User login

Managing ADHD in children: Are you doing enough?

• Side effects of psychostimulants can often be managed with monitoring, dose adjustment, a switch to another drug, or adjunctive therapy. A

• Weigh and measure a child being treated for ADHD twice a year; aberrant growth may indicate a need for a change in medication regimen. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Untreated attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) can have serious academic, social, and psychological consequences, both for young patients and their parents. Diagnosis is based on criteria detailed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders, Fourth Edition Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR), with observations of the child’s behavior obtained from more than one setting.

Physicians should also consider the possibility of coexisting conditions, which could complicate diagnosis and subsequent attempts to treat the signs and symptoms of ADHD. Treatment is multifaceted, and will vary depending on severity, comorbidities, and the degree of compliance with nonpharmacologic modalities.

A comprehensive approach is called for

Managing pediatric ADHD in a primary care setting requires a comprehensive, goal-oriented treatment plan. The primary goal, as noted in the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP)’s ADHD guideline,1 is to maximize the child’s functioning, both in terms of an improvement in relationships and academic performance and a reduction of disruptive behavior. Parents and children should be integrated into community supports and school resources, the guideline recommends1 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A).

Additional recommendations focus on patient (and parental) education, and on medication, monitoring, and follow-up (SOR: A). Physicians should:

Educate parents and patients about common ADHD symptoms and treatment strategies.

Initiate pharmacotherapy. Select an agent that is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for ADHD. These include the psychostimulants dextroamphetamine, D- and DL-methylphenidate, and mixed salts amphetamine; and atomoxetine, a noradrenergic reuptake inhibitor. (Central nervous system stimulants should be avoided in children with cardiac abnormalities, who are at increased risk of experiencing sympathomimetic effects.)

Familiarize themselves with medication side effects. Decreased appetite, insomnia, headache, abdominal pain, and irritable mood are the most common side effects of psychostimulants. Common side effects of atomoxetine include somnolence, anorexia, nausea, skin rash, and a mild increase in blood pressure or heart rate. Notably, there is a small risk of suicide associated with atomoxetine.

Monitor patients for the emergence and severity of side effects. Many of the side effects of stimulants are transient and can be managed through monitoring, as long as it does not compromise the patient’s health or interfere with daily living. Side effects can also be managed with dose adjustment, change of drug treatment, or adjunctive therapy.

Measure height and weight of the patient twice yearly. If a child’s height or weight crosses 2 percentiles on his or her growth curve, it may be an indication of aberrant growth—and a drug holiday or switching to a different medication should be considered.

Evaluate treatment success several times a year. The review should include behavior, academic progress, emergence of comorbid disorders, and the need for behavioral therapy and continuing pharmacotherapy. A lack of response to one psychostimulant is not predictive of the patient’s response to another, the AACAP emphasizes, and it is important to keep trying to find another medication until treatment goals are reached.1

If none of the FDA-approved ADHD medications has the desired results, the AACAP recommends (SOR: B):

- a referral to a cognitive behavioral therapist or child psychologist

- a trial with a medication that is not FDA-approved for ADHD, such as bupropion, a tricyclic antidepressant, or an alpha-agonist

- a reevaluation of the ADHD diagnosis, adherence to the treatment plan, and the presence of comorbid conditions.1

AAP stresses hands-on behavioral intervention

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) also has a clinical practice guideline for the treatment of ADHD, issued in 2001.2 Its recommendations are similar to those of the AACAP. But AAP puts additional emphasis on parental training in behavioral therapy and classroom behavioral interventions, and considers both to be more effective than cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).2

Virtual reality: A viable option?

Although conventional treatment of childhood ADHD has had considerable clinical success, other forms of treatment may be needed in some cases—if a child’s parents reject psychopharmacologic treatment, for example, or medication trials and traditional behavioral therapies, such as CBT, fail to bring the desired results.

Virtual reality (VR), a computer-generated 3-dimensional interactive system, is an emerging clinical tool. VR programs such as The Virtual Classroom3,4—in which a child is “immersed” in a simulated classroom setting—have shown promise for ADHD assessment and treatment.

Perhaps the biggest benefit of VR as an ADHD intervention is the opportunity for a clinician to place a patient in a virtual classroom, with tasks that require the child’s attention as well as distractors, such as conversation, ambient noise, and moving objects. Another advantage is the ability to integrate traditional assessment tools (Continuous Performance Tasks, for example) and treatment modalities, such as CBT.5 This can be accomplished through a graphic display of a child’s performance during a VR session, which the therapist can use as part of the therapeutic process.3 And VR has no side effects.

Several facilities are either using or experimenting with VR for ADHD. More information is available from the Virtual Reality Medical Center at http://www.vrphobia.com/adhd.htm.

CORRESPONDENCE

Keith B. Holten, MD, Berger Health System, 600 North Pickaway Street, Circleville, OH 43113; [email protected]

1. Pliszka S. AACAP Work Group on Quality Issues. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:894-921.

2. American Academy of Pediatrics. Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Clinical practice guideline: treatment of the school-aged child with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2001;108:1033-1044.

3. Rizzo AA, Buckwalter JG, Humphrey L, et al. The virtual classroom: a virtual environment for the assessment and rehabilitation of attention deficits. CyberPsych Behav. 2000;3:483-499.

4. Rizzo AA, Klimchuk D, Mitura R, et al. A virtual reality scenario for all seasons: the virtual classroom. CNS Spectr. 2006;11:35-44.

5. Pollak Y, Weiss PL, Rizzo AA, et al. The utility of a continuous performance test embedded in virtual reality in measuring ADHD-related deficits. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2009;30:2-6.

• Side effects of psychostimulants can often be managed with monitoring, dose adjustment, a switch to another drug, or adjunctive therapy. A

• Weigh and measure a child being treated for ADHD twice a year; aberrant growth may indicate a need for a change in medication regimen. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Untreated attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) can have serious academic, social, and psychological consequences, both for young patients and their parents. Diagnosis is based on criteria detailed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders, Fourth Edition Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR), with observations of the child’s behavior obtained from more than one setting.

Physicians should also consider the possibility of coexisting conditions, which could complicate diagnosis and subsequent attempts to treat the signs and symptoms of ADHD. Treatment is multifaceted, and will vary depending on severity, comorbidities, and the degree of compliance with nonpharmacologic modalities.

A comprehensive approach is called for

Managing pediatric ADHD in a primary care setting requires a comprehensive, goal-oriented treatment plan. The primary goal, as noted in the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP)’s ADHD guideline,1 is to maximize the child’s functioning, both in terms of an improvement in relationships and academic performance and a reduction of disruptive behavior. Parents and children should be integrated into community supports and school resources, the guideline recommends1 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A).

Additional recommendations focus on patient (and parental) education, and on medication, monitoring, and follow-up (SOR: A). Physicians should:

Educate parents and patients about common ADHD symptoms and treatment strategies.

Initiate pharmacotherapy. Select an agent that is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for ADHD. These include the psychostimulants dextroamphetamine, D- and DL-methylphenidate, and mixed salts amphetamine; and atomoxetine, a noradrenergic reuptake inhibitor. (Central nervous system stimulants should be avoided in children with cardiac abnormalities, who are at increased risk of experiencing sympathomimetic effects.)

Familiarize themselves with medication side effects. Decreased appetite, insomnia, headache, abdominal pain, and irritable mood are the most common side effects of psychostimulants. Common side effects of atomoxetine include somnolence, anorexia, nausea, skin rash, and a mild increase in blood pressure or heart rate. Notably, there is a small risk of suicide associated with atomoxetine.

Monitor patients for the emergence and severity of side effects. Many of the side effects of stimulants are transient and can be managed through monitoring, as long as it does not compromise the patient’s health or interfere with daily living. Side effects can also be managed with dose adjustment, change of drug treatment, or adjunctive therapy.

