User login

Choosing Wisely in the COVID-19 Era: Preventing Harm to Healthcare Workers

With more than 3 million people diagnosed and more than 200,000 deaths worldwide at the time this article was written, coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) poses an unprecedented challenge to the public and to our healthcare system.1 The United States has surpassed every other country in the total number of COVID-19 cases. Hospitals in hotspots are operating beyond capacity, while others prepare for a predicted surge of patients suffering from COVID-19. Now more than ever, clinicians need to prioritize limited time and resources wisely in this rapidly changing environment. Our most precious limited resource, healthcare workers (HCWs), bravely care for patients while trying to avoid acquiring the infection. With each test and treatment, clinicians must carefully consider harms and benefits, including exposing themselves and other HCWs to SARS-CoV-2, the virus causing this disease.

Delivering any healthcare service in which the potential harm exceeds benefit represents one form of overuse. In the era of COVID-19, the harmful consequences of overuse go beyond the patient to the healthcare team. For example, unnecessary chest computed tomography (CT) to help diagnose COVID-19 comes with the usual risks to the patient including radiation, but it may also reveal a suspicious nodule. That incidental finding can lead to downstream consequences, such as more imaging, blood work, and biopsy. In the current pandemic, however, that CT comes with more than just the usual risk. The initial unnecessary chest CT can risk exposing the transporter, the staff in the hallways and elevator en route, the radiology staff operating the CT scanner, and the maintenance staff who must clean the room and scanner afterward. Potential downstream harms to staff include exposure of the pulmonary and interventional radiology consultants, as well as the staff who perform repeat imaging after the biopsy. Evaluation of the nodule potentially prolongs the patient’s stay and exposes more staff. Clinicians must weigh the benefits and harms of each test and treatment carefully with consideration of both the patient and the staff involved. Moreover, it may turn out that the patient and staff without symptoms of COVID-19 may pose the most risk to one another.

RECOMMENDATIONS

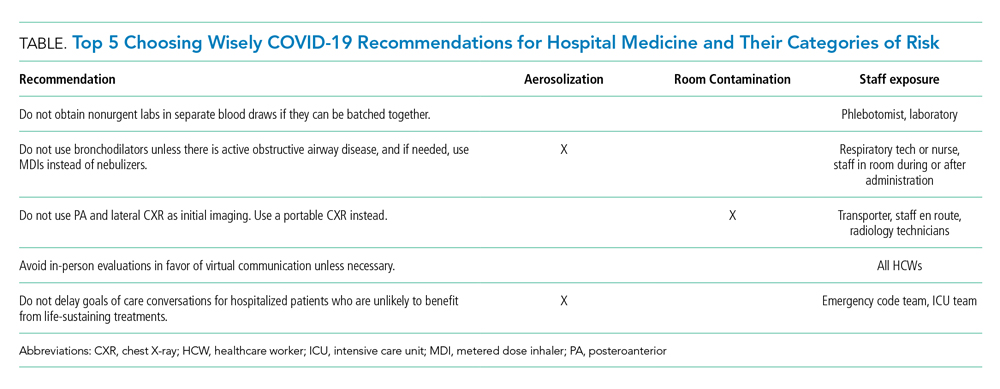

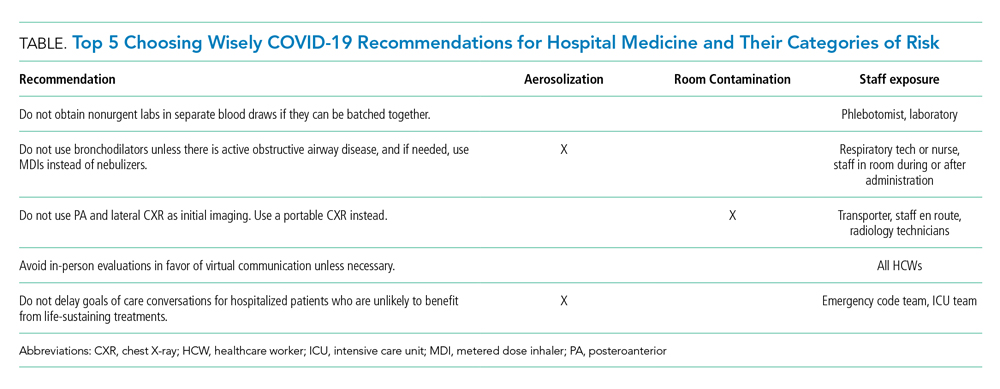

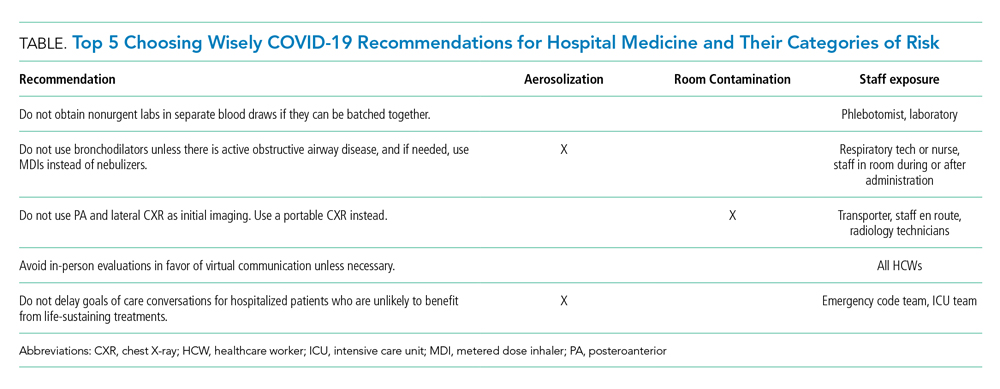

Choosing Wisely® partnered with patients and clinician societies to develop a Top 5 recommendations list for eliminating unnecessary testing and treatment. Our multi-institutional group from the High Value Practice Academic Alliance proposed this Top 5 list of overuse practices in hospital medicine that can lead to harm of both patients and HCWs in the COVID-19 era (Table). The following recommendations apply to all patients with unsuspected, suspected, or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in the hospital setting.

- Do not obtain nonurgent labs in separate blood draws if they can be batched together.

This recommendation expands on the original Society of Hospital Medicine Choosing Wisely recommendation: Don’t perform repetitive complete blood count and chemistry testing in the face of clinical and lab stability.2 Aside from patient harms such as pain and hospital-acquired anemia, the risk of exposure to HCWs who perform phlebotomy (phlebotomists, nurses, and other clinicians), as well as staff who transport, handle, and process the bloodwork in the lab, must be minimized. Most prior interventions to eliminate unnecessary bloodwork focused on the number of lab tests,3 but some also aimed to batch nonurgent labs together to effectively reduce unnecessary needlesticks (“think twice, stick once”).4 This concept can be brought into this pandemic to provide safe and appropriate care for both patients and HCWs.

- Do not use bronchodilators unless there is active obstructive airway disease, and if needed, use metered dose inhalers instead of nebulizers.

We do not recommend using bronchodilators to treat COVID-19 symptoms unless patients develop acute bronchospastic symptoms of their underlying obstructive airway disease.5 When needed, use metered dose inhalers (MDIs),6 if available, instead of nebulizers because the latter potentiates aerosolization that could lead to higher risk of spreading the infection. The risk extends to respiratory technicians and nurses who administer the nebulizer, as well as other HCWs who enter the room during or after administration. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) considers nebulized bronchodilator therapy a “high-risk” exposure for HCWs not wearing the proper personal protectvie equipment.7 Moreover, MDI therapy produces equivalent outcomes to nebulized treatments for patients who are not critically ill.6 Unfortunately, the supply of MDIs during this crisis has not kept up with the increased demand.8

There are no clear guidelines for reuse of MDIs in COVID-19; however, options include labeling patients’ MDIs to use for hospitalization and discharge or labeling an MDI for use during hospitalization and then disinfecting for reuse. For safety reasons, MDIs of COVID-19 patients should be reused only for other patients with COVID-19.8

- Do not use posteroanterior and lateral chest X-ray as initial imaging. Use a portable chest X-ray instead.

