User login

Assessment of abnormal uterine bleeding: 3 office-based tools

- Identification and measurement of the endometrial echo and descriptions of the echogenicity and heterogeneity of the endometrium are key to defining endometrial health.

- The introduction of intracervical fluid (saline-infusion sonography) during transvaginal ultrasound is one of the most significant advances in ultrasonography of the past decade.

- Hysteroscopic visualization has several advantages: immediate office evaluation, direct visualization of the endometrium and endocervix, and the ability to detect minute focal endometrial pathology and to perform directed endometrial biopsies.

- Sometimes a combination of procedures may be the best way to determine the cause of abnormal uterine bleeding.

Because office-based physicians tend to feel comfortable relying upon endometrial biopsy or dilation and curettage (D&C) to evaluate abnormal uterine bleeding, newer tools—transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS), saline-infusion sonography (SIS), and hysteroscopy—see far too little utilization. Although these modalities are remarkably user-friendly when employed correctly, only 28% of gynecologists perform office hysteroscopy, and even fewer use SIS.1

This article reviews indications for use, sensitivity and specificity, advantages and disadvantages, special considerations including cost issues, and suggestions for incorporating these modalities into gynecologic practice.

For most patients, neither endometrial biopsy nor D&C is particularly helpful in the assessment of abnormal uterine bleeding (see “Limitations of D&C and endometrial biopsy”). Does a negative biopsy signify health? An absence of intracavitary pathology? Or does it mean that we failed to sample the culprit?

Fortunately, abnormal uterine bleeding usually is attributable to endometrial conditions other than cancer, such as atrophy, hyperplasia, polyps, or fibroids. These pathologies may be benign, but they are still a nuisance. When left undetected and untreated, they can cause the patient much worry, along with weeks or months of unnecessary medical therapy and surgical procedures.

Dilation and curettage (D&C) detects benign pathology in about 80% of patients with menstrual dysfunction.1 It is most likely to detect the problem when pathology affects the endometrium globally.

A recent study reported on 105 postmenopausal women with bleeding and an endometrial echo of more than 5 mm who were evaluated with both hysteroscopy and D&C.2 Although 80% of the women had pathology in the uterine cavity, and 98% of the pathologic lesions manifested a focal growth pattern at hysteroscopy after D&C, the whole or parts of the lesion remained in situ in 87% of the women. In addition, D&C failed to detect 58% of polyps, 50% of hyperplasias, 60% of complex atypical hyperplasias, and 11% of endometrial cancers. When disease was global, D&C detected 94% of abnormalities.

Focal disease therefore mandates operative hysteroscopic-directed biopsy and removal of suspicious pathology.

Endometrial biopsy can be performed in the office without anesthesia—a great advantage. The technique is most helpful in “dating” the endometrium and diagnosing endometrial cancer or hyperplasia. Unfortunately, blind endometrial biopsy studies are frequently returned with pathology reports of insufficient tissue, atrophic changes, mucus and debris, scanty tissue, no visible endometrial tissue, endocervical tissue, or proliferative or secretory endometrium.

Further, when a blindly performed biopsy reveals normal histology, it does not necessarily rule out other pathology. In addition, a biopsy via endometrial suction curette frequently misses focal lesions such as endometrial polyps and submucosal fibroids. Global noninvasive surveillance of the endometrium is more effective at detecting such focal lesions.

Investigators who performed endometrial biopsy prior to hysterectomy in patients with known endometrial cancer demonstrated that the sensitivity of diagnosing endometrial cancer with a biopsy via endometrial suction curette increases when the pathology affects more than 50% of the surface area of the endometrial cavity.3 However, biopsy failed to detect cancer in 11 of 65 patients in whom the malignancy affected less than 50% of the endometrium. These 11 false negatives included 5 cases of endometrial polyps, 3 malignancies that affected less than 5% of the endometrium, and 7 cancers that affected less than 25% of the endometrium.

REFERENCES

1. Holst J, Koskela O, von Schoultz B. Endometrial findings following curettage in 2,018 women according to age and indications. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 1983;72:274-277.

2. Epstein E, Ramirez A, Skoog L, Valentin L. Dilation and curettage fails to detect most focal lesions in the uterine cavity in women with postmenopausal bleeding. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80:1131-1136.

3. Guido RS, Kanbour-Shakir A, Rulin MC, Christopherson WA. Pipelle endometrial sampling: sensitivity in the detection of endometrial cancer. J Reprod Med. 1995;40:553-555.

Transvaginal ultrasound

TVUS is quick, convenient, inexpensive, and comfortable for the patient. It can evaluate the endometrium utilizing gray scale, color or power Doppler, contrast media (SIS), or 3-dimensional ultrasound technology. In addition, TVUS permits visualization of the adnexa and pelvic organs, including the bladder and cul de sac. Among the abnormalities detectable with TVUS are fibroids (including submucosal leiomyomas) and endometrial polyps. Not surprisingly, an experienced operator is crucial for a precise diagnosis.

Optimal TVUS evaluation includes endometrial measurements in the sagittal plane, with the bilayer thickness measured from the proximal to distal myometrialendometrial junctions. In the coronal view, measurement should be from the cervix to the fundus. When intraluminal fluid is present, each endometrial thickness should be measured separately (in single layers), and the combined endometrial thickness should be expressed as the sum of the 2 layers.

Characterize the endometrium. Sonographic hallmarks increasingly are used to describe uterine pathology. These include endometrial thickness, morphology, endocavitary lesions, borders, and myometrial invasion. In addition, a number of practitioners have attempted to describe the sonographic texture of the endometrium in post-menopausal women to increase sensitivity in the detection of disease, improve diagnosis, and guide treatment.

The endometrium can be characterized as homogeneous, diffusely inhomogeneous, or associated with focally or diffusely increased echogenicity. Textural inhomogeneity is present in cases of endometrial cancer.2 A homogeneous endometrium less than 6 mm thick is commonly associated with tissue insufficient for diagnosis. If focal or diffuse increased echogenicity occurs with a thin endometrium, SIS or hysteroscopy is more sensitive than TVUS in identifying the endometrial abnormality.

We rely increasingly on descriptions of the echogenicity and heterogeneity of the entire endometrial echo, as well as on echo measurements, to define endometrial health. Most experts use an endometrial echo of 5 mm as the cutoff for significant endometrial disease. A number of investigators have noted that the endometrial thickness in hyperplasia often ranges from 8 mm to 15 mm in post-menopausal women, but the number of reported cases is too low to draw firm conclusions based on endometrial echo alone.3,4

A prospective evaluation of 200 postmenopausal women with endometrial echo ranging from 3 mm to 10 mm noted that homogeneity, thin endometrium, and sonographically demonstrable central endometrium with symmetry were associated with absence of pathology. In contrast, heterogeneity and high echogenicity were indicative of pathology.5

Endometrial echo measurement and morphology increase sensitivity in predicting endometrial disease and can point to the need for ancillary testing with SIS or hysteroscopy. For example, in the postmenopausal patient, an endometrial echo of less than 5 mm, in combination with a negative endometrial biopsy, might be the only evaluation the patient needs if she responds to medical therapy for endometrial atrophy. If symptoms persist, office hysteroscopy or SIS could be performed to rule out endometrial polyps and endometrial hyperplasia (which is less likely).

Saline-infusion sonography offers an exquisite view of the endomyometrial complex that cannot be obtained with transvaginal ultrasound alone.

A thickened endometrial echo (more than 5 mm) at the initial TVUS in the postmenopausal patient should be evaluated promptly with SIS. In most of these patients, polyps or fibroids are the cause of bleeding.

Perform imaging at optimal time. In postmenopausal women, the endometrial thickness remains constant unless the patient is taking hormone replacement therapy (HRT) or tamoxifen.6 Thus, it is easier to detect or predict endometrial pathology in this population.

In premenopausal women, TVUS is most likely to detect fibroids during the early follicular stage because the endometrium is thin, usually measuring 2 mm to 4 mm. Endometrial polyps and submucosal fibroids are best viewed when a trilayered midfollicular endometrium is present, while uterine synechiae are visualized most clearly during midcycle. Adhesions appear as hyperechoic irregular structures that vary in size from 2 mm to 6 mm. They interrupt the continuity of the endometrial layer and appear much different from polyps, which tend to be round, symmetrical, and uniform.7

Diagnosing endometrial hyperplasia among premenopausal women based on an absolute endometrial measurement is more difficult than it is in postmenopausal women because of the wide range in thickness associated with the menstrual cycle (TABLE 1). Although endometrial hyperplasia or cancer is more likely when the endometrial echo is thicker than anticipated based on age or menstrual phase, it can only be proven definitively with histologic sampling.

