User login

The Bigger They Are ...

Editor’s note: This is the first of a two-part series addressing large HM group issues.

In the mid-1990s, when I first became interested in how other hospitalist groups were organized, I started surveying by phone all the groups I could find. It was really unusual to find a group larger than four or five full-time equivalent (FTE) hospitalists. Since then, the size of a typical hospitalist group has grown steadily, and data reported in SHM’s “2007-2008 Bi-Annual Survey on the State of Hospital Medicine” shows the median number of FTE physicians in HM groups is 8.0 (mean of 9.75). So in just a few years, our field has grown in such a way that half of all groups in operation now have more than eight physician FTEs. I think most future growth in numbers of hospitalists will be due to individual practices getting larger, rather than new practices starting up.

I work regularly with groups that have more than 20 FTEs, and I have found that large groups tend to have a number of attributes in common.

Separate Daytime Admitter and Rounder Functions

Large groups almost always staff admitter and rounder functions with separate doctors around the clock. That means patients arriving during regular business hours are admitted by a different doctor (the admitter) than the doctor who will provide their care on Day Two and beyond (the rounder).

Although such a system is popular, I suggest every group challenge itself to think about whether it really is the best system. Most groups, regardless of size, have about a quarter to a third of their new admits and consults arrive between 7 a.m. and 5 p.m. If the group did away with a separate admitter during the day and moved all daytime admitters into additional rounder positions, all the daytime admissions could be rotated among all of the daytime doctors, and those patients would typically be seen by the same hospitalist the next day. That would improve hospitalist-patient continuity for the patients who arrive during the day, which might improve the group’s overall efficiency as well as quality and patient satisfaction. Each rounder would become responsible for seeing up to three new consults or admissions during the course of the daytime rounding shift, and the list of new patients to take over each morning—patients admitted by the evening and night admitters—would be smaller.

Of course, one significant benefit of having a separate admitter shift during the day is relieving the rounding doctors of the stress of interrupting rounds for an unpredictable number of new admissions each day. And if the new admissions arrive in the morning, throughput may suffer as it might mean the rounding doctor may see “dischargeable” patients later in the day.

I think there is room for debate about whether it is best for large groups to have a separate admitter during the day, but whatever approach a group chooses, it should acknowledge the costs of that approach and not just assume that it is the only one that is feasible or reasonable.

Who Is Caring for Whom?

The larger the hospitalist group, the more difficulty nurses and other staff have understanding exactly how patients are distributed among the doctors. When one hospitalist rotates “off service” to be replaced by another the next day, or when overnight admissions are “picked up” by a rounding doctor the next morning, it can be difficult for nurses to know which hospitalist is responsible for the patient at a given moment.

All groups, regardless of size, should ensure that the hospitalist who picks up patients from a colleague who has rotated off the day before writes an order in the chart indicating “change attending to Dr. Jones,” or clearly communicates who the new hospitalist is by some other means, such as an electronic medical record or a phone call from a clerk. It isn’t enough that patients are assigned to a particular team—say, the “white team” or the “green team”—for their entire stay. Nurses and other staff need to know which hospitalist is covering that team each day.

One test of how well your system is working is to assess how the nurse answers when a patient or family asks, “Which doctor will be in to see me today?” It isn’t good enough for the nurse to just say, “The green-team doctor will see you, but I don’t know who that is today.” The nurse needs to be able to provide the name of the doctor who will be in. If nurses at your hospital regularly page the wrong hospitalist, or must call around just to figure out who the attending hospitalist is for a particular patient, then you have an opportunity to improve how you communicate this information to the nurse and others.

Even if you have a system in which it is clear to everyone which hospitalist has taken over for one who has rotated off-service, you need to ensure that nurses can easily determine the attending hospitalist for patients admitted the night before. Night-shift staff not knowing which doctor will take over in the morning is an all-too-common problem, and it results in too many staffers not knowing who is caring for the patient from the time the night doctor goes off (e.g., 7 a.m.) until the rounder taking over gets to that patient on rounds. Having evening/night admitters assign attending, or rounder, hospitalists at the time of each admission is a great solution, and I’ll provide ideas about how to do this in next month’s column.

I worry about patient satisfaction if the evening/night admitter can’t tell the patient the name of the hospitalist who will take over in the morning. How can the patient feel that they’re getting personalized care when they’re told, “I don’t know which of my partners will take over your care tomorrow. They all get together and divide up the patients each morning and will assign a doctor to you then”? It’s different if the admitter tells the patient, “I’m on call for our group tonight, but will be home sleeping tomorrow and my colleague, Dr. Clapton, will take over your care in the morning.” I usually go on to say with a wink that the patient is getting an upgrade, because Dr. Clapton is so much smarter and better-looking than me. I’ll understand if the embellishment doesn’t feel right for you, but I think there is value in the admitter, or a hospitalist rotating off-service, taking a minute to say something nice about the hospitalist who will take over next.

Next month, I will continue to explore issues that are particularly problematic for larger groups. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm. He also is part of the faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Editor’s note: This is the first of a two-part series addressing large HM group issues.

In the mid-1990s, when I first became interested in how other hospitalist groups were organized, I started surveying by phone all the groups I could find. It was really unusual to find a group larger than four or five full-time equivalent (FTE) hospitalists. Since then, the size of a typical hospitalist group has grown steadily, and data reported in SHM’s “2007-2008 Bi-Annual Survey on the State of Hospital Medicine” shows the median number of FTE physicians in HM groups is 8.0 (mean of 9.75). So in just a few years, our field has grown in such a way that half of all groups in operation now have more than eight physician FTEs. I think most future growth in numbers of hospitalists will be due to individual practices getting larger, rather than new practices starting up.

I work regularly with groups that have more than 20 FTEs, and I have found that large groups tend to have a number of attributes in common.

Separate Daytime Admitter and Rounder Functions

Large groups almost always staff admitter and rounder functions with separate doctors around the clock. That means patients arriving during regular business hours are admitted by a different doctor (the admitter) than the doctor who will provide their care on Day Two and beyond (the rounder).

Although such a system is popular, I suggest every group challenge itself to think about whether it really is the best system. Most groups, regardless of size, have about a quarter to a third of their new admits and consults arrive between 7 a.m. and 5 p.m. If the group did away with a separate admitter during the day and moved all daytime admitters into additional rounder positions, all the daytime admissions could be rotated among all of the daytime doctors, and those patients would typically be seen by the same hospitalist the next day. That would improve hospitalist-patient continuity for the patients who arrive during the day, which might improve the group’s overall efficiency as well as quality and patient satisfaction. Each rounder would become responsible for seeing up to three new consults or admissions during the course of the daytime rounding shift, and the list of new patients to take over each morning—patients admitted by the evening and night admitters—would be smaller.

Of course, one significant benefit of having a separate admitter shift during the day is relieving the rounding doctors of the stress of interrupting rounds for an unpredictable number of new admissions each day. And if the new admissions arrive in the morning, throughput may suffer as it might mean the rounding doctor may see “dischargeable” patients later in the day.

I think there is room for debate about whether it is best for large groups to have a separate admitter during the day, but whatever approach a group chooses, it should acknowledge the costs of that approach and not just assume that it is the only one that is feasible or reasonable.

Who Is Caring for Whom?