The CDC does not currently recommend diagnosing COVID-19 by chest X-ray (CXR).7 When used appropriately, CXR can provide information to support a COVID-19 diagnosis and rule out other etiologies that cause respiratory symptoms.9 Posteroanterior (PA) and lateral CXR are more sensitive than portable CXR for detecting pleural effusions, and lateral CXR is needed to examine structures along the axis of the body. Portable CXR also may cause the heart to appear magnified and the mediastinum widened, the diaphragm to appear higher, and vascular shadows to be obscured.10 The improved ability to detect these subtle differences should be weighed against the increased risk to HCWs required to perform PA and lateral CXR. A portable CXR exposes a relatively smaller number of staff who come to the bedside versus the larger number of people exposed in transporting the patient out of the room and into the hallway, elevator, and the radiology suite for a PA and lateral CXR.

- Avoid in-person evaluations in favor of virtual communication unless necessary.

To minimize HCW exposure to COVID-19 and optimize infection control, the CDC recommends the use of telemedicine when possible.7 Telemedicine refers to the use of technology to support clinical care across some distance, which includes video visits and remote clinical monitoring. At the time of writing, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services had waived the rural site of care requirement for Medicare beneficiaries, granted 49 Medicaid waivers to states to enhance flexibility, and (at least temporarily) added inpatient care to the list of reimbursed telemedicine services.11 Funding for expanded coverage under Medicare is included in the recent Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act.12 These federal changes open the door for commercial payers and state Medicaid programs to further boost telemedicine through reimbursement parity to in-person visits and other coverage policies. Hospitalists can ride this momentum and learn from ambulatory colleagues to harness the power of telemedicine and minimize unnecessary face-to-face interactions with patients who are suspected or confirmed to have COVID-19.13 Even if providers have to enter the patient’s room, telemedicine may still allow for large virtual family meetings despite strict visitor restrictions and physical distance with loved ones. If in-person visits are necessary, only one designated person should enter the patient’s room instead of the entire team.

- Do not delay goals of care conversations for hospitalized patients who are unlikely to benefit from life-sustaining treatments.

The COVID-19 pandemic amplifies the need for early goals of care discussions. Mortality rates range higher with acute respiratory distress syndrome from COVID-19, compared with other etiologies, and is associated with extended intensive care unit stays.14 The harms extend beyond the patient and families to our HCWs through psychological distress and heightened exposure from aerosolization during resuscitation. Advance care planning should center on the values and preferences of the patient. Rather than asking if the patient or family would want certain treatments, it is crucial for clinicians to be direct in making do-not-resuscitate recommendations if deemed futile care.15 This practice is well within legal confines and is distinct from withdrawal or withholding of life-sustaining resources.15

CONCLUSION

HCWs providing inpatient care during this pandemic remain among the highest risk for contracting the infection. As of April 9, 2020, nearly 9,300 HCWs in the United States have contracted COVID-19.16 One thing remains clear: If we want to protect our patients, we must start by protecting our HCWs. We must think critically to evaluate the potential harms to our extended healthcare teams and strive further to eliminate overuse from our care.

Acknowledgment

The authors represent members of the High Value Practice Academic Alliance. The High Value Practice Academic Alliance is a consortium of academic medical centers in the United States and Canada working to advance high-value healthcare through collaborative quality improvement, research, and education. Additional information is available at http://www.hvpaa.org.

1. World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019. Accessed May 3, 2020.

2. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2063.

3. Eaton KP, Levy K, Soong C, et al. Evidence-based guidelines to eliminate repetitive laboratory testing. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1833-1839. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.5152.

4. Wheeler D, Marcus P, Nguyen J, et al. Evaluation of a resident-led project to decrease phlebotomy rates in the hospital: think twice, stick once. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(5):708-710. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.0549.

5. Respiratory care committee of Chinese Thoracic Society. [Expert consensus on preventing nosocomial transmission during respiratory care for critically ill patients infected by 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia]. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2020;17(0):E020. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-0939.2020.0020.

6. Moriates C, Feldman L. Nebulized bronchodilators instead of metered-dose inhalers for obstructive pulmonary symptoms. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):691-693. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2386.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim US Guidance for Risk Assessment and Public Health Management of Healthcare Personnel with Potential Exposure in a Healthcare Setting to Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). April 15, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-risk-assesment-hcp.html. Accessed May 3, 2020.

8. Institute for Safe Medication Practices. Revisiting the Need for MDI Common Canister Protocols During the COVID-19 Pandemic. March 26, 2020. https://ismp.org/resources/revisiting-need-mdi-common-canister-protocols-during-covid-19-pandemic. Accessed May 3, 2020.

9. American College of Radiology. ACR Recommendations for the Use of Chest Radiography and Computed Tomography (CT) for Suspected COVID-19 Infection. March 11, 2020. https://www.acr.org/Advocacy-and-Economics/ACR-Position-Statements/Recommendations-for-Chest-Radiography-and-CT-for-Suspected-COVID19-Infection. Accessed May 3, 2020.

10. Bell DJ, Jones J, et al. https://radiopaedia.org/articles/chest-radiograph?lang=us. Accessed April 4, 2020.

11. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. List of Telehealth Services. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-General-Information/Telehealth/Telehealth-Codes. Accessed April 17, 2020.

12. Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2020, HR 6074, 116th Cong (2020). Accessed May 3, 2020. https://congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/6074/.

13. Doshi A, Platt Y, Dressen JR, Mathews Benji, Siy JC. Keep calm and log on: telemedicine for COVID-19 pandemic response. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(5):302-304. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3419.

14. Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1574‐1581. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5394.

15. Curtis JR, Kross EK, Stapleton RD. The importance of addressing advance care planning and decisions about do-not-resuscitate orders during novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) [online first]. JAMA. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.4894.

16. CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Characteristics of health care personnel with COVID-19 - United States, February 12-April 9, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(15):477-481.

With more than 3 million people diagnosed and more than 200,000 deaths worldwide at the time this article was written, coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) poses an unprecedented challenge to the public and to our healthcare system.1 The United States has surpassed every other country in the total number of COVID-19 cases. Hospitals in hotspots are operating beyond capacity, while others prepare for a predicted surge of patients suffering from COVID-19. Now more than ever, clinicians need to prioritize limited time and resources wisely in this rapidly changing environment. Our most precious limited resource, healthcare workers (HCWs), bravely care for patients while trying to avoid acquiring the infection. With each test and treatment, clinicians must carefully consider harms and benefits, including exposing themselves and other HCWs to SARS-CoV-2, the virus causing this disease.

Delivering any healthcare service in which the potential harm exceeds benefit represents one form of overuse. In the era of COVID-19, the harmful consequences of overuse go beyond the patient to the healthcare team. For example, unnecessary chest computed tomography (CT) to help diagnose COVID-19 comes with the usual risks to the patient including radiation, but it may also reveal a suspicious nodule. That incidental finding can lead to downstream consequences, such as more imaging, blood work, and biopsy. In the current pandemic, however, that CT comes with more than just the usual risk. The initial unnecessary chest CT can risk exposing the transporter, the staff in the hallways and elevator en route, the radiology staff operating the CT scanner, and the maintenance staff who must clean the room and scanner afterward. Potential downstream harms to staff include exposure of the pulmonary and interventional radiology consultants, as well as the staff who perform repeat imaging after the biopsy. Evaluation of the nodule potentially prolongs the patient’s stay and exposes more staff. Clinicians must weigh the benefits and harms of each test and treatment carefully with consideration of both the patient and the staff involved. Moreover, it may turn out that the patient and staff without symptoms of COVID-19 may pose the most risk to one another.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Choosing Wisely® partnered with patients and clinician societies to develop a Top 5 recommendations list for eliminating unnecessary testing and treatment. Our multi-institutional group from the High Value Practice Academic Alliance proposed this Top 5 list of overuse practices in hospital medicine that can lead to harm of both patients and HCWs in the COVID-19 era (Table). The following recommendations apply to all patients with unsuspected, suspected, or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in the hospital setting.

- Do not obtain nonurgent labs in separate blood draws if they can be batched together.

