User login

Salpingectomy after vaginal hysterectomy: Technique, tips, and pearls

In this article, I describe my technique for a vaginal approach to right salpingectomy with ovarian preservation, as well as right salpingo-oophorectomy, in a patient lacking a left tube and ovary. This technique is fully illustrated on a cadaver in the Web-based master course in vaginal hysterectomy produced by the AAGL and co-sponsored by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons. That course is available online at https://www.aagl.org/vaghystwebinar.

For a detailed description of vaginal hysterectomy technique, see the article entitled “Vaginal hysterectomy using basic instrumentation,” by Barbara S. Levy, MD, which appeared in the October 2015 issue of OBG Management. Next month, in the December 2015 issue of the journal, I will detail my strategies for managing complications associated with vaginal hysterectomy, salpingectomy, and salpingo-oophorectomy.

Right salpingectomy

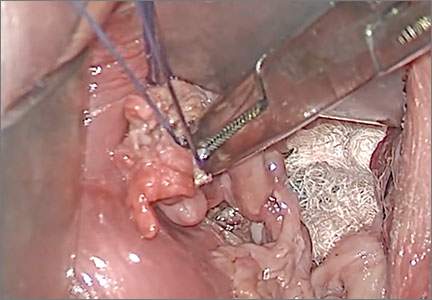

FIGURE 1 Locate the tube |

The fallopian tube will almost always be found on top of the ovary. |

FIGURE 2 Isolate the tube

|

| Grasp the tube and bring it to the midline. |

Start with light traction

Begin by placing an instrument on the round ligament, tube, and uterine-ovarian pedicle, exerting light traction. Note that the tube will always be found on top of the ovary

(FIGURE 1). Take care during placement of packing material to avoid sweeping the fimbriae of the tube up and out of the surgical field. You may need to play with the packing a bit until you are able to deliver the tube.

Once you identify the tube, isolate it by bringing it down to the midline (FIGURE 2). One thing to note if you’re accustomed to performing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy: The gonadal pedicle is fairly substantive and can sustain a bit of tugging. However, if you’re performing salpingectomy with ovarian preservation, you need to be much more careful in your handling of the tube because the mesosalpinx is extremely delicate.

After you bring the tube to the midline, grasp it using a Heaney or Shallcross clamp. You could use energy to take this pedicle or clamp and tie it.

Make sure that the packing material is out of the way and that you have most of the tube nicely isolated. Don’t take the tube too far up in the surgical field because, if you lose it, it can be hard to control the bleeding. Ensure that you have grasped the fimbriated end of the tube.

In some cases you can leave a portion of the tube right next to the round ligament (FIGURE 3). You can go back and take that portion later, if you desire. But when it comes to the potential for the fallopian tube to generate carcinoma, most of the concern involves the mid to distal end of the tube rather than the cornual portion.

Once the Shallcross clamp has a good purchase on the pedicle, bring the suture around the clamp and then pass it under the tube so that you encircle the mesosalpinx pedicle (FIGURE 4). It is extremely important during salpingectomy to tie this suture down gently but tightly. In the process, have your assistant flash the Shallcross clamp open when you tie the suture. Otherwise, the suture will tend to tear through the mesosalpinx. Be very careful in your handling of the specimen at this point. Next, cut right along the edge of the clamp to remove the tube.

FIGURE 3 Focus on the distal tube

| FIGURE 4 Clamp and tie the pedicle

| |

| The cornual portion of the tube (proximal to the round ligament) can be left behind, if desired. The propensity for cancer centers on the distal end of the tube. | Bring the suture around the clamp and then pass it under the tube so that you encircle the mesosalpinx pedicle. |

If you prefer, you can stick-tie the remaining portion again, but usually one tie will suffice because there is such a small pedicle there. The distal portion of the pedicle eventually will necrose close to the tie. The next step is ensuring hemostasis.

On occasion, if you lose the pedicle high in the surgical field, you can try to oversew it. A 2-0 Vicryl suture may be used to place a figure-eight stitch to control bleeding around the mesosalpinx. Alternatively, an energy device may be used for hemostasis. Rarely, if you encounter bleeding that does not respond to the previous suggestions, you may need to remove the ovary to control bleeding if the tissue tears.

Transvaginal technique for salpingo-oophorectomy

Once the hysterectomy is completed, grasp the round ligament, tube, and uterine-ovarian pedicle, placing slight tension on the pedicle, and free the right round ligament to ease isolation of the gonadal vessels. Using electrocautery, carefully transect the round ligament. It is critical when isolating the round ligament to transect only the ligament and not to get deep into the underlying tissue or bleeding will ensue. If you “hug” just the round ligament, you will open into the broad ligament and easily be able to isolate the gonadal pedicle.

Once the pedicle is nicely isolated, readjust your retractors or lighting to improve visualization. Now the gonadal vessels can be isolated up high much more easily (FIGURE 1).

Next, use a Heaney clamp to grab the pedicle, making sure that the ovary is medial to the clamp (FIGURE 2).

|

| |

| FIGURE 1: ISOLATE THE GONADAL VESSELS Once optimal visualization is achieved, the gonadal vessels can be isolated easily. | FIGURE 2: KEEP THE OVARY MEDIAL TO THE CLAMP Use a Heaney clamp to grab the pedicle, keeping the ovary medial to the clamp. |

In this setting, there are a number of techniques you can use to complete the salpingo-oophorectomy. I tend to doubly ligate the pedicle. To begin, cut the tagging suture to get it out of the way. Then place a free tie lateral to the clamp, bringing it down and underneath to fully encircle the pedicle. Ligate the pedicle then cut the free tie. Follow by cutting the pedicle beside the Heaney clamp and removing the specimen. Stick-tie the remaining pedicle.

Locate the free tie, which is easily identified. Place your needle between that free tie and the clamp so that you do not pierce the vessels proximal to the tie with that needle. Then doubly ligate the pedicle.

Check for hemostasis and, once confirmed, cut the pedicle tie. Because this patient does not have a left tube and ovary, the procedure is now completed.

Conclusion

The tubes are usually readily accessible for removal at the time of vaginal hysterectomy. There is evolving evidence that the tube may play a role in malignancy of the female genital tract. Thus, removal may be preventive. In addition, if there are paratubal cysts or hydrosalpinx from prior tubal ligation, it makes sense to remove the tube. There is little evidence to suggest that removal of the tubes accelerates the menopausal transition due to compromise of the blood supply to the ovaries.

You must be very gentle when handling and removing just the tubes. The mesosalpinx is delicate and easily torn or traumatized. A careful and deliberate approach is warranted.

Bilateral salpingectomy: Key take-aways

Locate the tube. The fallopian tube always lies on top of the ovary and should be found there. On occasion, the abdominal packing used to move the bowel out of the pelvis will “hide” the tube; readjusting this packing often solves the problem.

Be gentle with the mesosalpinx as it is very delicate and can easily avulse. It is very important to “flash the clamp” (open the clamp and then close it) as you free-tie the mesosalpinx to avoid cutting through the delicate pedicle.

Remove as much tube as possible. The fimbriae end of the tube usually is free and easy to identify. Try to remove as much of the tube as possible. Often, a bit of the proximal tube is left in the utero-ovarian pedicle tie.

Clean up. You will often find peritubal cysts or “tubal clips” from a sterilization procedure. I recommend that you remove any of these you encounter to avoid problems down the road. Often, these cysts and clip-like devices are removed as part of the specimen.

Dry up. Always confirm hemostasis before concluding the procedure. If there is bleeding, be sure to assess the mesosalpinx. Occasionally, the pedicle can be torn higher up, near the gonadal vessels. Investigate this region if bleeding seems to be an issue.