Measure height and weight of the patient twice yearly. If a child’s height or weight crosses 2 percentiles on his or her growth curve, it may be an indication of aberrant growth—and a drug holiday or switching to a different medication should be considered.

Evaluate treatment success several times a year. The review should include behavior, academic progress, emergence of comorbid disorders, and the need for behavioral therapy and continuing pharmacotherapy. A lack of response to one psychostimulant is not predictive of the patient’s response to another, the AACAP emphasizes, and it is important to keep trying to find another medication until treatment goals are reached.1

If none of the FDA-approved ADHD medications has the desired results, the AACAP recommends (SOR: B):

- a referral to a cognitive behavioral therapist or child psychologist

- a trial with a medication that is not FDA-approved for ADHD, such as bupropion, a tricyclic antidepressant, or an alpha-agonist

- a reevaluation of the ADHD diagnosis, adherence to the treatment plan, and the presence of comorbid conditions.1

AAP stresses hands-on behavioral intervention

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) also has a clinical practice guideline for the treatment of ADHD, issued in 2001.2 Its recommendations are similar to those of the AACAP. But AAP puts additional emphasis on parental training in behavioral therapy and classroom behavioral interventions, and considers both to be more effective than cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).2

Virtual reality: A viable option?

Although conventional treatment of childhood ADHD has had considerable clinical success, other forms of treatment may be needed in some cases—if a child’s parents reject psychopharmacologic treatment, for example, or medication trials and traditional behavioral therapies, such as CBT, fail to bring the desired results.

Virtual reality (VR), a computer-generated 3-dimensional interactive system, is an emerging clinical tool. VR programs such as The Virtual Classroom3,4—in which a child is “immersed” in a simulated classroom setting—have shown promise for ADHD assessment and treatment.

Perhaps the biggest benefit of VR as an ADHD intervention is the opportunity for a clinician to place a patient in a virtual classroom, with tasks that require the child’s attention as well as distractors, such as conversation, ambient noise, and moving objects. Another advantage is the ability to integrate traditional assessment tools (Continuous Performance Tasks, for example) and treatment modalities, such as CBT.5 This can be accomplished through a graphic display of a child’s performance during a VR session, which the therapist can use as part of the therapeutic process.3 And VR has no side effects.

Several facilities are either using or experimenting with VR for ADHD. More information is available from the Virtual Reality Medical Center at http://www.vrphobia.com/adhd.htm.

CORRESPONDENCE

Keith B. Holten, MD, Berger Health System, 600 North Pickaway Street, Circleville, OH 43113; [email protected]

• Side effects of psychostimulants can often be managed with monitoring, dose adjustment, a switch to another drug, or adjunctive therapy. A

• Weigh and measure a child being treated for ADHD twice a year; aberrant growth may indicate a need for a change in medication regimen. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Untreated attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) can have serious academic, social, and psychological consequences, both for young patients and their parents. Diagnosis is based on criteria detailed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders, Fourth Edition Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR), with observations of the child’s behavior obtained from more than one setting.

Physicians should also consider the possibility of coexisting conditions, which could complicate diagnosis and subsequent attempts to treat the signs and symptoms of ADHD. Treatment is multifaceted, and will vary depending on severity, comorbidities, and the degree of compliance with nonpharmacologic modalities.

A comprehensive approach is called for

Managing pediatric ADHD in a primary care setting requires a comprehensive, goal-oriented treatment plan. The primary goal, as noted in the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP)’s ADHD guideline,1 is to maximize the child’s functioning, both in terms of an improvement in relationships and academic performance and a reduction of disruptive behavior. Parents and children should be integrated into community supports and school resources, the guideline recommends1 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A).

Additional recommendations focus on patient (and parental) education, and on medication, monitoring, and follow-up (SOR: A). Physicians should:

Educate parents and patients about common ADHD symptoms and treatment strategies.

Initiate pharmacotherapy. Select an agent that is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for ADHD. These include the psychostimulants dextroamphetamine, D- and DL-methylphenidate, and mixed salts amphetamine; and atomoxetine, a noradrenergic reuptake inhibitor. (Central nervous system stimulants should be avoided in children with cardiac abnormalities, who are at increased risk of experiencing sympathomimetic effects.)

Familiarize themselves with medication side effects. Decreased appetite, insomnia, headache, abdominal pain, and irritable mood are the most common side effects of psychostimulants. Common side effects of atomoxetine include somnolence, anorexia, nausea, skin rash, and a mild increase in blood pressure or heart rate. Notably, there is a small risk of suicide associated with atomoxetine.

Monitor patients for the emergence and severity of side effects. Many of the side effects of stimulants are transient and can be managed through monitoring, as long as it does not compromise the patient’s health or interfere with daily living. Side effects can also be managed with dose adjustment, change of drug treatment, or adjunctive therapy.

Measure height and weight of the patient twice yearly. If a child’s height or weight crosses 2 percentiles on his or her growth curve, it may be an indication of aberrant growth—and a drug holiday or switching to a different medication should be considered.

Evaluate treatment success several times a year. The review should include behavior, academic progress, emergence of comorbid disorders, and the need for behavioral therapy and continuing pharmacotherapy. A lack of response to one psychostimulant is not predictive of the patient’s response to another, the AACAP emphasizes, and it is important to keep trying to find another medication until treatment goals are reached.1

If none of the FDA-approved ADHD medications has the desired results, the AACAP recommends (SOR: B):

- a referral to a cognitive behavioral therapist or child psychologist

- a trial with a medication that is not FDA-approved for ADHD, such as bupropion, a tricyclic antidepressant, or an alpha-agonist

- a reevaluation of the ADHD diagnosis, adherence to the treatment plan, and the presence of comorbid conditions.1

AAP stresses hands-on behavioral intervention

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) also has a clinical practice guideline for the treatment of ADHD, issued in 2001.2 Its recommendations are similar to those of the AACAP. But AAP puts additional emphasis on parental training in behavioral therapy and classroom behavioral interventions, and considers both to be more effective than cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).2

Virtual reality: A viable option?

Although conventional treatment of childhood ADHD has had considerable clinical success, other forms of treatment may be needed in some cases—if a child’s parents reject psychopharmacologic treatment, for example, or medication trials and traditional behavioral therapies, such as CBT, fail to bring the desired results.

Virtual reality (VR), a computer-generated 3-dimensional interactive system, is an emerging clinical tool. VR programs such as The Virtual Classroom3,4—in which a child is “immersed” in a simulated classroom setting—have shown promise for ADHD assessment and treatment.

Perhaps the biggest benefit of VR as an ADHD intervention is the opportunity for a clinician to place a patient in a virtual classroom, with tasks that require the child’s attention as well as distractors, such as conversation, ambient noise, and moving objects. Another advantage is the ability to integrate traditional assessment tools (Continuous Performance Tasks, for example) and treatment modalities, such as CBT.5 This can be accomplished through a graphic display of a child’s performance during a VR session, which the therapist can use as part of the therapeutic process.3 And VR has no side effects.

Several facilities are either using or experimenting with VR for ADHD. More information is available from the Virtual Reality Medical Center at http://www.vrphobia.com/adhd.htm.

CORRESPONDENCE

Keith B. Holten, MD, Berger Health System, 600 North Pickaway Street, Circleville, OH 43113; [email protected]

1. Pliszka S. AACAP Work Group on Quality Issues. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:894-921.

2. American Academy of Pediatrics. Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Clinical practice guideline: treatment of the school-aged child with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2001;108:1033-1044.

3. Rizzo AA, Buckwalter JG, Humphrey L, et al. The virtual classroom: a virtual environment for the assessment and rehabilitation of attention deficits. CyberPsych Behav. 2000;3:483-499.

4. Rizzo AA, Klimchuk D, Mitura R, et al. A virtual reality scenario for all seasons: the virtual classroom. CNS Spectr. 2006;11:35-44.

