User login

Irritable bowel syndrome: Minimize testing, let symptoms guide treatment

- For patients aged <50 years without alarm symptoms, diagnostic testing is unnecessary. Consider celiac sprue testing for patients with diarrhea (C).

- Treatment is indicated when both the patient with irritable bowel syndrome and the physician agree that quality of life has been diminished (C). The goal of therapy is to alleviate global IBS symptoms (abdominal discomfort, bloating, and altered bowel habits that are life-impacting) (C).

- Tegaserod, a 5HT4 receptor agonist, is more effective than placebo at relieving global IBS symptoms in women with constipation (A). Its effectiveness in men is unknown.

- Alosetron, a 5HT3 receptor antagonist, is more effective than placebo at relieving global IBS symptoms in women with diarrhea (A).

- Behavior therapy–relaxation therapy, hypnotherapy, or cognitive therapy–is more effective than placebo at relieving individual symptoms, but no data are available for quality-of-life improvement (B).

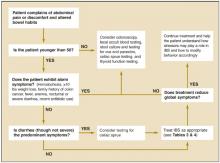

An extensive and expensive evaluation for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) can be avoided if your patient is aged <50 years and is not experiencing alarm symptoms (hematochezia, 10 lbs weight loss, fever, anemia, nocturnal or severe diarrhea), has not recently taken antibiotics, and has no family history of colon cancer. An algorithm ( Figure ) indicates when work-up is needed and what it should entail.

Newer medications that act on 5HT receptors have proven effective in improving quality of life (global symptom reduction). Evidence supports the use of several traditional medications to reduce individual symptoms of IBS, but not for global symptom reduction.

FIGURE

Evaluating possible irritable bowel syndrome

Who gets irritable bowel syndrome?

Ten percent to 15% of the North American population has IBS, and twice as many women as men have it.1 Symptoms usually begin before the age of 35 years, and many patients can trace their symptoms back to childhood.2 Onset in the elderly is rare.3 The disorder is responsible for approximately 50% of referrals to gastroenterologists.4

The company IBS keeps

Comorbid psychiatric illness is common with IBS, but few patients seek psychiatric care.5 Depression, anxiety, and somatoform disorders are seen in 94% of patients with IBS. IBS is common in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome (51%), fibromyalgia (49%), temporomandibular joint syndrome (64%), and chronic pelvic pain (50%).6 IBS often follows stressful life events,5,7,8 such as a death in the family or divorce. It tends to be chronic, intermittent, and relapsing.3

The symptoms of IBS can overlap with those of other illnesses, including thyroid dysfunction (diarrhea or constipation), functional dyspepsia (abdominal pain), Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis (diarrhea, abdominal pain), celiac sprue (diarrhea), polyps and cancers (constipation or abdominal pain), and infectious diarrhea.

Elusive physiologic mechanism

Several physiologic mechanisms have been proposed for IBS symptoms: altered gut reactivity in response to luminal stimuli, hypersensitive gut with enhanced pain response, and altered brain-gut biochemical axis.9 Though the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome appear to have a physiologic basis, there are no structural or biochemical markers for the disease.

Use symptom-based criteria for diagnosis

Consider a diagnosis of IBS when a patient complains of abdominal discomfort and altered bowel habits. In the absence of a structural or biochemical marker, IBS must be diagnosed according to symptom-based criteria–such as Manning, Rome I, or Rome II–which have been developed for research and epidemiologic purposes. Though their clinical utility remains unproven, these criteria (delineated in Table 1 ) are the crux of clinical diagnosis for IBS.4,10-14 Subtypes of IBS have been described (diarrheapredominant IBS or constipation-predominant IBS), but they are not diagnostically useful, since the treatment goal is improved quality of life.

TABLE 1

Symptom-based criteria for irritable bowel syndrome

| Symptom-based criteria | Symptoms | Sn | Sp | PV+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manning4,10,13,14 |

| 42%–90% | 70%–100% | 74% |

| Rome I4,10,13 |

| 65%–84% | 100% | 69%–100% |

| Rome II11-13 |

| 49%-65%* | 100%* | 69%-100%* |

| Supportive symptoms | ||||

| Fewer than 3 bowel movements per week | ||||

| More than 3 bowel movements per day | ||||

| Hard or lumpy stools | ||||

| *Found to have similar sensitivity and specificity to Rome I.14 | ||||

| Sn, sensitivity; Sp, specificity; PV+, positive predictive value | ||||

Dubious value of diagnostic tests

The literature regarding the value of diagnostic testing for IBS is controversial. Symptom-based criteria have varied in many studies, as have the criteria used to enroll patients and the measured outcomes of treatment (reduction in abdominal pain, in diarrhea, or in constipation, or improvement in quality of life). Because of these discrepancies, it is difficult to apply the literature clinically. Of the 6 landmark studies that considered the value of diagnostic testing for IBS patients,15-20 only 2 compared IBS patients with groups of healthy controls.17,19

Test results yield little. Most research in this area has compared the prevalence of specific illnesses in the general population with the yield of positive test results for these illnesses among persons meeting the symptom-based diagnostic criteria for IBS.

Two studies15,16 determined the incidence of abnormal test results in patients who met the Manning or Rome I criteria for IBS. In these studies, most diagnostic tests yielded positive results in 2% (range, 0%-8.2%) of patients or less, except for thyroid and lactose intolerance testing. That is equivalent to the incidence in the general population. The prevalence of thyroid disorders and lactose malabsorption was higher in IBS patients (6% and 22%-26%, respectively), but prevalence in the general population is similarly higher (5%-9% and 25%). Based on these results, testing for thyroid disease or lactose malabsorption is indicated only for patients exhibiting symptoms of these disorders (fatigue/weight change or diarrhea related to diertary intake of dairy products, respectively).

An exception. Some clinicians propose that diagnostic testing for patients with IBS symptoms should be driven by the pretest probability of organic disease (prevalence) compared with the general population. Cash21 found the pretest probability of inflammatory bowel disease, colorectal cancer, and infectious diarrhea is less than 1% among IBS patients without alarm symptoms ( Table 2 ). He demonstrated that patients with IBS had a 5% pretest probability of celiac sprue compared with healthy patients (<1% prevalence). Therefore, testing for celiac sprue (eg, complete blood count, antiendomysial antibody, and antigliadin antibody) may be considered for patients with diarrhea.6,21,22 Sigmoidoscopy,15,17 rectal biopsy,17 and abdominal ultrasound18 have low positive yield in patients meeting the diagnostic criteria for IBS.

TABLE 2

Probability of organic disease in irritable bowel syndrome patients

| Disease | Pretest probability-IBS patients (%) | Prevalence-general population (%) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colitis/inflammatory inflammatory bowel disease | 0.51-0.98 | 0.3-1.2 | Structural colon lesions were detected with barium enema, colonscopy, sigmoidoscopy |

| Colon cancer | 0-0.51 | 4-6 | Structural colon lesions were detected with barium enema, colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy |

| Celiac disease | 4.67 | 0.25-0.5 | Note: celiac disease prevalence higher than in general population. |

| Gastrointestinal infection | 0-1.7 | N/A | |

| Thyroid dysfunction | 6 | 5-9 | Prevalence high in both groups |

| Lactose malabsorption | 22-26 | 25 | Prevalence high in both groups |

| Adapted from: Cash BD, Schonfeld P, Chey WD. The utility of diagnostic tests in irritable bowel syndrome patients: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97:2812-2819. | |||

| Results are from multiple studies: n=125-306. | |||

How to proceed

Those under 50 years of age who have no alarm symptoms can forgo further testing. Testing for celiac sprue and lactose malabsorption might be considered for patients with diarrhea that improves or worsens with change in diet (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C).

Threshold for treatment

Treatment for IBS is indicated when both patient and physician believe global symptoms (abdominal discomfort, bloating, altered bowel habits) have diminished the quality of life (SOR: C). The goal of treatment is to alleviate all IBS symptoms (SOR: C). Treating altered bowel habits (constipation, diarrhea, and fecal urgency) without addressing other IBS symptoms (eg, abdominal pain) is inferior treatment.23,24

Treatment options for IBS

Treatments for IBS include medications, behavior therapy, and complimentary and alternative therapies. Medications traditionally prescribed include bulking agents, anticholinergics/antispasmodics, antidiarrheals, and antidepressants. A 5HT3 receptor antagonist and a 5HT4 receptor partial agonist are now available. Table 3 summarizes the traditional treatments in terms of efficacy, strength of recommendations, and outcomes measured. Alternative and complimentary therapies appear in Table 4 .

As Brandt24 has noted, the evidence for treatment effectiveness is difficult to review and summarize, because the quality of studies has been poor. Most studies did not use healthy control groups, and the numbers of participants were small. Many studies did not use blinded placebo groups. Outcomes measured varied among the studies, with most of them measuring reductions of individual bowel symptoms (eg, diarrhea or constipation). Quality-of-life tools were used in other studies to measure reduction in global IBS symptoms (eg, IBS Quality of Life 25 ). Because of these discrepancies, there is no sound evidence for traditional therapies.