This recommendation expands on the original Society of Hospital Medicine Choosing Wisely recommendation: Don’t perform repetitive complete blood count and chemistry testing in the face of clinical and lab stability.2 Aside from patient harms such as pain and hospital-acquired anemia, the risk of exposure to HCWs who perform phlebotomy (phlebotomists, nurses, and other clinicians), as well as staff who transport, handle, and process the bloodwork in the lab, must be minimized. Most prior interventions to eliminate unnecessary bloodwork focused on the number of lab tests,3 but some also aimed to batch nonurgent labs together to effectively reduce unnecessary needlesticks (“think twice, stick once”).4 This concept can be brought into this pandemic to provide safe and appropriate care for both patients and HCWs.

- Do not use bronchodilators unless there is active obstructive airway disease, and if needed, use metered dose inhalers instead of nebulizers.

We do not recommend using bronchodilators to treat COVID-19 symptoms unless patients develop acute bronchospastic symptoms of their underlying obstructive airway disease.5 When needed, use metered dose inhalers (MDIs),6 if available, instead of nebulizers because the latter potentiates aerosolization that could lead to higher risk of spreading the infection. The risk extends to respiratory technicians and nurses who administer the nebulizer, as well as other HCWs who enter the room during or after administration. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) considers nebulized bronchodilator therapy a “high-risk” exposure for HCWs not wearing the proper personal protectvie equipment.7 Moreover, MDI therapy produces equivalent outcomes to nebulized treatments for patients who are not critically ill.6 Unfortunately, the supply of MDIs during this crisis has not kept up with the increased demand.8

There are no clear guidelines for reuse of MDIs in COVID-19; however, options include labeling patients’ MDIs to use for hospitalization and discharge or labeling an MDI for use during hospitalization and then disinfecting for reuse. For safety reasons, MDIs of COVID-19 patients should be reused only for other patients with COVID-19.8

- Do not use posteroanterior and lateral chest X-ray as initial imaging. Use a portable chest X-ray instead.

The CDC does not currently recommend diagnosing COVID-19 by chest X-ray (CXR).7 When used appropriately, CXR can provide information to support a COVID-19 diagnosis and rule out other etiologies that cause respiratory symptoms.9 Posteroanterior (PA) and lateral CXR are more sensitive than portable CXR for detecting pleural effusions, and lateral CXR is needed to examine structures along the axis of the body. Portable CXR also may cause the heart to appear magnified and the mediastinum widened, the diaphragm to appear higher, and vascular shadows to be obscured.10 The improved ability to detect these subtle differences should be weighed against the increased risk to HCWs required to perform PA and lateral CXR. A portable CXR exposes a relatively smaller number of staff who come to the bedside versus the larger number of people exposed in transporting the patient out of the room and into the hallway, elevator, and the radiology suite for a PA and lateral CXR.

- Avoid in-person evaluations in favor of virtual communication unless necessary.

To minimize HCW exposure to COVID-19 and optimize infection control, the CDC recommends the use of telemedicine when possible.7 Telemedicine refers to the use of technology to support clinical care across some distance, which includes video visits and remote clinical monitoring. At the time of writing, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services had waived the rural site of care requirement for Medicare beneficiaries, granted 49 Medicaid waivers to states to enhance flexibility, and (at least temporarily) added inpatient care to the list of reimbursed telemedicine services.11 Funding for expanded coverage under Medicare is included in the recent Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act.12 These federal changes open the door for commercial payers and state Medicaid programs to further boost telemedicine through reimbursement parity to in-person visits and other coverage policies. Hospitalists can ride this momentum and learn from ambulatory colleagues to harness the power of telemedicine and minimize unnecessary face-to-face interactions with patients who are suspected or confirmed to have COVID-19.13 Even if providers have to enter the patient’s room, telemedicine may still allow for large virtual family meetings despite strict visitor restrictions and physical distance with loved ones. If in-person visits are necessary, only one designated person should enter the patient’s room instead of the entire team.

- Do not delay goals of care conversations for hospitalized patients who are unlikely to benefit from life-sustaining treatments.

The COVID-19 pandemic amplifies the need for early goals of care discussions. Mortality rates range higher with acute respiratory distress syndrome from COVID-19, compared with other etiologies, and is associated with extended intensive care unit stays.14 The harms extend beyond the patient and families to our HCWs through psychological distress and heightened exposure from aerosolization during resuscitation. Advance care planning should center on the values and preferences of the patient. Rather than asking if the patient or family would want certain treatments, it is crucial for clinicians to be direct in making do-not-resuscitate recommendations if deemed futile care.15 This practice is well within legal confines and is distinct from withdrawal or withholding of life-sustaining resources.15

CONCLUSION

HCWs providing inpatient care during this pandemic remain among the highest risk for contracting the infection. As of April 9, 2020, nearly 9,300 HCWs in the United States have contracted COVID-19.16 One thing remains clear: If we want to protect our patients, we must start by protecting our HCWs. We must think critically to evaluate the potential harms to our extended healthcare teams and strive further to eliminate overuse from our care.

Acknowledgment

The authors represent members of the High Value Practice Academic Alliance. The High Value Practice Academic Alliance is a consortium of academic medical centers in the United States and Canada working to advance high-value healthcare through collaborative quality improvement, research, and education. Additional information is available at http://www.hvpaa.org.

With more than 3 million people diagnosed and more than 200,000 deaths worldwide at the time this article was written, coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) poses an unprecedented challenge to the public and to our healthcare system.1 The United States has surpassed every other country in the total number of COVID-19 cases. Hospitals in hotspots are operating beyond capacity, while others prepare for a predicted surge of patients suffering from COVID-19. Now more than ever, clinicians need to prioritize limited time and resources wisely in this rapidly changing environment. Our most precious limited resource, healthcare workers (HCWs), bravely care for patients while trying to avoid acquiring the infection. With each test and treatment, clinicians must carefully consider harms and benefits, including exposing themselves and other HCWs to SARS-CoV-2, the virus causing this disease.

Delivering any healthcare service in which the potential harm exceeds benefit represents one form of overuse. In the era of COVID-19, the harmful consequences of overuse go beyond the patient to the healthcare team. For example, unnecessary chest computed tomography (CT) to help diagnose COVID-19 comes with the usual risks to the patient including radiation, but it may also reveal a suspicious nodule. That incidental finding can lead to downstream consequences, such as more imaging, blood work, and biopsy. In the current pandemic, however, that CT comes with more than just the usual risk. The initial unnecessary chest CT can risk exposing the transporter, the staff in the hallways and elevator en route, the radiology staff operating the CT scanner, and the maintenance staff who must clean the room and scanner afterward. Potential downstream harms to staff include exposure of the pulmonary and interventional radiology consultants, as well as the staff who perform repeat imaging after the biopsy. Evaluation of the nodule potentially prolongs the patient’s stay and exposes more staff. Clinicians must weigh the benefits and harms of each test and treatment carefully with consideration of both the patient and the staff involved. Moreover, it may turn out that the patient and staff without symptoms of COVID-19 may pose the most risk to one another.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Choosing Wisely® partnered with patients and clinician societies to develop a Top 5 recommendations list for eliminating unnecessary testing and treatment. Our multi-institutional group from the High Value Practice Academic Alliance proposed this Top 5 list of overuse practices in hospital medicine that can lead to harm of both patients and HCWs in the COVID-19 era (Table). The following recommendations apply to all patients with unsuspected, suspected, or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in the hospital setting.

- Do not obtain nonurgent labs in separate blood draws if they can be batched together.

This recommendation expands on the original Society of Hospital Medicine Choosing Wisely recommendation: Don’t perform repetitive complete blood count and chemistry testing in the face of clinical and lab stability.2 Aside from patient harms such as pain and hospital-acquired anemia, the risk of exposure to HCWs who perform phlebotomy (phlebotomists, nurses, and other clinicians), as well as staff who transport, handle, and process the bloodwork in the lab, must be minimized. Most prior interventions to eliminate unnecessary bloodwork focused on the number of lab tests,3 but some also aimed to batch nonurgent labs together to effectively reduce unnecessary needlesticks (“think twice, stick once”).4 This concept can be brought into this pandemic to provide safe and appropriate care for both patients and HCWs.

- Do not use bronchodilators unless there is active obstructive airway disease, and if needed, use metered dose inhalers instead of nebulizers.

