% of white Americans, you’ll see it regularly—if you’re looking for it.

Nearly 25% of patients with psoriasis eventually develop psoriatic arthritis (PsA), which not only affects the joints but also can cause complications such as enthesitis, or inflammation of the entheses (the sites of insertion of the tendon into bone; eg, the Achilles). This can be confused with plantar fasciitis, which this patient had been previously diagnosed with.

This diagnosis could have been proved or disproved by a KOH prep (which would have shown evidence of fungal disease) or a biopsy (which would have shown fused rete ridges, microabscesses at the papillary tips, hyperkeratosis, and parakeratosis). Providers should first establish a firm diagnosis to dictate effective treatment. In this case, a visual diagnosis was possible.

Given the severity of the problem, the patient was started on a biologic; he showed vast improvement within a week. He was referred to rheumatology for evaluation and management of PsA, and the severity of his disease was communicated to his attorney.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- In some cases, psoriasis can be isolated to the hands, feet, genitals, or scalp, complicating detection of the condition.

- Almost 25% of patients with psoriasis develop psoriatic arthritis (PsA), which can manifest with dactylitis, arthritis, or enthesitis.

- Left untreated, PsA is potentially debilitating.

- Establishing a firm diagnosis with KOH prep or biopsy will dictate effective treatment.

This 46-year-old man’s skin disease has gotten so serious that he is essentially disabled. The problem started about six months ago, with joint pain that particularly affected his left ankle. Now, his hands are fissured and swollen to the point that he is unable to button his shirt or hold a fork. He is referred to dermatology by his attorney, who is helping him pursue possible disability benefits, for evaluation and treatment.

He has been seen by a variety of primary care providers, who have collectively prescribed topical triamcinolone 0.1% and several antifungal medications, including a two-month course of oral terbinafine. When those failed, he was treated with prednisone; at the start of the three-week course, there were signs of improvement but by the end, his hands were worse than ever.

EXAMINATION

The dorsal and palmar surfaces of the patient’s hands are covered with thick, white scales atop salmon-colored erythematous bases. Multiple fissures and marked edema can be seen. Seven of 10 fingernails are dystrophic, yellowed, and thickened.

The patient’s elbows, knees, and upper intergluteal area show less impressive involvement.

There is marked tenderness on palpation of the left Achilles insertion, made worse by dorsiflexion.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Psoriasis can affect one or more areas, typically the hands, scalp, genitals, or feet. When it’s focused in one area, as in this case, it can be baffling to diagnose; sometimes it’s hard to see the forest for the trees. But because the condition affects almost 3% of white Americans, you’ll see it regularly—if you’re looking for it.

Nearly 25% of patients with psoriasis eventually develop psoriatic arthritis (PsA), which not only affects the joints but also can cause complications such as enthesitis, or inflammation of the entheses (the sites of insertion of the tendon into bone; eg, the Achilles). This can be confused with plantar fasciitis, which this patient had been previously diagnosed with.

This diagnosis could have been proved or disproved by a KOH prep (which would have shown evidence of fungal disease) or a biopsy (which would have shown fused rete ridges, microabscesses at the papillary tips, hyperkeratosis, and parakeratosis). Providers should first establish a firm diagnosis to dictate effective treatment. In this case, a visual diagnosis was possible.

Given the severity of the problem, the patient was started on a biologic; he showed vast improvement within a week. He was referred to rheumatology for evaluation and management of PsA, and the severity of his disease was communicated to his attorney.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- In some cases, psoriasis can be isolated to the hands, feet, genitals, or scalp, complicating detection of the condition.

- Almost 25% of patients with psoriasis develop psoriatic arthritis (PsA), which can manifest with dactylitis, arthritis, or enthesitis.

- Left untreated, PsA is potentially debilitating.

- Establishing a firm diagnosis with KOH prep or biopsy will dictate effective treatment.

Could This Lesion Be Deadly?

ANSWER

The correct diagnosis is blue nevus (BN; choice “d”).

Some BNs can mimic melanomas (choice “a”), and vice versa. These cases often have to be sent to consultants, and sometimes even they can’t agree. For this reason, there is a low threshold for removal if there’s any question of change or family history of melanoma—which were missing in this case.

Kaposi sarcoma (KS; choice “b”) is a type of cancer caused by human herpesvirus-8 that affects the inner lining of blood vessels and manifests with dark macules or nodules. But outside the context of HIV/AIDS, KS is quite rare.

This lesion could have been an angioma (choice “c”), but its history and dark blue color made that diagnosis unlikely. In younger patients, angiomas are typically bright red. Only later, in the sixth and seventh decades of life, do they take on a dark appearance.

DISCUSSION

BNs are benign melanocytic nevi that typically appear on the trunk or upper extremities during the second or third decade of life. There are several varieties, the most common of which (and the type seen in this case) is Jadassohn-Tieche. The steel-blue color and planar surface of this patient’s lesion are typical.

Histologically, BNs are composed mostly of pigmented melanocytes that congregate deep in the dermis (unlike normal melanocytes, which typically line the dermo-epidermal junction). While these melanocytes are usually brown, they take on a bluish hue when they develop on a deeper level of skin—a phenomenon known as the Tyndall effect.

It can be challenging to differentiate a BN from a melanoma, even with a microscope. Sometimes the answer is to treat the lesion as though it were a melanoma by excising it with wide margins.

In this case, given the benign appearance and history, the decision was made to leave it alone unless it changes. Excision might have been a good option, but the patient’s type IV skin and the lesion’s location made scarring a likely possibility.

ANSWER

The correct diagnosis is blue nevus (BN; choice “d”).

Some BNs can mimic melanomas (choice “a”), and vice versa. These cases often have to be sent to consultants, and sometimes even they can’t agree. For this reason, there is a low threshold for removal if there’s any question of change or family history of melanoma—which were missing in this case.

Kaposi sarcoma (KS; choice “b”) is a type of cancer caused by human herpesvirus-8 that affects the inner lining of blood vessels and manifests with dark macules or nodules. But outside the context of HIV/AIDS, KS is quite rare.

This lesion could have been an angioma (choice “c”), but its history and dark blue color made that diagnosis unlikely. In younger patients, angiomas are typically bright red. Only later, in the sixth and seventh decades of life, do they take on a dark appearance.

DISCUSSION

BNs are benign melanocytic nevi that typically appear on the trunk or upper extremities during the second or third decade of life. There are several varieties, the most common of which (and the type seen in this case) is Jadassohn-Tieche. The steel-blue color and planar surface of this patient’s lesion are typical.

Histologically, BNs are composed mostly of pigmented melanocytes that congregate deep in the dermis (unlike normal melanocytes, which typically line the dermo-epidermal junction). While these melanocytes are usually brown, they take on a bluish hue when they develop on a deeper level of skin—a phenomenon known as the Tyndall effect.

It can be challenging to differentiate a BN from a melanoma, even with a microscope. Sometimes the answer is to treat the lesion as though it were a melanoma by excising it with wide margins.

In this case, given the benign appearance and history, the decision was made to leave it alone unless it changes. Excision might have been a good option, but the patient’s type IV skin and the lesion’s location made scarring a likely possibility.

ANSWER

The correct diagnosis is blue nevus (BN; choice “d”).

Some BNs can mimic melanomas (choice “a”), and vice versa. These cases often have to be sent to consultants, and sometimes even they can’t agree. For this reason, there is a low threshold for removal if there’s any question of change or family history of melanoma—which were missing in this case.