The larger the hospitalist group, the more difficulty nurses and other staff have understanding exactly how patients are distributed among the doctors. When one hospitalist rotates “off service” to be replaced by another the next day, or when overnight admissions are “picked up” by a rounding doctor the next morning, it can be difficult for nurses to know which hospitalist is responsible for the patient at a given moment.

All groups, regardless of size, should ensure that the hospitalist who picks up patients from a colleague who has rotated off the day before writes an order in the chart indicating “change attending to Dr. Jones,” or clearly communicates who the new hospitalist is by some other means, such as an electronic medical record or a phone call from a clerk. It isn’t enough that patients are assigned to a particular team—say, the “white team” or the “green team”—for their entire stay. Nurses and other staff need to know which hospitalist is covering that team each day.

One test of how well your system is working is to assess how the nurse answers when a patient or family asks, “Which doctor will be in to see me today?” It isn’t good enough for the nurse to just say, “The green-team doctor will see you, but I don’t know who that is today.” The nurse needs to be able to provide the name of the doctor who will be in. If nurses at your hospital regularly page the wrong hospitalist, or must call around just to figure out who the attending hospitalist is for a particular patient, then you have an opportunity to improve how you communicate this information to the nurse and others.

Even if you have a system in which it is clear to everyone which hospitalist has taken over for one who has rotated off-service, you need to ensure that nurses can easily determine the attending hospitalist for patients admitted the night before. Night-shift staff not knowing which doctor will take over in the morning is an all-too-common problem, and it results in too many staffers not knowing who is caring for the patient from the time the night doctor goes off (e.g., 7 a.m.) until the rounder taking over gets to that patient on rounds. Having evening/night admitters assign attending, or rounder, hospitalists at the time of each admission is a great solution, and I’ll provide ideas about how to do this in next month’s column.

I worry about patient satisfaction if the evening/night admitter can’t tell the patient the name of the hospitalist who will take over in the morning. How can the patient feel that they’re getting personalized care when they’re told, “I don’t know which of my partners will take over your care tomorrow. They all get together and divide up the patients each morning and will assign a doctor to you then”? It’s different if the admitter tells the patient, “I’m on call for our group tonight, but will be home sleeping tomorrow and my colleague, Dr. Clapton, will take over your care in the morning.” I usually go on to say with a wink that the patient is getting an upgrade, because Dr. Clapton is so much smarter and better-looking than me. I’ll understand if the embellishment doesn’t feel right for you, but I think there is value in the admitter, or a hospitalist rotating off-service, taking a minute to say something nice about the hospitalist who will take over next.

Next month, I will continue to explore issues that are particularly problematic for larger groups. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm. He also is part of the faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Editor’s note: This is the first of a two-part series addressing large HM group issues.

In the mid-1990s, when I first became interested in how other hospitalist groups were organized, I started surveying by phone all the groups I could find. It was really unusual to find a group larger than four or five full-time equivalent (FTE) hospitalists. Since then, the size of a typical hospitalist group has grown steadily, and data reported in SHM’s “2007-2008 Bi-Annual Survey on the State of Hospital Medicine” shows the median number of FTE physicians in HM groups is 8.0 (mean of 9.75). So in just a few years, our field has grown in such a way that half of all groups in operation now have more than eight physician FTEs. I think most future growth in numbers of hospitalists will be due to individual practices getting larger, rather than new practices starting up.

I work regularly with groups that have more than 20 FTEs, and I have found that large groups tend to have a number of attributes in common.

Separate Daytime Admitter and Rounder Functions

Large groups almost always staff admitter and rounder functions with separate doctors around the clock. That means patients arriving during regular business hours are admitted by a different doctor (the admitter) than the doctor who will provide their care on Day Two and beyond (the rounder).

Although such a system is popular, I suggest every group challenge itself to think about whether it really is the best system. Most groups, regardless of size, have about a quarter to a third of their new admits and consults arrive between 7 a.m. and 5 p.m. If the group did away with a separate admitter during the day and moved all daytime admitters into additional rounder positions, all the daytime admissions could be rotated among all of the daytime doctors, and those patients would typically be seen by the same hospitalist the next day. That would improve hospitalist-patient continuity for the patients who arrive during the day, which might improve the group’s overall efficiency as well as quality and patient satisfaction. Each rounder would become responsible for seeing up to three new consults or admissions during the course of the daytime rounding shift, and the list of new patients to take over each morning—patients admitted by the evening and night admitters—would be smaller.

Of course, one significant benefit of having a separate admitter shift during the day is relieving the rounding doctors of the stress of interrupting rounds for an unpredictable number of new admissions each day. And if the new admissions arrive in the morning, throughput may suffer as it might mean the rounding doctor may see “dischargeable” patients later in the day.

I think there is room for debate about whether it is best for large groups to have a separate admitter during the day, but whatever approach a group chooses, it should acknowledge the costs of that approach and not just assume that it is the only one that is feasible or reasonable.

Who Is Caring for Whom?

The larger the hospitalist group, the more difficulty nurses and other staff have understanding exactly how patients are distributed among the doctors. When one hospitalist rotates “off service” to be replaced by another the next day, or when overnight admissions are “picked up” by a rounding doctor the next morning, it can be difficult for nurses to know which hospitalist is responsible for the patient at a given moment.

All groups, regardless of size, should ensure that the hospitalist who picks up patients from a colleague who has rotated off the day before writes an order in the chart indicating “change attending to Dr. Jones,” or clearly communicates who the new hospitalist is by some other means, such as an electronic medical record or a phone call from a clerk. It isn’t enough that patients are assigned to a particular team—say, the “white team” or the “green team”—for their entire stay. Nurses and other staff need to know which hospitalist is covering that team each day.

One test of how well your system is working is to assess how the nurse answers when a patient or family asks, “Which doctor will be in to see me today?” It isn’t good enough for the nurse to just say, “The green-team doctor will see you, but I don’t know who that is today.” The nurse needs to be able to provide the name of the doctor who will be in. If nurses at your hospital regularly page the wrong hospitalist, or must call around just to figure out who the attending hospitalist is for a particular patient, then you have an opportunity to improve how you communicate this information to the nurse and others.

Even if you have a system in which it is clear to everyone which hospitalist has taken over for one who has rotated off-service, you need to ensure that nurses can easily determine the attending hospitalist for patients admitted the night before. Night-shift staff not knowing which doctor will take over in the morning is an all-too-common problem, and it results in too many staffers not knowing who is caring for the patient from the time the night doctor goes off (e.g., 7 a.m.) until the rounder taking over gets to that patient on rounds. Having evening/night admitters assign attending, or rounder, hospitalists at the time of each admission is a great solution, and I’ll provide ideas about how to do this in next month’s column.

I worry about patient satisfaction if the evening/night admitter can’t tell the patient the name of the hospitalist who will take over in the morning. How can the patient feel that they’re getting personalized care when they’re told, “I don’t know which of my partners will take over your care tomorrow. They all get together and divide up the patients each morning and will assign a doctor to you then”? It’s different if the admitter tells the patient, “I’m on call for our group tonight, but will be home sleeping tomorrow and my colleague, Dr. Clapton, will take over your care in the morning.” I usually go on to say with a wink that the patient is getting an upgrade, because Dr. Clapton is so much smarter and better-looking than me. I’ll understand if the embellishment doesn’t feel right for you, but I think there is value in the admitter, or a hospitalist rotating off-service, taking a minute to say something nice about the hospitalist who will take over next.