Sensitivity and specificity. Because of the monotonous nature of the endometrium in healthy postmenopausal women, TVUS has higher sensitivity in this age group than in reproductive-age women. In the postmenopausal population, the sensitivity for detecting uterine pathology is 87%, while specificity is 82%.

Office hysteroscopy offers immediate evaluation and direct visualization of the endometrium and endocervix.

In premenopausal women, polyps were the pathology most likely to be missed, according to one literature review.8 TVUS identified only 275 of 344 polyps in this population—a sensitivity of 80%. When submucosal fibroids were located near the endometrium, the diagnostic sensitivity rose to 94%. It was difficult to discern location (i.e., submucosal or intramural or polyps) with TVUS alone, however.

Another investigation compared the sensitivity and specificity of TVUS and endometrial biopsy for the detection of endometrial disease in 448 postmenopausal women who took estrogen alone, cyclic or continuous estrogen-progesterone, or placebo for 3 years.9 Using a threshold value of 5 mm for endometrial thickness, TVUS had a positive predictive value (PPV) of 9% for detecting any abnormality, with 90% sensitivity, 48% specificity, and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 99%. Using this threshold, biopsies would be indicated in more than half of the women, of whom only 4% actually had serious disease.

Using a threshold thickness of 4 mm, Gull et al10 evaluated TVUS for the detection of endometrial cancer and atypical hyperplasia. For endometrial thicknesses exceeding 4 mm, TVUS had a sensitivity of 100%, specificity of 60%, a PPV of 25%, and an NPV of 100%. No woman with an endometrial thickness of 4 mm or less was found to have endometrial cancer.

Special considerations.

- Intracavitary fluid. On occasion, TVUS reveals “naturally occurring SIS”—that is, the spontaneous appearance of intracavitary fluid, which is probably secondary to cervical stenosis. (The name of this phenomenon refers to the iatrogenic fluid that is intrinsic to SIS.) Endometrial fluid also is observed in women who use tamoxifen, diethylstilbestrol, or megestrol acetate and in those who have a hematometra. In addition, about one quarter of patients with an endometrial malignancy have fluid in the endometrial cavity.11

- Endometrial thickness. As noted, TVUS is excellent for ruling out endometrial abnormalities in postmenopausal patients because of the consistent thickness of the endometrium. When the endometrium is especially thickened, however, its usefulness is limited.

Observations in more than 5,000 women consistently note that an endometrium of less than 5 mm, measured as a double-layer, is most often associated with a pathology reading of “tissue insignificant for diagnosis”—hence atrophy.12 When the endometrium is thicker than 5 mm, there is a greater chance of detecting polyps, endometrial hyperplasia, and endometrial cancer. Fewer than 0.12% of cancers were missed in this series.

When a skilled physician performs office hysteroscopy, the complication rate is less than 1%.

If the endometrium is thicker than 6 mm, then SIS or hysteroscopy is more helpful than TVUS in reaching a conclusive etiology for uterine bleeding. Further evaluation (hysteroscopy or SIS) is usually recommended when TVUS measurements of the endometrium are greater than 5 mm.13 Although a low cut-off, such as 4 mm or 5 mm, is associated with improved sensitivity, it sacrifices specificity.

TABLE 1

Transvaginal ultrasound: Endometrial thickness32

| PHASE | THICKNESS (MM) |

|---|---|

| Menstrual | 2-4 |

| Early proliferative | 4-6 |

| Periovulatory | 6-8 |

| Secretory | 8-12 |

| Postmenopausal | 4-8 |

| Postmenopausal on hormone replacement therapy | 4-10 |

Saline-infusion sonography

In SIS, saline is infused into the endometrial cavity during TVUS to enhance the view of the endometrium. This constitutes one of the most significant advances in ultrasonography of the past decade. SIS can provide a wealth of information about the uterus and adnexa in patients with abnormal bleeding. It offers an exquisite view of the endomyometrial complex that cannot be obtained with TVUS alone. It differentiates between focal and global processes and improves overall sensitivity for detecting abnormalities of the endometrium.

Although many terms have been used to describe this technique (echohysteroscopy, sonohysterosalpingography, and hydrosonography, to name a few), the term “saline-infusion sonography,” coined in 1996, most clearly describes the technique.14

Indications for use. SIS has been used to evaluate:15

- menstrual disorders

- endometrium that is thickened, irregular, immeasurable, or poorly defined on conventional TVUS, magnetic resonance imaging, or computed axial tomography studies

- midline endometrial echo with a thickness of more than 8 mm

- endometrium that appears irregular, bizarre, or homogeneous on TVUS in women using tamoxifen

- sessile and pedunculated masses of the endometrium that need to be differentiated

- findings with hysterosalpingogram

- recurrent pregnancy loss

- intracavitary fibroids before surgery to determine the depth of myometrial involvement and operative hysteroscopic resectability (see “Using saline infusion sonography staging to plan for fibroid surgery”)

- the endometrium after surgery

Complications are infrequent. The risk of infection is less than 1%. Practitioners should follow the same protocols for administering antibiotics as they do with hysterosalpingogram or other invasive endometrial procedures.

Possible problems during SIS include cervical stenosis, inability to distend the endometrium, uterine contractions, and heavy vaginal bleeding with resultant artifacts. There is also the risk of performing the procedure in early pregnancy, as well as the theoretic risk of disseminating endometrial cancer.

Sensitivity and specificity. Interpreting SIS images requires experience, correlation with the menstrual history, and careful scanning. In premenopausal women, SIS has an overall sensitivity of 94% and a specificity of 85%.8 In 1 review, its sensitivity for detecting endometrial polyps was 93%, and its specificity was 96%.8 In the detection of submucosal fibroids, it had a sensitivity of 94% and a specificity of 95%.8

Another investigation compared the accuracy and pain of SIS with flexible office hysteroscopy.14 For all findings combined—including polyps, submucous myomas, synechiae, endometrial hyperplasia, and cancer—SIS’s sensitivity was 96% and its specificity was 88%, compared with hysteroscopy. SIS did not miss any intracavitary lesions. It was also less painful than hysteroscopy. False-positive results included diagnosing endometrial polyps as fibroids or vice versa. This is not really a problem, however, since both lesions are associated with bleeding abnormalities and both are removed with the operative hysteroscope.

False-positive results may be caused by blood, debris, clots, thickened endometrial folds, secretory endometrium, detached fragments of endometrium, or endometrium that was sheared during placement of the catheter. (When SIS is performed in the presence of active uterine bleeding, endometrial clots may sometimes be mistaken for polyps, fibroids, or hyperplasia.)

Because false positives may lead to unnecessary surgical intervention,16 SIS should be performed when these are least likely. For premenopausal women, that means scheduling SIS within 1 to 7 days of the menstrual cycle’s completion. In postmenopausal women, the patient should be scanned when she is not bleeding, if possible. If she is taking sequential HRT, SIS is best performed after progesterone withdrawal.

Until insurers realize the advantages of office-based hysteroscopy and reimburse accordingly, women will be unnecessarily subjected to surgery, preoperative testing, lost time, and increased anxiety.

Some have suggested that if SIS detects a lesion smaller than 10 mm, the procedure should be repeated when the patient is not bleeding. If the lesion is still present, operative intervention is appropriate.17,18

Cost issues. The development of clinical algorithms incorporating SIS—particularly those that take into account the differences between evaluation of premenopausal and postmenopausal women—may decrease costs by eliminating unnecessary D&Cs and endometrial biopsies, including those that are hysteroscopically directed.

For example, a study examining almost 1,200 women in 4 Nordic countries suggests that in women with postmenopausal bleeding and an endometrial thickness of 4 mm or less, curettage is unnecessary.19 An algorithm developed after the evaluation of more than 400 perimenopausal women concluded that hysteroscopically directed endometrial biopsy is best for women with focal processes, while endometrial aspiration biopsy is best for those with global disease.20

Although SIS overcomes many of the limitations of TVUS, in some cases the endometrium simply cannot be visualized.

In general, SIS is less costly to perform than hysteroscopy.

For a successful surgical outcome, it is important to preoperatively identify the size, number, location, and depth of intramural extension. Fibroid size and location affect resectability, the number of surgical procedures necessary for complete resection, the duration of surgery, and the potential complications from fluid overload.1

Using saline-infusion sonography (SIS), uterine fibroids can be categorized into 3 classes. An experienced surgeon can successfully resect class 1 (FIGURE 1) or class 2 (FIGURE 2) fibroids hysteroscopically. Class 3 fibroids (FIGURE 3) are less amenable to such surgery because perforation is a significant risk. Fluid overload, contracture of the endometrial cavity, and incomplete resection also are possible complications.2

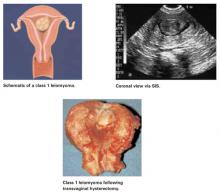

FIGURE 1 Class 1 fibroids

Class 1 fibroids occur completely within the uterine cavity, with no involvement of myometrium. The base or stalk is visible with SIS.