Kaposi sarcoma (KS; choice “b”) is a type of cancer caused by human herpesvirus-8 that affects the inner lining of blood vessels and manifests with dark macules or nodules. But outside the context of HIV/AIDS, KS is quite rare.

This lesion could have been an angioma (choice “c”), but its history and dark blue color made that diagnosis unlikely. In younger patients, angiomas are typically bright red. Only later, in the sixth and seventh decades of life, do they take on a dark appearance.

DISCUSSION

BNs are benign melanocytic nevi that typically appear on the trunk or upper extremities during the second or third decade of life. There are several varieties, the most common of which (and the type seen in this case) is Jadassohn-Tieche. The steel-blue color and planar surface of this patient’s lesion are typical.

Histologically, BNs are composed mostly of pigmented melanocytes that congregate deep in the dermis (unlike normal melanocytes, which typically line the dermo-epidermal junction). While these melanocytes are usually brown, they take on a bluish hue when they develop on a deeper level of skin—a phenomenon known as the Tyndall effect.

It can be challenging to differentiate a BN from a melanoma, even with a microscope. Sometimes the answer is to treat the lesion as though it were a melanoma by excising it with wide margins.

In this case, given the benign appearance and history, the decision was made to leave it alone unless it changes. Excision might have been a good option, but the patient’s type IV skin and the lesion’s location made scarring a likely possibility.

For years, this 24-year-old woman has had an asymptomatic lesion on her upper arm. Aside from growing a bit, as she has, it has remained basically unchanged.

The bluish black, intradermal, planar nodule is located on the lateral right deltoid. Barely palpable, the 7-mm lesion is neither tender nor particularly firm.

The patient is otherwise healthy. Her type IV skin shows little evidence of sun damage.

A Sore Subject

For several years, a 60-year-old woman has had a nonhealing, asymptomatic “sore” on her upper right cheek. The lesion causes no pain or discomfort; it bothers her simply because it will not go away. It does occasionally bleed.

Several attempts at treatment—including antibiotic ointment, peroxide, and topical alcohol— have failed. A dermatologist once treated the lesion with cryotherapy; this initially reduced its size, but the effect didn’t last.

The patient admits to “worshipping the sun” as a youngster, tanning at every opportunity. Several family members, including her sister and mother, have had skin cancer.

EXAMINATION

A 6.5-mm, round, red nodule is located on the mid-upper right cheek, below the eye. On closer inspection, it appears glassy and translucent, with several obvious telangiectasias. It is surprisingly firm on palpation, though not at all tender to touch.

Elsewhere, the patient’s fair skin has abundant evidence of sun damage, including wrinkles, discoloration, and focal telangiectasias. No other lesions are seen. No nodes are palpable in her head or neck.

With the patient’s permission, and after discussion of the indications, procedure, alternatives, and risks, the lesion is removed by curettement. It is quite friable and shallow, allowing complete removal. The area is left to heal by secondary intention, and the specimen is submitted to pathology.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The pathology report confirmed the suspected diagnosis: noduloulcerative basal cell carcinoma (BCC). By far the most common type of skin cancer in the world, noduloulcerative BCCs are caused by overexposure to the sun.

As obvious as this diagnosis seemed to be, biopsy was warranted to confirm it and to rule out several other items in the differential. The latter include squamous cell carcinoma (which has far more harmful potential than BCC), sebaceous carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, and melanoma.

Not all BCCs are created equal—certain clinical and histologic characteristics predict a more aggressive course. While most BCCs require surgical excision, other treatment options do exist. In this patient’s case, the size and location of the lesion lent it to curettement and healing by secondary intention. Other methods could have included immunotherapy with imiquimod, antitumor creams (eg, 5-fluorouracil), or even radiation therapy. Her lesion was small and well-defined enough that Mohs surgery was not indicated—though some might disagree with that assessment.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Like all basal cell carcinomas (BCCs), ulcerative BCC—the most common type—is caused by overexposure to the sun.

- BCCs are often mistaken for infection or other sore, which delays the diagnosis.

- Nonhealing lesions should be considered cancerous until proven otherwise.

- Though this diagnosis was fairly obvious, biopsy is necessary to rule out other items in the differential—some of which (ie, Merkel cell carcinoma, melanoma) are potentially fatal.

For several years, a 60-year-old woman has had a nonhealing, asymptomatic “sore” on her upper right cheek. The lesion causes no pain or discomfort; it bothers her simply because it will not go away. It does occasionally bleed.

Several attempts at treatment—including antibiotic ointment, peroxide, and topical alcohol— have failed. A dermatologist once treated the lesion with cryotherapy; this initially reduced its size, but the effect didn’t last.

The patient admits to “worshipping the sun” as a youngster, tanning at every opportunity. Several family members, including her sister and mother, have had skin cancer.

EXAMINATION

A 6.5-mm, round, red nodule is located on the mid-upper right cheek, below the eye. On closer inspection, it appears glassy and translucent, with several obvious telangiectasias. It is surprisingly firm on palpation, though not at all tender to touch.

Elsewhere, the patient’s fair skin has abundant evidence of sun damage, including wrinkles, discoloration, and focal telangiectasias. No other lesions are seen. No nodes are palpable in her head or neck.

With the patient’s permission, and after discussion of the indications, procedure, alternatives, and risks, the lesion is removed by curettement. It is quite friable and shallow, allowing complete removal. The area is left to heal by secondary intention, and the specimen is submitted to pathology.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The pathology report confirmed the suspected diagnosis: noduloulcerative basal cell carcinoma (BCC). By far the most common type of skin cancer in the world, noduloulcerative BCCs are caused by overexposure to the sun.

As obvious as this diagnosis seemed to be, biopsy was warranted to confirm it and to rule out several other items in the differential. The latter include squamous cell carcinoma (which has far more harmful potential than BCC), sebaceous carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, and melanoma.

Not all BCCs are created equal—certain clinical and histologic characteristics predict a more aggressive course. While most BCCs require surgical excision, other treatment options do exist. In this patient’s case, the size and location of the lesion lent it to curettement and healing by secondary intention. Other methods could have included immunotherapy with imiquimod, antitumor creams (eg, 5-fluorouracil), or even radiation therapy. Her lesion was small and well-defined enough that Mohs surgery was not indicated—though some might disagree with that assessment.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Like all basal cell carcinomas (BCCs), ulcerative BCC—the most common type—is caused by overexposure to the sun.

- BCCs are often mistaken for infection or other sore, which delays the diagnosis.

- Nonhealing lesions should be considered cancerous until proven otherwise.

- Though this diagnosis was fairly obvious, biopsy is necessary to rule out other items in the differential—some of which (ie, Merkel cell carcinoma, melanoma) are potentially fatal.

For several years, a 60-year-old woman has had a nonhealing, asymptomatic “sore” on her upper right cheek. The lesion causes no pain or discomfort; it bothers her simply because it will not go away. It does occasionally bleed.

Several attempts at treatment—including antibiotic ointment, peroxide, and topical alcohol— have failed. A dermatologist once treated the lesion with cryotherapy; this initially reduced its size, but the effect didn’t last.

The patient admits to “worshipping the sun” as a youngster, tanning at every opportunity. Several family members, including her sister and mother, have had skin cancer.

EXAMINATION

A 6.5-mm, round, red nodule is located on the mid-upper right cheek, below the eye. On closer inspection, it appears glassy and translucent, with several obvious telangiectasias. It is surprisingly firm on palpation, though not at all tender to touch.

