User login

Recalcitrant genital papules

A 21-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with a 2-month history of painless genital and perianal lesions. The patient reported having unprotected sex in recent months, but had no prior history of oral, penile, or anal mucosal lesions or ulcers. He was not on any medications or immunosuppressive agents and noted that the lesions did not represent a recurrence. He also reported a nonspecific, asymptomatic rash on his trunk and extremities that had been present for an unknown period of time.

The patient indicated that his primary care physician had looked at the genital/perianal lesions and told him they were genital warts. Previous treatments included an over-the-counter wart medication, cryotherapy, and a course of imiquimod, but none had helped.

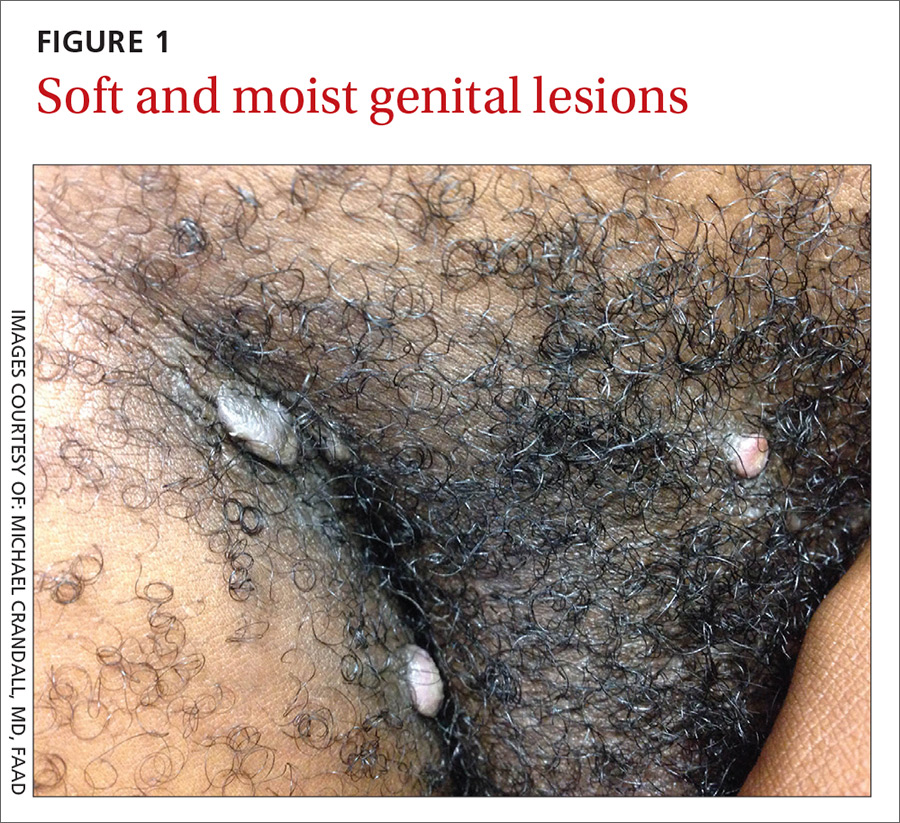

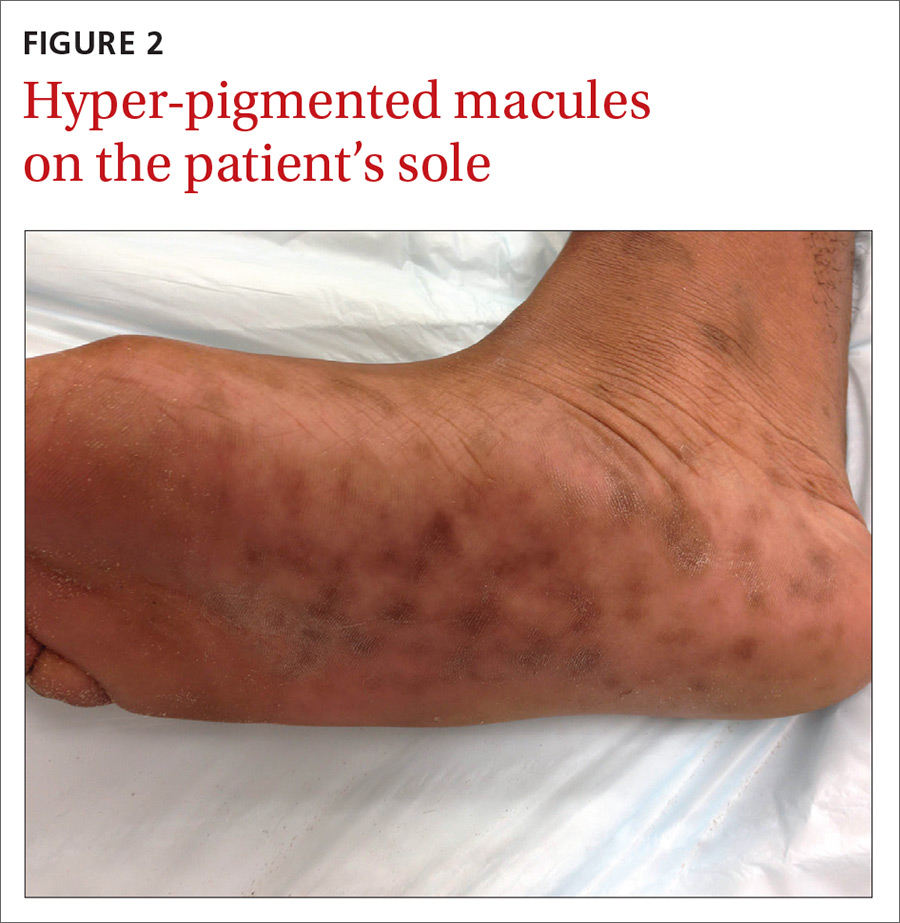

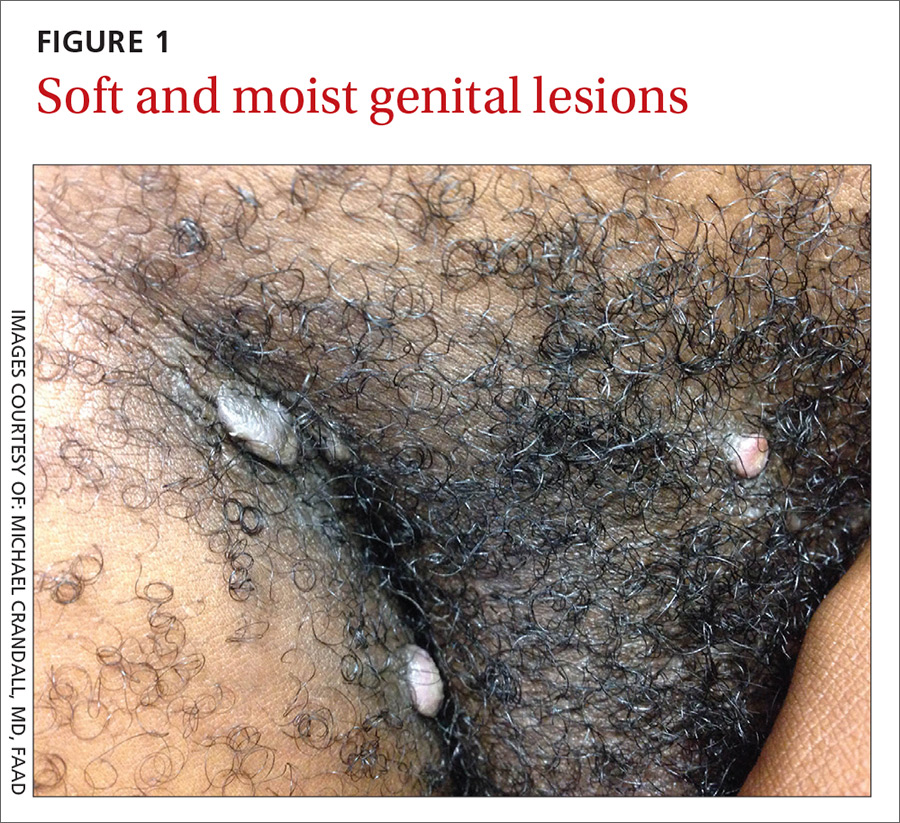

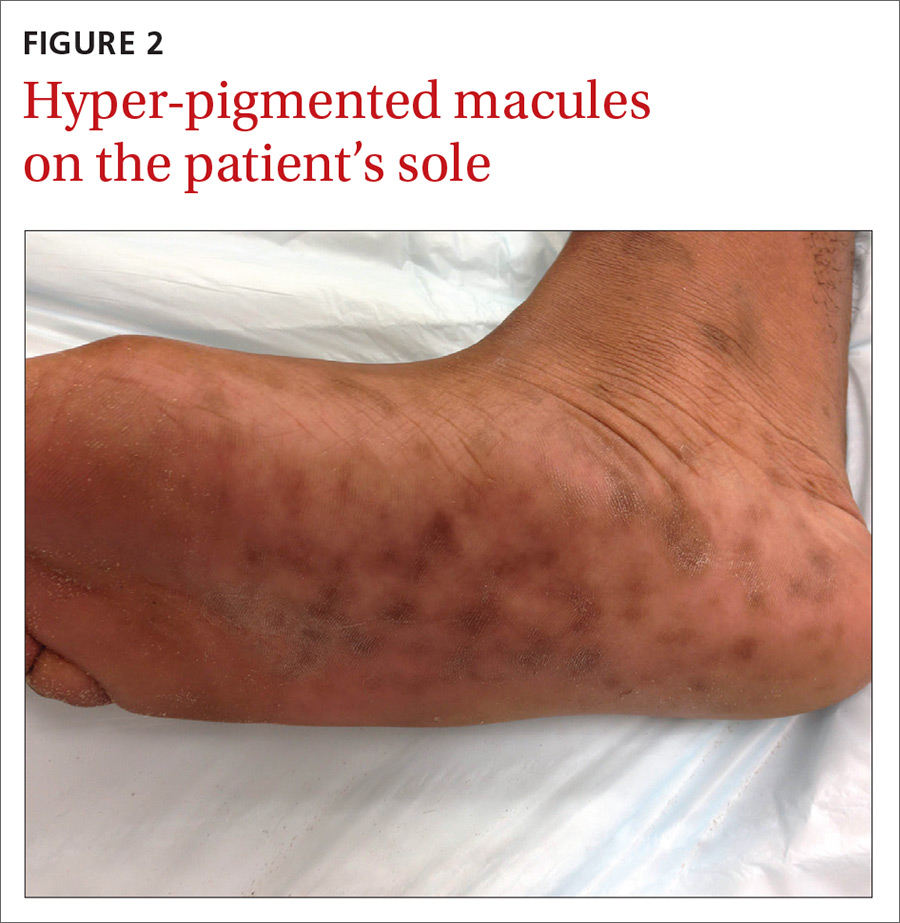

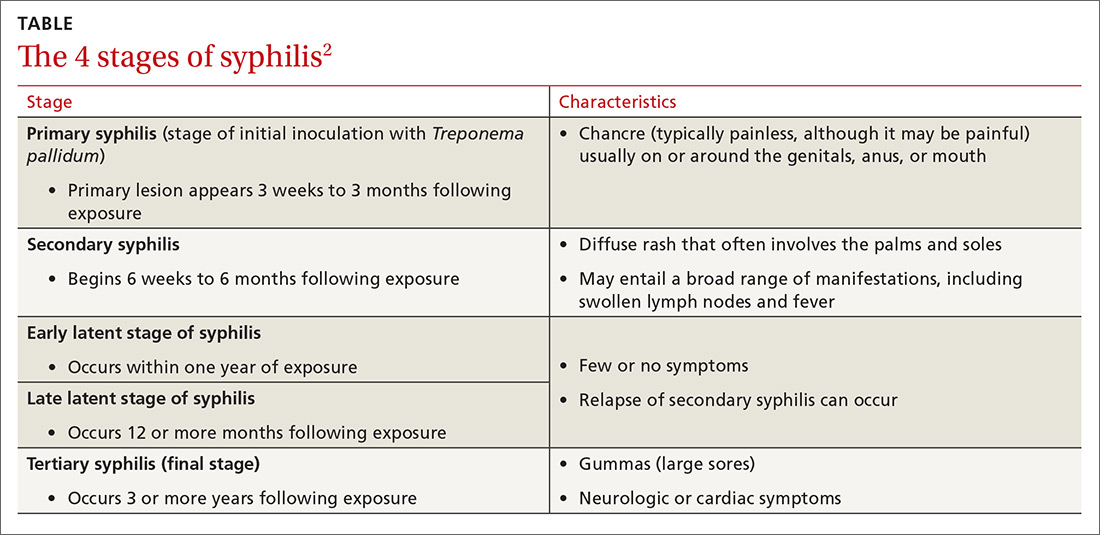

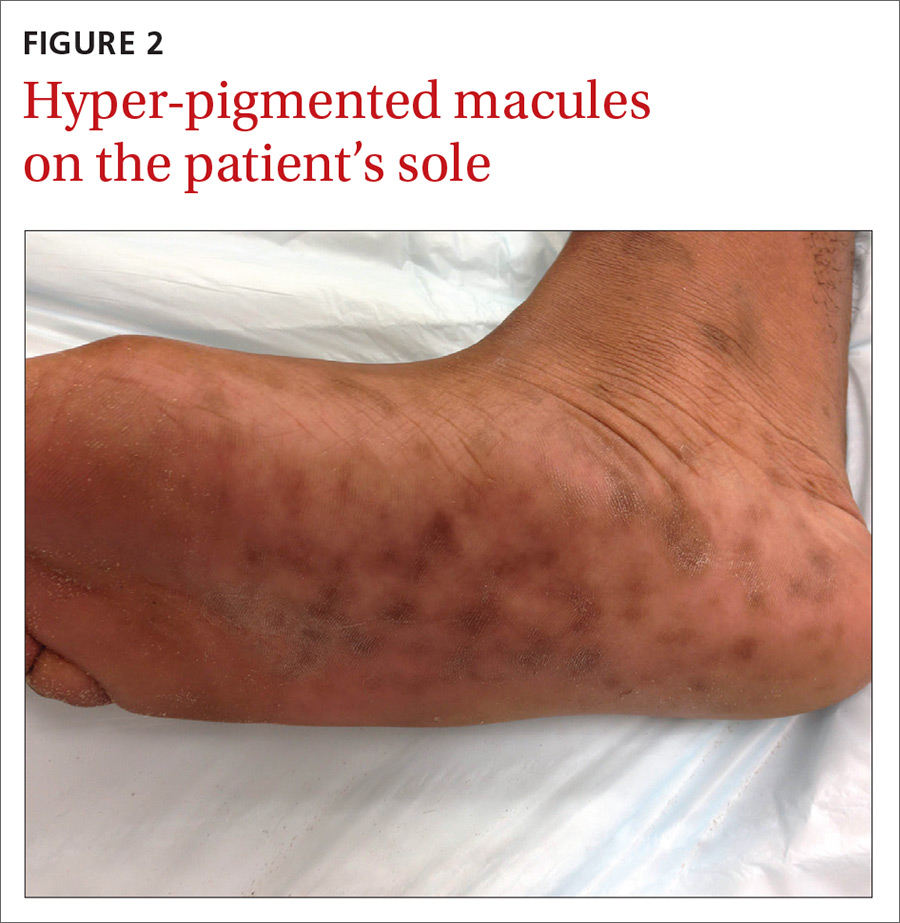

The physical examination revealed multiple soft, moist, beefy papules and plaques around the genital area (FIGURE 1) and perianal region. In addition, there were multiple hyper-pigmented macules on the patient’s palms and soles (FIGURE 2), and reticulated, patchy eruptions on his arms, chest (FIGURE 3), and back.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Secondary syphilis

The appearance of the genital and perianal lesions was consistent with condylomata lata—a cutaneous sign of secondary syphilis—rather than genital warts. The presence of a rash on the patient’s trunk and extremities further supported this diagnosis. We did a rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test and a Treponema pallidum particle agglutination test; we also tested for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The patient’s RPR titer was 1:128, and the T pallidum antibody test came back positive. HIV-1 and HIV-2 serology were negative.