Next month, I will continue to explore issues that are particularly problematic for larger groups. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm. He also is part of the faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Top o’ the Morning

In the what-have-you-done-for-me-lately category, many hospitalists are expected to really ramp up their efforts to improve their hospital’s throughput. So many hospital executives, who not long ago were dazzled by impressive reductions in lengths of stay and cost per case attributable to hospitalists, seem to have turned their attention to discharging patients early in the day. To some hospitalists who still expect gratitude for things done in the past, it seems terribly unfair that administrators now expect us to attend to this new metric. And, by the way, don’t let discharging patients early in the day interfere with improvements in quality metrics, patient satisfaction, and documentation.

Because of these increasing demands on hospitalists, we might feel sorry for ourselves. I do sometimes. But I also know that if we became hospital executives—and some of us have—we would expect the same of hospitalists in our institutions.

I’m struck by how often hospitalists, particularly those not in leadership positions, fail to understand why it matters so much to the execs that discharge orders are written early in the day. For them, I’ll try to provide a brief explanation.

Why It Matters

An increasing number of hospitals are operating with all of their staffed beds fully occupied. Many end up with patients boarding in the ED or ICU because no “regular” beds are available. And hospitals really suffer financially when they have to cancel elective admissions, such as surgeries, because no beds are available for the patient postop.

Hospitals could build more beds to increase their capacity, but that requires a long time and something along the lines of $1 million per bed. Where could they get the financing in today’s market? The other option is to shorten the length of time a patient occupies a bed so that more patients can be served using the existing inventory.

In nearly every hospital, the biggest bed crunch occurs in the afternoon. This is the time patients are ready to leave the post-anesthesia care unit or ED and move to their “floor” bed. If patients being discharged that day haven’t left yet, gridlock occurs. Costs of the gridlock are spread throughout the hospital, notably in the ED, which suffers because of the resulting increased lengths of stay and reduced throughput. This isn’t just an economic issue for the hospital; patients are adversely affected, too.

Even if your hospital has spare beds, early discharge still matters. If the discharge day isn’t managed well and patients routinely leave late in the afternoon, the hospital will have to spend more on evening-shift nursing staff.

It makes sense to look at every step that must occur prior to a patient vacating their room on the day of discharge. The time that the doctor actually writes the discharge order is one of the most critical, rate-limiting steps in the discharge process, so helpful executives suggest we organize our rounds to see the potential discharges first, then get around to seeing the patients who are really sick. I think most hospitalists, including me, find it really difficult to do this. If you’re in this category, you might consider starting your rounds earlier in the day.

Consider Rounding Earlier

Starting rounds earlier is usually an unpopular idea. Many groups refuse to consider it. If you are in a group that works day (rounding) shifts with specified start and stop times, coming in before the start of your shift to begin rounding is just donating uncompensated time to the practice. That is one of many reasons I think it is best for most practices to avoid specified start and stop times for their day shifts. Instead, I think it is reasonable for each doctor to decide when to start and stop work each day depending on the workload. So on days you have a higher-than-usual number of expected discharges or sick patients, you would probably choose to start earlier. And when patient volumes are low, you might choose to start later. The same is true of when you choose to leave for the day. Choosing to start earlier in the day should mean that you can wrap things up earlier on most days.

For a lot of hospitalists, routinely starting rounds earlier would be OK as long as they can finish earlier. But there are some for whom this is really tough or impossible, such as those who need to take their kids to school before work each morning. Rounding early won’t do any good if the hospital doesn’t ensure test results and other information is available early.

A practice could choose to undertake an initiative as simple as the following steps to support improvements in writing most discharge orders early in the day:

- Encourage starting rounds earlier (e.g., 7 a.m.) on most days;

- Whenever possible, prepare discharge summaries the day before;

- As often as possible, write in the order section “probable discharge tomorrow” one day before planned discharges;

- Keep routine morning conferences, such as signout, as short as possible; move it to later in the day, or eliminate it entirely, if feasible; and

- If you have routine, sit-down rounds with case managers each morning, think about whether they get in the way of early-in-the-day discharges. If so, consider moving them to the afternoons, and focus on discussing the next day’s potential discharges rather than discharges for the current day.

Consider establishing targets for each of these metrics and audit performance compared with a historical baseline. For example, the goal might be that the “probable discharge tomorrow” order appears the day before discharge in 50% of hospitalist patients, and the discharge summary is prepared the day before in 30%. These things help ensure other hospital staff members realize discharge is possible or likely and can significantly reduce discharges that are a surprise to nurses and others.

There is nothing magic about the bulleted protocol above. I’m offering it as only one potential idea to improve throughput, and you might want to pursue an entirely different strategy.

The Flip Side

Two closely related issues come up when working on getting discharge orders written early in the day. The first is that some late-afternoon discharges are in reality very early discharges that might have otherwise waited until the next day. It is important to stress that not all discharge orders are written early, and that hospitalists should not hold on to patients who could be discharged late in the day and instead release them the next morning to make their statistics look better.

The other related point is that a declining length of stay and discharging early in the day begin to compete with each other at some point. From a bed management perspective, the theoretical optimal length of stay means discharging patients the moment they are ready and not waiting until the next morning. This means discharging around the clock without regard to the time of day, and that would look terrible when analyzed from the perspective of the portion of discharge orders written early in the day—not to mention it would be very unpleasant for patients asked to leave at night. So I’m not suggesting that we should be discharging patients around the clock, but I just want to point out the tension between length of stay and writing discharge orders early in the day. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospital practice management consulting firm. He is part of the faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official SHM position.

In the what-have-you-done-for-me-lately category, many hospitalists are expected to really ramp up their efforts to improve their hospital’s throughput. So many hospital executives, who not long ago were dazzled by impressive reductions in lengths of stay and cost per case attributable to hospitalists, seem to have turned their attention to discharging patients early in the day. To some hospitalists who still expect gratitude for things done in the past, it seems terribly unfair that administrators now expect us to attend to this new metric. And, by the way, don’t let discharging patients early in the day interfere with improvements in quality metrics, patient satisfaction, and documentation.

Because of these increasing demands on hospitalists, we might feel sorry for ourselves. I do sometimes. But I also know that if we became hospital executives—and some of us have—we would expect the same of hospitalists in our institutions.

I’m struck by how often hospitalists, particularly those not in leadership positions, fail to understand why it matters so much to the execs that discharge orders are written early in the day. For them, I’ll try to provide a brief explanation.

Why It Matters

An increasing number of hospitals are operating with all of their staffed beds fully occupied. Many end up with patients boarding in the ED or ICU because no “regular” beds are available. And hospitals really suffer financially when they have to cancel elective admissions, such as surgeries, because no beds are available for the patient postop.

Hospitals could build more beds to increase their capacity, but that requires a long time and something along the lines of $1 million per bed. Where could they get the financing in today’s market? The other option is to shorten the length of time a patient occupies a bed so that more patients can be served using the existing inventory.

