User login

Fibroids: Patient considerations in medical and surgical management

Uterine fibroids (myomas or leiomyomas) are common and can cause considerable morbidity, including infertility, in reproductive-aged women. In this roundtable discussion, moderated by OBG

Perspectives on a pervasive problem

Joseph S. Sanfilippo, MD, MBA: First let’s discuss the scope of the problem. How prevalent are uterine fibroids, and what are their effects on quality of life?

Linda D. Bradley, MD: Fibroids are extremely prevalent. Depending on age and race, between 60% and 80% of women have them.1 About 50% of women with fibroids have no symptoms2; in symptomatic women, the symptoms may vary based on age. Fibroids are more common in women from the African diaspora, who have earlier onset of symptoms, very large or more numerous fibroids, and more symptomatic fibroids, according to some clinical studies.3 While it is a very common disease state, about half of women with fibroids may not have significant symptoms that warrant anything more than watchful waiting or some minimally invasive options.

Ted L. Anderson, MD, PhD: We probably underestimate the scope because we see people coming in with fibroids only when they have a specific problem. There probably are a lot of asymptomatic women out there that we do not know about.

Case 1: Abnormal uterine bleeding in a young woman desiring pregnancy in the near future

Dr. Sanfilippo: Abnormal uterine bleeding is a common dilemma in my practice. Consider the following case example.

A 24-year-old woman (G1P1) presents with heavy, irregular menses over 6 months’ duration. She is interested in pregnancy, not immediately but in several months. She passes clots, soaks a pad in an hour, and has dysmenorrhea and fatigue. She uses no birth control. She is very distraught, as this bleeding truly has changed her lifestyle.

What is your approach to counseling this patient?

Dr. Bradley: You described a woman whose quality of life is very poor—frequent pad changes, clotting, pain. And she wants to have a child. A patient coming to me with those symptoms does not need to wait 4 to 6 months. I would immediately do some early evaluation.

Dr. Anderson: Sometimes a patient comes to us and already has had an ultrasonography exam. That is helpful, but I am driven by the fact that this patient is interested in pregnancy. I want to look at the uterine cavity and will probably do an office hysteroscopy to see if she has fibroids that distort the uterine cavity. Are there fibroids inside the cavity? To what degree does that possibly play a role? The presence of fibroids does not necessarily mean there is distortion of the cavity, and some evidence suggests that you do not need to do anything about those fibroids.4 Fibroids actually may not be the source of bleeding. We need to keep an open mind when we do the evaluation.

Continue to: Imaging technologies and classification aids...

Imaging technologies and classification aids

Dr. Sanfilippo: Apropos to your comment, is there a role for a sonohysterography in this population?

Dr. Anderson: That is a great technique. Some clinicians prefer to use sonohysterography while others prefer hysteroscopy. I tend to use hysteroscopy, and I have the equipment in the office. Both are great techniques and they answer the same question with respect to cavity evaluation.

Dr. Bradley: We once studied about 150 patients who, on the same day, with 2 separate examiners (one being me), would first undergo saline infusion sonohysterography (SIS) and then hysteroscopy, or vice versa. The sensitivity of identifying an intracavitary lesion is quite good with both. The additional benefit with SIS is that you can look at the adnexa.

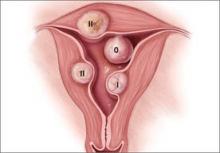

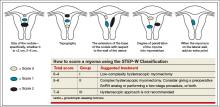

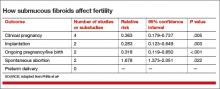

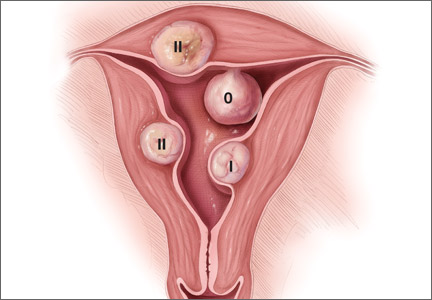

In terms of the classification by the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO), sometimes when we do a hysteroscopy, we are not sure how deep a fibroid is—whether it is a type 1 or type 2 or how close it is to the serosa (see illustration, page 26). Are we seeing just the tip of the iceberg? There is a role for imaging, and it is not always an “either/or” situation. There are times, for example, that hysteroscopy will show a type 0. Other times it may not show that, and you look for other things in terms of whether a fibroid abuts the endometrium. The take-home message is that physicians should abandon endometrial biopsy alone and, in this case, not offer a D&C.

In evaluating the endometrium, as gynecologists we should be facile in both technologies. In our workplaces we need to advocate to get trained, to be certified, and to be able to offer both technologies, because sometimes you need both to obtain the right answer.

Dr. Sanfilippo: Let’s talk about the FIGO classification, because it is important to have a communication method not only between physicians but with the patient. If we determine that a fibroid is a type 0, and therefore totally intracavitary, management is different than if the fibroid is a type 1 (less than 50% into the myometrium) or type 2 (more than 50%). What is the role for a classification system such as the FIGO?

Dr. Anderson: I like the FIGO classification system. We can show the patient fibroid classification diagrammatically and she will be able to understand exactly what we are talking about. It’s helpful for patient education and for surgical planning. The approach to a type 0 fibroid is a no-brainer, but with type 1 and more specifically with type 2, where the bulk of the fibroid is intramural and only a portion of that is intracavitary, fibroid size begins to matter a lot in terms of treatment approach.

Sometimes although a fibroid is intracavitary, a laparoscopic rather than hysteroscopic approach is preferred, as long as you can dissect the fibroid away from the endometrium. FIGO classification is very helpful, but I agree with Dr. Bradley that first you need to do a thorough evaluation to make your operative plan.

Continue to: Dr. Sanfilippo...

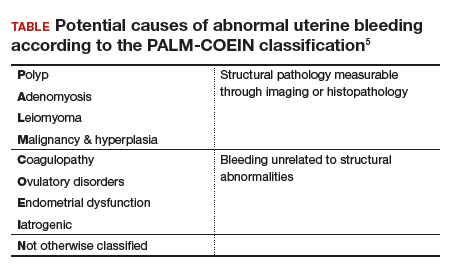

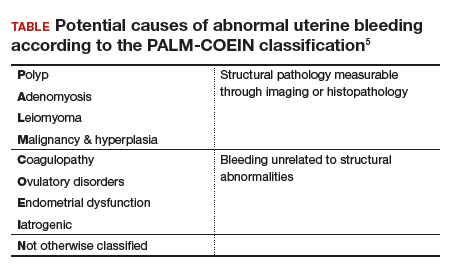

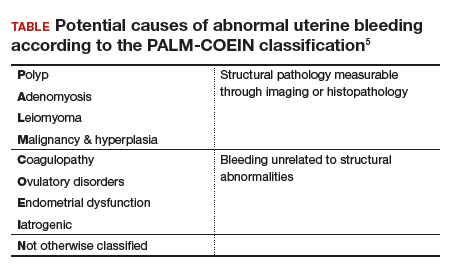

Dr. Sanfilippo: I encourage residents to go through an orderly sequence of assessment for evaluating abnormal uterine bleeding, including anatomic and endocrinologic factors. The PALM-COEIN classification system is a great mnemonic for use in evaluating abnormal uterine bleeding (TABLE).5 Is there a role for an aid such as PALM-COEIN in your practice?

Dr. Bradley: I totally agree. In 2011, Malcolm Munro and colleagues in the FIGO Working Group on Menstrual Disorders helped us to have a reporting on outcomes by knowing the size, number, and location of fibroids.5 This helps us to look for structural causes and then, to get to the answer, we often use imaging such as ultrasonography or saline infusion, sometimes magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), because other conditions can coexist—endometrial polyps, adenomyosis, and so on.

The PALM-COEIN system helps us to look at 2 things. One is that in addition to structural causes, there can be hematologic causes. While it is rare in a 24-year-old, we all have had the anecdotal patient who came in 6 months ago, had a fibroid, but had a platelet count of 6,000. Second, we have to look at the patient as a whole. My residents, myself, and our fellows look at any bleeding. Does she have a bleeding diathesis, bruising, nose bleeds; has she been anemic, does she have pica? Has she had a blood transfusion, is she on certain medications? We do not want to create a “silo” and think that the patient can have only a fibroid, because then we may miss an opportunity to treat other disease states. She can have a fibroid coexisting with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), for instance. I like to look at everything so we can offer appropriate treatment modalities.

Dr. Sanfilippo: You bring up a very important point. Coagulopathies are more common statistically at the earlier part of a woman’s reproductive age group, soon after menarche, but they also occur toward menopause. We have to be cognizant that a woman can develop a coagulopathy throughout the reproductive years.