Appearance of the lesions was a giveaway. Condylomata lata are flat-topped, broad papules that are usually located on folds of moist skin (particularly the genitals and anus), and have a smooth, gray, moist surface. Although they can be lobulated, they do not have the classic digitate projections that are characteristic of genital warts. A nonpruritic, symmetric, “raw ham”-colored papular eruption on a patient’s trunk, palms, and soles is also characteristic of secondary syphilis.1 In this case, the reticular pattern on the patient’s chest represented the commonly seen lenticular rash of secondary syphilis.

Cutaneous lesions of secondary syphilis contain numerous spirochetes (T pallidum) and are highly infectious. Systemic symptoms of secondary syphilis may include fatigue, generalized lymphadenopathy, arthralgia, myalgia, pharyngitis, and headache.

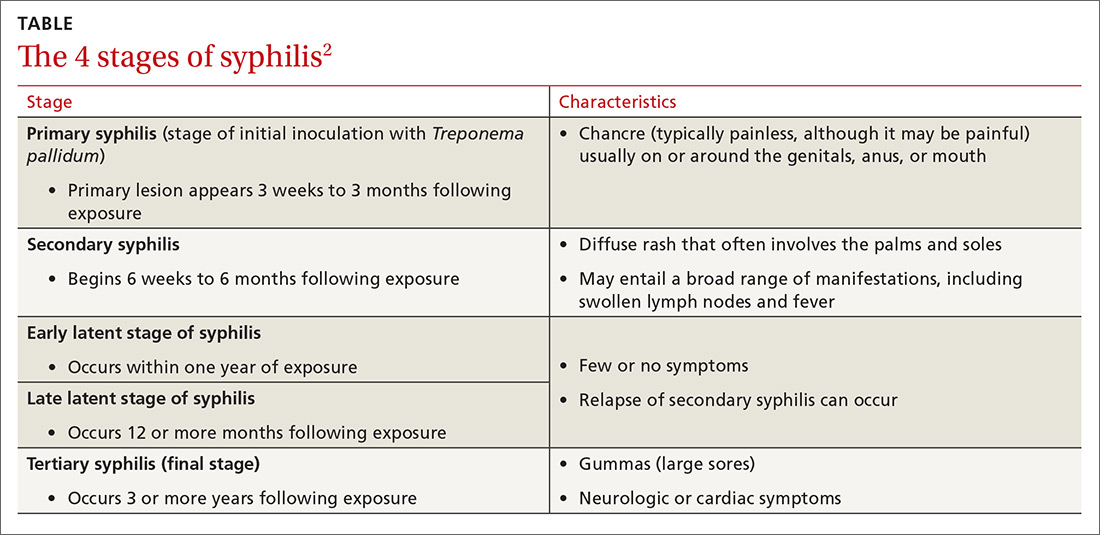

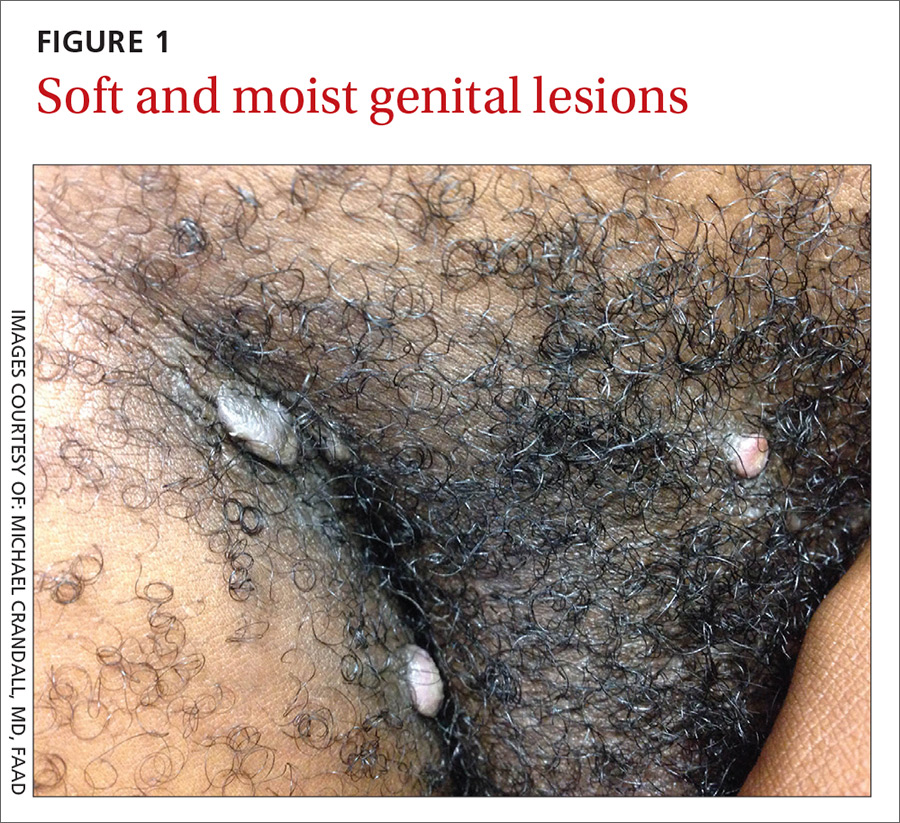

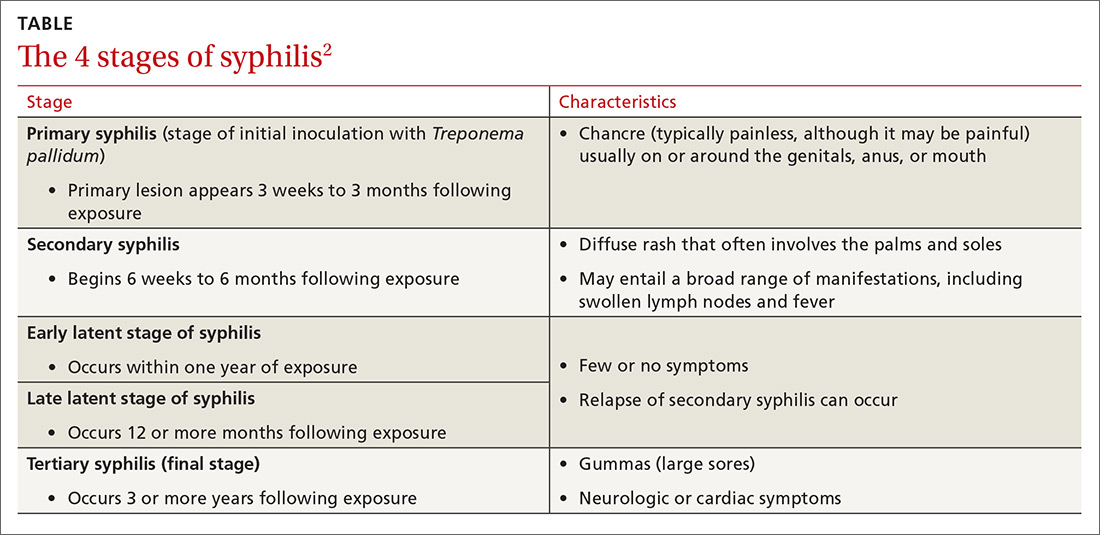

Some patients may report having a recent chancre—a painless, self-limiting ulcer in the genital area—which is characteristic of primary syphilis (see “Single nontender ulcer on the glans,” J Fam Pract. 2017;66:253-255). For more on the stages of syphilis, see the TABLE2. Our patient did not remember ever having a chancre.

Increase in cases. Rates of primary and secondary syphilis have increased in the past decade. In 2014, approximately 20,000 syphilis cases were reported—a record high since 1994.3 Men who have sex with men are particularly affected; however, increases in infection rates have also been noted in women and across people of all ages and ethnicities.3

Rule out other causes of genital lesions

Condyloma acuminata, commonly called genital warts, are localized human papilloma virus (HPV) infections that appear as discrete, gray to pale pink, lobulated papules that may coalesce to form a large, cauliflower-like mass. They are sexually transmitted and commonly involve the genital and anal areas. While physicians may confuse condylomata lata with genital warts, diffuse skin rashes and constitutional symptoms are not usually seen with genital warts.4

Fordyce spots are small, whitish, raised papules on the glans or the shaft of the penis or the vulva of the vagina. They may also appear on the lips and oral mucosa. They are a result of prominent sebaceous glands and are harmless. They are not infectious or sexually transmitted.5,6