TABLE 3

Treatments for irritable bowel syndrome

| Treatment | Efficacy (NNT) | SOR (studies) | Outcomes measured | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5HT4 receptor agonist (tegaserod)23,24,26-30 | More effective than placebo at relieving global IBS symptoms in women with constipation (3.9-17) | A (4) | Global IBS symptoms, individual IBS symptoms | 83%-100% of study participants were women with IBS and constipation. Rome I and II criteria for entry. May cause diarrhea |

| 5HT4 receptor agonist(alosetron)23,24,26- 35 | More effective than placebo at relieving global IBS symptoms in women with diarrhea (2.5-8.3) | A (4) | Global IBS symptoms, individual IBS symptoms, adverse events | 82%-93% of study participants were women. Rome I and II criteria for entry. May cause severe constipation; restricted use |

| Tricylic antidepressants (trimipramine, desipramine)23,24,36- 39 | Reduces abdominal pain. No more effective than placebo at relieving gloal IBS symptoms (3.2-5) | B (6) | GI symptoms | May cause constipation; no studies done with SSRIs |

| Loperamide23,24,36-39 | Relieves diarrhea. No more effective than placebo at relieving global IBS symptoms (3.2-5) | B (3) | Global IBS symptoms, diarrhea | Constipation or paralytic ileus can occur |

| Bulking agents (corn fiber, wheat bran, psyllium, ispaghula husks, calcium polycabophil)23,24,31,40-42 | Improves constipation. No more effective than placebo in studies considering global symptom improvement (2.2-8.6) | B (13) | GI symptoms, global IBS symptoms | May increase bloating. All studiessmall numbers of patients |

| Anti-spasmodics (hyoscyamine dicyclomine)23,24,26-30 | No evidence on improvement of global IBS symptoms (5.9) | B (3) | Individual IBS and global symptoms | Studies were short, small numbers, inconsistent effectiveness. Could worsen constipation; 15 additional studies done on drugs not available in the US |

| Behavioral therapies (hypnotherapy, relaxation therapy, psychotherapy, biofeedback)23,24,44, 52-57 | More effective than placebo at relieving individuals IBS symptoms (1.4-1.9) | B (16) | GI symptoms, psychological sypmtoms | None measures global IBS symptom improvement. Small numbers of patients |

| SSRI antidepressants (paroxtetine, fluoxetine)23,24, 50-51 | Improved quality of life, decreased abdominal pain | B (16) | Abdominal | One study severe IBS, other study only 10 participants quality of life |

| SOR, strength of recommendation; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; GI, gastrointestinal; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. For an explanation of SORs. | ||||

TABLE 4

Complementary and alternative treatments for irritable bowel syndrome

| Treatment | Efficacy | SOR | Outcomes measured | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neomycin 20 | Treatment for 1 week improved symptoms of abdominal pain, diarrhea, and constipation | A | Abdominal pain, diarrhea, or constipation | Studies measuring global symptom improvement lacking |

| Peppermint oil 31,4849 | Some demonstrated improvement in abdominal pain | B | Individual IBS symptoms | Studies measuring global symptom improvement lacking |

| Guar gum 44 | Improved abdominal pain and bowel alterations | B | Study compared fiber to guar gum–equal affect on abdominal pain. Gum was better toleratEd | No placebo-controlled trials |

| Probiotics48 (lactobacillus) | Improvement of abdominal pain and flatulence | C | Abdominal pain, flatulence | Two studies with small numbers |

| Elimination diets 48 | Improvement of diarrhea | C | Diarrhea | Milk, wheat, eggs eliminated; 15%-71% improvement of diarrhea |

| Lactose and fructose avoidance 48 | Conflicting evidence results | D | No controlled studies available | |

| Pancreatic enzymes 48 | No evidence | D | Evidence lacking | |

| Ginger 48 | No evidence | D | No studies |

Medications

Strength of recommendation: A. The recently approved 5HT4 receptor agonist tegaserod (Zelnorm) is more effective than placebo at relieving global symptoms in women with constipation (number needed to treat [NNT]=3.9-17).26-30 Diarrhea can be a serious side effect.

The 5HT3 receptor antagonist alosetron (Lotronex) is more effective than placebo at relieving global IBS symptoms in women with diarrhea (NNT=2.5-8.3).31-35 Severe constipation can be an adverse effect. The prescribing of alosetron is currently restricted to physicians who participate in the manufacturer’s risk management program.

In addition to these serotoninergic agents, others in this class are being developed and undergoing clinical trials. The knowledge being gained about 5HT receptors may revolutionize the care of patients with IBS.

Strength of recommendation: B. Tricyclic antidepressants are no more effective than placebo at relieving global IBS symptoms, but they do decrease abdominal pain (NNT=3.2-5).36-39

Loperamide is no more effective than placebo at relieving IBS global symptoms, but it may be used to treat diarrhea (NNT=2.3-5).31,40-42

Bulking agents (such as calcium polycarbophil or psyllium) are no more effective than placebo at relieving IBS global symptoms, but they may decrease constipation (NNT=2.2-8.6).31,36,43-47

Peppermint oil may be helpful for abdominal pain, but global symptom reduction has not been demonstrated.31,48-49 Only a few studies have looked at the use of antispasmodic agents for IBS. They are of poor quality and used small numbers with no placebo controls.23,31,36,43

Strength of recommendation: C. There are limited studies evaluating the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) fluoxetine and paroxetine. Paroxetine was shown in 1 study to improve quality of life.50 Fluoxetine reduced abdominal pain, but did not improve quality of life.51

Behavioral and complementary/alternative therapies

Relaxation therapy, hypnotherapy, and cognitive therapy are effective at relieving individual IBS symptoms, but have not been shown to reduce global IBS symptoms (SOR: B).52-57 Other alternative therapies (eg, guar gum44 [SOR: B], ginger48 [SOR: B], and pancreatic enzymes48 [SOR: C]) have been studied, but high-quality studies considering global improvement have not been published.

The position statement of the American College of Gastroenterology on the management of IBS23 and Brandt’s systematic review of this subject24 were the starting points for this review. The majority of the references from these sources were reviewed and a Medline search was completed to identify new evidence. The Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine grades of recommendations were applied to this evidence, a care algorithm was created, summary tables were developed, and numbers needed to treat were calculated.

Promote self-awareness

Quality-of-life assessment should be done routinely in the care of IBS patients. Provide support, empathy, and basic behavior modification tools. Educate patients and their families on the theoretical biochemical basis of this illness, and help them connect symptoms with stressors, to facilitate lifestyle modification.

Correspondence

Keith B. Holten, MD, Clinton Memorial Hospital/University of Cincinnati Family Practice Residency, 825 W. Locust St., Wilmington, OH, 45177. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Saito YA, Schoenfeld P, Locke R. The epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome in North America: A systematic review. Am J Gastrenterol 2002;97:1910-1915.

2. Talley NJ, Gabriel SE, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Evans RW. Medical costs in community subjects with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 1995;109:1736-1741.

3. Maxwell PR, Mendall MA, Kumar D. Irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet 1997;350:1691-1695.

4. Fass R, Longstreth GF, Pimental M, et al. Evidence- and consensus-based practice guidelines for the diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:2081-2088.

5. Goldberg J, Davidson P. A biopsychosocial understanding of the irritable bowel syndrome: a review. Can J Psychiatry 1997;42:835-840.

6. Whitehead WE, Palsson O, Jones KR. Systematic review of the comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome with other disorders: What are the causes and implications? Gastroenterology 2002;122:1140-1156.

7. Olden KW, Drossman DA. Psychologic and psychiatric aspects of gastrointestinal disease. Med Clin North Am 2000;84:1313-1327.

8. Aaron LA, Burke MM, Buchwald D. Overlapping conditions among patients with chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, and temporomandibular disorder. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:221-227.

9. Camilleri M, Prather CM. The irritable bowel syndrome: mechanisms and a practical approach to management. Ann Internal Med 1992;116:1001-1008.

10. Paterson WG, Thompson WG, Vanner SJ, et al. Recommendations for the management of irritable bowel syndrome in family practice. JAMC 1999;161:154-160.

11. Olden KW. Diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2002;122:1701-1714.

12. Tosetti C, Stanghellini V, Corinaldesi R. The Rome II criteria for patients with functional gastroduodenal disorders. J Clin Gastroenterol 2003;37:92-93.

13. Chey WD, Olden K, Carter E, Boyle J, Drossman D, Chang L. Utility of the Rome I and Rome II criteria for irritable bowel syndrome in US women. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:2803-2811.

14. Vanner SJ, Depew WT, Paterson WG, et al. Predictive value of the Rome criteria for diagnosing the irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:2912-2917.