Dr. Anderson: You have to look at other medical causes. That is where the PALM-COEIN system can help. It helps you take the blinders off. If you focus on the fibroid and treat the fibroid and the patient still has bleeding, you missed something. You have to consider the whole patient and think of all the nonclassical or nonanatomical things, for example, thyroid disease. The PALM-COEIN helps us to evaluate the patient in a methodical way—every patient every time—so you do not miss something.

The value of MRI

Dr. Sanfilippo: What is the role for MRI, and when do you use it? Is it for only when you do a procedure—laparoscopically, robotically, open—so you have a detailed map of the fibroids?

Dr. Anderson: I love MRI, especially for hysteroscopy. I will print out the MRI image and trace the fibroid because there are things I want to know: exactly how much of the fibroid is inside or outside, where this fibroid is in the uterus, and how much of a normal buffer there is between the edge of that fibroid and the serosa. How aggressive can I be, or how cautious do I need to be, during the resection? Maybe this will be a planned 2-stage resection. MRIs are wonderful for fibroid disease, not only for diagnosis but also for surgical planning and patient counseling.

Dr. Bradley: SIS is also very useful. If the patient has an intracavitary fibroid that is larger than 4.5 to 5 cm and we insert the catheter, however, sometimes you cannot distend the cavity very well. Sometimes large intramural fibroids can compress the cavity, making the procedure difficult in an office setting. You cannot see the limits to help you as a surgical option. Although SIS generally is associated with little pain, some patients may have pain, and some patients cannot tolerate the test.

Continue to: I would order an MRI for surgical planning when...

I would order an MRI for surgical planning when a hysteroscopy is equivocal and if I cannot do an SIS. Also, if a patient who had a hysteroscopic resection with incomplete removal comes to me and is still symptomatic, I want to know the depth of penetration.

Obtaining an MRI may sometimes be difficult at a particular institution, and some clinicians have to go through the hurdles of getting an ultrasound to get certified and approved. We have to be our patient’s advocate and do the peer phone calls; any other specialty would require presurgical planning, and we are no different from other surgeons in that regard.

Dr. Sanfilippo: Yes, that can be a stumbling block. In the operating room, I like to have the images right in front of me, ideally an MRI or an ultrasound scan, as I know how to proceed. Having that visual helps me understand how close the fibroid is to the lining of the uterus.

Tapping into radiologists’ expertise

Dr. Bradley: Every quarter we meet with our radiologists, who are very interested in our MRI and SIS reports. They will describe the count and say how many fibroids—that is very helpful instead of just saying she has a bunch of fibroids—but they also will tell us when there is a type 0, a type 2, a type 7 fibroid. The team looks for adenomyosis and for endometriosis that can coexist.

Dr. Anderson: One caution about reading radiology reports is that often someone will come in with a report from an outside hospital or from a small community hospital that may say, “There is a 2-cm submucosal fibroid.” Some people might be tempted to take this person right to the OR, but you need to look at the images yourself, because in a radiologist’s mind “submucosal” truly means under the mucosa, which in our liturgy would be “intramural.” So we need to make sure that we are talking the same language. You should look at the images yourself.

Dr. Sanfilippo: I totally agree. It is also not unreasonable to speak with the radiologists and educate them about the FIGO classification.

Dr. Bradley: I prefer the word “intracavitary” for fibroids. When I see a typed report without the picture, “submucosal” can mean in the cavity or abutting the endometrium.

Case 2: Woman with heavy bleeding and fibroids seeks nonsurgical treatment

Dr. Sanfilippo: A 39-year-old (G3P3) woman is referred for evaluation for heavy vaginal bleeding, soaking a pad in an hour, which has been going on for months. Her primary ObGyn obtained a pelvic sonogram and noted multiple intramural and subserosal fibroids. A sonohysterogram reveals a submucosal myoma.

The patient is not interested in a hysterectomy. She was treated with birth control pills, with no improvement. She is interested in nonsurgical options. Dr. Bradley, what medical treatments might you offer this patient?

Medical treatment options

Dr. Bradley: If oral contraceptives have not worked, a good option would be tranexamic acid. Years ago our hospital was involved with enrolling patients in the multicenter clinical trial of this drug. The classic patient enrolled had regular, predictable, heavy menstrual cycles with alkaline hematin assay of greater than 80. If the case patient described has regular and predictable heavy bleeding every month at the same time, for the same duration, I would consider the use of tranexamic acid. There are several contraindications for the drug, so those exclusion issues would need to be reviewed. Contraindications include subarachnoid hemorrhage. Cerebral edema and cerebral infarction may be caused by tranexamic acid in such patients. Other contraindications include active intravascular clotting and hypersensitivity.

Continue to: Another option is to see if a progestin-releasing intrauterine system...

Another option is to see if a progestin-releasing intrauterine system (IUS) like the levonorgestrel (LNG) IUS would fit into this patient’s uterine cavity. Like Ted, I want to look into that cavity. I am not sure what “submucosal fibroid” means. If it has not distorted the cavity, or is totally within the uterine cavity, or abuts the endometrial cavity. The LNG-IUS cannot be placed into a uterine cavity that has intracavitary fibroids or sounds to greater than 12 cm. We are not going to put an LNG-IUS in somebody, at least in general, with a globally enlarged uterine cavity. I could ask, do you do that? You do a bimanual exam, and it is 18-weeks in size. I am not sure that I would put it in, but does it meet those criteria? The package insert for the LNG-IUS specifies upper and lower limits of uterine size for placement. I would start with those 2 options (tranexamic acid and LNG-IUS), and also get some more imaging.

Dr. Anderson: I agree with Linda. The submucosal fibroid could be contributing to this patient’s bleeding, but it is not the total contribution. The other fibroids may be completely irrelevant as far as her bleeding is concerned. We may need to deal with that one surgically, which we can do without a hysterectomy, most of the time.

I am a big fan of the LNG-IUS, it has been great in my experience. There are some other treatments available as well, such as gonadotropin–releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists. I tell patients that, while GnRH does work, it is not designed to be long-term therapy. If I have, for example, a 49-year-old patient, I just need to get her to menopause. Longer-term GnRH agonists might be a good option in this case. Otherwise, we could use short-term a GnRH agonist to stop the bleeding for a while so that we can reset the clock and get her started on something like levonorgestrel, tranexamic acid, or one of the other medical therapies. That may be a 2-step combination therapy.

Dr. Sanfilippo: There is a whole category of agents available—selective progesterone receptor modulators (SPRMs), pure progesterone receptor antagonists, ulipristal comes to mind. Clinicians need to know that options are available beyond birth control pills.

Dr. Anderson: As I tell patients, there are also “bridge” options. These are interventional procedures that are not hysterectomy, such as uterine fibroid embolization or endometrial ablation if bleeding is really the problem. We might consider a variety of different approaches. Obviously, we do not typically use fibroid embolization for submucosal fibroids, but it depends on how much of the fibroid is intracavitary and how big it is. Other options are a little more aggressive than medical therapy but they do not involve a hysterectomy.

Pros and cons of uterine artery embolization

Dr. Sanfilippo: If a woman desires future childbearing, is there a role for uterine artery embolization? How would you counsel her about the pros and cons?

Dr. Bradley: At the Cleveland Clinic, we generally do not offer uterine artery embolization if the patient wants a child. While it is an excellent method for treating heavy bleeding and bulk symptoms, the endometrium can be impacted. Patients can develop fistula, adhesions, or concentric narrowing, and changes in anti-Müllerian hormone levels, and there is potential for an Asherman-like syndrome and poor perfusion. I have many hysteroscopic images where the anterior wall of the uterus is nice and pink and the posterior wall is totally pale. The embolic microsphere particles can reach the endometrium—I have seen particles in the endometrium when doing a fibroid resection.

Continue to: A good early study looked at 555 women for almost a year...

A good early study looked at 555 women for almost a year.6 If women became pregnant, they had a higher rate of postpartum hemorrhage; placenta accreta, increta, and percreta; and emergent hysterectomy. It was recommended that these women deliver at a tertiary care center due to higher rates of preterm labor and malposition.

If a patient wants a baby, she should find a gynecologic surgeon who does minimally invasive laparoscopic, robotic, or open surgery, because she is more likely to have a take-home baby with a surgical approach than with embolization. In my experience, there is always going to be a patient who wants to keep her uterus at age 49 and who has every comorbidity. I might offer her the embolization just knowing what the odds of pregnancy are.

Dr. Anderson: I agree with Linda but I take a more liberal approach. Sometimes we do a myomectomy because we are trying to enhance fertility, while other times we do a myomectomy to address fibroid-related symptoms. These patients are having specific symptoms, and we want to leave the embolization option open.

If I have a patient who is 39 and becoming pregnant is not necessarily her goal, but she does not want to have a hysterectomy and if she got pregnant it would be okay, I am going to treat her a little different with respect to fibroid embolization than I would treat someone who is actively trying to have a baby. This goes back to what you were saying, let’s treat the patient, not just the fibroid.