In nearly every hospital, the biggest bed crunch occurs in the afternoon. This is the time patients are ready to leave the post-anesthesia care unit or ED and move to their “floor” bed. If patients being discharged that day haven’t left yet, gridlock occurs. Costs of the gridlock are spread throughout the hospital, notably in the ED, which suffers because of the resulting increased lengths of stay and reduced throughput. This isn’t just an economic issue for the hospital; patients are adversely affected, too.

Even if your hospital has spare beds, early discharge still matters. If the discharge day isn’t managed well and patients routinely leave late in the afternoon, the hospital will have to spend more on evening-shift nursing staff.

It makes sense to look at every step that must occur prior to a patient vacating their room on the day of discharge. The time that the doctor actually writes the discharge order is one of the most critical, rate-limiting steps in the discharge process, so helpful executives suggest we organize our rounds to see the potential discharges first, then get around to seeing the patients who are really sick. I think most hospitalists, including me, find it really difficult to do this. If you’re in this category, you might consider starting your rounds earlier in the day.

Consider Rounding Earlier

Starting rounds earlier is usually an unpopular idea. Many groups refuse to consider it. If you are in a group that works day (rounding) shifts with specified start and stop times, coming in before the start of your shift to begin rounding is just donating uncompensated time to the practice. That is one of many reasons I think it is best for most practices to avoid specified start and stop times for their day shifts. Instead, I think it is reasonable for each doctor to decide when to start and stop work each day depending on the workload. So on days you have a higher-than-usual number of expected discharges or sick patients, you would probably choose to start earlier. And when patient volumes are low, you might choose to start later. The same is true of when you choose to leave for the day. Choosing to start earlier in the day should mean that you can wrap things up earlier on most days.

For a lot of hospitalists, routinely starting rounds earlier would be OK as long as they can finish earlier. But there are some for whom this is really tough or impossible, such as those who need to take their kids to school before work each morning. Rounding early won’t do any good if the hospital doesn’t ensure test results and other information is available early.

A practice could choose to undertake an initiative as simple as the following steps to support improvements in writing most discharge orders early in the day:

- Encourage starting rounds earlier (e.g., 7 a.m.) on most days;

- Whenever possible, prepare discharge summaries the day before;

- As often as possible, write in the order section “probable discharge tomorrow” one day before planned discharges;

- Keep routine morning conferences, such as signout, as short as possible; move it to later in the day, or eliminate it entirely, if feasible; and

- If you have routine, sit-down rounds with case managers each morning, think about whether they get in the way of early-in-the-day discharges. If so, consider moving them to the afternoons, and focus on discussing the next day’s potential discharges rather than discharges for the current day.

Consider establishing targets for each of these metrics and audit performance compared with a historical baseline. For example, the goal might be that the “probable discharge tomorrow” order appears the day before discharge in 50% of hospitalist patients, and the discharge summary is prepared the day before in 30%. These things help ensure other hospital staff members realize discharge is possible or likely and can significantly reduce discharges that are a surprise to nurses and others.

There is nothing magic about the bulleted protocol above. I’m offering it as only one potential idea to improve throughput, and you might want to pursue an entirely different strategy.

The Flip Side

Two closely related issues come up when working on getting discharge orders written early in the day. The first is that some late-afternoon discharges are in reality very early discharges that might have otherwise waited until the next day. It is important to stress that not all discharge orders are written early, and that hospitalists should not hold on to patients who could be discharged late in the day and instead release them the next morning to make their statistics look better.

The other related point is that a declining length of stay and discharging early in the day begin to compete with each other at some point. From a bed management perspective, the theoretical optimal length of stay means discharging patients the moment they are ready and not waiting until the next morning. This means discharging around the clock without regard to the time of day, and that would look terrible when analyzed from the perspective of the portion of discharge orders written early in the day—not to mention it would be very unpleasant for patients asked to leave at night. So I’m not suggesting that we should be discharging patients around the clock, but I just want to point out the tension between length of stay and writing discharge orders early in the day. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospital practice management consulting firm. He is part of the faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official SHM position.

In the what-have-you-done-for-me-lately category, many hospitalists are expected to really ramp up their efforts to improve their hospital’s throughput. So many hospital executives, who not long ago were dazzled by impressive reductions in lengths of stay and cost per case attributable to hospitalists, seem to have turned their attention to discharging patients early in the day. To some hospitalists who still expect gratitude for things done in the past, it seems terribly unfair that administrators now expect us to attend to this new metric. And, by the way, don’t let discharging patients early in the day interfere with improvements in quality metrics, patient satisfaction, and documentation.

Because of these increasing demands on hospitalists, we might feel sorry for ourselves. I do sometimes. But I also know that if we became hospital executives—and some of us have—we would expect the same of hospitalists in our institutions.

I’m struck by how often hospitalists, particularly those not in leadership positions, fail to understand why it matters so much to the execs that discharge orders are written early in the day. For them, I’ll try to provide a brief explanation.

Why It Matters

An increasing number of hospitals are operating with all of their staffed beds fully occupied. Many end up with patients boarding in the ED or ICU because no “regular” beds are available. And hospitals really suffer financially when they have to cancel elective admissions, such as surgeries, because no beds are available for the patient postop.

Hospitals could build more beds to increase their capacity, but that requires a long time and something along the lines of $1 million per bed. Where could they get the financing in today’s market? The other option is to shorten the length of time a patient occupies a bed so that more patients can be served using the existing inventory.

In nearly every hospital, the biggest bed crunch occurs in the afternoon. This is the time patients are ready to leave the post-anesthesia care unit or ED and move to their “floor” bed. If patients being discharged that day haven’t left yet, gridlock occurs. Costs of the gridlock are spread throughout the hospital, notably in the ED, which suffers because of the resulting increased lengths of stay and reduced throughput. This isn’t just an economic issue for the hospital; patients are adversely affected, too.

Even if your hospital has spare beds, early discharge still matters. If the discharge day isn’t managed well and patients routinely leave late in the afternoon, the hospital will have to spend more on evening-shift nursing staff.

It makes sense to look at every step that must occur prior to a patient vacating their room on the day of discharge. The time that the doctor actually writes the discharge order is one of the most critical, rate-limiting steps in the discharge process, so helpful executives suggest we organize our rounds to see the potential discharges first, then get around to seeing the patients who are really sick. I think most hospitalists, including me, find it really difficult to do this. If you’re in this category, you might consider starting your rounds earlier in the day.

Consider Rounding Earlier

Starting rounds earlier is usually an unpopular idea. Many groups refuse to consider it. If you are in a group that works day (rounding) shifts with specified start and stop times, coming in before the start of your shift to begin rounding is just donating uncompensated time to the practice. That is one of many reasons I think it is best for most practices to avoid specified start and stop times for their day shifts. Instead, I think it is reasonable for each doctor to decide when to start and stop work each day depending on the workload. So on days you have a higher-than-usual number of expected discharges or sick patients, you would probably choose to start earlier. And when patient volumes are low, you might choose to start later. The same is true of when you choose to leave for the day. Choosing to start earlier in the day should mean that you can wrap things up earlier on most days.

For a lot of hospitalists, routinely starting rounds earlier would be OK as long as they can finish earlier. But there are some for whom this is really tough or impossible, such as those who need to take their kids to school before work each morning. Rounding early won’t do any good if the hospital doesn’t ensure test results and other information is available early.

