User login

The Modern Realities of Kidney Stones: Diagnosis

Q) I am new to practice and working in urgent care. I was discussing the diagnosis of kidney stones with my supervising physician. He said he does an intravenous pyelogram (IVP) to diagnose stones. He is a little “old school,” and I’m not sure he is right. What is “state of the art” in the work-up and acute treatment for kidney stones?

An IVP involves taking a series of x-rays following the injection of dye into a patient’s vein. As the dye moves through the bloodstream, the anatomy of the urinary system can be better visualized and the stone location identified, as the dye tends to accumulate at areas of obstruction. The downside to this test is that contrast can cause allergic reactions in some patients and can only be used in those with normal renal function. Also, a radiologist is required to be present during the procedure, and the test can take a long time to complete if a severe blockage is present.4

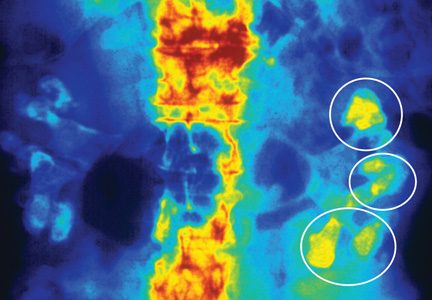

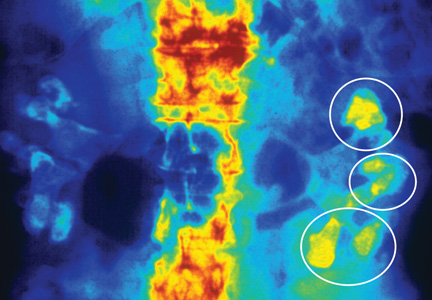

Today, noncontrast CT is considered the gold standard for imaging renal calculi because it is fast, safe (no worries for those with contrast allergy or renal impairment), and nearly 100% accurate.5

There are multiple options for treating kidney stones, though some are more invasive than others. For stones 2 cm or less identified in the upper or middle calyx and renal pelvis, extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) is the treatment of choice.5,6 The goal of ESWL is to break the stone into small particles that can then be expelled through the urinary system. Adjunct measures, including mechanical percussion, diuresis, and inversion therapy, are often used following lithotripsy to facilitate passage of stone fragments. Medications such as calcium blockers and α-receptor blockers are also used to improve outcomes after lithotripsy. In the past, obese patients had less success with lithotripsy; however, technological advances have improved outcomes in depths up to 17 cm from skin to stone.6

For stones in the lower pole of the kidney (and depending on the size of the stone), ESWL, percutaneous nephrolitholapaxy, retrograde flexible ureteronephroscopy, and partial nephrectomy are options for treatment.3,7 Using an intravenous urogram, measurements and angles are calculated to help determine which procedure would be best for a particular patient.7 In simple terms, narrow angles and longer tube distances make it more difficult for stone particles to exit the urinary system. Therefore, if these problems are identified, an invasive approach may be needed to remove a stone. Other important considerations include stone size, patient symptoms, evidence of infection, or obstruction.7

ESWL is an attractive option for stone removal because it is noninvasive, has a reasonable safety profile, and is less costly than other, more invasive measures. However, advances in endoscopic instrument design are reducing complications previously associated with more invasive approaches, while improving long-term stone-free outcome rates. There may be increased utilization of procedures such as percutaneous nephrolitholapaxy and retrograde flexible ureteronephroscopy in the future.

Kristina Unterseher, CNN-NP

PeaceHealth

St. John Medical Group

Longview, WA

REFERENCES

1. Fink HA, Wilt TJ, Eidman KE, et al. Medical management to prevent recurrent nephrolithiasis in adults: a systematic review for an American College of Physicians Clinical Guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(7):535-543.

2. Hiatt RA, Ettinger B, Caan B, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a low animal protein, high fiber diet in the prevention of recurrent calcium oxalate kidney stones. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;144(1):25-33.

3. Moe OW. Kidney stones: pathophysiology and medical management. Lancet. 2006; 367(9507):333-344.

4. American College of Radiology and Radiological Society of North America. Intravenous pyelogram (2013). www.radiologyinfo.org/en/info.cfm?pg=ivp. Accessed December 16, 2013.

5. Boyce CJ, Pickhardt PJ, Lawrence EM, et al. Prevalence of urolithiasis in asymptomatic adults: objective determination using low dose noncontrast computerized tomography. J Urol. 2010;183(3):1017-1021.