Transvaginal salpingo-oophorectomy: Key take-aways

Perfect a technique. There are many approaches to transvaginal removal of the adnexae; pick one and perfect it. The better you are, the fewer complications you will have. Recognize that a different approach (use of a stapler or energy sealing device, for example) may prove useful in some settings. Be surgically versatile and recognize situations that might call for something other than your usual approach.

Optimize visualization. The tubes and ovaries are usually very accessible vaginally. Use an abdominal pack to move the bowel out of the pelvis. Adequate retraction and use of a lighted retractor or suction irrigator will facilitate exposure.

Ligate the gonadal vessels. Retraction of the tube and ovary complex medially away from the pelvic sidewall will allow you to place a clamp (or stapler or energy device) lateral to secure the gonadal vessels and ensure complete removal of the adnexae.

Release the round ligament. Although this step is usually not required, it will allow you to isolate the adnexae more precisely, especially when dealing with an adnexal mass transvaginally. It is critical that you “hug” the round ligament and refrain from penetrating deeply into the underlying tissues, or bleeding will occur. Once the round ligament is released, the tube and ovary are isolated on the gonadal pedicle and can be completely excised with this technique.

Manage bleeding. If suturing, I prefer to doubly ligate the gonadal vessels. Once I clamp the pedicle, I “free-tie” the gonadal vessels with an initial suture. This suture secures the vascular pedicle and prevents retraction. The adnexae can then be removed, followed by placement of a “stick-tie” to re-ligate the pedicle. Although this vascular pedicle is more robust than the mesosalpinx, it, too, can be avulsed, so it is important to proceed with caution. I recommend having a long clamp (uterine packing forceps or MD Anderson clamp) available in your instrument pan to facilitate specific isolation of the gonadal vessels along the pelvic sidewall in the event avulsion does occur.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

In this article, I describe my technique for a vaginal approach to right salpingectomy with ovarian preservation, as well as right salpingo-oophorectomy, in a patient lacking a left tube and ovary. This technique is fully illustrated on a cadaver in the Web-based master course in vaginal hysterectomy produced by the AAGL and co-sponsored by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons. That course is available online at https://www.aagl.org/vaghystwebinar.

For a detailed description of vaginal hysterectomy technique, see the article entitled “Vaginal hysterectomy using basic instrumentation,” by Barbara S. Levy, MD, which appeared in the October 2015 issue of OBG Management. Next month, in the December 2015 issue of the journal, I will detail my strategies for managing complications associated with vaginal hysterectomy, salpingectomy, and salpingo-oophorectomy.

Right salpingectomy

FIGURE 1 Locate the tube |

The fallopian tube will almost always be found on top of the ovary. |

FIGURE 2 Isolate the tube

|

| Grasp the tube and bring it to the midline. |

Start with light traction

Begin by placing an instrument on the round ligament, tube, and uterine-ovarian pedicle, exerting light traction. Note that the tube will always be found on top of the ovary

(FIGURE 1). Take care during placement of packing material to avoid sweeping the fimbriae of the tube up and out of the surgical field. You may need to play with the packing a bit until you are able to deliver the tube.

Once you identify the tube, isolate it by bringing it down to the midline (FIGURE 2). One thing to note if you’re accustomed to performing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy: The gonadal pedicle is fairly substantive and can sustain a bit of tugging. However, if you’re performing salpingectomy with ovarian preservation, you need to be much more careful in your handling of the tube because the mesosalpinx is extremely delicate.

After you bring the tube to the midline, grasp it using a Heaney or Shallcross clamp. You could use energy to take this pedicle or clamp and tie it.

Make sure that the packing material is out of the way and that you have most of the tube nicely isolated. Don’t take the tube too far up in the surgical field because, if you lose it, it can be hard to control the bleeding. Ensure that you have grasped the fimbriated end of the tube.

In some cases you can leave a portion of the tube right next to the round ligament (FIGURE 3). You can go back and take that portion later, if you desire. But when it comes to the potential for the fallopian tube to generate carcinoma, most of the concern involves the mid to distal end of the tube rather than the cornual portion.

Once the Shallcross clamp has a good purchase on the pedicle, bring the suture around the clamp and then pass it under the tube so that you encircle the mesosalpinx pedicle (FIGURE 4). It is extremely important during salpingectomy to tie this suture down gently but tightly. In the process, have your assistant flash the Shallcross clamp open when you tie the suture. Otherwise, the suture will tend to tear through the mesosalpinx. Be very careful in your handling of the specimen at this point. Next, cut right along the edge of the clamp to remove the tube.

FIGURE 3 Focus on the distal tube

| FIGURE 4 Clamp and tie the pedicle

| |

| The cornual portion of the tube (proximal to the round ligament) can be left behind, if desired. The propensity for cancer centers on the distal end of the tube. | Bring the suture around the clamp and then pass it under the tube so that you encircle the mesosalpinx pedicle. |

If you prefer, you can stick-tie the remaining portion again, but usually one tie will suffice because there is such a small pedicle there. The distal portion of the pedicle eventually will necrose close to the tie. The next step is ensuring hemostasis.

On occasion, if you lose the pedicle high in the surgical field, you can try to oversew it. A 2-0 Vicryl suture may be used to place a figure-eight stitch to control bleeding around the mesosalpinx. Alternatively, an energy device may be used for hemostasis. Rarely, if you encounter bleeding that does not respond to the previous suggestions, you may need to remove the ovary to control bleeding if the tissue tears.

Transvaginal technique for salpingo-oophorectomy

Once the hysterectomy is completed, grasp the round ligament, tube, and uterine-ovarian pedicle, placing slight tension on the pedicle, and free the right round ligament to ease isolation of the gonadal vessels. Using electrocautery, carefully transect the round ligament. It is critical when isolating the round ligament to transect only the ligament and not to get deep into the underlying tissue or bleeding will ensue. If you “hug” just the round ligament, you will open into the broad ligament and easily be able to isolate the gonadal pedicle.

Once the pedicle is nicely isolated, readjust your retractors or lighting to improve visualization. Now the gonadal vessels can be isolated up high much more easily (FIGURE 1).

Next, use a Heaney clamp to grab the pedicle, making sure that the ovary is medial to the clamp (FIGURE 2).

|

| |

| FIGURE 1: ISOLATE THE GONADAL VESSELS Once optimal visualization is achieved, the gonadal vessels can be isolated easily. | FIGURE 2: KEEP THE OVARY MEDIAL TO THE CLAMP Use a Heaney clamp to grab the pedicle, keeping the ovary medial to the clamp. |

In this setting, there are a number of techniques you can use to complete the salpingo-oophorectomy. I tend to doubly ligate the pedicle. To begin, cut the tagging suture to get it out of the way. Then place a free tie lateral to the clamp, bringing it down and underneath to fully encircle the pedicle. Ligate the pedicle then cut the free tie. Follow by cutting the pedicle beside the Heaney clamp and removing the specimen. Stick-tie the remaining pedicle.

Locate the free tie, which is easily identified. Place your needle between that free tie and the clamp so that you do not pierce the vessels proximal to the tie with that needle. Then doubly ligate the pedicle.

Check for hemostasis and, once confirmed, cut the pedicle tie. Because this patient does not have a left tube and ovary, the procedure is now completed.

Conclusion

The tubes are usually readily accessible for removal at the time of vaginal hysterectomy. There is evolving evidence that the tube may play a role in malignancy of the female genital tract. Thus, removal may be preventive. In addition, if there are paratubal cysts or hydrosalpinx from prior tubal ligation, it makes sense to remove the tube. There is little evidence to suggest that removal of the tubes accelerates the menopausal transition due to compromise of the blood supply to the ovaries.

You must be very gentle when handling and removing just the tubes. The mesosalpinx is delicate and easily torn or traumatized. A careful and deliberate approach is warranted.

