User login

Endoscopic Sleeve Gastroplasty is an Effective Treatment for Obesity in a Veteran With Metabolic and Psychiatric Comorbidities

Endoscopic Sleeve Gastroplasty is an Effective Treatment for Obesity in a Veteran With Metabolic and Psychiatric Comorbidities

Obesity is a growing worldwide epidemic with significant implications for individual health and public health care costs. It is also associated with several medical conditions, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and mental health disorders.1 Comprehensive lifestyle intervention is a first-line therapy for obesity consisting of dietary and exercise interventions. Despite initial success, long-term results and durability of weight loss with lifestyle modifications are limited. 2 Bariatric surgery, including sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass surgery, is a more invasive approach that is highly effective in weight loss. However, these operations are not reversible, and patients may not be eligible for or may not desire surgery. Overall, bariatric surgery is widely underutilized, with < 1% of eligible patients ultimately undergoing surgery.3,4

Endoscopic bariatric therapies are increasingly popular procedures that address the need for additional treatments for obesity among individuals who have not had success with lifestyle changes and are not surgical candidates. The most common procedure is the endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty (ESG), which applies full-thickness sutures in the stomach to reduce gastric volume, delay gastric emptying, and limit food intake while keeping the fundus intact compared with sleeve gastrectomy. This procedure is typically considered in patients with body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30, who do not qualify for or do not want traditional bariatric surgery. The literature supports robust outcomes after ESG, with studies demonstrating significant and sustained total body weight loss of up to 14% to 16% at 5 years and significant improvement in ≥ 1 metabolic comorbidities in 80% of patients.5,6 ESG adverse events (AEs) include abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting that are typically self-limited to 1 week. Rarer but more serious AEs include bleeding, perforation, or infection, and occur in 2% of cases based on large trial data.5,7

Although the weight loss benefits of ESG are well established, to date, there are limited data on the effects of endoscopic bariatric therapies like ESG on mental health conditions. Here, we describe a case of a veteran with a history of mental health disorders that prevented him from completing bariatric surgery. The patient underwent ESG and had a successful clinical course.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 59-year-old male veteran with a medical history of class III obesity (42.4 BMI), obstructive sleep apnea, hypothyroidism, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and a large ventral hernia was referred to the MOVE! (Management of Overweight/ Obese Veterans Everywhere!) multidisciplinary high-intensity weight loss program at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) West Los Angeles VA Medical Center (WLAVAMC). His psychiatric history included generalized anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and panic disorder, managed by the Psychiatry Service and treated with sertraline 25 mg daily, lorazepam 0.5 mg twice daily, and hydroxyzine 20 mg nightly. He had previously implemented lifestyle changes and attended MOVE! classes and nutrition coaching for 1 year but was unsuccessful in losing weight. He had also tried liraglutide 3 mg daily for weight loss but was unable to tolerate it and reported worsening medication-related anxiety.

The patient declined further weight loss pharmacotherapy and was referred to bariatric surgery. He was scheduled for a surgical sleeve gastrectomy. However, on the day he arrived at the hospital for surgery, he developed severe anxiety and had a panic attack, and it was canceled. Due to his mental health issues, he was no longer comfortable proceeding with surgery and was left without other options for obesity treatment. The veteran was extremely disappointed because the ventral hernia caused significant quality of life impairment, limited his ability to exercise, and caused him embarrassment in public settings. The hernia could not be surgically repaired until there was significant weight loss.

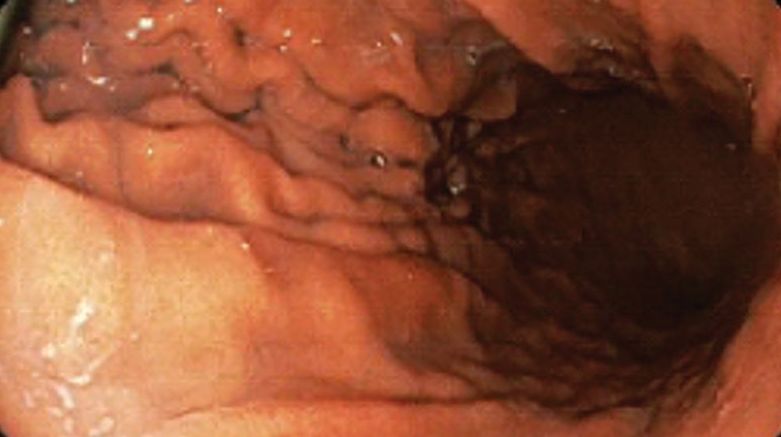

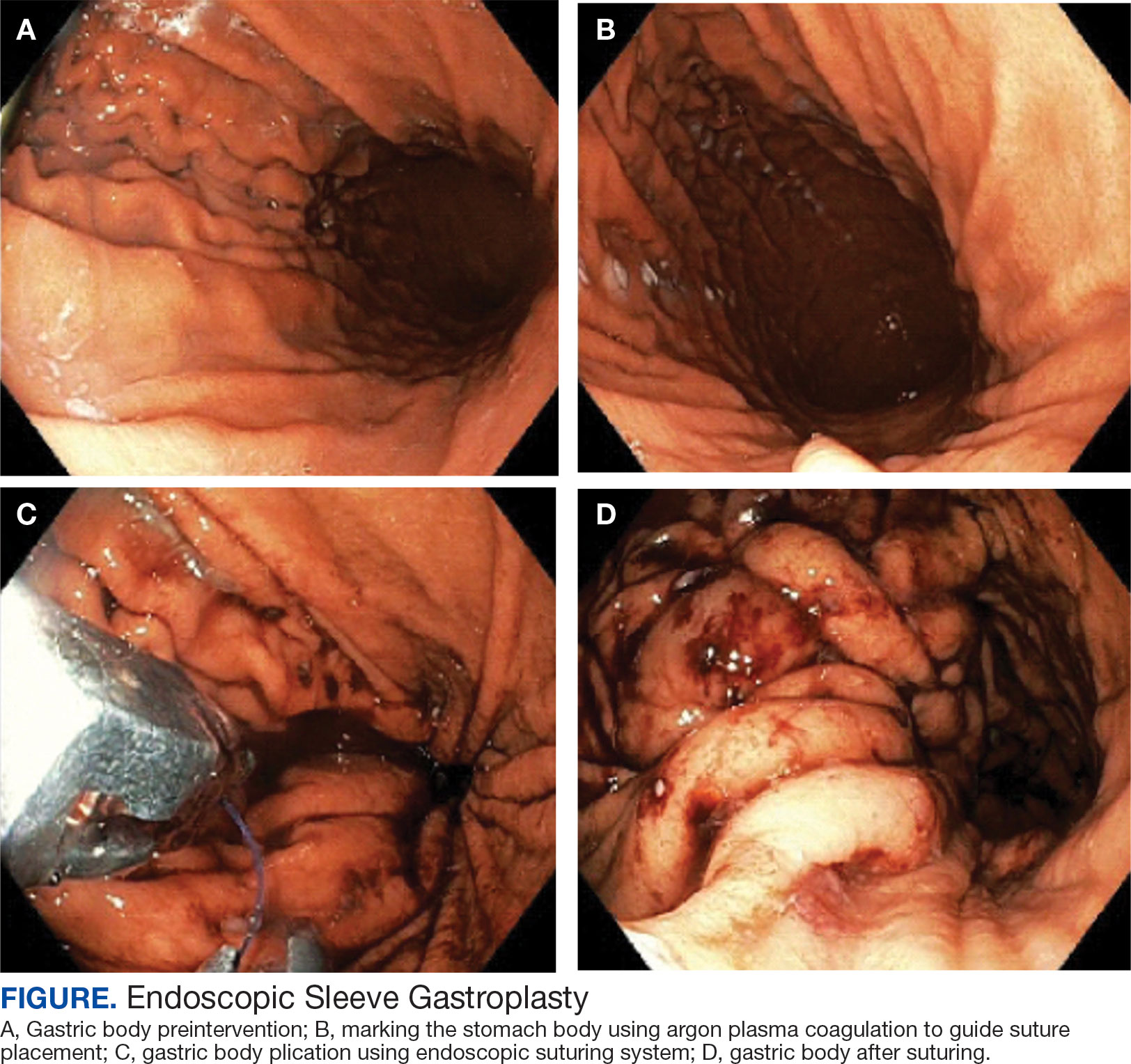

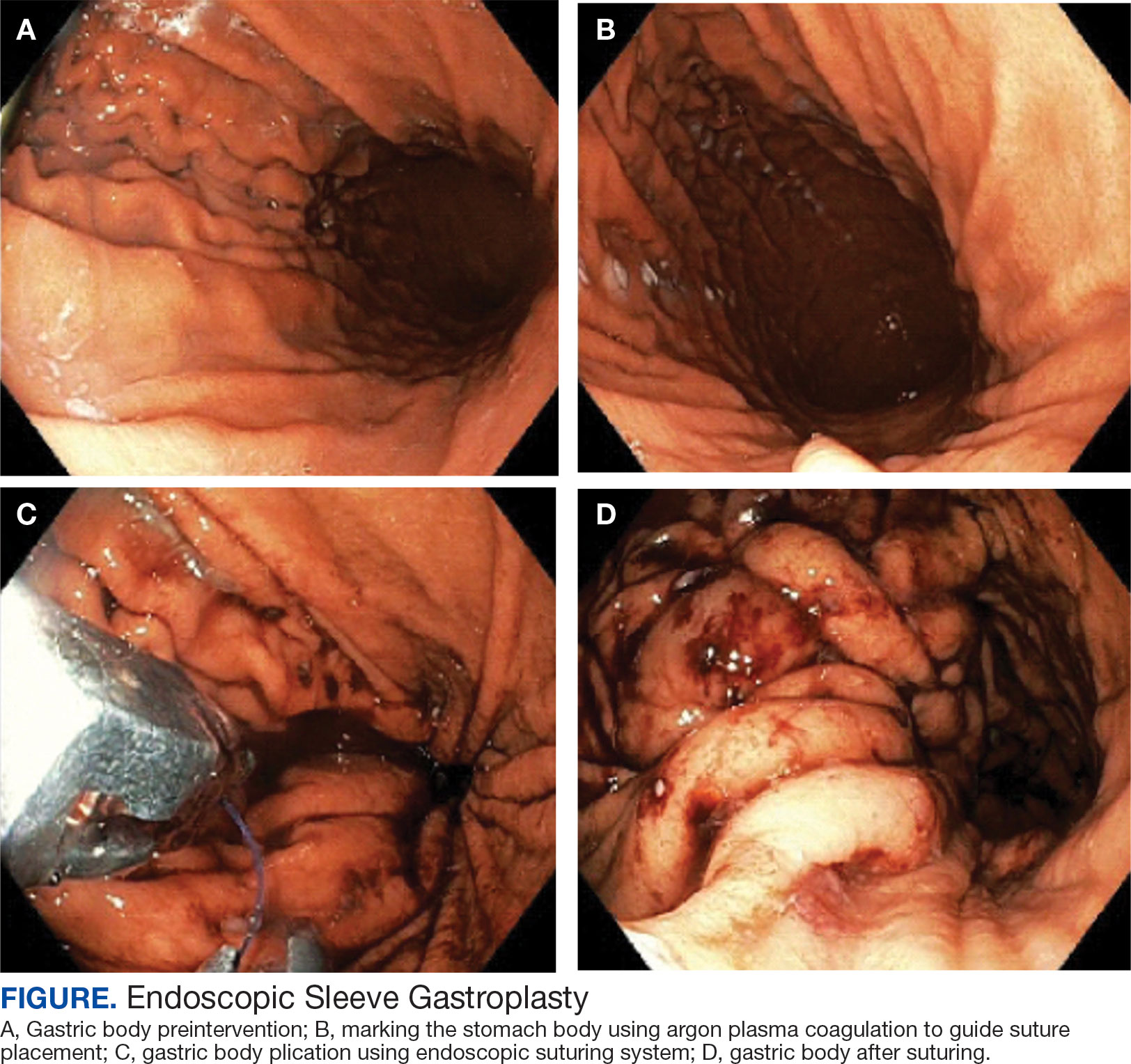

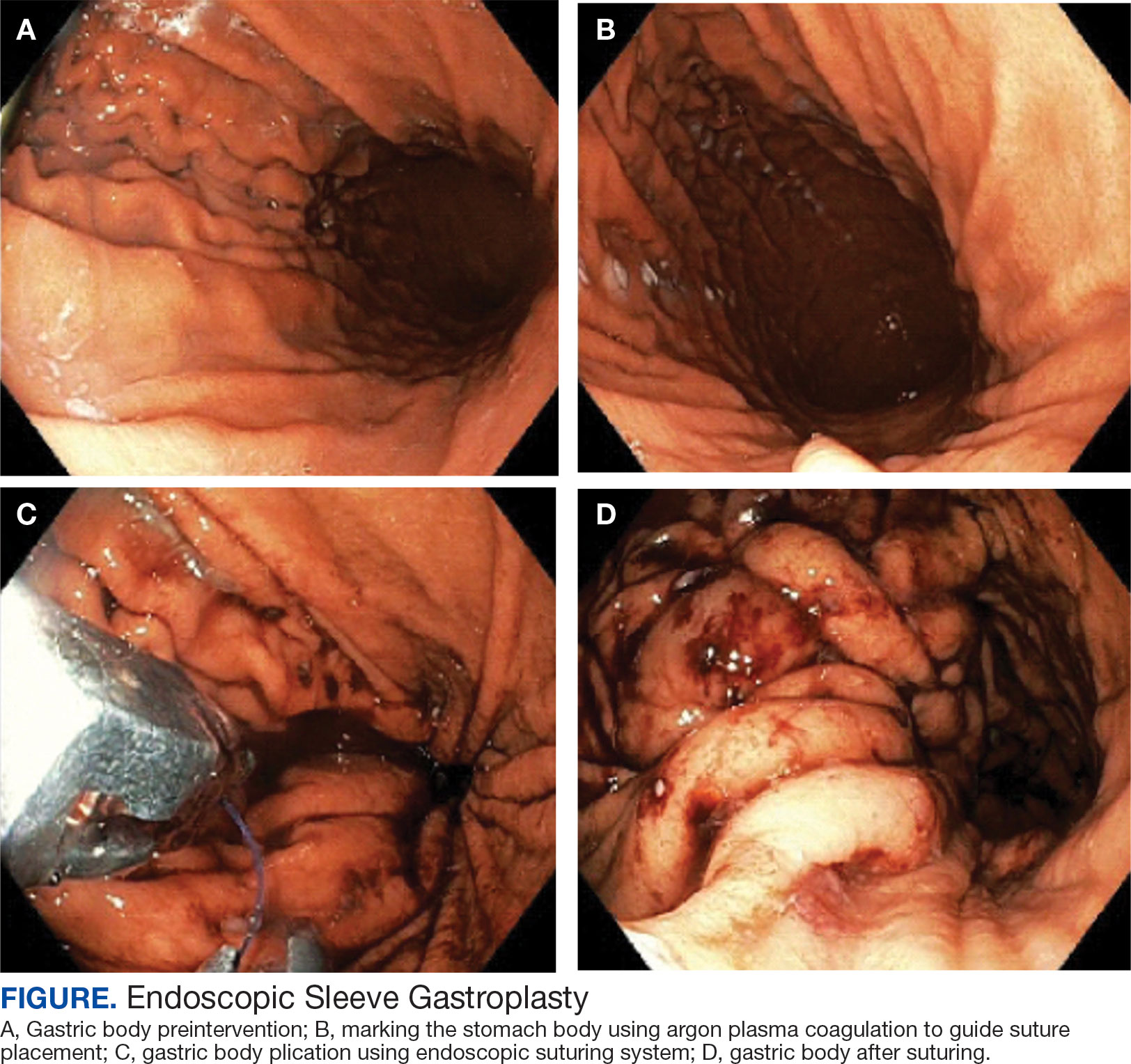

A bariatric endoscopy program within the Division of Gastroenterology was developed and implemented at the WLAVAMC in February 2023 in conjunction with MOVE! The patient was referred for consideration of an endoscopic weight loss procedure. He was determined to be a suitable candidate for ESG based on his BMI being > 40 and personal preference not to proceed with surgery to lose enough weight to qualify for hernia repair. The veteran underwent an endoscopy, which showed normal anatomy and gastric mucosa. ESG was performed in standard fashion (Figure).8 Three vertical lines were made using argon plasma coagulation from the incisura to 2 cm below the gastroesophageal junction along the anterior, posterior, and greater curvature of the stomach to mark the area for endoscopic suture placement. Starting at the incisura, 7 full-thickness sutures were placed to create a volume reduction plication, with preservation of the fundus. The patient did well postprocedure with no immediate or delayed AEs and was discharged home the same day.