Lymphogranuloma venereum is an uncommon sexually transmitted disease caused by Chlamydia trachomatis. It is characterized by genital papules or ulcers, followed by bilateral, suppurative, inguinal adenitis known as buboes. The buboes may breakdown, form multiple fistulous openings, and discharge purulent material.6

Acute HIV may present with flu-like symptoms and well-circumscribed maculopapular rashes on the face, neck, and upper trunk. The palms and soles may also be affected. Patients with HIV may also develop genital plaque-like lesions from herpes simplex virus-2, genital warts from HPV, molluscum contagiosum, and, not uncommonly, anogenital malignancies.7,8

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (CARP) is a disorder that occurs predominantly in young adults and teenagers, with cosmetically displeasing brown scaling macules that may coalesce to form patches or plaques affecting the neck, chest, back, and axillae. It is often mistaken for tinea versicolor.9 In this case, the eruption on the chest closely resembled CARP, but a diagnosis of CARP would not have explained the genital lesions.

Confirm diagnosis with treponemal tests

Syphilis is often a clinical diagnosis with pathologic confirmation. Patients suspected of having syphilis should be screened with nontreponemal tests, such as the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test or the RPR test, which become positive within 3 weeks of developing primary syphilis.

Diagnosis is confirmed with specific treponemal testing, such as with a fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption assay or the T pallidum particle agglutination test. HIV testing is recommended for all patients with syphilis.

Penicillin G is the mainstay of treatment

Proper selection of penicillin is paramount in the treatment of syphilis. Primary, secondary, and early latent syphilis are treated with an intramuscular injection of 2.4 million units of long-acting benzathine penicillin G. Patients with late latent or latent syphilis of unknown duration are treated with 3 doses of the same injection at weekly intervals, totaling 7.2 million units of benzathine penicillin G.10 Certain penicillin preparations (eg, combinations of benzathine penicillin and procaine penicillin) are not appropriate treatments because they do not provide adequate amounts of the antibiotic.

Watch for this reaction. Approximately 30% of patients following penicillin treatment for spirochete infection develop a Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction (JHR).11 JHR is characterized by an abrupt onset of fever, chills, myalgia, tachycardia, vasodilatation with flushing, exacerbated maculopapular skin rash, or mild hypotension. Care for JHR is generally supportive.