15. Hamm LR, Sorrells SC, Harding JP, et al. Additional investigations fail to alter the diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome in subjects fulfilling the Rome criteria. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:1279-1282.

16. Tolliver BA, Herrara JL, DiPalma JA. Evaluation of patients who meet clinical criteria for irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 1994;89:176-178.

17. MacIntosh DG, Thompson WG, Patel DP, Barr R, Guindi M. Is rectal biopsy necessary in irritable bowel syndrome? Am J Gastroenterol 1992;87:1407-1409.

18. Francis CY, Duffy JN, Whorwell PJ, Martin DF. Does routine ultrasound enhance diagnostic accuracy in irritable bowel syndrome? Am J Gastroenterol 1996;91:1348-1350.

19. Sanders DS, Carter MJ, Hurlstone DP, et al. Association of adult celiac disease with irritable bowel syndrome: a case-control study in patients fulfilling Rome II criteria referred to secondary care. Lancet 2001;358:1504-1508.

20. Pimental M, Chow EJ, Lin HC. Normalization of lactulose breath testing correlates with symptom improvement in irritable bowel syndrome; a double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:412-419.

21. Cash BD, Schonfeld P, Chey WD. The utility of diagnostic tests in irritable bowel syndrome patients: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:2812-2819.

22. O’Leary CO, Wieneke P, Buckley S, et al. Celiac disease and irritable bowel-type symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:1463-1467.

23. American College of Gastroenterology Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders Task Force. Evidence-based position statement on the management of irritable bowel syndrome in North America. Am J Gastrenterol 2002;97:s1-s5.

24. Brandt LJ, Bjorkman D, Fennerty MB, Locke GR, Olden K, et al. Systematic review on the management of irritable bowel syndrome in north America. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:s7-s26.

25. Drossman DA, Patrick DL, Whitehead WE, NE, et al. Further validation of the IBS-QOL: a disease-specific quality-of-life questionnaire. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:999-1007.

26. Jones BW, Moore DJ, Robinson SM, Song F. A systematic review of tegaserod for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Pharm Therapeutics 2002;27:343-352.

27. Novick J, Miner P, Krause R, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of tegaserod in female patients suffering from irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002;16:1877-1888.

28. Muller-Lissner SA, Fumagalli I, Bardhan KD, et al. Tegaserod, a 5-HT(4) receptor partial agonist, relieves symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome patients with abdominal pain, bloating and constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001;15:1655-1666.

29. Kellow J, Lee OY, Chang FY, et al. An Asia-Pacific, double blind, placebo controlled, randomised study to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of tegaserod in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 2003;52:671-676.

30. Jones RH, Holtmann G, Rodrigo L, Ehsanullah, Crompton PM, Jacques LA, Mills JG. Alosetron relieves pain and improves bowel function compared with mebeverine in female nonconstipated irritable bowel syndrome patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1999;13:1419-1427.

31. Jailwala J, Imperiale TF, Kroeneke K. Pharmacologic treatment of the irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. Ann Intern Med 2000;133:136-147.

32. Cremonini F, Delgado-Aros S, Camilleri M. Efficacy of alosetron in irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2002;15:79-86.

33. Camilleri M, Northcutt AR, Kong S, Dukes GE, McSorley D, Mangel AW. Efficacy and safety of alosetron in women with irritable bowel syndrome: a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2000;355:1035-1040.

34. Camilleri M, Mayer EA, Drossman DA, et al. Improvement in pain and bowel function in female irritable bowel patients with alosetron, a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1999;13:1149-1159.

35. Lembo T, Wright RA, Bagby B, et al. Lotronex Investigator Team. Alosetron controls bowel urgency and provides global symptom improvement in women with diarrhea-predom-inant irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:2662-2670.

36. Akehurst R, Kaltenthaler E. Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a review of randomized control trials. Gut 2001;48:272-282.

37. Jackson JL, O’Malley PG, Tomkins G, Balden E, Santoro J, Kroeneke K. Treatment of functional gastrointestinal disorders with antidepressant medications: a metaanalysis. Am J Med 2000;108:65-72.

38. Myren J, Lovland B, Larssen SE, Larsen S. A double-blind study of the effect of trimipramine in patients with the irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol 1984;19:835-843.

39. Greenbaum DS, Mayle JE, Vanegeren LE, et al. Effects of desipramine on irritable bowel syndrome compared with atropine and placebo. Dig Dis Sci 1987;32:257-266.

40. Cann PA, Read NW, Holdsworth CD, Barends D. Role of loperamide and placebo in management of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Dig Dis Sci 1984;29:239-247.

41. Hovdenak N. Loperamide treatment of the irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl 1987;130:81-84.

42. Efskind PS, Bernklev T, Vatn MH. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial with loperamide in irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol 1996;31:463-468.

43. Ritchie JA, Truelove SC. Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with lorazepam, hyoscine butylbromide, and ispaghula husk. Br Med J 1979;1:376-378.

44. Parisi GC, Zilli M, Miani MP, E, et al. High-fiber diet supplementation in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. A multi-center, randomized, open trial comparison between wheat bran diet and partially hydrolyzed guar gum. Dig Dis Sci 2002;47:1697-1704.

45. Golechha AC, Chadda VS, Chadda S, Sharma SK, Mishra SN. Role of ispaghula husk in the management of irritable bowel syndrome (A randomized double-blind crossover study). JAPI 1982;30:353-354.

46. Arthurs Y, Fielding JF. Double blind trial of ispaghula/poloxamer in the irritable bowel syndrome. BMJ 1983;76:253.-

47. Jalihal A, Kurian G. Ispaghula therapy in irritable bowel syndrome: Improvement in overall well being is related to reduction in bowel dissatisfaction. J Gastroenterol Hep 1990;5:507-513.

48. Spanier JA, Howden CW, Jones MP. A systematic review of alternative therapies in irritable bowel syndrome. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:265-274.

49. Pittler MH, Ernst E. Peppermint Oil for irritable bowel syndrome: A critical review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 1998;93:1131-1135.

50. Creed F, Fernandes L, Guthrie E, et al. The cost-effectiveness of psychotherapy and paroxetine for severe irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2003;124:303-317.

51. Kuiken SD, Tytgat GNJ, Boeckxstaens GEE. The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluoxetine does not change rectal sensitivity and symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: A double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003;1:219-228.

52. Heymann-Monnikes I, Arnold R, Florin I, et al. The combination of medical treatment plus multicomponent behavioral therapy is superior to medical treatment alone in the therapy of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:981-994.

53. Talley NJ, Owen BK, Boyce P, Paterson K. Psychological treatments for irritable bowel syndrome: A critique of controlled treatment trials. Am J Gastroenterol 1996;91:277-286.

54. Svedlund J, Sjodin I, Ottoson JO, Dotevall G. Controlled study of psychotherapy in irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet 1983;2:589-592.

55. Greene B, Blanchard EB. Cognitive therapy for irritable bowel syndrome. J Consulting Clinic Psychology 1994;62:576-582.

56. Guthrie E, Creed F, Dawson D, Tomenson B. A ramdomized controlled trial of psychotherapy in patients with refractory irritable bowel syndrome. B J Psychiatry 1993;163:315-321.

57. Heymann-Monnikes I, Arnold R, Florin I, Herda C, Melfsen S, Monnikes H. The combination of medical treatment plus multicomponent behavioral therapy is superior to medical treatment alone in the therapy of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:981-994.

- For patients aged <50 years without alarm symptoms, diagnostic testing is unnecessary. Consider celiac sprue testing for patients with diarrhea (C).

- Treatment is indicated when both the patient with irritable bowel syndrome and the physician agree that quality of life has been diminished (C). The goal of therapy is to alleviate global IBS symptoms (abdominal discomfort, bloating, and altered bowel habits that are life-impacting) (C).

- Tegaserod, a 5HT4 receptor agonist, is more effective than placebo at relieving global IBS symptoms in women with constipation (A). Its effectiveness in men is unknown.

- Alosetron, a 5HT3 receptor antagonist, is more effective than placebo at relieving global IBS symptoms in women with diarrhea (A).

- Behavior therapy–relaxation therapy, hypnotherapy, or cognitive therapy–is more effective than placebo at relieving individual symptoms, but no data are available for quality-of-life improvement (B).

An extensive and expensive evaluation for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) can be avoided if your patient is aged <50 years and is not experiencing alarm symptoms (hematochezia, 10 lbs weight loss, fever, anemia, nocturnal or severe diarrhea), has not recently taken antibiotics, and has no family history of colon cancer. An algorithm ( Figure ) indicates when work-up is needed and what it should entail.

Newer medications that act on 5HT receptors have proven effective in improving quality of life (global symptom reduction). Evidence supports the use of several traditional medications to reduce individual symptoms of IBS, but not for global symptom reduction.