We do not recommend using bronchodilators to treat COVID-19 symptoms unless patients develop acute bronchospastic symptoms of their underlying obstructive airway disease.5 When needed, use metered dose inhalers (MDIs),6 if available, instead of nebulizers because the latter potentiates aerosolization that could lead to higher risk of spreading the infection. The risk extends to respiratory technicians and nurses who administer the nebulizer, as well as other HCWs who enter the room during or after administration. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) considers nebulized bronchodilator therapy a “high-risk” exposure for HCWs not wearing the proper personal protectvie equipment.7 Moreover, MDI therapy produces equivalent outcomes to nebulized treatments for patients who are not critically ill.6 Unfortunately, the supply of MDIs during this crisis has not kept up with the increased demand.8

There are no clear guidelines for reuse of MDIs in COVID-19; however, options include labeling patients’ MDIs to use for hospitalization and discharge or labeling an MDI for use during hospitalization and then disinfecting for reuse. For safety reasons, MDIs of COVID-19 patients should be reused only for other patients with COVID-19.8

- Do not use posteroanterior and lateral chest X-ray as initial imaging. Use a portable chest X-ray instead.

The CDC does not currently recommend diagnosing COVID-19 by chest X-ray (CXR).7 When used appropriately, CXR can provide information to support a COVID-19 diagnosis and rule out other etiologies that cause respiratory symptoms.9 Posteroanterior (PA) and lateral CXR are more sensitive than portable CXR for detecting pleural effusions, and lateral CXR is needed to examine structures along the axis of the body. Portable CXR also may cause the heart to appear magnified and the mediastinum widened, the diaphragm to appear higher, and vascular shadows to be obscured.10 The improved ability to detect these subtle differences should be weighed against the increased risk to HCWs required to perform PA and lateral CXR. A portable CXR exposes a relatively smaller number of staff who come to the bedside versus the larger number of people exposed in transporting the patient out of the room and into the hallway, elevator, and the radiology suite for a PA and lateral CXR.

- Avoid in-person evaluations in favor of virtual communication unless necessary.

To minimize HCW exposure to COVID-19 and optimize infection control, the CDC recommends the use of telemedicine when possible.7 Telemedicine refers to the use of technology to support clinical care across some distance, which includes video visits and remote clinical monitoring. At the time of writing, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services had waived the rural site of care requirement for Medicare beneficiaries, granted 49 Medicaid waivers to states to enhance flexibility, and (at least temporarily) added inpatient care to the list of reimbursed telemedicine services.11 Funding for expanded coverage under Medicare is included in the recent Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act.12 These federal changes open the door for commercial payers and state Medicaid programs to further boost telemedicine through reimbursement parity to in-person visits and other coverage policies. Hospitalists can ride this momentum and learn from ambulatory colleagues to harness the power of telemedicine and minimize unnecessary face-to-face interactions with patients who are suspected or confirmed to have COVID-19.13 Even if providers have to enter the patient’s room, telemedicine may still allow for large virtual family meetings despite strict visitor restrictions and physical distance with loved ones. If in-person visits are necessary, only one designated person should enter the patient’s room instead of the entire team.

- Do not delay goals of care conversations for hospitalized patients who are unlikely to benefit from life-sustaining treatments.

The COVID-19 pandemic amplifies the need for early goals of care discussions. Mortality rates range higher with acute respiratory distress syndrome from COVID-19, compared with other etiologies, and is associated with extended intensive care unit stays.14 The harms extend beyond the patient and families to our HCWs through psychological distress and heightened exposure from aerosolization during resuscitation. Advance care planning should center on the values and preferences of the patient. Rather than asking if the patient or family would want certain treatments, it is crucial for clinicians to be direct in making do-not-resuscitate recommendations if deemed futile care.15 This practice is well within legal confines and is distinct from withdrawal or withholding of life-sustaining resources.15

CONCLUSION

HCWs providing inpatient care during this pandemic remain among the highest risk for contracting the infection. As of April 9, 2020, nearly 9,300 HCWs in the United States have contracted COVID-19.16 One thing remains clear: If we want to protect our patients, we must start by protecting our HCWs. We must think critically to evaluate the potential harms to our extended healthcare teams and strive further to eliminate overuse from our care.

Acknowledgment

The authors represent members of the High Value Practice Academic Alliance. The High Value Practice Academic Alliance is a consortium of academic medical centers in the United States and Canada working to advance high-value healthcare through collaborative quality improvement, research, and education. Additional information is available at http://www.hvpaa.org.

1. World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019. Accessed May 3, 2020.

2. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2063.

3. Eaton KP, Levy K, Soong C, et al. Evidence-based guidelines to eliminate repetitive laboratory testing. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1833-1839. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.5152.

4. Wheeler D, Marcus P, Nguyen J, et al. Evaluation of a resident-led project to decrease phlebotomy rates in the hospital: think twice, stick once. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(5):708-710. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.0549.

5. Respiratory care committee of Chinese Thoracic Society. [Expert consensus on preventing nosocomial transmission during respiratory care for critically ill patients infected by 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia]. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2020;17(0):E020. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-0939.2020.0020.

6. Moriates C, Feldman L. Nebulized bronchodilators instead of metered-dose inhalers for obstructive pulmonary symptoms. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):691-693. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2386.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim US Guidance for Risk Assessment and Public Health Management of Healthcare Personnel with Potential Exposure in a Healthcare Setting to Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). April 15, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-risk-assesment-hcp.html. Accessed May 3, 2020.

8. Institute for Safe Medication Practices. Revisiting the Need for MDI Common Canister Protocols During the COVID-19 Pandemic. March 26, 2020. https://ismp.org/resources/revisiting-need-mdi-common-canister-protocols-during-covid-19-pandemic. Accessed May 3, 2020.

9. American College of Radiology. ACR Recommendations for the Use of Chest Radiography and Computed Tomography (CT) for Suspected COVID-19 Infection. March 11, 2020. https://www.acr.org/Advocacy-and-Economics/ACR-Position-Statements/Recommendations-for-Chest-Radiography-and-CT-for-Suspected-COVID19-Infection. Accessed May 3, 2020.

10. Bell DJ, Jones J, et al. https://radiopaedia.org/articles/chest-radiograph?lang=us. Accessed April 4, 2020.

11. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. List of Telehealth Services. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-General-Information/Telehealth/Telehealth-Codes. Accessed April 17, 2020.

12. Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2020, HR 6074, 116th Cong (2020). Accessed May 3, 2020. https://congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/6074/.

13. Doshi A, Platt Y, Dressen JR, Mathews Benji, Siy JC. Keep calm and log on: telemedicine for COVID-19 pandemic response. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(5):302-304. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3419.

14. Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1574‐1581. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5394.

15. Curtis JR, Kross EK, Stapleton RD. The importance of addressing advance care planning and decisions about do-not-resuscitate orders during novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) [online first]. JAMA. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.4894.

16. CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Characteristics of health care personnel with COVID-19 - United States, February 12-April 9, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(15):477-481.

1. World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019. Accessed May 3, 2020.

2. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2063.

3. Eaton KP, Levy K, Soong C, et al. Evidence-based guidelines to eliminate repetitive laboratory testing. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1833-1839. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.5152.

4. Wheeler D, Marcus P, Nguyen J, et al. Evaluation of a resident-led project to decrease phlebotomy rates in the hospital: think twice, stick once. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(5):708-710. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.0549.

5. Respiratory care committee of Chinese Thoracic Society. [Expert consensus on preventing nosocomial transmission during respiratory care for critically ill patients infected by 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia]. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2020;17(0):E020. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-0939.2020.0020.

6. Moriates C, Feldman L. Nebulized bronchodilators instead of metered-dose inhalers for obstructive pulmonary symptoms. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):691-693. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2386.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim US Guidance for Risk Assessment and Public Health Management of Healthcare Personnel with Potential Exposure in a Healthcare Setting to Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). April 15, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-risk-assesment-hcp.html. Accessed May 3, 2020.

8. Institute for Safe Medication Practices. Revisiting the Need for MDI Common Canister Protocols During the COVID-19 Pandemic. March 26, 2020. https://ismp.org/resources/revisiting-need-mdi-common-canister-protocols-during-covid-19-pandemic. Accessed May 3, 2020.

