User login

M. Alexander Otto began his reporting career early in 1999 covering the pharmaceutical industry for a national pharmacists' magazine and freelancing for the Washington Post and other newspapers. He then joined BNA, now part of Bloomberg News, covering health law and the protection of people and animals in medical research. Alex next worked for the McClatchy Company. Based on his work, Alex won a year-long Knight Science Journalism Fellowship to MIT in 2008-2009. He joined the company shortly thereafter. Alex has a newspaper journalism degree from Syracuse (N.Y.) University and a master's degree in medical science -- a physician assistant degree -- from George Washington University. Alex is based in Seattle.

Event-Triggered Suicide Attempts by Teens Point to Lack of Problem-Solving Skills

PORTLAND, ORE. – Depressed teenagers are more likely to attempt suicide without a triggering event, and teenagers who make an attempt after an event are more likely to have poorer problem-solving skills but to be less depressed, a study has shown.

The findings suggest that when events trigger suicide attempts or ideations, adolescents might benefit most from help with problem-solving skills. In the absence of an event, teenagers might benefit more from depression treatment, according to lead author Ryan Hill, a clinical psychology graduate student at Florida International University in Miami.

"For those who didn’t have precipitating events, it may be that we need to intervene more at the level of stopping their depression. In those with preceding events, maybe we need to identify more beforehand those who have poorer problem solving and teach them some problem-solving skills," Mr. Hill said at the annual conference of the American Association of Suicidology.

Also, suicide risk should be routinely monitored among adolescents with severe depression or a past attempt, given that suicidal crises may occur in the absence of an identifiable trigger. Among youth with low levels of depression, suicide risk should be monitored closely during the days following a stressful life event, he said.

Mr. Hill and his associates interviewed 130 ethnically diverse adolescents aged 13-17, most of whom were female. The teens were hospitalized for suicide attempts or severe ideation. The investigators wanted to determine whether triggering events occurred within a week of the teenagers’ hospitalizations, and also assess their levels of depression, problem-solving skills, and impulsivity.

Consistent with rates from previous studies, 63% (82) of the teens said an event triggered their crises; it occurred within an average of 3.2 days before hospitalization.

The most common were interpersonal events – arguments with family or friends, breakups, or deaths in the family. Getting in trouble with the police or other legal problems were the second most common events. The mean impact of the events, as assessed by researchers, was 3.2, with 5 representing the most severe impact.

There were no demographic differences between teenagers who had a trigger and the 48 who did not. Impulsivity scores were similar in the two groups.

However, "those who did not have an event before their crises seemed to show more of what we would traditionally think of as the [suicide] risk factors. They had more severe depression; they were more likely to have made a past attempt; and they had greater suicidal intent if they had made an attempt. But they had better problem-solving skills," Mr. Hill said.

"Those who had an event occur before their suicidal crises had poorer problem-solving skills, but seemed to have lower levels of those other risk factors. [They had] some combination of a stressful event and poor problem solving," he said.

For example, the event group had mean problem-solving scores of 123.6. The no-event group had mean scores of 113.3, with higher scores indicating worse skills.

The event-group’s mean score on the Beck Depression Inventory was 22.4, but 28.4 in the no-event group, with a higher score indicating worse symptoms; 15% of the event group had made previous suicide attempts, compared with 29% in the no-event group.

The findings were statistically significant and indicate that "we need to consider the different ways adolescents may end up at a suicidal crisis. Only when we start to do that more broadly will we get at the best prevention programs and the best ways to reach these adolescents," Mr. Hill said.

He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

PORTLAND, ORE. – Depressed teenagers are more likely to attempt suicide without a triggering event, and teenagers who make an attempt after an event are more likely to have poorer problem-solving skills but to be less depressed, a study has shown.

The findings suggest that when events trigger suicide attempts or ideations, adolescents might benefit most from help with problem-solving skills. In the absence of an event, teenagers might benefit more from depression treatment, according to lead author Ryan Hill, a clinical psychology graduate student at Florida International University in Miami.

"For those who didn’t have precipitating events, it may be that we need to intervene more at the level of stopping their depression. In those with preceding events, maybe we need to identify more beforehand those who have poorer problem solving and teach them some problem-solving skills," Mr. Hill said at the annual conference of the American Association of Suicidology.

Also, suicide risk should be routinely monitored among adolescents with severe depression or a past attempt, given that suicidal crises may occur in the absence of an identifiable trigger. Among youth with low levels of depression, suicide risk should be monitored closely during the days following a stressful life event, he said.

Mr. Hill and his associates interviewed 130 ethnically diverse adolescents aged 13-17, most of whom were female. The teens were hospitalized for suicide attempts or severe ideation. The investigators wanted to determine whether triggering events occurred within a week of the teenagers’ hospitalizations, and also assess their levels of depression, problem-solving skills, and impulsivity.

Consistent with rates from previous studies, 63% (82) of the teens said an event triggered their crises; it occurred within an average of 3.2 days before hospitalization.

The most common were interpersonal events – arguments with family or friends, breakups, or deaths in the family. Getting in trouble with the police or other legal problems were the second most common events. The mean impact of the events, as assessed by researchers, was 3.2, with 5 representing the most severe impact.

There were no demographic differences between teenagers who had a trigger and the 48 who did not. Impulsivity scores were similar in the two groups.

However, "those who did not have an event before their crises seemed to show more of what we would traditionally think of as the [suicide] risk factors. They had more severe depression; they were more likely to have made a past attempt; and they had greater suicidal intent if they had made an attempt. But they had better problem-solving skills," Mr. Hill said.

"Those who had an event occur before their suicidal crises had poorer problem-solving skills, but seemed to have lower levels of those other risk factors. [They had] some combination of a stressful event and poor problem solving," he said.

For example, the event group had mean problem-solving scores of 123.6. The no-event group had mean scores of 113.3, with higher scores indicating worse skills.

The event-group’s mean score on the Beck Depression Inventory was 22.4, but 28.4 in the no-event group, with a higher score indicating worse symptoms; 15% of the event group had made previous suicide attempts, compared with 29% in the no-event group.

The findings were statistically significant and indicate that "we need to consider the different ways adolescents may end up at a suicidal crisis. Only when we start to do that more broadly will we get at the best prevention programs and the best ways to reach these adolescents," Mr. Hill said.

He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

PORTLAND, ORE. – Depressed teenagers are more likely to attempt suicide without a triggering event, and teenagers who make an attempt after an event are more likely to have poorer problem-solving skills but to be less depressed, a study has shown.

The findings suggest that when events trigger suicide attempts or ideations, adolescents might benefit most from help with problem-solving skills. In the absence of an event, teenagers might benefit more from depression treatment, according to lead author Ryan Hill, a clinical psychology graduate student at Florida International University in Miami.

"For those who didn’t have precipitating events, it may be that we need to intervene more at the level of stopping their depression. In those with preceding events, maybe we need to identify more beforehand those who have poorer problem solving and teach them some problem-solving skills," Mr. Hill said at the annual conference of the American Association of Suicidology.

Also, suicide risk should be routinely monitored among adolescents with severe depression or a past attempt, given that suicidal crises may occur in the absence of an identifiable trigger. Among youth with low levels of depression, suicide risk should be monitored closely during the days following a stressful life event, he said.

Mr. Hill and his associates interviewed 130 ethnically diverse adolescents aged 13-17, most of whom were female. The teens were hospitalized for suicide attempts or severe ideation. The investigators wanted to determine whether triggering events occurred within a week of the teenagers’ hospitalizations, and also assess their levels of depression, problem-solving skills, and impulsivity.

Consistent with rates from previous studies, 63% (82) of the teens said an event triggered their crises; it occurred within an average of 3.2 days before hospitalization.

The most common were interpersonal events – arguments with family or friends, breakups, or deaths in the family. Getting in trouble with the police or other legal problems were the second most common events. The mean impact of the events, as assessed by researchers, was 3.2, with 5 representing the most severe impact.

There were no demographic differences between teenagers who had a trigger and the 48 who did not. Impulsivity scores were similar in the two groups.

However, "those who did not have an event before their crises seemed to show more of what we would traditionally think of as the [suicide] risk factors. They had more severe depression; they were more likely to have made a past attempt; and they had greater suicidal intent if they had made an attempt. But they had better problem-solving skills," Mr. Hill said.

"Those who had an event occur before their suicidal crises had poorer problem-solving skills, but seemed to have lower levels of those other risk factors. [They had] some combination of a stressful event and poor problem solving," he said.

For example, the event group had mean problem-solving scores of 123.6. The no-event group had mean scores of 113.3, with higher scores indicating worse skills.

The event-group’s mean score on the Beck Depression Inventory was 22.4, but 28.4 in the no-event group, with a higher score indicating worse symptoms; 15% of the event group had made previous suicide attempts, compared with 29% in the no-event group.

The findings were statistically significant and indicate that "we need to consider the different ways adolescents may end up at a suicidal crisis. Only when we start to do that more broadly will we get at the best prevention programs and the best ways to reach these adolescents," Mr. Hill said.

He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF SUICIDOLOGY

Major Finding: A group of 82 hospitalized teenagers whose suicidal crises were triggered by events had mean problem-solving scores of 123.6; of those whose crises were not triggered by events, 48 had mean scores of 113.3, with higher scores indicating worse skills.

Data Source: Interviews with 130 adolescent psychiatric inpatients.

Disclosures: Mr. Hill said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

Event-Triggered Suicide Attempts by Teens Point to Lack of Problem-Solving Skills

PORTLAND, ORE. – Depressed teenagers are more likely to attempt suicide without a triggering event, and teenagers who make an attempt after an event are more likely to have poorer problem-solving skills but to be less depressed, a study has shown.

The findings suggest that when events trigger suicide attempts or ideations, adolescents might benefit most from help with problem-solving skills. In the absence of an event, teenagers might benefit more from depression treatment, according to lead author Ryan Hill, a clinical psychology graduate student at Florida International University in Miami.

"For those who didn’t have precipitating events, it may be that we need to intervene more at the level of stopping their depression. In those with preceding events, maybe we need to identify more beforehand those who have poorer problem solving and teach them some problem-solving skills," Mr. Hill said at the annual conference of the American Association of Suicidology.

Also, suicide risk should be routinely monitored among adolescents with severe depression or a past attempt, given that suicidal crises may occur in the absence of an identifiable trigger. Among youth with low levels of depression, suicide risk should be monitored closely during the days following a stressful life event, he said.

Mr. Hill and his associates interviewed 130 ethnically diverse adolescents aged 13-17, most of whom were female. The teens were hospitalized for suicide attempts or severe ideation. The investigators wanted to determine whether triggering events occurred within a week of the teenagers’ hospitalizations, and also assess their levels of depression, problem-solving skills, and impulsivity.

Consistent with rates from previous studies, 63% (82) of the teens said an event triggered their crises; it occurred within an average of 3.2 days before hospitalization.

The most common were interpersonal events – arguments with family or friends, breakups, or deaths in the family. Getting in trouble with the police or other legal problems were the second most common events. The mean impact of the events, as assessed by researchers, was 3.2, with 5 representing the most severe impact.

There were no demographic differences between teenagers who had a trigger and the 48 who did not. Impulsivity scores were similar in the two groups.

However, "those who did not have an event before their crises seemed to show more of what we would traditionally think of as the [suicide] risk factors. They had more severe depression; they were more likely to have made a past attempt; and they had greater suicidal intent if they had made an attempt. But they had better problem-solving skills," Mr. Hill said.

"Those who had an event occur before their suicidal crises had poorer problem-solving skills, but seemed to have lower levels of those other risk factors. [They had] some combination of a stressful event and poor problem solving," he said.

For example, the event group had mean problem-solving scores of 123.6. The no-event group had mean scores of 113.3, with higher scores indicating worse skills.

The event-group’s mean score on the Beck Depression Inventory was 22.4, but 28.4 in the no-event group, with a higher score indicating worse symptoms; 15% of the event group had made previous suicide attempts, compared with 29% in the no-event group.

The findings were statistically significant and indicate that "we need to consider the different ways adolescents may end up at a suicidal crisis. Only when we start to do that more broadly will we get at the best prevention programs and the best ways to reach these adolescents," Mr. Hill said.

He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

PORTLAND, ORE. – Depressed teenagers are more likely to attempt suicide without a triggering event, and teenagers who make an attempt after an event are more likely to have poorer problem-solving skills but to be less depressed, a study has shown.

The findings suggest that when events trigger suicide attempts or ideations, adolescents might benefit most from help with problem-solving skills. In the absence of an event, teenagers might benefit more from depression treatment, according to lead author Ryan Hill, a clinical psychology graduate student at Florida International University in Miami.

"For those who didn’t have precipitating events, it may be that we need to intervene more at the level of stopping their depression. In those with preceding events, maybe we need to identify more beforehand those who have poorer problem solving and teach them some problem-solving skills," Mr. Hill said at the annual conference of the American Association of Suicidology.

Also, suicide risk should be routinely monitored among adolescents with severe depression or a past attempt, given that suicidal crises may occur in the absence of an identifiable trigger. Among youth with low levels of depression, suicide risk should be monitored closely during the days following a stressful life event, he said.

Mr. Hill and his associates interviewed 130 ethnically diverse adolescents aged 13-17, most of whom were female. The teens were hospitalized for suicide attempts or severe ideation. The investigators wanted to determine whether triggering events occurred within a week of the teenagers’ hospitalizations, and also assess their levels of depression, problem-solving skills, and impulsivity.

Consistent with rates from previous studies, 63% (82) of the teens said an event triggered their crises; it occurred within an average of 3.2 days before hospitalization.

The most common were interpersonal events – arguments with family or friends, breakups, or deaths in the family. Getting in trouble with the police or other legal problems were the second most common events. The mean impact of the events, as assessed by researchers, was 3.2, with 5 representing the most severe impact.

There were no demographic differences between teenagers who had a trigger and the 48 who did not. Impulsivity scores were similar in the two groups.

However, "those who did not have an event before their crises seemed to show more of what we would traditionally think of as the [suicide] risk factors. They had more severe depression; they were more likely to have made a past attempt; and they had greater suicidal intent if they had made an attempt. But they had better problem-solving skills," Mr. Hill said.

"Those who had an event occur before their suicidal crises had poorer problem-solving skills, but seemed to have lower levels of those other risk factors. [They had] some combination of a stressful event and poor problem solving," he said.

For example, the event group had mean problem-solving scores of 123.6. The no-event group had mean scores of 113.3, with higher scores indicating worse skills.

The event-group’s mean score on the Beck Depression Inventory was 22.4, but 28.4 in the no-event group, with a higher score indicating worse symptoms; 15% of the event group had made previous suicide attempts, compared with 29% in the no-event group.

The findings were statistically significant and indicate that "we need to consider the different ways adolescents may end up at a suicidal crisis. Only when we start to do that more broadly will we get at the best prevention programs and the best ways to reach these adolescents," Mr. Hill said.

He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

PORTLAND, ORE. – Depressed teenagers are more likely to attempt suicide without a triggering event, and teenagers who make an attempt after an event are more likely to have poorer problem-solving skills but to be less depressed, a study has shown.

The findings suggest that when events trigger suicide attempts or ideations, adolescents might benefit most from help with problem-solving skills. In the absence of an event, teenagers might benefit more from depression treatment, according to lead author Ryan Hill, a clinical psychology graduate student at Florida International University in Miami.

"For those who didn’t have precipitating events, it may be that we need to intervene more at the level of stopping their depression. In those with preceding events, maybe we need to identify more beforehand those who have poorer problem solving and teach them some problem-solving skills," Mr. Hill said at the annual conference of the American Association of Suicidology.

Also, suicide risk should be routinely monitored among adolescents with severe depression or a past attempt, given that suicidal crises may occur in the absence of an identifiable trigger. Among youth with low levels of depression, suicide risk should be monitored closely during the days following a stressful life event, he said.

Mr. Hill and his associates interviewed 130 ethnically diverse adolescents aged 13-17, most of whom were female. The teens were hospitalized for suicide attempts or severe ideation. The investigators wanted to determine whether triggering events occurred within a week of the teenagers’ hospitalizations, and also assess their levels of depression, problem-solving skills, and impulsivity.

Consistent with rates from previous studies, 63% (82) of the teens said an event triggered their crises; it occurred within an average of 3.2 days before hospitalization.

The most common were interpersonal events – arguments with family or friends, breakups, or deaths in the family. Getting in trouble with the police or other legal problems were the second most common events. The mean impact of the events, as assessed by researchers, was 3.2, with 5 representing the most severe impact.

There were no demographic differences between teenagers who had a trigger and the 48 who did not. Impulsivity scores were similar in the two groups.

However, "those who did not have an event before their crises seemed to show more of what we would traditionally think of as the [suicide] risk factors. They had more severe depression; they were more likely to have made a past attempt; and they had greater suicidal intent if they had made an attempt. But they had better problem-solving skills," Mr. Hill said.

"Those who had an event occur before their suicidal crises had poorer problem-solving skills, but seemed to have lower levels of those other risk factors. [They had] some combination of a stressful event and poor problem solving," he said.

For example, the event group had mean problem-solving scores of 123.6. The no-event group had mean scores of 113.3, with higher scores indicating worse skills.

The event-group’s mean score on the Beck Depression Inventory was 22.4, but 28.4 in the no-event group, with a higher score indicating worse symptoms; 15% of the event group had made previous suicide attempts, compared with 29% in the no-event group.

The findings were statistically significant and indicate that "we need to consider the different ways adolescents may end up at a suicidal crisis. Only when we start to do that more broadly will we get at the best prevention programs and the best ways to reach these adolescents," Mr. Hill said.

He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF SUICIDOLOGY

Major Finding: A group of 82 hospitalized teenagers whose suicidal crises were triggered by events had mean problem-solving scores of 123.6; of those whose crises were not triggered by events, 48 had mean scores of 113.3, with higher scores indicating worse skills.

Data Source: Interviews with 130 adolescent psychiatric inpatients.

Disclosures: Mr. Hill said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

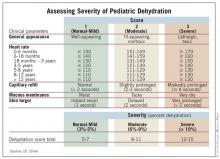

Simple Scoring System Assesses Pediatric Dehydration

DENVER – A scoring system based on five clinical parameters accurately assessed mild and moderate dehydration in children presenting to an emergency department with gastroenteritis and correlated with the need for intravenous fluids and hospital admission, according to a pilot study.

"Being able to objectively assess how dehydrated children are is really important – you don’t want to be giving children IV fluids if they don’t need them or admitting them if they don’t need it," said lead investigator Dr. Ming Chien, a pediatric emergency medicine fellow at Phoenix Children’s Hospital. "Conversely, you don’t want to be treating a child less than what they should be receiving."

But there are no robust, well-validated scoring systems for dehydration at the moment, he said said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies, so he and his colleagues decided to work on one themselves.

The system assigns a score of 1-3 to general appearance, heart rate, capillary refill, mucous membrane moisture, and skin turgor.

Those factors were picked because they have the strongest support in the medical literature, Dr. Chien noted, and they are objective. "You are not relying on [parents to tell you] the child has made wet diapers or is still making tears. You remove as much of the subjective [as possible] out of assessing children for gastroenteritis," he explained.

A capillary refill of less than 2 seconds, for example, earns a score of 1, 2-3 seconds a score of 2, and 4 or more seconds a score of 3. Similarly, skin that snaps back into place in 1 second receives a turgor score of 1, in 2 seconds a score of 2, and in more than 2 seconds a score of 3.

The scores are then added; 5-7 indicates no or mild dehydration, 8-11 indicates moderate dehydration, and 12-15 indicates severe dehydration.

To test the system’s validity, doctors and nurses weighed and scored 102 children 1 month to 15 years old who presented to the hospital’s emergency department with vomiting, diarrhea, and decreased oral intake, plus clinical concern for dehydration. Treating clinicians were blinded to the scores.

A total of 74 patients were able to return to the hospital a week later – after they had recovered – to be reweighed. The investigators assumed that those post-recovery results were the patients’ baseline weights. Comparing those assumed baseline weights to initial weights when patients first arrived at the ED, researchers were able to estimate children’s percent dehydrations when they first arrived at the ED. By percent dehydration, 64 of the 74 children had been mildly dehydrated, 9 were moderately dehydrated, and 1 was severely dehydrated.

The initial dehydration severity scores showed a statistically significant correlation with percent dehydration, though not a strong correlation. Higher scores correlated more strongly with increased likelihoods of receiving IV fluids and being admitted to the hospital, correlations that also were significant.

The scoring system is a work in progress, however. "We need bigger numbers," Dr. Chien said, as well as more severely dehydrated patients for further testing. Also, while capillary refill, skin turgor, and general appearance strongly and significantly correlated with percent dehydration, heart rate and mucous membrane moisture were less robust factors.

Even so, "the score does definitely seem to correlate with percent dehydration," he said.

Dr. Chien said he had no disclosures.

DENVER – A scoring system based on five clinical parameters accurately assessed mild and moderate dehydration in children presenting to an emergency department with gastroenteritis and correlated with the need for intravenous fluids and hospital admission, according to a pilot study.

"Being able to objectively assess how dehydrated children are is really important – you don’t want to be giving children IV fluids if they don’t need them or admitting them if they don’t need it," said lead investigator Dr. Ming Chien, a pediatric emergency medicine fellow at Phoenix Children’s Hospital. "Conversely, you don’t want to be treating a child less than what they should be receiving."

But there are no robust, well-validated scoring systems for dehydration at the moment, he said said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies, so he and his colleagues decided to work on one themselves.

The system assigns a score of 1-3 to general appearance, heart rate, capillary refill, mucous membrane moisture, and skin turgor.

Those factors were picked because they have the strongest support in the medical literature, Dr. Chien noted, and they are objective. "You are not relying on [parents to tell you] the child has made wet diapers or is still making tears. You remove as much of the subjective [as possible] out of assessing children for gastroenteritis," he explained.

A capillary refill of less than 2 seconds, for example, earns a score of 1, 2-3 seconds a score of 2, and 4 or more seconds a score of 3. Similarly, skin that snaps back into place in 1 second receives a turgor score of 1, in 2 seconds a score of 2, and in more than 2 seconds a score of 3.

The scores are then added; 5-7 indicates no or mild dehydration, 8-11 indicates moderate dehydration, and 12-15 indicates severe dehydration.

To test the system’s validity, doctors and nurses weighed and scored 102 children 1 month to 15 years old who presented to the hospital’s emergency department with vomiting, diarrhea, and decreased oral intake, plus clinical concern for dehydration. Treating clinicians were blinded to the scores.

A total of 74 patients were able to return to the hospital a week later – after they had recovered – to be reweighed. The investigators assumed that those post-recovery results were the patients’ baseline weights. Comparing those assumed baseline weights to initial weights when patients first arrived at the ED, researchers were able to estimate children’s percent dehydrations when they first arrived at the ED. By percent dehydration, 64 of the 74 children had been mildly dehydrated, 9 were moderately dehydrated, and 1 was severely dehydrated.

The initial dehydration severity scores showed a statistically significant correlation with percent dehydration, though not a strong correlation. Higher scores correlated more strongly with increased likelihoods of receiving IV fluids and being admitted to the hospital, correlations that also were significant.

The scoring system is a work in progress, however. "We need bigger numbers," Dr. Chien said, as well as more severely dehydrated patients for further testing. Also, while capillary refill, skin turgor, and general appearance strongly and significantly correlated with percent dehydration, heart rate and mucous membrane moisture were less robust factors.

Even so, "the score does definitely seem to correlate with percent dehydration," he said.

Dr. Chien said he had no disclosures.

DENVER – A scoring system based on five clinical parameters accurately assessed mild and moderate dehydration in children presenting to an emergency department with gastroenteritis and correlated with the need for intravenous fluids and hospital admission, according to a pilot study.

"Being able to objectively assess how dehydrated children are is really important – you don’t want to be giving children IV fluids if they don’t need them or admitting them if they don’t need it," said lead investigator Dr. Ming Chien, a pediatric emergency medicine fellow at Phoenix Children’s Hospital. "Conversely, you don’t want to be treating a child less than what they should be receiving."

But there are no robust, well-validated scoring systems for dehydration at the moment, he said said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies, so he and his colleagues decided to work on one themselves.

The system assigns a score of 1-3 to general appearance, heart rate, capillary refill, mucous membrane moisture, and skin turgor.

Those factors were picked because they have the strongest support in the medical literature, Dr. Chien noted, and they are objective. "You are not relying on [parents to tell you] the child has made wet diapers or is still making tears. You remove as much of the subjective [as possible] out of assessing children for gastroenteritis," he explained.

A capillary refill of less than 2 seconds, for example, earns a score of 1, 2-3 seconds a score of 2, and 4 or more seconds a score of 3. Similarly, skin that snaps back into place in 1 second receives a turgor score of 1, in 2 seconds a score of 2, and in more than 2 seconds a score of 3.

The scores are then added; 5-7 indicates no or mild dehydration, 8-11 indicates moderate dehydration, and 12-15 indicates severe dehydration.

To test the system’s validity, doctors and nurses weighed and scored 102 children 1 month to 15 years old who presented to the hospital’s emergency department with vomiting, diarrhea, and decreased oral intake, plus clinical concern for dehydration. Treating clinicians were blinded to the scores.

A total of 74 patients were able to return to the hospital a week later – after they had recovered – to be reweighed. The investigators assumed that those post-recovery results were the patients’ baseline weights. Comparing those assumed baseline weights to initial weights when patients first arrived at the ED, researchers were able to estimate children’s percent dehydrations when they first arrived at the ED. By percent dehydration, 64 of the 74 children had been mildly dehydrated, 9 were moderately dehydrated, and 1 was severely dehydrated.

The initial dehydration severity scores showed a statistically significant correlation with percent dehydration, though not a strong correlation. Higher scores correlated more strongly with increased likelihoods of receiving IV fluids and being admitted to the hospital, correlations that also were significant.

The scoring system is a work in progress, however. "We need bigger numbers," Dr. Chien said, as well as more severely dehydrated patients for further testing. Also, while capillary refill, skin turgor, and general appearance strongly and significantly correlated with percent dehydration, heart rate and mucous membrane moisture were less robust factors.

Even so, "the score does definitely seem to correlate with percent dehydration," he said.

Dr. Chien said he had no disclosures.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE PEDIATRIC ACADEMIC SOCIETIES

Major Finding: A scoring system that measured general appearance, heart rate, capillary refill, mucous membrane moisture, and skin turgor correlated with percent dehydration in 74 children presenting with gastroenteritis to an emergency department.

Data Source: Blinded, prospective pilot study.

Disclosures: Dr. Ming said he had no disclosures.

Simple Scoring System Assesses Pediatric Dehydration

DENVER – A scoring system based on five clinical parameters accurately assessed mild and moderate dehydration in children presenting to an emergency department with gastroenteritis and correlated with the need for intravenous fluids and hospital admission, according to a pilot study.

"Being able to objectively assess how dehydrated children are is really important – you don’t want to be giving children IV fluids if they don’t need them or admitting them if they don’t need it," said lead investigator Dr. Ming Chien, a pediatric emergency medicine fellow at Phoenix Children’s Hospital. "Conversely, you don’t want to be treating a child less than what they should be receiving."

But there are no robust, well-validated scoring systems for dehydration at the moment, he said said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies, so he and his colleagues decided to work on one themselves.

The system assigns a score of 1-3 to general appearance, heart rate, capillary refill, mucous membrane moisture, and skin turgor.

Those factors were picked because they have the strongest support in the medical literature, Dr. Chien noted, and they are objective. "You are not relying on [parents to tell you] the child has made wet diapers or is still making tears. You remove as much of the subjective [as possible] out of assessing children for gastroenteritis," he explained.

A capillary refill of less than 2 seconds, for example, earns a score of 1, 2-3 seconds a score of 2, and 4 or more seconds a score of 3. Similarly, skin that snaps back into place in 1 second receives a turgor score of 1, in 2 seconds a score of 2, and in more than 2 seconds a score of 3.

The scores are then added; 5-7 indicates no or mild dehydration, 8-11 indicates moderate dehydration, and 12-15 indicates severe dehydration.

To test the system’s validity, doctors and nurses weighed and scored 102 children 1 month to 15 years old who presented to the hospital’s emergency department with vomiting, diarrhea, and decreased oral intake, plus clinical concern for dehydration. Treating clinicians were blinded to the scores.

A total of 74 patients were able to return to the hospital a week later – after they had recovered – to be reweighed. The investigators assumed that those post-recovery results were the patients’ baseline weights. Comparing those assumed baseline weights to initial weights when patients first arrived at the ED, researchers were able to estimate children’s percent dehydrations when they first arrived at the ED. By percent dehydration, 64 of the 74 children had been mildly dehydrated, 9 were moderately dehydrated, and 1 was severely dehydrated.

The initial dehydration severity scores showed a statistically significant correlation with percent dehydration, though not a strong correlation. Higher scores correlated more strongly with increased likelihoods of receiving IV fluids and being admitted to the hospital, correlations that also were significant.

The scoring system is a work in progress, however. "We need bigger numbers," Dr. Chien said, as well as more severely dehydrated patients for further testing. Also, while capillary refill, skin turgor, and general appearance strongly and significantly correlated with percent dehydration, heart rate and mucous membrane moisture were less robust factors.

Even so, "the score does definitely seem to correlate with percent dehydration," he said.

Dr. Chien said he had no disclosures.

DENVER – A scoring system based on five clinical parameters accurately assessed mild and moderate dehydration in children presenting to an emergency department with gastroenteritis and correlated with the need for intravenous fluids and hospital admission, according to a pilot study.

"Being able to objectively assess how dehydrated children are is really important – you don’t want to be giving children IV fluids if they don’t need them or admitting them if they don’t need it," said lead investigator Dr. Ming Chien, a pediatric emergency medicine fellow at Phoenix Children’s Hospital. "Conversely, you don’t want to be treating a child less than what they should be receiving."

But there are no robust, well-validated scoring systems for dehydration at the moment, he said said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies, so he and his colleagues decided to work on one themselves.

The system assigns a score of 1-3 to general appearance, heart rate, capillary refill, mucous membrane moisture, and skin turgor.

Those factors were picked because they have the strongest support in the medical literature, Dr. Chien noted, and they are objective. "You are not relying on [parents to tell you] the child has made wet diapers or is still making tears. You remove as much of the subjective [as possible] out of assessing children for gastroenteritis," he explained.

A capillary refill of less than 2 seconds, for example, earns a score of 1, 2-3 seconds a score of 2, and 4 or more seconds a score of 3. Similarly, skin that snaps back into place in 1 second receives a turgor score of 1, in 2 seconds a score of 2, and in more than 2 seconds a score of 3.

The scores are then added; 5-7 indicates no or mild dehydration, 8-11 indicates moderate dehydration, and 12-15 indicates severe dehydration.

To test the system’s validity, doctors and nurses weighed and scored 102 children 1 month to 15 years old who presented to the hospital’s emergency department with vomiting, diarrhea, and decreased oral intake, plus clinical concern for dehydration. Treating clinicians were blinded to the scores.

A total of 74 patients were able to return to the hospital a week later – after they had recovered – to be reweighed. The investigators assumed that those post-recovery results were the patients’ baseline weights. Comparing those assumed baseline weights to initial weights when patients first arrived at the ED, researchers were able to estimate children’s percent dehydrations when they first arrived at the ED. By percent dehydration, 64 of the 74 children had been mildly dehydrated, 9 were moderately dehydrated, and 1 was severely dehydrated.

The initial dehydration severity scores showed a statistically significant correlation with percent dehydration, though not a strong correlation. Higher scores correlated more strongly with increased likelihoods of receiving IV fluids and being admitted to the hospital, correlations that also were significant.

The scoring system is a work in progress, however. "We need bigger numbers," Dr. Chien said, as well as more severely dehydrated patients for further testing. Also, while capillary refill, skin turgor, and general appearance strongly and significantly correlated with percent dehydration, heart rate and mucous membrane moisture were less robust factors.

Even so, "the score does definitely seem to correlate with percent dehydration," he said.

Dr. Chien said he had no disclosures.

DENVER – A scoring system based on five clinical parameters accurately assessed mild and moderate dehydration in children presenting to an emergency department with gastroenteritis and correlated with the need for intravenous fluids and hospital admission, according to a pilot study.

"Being able to objectively assess how dehydrated children are is really important – you don’t want to be giving children IV fluids if they don’t need them or admitting them if they don’t need it," said lead investigator Dr. Ming Chien, a pediatric emergency medicine fellow at Phoenix Children’s Hospital. "Conversely, you don’t want to be treating a child less than what they should be receiving."

But there are no robust, well-validated scoring systems for dehydration at the moment, he said said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies, so he and his colleagues decided to work on one themselves.

The system assigns a score of 1-3 to general appearance, heart rate, capillary refill, mucous membrane moisture, and skin turgor.

Those factors were picked because they have the strongest support in the medical literature, Dr. Chien noted, and they are objective. "You are not relying on [parents to tell you] the child has made wet diapers or is still making tears. You remove as much of the subjective [as possible] out of assessing children for gastroenteritis," he explained.

A capillary refill of less than 2 seconds, for example, earns a score of 1, 2-3 seconds a score of 2, and 4 or more seconds a score of 3. Similarly, skin that snaps back into place in 1 second receives a turgor score of 1, in 2 seconds a score of 2, and in more than 2 seconds a score of 3.

The scores are then added; 5-7 indicates no or mild dehydration, 8-11 indicates moderate dehydration, and 12-15 indicates severe dehydration.

To test the system’s validity, doctors and nurses weighed and scored 102 children 1 month to 15 years old who presented to the hospital’s emergency department with vomiting, diarrhea, and decreased oral intake, plus clinical concern for dehydration. Treating clinicians were blinded to the scores.

A total of 74 patients were able to return to the hospital a week later – after they had recovered – to be reweighed. The investigators assumed that those post-recovery results were the patients’ baseline weights. Comparing those assumed baseline weights to initial weights when patients first arrived at the ED, researchers were able to estimate children’s percent dehydrations when they first arrived at the ED. By percent dehydration, 64 of the 74 children had been mildly dehydrated, 9 were moderately dehydrated, and 1 was severely dehydrated.

The initial dehydration severity scores showed a statistically significant correlation with percent dehydration, though not a strong correlation. Higher scores correlated more strongly with increased likelihoods of receiving IV fluids and being admitted to the hospital, correlations that also were significant.

The scoring system is a work in progress, however. "We need bigger numbers," Dr. Chien said, as well as more severely dehydrated patients for further testing. Also, while capillary refill, skin turgor, and general appearance strongly and significantly correlated with percent dehydration, heart rate and mucous membrane moisture were less robust factors.

Even so, "the score does definitely seem to correlate with percent dehydration," he said.

Dr. Chien said he had no disclosures.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE PEDIATRIC ACADEMIC SOCIETIES

Prehospital Methylprednisolone May Benefit Children With Asthma Exacerbations

DENVER – If emergency workers give children with acute asthma exacerbations intravenous methylprednisolone before they reach the hospital, those children end up spending less time in the emergency department, and perhaps have shorter hospital stays if they are admitted, according to a study from the Baylor College of Medicine.

"This is something that’s been shown in adult populations to work quite well in mitigating the negative outcomes associated with asthma exacerbations," and now for the first time it’s been shown to help children, too, said the study’s lead author, Dr. David N.R. Hooke, at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

The Houston Fire Department – which handles medical emergency calls in Houston – added intravenous methylprednisolone (Solu-Medrol) to its asthma exacerbation protocol in the spring of 2008, said Dr. Hooke, a Baylor fellow in pediatric emergency medicine.

Giving IV methylprednisolone in the field for acute exacerbations isn’t something done everywhere, Dr. Hooke said, but it makes sense given the adult outcomes and also because steroids in the hospital and outpatient setting are known to shorten exacerbations.

In general, "the Houston Fire Department is very open to putting together pediatric protocols for prehospital care. The push right now is toward getting these children treated as quickly as possible," he said.

Dr. Hooke and his colleagues compared outcomes for 32 children brought to the Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, with acute asthma exacerbations during May 2007–April 2008, before the addition of IV methylprednisolone, to outcomes for 32 children brought there for the same problem during May 2008–July 2010, with the patients matched by triage acuity.

The children in the later group received 2 mg/kg of the medication 23 minutes, on average, before they arrived at hospital. Children in the earlier group received IV methylprednisolone as well, but waited an average of 84 minutes in the emergency department before getting it. Both groups received continuous albuterol by nebulizer throughout transport.

Receiving IV methylprednisolone sooner seemed to make a difference. The mean emergency department length of stay for the later group was 237 minutes, compared with 338 minutes for children treated earlier, a significant difference.

Similarly, the mean hospital length of stay was 2.2 days in the children treated after April 2008, compared with 3 days in the group treated earlier. That finding was not significant (P = .056), but did demonstrate a trend toward shorter hospital stays, Dr. Hooke said.

The study had several limitations. Because the children were matched by acuity, there was wide variation in age and gender between two groups; 22 (69%) of children in the post–protocol change group were boys, and the mean age in that group was 9.8 years. In the earlier group, 12 (38%) were boys, and the group’s mean age was 6.6.

Also, the study did not meet its target sample size, perhaps because emergency workers were slow to adopt the new protocol. "Larger sample sizes are necessary to determine the effect with greater confidence," Dr. Hooke and his colleagues concluded.

Finally, when methylprednisolone was added to the protocol, ipratropium was dropped. "There have been several research papers that have questioned the utility of ipratropium in patients younger than 12," and it’s expensive, Dr. Hooke noted.

Removing it from the protocol is a possible confounder, "but from my personal experience, I do not believe that the addition or removal of ipratropium made much difference," he said.

Even with the limitations, "the prehospital setting provides the opportunity to initiate timely treatment for asthma exacerbations," the researchers concluded.

Asthma isn’t the only target for prehospital care. "Other things can be done as well, such as getting acutely dehydrated children rehydrated either by mouth or by vein," something not often done in the field, Dr. Hooke said.

For clinicians interested in such measures, "the main thing is to form bridges with their [emergency medical services] companies and get these sorts of protocols in place," he said.

That could be problematic in some places. "A lot of cities don’t have a unified provider of services like Houston does. They have many different companies sort of doing what they want to do," making it harder for protocol changes to be widely adopted, he said.

But "if we can help children and reduce costs, it’s important, especially in the environment we practice in now," he said.

The study received no external funding. Dr. Hooke said he has no disclosures.

DENVER – If emergency workers give children with acute asthma exacerbations intravenous methylprednisolone before they reach the hospital, those children end up spending less time in the emergency department, and perhaps have shorter hospital stays if they are admitted, according to a study from the Baylor College of Medicine.

"This is something that’s been shown in adult populations to work quite well in mitigating the negative outcomes associated with asthma exacerbations," and now for the first time it’s been shown to help children, too, said the study’s lead author, Dr. David N.R. Hooke, at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

The Houston Fire Department – which handles medical emergency calls in Houston – added intravenous methylprednisolone (Solu-Medrol) to its asthma exacerbation protocol in the spring of 2008, said Dr. Hooke, a Baylor fellow in pediatric emergency medicine.

Giving IV methylprednisolone in the field for acute exacerbations isn’t something done everywhere, Dr. Hooke said, but it makes sense given the adult outcomes and also because steroids in the hospital and outpatient setting are known to shorten exacerbations.

In general, "the Houston Fire Department is very open to putting together pediatric protocols for prehospital care. The push right now is toward getting these children treated as quickly as possible," he said.

Dr. Hooke and his colleagues compared outcomes for 32 children brought to the Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, with acute asthma exacerbations during May 2007–April 2008, before the addition of IV methylprednisolone, to outcomes for 32 children brought there for the same problem during May 2008–July 2010, with the patients matched by triage acuity.

The children in the later group received 2 mg/kg of the medication 23 minutes, on average, before they arrived at hospital. Children in the earlier group received IV methylprednisolone as well, but waited an average of 84 minutes in the emergency department before getting it. Both groups received continuous albuterol by nebulizer throughout transport.

Receiving IV methylprednisolone sooner seemed to make a difference. The mean emergency department length of stay for the later group was 237 minutes, compared with 338 minutes for children treated earlier, a significant difference.

Similarly, the mean hospital length of stay was 2.2 days in the children treated after April 2008, compared with 3 days in the group treated earlier. That finding was not significant (P = .056), but did demonstrate a trend toward shorter hospital stays, Dr. Hooke said.

The study had several limitations. Because the children were matched by acuity, there was wide variation in age and gender between two groups; 22 (69%) of children in the post–protocol change group were boys, and the mean age in that group was 9.8 years. In the earlier group, 12 (38%) were boys, and the group’s mean age was 6.6.

Also, the study did not meet its target sample size, perhaps because emergency workers were slow to adopt the new protocol. "Larger sample sizes are necessary to determine the effect with greater confidence," Dr. Hooke and his colleagues concluded.

Finally, when methylprednisolone was added to the protocol, ipratropium was dropped. "There have been several research papers that have questioned the utility of ipratropium in patients younger than 12," and it’s expensive, Dr. Hooke noted.

Removing it from the protocol is a possible confounder, "but from my personal experience, I do not believe that the addition or removal of ipratropium made much difference," he said.

Even with the limitations, "the prehospital setting provides the opportunity to initiate timely treatment for asthma exacerbations," the researchers concluded.

Asthma isn’t the only target for prehospital care. "Other things can be done as well, such as getting acutely dehydrated children rehydrated either by mouth or by vein," something not often done in the field, Dr. Hooke said.

For clinicians interested in such measures, "the main thing is to form bridges with their [emergency medical services] companies and get these sorts of protocols in place," he said.

That could be problematic in some places. "A lot of cities don’t have a unified provider of services like Houston does. They have many different companies sort of doing what they want to do," making it harder for protocol changes to be widely adopted, he said.

But "if we can help children and reduce costs, it’s important, especially in the environment we practice in now," he said.

The study received no external funding. Dr. Hooke said he has no disclosures.

DENVER – If emergency workers give children with acute asthma exacerbations intravenous methylprednisolone before they reach the hospital, those children end up spending less time in the emergency department, and perhaps have shorter hospital stays if they are admitted, according to a study from the Baylor College of Medicine.

"This is something that’s been shown in adult populations to work quite well in mitigating the negative outcomes associated with asthma exacerbations," and now for the first time it’s been shown to help children, too, said the study’s lead author, Dr. David N.R. Hooke, at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

The Houston Fire Department – which handles medical emergency calls in Houston – added intravenous methylprednisolone (Solu-Medrol) to its asthma exacerbation protocol in the spring of 2008, said Dr. Hooke, a Baylor fellow in pediatric emergency medicine.

Giving IV methylprednisolone in the field for acute exacerbations isn’t something done everywhere, Dr. Hooke said, but it makes sense given the adult outcomes and also because steroids in the hospital and outpatient setting are known to shorten exacerbations.

In general, "the Houston Fire Department is very open to putting together pediatric protocols for prehospital care. The push right now is toward getting these children treated as quickly as possible," he said.

Dr. Hooke and his colleagues compared outcomes for 32 children brought to the Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, with acute asthma exacerbations during May 2007–April 2008, before the addition of IV methylprednisolone, to outcomes for 32 children brought there for the same problem during May 2008–July 2010, with the patients matched by triage acuity.

The children in the later group received 2 mg/kg of the medication 23 minutes, on average, before they arrived at hospital. Children in the earlier group received IV methylprednisolone as well, but waited an average of 84 minutes in the emergency department before getting it. Both groups received continuous albuterol by nebulizer throughout transport.

Receiving IV methylprednisolone sooner seemed to make a difference. The mean emergency department length of stay for the later group was 237 minutes, compared with 338 minutes for children treated earlier, a significant difference.

Similarly, the mean hospital length of stay was 2.2 days in the children treated after April 2008, compared with 3 days in the group treated earlier. That finding was not significant (P = .056), but did demonstrate a trend toward shorter hospital stays, Dr. Hooke said.

The study had several limitations. Because the children were matched by acuity, there was wide variation in age and gender between two groups; 22 (69%) of children in the post–protocol change group were boys, and the mean age in that group was 9.8 years. In the earlier group, 12 (38%) were boys, and the group’s mean age was 6.6.

Also, the study did not meet its target sample size, perhaps because emergency workers were slow to adopt the new protocol. "Larger sample sizes are necessary to determine the effect with greater confidence," Dr. Hooke and his colleagues concluded.

Finally, when methylprednisolone was added to the protocol, ipratropium was dropped. "There have been several research papers that have questioned the utility of ipratropium in patients younger than 12," and it’s expensive, Dr. Hooke noted.

Removing it from the protocol is a possible confounder, "but from my personal experience, I do not believe that the addition or removal of ipratropium made much difference," he said.

Even with the limitations, "the prehospital setting provides the opportunity to initiate timely treatment for asthma exacerbations," the researchers concluded.

Asthma isn’t the only target for prehospital care. "Other things can be done as well, such as getting acutely dehydrated children rehydrated either by mouth or by vein," something not often done in the field, Dr. Hooke said.

For clinicians interested in such measures, "the main thing is to form bridges with their [emergency medical services] companies and get these sorts of protocols in place," he said.

That could be problematic in some places. "A lot of cities don’t have a unified provider of services like Houston does. They have many different companies sort of doing what they want to do," making it harder for protocol changes to be widely adopted, he said.

But "if we can help children and reduce costs, it’s important, especially in the environment we practice in now," he said.

The study received no external funding. Dr. Hooke said he has no disclosures.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE PEDIATRIC ACADEMIC SOCIETIES

Major Finding: Children with acute asthma exacerbations who received IV methylprednisolone before reaching the hospital spent an average of 237 minutes in the ED; those who did not spent 338 minutes, a significant difference.

Data Source: Retrospective case-control study of children with acute asthma brought to one hospital: 32 received IV methylprednisolone en route and 32 did not.

Disclosures: The study received no external funding. Dr. Hooke said he has no disclosures.

Secondhand Smoke Raised Boys' Blood Pressure

DENVER – There’s a new reason to keep children away from secondhand smoke: It raises systolic blood pressure in boys, a University of Wisconsin, Madison, study suggests.

However, the mean increase was minimal – just 1.6 mm Hg – when researchers compared boys exposed to secondhand smoke with those who were not. "For an individual child, that’s not necessarily something you would worry about" in the short term, lead investigator and environmental health research fellow Jill Baumgartner, Ph.D., said the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Still, elevated blood pressure in childhood can lead to adult hypertension and, "We found a similar [blood pressure] effect for children exposed to really low levels as for children exposed to higher levels, [reinforcing] the notion that there really is no acceptable exposure level for secondhand smoke," she said.

The study by Dr. Baumgartner and her colleagues is the first to demonstrate a link between secondhand smoke and blood pressure changes in children. Secondhand smoke already is known to decrease lung growth, increase the risk for sudden infant death, and cause respiratory problems in children, among other factors.

Conversely, however, Dr. Baumgartner and her colleagues also discovered that girls exposed to secondhand smoke had slightly lower systolic blood pressure than did other girls, a mean of 1.8 mm Hg.

"I think there could be something going on there, but we are not sure what it is," she said. "It’s actually supported in the academic literature" that smoking raises blood pressure in males but can have the opposite effect in females.

She hesitated to call female gender a protective factor, because the drop in blood pressure could signal some other deleterious effect of smoke exposure.

In their cross-sectional retrospective analysis, the researchers mined National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data from 1999-2006, identifying 6,421 children aged 8-17, 52% girls, 34% white, 27% Mexican American, and about 32% exposed to secondhand smoke.

They defined exposure as having at least one smoker in the house and by serum cotinine levels of 0.01-14 ng/mL. Children with levels above 14 ng/mL were excluded because that level of the nicotine metabolite indicates that they themselves smoke. Having a smoker in the house strongly correlated with cotinine levels.

Through matching and statistical adjustments, the researchers controlled for a range of confounding variables, including age, sex, body mass index, physical activity, survey year, health insurance, household income, and potassium, caffeine, and sodium intake.

There was no dose-response relationship between cotinine levels and blood pressure. Elevations were similar in boys and drops similar in girls across cotinine levels. In exposed boys, increases in systolic blood pressure ranged from 1-1.9 mm Hg. In exposed girls, drops ranged from 1.5-2.6 mmHg. Results were statistically significant.

"If you looked at higher doses, you might see a dose response, but in this range of exposure, because it’s so low" it wasn’t apparent, Dr. Baumgartner said.

The next step is a longitudinal study to see whether blood pressure changes vary with variations in secondhand smoke exposure. "We are also trying to better understand the biologic drivers of tobacco smoke and blood pressure in kids," she said.

In the meantime, "If you are physician and have a parent coming in saying ‘I am reducing the amount I’m smoking,’ we are showing that’s not quite enough. [They] need to stop smoking, because even at really low levels, exposure is having an effect on kids and their blood pressure," she said.

Dr. Baumgartner said she has no disclosures. The study was funded by an Academic Pediatric Association Young Investigators Grant.

DENVER – There’s a new reason to keep children away from secondhand smoke: It raises systolic blood pressure in boys, a University of Wisconsin, Madison, study suggests.

However, the mean increase was minimal – just 1.6 mm Hg – when researchers compared boys exposed to secondhand smoke with those who were not. "For an individual child, that’s not necessarily something you would worry about" in the short term, lead investigator and environmental health research fellow Jill Baumgartner, Ph.D., said the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Still, elevated blood pressure in childhood can lead to adult hypertension and, "We found a similar [blood pressure] effect for children exposed to really low levels as for children exposed to higher levels, [reinforcing] the notion that there really is no acceptable exposure level for secondhand smoke," she said.

The study by Dr. Baumgartner and her colleagues is the first to demonstrate a link between secondhand smoke and blood pressure changes in children. Secondhand smoke already is known to decrease lung growth, increase the risk for sudden infant death, and cause respiratory problems in children, among other factors.

Conversely, however, Dr. Baumgartner and her colleagues also discovered that girls exposed to secondhand smoke had slightly lower systolic blood pressure than did other girls, a mean of 1.8 mm Hg.

"I think there could be something going on there, but we are not sure what it is," she said. "It’s actually supported in the academic literature" that smoking raises blood pressure in males but can have the opposite effect in females.

She hesitated to call female gender a protective factor, because the drop in blood pressure could signal some other deleterious effect of smoke exposure.

In their cross-sectional retrospective analysis, the researchers mined National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data from 1999-2006, identifying 6,421 children aged 8-17, 52% girls, 34% white, 27% Mexican American, and about 32% exposed to secondhand smoke.

They defined exposure as having at least one smoker in the house and by serum cotinine levels of 0.01-14 ng/mL. Children with levels above 14 ng/mL were excluded because that level of the nicotine metabolite indicates that they themselves smoke. Having a smoker in the house strongly correlated with cotinine levels.

Through matching and statistical adjustments, the researchers controlled for a range of confounding variables, including age, sex, body mass index, physical activity, survey year, health insurance, household income, and potassium, caffeine, and sodium intake.

There was no dose-response relationship between cotinine levels and blood pressure. Elevations were similar in boys and drops similar in girls across cotinine levels. In exposed boys, increases in systolic blood pressure ranged from 1-1.9 mm Hg. In exposed girls, drops ranged from 1.5-2.6 mmHg. Results were statistically significant.

"If you looked at higher doses, you might see a dose response, but in this range of exposure, because it’s so low" it wasn’t apparent, Dr. Baumgartner said.

The next step is a longitudinal study to see whether blood pressure changes vary with variations in secondhand smoke exposure. "We are also trying to better understand the biologic drivers of tobacco smoke and blood pressure in kids," she said.

In the meantime, "If you are physician and have a parent coming in saying ‘I am reducing the amount I’m smoking,’ we are showing that’s not quite enough. [They] need to stop smoking, because even at really low levels, exposure is having an effect on kids and their blood pressure," she said.

Dr. Baumgartner said she has no disclosures. The study was funded by an Academic Pediatric Association Young Investigators Grant.

DENVER – There’s a new reason to keep children away from secondhand smoke: It raises systolic blood pressure in boys, a University of Wisconsin, Madison, study suggests.

However, the mean increase was minimal – just 1.6 mm Hg – when researchers compared boys exposed to secondhand smoke with those who were not. "For an individual child, that’s not necessarily something you would worry about" in the short term, lead investigator and environmental health research fellow Jill Baumgartner, Ph.D., said the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

Still, elevated blood pressure in childhood can lead to adult hypertension and, "We found a similar [blood pressure] effect for children exposed to really low levels as for children exposed to higher levels, [reinforcing] the notion that there really is no acceptable exposure level for secondhand smoke," she said.

The study by Dr. Baumgartner and her colleagues is the first to demonstrate a link between secondhand smoke and blood pressure changes in children. Secondhand smoke already is known to decrease lung growth, increase the risk for sudden infant death, and cause respiratory problems in children, among other factors.

Conversely, however, Dr. Baumgartner and her colleagues also discovered that girls exposed to secondhand smoke had slightly lower systolic blood pressure than did other girls, a mean of 1.8 mm Hg.

"I think there could be something going on there, but we are not sure what it is," she said. "It’s actually supported in the academic literature" that smoking raises blood pressure in males but can have the opposite effect in females.

She hesitated to call female gender a protective factor, because the drop in blood pressure could signal some other deleterious effect of smoke exposure.

In their cross-sectional retrospective analysis, the researchers mined National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data from 1999-2006, identifying 6,421 children aged 8-17, 52% girls, 34% white, 27% Mexican American, and about 32% exposed to secondhand smoke.

They defined exposure as having at least one smoker in the house and by serum cotinine levels of 0.01-14 ng/mL. Children with levels above 14 ng/mL were excluded because that level of the nicotine metabolite indicates that they themselves smoke. Having a smoker in the house strongly correlated with cotinine levels.

Through matching and statistical adjustments, the researchers controlled for a range of confounding variables, including age, sex, body mass index, physical activity, survey year, health insurance, household income, and potassium, caffeine, and sodium intake.

There was no dose-response relationship between cotinine levels and blood pressure. Elevations were similar in boys and drops similar in girls across cotinine levels. In exposed boys, increases in systolic blood pressure ranged from 1-1.9 mm Hg. In exposed girls, drops ranged from 1.5-2.6 mmHg. Results were statistically significant.

"If you looked at higher doses, you might see a dose response, but in this range of exposure, because it’s so low" it wasn’t apparent, Dr. Baumgartner said.

The next step is a longitudinal study to see whether blood pressure changes vary with variations in secondhand smoke exposure. "We are also trying to better understand the biologic drivers of tobacco smoke and blood pressure in kids," she said.

In the meantime, "If you are physician and have a parent coming in saying ‘I am reducing the amount I’m smoking,’ we are showing that’s not quite enough. [They] need to stop smoking, because even at really low levels, exposure is having an effect on kids and their blood pressure," she said.

Dr. Baumgartner said she has no disclosures. The study was funded by an Academic Pediatric Association Young Investigators Grant.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE PEDIATRIC ACADEMIC SOCIETIES

Major Finding: Exposure to secondhand smoke increases the blood pressure of boys aged 8-17 by a mean of 1.6 mm Hg.

Data Source: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

Disclosures: Dr. Baumgartner said she has no disclosures. The study was funded by an Academic Pediatric Association Young Investigators Grant.

Keep Antiplatelet Interruptions as Brief as Possible

HUNTINGTON BEACH, CALIF. – Patients with recently placed coronary stents who are on clopidogrel may need to discontinue the drug to prevent excessive bleeding during surgery, but it should be restarted as soon as possible, according to Dr. Alan Dardik.

Continuing antiplatelet therapy during the perioperative period is crucial, he noted, because “the risk of surgical bleeding, if dual-antiplatelet therapy is continued, is actually lower than the risk of coronary thrombosis due to agent withdrawal.”

Antiplatelet drugs pose a considerable bleeding risk: Aspirin can increase surgical blood loss up to 20%, and dual therapy up to 50%. According to Dr. Dardik, however, although “many studies show a small increase in complications from this bleeding, particularly increased transfusions, no study has actually shown an increase in mortality.”

Meanwhile, the risk of a fatal myocardial infarction is high when antiplatelet therapy is withdrawn, especially within 6 weeks of stent placement. The risk is especially high in patients with cancer, diabetes, and other hypercoagulable states, and in those with long, multiple, or overlapping stents, Dr. Dardik said.

“Keep the nontherapeutic window short, from about 3 days before the surgery to 1-2 days afterward, [and] reload [patients] at high risk for thrombosis with 300 mg of clopidogrel,” Dr. Dardik said at the meeting.

Since dual-antiplatelet therapy is standard for 6 months following stent placement, patients on clopidogrel (Plavix) will almost certainly also be on aspirin. To offset the temporary loss of clopidogrel, he recommended increasing the aspirin dose, said Dr. Dardik, a vascular surgeon at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The best option for recently stented patients is to postpone surgery for at least 6 months – the point at which dual-antiplatelet therapy can be stopped – or even a year, when aspirin can also cease. When that's not possible, Dr. Dardik recommends performing a less invasive procedure, with easier hemostasis.

He said he has no relevant disclosures.

HUNTINGTON BEACH, CALIF. – Patients with recently placed coronary stents who are on clopidogrel may need to discontinue the drug to prevent excessive bleeding during surgery, but it should be restarted as soon as possible, according to Dr. Alan Dardik.

Continuing antiplatelet therapy during the perioperative period is crucial, he noted, because “the risk of surgical bleeding, if dual-antiplatelet therapy is continued, is actually lower than the risk of coronary thrombosis due to agent withdrawal.”

Antiplatelet drugs pose a considerable bleeding risk: Aspirin can increase surgical blood loss up to 20%, and dual therapy up to 50%. According to Dr. Dardik, however, although “many studies show a small increase in complications from this bleeding, particularly increased transfusions, no study has actually shown an increase in mortality.”

Meanwhile, the risk of a fatal myocardial infarction is high when antiplatelet therapy is withdrawn, especially within 6 weeks of stent placement. The risk is especially high in patients with cancer, diabetes, and other hypercoagulable states, and in those with long, multiple, or overlapping stents, Dr. Dardik said.

“Keep the nontherapeutic window short, from about 3 days before the surgery to 1-2 days afterward, [and] reload [patients] at high risk for thrombosis with 300 mg of clopidogrel,” Dr. Dardik said at the meeting.

Since dual-antiplatelet therapy is standard for 6 months following stent placement, patients on clopidogrel (Plavix) will almost certainly also be on aspirin. To offset the temporary loss of clopidogrel, he recommended increasing the aspirin dose, said Dr. Dardik, a vascular surgeon at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The best option for recently stented patients is to postpone surgery for at least 6 months – the point at which dual-antiplatelet therapy can be stopped – or even a year, when aspirin can also cease. When that's not possible, Dr. Dardik recommends performing a less invasive procedure, with easier hemostasis.

He said he has no relevant disclosures.

HUNTINGTON BEACH, CALIF. – Patients with recently placed coronary stents who are on clopidogrel may need to discontinue the drug to prevent excessive bleeding during surgery, but it should be restarted as soon as possible, according to Dr. Alan Dardik.

Continuing antiplatelet therapy during the perioperative period is crucial, he noted, because “the risk of surgical bleeding, if dual-antiplatelet therapy is continued, is actually lower than the risk of coronary thrombosis due to agent withdrawal.”

Antiplatelet drugs pose a considerable bleeding risk: Aspirin can increase surgical blood loss up to 20%, and dual therapy up to 50%. According to Dr. Dardik, however, although “many studies show a small increase in complications from this bleeding, particularly increased transfusions, no study has actually shown an increase in mortality.”

Meanwhile, the risk of a fatal myocardial infarction is high when antiplatelet therapy is withdrawn, especially within 6 weeks of stent placement. The risk is especially high in patients with cancer, diabetes, and other hypercoagulable states, and in those with long, multiple, or overlapping stents, Dr. Dardik said.

“Keep the nontherapeutic window short, from about 3 days before the surgery to 1-2 days afterward, [and] reload [patients] at high risk for thrombosis with 300 mg of clopidogrel,” Dr. Dardik said at the meeting.

Since dual-antiplatelet therapy is standard for 6 months following stent placement, patients on clopidogrel (Plavix) will almost certainly also be on aspirin. To offset the temporary loss of clopidogrel, he recommended increasing the aspirin dose, said Dr. Dardik, a vascular surgeon at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The best option for recently stented patients is to postpone surgery for at least 6 months – the point at which dual-antiplatelet therapy can be stopped – or even a year, when aspirin can also cease. When that's not possible, Dr. Dardik recommends performing a less invasive procedure, with easier hemostasis.

He said he has no relevant disclosures.

Freight-Train Suicide Autopsies Spark Rail Industry Prevention Measures

PORTLAND, ORE. – People who kill themselves by freight train are similar to others who commit suicide in other ways, but perhaps suffer more severe mental illness, social isolation, and poverty, according to psychological autopsies conducted on 62 recent freight train suicides.