Follow-up

The veteran followed a gradual dietary advancement from a clear liquid diet to pureed and soft texture food. The patient’s weight dropped from 359 lbs preprocedure to 304 lbs 6 months postprocedure, a total body weight loss (TWBL) of 15.3%. At 12 months the veteran weighed 299 lbs (16.7% TBWL). He also had notable improvements in metabolic parameters. His systolic blood pressure decreased from ≥ 140 mm Hg to 120 to 130 mm Hg and hemoglobin A1c dropped from 7.0% to 6.3%. Remarkably, his psychiatrist noted significant improvement in his overall mental health. The veteran reported complete cessation of panic attacks since the ESG, improvements in PTSD and anxiety, and was able to discontinue lorazepam and decrease his dose of sertraline to 12.5 mg daily. He reported feeling more energetic and goal-oriented with increased clarity of thought. Perhaps the most significant outcome was that after the 55-lb weight loss at 6 months, the patient was eligible to undergo ventral hernia surgical repair, which had previously contributed to shame and social isolation. This, in turn, improved his quality of life, allowed him to start walking again, up to 8 miles daily, and to feel comfortable again going out in public settings.

DISCUSSION

Bariatric surgeries are an effective method of achieving weight loss and improving obesity-related comorbidities. However, only a small percentage of individuals with obesity are candidates for bariatric surgery. Given the dramatic increase in the prevalence of obesity, other options are needed. Specifically, within the VA, an estimated 80% of veterans are overweight or obese, but only about 500 bariatric surgeries are performed annually.9 With the need for additional weight loss therapies, VA programs are starting to offer endoscopic bariatric procedures as an alternative option. This may be a desirable choice for patients with obesity (BMI > 30), with or without associated metabolic comorbidities, who need more aggressive intervention beyond dietary and lifestyle changes and are either not interested in or not eligible for bariatric surgery or weight loss medications.

Although there is evidence that metabolic comorbidities are associated with obesity, there has been less research on obesity and mental health comorbidities such as depression and anxiety. These psychiatric conditions may even be more common among patients seeking weight loss procedures and more prominent in certain groups such as veterans, which may ultimately exclude these patients from bariatric surgery.10 Prior studies suggest that bariatric surgery can reduce the severity of depression and, to a lesser extent, anxiety symptoms at 2 years following the initial surgery; however, there is limited literature describing the impact of weight loss procedure on panic disorders.11-14 We suspect that a weight loss procedure such as ESG may have indirectly improved the veteran’s mood disorder due to the weight loss it induced, increasing the ability to exercise, quality of sleep, and participation in public settings.

This case highlights a veteran who did not tolerate weight loss medication and had severe anxiety and PTSD that prevented him from going through with bariatric surgery. He then underwent an endoscopic weight loss procedure. The ESG helped him successfully achieve significant weight loss, increase his physical activity, reduce his anxiety and panic disorder, and overall, significantly improve his quality of life. More than 1 year after the procedure, the patient has sustained improvements in his psychiatric and emotional health along with durable weight loss, maintaining > 15% of his total weight lost. Additional studies are needed to further understand the prevalence and long-term outcomes of mental health comorbidities, as well as weight loss outcomes in this group of patients who undergo endoscopic bariatric procedures.

CONCLUSIONS

We describe a case of a veteran with severe obesity and significant psychiatric comorbidities that prevented him from undergoing bariatric surgery, who underwent an ESG. This procedure led to significant weight loss, improvement of metabolic parameters, reduction in anxiety and PTSD, and enhancement of his quality of life. This case emphasizes the unique advantages of ESG and supports the expansion of endoscopic bariatric programs in the VA.

- Ritchie SA, Connell JM. The link between abdominal obesity, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2007;17(4):319-326. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2006.07.005

- Bray GA, Kim KK, Wilding JPH; World Obesity Federation. Obesity: a chronic relapsing progressive disease process. A position statement of the World Obesity Federation. Obes Rev. 2017;18(7):715-723. doi:10.1111/obr.12551

- Imbus JR, Voils CI, Funk LM. Bariatric surgery barriers: a review using andersen’s model of health services use. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14(3):404-412. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2017.11.012

- Dawes AJ, Maggard-Gibbons M, Maher AR, et al. Mental health conditions among patients seeking and undergoing bariatric surgery: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;315(2):150- 163. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.18118

- Abu Dayyeh BK, Bazerbachi F, Vargas EJ, et al.. Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty for treatment of class 1 and 2 obesity (MERIT): a prospective, multicentre, randomised trial. Lancet. 2022;400(10350):441-451. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01280-6

- Matteo MV, Bove V, Ciasca G, et al. Success predictors of endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty. Obes Surg. 2024;34(5):1496-1504. doi:10.1007/s11695-024-07109-4

- Maselli DB, Hoff AC, Kucera A, et al. Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty in class III obesity: efficacy, safety, and durability outcomes in 404 consecutive patients. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;15(6):469-479. doi:10.4253/wjge.v15.i6.469

- Kumar N, Abu Dayyeh BK, Lopez-Nava Breviere G, et al. Endoscopic sutured gastroplasty: procedure evolution from first-in-man cases through current technique. Surg Endosc. 2018;32(4):2159-2164. doi:10.1007/s00464-017-5869-2

- Maggard-Gibbons M, Shekelle PG, Girgis MD, et al. Endoscopic Bariatric Interventions versus lifestyle interventions or surgery for weight loss in patients with obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Department of Veterans Affairs (US); 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK587943/

- Maggard Gibbons MA, Maher AM, Dawes AJ, et al. Psychological clearance for bariatric surgery: a systematic review. VA-ESP project #05-2262014.

- van Hout GC, Verschure SK, van Heck GL. Psychosocial predictors of success following bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2005;15(4):552-560. doi:10.1381/0960892053723484

- Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG Jr, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(3):348-358. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040

- Aylward L, Lilly C, Konsor M, et al. How soon do depression and anxiety symptoms improve after bariatric surgery?. Healthcare (Basel). 2023;11(6):862. doi:10.3390/healthcare11060862

- Law S, Dong S, Zhou F, Zheng D, Wang C, Dong Z. Bariatric surgery and mental health outcomes: an umbrella review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1283621. doi:10.3389/fendo.2023.1283621

Obesity is a growing worldwide epidemic with significant implications for individual health and public health care costs. It is also associated with several medical conditions, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and mental health disorders.1 Comprehensive lifestyle intervention is a first-line therapy for obesity consisting of dietary and exercise interventions. Despite initial success, long-term results and durability of weight loss with lifestyle modifications are limited. 2 Bariatric surgery, including sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass surgery, is a more invasive approach that is highly effective in weight loss. However, these operations are not reversible, and patients may not be eligible for or may not desire surgery. Overall, bariatric surgery is widely underutilized, with < 1% of eligible patients ultimately undergoing surgery.3,4

Endoscopic bariatric therapies are increasingly popular procedures that address the need for additional treatments for obesity among individuals who have not had success with lifestyle changes and are not surgical candidates. The most common procedure is the endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty (ESG), which applies full-thickness sutures in the stomach to reduce gastric volume, delay gastric emptying, and limit food intake while keeping the fundus intact compared with sleeve gastrectomy. This procedure is typically considered in patients with body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30, who do not qualify for or do not want traditional bariatric surgery. The literature supports robust outcomes after ESG, with studies demonstrating significant and sustained total body weight loss of up to 14% to 16% at 5 years and significant improvement in ≥ 1 metabolic comorbidities in 80% of patients.5,6 ESG adverse events (AEs) include abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting that are typically self-limited to 1 week. Rarer but more serious AEs include bleeding, perforation, or infection, and occur in 2% of cases based on large trial data.5,7

Although the weight loss benefits of ESG are well established, to date, there are limited data on the effects of endoscopic bariatric therapies like ESG on mental health conditions. Here, we describe a case of a veteran with a history of mental health disorders that prevented him from completing bariatric surgery. The patient underwent ESG and had a successful clinical course.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 59-year-old male veteran with a medical history of class III obesity (42.4 BMI), obstructive sleep apnea, hypothyroidism, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and a large ventral hernia was referred to the MOVE! (Management of Overweight/ Obese Veterans Everywhere!) multidisciplinary high-intensity weight loss program at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) West Los Angeles VA Medical Center (WLAVAMC). His psychiatric history included generalized anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and panic disorder, managed by the Psychiatry Service and treated with sertraline 25 mg daily, lorazepam 0.5 mg twice daily, and hydroxyzine 20 mg nightly. He had previously implemented lifestyle changes and attended MOVE! classes and nutrition coaching for 1 year but was unsuccessful in losing weight. He had also tried liraglutide 3 mg daily for weight loss but was unable to tolerate it and reported worsening medication-related anxiety.

The patient declined further weight loss pharmacotherapy and was referred to bariatric surgery. He was scheduled for a surgical sleeve gastrectomy. However, on the day he arrived at the hospital for surgery, he developed severe anxiety and had a panic attack, and it was canceled. Due to his mental health issues, he was no longer comfortable proceeding with surgery and was left without other options for obesity treatment. The veteran was extremely disappointed because the ventral hernia caused significant quality of life impairment, limited his ability to exercise, and caused him embarrassment in public settings. The hernia could not be surgically repaired until there was significant weight loss.

A bariatric endoscopy program within the Division of Gastroenterology was developed and implemented at the WLAVAMC in February 2023 in conjunction with MOVE! The patient was referred for consideration of an endoscopic weight loss procedure. He was determined to be a suitable candidate for ESG based on his BMI being > 40 and personal preference not to proceed with surgery to lose enough weight to qualify for hernia repair. The veteran underwent an endoscopy, which showed normal anatomy and gastric mucosa. ESG was performed in standard fashion (Figure).8 Three vertical lines were made using argon plasma coagulation from the incisura to 2 cm below the gastroesophageal junction along the anterior, posterior, and greater curvature of the stomach to mark the area for endoscopic suture placement. Starting at the incisura, 7 full-thickness sutures were placed to create a volume reduction plication, with preservation of the fundus. The patient did well postprocedure with no immediate or delayed AEs and was discharged home the same day.

Follow-up

The veteran followed a gradual dietary advancement from a clear liquid diet to pureed and soft texture food. The patient’s weight dropped from 359 lbs preprocedure to 304 lbs 6 months postprocedure, a total body weight loss (TWBL) of 15.3%. At 12 months the veteran weighed 299 lbs (16.7% TBWL). He also had notable improvements in metabolic parameters. His systolic blood pressure decreased from ≥ 140 mm Hg to 120 to 130 mm Hg and hemoglobin A1c dropped from 7.0% to 6.3%. Remarkably, his psychiatrist noted significant improvement in his overall mental health. The veteran reported complete cessation of panic attacks since the ESG, improvements in PTSD and anxiety, and was able to discontinue lorazepam and decrease his dose of sertraline to 12.5 mg daily. He reported feeling more energetic and goal-oriented with increased clarity of thought. Perhaps the most significant outcome was that after the 55-lb weight loss at 6 months, the patient was eligible to undergo ventral hernia surgical repair, which had previously contributed to shame and social isolation. This, in turn, improved his quality of life, allowed him to start walking again, up to 8 miles daily, and to feel comfortable again going out in public settings.

DISCUSSION

Bariatric surgeries are an effective method of achieving weight loss and improving obesity-related comorbidities. However, only a small percentage of individuals with obesity are candidates for bariatric surgery. Given the dramatic increase in the prevalence of obesity, other options are needed. Specifically, within the VA, an estimated 80% of veterans are overweight or obese, but only about 500 bariatric surgeries are performed annually.9 With the need for additional weight loss therapies, VA programs are starting to offer endoscopic bariatric procedures as an alternative option. This may be a desirable choice for patients with obesity (BMI > 30), with or without associated metabolic comorbidities, who need more aggressive intervention beyond dietary and lifestyle changes and are either not interested in or not eligible for bariatric surgery or weight loss medications.

Although there is evidence that metabolic comorbidities are associated with obesity, there has been less research on obesity and mental health comorbidities such as depression and anxiety. These psychiatric conditions may even be more common among patients seeking weight loss procedures and more prominent in certain groups such as veterans, which may ultimately exclude these patients from bariatric surgery.10 Prior studies suggest that bariatric surgery can reduce the severity of depression and, to a lesser extent, anxiety symptoms at 2 years following the initial surgery; however, there is limited literature describing the impact of weight loss procedure on panic disorders.11-14 We suspect that a weight loss procedure such as ESG may have indirectly improved the veteran’s mood disorder due to the weight loss it induced, increasing the ability to exercise, quality of sleep, and participation in public settings.

This case highlights a veteran who did not tolerate weight loss medication and had severe anxiety and PTSD that prevented him from going through with bariatric surgery. He then underwent an endoscopic weight loss procedure. The ESG helped him successfully achieve significant weight loss, increase his physical activity, reduce his anxiety and panic disorder, and overall, significantly improve his quality of life. More than 1 year after the procedure, the patient has sustained improvements in his psychiatric and emotional health along with durable weight loss, maintaining > 15% of his total weight lost. Additional studies are needed to further understand the prevalence and long-term outcomes of mental health comorbidities, as well as weight loss outcomes in this group of patients who undergo endoscopic bariatric procedures.

CONCLUSIONS

We describe a case of a veteran with severe obesity and significant psychiatric comorbidities that prevented him from undergoing bariatric surgery, who underwent an ESG. This procedure led to significant weight loss, improvement of metabolic parameters, reduction in anxiety and PTSD, and enhancement of his quality of life. This case emphasizes the unique advantages of ESG and supports the expansion of endoscopic bariatric programs in the VA.

Obesity is a growing worldwide epidemic with significant implications for individual health and public health care costs. It is also associated with several medical conditions, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and mental health disorders.1 Comprehensive lifestyle intervention is a first-line therapy for obesity consisting of dietary and exercise interventions. Despite initial success, long-term results and durability of weight loss with lifestyle modifications are limited. 2 Bariatric surgery, including sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass surgery, is a more invasive approach that is highly effective in weight loss. However, these operations are not reversible, and patients may not be eligible for or may not desire surgery. Overall, bariatric surgery is widely underutilized, with < 1% of eligible patients ultimately undergoing surgery.3,4

Endoscopic bariatric therapies are increasingly popular procedures that address the need for additional treatments for obesity among individuals who have not had success with lifestyle changes and are not surgical candidates. The most common procedure is the endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty (ESG), which applies full-thickness sutures in the stomach to reduce gastric volume, delay gastric emptying, and limit food intake while keeping the fundus intact compared with sleeve gastrectomy. This procedure is typically considered in patients with body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30, who do not qualify for or do not want traditional bariatric surgery. The literature supports robust outcomes after ESG, with studies demonstrating significant and sustained total body weight loss of up to 14% to 16% at 5 years and significant improvement in ≥ 1 metabolic comorbidities in 80% of patients.5,6 ESG adverse events (AEs) include abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting that are typically self-limited to 1 week. Rarer but more serious AEs include bleeding, perforation, or infection, and occur in 2% of cases based on large trial data.5,7

Although the weight loss benefits of ESG are well established, to date, there are limited data on the effects of endoscopic bariatric therapies like ESG on mental health conditions. Here, we describe a case of a veteran with a history of mental health disorders that prevented him from completing bariatric surgery. The patient underwent ESG and had a successful clinical course.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 59-year-old male veteran with a medical history of class III obesity (42.4 BMI), obstructive sleep apnea, hypothyroidism, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and a large ventral hernia was referred to the MOVE! (Management of Overweight/ Obese Veterans Everywhere!) multidisciplinary high-intensity weight loss program at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) West Los Angeles VA Medical Center (WLAVAMC). His psychiatric history included generalized anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and panic disorder, managed by the Psychiatry Service and treated with sertraline 25 mg daily, lorazepam 0.5 mg twice daily, and hydroxyzine 20 mg nightly. He had previously implemented lifestyle changes and attended MOVE! classes and nutrition coaching for 1 year but was unsuccessful in losing weight. He had also tried liraglutide 3 mg daily for weight loss but was unable to tolerate it and reported worsening medication-related anxiety.