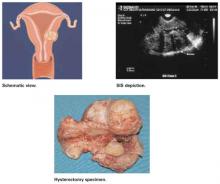

FIGURE 2 Class 2 fibroids

Class 2 fibroids have a submucosal component involving less than half of the myometruim.

FIGURE 3 Class 3 fibroids

Class 3 fibroids have an intramural component of greater than 50%. They can be transmural, and may be located anywhere from the submucosa to the serosa. These fibroids often appear as a bulge or indentation into the submucosa.

REFERENCES

1. Emanuel MH, Verdel MJ, Wamsteker K. A prospective comparison of transvaginal ultrasonography and diagnostic hysteroscopy in the evaluation of patients with abnormal uterine bleeding: Clinical implications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172:547-552.

2. Bradley LD, Falcone T, Magen AB. Radiographic imaging techniques for the diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2000;27:245-276.

Office hysteroscopy

Hysteroscopy has revolutionized the practice of gynecology. Thanks to improvements in optics and subsequent reduction in hysteroscope diameters in the 1980s and 1990s, office use has become practical. Thin operative hysteroscopes with outer diameters ranging from 3 mm to 5 mm now are available. A study in 417 women undergoing flexible hysteroscopy in an office setting without anesthesia demonstrated the patient acceptability, diagnostic accuracy, and cost-effectiveness of this technology.21

Advantages of hysteroscopic visualization include:

- immediate office evaluation

- direct visualization of the endometrium and endocervix

- the ability to detect minute focal endometrial pathology

- the ability to perform directed endometrial biopsies (with some hysteroscopes) and lyse filmy adhesions with the distal tip of the flexible hysteroscope22

Office hysteroscopy is comfortable and quick and associated with low complication rates. Preprocedural nonsteroidal agents or misoprostol may make the procedure more tolerable.

Disadvantages of office hysteroscopy include the need for expensive office equipment (camera, insufflator, hysteroscope, video equipment, etc.) and a skillful and experienced hysteroscopist, as well as the costliness of the procedure.

Complications. The complication rate is low (less than 1%) when a skilled physician performs the procedure. Complications include uterine perforation, infections, and excessive bleeding; complications related to the distending medium also have been recorded.23

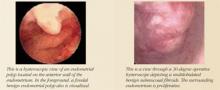

Indications for use. Entities that can be visualized hysteroscopically include:

- endometrial polyps

- submucosal and intramural fibroids

- synechiae

- retained products of conception

- foreign bodies

- endocervical lesions

- endometrial atrophy

- endometrial hyperplasia and cancer

- arteriovenous malformations

- gestational trophoblastic disease

- pregnancy (although hysteroscopy should be avoided when a viable intrauterine pregnancy has been documented)

Infrequently, endometrial gland openings associated with adenomyosis also can be seen.

On occasion, it may be difficult to distinguish hysteroscopically between a sessile polyp and submucosal fibroid if the typical characteristics of a polyp or fibroid are not appreciated. Luckily, treatment with operative hysteroscopy is the same for both findings.

Special considerations.

- Lesion size. The hysteroscopist must remember that it can be difficult to estimate the size of lesions noted. The reason: The eyepiece is focused at infinity, so objects that are closer appear magnified and objects that are further away appear smaller.24 This can lead to surprises in the operating room, especially when the size of a lesion has been underestimated. In this regard, hysteroscopy is not as accurate as TVUS.

- Rigid versus flexible. Some gynecologists may prefer to use a rigid hysteroscope because it permits a greater viewing angle than a flexible hysteroscope. In a rigid instrument, that angle ranges from 0 to 30 degrees. The outer sheaths of most rigid hysteroscopes are 3 mm to 7 mm. Larger-diameter sheaths permit insertion of biopsy instruments and graspers for directed endometrial biopsies.

- The trouble with high pressure. Hysteroscopy can produce a falsely negative view when the operator uses CO2 or high intrauterine pressure, since higher pressures can flatten an endometrial lesion. For this reason, it is wise for the hysteroscopist to get in the habit of slowly deflating the uterine cavity and carefully reinspecting the endometrial surface before concluding the procedure. A note about this maneuver should be included in the procedure report. If this approach is followed consistently, it should increase accuracy, reduce false negatives and medicolegal risk, and lead to better outcomes.

- The specificity and PPV of hysteroscopy in cases of abnormal uterine bleeding should theoretically be 100%. In practice, however, the false-negative rate is 2% to 4%—the result of operator error.25

Cost issues. The CPT code for office hysteroscopy is 58555. Regrettably, poor reimbursement has prevented rapid assimilation of this unique tool into office practice. Until insurance companies realize the marked advantages of this quick, safe, and comfortable office-based procedure and reimburse accordingly, women will be unnecessarily subjected to the rigors of surgical clearance and preoperative testing, loss of time from work and family, and the increased anxiety of having this procedure performed in an operating suite.

Comparing modalities

Investigators compared the accuracy of TVUS, transabdominal sonohysterography, and hysteroscopy in detecting submucosal fibroids (and determining their size) and myometrial growth in 52 premenopausal women scheduled for hysterectomy.26 Transabdominal sonohysterography most accurately predicted size and myometrial ingrowth of fibroids. Hysteroscopy was least accurate in detecting the myoma’s size, perhaps because of the optical refractive index with which it is associated. Still, hysteroscopy is more accurate than blind biopsy alone in detecting intracavitary lesions such as polyps and fibroids.27

SIS versus TVUS. SIS provides a more comprehensive view of the pelvic anatomy than TVUS alone, with more concentrated visualization of the endometrium. However, it can pose some technical difficulties. One group of investigators was unable to complete the procedure in patients with a uterus larger than 12 to 14 weeks, submucosal fibroids greater than 4 cm, polyps that filled the endometrial cavity, or large transmural fibroids that precluded distention of the endometrium.28 Other limitations of SIS include the inability to thread the catheter, iatrogenic introduction of air bubbles into the uterus, and the inability to maintain distension in patients with a patulous cervix.

Evaluation of the endometrium is not ‘either-or.’ Sometimes a combination of procedures aids diagnosis of menstrual dysfunction.

Patients with a distended cervix may require an SIS catheter with a balloon that occludes the lower uterine segment. Placement of the intrauterine catheter may be difficult in patients with cervical stenosis, isthmic synechiae, a markedly retroverted uterus, or intrauterine septa. Women with cervical stenosis may benefit from placement of laminaria tents or misoprostol29 (orally 100 μg 8 to 12 hours before the procedure or vaginally 200 μg to 400 μg 2 to 4 hours before the procedure). Uterine sounding may sufficiently disrupt synechiae. Cervical traction with a single-toothed tenaculum can straighten the uterine axis if marked retroversion is present.

Regardless of the patient’s age, abnormal uterine bleeding requires an aggressive workup.

SIS versus hysteroscopy. Compared with hysteroscopy, SIS more reliably predicts uterine fibroids’ size and the depth of myometrial involvement (TABLE 2).26 In addition,SIS permits classification of location, size, and degree of intramural extension. This allows the clinician to determine the resectability of the lesion and select the appropriate surgical approach.15

However, a recent comparison of SIS and hysteroscopy in diagnosing uterine pathology in 90 women with abnormal uterine bleeding showed that SIS had a high failure rate (34%) among postmenopausal women, usually because of cervical stenosis.30 In premenopausal women, that rate was lower (10.3%). The failure rate of hysteroscopy, meanwhile, was 10.6% in postmenopausal women and 2.9% in premenopausal women. Another investigation of hysteroscopy noted a failure rate of 8% in postmenopausal women.31

Complementary technologies. Although SIS overcomes many of the limitations of TVUS, in some cases the endometrium simply cannot be visualized or is indistinct, or findings are indeterminate. If the endometrium is not well visualized with SIS, then hysteroscopy plays a definitive role in ascertaining endometrial morphology. In addition to evaluating equivocal or indeterminate SIS findings, hysteroscopy is invaluable when menstrual aberrations persist despite a normal SIS.

Fortunately, evaluation of the endometrium is not an “either-or” proposition. Sometimes a combination of procedures may be important in solving the puzzle of menstrual dysfunction.

- Equivocal TVUS results. If the patient had a TVUS that led to an equivocal interpretation of the endometrium, clinicians should proceed with SIS or office hysteroscopy. If the woman continues to experience abnormal uterine bleeding after a normal SIS, diagnostic hysteroscopy should be performed to rule out occult lesions in the cornu, endocervix, or uterus.