Dr. Bradley: That is so important and sentinel. If she really does not want a hysterectomy but does not want a baby, I will ask, “Would you go through in vitro fertilization? Would you take clomiphene?” If she answers no, then I feel more comfortable, like you, with referring the patient for uterine fibroid embolization. The point is to get the patient with the right team to get the best outcomes.

Surgical approaches, intraoperative agents, and suture technique

Dr. Sanfilippo: Dr. Anderson, tell us about your surgical approaches to fibroids.

Dr. Anderson: At my institution we do have a fellowship in minimally invasive surgery, but I still do a lot of open myomectomies. I have a few guidelines to determine whether I am going to proceed laparoscopically, do a little minilaparotomy incision, or if a gigantic uterus is going to require a big incision. My mantra to my fellows has always been, “minimally invasive is the impact on the patient, not the size of the incision.”

Sometimes, prolonged anesthesia and Trendelenburg create more morbidity than a minilaparotomy. If a patient has 4 or 5 fibroids and most of them are intramural and I cannot see them but I want to be able to feel them, and to get a really good closure of the myometrium, I might choose to do a minilaparotomy. But if it is a case of a solitary fibroid, I would be more inclined to operate laparoscopically.

Continue to: Dr. Bradley...

Dr. Bradley: Our protocol is similar. We use MRI liberally. If patients have 4 or more fibroids and they are larger than 8 cm, most will have open surgery. I do not do robotic or laparoscopic procedures, so my referral source is for the larger myomas. We do not put retractors in; we can make incisions. Even if we do a huge Maylard incision, it is cosmetically wonderful. We use a loading dose of IV tranexamic acid with tranexamic acid throughout the surgery, and misoprostol intravaginally prior to surgery, to control uterine bleeding.

Dr. Sanfilippo: Dr. Anderson, is there a role for agents such as vasopressin, and what about routes of administration?

Dr. Anderson: When I do a laparoscopic or open procedure, I inject vasopressin (dilute 20 U in 100 mL of saline) into the pseudocapsule around the fibroid. I also administer rectal misoprostol (400 µg) just before the patient prep is done, which is amazing in reducing blood loss. There is also a role for a GnRH agonist, not necessarily to reduce the size of the uterus but to reduce blood flow in the pelvis and blood loss. Many different techniques are available. I do not use tourniquets, however. If bleeding does occur, I want to see it so I can fix it—not after I have sewn up the uterus and taken off a tourniquet.

Dr. Bradley: Do you use Floseal hemostatic matrix or any other agent to control bleeding?

Dr. Anderson: I do, for local hemostasis.

Dr. Bradley: Some surgeons will use barbed suture.

Dr. Anderson: I do like barbed sutures. In teaching residents to do myomectomy, it is very beneficial. But I am still a big fan of the good old figure-of-8 stitch because it is compressive and you get a good apposition of the tissue, good hemostasis, and strong closure.

Dr. Sanfilippo: We hope that this conversation will change your management of uterine fibroids. I thank Dr. Bradley and Dr. Anderson for a lively and very informative discussion.

Watch the video: Video roundtable–Fibroids: Patient considerations in medical and surgical management

- Khan AT, Shehmar M, Gupta JK. Uterine fibroids: current perspectives. Int J Womens Health. 2014;6:95-114.

- Divakars H. Asymptomatic uterine fibroids. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;22:643-654.

- Stewart EA, Nicholson WK, Bradley L, et al. The burden of uterine fibroids for African-American women: results of a national survey. J Womens Health. 2013;22:807-816.

- Hartmann KE, Velez Edwards DR, Savitz DA, et al. Prospective cohort study of uterine fibroids and miscarriage risk. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186:1140-1148.

- Munro MG, Critchley HOD, Fraser IS, for the FIGO Menstrual Disorders Working Group. The FIGO classification of causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in the reproductive years. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:2204-2208.

- Pron G, Mocarski E, Bennett J, et al; Ontario UFE Collaborative Group. Pregnancy after uterine artery embolization for leiomyomata: the Ontario multicenter trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:67-76.

Uterine fibroids (myomas or leiomyomas) are common and can cause considerable morbidity, including infertility, in reproductive-aged women. In this roundtable discussion, moderated by OBG

Perspectives on a pervasive problem

Joseph S. Sanfilippo, MD, MBA: First let’s discuss the scope of the problem. How prevalent are uterine fibroids, and what are their effects on quality of life?

Linda D. Bradley, MD: Fibroids are extremely prevalent. Depending on age and race, between 60% and 80% of women have them.1 About 50% of women with fibroids have no symptoms2; in symptomatic women, the symptoms may vary based on age. Fibroids are more common in women from the African diaspora, who have earlier onset of symptoms, very large or more numerous fibroids, and more symptomatic fibroids, according to some clinical studies.3 While it is a very common disease state, about half of women with fibroids may not have significant symptoms that warrant anything more than watchful waiting or some minimally invasive options.

Ted L. Anderson, MD, PhD: We probably underestimate the scope because we see people coming in with fibroids only when they have a specific problem. There probably are a lot of asymptomatic women out there that we do not know about.

Case 1: Abnormal uterine bleeding in a young woman desiring pregnancy in the near future

Dr. Sanfilippo: Abnormal uterine bleeding is a common dilemma in my practice. Consider the following case example.

A 24-year-old woman (G1P1) presents with heavy, irregular menses over 6 months’ duration. She is interested in pregnancy, not immediately but in several months. She passes clots, soaks a pad in an hour, and has dysmenorrhea and fatigue. She uses no birth control. She is very distraught, as this bleeding truly has changed her lifestyle.

What is your approach to counseling this patient?

Dr. Bradley: You described a woman whose quality of life is very poor—frequent pad changes, clotting, pain. And she wants to have a child. A patient coming to me with those symptoms does not need to wait 4 to 6 months. I would immediately do some early evaluation.

Dr. Anderson: Sometimes a patient comes to us and already has had an ultrasonography exam. That is helpful, but I am driven by the fact that this patient is interested in pregnancy. I want to look at the uterine cavity and will probably do an office hysteroscopy to see if she has fibroids that distort the uterine cavity. Are there fibroids inside the cavity? To what degree does that possibly play a role? The presence of fibroids does not necessarily mean there is distortion of the cavity, and some evidence suggests that you do not need to do anything about those fibroids.4 Fibroids actually may not be the source of bleeding. We need to keep an open mind when we do the evaluation.

Continue to: Imaging technologies and classification aids...

Imaging technologies and classification aids

Dr. Sanfilippo: Apropos to your comment, is there a role for a sonohysterography in this population?

Dr. Anderson: That is a great technique. Some clinicians prefer to use sonohysterography while others prefer hysteroscopy. I tend to use hysteroscopy, and I have the equipment in the office. Both are great techniques and they answer the same question with respect to cavity evaluation.

Dr. Bradley: We once studied about 150 patients who, on the same day, with 2 separate examiners (one being me), would first undergo saline infusion sonohysterography (SIS) and then hysteroscopy, or vice versa. The sensitivity of identifying an intracavitary lesion is quite good with both. The additional benefit with SIS is that you can look at the adnexa.

In terms of the classification by the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO), sometimes when we do a hysteroscopy, we are not sure how deep a fibroid is—whether it is a type 1 or type 2 or how close it is to the serosa (see illustration, page 26). Are we seeing just the tip of the iceberg? There is a role for imaging, and it is not always an “either/or” situation. There are times, for example, that hysteroscopy will show a type 0. Other times it may not show that, and you look for other things in terms of whether a fibroid abuts the endometrium. The take-home message is that physicians should abandon endometrial biopsy alone and, in this case, not offer a D&C.

In evaluating the endometrium, as gynecologists we should be facile in both technologies. In our workplaces we need to advocate to get trained, to be certified, and to be able to offer both technologies, because sometimes you need both to obtain the right answer.

Dr. Sanfilippo: Let’s talk about the FIGO classification, because it is important to have a communication method not only between physicians but with the patient. If we determine that a fibroid is a type 0, and therefore totally intracavitary, management is different than if the fibroid is a type 1 (less than 50% into the myometrium) or type 2 (more than 50%). What is the role for a classification system such as the FIGO?

Dr. Anderson: I like the FIGO classification system. We can show the patient fibroid classification diagrammatically and she will be able to understand exactly what we are talking about. It’s helpful for patient education and for surgical planning. The approach to a type 0 fibroid is a no-brainer, but with type 1 and more specifically with type 2, where the bulk of the fibroid is intramural and only a portion of that is intracavitary, fibroid size begins to matter a lot in terms of treatment approach.

Sometimes although a fibroid is intracavitary, a laparoscopic rather than hysteroscopic approach is preferred, as long as you can dissect the fibroid away from the endometrium. FIGO classification is very helpful, but I agree with Dr. Bradley that first you need to do a thorough evaluation to make your operative plan.

Continue to: Dr. Sanfilippo...