Our patient received an intramuscular injection of 2.4 million units of long-acting benzathine penicillin G. His skin eruption and condylomata lata lesions were completely resolved at follow-up 6 months later.

As recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,10 our patient’s RPR titers were repeated at 6 months and again at 12 months to verify a four-fold decline, indicating successful treatment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Anne Bartels, MD, General Medicine, Naval Hospital Camp Lejeune, 100 Brewster Blvd., Camp Lejeune, NC 28547; [email protected].

1. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Secondary syphilis. In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier; 2011:348-350.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Syphilis—CDC Fact Sheet. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/stdfact-syphilis.htm. Accessed May 31, 2017.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Syphilis. November 17, 2015. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats14/syphilis.htm. Accessed March 30, 2017.

4. Karnes JB, Usatine RP. Management of external genital warts. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90:312-318.

5. DuVivier A. Disorders of the sebaceous, sweat and apocrine glands. In: DuVivier A. Atlas of Clinical Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier; 2013:326-330.

6. Mabey D, Peeling RW. Lymphogranuloma venereum. Sex Transm Infect. 2002;78:90-92.

7. Altman K, Vanness E, Westergaard RP. Cutaneous manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus: a clinical update. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2015;17:464.

8. Maurer TA. Dermatologic manifestations of HIV infection. Top HIV Med. 2005;13:149-154.

9. Hudacek KD, Haque MS, Hochberg AL, et al. An unusual variant of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis masquerading as tinea versicolor. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:505-508.

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2010. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2010/STD-Treatment-2010-RR5912.pdf#. Accessed June 8, 2017.

11. Yang CJ, Lee NY, Lin YH, et al. Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction after penicillin therapy among patients with syphilis in the era of the hiv infection epidemic: incidence and risk factors. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:976-979.

A 21-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with a 2-month history of painless genital and perianal lesions. The patient reported having unprotected sex in recent months, but had no prior history of oral, penile, or anal mucosal lesions or ulcers. He was not on any medications or immunosuppressive agents and noted that the lesions did not represent a recurrence. He also reported a nonspecific, asymptomatic rash on his trunk and extremities that had been present for an unknown period of time.

The patient indicated that his primary care physician had looked at the genital/perianal lesions and told him they were genital warts. Previous treatments included an over-the-counter wart medication, cryotherapy, and a course of imiquimod, but none had helped.

The physical examination revealed multiple soft, moist, beefy papules and plaques around the genital area (FIGURE 1) and perianal region. In addition, there were multiple hyper-pigmented macules on the patient’s palms and soles (FIGURE 2), and reticulated, patchy eruptions on his arms, chest (FIGURE 3), and back.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Secondary syphilis

The appearance of the genital and perianal lesions was consistent with condylomata lata—a cutaneous sign of secondary syphilis—rather than genital warts. The presence of a rash on the patient’s trunk and extremities further supported this diagnosis. We did a rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test and a Treponema pallidum particle agglutination test; we also tested for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The patient’s RPR titer was 1:128, and the T pallidum antibody test came back positive. HIV-1 and HIV-2 serology were negative.

Appearance of the lesions was a giveaway. Condylomata lata are flat-topped, broad papules that are usually located on folds of moist skin (particularly the genitals and anus), and have a smooth, gray, moist surface. Although they can be lobulated, they do not have the classic digitate projections that are characteristic of genital warts. A nonpruritic, symmetric, “raw ham”-colored papular eruption on a patient’s trunk, palms, and soles is also characteristic of secondary syphilis.1 In this case, the reticular pattern on the patient’s chest represented the commonly seen lenticular rash of secondary syphilis.

Cutaneous lesions of secondary syphilis contain numerous spirochetes (T pallidum) and are highly infectious. Systemic symptoms of secondary syphilis may include fatigue, generalized lymphadenopathy, arthralgia, myalgia, pharyngitis, and headache.

Some patients may report having a recent chancre—a painless, self-limiting ulcer in the genital area—which is characteristic of primary syphilis (see “Single nontender ulcer on the glans,” J Fam Pract. 2017;66:253-255). For more on the stages of syphilis, see the TABLE2. Our patient did not remember ever having a chancre.

Increase in cases. Rates of primary and secondary syphilis have increased in the past decade. In 2014, approximately 20,000 syphilis cases were reported—a record high since 1994.3 Men who have sex with men are particularly affected; however, increases in infection rates have also been noted in women and across people of all ages and ethnicities.3

Rule out other causes of genital lesions

Condyloma acuminata, commonly called genital warts, are localized human papilloma virus (HPV) infections that appear as discrete, gray to pale pink, lobulated papules that may coalesce to form a large, cauliflower-like mass. They are sexually transmitted and commonly involve the genital and anal areas. While physicians may confuse condylomata lata with genital warts, diffuse skin rashes and constitutional symptoms are not usually seen with genital warts.4

Fordyce spots are small, whitish, raised papules on the glans or the shaft of the penis or the vulva of the vagina. They may also appear on the lips and oral mucosa. They are a result of prominent sebaceous glands and are harmless. They are not infectious or sexually transmitted.5,6

Lymphogranuloma venereum is an uncommon sexually transmitted disease caused by Chlamydia trachomatis. It is characterized by genital papules or ulcers, followed by bilateral, suppurative, inguinal adenitis known as buboes. The buboes may breakdown, form multiple fistulous openings, and discharge purulent material.6

Acute HIV may present with flu-like symptoms and well-circumscribed maculopapular rashes on the face, neck, and upper trunk. The palms and soles may also be affected. Patients with HIV may also develop genital plaque-like lesions from herpes simplex virus-2, genital warts from HPV, molluscum contagiosum, and, not uncommonly, anogenital malignancies.7,8

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (CARP) is a disorder that occurs predominantly in young adults and teenagers, with cosmetically displeasing brown scaling macules that may coalesce to form patches or plaques affecting the neck, chest, back, and axillae. It is often mistaken for tinea versicolor.9 In this case, the eruption on the chest closely resembled CARP, but a diagnosis of CARP would not have explained the genital lesions.