5. Pollak Y, Weiss PL, Rizzo AA, et al. The utility of a continuous performance test embedded in virtual reality in measuring ADHD-related deficits. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2009;30:2-6.

1. Pliszka S. AACAP Work Group on Quality Issues. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:894-921.

2. American Academy of Pediatrics. Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Clinical practice guideline: treatment of the school-aged child with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2001;108:1033-1044.

3. Rizzo AA, Buckwalter JG, Humphrey L, et al. The virtual classroom: a virtual environment for the assessment and rehabilitation of attention deficits. CyberPsych Behav. 2000;3:483-499.

4. Rizzo AA, Klimchuk D, Mitura R, et al. A virtual reality scenario for all seasons: the virtual classroom. CNS Spectr. 2006;11:35-44.

5. Pollak Y, Weiss PL, Rizzo AA, et al. The utility of a continuous performance test embedded in virtual reality in measuring ADHD-related deficits. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2009;30:2-6.

What’s the best approach to managing chronic pain?

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

This article is adapted from the December 2008 installment of The Journal of Family Practice’s “Guideline Update” series. The Journal of Family Practice is an NLM-indexed publication of Quadrant HealthCom Inc., publisher of OBG Management.

- What are the critical steps in the assessment of a patient who suffers chronic pain?

- What are the four biologic mechanisms of pain?

- When is referral to a pain specialist recommended?

Answers to these questions are summarized below, and in the 2008 edition of Assessment and Management of Chronic Pain, a practice guideline developed and first published in 2005 by the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI), which also funded the work. ICSI is a collaboration of 57 medical groups sponsored by six Minnesota health plans. A third edition of the guideline, released in August 2008, summarizes current evidence about the assessment and treatment of chronic pain in mature adolescents (16 to 18 years old) and adults.

A distinct challenge to clinicians

Chronic pain—a persistent, life-altering condition—is one of the most challenging disorders for primary care physicians to treat. Unlike the case with acute pain, for which we seek to cure the underlying biologic condition, the goal of chronic pain management is to improve function in the face of pain that may never completely resolve.

Achieving that goal, according to the new guideline, requires a patient-centered, multifaceted approach—often involving a health-care team that includes specialists in behavioral health and physical rehabilitation—that is coordinated by a primary care physician. An effective treatment plan must address biopsychosocial factors as well as spiritual and cultural issues. Patients must be taught self-management skills focused on fitness, stress reduction, and maintaining a healthy lifestyle.

Grade A recommendations

- Develop a physician–patient partnership. This should include a plan of care and realistic goal-setting.

- Begin physical rehabilitation and psychosocial management. This includes an exercise fitness program, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and self-management.

Grade B recommendations

- Obtain a general history, including psychological assessment and spirituality evaluation, and identify barriers to treatment.

- Obtain a thorough pain history.

- Perform a physical examination, including a focused musculoskeletal and neurologic evaluation.

- Perform diagnostic testing as indicated. X-rays, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, electromyography, and nerve conduction studies can help differentiate the biological mechanisms of pain.

- Teach patients to use pain scales for self-reporting.

Grade C recommendations

- Categorize the 4 biological mechanisms of pain (inflammatory, mechanical, musculoskeletal, or neuropathic).

- Consider the following pharmacologic options for Level-I care:

- Consider the following Level-I therapeutic procedures:

- Consider the following Level-II interventions:

Medications may be part of the treatment plan but should not be the sole focus, according to the guideline. Opioids are an option when other therapies fail.

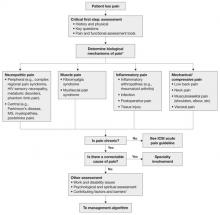

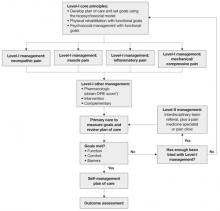

The updated ICSI guideline also addresses the effects of various therapies, the role of psychosocial factors, and the identification of barriers to treatment. The comprehensive guideline, which has 172 references and nine appendices, also features two easy-to-use algorithms. One addresses the assessment of chronic pain ( FIGURE 1 ) and the other deals with chronic pain management ( FIGURE 2 ).

Both algorithms identify Level-I and Level-II strategies that can be readily adapted to primary care practice. They are extremely helpful to physicians who are evaluating and developing a care plan for a patient who has chronic pain.

FIGURE 1 Chronic pain assessment

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; ICSI, Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement; MS, multiple sclerosis.

*Pain types and contributing factors are not mutually exclusive. Patients frequently have more than one type of pain, as well as overlapping contributing factors.

Source: Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Reprinted with permission.

4 objectives

This latest guideline was developed to:

- improve the treatment of adult chronic-pain patients by encouraging physicians to complete an appropriate biopsychosocial assessment (and reassessment)

- improve patients’ function by recommending development and use of a comprehensive treatment plan that includes a multispecialty team

- improve the use of Level-I and Level-II treatment approaches to chronic pain

- provide guidance on the most effective use of nonopioid and opioid medications in the treatment of chronic pain.

With these objectives in mind, the ICSI work group conducted a comprehensive literature review, giving priority to randomized controlled trials (RCTs), meta-analyses, and systematic reviews. The work group used a seven-tier grading system to rate the evidence and a three-category system for the worksheets in the guideline appendices.

For this article, we converted evidence ratings in the guideline into so-called strength-of-recommendation taxonomy, or SORT.1

What aspects of practice have changed?

In addition to reflecting the latest research, the new guideline contains a number of clarifications. For example: The update states that medications are not the “sole” focus of treatment and should be used, when necessary, as part of an overall approach to pain management. (The previous version noted that medications were not the “primary” focus.)

The management algorithm ( FIGURE 2 ) now leads with “core principles”—a term suggesting greater importance than the former term, “general management,” implied. Clinical highlights, a synthesis of key recommendations, have been revised to better align with the guideline’s main components—assessment, functional goals, patient-centered/biopsychosocial care planning, Level-I versus Level-II approaches, and medication and patient selection.

Other changes in the guideline may contribute to clinicians’ understanding of chronic pain and its complex presentation. The guideline now includes a statement about allodynia and hyperalgesia to indicate that both may play an important role in any pain syndrome—not just in complex regional pain syndrome. Information about fibromyalgia symptoms and myofascial pain has been added. The definitions page now has an entry for “biopsychosocial model,” as well as language designed to stress the differences between untreated acute pain and ongoing chronic pain.

FIGURE 2 Chronic pain management

* DIRE, diagnosis, intractability, risk, efficacy.

Source: Institute for Clinical System Improvement. Reprinted with permission.

A limitation, an improvement

A limitation of the guideline is the lack of studies addressing the effectiveness of a comprehensive, multidisciplinary treatment approach to chronic pain management; most studies consider single-therapy management. An improvement, on the other hand, is that the evidence levels for each strategy are now listed within the section describing it—a notable change that makes it easier to identify the quality of individual recommendations.

As has been the case in the past, this latest edition of the guideline offers a number of tools for physicians. The assessment and management algorithms walk clinicians through decision-making. In addition, the following nine appendices provide practical guidance to physicians in various aspects of patient evaluation and care:

- Brief Pain Inventory (Short Form)

- Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)

- Functional Ability Questionnaire

- Personal Care Plan for Chronic Pain

- DIRE (diagnosis, intractability, risk, efficacy) Score: Patient Selection for Chronic Opioid Analgesia

- Opioid Agreement Form

- Opioid Analgesics

- Pharmaceutical Interventions for Neuropathic Pain

- Neuropathic Pain Treatment Diagram.

As noted, the source document for this guideline is: Assessment and Management of Chronic Pain. 3rd ed. Bloomington (Minn): Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI); 2008 July.