6. Christian C, Thorsten B. The preferred treatment for upper tract stones is extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) or ureteroscopic: pro ESWL. Urology. 2009;74(2):259-262.

7. Bourdoumis A, Papatsoris AG, Chrisofos M, Deliveliotis C. Lower pole stone management. Med Surg Urol. 2012. www.omicsonline.org/lower-pole-stone-management%20-2168-9857.S4-004.php?aid=7058?abstract _id=7058. Accessed December 16, 2013.

Q) I am new to practice and working in urgent care. I was discussing the diagnosis of kidney stones with my supervising physician. He said he does an intravenous pyelogram (IVP) to diagnose stones. He is a little “old school,” and I’m not sure he is right. What is “state of the art” in the work-up and acute treatment for kidney stones?

An IVP involves taking a series of x-rays following the injection of dye into a patient’s vein. As the dye moves through the bloodstream, the anatomy of the urinary system can be better visualized and the stone location identified, as the dye tends to accumulate at areas of obstruction. The downside to this test is that contrast can cause allergic reactions in some patients and can only be used in those with normal renal function. Also, a radiologist is required to be present during the procedure, and the test can take a long time to complete if a severe blockage is present.4

Today, noncontrast CT is considered the gold standard for imaging renal calculi because it is fast, safe (no worries for those with contrast allergy or renal impairment), and nearly 100% accurate.5

There are multiple options for treating kidney stones, though some are more invasive than others. For stones 2 cm or less identified in the upper or middle calyx and renal pelvis, extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) is the treatment of choice.5,6 The goal of ESWL is to break the stone into small particles that can then be expelled through the urinary system. Adjunct measures, including mechanical percussion, diuresis, and inversion therapy, are often used following lithotripsy to facilitate passage of stone fragments. Medications such as calcium blockers and α-receptor blockers are also used to improve outcomes after lithotripsy. In the past, obese patients had less success with lithotripsy; however, technological advances have improved outcomes in depths up to 17 cm from skin to stone.6

For stones in the lower pole of the kidney (and depending on the size of the stone), ESWL, percutaneous nephrolitholapaxy, retrograde flexible ureteronephroscopy, and partial nephrectomy are options for treatment.3,7 Using an intravenous urogram, measurements and angles are calculated to help determine which procedure would be best for a particular patient.7 In simple terms, narrow angles and longer tube distances make it more difficult for stone particles to exit the urinary system. Therefore, if these problems are identified, an invasive approach may be needed to remove a stone. Other important considerations include stone size, patient symptoms, evidence of infection, or obstruction.7

ESWL is an attractive option for stone removal because it is noninvasive, has a reasonable safety profile, and is less costly than other, more invasive measures. However, advances in endoscopic instrument design are reducing complications previously associated with more invasive approaches, while improving long-term stone-free outcome rates. There may be increased utilization of procedures such as percutaneous nephrolitholapaxy and retrograde flexible ureteronephroscopy in the future.

Kristina Unterseher, CNN-NP

PeaceHealth

St. John Medical Group

Longview, WA

REFERENCES

1. Fink HA, Wilt TJ, Eidman KE, et al. Medical management to prevent recurrent nephrolithiasis in adults: a systematic review for an American College of Physicians Clinical Guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(7):535-543.

2. Hiatt RA, Ettinger B, Caan B, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a low animal protein, high fiber diet in the prevention of recurrent calcium oxalate kidney stones. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;144(1):25-33.

3. Moe OW. Kidney stones: pathophysiology and medical management. Lancet. 2006; 367(9507):333-344.

4. American College of Radiology and Radiological Society of North America. Intravenous pyelogram (2013). www.radiologyinfo.org/en/info.cfm?pg=ivp. Accessed December 16, 2013.

5. Boyce CJ, Pickhardt PJ, Lawrence EM, et al. Prevalence of urolithiasis in asymptomatic adults: objective determination using low dose noncontrast computerized tomography. J Urol. 2010;183(3):1017-1021.

6. Christian C, Thorsten B. The preferred treatment for upper tract stones is extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) or ureteroscopic: pro ESWL. Urology. 2009;74(2):259-262.

7. Bourdoumis A, Papatsoris AG, Chrisofos M, Deliveliotis C. Lower pole stone management. Med Surg Urol. 2012. www.omicsonline.org/lower-pole-stone-management%20-2168-9857.S4-004.php?aid=7058?abstract _id=7058. Accessed December 16, 2013.