Dr. Sanfilippo: I encourage residents to go through an orderly sequence of assessment for evaluating abnormal uterine bleeding, including anatomic and endocrinologic factors. The PALM-COEIN classification system is a great mnemonic for use in evaluating abnormal uterine bleeding (TABLE).5 Is there a role for an aid such as PALM-COEIN in your practice?

Dr. Bradley: I totally agree. In 2011, Malcolm Munro and colleagues in the FIGO Working Group on Menstrual Disorders helped us to have a reporting on outcomes by knowing the size, number, and location of fibroids.5 This helps us to look for structural causes and then, to get to the answer, we often use imaging such as ultrasonography or saline infusion, sometimes magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), because other conditions can coexist—endometrial polyps, adenomyosis, and so on.

The PALM-COEIN system helps us to look at 2 things. One is that in addition to structural causes, there can be hematologic causes. While it is rare in a 24-year-old, we all have had the anecdotal patient who came in 6 months ago, had a fibroid, but had a platelet count of 6,000. Second, we have to look at the patient as a whole. My residents, myself, and our fellows look at any bleeding. Does she have a bleeding diathesis, bruising, nose bleeds; has she been anemic, does she have pica? Has she had a blood transfusion, is she on certain medications? We do not want to create a “silo” and think that the patient can have only a fibroid, because then we may miss an opportunity to treat other disease states. She can have a fibroid coexisting with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), for instance. I like to look at everything so we can offer appropriate treatment modalities.

Dr. Sanfilippo: You bring up a very important point. Coagulopathies are more common statistically at the earlier part of a woman’s reproductive age group, soon after menarche, but they also occur toward menopause. We have to be cognizant that a woman can develop a coagulopathy throughout the reproductive years.

Dr. Anderson: You have to look at other medical causes. That is where the PALM-COEIN system can help. It helps you take the blinders off. If you focus on the fibroid and treat the fibroid and the patient still has bleeding, you missed something. You have to consider the whole patient and think of all the nonclassical or nonanatomical things, for example, thyroid disease. The PALM-COEIN helps us to evaluate the patient in a methodical way—every patient every time—so you do not miss something.

The value of MRI

Dr. Sanfilippo: What is the role for MRI, and when do you use it? Is it for only when you do a procedure—laparoscopically, robotically, open—so you have a detailed map of the fibroids?

Dr. Anderson: I love MRI, especially for hysteroscopy. I will print out the MRI image and trace the fibroid because there are things I want to know: exactly how much of the fibroid is inside or outside, where this fibroid is in the uterus, and how much of a normal buffer there is between the edge of that fibroid and the serosa. How aggressive can I be, or how cautious do I need to be, during the resection? Maybe this will be a planned 2-stage resection. MRIs are wonderful for fibroid disease, not only for diagnosis but also for surgical planning and patient counseling.

Dr. Bradley: SIS is also very useful. If the patient has an intracavitary fibroid that is larger than 4.5 to 5 cm and we insert the catheter, however, sometimes you cannot distend the cavity very well. Sometimes large intramural fibroids can compress the cavity, making the procedure difficult in an office setting. You cannot see the limits to help you as a surgical option. Although SIS generally is associated with little pain, some patients may have pain, and some patients cannot tolerate the test.

Continue to: I would order an MRI for surgical planning when...

I would order an MRI for surgical planning when a hysteroscopy is equivocal and if I cannot do an SIS. Also, if a patient who had a hysteroscopic resection with incomplete removal comes to me and is still symptomatic, I want to know the depth of penetration.

Obtaining an MRI may sometimes be difficult at a particular institution, and some clinicians have to go through the hurdles of getting an ultrasound to get certified and approved. We have to be our patient’s advocate and do the peer phone calls; any other specialty would require presurgical planning, and we are no different from other surgeons in that regard.

Dr. Sanfilippo: Yes, that can be a stumbling block. In the operating room, I like to have the images right in front of me, ideally an MRI or an ultrasound scan, as I know how to proceed. Having that visual helps me understand how close the fibroid is to the lining of the uterus.

Tapping into radiologists’ expertise

Dr. Bradley: Every quarter we meet with our radiologists, who are very interested in our MRI and SIS reports. They will describe the count and say how many fibroids—that is very helpful instead of just saying she has a bunch of fibroids—but they also will tell us when there is a type 0, a type 2, a type 7 fibroid. The team looks for adenomyosis and for endometriosis that can coexist.

Dr. Anderson: One caution about reading radiology reports is that often someone will come in with a report from an outside hospital or from a small community hospital that may say, “There is a 2-cm submucosal fibroid.” Some people might be tempted to take this person right to the OR, but you need to look at the images yourself, because in a radiologist’s mind “submucosal” truly means under the mucosa, which in our liturgy would be “intramural.” So we need to make sure that we are talking the same language. You should look at the images yourself.

Dr. Sanfilippo: I totally agree. It is also not unreasonable to speak with the radiologists and educate them about the FIGO classification.

Dr. Bradley: I prefer the word “intracavitary” for fibroids. When I see a typed report without the picture, “submucosal” can mean in the cavity or abutting the endometrium.

Case 2: Woman with heavy bleeding and fibroids seeks nonsurgical treatment

Dr. Sanfilippo: A 39-year-old (G3P3) woman is referred for evaluation for heavy vaginal bleeding, soaking a pad in an hour, which has been going on for months. Her primary ObGyn obtained a pelvic sonogram and noted multiple intramural and subserosal fibroids. A sonohysterogram reveals a submucosal myoma.

The patient is not interested in a hysterectomy. She was treated with birth control pills, with no improvement. She is interested in nonsurgical options. Dr. Bradley, what medical treatments might you offer this patient?

Medical treatment options

Dr. Bradley: If oral contraceptives have not worked, a good option would be tranexamic acid. Years ago our hospital was involved with enrolling patients in the multicenter clinical trial of this drug. The classic patient enrolled had regular, predictable, heavy menstrual cycles with alkaline hematin assay of greater than 80. If the case patient described has regular and predictable heavy bleeding every month at the same time, for the same duration, I would consider the use of tranexamic acid. There are several contraindications for the drug, so those exclusion issues would need to be reviewed. Contraindications include subarachnoid hemorrhage. Cerebral edema and cerebral infarction may be caused by tranexamic acid in such patients. Other contraindications include active intravascular clotting and hypersensitivity.

Continue to: Another option is to see if a progestin-releasing intrauterine system...

Another option is to see if a progestin-releasing intrauterine system (IUS) like the levonorgestrel (LNG) IUS would fit into this patient’s uterine cavity. Like Ted, I want to look into that cavity. I am not sure what “submucosal fibroid” means. If it has not distorted the cavity, or is totally within the uterine cavity, or abuts the endometrial cavity. The LNG-IUS cannot be placed into a uterine cavity that has intracavitary fibroids or sounds to greater than 12 cm. We are not going to put an LNG-IUS in somebody, at least in general, with a globally enlarged uterine cavity. I could ask, do you do that? You do a bimanual exam, and it is 18-weeks in size. I am not sure that I would put it in, but does it meet those criteria? The package insert for the LNG-IUS specifies upper and lower limits of uterine size for placement. I would start with those 2 options (tranexamic acid and LNG-IUS), and also get some more imaging.

Dr. Anderson: I agree with Linda. The submucosal fibroid could be contributing to this patient’s bleeding, but it is not the total contribution. The other fibroids may be completely irrelevant as far as her bleeding is concerned. We may need to deal with that one surgically, which we can do without a hysterectomy, most of the time.

I am a big fan of the LNG-IUS, it has been great in my experience. There are some other treatments available as well, such as gonadotropin–releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists. I tell patients that, while GnRH does work, it is not designed to be long-term therapy. If I have, for example, a 49-year-old patient, I just need to get her to menopause. Longer-term GnRH agonists might be a good option in this case. Otherwise, we could use short-term a GnRH agonist to stop the bleeding for a while so that we can reset the clock and get her started on something like levonorgestrel, tranexamic acid, or one of the other medical therapies. That may be a 2-step combination therapy.

Dr. Sanfilippo: There is a whole category of agents available—selective progesterone receptor modulators (SPRMs), pure progesterone receptor antagonists, ulipristal comes to mind. Clinicians need to know that options are available beyond birth control pills.

Dr. Anderson: As I tell patients, there are also “bridge” options. These are interventional procedures that are not hysterectomy, such as uterine fibroid embolization or endometrial ablation if bleeding is really the problem. We might consider a variety of different approaches. Obviously, we do not typically use fibroid embolization for submucosal fibroids, but it depends on how much of the fibroid is intracavitary and how big it is. Other options are a little more aggressive than medical therapy but they do not involve a hysterectomy.

Pros and cons of uterine artery embolization

Dr. Sanfilippo: If a woman desires future childbearing, is there a role for uterine artery embolization? How would you counsel her about the pros and cons?