The patient declined further weight loss pharmacotherapy and was referred to bariatric surgery. He was scheduled for a surgical sleeve gastrectomy. However, on the day he arrived at the hospital for surgery, he developed severe anxiety and had a panic attack, and it was canceled. Due to his mental health issues, he was no longer comfortable proceeding with surgery and was left without other options for obesity treatment. The veteran was extremely disappointed because the ventral hernia caused significant quality of life impairment, limited his ability to exercise, and caused him embarrassment in public settings. The hernia could not be surgically repaired until there was significant weight loss.

A bariatric endoscopy program within the Division of Gastroenterology was developed and implemented at the WLAVAMC in February 2023 in conjunction with MOVE! The patient was referred for consideration of an endoscopic weight loss procedure. He was determined to be a suitable candidate for ESG based on his BMI being > 40 and personal preference not to proceed with surgery to lose enough weight to qualify for hernia repair. The veteran underwent an endoscopy, which showed normal anatomy and gastric mucosa. ESG was performed in standard fashion (Figure).8 Three vertical lines were made using argon plasma coagulation from the incisura to 2 cm below the gastroesophageal junction along the anterior, posterior, and greater curvature of the stomach to mark the area for endoscopic suture placement. Starting at the incisura, 7 full-thickness sutures were placed to create a volume reduction plication, with preservation of the fundus. The patient did well postprocedure with no immediate or delayed AEs and was discharged home the same day.

Follow-up

The veteran followed a gradual dietary advancement from a clear liquid diet to pureed and soft texture food. The patient’s weight dropped from 359 lbs preprocedure to 304 lbs 6 months postprocedure, a total body weight loss (TWBL) of 15.3%. At 12 months the veteran weighed 299 lbs (16.7% TBWL). He also had notable improvements in metabolic parameters. His systolic blood pressure decreased from ≥ 140 mm Hg to 120 to 130 mm Hg and hemoglobin A1c dropped from 7.0% to 6.3%. Remarkably, his psychiatrist noted significant improvement in his overall mental health. The veteran reported complete cessation of panic attacks since the ESG, improvements in PTSD and anxiety, and was able to discontinue lorazepam and decrease his dose of sertraline to 12.5 mg daily. He reported feeling more energetic and goal-oriented with increased clarity of thought. Perhaps the most significant outcome was that after the 55-lb weight loss at 6 months, the patient was eligible to undergo ventral hernia surgical repair, which had previously contributed to shame and social isolation. This, in turn, improved his quality of life, allowed him to start walking again, up to 8 miles daily, and to feel comfortable again going out in public settings.

DISCUSSION

Bariatric surgeries are an effective method of achieving weight loss and improving obesity-related comorbidities. However, only a small percentage of individuals with obesity are candidates for bariatric surgery. Given the dramatic increase in the prevalence of obesity, other options are needed. Specifically, within the VA, an estimated 80% of veterans are overweight or obese, but only about 500 bariatric surgeries are performed annually.9 With the need for additional weight loss therapies, VA programs are starting to offer endoscopic bariatric procedures as an alternative option. This may be a desirable choice for patients with obesity (BMI > 30), with or without associated metabolic comorbidities, who need more aggressive intervention beyond dietary and lifestyle changes and are either not interested in or not eligible for bariatric surgery or weight loss medications.

Although there is evidence that metabolic comorbidities are associated with obesity, there has been less research on obesity and mental health comorbidities such as depression and anxiety. These psychiatric conditions may even be more common among patients seeking weight loss procedures and more prominent in certain groups such as veterans, which may ultimately exclude these patients from bariatric surgery.10 Prior studies suggest that bariatric surgery can reduce the severity of depression and, to a lesser extent, anxiety symptoms at 2 years following the initial surgery; however, there is limited literature describing the impact of weight loss procedure on panic disorders.11-14 We suspect that a weight loss procedure such as ESG may have indirectly improved the veteran’s mood disorder due to the weight loss it induced, increasing the ability to exercise, quality of sleep, and participation in public settings.

This case highlights a veteran who did not tolerate weight loss medication and had severe anxiety and PTSD that prevented him from going through with bariatric surgery. He then underwent an endoscopic weight loss procedure. The ESG helped him successfully achieve significant weight loss, increase his physical activity, reduce his anxiety and panic disorder, and overall, significantly improve his quality of life. More than 1 year after the procedure, the patient has sustained improvements in his psychiatric and emotional health along with durable weight loss, maintaining > 15% of his total weight lost. Additional studies are needed to further understand the prevalence and long-term outcomes of mental health comorbidities, as well as weight loss outcomes in this group of patients who undergo endoscopic bariatric procedures.

CONCLUSIONS

We describe a case of a veteran with severe obesity and significant psychiatric comorbidities that prevented him from undergoing bariatric surgery, who underwent an ESG. This procedure led to significant weight loss, improvement of metabolic parameters, reduction in anxiety and PTSD, and enhancement of his quality of life. This case emphasizes the unique advantages of ESG and supports the expansion of endoscopic bariatric programs in the VA.

- Ritchie SA, Connell JM. The link between abdominal obesity, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2007;17(4):319-326. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2006.07.005

- Bray GA, Kim KK, Wilding JPH; World Obesity Federation. Obesity: a chronic relapsing progressive disease process. A position statement of the World Obesity Federation. Obes Rev. 2017;18(7):715-723. doi:10.1111/obr.12551

- Imbus JR, Voils CI, Funk LM. Bariatric surgery barriers: a review using andersen’s model of health services use. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14(3):404-412. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2017.11.012

- Dawes AJ, Maggard-Gibbons M, Maher AR, et al. Mental health conditions among patients seeking and undergoing bariatric surgery: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;315(2):150- 163. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.18118

- Abu Dayyeh BK, Bazerbachi F, Vargas EJ, et al.. Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty for treatment of class 1 and 2 obesity (MERIT): a prospective, multicentre, randomised trial. Lancet. 2022;400(10350):441-451. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01280-6

- Matteo MV, Bove V, Ciasca G, et al. Success predictors of endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty. Obes Surg. 2024;34(5):1496-1504. doi:10.1007/s11695-024-07109-4

- Maselli DB, Hoff AC, Kucera A, et al. Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty in class III obesity: efficacy, safety, and durability outcomes in 404 consecutive patients. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;15(6):469-479. doi:10.4253/wjge.v15.i6.469

- Kumar N, Abu Dayyeh BK, Lopez-Nava Breviere G, et al. Endoscopic sutured gastroplasty: procedure evolution from first-in-man cases through current technique. Surg Endosc. 2018;32(4):2159-2164. doi:10.1007/s00464-017-5869-2

- Maggard-Gibbons M, Shekelle PG, Girgis MD, et al. Endoscopic Bariatric Interventions versus lifestyle interventions or surgery for weight loss in patients with obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Department of Veterans Affairs (US); 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK587943/

- Maggard Gibbons MA, Maher AM, Dawes AJ, et al. Psychological clearance for bariatric surgery: a systematic review. VA-ESP project #05-2262014.

- van Hout GC, Verschure SK, van Heck GL. Psychosocial predictors of success following bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2005;15(4):552-560. doi:10.1381/0960892053723484

- Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG Jr, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(3):348-358. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040

- Aylward L, Lilly C, Konsor M, et al. How soon do depression and anxiety symptoms improve after bariatric surgery?. Healthcare (Basel). 2023;11(6):862. doi:10.3390/healthcare11060862

- Law S, Dong S, Zhou F, Zheng D, Wang C, Dong Z. Bariatric surgery and mental health outcomes: an umbrella review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1283621. doi:10.3389/fendo.2023.1283621

- Ritchie SA, Connell JM. The link between abdominal obesity, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2007;17(4):319-326. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2006.07.005

- Bray GA, Kim KK, Wilding JPH; World Obesity Federation. Obesity: a chronic relapsing progressive disease process. A position statement of the World Obesity Federation. Obes Rev. 2017;18(7):715-723. doi:10.1111/obr.12551

- Imbus JR, Voils CI, Funk LM. Bariatric surgery barriers: a review using andersen’s model of health services use. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14(3):404-412. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2017.11.012

- Dawes AJ, Maggard-Gibbons M, Maher AR, et al. Mental health conditions among patients seeking and undergoing bariatric surgery: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;315(2):150- 163. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.18118

- Abu Dayyeh BK, Bazerbachi F, Vargas EJ, et al.. Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty for treatment of class 1 and 2 obesity (MERIT): a prospective, multicentre, randomised trial. Lancet. 2022;400(10350):441-451. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01280-6

- Matteo MV, Bove V, Ciasca G, et al. Success predictors of endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty. Obes Surg. 2024;34(5):1496-1504. doi:10.1007/s11695-024-07109-4

- Maselli DB, Hoff AC, Kucera A, et al. Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty in class III obesity: efficacy, safety, and durability outcomes in 404 consecutive patients. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;15(6):469-479. doi:10.4253/wjge.v15.i6.469

- Kumar N, Abu Dayyeh BK, Lopez-Nava Breviere G, et al. Endoscopic sutured gastroplasty: procedure evolution from first-in-man cases through current technique. Surg Endosc. 2018;32(4):2159-2164. doi:10.1007/s00464-017-5869-2

- Maggard-Gibbons M, Shekelle PG, Girgis MD, et al. Endoscopic Bariatric Interventions versus lifestyle interventions or surgery for weight loss in patients with obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Department of Veterans Affairs (US); 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK587943/

- Maggard Gibbons MA, Maher AM, Dawes AJ, et al. Psychological clearance for bariatric surgery: a systematic review. VA-ESP project #05-2262014.

- van Hout GC, Verschure SK, van Heck GL. Psychosocial predictors of success following bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2005;15(4):552-560. doi:10.1381/0960892053723484

- Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG Jr, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(3):348-358. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040

- Aylward L, Lilly C, Konsor M, et al. How soon do depression and anxiety symptoms improve after bariatric surgery?. Healthcare (Basel). 2023;11(6):862. doi:10.3390/healthcare11060862

- Law S, Dong S, Zhou F, Zheng D, Wang C, Dong Z. Bariatric surgery and mental health outcomes: an umbrella review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1283621. doi:10.3389/fendo.2023.1283621

Endoscopic Sleeve Gastroplasty is an Effective Treatment for Obesity in a Veteran With Metabolic and Psychiatric Comorbidities

Endoscopic Sleeve Gastroplasty is an Effective Treatment for Obesity in a Veteran With Metabolic and Psychiatric Comorbidities

Single-Incision Robotic Surgery Exhibits Safety, Feasibility in Colorectal Cases

Single-Incision Robotic Surgery Exhibits Safety, Feasibility in Colorectal Cases

TOPLINE: A novel single-incision robotic surgery technique for colorectal procedures demonstrated feasibility with 0% conversion to open surgery rate; only 1 case required additional ports. The technique achieved a 30-day all-severity morbidity rate of 20% and major morbidity of 6%.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a retrospective review to report a unique, single-incision robotic surgery technique that uses a fascial wound protector device and multiport robotic surgical system in colorectal surgery.

- Analysis included 50 patients (60% women) with mean ages of 53.5 years and median BMI of 27.2 kg/m2.

- Study was performed at a single quaternary, urban, academic institution from December 2023 to April 2025.

- Patients aged ≥ 18 years with colorectal indications who underwent robotic single-incision surgery using a Da Vinci multiport robotic platform were included.

TAKEAWAY:

- Conversion to open surgery rate was 0%; 1 case required additional robotic ports.

- The 30-day all-severity morbidity rate was 20%; 30-day major morbidity was 6%.

- Pathologies treated included Crohn's disease (26%), diverticulitis (22%), colon cancer (16%), colostomy status (8%), and rectal cancer (4%).

- Successful procedures included right-sided colectomies (14%), left-sided colectomies (28%), total colectomy (4%), rectal resection (4%), small bowel procedures (22%), and ostomy creation/reversal (18%).

IN PRACTICE: "Our rSIS technique utilizing a multiport robotic system is safe and feasible across a wide spectrum of colorectal procedures," wrote the study authors.

LIMITATIONS: According to the authors, reproducible successful completion of surgeries using this technique may be challenging in populations requiring deep pelvic dissections, especially in narrow male pelvis cases, and in patients with very high BMI and significant intra-abdominal adipose tissue.

DISCLOSURES: The authors report no financial support was received for this study and declare no competing interests.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

TOPLINE: A novel single-incision robotic surgery technique for colorectal procedures demonstrated feasibility with 0% conversion to open surgery rate; only 1 case required additional ports. The technique achieved a 30-day all-severity morbidity rate of 20% and major morbidity of 6%.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a retrospective review to report a unique, single-incision robotic surgery technique that uses a fascial wound protector device and multiport robotic surgical system in colorectal surgery.

- Analysis included 50 patients (60% women) with mean ages of 53.5 years and median BMI of 27.2 kg/m2.

- Study was performed at a single quaternary, urban, academic institution from December 2023 to April 2025.

- Patients aged ≥ 18 years with colorectal indications who underwent robotic single-incision surgery using a Da Vinci multiport robotic platform were included.

TAKEAWAY:

- Conversion to open surgery rate was 0%; 1 case required additional robotic ports.

- The 30-day all-severity morbidity rate was 20%; 30-day major morbidity was 6%.

- Pathologies treated included Crohn's disease (26%), diverticulitis (22%), colon cancer (16%), colostomy status (8%), and rectal cancer (4%).

- Successful procedures included right-sided colectomies (14%), left-sided colectomies (28%), total colectomy (4%), rectal resection (4%), small bowel procedures (22%), and ostomy creation/reversal (18%).

IN PRACTICE: "Our rSIS technique utilizing a multiport robotic system is safe and feasible across a wide spectrum of colorectal procedures," wrote the study authors.

LIMITATIONS: According to the authors, reproducible successful completion of surgeries using this technique may be challenging in populations requiring deep pelvic dissections, especially in narrow male pelvis cases, and in patients with very high BMI and significant intra-abdominal adipose tissue.

DISCLOSURES: The authors report no financial support was received for this study and declare no competing interests.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

TOPLINE: A novel single-incision robotic surgery technique for colorectal procedures demonstrated feasibility with 0% conversion to open surgery rate; only 1 case required additional ports. The technique achieved a 30-day all-severity morbidity rate of 20% and major morbidity of 6%.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a retrospective review to report a unique, single-incision robotic surgery technique that uses a fascial wound protector device and multiport robotic surgical system in colorectal surgery.

- Analysis included 50 patients (60% women) with mean ages of 53.5 years and median BMI of 27.2 kg/m2.

- Study was performed at a single quaternary, urban, academic institution from December 2023 to April 2025.

- Patients aged ≥ 18 years with colorectal indications who underwent robotic single-incision surgery using a Da Vinci multiport robotic platform were included.

TAKEAWAY:

- Conversion to open surgery rate was 0%; 1 case required additional robotic ports.

- The 30-day all-severity morbidity rate was 20%; 30-day major morbidity was 6%.

- Pathologies treated included Crohn's disease (26%), diverticulitis (22%), colon cancer (16%), colostomy status (8%), and rectal cancer (4%).

- Successful procedures included right-sided colectomies (14%), left-sided colectomies (28%), total colectomy (4%), rectal resection (4%), small bowel procedures (22%), and ostomy creation/reversal (18%).

IN PRACTICE: "Our rSIS technique utilizing a multiport robotic system is safe and feasible across a wide spectrum of colorectal procedures," wrote the study authors.

LIMITATIONS: According to the authors, reproducible successful completion of surgeries using this technique may be challenging in populations requiring deep pelvic dissections, especially in narrow male pelvis cases, and in patients with very high BMI and significant intra-abdominal adipose tissue.