9. American College of Radiology. ACR Recommendations for the Use of Chest Radiography and Computed Tomography (CT) for Suspected COVID-19 Infection. March 11, 2020. https://www.acr.org/Advocacy-and-Economics/ACR-Position-Statements/Recommendations-for-Chest-Radiography-and-CT-for-Suspected-COVID19-Infection. Accessed May 3, 2020.

10. Bell DJ, Jones J, et al. https://radiopaedia.org/articles/chest-radiograph?lang=us. Accessed April 4, 2020.

11. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. List of Telehealth Services. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-General-Information/Telehealth/Telehealth-Codes. Accessed April 17, 2020.

12. Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2020, HR 6074, 116th Cong (2020). Accessed May 3, 2020. https://congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/6074/.

13. Doshi A, Platt Y, Dressen JR, Mathews Benji, Siy JC. Keep calm and log on: telemedicine for COVID-19 pandemic response. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(5):302-304. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3419.

14. Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1574‐1581. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5394.

15. Curtis JR, Kross EK, Stapleton RD. The importance of addressing advance care planning and decisions about do-not-resuscitate orders during novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) [online first]. JAMA. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.4894.

16. CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Characteristics of health care personnel with COVID-19 - United States, February 12-April 9, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(15):477-481.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Contemporary Rates of Preoperative Cardiac Testing Prior to Inpatient Hip Fracture Surgery

Hip fracture is a common reason for unexpected, urgent inpatient surgery in older patients. In 2005, the incidence of hip fracture was 369.0 and 793.5 per 100,000 in men and women respectively.1 These numbers declined over the preceding decade, potentially as a result of bisphosphonate use. Age- and risk-adjusted 30-day mortality rates for men and women in 2005 were approximately 10% and 5%, respectively.

Evidence suggests that timely surgical repair of hip fractures improves outcomes, although the optimal timing is controversial. Guidelines from the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma from 2015 recommend surgical intervention within 48 hours for geriatric hip fracures.2 A 2008 systematic review found that operative delay beyond 48 hours was associated with a 41% increase in 30-day all-cause mortality and a 32% increase in one-year all-cause mortality.3 Recent evidence suggests that the rate of complications begins to increase with delays beyond 24 hours.4

There has been a focus over the past decade on overuse of preoperative testing for low- and intermediate-risk surgeries.5-7 Beginning in 2012, the American Board of Internal Medicine initiated the Choosing Wisely® campaign in which numerous societies issued recommendations on reducing utilization of various diagnostic tests, a number of which have focused on preoperative tests. Two groups—the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) and the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE)— issued specific recommendations on preoperative cardiac testing.8 In February 2013, the ASE recommended avoiding preoperative echocardiograms in patients without a history or symptoms of heart disease. In October 2013, the ASA recommended against transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE), transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE), or stress testing for low- or intermediate-risk noncardiac surgery for patients with stable cardiac disease.

Finally, in 2014, the American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) issued updated perioperative guidelines for patients undergoing noncardiac surgeries.9 They recommended preoperative stress testing only in a small subset of cases (patients with an elevated perioperative risk of major adverse cardiac event, a poor or unknown functional capacity, or those in whom stress testing would impact perioperative care).

Given the high cost of preoperative cardiac testing, the potential for delays in care that can adversely impact outcomes, and the recent recommendations, we sought to characterize the rates of inpatient preoperative cardiac testing prior to hip fracture surgery in recent years and to see whether recent recommendations to curb use of these tests were temporally associated with changing rates.

METHODS

Overview

We utilized two datasets—the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) State Inpatient Databases (SID) and the American Hospital Association (AHA) Annual Survey—to characterize preoperative cardiac testing. SID data from Maryland, New Jersey, and Washington State from 2011 through September 2015 were used (the ICD coding system changed from ICD9 to ICD10 on October 1). This was combined with AHA data for these years. We included all hospitalizations with a primary ICD9 procedure code for hip fracture repair—78.55, 78.65, 79.05, 79.15, 79.25, 79.35, 79.45, 79.55, 79.65, 79.75, 79.85, and 79.95. We excluded all observations that involved an interhospital transfer. This study was exempt from institutional review board approval.

Measurement and Outcomes

We summarized demographic data for the hospitalizations that met the inclusion criteria as well as the associated hospitals. The primary outcome was the percentage of patients undergoing TTE, stress test, and cardiac catheterization during a hospitalization with a primary procedure code of hip fracture repair. Random effects logistic regression models for each type of diagnostic test were developed to determine the factors that might impact test utilization. In addition to running each test as a separate model, we also performed an analysis in which the outcome was performance of any of these three cardiac tests. Random effects were used to account for clustering of testing within hospitals. Variables included time (3-month intervals), state, age (continuous variable), gender, length of stay, payer (Medicare/Medicaid/private insurance/self-pay/other), hospital teaching status (major teaching/minor teaching/nonteaching), hospital size according to number of beds (continuous variable), and mortality score. Major teaching hospitals are defined as members of the Council of Teaching Hospitals. Minor teaching hospitals are defined as (1) those with one or more postgraduate training programs recognized by the American Council on Graduate Medical Education, (2) those with a medical school affiliation reported to the American Medical Association, or (3) those with an internship or residency approved by the American Osteopathic Association.

The SID has a specific binary indicator variable for each of the three diagnostic tests we evaluated. The use of the diagnostic test is evaluated through both UB-92 revenue codes and ICD9 procedure codes, with the presence of either leading to the indicator variable being positive.10 Finally, we performed a sensitivity analysis to evaluate the significance of changing utilization trends by interrupted time series analysis. A level of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance. Analyses were done in STATA 15 (College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

The dataset included 75,144 hospitalizations with a primary procedure code of hip fracture over the study period (Table). The number of hospitalizations per year was fairly consistent over the study period in each state, although there were fewer hospitalizations for 2015 as this included only January through September. The mean age was 72.8 years, and 67% were female. The primary payer was Medicare for 71.7% of hospitalizations. Hospitalizations occurred at 181 hospitals, the plurality of which (42.9%) were minor teaching hospitals. The proportions of hospitalizations that included a TTE, stress test, and cardiac catheterization were 12.6%, 1.1%, and 0.5%, respectively. Overall, 13.5% of patients underwent any cardiac testing.

There was a statistically significantly lower rate of stress tests (odds ratio [OR], 0.32; 95% CI, 0.19-0.54) and cardiac catheterizations (OR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.27-0.79) in Washington than in Maryland and New Jersey. Female gender was associated with significantly lower adjusted ORs for stress tests (OR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.63-0.86) and cardiac catheterizations (OR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.59-0.91), and increasing age was associated with higher adjusted ORs for each test (TTE, OR, 1.033; 95% CI, 1.031-1.035; stress tests, OR, 1.007; 95% CI, 1.001-1.013; cardiac catheterizations, OR, 1.011; 95% CI, 1.003-1.019). Private insurance was associated with a lower likelihood of stress tests (OR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.50-0.85) and cardiac catheterizations (OR, 0.67; 95% CI,0.46-0.98), and self-pay was associated with a lower likelihood of TTE (OR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.61-0.95) and stress test (OR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.21-0.90), all compared with Medicare.

Larger hospitals were associated with a greater likelihood of cardiac catheterizations (OR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.03-1.36) and a lower likelihood of TTE (OR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.82-0.96). An unweighted average of these tests between 2011 and October 2015 showed a modest increase in TTEs and a modest decrease in stress tests and cardiac catheterizations (Figure). A multivariable random effects regression for use of TTEs revealed a significantly increasing trend from 2011 to 2014 (OR, 1.04, P < .0001), but the decreasing trend for 2015 was not statistically significant when analyzed according to quarters or months (for which data from only New Jersey and Washington are available).

In the combined model with any cardiac testing as the outcome, the likelihood of testing was lower in Washington (OR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.31-0.995). Primary payer status of self-pay was associated with a lower likelihood of cardiac testing (OR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.58-0.90). Female gender was associated with a lower likelihood of testing (OR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.88-0.98), and high mortality score was associated with a higher likelihood of testing (OR, 1.030; 95% CI, 1.027-1.033). TTEs were the major driver of this model as these were the most heavily utilized test.