Dr. Bradley: At the Cleveland Clinic, we generally do not offer uterine artery embolization if the patient wants a child. While it is an excellent method for treating heavy bleeding and bulk symptoms, the endometrium can be impacted. Patients can develop fistula, adhesions, or concentric narrowing, and changes in anti-Müllerian hormone levels, and there is potential for an Asherman-like syndrome and poor perfusion. I have many hysteroscopic images where the anterior wall of the uterus is nice and pink and the posterior wall is totally pale. The embolic microsphere particles can reach the endometrium—I have seen particles in the endometrium when doing a fibroid resection.

Continue to: A good early study looked at 555 women for almost a year...

A good early study looked at 555 women for almost a year.6 If women became pregnant, they had a higher rate of postpartum hemorrhage; placenta accreta, increta, and percreta; and emergent hysterectomy. It was recommended that these women deliver at a tertiary care center due to higher rates of preterm labor and malposition.

If a patient wants a baby, she should find a gynecologic surgeon who does minimally invasive laparoscopic, robotic, or open surgery, because she is more likely to have a take-home baby with a surgical approach than with embolization. In my experience, there is always going to be a patient who wants to keep her uterus at age 49 and who has every comorbidity. I might offer her the embolization just knowing what the odds of pregnancy are.

Dr. Anderson: I agree with Linda but I take a more liberal approach. Sometimes we do a myomectomy because we are trying to enhance fertility, while other times we do a myomectomy to address fibroid-related symptoms. These patients are having specific symptoms, and we want to leave the embolization option open.

If I have a patient who is 39 and becoming pregnant is not necessarily her goal, but she does not want to have a hysterectomy and if she got pregnant it would be okay, I am going to treat her a little different with respect to fibroid embolization than I would treat someone who is actively trying to have a baby. This goes back to what you were saying, let’s treat the patient, not just the fibroid.

Dr. Bradley: That is so important and sentinel. If she really does not want a hysterectomy but does not want a baby, I will ask, “Would you go through in vitro fertilization? Would you take clomiphene?” If she answers no, then I feel more comfortable, like you, with referring the patient for uterine fibroid embolization. The point is to get the patient with the right team to get the best outcomes.

Surgical approaches, intraoperative agents, and suture technique

Dr. Sanfilippo: Dr. Anderson, tell us about your surgical approaches to fibroids.

Dr. Anderson: At my institution we do have a fellowship in minimally invasive surgery, but I still do a lot of open myomectomies. I have a few guidelines to determine whether I am going to proceed laparoscopically, do a little minilaparotomy incision, or if a gigantic uterus is going to require a big incision. My mantra to my fellows has always been, “minimally invasive is the impact on the patient, not the size of the incision.”

Sometimes, prolonged anesthesia and Trendelenburg create more morbidity than a minilaparotomy. If a patient has 4 or 5 fibroids and most of them are intramural and I cannot see them but I want to be able to feel them, and to get a really good closure of the myometrium, I might choose to do a minilaparotomy. But if it is a case of a solitary fibroid, I would be more inclined to operate laparoscopically.

Continue to: Dr. Bradley...

Dr. Bradley: Our protocol is similar. We use MRI liberally. If patients have 4 or more fibroids and they are larger than 8 cm, most will have open surgery. I do not do robotic or laparoscopic procedures, so my referral source is for the larger myomas. We do not put retractors in; we can make incisions. Even if we do a huge Maylard incision, it is cosmetically wonderful. We use a loading dose of IV tranexamic acid with tranexamic acid throughout the surgery, and misoprostol intravaginally prior to surgery, to control uterine bleeding.

Dr. Sanfilippo: Dr. Anderson, is there a role for agents such as vasopressin, and what about routes of administration?

Dr. Anderson: When I do a laparoscopic or open procedure, I inject vasopressin (dilute 20 U in 100 mL of saline) into the pseudocapsule around the fibroid. I also administer rectal misoprostol (400 µg) just before the patient prep is done, which is amazing in reducing blood loss. There is also a role for a GnRH agonist, not necessarily to reduce the size of the uterus but to reduce blood flow in the pelvis and blood loss. Many different techniques are available. I do not use tourniquets, however. If bleeding does occur, I want to see it so I can fix it—not after I have sewn up the uterus and taken off a tourniquet.

Dr. Bradley: Do you use Floseal hemostatic matrix or any other agent to control bleeding?

Dr. Anderson: I do, for local hemostasis.

Dr. Bradley: Some surgeons will use barbed suture.

Dr. Anderson: I do like barbed sutures. In teaching residents to do myomectomy, it is very beneficial. But I am still a big fan of the good old figure-of-8 stitch because it is compressive and you get a good apposition of the tissue, good hemostasis, and strong closure.

Dr. Sanfilippo: We hope that this conversation will change your management of uterine fibroids. I thank Dr. Bradley and Dr. Anderson for a lively and very informative discussion.

Watch the video: Video roundtable–Fibroids: Patient considerations in medical and surgical management

Uterine fibroids (myomas or leiomyomas) are common and can cause considerable morbidity, including infertility, in reproductive-aged women. In this roundtable discussion, moderated by OBG

Perspectives on a pervasive problem

Joseph S. Sanfilippo, MD, MBA: First let’s discuss the scope of the problem. How prevalent are uterine fibroids, and what are their effects on quality of life?

Linda D. Bradley, MD: Fibroids are extremely prevalent. Depending on age and race, between 60% and 80% of women have them.1 About 50% of women with fibroids have no symptoms2; in symptomatic women, the symptoms may vary based on age. Fibroids are more common in women from the African diaspora, who have earlier onset of symptoms, very large or more numerous fibroids, and more symptomatic fibroids, according to some clinical studies.3 While it is a very common disease state, about half of women with fibroids may not have significant symptoms that warrant anything more than watchful waiting or some minimally invasive options.

Ted L. Anderson, MD, PhD: We probably underestimate the scope because we see people coming in with fibroids only when they have a specific problem. There probably are a lot of asymptomatic women out there that we do not know about.

Case 1: Abnormal uterine bleeding in a young woman desiring pregnancy in the near future

Dr. Sanfilippo: Abnormal uterine bleeding is a common dilemma in my practice. Consider the following case example.

A 24-year-old woman (G1P1) presents with heavy, irregular menses over 6 months’ duration. She is interested in pregnancy, not immediately but in several months. She passes clots, soaks a pad in an hour, and has dysmenorrhea and fatigue. She uses no birth control. She is very distraught, as this bleeding truly has changed her lifestyle.

What is your approach to counseling this patient?

Dr. Bradley: You described a woman whose quality of life is very poor—frequent pad changes, clotting, pain. And she wants to have a child. A patient coming to me with those symptoms does not need to wait 4 to 6 months. I would immediately do some early evaluation.

Dr. Anderson: Sometimes a patient comes to us and already has had an ultrasonography exam. That is helpful, but I am driven by the fact that this patient is interested in pregnancy. I want to look at the uterine cavity and will probably do an office hysteroscopy to see if she has fibroids that distort the uterine cavity. Are there fibroids inside the cavity? To what degree does that possibly play a role? The presence of fibroids does not necessarily mean there is distortion of the cavity, and some evidence suggests that you do not need to do anything about those fibroids.4 Fibroids actually may not be the source of bleeding. We need to keep an open mind when we do the evaluation.

Continue to: Imaging technologies and classification aids...

Imaging technologies and classification aids

Dr. Sanfilippo: Apropos to your comment, is there a role for a sonohysterography in this population?

Dr. Anderson: That is a great technique. Some clinicians prefer to use sonohysterography while others prefer hysteroscopy. I tend to use hysteroscopy, and I have the equipment in the office. Both are great techniques and they answer the same question with respect to cavity evaluation.

Dr. Bradley: We once studied about 150 patients who, on the same day, with 2 separate examiners (one being me), would first undergo saline infusion sonohysterography (SIS) and then hysteroscopy, or vice versa. The sensitivity of identifying an intracavitary lesion is quite good with both. The additional benefit with SIS is that you can look at the adnexa.

In terms of the classification by the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO), sometimes when we do a hysteroscopy, we are not sure how deep a fibroid is—whether it is a type 1 or type 2 or how close it is to the serosa (see illustration, page 26). Are we seeing just the tip of the iceberg? There is a role for imaging, and it is not always an “either/or” situation. There are times, for example, that hysteroscopy will show a type 0. Other times it may not show that, and you look for other things in terms of whether a fibroid abuts the endometrium. The take-home message is that physicians should abandon endometrial biopsy alone and, in this case, not offer a D&C.

In evaluating the endometrium, as gynecologists we should be facile in both technologies. In our workplaces we need to advocate to get trained, to be certified, and to be able to offer both technologies, because sometimes you need both to obtain the right answer.