FIGURE

Evaluating possible irritable bowel syndrome

Who gets irritable bowel syndrome?

Ten percent to 15% of the North American population has IBS, and twice as many women as men have it.1 Symptoms usually begin before the age of 35 years, and many patients can trace their symptoms back to childhood.2 Onset in the elderly is rare.3 The disorder is responsible for approximately 50% of referrals to gastroenterologists.4

The company IBS keeps

Comorbid psychiatric illness is common with IBS, but few patients seek psychiatric care.5 Depression, anxiety, and somatoform disorders are seen in 94% of patients with IBS. IBS is common in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome (51%), fibromyalgia (49%), temporomandibular joint syndrome (64%), and chronic pelvic pain (50%).6 IBS often follows stressful life events,5,7,8 such as a death in the family or divorce. It tends to be chronic, intermittent, and relapsing.3

The symptoms of IBS can overlap with those of other illnesses, including thyroid dysfunction (diarrhea or constipation), functional dyspepsia (abdominal pain), Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis (diarrhea, abdominal pain), celiac sprue (diarrhea), polyps and cancers (constipation or abdominal pain), and infectious diarrhea.

Elusive physiologic mechanism

Several physiologic mechanisms have been proposed for IBS symptoms: altered gut reactivity in response to luminal stimuli, hypersensitive gut with enhanced pain response, and altered brain-gut biochemical axis.9 Though the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome appear to have a physiologic basis, there are no structural or biochemical markers for the disease.

Use symptom-based criteria for diagnosis

Consider a diagnosis of IBS when a patient complains of abdominal discomfort and altered bowel habits. In the absence of a structural or biochemical marker, IBS must be diagnosed according to symptom-based criteria–such as Manning, Rome I, or Rome II–which have been developed for research and epidemiologic purposes. Though their clinical utility remains unproven, these criteria (delineated in Table 1 ) are the crux of clinical diagnosis for IBS.4,10-14 Subtypes of IBS have been described (diarrheapredominant IBS or constipation-predominant IBS), but they are not diagnostically useful, since the treatment goal is improved quality of life.

TABLE 1

Symptom-based criteria for irritable bowel syndrome

| Symptom-based criteria | Symptoms | Sn | Sp | PV+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manning4,10,13,14 |

| 42%–90% | 70%–100% | 74% |

| Rome I4,10,13 |

| 65%–84% | 100% | 69%–100% |

| Rome II11-13 |

| 49%-65%* | 100%* | 69%-100%* |

| Supportive symptoms | ||||

| Fewer than 3 bowel movements per week | ||||

| More than 3 bowel movements per day | ||||

| Hard or lumpy stools | ||||

| *Found to have similar sensitivity and specificity to Rome I.14 | ||||

| Sn, sensitivity; Sp, specificity; PV+, positive predictive value | ||||

Dubious value of diagnostic tests

The literature regarding the value of diagnostic testing for IBS is controversial. Symptom-based criteria have varied in many studies, as have the criteria used to enroll patients and the measured outcomes of treatment (reduction in abdominal pain, in diarrhea, or in constipation, or improvement in quality of life). Because of these discrepancies, it is difficult to apply the literature clinically. Of the 6 landmark studies that considered the value of diagnostic testing for IBS patients,15-20 only 2 compared IBS patients with groups of healthy controls.17,19

Test results yield little. Most research in this area has compared the prevalence of specific illnesses in the general population with the yield of positive test results for these illnesses among persons meeting the symptom-based diagnostic criteria for IBS.

Two studies15,16 determined the incidence of abnormal test results in patients who met the Manning or Rome I criteria for IBS. In these studies, most diagnostic tests yielded positive results in 2% (range, 0%-8.2%) of patients or less, except for thyroid and lactose intolerance testing. That is equivalent to the incidence in the general population. The prevalence of thyroid disorders and lactose malabsorption was higher in IBS patients (6% and 22%-26%, respectively), but prevalence in the general population is similarly higher (5%-9% and 25%). Based on these results, testing for thyroid disease or lactose malabsorption is indicated only for patients exhibiting symptoms of these disorders (fatigue/weight change or diarrhea related to diertary intake of dairy products, respectively).

An exception. Some clinicians propose that diagnostic testing for patients with IBS symptoms should be driven by the pretest probability of organic disease (prevalence) compared with the general population. Cash21 found the pretest probability of inflammatory bowel disease, colorectal cancer, and infectious diarrhea is less than 1% among IBS patients without alarm symptoms ( Table 2 ). He demonstrated that patients with IBS had a 5% pretest probability of celiac sprue compared with healthy patients (<1% prevalence). Therefore, testing for celiac sprue (eg, complete blood count, antiendomysial antibody, and antigliadin antibody) may be considered for patients with diarrhea.6,21,22 Sigmoidoscopy,15,17 rectal biopsy,17 and abdominal ultrasound18 have low positive yield in patients meeting the diagnostic criteria for IBS.

TABLE 2

Probability of organic disease in irritable bowel syndrome patients

| Disease | Pretest probability-IBS patients (%) | Prevalence-general population (%) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colitis/inflammatory inflammatory bowel disease | 0.51-0.98 | 0.3-1.2 | Structural colon lesions were detected with barium enema, colonscopy, sigmoidoscopy |

| Colon cancer | 0-0.51 | 4-6 | Structural colon lesions were detected with barium enema, colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy |

| Celiac disease | 4.67 | 0.25-0.5 | Note: celiac disease prevalence higher than in general population. |

| Gastrointestinal infection | 0-1.7 | N/A | |

| Thyroid dysfunction | 6 | 5-9 | Prevalence high in both groups |

| Lactose malabsorption | 22-26 | 25 | Prevalence high in both groups |

| Adapted from: Cash BD, Schonfeld P, Chey WD. The utility of diagnostic tests in irritable bowel syndrome patients: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97:2812-2819. | |||

| Results are from multiple studies: n=125-306. | |||

How to proceed

Those under 50 years of age who have no alarm symptoms can forgo further testing. Testing for celiac sprue and lactose malabsorption might be considered for patients with diarrhea that improves or worsens with change in diet (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C).

Threshold for treatment

Treatment for IBS is indicated when both patient and physician believe global symptoms (abdominal discomfort, bloating, altered bowel habits) have diminished the quality of life (SOR: C). The goal of treatment is to alleviate all IBS symptoms (SOR: C). Treating altered bowel habits (constipation, diarrhea, and fecal urgency) without addressing other IBS symptoms (eg, abdominal pain) is inferior treatment.23,24

Treatment options for IBS

Treatments for IBS include medications, behavior therapy, and complimentary and alternative therapies. Medications traditionally prescribed include bulking agents, anticholinergics/antispasmodics, antidiarrheals, and antidepressants. A 5HT3 receptor antagonist and a 5HT4 receptor partial agonist are now available. Table 3 summarizes the traditional treatments in terms of efficacy, strength of recommendations, and outcomes measured. Alternative and complimentary therapies appear in Table 4 .

As Brandt24 has noted, the evidence for treatment effectiveness is difficult to review and summarize, because the quality of studies has been poor. Most studies did not use healthy control groups, and the numbers of participants were small. Many studies did not use blinded placebo groups. Outcomes measured varied among the studies, with most of them measuring reductions of individual bowel symptoms (eg, diarrhea or constipation). Quality-of-life tools were used in other studies to measure reduction in global IBS symptoms (eg, IBS Quality of Life 25 ). Because of these discrepancies, there is no sound evidence for traditional therapies.

TABLE 3

Treatments for irritable bowel syndrome

| Treatment | Efficacy (NNT) | SOR (studies) | Outcomes measured | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5HT4 receptor agonist (tegaserod)23,24,26-30 | More effective than placebo at relieving global IBS symptoms in women with constipation (3.9-17) | A (4) | Global IBS symptoms, individual IBS symptoms | 83%-100% of study participants were women with IBS and constipation. Rome I and II criteria for entry. May cause diarrhea |

| 5HT4 receptor agonist(alosetron)23,24,26- 35 | More effective than placebo at relieving global IBS symptoms in women with diarrhea (2.5-8.3) | A (4) | Global IBS symptoms, individual IBS symptoms, adverse events | 82%-93% of study participants were women. Rome I and II criteria for entry. May cause severe constipation; restricted use |

| Tricylic antidepressants (trimipramine, desipramine)23,24,36- 39 | Reduces abdominal pain. No more effective than placebo at relieving gloal IBS symptoms (3.2-5) | B (6) | GI symptoms | May cause constipation; no studies done with SSRIs |

| Loperamide23,24,36-39 | Relieves diarrhea. No more effective than placebo at relieving global IBS symptoms (3.2-5) | B (3) | Global IBS symptoms, diarrhea | Constipation or paralytic ileus can occur |

| Bulking agents (corn fiber, wheat bran, psyllium, ispaghula husks, calcium polycabophil)23,24,31,40-42 | Improves constipation. No more effective than placebo in studies considering global symptom improvement (2.2-8.6) | B (13) | GI symptoms, global IBS symptoms | May increase bloating. All studiessmall numbers of patients |

| Anti-spasmodics (hyoscyamine dicyclomine)23,24,26-30 | No evidence on improvement of global IBS symptoms (5.9) | B (3) | Individual IBS and global symptoms | Studies were short, small numbers, inconsistent effectiveness. Could worsen constipation; 15 additional studies done on drugs not available in the US |

| Behavioral therapies (hypnotherapy, relaxation therapy, psychotherapy, biofeedback)23,24,44, 52-57 | More effective than placebo at relieving individuals IBS symptoms (1.4-1.9) | B (16) | GI symptoms, psychological sypmtoms | None measures global IBS symptom improvement. Small numbers of patients |

| SSRI antidepressants (paroxtetine, fluoxetine)23,24, 50-51 | Improved quality of life, decreased abdominal pain | B (16) | Abdominal | One study severe IBS, other study only 10 participants quality of life |

| SOR, strength of recommendation; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; GI, gastrointestinal; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. For an explanation of SORs. | ||||