Elsewhere, the patient’s fair skin has abundant evidence of sun damage, including wrinkles, discoloration, and focal telangiectasias. No other lesions are seen. No nodes are palpable in her head or neck.

With the patient’s permission, and after discussion of the indications, procedure, alternatives, and risks, the lesion is removed by curettement. It is quite friable and shallow, allowing complete removal. The area is left to heal by secondary intention, and the specimen is submitted to pathology.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The pathology report confirmed the suspected diagnosis: noduloulcerative basal cell carcinoma (BCC). By far the most common type of skin cancer in the world, noduloulcerative BCCs are caused by overexposure to the sun.

As obvious as this diagnosis seemed to be, biopsy was warranted to confirm it and to rule out several other items in the differential. The latter include squamous cell carcinoma (which has far more harmful potential than BCC), sebaceous carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, and melanoma.

Not all BCCs are created equal—certain clinical and histologic characteristics predict a more aggressive course. While most BCCs require surgical excision, other treatment options do exist. In this patient’s case, the size and location of the lesion lent it to curettement and healing by secondary intention. Other methods could have included immunotherapy with imiquimod, antitumor creams (eg, 5-fluorouracil), or even radiation therapy. Her lesion was small and well-defined enough that Mohs surgery was not indicated—though some might disagree with that assessment.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Like all basal cell carcinomas (BCCs), ulcerative BCC—the most common type—is caused by overexposure to the sun.

- BCCs are often mistaken for infection or other sore, which delays the diagnosis.

- Nonhealing lesions should be considered cancerous until proven otherwise.

- Though this diagnosis was fairly obvious, biopsy is necessary to rule out other items in the differential—some of which (ie, Merkel cell carcinoma, melanoma) are potentially fatal.

Can You Treat These Feet?

ANSWER

The item that does not belong is tinea corporis (ringworm; choice “c”). There are several reasons this presumed, “obvious” diagnosis does not belong: First, there was no known source (human or animal) from which the patient could have contracted such an infection. Second, what should have been adequate treatment for a fungal infection had no effect. And finally, cutaneous fungal infections almost always disrupt the outer layer of skin; the relevant signs (eg, scaling, vesiculation, follicular granulomas) were absent in this case.

The correct diagnosis is granuloma annulare (GA; choice “a”), an extremely common, benign condition that is often misdiagnosed and treated as fungal infection. Histologically, GA is characterized by palisading (row-like) collections of cells that group together to form granulomas.

Similar patterns can be seen with sarcoidosis (choice “b”) and cutaneous mycobacterial infection (choice “d”), but additional distinguishing histologic features must be sought to confirm those diagnoses.

DISCUSSION

Virtually every medical provider has fallen for this clinical canard, referring an alleged “fungal infection” to dermatology when it fails to respond to treatment. This case was archetypical of GA, a condition most commonly found on the feet of young women.

It manifests on the extensor surfaces of the extremities as brownish red, round-to-oval, intradermal plaques devoid of surface disruption. The borders of the lesions are often raised enough to produce an apparent valley (delling) in the center.

There is a rather wide spectrum of GA variants (eg, generalized, su

Many treatments have been used (including topical or intralesional steroids and liquid nitrogen), but none are particularly effective. Fortunately, most cases eventually clear on their own and do not involve associated morbidity.

ANSWER

The item that does not belong is tinea corporis (ringworm; choice “c”). There are several reasons this presumed, “obvious” diagnosis does not belong: First, there was no known source (human or animal) from which the patient could have contracted such an infection. Second, what should have been adequate treatment for a fungal infection had no effect. And finally, cutaneous fungal infections almost always disrupt the outer layer of skin; the relevant signs (eg, scaling, vesiculation, follicular granulomas) were absent in this case.

The correct diagnosis is granuloma annulare (GA; choice “a”), an extremely common, benign condition that is often misdiagnosed and treated as fungal infection. Histologically, GA is characterized by palisading (row-like) collections of cells that group together to form granulomas.

Similar patterns can be seen with sarcoidosis (choice “b”) and cutaneous mycobacterial infection (choice “d”), but additional distinguishing histologic features must be sought to confirm those diagnoses.

DISCUSSION

Virtually every medical provider has fallen for this clinical canard, referring an alleged “fungal infection” to dermatology when it fails to respond to treatment. This case was archetypical of GA, a condition most commonly found on the feet of young women.

It manifests on the extensor surfaces of the extremities as brownish red, round-to-oval, intradermal plaques devoid of surface disruption. The borders of the lesions are often raised enough to produce an apparent valley (delling) in the center.

There is a rather wide spectrum of GA variants (eg, generalized, su

Many treatments have been used (including topical or intralesional steroids and liquid nitrogen), but none are particularly effective. Fortunately, most cases eventually clear on their own and do not involve associated morbidity.

ANSWER

The item that does not belong is tinea corporis (ringworm; choice “c”). There are several reasons this presumed, “obvious” diagnosis does not belong: First, there was no known source (human or animal) from which the patient could have contracted such an infection. Second, what should have been adequate treatment for a fungal infection had no effect. And finally, cutaneous fungal infections almost always disrupt the outer layer of skin; the relevant signs (eg, scaling, vesiculation, follicular granulomas) were absent in this case.

The correct diagnosis is granuloma annulare (GA; choice “a”), an extremely common, benign condition that is often misdiagnosed and treated as fungal infection. Histologically, GA is characterized by palisading (row-like) collections of cells that group together to form granulomas.

Similar patterns can be seen with sarcoidosis (choice “b”) and cutaneous mycobacterial infection (choice “d”), but additional distinguishing histologic features must be sought to confirm those diagnoses.

DISCUSSION

Virtually every medical provider has fallen for this clinical canard, referring an alleged “fungal infection” to dermatology when it fails to respond to treatment. This case was archetypical of GA, a condition most commonly found on the feet of young women.

It manifests on the extensor surfaces of the extremities as brownish red, round-to-oval, intradermal plaques devoid of surface disruption. The borders of the lesions are often raised enough to produce an apparent valley (delling) in the center.

There is a rather wide spectrum of GA variants (eg, generalized, su

Many treatments have been used (including topical or intralesional steroids and liquid nitrogen), but none are particularly effective. Fortunately, most cases eventually clear on their own and do not involve associated morbidity.

Two years ago, asymptomatic lesions appeared on this 17-year-old girl’s left foot. Diagnosed as “ringworm” by primary care, the spots have not responded to topical econazole or oral terbinafine and have instead grown and darkened.

Five intradermal plaques are found on the dorsal aspect of the patient’s left foot. Round and reddish brown, they measure 3 to 4 cm each. There is modest induration on palpation, but no increased warmth or tenderness. None of the lesions have an epidermal component (ie, scaling, vesiculation); in short, there is nothing to scrape for KOH examination.

The patient has no lesions elsewhere and denies any other health problems. Her mother, who is present, is certain that no one else in the family has had similar lesions. There are no pets in the house.

It's A Slow Grow

For more than two years, this 40-year-old African-American woman has had a lesion on her left maxilla. While it does not cause pain or discomfort, its presence is alarming to the patient. The lesion has grown steadily without responding to various topical OTC medications (tolnaftate, clotrimazole, miconazole, 1% hydrocortisone cream), oral anti-yeast medication, and antibiotics (fluconazole, erythromycin).

The patient claims to be in excellent health otherwise. She reports a strong family history of autoimmune disease, including rheumatoid arthritis and lupus.