Q) I am new to practice and working in urgent care. I was discussing the diagnosis of kidney stones with my supervising physician. He said he does an intravenous pyelogram (IVP) to diagnose stones. He is a little “old school,” and I’m not sure he is right. What is “state of the art” in the work-up and acute treatment for kidney stones?

An IVP involves taking a series of x-rays following the injection of dye into a patient’s vein. As the dye moves through the bloodstream, the anatomy of the urinary system can be better visualized and the stone location identified, as the dye tends to accumulate at areas of obstruction. The downside to this test is that contrast can cause allergic reactions in some patients and can only be used in those with normal renal function. Also, a radiologist is required to be present during the procedure, and the test can take a long time to complete if a severe blockage is present.4

Today, noncontrast CT is considered the gold standard for imaging renal calculi because it is fast, safe (no worries for those with contrast allergy or renal impairment), and nearly 100% accurate.5

There are multiple options for treating kidney stones, though some are more invasive than others. For stones 2 cm or less identified in the upper or middle calyx and renal pelvis, extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) is the treatment of choice.5,6 The goal of ESWL is to break the stone into small particles that can then be expelled through the urinary system. Adjunct measures, including mechanical percussion, diuresis, and inversion therapy, are often used following lithotripsy to facilitate passage of stone fragments. Medications such as calcium blockers and α-receptor blockers are also used to improve outcomes after lithotripsy. In the past, obese patients had less success with lithotripsy; however, technological advances have improved outcomes in depths up to 17 cm from skin to stone.6

For stones in the lower pole of the kidney (and depending on the size of the stone), ESWL, percutaneous nephrolitholapaxy, retrograde flexible ureteronephroscopy, and partial nephrectomy are options for treatment.3,7 Using an intravenous urogram, measurements and angles are calculated to help determine which procedure would be best for a particular patient.7 In simple terms, narrow angles and longer tube distances make it more difficult for stone particles to exit the urinary system. Therefore, if these problems are identified, an invasive approach may be needed to remove a stone. Other important considerations include stone size, patient symptoms, evidence of infection, or obstruction.7

ESWL is an attractive option for stone removal because it is noninvasive, has a reasonable safety profile, and is less costly than other, more invasive measures. However, advances in endoscopic instrument design are reducing complications previously associated with more invasive approaches, while improving long-term stone-free outcome rates. There may be increased utilization of procedures such as percutaneous nephrolitholapaxy and retrograde flexible ureteronephroscopy in the future.

Kristina Unterseher, CNN-NP

PeaceHealth

St. John Medical Group

Longview, WA

REFERENCES

1. Fink HA, Wilt TJ, Eidman KE, et al. Medical management to prevent recurrent nephrolithiasis in adults: a systematic review for an American College of Physicians Clinical Guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(7):535-543.

2. Hiatt RA, Ettinger B, Caan B, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a low animal protein, high fiber diet in the prevention of recurrent calcium oxalate kidney stones. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;144(1):25-33.

3. Moe OW. Kidney stones: pathophysiology and medical management. Lancet. 2006; 367(9507):333-344.

4. American College of Radiology and Radiological Society of North America. Intravenous pyelogram (2013). www.radiologyinfo.org/en/info.cfm?pg=ivp. Accessed December 16, 2013.

5. Boyce CJ, Pickhardt PJ, Lawrence EM, et al. Prevalence of urolithiasis in asymptomatic adults: objective determination using low dose noncontrast computerized tomography. J Urol. 2010;183(3):1017-1021.

6. Christian C, Thorsten B. The preferred treatment for upper tract stones is extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) or ureteroscopic: pro ESWL. Urology. 2009;74(2):259-262.

7. Bourdoumis A, Papatsoris AG, Chrisofos M, Deliveliotis C. Lower pole stone management. Med Surg Urol. 2012. www.omicsonline.org/lower-pole-stone-management%20-2168-9857.S4-004.php?aid=7058?abstract _id=7058. Accessed December 16, 2013.

The Modern Realities of Kidney Stones: Preventing Reoccurrence

Q) A patient recently came in after an episode of kidney stones. He said he had never experienced such pain before (and this is a former Army Ranger!) and asked if there was anything he could do to keep it from happening again. I told him what I had learned in school (lots of fluids, no organ meats), but is there anything new?