A practice could choose to undertake an initiative as simple as the following steps to support improvements in writing most discharge orders early in the day:

- Encourage starting rounds earlier (e.g., 7 a.m.) on most days;

- Whenever possible, prepare discharge summaries the day before;

- As often as possible, write in the order section “probable discharge tomorrow” one day before planned discharges;

- Keep routine morning conferences, such as signout, as short as possible; move it to later in the day, or eliminate it entirely, if feasible; and

- If you have routine, sit-down rounds with case managers each morning, think about whether they get in the way of early-in-the-day discharges. If so, consider moving them to the afternoons, and focus on discussing the next day’s potential discharges rather than discharges for the current day.

Consider establishing targets for each of these metrics and audit performance compared with a historical baseline. For example, the goal might be that the “probable discharge tomorrow” order appears the day before discharge in 50% of hospitalist patients, and the discharge summary is prepared the day before in 30%. These things help ensure other hospital staff members realize discharge is possible or likely and can significantly reduce discharges that are a surprise to nurses and others.

There is nothing magic about the bulleted protocol above. I’m offering it as only one potential idea to improve throughput, and you might want to pursue an entirely different strategy.

The Flip Side

Two closely related issues come up when working on getting discharge orders written early in the day. The first is that some late-afternoon discharges are in reality very early discharges that might have otherwise waited until the next day. It is important to stress that not all discharge orders are written early, and that hospitalists should not hold on to patients who could be discharged late in the day and instead release them the next morning to make their statistics look better.

The other related point is that a declining length of stay and discharging early in the day begin to compete with each other at some point. From a bed management perspective, the theoretical optimal length of stay means discharging patients the moment they are ready and not waiting until the next morning. This means discharging around the clock without regard to the time of day, and that would look terrible when analyzed from the perspective of the portion of discharge orders written early in the day—not to mention it would be very unpleasant for patients asked to leave at night. So I’m not suggesting that we should be discharging patients around the clock, but I just want to point out the tension between length of stay and writing discharge orders early in the day. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospital practice management consulting firm. He is part of the faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official SHM position.

Bonus-Pay Bonanza

Although there is a lot of debate about the effectiveness of pay-for-performance (P4P) plans, I think the plans are only going to increase in the foreseeable future.

We need more research to tell us the relative impact of public reporting of performance data and P4P programs. Most importantly, the details of how these plans are set up, how and what they measure, and the dollar amount involved will have everything to do with whether they are successful in improving the value of care we provide.

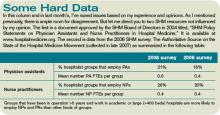

SHM’S Practice Management Committee conducted a mini-survey of hospitalist group leaders in 2006. Here are some of the key findings.

P4P Prevalence

Forty-one percent (60 out of 146) of hospital medicine group (HMG) leaders reported their groups have a quality-incentive program. Of those HMG leaders more likely to report participation in a quality-incentive program:

- 60% were at hospitals participating in a P4P program;

- 50% were at multispecialty/PCP medical groups; and

- 50% were in the Southern region.

Of those HMG leaders less likely to report participation in P4P programs, 28% were at academic programs and 31% were at local hospitalist-only groups.

Group vs. Individual Incentives

Of the HMG leaders participating in a quality-incentive program:

- 43% reported it was an individual incentive;

- 35% reported it was a group incentive;

- 10% reported the plan had elements of both individual and group incentives; and

- 12% were not sure if their plans had individual or group incentives.

Basis of Quality Targets

Of the HMG leaders reporting that they participate in a quality-incentive program (respondents could indicate one or more answers):

- 60% of the programs have targets based on national benchmarks;

- 23% have targets based on local or regional benchmarks;

- 37% have targets based on their hospital’s previous experience; and

- 47% have targets based on improvement over a baseline.

Maximum Impact of Incentives

Of the HMG leaders reporting that they participate in a quality-incentive program:

- 16% report the maximum impact is less than 3%;

- 24% report the maximum impact is from 3% to 7%;

- 35% report the maximum impact is from 8% to 10%;

- 17% report the maximum impact is from 11% to 20%;

- 3% report the maximum impact is more than 20%; and

- 5% report they do not know the maximum impact.

Group vs. Individual Incentives

Of the HMG leaders reporting that they participate in a quality-incentive program:

- 61% said they have received an incentive payment;

- 37% have not received an incentive payment; and

- 2% were unsure if they have received an incentive payment.

Quality Metrics

The most common metrics used in P4P programs, based on 29 responses to the SHM survey:

- 93% of HM programs have metrics based on The Joint Commission’s (JCAHO) heart failure measures;

- 86% have metrics based on JCAHO pneumonia measures;

- 79% have metrics based on JCAHO myocardial infarction measures;

- 28% have metrics based on a measure of medication reconciliation;

- 24% have metrics based on avoidance of unapproved abbreviations;

- 24% have metrics based on 100,000 Lives Campaign measures;

- 21% have metrics based on patient satisfaction measures;

- 17% have metrics based on transitions-of-care measures;

- 10% have metrics based on throughput measures;

- 7% have metrics based on end-of-life measures;

- 7% have metrics based on “good citizenship” measures;

- 7% have metrics based on mortality rate measures; and

- 7% have metrics based on readmission rate measures.

The most common metrics used in quality-incentive programs, based on 45 responses to SHM’s survey:

- 73% of programs use JCAHO heart failure measures;

- 73% use “good citizenship” measures;

- 73% use patient satisfaction measures;

- 67% use JCAHO pneumonia measures;

- 51% use transitions-of-care measures;

- 44% use JCAHO M.I. measures;

- 31% use throughput measures;

- 27% use avoidance of unapproved abbreviations;

- 24% use a measure based on medication reconciliation;

- 11% use 100,000 Lives Campaign measures;

- 9% use readmission rate measures;

- 7% use mortality rate measures; and

- 2% use end-of-life measures.

Recommendations

The prevalence of hospitalist quality-based compensation plans is continuing to grow rapidly, but the details of the plans’ structure will govern whether they benefit our patients, improve the overall value of the care we provide, and serve as a meaningful component of our compensation. I suggest each practice consider implementing plans with the following attributes:

A total dollar amount available for performance that is enough to influence hospitalist behavior. I think quality incentives should compose as much as 15% to 20% of a hospitalist’s annual income. Plans connecting quality performance to equal to or less than 7% of annual compensation (the case for 40% of groups in the above survey) rarely are effective.

Money vs. metrics. It usually is better to establish a plan based on a sliding scale of improved performance rather than a single threshold. For example, if all of the bonus money is available for a 10% improvement in performance, consider providing 10% of the total available money for each 1% improvement in performance.

Degree of difficulty. Performance thresholds should be set so that hospitalists need to change their practices to achieve them, but not so far out of reach that hospitalists give up on them. This can get tricky. Many practices set thresholds that are very easy to reach (e.g., they may be near the current level of performance).

Metrics for which trusted data is readily available. In most cases, this means using data already being collected. Avoid hard-to-track metrics, as they are likely to lead to disagreements about their accuracy.