Bilateral salpingectomy: Key take-aways

Locate the tube. The fallopian tube always lies on top of the ovary and should be found there. On occasion, the abdominal packing used to move the bowel out of the pelvis will “hide” the tube; readjusting this packing often solves the problem.

Be gentle with the mesosalpinx as it is very delicate and can easily avulse. It is very important to “flash the clamp” (open the clamp and then close it) as you free-tie the mesosalpinx to avoid cutting through the delicate pedicle.

Remove as much tube as possible. The fimbriae end of the tube usually is free and easy to identify. Try to remove as much of the tube as possible. Often, a bit of the proximal tube is left in the utero-ovarian pedicle tie.

Clean up. You will often find peritubal cysts or “tubal clips” from a sterilization procedure. I recommend that you remove any of these you encounter to avoid problems down the road. Often, these cysts and clip-like devices are removed as part of the specimen.

Dry up. Always confirm hemostasis before concluding the procedure. If there is bleeding, be sure to assess the mesosalpinx. Occasionally, the pedicle can be torn higher up, near the gonadal vessels. Investigate this region if bleeding seems to be an issue.

Transvaginal salpingo-oophorectomy: Key take-aways

Perfect a technique. There are many approaches to transvaginal removal of the adnexae; pick one and perfect it. The better you are, the fewer complications you will have. Recognize that a different approach (use of a stapler or energy sealing device, for example) may prove useful in some settings. Be surgically versatile and recognize situations that might call for something other than your usual approach.

Optimize visualization. The tubes and ovaries are usually very accessible vaginally. Use an abdominal pack to move the bowel out of the pelvis. Adequate retraction and use of a lighted retractor or suction irrigator will facilitate exposure.

Ligate the gonadal vessels. Retraction of the tube and ovary complex medially away from the pelvic sidewall will allow you to place a clamp (or stapler or energy device) lateral to secure the gonadal vessels and ensure complete removal of the adnexae.

Release the round ligament. Although this step is usually not required, it will allow you to isolate the adnexae more precisely, especially when dealing with an adnexal mass transvaginally. It is critical that you “hug” the round ligament and refrain from penetrating deeply into the underlying tissues, or bleeding will occur. Once the round ligament is released, the tube and ovary are isolated on the gonadal pedicle and can be completely excised with this technique.

Manage bleeding. If suturing, I prefer to doubly ligate the gonadal vessels. Once I clamp the pedicle, I “free-tie” the gonadal vessels with an initial suture. This suture secures the vascular pedicle and prevents retraction. The adnexae can then be removed, followed by placement of a “stick-tie” to re-ligate the pedicle. Although this vascular pedicle is more robust than the mesosalpinx, it, too, can be avulsed, so it is important to proceed with caution. I recommend having a long clamp (uterine packing forceps or MD Anderson clamp) available in your instrument pan to facilitate specific isolation of the gonadal vessels along the pelvic sidewall in the event avulsion does occur.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

In this article, I describe my technique for a vaginal approach to right salpingectomy with ovarian preservation, as well as right salpingo-oophorectomy, in a patient lacking a left tube and ovary. This technique is fully illustrated on a cadaver in the Web-based master course in vaginal hysterectomy produced by the AAGL and co-sponsored by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons. That course is available online at https://www.aagl.org/vaghystwebinar.

For a detailed description of vaginal hysterectomy technique, see the article entitled “Vaginal hysterectomy using basic instrumentation,” by Barbara S. Levy, MD, which appeared in the October 2015 issue of OBG Management. Next month, in the December 2015 issue of the journal, I will detail my strategies for managing complications associated with vaginal hysterectomy, salpingectomy, and salpingo-oophorectomy.

Right salpingectomy

FIGURE 1 Locate the tube |

The fallopian tube will almost always be found on top of the ovary. |

FIGURE 2 Isolate the tube

|

| Grasp the tube and bring it to the midline. |

Start with light traction

Begin by placing an instrument on the round ligament, tube, and uterine-ovarian pedicle, exerting light traction. Note that the tube will always be found on top of the ovary

(FIGURE 1). Take care during placement of packing material to avoid sweeping the fimbriae of the tube up and out of the surgical field. You may need to play with the packing a bit until you are able to deliver the tube.

Once you identify the tube, isolate it by bringing it down to the midline (FIGURE 2). One thing to note if you’re accustomed to performing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy: The gonadal pedicle is fairly substantive and can sustain a bit of tugging. However, if you’re performing salpingectomy with ovarian preservation, you need to be much more careful in your handling of the tube because the mesosalpinx is extremely delicate.

After you bring the tube to the midline, grasp it using a Heaney or Shallcross clamp. You could use energy to take this pedicle or clamp and tie it.

Make sure that the packing material is out of the way and that you have most of the tube nicely isolated. Don’t take the tube too far up in the surgical field because, if you lose it, it can be hard to control the bleeding. Ensure that you have grasped the fimbriated end of the tube.

In some cases you can leave a portion of the tube right next to the round ligament (FIGURE 3). You can go back and take that portion later, if you desire. But when it comes to the potential for the fallopian tube to generate carcinoma, most of the concern involves the mid to distal end of the tube rather than the cornual portion.

Once the Shallcross clamp has a good purchase on the pedicle, bring the suture around the clamp and then pass it under the tube so that you encircle the mesosalpinx pedicle (FIGURE 4). It is extremely important during salpingectomy to tie this suture down gently but tightly. In the process, have your assistant flash the Shallcross clamp open when you tie the suture. Otherwise, the suture will tend to tear through the mesosalpinx. Be very careful in your handling of the specimen at this point. Next, cut right along the edge of the clamp to remove the tube.

FIGURE 3 Focus on the distal tube

| FIGURE 4 Clamp and tie the pedicle

| |

| The cornual portion of the tube (proximal to the round ligament) can be left behind, if desired. The propensity for cancer centers on the distal end of the tube. | Bring the suture around the clamp and then pass it under the tube so that you encircle the mesosalpinx pedicle. |

If you prefer, you can stick-tie the remaining portion again, but usually one tie will suffice because there is such a small pedicle there. The distal portion of the pedicle eventually will necrose close to the tie. The next step is ensuring hemostasis.

On occasion, if you lose the pedicle high in the surgical field, you can try to oversew it. A 2-0 Vicryl suture may be used to place a figure-eight stitch to control bleeding around the mesosalpinx. Alternatively, an energy device may be used for hemostasis. Rarely, if you encounter bleeding that does not respond to the previous suggestions, you may need to remove the ovary to control bleeding if the tissue tears.

Transvaginal technique for salpingo-oophorectomy

Once the hysterectomy is completed, grasp the round ligament, tube, and uterine-ovarian pedicle, placing slight tension on the pedicle, and free the right round ligament to ease isolation of the gonadal vessels. Using electrocautery, carefully transect the round ligament. It is critical when isolating the round ligament to transect only the ligament and not to get deep into the underlying tissue or bleeding will ensue. If you “hug” just the round ligament, you will open into the broad ligament and easily be able to isolate the gonadal pedicle.

Once the pedicle is nicely isolated, readjust your retractors or lighting to improve visualization. Now the gonadal vessels can be isolated up high much more easily (FIGURE 1).

Next, use a Heaney clamp to grab the pedicle, making sure that the ovary is medial to the clamp (FIGURE 2).

|

| |

| FIGURE 1: ISOLATE THE GONADAL VESSELS Once optimal visualization is achieved, the gonadal vessels can be isolated easily. | FIGURE 2: KEEP THE OVARY MEDIAL TO THE CLAMP Use a Heaney clamp to grab the pedicle, keeping the ovary medial to the clamp. |

In this setting, there are a number of techniques you can use to complete the salpingo-oophorectomy. I tend to doubly ligate the pedicle. To begin, cut the tagging suture to get it out of the way. Then place a free tie lateral to the clamp, bringing it down and underneath to fully encircle the pedicle. Ligate the pedicle then cut the free tie. Follow by cutting the pedicle beside the Heaney clamp and removing the specimen. Stick-tie the remaining pedicle.