TABLE 4

Complementary and alternative treatments for irritable bowel syndrome

| Treatment | Efficacy | SOR | Outcomes measured | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neomycin 20 | Treatment for 1 week improved symptoms of abdominal pain, diarrhea, and constipation | A | Abdominal pain, diarrhea, or constipation | Studies measuring global symptom improvement lacking |

| Peppermint oil 31,4849 | Some demonstrated improvement in abdominal pain | B | Individual IBS symptoms | Studies measuring global symptom improvement lacking |

| Guar gum 44 | Improved abdominal pain and bowel alterations | B | Study compared fiber to guar gum–equal affect on abdominal pain. Gum was better toleratEd | No placebo-controlled trials |

| Probiotics48 (lactobacillus) | Improvement of abdominal pain and flatulence | C | Abdominal pain, flatulence | Two studies with small numbers |

| Elimination diets 48 | Improvement of diarrhea | C | Diarrhea | Milk, wheat, eggs eliminated; 15%-71% improvement of diarrhea |

| Lactose and fructose avoidance 48 | Conflicting evidence results | D | No controlled studies available | |

| Pancreatic enzymes 48 | No evidence | D | Evidence lacking | |

| Ginger 48 | No evidence | D | No studies |

Medications

Strength of recommendation: A. The recently approved 5HT4 receptor agonist tegaserod (Zelnorm) is more effective than placebo at relieving global symptoms in women with constipation (number needed to treat [NNT]=3.9-17).26-30 Diarrhea can be a serious side effect.

The 5HT3 receptor antagonist alosetron (Lotronex) is more effective than placebo at relieving global IBS symptoms in women with diarrhea (NNT=2.5-8.3).31-35 Severe constipation can be an adverse effect. The prescribing of alosetron is currently restricted to physicians who participate in the manufacturer’s risk management program.

In addition to these serotoninergic agents, others in this class are being developed and undergoing clinical trials. The knowledge being gained about 5HT receptors may revolutionize the care of patients with IBS.

Strength of recommendation: B. Tricyclic antidepressants are no more effective than placebo at relieving global IBS symptoms, but they do decrease abdominal pain (NNT=3.2-5).36-39

Loperamide is no more effective than placebo at relieving IBS global symptoms, but it may be used to treat diarrhea (NNT=2.3-5).31,40-42

Bulking agents (such as calcium polycarbophil or psyllium) are no more effective than placebo at relieving IBS global symptoms, but they may decrease constipation (NNT=2.2-8.6).31,36,43-47

Peppermint oil may be helpful for abdominal pain, but global symptom reduction has not been demonstrated.31,48-49 Only a few studies have looked at the use of antispasmodic agents for IBS. They are of poor quality and used small numbers with no placebo controls.23,31,36,43

Strength of recommendation: C. There are limited studies evaluating the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) fluoxetine and paroxetine. Paroxetine was shown in 1 study to improve quality of life.50 Fluoxetine reduced abdominal pain, but did not improve quality of life.51

Behavioral and complementary/alternative therapies

Relaxation therapy, hypnotherapy, and cognitive therapy are effective at relieving individual IBS symptoms, but have not been shown to reduce global IBS symptoms (SOR: B).52-57 Other alternative therapies (eg, guar gum44 [SOR: B], ginger48 [SOR: B], and pancreatic enzymes48 [SOR: C]) have been studied, but high-quality studies considering global improvement have not been published.

The position statement of the American College of Gastroenterology on the management of IBS23 and Brandt’s systematic review of this subject24 were the starting points for this review. The majority of the references from these sources were reviewed and a Medline search was completed to identify new evidence. The Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine grades of recommendations were applied to this evidence, a care algorithm was created, summary tables were developed, and numbers needed to treat were calculated.

Promote self-awareness

Quality-of-life assessment should be done routinely in the care of IBS patients. Provide support, empathy, and basic behavior modification tools. Educate patients and their families on the theoretical biochemical basis of this illness, and help them connect symptoms with stressors, to facilitate lifestyle modification.

Correspondence

Keith B. Holten, MD, Clinton Memorial Hospital/University of Cincinnati Family Practice Residency, 825 W. Locust St., Wilmington, OH, 45177. E-mail: [email protected].

- For patients aged <50 years without alarm symptoms, diagnostic testing is unnecessary. Consider celiac sprue testing for patients with diarrhea (C).

- Treatment is indicated when both the patient with irritable bowel syndrome and the physician agree that quality of life has been diminished (C). The goal of therapy is to alleviate global IBS symptoms (abdominal discomfort, bloating, and altered bowel habits that are life-impacting) (C).

- Tegaserod, a 5HT4 receptor agonist, is more effective than placebo at relieving global IBS symptoms in women with constipation (A). Its effectiveness in men is unknown.

- Alosetron, a 5HT3 receptor antagonist, is more effective than placebo at relieving global IBS symptoms in women with diarrhea (A).

- Behavior therapy–relaxation therapy, hypnotherapy, or cognitive therapy–is more effective than placebo at relieving individual symptoms, but no data are available for quality-of-life improvement (B).

An extensive and expensive evaluation for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) can be avoided if your patient is aged <50 years and is not experiencing alarm symptoms (hematochezia, 10 lbs weight loss, fever, anemia, nocturnal or severe diarrhea), has not recently taken antibiotics, and has no family history of colon cancer. An algorithm ( Figure ) indicates when work-up is needed and what it should entail.

Newer medications that act on 5HT receptors have proven effective in improving quality of life (global symptom reduction). Evidence supports the use of several traditional medications to reduce individual symptoms of IBS, but not for global symptom reduction.

FIGURE

Evaluating possible irritable bowel syndrome

Who gets irritable bowel syndrome?

Ten percent to 15% of the North American population has IBS, and twice as many women as men have it.1 Symptoms usually begin before the age of 35 years, and many patients can trace their symptoms back to childhood.2 Onset in the elderly is rare.3 The disorder is responsible for approximately 50% of referrals to gastroenterologists.4

The company IBS keeps

Comorbid psychiatric illness is common with IBS, but few patients seek psychiatric care.5 Depression, anxiety, and somatoform disorders are seen in 94% of patients with IBS. IBS is common in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome (51%), fibromyalgia (49%), temporomandibular joint syndrome (64%), and chronic pelvic pain (50%).6 IBS often follows stressful life events,5,7,8 such as a death in the family or divorce. It tends to be chronic, intermittent, and relapsing.3

The symptoms of IBS can overlap with those of other illnesses, including thyroid dysfunction (diarrhea or constipation), functional dyspepsia (abdominal pain), Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis (diarrhea, abdominal pain), celiac sprue (diarrhea), polyps and cancers (constipation or abdominal pain), and infectious diarrhea.

Elusive physiologic mechanism

Several physiologic mechanisms have been proposed for IBS symptoms: altered gut reactivity in response to luminal stimuli, hypersensitive gut with enhanced pain response, and altered brain-gut biochemical axis.9 Though the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome appear to have a physiologic basis, there are no structural or biochemical markers for the disease.

Use symptom-based criteria for diagnosis

Consider a diagnosis of IBS when a patient complains of abdominal discomfort and altered bowel habits. In the absence of a structural or biochemical marker, IBS must be diagnosed according to symptom-based criteria–such as Manning, Rome I, or Rome II–which have been developed for research and epidemiologic purposes. Though their clinical utility remains unproven, these criteria (delineated in Table 1 ) are the crux of clinical diagnosis for IBS.4,10-14 Subtypes of IBS have been described (diarrheapredominant IBS or constipation-predominant IBS), but they are not diagnostically useful, since the treatment goal is improved quality of life.