- Pap test. It seems prudent to perform a Papanicolaou test, including an endocervical and endometrial biopsy, in high-risk patients. (This includes patients who are chronically anovulatory, obese, or nulliparous; those who use tamoxifen or unopposed estrogen; and women with untreated endometrial hyperplasia.) Keep in mind, however, that only 50% of women with endometrial cancer actually have risk factors for the disease.32

TABLE 2

Comparison of saline-infusion sonography (SIS) and hysteroscopy

| CHARACTERISTIC | SIS | HYSTEROSCOPY |

|---|---|---|

| Pain | Less | More |

| Adnexal imaging | Possible | Impossible |

| Determination of depth of fibroid penetration | Possible (accurate) | Not possible unless lesion is pedunculated |

| Cost | Less | More |

| Office based | Yes | Yes |

| Large uterine size | Difficult if uterus is >14 weeks’ size | Yes |

| Ability to complete exam | >95% cases | >95% cases |

| Complication rate | <1% | <1% |

Aggressive workup is warranted

Regardless of the patient’s age, abnormal uterine bleeding requires an aggressive workup. If we are diligent and find atrophy, we can reassure and educate the patient about the fragility of the menopausal endometrium. In most women, short-term, low-dose hormone replacement therapy is the right antidote. For the perimenopausal woman, “hormonal problems” can best be verified by a negative workup with hysteroscopy or SIS. Treatment usually consists of a low-dose contraceptive or a levonorgestrel intrauterine device, which is associated with shorter, lighter periods.

Dr. Bradley reports that she serves as a consultant to Olympus and Karl Storz.

1. Rogerson L, Duffy S. A national survey of outpatient hysteroscopy. Gynecol Endosc. 2001;10:343-348.

2. Sheikh M, Sawhney S, Khurana A, Al-Yatama M. Alteration of sonographic texture of the endometrium in post-menopausal bleeding. A guide to further management. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79:1006-1010.

3. Persadie RJ. Ultrasonographic assessment of endometrial thickness: A review. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2002;24(2):131-136.

4. Goldstein RB, Bree RL, Benson CB, et al. Evaluation of the woman with postmenopausal bleeding: Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound-Sponsored Consensus Conference statement. J Ultrasound Med. 2001;20:1025-1036.

5. Weigel M, Friese K, Strittmatter HJ, Meichert F. Measuring the thickness—is that all we have to do for sonographic assessment of endometrium in postmenopausal women? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1995;6:97-102.

6. Schwartz LB, Snyder J, Horan C, Porges RF, Nachitgall LE, Goldstein SR. The use of transvaginal ultrasound and saline infusion sonohysterography for the evaluation of asymptomatic postmenopausal breast cancer patient on tamoxifen. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1998;11:48-53.

7. Shalev J, Meizner I, Bar-Hava I, Dicker D, Mashiach R, Ben-Rafael Z. Predictive value of transvaginal sonography performed before routine diagnostic hysteroscopy for evaluation of infertility. Fert Steril. 2000;73:412-417.

8. Dueholm M, Lundorf E, Olesen F. Imaging techniques for evaluation of the uterine cavity and endometrium in premenopausal patients before minimally invasive surgery. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2002;57:389-403.

9. Langer RD, Pierce JJ, O’Hanlan KA, et al. Transvaginal ultrasonography compared with endometrial biopsy for the detection of endometrial disease. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1792-1798.

10. Gull B, Karlsson B, Milson L, Granberg S. Can ultrasound replace dilation and curettage? A longitudinal evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding and transvaginal sonographic measurement of the endometrium as predictors of endometrial cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:401-408.

11. Carlson JA, Arger P, Thompson S, Carlson EJ. Clinical and pathologic correlation of endometrial cavity fluid detected by ultrasound in the postmenopausal patient. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:119-123.

12. Weber A, Belinson J, Bradley LD, Piedmonte M. Vaginal ultrasound versus endometrial biopsy in women with postmenopausal bleeding. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177:924-929.

13. Laifer-Narin S, Ragavendra N, Parmenter EK, Grant EG. False-normal appearance of the endometrium on conventional transvaginal sonography: Comparison with saline hysterosonography. AJR. 2002;178(1):129-133.

14. Widrich T, Bradley L, Mitchinson AR, Collins R. Comparison of saline infusion sonography with office hysteroscopy for the evaluation of the endometrium. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174:1327-1334.

15. Bradley LD, Falcone T, Magen AB. Radiographic imaging techniques for the diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2000;27:245-276.

16. Mihm LM, Quick VA, Brumfield JA, Connors AF, Jr, Finnerty JJ. The accuracy of endometrial biopsy and saline sonohysterography in the determination of the cause of abnormal uterine bleeding. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:858-860.

17. Goldstein SR. Saline infusion sonohysterography. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1996;39(1):248-258.

18. Dijkhuizen FP, DeVries LD, Mol BW, et al. Comparison of transvaginal ultrasonography and saline infusion sonography for the detection of intracavitary abnormalities in premenopausal women. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2000;15:372-376.

19. Karlsson B, Granberg S, Wikland M, et al. Transvaginal ultrasonography of the endometrium in women with postmenopausal bleeding—a Nordic multicenter study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172:1488-1494.

20. Goldstein S. Use of ultrasonohysterography for triage of perimenopausal patients with unexplained uterine bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;170:565-570.

21. Bradley L, Widrich T. State-of-the-art flexible hysteroscopy for office gynecologic evaluation. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1995;2:263-267.

22. Nagele F, O’Connor H, Davies A, Badawy A, Mohamed H, Magos A. 2,500 outpatient diagnostic hysteroscopies. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:87-92.

23. Serden SP. Diagnostic hysteroscopy to evaluate the cause of abnormal uterine bleeding. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2000;27:277-286.

24. Apgar B, Dewitt D. Diagnostic hysteroscopy. Am Fam Physician. 1992;46(5 suppl):19S-26S.

25. Gimpelson R, Roppold HA. Comparative study between panoramic hysteroscopy with directed biopsies and dilation and curettage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;158:489-494.

26. Cincinelli E, Romano F, Anastasio P, et al. Transabdominal sonohysterography, transvaginal sonography, and hysteroscopy in the evaluation of submucous myomas. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:42-47.

27. Pasqualotto EB, Margossian H, Price LL, Bradley LD. Accuracy of preoperative diagnostic tools and outcome of hysteroscopic management of menstrual dysfunction. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2000;7:201-209.

28. Kochli, OR ed. Hysteroscopy: State of the Art. Contributions to Gynecology and Obstetrics. Vol. 20. Karger Verlag Basel.

29. Preutthipan S, Herabutya Y. Vaginal misoprostol for cervical priming before operative hysteroscopy: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:890-894.

30. Rogerson L, Bates J, Weston M, Duffy S. A comparison of outpatient hysteroscopy with saline infusion hysterosonography. BJOG. 2002;109:800-804.

31. Rose PG. Endometrial cancer. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:640-649.

32. Blumenfeld M, Turner P. Role of transvaginal sonography in the evaluation of endometrial hyperplasia and cancer. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1996;39:641-655.

- Identification and measurement of the endometrial echo and descriptions of the echogenicity and heterogeneity of the endometrium are key to defining endometrial health.

- The introduction of intracervical fluid (saline-infusion sonography) during transvaginal ultrasound is one of the most significant advances in ultrasonography of the past decade.

- Hysteroscopic visualization has several advantages: immediate office evaluation, direct visualization of the endometrium and endocervix, and the ability to detect minute focal endometrial pathology and to perform directed endometrial biopsies.

- Sometimes a combination of procedures may be the best way to determine the cause of abnormal uterine bleeding.

Because office-based physicians tend to feel comfortable relying upon endometrial biopsy or dilation and curettage (D&C) to evaluate abnormal uterine bleeding, newer tools—transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS), saline-infusion sonography (SIS), and hysteroscopy—see far too little utilization. Although these modalities are remarkably user-friendly when employed correctly, only 28% of gynecologists perform office hysteroscopy, and even fewer use SIS.1

This article reviews indications for use, sensitivity and specificity, advantages and disadvantages, special considerations including cost issues, and suggestions for incorporating these modalities into gynecologic practice.

For most patients, neither endometrial biopsy nor D&C is particularly helpful in the assessment of abnormal uterine bleeding (see “Limitations of D&C and endometrial biopsy”). Does a negative biopsy signify health? An absence of intracavitary pathology? Or does it mean that we failed to sample the culprit?