Locate the free tie, which is easily identified. Place your needle between that free tie and the clamp so that you do not pierce the vessels proximal to the tie with that needle. Then doubly ligate the pedicle.

Check for hemostasis and, once confirmed, cut the pedicle tie. Because this patient does not have a left tube and ovary, the procedure is now completed.

Conclusion

The tubes are usually readily accessible for removal at the time of vaginal hysterectomy. There is evolving evidence that the tube may play a role in malignancy of the female genital tract. Thus, removal may be preventive. In addition, if there are paratubal cysts or hydrosalpinx from prior tubal ligation, it makes sense to remove the tube. There is little evidence to suggest that removal of the tubes accelerates the menopausal transition due to compromise of the blood supply to the ovaries.

You must be very gentle when handling and removing just the tubes. The mesosalpinx is delicate and easily torn or traumatized. A careful and deliberate approach is warranted.

Bilateral salpingectomy: Key take-aways

Locate the tube. The fallopian tube always lies on top of the ovary and should be found there. On occasion, the abdominal packing used to move the bowel out of the pelvis will “hide” the tube; readjusting this packing often solves the problem.

Be gentle with the mesosalpinx as it is very delicate and can easily avulse. It is very important to “flash the clamp” (open the clamp and then close it) as you free-tie the mesosalpinx to avoid cutting through the delicate pedicle.

Remove as much tube as possible. The fimbriae end of the tube usually is free and easy to identify. Try to remove as much of the tube as possible. Often, a bit of the proximal tube is left in the utero-ovarian pedicle tie.

Clean up. You will often find peritubal cysts or “tubal clips” from a sterilization procedure. I recommend that you remove any of these you encounter to avoid problems down the road. Often, these cysts and clip-like devices are removed as part of the specimen.

Dry up. Always confirm hemostasis before concluding the procedure. If there is bleeding, be sure to assess the mesosalpinx. Occasionally, the pedicle can be torn higher up, near the gonadal vessels. Investigate this region if bleeding seems to be an issue.

Transvaginal salpingo-oophorectomy: Key take-aways

Perfect a technique. There are many approaches to transvaginal removal of the adnexae; pick one and perfect it. The better you are, the fewer complications you will have. Recognize that a different approach (use of a stapler or energy sealing device, for example) may prove useful in some settings. Be surgically versatile and recognize situations that might call for something other than your usual approach.

Optimize visualization. The tubes and ovaries are usually very accessible vaginally. Use an abdominal pack to move the bowel out of the pelvis. Adequate retraction and use of a lighted retractor or suction irrigator will facilitate exposure.

Ligate the gonadal vessels. Retraction of the tube and ovary complex medially away from the pelvic sidewall will allow you to place a clamp (or stapler or energy device) lateral to secure the gonadal vessels and ensure complete removal of the adnexae.

Release the round ligament. Although this step is usually not required, it will allow you to isolate the adnexae more precisely, especially when dealing with an adnexal mass transvaginally. It is critical that you “hug” the round ligament and refrain from penetrating deeply into the underlying tissues, or bleeding will occur. Once the round ligament is released, the tube and ovary are isolated on the gonadal pedicle and can be completely excised with this technique.

Manage bleeding. If suturing, I prefer to doubly ligate the gonadal vessels. Once I clamp the pedicle, I “free-tie” the gonadal vessels with an initial suture. This suture secures the vascular pedicle and prevents retraction. The adnexae can then be removed, followed by placement of a “stick-tie” to re-ligate the pedicle. Although this vascular pedicle is more robust than the mesosalpinx, it, too, can be avulsed, so it is important to proceed with caution. I recommend having a long clamp (uterine packing forceps or MD Anderson clamp) available in your instrument pan to facilitate specific isolation of the gonadal vessels along the pelvic sidewall in the event avulsion does occur.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

In this Article

- Technique for salpingo-oophorectomy

- Salpingectomy: Key take-aways

- Pointers for salpingo- oophorectomy

When is her pelvic pressure and bulge due to Pouch of Douglas hernia?

CASE: Pelvic organ prolapse or Pouch of Douglas hernia?

A 42-year-old G3P2 woman is referred to you by her primary care provider for pelvic organ prolapse. Her medical history reveals that she has been bothered by a sense of pelvic pressure and bulge progressing over several years, and she has noticed that her symptoms are particularly worse during and after bowel movements. She reports some improved bowel evacuation with external splinting of her perineum. Upon closer questioning, the patient reports a history of chronic constipation since childhood associated with straining and a sense of incomplete emptying. She reports spending up to 30 minutes three to four times per day on the commode to completely empty her bowels.

Physical examination reveals an overweight woman with a soft, nontender abdomen remarkable for laparoscopic incision scars from a previous tubal ligation. Inspection of the external genitalia at rest is normal. Cough stress test is negative. At maximum Valsalva, however, there is significant perineal ballooning present.

Speculum examination demonstrates grade 1 uterine prolapse, grade 1 cystocele, and grade 2 rectocele. There is no evidence of pelvic floor tension myalgia. She has weak pelvic muscle strength. Visualization of the anus at maximum Valsalva reveals there is some asymmetric rectal prolapse of the anterior rectal wall. Digital rectal exam is unremarkable.

Are these patient’s symptoms due to pelvic organ prolapse or Pouch of Douglas hernia?

Pelvic organ prolapse: A common problem

Pelvic organ prolapse has an estimated prevalence of 55% in women aged 50 to 59 years.1 More than 200,000 pelvic organ prolapse surgeries are performed annually in the United States.2 Typically, patients report:

- vaginal bulge causing discomfort

- pelvic pressure or heaviness, or

- rubbing of the vaginal bulge on undergarments.

In more advanced pelvic organ prolapse, patients may report voiding dysfunction or stool trapping that requires manual splinting of the prolapse to assist in bladder and bowel evacuation.

Pouch of Douglas hernia: A lesser-known

(recognized) phenomenon

Similar to pelvic organ prolapse, Pouch of Douglas hernia also can present with symptoms of:

- pelvic pressure

- vague perineal aching

- defecatory dysfunction.

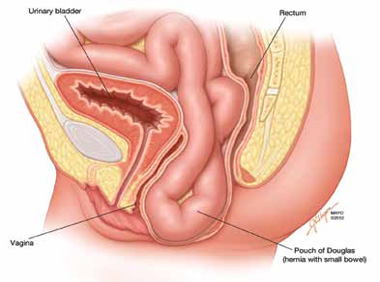

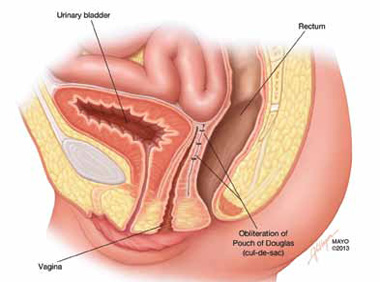

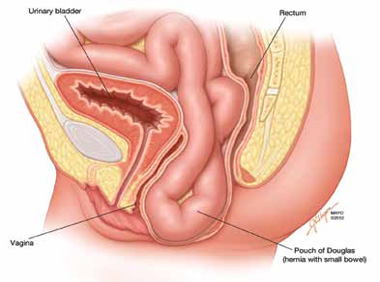

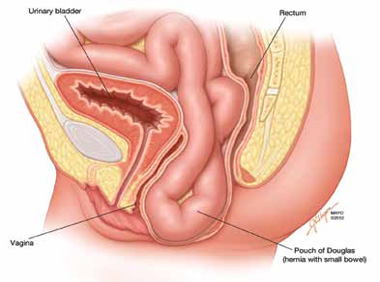

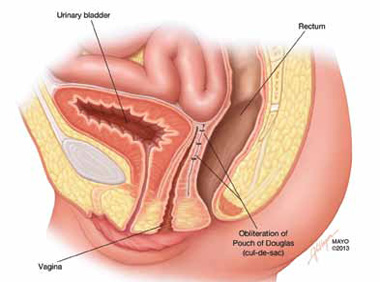

The phenomenon has been variably referred to in the literature as enterocele, descending perineum syndrome, peritoneocele, or Pouch of Douglas hernia. The concept was first introduced in 19663 and describes descent of the entire pelvic floor and small bowel through a hernia in the Pouch of Douglas (FIGURE 1).