EXAMINATION

There is an oval, scaly, atrophic patch on the upper left maxilla, just below the left nostril. The lesion measures 1.2 cm, has well-defined margins, and appears darker than the patient’s type V skin.

No redness or edema are seen, and no nodes are palpable in the area. Examination of the adjacent oral mucosal surface shows nothing amiss.

Under sterile conditions, and after local anesthesia (1% lidocaine with epinephrine) is administered, a 3-mm punch biopsy is obtained from the center of the lesion. The defect is closed with two interrupted nylon sutures.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The results showed follicular hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, acanthosis with basal-layer degeneration, periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrate, and increased mucin in the dermis. These findings—along with the clinical picture and family history—are consistent with discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE).

This manifestation of an autoimmune process is especially common in younger women of color. DLE primarily affects sun-exposed areas (eg, face, ears, neck) and involves scaly, round-to-oval patches and plaques with atrophic centers and follicular accentuation.

These lesions are frequently misdiagnosed as “fungal.” The differential also includes lichen planus and Jessner lymphocytic infiltrate.

Of the three types of cutaneous lupus erythematosus (discoid, acute, subacute), DLE is the most common. The acute form is defined by a “butterfly rash” across the face, while the subacute form involves multiple round-to-oval scaly lesions in wide photodistribution.

The chronic cutaneous lupus category includes DLE, tumid (characterized by deep, painful, indurated nodules), and panniculitis, which affects large areas of adipose tissue. DLE is, once again, the most common.

DLE can be an entity unto itself or part of a larger diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). The good news: Only about 15% of patients with DLE progress to SLE. It is debatable whether patients with DLE need a full workup for SLE, since corroborative findings are rarely found.

Emphasis is placed on effective treatment of DLE, which includes the use of class 3 or 4 topical steroids and oral antimalarials (eg, hydroxychloroquine). Even with treatment, DLE can take weeks or months to resolve and often leaves permanent scarring. Ongoing sun protection is necessary to prevent recurrence.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) is a common form of chronic cutaneous lupus, which has an autoimmune origin but is triggered by sun exposure.

- DLE typically presents with scaly round-to-oval patches and plaques with atrophic centers and follicular accentuation, often on sun-exposed areas.

- Women of color are at increased risk for lupus, and biopsy is often needed to confirm the diagnosis.

- Only about 15% of DLE patients ever progress to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), but DLE can be part of a larger SLE diagnosis.

- Treatment includes topical steroids and oral antimalarials (eg, hydroxychloroquine)—and sun protection is crucial.

For more than two years, this 40-year-old African-American woman has had a lesion on her left maxilla. While it does not cause pain or discomfort, its presence is alarming to the patient. The lesion has grown steadily without responding to various topical OTC medications (tolnaftate, clotrimazole, miconazole, 1% hydrocortisone cream), oral anti-yeast medication, and antibiotics (fluconazole, erythromycin).

The patient claims to be in excellent health otherwise. She reports a strong family history of autoimmune disease, including rheumatoid arthritis and lupus.

EXAMINATION

There is an oval, scaly, atrophic patch on the upper left maxilla, just below the left nostril. The lesion measures 1.2 cm, has well-defined margins, and appears darker than the patient’s type V skin.

No redness or edema are seen, and no nodes are palpable in the area. Examination of the adjacent oral mucosal surface shows nothing amiss.

Under sterile conditions, and after local anesthesia (1% lidocaine with epinephrine) is administered, a 3-mm punch biopsy is obtained from the center of the lesion. The defect is closed with two interrupted nylon sutures.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The results showed follicular hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, acanthosis with basal-layer degeneration, periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrate, and increased mucin in the dermis. These findings—along with the clinical picture and family history—are consistent with discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE).

This manifestation of an autoimmune process is especially common in younger women of color. DLE primarily affects sun-exposed areas (eg, face, ears, neck) and involves scaly, round-to-oval patches and plaques with atrophic centers and follicular accentuation.

These lesions are frequently misdiagnosed as “fungal.” The differential also includes lichen planus and Jessner lymphocytic infiltrate.

Of the three types of cutaneous lupus erythematosus (discoid, acute, subacute), DLE is the most common. The acute form is defined by a “butterfly rash” across the face, while the subacute form involves multiple round-to-oval scaly lesions in wide photodistribution.

The chronic cutaneous lupus category includes DLE, tumid (characterized by deep, painful, indurated nodules), and panniculitis, which affects large areas of adipose tissue. DLE is, once again, the most common.

DLE can be an entity unto itself or part of a larger diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). The good news: Only about 15% of patients with DLE progress to SLE. It is debatable whether patients with DLE need a full workup for SLE, since corroborative findings are rarely found.

Emphasis is placed on effective treatment of DLE, which includes the use of class 3 or 4 topical steroids and oral antimalarials (eg, hydroxychloroquine). Even with treatment, DLE can take weeks or months to resolve and often leaves permanent scarring. Ongoing sun protection is necessary to prevent recurrence.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) is a common form of chronic cutaneous lupus, which has an autoimmune origin but is triggered by sun exposure.

- DLE typically presents with scaly round-to-oval patches and plaques with atrophic centers and follicular accentuation, often on sun-exposed areas.

- Women of color are at increased risk for lupus, and biopsy is often needed to confirm the diagnosis.

- Only about 15% of DLE patients ever progress to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), but DLE can be part of a larger SLE diagnosis.

- Treatment includes topical steroids and oral antimalarials (eg, hydroxychloroquine)—and sun protection is crucial.

For more than two years, this 40-year-old African-American woman has had a lesion on her left maxilla. While it does not cause pain or discomfort, its presence is alarming to the patient. The lesion has grown steadily without responding to various topical OTC medications (tolnaftate, clotrimazole, miconazole, 1% hydrocortisone cream), oral anti-yeast medication, and antibiotics (fluconazole, erythromycin).

The patient claims to be in excellent health otherwise. She reports a strong family history of autoimmune disease, including rheumatoid arthritis and lupus.

EXAMINATION

There is an oval, scaly, atrophic patch on the upper left maxilla, just below the left nostril. The lesion measures 1.2 cm, has well-defined margins, and appears darker than the patient’s type V skin.

No redness or edema are seen, and no nodes are palpable in the area. Examination of the adjacent oral mucosal surface shows nothing amiss.

Under sterile conditions, and after local anesthesia (1% lidocaine with epinephrine) is administered, a 3-mm punch biopsy is obtained from the center of the lesion. The defect is closed with two interrupted nylon sutures.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The results showed follicular hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, acanthosis with basal-layer degeneration, periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrate, and increased mucin in the dermis. These findings—along with the clinical picture and family history—are consistent with discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE).

This manifestation of an autoimmune process is especially common in younger women of color. DLE primarily affects sun-exposed areas (eg, face, ears, neck) and involves scaly, round-to-oval patches and plaques with atrophic centers and follicular accentuation.

These lesions are frequently misdiagnosed as “fungal.” The differential also includes lichen planus and Jessner lymphocytic infiltrate.

Of the three types of cutaneous lupus erythematosus (discoid, acute, subacute), DLE is the most common. The acute form is defined by a “butterfly rash” across the face, while the subacute form involves multiple round-to-oval scaly lesions in wide photodistribution.

The chronic cutaneous lupus category includes DLE, tumid (characterized by deep, painful, indurated nodules), and panniculitis, which affects large areas of adipose tissue. DLE is, once again, the most common.

DLE can be an entity unto itself or part of a larger diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). The good news: Only about 15% of patients with DLE progress to SLE. It is debatable whether patients with DLE need a full workup for SLE, since corroborative findings are rarely found.