DISCLOSURES: The authors report no financial support was received for this study and declare no competing interests.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

Single-Incision Robotic Surgery Exhibits Safety, Feasibility in Colorectal Cases

Single-Incision Robotic Surgery Exhibits Safety, Feasibility in Colorectal Cases

Preoperative Diabetes Management for Patients Undergoing Elective Surgeries at a Veterans Affairs Medical Center

Preoperative Diabetes Management for Patients Undergoing Elective Surgeries at a Veterans Affairs Medical Center

More than 38 million people in the United States (12%) have diabetes mellitus (DM), though 1 in 5 are unaware they have DM.1 The prevalence among veterans is even more substantial, impacting nearly 25% of those who received care from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).2 DM can lead to increased health care costs in addition to various complications (eg, cardiovascular, renal), especially if left uncontrolled.1,3 similar impact is found in the perioperative period (defined as at or around the time of an operation), as multiple studies have found that uncontrolled preoperative DM can result in worsened surgical outcomes, including longer hospital stays, more infectious complications, and higher perioperative mortality.4-6

In contrast, adequate glycemic control assessed with blood glucose levels has been shown to decrease the incidence of postoperative infections.7 Optimizing glycemic control during hospital stays, especially postsurgery, has become the standard of care, with most health systems establishing specific protocols. In current literature, most studies examining DM management in the perioperative period are focused on postoperative care, with little attention to the preoperative period.4,6,7

One study found that patients with poor presurgery glycemic control assessed by hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels were more likely to remain hyperglycemic during and after surgery. 8 Blood glucose levels < 200 mg/dL can lead to an increased risk of infection and impaired wound healing, meaning a well-controlled HbA1c before a procedure serves as a potential factor for success.9 The 2025 American Diabetes Association (ADA) Standards of Care (SOC) recommendation is to target HbA1c < 8% whenever possible, and some health systems require lower levels (eg, < 7% or 7.5%).10 With that goal in mind and knowing that preoperative hyperglycemia has been shown to be a contributing factor in the delay or cancellation of surgical cases, an argument can be made that attention to preoperative DM management also should be a focus for health care systems performing surgeries.8,9,11

Attention to glucose control during preoperative care offers an opportunity to screen for DM in patients who may not have been screened otherwise and to standardize perioperative DM management. Since DM disproportionately impacts veterans, this is a pertinent issue to the VA. Veterans can be more susceptible to complications if DM is left uncontrolled prior to surgery. To determine readiness for surgery and control of comorbid conditions such as DM before a planned surgery, facilities often perform a preoperative clinic assessment, often in a multidisciplinary clinic.

At Veteran Health Indiana (VHI), a presurgery clinic visit involving the primary surgery service (physician, nurse practitioner, and/or a physician assistant) is conducted 1 to 2 months prior to the planned procedure to determine whether a patient is ready for surgery. During this visit, patients receive a packet with instructions for various tasks and medications, such as applying topical antibiotic prophylaxis on the anticipated surgical site. This is documented in the form of a note in the VHI Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS). The medication instructions are provided according to the preferences of the surgical team. These may be templated notes that contain general directions on the timing and dosing of specific medications, in addition to instructions for holding or reducing doses when appropriate. The instructions can be tailored by the team conducting the preoperative visit (eg, “Take 20 units of insulin glargine the day before surgery” vs “Take half of your long-acting insulin the night before surgery”). Specific to DM, VHI has a nurse-driven day of surgery glucose assessment where point-of-care blood glucose is collected during preoperative holding for most patients.

There is limited research assessing the level of preoperative glycemic control and the incidence of complications in a veteran population. The objective of this study was to gain a baseline understanding of what, if any, standardization exists for preoperative instructions for DM medications and to assess the level of preoperative glycemic control and postoperative complications in patients with DM undergoing major elective surgical procedures.

Methods

This retrospective, single-center chart review was conducted at VHI. The Indiana University and VHI institutional review boards determined that this quality improvement project was exempt from review.

The primary outcome was the number of patients with surgical procedures delayed or canceled due to hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia. Hyperglycemia was defined as blood glucose > 180 mg/dL and hypoglycemia was defined as < 70 mg/dL, slight variations from the current ADA SOC preoperative specific recommendation of a blood glucose reading of 100 to 180 mg/dL within 4 hours of surgery.10 The standard outpatient hypoglycemia definition of blood glucose < 70 mg/dL was chosen because the current goal (< 100 mg/dL) was not the standard in previous ADA SOCs that were in place during the study period. Specifically, the 2018 ADA SOC did not provide preoperative recommendations and the 2019-2021 ADA SOC recommended 80 to 180 mg/dL.10,12-18 For patients who had multiple preoperative blood glucose measurements, the first recorded glucose on the day of the procedure was used.

The secondary outcomes of this study were focused on the preoperative process/care at VHI and postoperative glycemic control. The preoperative process included examining whether medication instructions were given and their quality. Additionally, the number of interventions for hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia were required immediately prior to surgery and the average preoperative HbA1c (measured within 3 months prior to surgery) were collected and analyzed. For postoperative glycemic control, average blood glucose measurements and number of hypoglycemic (< 70 mg/dL) and hyperglycemic (> 180 mg/dL) events were measured in addition to the frequency of changes made at discharge to patients’ DM medication regimens.

The safety outcome of this study assessed commonly observed postoperative complications and was examined up to 30 days postsurgery. These included acute kidney injury (defined using Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes 2012, the standard during the study period), nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, and surgical site infections, which were identified from the discharge summary written by the primary surgery service.19 All-cause mortality also was collected.

Patients were included if they were admitted for major elective surgeries and had a diagnosis of either type 1 or type 2 DM on their problem list, determined by International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes. Major elective surgery was defined as a procedure that would likely result in a hospital admission of > 24 hours. Of note, patients may have been included in this study more than once if they had > 1 procedure at least 30 days apart and met inclusion criteria within the time frame. Patients were excluded if they were taking no DM medications or chronic steroids (at any dose), residing in a long-term care facility, being managed by a non-VA clinician prior to surgery, or missing a preoperative blood glucose measurement.

All data were collected from the CPRS. A list of surgical cases involving patients with DM who were scheduled to undergo major elective surgeries from January 1, 2018, to December 31, 2021, at VHI was generated. The list was randomized to a smaller number (N = 394) for data collection due to the time and resource constraints for a pharmacy residency project. All data were deidentified and stored in a secured VA server to protect patient confidentiality. Descriptive statistics were used for all results.