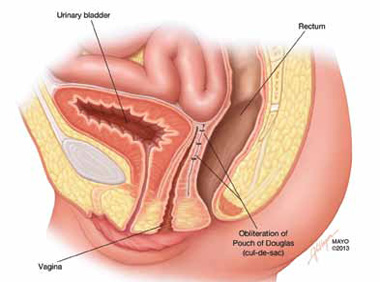

FIGURE 1: Pouch of Douglas hernia. The pelvic floor and small bowel descend into the Pouch of Douglas.

How does it occur? The pathophysiology is thought to be related to excessive abdominal straining in individuals with chronic constipation. This results in diminished pelvic floor muscle tone. Eventually, the whole pelvic floor descends, becoming funnel shaped due to stretching of the puborectalis muscle. Thus, stool is expelled by force, mostly through forces on the anterior rectal wall (which tends to prolapse after stool evacuation, with accompanied mucus secretion, soreness, and irritation).

Clinical pearl: Given the rectal wall prolapse that occurs after stool evacuation in Pouch of Douglas hernia, some patients will describe a rectal lump that bleeds after a bowel movement. The sensation of the rectal lump from the anterior rectal wall prolapse causes further straining.

Your patient reports pelvic pressure and bulge.

How do you proceed?

Physical examination

Look for perineal ballooning. Physical examination should start with inspection of the external genitalia. This inspection will identify any pelvic organ prolapse at or beyond the introitus. However, a Pouch of Douglas hernia will be missed if the patient is not examined during Valsalva or maximal strain. This maneuver will demonstrate the classic finding of perineal ballooning and is crucial to a final diagnosis of Pouch of Douglas hernia. Normally, the perineum will descend 1 cm to 2 cm during maximal strain; in Pouch of Douglas hernias, the perineum can descend up to 4 cm to 8 cm.4

Clinical pearl: It should be noted that, often, patients will not have a great deal of vaginal prolapse accompanying the perineal ballooning. In our opinion, this finding distinguishes Pouch of Douglas hernia from a vaginal vault prolapse caused by an enterocele.

Is rectal prolapse present? Beyond perineal ballooning, the presence of rectal prolapse should be evaluated. A rectocele of some degree is usually present. Asymmetric rectal prolapse affecting the anterior aspect of the rectal wall is consistent with a Pouch of Douglas hernia. This anatomic finding should be distinguished from true circumferential rectal prolapse, which remains in the differential diagnosis.

Basing the diagnosis of Pouch of Douglas hernia on physical examination alone can be difficult. Therefore, imaging studies are essential for accurate diagnosis.

Imaging investigations

Several imaging modalities can be used to diagnose such disorders of the pelvic floor as Pouch of Douglas hernia. These include:

- dynamic colpocystoproctography5

- defecography with oral barium6

- dynamic pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).7

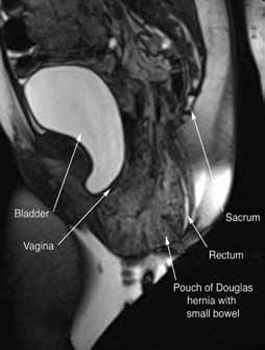

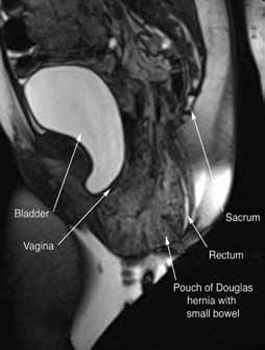

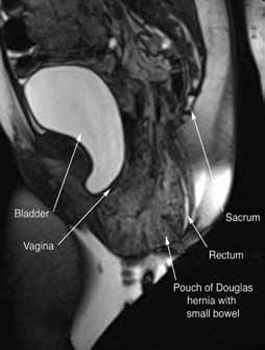

In our experience, dynamic pelvic MRI has a high accuracy rate for diagnosing Pouch of Douglas hernia. FIGURE 2 illustrates the large Pouch of Douglas hernia filled with loops of small bowel. Perineal descent of the anorectal junction more than 3 cm below the pubococcygeal line during maximal straining is a diagnostic finding on imaging.7

FIGURE 2: MRI

Sagittal MRI during maximal Valsalva straining, demonstrating Pouch of Douglas hernia filled with small bowel.

What are your patient’s treatment options?

Reduce straining during bowel movements. The primary goal of treatment for Pouch of Douglas hernia should be relief of bothersome symptoms. Therefore, further damage can be prevented by eliminating straining during defecation. This can be accomplished with a bowel regimen that combines an irritant suppository (glycerin or bisacodyl) with a fiber supplement (the latter to increase bulk of the stool). Oral laxatives have limited use as many patients have lax anal sphincters and liquid stool could cause fecal incontinence.

Pelvic floor strengthening. The importance of pelvic floor physical therapy should be stressed. Patients can benefit from the use of modalities such as biofeedback to learn appropriate pelvic floor muscle relaxation techniques during defecation.8 While there is limited published evidence supporting the use of pelvic floor physical therapy, our anecdotal experience suggests that patients can gain considerable benefit with such conservative therapy.

Surgical therapy

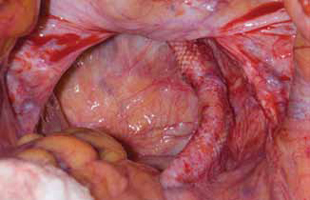

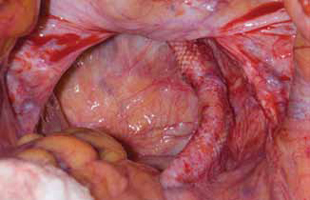

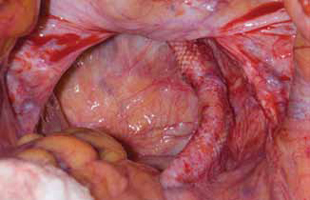

Surgical repair of Pouch of Douglas hernia requires obliteration of the deep cul-de-sac (to prevent the small bowel from filling this space) and simultaneous pelvic floor reconstruction of the vaginal apex and any other compartments that are prolapsing (if pelvic organ prolapse is present). In our experience, these patients typically have derived greatest benefit from an abdominal approach. This usually can be accomplished with a sacrocolpopexy (if vaginal vault prolapse exists) with a Moschowitz or Halban procedure,9 uterosacral ligament plication, or a modified sacrocolpopexy with mesh augmentation to the sidewalls of the pelvis.10 There are currently no studies supporting one particular approach over another, but the most important feature of a surgical intervention is obliteration of the cul-de-sac (FIGURES 3, 4, and 5).

FIGURE 3: Open cul-de-sac. Open cul-de-sac after a prior abdominal sacrocolpopexy in a patient with a Pouch of Douglas hernia.