Emphasis is placed on effective treatment of DLE, which includes the use of class 3 or 4 topical steroids and oral antimalarials (eg, hydroxychloroquine). Even with treatment, DLE can take weeks or months to resolve and often leaves permanent scarring. Ongoing sun protection is necessary to prevent recurrence.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) is a common form of chronic cutaneous lupus, which has an autoimmune origin but is triggered by sun exposure.

- DLE typically presents with scaly round-to-oval patches and plaques with atrophic centers and follicular accentuation, often on sun-exposed areas.

- Women of color are at increased risk for lupus, and biopsy is often needed to confirm the diagnosis.

- Only about 15% of DLE patients ever progress to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), but DLE can be part of a larger SLE diagnosis.

- Treatment includes topical steroids and oral antimalarials (eg, hydroxychloroquine)—and sun protection is crucial.

Woman Gets Heated ... Literally

Recently, a 57-year-old woman was informed by her husband that she has a discolored area of skin on her back. This discovery followed a prolonged period of back pain, for which she was prescribed an NSAID. When this yielded no relief, she started sleeping with an electric heating pad, held in place by an elastic bandage, to ease the pain.

She reports mild itching in the affected area. She claims to be in good health otherwise and is not taking any medication.

EXAMINATION

The patient is in no acute distress but has obvious difficulty walking without pain. Covering her back, from the bra strap down, is modest erythema, a reticular pattern of modest hyperpigmentation, and focal areas of mild scaling.

No tenderness or increased warmth is detected on palpation. No notable changes are seen elsewhere on her skin.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This condition, termed erythema ab igne (EAI), was first described in 18th century women who worked while seated in front of a fire all day—hence the name, which translates to “redness from fire.” Over time, this exposure produced permanent changes on the anterior portions of their legs—similar to those seen in this patient.

Today, the condition can develop in a variety of contexts, all of which involve prolonged, repeated exposure to infrared radiation (eg, electric blankets, hot water bottles, electric space heaters, laptop computers). EAI can also affect the faces and arms of bakers, chefs, welders, and silversmiths working in close proximity to radiation.

This type of heat increases vasodilation in the superficial venous plexus (located in the papillary dermis), which causes hemosiderin to leak into the superficial dermis over time. This permanently stains the skin with a characteristic reticular pattern that mimics the affected vascular pattern. Generally, the darker the patient’s skin, the darker the pattern appears.

EAI more commonly affects women than men, and its diagnosis should prompt further investigation for underlying conditions. Musculoskeletal problems, chronic infection, anemia, or hypothyroidism could be involved.

Treatment, besides avoidance of radiation, includes topical application of retinoids or use of lasers.

In this case, the changes were discovered early enough to be at least partially reversible. In more advanced cases, focal areas of scaling can coalesce into papules or nodules that can undergo malignant transformation to squamous cell carcinoma.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Erythema ab igne (EAI) is a fairly common condition caused by close proximity to infrared radiation (eg, heating pads, laptop computers, electric space heaters).

- This radiation causes chronic vasodilatation of the superficial venous plexus, which leads to leakage of hemosiderin pigment, permanently staining the skin in a reticular pattern.

- EAI can affect the faces and arms of bakers, welders, chefs, and silversmiths.

- Treatment can be attempted with topical application of retinoids or with use of lasers.

Recently, a 57-year-old woman was informed by her husband that she has a discolored area of skin on her back. This discovery followed a prolonged period of back pain, for which she was prescribed an NSAID. When this yielded no relief, she started sleeping with an electric heating pad, held in place by an elastic bandage, to ease the pain.

She reports mild itching in the affected area. She claims to be in good health otherwise and is not taking any medication.

EXAMINATION

The patient is in no acute distress but has obvious difficulty walking without pain. Covering her back, from the bra strap down, is modest erythema, a reticular pattern of modest hyperpigmentation, and focal areas of mild scaling.

No tenderness or increased warmth is detected on palpation. No notable changes are seen elsewhere on her skin.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This condition, termed erythema ab igne (EAI), was first described in 18th century women who worked while seated in front of a fire all day—hence the name, which translates to “redness from fire.” Over time, this exposure produced permanent changes on the anterior portions of their legs—similar to those seen in this patient.

Today, the condition can develop in a variety of contexts, all of which involve prolonged, repeated exposure to infrared radiation (eg, electric blankets, hot water bottles, electric space heaters, laptop computers). EAI can also affect the faces and arms of bakers, chefs, welders, and silversmiths working in close proximity to radiation.

This type of heat increases vasodilation in the superficial venous plexus (located in the papillary dermis), which causes hemosiderin to leak into the superficial dermis over time. This permanently stains the skin with a characteristic reticular pattern that mimics the affected vascular pattern. Generally, the darker the patient’s skin, the darker the pattern appears.

EAI more commonly affects women than men, and its diagnosis should prompt further investigation for underlying conditions. Musculoskeletal problems, chronic infection, anemia, or hypothyroidism could be involved.

Treatment, besides avoidance of radiation, includes topical application of retinoids or use of lasers.

In this case, the changes were discovered early enough to be at least partially reversible. In more advanced cases, focal areas of scaling can coalesce into papules or nodules that can undergo malignant transformation to squamous cell carcinoma.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Erythema ab igne (EAI) is a fairly common condition caused by close proximity to infrared radiation (eg, heating pads, laptop computers, electric space heaters).

- This radiation causes chronic vasodilatation of the superficial venous plexus, which leads to leakage of hemosiderin pigment, permanently staining the skin in a reticular pattern.

- EAI can affect the faces and arms of bakers, welders, chefs, and silversmiths.

- Treatment can be attempted with topical application of retinoids or with use of lasers.

Recently, a 57-year-old woman was informed by her husband that she has a discolored area of skin on her back. This discovery followed a prolonged period of back pain, for which she was prescribed an NSAID. When this yielded no relief, she started sleeping with an electric heating pad, held in place by an elastic bandage, to ease the pain.

She reports mild itching in the affected area. She claims to be in good health otherwise and is not taking any medication.

EXAMINATION

The patient is in no acute distress but has obvious difficulty walking without pain. Covering her back, from the bra strap down, is modest erythema, a reticular pattern of modest hyperpigmentation, and focal areas of mild scaling.

No tenderness or increased warmth is detected on palpation. No notable changes are seen elsewhere on her skin.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This condition, termed erythema ab igne (EAI), was first described in 18th century women who worked while seated in front of a fire all day—hence the name, which translates to “redness from fire.” Over time, this exposure produced permanent changes on the anterior portions of their legs—similar to those seen in this patient.

Today, the condition can develop in a variety of contexts, all of which involve prolonged, repeated exposure to infrared radiation (eg, electric blankets, hot water bottles, electric space heaters, laptop computers). EAI can also affect the faces and arms of bakers, chefs, welders, and silversmiths working in close proximity to radiation.

This type of heat increases vasodilation in the superficial venous plexus (located in the papillary dermis), which causes hemosiderin to leak into the superficial dermis over time. This permanently stains the skin with a characteristic reticular pattern that mimics the affected vascular pattern. Generally, the darker the patient’s skin, the darker the pattern appears.

EAI more commonly affects women than men, and its diagnosis should prompt further investigation for underlying conditions. Musculoskeletal problems, chronic infection, anemia, or hypothyroidism could be involved.

Treatment, besides avoidance of radiation, includes topical application of retinoids or use of lasers.