TABLE 1

Symptom-based criteria for irritable bowel syndrome

| Symptom-based criteria | Symptoms | Sn | Sp | PV+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manning4,10,13,14 |

| 42%–90% | 70%–100% | 74% |

| Rome I4,10,13 |

| 65%–84% | 100% | 69%–100% |

| Rome II11-13 |

| 49%-65%* | 100%* | 69%-100%* |

| Supportive symptoms | ||||

| Fewer than 3 bowel movements per week | ||||

| More than 3 bowel movements per day | ||||

| Hard or lumpy stools | ||||

| *Found to have similar sensitivity and specificity to Rome I.14 | ||||

| Sn, sensitivity; Sp, specificity; PV+, positive predictive value | ||||

Dubious value of diagnostic tests

The literature regarding the value of diagnostic testing for IBS is controversial. Symptom-based criteria have varied in many studies, as have the criteria used to enroll patients and the measured outcomes of treatment (reduction in abdominal pain, in diarrhea, or in constipation, or improvement in quality of life). Because of these discrepancies, it is difficult to apply the literature clinically. Of the 6 landmark studies that considered the value of diagnostic testing for IBS patients,15-20 only 2 compared IBS patients with groups of healthy controls.17,19

Test results yield little. Most research in this area has compared the prevalence of specific illnesses in the general population with the yield of positive test results for these illnesses among persons meeting the symptom-based diagnostic criteria for IBS.

Two studies15,16 determined the incidence of abnormal test results in patients who met the Manning or Rome I criteria for IBS. In these studies, most diagnostic tests yielded positive results in 2% (range, 0%-8.2%) of patients or less, except for thyroid and lactose intolerance testing. That is equivalent to the incidence in the general population. The prevalence of thyroid disorders and lactose malabsorption was higher in IBS patients (6% and 22%-26%, respectively), but prevalence in the general population is similarly higher (5%-9% and 25%). Based on these results, testing for thyroid disease or lactose malabsorption is indicated only for patients exhibiting symptoms of these disorders (fatigue/weight change or diarrhea related to diertary intake of dairy products, respectively).

An exception. Some clinicians propose that diagnostic testing for patients with IBS symptoms should be driven by the pretest probability of organic disease (prevalence) compared with the general population. Cash21 found the pretest probability of inflammatory bowel disease, colorectal cancer, and infectious diarrhea is less than 1% among IBS patients without alarm symptoms ( Table 2 ). He demonstrated that patients with IBS had a 5% pretest probability of celiac sprue compared with healthy patients (<1% prevalence). Therefore, testing for celiac sprue (eg, complete blood count, antiendomysial antibody, and antigliadin antibody) may be considered for patients with diarrhea.6,21,22 Sigmoidoscopy,15,17 rectal biopsy,17 and abdominal ultrasound18 have low positive yield in patients meeting the diagnostic criteria for IBS.

TABLE 2

Probability of organic disease in irritable bowel syndrome patients

| Disease | Pretest probability-IBS patients (%) | Prevalence-general population (%) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colitis/inflammatory inflammatory bowel disease | 0.51-0.98 | 0.3-1.2 | Structural colon lesions were detected with barium enema, colonscopy, sigmoidoscopy |

| Colon cancer | 0-0.51 | 4-6 | Structural colon lesions were detected with barium enema, colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy |

| Celiac disease | 4.67 | 0.25-0.5 | Note: celiac disease prevalence higher than in general population. |

| Gastrointestinal infection | 0-1.7 | N/A | |

| Thyroid dysfunction | 6 | 5-9 | Prevalence high in both groups |

| Lactose malabsorption | 22-26 | 25 | Prevalence high in both groups |

| Adapted from: Cash BD, Schonfeld P, Chey WD. The utility of diagnostic tests in irritable bowel syndrome patients: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97:2812-2819. | |||

| Results are from multiple studies: n=125-306. | |||

How to proceed

Those under 50 years of age who have no alarm symptoms can forgo further testing. Testing for celiac sprue and lactose malabsorption might be considered for patients with diarrhea that improves or worsens with change in diet (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C).

Threshold for treatment

Treatment for IBS is indicated when both patient and physician believe global symptoms (abdominal discomfort, bloating, altered bowel habits) have diminished the quality of life (SOR: C). The goal of treatment is to alleviate all IBS symptoms (SOR: C). Treating altered bowel habits (constipation, diarrhea, and fecal urgency) without addressing other IBS symptoms (eg, abdominal pain) is inferior treatment.23,24

Treatment options for IBS

Treatments for IBS include medications, behavior therapy, and complimentary and alternative therapies. Medications traditionally prescribed include bulking agents, anticholinergics/antispasmodics, antidiarrheals, and antidepressants. A 5HT3 receptor antagonist and a 5HT4 receptor partial agonist are now available. Table 3 summarizes the traditional treatments in terms of efficacy, strength of recommendations, and outcomes measured. Alternative and complimentary therapies appear in Table 4 .

As Brandt24 has noted, the evidence for treatment effectiveness is difficult to review and summarize, because the quality of studies has been poor. Most studies did not use healthy control groups, and the numbers of participants were small. Many studies did not use blinded placebo groups. Outcomes measured varied among the studies, with most of them measuring reductions of individual bowel symptoms (eg, diarrhea or constipation). Quality-of-life tools were used in other studies to measure reduction in global IBS symptoms (eg, IBS Quality of Life 25 ). Because of these discrepancies, there is no sound evidence for traditional therapies.

TABLE 3

Treatments for irritable bowel syndrome

| Treatment | Efficacy (NNT) | SOR (studies) | Outcomes measured | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5HT4 receptor agonist (tegaserod)23,24,26-30 | More effective than placebo at relieving global IBS symptoms in women with constipation (3.9-17) | A (4) | Global IBS symptoms, individual IBS symptoms | 83%-100% of study participants were women with IBS and constipation. Rome I and II criteria for entry. May cause diarrhea |

| 5HT4 receptor agonist(alosetron)23,24,26- 35 | More effective than placebo at relieving global IBS symptoms in women with diarrhea (2.5-8.3) | A (4) | Global IBS symptoms, individual IBS symptoms, adverse events | 82%-93% of study participants were women. Rome I and II criteria for entry. May cause severe constipation; restricted use |

| Tricylic antidepressants (trimipramine, desipramine)23,24,36- 39 | Reduces abdominal pain. No more effective than placebo at relieving gloal IBS symptoms (3.2-5) | B (6) | GI symptoms | May cause constipation; no studies done with SSRIs |

| Loperamide23,24,36-39 | Relieves diarrhea. No more effective than placebo at relieving global IBS symptoms (3.2-5) | B (3) | Global IBS symptoms, diarrhea | Constipation or paralytic ileus can occur |

| Bulking agents (corn fiber, wheat bran, psyllium, ispaghula husks, calcium polycabophil)23,24,31,40-42 | Improves constipation. No more effective than placebo in studies considering global symptom improvement (2.2-8.6) | B (13) | GI symptoms, global IBS symptoms | May increase bloating. All studiessmall numbers of patients |

| Anti-spasmodics (hyoscyamine dicyclomine)23,24,26-30 | No evidence on improvement of global IBS symptoms (5.9) | B (3) | Individual IBS and global symptoms | Studies were short, small numbers, inconsistent effectiveness. Could worsen constipation; 15 additional studies done on drugs not available in the US |

| Behavioral therapies (hypnotherapy, relaxation therapy, psychotherapy, biofeedback)23,24,44, 52-57 | More effective than placebo at relieving individuals IBS symptoms (1.4-1.9) | B (16) | GI symptoms, psychological sypmtoms | None measures global IBS symptom improvement. Small numbers of patients |

| SSRI antidepressants (paroxtetine, fluoxetine)23,24, 50-51 | Improved quality of life, decreased abdominal pain | B (16) | Abdominal | One study severe IBS, other study only 10 participants quality of life |

| SOR, strength of recommendation; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; GI, gastrointestinal; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. For an explanation of SORs. | ||||

TABLE 4

Complementary and alternative treatments for irritable bowel syndrome

| Treatment | Efficacy | SOR | Outcomes measured | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neomycin 20 | Treatment for 1 week improved symptoms of abdominal pain, diarrhea, and constipation | A | Abdominal pain, diarrhea, or constipation | Studies measuring global symptom improvement lacking |

| Peppermint oil 31,4849 | Some demonstrated improvement in abdominal pain | B | Individual IBS symptoms | Studies measuring global symptom improvement lacking |

| Guar gum 44 | Improved abdominal pain and bowel alterations | B | Study compared fiber to guar gum–equal affect on abdominal pain. Gum was better toleratEd | No placebo-controlled trials |

| Probiotics48 (lactobacillus) | Improvement of abdominal pain and flatulence | C | Abdominal pain, flatulence | Two studies with small numbers |

| Elimination diets 48 | Improvement of diarrhea | C | Diarrhea | Milk, wheat, eggs eliminated; 15%-71% improvement of diarrhea |

| Lactose and fructose avoidance 48 | Conflicting evidence results | D | No controlled studies available | |

| Pancreatic enzymes 48 | No evidence | D | Evidence lacking | |

| Ginger 48 | No evidence | D | No studies |

Medications

Strength of recommendation: A. The recently approved 5HT4 receptor agonist tegaserod (Zelnorm) is more effective than placebo at relieving global symptoms in women with constipation (number needed to treat [NNT]=3.9-17).26-30 Diarrhea can be a serious side effect.