FIGURE 4: Obliterated cul-de-sac. Obliteration of the cul-de-sac with uterosacral ligament plication. Care is taken to prevent obstruction of the rectum at this level.

FIGURE 5: Cul-de-sac obliteration. Schematic diagram of obliteration of the cul-de-sac with uterosacral ligament plication sutures.

Final takeaways

Pouch of Douglas hernia is an important but often unrecognized cause of pelvic pressure and defecatory dysfunction. Perineal ballooning during maximal straining is highly suggestive of the diagnosis, with final diagnosis confirmed with various functional imaging studies of the pelvic floor. Management should include both conservative and surgical interventions to alleviate and prevent recurrence of symptoms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT. The authors would like to thank Mr. John Hagen, Medical Illustrator, Mayo Clinic, for producing the illustrations in Figures 1 and 5.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Urinary incontinence

Karen L. Noblett, MD, MAS, and Stephanie A. Jacobs, MD (Update, December 2012)

When and how to place an autologous rectus fascia

pubovaginal sling

Mickey Karram, MD, and Dani Zoorob, MD (Surgical Techniques, November 2012)

Pelvic floor dysfunction

Autumn L. Edenfield, MD, and Cindy L. Amundsen, MD (Update, October 2012)

Step by step: Obliterating the vaginal canal to correct pelvic organ prolapse

Mickey Karram, MD, and Janelle Evans, MD (Surgical Techniques, February 2012)

1. Samuelsson EC, Victor FT, Tibblin G, Svärdsudd KF. Signs of genital prolapse in a Swedish population of women 20 to 59 years of age and possible related factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180(2 Pt 1):299-305.

2. Boyles SH, Weber AM, Meyn L. Procedures for pelvic organ prolapse in the United States 1979-1997. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(1):108-115.

3. Parks AG, Porter NH, Hardcastle J. The syndrome of the descending perineum. Proc R Soc Med. 1966;59(6):477-482.

4. Hardcastle JD. The descending perineum syndrome. Practitioner. 1969;203(217):612-619.

5. Maglinte DD, Bartram CI, Hale DA, et al. Functional imaging of the pelvic floor. Radiology. 2011;258(1):23-39.

6. Roos JE, Weishaupt D, Wildermuth S, Willmann JK, Marincek B, Hilfiker PR. Experience of 4 years with open MR defecography: pictorial review of anorectal anatomy and disease. Radiographics. 2002;22(4):817-832.

7. Fletcher JG, Busse RF, Riederer SJ, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of anatomic and dynamic defects of the pelvic floor in defecatory disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(2):399-411.

8. Harewood GC, Coulie B, Camilleri M, Rath-Harvey D, Pemberton JH. Descending perineum syndrome: audit of clinical and laboratory features and outcome of pelvic floor retraining. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(1):126-130.

9. Moschcowitz AV. The pathogenesis anatomy and cure of prolapse of the rectum. Surg Gyncol Obstetrics. 1912;15:7-21.

10. Gosselink MJ, van Dam JH, Huisman WM, Ginai AZ, Schouten WR. Treatment of enterocele by obliteration of the pelvic inlet. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42(7):940-944.

CASE: Pelvic organ prolapse or Pouch of Douglas hernia?

A 42-year-old G3P2 woman is referred to you by her primary care provider for pelvic organ prolapse. Her medical history reveals that she has been bothered by a sense of pelvic pressure and bulge progressing over several years, and she has noticed that her symptoms are particularly worse during and after bowel movements. She reports some improved bowel evacuation with external splinting of her perineum. Upon closer questioning, the patient reports a history of chronic constipation since childhood associated with straining and a sense of incomplete emptying. She reports spending up to 30 minutes three to four times per day on the commode to completely empty her bowels.

Physical examination reveals an overweight woman with a soft, nontender abdomen remarkable for laparoscopic incision scars from a previous tubal ligation. Inspection of the external genitalia at rest is normal. Cough stress test is negative. At maximum Valsalva, however, there is significant perineal ballooning present.

Speculum examination demonstrates grade 1 uterine prolapse, grade 1 cystocele, and grade 2 rectocele. There is no evidence of pelvic floor tension myalgia. She has weak pelvic muscle strength. Visualization of the anus at maximum Valsalva reveals there is some asymmetric rectal prolapse of the anterior rectal wall. Digital rectal exam is unremarkable.

Are these patient’s symptoms due to pelvic organ prolapse or Pouch of Douglas hernia?

Pelvic organ prolapse: A common problem

Pelvic organ prolapse has an estimated prevalence of 55% in women aged 50 to 59 years.1 More than 200,000 pelvic organ prolapse surgeries are performed annually in the United States.2 Typically, patients report:

- vaginal bulge causing discomfort

- pelvic pressure or heaviness, or

- rubbing of the vaginal bulge on undergarments.

In more advanced pelvic organ prolapse, patients may report voiding dysfunction or stool trapping that requires manual splinting of the prolapse to assist in bladder and bowel evacuation.

Pouch of Douglas hernia: A lesser-known

(recognized) phenomenon

Similar to pelvic organ prolapse, Pouch of Douglas hernia also can present with symptoms of:

- pelvic pressure

- vague perineal aching

- defecatory dysfunction.

The phenomenon has been variably referred to in the literature as enterocele, descending perineum syndrome, peritoneocele, or Pouch of Douglas hernia. The concept was first introduced in 19663 and describes descent of the entire pelvic floor and small bowel through a hernia in the Pouch of Douglas (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1: Pouch of Douglas hernia. The pelvic floor and small bowel descend into the Pouch of Douglas.

How does it occur? The pathophysiology is thought to be related to excessive abdominal straining in individuals with chronic constipation. This results in diminished pelvic floor muscle tone. Eventually, the whole pelvic floor descends, becoming funnel shaped due to stretching of the puborectalis muscle. Thus, stool is expelled by force, mostly through forces on the anterior rectal wall (which tends to prolapse after stool evacuation, with accompanied mucus secretion, soreness, and irritation).

Clinical pearl: Given the rectal wall prolapse that occurs after stool evacuation in Pouch of Douglas hernia, some patients will describe a rectal lump that bleeds after a bowel movement. The sensation of the rectal lump from the anterior rectal wall prolapse causes further straining.

Your patient reports pelvic pressure and bulge.

How do you proceed?

Physical examination

Look for perineal ballooning. Physical examination should start with inspection of the external genitalia. This inspection will identify any pelvic organ prolapse at or beyond the introitus. However, a Pouch of Douglas hernia will be missed if the patient is not examined during Valsalva or maximal strain. This maneuver will demonstrate the classic finding of perineal ballooning and is crucial to a final diagnosis of Pouch of Douglas hernia. Normally, the perineum will descend 1 cm to 2 cm during maximal strain; in Pouch of Douglas hernias, the perineum can descend up to 4 cm to 8 cm.4

Clinical pearl: It should be noted that, often, patients will not have a great deal of vaginal prolapse accompanying the perineal ballooning. In our opinion, this finding distinguishes Pouch of Douglas hernia from a vaginal vault prolapse caused by an enterocele.

Is rectal prolapse present? Beyond perineal ballooning, the presence of rectal prolapse should be evaluated. A rectocele of some degree is usually present. Asymmetric rectal prolapse affecting the anterior aspect of the rectal wall is consistent with a Pouch of Douglas hernia. This anatomic finding should be distinguished from true circumferential rectal prolapse, which remains in the differential diagnosis.

Basing the diagnosis of Pouch of Douglas hernia on physical examination alone can be difficult. Therefore, imaging studies are essential for accurate diagnosis.