The complete guideline is available at: pain__chronic__assessment_and_management_of__guideline_.html " target="_blank"> http://www.icsi.org/pain__chronic__assessment_and_management_of_14399/

pain__chronic__assessment_and_management_of__guideline_.html . (Accessed August 18, 2009.)

Reference

1. Ebell M, Siwek J, Weiss BD, et al. Strength of recommendation taxonomy (SORT): a patient-centered approach to grading evidence in the medical literature. J Fam Pract. 2004;53:111-120.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

This article is adapted from the December 2008 installment of The Journal of Family Practice’s “Guideline Update” series. The Journal of Family Practice is an NLM-indexed publication of Quadrant HealthCom Inc., publisher of OBG Management.

- What are the critical steps in the assessment of a patient who suffers chronic pain?

- What are the four biologic mechanisms of pain?

- When is referral to a pain specialist recommended?

Answers to these questions are summarized below, and in the 2008 edition of Assessment and Management of Chronic Pain, a practice guideline developed and first published in 2005 by the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI), which also funded the work. ICSI is a collaboration of 57 medical groups sponsored by six Minnesota health plans. A third edition of the guideline, released in August 2008, summarizes current evidence about the assessment and treatment of chronic pain in mature adolescents (16 to 18 years old) and adults.

A distinct challenge to clinicians

Chronic pain—a persistent, life-altering condition—is one of the most challenging disorders for primary care physicians to treat. Unlike the case with acute pain, for which we seek to cure the underlying biologic condition, the goal of chronic pain management is to improve function in the face of pain that may never completely resolve.

Achieving that goal, according to the new guideline, requires a patient-centered, multifaceted approach—often involving a health-care team that includes specialists in behavioral health and physical rehabilitation—that is coordinated by a primary care physician. An effective treatment plan must address biopsychosocial factors as well as spiritual and cultural issues. Patients must be taught self-management skills focused on fitness, stress reduction, and maintaining a healthy lifestyle.

Grade A recommendations

- Develop a physician–patient partnership. This should include a plan of care and realistic goal-setting.

- Begin physical rehabilitation and psychosocial management. This includes an exercise fitness program, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and self-management.

Grade B recommendations

- Obtain a general history, including psychological assessment and spirituality evaluation, and identify barriers to treatment.

- Obtain a thorough pain history.

- Perform a physical examination, including a focused musculoskeletal and neurologic evaluation.

- Perform diagnostic testing as indicated. X-rays, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, electromyography, and nerve conduction studies can help differentiate the biological mechanisms of pain.

- Teach patients to use pain scales for self-reporting.

Grade C recommendations

- Categorize the 4 biological mechanisms of pain (inflammatory, mechanical, musculoskeletal, or neuropathic).

- Consider the following pharmacologic options for Level-I care:

- Consider the following Level-I therapeutic procedures:

- Consider the following Level-II interventions:

Medications may be part of the treatment plan but should not be the sole focus, according to the guideline. Opioids are an option when other therapies fail.

The updated ICSI guideline also addresses the effects of various therapies, the role of psychosocial factors, and the identification of barriers to treatment. The comprehensive guideline, which has 172 references and nine appendices, also features two easy-to-use algorithms. One addresses the assessment of chronic pain ( FIGURE 1 ) and the other deals with chronic pain management ( FIGURE 2 ).

Both algorithms identify Level-I and Level-II strategies that can be readily adapted to primary care practice. They are extremely helpful to physicians who are evaluating and developing a care plan for a patient who has chronic pain.

FIGURE 1 Chronic pain assessment

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; ICSI, Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement; MS, multiple sclerosis.

*Pain types and contributing factors are not mutually exclusive. Patients frequently have more than one type of pain, as well as overlapping contributing factors.

Source: Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Reprinted with permission.

4 objectives

This latest guideline was developed to:

- improve the treatment of adult chronic-pain patients by encouraging physicians to complete an appropriate biopsychosocial assessment (and reassessment)

- improve patients’ function by recommending development and use of a comprehensive treatment plan that includes a multispecialty team

- improve the use of Level-I and Level-II treatment approaches to chronic pain

- provide guidance on the most effective use of nonopioid and opioid medications in the treatment of chronic pain.

With these objectives in mind, the ICSI work group conducted a comprehensive literature review, giving priority to randomized controlled trials (RCTs), meta-analyses, and systematic reviews. The work group used a seven-tier grading system to rate the evidence and a three-category system for the worksheets in the guideline appendices.

For this article, we converted evidence ratings in the guideline into so-called strength-of-recommendation taxonomy, or SORT.1

What aspects of practice have changed?

In addition to reflecting the latest research, the new guideline contains a number of clarifications. For example: The update states that medications are not the “sole” focus of treatment and should be used, when necessary, as part of an overall approach to pain management. (The previous version noted that medications were not the “primary” focus.)

The management algorithm ( FIGURE 2 ) now leads with “core principles”—a term suggesting greater importance than the former term, “general management,” implied. Clinical highlights, a synthesis of key recommendations, have been revised to better align with the guideline’s main components—assessment, functional goals, patient-centered/biopsychosocial care planning, Level-I versus Level-II approaches, and medication and patient selection.

Other changes in the guideline may contribute to clinicians’ understanding of chronic pain and its complex presentation. The guideline now includes a statement about allodynia and hyperalgesia to indicate that both may play an important role in any pain syndrome—not just in complex regional pain syndrome. Information about fibromyalgia symptoms and myofascial pain has been added. The definitions page now has an entry for “biopsychosocial model,” as well as language designed to stress the differences between untreated acute pain and ongoing chronic pain.

FIGURE 2 Chronic pain management

* DIRE, diagnosis, intractability, risk, efficacy.

Source: Institute for Clinical System Improvement. Reprinted with permission.

A limitation, an improvement

A limitation of the guideline is the lack of studies addressing the effectiveness of a comprehensive, multidisciplinary treatment approach to chronic pain management; most studies consider single-therapy management. An improvement, on the other hand, is that the evidence levels for each strategy are now listed within the section describing it—a notable change that makes it easier to identify the quality of individual recommendations.

As has been the case in the past, this latest edition of the guideline offers a number of tools for physicians. The assessment and management algorithms walk clinicians through decision-making. In addition, the following nine appendices provide practical guidance to physicians in various aspects of patient evaluation and care:

- Brief Pain Inventory (Short Form)

- Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)

- Functional Ability Questionnaire

- Personal Care Plan for Chronic Pain

- DIRE (diagnosis, intractability, risk, efficacy) Score: Patient Selection for Chronic Opioid Analgesia

- Opioid Agreement Form

- Opioid Analgesics

- Pharmaceutical Interventions for Neuropathic Pain

- Neuropathic Pain Treatment Diagram.

As noted, the source document for this guideline is: Assessment and Management of Chronic Pain. 3rd ed. Bloomington (Minn): Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI); 2008 July.

The complete guideline is available at: pain__chronic__assessment_and_management_of__guideline_.html " target="_blank"> http://www.icsi.org/pain__chronic__assessment_and_management_of_14399/

pain__chronic__assessment_and_management_of__guideline_.html . (Accessed August 18, 2009.)

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

This article is adapted from the December 2008 installment of The Journal of Family Practice’s “Guideline Update” series. The Journal of Family Practice is an NLM-indexed publication of Quadrant HealthCom Inc., publisher of OBG Management.

- What are the critical steps in the assessment of a patient who suffers chronic pain?

- What are the four biologic mechanisms of pain?

- When is referral to a pain specialist recommended?

Answers to these questions are summarized below, and in the 2008 edition of Assessment and Management of Chronic Pain, a practice guideline developed and first published in 2005 by the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI), which also funded the work. ICSI is a collaboration of 57 medical groups sponsored by six Minnesota health plans. A third edition of the guideline, released in August 2008, summarizes current evidence about the assessment and treatment of chronic pain in mature adolescents (16 to 18 years old) and adults.