Group vs. individual measures. Most performance metrics can’t be clearly attributed to one hospitalist as compared to another. For example, who gets the credit or blame for Ms. Smith getting or not getting a pneumovax? The majority of performance metrics are best measured and paid on a group basis. Some metrics, such as documenting medicine reconciliation on admission and discharge, can be effectively attributed to a single hospitalist and could be paid on an individual basis.

Small number of metrics, A meaningfully large amount of money should be connected to each one. Don’t make the mistake of having a $10,000 per doctor annual quality bonus pool divided among 20 metrics (each metric would pay a maximum of $500 per year).

Rotating metrics. Consider an annual meeting with members of your hospital’s administration to jointly establish the metrics used in the hospitalist quality incentive for that year. It is reasonable to change the metrics periodically.

It seems to me P4P programs are in their infancy, and will continue to evolve rapidly. Plans that fail to improve outcomes enough to justify the complexity of implementing, tracking, and paying for them will disappear slowly. (I wonder if payment for pneumovax administration during the hospital stay will be in this category.) And new, more effective, and more valuable programs will be developed.

Hospitalist practices will need to be nimble to keep pace with all of this change. Although SHM can alert you to how new P4P initiatives might affect your practice, and even recommend methods to improve your performance, you and your hospitalist colleagues still will have a lot of work to operationalize these programs in your practice. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm. He is part of the faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Although there is a lot of debate about the effectiveness of pay-for-performance (P4P) plans, I think the plans are only going to increase in the foreseeable future.

We need more research to tell us the relative impact of public reporting of performance data and P4P programs. Most importantly, the details of how these plans are set up, how and what they measure, and the dollar amount involved will have everything to do with whether they are successful in improving the value of care we provide.

SHM’S Practice Management Committee conducted a mini-survey of hospitalist group leaders in 2006. Here are some of the key findings.

P4P Prevalence

Forty-one percent (60 out of 146) of hospital medicine group (HMG) leaders reported their groups have a quality-incentive program. Of those HMG leaders more likely to report participation in a quality-incentive program:

- 60% were at hospitals participating in a P4P program;

- 50% were at multispecialty/PCP medical groups; and

- 50% were in the Southern region.

Of those HMG leaders less likely to report participation in P4P programs, 28% were at academic programs and 31% were at local hospitalist-only groups.

Group vs. Individual Incentives

Of the HMG leaders participating in a quality-incentive program:

- 43% reported it was an individual incentive;

- 35% reported it was a group incentive;

- 10% reported the plan had elements of both individual and group incentives; and

- 12% were not sure if their plans had individual or group incentives.

Basis of Quality Targets

Of the HMG leaders reporting that they participate in a quality-incentive program (respondents could indicate one or more answers):

- 60% of the programs have targets based on national benchmarks;

- 23% have targets based on local or regional benchmarks;

- 37% have targets based on their hospital’s previous experience; and

- 47% have targets based on improvement over a baseline.

Maximum Impact of Incentives

Of the HMG leaders reporting that they participate in a quality-incentive program:

- 16% report the maximum impact is less than 3%;

- 24% report the maximum impact is from 3% to 7%;

- 35% report the maximum impact is from 8% to 10%;

- 17% report the maximum impact is from 11% to 20%;

- 3% report the maximum impact is more than 20%; and

- 5% report they do not know the maximum impact.

Group vs. Individual Incentives

Of the HMG leaders reporting that they participate in a quality-incentive program:

- 61% said they have received an incentive payment;

- 37% have not received an incentive payment; and

- 2% were unsure if they have received an incentive payment.

Quality Metrics

The most common metrics used in P4P programs, based on 29 responses to the SHM survey:

- 93% of HM programs have metrics based on The Joint Commission’s (JCAHO) heart failure measures;

- 86% have metrics based on JCAHO pneumonia measures;

- 79% have metrics based on JCAHO myocardial infarction measures;

- 28% have metrics based on a measure of medication reconciliation;

- 24% have metrics based on avoidance of unapproved abbreviations;

- 24% have metrics based on 100,000 Lives Campaign measures;

- 21% have metrics based on patient satisfaction measures;

- 17% have metrics based on transitions-of-care measures;

- 10% have metrics based on throughput measures;

- 7% have metrics based on end-of-life measures;

- 7% have metrics based on “good citizenship” measures;

- 7% have metrics based on mortality rate measures; and

- 7% have metrics based on readmission rate measures.

The most common metrics used in quality-incentive programs, based on 45 responses to SHM’s survey:

- 73% of programs use JCAHO heart failure measures;

- 73% use “good citizenship” measures;

- 73% use patient satisfaction measures;

- 67% use JCAHO pneumonia measures;

- 51% use transitions-of-care measures;

- 44% use JCAHO M.I. measures;

- 31% use throughput measures;

- 27% use avoidance of unapproved abbreviations;

- 24% use a measure based on medication reconciliation;

- 11% use 100,000 Lives Campaign measures;

- 9% use readmission rate measures;

- 7% use mortality rate measures; and

- 2% use end-of-life measures.

Recommendations

The prevalence of hospitalist quality-based compensation plans is continuing to grow rapidly, but the details of the plans’ structure will govern whether they benefit our patients, improve the overall value of the care we provide, and serve as a meaningful component of our compensation. I suggest each practice consider implementing plans with the following attributes:

A total dollar amount available for performance that is enough to influence hospitalist behavior. I think quality incentives should compose as much as 15% to 20% of a hospitalist’s annual income. Plans connecting quality performance to equal to or less than 7% of annual compensation (the case for 40% of groups in the above survey) rarely are effective.

Money vs. metrics. It usually is better to establish a plan based on a sliding scale of improved performance rather than a single threshold. For example, if all of the bonus money is available for a 10% improvement in performance, consider providing 10% of the total available money for each 1% improvement in performance.

Degree of difficulty. Performance thresholds should be set so that hospitalists need to change their practices to achieve them, but not so far out of reach that hospitalists give up on them. This can get tricky. Many practices set thresholds that are very easy to reach (e.g., they may be near the current level of performance).

Metrics for which trusted data is readily available. In most cases, this means using data already being collected. Avoid hard-to-track metrics, as they are likely to lead to disagreements about their accuracy.

Group vs. individual measures. Most performance metrics can’t be clearly attributed to one hospitalist as compared to another. For example, who gets the credit or blame for Ms. Smith getting or not getting a pneumovax? The majority of performance metrics are best measured and paid on a group basis. Some metrics, such as documenting medicine reconciliation on admission and discharge, can be effectively attributed to a single hospitalist and could be paid on an individual basis.

Small number of metrics, A meaningfully large amount of money should be connected to each one. Don’t make the mistake of having a $10,000 per doctor annual quality bonus pool divided among 20 metrics (each metric would pay a maximum of $500 per year).

Rotating metrics. Consider an annual meeting with members of your hospital’s administration to jointly establish the metrics used in the hospitalist quality incentive for that year. It is reasonable to change the metrics periodically.

It seems to me P4P programs are in their infancy, and will continue to evolve rapidly. Plans that fail to improve outcomes enough to justify the complexity of implementing, tracking, and paying for them will disappear slowly. (I wonder if payment for pneumovax administration during the hospital stay will be in this category.) And new, more effective, and more valuable programs will be developed.