Results

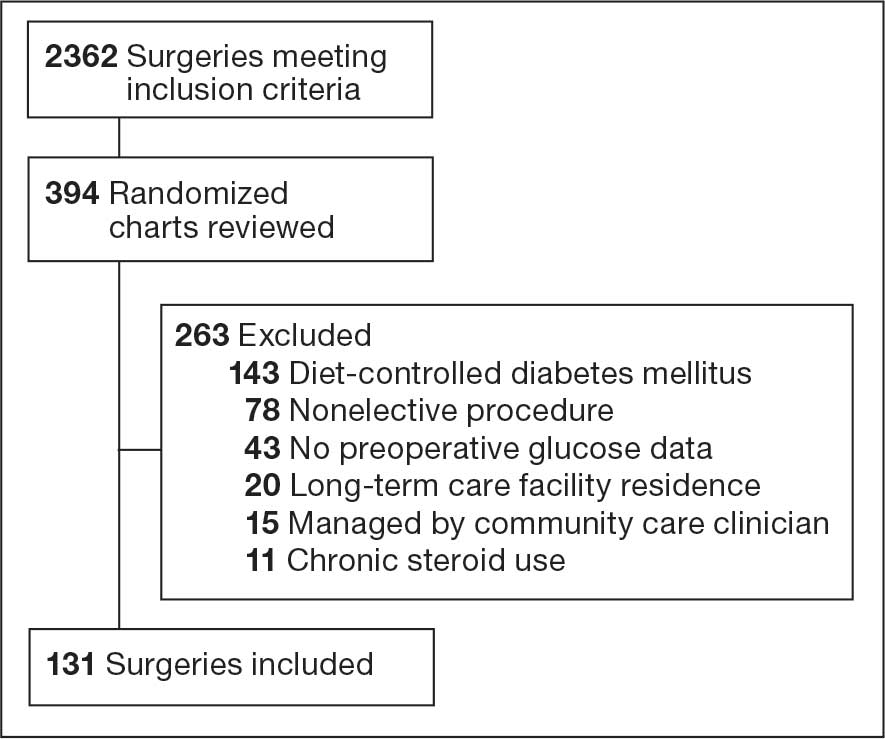

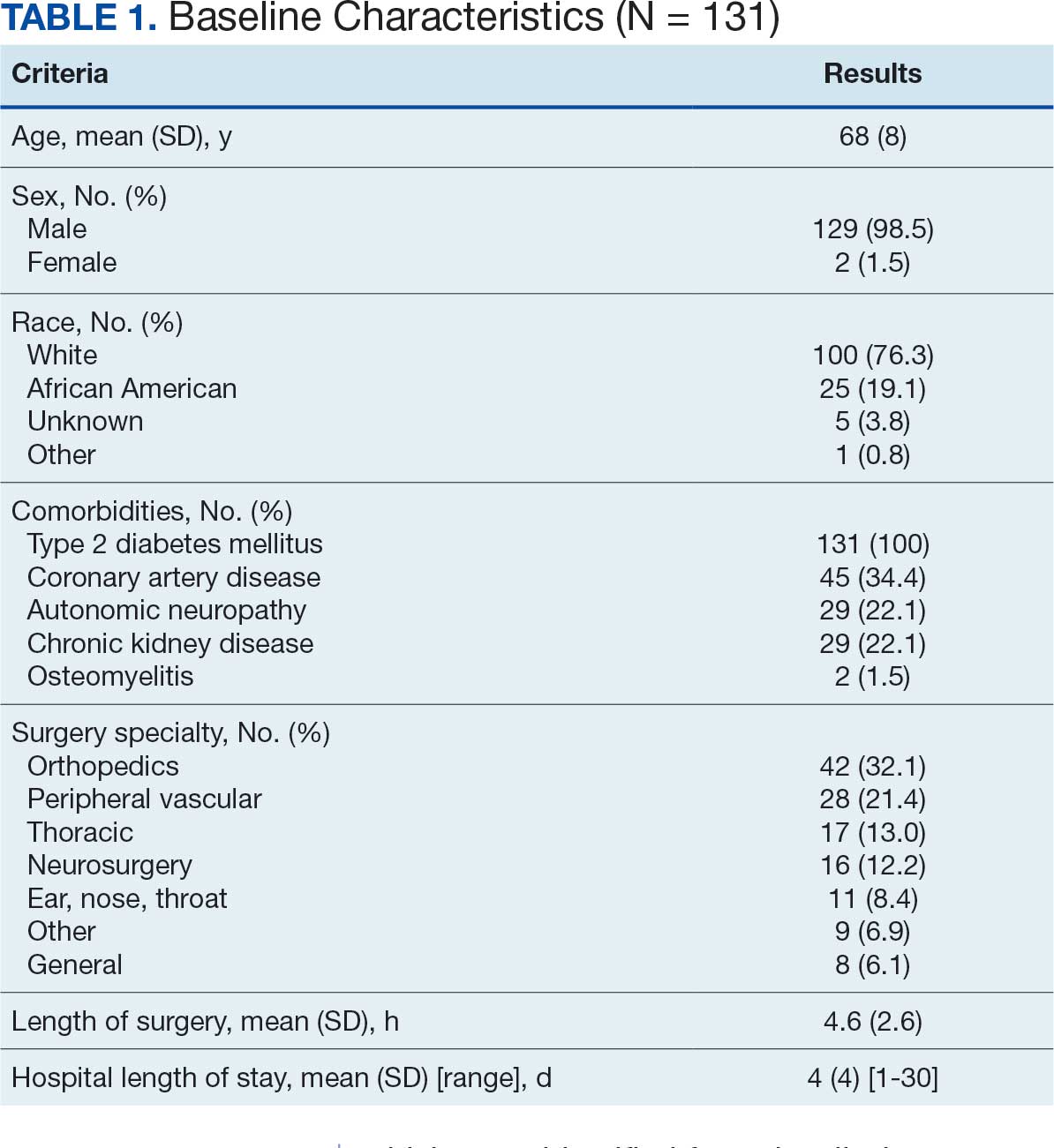

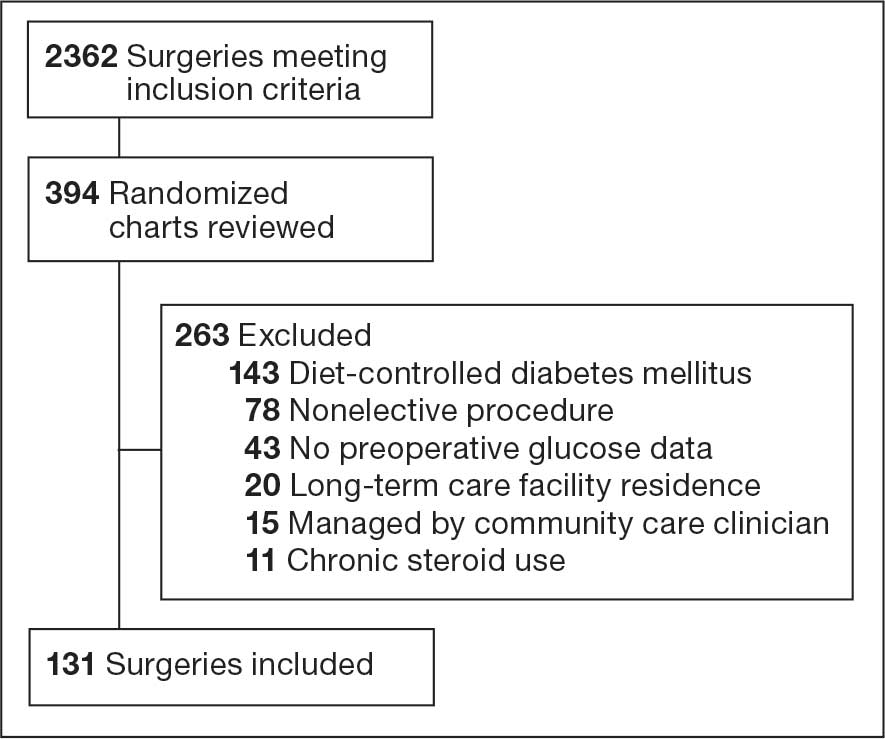

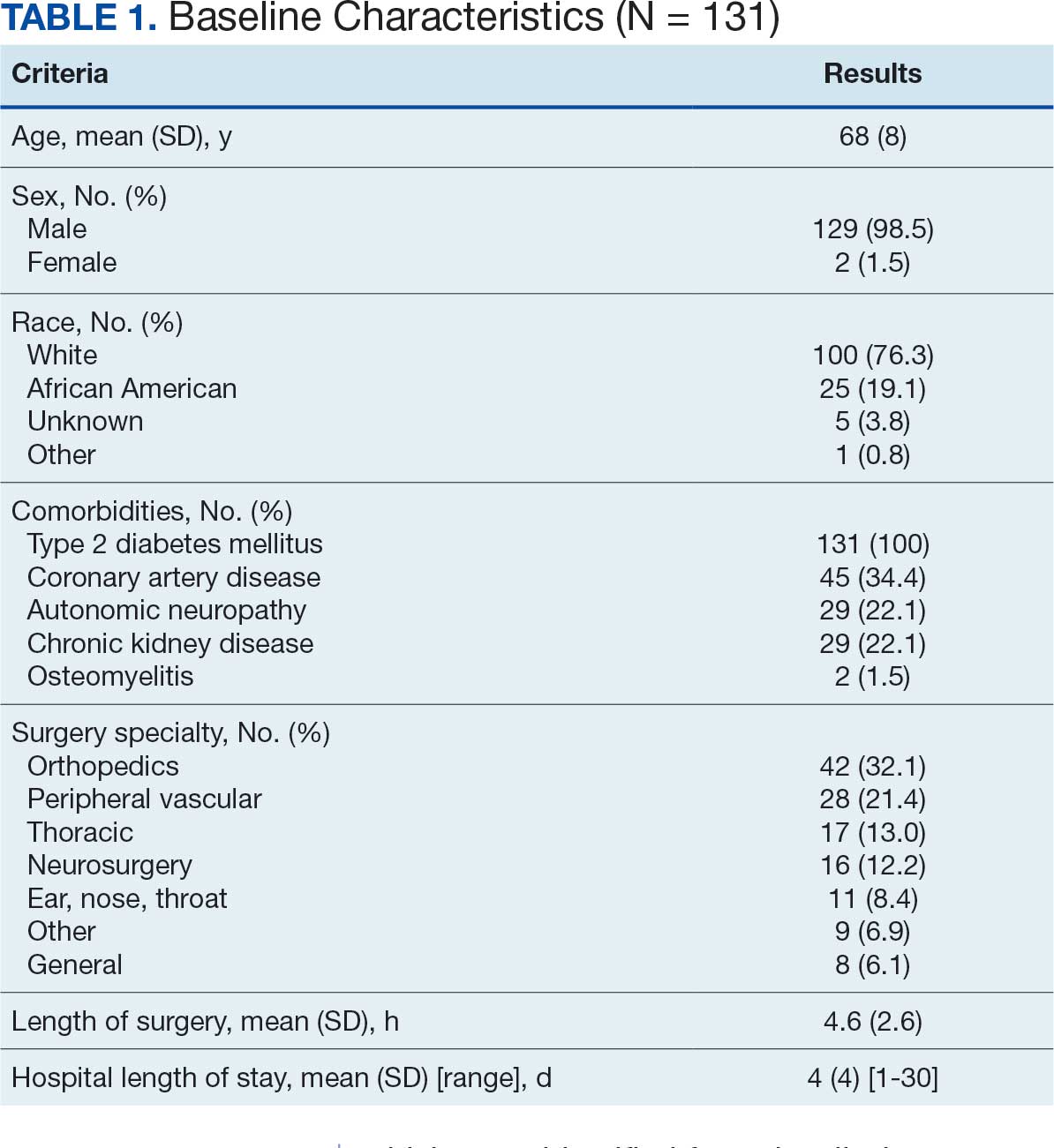

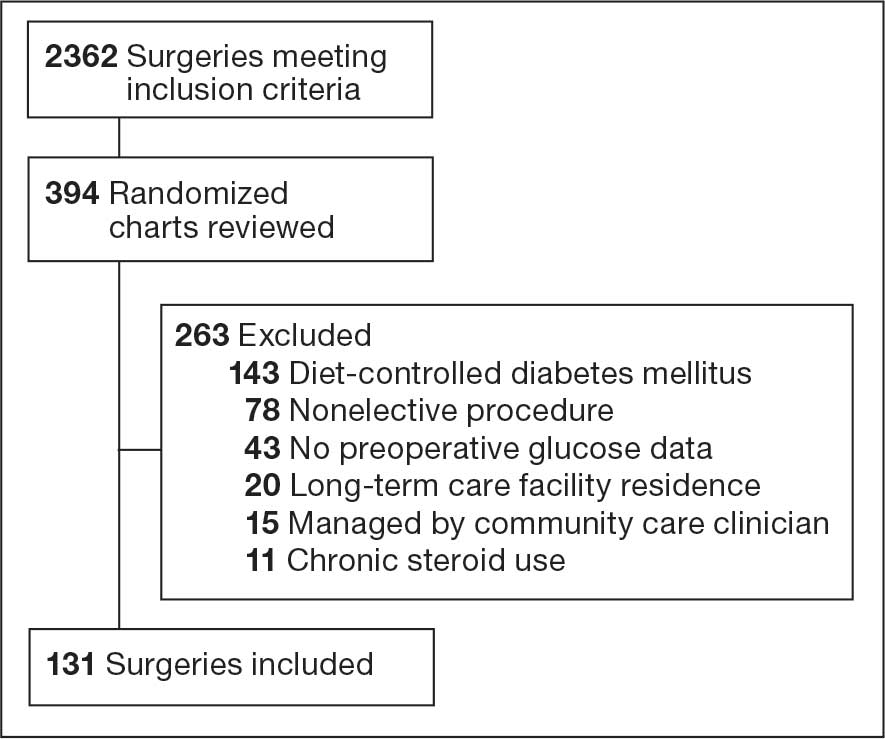

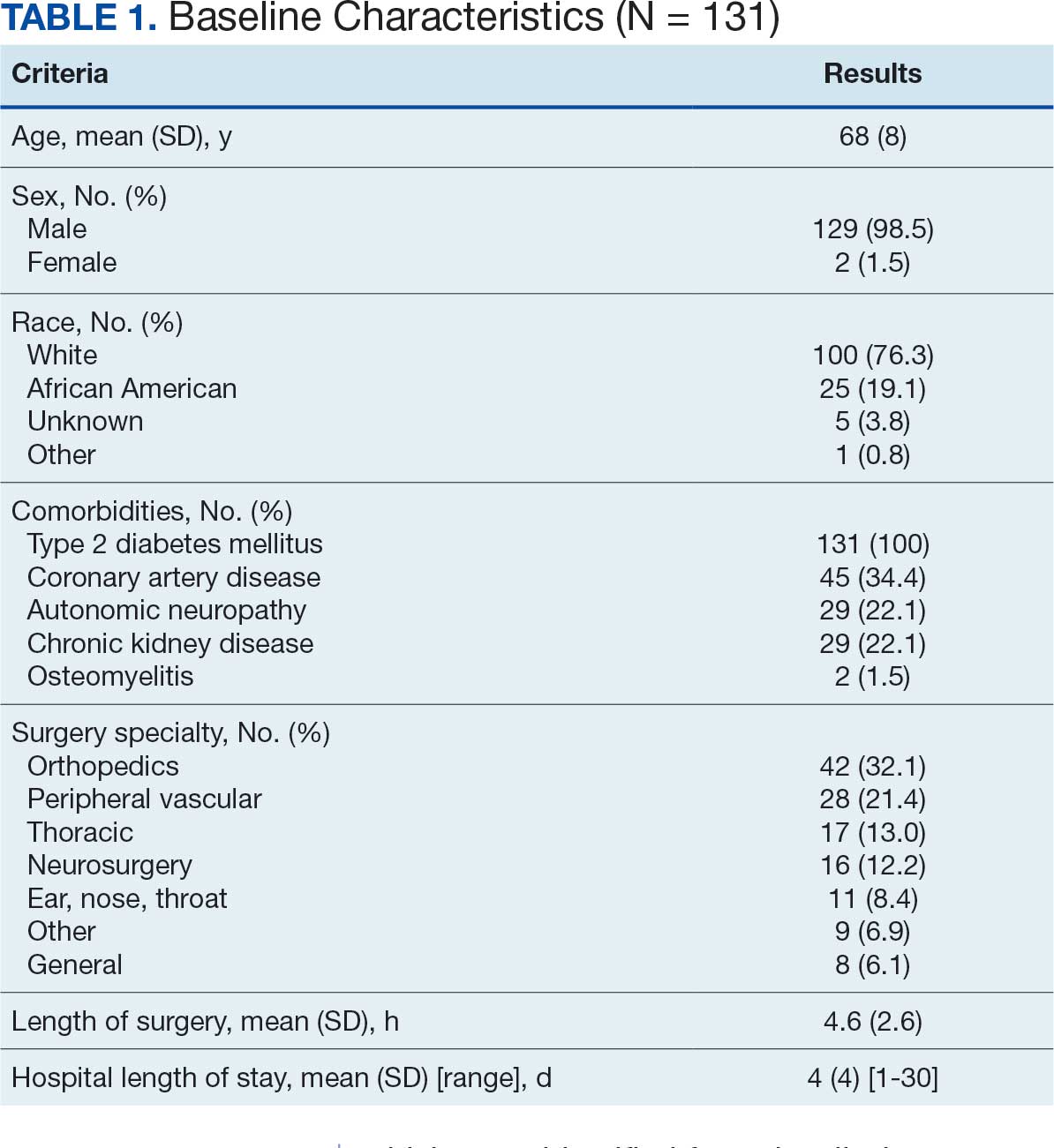

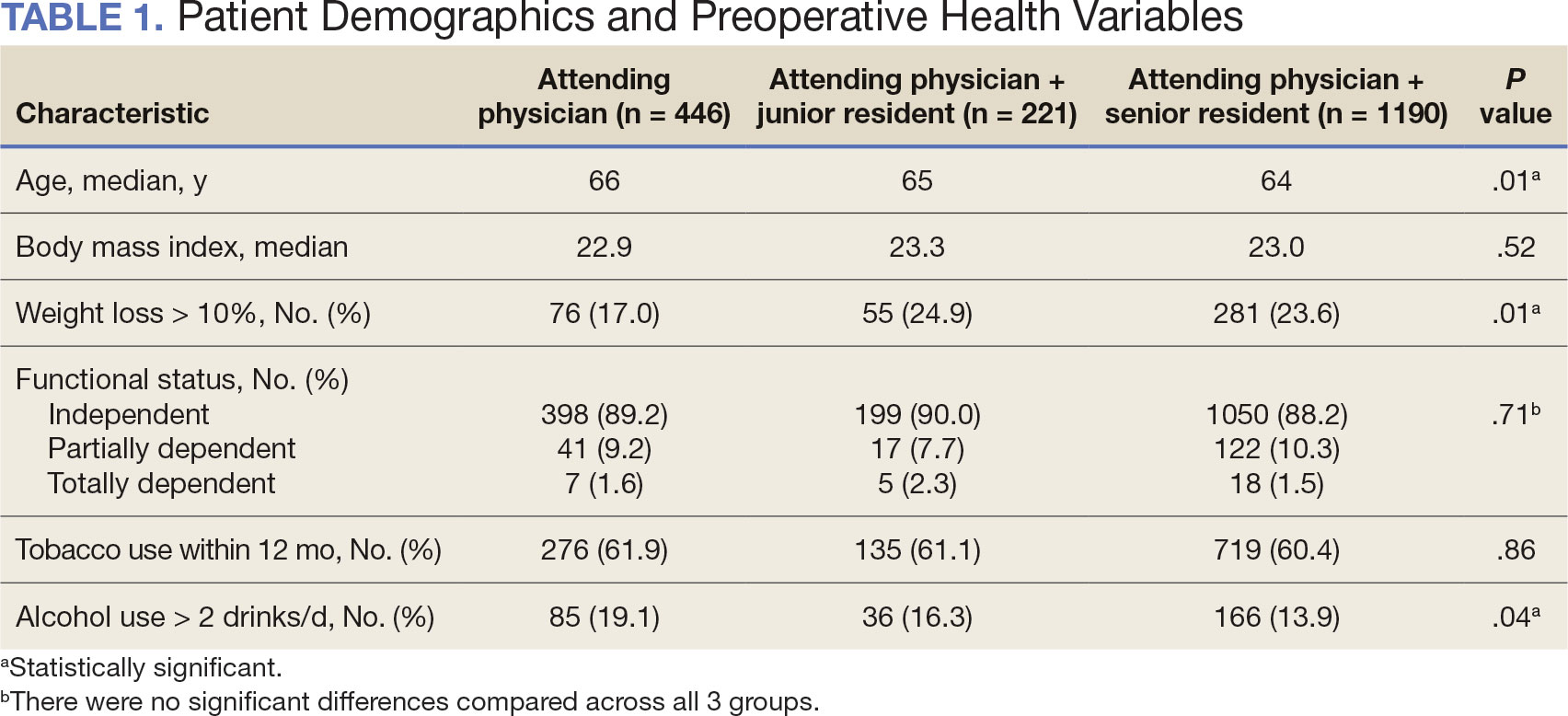

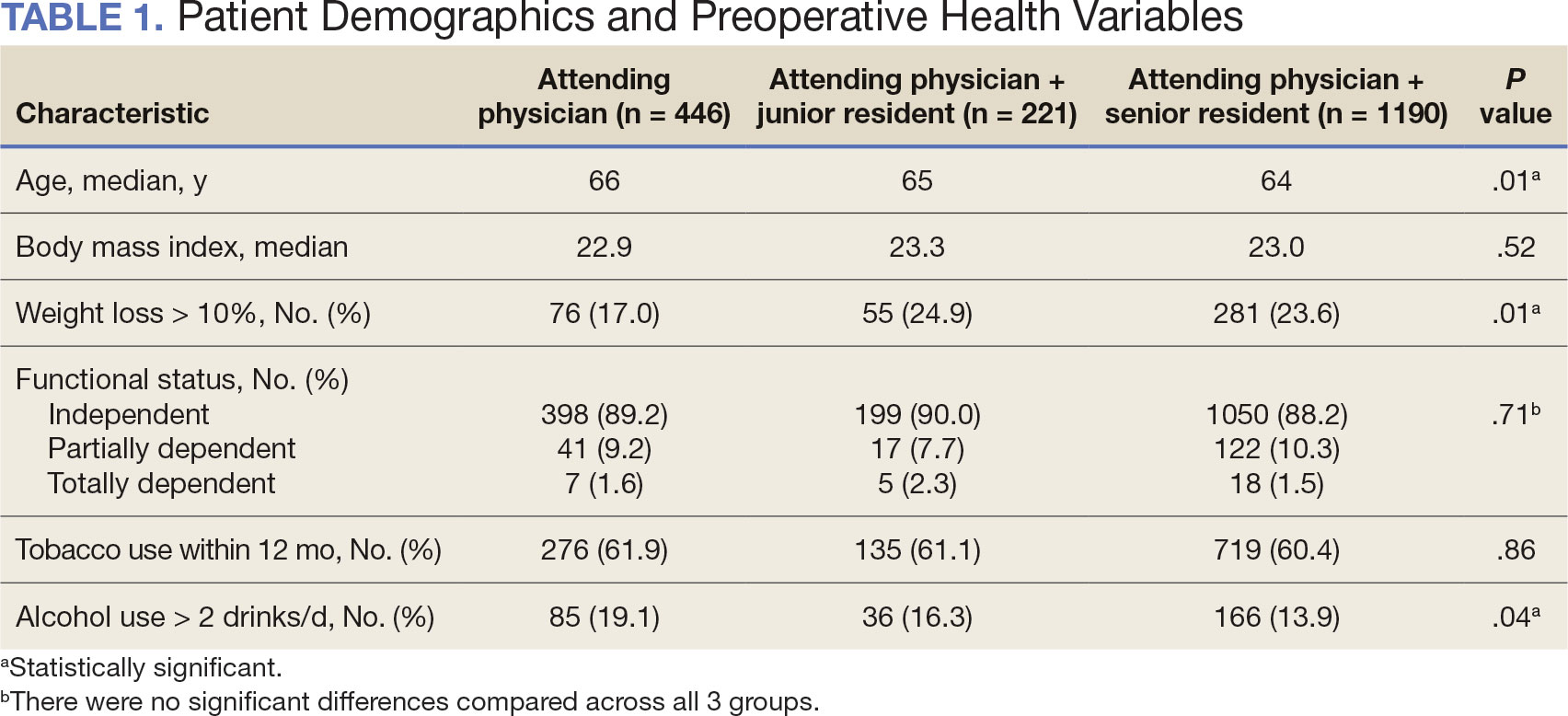

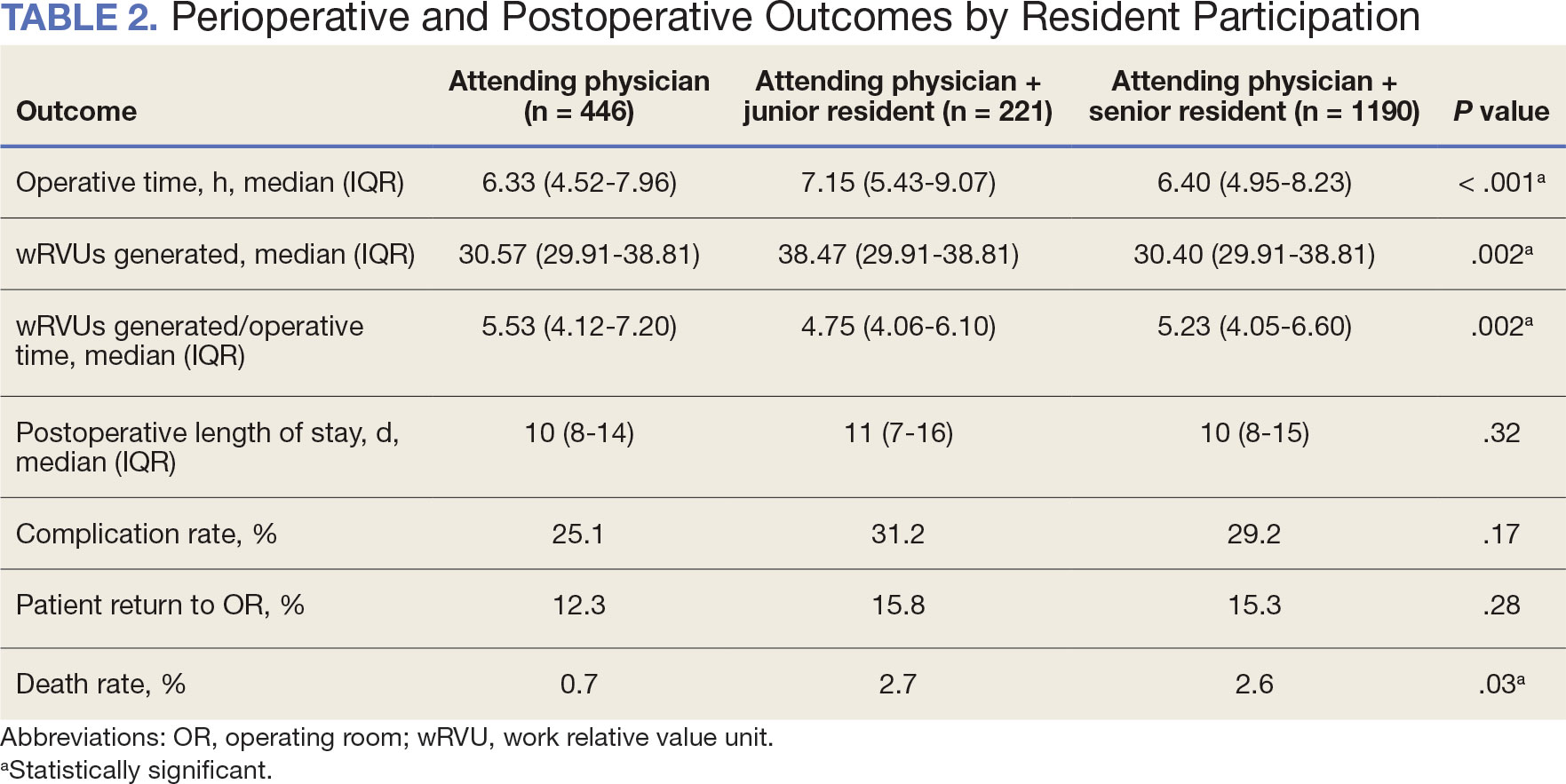

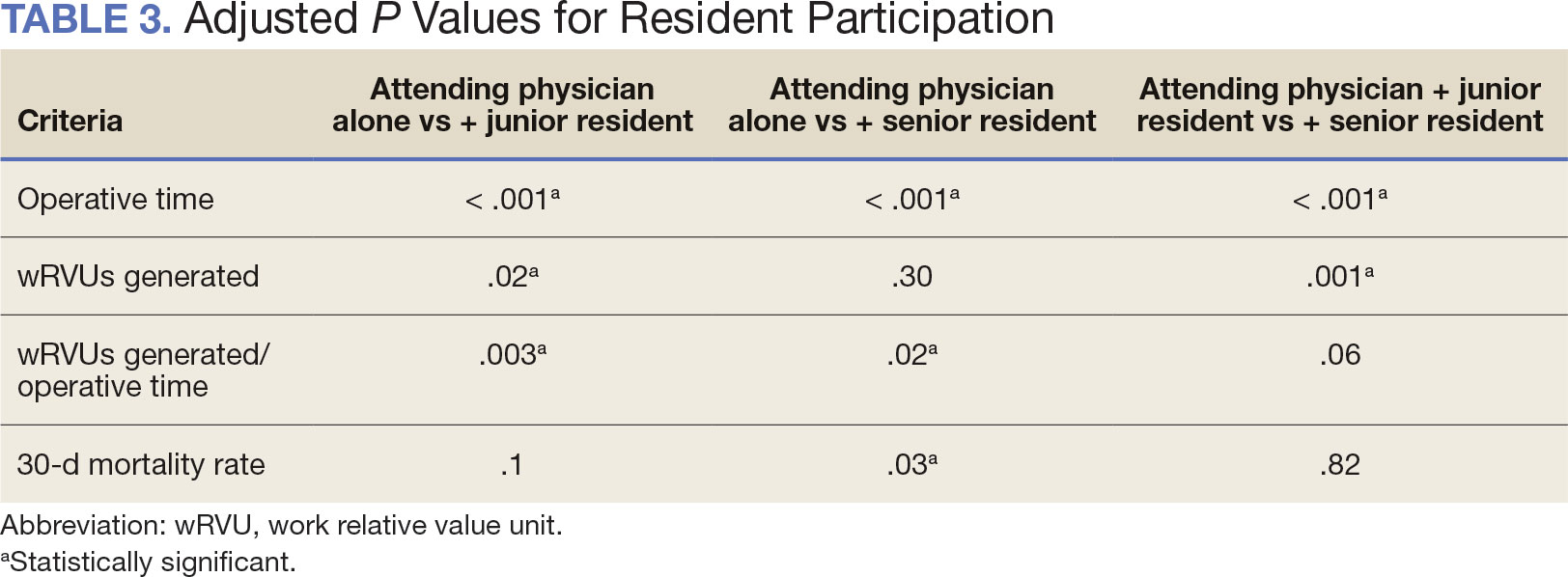