DISCUSSION

There has been limited research into how often preoperative cardiac testing occurs in the inpatient setting. Our aim was to study its prevalence prior to hip fracture surgery during a time period when multiple recommendations had been issued to limit its use. We found rates of ischemic testing (stress tests and cardiac catheterizations) to be appropriately, and perhaps surprisingly, low. Our results on ischemic testing rates are consistent with previous studies, which have focused on the outpatient setting where much of the preoperative workup for nonurgent surgeries occurs. The rate of TTEs was higher than in previous studies of the outpatient preoperative setting, although it is unclear what an optimal rate of TTEs is.

A recent study examining outpatient preoperative stress tests within the 30 days before cataract surgeries, knee arthroscopies, or shoulder arthroscopies found a rate of 2.1% for Medicare fee-for-service patients in 2009 with little regional variation.11 Another evaluation using 2009 Medicare claims data found rates of preoperative TTEs and stress tests to be 0.8% and 0.7%, respectively.12 They included TTEs and stress tests performed within 30 days of a low- or intermediate-risk surgery. A study analyzing the rate of preoperative TTEs between 2009 and 2014 found that rates varied from 2.0% to 3.4% for commercially insured patients aged 50-64 years and Medicare-advantage patients, respectively, in 2009.13 These rates decreased by 7.0% and 12.6% from 2009 to 2014. These studies, like ours, suggest that preoperative cardiac testing has not been a major source of wasteful spending. One explanation for the higher rate of TTEs we observed in the inpatient setting might be that primary care physicians in the outpatient setting are more likely to have historical cardiac testing results compared with physicians in a hospital.

We found that the rate of stress testing and cardiac catheterization in Washington was significantly lower than that in Maryland and New Jersey. This is consistent with a number of measures of healthcare utilization – total Medicare reimbursement in the last six months of life, mean number of hospital days in the last six months of life, and healthcare intensity index—for all of which Washington was below the national mean and Maryland and New Jersey were above it.14

Finally, we found evidence of a lower rate of preoperative stress tests and cardiac catheterizations for women despite controlling for age and mortality score. Of course, we did not control directly for cardiovascular comorbidities; as a result, there could be residual confounding. However, these results are consistent with previous findings of gender bias in both pharmacologic management of coronary artery disease (CAD)15 and diagnostic testing for suspected CAD.16

We focused on hospitalizations with a primary procedure code to surgically treat hip fracture. We are unable to tell if the cardiac testing of these patients had occurred before or after the procedure. However, we suspect that the vast majority were completed for preoperative evaluation. It is likely that a small subset were done to diagnose and manage cardiac complications that either accompanied the hip fracture or occurred postoperatively. Another limitation is that we cannot determine if a patient had one of these tests recently in the emergency department or as an outpatient.

We also chose to include only patients who actually had hip fracture surgery. It is possible that the testing rate is higher for all patients admitted for hip fracture and that some of these patients did not have surgery because of abnormal cardiac testing. However, we suspect that this is a very small fraction given the high degree of morbidity and mortality associated with untreated hip fracture.

CONCLUSION

We found a low rate of preoperative cardiac testing in patients hospitalized for hip fracture surgery both in the years before and after the issuance of recommendations intended to curb its use. Although it is reassuring that the volume of low-value testing is lower than we expected, these findings highlight the importance of targeting utilization improvement efforts toward low-value tests and procedures that are more heavily used, since further curbing the use of infrequently utilized tests and procedures will have only a modest impact on overall healthcare expenditure. Our findings highlight the necessity that professional organizations ensure that they focus on true areas of inappropriate utilization. These are the areas in which improvements will have a major impact on healthcare spending. Further research should aim to quantify unwarranted cardiac testing for other inpatient surgeries that are less urgent, as the urgency of hip fracture repair may be driving the relatively low utilization of inpatient cardiac testing.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This project was supported by the Johns Hopkins Hospitalist Scholars Fund and the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Biostatistics, Epidemiology and Data Management (BEAD) Core.

1. Brauer CA, Coca-Perraillon M, Cutler DM, Rosen A. Incidence and mortality of hip fractures in the United States. JAMA. 2009;302(14):1573-1579. PubMed

2. ACS TQIP - Best Practices in the Management of Orthopaedic Trauma. https://www.facs.org/~/media/files/quality programs/trauma/tqip/tqip bpgs in the management of orthopaedic traumafinal.ashx. Published 2015. Accessed July 13, 2018.

3. Shiga T, Wajima Z, Ohe Y. Is operative delay associated with increased mortality of hip fracture patients? Systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Can J Anesth. 2008;55(3):146-154. PubMed

4. Pincus D, Ravi B, Wasserstein D, et al. Association between wait time and 30-day mortality in adults undergoing hip fracture surgery. JAMA. 2017;318(20):1994. PubMed

5. Clair CM, Shah M, Diver EJ, et al. Adherence to evidence-based guidelines for preoperative testing in women undergoing gynecologic surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(3):694-700. PubMed

6. Chen CL, Lin GA, Bardach NS, et al. Preoperative medical testing in Medicare patients undergoing cataract surgery. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(16):1530-1538. PubMed

7. Benarroch-Gampel J, Sheffield KM, Duncan CB, et al. Preoperative laboratory testing in patients undergoing elective, low-risk ambulatory surgery. Ann Surg. 2012; 256(3):518-528. PubMed

8. Choosing Wisely - An Initiative of the ABIM Foundation. http://www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists. Accessed July 16, 2018.

9. Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA Guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. JACC. 2014;64(22):e278 LP-e333. PubMed

10. HCUP Methods Series - Development of Utilization Flags for Use with UB-92 Administrative Data; Report # 2006-04. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/methods/2006_4.pdf.

11. Kerr EA, Chen J, Sussman JB, Klamerus ML, Nallamothu BK. Stress testing before low-risk surgery - so many recommendations, so little overuse. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):645-647. PubMed

12. Schwartz AL, Landon BE, Elshaug AG, Chernew ME, McWilliams JM. Measuring low-value care in medicare. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(7):1067-1076. PubMed

13. Carter EA, Morin PE, Lind KD. Costs and trends in utilization of low-value services among older adults with commercial insurance or Medicare advantage. Med Care. 2017;55(11):931-939. PubMed

14. The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. http://www.dartmouthatlas.org. Accessed December 7, 2017.

15. Williams D, Bennett K, Feely J. Evidence for an age and gender bias in the secondary prevention of ischaemic heart disease in primary care. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;55(6):604-608. PubMed

16. Chang AM, Mumma B, Sease KL, Robey JL, Shofer FS, Hollander JE. Gender bias in cardiovascular testing persists after adjustment for presenting characteristics and cardiac risk. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(7):599-605. PubMed

Hip fracture is a common reason for unexpected, urgent inpatient surgery in older patients. In 2005, the incidence of hip fracture was 369.0 and 793.5 per 100,000 in men and women respectively.1 These numbers declined over the preceding decade, potentially as a result of bisphosphonate use. Age- and risk-adjusted 30-day mortality rates for men and women in 2005 were approximately 10% and 5%, respectively.

Evidence suggests that timely surgical repair of hip fractures improves outcomes, although the optimal timing is controversial. Guidelines from the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma from 2015 recommend surgical intervention within 48 hours for geriatric hip fracures.2 A 2008 systematic review found that operative delay beyond 48 hours was associated with a 41% increase in 30-day all-cause mortality and a 32% increase in one-year all-cause mortality.3 Recent evidence suggests that the rate of complications begins to increase with delays beyond 24 hours.4

There has been a focus over the past decade on overuse of preoperative testing for low- and intermediate-risk surgeries.5-7 Beginning in 2012, the American Board of Internal Medicine initiated the Choosing Wisely® campaign in which numerous societies issued recommendations on reducing utilization of various diagnostic tests, a number of which have focused on preoperative tests. Two groups—the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) and the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE)— issued specific recommendations on preoperative cardiac testing.8 In February 2013, the ASE recommended avoiding preoperative echocardiograms in patients without a history or symptoms of heart disease. In October 2013, the ASA recommended against transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE), transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE), or stress testing for low- or intermediate-risk noncardiac surgery for patients with stable cardiac disease.

Finally, in 2014, the American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) issued updated perioperative guidelines for patients undergoing noncardiac surgeries.9 They recommended preoperative stress testing only in a small subset of cases (patients with an elevated perioperative risk of major adverse cardiac event, a poor or unknown functional capacity, or those in whom stress testing would impact perioperative care).