The 5HT3 receptor antagonist alosetron (Lotronex) is more effective than placebo at relieving global IBS symptoms in women with diarrhea (NNT=2.5-8.3).31-35 Severe constipation can be an adverse effect. The prescribing of alosetron is currently restricted to physicians who participate in the manufacturer’s risk management program.

In addition to these serotoninergic agents, others in this class are being developed and undergoing clinical trials. The knowledge being gained about 5HT receptors may revolutionize the care of patients with IBS.

Strength of recommendation: B. Tricyclic antidepressants are no more effective than placebo at relieving global IBS symptoms, but they do decrease abdominal pain (NNT=3.2-5).36-39

Loperamide is no more effective than placebo at relieving IBS global symptoms, but it may be used to treat diarrhea (NNT=2.3-5).31,40-42

Bulking agents (such as calcium polycarbophil or psyllium) are no more effective than placebo at relieving IBS global symptoms, but they may decrease constipation (NNT=2.2-8.6).31,36,43-47

Peppermint oil may be helpful for abdominal pain, but global symptom reduction has not been demonstrated.31,48-49 Only a few studies have looked at the use of antispasmodic agents for IBS. They are of poor quality and used small numbers with no placebo controls.23,31,36,43

Strength of recommendation: C. There are limited studies evaluating the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) fluoxetine and paroxetine. Paroxetine was shown in 1 study to improve quality of life.50 Fluoxetine reduced abdominal pain, but did not improve quality of life.51

Behavioral and complementary/alternative therapies

Relaxation therapy, hypnotherapy, and cognitive therapy are effective at relieving individual IBS symptoms, but have not been shown to reduce global IBS symptoms (SOR: B).52-57 Other alternative therapies (eg, guar gum44 [SOR: B], ginger48 [SOR: B], and pancreatic enzymes48 [SOR: C]) have been studied, but high-quality studies considering global improvement have not been published.

The position statement of the American College of Gastroenterology on the management of IBS23 and Brandt’s systematic review of this subject24 were the starting points for this review. The majority of the references from these sources were reviewed and a Medline search was completed to identify new evidence. The Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine grades of recommendations were applied to this evidence, a care algorithm was created, summary tables were developed, and numbers needed to treat were calculated.

Promote self-awareness

Quality-of-life assessment should be done routinely in the care of IBS patients. Provide support, empathy, and basic behavior modification tools. Educate patients and their families on the theoretical biochemical basis of this illness, and help them connect symptoms with stressors, to facilitate lifestyle modification.

Correspondence

Keith B. Holten, MD, Clinton Memorial Hospital/University of Cincinnati Family Practice Residency, 825 W. Locust St., Wilmington, OH, 45177. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Saito YA, Schoenfeld P, Locke R. The epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome in North America: A systematic review. Am J Gastrenterol 2002;97:1910-1915.

2. Talley NJ, Gabriel SE, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Evans RW. Medical costs in community subjects with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 1995;109:1736-1741.

3. Maxwell PR, Mendall MA, Kumar D. Irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet 1997;350:1691-1695.

4. Fass R, Longstreth GF, Pimental M, et al. Evidence- and consensus-based practice guidelines for the diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:2081-2088.

5. Goldberg J, Davidson P. A biopsychosocial understanding of the irritable bowel syndrome: a review. Can J Psychiatry 1997;42:835-840.

6. Whitehead WE, Palsson O, Jones KR. Systematic review of the comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome with other disorders: What are the causes and implications? Gastroenterology 2002;122:1140-1156.

7. Olden KW, Drossman DA. Psychologic and psychiatric aspects of gastrointestinal disease. Med Clin North Am 2000;84:1313-1327.

8. Aaron LA, Burke MM, Buchwald D. Overlapping conditions among patients with chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, and temporomandibular disorder. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:221-227.

9. Camilleri M, Prather CM. The irritable bowel syndrome: mechanisms and a practical approach to management. Ann Internal Med 1992;116:1001-1008.

10. Paterson WG, Thompson WG, Vanner SJ, et al. Recommendations for the management of irritable bowel syndrome in family practice. JAMC 1999;161:154-160.

11. Olden KW. Diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2002;122:1701-1714.

12. Tosetti C, Stanghellini V, Corinaldesi R. The Rome II criteria for patients with functional gastroduodenal disorders. J Clin Gastroenterol 2003;37:92-93.

13. Chey WD, Olden K, Carter E, Boyle J, Drossman D, Chang L. Utility of the Rome I and Rome II criteria for irritable bowel syndrome in US women. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:2803-2811.

14. Vanner SJ, Depew WT, Paterson WG, et al. Predictive value of the Rome criteria for diagnosing the irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:2912-2917.

15. Hamm LR, Sorrells SC, Harding JP, et al. Additional investigations fail to alter the diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome in subjects fulfilling the Rome criteria. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:1279-1282.

16. Tolliver BA, Herrara JL, DiPalma JA. Evaluation of patients who meet clinical criteria for irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 1994;89:176-178.

17. MacIntosh DG, Thompson WG, Patel DP, Barr R, Guindi M. Is rectal biopsy necessary in irritable bowel syndrome? Am J Gastroenterol 1992;87:1407-1409.

18. Francis CY, Duffy JN, Whorwell PJ, Martin DF. Does routine ultrasound enhance diagnostic accuracy in irritable bowel syndrome? Am J Gastroenterol 1996;91:1348-1350.

19. Sanders DS, Carter MJ, Hurlstone DP, et al. Association of adult celiac disease with irritable bowel syndrome: a case-control study in patients fulfilling Rome II criteria referred to secondary care. Lancet 2001;358:1504-1508.

20. Pimental M, Chow EJ, Lin HC. Normalization of lactulose breath testing correlates with symptom improvement in irritable bowel syndrome; a double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:412-419.

21. Cash BD, Schonfeld P, Chey WD. The utility of diagnostic tests in irritable bowel syndrome patients: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:2812-2819.

22. O’Leary CO, Wieneke P, Buckley S, et al. Celiac disease and irritable bowel-type symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:1463-1467.

23. American College of Gastroenterology Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders Task Force. Evidence-based position statement on the management of irritable bowel syndrome in North America. Am J Gastrenterol 2002;97:s1-s5.

24. Brandt LJ, Bjorkman D, Fennerty MB, Locke GR, Olden K, et al. Systematic review on the management of irritable bowel syndrome in north America. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:s7-s26.

25. Drossman DA, Patrick DL, Whitehead WE, NE, et al. Further validation of the IBS-QOL: a disease-specific quality-of-life questionnaire. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:999-1007.

26. Jones BW, Moore DJ, Robinson SM, Song F. A systematic review of tegaserod for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Pharm Therapeutics 2002;27:343-352.

27. Novick J, Miner P, Krause R, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of tegaserod in female patients suffering from irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002;16:1877-1888.

28. Muller-Lissner SA, Fumagalli I, Bardhan KD, et al. Tegaserod, a 5-HT(4) receptor partial agonist, relieves symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome patients with abdominal pain, bloating and constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001;15:1655-1666.

29. Kellow J, Lee OY, Chang FY, et al. An Asia-Pacific, double blind, placebo controlled, randomised study to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of tegaserod in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 2003;52:671-676.

30. Jones RH, Holtmann G, Rodrigo L, Ehsanullah, Crompton PM, Jacques LA, Mills JG. Alosetron relieves pain and improves bowel function compared with mebeverine in female nonconstipated irritable bowel syndrome patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1999;13:1419-1427.

31. Jailwala J, Imperiale TF, Kroeneke K. Pharmacologic treatment of the irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. Ann Intern Med 2000;133:136-147.

32. Cremonini F, Delgado-Aros S, Camilleri M. Efficacy of alosetron in irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2002;15:79-86.

33. Camilleri M, Northcutt AR, Kong S, Dukes GE, McSorley D, Mangel AW. Efficacy and safety of alosetron in women with irritable bowel syndrome: a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2000;355:1035-1040.

34. Camilleri M, Mayer EA, Drossman DA, et al. Improvement in pain and bowel function in female irritable bowel patients with alosetron, a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1999;13:1149-1159.

35. Lembo T, Wright RA, Bagby B, et al. Lotronex Investigator Team. Alosetron controls bowel urgency and provides global symptom improvement in women with diarrhea-predom-inant irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:2662-2670.