Your patient has some reason for concern. For people who have had a symptomatic kidney stone, the likelihood of developing another within five years is 35% to 50% if no preventive action is taken.1 Certain factors—including family history, younger age at onset, and predisposing medical conditions (eg, hyperparathyroidism, diabetes, obesity, gout)—increase risk for recurrence.2,3

In the past, patients were often advised to restrict their dietary calcium intake to prevent calcium oxalate and/or calcium phosphate stones. However, more recent research has proven the opposite to be true: People with lower dietary calcium intake can be at greater risk for kidney stones.1-3 Therefore, encourage patients to consume about 800 to 1,200 mg/d of dietary calcium. Oral supplementation does not seem to yield the same protective benefits as dietary calcium. This may be related to absorption.1

Diets high in oxalates (eg, chocolate, nuts, spinach) can increase risk for stone formation, particularly in patients who have bowel diseases that cause inflammation or a history of a bowel resection.2 Animal protein in the diet can cause hypercalcinuria and increased uric acid levels, which is particularly problematic for individuals with gout or inflammatory arthritis. High-sodium diets can cause higher urinary calcium oxalate levels, while diets high in phosphorus (particularly dark cola soft drinks) can increase risk for stone formation. Advise your patient to avoid foods high in oxalates, animal proteins, sodium, and phosphorus.2

Dehydration, either due to exercise or poor fluid intake, can result in concentrated urine, which facilitates stone formation. While opinions differ on the benefits of certain dietary restrictions, most research supports the idea that generous fluid intake is the most successful intervention in preventing recurrence of stone formation (regardless of underlying cause). Diluting the urine decreases the concentration of solutes responsible for stone formation.1-3

If the conservative measures of dietary restriction and adequate hydration fail, medications may be beneficial, depending on stone type or underlying metabolic condition. Thiazide diuretics can help lower urinary calcium by enhancing reabsorption of calcium from the distal convoluted tubule and sodium excretion; however, they should be used cautiously due to the risk for adverse effects such as dizziness and lightheadedness.1,3 Allopurinol can lower uric acid levels, decreasing recurrence of both uric acid and calcium oxalate stones. Hypocitraturia is prevalent in 20% to 60% of persons with stones; prescribing potassium citrate can inhibit crystal growth of calcium phosphate and calcium oxalate in urine.2

To help patients prevent stone recurrence, perform a comprehensive assessment of their dietary and lifestyle habits and medical history to identify possible contributing factors. Educate patients on adequate dietary calcium intake, generous water intake to keep urine dilute, and avoidance of dietary triggers.

Nephrolithiasis should be considered a manifestation of another underlying problem. If a patient presents with a kidney stone, attempt to identify the cause—not only to try to prevent recurrence, but also to identify a previously unrecognized disease process.

Kristina Unterseher, CNN-NP

PeaceHealth

St. John Medical Group

Longview, WA

REFERENCES

1. Fink HA, Wilt TJ, Eidman KE, et al. Medical management to prevent recurrent nephrolithiasis in adults: a systematic review for an American College of Physicians Clinical Guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(7):535-543.

2. Hiatt RA, Ettinger B, Caan B, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a low animal protein, high fiber diet in the prevention of recurrent calcium oxalate kidney stones. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;144(1):25-33.

3. Moe OW. Kidney stones: pathophysiology and medical management. Lancet. 2006; 367(9507):333-344.

4. American College of Radiology and Radiological Society of North America. Intravenous pyelogram (2013). www.radiologyinfo.org/en/info.cfm?pg=ivp. Accessed December 16, 2013.

5. Boyce CJ, Pickhardt PJ, Lawrence EM, et al. Prevalence of urolithiasis in asymptomatic adults: objective determination using low dose noncontrast computerized tomography. J Urol. 2010;183(3):1017-1021.

6. Christian C, Thorsten B. The preferred treatment for upper tract stones is extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) or ureteroscopic: pro ESWL. Urology. 2009;74(2):259-262.

7. Bourdoumis A, Papatsoris AG, Chrisofos M, Deliveliotis C. Lower pole stone management. Med Surg Urol. 2012. www.omicsonline.org/lower-pole-stone-management%20-2168-9857.S4-004.php?aid=7058?abstract _id=7058. Accessed December 16, 2013.

Q) A patient recently came in after an episode of kidney stones. He said he had never experienced such pain before (and this is a former Army Ranger!) and asked if there was anything he could do to keep it from happening again. I told him what I had learned in school (lots of fluids, no organ meats), but is there anything new?

