User login

Is your patient making the ‘wrong’ treatment choice?

Consultation/liaison (C/L) psychiatrists assess capacity in 1 of 6 consults,1 and these evaluations must be quick but systematic. Hospital time is precious, and asking for a psychiatry consult inevitably slows down the medical team’s efforts to care for sick or injured patients.

We suggest an approach our C/L service developed to rapidly weigh capacity’s three dimensions—risks, benefits, and patient decisions—to formulate appropriate opinions for the medical team.

A standard for capacity

In most cases, capacity must be assessed and considered adequate before a patient can provide informed consent for a medical intervention. Because a patient might be capable of making some decisions but not others, the standard for determining capacity is not black and white but a sliding scale that depends on the magnitude of the decision being made.

As physicians, psychiatrists understand doctors’ frustrations when they believe a patient is making the wrong treatment choice. When the primary team turns to us, they want us to help determine the most appropriate course of action.

Capacity is determined by weighing whether the patient is competent to exercise his or her autonomy in making a decision about medical treatment. We do not assess global capacity; the goal is to provide an unbiased opinion about specific capacity for a given situation–“Does Mr. X have the ability to accept/refuse this treatment option presented to him?”

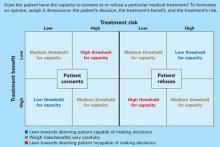

Capacity’s three dimensions. The means to achieve this goal are often complex. Roth et al2 proposed that capacity could be measured on a sliding scale. Wise and Rundell3 agreed and developed a two-dimension table to show that capacity can be evaluated at different thresholds, depending on the patient’s clinical situation. We expanded this model (Figure) to include three dimensions to consider when you evaluate capacity:

- risk of the proposed treatment (high vs. low)

- benefit of the treatment (high vs. low)

- the patient’s decision about the treatment (accept vs. refuse).

If a treatment’s benefits far outweigh the risks and the patient accepts that treatment, he is probably capable of making that decision and a lenient (low) threshold to establish capacity applies. If the same patient refuses the high-benefit, low-risk treatment, then he might be incapable of making that decision and a stringent (high) threshold to establish capacity comes into play. Our C/L service often uses this model when discussing capacity evaluations with the primary team. It explains why some capacity evaluations—when a patient agrees to a low-risk, high-benefit procedure—might take minutes, whereas others—those that fall into the medium threshold for capacity—take hours. Consider the following cases.

Figure 3-dimension model for evaluating capacity

Three cases: Is capacity evaluation needed?

Mr. X, age 25, was in a motor vehicle accident that caused trauma to his esophagus. He requires a feeding tube because he will be unable to eat for several weeks. The risk of the procedure (feeding tube placement) is low, and the benefit (getting possibly life-saving nutrition) is high.

If Mr. X refuses the feeding tube, he may be incapable of making this decision and would require a rigorous capacity evaluation (high-threshold capacity). If he consents, he is making a choice with which most reasonable people would agree, and establishing capacity would be less important (low-threshold capacity).

Mr. J, age 95, has congestive heart failure, diabetes, and liver disease. If he consents to a liver transplant—a treatment likely to be low-benefit and high-risk—he would require a rigorous capacity evaluation. If he refuses this surgical intervention, then more-lenient capacity criteria would apply.

Mrs. F, age 59, has breast cancer with metastases. Her oncologist is recommending bilateral mastectomy, radiation, chemotherapy, and an experimental treatment that has shown favorable results. The risk of treatment is high, and the benefit is unknown but most likely high. Since this is a high-risk, high-benefit intervention, the capacity threshold is medium. Whether she consents to or refuses treatment, you must weigh risks and benefits very carefully with her.

The primary team’s role

A common myth holds that only psychiatrists can determine capacity, but any physician can.4 The primary team may feel comfortable deciding a patient’s capacity without seeking consultation after asking the screening questions in Table 1.5,6 A patient who gives consistent and appropriate answers to these screening questions usually also can answer the more detailed questions psychiatrists would ask and thus has sufficient capacity.

When uncertainties remain after screening, we recommend that the primary team ask psychiatry for an opinion. Knowing what the primary team is thinking about a difficult case often helps the psychiatric consultant. So when consulting with psychiatry, we suggest that the primary team:

- clarify the question (such as, “Does Mrs. Z have the capacity to refuse dialysis?”)

- give an opinion about whether the patient does or does not have capacity and why.

When sharing of opinions was studied at institutions trying this idea, C/L teams agreed with the primary teams’ initial impression of patients’ capacity 80% of the time.4 Most consults occurred because the patient was refusing an intervention the primary team felt was “essential,” or the patient and primary team disagreed on code status. At our institution, anecdotal evidence shows that if the primary team spends a few minutes asking screening questions, the C/L service and primary team agree on the patient’s capacity >90% of the time.