Dr. Sanfilippo: Let’s talk about the FIGO classification, because it is important to have a communication method not only between physicians but with the patient. If we determine that a fibroid is a type 0, and therefore totally intracavitary, management is different than if the fibroid is a type 1 (less than 50% into the myometrium) or type 2 (more than 50%). What is the role for a classification system such as the FIGO?

Dr. Anderson: I like the FIGO classification system. We can show the patient fibroid classification diagrammatically and she will be able to understand exactly what we are talking about. It’s helpful for patient education and for surgical planning. The approach to a type 0 fibroid is a no-brainer, but with type 1 and more specifically with type 2, where the bulk of the fibroid is intramural and only a portion of that is intracavitary, fibroid size begins to matter a lot in terms of treatment approach.

Sometimes although a fibroid is intracavitary, a laparoscopic rather than hysteroscopic approach is preferred, as long as you can dissect the fibroid away from the endometrium. FIGO classification is very helpful, but I agree with Dr. Bradley that first you need to do a thorough evaluation to make your operative plan.

Continue to: Dr. Sanfilippo...

Dr. Sanfilippo: I encourage residents to go through an orderly sequence of assessment for evaluating abnormal uterine bleeding, including anatomic and endocrinologic factors. The PALM-COEIN classification system is a great mnemonic for use in evaluating abnormal uterine bleeding (TABLE).5 Is there a role for an aid such as PALM-COEIN in your practice?

Dr. Bradley: I totally agree. In 2011, Malcolm Munro and colleagues in the FIGO Working Group on Menstrual Disorders helped us to have a reporting on outcomes by knowing the size, number, and location of fibroids.5 This helps us to look for structural causes and then, to get to the answer, we often use imaging such as ultrasonography or saline infusion, sometimes magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), because other conditions can coexist—endometrial polyps, adenomyosis, and so on.

The PALM-COEIN system helps us to look at 2 things. One is that in addition to structural causes, there can be hematologic causes. While it is rare in a 24-year-old, we all have had the anecdotal patient who came in 6 months ago, had a fibroid, but had a platelet count of 6,000. Second, we have to look at the patient as a whole. My residents, myself, and our fellows look at any bleeding. Does she have a bleeding diathesis, bruising, nose bleeds; has she been anemic, does she have pica? Has she had a blood transfusion, is she on certain medications? We do not want to create a “silo” and think that the patient can have only a fibroid, because then we may miss an opportunity to treat other disease states. She can have a fibroid coexisting with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), for instance. I like to look at everything so we can offer appropriate treatment modalities.

Dr. Sanfilippo: You bring up a very important point. Coagulopathies are more common statistically at the earlier part of a woman’s reproductive age group, soon after menarche, but they also occur toward menopause. We have to be cognizant that a woman can develop a coagulopathy throughout the reproductive years.

Dr. Anderson: You have to look at other medical causes. That is where the PALM-COEIN system can help. It helps you take the blinders off. If you focus on the fibroid and treat the fibroid and the patient still has bleeding, you missed something. You have to consider the whole patient and think of all the nonclassical or nonanatomical things, for example, thyroid disease. The PALM-COEIN helps us to evaluate the patient in a methodical way—every patient every time—so you do not miss something.

The value of MRI

Dr. Sanfilippo: What is the role for MRI, and when do you use it? Is it for only when you do a procedure—laparoscopically, robotically, open—so you have a detailed map of the fibroids?

Dr. Anderson: I love MRI, especially for hysteroscopy. I will print out the MRI image and trace the fibroid because there are things I want to know: exactly how much of the fibroid is inside or outside, where this fibroid is in the uterus, and how much of a normal buffer there is between the edge of that fibroid and the serosa. How aggressive can I be, or how cautious do I need to be, during the resection? Maybe this will be a planned 2-stage resection. MRIs are wonderful for fibroid disease, not only for diagnosis but also for surgical planning and patient counseling.

Dr. Bradley: SIS is also very useful. If the patient has an intracavitary fibroid that is larger than 4.5 to 5 cm and we insert the catheter, however, sometimes you cannot distend the cavity very well. Sometimes large intramural fibroids can compress the cavity, making the procedure difficult in an office setting. You cannot see the limits to help you as a surgical option. Although SIS generally is associated with little pain, some patients may have pain, and some patients cannot tolerate the test.

Continue to: I would order an MRI for surgical planning when...

I would order an MRI for surgical planning when a hysteroscopy is equivocal and if I cannot do an SIS. Also, if a patient who had a hysteroscopic resection with incomplete removal comes to me and is still symptomatic, I want to know the depth of penetration.

Obtaining an MRI may sometimes be difficult at a particular institution, and some clinicians have to go through the hurdles of getting an ultrasound to get certified and approved. We have to be our patient’s advocate and do the peer phone calls; any other specialty would require presurgical planning, and we are no different from other surgeons in that regard.

Dr. Sanfilippo: Yes, that can be a stumbling block. In the operating room, I like to have the images right in front of me, ideally an MRI or an ultrasound scan, as I know how to proceed. Having that visual helps me understand how close the fibroid is to the lining of the uterus.

Tapping into radiologists’ expertise

Dr. Bradley: Every quarter we meet with our radiologists, who are very interested in our MRI and SIS reports. They will describe the count and say how many fibroids—that is very helpful instead of just saying she has a bunch of fibroids—but they also will tell us when there is a type 0, a type 2, a type 7 fibroid. The team looks for adenomyosis and for endometriosis that can coexist.

Dr. Anderson: One caution about reading radiology reports is that often someone will come in with a report from an outside hospital or from a small community hospital that may say, “There is a 2-cm submucosal fibroid.” Some people might be tempted to take this person right to the OR, but you need to look at the images yourself, because in a radiologist’s mind “submucosal” truly means under the mucosa, which in our liturgy would be “intramural.” So we need to make sure that we are talking the same language. You should look at the images yourself.

Dr. Sanfilippo: I totally agree. It is also not unreasonable to speak with the radiologists and educate them about the FIGO classification.

Dr. Bradley: I prefer the word “intracavitary” for fibroids. When I see a typed report without the picture, “submucosal” can mean in the cavity or abutting the endometrium.

Case 2: Woman with heavy bleeding and fibroids seeks nonsurgical treatment

Dr. Sanfilippo: A 39-year-old (G3P3) woman is referred for evaluation for heavy vaginal bleeding, soaking a pad in an hour, which has been going on for months. Her primary ObGyn obtained a pelvic sonogram and noted multiple intramural and subserosal fibroids. A sonohysterogram reveals a submucosal myoma.

The patient is not interested in a hysterectomy. She was treated with birth control pills, with no improvement. She is interested in nonsurgical options. Dr. Bradley, what medical treatments might you offer this patient?

Medical treatment options

Dr. Bradley: If oral contraceptives have not worked, a good option would be tranexamic acid. Years ago our hospital was involved with enrolling patients in the multicenter clinical trial of this drug. The classic patient enrolled had regular, predictable, heavy menstrual cycles with alkaline hematin assay of greater than 80. If the case patient described has regular and predictable heavy bleeding every month at the same time, for the same duration, I would consider the use of tranexamic acid. There are several contraindications for the drug, so those exclusion issues would need to be reviewed. Contraindications include subarachnoid hemorrhage. Cerebral edema and cerebral infarction may be caused by tranexamic acid in such patients. Other contraindications include active intravascular clotting and hypersensitivity.

Continue to: Another option is to see if a progestin-releasing intrauterine system...

Another option is to see if a progestin-releasing intrauterine system (IUS) like the levonorgestrel (LNG) IUS would fit into this patient’s uterine cavity. Like Ted, I want to look into that cavity. I am not sure what “submucosal fibroid” means. If it has not distorted the cavity, or is totally within the uterine cavity, or abuts the endometrial cavity. The LNG-IUS cannot be placed into a uterine cavity that has intracavitary fibroids or sounds to greater than 12 cm. We are not going to put an LNG-IUS in somebody, at least in general, with a globally enlarged uterine cavity. I could ask, do you do that? You do a bimanual exam, and it is 18-weeks in size. I am not sure that I would put it in, but does it meet those criteria? The package insert for the LNG-IUS specifies upper and lower limits of uterine size for placement. I would start with those 2 options (tranexamic acid and LNG-IUS), and also get some more imaging.

Dr. Anderson: I agree with Linda. The submucosal fibroid could be contributing to this patient’s bleeding, but it is not the total contribution. The other fibroids may be completely irrelevant as far as her bleeding is concerned. We may need to deal with that one surgically, which we can do without a hysterectomy, most of the time.

I am a big fan of the LNG-IUS, it has been great in my experience. There are some other treatments available as well, such as gonadotropin–releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists. I tell patients that, while GnRH does work, it is not designed to be long-term therapy. If I have, for example, a 49-year-old patient, I just need to get her to menopause. Longer-term GnRH agonists might be a good option in this case. Otherwise, we could use short-term a GnRH agonist to stop the bleeding for a while so that we can reset the clock and get her started on something like levonorgestrel, tranexamic acid, or one of the other medical therapies. That may be a 2-step combination therapy.