Fortunately, abnormal uterine bleeding usually is attributable to endometrial conditions other than cancer, such as atrophy, hyperplasia, polyps, or fibroids. These pathologies may be benign, but they are still a nuisance. When left undetected and untreated, they can cause the patient much worry, along with weeks or months of unnecessary medical therapy and surgical procedures.

Dilation and curettage (D&C) detects benign pathology in about 80% of patients with menstrual dysfunction.1 It is most likely to detect the problem when pathology affects the endometrium globally.

A recent study reported on 105 postmenopausal women with bleeding and an endometrial echo of more than 5 mm who were evaluated with both hysteroscopy and D&C.2 Although 80% of the women had pathology in the uterine cavity, and 98% of the pathologic lesions manifested a focal growth pattern at hysteroscopy after D&C, the whole or parts of the lesion remained in situ in 87% of the women. In addition, D&C failed to detect 58% of polyps, 50% of hyperplasias, 60% of complex atypical hyperplasias, and 11% of endometrial cancers. When disease was global, D&C detected 94% of abnormalities.

Focal disease therefore mandates operative hysteroscopic-directed biopsy and removal of suspicious pathology.

Endometrial biopsy can be performed in the office without anesthesia—a great advantage. The technique is most helpful in “dating” the endometrium and diagnosing endometrial cancer or hyperplasia. Unfortunately, blind endometrial biopsy studies are frequently returned with pathology reports of insufficient tissue, atrophic changes, mucus and debris, scanty tissue, no visible endometrial tissue, endocervical tissue, or proliferative or secretory endometrium.

Further, when a blindly performed biopsy reveals normal histology, it does not necessarily rule out other pathology. In addition, a biopsy via endometrial suction curette frequently misses focal lesions such as endometrial polyps and submucosal fibroids. Global noninvasive surveillance of the endometrium is more effective at detecting such focal lesions.

Investigators who performed endometrial biopsy prior to hysterectomy in patients with known endometrial cancer demonstrated that the sensitivity of diagnosing endometrial cancer with a biopsy via endometrial suction curette increases when the pathology affects more than 50% of the surface area of the endometrial cavity.3 However, biopsy failed to detect cancer in 11 of 65 patients in whom the malignancy affected less than 50% of the endometrium. These 11 false negatives included 5 cases of endometrial polyps, 3 malignancies that affected less than 5% of the endometrium, and 7 cancers that affected less than 25% of the endometrium.

REFERENCES

1. Holst J, Koskela O, von Schoultz B. Endometrial findings following curettage in 2,018 women according to age and indications. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 1983;72:274-277.

2. Epstein E, Ramirez A, Skoog L, Valentin L. Dilation and curettage fails to detect most focal lesions in the uterine cavity in women with postmenopausal bleeding. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80:1131-1136.

3. Guido RS, Kanbour-Shakir A, Rulin MC, Christopherson WA. Pipelle endometrial sampling: sensitivity in the detection of endometrial cancer. J Reprod Med. 1995;40:553-555.

Transvaginal ultrasound

TVUS is quick, convenient, inexpensive, and comfortable for the patient. It can evaluate the endometrium utilizing gray scale, color or power Doppler, contrast media (SIS), or 3-dimensional ultrasound technology. In addition, TVUS permits visualization of the adnexa and pelvic organs, including the bladder and cul de sac. Among the abnormalities detectable with TVUS are fibroids (including submucosal leiomyomas) and endometrial polyps. Not surprisingly, an experienced operator is crucial for a precise diagnosis.

Optimal TVUS evaluation includes endometrial measurements in the sagittal plane, with the bilayer thickness measured from the proximal to distal myometrialendometrial junctions. In the coronal view, measurement should be from the cervix to the fundus. When intraluminal fluid is present, each endometrial thickness should be measured separately (in single layers), and the combined endometrial thickness should be expressed as the sum of the 2 layers.

Characterize the endometrium. Sonographic hallmarks increasingly are used to describe uterine pathology. These include endometrial thickness, morphology, endocavitary lesions, borders, and myometrial invasion. In addition, a number of practitioners have attempted to describe the sonographic texture of the endometrium in post-menopausal women to increase sensitivity in the detection of disease, improve diagnosis, and guide treatment.

The endometrium can be characterized as homogeneous, diffusely inhomogeneous, or associated with focally or diffusely increased echogenicity. Textural inhomogeneity is present in cases of endometrial cancer.2 A homogeneous endometrium less than 6 mm thick is commonly associated with tissue insufficient for diagnosis. If focal or diffuse increased echogenicity occurs with a thin endometrium, SIS or hysteroscopy is more sensitive than TVUS in identifying the endometrial abnormality.

We rely increasingly on descriptions of the echogenicity and heterogeneity of the entire endometrial echo, as well as on echo measurements, to define endometrial health. Most experts use an endometrial echo of 5 mm as the cutoff for significant endometrial disease. A number of investigators have noted that the endometrial thickness in hyperplasia often ranges from 8 mm to 15 mm in post-menopausal women, but the number of reported cases is too low to draw firm conclusions based on endometrial echo alone.3,4

A prospective evaluation of 200 postmenopausal women with endometrial echo ranging from 3 mm to 10 mm noted that homogeneity, thin endometrium, and sonographically demonstrable central endometrium with symmetry were associated with absence of pathology. In contrast, heterogeneity and high echogenicity were indicative of pathology.5

Endometrial echo measurement and morphology increase sensitivity in predicting endometrial disease and can point to the need for ancillary testing with SIS or hysteroscopy. For example, in the postmenopausal patient, an endometrial echo of less than 5 mm, in combination with a negative endometrial biopsy, might be the only evaluation the patient needs if she responds to medical therapy for endometrial atrophy. If symptoms persist, office hysteroscopy or SIS could be performed to rule out endometrial polyps and endometrial hyperplasia (which is less likely).

Saline-infusion sonography offers an exquisite view of the endomyometrial complex that cannot be obtained with transvaginal ultrasound alone.

A thickened endometrial echo (more than 5 mm) at the initial TVUS in the postmenopausal patient should be evaluated promptly with SIS. In most of these patients, polyps or fibroids are the cause of bleeding.

Perform imaging at optimal time. In postmenopausal women, the endometrial thickness remains constant unless the patient is taking hormone replacement therapy (HRT) or tamoxifen.6 Thus, it is easier to detect or predict endometrial pathology in this population.

In premenopausal women, TVUS is most likely to detect fibroids during the early follicular stage because the endometrium is thin, usually measuring 2 mm to 4 mm. Endometrial polyps and submucosal fibroids are best viewed when a trilayered midfollicular endometrium is present, while uterine synechiae are visualized most clearly during midcycle. Adhesions appear as hyperechoic irregular structures that vary in size from 2 mm to 6 mm. They interrupt the continuity of the endometrial layer and appear much different from polyps, which tend to be round, symmetrical, and uniform.7

Diagnosing endometrial hyperplasia among premenopausal women based on an absolute endometrial measurement is more difficult than it is in postmenopausal women because of the wide range in thickness associated with the menstrual cycle (TABLE 1). Although endometrial hyperplasia or cancer is more likely when the endometrial echo is thicker than anticipated based on age or menstrual phase, it can only be proven definitively with histologic sampling.

Sensitivity and specificity. Because of the monotonous nature of the endometrium in healthy postmenopausal women, TVUS has higher sensitivity in this age group than in reproductive-age women. In the postmenopausal population, the sensitivity for detecting uterine pathology is 87%, while specificity is 82%.

Office hysteroscopy offers immediate evaluation and direct visualization of the endometrium and endocervix.

In premenopausal women, polyps were the pathology most likely to be missed, according to one literature review.8 TVUS identified only 275 of 344 polyps in this population—a sensitivity of 80%. When submucosal fibroids were located near the endometrium, the diagnostic sensitivity rose to 94%. It was difficult to discern location (i.e., submucosal or intramural or polyps) with TVUS alone, however.

Another investigation compared the sensitivity and specificity of TVUS and endometrial biopsy for the detection of endometrial disease in 448 postmenopausal women who took estrogen alone, cyclic or continuous estrogen-progesterone, or placebo for 3 years.9 Using a threshold value of 5 mm for endometrial thickness, TVUS had a positive predictive value (PPV) of 9% for detecting any abnormality, with 90% sensitivity, 48% specificity, and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 99%. Using this threshold, biopsies would be indicated in more than half of the women, of whom only 4% actually had serious disease.

Using a threshold thickness of 4 mm, Gull et al10 evaluated TVUS for the detection of endometrial cancer and atypical hyperplasia. For endometrial thicknesses exceeding 4 mm, TVUS had a sensitivity of 100%, specificity of 60%, a PPV of 25%, and an NPV of 100%. No woman with an endometrial thickness of 4 mm or less was found to have endometrial cancer.