In this case, the changes were discovered early enough to be at least partially reversible. In more advanced cases, focal areas of scaling can coalesce into papules or nodules that can undergo malignant transformation to squamous cell carcinoma.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Erythema ab igne (EAI) is a fairly common condition caused by close proximity to infrared radiation (eg, heating pads, laptop computers, electric space heaters).

- This radiation causes chronic vasodilatation of the superficial venous plexus, which leads to leakage of hemosiderin pigment, permanently staining the skin in a reticular pattern.

- EAI can affect the faces and arms of bakers, welders, chefs, and silversmiths.

- Treatment can be attempted with topical application of retinoids or with use of lasers.

Even Grandma Can’t Cure This

ANSWER

The correct answer is nummular eczema (NE; choice “c”).

Although fairly common, NE is not a well-known diagnostic entity. Its round shape and scaly surface are often misdiagnosed as fungal infection (choice “a”). But such an infection would have responded to the prescribed medication. In addition, there was no likely source (a new cat, dog, or ferret; participation in a contact sport, such as wrestling), making this diagnosis unlikely.

The scale of psoriasis (choice “b”) is typically white, tenacious, and much thicker than that seen in this case. Other signs would have been visible on the knees, elbows, scalp, or nails.

Impetigo (choice “d”), a superficial skin infection caused by staph and/or strep, first requires a break in the skin to gain entry (eg, picked-over acne, scratches). It manifests with a honey-colored crust on a red base, which were missing in this case.

DISCUSSION

NE is fairly common (seen in every 1 per 1,000 dermatology visits) and can be found on the arms as well as the legs. Predisposing factors include atopy and dry skin—but truth be told, there are many aspects of this condition that remain unexplained. While histopathologic studies can confirm the diagnosis, they offer little explanation of its origin.

What we do know: NE usually begins with a tiny papule, then a surrounding scaly rash develops as the papule disappears. The lesions, which can appear in multiples, are benign and will eventually clear on their own. This is fortunate, because NE can be very difficult to treat.

In this case, the standard regimen was prescribed: a class I topical steroid (clobetasol) to be used under occlusion. For prevention, patients should avoid scented, colored products; long, hot showers (or hot tubs); and heavy moisturizers.

But the bigger take-home message is that not all round, scaly lesions are of fungal origin. The differential includes several items—NE among them.

ANSWER

The correct answer is nummular eczema (NE; choice “c”).

Although fairly common, NE is not a well-known diagnostic entity. Its round shape and scaly surface are often misdiagnosed as fungal infection (choice “a”). But such an infection would have responded to the prescribed medication. In addition, there was no likely source (a new cat, dog, or ferret; participation in a contact sport, such as wrestling), making this diagnosis unlikely.

The scale of psoriasis (choice “b”) is typically white, tenacious, and much thicker than that seen in this case. Other signs would have been visible on the knees, elbows, scalp, or nails.

Impetigo (choice “d”), a superficial skin infection caused by staph and/or strep, first requires a break in the skin to gain entry (eg, picked-over acne, scratches). It manifests with a honey-colored crust on a red base, which were missing in this case.

DISCUSSION

NE is fairly common (seen in every 1 per 1,000 dermatology visits) and can be found on the arms as well as the legs. Predisposing factors include atopy and dry skin—but truth be told, there are many aspects of this condition that remain unexplained. While histopathologic studies can confirm the diagnosis, they offer little explanation of its origin.

What we do know: NE usually begins with a tiny papule, then a surrounding scaly rash develops as the papule disappears. The lesions, which can appear in multiples, are benign and will eventually clear on their own. This is fortunate, because NE can be very difficult to treat.

In this case, the standard regimen was prescribed: a class I topical steroid (clobetasol) to be used under occlusion. For prevention, patients should avoid scented, colored products; long, hot showers (or hot tubs); and heavy moisturizers.

But the bigger take-home message is that not all round, scaly lesions are of fungal origin. The differential includes several items—NE among them.

ANSWER

The correct answer is nummular eczema (NE; choice “c”).

Although fairly common, NE is not a well-known diagnostic entity. Its round shape and scaly surface are often misdiagnosed as fungal infection (choice “a”). But such an infection would have responded to the prescribed medication. In addition, there was no likely source (a new cat, dog, or ferret; participation in a contact sport, such as wrestling), making this diagnosis unlikely.

The scale of psoriasis (choice “b”) is typically white, tenacious, and much thicker than that seen in this case. Other signs would have been visible on the knees, elbows, scalp, or nails.

Impetigo (choice “d”), a superficial skin infection caused by staph and/or strep, first requires a break in the skin to gain entry (eg, picked-over acne, scratches). It manifests with a honey-colored crust on a red base, which were missing in this case.

DISCUSSION

NE is fairly common (seen in every 1 per 1,000 dermatology visits) and can be found on the arms as well as the legs. Predisposing factors include atopy and dry skin—but truth be told, there are many aspects of this condition that remain unexplained. While histopathologic studies can confirm the diagnosis, they offer little explanation of its origin.

What we do know: NE usually begins with a tiny papule, then a surrounding scaly rash develops as the papule disappears. The lesions, which can appear in multiples, are benign and will eventually clear on their own. This is fortunate, because NE can be very difficult to treat.

In this case, the standard regimen was prescribed: a class I topical steroid (clobetasol) to be used under occlusion. For prevention, patients should avoid scented, colored products; long, hot showers (or hot tubs); and heavy moisturizers.

But the bigger take-home message is that not all round, scaly lesions are of fungal origin. The differential includes several items—NE among them.

For several weeks, a 16-year-old girl has had an itchy rash on her calf. Her primary care provider, believing it to be fungal, prescribed nystatin cream and oral terbinafine (250 mg/d for a month). This treatment regimen had no effect.

In desperation, her grandmother mixed together a “family recipe” of peroxide, manteca (lard), and alcohol. This concoction was applied to the rash for several days—but alas, even this secret formula failed to bring improvement.

The patient has an extensive history of atopy, including eczema and seasonal allergies. The family has one small dog that stays indoors; there are no new pets in the household.

On the patient’s left medial calf is a round, well-defined, 4-cm patch of scaly skin. The lesion is brownish pink, consistent with her type IV skin. Closer inspection suggests the surface was initially covered with tiny blisters (vesicles); additional questioning confirms this.

Elsewhere, her skin is quite dry. No changes are seen on her knees, elbows, or scalp.

Together Since Birth

A 51-year-old Hispanic man presents for evaluation of a lesion he was born with. It grew as he did and was never more than a cosmetic problem until recently, when it became enlarged and sensitive. His family members convinced him to have it evaluated by primary care, who referred him to dermatology.

The patient denies any health problems other than type 2 diabetes, which is adequately controlled. His dark skin almost always tans, rather than burns, with sun exposure.

EXAMINATION

The lesion is hard to miss, measuring 1.8 cm x 5.5 mm and located prominently in the upper left nasolabial fold. It is quite firm, brownish red, hair-bearing, and round, with fine mammilations on the surface. It sits on a base only slightly smaller than the lesion’s surface. The rest of the patient’s skin is unremarkable.

Given that the lesion has changed and is quite sizeable, it is excised with a curving elliptiform incision along relaxed skin tension lines, paralleling the nasolabial fold, and sent for pathologic examination.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The pathology report confirmed the benign nature of this congenital melanocytic nevus (CMN). CMNs are hamartomatous lesions that form when collections of melanocytes (normal pigment cells) congregate in one location. These cells migrate during the embryonal stage of development—but some never make it to their final destination.