Dr. Sanfilippo: There is a whole category of agents available—selective progesterone receptor modulators (SPRMs), pure progesterone receptor antagonists, ulipristal comes to mind. Clinicians need to know that options are available beyond birth control pills.

Dr. Anderson: As I tell patients, there are also “bridge” options. These are interventional procedures that are not hysterectomy, such as uterine fibroid embolization or endometrial ablation if bleeding is really the problem. We might consider a variety of different approaches. Obviously, we do not typically use fibroid embolization for submucosal fibroids, but it depends on how much of the fibroid is intracavitary and how big it is. Other options are a little more aggressive than medical therapy but they do not involve a hysterectomy.

Pros and cons of uterine artery embolization

Dr. Sanfilippo: If a woman desires future childbearing, is there a role for uterine artery embolization? How would you counsel her about the pros and cons?

Dr. Bradley: At the Cleveland Clinic, we generally do not offer uterine artery embolization if the patient wants a child. While it is an excellent method for treating heavy bleeding and bulk symptoms, the endometrium can be impacted. Patients can develop fistula, adhesions, or concentric narrowing, and changes in anti-Müllerian hormone levels, and there is potential for an Asherman-like syndrome and poor perfusion. I have many hysteroscopic images where the anterior wall of the uterus is nice and pink and the posterior wall is totally pale. The embolic microsphere particles can reach the endometrium—I have seen particles in the endometrium when doing a fibroid resection.

Continue to: A good early study looked at 555 women for almost a year...

A good early study looked at 555 women for almost a year.6 If women became pregnant, they had a higher rate of postpartum hemorrhage; placenta accreta, increta, and percreta; and emergent hysterectomy. It was recommended that these women deliver at a tertiary care center due to higher rates of preterm labor and malposition.

If a patient wants a baby, she should find a gynecologic surgeon who does minimally invasive laparoscopic, robotic, or open surgery, because she is more likely to have a take-home baby with a surgical approach than with embolization. In my experience, there is always going to be a patient who wants to keep her uterus at age 49 and who has every comorbidity. I might offer her the embolization just knowing what the odds of pregnancy are.

Dr. Anderson: I agree with Linda but I take a more liberal approach. Sometimes we do a myomectomy because we are trying to enhance fertility, while other times we do a myomectomy to address fibroid-related symptoms. These patients are having specific symptoms, and we want to leave the embolization option open.

If I have a patient who is 39 and becoming pregnant is not necessarily her goal, but she does not want to have a hysterectomy and if she got pregnant it would be okay, I am going to treat her a little different with respect to fibroid embolization than I would treat someone who is actively trying to have a baby. This goes back to what you were saying, let’s treat the patient, not just the fibroid.

Dr. Bradley: That is so important and sentinel. If she really does not want a hysterectomy but does not want a baby, I will ask, “Would you go through in vitro fertilization? Would you take clomiphene?” If she answers no, then I feel more comfortable, like you, with referring the patient for uterine fibroid embolization. The point is to get the patient with the right team to get the best outcomes.

Surgical approaches, intraoperative agents, and suture technique

Dr. Sanfilippo: Dr. Anderson, tell us about your surgical approaches to fibroids.

Dr. Anderson: At my institution we do have a fellowship in minimally invasive surgery, but I still do a lot of open myomectomies. I have a few guidelines to determine whether I am going to proceed laparoscopically, do a little minilaparotomy incision, or if a gigantic uterus is going to require a big incision. My mantra to my fellows has always been, “minimally invasive is the impact on the patient, not the size of the incision.”

Sometimes, prolonged anesthesia and Trendelenburg create more morbidity than a minilaparotomy. If a patient has 4 or 5 fibroids and most of them are intramural and I cannot see them but I want to be able to feel them, and to get a really good closure of the myometrium, I might choose to do a minilaparotomy. But if it is a case of a solitary fibroid, I would be more inclined to operate laparoscopically.

Continue to: Dr. Bradley...

Dr. Bradley: Our protocol is similar. We use MRI liberally. If patients have 4 or more fibroids and they are larger than 8 cm, most will have open surgery. I do not do robotic or laparoscopic procedures, so my referral source is for the larger myomas. We do not put retractors in; we can make incisions. Even if we do a huge Maylard incision, it is cosmetically wonderful. We use a loading dose of IV tranexamic acid with tranexamic acid throughout the surgery, and misoprostol intravaginally prior to surgery, to control uterine bleeding.

Dr. Sanfilippo: Dr. Anderson, is there a role for agents such as vasopressin, and what about routes of administration?

Dr. Anderson: When I do a laparoscopic or open procedure, I inject vasopressin (dilute 20 U in 100 mL of saline) into the pseudocapsule around the fibroid. I also administer rectal misoprostol (400 µg) just before the patient prep is done, which is amazing in reducing blood loss. There is also a role for a GnRH agonist, not necessarily to reduce the size of the uterus but to reduce blood flow in the pelvis and blood loss. Many different techniques are available. I do not use tourniquets, however. If bleeding does occur, I want to see it so I can fix it—not after I have sewn up the uterus and taken off a tourniquet.

Dr. Bradley: Do you use Floseal hemostatic matrix or any other agent to control bleeding?

Dr. Anderson: I do, for local hemostasis.

Dr. Bradley: Some surgeons will use barbed suture.

Dr. Anderson: I do like barbed sutures. In teaching residents to do myomectomy, it is very beneficial. But I am still a big fan of the good old figure-of-8 stitch because it is compressive and you get a good apposition of the tissue, good hemostasis, and strong closure.

Dr. Sanfilippo: We hope that this conversation will change your management of uterine fibroids. I thank Dr. Bradley and Dr. Anderson for a lively and very informative discussion.

Watch the video: Video roundtable–Fibroids: Patient considerations in medical and surgical management

- Khan AT, Shehmar M, Gupta JK. Uterine fibroids: current perspectives. Int J Womens Health. 2014;6:95-114.

- Divakars H. Asymptomatic uterine fibroids. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;22:643-654.

- Stewart EA, Nicholson WK, Bradley L, et al. The burden of uterine fibroids for African-American women: results of a national survey. J Womens Health. 2013;22:807-816.

- Hartmann KE, Velez Edwards DR, Savitz DA, et al. Prospective cohort study of uterine fibroids and miscarriage risk. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186:1140-1148.

- Munro MG, Critchley HOD, Fraser IS, for the FIGO Menstrual Disorders Working Group. The FIGO classification of causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in the reproductive years. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:2204-2208.

- Pron G, Mocarski E, Bennett J, et al; Ontario UFE Collaborative Group. Pregnancy after uterine artery embolization for leiomyomata: the Ontario multicenter trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:67-76.

- Khan AT, Shehmar M, Gupta JK. Uterine fibroids: current perspectives. Int J Womens Health. 2014;6:95-114.

- Divakars H. Asymptomatic uterine fibroids. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;22:643-654.

- Stewart EA, Nicholson WK, Bradley L, et al. The burden of uterine fibroids for African-American women: results of a national survey. J Womens Health. 2013;22:807-816.

- Hartmann KE, Velez Edwards DR, Savitz DA, et al. Prospective cohort study of uterine fibroids and miscarriage risk. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186:1140-1148.

- Munro MG, Critchley HOD, Fraser IS, for the FIGO Menstrual Disorders Working Group. The FIGO classification of causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in the reproductive years. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:2204-2208.

- Pron G, Mocarski E, Bennett J, et al; Ontario UFE Collaborative Group. Pregnancy after uterine artery embolization for leiomyomata: the Ontario multicenter trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:67-76.