Confirm diagnosis with treponemal tests

Syphilis is often a clinical diagnosis with pathologic confirmation. Patients suspected of having syphilis should be screened with nontreponemal tests, such as the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test or the RPR test, which become positive within 3 weeks of developing primary syphilis.

Diagnosis is confirmed with specific treponemal testing, such as with a fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption assay or the T pallidum particle agglutination test. HIV testing is recommended for all patients with syphilis.

Penicillin G is the mainstay of treatment

Proper selection of penicillin is paramount in the treatment of syphilis. Primary, secondary, and early latent syphilis are treated with an intramuscular injection of 2.4 million units of long-acting benzathine penicillin G. Patients with late latent or latent syphilis of unknown duration are treated with 3 doses of the same injection at weekly intervals, totaling 7.2 million units of benzathine penicillin G.10 Certain penicillin preparations (eg, combinations of benzathine penicillin and procaine penicillin) are not appropriate treatments because they do not provide adequate amounts of the antibiotic.

Watch for this reaction. Approximately 30% of patients following penicillin treatment for spirochete infection develop a Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction (JHR).11 JHR is characterized by an abrupt onset of fever, chills, myalgia, tachycardia, vasodilatation with flushing, exacerbated maculopapular skin rash, or mild hypotension. Care for JHR is generally supportive.

Our patient received an intramuscular injection of 2.4 million units of long-acting benzathine penicillin G. His skin eruption and condylomata lata lesions were completely resolved at follow-up 6 months later.

As recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,10 our patient’s RPR titers were repeated at 6 months and again at 12 months to verify a four-fold decline, indicating successful treatment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Anne Bartels, MD, General Medicine, Naval Hospital Camp Lejeune, 100 Brewster Blvd., Camp Lejeune, NC 28547; [email protected].

A 21-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with a 2-month history of painless genital and perianal lesions. The patient reported having unprotected sex in recent months, but had no prior history of oral, penile, or anal mucosal lesions or ulcers. He was not on any medications or immunosuppressive agents and noted that the lesions did not represent a recurrence. He also reported a nonspecific, asymptomatic rash on his trunk and extremities that had been present for an unknown period of time.

The patient indicated that his primary care physician had looked at the genital/perianal lesions and told him they were genital warts. Previous treatments included an over-the-counter wart medication, cryotherapy, and a course of imiquimod, but none had helped.

The physical examination revealed multiple soft, moist, beefy papules and plaques around the genital area (FIGURE 1) and perianal region. In addition, there were multiple hyper-pigmented macules on the patient’s palms and soles (FIGURE 2), and reticulated, patchy eruptions on his arms, chest (FIGURE 3), and back.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Secondary syphilis

The appearance of the genital and perianal lesions was consistent with condylomata lata—a cutaneous sign of secondary syphilis—rather than genital warts. The presence of a rash on the patient’s trunk and extremities further supported this diagnosis. We did a rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test and a Treponema pallidum particle agglutination test; we also tested for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The patient’s RPR titer was 1:128, and the T pallidum antibody test came back positive. HIV-1 and HIV-2 serology were negative.

Appearance of the lesions was a giveaway. Condylomata lata are flat-topped, broad papules that are usually located on folds of moist skin (particularly the genitals and anus), and have a smooth, gray, moist surface. Although they can be lobulated, they do not have the classic digitate projections that are characteristic of genital warts. A nonpruritic, symmetric, “raw ham”-colored papular eruption on a patient’s trunk, palms, and soles is also characteristic of secondary syphilis.1 In this case, the reticular pattern on the patient’s chest represented the commonly seen lenticular rash of secondary syphilis.

Cutaneous lesions of secondary syphilis contain numerous spirochetes (T pallidum) and are highly infectious. Systemic symptoms of secondary syphilis may include fatigue, generalized lymphadenopathy, arthralgia, myalgia, pharyngitis, and headache.

Some patients may report having a recent chancre—a painless, self-limiting ulcer in the genital area—which is characteristic of primary syphilis (see “Single nontender ulcer on the glans,” J Fam Pract. 2017;66:253-255). For more on the stages of syphilis, see the TABLE2. Our patient did not remember ever having a chancre.