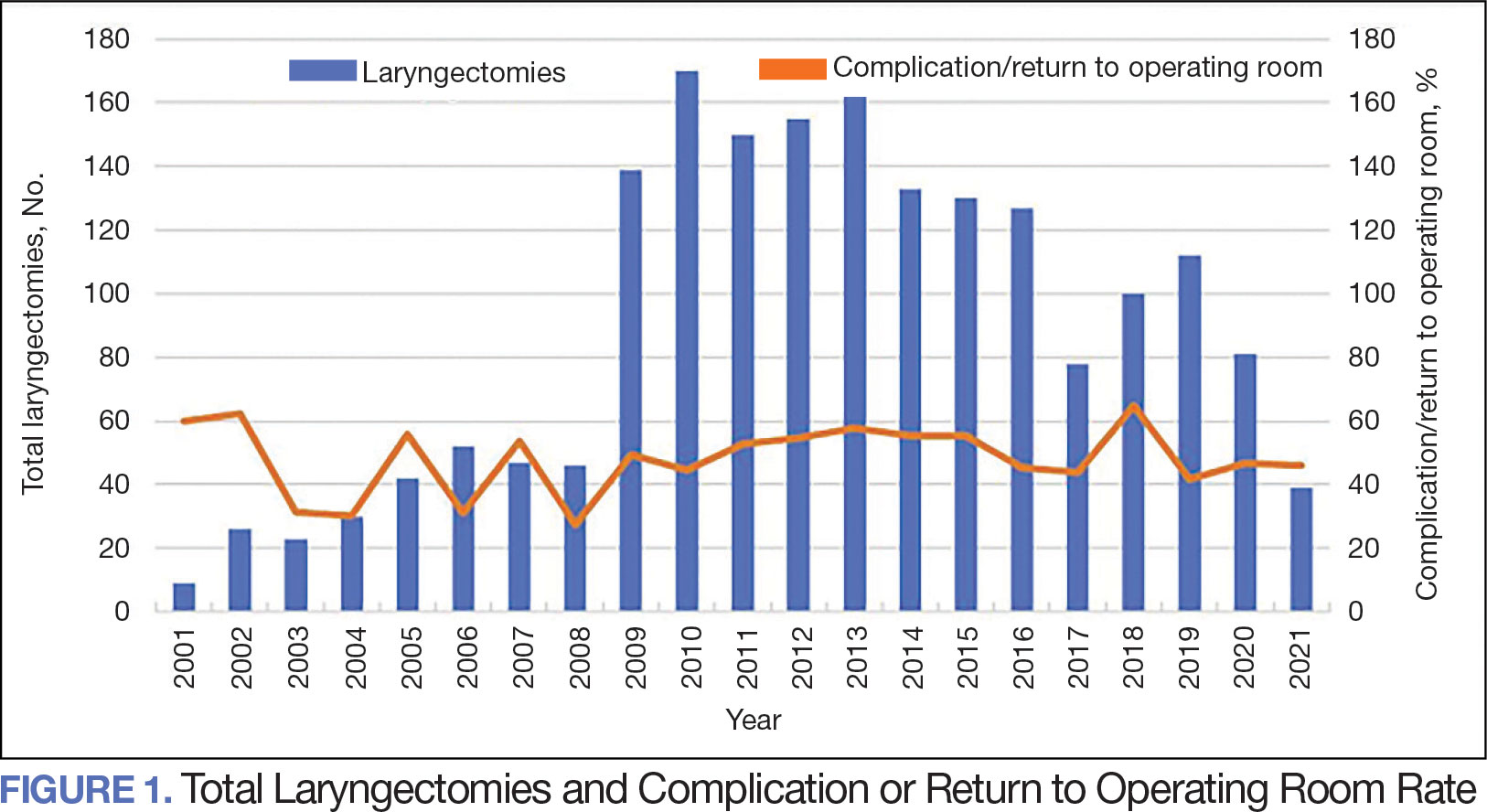

Initially, 2362 surgeries were identified. A randomized sample of 394 charts were reviewed and 131 cases met inclusion criteria. Each case involved a unique patient (Figure). The most common reasons for exclusion were 143 patients with diet-controlled DM and 78 nonelective surgeries. The mean (SD) age of patients was 68 (8) years, and the most were male (98.5%) and White (76.3%) (Table 1).