Hospitalist practices will need to be nimble to keep pace with all of this change. Although SHM can alert you to how new P4P initiatives might affect your practice, and even recommend methods to improve your performance, you and your hospitalist colleagues still will have a lot of work to operationalize these programs in your practice. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm. He is part of the faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Although there is a lot of debate about the effectiveness of pay-for-performance (P4P) plans, I think the plans are only going to increase in the foreseeable future.

We need more research to tell us the relative impact of public reporting of performance data and P4P programs. Most importantly, the details of how these plans are set up, how and what they measure, and the dollar amount involved will have everything to do with whether they are successful in improving the value of care we provide.

SHM’S Practice Management Committee conducted a mini-survey of hospitalist group leaders in 2006. Here are some of the key findings.

P4P Prevalence

Forty-one percent (60 out of 146) of hospital medicine group (HMG) leaders reported their groups have a quality-incentive program. Of those HMG leaders more likely to report participation in a quality-incentive program:

- 60% were at hospitals participating in a P4P program;

- 50% were at multispecialty/PCP medical groups; and

- 50% were in the Southern region.

Of those HMG leaders less likely to report participation in P4P programs, 28% were at academic programs and 31% were at local hospitalist-only groups.

Group vs. Individual Incentives

Of the HMG leaders participating in a quality-incentive program:

- 43% reported it was an individual incentive;

- 35% reported it was a group incentive;

- 10% reported the plan had elements of both individual and group incentives; and

- 12% were not sure if their plans had individual or group incentives.

Basis of Quality Targets

Of the HMG leaders reporting that they participate in a quality-incentive program (respondents could indicate one or more answers):

- 60% of the programs have targets based on national benchmarks;

- 23% have targets based on local or regional benchmarks;

- 37% have targets based on their hospital’s previous experience; and

- 47% have targets based on improvement over a baseline.

Maximum Impact of Incentives

Of the HMG leaders reporting that they participate in a quality-incentive program:

- 16% report the maximum impact is less than 3%;

- 24% report the maximum impact is from 3% to 7%;

- 35% report the maximum impact is from 8% to 10%;

- 17% report the maximum impact is from 11% to 20%;

- 3% report the maximum impact is more than 20%; and

- 5% report they do not know the maximum impact.

Group vs. Individual Incentives

Of the HMG leaders reporting that they participate in a quality-incentive program:

- 61% said they have received an incentive payment;

- 37% have not received an incentive payment; and

- 2% were unsure if they have received an incentive payment.

Quality Metrics

The most common metrics used in P4P programs, based on 29 responses to the SHM survey:

- 93% of HM programs have metrics based on The Joint Commission’s (JCAHO) heart failure measures;

- 86% have metrics based on JCAHO pneumonia measures;

- 79% have metrics based on JCAHO myocardial infarction measures;

- 28% have metrics based on a measure of medication reconciliation;

- 24% have metrics based on avoidance of unapproved abbreviations;

- 24% have metrics based on 100,000 Lives Campaign measures;

- 21% have metrics based on patient satisfaction measures;

- 17% have metrics based on transitions-of-care measures;

- 10% have metrics based on throughput measures;

- 7% have metrics based on end-of-life measures;

- 7% have metrics based on “good citizenship” measures;

- 7% have metrics based on mortality rate measures; and

- 7% have metrics based on readmission rate measures.

The most common metrics used in quality-incentive programs, based on 45 responses to SHM’s survey:

- 73% of programs use JCAHO heart failure measures;

- 73% use “good citizenship” measures;

- 73% use patient satisfaction measures;

- 67% use JCAHO pneumonia measures;

- 51% use transitions-of-care measures;

- 44% use JCAHO M.I. measures;

- 31% use throughput measures;

- 27% use avoidance of unapproved abbreviations;

- 24% use a measure based on medication reconciliation;

- 11% use 100,000 Lives Campaign measures;

- 9% use readmission rate measures;

- 7% use mortality rate measures; and

- 2% use end-of-life measures.

Recommendations

The prevalence of hospitalist quality-based compensation plans is continuing to grow rapidly, but the details of the plans’ structure will govern whether they benefit our patients, improve the overall value of the care we provide, and serve as a meaningful component of our compensation. I suggest each practice consider implementing plans with the following attributes:

A total dollar amount available for performance that is enough to influence hospitalist behavior. I think quality incentives should compose as much as 15% to 20% of a hospitalist’s annual income. Plans connecting quality performance to equal to or less than 7% of annual compensation (the case for 40% of groups in the above survey) rarely are effective.

Money vs. metrics. It usually is better to establish a plan based on a sliding scale of improved performance rather than a single threshold. For example, if all of the bonus money is available for a 10% improvement in performance, consider providing 10% of the total available money for each 1% improvement in performance.

Degree of difficulty. Performance thresholds should be set so that hospitalists need to change their practices to achieve them, but not so far out of reach that hospitalists give up on them. This can get tricky. Many practices set thresholds that are very easy to reach (e.g., they may be near the current level of performance).

Metrics for which trusted data is readily available. In most cases, this means using data already being collected. Avoid hard-to-track metrics, as they are likely to lead to disagreements about their accuracy.

Group vs. individual measures. Most performance metrics can’t be clearly attributed to one hospitalist as compared to another. For example, who gets the credit or blame for Ms. Smith getting or not getting a pneumovax? The majority of performance metrics are best measured and paid on a group basis. Some metrics, such as documenting medicine reconciliation on admission and discharge, can be effectively attributed to a single hospitalist and could be paid on an individual basis.

Small number of metrics, A meaningfully large amount of money should be connected to each one. Don’t make the mistake of having a $10,000 per doctor annual quality bonus pool divided among 20 metrics (each metric would pay a maximum of $500 per year).

Rotating metrics. Consider an annual meeting with members of your hospital’s administration to jointly establish the metrics used in the hospitalist quality incentive for that year. It is reasonable to change the metrics periodically.

It seems to me P4P programs are in their infancy, and will continue to evolve rapidly. Plans that fail to improve outcomes enough to justify the complexity of implementing, tracking, and paying for them will disappear slowly. (I wonder if payment for pneumovax administration during the hospital stay will be in this category.) And new, more effective, and more valuable programs will be developed.

Hospitalist practices will need to be nimble to keep pace with all of this change. Although SHM can alert you to how new P4P initiatives might affect your practice, and even recommend methods to improve your performance, you and your hospitalist colleagues still will have a lot of work to operationalize these programs in your practice. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm. He is part of the faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Staffing Strategies

One of the most difficult challenges in staffing a hospitalist practice is handling the unpredictable daily fluctuations in patient volume. It isn’t difficult to decide how many hospitalists will work each day to handle the average number of daily visits (aka encounters), but the actual number of visits on any given day is almost always significantly different than the average. I think many groups could more effectively handle day-to-day variations in workload by eliminating predetermined lengths of the shifts that the doctors work. It isn’t a perfect strategy, but it is worth some consideration by nearly any practice. Let me explain.

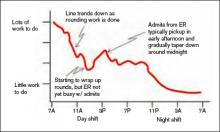

First, think about how the workload for a typical day might be represented. For many or most practices it often looks something like the wavy line in Figure 1. (See Figure 1, p. 52.)

Of course, the line representing a day’s work will be different every day, but I’ve tried to draw it in a way that represents a typical day.