Your patient has some reason for concern. For people who have had a symptomatic kidney stone, the likelihood of developing another within five years is 35% to 50% if no preventive action is taken.1 Certain factors—including family history, younger age at onset, and predisposing medical conditions (eg, hyperparathyroidism, diabetes, obesity, gout)—increase risk for recurrence.2,3

In the past, patients were often advised to restrict their dietary calcium intake to prevent calcium oxalate and/or calcium phosphate stones. However, more recent research has proven the opposite to be true: People with lower dietary calcium intake can be at greater risk for kidney stones.1-3 Therefore, encourage patients to consume about 800 to 1,200 mg/d of dietary calcium. Oral supplementation does not seem to yield the same protective benefits as dietary calcium. This may be related to absorption.1

Diets high in oxalates (eg, chocolate, nuts, spinach) can increase risk for stone formation, particularly in patients who have bowel diseases that cause inflammation or a history of a bowel resection.2 Animal protein in the diet can cause hypercalcinuria and increased uric acid levels, which is particularly problematic for individuals with gout or inflammatory arthritis. High-sodium diets can cause higher urinary calcium oxalate levels, while diets high in phosphorus (particularly dark cola soft drinks) can increase risk for stone formation. Advise your patient to avoid foods high in oxalates, animal proteins, sodium, and phosphorus.2

Dehydration, either due to exercise or poor fluid intake, can result in concentrated urine, which facilitates stone formation. While opinions differ on the benefits of certain dietary restrictions, most research supports the idea that generous fluid intake is the most successful intervention in preventing recurrence of stone formation (regardless of underlying cause). Diluting the urine decreases the concentration of solutes responsible for stone formation.1-3

If the conservative measures of dietary restriction and adequate hydration fail, medications may be beneficial, depending on stone type or underlying metabolic condition. Thiazide diuretics can help lower urinary calcium by enhancing reabsorption of calcium from the distal convoluted tubule and sodium excretion; however, they should be used cautiously due to the risk for adverse effects such as dizziness and lightheadedness.1,3 Allopurinol can lower uric acid levels, decreasing recurrence of both uric acid and calcium oxalate stones. Hypocitraturia is prevalent in 20% to 60% of persons with stones; prescribing potassium citrate can inhibit crystal growth of calcium phosphate and calcium oxalate in urine.2

To help patients prevent stone recurrence, perform a comprehensive assessment of their dietary and lifestyle habits and medical history to identify possible contributing factors. Educate patients on adequate dietary calcium intake, generous water intake to keep urine dilute, and avoidance of dietary triggers.

Nephrolithiasis should be considered a manifestation of another underlying problem. If a patient presents with a kidney stone, attempt to identify the cause—not only to try to prevent recurrence, but also to identify a previously unrecognized disease process.

Kristina Unterseher, CNN-NP

PeaceHealth

St. John Medical Group

Longview, WA

REFERENCES

1. Fink HA, Wilt TJ, Eidman KE, et al. Medical management to prevent recurrent nephrolithiasis in adults: a systematic review for an American College of Physicians Clinical Guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(7):535-543.

2. Hiatt RA, Ettinger B, Caan B, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a low animal protein, high fiber diet in the prevention of recurrent calcium oxalate kidney stones. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;144(1):25-33.

3. Moe OW. Kidney stones: pathophysiology and medical management. Lancet. 2006; 367(9507):333-344.

4. American College of Radiology and Radiological Society of North America. Intravenous pyelogram (2013). www.radiologyinfo.org/en/info.cfm?pg=ivp. Accessed December 16, 2013.

5. Boyce CJ, Pickhardt PJ, Lawrence EM, et al. Prevalence of urolithiasis in asymptomatic adults: objective determination using low dose noncontrast computerized tomography. J Urol. 2010;183(3):1017-1021.

6. Christian C, Thorsten B. The preferred treatment for upper tract stones is extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) or ureteroscopic: pro ESWL. Urology. 2009;74(2):259-262.

7. Bourdoumis A, Papatsoris AG, Chrisofos M, Deliveliotis C. Lower pole stone management. Med Surg Urol. 2012. www.omicsonline.org/lower-pole-stone-management%20-2168-9857.S4-004.php?aid=7058?abstract _id=7058. Accessed December 16, 2013.