A distinct challenge to clinicians

Chronic pain—a persistent, life-altering condition—is one of the most challenging disorders for primary care physicians to treat. Unlike the case with acute pain, for which we seek to cure the underlying biologic condition, the goal of chronic pain management is to improve function in the face of pain that may never completely resolve.

Achieving that goal, according to the new guideline, requires a patient-centered, multifaceted approach—often involving a health-care team that includes specialists in behavioral health and physical rehabilitation—that is coordinated by a primary care physician. An effective treatment plan must address biopsychosocial factors as well as spiritual and cultural issues. Patients must be taught self-management skills focused on fitness, stress reduction, and maintaining a healthy lifestyle.

Grade A recommendations

- Develop a physician–patient partnership. This should include a plan of care and realistic goal-setting.

- Begin physical rehabilitation and psychosocial management. This includes an exercise fitness program, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and self-management.

Grade B recommendations

- Obtain a general history, including psychological assessment and spirituality evaluation, and identify barriers to treatment.

- Obtain a thorough pain history.

- Perform a physical examination, including a focused musculoskeletal and neurologic evaluation.

- Perform diagnostic testing as indicated. X-rays, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, electromyography, and nerve conduction studies can help differentiate the biological mechanisms of pain.

- Teach patients to use pain scales for self-reporting.

Grade C recommendations

- Categorize the 4 biological mechanisms of pain (inflammatory, mechanical, musculoskeletal, or neuropathic).

- Consider the following pharmacologic options for Level-I care:

- Consider the following Level-I therapeutic procedures:

- Consider the following Level-II interventions:

Medications may be part of the treatment plan but should not be the sole focus, according to the guideline. Opioids are an option when other therapies fail.

The updated ICSI guideline also addresses the effects of various therapies, the role of psychosocial factors, and the identification of barriers to treatment. The comprehensive guideline, which has 172 references and nine appendices, also features two easy-to-use algorithms. One addresses the assessment of chronic pain ( FIGURE 1 ) and the other deals with chronic pain management ( FIGURE 2 ).

Both algorithms identify Level-I and Level-II strategies that can be readily adapted to primary care practice. They are extremely helpful to physicians who are evaluating and developing a care plan for a patient who has chronic pain.

FIGURE 1 Chronic pain assessment

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; ICSI, Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement; MS, multiple sclerosis.

*Pain types and contributing factors are not mutually exclusive. Patients frequently have more than one type of pain, as well as overlapping contributing factors.

Source: Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Reprinted with permission.

4 objectives

This latest guideline was developed to:

- improve the treatment of adult chronic-pain patients by encouraging physicians to complete an appropriate biopsychosocial assessment (and reassessment)

- improve patients’ function by recommending development and use of a comprehensive treatment plan that includes a multispecialty team

- improve the use of Level-I and Level-II treatment approaches to chronic pain

- provide guidance on the most effective use of nonopioid and opioid medications in the treatment of chronic pain.

With these objectives in mind, the ICSI work group conducted a comprehensive literature review, giving priority to randomized controlled trials (RCTs), meta-analyses, and systematic reviews. The work group used a seven-tier grading system to rate the evidence and a three-category system for the worksheets in the guideline appendices.

For this article, we converted evidence ratings in the guideline into so-called strength-of-recommendation taxonomy, or SORT.1

What aspects of practice have changed?

In addition to reflecting the latest research, the new guideline contains a number of clarifications. For example: The update states that medications are not the “sole” focus of treatment and should be used, when necessary, as part of an overall approach to pain management. (The previous version noted that medications were not the “primary” focus.)

The management algorithm ( FIGURE 2 ) now leads with “core principles”—a term suggesting greater importance than the former term, “general management,” implied. Clinical highlights, a synthesis of key recommendations, have been revised to better align with the guideline’s main components—assessment, functional goals, patient-centered/biopsychosocial care planning, Level-I versus Level-II approaches, and medication and patient selection.

Other changes in the guideline may contribute to clinicians’ understanding of chronic pain and its complex presentation. The guideline now includes a statement about allodynia and hyperalgesia to indicate that both may play an important role in any pain syndrome—not just in complex regional pain syndrome. Information about fibromyalgia symptoms and myofascial pain has been added. The definitions page now has an entry for “biopsychosocial model,” as well as language designed to stress the differences between untreated acute pain and ongoing chronic pain.

FIGURE 2 Chronic pain management

* DIRE, diagnosis, intractability, risk, efficacy.

Source: Institute for Clinical System Improvement. Reprinted with permission.

A limitation, an improvement

A limitation of the guideline is the lack of studies addressing the effectiveness of a comprehensive, multidisciplinary treatment approach to chronic pain management; most studies consider single-therapy management. An improvement, on the other hand, is that the evidence levels for each strategy are now listed within the section describing it—a notable change that makes it easier to identify the quality of individual recommendations.

As has been the case in the past, this latest edition of the guideline offers a number of tools for physicians. The assessment and management algorithms walk clinicians through decision-making. In addition, the following nine appendices provide practical guidance to physicians in various aspects of patient evaluation and care:

- Brief Pain Inventory (Short Form)

- Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)

- Functional Ability Questionnaire

- Personal Care Plan for Chronic Pain

- DIRE (diagnosis, intractability, risk, efficacy) Score: Patient Selection for Chronic Opioid Analgesia

- Opioid Agreement Form

- Opioid Analgesics

- Pharmaceutical Interventions for Neuropathic Pain

- Neuropathic Pain Treatment Diagram.

As noted, the source document for this guideline is: Assessment and Management of Chronic Pain. 3rd ed. Bloomington (Minn): Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI); 2008 July.

The complete guideline is available at: pain__chronic__assessment_and_management_of__guideline_.html " target="_blank"> http://www.icsi.org/pain__chronic__assessment_and_management_of_14399/

pain__chronic__assessment_and_management_of__guideline_.html . (Accessed August 18, 2009.)

Reference

1. Ebell M, Siwek J, Weiss BD, et al. Strength of recommendation taxonomy (SORT): a patient-centered approach to grading evidence in the medical literature. J Fam Pract. 2004;53:111-120.

Reference

1. Ebell M, Siwek J, Weiss BD, et al. Strength of recommendation taxonomy (SORT): a patient-centered approach to grading evidence in the medical literature. J Fam Pract. 2004;53:111-120.

Emergency contraception care

- Does levonorgestrel work better than estrogen-progestin combination in preventing pregnancy?

- Which method is better tolerated, levonorgestrel or estrogen-progestin?

- When should emergency contraception be initiated?

- How often can emergency contraception be used?

This guideline targets women who have had unprotected or inadequately protected intercourse within the past 120 hours and do not desire pregnancy.

Practitioners can make informed decisions about obstetric and gynecologic care, given the evidence in this guideline regarding safety, efficacy, risks and benefits of the use of emergency contraception including progestin-only and combined estrogen-progestin regimen.

The major outcome considered was incidence of unintended pregnancy. The evidence rating is updated to comply with the SORT taxonomy.1

Guideline relevance and limitations

This guideline is extremely relevant in light of the recent decision (August 2006) by the US Food and Drug Administration to allow the Plan B (levonorgestrel) to be sold over the counter to women aged 18 and older.2 It is still available by prescription to women aged <18 years.

Forty-nine percent of pregnancies were unintended in 2001. Of these 3.1 million unintended pregnancies, only 44% ended in births.3 Emergency contraception has an important role in reducing the number of unwanted pregnancies.

Lack of cost analysis weakened this guideline. Emergency contraceptive doses for commonly prescribed oral contraceptives are listed in the TABLE.