Special considerations.

- Intracavitary fluid. On occasion, TVUS reveals “naturally occurring SIS”—that is, the spontaneous appearance of intracavitary fluid, which is probably secondary to cervical stenosis. (The name of this phenomenon refers to the iatrogenic fluid that is intrinsic to SIS.) Endometrial fluid also is observed in women who use tamoxifen, diethylstilbestrol, or megestrol acetate and in those who have a hematometra. In addition, about one quarter of patients with an endometrial malignancy have fluid in the endometrial cavity.11

- Endometrial thickness. As noted, TVUS is excellent for ruling out endometrial abnormalities in postmenopausal patients because of the consistent thickness of the endometrium. When the endometrium is especially thickened, however, its usefulness is limited.

Observations in more than 5,000 women consistently note that an endometrium of less than 5 mm, measured as a double-layer, is most often associated with a pathology reading of “tissue insignificant for diagnosis”—hence atrophy.12 When the endometrium is thicker than 5 mm, there is a greater chance of detecting polyps, endometrial hyperplasia, and endometrial cancer. Fewer than 0.12% of cancers were missed in this series.

When a skilled physician performs office hysteroscopy, the complication rate is less than 1%.

If the endometrium is thicker than 6 mm, then SIS or hysteroscopy is more helpful than TVUS in reaching a conclusive etiology for uterine bleeding. Further evaluation (hysteroscopy or SIS) is usually recommended when TVUS measurements of the endometrium are greater than 5 mm.13 Although a low cut-off, such as 4 mm or 5 mm, is associated with improved sensitivity, it sacrifices specificity.

TABLE 1

Transvaginal ultrasound: Endometrial thickness32

| PHASE | THICKNESS (MM) |

|---|---|

| Menstrual | 2-4 |

| Early proliferative | 4-6 |

| Periovulatory | 6-8 |

| Secretory | 8-12 |

| Postmenopausal | 4-8 |

| Postmenopausal on hormone replacement therapy | 4-10 |

Saline-infusion sonography

In SIS, saline is infused into the endometrial cavity during TVUS to enhance the view of the endometrium. This constitutes one of the most significant advances in ultrasonography of the past decade. SIS can provide a wealth of information about the uterus and adnexa in patients with abnormal bleeding. It offers an exquisite view of the endomyometrial complex that cannot be obtained with TVUS alone. It differentiates between focal and global processes and improves overall sensitivity for detecting abnormalities of the endometrium.

Although many terms have been used to describe this technique (echohysteroscopy, sonohysterosalpingography, and hydrosonography, to name a few), the term “saline-infusion sonography,” coined in 1996, most clearly describes the technique.14

Indications for use. SIS has been used to evaluate:15

- menstrual disorders

- endometrium that is thickened, irregular, immeasurable, or poorly defined on conventional TVUS, magnetic resonance imaging, or computed axial tomography studies

- midline endometrial echo with a thickness of more than 8 mm

- endometrium that appears irregular, bizarre, or homogeneous on TVUS in women using tamoxifen

- sessile and pedunculated masses of the endometrium that need to be differentiated

- findings with hysterosalpingogram

- recurrent pregnancy loss

- intracavitary fibroids before surgery to determine the depth of myometrial involvement and operative hysteroscopic resectability (see “Using saline infusion sonography staging to plan for fibroid surgery”)

- the endometrium after surgery

Complications are infrequent. The risk of infection is less than 1%. Practitioners should follow the same protocols for administering antibiotics as they do with hysterosalpingogram or other invasive endometrial procedures.

Possible problems during SIS include cervical stenosis, inability to distend the endometrium, uterine contractions, and heavy vaginal bleeding with resultant artifacts. There is also the risk of performing the procedure in early pregnancy, as well as the theoretic risk of disseminating endometrial cancer.

Sensitivity and specificity. Interpreting SIS images requires experience, correlation with the menstrual history, and careful scanning. In premenopausal women, SIS has an overall sensitivity of 94% and a specificity of 85%.8 In 1 review, its sensitivity for detecting endometrial polyps was 93%, and its specificity was 96%.8 In the detection of submucosal fibroids, it had a sensitivity of 94% and a specificity of 95%.8

Another investigation compared the accuracy and pain of SIS with flexible office hysteroscopy.14 For all findings combined—including polyps, submucous myomas, synechiae, endometrial hyperplasia, and cancer—SIS’s sensitivity was 96% and its specificity was 88%, compared with hysteroscopy. SIS did not miss any intracavitary lesions. It was also less painful than hysteroscopy. False-positive results included diagnosing endometrial polyps as fibroids or vice versa. This is not really a problem, however, since both lesions are associated with bleeding abnormalities and both are removed with the operative hysteroscope.

False-positive results may be caused by blood, debris, clots, thickened endometrial folds, secretory endometrium, detached fragments of endometrium, or endometrium that was sheared during placement of the catheter. (When SIS is performed in the presence of active uterine bleeding, endometrial clots may sometimes be mistaken for polyps, fibroids, or hyperplasia.)

Because false positives may lead to unnecessary surgical intervention,16 SIS should be performed when these are least likely. For premenopausal women, that means scheduling SIS within 1 to 7 days of the menstrual cycle’s completion. In postmenopausal women, the patient should be scanned when she is not bleeding, if possible. If she is taking sequential HRT, SIS is best performed after progesterone withdrawal.

Until insurers realize the advantages of office-based hysteroscopy and reimburse accordingly, women will be unnecessarily subjected to surgery, preoperative testing, lost time, and increased anxiety.

Some have suggested that if SIS detects a lesion smaller than 10 mm, the procedure should be repeated when the patient is not bleeding. If the lesion is still present, operative intervention is appropriate.17,18

Cost issues. The development of clinical algorithms incorporating SIS—particularly those that take into account the differences between evaluation of premenopausal and postmenopausal women—may decrease costs by eliminating unnecessary D&Cs and endometrial biopsies, including those that are hysteroscopically directed.

For example, a study examining almost 1,200 women in 4 Nordic countries suggests that in women with postmenopausal bleeding and an endometrial thickness of 4 mm or less, curettage is unnecessary.19 An algorithm developed after the evaluation of more than 400 perimenopausal women concluded that hysteroscopically directed endometrial biopsy is best for women with focal processes, while endometrial aspiration biopsy is best for those with global disease.20

Although SIS overcomes many of the limitations of TVUS, in some cases the endometrium simply cannot be visualized.

In general, SIS is less costly to perform than hysteroscopy.

For a successful surgical outcome, it is important to preoperatively identify the size, number, location, and depth of intramural extension. Fibroid size and location affect resectability, the number of surgical procedures necessary for complete resection, the duration of surgery, and the potential complications from fluid overload.1

Using saline-infusion sonography (SIS), uterine fibroids can be categorized into 3 classes. An experienced surgeon can successfully resect class 1 (FIGURE 1) or class 2 (FIGURE 2) fibroids hysteroscopically. Class 3 fibroids (FIGURE 3) are less amenable to such surgery because perforation is a significant risk. Fluid overload, contracture of the endometrial cavity, and incomplete resection also are possible complications.2

FIGURE 1 Class 1 fibroids

Class 1 fibroids occur completely within the uterine cavity, with no involvement of myometrium. The base or stalk is visible with SIS.

FIGURE 2 Class 2 fibroids

Class 2 fibroids have a submucosal component involving less than half of the myometruim.

FIGURE 3 Class 3 fibroids

Class 3 fibroids have an intramural component of greater than 50%. They can be transmural, and may be located anywhere from the submucosa to the serosa. These fibroids often appear as a bulge or indentation into the submucosa.

REFERENCES

1. Emanuel MH, Verdel MJ, Wamsteker K. A prospective comparison of transvaginal ultrasonography and diagnostic hysteroscopy in the evaluation of patients with abnormal uterine bleeding: Clinical implications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172:547-552.

2. Bradley LD, Falcone T, Magen AB. Radiographic imaging techniques for the diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2000;27:245-276.

Office hysteroscopy

Hysteroscopy has revolutionized the practice of gynecology. Thanks to improvements in optics and subsequent reduction in hysteroscope diameters in the 1980s and 1990s, office use has become practical. Thin operative hysteroscopes with outer diameters ranging from 3 mm to 5 mm now are available. A study in 417 women undergoing flexible hysteroscopy in an office setting without anesthesia demonstrated the patient acceptability, diagnostic accuracy, and cost-effectiveness of this technology.21

Advantages of hysteroscopic visualization include:

- immediate office evaluation

- direct visualization of the endometrium and endocervix

- the ability to detect minute focal endometrial pathology

- the ability to perform directed endometrial biopsies (with some hysteroscopes) and lyse filmy adhesions with the distal tip of the flexible hysteroscope22

Office hysteroscopy is comfortable and quick and associated with low complication rates. Preprocedural nonsteroidal agents or misoprostol may make the procedure more tolerable.