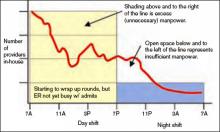

In Figure 2 (see p. 52), I’ve added horizontal bars to represent a common way that groups might schedule four daytime doctors who each work 7 a.m. to 7 p.m., and one night doctor working 7 p.m. to 7 a.m. The four horizontal bars represent the four day doctors, and the one horizontal bar at the bottom right represents the one night doctor. Ideally, the manpower (horizontal bars) should match the workload (wavy line) every hour of the day.

This graph shows that—at least for this particular day—there are many hours in the afternoon when there is excess manpower. The doctors may be sitting around waiting for their shift to end or waiting to see if it will suddenly get busy again. We all know that happens unpredictably. And from about 7 p.m. to about 11:30 p.m., the single night doctor has more work than he/she can reasonably handle.

In fact, there probably isn’t ever a day when the work that needs to be done is just the right amount for all four doctors from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. with a sudden drop at 7 p.m. that is just right for one doctor for the next 12 hours. Because the doctors have scheduled themselves to work 12-hour shifts, they know in advance that their manpower will quite regularly fail to match the workload for that day.

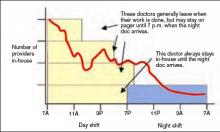

Groups have devised a number of strategies to try to get manpower to more closely match the unpredictable workload for a given day. These include having a member of the group available on standby (often called “jeopardy”) for that day; this physician comes in only if it is unusually busy. Some groups have a patient volume cap to prevent the practice from becoming too busy. I think a cap is a poor strategy that should be used only as a last resort, and I will discuss this in detail in a future column. Other groups have a swing shift from late in the afternoon until around 11 p.m. or so to help with evening admits and cross cover. And an often overlooked but potentially valuable strategy is to eliminate clearly specified start and stop times for the shifts that the doctors work. For an idea of what that might look like, see Figure 3 (p. 52).

Notice that the right-hand side of each yellow bar in Figures 2 and 3 is indistinct. That is meant to show that the precise time that the doctor leaves varies, depending on the day’s workload. That way the manpower can be adjusted from one day to the next to more closely match the workload than if the doctors work fixed shifts of a specified duration. On some days, all of the doctors may stay 12 hours or more, but on many days at least some of the doctors will end up leaving in less than 12 hours. If all day doctors work a 12-hour shift, they have provided 48 hours—four doctors at 12 hours each—of physician manpower, but if there is some flexibility about when the doctors leave, the same four day doctors could provide between about 34 and 52 hours of manpower, depending on the day’s workload.

If your practice is contracted to keep a doctor in the hospital around the clock, you will probably need the night doctor and at least one day doctor to stay around—even if it is a slow day. But the other doctors might be able to leave when their work is done. And it is also reasonable for some groups to eliminate precise times that the doctors start working in the morning each day, though they might be required to be available by pager by a specified time in the morning.

One common concern about such a system is how to handle issues that arise with the patients cared for by a doctor who has left. I think it is best for the doctor to stay available by pager and handle simple issues by phone. For more complicated issues (e.g., a patient who needs attention at the bedside) the doctor could either come back to the hospital or phone another member of the practice (e.g., the doctor required to stay at least 12 hours that day) and see if he or she can handle the emergency.

All of the specifics of a system that allows doctors to leave when their work is done rather than according to shifts of a predetermined number of hours would be too long for this column. But they aren’t complicated, and given the variability that exists in the number of daily patient visits to any hospitalist practice, the application of this kind of approach is well worth considering. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is a co-founder and past-president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

One of the most difficult challenges in staffing a hospitalist practice is handling the unpredictable daily fluctuations in patient volume. It isn’t difficult to decide how many hospitalists will work each day to handle the average number of daily visits (aka encounters), but the actual number of visits on any given day is almost always significantly different than the average. I think many groups could more effectively handle day-to-day variations in workload by eliminating predetermined lengths of the shifts that the doctors work. It isn’t a perfect strategy, but it is worth some consideration by nearly any practice. Let me explain.

First, think about how the workload for a typical day might be represented. For many or most practices it often looks something like the wavy line in Figure 1. (See Figure 1, p. 52.)

Of course, the line representing a day’s work will be different every day, but I’ve tried to draw it in a way that represents a typical day.

In Figure 2 (see p. 52), I’ve added horizontal bars to represent a common way that groups might schedule four daytime doctors who each work 7 a.m. to 7 p.m., and one night doctor working 7 p.m. to 7 a.m. The four horizontal bars represent the four day doctors, and the one horizontal bar at the bottom right represents the one night doctor. Ideally, the manpower (horizontal bars) should match the workload (wavy line) every hour of the day.

This graph shows that—at least for this particular day—there are many hours in the afternoon when there is excess manpower. The doctors may be sitting around waiting for their shift to end or waiting to see if it will suddenly get busy again. We all know that happens unpredictably. And from about 7 p.m. to about 11:30 p.m., the single night doctor has more work than he/she can reasonably handle.

In fact, there probably isn’t ever a day when the work that needs to be done is just the right amount for all four doctors from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. with a sudden drop at 7 p.m. that is just right for one doctor for the next 12 hours. Because the doctors have scheduled themselves to work 12-hour shifts, they know in advance that their manpower will quite regularly fail to match the workload for that day.

Groups have devised a number of strategies to try to get manpower to more closely match the unpredictable workload for a given day. These include having a member of the group available on standby (often called “jeopardy”) for that day; this physician comes in only if it is unusually busy. Some groups have a patient volume cap to prevent the practice from becoming too busy. I think a cap is a poor strategy that should be used only as a last resort, and I will discuss this in detail in a future column. Other groups have a swing shift from late in the afternoon until around 11 p.m. or so to help with evening admits and cross cover. And an often overlooked but potentially valuable strategy is to eliminate clearly specified start and stop times for the shifts that the doctors work. For an idea of what that might look like, see Figure 3 (p. 52).

Notice that the right-hand side of each yellow bar in Figures 2 and 3 is indistinct. That is meant to show that the precise time that the doctor leaves varies, depending on the day’s workload. That way the manpower can be adjusted from one day to the next to more closely match the workload than if the doctors work fixed shifts of a specified duration. On some days, all of the doctors may stay 12 hours or more, but on many days at least some of the doctors will end up leaving in less than 12 hours. If all day doctors work a 12-hour shift, they have provided 48 hours—four doctors at 12 hours each—of physician manpower, but if there is some flexibility about when the doctors leave, the same four day doctors could provide between about 34 and 52 hours of manpower, depending on the day’s workload.

If your practice is contracted to keep a doctor in the hospital around the clock, you will probably need the night doctor and at least one day doctor to stay around—even if it is a slow day. But the other doctors might be able to leave when their work is done. And it is also reasonable for some groups to eliminate precise times that the doctors start working in the morning each day, though they might be required to be available by pager by a specified time in the morning.

One common concern about such a system is how to handle issues that arise with the patients cared for by a doctor who has left. I think it is best for the doctor to stay available by pager and handle simple issues by phone. For more complicated issues (e.g., a patient who needs attention at the bedside) the doctor could either come back to the hospital or phone another member of the practice (e.g., the doctor required to stay at least 12 hours that day) and see if he or she can handle the emergency.