Table 1

Primary team capacity evaluation: 5 W’s

Explain to the patient the treatment you recommend. Review risks and benefits of accepting and of refusing the treatment. Describe alternatives. Then ask these screening questions to assess capacity:

|

| Source: References 5,6 |

Tips for the psychiatrist

C/L psychiatrists are usually asked to evaluate capacity in complicated cases, such as when the:

- family disagrees with the patient’s decision

- patient changes his mind several times

- patient has a formidable psychiatric history.

Determining capacity requires that you assess the patient’s ability to communicate choices, understand and retain information about his condition and proposed treatment, appreciate likely consequences, and rationally manipulate information (Table 2).7

You can often gauge a patient’s attitude the moment you walk into his or her room. Those who feel insulted or defensive about being evaluated by a psychiatrist say things like:

- “I’m not crazy; I don’t need to talk to you.”

- “I think you need to evaluate my doctors, not me.”

- “Why is it so hard to believe that I’m ready to die? You can’t change my mind. Get out!”

To put the patient at ease, consider an inoffensive introduction such as: “My name is Dr. Y and I’m one of the psychiatrists who work here. I’m often called by the primary team to help explain the pros and cons of the various treatments we can provide to you. I’m not here to change your mind; I just want to make sure you are aware of all your options.”

Table 2

Psychiatry C/L service capacity evaluation

Ability to communicate choices

|

Ability to understand information about a treatment

|

Appreciation of likely consequences

|

Rational manipulation of information

|

| Source: References 5,6 |

Is it ever ok not to assess capacity?

In rare situations, informed consent does not need to be pursued and neither does capacity. Informed consent occurs when a capable patient receives adequate information to make a decision and voluntarily consents to the proposed intervention.8 Informed consent is not required in emergency, patient waiver, or therapeutic privilege situations.8,9

Emergency exception is permitted if the patient lacks the capacity to consent and the harm of postponing therapy is imminent and outweighs the proposed intervention’s risks. These cases are usually life-threatening situations in the emergency department, such as when a patient suffers severe physical trauma in a motor vehicle accident and is unable to communicate. Although capacity cannot be established, patients are taken immediately to the operating room.

If a patient with capacity refuses emergent treatment, however, the treating physician cannot override the patient’s wishes simply because it is an emergency. For example:

Mrs. L, age 32, lost several liters of blood during a complicated vaginal delivery. Her obstetrician felt she needed an emergent blood transfusion to avoid further medical complications. Mrs. L—a Jehovah’s Witness—refused the transfusion because of her religious beliefs. She was deemed capable of making this decision, and the transfusion was deferred.8-10

Patient waiver applies when a patient does not want to know all the relevant information about a procedure; he or she may wish for the physician (or another person) to make decisions.

Therapeutic privilege, a controversial idea, allows the physician to make decisions for the patient without informed consent when the physician believes the risk of giving pertinent information poses a serious detriment to the patient. In the rare cases when this is invoked, obtain family input if possible. For example:

Mrs. J, age 70, has severe health anxiety. When the primary care physician she has seen for 30 years tries to discuss treatments with her, Mrs. J fixates on potential harms and refuses treatments with even minimal risk. Her doctor tells her that it may be in her best interest to not hear the risks of treatment. Mrs. J agrees and gives her doctor permission to discusses treatment risks and benefits with her daughter, who is intricately involved in her mother’s health care.

Related resources

- Harvard Medical School department of psychiatry. Web site on forensic psychiatry and medicine. www.forensic-psych.com.

- Stern TA, Fricchione GL, Cassem, NH, et al (eds). Massachusetts General Hospital handbook of general hospital psychiatry (5th ed). Philadelphia: CV Mosby; 2004:355-9.

1. Viswanathan R, Schindler B, Brendel RW, et al. Should APM develop practice guidelines for decisional capacity assessments in the medical setting? Presented at: Annual Meeting of the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine; November 16-20, 2005; Santa Ana Pueblo, NM.

2. Roth LH, Meisel A, Lidz CW. Tests of competency to consent to treatment. Am J Psychiatry 1977;124:279-84.

3. Wise MG, Rundell JR. Medicolegal issues in consultation. In: Clinical manual of psychosomatic medicine: a guide to consultation-liaison psychiatry. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2005:254-67.

4. Muskin PR, Kornfeld DS, Aladjem A, Tahil F. Determining capacity: Is it just capacity? Plenary workshop at: Annual Meeting of the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine; November 16-20, 2005; Santa Ana Pueblo, NM.

5. Malin PJ. Creighton University. Educational handout (adapted with permission).

6. Poole K, Singh M, Murphy J. Law and medicine: the dilemmas of capacity, consultation/liaison psychiatry. Presented at: The Mayo Clinic; February 15, 2001; Rochester, MN.

7. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS. Assessing competence to consent to treatment: A guide for physicians and other health professionals. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998.

8. Nora LM, Benvenuti RJ. Iatrogenic disorders: medicolegal aspects of informed consent. Neurol Clin 1998;16:207-16.

9. Coulson KM, Glasser BL, Liang BA. Informed consent: issues for providers. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2002;16:1365-80.

10. Magid M, Reichenberg JS, Philbrick KL. To cut or not to cut: that was the question. Poster presented at: Meeting of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law; October 2005; Montreal, Canada.