While CMNs are almost always benign, the history of change in this case made excision compelling. Given the lesion’s likely extension well under the surface of the skin, a shave removal would not suffice—and would leave a noticeable scar.

Despite their low potential for malignancy, CMNs—like any lesion removed from the body—must be sent for pathologic examination. The general rule is: the larger the congenital lesion, the greater the malignant potential.

Remember, too, that not all skin cancers are melanomas. Virtually any cell in the skin (sweat glands, neural tissue, sebaceous glands, smooth muscle, and even hair follicles) can undergo malignant transformation, so microscopic examination is mandatory for all removed lesions, except tiny tags or warts.

Interestingly, CMNs are more common on patients with lighter skin. However, besides the case patient, there were also several family members reporting a history of similar lesions. They were all thrilled with the patient’s cosmetic outcome—and more so with the benign report.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMNs) are collections of melanocytes in one area.

- CMNs have little malignant potential, but morphology (eg, color, shape, symptoms) or size may dictate the need for removal or biopsy.

- Deep shave or excision are the best options for removal; patient age, lesion location, potential for scarring, and surgical ability of the provider influence choice.

- Since melanocytes can end up in other extracutaneous locations, primary melanomas can develop almost anywhere—including the lungs, the gut, or even the eyes.

A 51-year-old Hispanic man presents for evaluation of a lesion he was born with. It grew as he did and was never more than a cosmetic problem until recently, when it became enlarged and sensitive. His family members convinced him to have it evaluated by primary care, who referred him to dermatology.

The patient denies any health problems other than type 2 diabetes, which is adequately controlled. His dark skin almost always tans, rather than burns, with sun exposure.

EXAMINATION

The lesion is hard to miss, measuring 1.8 cm x 5.5 mm and located prominently in the upper left nasolabial fold. It is quite firm, brownish red, hair-bearing, and round, with fine mammilations on the surface. It sits on a base only slightly smaller than the lesion’s surface. The rest of the patient’s skin is unremarkable.

Given that the lesion has changed and is quite sizeable, it is excised with a curving elliptiform incision along relaxed skin tension lines, paralleling the nasolabial fold, and sent for pathologic examination.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The pathology report confirmed the benign nature of this congenital melanocytic nevus (CMN). CMNs are hamartomatous lesions that form when collections of melanocytes (normal pigment cells) congregate in one location. These cells migrate during the embryonal stage of development—but some never make it to their final destination.

While CMNs are almost always benign, the history of change in this case made excision compelling. Given the lesion’s likely extension well under the surface of the skin, a shave removal would not suffice—and would leave a noticeable scar.

Despite their low potential for malignancy, CMNs—like any lesion removed from the body—must be sent for pathologic examination. The general rule is: the larger the congenital lesion, the greater the malignant potential.

Remember, too, that not all skin cancers are melanomas. Virtually any cell in the skin (sweat glands, neural tissue, sebaceous glands, smooth muscle, and even hair follicles) can undergo malignant transformation, so microscopic examination is mandatory for all removed lesions, except tiny tags or warts.

Interestingly, CMNs are more common on patients with lighter skin. However, besides the case patient, there were also several family members reporting a history of similar lesions. They were all thrilled with the patient’s cosmetic outcome—and more so with the benign report.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMNs) are collections of melanocytes in one area.

- CMNs have little malignant potential, but morphology (eg, color, shape, symptoms) or size may dictate the need for removal or biopsy.

- Deep shave or excision are the best options for removal; patient age, lesion location, potential for scarring, and surgical ability of the provider influence choice.

- Since melanocytes can end up in other extracutaneous locations, primary melanomas can develop almost anywhere—including the lungs, the gut, or even the eyes.

A 51-year-old Hispanic man presents for evaluation of a lesion he was born with. It grew as he did and was never more than a cosmetic problem until recently, when it became enlarged and sensitive. His family members convinced him to have it evaluated by primary care, who referred him to dermatology.

The patient denies any health problems other than type 2 diabetes, which is adequately controlled. His dark skin almost always tans, rather than burns, with sun exposure.

EXAMINATION

The lesion is hard to miss, measuring 1.8 cm x 5.5 mm and located prominently in the upper left nasolabial fold. It is quite firm, brownish red, hair-bearing, and round, with fine mammilations on the surface. It sits on a base only slightly smaller than the lesion’s surface. The rest of the patient’s skin is unremarkable.

Given that the lesion has changed and is quite sizeable, it is excised with a curving elliptiform incision along relaxed skin tension lines, paralleling the nasolabial fold, and sent for pathologic examination.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The pathology report confirmed the benign nature of this congenital melanocytic nevus (CMN). CMNs are hamartomatous lesions that form when collections of melanocytes (normal pigment cells) congregate in one location. These cells migrate during the embryonal stage of development—but some never make it to their final destination.

While CMNs are almost always benign, the history of change in this case made excision compelling. Given the lesion’s likely extension well under the surface of the skin, a shave removal would not suffice—and would leave a noticeable scar.

Despite their low potential for malignancy, CMNs—like any lesion removed from the body—must be sent for pathologic examination. The general rule is: the larger the congenital lesion, the greater the malignant potential.

Remember, too, that not all skin cancers are melanomas. Virtually any cell in the skin (sweat glands, neural tissue, sebaceous glands, smooth muscle, and even hair follicles) can undergo malignant transformation, so microscopic examination is mandatory for all removed lesions, except tiny tags or warts.

Interestingly, CMNs are more common on patients with lighter skin. However, besides the case patient, there were also several family members reporting a history of similar lesions. They were all thrilled with the patient’s cosmetic outcome—and more so with the benign report.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMNs) are collections of melanocytes in one area.

- CMNs have little malignant potential, but morphology (eg, color, shape, symptoms) or size may dictate the need for removal or biopsy.

- Deep shave or excision are the best options for removal; patient age, lesion location, potential for scarring, and surgical ability of the provider influence choice.

- Since melanocytes can end up in other extracutaneous locations, primary melanomas can develop almost anywhere—including the lungs, the gut, or even the eyes.

Scratching the Surface of the Problem

ANSWER

The least likely diagnosis is staph infection (choice “b”). By their very nature, staph infections are suppurative, often involving redness, swelling, pain, and purulent drainage. They can be chronic (eg, MRSA) but are more typically of acute onset. And they usually resolve on their own or with treatment; recall that this patient was treated for staph infection many times without any change.

She was also treated repeatedly for scabies (choice “a”), a condition that could certainly last 15 years. However, the lack of improvement with treatment, combined with the absence of suggestive signs, make this diagnosis improbable.

Mycosis fungoides (MF; choice “c”) is a type of T-cell lymphoma that often develops with itching and plaque formation over the course of years. It was ultimately ruled out by the biopsy results (as were scabies and staph infection).

What the biopsy did show was epidermal thickening—a characteristic sign of prurigo nodularis (choice “d”).

DISCUSSION

Prurigo nodularis is a localized form of neurodermatitis caused by picking and scratching. As with the classic form, the more the patient scratches, the more the lesions itch and multiply. In this case, biopsy of the larger plaque showed hypertrophic scarring.

The patient’s skin-picking habit likely developed during (and perhaps because of) her methamphetamine use. Long-term exposure to the itch-scratch-itch cycle can make treatment problematic. In this case, a class 4 topical steroid cream was prescribed, along with injection of several larger lesions with 10 mg/mL triamcinolone suspension.