Increase in cases. Rates of primary and secondary syphilis have increased in the past decade. In 2014, approximately 20,000 syphilis cases were reported—a record high since 1994.3 Men who have sex with men are particularly affected; however, increases in infection rates have also been noted in women and across people of all ages and ethnicities.3

Rule out other causes of genital lesions

Condyloma acuminata, commonly called genital warts, are localized human papilloma virus (HPV) infections that appear as discrete, gray to pale pink, lobulated papules that may coalesce to form a large, cauliflower-like mass. They are sexually transmitted and commonly involve the genital and anal areas. While physicians may confuse condylomata lata with genital warts, diffuse skin rashes and constitutional symptoms are not usually seen with genital warts.4

Fordyce spots are small, whitish, raised papules on the glans or the shaft of the penis or the vulva of the vagina. They may also appear on the lips and oral mucosa. They are a result of prominent sebaceous glands and are harmless. They are not infectious or sexually transmitted.5,6

Lymphogranuloma venereum is an uncommon sexually transmitted disease caused by Chlamydia trachomatis. It is characterized by genital papules or ulcers, followed by bilateral, suppurative, inguinal adenitis known as buboes. The buboes may breakdown, form multiple fistulous openings, and discharge purulent material.6

Acute HIV may present with flu-like symptoms and well-circumscribed maculopapular rashes on the face, neck, and upper trunk. The palms and soles may also be affected. Patients with HIV may also develop genital plaque-like lesions from herpes simplex virus-2, genital warts from HPV, molluscum contagiosum, and, not uncommonly, anogenital malignancies.7,8

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (CARP) is a disorder that occurs predominantly in young adults and teenagers, with cosmetically displeasing brown scaling macules that may coalesce to form patches or plaques affecting the neck, chest, back, and axillae. It is often mistaken for tinea versicolor.9 In this case, the eruption on the chest closely resembled CARP, but a diagnosis of CARP would not have explained the genital lesions.

Confirm diagnosis with treponemal tests

Syphilis is often a clinical diagnosis with pathologic confirmation. Patients suspected of having syphilis should be screened with nontreponemal tests, such as the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test or the RPR test, which become positive within 3 weeks of developing primary syphilis.

Diagnosis is confirmed with specific treponemal testing, such as with a fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption assay or the T pallidum particle agglutination test. HIV testing is recommended for all patients with syphilis.

Penicillin G is the mainstay of treatment

Proper selection of penicillin is paramount in the treatment of syphilis. Primary, secondary, and early latent syphilis are treated with an intramuscular injection of 2.4 million units of long-acting benzathine penicillin G. Patients with late latent or latent syphilis of unknown duration are treated with 3 doses of the same injection at weekly intervals, totaling 7.2 million units of benzathine penicillin G.10 Certain penicillin preparations (eg, combinations of benzathine penicillin and procaine penicillin) are not appropriate treatments because they do not provide adequate amounts of the antibiotic.

Watch for this reaction. Approximately 30% of patients following penicillin treatment for spirochete infection develop a Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction (JHR).11 JHR is characterized by an abrupt onset of fever, chills, myalgia, tachycardia, vasodilatation with flushing, exacerbated maculopapular skin rash, or mild hypotension. Care for JHR is generally supportive.

Our patient received an intramuscular injection of 2.4 million units of long-acting benzathine penicillin G. His skin eruption and condylomata lata lesions were completely resolved at follow-up 6 months later.

As recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,10 our patient’s RPR titers were repeated at 6 months and again at 12 months to verify a four-fold decline, indicating successful treatment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Anne Bartels, MD, General Medicine, Naval Hospital Camp Lejeune, 100 Brewster Blvd., Camp Lejeune, NC 28547; [email protected].

1. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Secondary syphilis. In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier; 2011:348-350.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Syphilis—CDC Fact Sheet. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/stdfact-syphilis.htm. Accessed May 31, 2017.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Syphilis. November 17, 2015. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats14/syphilis.htm. Accessed March 30, 2017.

4. Karnes JB, Usatine RP. Management of external genital warts. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90:312-318.

5. DuVivier A. Disorders of the sebaceous, sweat and apocrine glands. In: DuVivier A. Atlas of Clinical Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier; 2013:326-330.

6. Mabey D, Peeling RW. Lymphogranuloma venereum. Sex Transm Infect. 2002;78:90-92.

7. Altman K, Vanness E, Westergaard RP. Cutaneous manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus: a clinical update. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2015;17:464.

8. Maurer TA. Dermatologic manifestations of HIV infection. Top HIV Med. 2005;13:149-154.

9. Hudacek KD, Haque MS, Hochberg AL, et al. An unusual variant of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis masquerading as tinea versicolor. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:505-508.

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2010. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2010/STD-Treatment-2010-RR5912.pdf#. Accessed June 8, 2017.

11. Yang CJ, Lee NY, Lin YH, et al. Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction after penicillin therapy among patients with syphilis in the era of the hiv infection epidemic: incidence and risk factors. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:976-979.

1. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Secondary syphilis. In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier; 2011:348-350.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Syphilis—CDC Fact Sheet. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/stdfact-syphilis.htm. Accessed May 31, 2017.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Syphilis. November 17, 2015. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats14/syphilis.htm. Accessed March 30, 2017.

4. Karnes JB, Usatine RP. Management of external genital warts. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90:312-318.

5. DuVivier A. Disorders of the sebaceous, sweat and apocrine glands. In: DuVivier A. Atlas of Clinical Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier; 2013:326-330.

6. Mabey D, Peeling RW. Lymphogranuloma venereum. Sex Transm Infect. 2002;78:90-92.

7. Altman K, Vanness E, Westergaard RP. Cutaneous manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus: a clinical update. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2015;17:464.

8. Maurer TA. Dermatologic manifestations of HIV infection. Top HIV Med. 2005;13:149-154.

9. Hudacek KD, Haque MS, Hochberg AL, et al. An unusual variant of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis masquerading as tinea versicolor. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:505-508.

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2010. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2010/STD-Treatment-2010-RR5912.pdf#. Accessed June 8, 2017.

11. Yang CJ, Lee NY, Lin YH, et al. Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction after penicillin therapy among patients with syphilis in the era of the hiv infection epidemic: incidence and risk factors. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:976-979.