Given the high cost of preoperative cardiac testing, the potential for delays in care that can adversely impact outcomes, and the recent recommendations, we sought to characterize the rates of inpatient preoperative cardiac testing prior to hip fracture surgery in recent years and to see whether recent recommendations to curb use of these tests were temporally associated with changing rates.

METHODS

Overview

We utilized two datasets—the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) State Inpatient Databases (SID) and the American Hospital Association (AHA) Annual Survey—to characterize preoperative cardiac testing. SID data from Maryland, New Jersey, and Washington State from 2011 through September 2015 were used (the ICD coding system changed from ICD9 to ICD10 on October 1). This was combined with AHA data for these years. We included all hospitalizations with a primary ICD9 procedure code for hip fracture repair—78.55, 78.65, 79.05, 79.15, 79.25, 79.35, 79.45, 79.55, 79.65, 79.75, 79.85, and 79.95. We excluded all observations that involved an interhospital transfer. This study was exempt from institutional review board approval.

Measurement and Outcomes

We summarized demographic data for the hospitalizations that met the inclusion criteria as well as the associated hospitals. The primary outcome was the percentage of patients undergoing TTE, stress test, and cardiac catheterization during a hospitalization with a primary procedure code of hip fracture repair. Random effects logistic regression models for each type of diagnostic test were developed to determine the factors that might impact test utilization. In addition to running each test as a separate model, we also performed an analysis in which the outcome was performance of any of these three cardiac tests. Random effects were used to account for clustering of testing within hospitals. Variables included time (3-month intervals), state, age (continuous variable), gender, length of stay, payer (Medicare/Medicaid/private insurance/self-pay/other), hospital teaching status (major teaching/minor teaching/nonteaching), hospital size according to number of beds (continuous variable), and mortality score. Major teaching hospitals are defined as members of the Council of Teaching Hospitals. Minor teaching hospitals are defined as (1) those with one or more postgraduate training programs recognized by the American Council on Graduate Medical Education, (2) those with a medical school affiliation reported to the American Medical Association, or (3) those with an internship or residency approved by the American Osteopathic Association.

The SID has a specific binary indicator variable for each of the three diagnostic tests we evaluated. The use of the diagnostic test is evaluated through both UB-92 revenue codes and ICD9 procedure codes, with the presence of either leading to the indicator variable being positive.10 Finally, we performed a sensitivity analysis to evaluate the significance of changing utilization trends by interrupted time series analysis. A level of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance. Analyses were done in STATA 15 (College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

The dataset included 75,144 hospitalizations with a primary procedure code of hip fracture over the study period (Table). The number of hospitalizations per year was fairly consistent over the study period in each state, although there were fewer hospitalizations for 2015 as this included only January through September. The mean age was 72.8 years, and 67% were female. The primary payer was Medicare for 71.7% of hospitalizations. Hospitalizations occurred at 181 hospitals, the plurality of which (42.9%) were minor teaching hospitals. The proportions of hospitalizations that included a TTE, stress test, and cardiac catheterization were 12.6%, 1.1%, and 0.5%, respectively. Overall, 13.5% of patients underwent any cardiac testing.

There was a statistically significantly lower rate of stress tests (odds ratio [OR], 0.32; 95% CI, 0.19-0.54) and cardiac catheterizations (OR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.27-0.79) in Washington than in Maryland and New Jersey. Female gender was associated with significantly lower adjusted ORs for stress tests (OR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.63-0.86) and cardiac catheterizations (OR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.59-0.91), and increasing age was associated with higher adjusted ORs for each test (TTE, OR, 1.033; 95% CI, 1.031-1.035; stress tests, OR, 1.007; 95% CI, 1.001-1.013; cardiac catheterizations, OR, 1.011; 95% CI, 1.003-1.019). Private insurance was associated with a lower likelihood of stress tests (OR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.50-0.85) and cardiac catheterizations (OR, 0.67; 95% CI,0.46-0.98), and self-pay was associated with a lower likelihood of TTE (OR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.61-0.95) and stress test (OR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.21-0.90), all compared with Medicare.

Larger hospitals were associated with a greater likelihood of cardiac catheterizations (OR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.03-1.36) and a lower likelihood of TTE (OR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.82-0.96). An unweighted average of these tests between 2011 and October 2015 showed a modest increase in TTEs and a modest decrease in stress tests and cardiac catheterizations (Figure). A multivariable random effects regression for use of TTEs revealed a significantly increasing trend from 2011 to 2014 (OR, 1.04, P < .0001), but the decreasing trend for 2015 was not statistically significant when analyzed according to quarters or months (for which data from only New Jersey and Washington are available).

In the combined model with any cardiac testing as the outcome, the likelihood of testing was lower in Washington (OR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.31-0.995). Primary payer status of self-pay was associated with a lower likelihood of cardiac testing (OR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.58-0.90). Female gender was associated with a lower likelihood of testing (OR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.88-0.98), and high mortality score was associated with a higher likelihood of testing (OR, 1.030; 95% CI, 1.027-1.033). TTEs were the major driver of this model as these were the most heavily utilized test.

DISCUSSION

There has been limited research into how often preoperative cardiac testing occurs in the inpatient setting. Our aim was to study its prevalence prior to hip fracture surgery during a time period when multiple recommendations had been issued to limit its use. We found rates of ischemic testing (stress tests and cardiac catheterizations) to be appropriately, and perhaps surprisingly, low. Our results on ischemic testing rates are consistent with previous studies, which have focused on the outpatient setting where much of the preoperative workup for nonurgent surgeries occurs. The rate of TTEs was higher than in previous studies of the outpatient preoperative setting, although it is unclear what an optimal rate of TTEs is.

A recent study examining outpatient preoperative stress tests within the 30 days before cataract surgeries, knee arthroscopies, or shoulder arthroscopies found a rate of 2.1% for Medicare fee-for-service patients in 2009 with little regional variation.11 Another evaluation using 2009 Medicare claims data found rates of preoperative TTEs and stress tests to be 0.8% and 0.7%, respectively.12 They included TTEs and stress tests performed within 30 days of a low- or intermediate-risk surgery. A study analyzing the rate of preoperative TTEs between 2009 and 2014 found that rates varied from 2.0% to 3.4% for commercially insured patients aged 50-64 years and Medicare-advantage patients, respectively, in 2009.13 These rates decreased by 7.0% and 12.6% from 2009 to 2014. These studies, like ours, suggest that preoperative cardiac testing has not been a major source of wasteful spending. One explanation for the higher rate of TTEs we observed in the inpatient setting might be that primary care physicians in the outpatient setting are more likely to have historical cardiac testing results compared with physicians in a hospital.

We found that the rate of stress testing and cardiac catheterization in Washington was significantly lower than that in Maryland and New Jersey. This is consistent with a number of measures of healthcare utilization – total Medicare reimbursement in the last six months of life, mean number of hospital days in the last six months of life, and healthcare intensity index—for all of which Washington was below the national mean and Maryland and New Jersey were above it.14

Finally, we found evidence of a lower rate of preoperative stress tests and cardiac catheterizations for women despite controlling for age and mortality score. Of course, we did not control directly for cardiovascular comorbidities; as a result, there could be residual confounding. However, these results are consistent with previous findings of gender bias in both pharmacologic management of coronary artery disease (CAD)15 and diagnostic testing for suspected CAD.16

We focused on hospitalizations with a primary procedure code to surgically treat hip fracture. We are unable to tell if the cardiac testing of these patients had occurred before or after the procedure. However, we suspect that the vast majority were completed for preoperative evaluation. It is likely that a small subset were done to diagnose and manage cardiac complications that either accompanied the hip fracture or occurred postoperatively. Another limitation is that we cannot determine if a patient had one of these tests recently in the emergency department or as an outpatient.

We also chose to include only patients who actually had hip fracture surgery. It is possible that the testing rate is higher for all patients admitted for hip fracture and that some of these patients did not have surgery because of abnormal cardiac testing. However, we suspect that this is a very small fraction given the high degree of morbidity and mortality associated with untreated hip fracture.