It’s worth mentioning that for patients with this type of history, general lab testing (ie, complete blood count and complete metabolic panel) should be performed to rule out organic disease and other serious conditions (eg, renal or hepatic failure, leukemia). Fortunately, this patient’s results were reassuring on that front.

ANSWER

The least likely diagnosis is staph infection (choice “b”). By their very nature, staph infections are suppurative, often involving redness, swelling, pain, and purulent drainage. They can be chronic (eg, MRSA) but are more typically of acute onset. And they usually resolve on their own or with treatment; recall that this patient was treated for staph infection many times without any change.

She was also treated repeatedly for scabies (choice “a”), a condition that could certainly last 15 years. However, the lack of improvement with treatment, combined with the absence of suggestive signs, make this diagnosis improbable.

Mycosis fungoides (MF; choice “c”) is a type of T-cell lymphoma that often develops with itching and plaque formation over the course of years. It was ultimately ruled out by the biopsy results (as were scabies and staph infection).

What the biopsy did show was epidermal thickening—a characteristic sign of prurigo nodularis (choice “d”).

DISCUSSION

Prurigo nodularis is a localized form of neurodermatitis caused by picking and scratching. As with the classic form, the more the patient scratches, the more the lesions itch and multiply. In this case, biopsy of the larger plaque showed hypertrophic scarring.

The patient’s skin-picking habit likely developed during (and perhaps because of) her methamphetamine use. Long-term exposure to the itch-scratch-itch cycle can make treatment problematic. In this case, a class 4 topical steroid cream was prescribed, along with injection of several larger lesions with 10 mg/mL triamcinolone suspension.

It’s worth mentioning that for patients with this type of history, general lab testing (ie, complete blood count and complete metabolic panel) should be performed to rule out organic disease and other serious conditions (eg, renal or hepatic failure, leukemia). Fortunately, this patient’s results were reassuring on that front.

ANSWER

The least likely diagnosis is staph infection (choice “b”). By their very nature, staph infections are suppurative, often involving redness, swelling, pain, and purulent drainage. They can be chronic (eg, MRSA) but are more typically of acute onset. And they usually resolve on their own or with treatment; recall that this patient was treated for staph infection many times without any change.

She was also treated repeatedly for scabies (choice “a”), a condition that could certainly last 15 years. However, the lack of improvement with treatment, combined with the absence of suggestive signs, make this diagnosis improbable.

Mycosis fungoides (MF; choice “c”) is a type of T-cell lymphoma that often develops with itching and plaque formation over the course of years. It was ultimately ruled out by the biopsy results (as were scabies and staph infection).

What the biopsy did show was epidermal thickening—a characteristic sign of prurigo nodularis (choice “d”).

DISCUSSION

Prurigo nodularis is a localized form of neurodermatitis caused by picking and scratching. As with the classic form, the more the patient scratches, the more the lesions itch and multiply. In this case, biopsy of the larger plaque showed hypertrophic scarring.

The patient’s skin-picking habit likely developed during (and perhaps because of) her methamphetamine use. Long-term exposure to the itch-scratch-itch cycle can make treatment problematic. In this case, a class 4 topical steroid cream was prescribed, along with injection of several larger lesions with 10 mg/mL triamcinolone suspension.

It’s worth mentioning that for patients with this type of history, general lab testing (ie, complete blood count and complete metabolic panel) should be performed to rule out organic disease and other serious conditions (eg, renal or hepatic failure, leukemia). Fortunately, this patient’s results were reassuring on that front.

For at least 15 years, this 61-year-old African-American woman has had itchy lesions within arm’s reach. The patient says the problem manifested during a period in her life when she was addicted to several drugs, including methamphetamine. She complains bitterly about the itching and says it is difficult for her to leave the lesions alone.

No one else in her household is similarly affected. The patient has consulted a variety of health care providers, from primary care to dermatology and other specialties. She has received diagnoses of everything from scabies (for which she was treated, unsuccessfully) to pyoderma, bedbugs, and various forms of staph infection.

Examination reveals more than 100 lesions, mostly confined to her abdomen and lower chest, ranging from pinpoint to more than 3 cm. Many are excoriated, but most are purplish brown, oval plaques that somewhat match her type IV skin.

Her back, arms, and hands are spared. No lesions are seen between her fingers or on her volar wrists.

A biopsy is performed on two of the lesions—one small, the other larger.

The Lesion with Legs

No one in the family is certain when this 6-year-old boy first developed the red spot on his nose, but it is increasingly noticeable. And with school picture day approaching, they would like the redness to resolve.

Their primary care provider reassured them, at length, that it was benign and would eventually resolve without treatment. The lesion causes no symptoms and is purely a cosmetic concern.

The child is otherwise healthy and has been since birth.

EXAMINATION

A pinpoint red dot can be seen on the upper nasal bridge, just to the right of the midline. Tiny linear red “legs” extend from the central dot, like spokes on a wheel. In aggregate, the lesion measures about 3 mm in diameter. There is no palpable component.

However, the entire lesion is blanchable: Pinpoint pressure on the central dot causes it to blanch, and as the pressure is released, the legs of the lesion refill immediately from the center outward. When a glass slide is pressed against the lesion (a process called diascopy) and then released, the same process occurs.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Spider angiomas (SAs), originally called nevus araneus, are actually neither angiomas nor nevi. Instead, they are telangiectasias formed from a superficial arteriole whose surrounding sphincter muscle has failed. The “legs” are tiny veins that carry blood away from the central lesion; this is why they blanch so readily with central pressure and refill from the center outward.

SAs affect 10% to 15% of children and occur only in areas along the path of the superior vena cava. Besides the face, they can be found on the trunk, arms, and dorsal hands.

When solitary, these lesions are benign and can be either left to clear on their own or removed by laser or electrodessication. The presence of three or more lesions warrants further investigation, since multiple SAs can signify underlying disease (eg, cirrhosis of the liver, thyrotoxicosis, or systemic sclerosis).

This patient was not inclined to let us treat the lesion; within a few years, a teasing comment from a classmate or two may change his mind! But with a little luck, it will disappear on its own eventually.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Spider angiomas (SAs) are actually dilated telangiectatic arterioles manifesting as blanchable, bright red, pinpoint papules with venous “legs” that extend from the center.

- SAs affect 10% to 15% of all children and are confined to areas drained by the superior vena cava.

- Pressure on the lesion with a glass slide (a process called diascopy) causes total blanching; this, along with the clinical findings, confirms the diagnosis.

- Most SAs resolve on their own eventually, but they can be destroyed by laser or electrodessication.

- The presence of more than three SAs should prompt a search for potential causes, such as liver disease, thyrotoxicosis, or systemic sclerosis.

No one in the family is certain when this 6-year-old boy first developed the red spot on his nose, but it is increasingly noticeable. And with school picture day approaching, they would like the redness to resolve.

Their primary care provider reassured them, at length, that it was benign and would eventually resolve without treatment. The lesion causes no symptoms and is purely a cosmetic concern.

The child is otherwise healthy and has been since birth.

EXAMINATION

A pinpoint red dot can be seen on the upper nasal bridge, just to the right of the midline. Tiny linear red “legs” extend from the central dot, like spokes on a wheel. In aggregate, the lesion measures about 3 mm in diameter. There is no palpable component.

However, the entire lesion is blanchable: Pinpoint pressure on the central dot causes it to blanch, and as the pressure is released, the legs of the lesion refill immediately from the center outward. When a glass slide is pressed against the lesion (a process called diascopy) and then released, the same process occurs.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION