User login

The Transitions of Care Clinic: Demonstrating the Utility of the Single-Site Quality Improvement Study

A significant literature describes efforts to reduce hospital readmissions through improving care transitions. Many approaches have been tried, alone or in combination, targeting different points across the spectrum of discharge activities. These approaches encompass interventions initiated prior to discharge, such as patient education and enhanced discharge planning; bridging interventions, such as transition coaches; and postdischarge interventions, such as home visits or early follow-up appointments. Transitions of care clinics (TOCC) attempt to improve posthospital care by providing dedicated, rapid follow-up for patients after discharge.1

The impact of care transitions interventions is mixed, with inconsistent results across interventions and contexts. More complex, multipronged, context- and patient-sensitive interventions, however, are more likely to be associated with lower readmission rates.2,3

In this issue of the journal, Griffin and colleagues4 report on their TOCC implementation. Their focus on a high-risk, rural veteran population is different from prior studies, as is their use of in-person or virtual follow-up options. While the authors describe their intervention as a TOCC, their model serves as an organizer for an interprofessional team, including hospitalists, that coordinates multiple activities that complement the postdischarge appointments: identification of high-risk patients, pharmacist-led medication reconciliation, dietary counseling, contingency planning for potential changes, follow-up on pending tests and studies, and coordination of primary care and specialty care appointments. The multipronged, patient-sensitive nature of their intervention makes their positive findings consistent with other care transition literature.

Griffin and colleagues’ reporting of their TOCC experience is worth highlighting, as they present their experience and results in a way that maximizes our ability to learn from their implementation. Unfortunately, reports of improvement initiatives often lack sufficient detail regarding the context or intervention to potentially apply their findings. Griffin and colleagues applied the Revised Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE 2.0) guidelines, a standardized framework for describing improvement initiatives that captures critical contextual and intervention elements.5Griffin and colleagues describe their baseline readmission performance and how the TOCC model was relevant to this issue. They describe the context, including their patient population, and their intervention with sufficient detail for us to understand what they actually did. Importantly, Griffin and colleagues clearly delineate the dynamic phases of the implementation, their use of Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles to assess and improve their implementation, and the specific changes they made. The Figure clearly puts their results in the context of their program evolution, and their secondary outcomes support our understanding of program growth. Their use of a committee for ongoing monitoring could be important for ongoing adaptation and sustainability.

There are several limitations worth noting. There may have been subjectivity in teams’ decisions to refer specific patients with lower

In this era of multisite collaborative studies and analyses of large administrative datasets, Griffin et al4 demonstrate that there is still much to learn from a well-done, single-site improvement study.

Funding: Drs Leykum and Penney reported funding from the Department of Veterans Affairs.

1. Nall RW, Herndon BB, Mramba LK, Vogel-Anderson K, Hagen MG. An interprofessional primary care-based transition of care clinic to reduce hospital readmission. J Am Med. 2019; 133(6):E260-E268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.10.040

2. Leppin AL, Gionfriddo MR, Kessler M, et al. Preventing 30-day hospital readmissions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(7):1095-1107. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.1608

3. Pugh J, Penney LS, Noel PH, Neller S, Mader M, Finley EP, Lanham HJ, Leykum LK. Evidence-based processes to prevent readmissions: more is better, a ten-site observational study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021; 21:189. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06193-x

4. Griffin BR, Agarwal N, Amberker R, et al. An initiative to improve 30-day readmission rates using a transitions-of-care clinic among a mixed urban and rural Veteran population. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(10):583-588. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3659

5. Squire 2.0 guidelines. Accessed September 17, 2021. http://squire-statement.org

A significant literature describes efforts to reduce hospital readmissions through improving care transitions. Many approaches have been tried, alone or in combination, targeting different points across the spectrum of discharge activities. These approaches encompass interventions initiated prior to discharge, such as patient education and enhanced discharge planning; bridging interventions, such as transition coaches; and postdischarge interventions, such as home visits or early follow-up appointments. Transitions of care clinics (TOCC) attempt to improve posthospital care by providing dedicated, rapid follow-up for patients after discharge.1

The impact of care transitions interventions is mixed, with inconsistent results across interventions and contexts. More complex, multipronged, context- and patient-sensitive interventions, however, are more likely to be associated with lower readmission rates.2,3

In this issue of the journal, Griffin and colleagues4 report on their TOCC implementation. Their focus on a high-risk, rural veteran population is different from prior studies, as is their use of in-person or virtual follow-up options. While the authors describe their intervention as a TOCC, their model serves as an organizer for an interprofessional team, including hospitalists, that coordinates multiple activities that complement the postdischarge appointments: identification of high-risk patients, pharmacist-led medication reconciliation, dietary counseling, contingency planning for potential changes, follow-up on pending tests and studies, and coordination of primary care and specialty care appointments. The multipronged, patient-sensitive nature of their intervention makes their positive findings consistent with other care transition literature.

Griffin and colleagues’ reporting of their TOCC experience is worth highlighting, as they present their experience and results in a way that maximizes our ability to learn from their implementation. Unfortunately, reports of improvement initiatives often lack sufficient detail regarding the context or intervention to potentially apply their findings. Griffin and colleagues applied the Revised Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE 2.0) guidelines, a standardized framework for describing improvement initiatives that captures critical contextual and intervention elements.5Griffin and colleagues describe their baseline readmission performance and how the TOCC model was relevant to this issue. They describe the context, including their patient population, and their intervention with sufficient detail for us to understand what they actually did. Importantly, Griffin and colleagues clearly delineate the dynamic phases of the implementation, their use of Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles to assess and improve their implementation, and the specific changes they made. The Figure clearly puts their results in the context of their program evolution, and their secondary outcomes support our understanding of program growth. Their use of a committee for ongoing monitoring could be important for ongoing adaptation and sustainability.

There are several limitations worth noting. There may have been subjectivity in teams’ decisions to refer specific patients with lower

In this era of multisite collaborative studies and analyses of large administrative datasets, Griffin et al4 demonstrate that there is still much to learn from a well-done, single-site improvement study.

Funding: Drs Leykum and Penney reported funding from the Department of Veterans Affairs.

A significant literature describes efforts to reduce hospital readmissions through improving care transitions. Many approaches have been tried, alone or in combination, targeting different points across the spectrum of discharge activities. These approaches encompass interventions initiated prior to discharge, such as patient education and enhanced discharge planning; bridging interventions, such as transition coaches; and postdischarge interventions, such as home visits or early follow-up appointments. Transitions of care clinics (TOCC) attempt to improve posthospital care by providing dedicated, rapid follow-up for patients after discharge.1

The impact of care transitions interventions is mixed, with inconsistent results across interventions and contexts. More complex, multipronged, context- and patient-sensitive interventions, however, are more likely to be associated with lower readmission rates.2,3

In this issue of the journal, Griffin and colleagues4 report on their TOCC implementation. Their focus on a high-risk, rural veteran population is different from prior studies, as is their use of in-person or virtual follow-up options. While the authors describe their intervention as a TOCC, their model serves as an organizer for an interprofessional team, including hospitalists, that coordinates multiple activities that complement the postdischarge appointments: identification of high-risk patients, pharmacist-led medication reconciliation, dietary counseling, contingency planning for potential changes, follow-up on pending tests and studies, and coordination of primary care and specialty care appointments. The multipronged, patient-sensitive nature of their intervention makes their positive findings consistent with other care transition literature.

Griffin and colleagues’ reporting of their TOCC experience is worth highlighting, as they present their experience and results in a way that maximizes our ability to learn from their implementation. Unfortunately, reports of improvement initiatives often lack sufficient detail regarding the context or intervention to potentially apply their findings. Griffin and colleagues applied the Revised Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE 2.0) guidelines, a standardized framework for describing improvement initiatives that captures critical contextual and intervention elements.5Griffin and colleagues describe their baseline readmission performance and how the TOCC model was relevant to this issue. They describe the context, including their patient population, and their intervention with sufficient detail for us to understand what they actually did. Importantly, Griffin and colleagues clearly delineate the dynamic phases of the implementation, their use of Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles to assess and improve their implementation, and the specific changes they made. The Figure clearly puts their results in the context of their program evolution, and their secondary outcomes support our understanding of program growth. Their use of a committee for ongoing monitoring could be important for ongoing adaptation and sustainability.

There are several limitations worth noting. There may have been subjectivity in teams’ decisions to refer specific patients with lower

In this era of multisite collaborative studies and analyses of large administrative datasets, Griffin et al4 demonstrate that there is still much to learn from a well-done, single-site improvement study.

Funding: Drs Leykum and Penney reported funding from the Department of Veterans Affairs.

1. Nall RW, Herndon BB, Mramba LK, Vogel-Anderson K, Hagen MG. An interprofessional primary care-based transition of care clinic to reduce hospital readmission. J Am Med. 2019; 133(6):E260-E268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.10.040

2. Leppin AL, Gionfriddo MR, Kessler M, et al. Preventing 30-day hospital readmissions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(7):1095-1107. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.1608

3. Pugh J, Penney LS, Noel PH, Neller S, Mader M, Finley EP, Lanham HJ, Leykum LK. Evidence-based processes to prevent readmissions: more is better, a ten-site observational study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021; 21:189. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06193-x

4. Griffin BR, Agarwal N, Amberker R, et al. An initiative to improve 30-day readmission rates using a transitions-of-care clinic among a mixed urban and rural Veteran population. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(10):583-588. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3659

5. Squire 2.0 guidelines. Accessed September 17, 2021. http://squire-statement.org

1. Nall RW, Herndon BB, Mramba LK, Vogel-Anderson K, Hagen MG. An interprofessional primary care-based transition of care clinic to reduce hospital readmission. J Am Med. 2019; 133(6):E260-E268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.10.040

2. Leppin AL, Gionfriddo MR, Kessler M, et al. Preventing 30-day hospital readmissions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(7):1095-1107. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.1608

3. Pugh J, Penney LS, Noel PH, Neller S, Mader M, Finley EP, Lanham HJ, Leykum LK. Evidence-based processes to prevent readmissions: more is better, a ten-site observational study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021; 21:189. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06193-x

4. Griffin BR, Agarwal N, Amberker R, et al. An initiative to improve 30-day readmission rates using a transitions-of-care clinic among a mixed urban and rural Veteran population. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(10):583-588. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3659

5. Squire 2.0 guidelines. Accessed September 17, 2021. http://squire-statement.org

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Trust in a Time of Uncertainty: A Call for Articles

A functioning healthcare system requires trust on many levels. In its simplest form, this is the trust between an individual patient and their physician that allows for candor, autonomy, informed decisions, and compassionate care. Trust is a central component of medical education, as trainees gradually earn the trust of their supervisors to achieve autonomy. And, on a much larger scale, societal trust in science, the facts, and the medical system influences individual and group decisions that can have far-reaching consequences.

Defining trust is challenging. Trust is relational, an often subconscious decision “by one individual to depend on another,” but it can also be as broad as trust in an institution or a national system.1 Trust also requires vulnerability—trusting another person or system means ceding some level of personal control and accepting risk. Thus, to ask patients and society to trust in physicians, the healthcare system, or public health institutions, though essential, is no small request.

Physicians and the medical system at large have not always behaved in ways that warrant trust. Medical research on vulnerable populations (historically marginalized communities, prisoners, residents of institutions) has occurred within living memory. Systemic racism within medicine has led to marked disparities in access and outcomes between White and minoritized communities.2 These disparities have been accentuated by the pandemic. Black and Brown patients have higher infection rates and higher mortality rates but less access to healthcare.3 Vaccine distribution, which has been complicated by historic earned distrust from Black and Brown communities, revealed systemic racism. For example, many early mass vaccination sites, such as Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles, could only be easily reached by car. Online appointment scheduling platforms were opaque and required access to technology.4

Public trust in institutions has been eroding over the past several decades, but healthcare has unfortunately seen the largest decline.5 Individual healthcare decisions have also been increasingly politicized; the net result is the creation of laws, such as those limiting discussions of firearm safety or banning gender-affirming treatments for transgender children, that influence patient-physician interactions. This combination of erosion of trust and politicization of medical decisions has been harshly highlighted by the global pandemic, complicating public health policy and doctor-patient discussions. Public health measures such as masking and vaccination have become polarized.6 Further, there is diminishing trust in medical recommendations, brought about by the current media landscape and by frequent modifications to public health recommendations. Science and medicine are constantly changing, and knowledge in these fields is ultimately provisional. Unfortunately, when new data are published that contradict prior information or report new or dramatic findings, it can appear that the medical system was somehow obscuring the truth in the past, rather than simply advancing its knowledge in the present.

How do we build trust? How do we function in a healthcare system where trust has been eroded? Trust is ultimately a fragile thing. The process of earning it is not swift or straightforward, but it can be lost in a moment.

In partnership with the ABIM Foundation, the Journal of Hospital Medicine will explore the concept of trust in all facets of healthcare and medical education, including understanding the drivers of trust in a multitude of settings and in different relationships (patient-clinician, clinician-trainee, clinician- or trainee-organization, health system-community), interventions to build trust, and the enablers of those interventions. To this end, we are seeking articles that explore or evaluate trust. These include original research, brief reports, perspectives, and Leadership & Professional Development articles. Articles focusing on trust should be submitted by December 31, 2021.

1. Hendren EM, Kumagai AK. A matter of trust. Acad Med. 2019;94(9):1270-1272. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002846

2. Unaka NI, Reynolds KL. Truth in tension: reflections on racism in medicine. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(7):572-573. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3492

3. Manning KD. When grief and crises intersect: perspectives of a Black physician in the time of two pandemics. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(9):566-567. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3481

4. Dembosky A. It’s not Tuskegee. Current medical racism fuels Black Americans’ vaccine hesitancy. Los Angeles Times. March 25, 2021.

5. Lynch TJ, Wolfson DB, Baron RJ. A trust initiative in health care: why and why now? Acad Med. 2019;94(4):463-465. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002599

6. Sherling DH, Bell M. Masks, seat belts, and the politicization of public health. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(11):692-693. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3524

A functioning healthcare system requires trust on many levels. In its simplest form, this is the trust between an individual patient and their physician that allows for candor, autonomy, informed decisions, and compassionate care. Trust is a central component of medical education, as trainees gradually earn the trust of their supervisors to achieve autonomy. And, on a much larger scale, societal trust in science, the facts, and the medical system influences individual and group decisions that can have far-reaching consequences.

Defining trust is challenging. Trust is relational, an often subconscious decision “by one individual to depend on another,” but it can also be as broad as trust in an institution or a national system.1 Trust also requires vulnerability—trusting another person or system means ceding some level of personal control and accepting risk. Thus, to ask patients and society to trust in physicians, the healthcare system, or public health institutions, though essential, is no small request.

Physicians and the medical system at large have not always behaved in ways that warrant trust. Medical research on vulnerable populations (historically marginalized communities, prisoners, residents of institutions) has occurred within living memory. Systemic racism within medicine has led to marked disparities in access and outcomes between White and minoritized communities.2 These disparities have been accentuated by the pandemic. Black and Brown patients have higher infection rates and higher mortality rates but less access to healthcare.3 Vaccine distribution, which has been complicated by historic earned distrust from Black and Brown communities, revealed systemic racism. For example, many early mass vaccination sites, such as Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles, could only be easily reached by car. Online appointment scheduling platforms were opaque and required access to technology.4

Public trust in institutions has been eroding over the past several decades, but healthcare has unfortunately seen the largest decline.5 Individual healthcare decisions have also been increasingly politicized; the net result is the creation of laws, such as those limiting discussions of firearm safety or banning gender-affirming treatments for transgender children, that influence patient-physician interactions. This combination of erosion of trust and politicization of medical decisions has been harshly highlighted by the global pandemic, complicating public health policy and doctor-patient discussions. Public health measures such as masking and vaccination have become polarized.6 Further, there is diminishing trust in medical recommendations, brought about by the current media landscape and by frequent modifications to public health recommendations. Science and medicine are constantly changing, and knowledge in these fields is ultimately provisional. Unfortunately, when new data are published that contradict prior information or report new or dramatic findings, it can appear that the medical system was somehow obscuring the truth in the past, rather than simply advancing its knowledge in the present.

How do we build trust? How do we function in a healthcare system where trust has been eroded? Trust is ultimately a fragile thing. The process of earning it is not swift or straightforward, but it can be lost in a moment.

In partnership with the ABIM Foundation, the Journal of Hospital Medicine will explore the concept of trust in all facets of healthcare and medical education, including understanding the drivers of trust in a multitude of settings and in different relationships (patient-clinician, clinician-trainee, clinician- or trainee-organization, health system-community), interventions to build trust, and the enablers of those interventions. To this end, we are seeking articles that explore or evaluate trust. These include original research, brief reports, perspectives, and Leadership & Professional Development articles. Articles focusing on trust should be submitted by December 31, 2021.

A functioning healthcare system requires trust on many levels. In its simplest form, this is the trust between an individual patient and their physician that allows for candor, autonomy, informed decisions, and compassionate care. Trust is a central component of medical education, as trainees gradually earn the trust of their supervisors to achieve autonomy. And, on a much larger scale, societal trust in science, the facts, and the medical system influences individual and group decisions that can have far-reaching consequences.

Defining trust is challenging. Trust is relational, an often subconscious decision “by one individual to depend on another,” but it can also be as broad as trust in an institution or a national system.1 Trust also requires vulnerability—trusting another person or system means ceding some level of personal control and accepting risk. Thus, to ask patients and society to trust in physicians, the healthcare system, or public health institutions, though essential, is no small request.

Physicians and the medical system at large have not always behaved in ways that warrant trust. Medical research on vulnerable populations (historically marginalized communities, prisoners, residents of institutions) has occurred within living memory. Systemic racism within medicine has led to marked disparities in access and outcomes between White and minoritized communities.2 These disparities have been accentuated by the pandemic. Black and Brown patients have higher infection rates and higher mortality rates but less access to healthcare.3 Vaccine distribution, which has been complicated by historic earned distrust from Black and Brown communities, revealed systemic racism. For example, many early mass vaccination sites, such as Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles, could only be easily reached by car. Online appointment scheduling platforms were opaque and required access to technology.4

Public trust in institutions has been eroding over the past several decades, but healthcare has unfortunately seen the largest decline.5 Individual healthcare decisions have also been increasingly politicized; the net result is the creation of laws, such as those limiting discussions of firearm safety or banning gender-affirming treatments for transgender children, that influence patient-physician interactions. This combination of erosion of trust and politicization of medical decisions has been harshly highlighted by the global pandemic, complicating public health policy and doctor-patient discussions. Public health measures such as masking and vaccination have become polarized.6 Further, there is diminishing trust in medical recommendations, brought about by the current media landscape and by frequent modifications to public health recommendations. Science and medicine are constantly changing, and knowledge in these fields is ultimately provisional. Unfortunately, when new data are published that contradict prior information or report new or dramatic findings, it can appear that the medical system was somehow obscuring the truth in the past, rather than simply advancing its knowledge in the present.

How do we build trust? How do we function in a healthcare system where trust has been eroded? Trust is ultimately a fragile thing. The process of earning it is not swift or straightforward, but it can be lost in a moment.

In partnership with the ABIM Foundation, the Journal of Hospital Medicine will explore the concept of trust in all facets of healthcare and medical education, including understanding the drivers of trust in a multitude of settings and in different relationships (patient-clinician, clinician-trainee, clinician- or trainee-organization, health system-community), interventions to build trust, and the enablers of those interventions. To this end, we are seeking articles that explore or evaluate trust. These include original research, brief reports, perspectives, and Leadership & Professional Development articles. Articles focusing on trust should be submitted by December 31, 2021.

1. Hendren EM, Kumagai AK. A matter of trust. Acad Med. 2019;94(9):1270-1272. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002846

2. Unaka NI, Reynolds KL. Truth in tension: reflections on racism in medicine. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(7):572-573. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3492

3. Manning KD. When grief and crises intersect: perspectives of a Black physician in the time of two pandemics. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(9):566-567. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3481

4. Dembosky A. It’s not Tuskegee. Current medical racism fuels Black Americans’ vaccine hesitancy. Los Angeles Times. March 25, 2021.

5. Lynch TJ, Wolfson DB, Baron RJ. A trust initiative in health care: why and why now? Acad Med. 2019;94(4):463-465. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002599

6. Sherling DH, Bell M. Masks, seat belts, and the politicization of public health. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(11):692-693. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3524

1. Hendren EM, Kumagai AK. A matter of trust. Acad Med. 2019;94(9):1270-1272. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002846

2. Unaka NI, Reynolds KL. Truth in tension: reflections on racism in medicine. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(7):572-573. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3492

3. Manning KD. When grief and crises intersect: perspectives of a Black physician in the time of two pandemics. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(9):566-567. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3481

4. Dembosky A. It’s not Tuskegee. Current medical racism fuels Black Americans’ vaccine hesitancy. Los Angeles Times. March 25, 2021.

5. Lynch TJ, Wolfson DB, Baron RJ. A trust initiative in health care: why and why now? Acad Med. 2019;94(4):463-465. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002599

6. Sherling DH, Bell M. Masks, seat belts, and the politicization of public health. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(11):692-693. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3524

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Deimplementation: Discontinuing Low-Value, Potentially Harmful Hospital Care

Nearly 30% of healthcare spending may relate to overuse of unnecessary medical interventions.1 Deimplementation of such practices can reduce negative outcomes and unnecessary costs.2 Nonetheless, changing practice is difficult. Why is it so hard to stop doing things that don’t work? A variety of factors influences deimplementation, and research aiming to identify and understand these factors can promote the delivery of more appropriate care.2

In this issue, Wolk et al describe barriers and facilitators in deimplementing non-guideline adherent use of continuous pulse oximetry (CPO) in pediatric patients with bronchiolitis not requiring supplemental oxygen.3 Unnecessary CPO use for these patients is associated with increased hospitalization rates, length of stay, alarm fatigue, and costs, without evidence of improved clinical outcomes. Despite these data, many hospitals participating in the multicenter Eliminating Monitor Overuse study struggled to decrease CPO usage. The authors conducted semistructured interviews with a broad range of stakeholders from 12 hospitals, representing a variety of institutions with low and high CPO utilization rates.

Specific barriers to deimplementation included institutional factors, eg, unclear or missing guidelines, a culture of high utilization, and challenges educating medical staff. Perceived parental discomfort with stopping CPO was also observed. Four key facilitators were noted: strong institutional leadership, evidence-based guidelines, electronic health record order sets or reminders, and clear institutional policy. These results are similar to other deimplementation studies.

A commonality to deimplementation studies is the difficulty of changing practice. Much like implementation, deimplementation requires multipronged approaches that are sensitive to contextual factors. Interventions must account for local conditions, such as resource availability, practice norms, current workflows and processes of care, relationships among clinicians, and leadership, to create feasible and sustainable change.

Deimplementation may be even more challenging than implementation of new practices, however, because of loss aversion—the tendency to prefer avoiding losses to acquiring equivalent gains. “Taking away” something that clinicians are used to, even when proven to not be helpful, can feel uncomfortable, hindering adoption. Rather than simply discontinuing a practice, replacing it with a better option may help to overcome behavioral inertia and motivate change.

Underscoring the importance of local influences, clinicians often respond more to their close colleagues’ practices than to knowledge of national guidelines. Leveraging existing peer networks can facilitate collaboration, learning, and behavior change.4 Nudge strategies, in which local contexts are primed to promote desired behaviors, are also increasingly used.4 Priming has been effective in deimplementation efforts in medication prescribing and diagnostic testing.4

Including patients’ and families’ perspectives in deimplementation research is critical to practice change. Because diagnostic and treatment plans occur in the context of collaborative decision-making with patients, caregivers, and families, these groups are critical to engage in deimplementation efforts.

Hospitalists’ efforts at the front line of improvement require us to become more proficient in not only adopting evidence-based practices, but also in discontinuing ineffective ones. Identifying what we should stop doing is only the first step. Deimplementation is critical to this effort. Wolk et al provide insights into factors that influence deimplementation success. However, more work is needed, particularly regarding adapting approaches to local contexts, minimizing perceived loss, leveraging local conditions to shape behavior, and partnering with patients and families to achieve higher-value care.

1. Brownlee S, Chalkidou K, Doust J, at al. Evidence for overuse of medical services around the world. Lancet. 2017;390(10090):156-168. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32585-5

2. Norton WE, Chambers DA. Unpacking the complexities of de-implementing inappropriate health interventions. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0960-9

3. Wolk CB, Schondelmeyer AC, Barg FK, et al. Barriers and facilitators to guideline-adherent pulse oximetry use in bronchiolitis. J Hosp Med. 2021;16:23-30. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3535

4 Yoong SL, Hall A, Stacey F, et al. Nudge strategies to improve healthcare providers’ implementation of evidence-based guidelines, policies and practices: a systematic review of trials included within Cochrane systematic reviews. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-020-01011-0

Nearly 30% of healthcare spending may relate to overuse of unnecessary medical interventions.1 Deimplementation of such practices can reduce negative outcomes and unnecessary costs.2 Nonetheless, changing practice is difficult. Why is it so hard to stop doing things that don’t work? A variety of factors influences deimplementation, and research aiming to identify and understand these factors can promote the delivery of more appropriate care.2

In this issue, Wolk et al describe barriers and facilitators in deimplementing non-guideline adherent use of continuous pulse oximetry (CPO) in pediatric patients with bronchiolitis not requiring supplemental oxygen.3 Unnecessary CPO use for these patients is associated with increased hospitalization rates, length of stay, alarm fatigue, and costs, without evidence of improved clinical outcomes. Despite these data, many hospitals participating in the multicenter Eliminating Monitor Overuse study struggled to decrease CPO usage. The authors conducted semistructured interviews with a broad range of stakeholders from 12 hospitals, representing a variety of institutions with low and high CPO utilization rates.

Specific barriers to deimplementation included institutional factors, eg, unclear or missing guidelines, a culture of high utilization, and challenges educating medical staff. Perceived parental discomfort with stopping CPO was also observed. Four key facilitators were noted: strong institutional leadership, evidence-based guidelines, electronic health record order sets or reminders, and clear institutional policy. These results are similar to other deimplementation studies.

A commonality to deimplementation studies is the difficulty of changing practice. Much like implementation, deimplementation requires multipronged approaches that are sensitive to contextual factors. Interventions must account for local conditions, such as resource availability, practice norms, current workflows and processes of care, relationships among clinicians, and leadership, to create feasible and sustainable change.

Deimplementation may be even more challenging than implementation of new practices, however, because of loss aversion—the tendency to prefer avoiding losses to acquiring equivalent gains. “Taking away” something that clinicians are used to, even when proven to not be helpful, can feel uncomfortable, hindering adoption. Rather than simply discontinuing a practice, replacing it with a better option may help to overcome behavioral inertia and motivate change.

Underscoring the importance of local influences, clinicians often respond more to their close colleagues’ practices than to knowledge of national guidelines. Leveraging existing peer networks can facilitate collaboration, learning, and behavior change.4 Nudge strategies, in which local contexts are primed to promote desired behaviors, are also increasingly used.4 Priming has been effective in deimplementation efforts in medication prescribing and diagnostic testing.4

Including patients’ and families’ perspectives in deimplementation research is critical to practice change. Because diagnostic and treatment plans occur in the context of collaborative decision-making with patients, caregivers, and families, these groups are critical to engage in deimplementation efforts.

Hospitalists’ efforts at the front line of improvement require us to become more proficient in not only adopting evidence-based practices, but also in discontinuing ineffective ones. Identifying what we should stop doing is only the first step. Deimplementation is critical to this effort. Wolk et al provide insights into factors that influence deimplementation success. However, more work is needed, particularly regarding adapting approaches to local contexts, minimizing perceived loss, leveraging local conditions to shape behavior, and partnering with patients and families to achieve higher-value care.

Nearly 30% of healthcare spending may relate to overuse of unnecessary medical interventions.1 Deimplementation of such practices can reduce negative outcomes and unnecessary costs.2 Nonetheless, changing practice is difficult. Why is it so hard to stop doing things that don’t work? A variety of factors influences deimplementation, and research aiming to identify and understand these factors can promote the delivery of more appropriate care.2

In this issue, Wolk et al describe barriers and facilitators in deimplementing non-guideline adherent use of continuous pulse oximetry (CPO) in pediatric patients with bronchiolitis not requiring supplemental oxygen.3 Unnecessary CPO use for these patients is associated with increased hospitalization rates, length of stay, alarm fatigue, and costs, without evidence of improved clinical outcomes. Despite these data, many hospitals participating in the multicenter Eliminating Monitor Overuse study struggled to decrease CPO usage. The authors conducted semistructured interviews with a broad range of stakeholders from 12 hospitals, representing a variety of institutions with low and high CPO utilization rates.

Specific barriers to deimplementation included institutional factors, eg, unclear or missing guidelines, a culture of high utilization, and challenges educating medical staff. Perceived parental discomfort with stopping CPO was also observed. Four key facilitators were noted: strong institutional leadership, evidence-based guidelines, electronic health record order sets or reminders, and clear institutional policy. These results are similar to other deimplementation studies.

A commonality to deimplementation studies is the difficulty of changing practice. Much like implementation, deimplementation requires multipronged approaches that are sensitive to contextual factors. Interventions must account for local conditions, such as resource availability, practice norms, current workflows and processes of care, relationships among clinicians, and leadership, to create feasible and sustainable change.

Deimplementation may be even more challenging than implementation of new practices, however, because of loss aversion—the tendency to prefer avoiding losses to acquiring equivalent gains. “Taking away” something that clinicians are used to, even when proven to not be helpful, can feel uncomfortable, hindering adoption. Rather than simply discontinuing a practice, replacing it with a better option may help to overcome behavioral inertia and motivate change.

Underscoring the importance of local influences, clinicians often respond more to their close colleagues’ practices than to knowledge of national guidelines. Leveraging existing peer networks can facilitate collaboration, learning, and behavior change.4 Nudge strategies, in which local contexts are primed to promote desired behaviors, are also increasingly used.4 Priming has been effective in deimplementation efforts in medication prescribing and diagnostic testing.4

Including patients’ and families’ perspectives in deimplementation research is critical to practice change. Because diagnostic and treatment plans occur in the context of collaborative decision-making with patients, caregivers, and families, these groups are critical to engage in deimplementation efforts.

Hospitalists’ efforts at the front line of improvement require us to become more proficient in not only adopting evidence-based practices, but also in discontinuing ineffective ones. Identifying what we should stop doing is only the first step. Deimplementation is critical to this effort. Wolk et al provide insights into factors that influence deimplementation success. However, more work is needed, particularly regarding adapting approaches to local contexts, minimizing perceived loss, leveraging local conditions to shape behavior, and partnering with patients and families to achieve higher-value care.

1. Brownlee S, Chalkidou K, Doust J, at al. Evidence for overuse of medical services around the world. Lancet. 2017;390(10090):156-168. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32585-5

2. Norton WE, Chambers DA. Unpacking the complexities of de-implementing inappropriate health interventions. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0960-9

3. Wolk CB, Schondelmeyer AC, Barg FK, et al. Barriers and facilitators to guideline-adherent pulse oximetry use in bronchiolitis. J Hosp Med. 2021;16:23-30. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3535

4 Yoong SL, Hall A, Stacey F, et al. Nudge strategies to improve healthcare providers’ implementation of evidence-based guidelines, policies and practices: a systematic review of trials included within Cochrane systematic reviews. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-020-01011-0

1. Brownlee S, Chalkidou K, Doust J, at al. Evidence for overuse of medical services around the world. Lancet. 2017;390(10090):156-168. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32585-5

2. Norton WE, Chambers DA. Unpacking the complexities of de-implementing inappropriate health interventions. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0960-9

3. Wolk CB, Schondelmeyer AC, Barg FK, et al. Barriers and facilitators to guideline-adherent pulse oximetry use in bronchiolitis. J Hosp Med. 2021;16:23-30. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3535

4 Yoong SL, Hall A, Stacey F, et al. Nudge strategies to improve healthcare providers’ implementation of evidence-based guidelines, policies and practices: a systematic review of trials included within Cochrane systematic reviews. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-020-01011-0

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Email: [email protected];Telephone: 415-476-1742; Twitter: @shradhakulk.

Hospitalists as Triagists: Description of the Triagist Role across Academic Medical Centers

Hospital medicine has grown dramatically over the past 20 years.1,2 A recent survey regarding hospitalists’ clinical roles showed an expansion to triaging emergency department (ED) medical admissions and transfers from outside hospitals.3 From the hospitalist perspective, triaging involves the evaluation of patients for potential admission.4 With scrutiny on ED metrics, such as wait times (https://www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare/search.html), health system administrators have heightened expectations for efficient patient flow, which increasingly falls to hospitalists.5-7

Despite the growth in hospitalists’ triagist activities, there has been little formal assessment of their role. We hypothesized that this role differs from inpatient care in significant ways.6-8 We sought to describe the triagist role in adult academic inpatient medicine settings to understand the responsibilities and skill set required.

METHODS

Ten academic medical center (AMC) sites were recruited from Research Committee session attendees at the 2014 Society of Hospital Medicine national meeting and the 2014 Society of General Internal Medicine southern regional meeting. The AMCs were geographically diverse: three Western, two Midwestern, two Southern, one Northeastern, and two Southeastern. Site representatives were identified and completed a web-based questionnaire about their AMC (see Appendix 1 for the information collected). Clarifications regarding survey responses were performed via conference calls between the authors (STV, ESW) and site representatives.

Hospitalist Survey

In January 2018, surveys were sent to 583 physicians who worked as triagists. Participants received an anonymous 28-item RedCap survey by e-mail and were sent up to five reminder e-mails over six weeks (see Appendix 2 for the questions analyzed in this paper). Respondents were given the option to be entered in a gift card drawing.

Demographic information and individual workflow/practices were obtained. A 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree – strongly agree) was used to assess hospitalists’ concurrence with current providers (eg, ED, clinic providers) regarding the management and whether patients must meet the utilization management (UM) criteria for admission. Time estimates used 5% increments and were categorized into four frequency categories based on the local modes provided in responses: Seldom (0%-10%), Occasional (15%-35%), Half-the-Time (40%-60%), and Frequently (65%-100%). Free text responses on effective/ineffective triagist qualities were elicited. Responses were included for analysis if at least 70% of questions were completed.

Data Analysis

Quantitative

Descriptive statistics were calculated for each variable. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to evaluate differences across AMCs in the time spent on in-person evaluation and communication. Weighting, based on the ratio of hospitalists to survey respondents at each AMC, was used to calculate the average institutional percentages across the study sample.

Qualitative

Responses to open-ended questions were analyzed using thematic analysis.9 Three independent reviewers (STV, JC, ESW) read, analyzed, and grouped the responses by codes. Codes were then assessed for overlap and grouped into themes by one reviewer (STV). A table of themes with supporting quotes and the number of mentions was subsequently developed by all three reviewers. Similar themes were combined to create domains. The domains were reviewed by the steering committee members to create a consensus description (Appendix 3).

The University of Texas Health San Antonio’s Institutional Review Board and participating institutions approved the study as exempt.

RESULTS

Site Characteristics

Representatives from 10 AMCs reported data on a range of one to four hospitals for a total of 22 hospitals. The median reported that the number of medical patients admitted in a 24-hour period was 31-40 (range, 11-20 to >50). The median group size of hospitalists was 41-50 (range, 0-10 to >70).

The survey response rate was 40% (n = 235), ranging from 9%-70% between institutions. Self-identified female hospitalists accounted for 52% of respondents. Four percent were 25-29 years old, 66% were 30-39 years old, 24% were 40-49 years old, and 6% were ≥50 years old. The average clinical time spent as a triagist was 16%.

Description of Triagist Activities

The activities identified by the majority of respondents across all sites included transferring patients within the hospital (73%), and assessing/approving patient transfers from outside hospitals and clinics (82%). Internal transfer activities reported by >50% of respondents included allocating patients within the hospital or bed capacity coordination, assessing intensive care unit transfers, assigning ED admissions, and consulting other services. The ED accounted for an average of 55% of calls received. Respondents also reported being involved with the documentation related to these activities.

Similarities and Differences across AMCs

Two AMCs did not have a dedicated triagist; instead, physicians supervised residents and advanced practice providers. Among the eight sites with triagists, triaging was predominantly done by faculty physicians contacted via pagers. At seven of these sites, 100% of hospitalists worked as triagists. The triage service was covered by faculty physicians from 8-24 hours per day.

Bed boards and transfer centers staffed by registered nurses, nurse coordinators, house supervisors, or physicians were common support systems, though this infrastructure was organized differently across institutions. A UM review before admission was performed at three institutions 24 hours/day. The remaining institutions reviewed patients retrospectively.

Twenty-eight percent of hospitalists across all sites “Disagreed” or “Strongly disagreed” that a patient must meet UM criteria for admission. Forty-two percent had “Frequent” different opinions regarding patient management than the consulting provider.

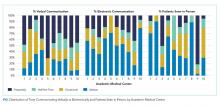

Triagist and current provider communication practices varied widely across AMCs (Figure). There was significant variability in verbal communication (P = .02), with >70% of respondents at two AMCs reporting verbal communication at least half the time, but <30% reporting this frequency at two other AMCs. Respondents reported variable use of electronic communication (ie, notes/orders in the electronic health record) across AMCs (

The practice of evaluating patients in person also varied significantly across AMCs (P < .0001, Figure). Across hospitalists, only 28% see patients in person about “Half-the-Time” or more.

Differences within AMCs

Variability within AMCs was greatest for the rate of verbal communication practices, with a typical interquartile range (IQR) of 20% to 90% among the hospitalists within a given AMC and for the rate of electronic communication with a typical IQR of 0% to 50%. For other survey questions, the IQR was typically 15 to 20 percentage points.

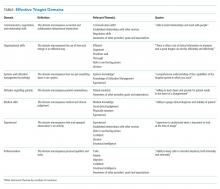

Thematic Analysis

We received 207 and 203 responses (88% and 86%, respectively) to the open-ended questions “What qualities does an effective triagist have?’ and ‘What qualities make a triagist ineffective?” We identified 22 themes for effective and ineffective qualities, which were grouped into seven domains (Table). All themes had at least three mentions by respondents. The three most frequently mentioned themes, communication skills, efficiency, and systems knowledge, had greater than 60 mentions.

DISCUSSION

Our study of the triagist role at 10 AMCs describes critical triagist functions and identifies key findings across and within AMCs. Twenty-eight percent of hospitalists reported admitting patients even when the patient did not meet the admission criteria, consistent with previous research demonstrating the influence of factors other than clinical disease severity on triage decisions.10 However, preventable admissions remain a hospital-level quality metric.11,12 Triagists must often balance each patient’s circumstances with the complexities of the system. Juggling the competing demands of the system while providing patient-centered care can be challenging and may explain why attending physicians are more frequently filling this role.13

Local context/culture is likely to play a role in the variation across sites; however, compensation for the time spent may also be a factor. If triage activities are not reimbursable, this could lead to less documentation and a lower likelihood that patients are evaluated in person.14 This reason may also explain why all hospitalists were required to serve as a triagist at most sites.

Currently, no consensus definition of the triagist role has been developed. Our results demonstrate that this role is heterogeneous and grounded in the local healthcare system practices. We propose the following working definition of the triagist: a physician who assesses patients for admission, actively supporting the transition of the patient from the outpatient to the inpatient setting. A triagist should be equipped with a skill set that includes not only clinical knowledge but also emphasizes systems knowledge, awareness of others’ goals, efficiency, an ability to communicate effectively, and the knowledge of UM. We recommend that medical directors of hospitalist programs focus their attention on locally specific, systems-based skills development when orienting new hospitalists. The financial aspects of cost should be considered and delineated as well.

Our analysis is limited in several respects. Participant AMCs were not randomly chosen, but do represent a broad array of facility types, group size, and geographic regions. The low response rates at some AMCs may result in an inaccurate representation of those sites. Data was not obtained on hospitalists that did not respond to the survey; therefore, nonresponse bias may affect outcomes. This research used self-report rather than direct observation, which could be subject to recall and social desirability bias. Finally, our results may not be generalizable to nonacademic institutions.

CONCLUSION

The hospitalist role as triagist at AMCs emphasizes communication, organizational skills, efficiency, systems-based practice, and UM knowledge. Although we found significant variation across and within AMCs, internal transfer activities were common across programs. Hospitalist programs should focus on systems-based skills development to prepare hospitalists for the role. The skill set necessary for triagist responsibilities also has implications for internal medicine resident education.4 With increasing emphasis on value and system effectiveness in care delivery, further studies of the triagist role should be undertaken.

Acknowledgments

The TRIAGIST Collaborative Group consists of: Maralyssa Bann, MD, Andrew White, MD (University of Washington); Jagriti Chadha, MD (University of Kentucky); Joel Boggan, MD (Duke University); Sherwin Hsu, MD (UCLA); Jeff Liao, MD (Harvard Medical School); Tabatha Matthias, DO (University of Nebraska Medical Center); Tresa McNeal, MD (Scott and White Texas A&M); Roxana Naderi, MD, Khooshbu Shah, MD (University of Colorado); David Schmit, MD (University of Texas Health San Antonio); Manivannan Veerasamy, MD (Michigan State University).

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the po

1. Kisuule F, Howell EE. Hospitalists and their impact on quality, patient safety, and satisfaction. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2015; 42(3):433-446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ogc.2015.05.003.

2. Wachter, RM, Goldman, L. Zero to 50,000-The 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11): 1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1607958.

3. Vasilevskis EE, Knebel RJ, Wachter RM, Auerbach AD. California hospital leaders’ views of hospitalists: meeting needs of the present and future. J Hosp Med. 2009;4:528-534. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.529.

4. Wang ES, Velásquez ST, Smith CJ, et al. Triaging inpatient admissions: an opportunity for resident education. J Gen Intern Med. 2019; 34(5):754-757. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-04882-2.

5. Briones A, Markoff B, Kathuria N, et al. A model of a hospitalist role in the care of admitted patients in the emergency department. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(6):360-364. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.636.

6. Howell EE, Bessman ES, Rubin HR. Hospitalists and an innovative emergency department admission process. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:266-268. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30431.x.

7. Howell E, Bessman E, Marshall R, Wright S. Hospitalist bed management effecting throughput from the emergency department to the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2010;25:184-189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2009.08.004.

8. Chadaga SR, Shockley L, Keniston A, et al. Hospitalist-led medicine emergency department team: associations with throughput, timeliness of patient care, and satisfaction. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:562-566. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.1957.

9. Braun, V. Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

10. Lewis Hunter AE, Spatz ES, Bernstein SL, Rosenthal MS. Factors influencing hospital admission of non-critically ill patients presenting to the emergency department: a cross-sectional study. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(1):37-44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3438-8.

11. Patel KK, Vakharia N, Pile J, Howell EH, Rothberg MB. Preventable admissions on a general medicine service: prevalence, causes and comparison with AHRQ prevention quality indicators-a cross-sectional analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(6):597-601. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3615-4.

12. Daniels LM1, Sorita A2, Kashiwagi DT, et al. Characterizing potentially preventable admissions: a mixed methods study of rates, associated factors, outcomes, and physician decision-making. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(5):737-744. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4285-6.

13. Howard-Anderson J, Lonowski S, Vangala S, Tseng CH, Busuttil A, Afsar-Manesh N. Readmissions in the era of patient engagement. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1870-1872. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4782.

14. Hinami K, Whelan CT, Miller JA, Wolosin RJ, Wetterneck TB, Society of Hospital Medicine Career Satisfaction Task Force. Job characteristics, satisfaction, and burnout across hospitalist practice models. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(5):402-410. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.1907

Hospital medicine has grown dramatically over the past 20 years.1,2 A recent survey regarding hospitalists’ clinical roles showed an expansion to triaging emergency department (ED) medical admissions and transfers from outside hospitals.3 From the hospitalist perspective, triaging involves the evaluation of patients for potential admission.4 With scrutiny on ED metrics, such as wait times (https://www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare/search.html), health system administrators have heightened expectations for efficient patient flow, which increasingly falls to hospitalists.5-7

Despite the growth in hospitalists’ triagist activities, there has been little formal assessment of their role. We hypothesized that this role differs from inpatient care in significant ways.6-8 We sought to describe the triagist role in adult academic inpatient medicine settings to understand the responsibilities and skill set required.

METHODS

Ten academic medical center (AMC) sites were recruited from Research Committee session attendees at the 2014 Society of Hospital Medicine national meeting and the 2014 Society of General Internal Medicine southern regional meeting. The AMCs were geographically diverse: three Western, two Midwestern, two Southern, one Northeastern, and two Southeastern. Site representatives were identified and completed a web-based questionnaire about their AMC (see Appendix 1 for the information collected). Clarifications regarding survey responses were performed via conference calls between the authors (STV, ESW) and site representatives.

Hospitalist Survey

In January 2018, surveys were sent to 583 physicians who worked as triagists. Participants received an anonymous 28-item RedCap survey by e-mail and were sent up to five reminder e-mails over six weeks (see Appendix 2 for the questions analyzed in this paper). Respondents were given the option to be entered in a gift card drawing.

Demographic information and individual workflow/practices were obtained. A 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree – strongly agree) was used to assess hospitalists’ concurrence with current providers (eg, ED, clinic providers) regarding the management and whether patients must meet the utilization management (UM) criteria for admission. Time estimates used 5% increments and were categorized into four frequency categories based on the local modes provided in responses: Seldom (0%-10%), Occasional (15%-35%), Half-the-Time (40%-60%), and Frequently (65%-100%). Free text responses on effective/ineffective triagist qualities were elicited. Responses were included for analysis if at least 70% of questions were completed.

Data Analysis

Quantitative

Descriptive statistics were calculated for each variable. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to evaluate differences across AMCs in the time spent on in-person evaluation and communication. Weighting, based on the ratio of hospitalists to survey respondents at each AMC, was used to calculate the average institutional percentages across the study sample.

Qualitative

Responses to open-ended questions were analyzed using thematic analysis.9 Three independent reviewers (STV, JC, ESW) read, analyzed, and grouped the responses by codes. Codes were then assessed for overlap and grouped into themes by one reviewer (STV). A table of themes with supporting quotes and the number of mentions was subsequently developed by all three reviewers. Similar themes were combined to create domains. The domains were reviewed by the steering committee members to create a consensus description (Appendix 3).

The University of Texas Health San Antonio’s Institutional Review Board and participating institutions approved the study as exempt.

RESULTS

Site Characteristics

Representatives from 10 AMCs reported data on a range of one to four hospitals for a total of 22 hospitals. The median reported that the number of medical patients admitted in a 24-hour period was 31-40 (range, 11-20 to >50). The median group size of hospitalists was 41-50 (range, 0-10 to >70).

The survey response rate was 40% (n = 235), ranging from 9%-70% between institutions. Self-identified female hospitalists accounted for 52% of respondents. Four percent were 25-29 years old, 66% were 30-39 years old, 24% were 40-49 years old, and 6% were ≥50 years old. The average clinical time spent as a triagist was 16%.

Description of Triagist Activities

The activities identified by the majority of respondents across all sites included transferring patients within the hospital (73%), and assessing/approving patient transfers from outside hospitals and clinics (82%). Internal transfer activities reported by >50% of respondents included allocating patients within the hospital or bed capacity coordination, assessing intensive care unit transfers, assigning ED admissions, and consulting other services. The ED accounted for an average of 55% of calls received. Respondents also reported being involved with the documentation related to these activities.

Similarities and Differences across AMCs

Two AMCs did not have a dedicated triagist; instead, physicians supervised residents and advanced practice providers. Among the eight sites with triagists, triaging was predominantly done by faculty physicians contacted via pagers. At seven of these sites, 100% of hospitalists worked as triagists. The triage service was covered by faculty physicians from 8-24 hours per day.

Bed boards and transfer centers staffed by registered nurses, nurse coordinators, house supervisors, or physicians were common support systems, though this infrastructure was organized differently across institutions. A UM review before admission was performed at three institutions 24 hours/day. The remaining institutions reviewed patients retrospectively.

Twenty-eight percent of hospitalists across all sites “Disagreed” or “Strongly disagreed” that a patient must meet UM criteria for admission. Forty-two percent had “Frequent” different opinions regarding patient management than the consulting provider.

Triagist and current provider communication practices varied widely across AMCs (Figure). There was significant variability in verbal communication (P = .02), with >70% of respondents at two AMCs reporting verbal communication at least half the time, but <30% reporting this frequency at two other AMCs. Respondents reported variable use of electronic communication (ie, notes/orders in the electronic health record) across AMCs (

The practice of evaluating patients in person also varied significantly across AMCs (P < .0001, Figure). Across hospitalists, only 28% see patients in person about “Half-the-Time” or more.

Differences within AMCs

Variability within AMCs was greatest for the rate of verbal communication practices, with a typical interquartile range (IQR) of 20% to 90% among the hospitalists within a given AMC and for the rate of electronic communication with a typical IQR of 0% to 50%. For other survey questions, the IQR was typically 15 to 20 percentage points.

Thematic Analysis

We received 207 and 203 responses (88% and 86%, respectively) to the open-ended questions “What qualities does an effective triagist have?’ and ‘What qualities make a triagist ineffective?” We identified 22 themes for effective and ineffective qualities, which were grouped into seven domains (Table). All themes had at least three mentions by respondents. The three most frequently mentioned themes, communication skills, efficiency, and systems knowledge, had greater than 60 mentions.

DISCUSSION

Our study of the triagist role at 10 AMCs describes critical triagist functions and identifies key findings across and within AMCs. Twenty-eight percent of hospitalists reported admitting patients even when the patient did not meet the admission criteria, consistent with previous research demonstrating the influence of factors other than clinical disease severity on triage decisions.10 However, preventable admissions remain a hospital-level quality metric.11,12 Triagists must often balance each patient’s circumstances with the complexities of the system. Juggling the competing demands of the system while providing patient-centered care can be challenging and may explain why attending physicians are more frequently filling this role.13

Local context/culture is likely to play a role in the variation across sites; however, compensation for the time spent may also be a factor. If triage activities are not reimbursable, this could lead to less documentation and a lower likelihood that patients are evaluated in person.14 This reason may also explain why all hospitalists were required to serve as a triagist at most sites.

Currently, no consensus definition of the triagist role has been developed. Our results demonstrate that this role is heterogeneous and grounded in the local healthcare system practices. We propose the following working definition of the triagist: a physician who assesses patients for admission, actively supporting the transition of the patient from the outpatient to the inpatient setting. A triagist should be equipped with a skill set that includes not only clinical knowledge but also emphasizes systems knowledge, awareness of others’ goals, efficiency, an ability to communicate effectively, and the knowledge of UM. We recommend that medical directors of hospitalist programs focus their attention on locally specific, systems-based skills development when orienting new hospitalists. The financial aspects of cost should be considered and delineated as well.

Our analysis is limited in several respects. Participant AMCs were not randomly chosen, but do represent a broad array of facility types, group size, and geographic regions. The low response rates at some AMCs may result in an inaccurate representation of those sites. Data was not obtained on hospitalists that did not respond to the survey; therefore, nonresponse bias may affect outcomes. This research used self-report rather than direct observation, which could be subject to recall and social desirability bias. Finally, our results may not be generalizable to nonacademic institutions.

CONCLUSION

The hospitalist role as triagist at AMCs emphasizes communication, organizational skills, efficiency, systems-based practice, and UM knowledge. Although we found significant variation across and within AMCs, internal transfer activities were common across programs. Hospitalist programs should focus on systems-based skills development to prepare hospitalists for the role. The skill set necessary for triagist responsibilities also has implications for internal medicine resident education.4 With increasing emphasis on value and system effectiveness in care delivery, further studies of the triagist role should be undertaken.

Acknowledgments

The TRIAGIST Collaborative Group consists of: Maralyssa Bann, MD, Andrew White, MD (University of Washington); Jagriti Chadha, MD (University of Kentucky); Joel Boggan, MD (Duke University); Sherwin Hsu, MD (UCLA); Jeff Liao, MD (Harvard Medical School); Tabatha Matthias, DO (University of Nebraska Medical Center); Tresa McNeal, MD (Scott and White Texas A&M); Roxana Naderi, MD, Khooshbu Shah, MD (University of Colorado); David Schmit, MD (University of Texas Health San Antonio); Manivannan Veerasamy, MD (Michigan State University).

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the po

Hospital medicine has grown dramatically over the past 20 years.1,2 A recent survey regarding hospitalists’ clinical roles showed an expansion to triaging emergency department (ED) medical admissions and transfers from outside hospitals.3 From the hospitalist perspective, triaging involves the evaluation of patients for potential admission.4 With scrutiny on ED metrics, such as wait times (https://www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare/search.html), health system administrators have heightened expectations for efficient patient flow, which increasingly falls to hospitalists.5-7

Despite the growth in hospitalists’ triagist activities, there has been little formal assessment of their role. We hypothesized that this role differs from inpatient care in significant ways.6-8 We sought to describe the triagist role in adult academic inpatient medicine settings to understand the responsibilities and skill set required.

METHODS

Ten academic medical center (AMC) sites were recruited from Research Committee session attendees at the 2014 Society of Hospital Medicine national meeting and the 2014 Society of General Internal Medicine southern regional meeting. The AMCs were geographically diverse: three Western, two Midwestern, two Southern, one Northeastern, and two Southeastern. Site representatives were identified and completed a web-based questionnaire about their AMC (see Appendix 1 for the information collected). Clarifications regarding survey responses were performed via conference calls between the authors (STV, ESW) and site representatives.

Hospitalist Survey

In January 2018, surveys were sent to 583 physicians who worked as triagists. Participants received an anonymous 28-item RedCap survey by e-mail and were sent up to five reminder e-mails over six weeks (see Appendix 2 for the questions analyzed in this paper). Respondents were given the option to be entered in a gift card drawing.

Demographic information and individual workflow/practices were obtained. A 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree – strongly agree) was used to assess hospitalists’ concurrence with current providers (eg, ED, clinic providers) regarding the management and whether patients must meet the utilization management (UM) criteria for admission. Time estimates used 5% increments and were categorized into four frequency categories based on the local modes provided in responses: Seldom (0%-10%), Occasional (15%-35%), Half-the-Time (40%-60%), and Frequently (65%-100%). Free text responses on effective/ineffective triagist qualities were elicited. Responses were included for analysis if at least 70% of questions were completed.

Data Analysis

Quantitative

Descriptive statistics were calculated for each variable. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to evaluate differences across AMCs in the time spent on in-person evaluation and communication. Weighting, based on the ratio of hospitalists to survey respondents at each AMC, was used to calculate the average institutional percentages across the study sample.

Qualitative

Responses to open-ended questions were analyzed using thematic analysis.9 Three independent reviewers (STV, JC, ESW) read, analyzed, and grouped the responses by codes. Codes were then assessed for overlap and grouped into themes by one reviewer (STV). A table of themes with supporting quotes and the number of mentions was subsequently developed by all three reviewers. Similar themes were combined to create domains. The domains were reviewed by the steering committee members to create a consensus description (Appendix 3).

The University of Texas Health San Antonio’s Institutional Review Board and participating institutions approved the study as exempt.

RESULTS

Site Characteristics

Representatives from 10 AMCs reported data on a range of one to four hospitals for a total of 22 hospitals. The median reported that the number of medical patients admitted in a 24-hour period was 31-40 (range, 11-20 to >50). The median group size of hospitalists was 41-50 (range, 0-10 to >70).

The survey response rate was 40% (n = 235), ranging from 9%-70% between institutions. Self-identified female hospitalists accounted for 52% of respondents. Four percent were 25-29 years old, 66% were 30-39 years old, 24% were 40-49 years old, and 6% were ≥50 years old. The average clinical time spent as a triagist was 16%.

Description of Triagist Activities

The activities identified by the majority of respondents across all sites included transferring patients within the hospital (73%), and assessing/approving patient transfers from outside hospitals and clinics (82%). Internal transfer activities reported by >50% of respondents included allocating patients within the hospital or bed capacity coordination, assessing intensive care unit transfers, assigning ED admissions, and consulting other services. The ED accounted for an average of 55% of calls received. Respondents also reported being involved with the documentation related to these activities.

Similarities and Differences across AMCs

Two AMCs did not have a dedicated triagist; instead, physicians supervised residents and advanced practice providers. Among the eight sites with triagists, triaging was predominantly done by faculty physicians contacted via pagers. At seven of these sites, 100% of hospitalists worked as triagists. The triage service was covered by faculty physicians from 8-24 hours per day.

Bed boards and transfer centers staffed by registered nurses, nurse coordinators, house supervisors, or physicians were common support systems, though this infrastructure was organized differently across institutions. A UM review before admission was performed at three institutions 24 hours/day. The remaining institutions reviewed patients retrospectively.

Twenty-eight percent of hospitalists across all sites “Disagreed” or “Strongly disagreed” that a patient must meet UM criteria for admission. Forty-two percent had “Frequent” different opinions regarding patient management than the consulting provider.

Triagist and current provider communication practices varied widely across AMCs (Figure). There was significant variability in verbal communication (P = .02), with >70% of respondents at two AMCs reporting verbal communication at least half the time, but <30% reporting this frequency at two other AMCs. Respondents reported variable use of electronic communication (ie, notes/orders in the electronic health record) across AMCs (

The practice of evaluating patients in person also varied significantly across AMCs (P < .0001, Figure). Across hospitalists, only 28% see patients in person about “Half-the-Time” or more.

Differences within AMCs

Variability within AMCs was greatest for the rate of verbal communication practices, with a typical interquartile range (IQR) of 20% to 90% among the hospitalists within a given AMC and for the rate of electronic communication with a typical IQR of 0% to 50%. For other survey questions, the IQR was typically 15 to 20 percentage points.

Thematic Analysis

We received 207 and 203 responses (88% and 86%, respectively) to the open-ended questions “What qualities does an effective triagist have?’ and ‘What qualities make a triagist ineffective?” We identified 22 themes for effective and ineffective qualities, which were grouped into seven domains (Table). All themes had at least three mentions by respondents. The three most frequently mentioned themes, communication skills, efficiency, and systems knowledge, had greater than 60 mentions.

DISCUSSION

Our study of the triagist role at 10 AMCs describes critical triagist functions and identifies key findings across and within AMCs. Twenty-eight percent of hospitalists reported admitting patients even when the patient did not meet the admission criteria, consistent with previous research demonstrating the influence of factors other than clinical disease severity on triage decisions.10 However, preventable admissions remain a hospital-level quality metric.11,12 Triagists must often balance each patient’s circumstances with the complexities of the system. Juggling the competing demands of the system while providing patient-centered care can be challenging and may explain why attending physicians are more frequently filling this role.13

Local context/culture is likely to play a role in the variation across sites; however, compensation for the time spent may also be a factor. If triage activities are not reimbursable, this could lead to less documentation and a lower likelihood that patients are evaluated in person.14 This reason may also explain why all hospitalists were required to serve as a triagist at most sites.