Q) A patient recently came in after an episode of kidney stones. He said he had never experienced such pain before (and this is a former Army Ranger!) and asked if there was anything he could do to keep it from happening again. I told him what I had learned in school (lots of fluids, no organ meats), but is there anything new?

Your patient has some reason for concern. For people who have had a symptomatic kidney stone, the likelihood of developing another within five years is 35% to 50% if no preventive action is taken.1 Certain factors—including family history, younger age at onset, and predisposing medical conditions (eg, hyperparathyroidism, diabetes, obesity, gout)—increase risk for recurrence.2,3

In the past, patients were often advised to restrict their dietary calcium intake to prevent calcium oxalate and/or calcium phosphate stones. However, more recent research has proven the opposite to be true: People with lower dietary calcium intake can be at greater risk for kidney stones.1-3 Therefore, encourage patients to consume about 800 to 1,200 mg/d of dietary calcium. Oral supplementation does not seem to yield the same protective benefits as dietary calcium. This may be related to absorption.1

Diets high in oxalates (eg, chocolate, nuts, spinach) can increase risk for stone formation, particularly in patients who have bowel diseases that cause inflammation or a history of a bowel resection.2 Animal protein in the diet can cause hypercalcinuria and increased uric acid levels, which is particularly problematic for individuals with gout or inflammatory arthritis. High-sodium diets can cause higher urinary calcium oxalate levels, while diets high in phosphorus (particularly dark cola soft drinks) can increase risk for stone formation. Advise your patient to avoid foods high in oxalates, animal proteins, sodium, and phosphorus.2

Dehydration, either due to exercise or poor fluid intake, can result in concentrated urine, which facilitates stone formation. While opinions differ on the benefits of certain dietary restrictions, most research supports the idea that generous fluid intake is the most successful intervention in preventing recurrence of stone formation (regardless of underlying cause). Diluting the urine decreases the concentration of solutes responsible for stone formation.1-3

If the conservative measures of dietary restriction and adequate hydration fail, medications may be beneficial, depending on stone type or underlying metabolic condition. Thiazide diuretics can help lower urinary calcium by enhancing reabsorption of calcium from the distal convoluted tubule and sodium excretion; however, they should be used cautiously due to the risk for adverse effects such as dizziness and lightheadedness.1,3 Allopurinol can lower uric acid levels, decreasing recurrence of both uric acid and calcium oxalate stones. Hypocitraturia is prevalent in 20% to 60% of persons with stones; prescribing potassium citrate can inhibit crystal growth of calcium phosphate and calcium oxalate in urine.2

To help patients prevent stone recurrence, perform a comprehensive assessment of their dietary and lifestyle habits and medical history to identify possible contributing factors. Educate patients on adequate dietary calcium intake, generous water intake to keep urine dilute, and avoidance of dietary triggers.

Nephrolithiasis should be considered a manifestation of another underlying problem. If a patient presents with a kidney stone, attempt to identify the cause—not only to try to prevent recurrence, but also to identify a previously unrecognized disease process.

Kristina Unterseher, CNN-NP

PeaceHealth

St. John Medical Group

Longview, WA

REFERENCES

1. Fink HA, Wilt TJ, Eidman KE, et al. Medical management to prevent recurrent nephrolithiasis in adults: a systematic review for an American College of Physicians Clinical Guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(7):535-543.

2. Hiatt RA, Ettinger B, Caan B, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a low animal protein, high fiber diet in the prevention of recurrent calcium oxalate kidney stones. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;144(1):25-33.

3. Moe OW. Kidney stones: pathophysiology and medical management. Lancet. 2006; 367(9507):333-344.

4. American College of Radiology and Radiological Society of North America. Intravenous pyelogram (2013). www.radiologyinfo.org/en/info.cfm?pg=ivp. Accessed December 16, 2013.

5. Boyce CJ, Pickhardt PJ, Lawrence EM, et al. Prevalence of urolithiasis in asymptomatic adults: objective determination using low dose noncontrast computerized tomography. J Urol. 2010;183(3):1017-1021.

6. Christian C, Thorsten B. The preferred treatment for upper tract stones is extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) or ureteroscopic: pro ESWL. Urology. 2009;74(2):259-262.

7. Bourdoumis A, Papatsoris AG, Chrisofos M, Deliveliotis C. Lower pole stone management. Med Surg Urol. 2012. www.omicsonline.org/lower-pole-stone-management%20-2168-9857.S4-004.php?aid=7058?abstract _id=7058. Accessed December 16, 2013.