Video roundtable–Fibroids: Patient considerations in medical and surgical management

Read the article: Fibroids: Patient considerations in medical and surgical management

Read the article: Fibroids: Patient considerations in medical and surgical management

Read the article: Fibroids: Patient considerations in medical and surgical management

The importance of weight management and exercise: Practical advice for your patients

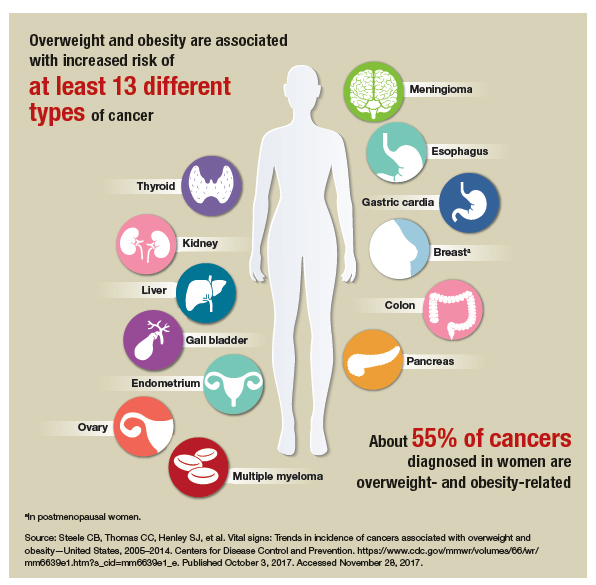

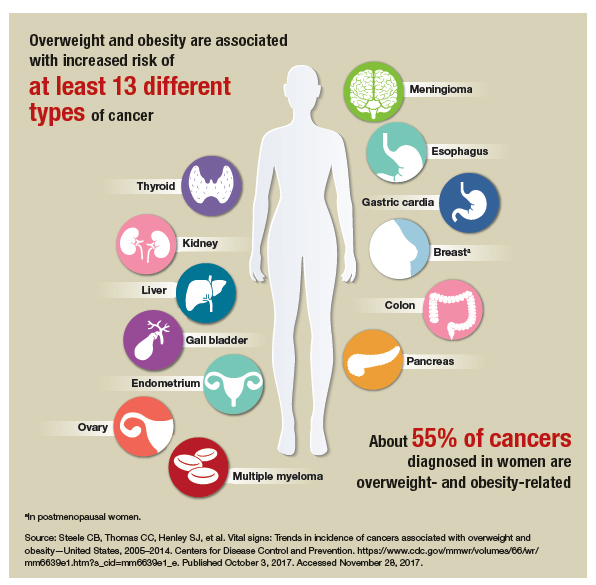

Over the past 3 decades, the prevalence of overweight and obesity has increased dramatically in the United States. A study published in 2016 showed the age-adjusted prevalence of obesity in 2013–2014 was 35% among men and 40.4% among women.1 It comes as no surprise that increased reliance on inexpensive fast foods coupled with progressively more sedentary lifestyles have been implicated as causative factors.2

With the rise in obesity also has come an attendant rise in related chronic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease. Women who are obese are also at risk for certain women’s health conditions, such as polycystic ovary syndrome, breast cancer, and endometrial cancer.

It is clear that curbing this public health crisis will require concerted efforts from individuals, clinicians, and policy makers, as well as changes in societal norms.

Linda D. Bradley, MD: I think it is important for us not to lecture our patients. I could list all of the things that patients should or could do to prevent or even reverse disease states, in terms of eating right and exercising, but I think motivational interviewing is a more productive approach to elicit and evoke change (see “Principles and practice of motivational interviewing”). I used to preach to my patients. I would say, “You know, if you stay at this weight, you’re going to get diabetes, you’re going to increase your breast cancer risk, you’re going to have abnormal bleeding, you’re not going to be able to get pregnant,” and so on. It is easy to slip into that in the 7 minutes that you have with your patient, but to me, that is not the right way.

With motivational interviewing, our interactions with patients are shaped by:

- asking

- advising

- assisting

- arranging.

We begin by asking permission: “Do you mind if we talk about your weight?” or “Can we talk about your level of exercise?” Once the patient has granted permission, we ask open-ended questions and use reflective listening: “What I hear you saying is that you are concerned you will not be able to lose the weight,” or “It sounds like you don’t like to exercise, but you are worried about the health consequences of that.”

Utilizing motivational interviewing to help patients identify thoughts and feelings that contribute to unhealthy behaviors--and replacing those thoughts and feelings with new thought patterns that aid in behavior change--has been shown to be an effective and efficient facilitator for change. By incorporating the following principles of motivational interviewing into practice, clinicians can have an important impact on the prevention or management of serious diseases in women1:

- Express empathy and avoid arguments. "I know it has been difficult for you to take the first step to losing weight. That is something that is difficult for a lot of my patients. How can I help you take that first step?"

- Develop discrepancies to help the patient understand the difference between her behavior and her goals. "You have said that you would like to lose some weight. I think you know that exercise would help with that. Why do you think it has been hard for you to start exercising more?"

- Roll with resistance and provide personalized feedback to help the patient find ways to succeed. "What I hear you saying is your work schedule does not allow you time to work out at the gym. What about walking during lunch breaks or taking the stairs instead of the elevator--is that something you think you can commit to doing?"

- Support self-efficacy and elicit self-motivation. "What would you like to see differently about your health? What makes you think you need to change? What happens if you don't change?"

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 423: Motivational interviewing: a tool for behavioral change. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(1):243-246.

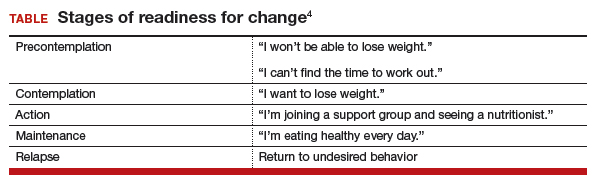

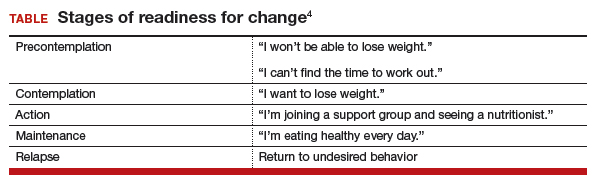

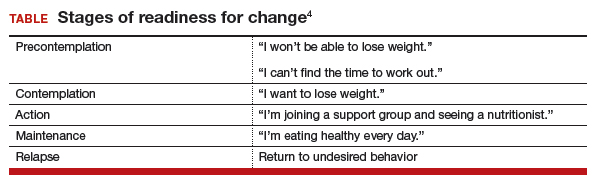

I find these skills useful for addressing anything from smoking to drinking to weight management to excessive shopping—any extreme behavior that is affecting a patient negatively. When a patient is not ready to talk about her clinical problems or make changes, I let her know my door is always open to her and that I have many resources available to help her when she is ready (TABLE).4 In those cases, I might say something like, “I have many patients who really don’t want to talk about this when I first ask them, but I just want you to know, Mrs. Jones, that I want you to succeed and I want you to be healthy. We have a team approach to taking care of all of you, and when you are ready, we are here to help.”

Related article:

2017 Update on fertility: Effects of obesity on reproduction

It is important to provide practical advice to patients—including how much to exercise, the importance of keeping a food journal, and determining a goal for slow, safe weight loss—and provide resources as necessary (such as for Weight Watchers, nutrition, and dieticians). Each day we have more than 30 opportunities to select foods to eat, drink, or purchase. Have a plan and advise your patients do the same. Recommend patients cook their own meals. Suggest weight loss apps. Counsel them to celebrate successes, find a buddy (for social support), practice positive self-talk (positive language), and plan for challenges (travel, parties, working late) and setbacks, which do not need to become a fall. Find an activity or exercise that the patient enjoys and tell them to seek professional help if needed.

Read about how to educate your patients on wellness.

Dr. Bradley: About 86% of the health care dollars spent in the United States are due to chronic diseases, and chronic diseases are the leading cause of death and disability in the country.5 The most common chronic diseases—cardiovascular disease, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, colon cancer, depression, dementia, cognitive problems, higher rates of fractures—all have been associated, at least in part, with unhealthy food choices and lack of exercise. That applies to breast cancer, too.

The good news is, we can prevent and even reverse disease. As Hippocrates said, let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food. We have all seen success stories where consistent exercise and dietary changes definitely change the paradigm for what the disease state represents. A multiplicity of factors affect poor health—noncompliance, obesity, smoking—but when we begin to make consistent, healthy changes with diet and exercise, this creates a sort of domino effect.

In the book Us! Our Life. Our Health. Our Legacy,1 co-authored by Dr. Bradley and her colleague, Margaret L. McKenzie, MD, the authors highlight the 10 healthiest behaviors to bring about youthfulness and robust health:

- Walk at least 30-45 minutes per day most days of the week.

- Engage in resistance training 2-3 days per week.

- Eat a primarily plant-based diet made up of a variety of whole foods.

- Do not smoke.

- Maintain a waist line that measures less than half your height.

- Drink alcohol only in moderation.

- Get 7-8 hours of sleep most nights.

- Forgive.

- Have gratitude.

- Believe in something greater than yourself.

- Bradley LD, McKenzie ML. Us! Our life. Our health. Our legacy. Las Vegas, Nevada: The Literary Front Publishing Co., LLC; 2016.

Dr. Bradley: I think we need to get to the root cause of these clinical problems and provide the resources and support that patients need to reverse or even prevent these diseases. Clinicians need to become more aware—be an example and a role model. Our patients are watching us as much as we are watching them. Together, we can form good partnerships in order to promote better health.

Dr. Bradley: I think when you are about to be a change agent for your body and become what I call the best version of yourself, you can have these great ideas, but you need to turn those ideas into actions and make them consistent. And we know that is difficult to do, so I do try to have patients write down specific goals, their plan for achieving them, and list the reasons why it is important for them to reach their goals. That gives them something tangible to look at when the going gets tough. It is also important to work into the contract ways to reward positive behaviors when goals are met, and to plan for challenges and setbacks and how to get back on track.