CONCLUSION

We found a low rate of preoperative cardiac testing in patients hospitalized for hip fracture surgery both in the years before and after the issuance of recommendations intended to curb its use. Although it is reassuring that the volume of low-value testing is lower than we expected, these findings highlight the importance of targeting utilization improvement efforts toward low-value tests and procedures that are more heavily used, since further curbing the use of infrequently utilized tests and procedures will have only a modest impact on overall healthcare expenditure. Our findings highlight the necessity that professional organizations ensure that they focus on true areas of inappropriate utilization. These are the areas in which improvements will have a major impact on healthcare spending. Further research should aim to quantify unwarranted cardiac testing for other inpatient surgeries that are less urgent, as the urgency of hip fracture repair may be driving the relatively low utilization of inpatient cardiac testing.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This project was supported by the Johns Hopkins Hospitalist Scholars Fund and the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Biostatistics, Epidemiology and Data Management (BEAD) Core.

Hip fracture is a common reason for unexpected, urgent inpatient surgery in older patients. In 2005, the incidence of hip fracture was 369.0 and 793.5 per 100,000 in men and women respectively.1 These numbers declined over the preceding decade, potentially as a result of bisphosphonate use. Age- and risk-adjusted 30-day mortality rates for men and women in 2005 were approximately 10% and 5%, respectively.

Evidence suggests that timely surgical repair of hip fractures improves outcomes, although the optimal timing is controversial. Guidelines from the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma from 2015 recommend surgical intervention within 48 hours for geriatric hip fracures.2 A 2008 systematic review found that operative delay beyond 48 hours was associated with a 41% increase in 30-day all-cause mortality and a 32% increase in one-year all-cause mortality.3 Recent evidence suggests that the rate of complications begins to increase with delays beyond 24 hours.4

There has been a focus over the past decade on overuse of preoperative testing for low- and intermediate-risk surgeries.5-7 Beginning in 2012, the American Board of Internal Medicine initiated the Choosing Wisely® campaign in which numerous societies issued recommendations on reducing utilization of various diagnostic tests, a number of which have focused on preoperative tests. Two groups—the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) and the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE)— issued specific recommendations on preoperative cardiac testing.8 In February 2013, the ASE recommended avoiding preoperative echocardiograms in patients without a history or symptoms of heart disease. In October 2013, the ASA recommended against transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE), transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE), or stress testing for low- or intermediate-risk noncardiac surgery for patients with stable cardiac disease.

Finally, in 2014, the American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) issued updated perioperative guidelines for patients undergoing noncardiac surgeries.9 They recommended preoperative stress testing only in a small subset of cases (patients with an elevated perioperative risk of major adverse cardiac event, a poor or unknown functional capacity, or those in whom stress testing would impact perioperative care).

Given the high cost of preoperative cardiac testing, the potential for delays in care that can adversely impact outcomes, and the recent recommendations, we sought to characterize the rates of inpatient preoperative cardiac testing prior to hip fracture surgery in recent years and to see whether recent recommendations to curb use of these tests were temporally associated with changing rates.

METHODS

Overview

We utilized two datasets—the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) State Inpatient Databases (SID) and the American Hospital Association (AHA) Annual Survey—to characterize preoperative cardiac testing. SID data from Maryland, New Jersey, and Washington State from 2011 through September 2015 were used (the ICD coding system changed from ICD9 to ICD10 on October 1). This was combined with AHA data for these years. We included all hospitalizations with a primary ICD9 procedure code for hip fracture repair—78.55, 78.65, 79.05, 79.15, 79.25, 79.35, 79.45, 79.55, 79.65, 79.75, 79.85, and 79.95. We excluded all observations that involved an interhospital transfer. This study was exempt from institutional review board approval.

Measurement and Outcomes

We summarized demographic data for the hospitalizations that met the inclusion criteria as well as the associated hospitals. The primary outcome was the percentage of patients undergoing TTE, stress test, and cardiac catheterization during a hospitalization with a primary procedure code of hip fracture repair. Random effects logistic regression models for each type of diagnostic test were developed to determine the factors that might impact test utilization. In addition to running each test as a separate model, we also performed an analysis in which the outcome was performance of any of these three cardiac tests. Random effects were used to account for clustering of testing within hospitals. Variables included time (3-month intervals), state, age (continuous variable), gender, length of stay, payer (Medicare/Medicaid/private insurance/self-pay/other), hospital teaching status (major teaching/minor teaching/nonteaching), hospital size according to number of beds (continuous variable), and mortality score. Major teaching hospitals are defined as members of the Council of Teaching Hospitals. Minor teaching hospitals are defined as (1) those with one or more postgraduate training programs recognized by the American Council on Graduate Medical Education, (2) those with a medical school affiliation reported to the American Medical Association, or (3) those with an internship or residency approved by the American Osteopathic Association.

The SID has a specific binary indicator variable for each of the three diagnostic tests we evaluated. The use of the diagnostic test is evaluated through both UB-92 revenue codes and ICD9 procedure codes, with the presence of either leading to the indicator variable being positive.10 Finally, we performed a sensitivity analysis to evaluate the significance of changing utilization trends by interrupted time series analysis. A level of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance. Analyses were done in STATA 15 (College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

The dataset included 75,144 hospitalizations with a primary procedure code of hip fracture over the study period (Table). The number of hospitalizations per year was fairly consistent over the study period in each state, although there were fewer hospitalizations for 2015 as this included only January through September. The mean age was 72.8 years, and 67% were female. The primary payer was Medicare for 71.7% of hospitalizations. Hospitalizations occurred at 181 hospitals, the plurality of which (42.9%) were minor teaching hospitals. The proportions of hospitalizations that included a TTE, stress test, and cardiac catheterization were 12.6%, 1.1%, and 0.5%, respectively. Overall, 13.5% of patients underwent any cardiac testing.

There was a statistically significantly lower rate of stress tests (odds ratio [OR], 0.32; 95% CI, 0.19-0.54) and cardiac catheterizations (OR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.27-0.79) in Washington than in Maryland and New Jersey. Female gender was associated with significantly lower adjusted ORs for stress tests (OR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.63-0.86) and cardiac catheterizations (OR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.59-0.91), and increasing age was associated with higher adjusted ORs for each test (TTE, OR, 1.033; 95% CI, 1.031-1.035; stress tests, OR, 1.007; 95% CI, 1.001-1.013; cardiac catheterizations, OR, 1.011; 95% CI, 1.003-1.019). Private insurance was associated with a lower likelihood of stress tests (OR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.50-0.85) and cardiac catheterizations (OR, 0.67; 95% CI,0.46-0.98), and self-pay was associated with a lower likelihood of TTE (OR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.61-0.95) and stress test (OR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.21-0.90), all compared with Medicare.

Larger hospitals were associated with a greater likelihood of cardiac catheterizations (OR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.03-1.36) and a lower likelihood of TTE (OR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.82-0.96). An unweighted average of these tests between 2011 and October 2015 showed a modest increase in TTEs and a modest decrease in stress tests and cardiac catheterizations (Figure). A multivariable random effects regression for use of TTEs revealed a significantly increasing trend from 2011 to 2014 (OR, 1.04, P < .0001), but the decreasing trend for 2015 was not statistically significant when analyzed according to quarters or months (for which data from only New Jersey and Washington are available).

In the combined model with any cardiac testing as the outcome, the likelihood of testing was lower in Washington (OR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.31-0.995). Primary payer status of self-pay was associated with a lower likelihood of cardiac testing (OR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.58-0.90). Female gender was associated with a lower likelihood of testing (OR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.88-0.98), and high mortality score was associated with a higher likelihood of testing (OR, 1.030; 95% CI, 1.027-1.033). TTEs were the major driver of this model as these were the most heavily utilized test.

DISCUSSION

There has been limited research into how often preoperative cardiac testing occurs in the inpatient setting. Our aim was to study its prevalence prior to hip fracture surgery during a time period when multiple recommendations had been issued to limit its use. We found rates of ischemic testing (stress tests and cardiac catheterizations) to be appropriately, and perhaps surprisingly, low. Our results on ischemic testing rates are consistent with previous studies, which have focused on the outpatient setting where much of the preoperative workup for nonurgent surgeries occurs. The rate of TTEs was higher than in previous studies of the outpatient preoperative setting, although it is unclear what an optimal rate of TTEs is.