Disadvantages of office hysteroscopy include the need for expensive office equipment (camera, insufflator, hysteroscope, video equipment, etc.) and a skillful and experienced hysteroscopist, as well as the costliness of the procedure.

Complications. The complication rate is low (less than 1%) when a skilled physician performs the procedure. Complications include uterine perforation, infections, and excessive bleeding; complications related to the distending medium also have been recorded.23

Indications for use. Entities that can be visualized hysteroscopically include:

- endometrial polyps

- submucosal and intramural fibroids

- synechiae

- retained products of conception

- foreign bodies

- endocervical lesions

- endometrial atrophy

- endometrial hyperplasia and cancer

- arteriovenous malformations

- gestational trophoblastic disease

- pregnancy (although hysteroscopy should be avoided when a viable intrauterine pregnancy has been documented)

Infrequently, endometrial gland openings associated with adenomyosis also can be seen.

On occasion, it may be difficult to distinguish hysteroscopically between a sessile polyp and submucosal fibroid if the typical characteristics of a polyp or fibroid are not appreciated. Luckily, treatment with operative hysteroscopy is the same for both findings.

Special considerations.

- Lesion size. The hysteroscopist must remember that it can be difficult to estimate the size of lesions noted. The reason: The eyepiece is focused at infinity, so objects that are closer appear magnified and objects that are further away appear smaller.24 This can lead to surprises in the operating room, especially when the size of a lesion has been underestimated. In this regard, hysteroscopy is not as accurate as TVUS.

- Rigid versus flexible. Some gynecologists may prefer to use a rigid hysteroscope because it permits a greater viewing angle than a flexible hysteroscope. In a rigid instrument, that angle ranges from 0 to 30 degrees. The outer sheaths of most rigid hysteroscopes are 3 mm to 7 mm. Larger-diameter sheaths permit insertion of biopsy instruments and graspers for directed endometrial biopsies.

- The trouble with high pressure. Hysteroscopy can produce a falsely negative view when the operator uses CO2 or high intrauterine pressure, since higher pressures can flatten an endometrial lesion. For this reason, it is wise for the hysteroscopist to get in the habit of slowly deflating the uterine cavity and carefully reinspecting the endometrial surface before concluding the procedure. A note about this maneuver should be included in the procedure report. If this approach is followed consistently, it should increase accuracy, reduce false negatives and medicolegal risk, and lead to better outcomes.

- The specificity and PPV of hysteroscopy in cases of abnormal uterine bleeding should theoretically be 100%. In practice, however, the false-negative rate is 2% to 4%—the result of operator error.25

Cost issues. The CPT code for office hysteroscopy is 58555. Regrettably, poor reimbursement has prevented rapid assimilation of this unique tool into office practice. Until insurance companies realize the marked advantages of this quick, safe, and comfortable office-based procedure and reimburse accordingly, women will be unnecessarily subjected to the rigors of surgical clearance and preoperative testing, loss of time from work and family, and the increased anxiety of having this procedure performed in an operating suite.

Comparing modalities

Investigators compared the accuracy of TVUS, transabdominal sonohysterography, and hysteroscopy in detecting submucosal fibroids (and determining their size) and myometrial growth in 52 premenopausal women scheduled for hysterectomy.26 Transabdominal sonohysterography most accurately predicted size and myometrial ingrowth of fibroids. Hysteroscopy was least accurate in detecting the myoma’s size, perhaps because of the optical refractive index with which it is associated. Still, hysteroscopy is more accurate than blind biopsy alone in detecting intracavitary lesions such as polyps and fibroids.27

SIS versus TVUS. SIS provides a more comprehensive view of the pelvic anatomy than TVUS alone, with more concentrated visualization of the endometrium. However, it can pose some technical difficulties. One group of investigators was unable to complete the procedure in patients with a uterus larger than 12 to 14 weeks, submucosal fibroids greater than 4 cm, polyps that filled the endometrial cavity, or large transmural fibroids that precluded distention of the endometrium.28 Other limitations of SIS include the inability to thread the catheter, iatrogenic introduction of air bubbles into the uterus, and the inability to maintain distension in patients with a patulous cervix.

Evaluation of the endometrium is not ‘either-or.’ Sometimes a combination of procedures aids diagnosis of menstrual dysfunction.

Patients with a distended cervix may require an SIS catheter with a balloon that occludes the lower uterine segment. Placement of the intrauterine catheter may be difficult in patients with cervical stenosis, isthmic synechiae, a markedly retroverted uterus, or intrauterine septa. Women with cervical stenosis may benefit from placement of laminaria tents or misoprostol29 (orally 100 μg 8 to 12 hours before the procedure or vaginally 200 μg to 400 μg 2 to 4 hours before the procedure). Uterine sounding may sufficiently disrupt synechiae. Cervical traction with a single-toothed tenaculum can straighten the uterine axis if marked retroversion is present.

Regardless of the patient’s age, abnormal uterine bleeding requires an aggressive workup.

SIS versus hysteroscopy. Compared with hysteroscopy, SIS more reliably predicts uterine fibroids’ size and the depth of myometrial involvement (TABLE 2).26 In addition,SIS permits classification of location, size, and degree of intramural extension. This allows the clinician to determine the resectability of the lesion and select the appropriate surgical approach.15

However, a recent comparison of SIS and hysteroscopy in diagnosing uterine pathology in 90 women with abnormal uterine bleeding showed that SIS had a high failure rate (34%) among postmenopausal women, usually because of cervical stenosis.30 In premenopausal women, that rate was lower (10.3%). The failure rate of hysteroscopy, meanwhile, was 10.6% in postmenopausal women and 2.9% in premenopausal women. Another investigation of hysteroscopy noted a failure rate of 8% in postmenopausal women.31

Complementary technologies. Although SIS overcomes many of the limitations of TVUS, in some cases the endometrium simply cannot be visualized or is indistinct, or findings are indeterminate. If the endometrium is not well visualized with SIS, then hysteroscopy plays a definitive role in ascertaining endometrial morphology. In addition to evaluating equivocal or indeterminate SIS findings, hysteroscopy is invaluable when menstrual aberrations persist despite a normal SIS.

Fortunately, evaluation of the endometrium is not an “either-or” proposition. Sometimes a combination of procedures may be important in solving the puzzle of menstrual dysfunction.

- Equivocal TVUS results. If the patient had a TVUS that led to an equivocal interpretation of the endometrium, clinicians should proceed with SIS or office hysteroscopy. If the woman continues to experience abnormal uterine bleeding after a normal SIS, diagnostic hysteroscopy should be performed to rule out occult lesions in the cornu, endocervix, or uterus.

- Pap test. It seems prudent to perform a Papanicolaou test, including an endocervical and endometrial biopsy, in high-risk patients. (This includes patients who are chronically anovulatory, obese, or nulliparous; those who use tamoxifen or unopposed estrogen; and women with untreated endometrial hyperplasia.) Keep in mind, however, that only 50% of women with endometrial cancer actually have risk factors for the disease.32

TABLE 2

Comparison of saline-infusion sonography (SIS) and hysteroscopy

| CHARACTERISTIC | SIS | HYSTEROSCOPY |

|---|---|---|

| Pain | Less | More |

| Adnexal imaging | Possible | Impossible |

| Determination of depth of fibroid penetration | Possible (accurate) | Not possible unless lesion is pedunculated |

| Cost | Less | More |

| Office based | Yes | Yes |

| Large uterine size | Difficult if uterus is >14 weeks’ size | Yes |

| Ability to complete exam | >95% cases | >95% cases |

| Complication rate | <1% | <1% |

Aggressive workup is warranted

Regardless of the patient’s age, abnormal uterine bleeding requires an aggressive workup. If we are diligent and find atrophy, we can reassure and educate the patient about the fragility of the menopausal endometrium. In most women, short-term, low-dose hormone replacement therapy is the right antidote. For the perimenopausal woman, “hormonal problems” can best be verified by a negative workup with hysteroscopy or SIS. Treatment usually consists of a low-dose contraceptive or a levonorgestrel intrauterine device, which is associated with shorter, lighter periods.

Dr. Bradley reports that she serves as a consultant to Olympus and Karl Storz.

- Identification and measurement of the endometrial echo and descriptions of the echogenicity and heterogeneity of the endometrium are key to defining endometrial health.