TABLE

Emergency contraception dosage for commonly prescribed oral contraceptives

| BRAND NAME | ETHINYL ESTRADIOL PER DOSE (MCG) | LEVONORGESTREL PER DOSE (MG) | FIRST DOSE | SECOND DOSE (12 HOURS LATER) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Progestin only | ||||

| Plan B | 0 | 1.5 | 2 white pills | none |

| Ovrette | 0 | 1.5 | 20 yellow pills | 20 yellow pills |

| Combined progestin/estrogen pills | ||||

| Alesse | 100 | 0.50 | 5 pink pills | 5 pink pills |

| Lo/Ovral | 120 | 0.60 | 4 white pills | 4 white pills |

| Ovral | 100 | 0.50 | 2 white pills | 2 white pills |

| Seasonale | 120 | 0.60 | 4 pink pills | 4 pink pills |

| Triphasil | 120 | 0.50 | 4 yellow pills | 4 yellow pills |

| Source: adapted from Office of Population Research at Princeton University.4 | ||||

Guideline development and evidence review

A search of the literature was performed using Medline, the Cochrane Library, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ own internal resources and documents. Restrictions included articles published in English between January 1985 and January 2005. Priority was given to meta-analyses and systematic reviews, which were analyzed by an expert panel. Recommendations were graded. Abstracts of research presented at conferences and symposiums were not considered adequate to be considered.

Source for this guideline

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Emergency contraception. ACOG practice bulletin no 69. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG); 2005. 10 p. [86 references]

Other guidelines

Emergency Contraception

This 2005 guideline published by the American Academy of Pediatrics is similar to the ACOG Guideline. It is comprehensive, but recommendations are not graded. The focus is on adolescent use of emergency contraception. It has an excellent section on telephone triage of sexually active teens prior to prescribing emergency contraception.

Source. American Academy of Pediatrics. Emergency contraception. Pediatrics 2005 Oct;116(4):1026-35. [101 references] Available at: aappolicy.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/pediatrics;116/4/1026.

GRADE A RECOMMENDATIONS

- Emergency contraception should be made available to women who have had unprotected or inadequately protected sexual intercourse and who do not desire pregnancy.

- The levonorgestrel-only regime is more effective and is associated with less nausea and vomiting. It should be used in preference to the combined estrogen-progestin regimen.

- The 1.5-mg levonorgestrel-only regimen can be taken in a single dose.

- The two 0.75-mg doses of the levonorgestrel-only regimen are equally effective if taken 12 to 24 hours apart.

- To reduce the chance of nausea with the combined estrogen-progestin regimen, an antiemetic agent may be taken 1 hour prior to the first emergency contraception dose.

- Prescription or provision of emergency contraception in advance of need can increase availability and use.

GRADE B RECOMMENDATIONS

- Treatment with emergency contraception should be initialized as soon as possible after unprotected or inadequately protected intercourse to maximize efficacy.

- Emergency contraception should be made available to patients who request it up to 120 hours after unprotected intercourse.

- No clinician examination or pregnancy testing is necessary before provision or prescription of emergency contraception.

GRADE C RECOMMENDATIONS

- No data specifically examined the risk of using hormonal methods of emergency contraception among women with contraindications to the use of conventional oral contraceptive preparations; nevertheless, emergency contraception may be made available to such women.

- Clinical evaluation is indicated for women who have used emergency contraception if menses are delayed by a week or more after the expected time, if lower abdominal pain occurs, or persistent irregular bleeding develops.

- Information regarding effective contraceptive methods should be made available either at the time emergency contraception is prescribed or at some convenient time thereafter.

- Emergency contraception may be used even if the woman has used it before, even within the same menstrual cycle.

Emergency Contraception

This 2003 Scottish guideline is well written, but lacks information about all current options for emergency contraception. It is strengthened by cost-effectiveness analysis.

Source. Faculty of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care Clinical Effectiveness Unit. Emergency contraception. Aberdeen, Scotland: Faculty of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care Clinical Effectiveness Unit; 2003 Jun. 7 p. [53 references] Available at: www.ffprhc.org.uk/admin/uploads/EC%20revised%20PDF%2019.06.03.pdf.

Contraception and Family Planning: A guide to counseling and management

This 2005 guideline was published by Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. In addition to emergency contraception, it provides recommendations on hormonal contraception (oral contraceptive pills, depo-medroxyprogesterone acetate, estrogen-progestin patches, vaginal ring, and levonorgestrel intrauterine), barrier contraception, intrauterine devices, surgical methods for contraception, and pregnancy termination.

Source. New Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Contraception and family planning. A guide to counseling and management. Boston, Mass: Brigham and Women’s Hospital; 2005.15 p. [6 references]. Available at: www.brighamandwomens.org/medical/handbookarticles/ContraceptionGuide.pdf.

CORRESPONDENCE

Keith B. Holten, MD, 825 Locust Street, Wilmington, OH 45177. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Ebell M, Siwek J, Weiss BD, et al. Strength of recommendation taxonomy (SORT): A patient-centered approach to grading evidence in the medical literature. J Fam Pract 2004;53:111-120.

2. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves over-the-counter access for Plan B for women 18 and older-prescription remains required for those 17 and under. FDA News, August 24, 2006. Available at: www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/NEWS/2006/NEW01436.html. Accessed on November 13, 2006.

3. Finn LB, et al. Disparities in unintentional pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001. Perspect Sexual Reprod Health 2006;38:90-96.

4. The Emergency Contraception Website. Office of Population Research at Princeton University and the Association of Reproductive Health Professionals. 2006. Available at: ec.princeton.edu/questions/dose.html. Accessed on November 13, 2006.

- Does levonorgestrel work better than estrogen-progestin combination in preventing pregnancy?

- Which method is better tolerated, levonorgestrel or estrogen-progestin?

- When should emergency contraception be initiated?

- How often can emergency contraception be used?

This guideline targets women who have had unprotected or inadequately protected intercourse within the past 120 hours and do not desire pregnancy.

Practitioners can make informed decisions about obstetric and gynecologic care, given the evidence in this guideline regarding safety, efficacy, risks and benefits of the use of emergency contraception including progestin-only and combined estrogen-progestin regimen.

The major outcome considered was incidence of unintended pregnancy. The evidence rating is updated to comply with the SORT taxonomy.1

Guideline relevance and limitations

This guideline is extremely relevant in light of the recent decision (August 2006) by the US Food and Drug Administration to allow the Plan B (levonorgestrel) to be sold over the counter to women aged 18 and older.2 It is still available by prescription to women aged <18 years.

Forty-nine percent of pregnancies were unintended in 2001. Of these 3.1 million unintended pregnancies, only 44% ended in births.3 Emergency contraception has an important role in reducing the number of unwanted pregnancies.

Lack of cost analysis weakened this guideline. Emergency contraceptive doses for commonly prescribed oral contraceptives are listed in the TABLE.

TABLE

Emergency contraception dosage for commonly prescribed oral contraceptives

| BRAND NAME | ETHINYL ESTRADIOL PER DOSE (MCG) | LEVONORGESTREL PER DOSE (MG) | FIRST DOSE | SECOND DOSE (12 HOURS LATER) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Progestin only | ||||

| Plan B | 0 | 1.5 | 2 white pills | none |

| Ovrette | 0 | 1.5 | 20 yellow pills | 20 yellow pills |

| Combined progestin/estrogen pills | ||||

| Alesse | 100 | 0.50 | 5 pink pills | 5 pink pills |

| Lo/Ovral | 120 | 0.60 | 4 white pills | 4 white pills |

| Ovral | 100 | 0.50 | 2 white pills | 2 white pills |

| Seasonale | 120 | 0.60 | 4 pink pills | 4 pink pills |

| Triphasil | 120 | 0.50 | 4 yellow pills | 4 yellow pills |

| Source: adapted from Office of Population Research at Princeton University.4 | ||||

Guideline development and evidence review

A search of the literature was performed using Medline, the Cochrane Library, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ own internal resources and documents. Restrictions included articles published in English between January 1985 and January 2005. Priority was given to meta-analyses and systematic reviews, which were analyzed by an expert panel. Recommendations were graded. Abstracts of research presented at conferences and symposiums were not considered adequate to be considered.