36. Akehurst R, Kaltenthaler E. Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a review of randomized control trials. Gut 2001;48:272-282.

37. Jackson JL, O’Malley PG, Tomkins G, Balden E, Santoro J, Kroeneke K. Treatment of functional gastrointestinal disorders with antidepressant medications: a metaanalysis. Am J Med 2000;108:65-72.

38. Myren J, Lovland B, Larssen SE, Larsen S. A double-blind study of the effect of trimipramine in patients with the irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol 1984;19:835-843.

39. Greenbaum DS, Mayle JE, Vanegeren LE, et al. Effects of desipramine on irritable bowel syndrome compared with atropine and placebo. Dig Dis Sci 1987;32:257-266.

40. Cann PA, Read NW, Holdsworth CD, Barends D. Role of loperamide and placebo in management of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Dig Dis Sci 1984;29:239-247.

41. Hovdenak N. Loperamide treatment of the irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl 1987;130:81-84.

42. Efskind PS, Bernklev T, Vatn MH. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial with loperamide in irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol 1996;31:463-468.

43. Ritchie JA, Truelove SC. Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with lorazepam, hyoscine butylbromide, and ispaghula husk. Br Med J 1979;1:376-378.

44. Parisi GC, Zilli M, Miani MP, E, et al. High-fiber diet supplementation in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. A multi-center, randomized, open trial comparison between wheat bran diet and partially hydrolyzed guar gum. Dig Dis Sci 2002;47:1697-1704.

45. Golechha AC, Chadda VS, Chadda S, Sharma SK, Mishra SN. Role of ispaghula husk in the management of irritable bowel syndrome (A randomized double-blind crossover study). JAPI 1982;30:353-354.

46. Arthurs Y, Fielding JF. Double blind trial of ispaghula/poloxamer in the irritable bowel syndrome. BMJ 1983;76:253.-

47. Jalihal A, Kurian G. Ispaghula therapy in irritable bowel syndrome: Improvement in overall well being is related to reduction in bowel dissatisfaction. J Gastroenterol Hep 1990;5:507-513.

48. Spanier JA, Howden CW, Jones MP. A systematic review of alternative therapies in irritable bowel syndrome. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:265-274.

49. Pittler MH, Ernst E. Peppermint Oil for irritable bowel syndrome: A critical review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 1998;93:1131-1135.

50. Creed F, Fernandes L, Guthrie E, et al. The cost-effectiveness of psychotherapy and paroxetine for severe irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2003;124:303-317.

51. Kuiken SD, Tytgat GNJ, Boeckxstaens GEE. The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluoxetine does not change rectal sensitivity and symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: A double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003;1:219-228.

52. Heymann-Monnikes I, Arnold R, Florin I, et al. The combination of medical treatment plus multicomponent behavioral therapy is superior to medical treatment alone in the therapy of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:981-994.

53. Talley NJ, Owen BK, Boyce P, Paterson K. Psychological treatments for irritable bowel syndrome: A critique of controlled treatment trials. Am J Gastroenterol 1996;91:277-286.

54. Svedlund J, Sjodin I, Ottoson JO, Dotevall G. Controlled study of psychotherapy in irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet 1983;2:589-592.

55. Greene B, Blanchard EB. Cognitive therapy for irritable bowel syndrome. J Consulting Clinic Psychology 1994;62:576-582.

56. Guthrie E, Creed F, Dawson D, Tomenson B. A ramdomized controlled trial of psychotherapy in patients with refractory irritable bowel syndrome. B J Psychiatry 1993;163:315-321.

57. Heymann-Monnikes I, Arnold R, Florin I, Herda C, Melfsen S, Monnikes H. The combination of medical treatment plus multicomponent behavioral therapy is superior to medical treatment alone in the therapy of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:981-994.

1. Saito YA, Schoenfeld P, Locke R. The epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome in North America: A systematic review. Am J Gastrenterol 2002;97:1910-1915.

2. Talley NJ, Gabriel SE, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Evans RW. Medical costs in community subjects with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 1995;109:1736-1741.

3. Maxwell PR, Mendall MA, Kumar D. Irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet 1997;350:1691-1695.

4. Fass R, Longstreth GF, Pimental M, et al. Evidence- and consensus-based practice guidelines for the diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:2081-2088.

5. Goldberg J, Davidson P. A biopsychosocial understanding of the irritable bowel syndrome: a review. Can J Psychiatry 1997;42:835-840.

6. Whitehead WE, Palsson O, Jones KR. Systematic review of the comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome with other disorders: What are the causes and implications? Gastroenterology 2002;122:1140-1156.

7. Olden KW, Drossman DA. Psychologic and psychiatric aspects of gastrointestinal disease. Med Clin North Am 2000;84:1313-1327.

8. Aaron LA, Burke MM, Buchwald D. Overlapping conditions among patients with chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, and temporomandibular disorder. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:221-227.

9. Camilleri M, Prather CM. The irritable bowel syndrome: mechanisms and a practical approach to management. Ann Internal Med 1992;116:1001-1008.

10. Paterson WG, Thompson WG, Vanner SJ, et al. Recommendations for the management of irritable bowel syndrome in family practice. JAMC 1999;161:154-160.

11. Olden KW. Diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2002;122:1701-1714.

12. Tosetti C, Stanghellini V, Corinaldesi R. The Rome II criteria for patients with functional gastroduodenal disorders. J Clin Gastroenterol 2003;37:92-93.

13. Chey WD, Olden K, Carter E, Boyle J, Drossman D, Chang L. Utility of the Rome I and Rome II criteria for irritable bowel syndrome in US women. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:2803-2811.

14. Vanner SJ, Depew WT, Paterson WG, et al. Predictive value of the Rome criteria for diagnosing the irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:2912-2917.

15. Hamm LR, Sorrells SC, Harding JP, et al. Additional investigations fail to alter the diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome in subjects fulfilling the Rome criteria. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:1279-1282.

16. Tolliver BA, Herrara JL, DiPalma JA. Evaluation of patients who meet clinical criteria for irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 1994;89:176-178.

17. MacIntosh DG, Thompson WG, Patel DP, Barr R, Guindi M. Is rectal biopsy necessary in irritable bowel syndrome? Am J Gastroenterol 1992;87:1407-1409.

18. Francis CY, Duffy JN, Whorwell PJ, Martin DF. Does routine ultrasound enhance diagnostic accuracy in irritable bowel syndrome? Am J Gastroenterol 1996;91:1348-1350.

19. Sanders DS, Carter MJ, Hurlstone DP, et al. Association of adult celiac disease with irritable bowel syndrome: a case-control study in patients fulfilling Rome II criteria referred to secondary care. Lancet 2001;358:1504-1508.

20. Pimental M, Chow EJ, Lin HC. Normalization of lactulose breath testing correlates with symptom improvement in irritable bowel syndrome; a double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:412-419.

21. Cash BD, Schonfeld P, Chey WD. The utility of diagnostic tests in irritable bowel syndrome patients: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:2812-2819.

22. O’Leary CO, Wieneke P, Buckley S, et al. Celiac disease and irritable bowel-type symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:1463-1467.

23. American College of Gastroenterology Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders Task Force. Evidence-based position statement on the management of irritable bowel syndrome in North America. Am J Gastrenterol 2002;97:s1-s5.

24. Brandt LJ, Bjorkman D, Fennerty MB, Locke GR, Olden K, et al. Systematic review on the management of irritable bowel syndrome in north America. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:s7-s26.

25. Drossman DA, Patrick DL, Whitehead WE, NE, et al. Further validation of the IBS-QOL: a disease-specific quality-of-life questionnaire. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:999-1007.

26. Jones BW, Moore DJ, Robinson SM, Song F. A systematic review of tegaserod for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Pharm Therapeutics 2002;27:343-352.

27. Novick J, Miner P, Krause R, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of tegaserod in female patients suffering from irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002;16:1877-1888.

28. Muller-Lissner SA, Fumagalli I, Bardhan KD, et al. Tegaserod, a 5-HT(4) receptor partial agonist, relieves symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome patients with abdominal pain, bloating and constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001;15:1655-1666.

29. Kellow J, Lee OY, Chang FY, et al. An Asia-Pacific, double blind, placebo controlled, randomised study to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of tegaserod in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 2003;52:671-676.

30. Jones RH, Holtmann G, Rodrigo L, Ehsanullah, Crompton PM, Jacques LA, Mills JG. Alosetron relieves pain and improves bowel function compared with mebeverine in female nonconstipated irritable bowel syndrome patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1999;13:1419-1427.

31. Jailwala J, Imperiale TF, Kroeneke K. Pharmacologic treatment of the irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. Ann Intern Med 2000;133:136-147.

32. Cremonini F, Delgado-Aros S, Camilleri M. Efficacy of alosetron in irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2002;15:79-86.