- The introduction of intracervical fluid (saline-infusion sonography) during transvaginal ultrasound is one of the most significant advances in ultrasonography of the past decade.

- Hysteroscopic visualization has several advantages: immediate office evaluation, direct visualization of the endometrium and endocervix, and the ability to detect minute focal endometrial pathology and to perform directed endometrial biopsies.

- Sometimes a combination of procedures may be the best way to determine the cause of abnormal uterine bleeding.

Because office-based physicians tend to feel comfortable relying upon endometrial biopsy or dilation and curettage (D&C) to evaluate abnormal uterine bleeding, newer tools—transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS), saline-infusion sonography (SIS), and hysteroscopy—see far too little utilization. Although these modalities are remarkably user-friendly when employed correctly, only 28% of gynecologists perform office hysteroscopy, and even fewer use SIS.1

This article reviews indications for use, sensitivity and specificity, advantages and disadvantages, special considerations including cost issues, and suggestions for incorporating these modalities into gynecologic practice.

For most patients, neither endometrial biopsy nor D&C is particularly helpful in the assessment of abnormal uterine bleeding (see “Limitations of D&C and endometrial biopsy”). Does a negative biopsy signify health? An absence of intracavitary pathology? Or does it mean that we failed to sample the culprit?

Fortunately, abnormal uterine bleeding usually is attributable to endometrial conditions other than cancer, such as atrophy, hyperplasia, polyps, or fibroids. These pathologies may be benign, but they are still a nuisance. When left undetected and untreated, they can cause the patient much worry, along with weeks or months of unnecessary medical therapy and surgical procedures.

Dilation and curettage (D&C) detects benign pathology in about 80% of patients with menstrual dysfunction.1 It is most likely to detect the problem when pathology affects the endometrium globally.

A recent study reported on 105 postmenopausal women with bleeding and an endometrial echo of more than 5 mm who were evaluated with both hysteroscopy and D&C.2 Although 80% of the women had pathology in the uterine cavity, and 98% of the pathologic lesions manifested a focal growth pattern at hysteroscopy after D&C, the whole or parts of the lesion remained in situ in 87% of the women. In addition, D&C failed to detect 58% of polyps, 50% of hyperplasias, 60% of complex atypical hyperplasias, and 11% of endometrial cancers. When disease was global, D&C detected 94% of abnormalities.

Focal disease therefore mandates operative hysteroscopic-directed biopsy and removal of suspicious pathology.

Endometrial biopsy can be performed in the office without anesthesia—a great advantage. The technique is most helpful in “dating” the endometrium and diagnosing endometrial cancer or hyperplasia. Unfortunately, blind endometrial biopsy studies are frequently returned with pathology reports of insufficient tissue, atrophic changes, mucus and debris, scanty tissue, no visible endometrial tissue, endocervical tissue, or proliferative or secretory endometrium.

Further, when a blindly performed biopsy reveals normal histology, it does not necessarily rule out other pathology. In addition, a biopsy via endometrial suction curette frequently misses focal lesions such as endometrial polyps and submucosal fibroids. Global noninvasive surveillance of the endometrium is more effective at detecting such focal lesions.

Investigators who performed endometrial biopsy prior to hysterectomy in patients with known endometrial cancer demonstrated that the sensitivity of diagnosing endometrial cancer with a biopsy via endometrial suction curette increases when the pathology affects more than 50% of the surface area of the endometrial cavity.3 However, biopsy failed to detect cancer in 11 of 65 patients in whom the malignancy affected less than 50% of the endometrium. These 11 false negatives included 5 cases of endometrial polyps, 3 malignancies that affected less than 5% of the endometrium, and 7 cancers that affected less than 25% of the endometrium.

REFERENCES

1. Holst J, Koskela O, von Schoultz B. Endometrial findings following curettage in 2,018 women according to age and indications. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 1983;72:274-277.

2. Epstein E, Ramirez A, Skoog L, Valentin L. Dilation and curettage fails to detect most focal lesions in the uterine cavity in women with postmenopausal bleeding. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80:1131-1136.

3. Guido RS, Kanbour-Shakir A, Rulin MC, Christopherson WA. Pipelle endometrial sampling: sensitivity in the detection of endometrial cancer. J Reprod Med. 1995;40:553-555.

Transvaginal ultrasound

TVUS is quick, convenient, inexpensive, and comfortable for the patient. It can evaluate the endometrium utilizing gray scale, color or power Doppler, contrast media (SIS), or 3-dimensional ultrasound technology. In addition, TVUS permits visualization of the adnexa and pelvic organs, including the bladder and cul de sac. Among the abnormalities detectable with TVUS are fibroids (including submucosal leiomyomas) and endometrial polyps. Not surprisingly, an experienced operator is crucial for a precise diagnosis.

Optimal TVUS evaluation includes endometrial measurements in the sagittal plane, with the bilayer thickness measured from the proximal to distal myometrialendometrial junctions. In the coronal view, measurement should be from the cervix to the fundus. When intraluminal fluid is present, each endometrial thickness should be measured separately (in single layers), and the combined endometrial thickness should be expressed as the sum of the 2 layers.

Characterize the endometrium. Sonographic hallmarks increasingly are used to describe uterine pathology. These include endometrial thickness, morphology, endocavitary lesions, borders, and myometrial invasion. In addition, a number of practitioners have attempted to describe the sonographic texture of the endometrium in post-menopausal women to increase sensitivity in the detection of disease, improve diagnosis, and guide treatment.

The endometrium can be characterized as homogeneous, diffusely inhomogeneous, or associated with focally or diffusely increased echogenicity. Textural inhomogeneity is present in cases of endometrial cancer.2 A homogeneous endometrium less than 6 mm thick is commonly associated with tissue insufficient for diagnosis. If focal or diffuse increased echogenicity occurs with a thin endometrium, SIS or hysteroscopy is more sensitive than TVUS in identifying the endometrial abnormality.

We rely increasingly on descriptions of the echogenicity and heterogeneity of the entire endometrial echo, as well as on echo measurements, to define endometrial health. Most experts use an endometrial echo of 5 mm as the cutoff for significant endometrial disease. A number of investigators have noted that the endometrial thickness in hyperplasia often ranges from 8 mm to 15 mm in post-menopausal women, but the number of reported cases is too low to draw firm conclusions based on endometrial echo alone.3,4

A prospective evaluation of 200 postmenopausal women with endometrial echo ranging from 3 mm to 10 mm noted that homogeneity, thin endometrium, and sonographically demonstrable central endometrium with symmetry were associated with absence of pathology. In contrast, heterogeneity and high echogenicity were indicative of pathology.5

Endometrial echo measurement and morphology increase sensitivity in predicting endometrial disease and can point to the need for ancillary testing with SIS or hysteroscopy. For example, in the postmenopausal patient, an endometrial echo of less than 5 mm, in combination with a negative endometrial biopsy, might be the only evaluation the patient needs if she responds to medical therapy for endometrial atrophy. If symptoms persist, office hysteroscopy or SIS could be performed to rule out endometrial polyps and endometrial hyperplasia (which is less likely).

Saline-infusion sonography offers an exquisite view of the endomyometrial complex that cannot be obtained with transvaginal ultrasound alone.

A thickened endometrial echo (more than 5 mm) at the initial TVUS in the postmenopausal patient should be evaluated promptly with SIS. In most of these patients, polyps or fibroids are the cause of bleeding.

Perform imaging at optimal time. In postmenopausal women, the endometrial thickness remains constant unless the patient is taking hormone replacement therapy (HRT) or tamoxifen.6 Thus, it is easier to detect or predict endometrial pathology in this population.

In premenopausal women, TVUS is most likely to detect fibroids during the early follicular stage because the endometrium is thin, usually measuring 2 mm to 4 mm. Endometrial polyps and submucosal fibroids are best viewed when a trilayered midfollicular endometrium is present, while uterine synechiae are visualized most clearly during midcycle. Adhesions appear as hyperechoic irregular structures that vary in size from 2 mm to 6 mm. They interrupt the continuity of the endometrial layer and appear much different from polyps, which tend to be round, symmetrical, and uniform.7

Diagnosing endometrial hyperplasia among premenopausal women based on an absolute endometrial measurement is more difficult than it is in postmenopausal women because of the wide range in thickness associated with the menstrual cycle (TABLE 1). Although endometrial hyperplasia or cancer is more likely when the endometrial echo is thicker than anticipated based on age or menstrual phase, it can only be proven definitively with histologic sampling.

Sensitivity and specificity. Because of the monotonous nature of the endometrium in healthy postmenopausal women, TVUS has higher sensitivity in this age group than in reproductive-age women. In the postmenopausal population, the sensitivity for detecting uterine pathology is 87%, while specificity is 82%.