Source for this guideline

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Emergency contraception. ACOG practice bulletin no 69. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG); 2005. 10 p. [86 references]

Other guidelines

Emergency Contraception

This 2005 guideline published by the American Academy of Pediatrics is similar to the ACOG Guideline. It is comprehensive, but recommendations are not graded. The focus is on adolescent use of emergency contraception. It has an excellent section on telephone triage of sexually active teens prior to prescribing emergency contraception.

Source. American Academy of Pediatrics. Emergency contraception. Pediatrics 2005 Oct;116(4):1026-35. [101 references] Available at: aappolicy.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/pediatrics;116/4/1026.

GRADE A RECOMMENDATIONS

- Emergency contraception should be made available to women who have had unprotected or inadequately protected sexual intercourse and who do not desire pregnancy.

- The levonorgestrel-only regime is more effective and is associated with less nausea and vomiting. It should be used in preference to the combined estrogen-progestin regimen.

- The 1.5-mg levonorgestrel-only regimen can be taken in a single dose.

- The two 0.75-mg doses of the levonorgestrel-only regimen are equally effective if taken 12 to 24 hours apart.

- To reduce the chance of nausea with the combined estrogen-progestin regimen, an antiemetic agent may be taken 1 hour prior to the first emergency contraception dose.

- Prescription or provision of emergency contraception in advance of need can increase availability and use.

GRADE B RECOMMENDATIONS

- Treatment with emergency contraception should be initialized as soon as possible after unprotected or inadequately protected intercourse to maximize efficacy.

- Emergency contraception should be made available to patients who request it up to 120 hours after unprotected intercourse.

- No clinician examination or pregnancy testing is necessary before provision or prescription of emergency contraception.

GRADE C RECOMMENDATIONS

- No data specifically examined the risk of using hormonal methods of emergency contraception among women with contraindications to the use of conventional oral contraceptive preparations; nevertheless, emergency contraception may be made available to such women.

- Clinical evaluation is indicated for women who have used emergency contraception if menses are delayed by a week or more after the expected time, if lower abdominal pain occurs, or persistent irregular bleeding develops.

- Information regarding effective contraceptive methods should be made available either at the time emergency contraception is prescribed or at some convenient time thereafter.

- Emergency contraception may be used even if the woman has used it before, even within the same menstrual cycle.

Emergency Contraception

This 2003 Scottish guideline is well written, but lacks information about all current options for emergency contraception. It is strengthened by cost-effectiveness analysis.

Source. Faculty of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care Clinical Effectiveness Unit. Emergency contraception. Aberdeen, Scotland: Faculty of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care Clinical Effectiveness Unit; 2003 Jun. 7 p. [53 references] Available at: www.ffprhc.org.uk/admin/uploads/EC%20revised%20PDF%2019.06.03.pdf.

Contraception and Family Planning: A guide to counseling and management

This 2005 guideline was published by Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. In addition to emergency contraception, it provides recommendations on hormonal contraception (oral contraceptive pills, depo-medroxyprogesterone acetate, estrogen-progestin patches, vaginal ring, and levonorgestrel intrauterine), barrier contraception, intrauterine devices, surgical methods for contraception, and pregnancy termination.

Source. New Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Contraception and family planning. A guide to counseling and management. Boston, Mass: Brigham and Women’s Hospital; 2005.15 p. [6 references]. Available at: www.brighamandwomens.org/medical/handbookarticles/ContraceptionGuide.pdf.

CORRESPONDENCE

Keith B. Holten, MD, 825 Locust Street, Wilmington, OH 45177. E-mail: [email protected]

- Does levonorgestrel work better than estrogen-progestin combination in preventing pregnancy?

- Which method is better tolerated, levonorgestrel or estrogen-progestin?

- When should emergency contraception be initiated?

- How often can emergency contraception be used?

This guideline targets women who have had unprotected or inadequately protected intercourse within the past 120 hours and do not desire pregnancy.

Practitioners can make informed decisions about obstetric and gynecologic care, given the evidence in this guideline regarding safety, efficacy, risks and benefits of the use of emergency contraception including progestin-only and combined estrogen-progestin regimen.

The major outcome considered was incidence of unintended pregnancy. The evidence rating is updated to comply with the SORT taxonomy.1

Guideline relevance and limitations

This guideline is extremely relevant in light of the recent decision (August 2006) by the US Food and Drug Administration to allow the Plan B (levonorgestrel) to be sold over the counter to women aged 18 and older.2 It is still available by prescription to women aged <18 years.

Forty-nine percent of pregnancies were unintended in 2001. Of these 3.1 million unintended pregnancies, only 44% ended in births.3 Emergency contraception has an important role in reducing the number of unwanted pregnancies.

Lack of cost analysis weakened this guideline. Emergency contraceptive doses for commonly prescribed oral contraceptives are listed in the TABLE.

TABLE

Emergency contraception dosage for commonly prescribed oral contraceptives

| BRAND NAME | ETHINYL ESTRADIOL PER DOSE (MCG) | LEVONORGESTREL PER DOSE (MG) | FIRST DOSE | SECOND DOSE (12 HOURS LATER) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Progestin only | ||||

| Plan B | 0 | 1.5 | 2 white pills | none |

| Ovrette | 0 | 1.5 | 20 yellow pills | 20 yellow pills |

| Combined progestin/estrogen pills | ||||

| Alesse | 100 | 0.50 | 5 pink pills | 5 pink pills |

| Lo/Ovral | 120 | 0.60 | 4 white pills | 4 white pills |

| Ovral | 100 | 0.50 | 2 white pills | 2 white pills |

| Seasonale | 120 | 0.60 | 4 pink pills | 4 pink pills |

| Triphasil | 120 | 0.50 | 4 yellow pills | 4 yellow pills |

| Source: adapted from Office of Population Research at Princeton University.4 | ||||

Guideline development and evidence review

A search of the literature was performed using Medline, the Cochrane Library, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ own internal resources and documents. Restrictions included articles published in English between January 1985 and January 2005. Priority was given to meta-analyses and systematic reviews, which were analyzed by an expert panel. Recommendations were graded. Abstracts of research presented at conferences and symposiums were not considered adequate to be considered.

Source for this guideline

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Emergency contraception. ACOG practice bulletin no 69. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG); 2005. 10 p. [86 references]

Other guidelines

Emergency Contraception

This 2005 guideline published by the American Academy of Pediatrics is similar to the ACOG Guideline. It is comprehensive, but recommendations are not graded. The focus is on adolescent use of emergency contraception. It has an excellent section on telephone triage of sexually active teens prior to prescribing emergency contraception.

Source. American Academy of Pediatrics. Emergency contraception. Pediatrics 2005 Oct;116(4):1026-35. [101 references] Available at: aappolicy.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/pediatrics;116/4/1026.

GRADE A RECOMMENDATIONS

- Emergency contraception should be made available to women who have had unprotected or inadequately protected sexual intercourse and who do not desire pregnancy.

- The levonorgestrel-only regime is more effective and is associated with less nausea and vomiting. It should be used in preference to the combined estrogen-progestin regimen.

- The 1.5-mg levonorgestrel-only regimen can be taken in a single dose.

- The two 0.75-mg doses of the levonorgestrel-only regimen are equally effective if taken 12 to 24 hours apart.

- To reduce the chance of nausea with the combined estrogen-progestin regimen, an antiemetic agent may be taken 1 hour prior to the first emergency contraception dose.

- Prescription or provision of emergency contraception in advance of need can increase availability and use.