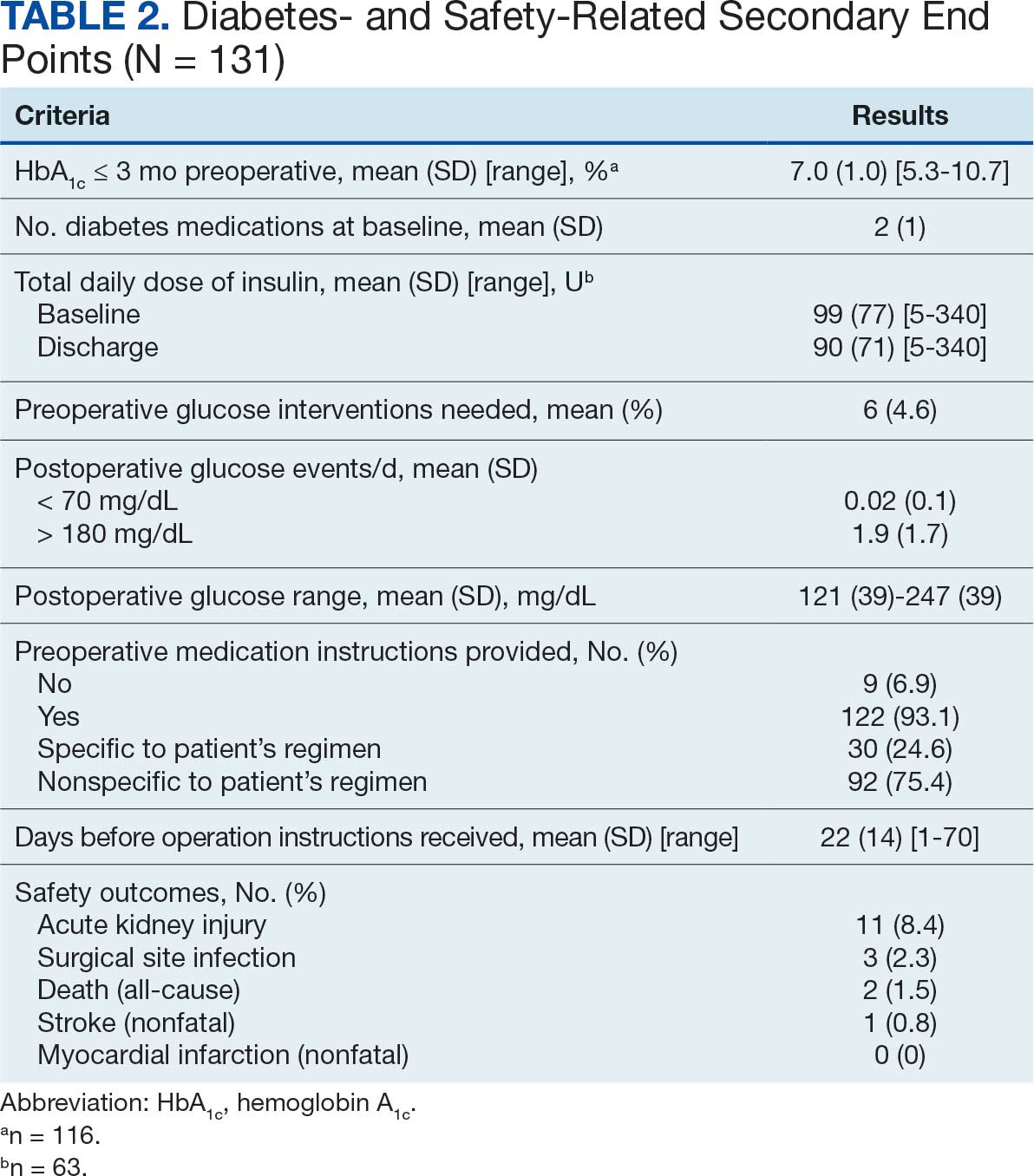

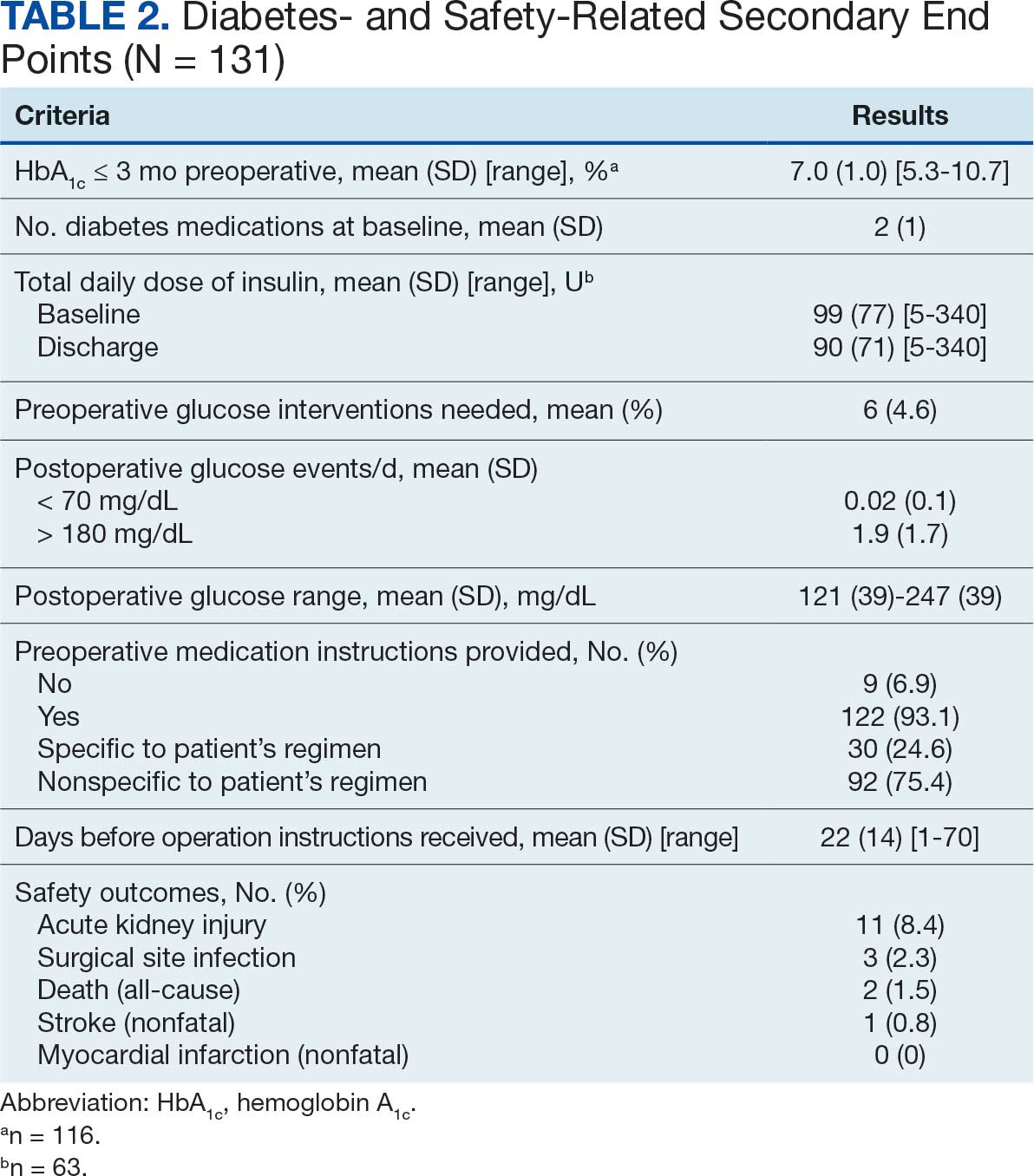

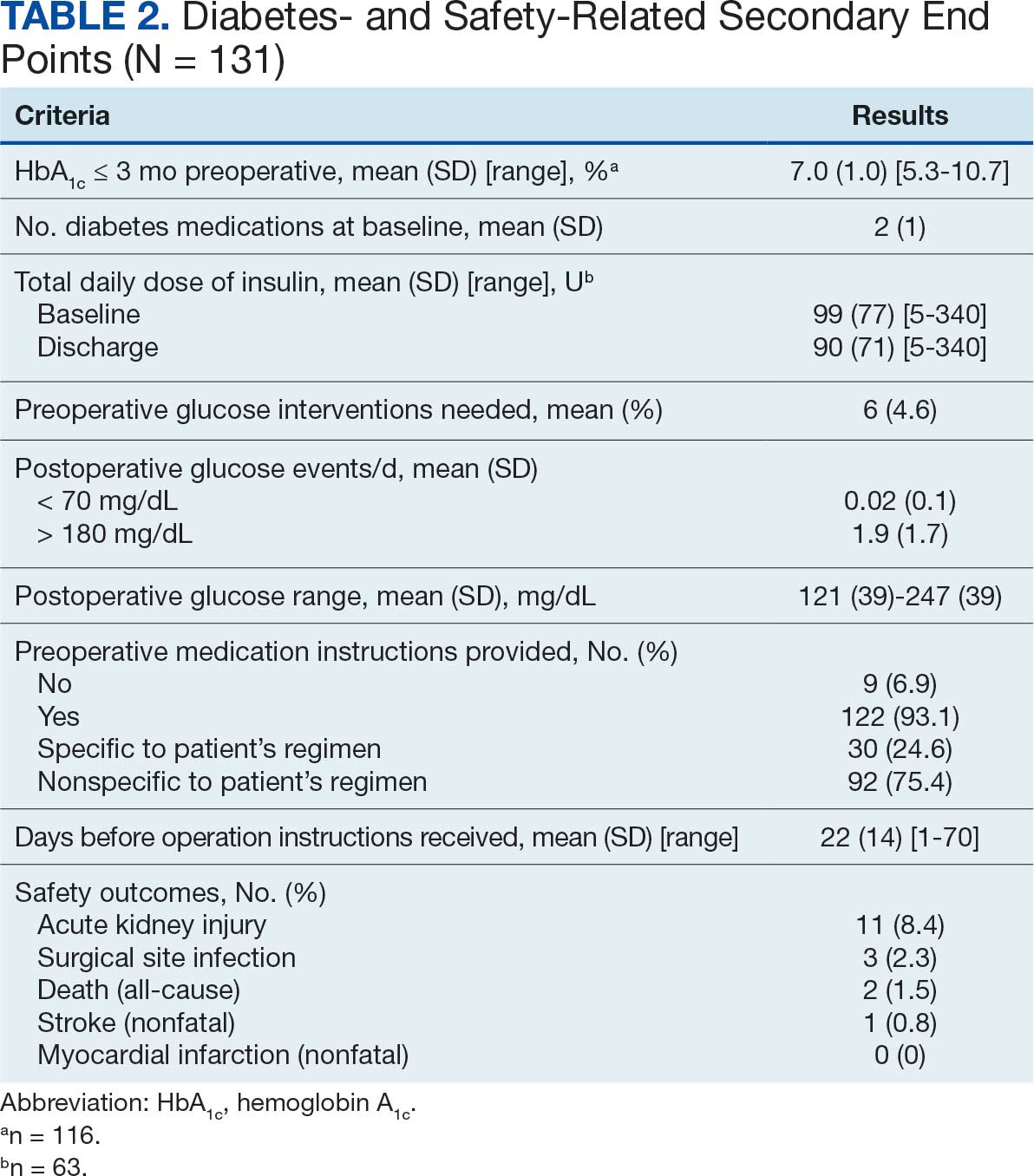

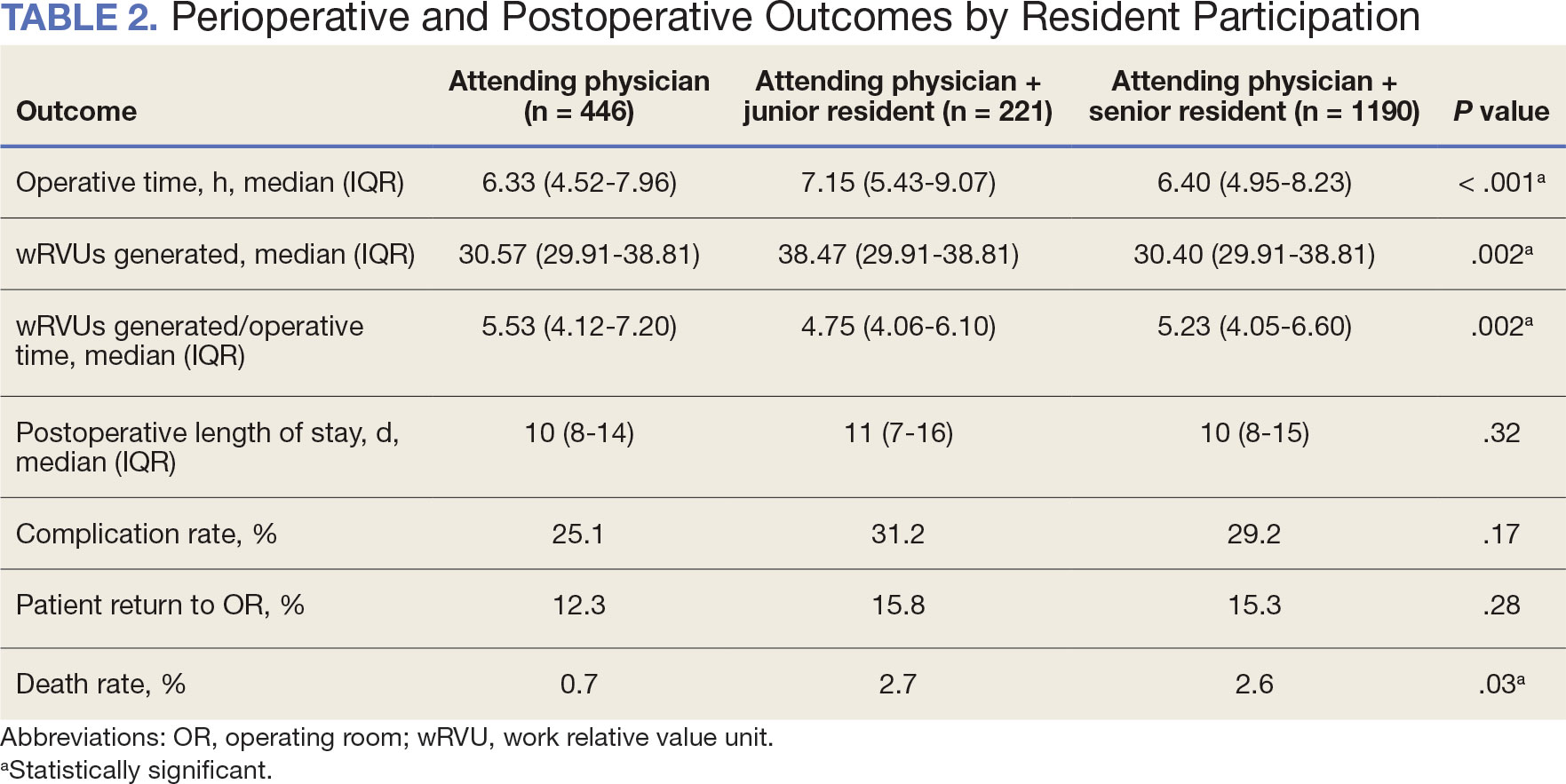

At baseline, 45 of 131 patients (34.4%) had coronary artery disease and 29 (22.1%) each had autonomic neuropathy and chronic kidney disease. Most surgeries were conducted by orthopedic (32.1%) and peripheral vascular (21.4%) specialties. The mean (SD) length of surgery was 4.6 (2.6) hours and of hospital length of stay was 4 (4) days. No patients stayed longer than the 30-day safety outcome follow-up period. All patients had type 2 DM and took a mean 2 DM medications. The 63 patients taking insulin had a mean (SD) total daily dose of 99 (77) U (Table 2). A preoperative HbA1c was collected in 116 patients within 3 months of surgery, with a mean HbA1c of 7.0% (range, 5.3-10.7).

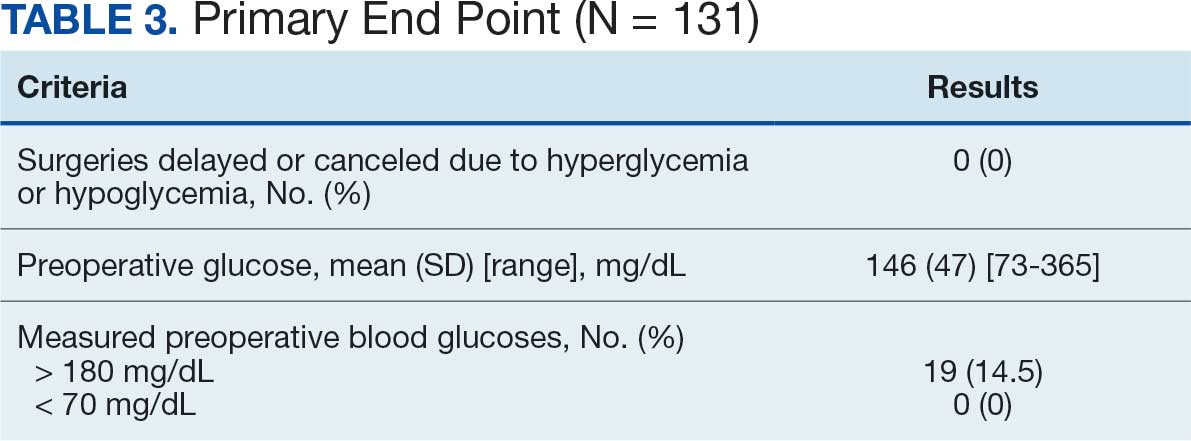

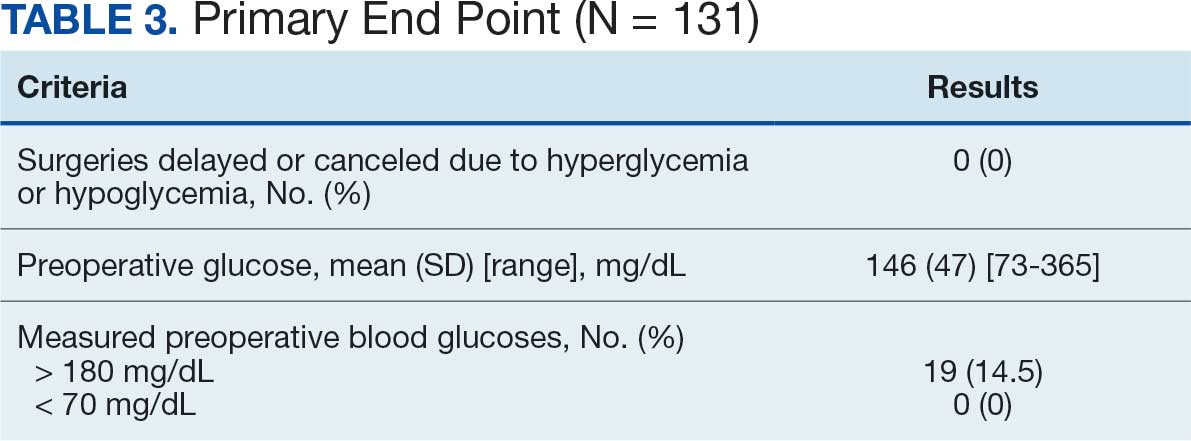

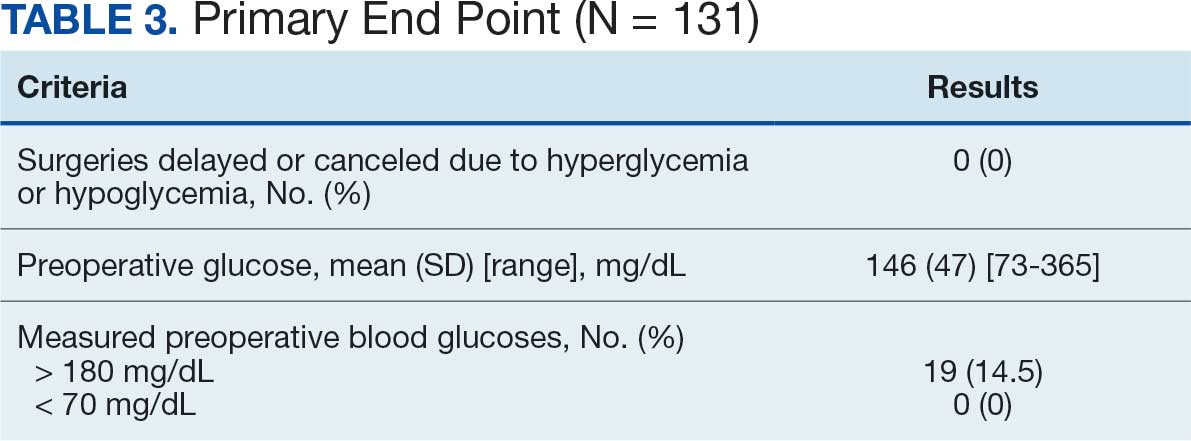

No patients had surgeries delayed or canceled because of uncontrolled DM on the day of surgery. The mean preoperative blood glucose level was 146 mg/dL (range, 73-365) (Table 3). No patients had a preoperative blood glucose level of < 70 mg/dL and 19 (14.5%) had a blood glucose level > 180 mg/dL. Among patients with hyperglycemia immediately prior to surgery, 6 (31.6%) had documentation of insulin being provided.

For this sample of patients, the preoperative clinic visit was conducted a mean 22 days prior to the planned surgery date. Among the 131 included patients, 122 (93.1%) had documentation of receiving instructions for DM medications. Among patients who had documented receipt of instructions, only 30 (24.6%) had instructions specifically tailored to their regimen rather than a generic templated form. The mean (SD) preoperative blood glucose was similar for those who received specific perioperative DM instructions at 146 (50) mg/dL when compared with those who did not at 147 (45) mg/dL. The mean (SD) preoperative blood glucose reading for those who had no documentation of receipt of perioperative instructions was 126 (54) mg/dL compared with 147 (46) mg/dL for those who did.

The mean number of postoperative blood glucose events per day was negligible for hypoglycemia and more frequent for hyperglycemia with a mean of 2 events per day. The mean postoperative blood glucose range was 121 to 247 mg/dL with most readings < 180 mg/dL. Upon discharge, most patients continued their home DM regimen with 5 patients (3.8%) having changes made to their regimen upon discharge.

Very few postoperative complications were identified from chart review. The most frequently observed postoperative complications were acute kidney injury, surgical site infections, and nonfatal stroke. There were no documented nonfatal myocardial infarctions. Two patients (1.5%) died within 30 days of the surgery; neither death was deemed to have been related to poor perioperative glycemic control.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this retrospective chart review was the first study to assess preoperative DM management and postoperative complications in a veteran population. VHI is a large, tertiary, level 1a, academic medical center that serves approximately 62,000 veterans annually and performs about 5000 to 6000 surgeries annually, a total that is increasing following the COVID-19 pandemic.20 This study found that the current process of a presurgery clinic visit and day of surgery glucose assessment has prevented surgical delays or cancellations.

Most patients included in this study were well controlled at baseline in accordance with the 2025 ADA SOC HbA1c recommendation of a preoperative HbA1c of < 8%, which may have contributed to no surgical delays or cancellations.10 However, not all patients had HbA1c collected within 3 months of surgery or even had one collected at all. Despite the ADA SOC providing no explicit recommendation for universal HbA1c screening prior to elective procedures, its importance cannot be understated given the body of evidence demonstrating poor outcomes with uncontrolled preoperative DM.8,10 The glycemic control at baseline may have contributed to the very few postsurgical complications observed in this study.

Although the current process at VHI prevented surgical delays and cancellations in this sample, there are still identified areas for improvement. One area is the instructions the patients received. Patients with DM are often prescribed ≥ 1 medication or a combination of insulins, noninsulin injectables, and oral DM medications, and this study population was no different. Because these medications may influence the anesthesia and perioperative periods, the ADA has specific guidance for altering administration schedules in the days leading up to surgery.10

Inappropriate administration of DM medications could lead to perioperative hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia, possibly causing surgical delays, case cancellations, and/or postoperative complications.21 Although these data reveal the specificity and documented receipt that the preoperative DM instructions did not impact the first recorded preoperative blood glucose, future studies should examine patient confidence in how to properly administer their DM medications prior to surgery. It is vital that patients receive clear instructions in accordance with the ADA SOC on whether to continue, hold, or adjust the dose of their medications to prevent fluctuations in blood glucose levels in the perioperative period, ensure safety with anesthesia, and prevent postoperative complications such as acute kidney injury. Of note, compliance with guideline recommendations for medication instructions was not examined because the data collection time frame expanded over multiple years and the recommendations have evolved each year as new data emerge.