Imaging investigations

Several imaging modalities can be used to diagnose such disorders of the pelvic floor as Pouch of Douglas hernia. These include:

- dynamic colpocystoproctography5

- defecography with oral barium6

- dynamic pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).7

In our experience, dynamic pelvic MRI has a high accuracy rate for diagnosing Pouch of Douglas hernia. FIGURE 2 illustrates the large Pouch of Douglas hernia filled with loops of small bowel. Perineal descent of the anorectal junction more than 3 cm below the pubococcygeal line during maximal straining is a diagnostic finding on imaging.7

FIGURE 2: MRI

Sagittal MRI during maximal Valsalva straining, demonstrating Pouch of Douglas hernia filled with small bowel.

What are your patient’s treatment options?

Reduce straining during bowel movements. The primary goal of treatment for Pouch of Douglas hernia should be relief of bothersome symptoms. Therefore, further damage can be prevented by eliminating straining during defecation. This can be accomplished with a bowel regimen that combines an irritant suppository (glycerin or bisacodyl) with a fiber supplement (the latter to increase bulk of the stool). Oral laxatives have limited use as many patients have lax anal sphincters and liquid stool could cause fecal incontinence.

Pelvic floor strengthening. The importance of pelvic floor physical therapy should be stressed. Patients can benefit from the use of modalities such as biofeedback to learn appropriate pelvic floor muscle relaxation techniques during defecation.8 While there is limited published evidence supporting the use of pelvic floor physical therapy, our anecdotal experience suggests that patients can gain considerable benefit with such conservative therapy.

Surgical therapy

Surgical repair of Pouch of Douglas hernia requires obliteration of the deep cul-de-sac (to prevent the small bowel from filling this space) and simultaneous pelvic floor reconstruction of the vaginal apex and any other compartments that are prolapsing (if pelvic organ prolapse is present). In our experience, these patients typically have derived greatest benefit from an abdominal approach. This usually can be accomplished with a sacrocolpopexy (if vaginal vault prolapse exists) with a Moschowitz or Halban procedure,9 uterosacral ligament plication, or a modified sacrocolpopexy with mesh augmentation to the sidewalls of the pelvis.10 There are currently no studies supporting one particular approach over another, but the most important feature of a surgical intervention is obliteration of the cul-de-sac (FIGURES 3, 4, and 5).

FIGURE 3: Open cul-de-sac. Open cul-de-sac after a prior abdominal sacrocolpopexy in a patient with a Pouch of Douglas hernia.

FIGURE 4: Obliterated cul-de-sac. Obliteration of the cul-de-sac with uterosacral ligament plication. Care is taken to prevent obstruction of the rectum at this level.

FIGURE 5: Cul-de-sac obliteration. Schematic diagram of obliteration of the cul-de-sac with uterosacral ligament plication sutures.

Final takeaways

Pouch of Douglas hernia is an important but often unrecognized cause of pelvic pressure and defecatory dysfunction. Perineal ballooning during maximal straining is highly suggestive of the diagnosis, with final diagnosis confirmed with various functional imaging studies of the pelvic floor. Management should include both conservative and surgical interventions to alleviate and prevent recurrence of symptoms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT. The authors would like to thank Mr. John Hagen, Medical Illustrator, Mayo Clinic, for producing the illustrations in Figures 1 and 5.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Urinary incontinence

Karen L. Noblett, MD, MAS, and Stephanie A. Jacobs, MD (Update, December 2012)

When and how to place an autologous rectus fascia

pubovaginal sling

Mickey Karram, MD, and Dani Zoorob, MD (Surgical Techniques, November 2012)

Pelvic floor dysfunction

Autumn L. Edenfield, MD, and Cindy L. Amundsen, MD (Update, October 2012)

Step by step: Obliterating the vaginal canal to correct pelvic organ prolapse

Mickey Karram, MD, and Janelle Evans, MD (Surgical Techniques, February 2012)

CASE: Pelvic organ prolapse or Pouch of Douglas hernia?

A 42-year-old G3P2 woman is referred to you by her primary care provider for pelvic organ prolapse. Her medical history reveals that she has been bothered by a sense of pelvic pressure and bulge progressing over several years, and she has noticed that her symptoms are particularly worse during and after bowel movements. She reports some improved bowel evacuation with external splinting of her perineum. Upon closer questioning, the patient reports a history of chronic constipation since childhood associated with straining and a sense of incomplete emptying. She reports spending up to 30 minutes three to four times per day on the commode to completely empty her bowels.

Physical examination reveals an overweight woman with a soft, nontender abdomen remarkable for laparoscopic incision scars from a previous tubal ligation. Inspection of the external genitalia at rest is normal. Cough stress test is negative. At maximum Valsalva, however, there is significant perineal ballooning present.

Speculum examination demonstrates grade 1 uterine prolapse, grade 1 cystocele, and grade 2 rectocele. There is no evidence of pelvic floor tension myalgia. She has weak pelvic muscle strength. Visualization of the anus at maximum Valsalva reveals there is some asymmetric rectal prolapse of the anterior rectal wall. Digital rectal exam is unremarkable.

Are these patient’s symptoms due to pelvic organ prolapse or Pouch of Douglas hernia?

Pelvic organ prolapse: A common problem

Pelvic organ prolapse has an estimated prevalence of 55% in women aged 50 to 59 years.1 More than 200,000 pelvic organ prolapse surgeries are performed annually in the United States.2 Typically, patients report:

- vaginal bulge causing discomfort

- pelvic pressure or heaviness, or

- rubbing of the vaginal bulge on undergarments.

In more advanced pelvic organ prolapse, patients may report voiding dysfunction or stool trapping that requires manual splinting of the prolapse to assist in bladder and bowel evacuation.

Pouch of Douglas hernia: A lesser-known

(recognized) phenomenon

Similar to pelvic organ prolapse, Pouch of Douglas hernia also can present with symptoms of:

- pelvic pressure

- vague perineal aching

- defecatory dysfunction.

The phenomenon has been variably referred to in the literature as enterocele, descending perineum syndrome, peritoneocele, or Pouch of Douglas hernia. The concept was first introduced in 19663 and describes descent of the entire pelvic floor and small bowel through a hernia in the Pouch of Douglas (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1: Pouch of Douglas hernia. The pelvic floor and small bowel descend into the Pouch of Douglas.

How does it occur? The pathophysiology is thought to be related to excessive abdominal straining in individuals with chronic constipation. This results in diminished pelvic floor muscle tone. Eventually, the whole pelvic floor descends, becoming funnel shaped due to stretching of the puborectalis muscle. Thus, stool is expelled by force, mostly through forces on the anterior rectal wall (which tends to prolapse after stool evacuation, with accompanied mucus secretion, soreness, and irritation).

Clinical pearl: Given the rectal wall prolapse that occurs after stool evacuation in Pouch of Douglas hernia, some patients will describe a rectal lump that bleeds after a bowel movement. The sensation of the rectal lump from the anterior rectal wall prolapse causes further straining.

Your patient reports pelvic pressure and bulge.

How do you proceed?

Physical examination

Look for perineal ballooning. Physical examination should start with inspection of the external genitalia. This inspection will identify any pelvic organ prolapse at or beyond the introitus. However, a Pouch of Douglas hernia will be missed if the patient is not examined during Valsalva or maximal strain. This maneuver will demonstrate the classic finding of perineal ballooning and is crucial to a final diagnosis of Pouch of Douglas hernia. Normally, the perineum will descend 1 cm to 2 cm during maximal strain; in Pouch of Douglas hernias, the perineum can descend up to 4 cm to 8 cm.4

Clinical pearl: It should be noted that, often, patients will not have a great deal of vaginal prolapse accompanying the perineal ballooning. In our opinion, this finding distinguishes Pouch of Douglas hernia from a vaginal vault prolapse caused by an enterocele.