GRADE B RECOMMENDATIONS

- Treatment with emergency contraception should be initialized as soon as possible after unprotected or inadequately protected intercourse to maximize efficacy.

- Emergency contraception should be made available to patients who request it up to 120 hours after unprotected intercourse.

- No clinician examination or pregnancy testing is necessary before provision or prescription of emergency contraception.

GRADE C RECOMMENDATIONS

- No data specifically examined the risk of using hormonal methods of emergency contraception among women with contraindications to the use of conventional oral contraceptive preparations; nevertheless, emergency contraception may be made available to such women.

- Clinical evaluation is indicated for women who have used emergency contraception if menses are delayed by a week or more after the expected time, if lower abdominal pain occurs, or persistent irregular bleeding develops.

- Information regarding effective contraceptive methods should be made available either at the time emergency contraception is prescribed or at some convenient time thereafter.

- Emergency contraception may be used even if the woman has used it before, even within the same menstrual cycle.

Emergency Contraception

This 2003 Scottish guideline is well written, but lacks information about all current options for emergency contraception. It is strengthened by cost-effectiveness analysis.

Source. Faculty of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care Clinical Effectiveness Unit. Emergency contraception. Aberdeen, Scotland: Faculty of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care Clinical Effectiveness Unit; 2003 Jun. 7 p. [53 references] Available at: www.ffprhc.org.uk/admin/uploads/EC%20revised%20PDF%2019.06.03.pdf.

Contraception and Family Planning: A guide to counseling and management

This 2005 guideline was published by Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. In addition to emergency contraception, it provides recommendations on hormonal contraception (oral contraceptive pills, depo-medroxyprogesterone acetate, estrogen-progestin patches, vaginal ring, and levonorgestrel intrauterine), barrier contraception, intrauterine devices, surgical methods for contraception, and pregnancy termination.

Source. New Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Contraception and family planning. A guide to counseling and management. Boston, Mass: Brigham and Women’s Hospital; 2005.15 p. [6 references]. Available at: www.brighamandwomens.org/medical/handbookarticles/ContraceptionGuide.pdf.

CORRESPONDENCE

Keith B. Holten, MD, 825 Locust Street, Wilmington, OH 45177. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Ebell M, Siwek J, Weiss BD, et al. Strength of recommendation taxonomy (SORT): A patient-centered approach to grading evidence in the medical literature. J Fam Pract 2004;53:111-120.

2. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves over-the-counter access for Plan B for women 18 and older-prescription remains required for those 17 and under. FDA News, August 24, 2006. Available at: www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/NEWS/2006/NEW01436.html. Accessed on November 13, 2006.

3. Finn LB, et al. Disparities in unintentional pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001. Perspect Sexual Reprod Health 2006;38:90-96.

4. The Emergency Contraception Website. Office of Population Research at Princeton University and the Association of Reproductive Health Professionals. 2006. Available at: ec.princeton.edu/questions/dose.html. Accessed on November 13, 2006.

1. Ebell M, Siwek J, Weiss BD, et al. Strength of recommendation taxonomy (SORT): A patient-centered approach to grading evidence in the medical literature. J Fam Pract 2004;53:111-120.

2. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves over-the-counter access for Plan B for women 18 and older-prescription remains required for those 17 and under. FDA News, August 24, 2006. Available at: www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/NEWS/2006/NEW01436.html. Accessed on November 13, 2006.

3. Finn LB, et al. Disparities in unintentional pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001. Perspect Sexual Reprod Health 2006;38:90-96.

4. The Emergency Contraception Website. Office of Population Research at Princeton University and the Association of Reproductive Health Professionals. 2006. Available at: ec.princeton.edu/questions/dose.html. Accessed on November 13, 2006.

Parkinson’s disease: How practical are new recommendations?

This feature reviews guidelines when they are developed with high-quality evidence and are relevant to primary care physicians. Now and then, however, it is instructive to critique recommendations that fall short of this mark. Four Parkinson’s disease practice parameters recently published by the American Academy of Neurology purport to be explicit, evidence-based, and of high quality; however, we feel these guidelines should be used with caution.

These recommendations for care of the Parkinson’s patient were published in Neurology as 4 separate reviews.1-4 The topics covered include diagnosis and prognosis, treatment of motor fluctuations and dyskinesia, neuroprotective strategies, and evaluation and treatment of depression, psychosis, and dementia. There are 201 references. These recommendations were developed by the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. These guidelines can be accessed on the Web at: www.aan.com/professionals/practice/guideline/index.cfm.

Limitations of these recommendations

In these reviews, terminology regarding effectiveness is not consistently used. Instead of stating that a treatment “is effective,” the authors report that it “should be considered” or “should be offered.”

DIAGNOSIS

- Early falls, poor response to levodopa, symmetry of motor symptoms, and lack of tremor are “probably useful” to suggest other Parkinson-like syndromes, but are not typical for Parkinson’s disease

- Levodopa or apomorphine challenge and olfactory testing are “probably useful” in diagnosing Parkinson’s disease

- Older age at onset, associated comorbidities, rigidity and bradykinesia at onset, and decreased dopamine responsiveness are associated with poorer prognosis

TREATMENT

- Entacapone and rasagiline “should be offered” to reduce off time (periods where medications wear off and Parkinson’s disease symptoms return) (A). Pergolide, pramipexole, ropinirole, and tolcapone “should be considered” (B). Apomorphine, cabergoline, and selegiline “may be considered” (C). Current evidence does not support the use of one medication over another in reducing off time (B). Sustained release carbidopa/levodopa and bromocriptine “may be disregarded” to reduce off time (C)

- Amantadine “may be considered” to reduce dyskinesias (C)

- Deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus “may be considered” for improving motor function and dyskinesias and reducing off time and medication usage (C)

NEUROPROTECTION

- Levodopa “does not appear” to accelerate disease progression

- No treatment is neuroprotective

- No evidence supports vitamin and food additives for improving motor function

- Exercise “may be helpful” for improving motor function

- Speech therapy “may be helpful” for improving speech volume

- Screening and treatment of depression, psychosis, and dementia

- Depression rating scales “should be considered” to screen for depression (B)

- Dementia screening “should be considered” (B)

- Amitriptyline “may be considered” to treat depression without dementia (C)

- Clozapine “should be considered” (C), quetiapine “may be considered” (C), and olanzapine “should not be considered” (B) for psychosis

- Donepezil or rivastigmine “should be considered” for dementia (B)

There is not consistency between the manuscripts. Abstracts in 2 of the publications2,4 link level of evidence to the summary of recommendations in the abstracts. The other 2 do not.

In all 4 documents the abstracts are written in randomized controlled trial format, which make them difficult to quickly review. They are in question and answer format. There are long blocks of text without figures or tables to aid in learning and retaining the recommendations.

No cost-effectiveness analysis is performed in the reviews. They recommend that deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus “may be considered” to improve Parkinson’s disease symptoms and reduce medication use. But at what cost?

Because of their perspective from a specialty, these guidelines lack relevance for the family physician. For example, olfactory testing, which they recommend, is impractical for primary care physicians. However, no recommendations discuss dose titration with commonly prescribed medications. There are 3 pages reviewing surgical therapy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Keith B. Holten, MD, 825 Locust Street, Wilmington, OH 45177. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Suchowersky O, Reich S, Perlmutter J, Zesiewicz T, Gronseth G, Weiner WJ. Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Practice Parameter: diagnosis and prognosis of new onset Parkinson disease (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2006;66:968-975.

2. Pahwa R, Factor SA, Lyons KE, et al. Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Practice Parameter: treatment of Parkinson disease with motor fluctuations and dyskinesia (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2006;66:983-995

3. Suchowersky O, Gronseth G, Perlmutter J, Reich S, Zesiewicz T, Weiner WJ. Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Practice Parameter: neuroprotective strategies and alternative therapies for Parkinson disease (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2006;66:976-982.