Preoperative DM Management

The first key takeaway from this study is to ensure patients are ready for surgery with a formal assessment (typically in the form of a clinic visit) prior to the surgery. One private sector health system published their approach to this by administering an automatic preoperative HbA1c screening for those with a DM diagnosis and all patients with a random plasma glucose ≥ 200 mg/dL.22 Additionally, if the patient's HbA1c level was not at goal prior to surgery (≥ 8% for those with known DM and ≥ 6.5% with no known DM), patients were referred to endocrinology for further management. Increasing attention to the preoperative visit and extending HbA1c testing to all patients regardless of DM status also provides an opportunity to identify individuals living with undiagnosed DM.1

Even though there was no difference in the mean preoperative blood glucose level based on receipt or specificity of preoperative DM instructions, a second takeaway from this study is the importance of ensuring patients receive clear instructions on their DM medication schedule in the perioperative period. A practical first step may be updating the templates used by the primary surgery teams and providing education to the clinicians in the clinic on how to personalize the visits. Because the current preoperative DM process at VHI is managed by the primary surgical team in a clinic visit, there is an opportunity to shift this responsibility to other health care professionals, such as pharmacists—a change shown to reduce unintended omission of home medications following surgery during hospitalization and reduce costs.23,24

Limitations

This study relied on data included in the patient chart. These data include medication interventions made immediately prior to surgery, which can sometimes be inaccurately charted or difficult to find as they are not documented in the typical medication administration record. Also, the safety outcomes were collected from a discharge summary written by different clinicians, which may lead to information bias. Special attention was taken to ensure these data points were collected as accurately as possible, but it is possible some data may be inaccurate from unintentional human error. Additionally, the safety outcome was limited to a 30-day follow-up, but encompassed the entire length of postoperative stay for all included patients. Finally, given this study was retrospective with no comparison group and the intent was to improve processes at VHI, only hypotheses and potential interventions can be generated from this study. Future prospective studies with larger sample sizes and comparator groups are needed to draw further conclusions.

Conclusions

This study found that the current presurgery process at VHI appears to be successful in preventing surgical delays or cancellations due to hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia. Optimizing DM management can improve surgical outcomes by decreasing rates of postoperative complications, and this study added additional evidence in support of that in a unique population: veterans. Insight on the awareness of preoperative blood glucose management should be gleaned from this study, and based on this sample and site, the preadmission screening process and instructions provided to patients can serve as 2 starting points for optimizing elective surgery.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes basics. May 15, 2024. Accessed September 24, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/about/index.html

- Liu Y, Sayam S, Shao X, et al. Prevalence of and trends in diabetes among veterans, United States, 2005-2014. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017;14:E135. doi:10.5888/pcd14.170230

- Farmaki P, Damaskos C, Garmpis N, et al . Complications of the Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2020;16(4):249-251. doi:10.2174/1573403X1604201229115531

- Frisch A, Chandra P, Smiley D, et al. Prevalence and clinical outcome of hyperglycemia in the perioperative period in noncardiac surgery. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1783-1788. doi:10.2337/dc10-0304

- Noordzij PG, Boersma E, Schreiner F, et al. Increased preoperative glucose levels are associated with perioperative mortality in patients undergoing noncardiac, nonvascular surgery. Eur J Endocrinol. 2007;156:137 -142. doi:10.1530/eje.1.02321

- Pomposelli JJ, Baxter JK 3rd, Babineau TJ, et al. Early postoperative glucose control predicts nosocomial infection rate in diabetic patients. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1998;22:77-81. doi:10.1177/01486071980220027

- Umpierrez GE, Smiley D, Jacobs S, et al. Randomized study of basal-bolus insulin therapy in the inpatient management of patients with type 2 diabetes undergoing general surgery (RABBIT 2 surgery). Diabetes Care. 2011;34:256-261. doi:10.2337/dc10-1407

- Pasquel FJ, Gomez-Huelgas R, Anzola I, et al. Predictive value of admission hemoglobin A1c on inpatient glycemic control and response to insulin therapy in medicine and surgery patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:e202-e203. doi:10.2337/dc15-1835

- Alexiewicz JM, Kumar D, Smogorzewski M, et al. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: abnormalities in metabolism and function. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:919-924. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-123-12-199512150-00004

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 16. Diabetes care in the hospital: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2025. Diabetes Care. 2025;48(1 suppl 1):S321-S334. doi:10.2337/dc25-S016

- Kumar R, Gandhi R. Reasons for cancellation of operation on the day of intended surgery in a multidisciplinary 500 bedded hospital. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2012;28:66-69. doi:10.4103/0970-9185.92442

- American Diabetes Association. 14. Diabetes care in the hospital: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes— 2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(1 suppl 1):S144- S151. doi:10.2337/dc18-S014

- American Diabetes Association. 15. Diabetes care in the hospital: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes— 2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(suppl 1):S173- S181. doi:10.2337/dc19-S015

- American Diabetes Association. 15. Diabetes care in the hospital: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes— 2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(suppl 1):S193- S202. doi:10.2337/dc20-S015

- American Diabetes Association. 15. Diabetes care in the hospital: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes— 2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(suppl 1):S211- S220. doi:10.2337/dc21-S015

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 16. Diabetes care in the hospital: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2022. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(suppl 1):S244-S253. doi:10.2337/dc22-S016

- ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 16. Diabetes care in the hospital: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(suppl 1):S267-S278. doi:10.2337/dc23-S016

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 16. Diabetes care in the hospital: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care. 2024;47(suppl 1):S295-S306. doi:10.2337/dc24-S016

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2:1-138. Accessed September 24, 2025. https:// www.kisupplements.org/issue/S2157-1716(12)X7200-9

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA Indiana Healthcare: about us. Accessed September 24, 2025. https:// www.va.gov/indiana-health-care/about-us/

- Koh WX, Phelan R, Hopman WM, et al. Cancellation of elective surgery: rates, reasons and effect on patient satisfaction. Can J Surg. 2021;64:E155-E161. doi:10.1503/cjs.008119

- Pai S-L, Haehn DA, Pitruzzello NE, et al. Reducing infection rates with enhanced preoperative diabetes mellitus diagnosis and optimization processes. South Med J. 2023;116:215-219. doi:10.14423/SMJ.0000000000001507

- Forrester TG, Sullivan S, Snoswell CL, et al. Integrating a pharmacist into the perioperative setting. Aust Health Rev. 2020;44:563-568. doi:10.1071/AH19126

- Hale AR, Coombes ID, Stokes J, et al. Perioperative medication management: expanding the role of the preadmission clinic pharmacist in a single centre, randomised controlled trial of collaborative prescribing. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003027. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003027

More than 38 million people in the United States (12%) have diabetes mellitus (DM), though 1 in 5 are unaware they have DM.1 The prevalence among veterans is even more substantial, impacting nearly 25% of those who received care from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).2 DM can lead to increased health care costs in addition to various complications (eg, cardiovascular, renal), especially if left uncontrolled.1,3 similar impact is found in the perioperative period (defined as at or around the time of an operation), as multiple studies have found that uncontrolled preoperative DM can result in worsened surgical outcomes, including longer hospital stays, more infectious complications, and higher perioperative mortality.4-6

In contrast, adequate glycemic control assessed with blood glucose levels has been shown to decrease the incidence of postoperative infections.7 Optimizing glycemic control during hospital stays, especially postsurgery, has become the standard of care, with most health systems establishing specific protocols. In current literature, most studies examining DM management in the perioperative period are focused on postoperative care, with little attention to the preoperative period.4,6,7

One study found that patients with poor presurgery glycemic control assessed by hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels were more likely to remain hyperglycemic during and after surgery. 8 Blood glucose levels < 200 mg/dL can lead to an increased risk of infection and impaired wound healing, meaning a well-controlled HbA1c before a procedure serves as a potential factor for success.9 The 2025 American Diabetes Association (ADA) Standards of Care (SOC) recommendation is to target HbA1c < 8% whenever possible, and some health systems require lower levels (eg, < 7% or 7.5%).10 With that goal in mind and knowing that preoperative hyperglycemia has been shown to be a contributing factor in the delay or cancellation of surgical cases, an argument can be made that attention to preoperative DM management also should be a focus for health care systems performing surgeries.8,9,11

Attention to glucose control during preoperative care offers an opportunity to screen for DM in patients who may not have been screened otherwise and to standardize perioperative DM management. Since DM disproportionately impacts veterans, this is a pertinent issue to the VA. Veterans can be more susceptible to complications if DM is left uncontrolled prior to surgery. To determine readiness for surgery and control of comorbid conditions such as DM before a planned surgery, facilities often perform a preoperative clinic assessment, often in a multidisciplinary clinic.

At Veteran Health Indiana (VHI), a presurgery clinic visit involving the primary surgery service (physician, nurse practitioner, and/or a physician assistant) is conducted 1 to 2 months prior to the planned procedure to determine whether a patient is ready for surgery. During this visit, patients receive a packet with instructions for various tasks and medications, such as applying topical antibiotic prophylaxis on the anticipated surgical site. This is documented in the form of a note in the VHI Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS). The medication instructions are provided according to the preferences of the surgical team. These may be templated notes that contain general directions on the timing and dosing of specific medications, in addition to instructions for holding or reducing doses when appropriate. The instructions can be tailored by the team conducting the preoperative visit (eg, “Take 20 units of insulin glargine the day before surgery” vs “Take half of your long-acting insulin the night before surgery”). Specific to DM, VHI has a nurse-driven day of surgery glucose assessment where point-of-care blood glucose is collected during preoperative holding for most patients.

There is limited research assessing the level of preoperative glycemic control and the incidence of complications in a veteran population. The objective of this study was to gain a baseline understanding of what, if any, standardization exists for preoperative instructions for DM medications and to assess the level of preoperative glycemic control and postoperative complications in patients with DM undergoing major elective surgical procedures.

Methods

This retrospective, single-center chart review was conducted at VHI. The Indiana University and VHI institutional review boards determined that this quality improvement project was exempt from review.

The primary outcome was the number of patients with surgical procedures delayed or canceled due to hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia. Hyperglycemia was defined as blood glucose > 180 mg/dL and hypoglycemia was defined as < 70 mg/dL, slight variations from the current ADA SOC preoperative specific recommendation of a blood glucose reading of 100 to 180 mg/dL within 4 hours of surgery.10 The standard outpatient hypoglycemia definition of blood glucose < 70 mg/dL was chosen because the current goal (< 100 mg/dL) was not the standard in previous ADA SOCs that were in place during the study period. Specifically, the 2018 ADA SOC did not provide preoperative recommendations and the 2019-2021 ADA SOC recommended 80 to 180 mg/dL.10,12-18 For patients who had multiple preoperative blood glucose measurements, the first recorded glucose on the day of the procedure was used.

The secondary outcomes of this study were focused on the preoperative process/care at VHI and postoperative glycemic control. The preoperative process included examining whether medication instructions were given and their quality. Additionally, the number of interventions for hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia were required immediately prior to surgery and the average preoperative HbA1c (measured within 3 months prior to surgery) were collected and analyzed. For postoperative glycemic control, average blood glucose measurements and number of hypoglycemic (< 70 mg/dL) and hyperglycemic (> 180 mg/dL) events were measured in addition to the frequency of changes made at discharge to patients’ DM medication regimens.

The safety outcome of this study assessed commonly observed postoperative complications and was examined up to 30 days postsurgery. These included acute kidney injury (defined using Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes 2012, the standard during the study period), nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, and surgical site infections, which were identified from the discharge summary written by the primary surgery service.19 All-cause mortality also was collected.

Patients were included if they were admitted for major elective surgeries and had a diagnosis of either type 1 or type 2 DM on their problem list, determined by International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes. Major elective surgery was defined as a procedure that would likely result in a hospital admission of > 24 hours. Of note, patients may have been included in this study more than once if they had > 1 procedure at least 30 days apart and met inclusion criteria within the time frame. Patients were excluded if they were taking no DM medications or chronic steroids (at any dose), residing in a long-term care facility, being managed by a non-VA clinician prior to surgery, or missing a preoperative blood glucose measurement.

All data were collected from the CPRS. A list of surgical cases involving patients with DM who were scheduled to undergo major elective surgeries from January 1, 2018, to December 31, 2021, at VHI was generated. The list was randomized to a smaller number (N = 394) for data collection due to the time and resource constraints for a pharmacy residency project. All data were deidentified and stored in a secured VA server to protect patient confidentiality. Descriptive statistics were used for all results.

Results

Initially, 2362 surgeries were identified. A randomized sample of 394 charts were reviewed and 131 cases met inclusion criteria. Each case involved a unique patient (Figure). The most common reasons for exclusion were 143 patients with diet-controlled DM and 78 nonelective surgeries. The mean (SD) age of patients was 68 (8) years, and the most were male (98.5%) and White (76.3%) (Table 1).

At baseline, 45 of 131 patients (34.4%) had coronary artery disease and 29 (22.1%) each had autonomic neuropathy and chronic kidney disease. Most surgeries were conducted by orthopedic (32.1%) and peripheral vascular (21.4%) specialties. The mean (SD) length of surgery was 4.6 (2.6) hours and of hospital length of stay was 4 (4) days. No patients stayed longer than the 30-day safety outcome follow-up period. All patients had type 2 DM and took a mean 2 DM medications. The 63 patients taking insulin had a mean (SD) total daily dose of 99 (77) U (Table 2). A preoperative HbA1c was collected in 116 patients within 3 months of surgery, with a mean HbA1c of 7.0% (range, 5.3-10.7).

No patients had surgeries delayed or canceled because of uncontrolled DM on the day of surgery. The mean preoperative blood glucose level was 146 mg/dL (range, 73-365) (Table 3). No patients had a preoperative blood glucose level of < 70 mg/dL and 19 (14.5%) had a blood glucose level > 180 mg/dL. Among patients with hyperglycemia immediately prior to surgery, 6 (31.6%) had documentation of insulin being provided.

For this sample of patients, the preoperative clinic visit was conducted a mean 22 days prior to the planned surgery date. Among the 131 included patients, 122 (93.1%) had documentation of receiving instructions for DM medications. Among patients who had documented receipt of instructions, only 30 (24.6%) had instructions specifically tailored to their regimen rather than a generic templated form. The mean (SD) preoperative blood glucose was similar for those who received specific perioperative DM instructions at 146 (50) mg/dL when compared with those who did not at 147 (45) mg/dL. The mean (SD) preoperative blood glucose reading for those who had no documentation of receipt of perioperative instructions was 126 (54) mg/dL compared with 147 (46) mg/dL for those who did.

The mean number of postoperative blood glucose events per day was negligible for hypoglycemia and more frequent for hyperglycemia with a mean of 2 events per day. The mean postoperative blood glucose range was 121 to 247 mg/dL with most readings < 180 mg/dL. Upon discharge, most patients continued their home DM regimen with 5 patients (3.8%) having changes made to their regimen upon discharge.

Very few postoperative complications were identified from chart review. The most frequently observed postoperative complications were acute kidney injury, surgical site infections, and nonfatal stroke. There were no documented nonfatal myocardial infarctions. Two patients (1.5%) died within 30 days of the surgery; neither death was deemed to have been related to poor perioperative glycemic control.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this retrospective chart review was the first study to assess preoperative DM management and postoperative complications in a veteran population. VHI is a large, tertiary, level 1a, academic medical center that serves approximately 62,000 veterans annually and performs about 5000 to 6000 surgeries annually, a total that is increasing following the COVID-19 pandemic.20 This study found that the current process of a presurgery clinic visit and day of surgery glucose assessment has prevented surgical delays or cancellations.

Most patients included in this study were well controlled at baseline in accordance with the 2025 ADA SOC HbA1c recommendation of a preoperative HbA1c of < 8%, which may have contributed to no surgical delays or cancellations.10 However, not all patients had HbA1c collected within 3 months of surgery or even had one collected at all. Despite the ADA SOC providing no explicit recommendation for universal HbA1c screening prior to elective procedures, its importance cannot be understated given the body of evidence demonstrating poor outcomes with uncontrolled preoperative DM.8,10 The glycemic control at baseline may have contributed to the very few postsurgical complications observed in this study.