Is rectal prolapse present? Beyond perineal ballooning, the presence of rectal prolapse should be evaluated. A rectocele of some degree is usually present. Asymmetric rectal prolapse affecting the anterior aspect of the rectal wall is consistent with a Pouch of Douglas hernia. This anatomic finding should be distinguished from true circumferential rectal prolapse, which remains in the differential diagnosis.

Basing the diagnosis of Pouch of Douglas hernia on physical examination alone can be difficult. Therefore, imaging studies are essential for accurate diagnosis.

Imaging investigations

Several imaging modalities can be used to diagnose such disorders of the pelvic floor as Pouch of Douglas hernia. These include:

- dynamic colpocystoproctography5

- defecography with oral barium6

- dynamic pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).7

In our experience, dynamic pelvic MRI has a high accuracy rate for diagnosing Pouch of Douglas hernia. FIGURE 2 illustrates the large Pouch of Douglas hernia filled with loops of small bowel. Perineal descent of the anorectal junction more than 3 cm below the pubococcygeal line during maximal straining is a diagnostic finding on imaging.7

FIGURE 2: MRI

Sagittal MRI during maximal Valsalva straining, demonstrating Pouch of Douglas hernia filled with small bowel.

What are your patient’s treatment options?

Reduce straining during bowel movements. The primary goal of treatment for Pouch of Douglas hernia should be relief of bothersome symptoms. Therefore, further damage can be prevented by eliminating straining during defecation. This can be accomplished with a bowel regimen that combines an irritant suppository (glycerin or bisacodyl) with a fiber supplement (the latter to increase bulk of the stool). Oral laxatives have limited use as many patients have lax anal sphincters and liquid stool could cause fecal incontinence.

Pelvic floor strengthening. The importance of pelvic floor physical therapy should be stressed. Patients can benefit from the use of modalities such as biofeedback to learn appropriate pelvic floor muscle relaxation techniques during defecation.8 While there is limited published evidence supporting the use of pelvic floor physical therapy, our anecdotal experience suggests that patients can gain considerable benefit with such conservative therapy.

Surgical therapy

Surgical repair of Pouch of Douglas hernia requires obliteration of the deep cul-de-sac (to prevent the small bowel from filling this space) and simultaneous pelvic floor reconstruction of the vaginal apex and any other compartments that are prolapsing (if pelvic organ prolapse is present). In our experience, these patients typically have derived greatest benefit from an abdominal approach. This usually can be accomplished with a sacrocolpopexy (if vaginal vault prolapse exists) with a Moschowitz or Halban procedure,9 uterosacral ligament plication, or a modified sacrocolpopexy with mesh augmentation to the sidewalls of the pelvis.10 There are currently no studies supporting one particular approach over another, but the most important feature of a surgical intervention is obliteration of the cul-de-sac (FIGURES 3, 4, and 5).

FIGURE 3: Open cul-de-sac. Open cul-de-sac after a prior abdominal sacrocolpopexy in a patient with a Pouch of Douglas hernia.

FIGURE 4: Obliterated cul-de-sac. Obliteration of the cul-de-sac with uterosacral ligament plication. Care is taken to prevent obstruction of the rectum at this level.

FIGURE 5: Cul-de-sac obliteration. Schematic diagram of obliteration of the cul-de-sac with uterosacral ligament plication sutures.

Final takeaways

Pouch of Douglas hernia is an important but often unrecognized cause of pelvic pressure and defecatory dysfunction. Perineal ballooning during maximal straining is highly suggestive of the diagnosis, with final diagnosis confirmed with various functional imaging studies of the pelvic floor. Management should include both conservative and surgical interventions to alleviate and prevent recurrence of symptoms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT. The authors would like to thank Mr. John Hagen, Medical Illustrator, Mayo Clinic, for producing the illustrations in Figures 1 and 5.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Urinary incontinence

Karen L. Noblett, MD, MAS, and Stephanie A. Jacobs, MD (Update, December 2012)

When and how to place an autologous rectus fascia

pubovaginal sling

Mickey Karram, MD, and Dani Zoorob, MD (Surgical Techniques, November 2012)

Pelvic floor dysfunction

Autumn L. Edenfield, MD, and Cindy L. Amundsen, MD (Update, October 2012)

Step by step: Obliterating the vaginal canal to correct pelvic organ prolapse

Mickey Karram, MD, and Janelle Evans, MD (Surgical Techniques, February 2012)

1. Samuelsson EC, Victor FT, Tibblin G, Svärdsudd KF. Signs of genital prolapse in a Swedish population of women 20 to 59 years of age and possible related factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180(2 Pt 1):299-305.

2. Boyles SH, Weber AM, Meyn L. Procedures for pelvic organ prolapse in the United States 1979-1997. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(1):108-115.

3. Parks AG, Porter NH, Hardcastle J. The syndrome of the descending perineum. Proc R Soc Med. 1966;59(6):477-482.

4. Hardcastle JD. The descending perineum syndrome. Practitioner. 1969;203(217):612-619.

5. Maglinte DD, Bartram CI, Hale DA, et al. Functional imaging of the pelvic floor. Radiology. 2011;258(1):23-39.

6. Roos JE, Weishaupt D, Wildermuth S, Willmann JK, Marincek B, Hilfiker PR. Experience of 4 years with open MR defecography: pictorial review of anorectal anatomy and disease. Radiographics. 2002;22(4):817-832.

7. Fletcher JG, Busse RF, Riederer SJ, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of anatomic and dynamic defects of the pelvic floor in defecatory disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(2):399-411.

8. Harewood GC, Coulie B, Camilleri M, Rath-Harvey D, Pemberton JH. Descending perineum syndrome: audit of clinical and laboratory features and outcome of pelvic floor retraining. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(1):126-130.

9. Moschcowitz AV. The pathogenesis anatomy and cure of prolapse of the rectum. Surg Gyncol Obstetrics. 1912;15:7-21.

10. Gosselink MJ, van Dam JH, Huisman WM, Ginai AZ, Schouten WR. Treatment of enterocele by obliteration of the pelvic inlet. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42(7):940-944.

1. Samuelsson EC, Victor FT, Tibblin G, Svärdsudd KF. Signs of genital prolapse in a Swedish population of women 20 to 59 years of age and possible related factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180(2 Pt 1):299-305.

2. Boyles SH, Weber AM, Meyn L. Procedures for pelvic organ prolapse in the United States 1979-1997. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(1):108-115.

3. Parks AG, Porter NH, Hardcastle J. The syndrome of the descending perineum. Proc R Soc Med. 1966;59(6):477-482.

4. Hardcastle JD. The descending perineum syndrome. Practitioner. 1969;203(217):612-619.

5. Maglinte DD, Bartram CI, Hale DA, et al. Functional imaging of the pelvic floor. Radiology. 2011;258(1):23-39.

6. Roos JE, Weishaupt D, Wildermuth S, Willmann JK, Marincek B, Hilfiker PR. Experience of 4 years with open MR defecography: pictorial review of anorectal anatomy and disease. Radiographics. 2002;22(4):817-832.

7. Fletcher JG, Busse RF, Riederer SJ, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of anatomic and dynamic defects of the pelvic floor in defecatory disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(2):399-411.

8. Harewood GC, Coulie B, Camilleri M, Rath-Harvey D, Pemberton JH. Descending perineum syndrome: audit of clinical and laboratory features and outcome of pelvic floor retraining. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(1):126-130.

9. Moschcowitz AV. The pathogenesis anatomy and cure of prolapse of the rectum. Surg Gyncol Obstetrics. 1912;15:7-21.

10. Gosselink MJ, van Dam JH, Huisman WM, Ginai AZ, Schouten WR. Treatment of enterocele by obliteration of the pelvic inlet. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42(7):940-944.

IN THIS ARTICLE

Clinical pearls at physical exam

Treatment options