Consultation/liaison (C/L) psychiatrists assess capacity in 1 of 6 consults,1 and these evaluations must be quick but systematic. Hospital time is precious, and asking for a psychiatry consult inevitably slows down the medical team’s efforts to care for sick or injured patients.

We suggest an approach our C/L service developed to rapidly weigh capacity’s three dimensions—risks, benefits, and patient decisions—to formulate appropriate opinions for the medical team.

A standard for capacity

In most cases, capacity must be assessed and considered adequate before a patient can provide informed consent for a medical intervention. Because a patient might be capable of making some decisions but not others, the standard for determining capacity is not black and white but a sliding scale that depends on the magnitude of the decision being made.

As physicians, psychiatrists understand doctors’ frustrations when they believe a patient is making the wrong treatment choice. When the primary team turns to us, they want us to help determine the most appropriate course of action.

Capacity is determined by weighing whether the patient is competent to exercise his or her autonomy in making a decision about medical treatment. We do not assess global capacity; the goal is to provide an unbiased opinion about specific capacity for a given situation–“Does Mr. X have the ability to accept/refuse this treatment option presented to him?”

Capacity’s three dimensions. The means to achieve this goal are often complex. Roth et al2 proposed that capacity could be measured on a sliding scale. Wise and Rundell3 agreed and developed a two-dimension table to show that capacity can be evaluated at different thresholds, depending on the patient’s clinical situation. We expanded this model (Figure) to include three dimensions to consider when you evaluate capacity:

- risk of the proposed treatment (high vs. low)

- benefit of the treatment (high vs. low)

- the patient’s decision about the treatment (accept vs. refuse).

If a treatment’s benefits far outweigh the risks and the patient accepts that treatment, he is probably capable of making that decision and a lenient (low) threshold to establish capacity applies. If the same patient refuses the high-benefit, low-risk treatment, then he might be incapable of making that decision and a stringent (high) threshold to establish capacity comes into play. Our C/L service often uses this model when discussing capacity evaluations with the primary team. It explains why some capacity evaluations—when a patient agrees to a low-risk, high-benefit procedure—might take minutes, whereas others—those that fall into the medium threshold for capacity—take hours. Consider the following cases.

Figure 3-dimension model for evaluating capacity

Three cases: Is capacity evaluation needed?

Mr. X, age 25, was in a motor vehicle accident that caused trauma to his esophagus. He requires a feeding tube because he will be unable to eat for several weeks. The risk of the procedure (feeding tube placement) is low, and the benefit (getting possibly life-saving nutrition) is high.

If Mr. X refuses the feeding tube, he may be incapable of making this decision and would require a rigorous capacity evaluation (high-threshold capacity). If he consents, he is making a choice with which most reasonable people would agree, and establishing capacity would be less important (low-threshold capacity).

Mr. J, age 95, has congestive heart failure, diabetes, and liver disease. If he consents to a liver transplant—a treatment likely to be low-benefit and high-risk—he would require a rigorous capacity evaluation. If he refuses this surgical intervention, then more-lenient capacity criteria would apply.

Mrs. F, age 59, has breast cancer with metastases. Her oncologist is recommending bilateral mastectomy, radiation, chemotherapy, and an experimental treatment that has shown favorable results. The risk of treatment is high, and the benefit is unknown but most likely high. Since this is a high-risk, high-benefit intervention, the capacity threshold is medium. Whether she consents to or refuses treatment, you must weigh risks and benefits very carefully with her.

The primary team’s role

A common myth holds that only psychiatrists can determine capacity, but any physician can.4 The primary team may feel comfortable deciding a patient’s capacity without seeking consultation after asking the screening questions in Table 1.5,6 A patient who gives consistent and appropriate answers to these screening questions usually also can answer the more detailed questions psychiatrists would ask and thus has sufficient capacity.

When uncertainties remain after screening, we recommend that the primary team ask psychiatry for an opinion. Knowing what the primary team is thinking about a difficult case often helps the psychiatric consultant. So when consulting with psychiatry, we suggest that the primary team:

- clarify the question (such as, “Does Mrs. Z have the capacity to refuse dialysis?”)

- give an opinion about whether the patient does or does not have capacity and why.

When sharing of opinions was studied at institutions trying this idea, C/L teams agreed with the primary teams’ initial impression of patients’ capacity 80% of the time.4 Most consults occurred because the patient was refusing an intervention the primary team felt was “essential,” or the patient and primary team disagreed on code status. At our institution, anecdotal evidence shows that if the primary team spends a few minutes asking screening questions, the C/L service and primary team agree on the patient’s capacity >90% of the time.

Table 1

Primary team capacity evaluation: 5 W’s

Explain to the patient the treatment you recommend. Review risks and benefits of accepting and of refusing the treatment. Describe alternatives. Then ask these screening questions to assess capacity:

|

| Source: References 5,6 |

Tips for the psychiatrist

C/L psychiatrists are usually asked to evaluate capacity in complicated cases, such as when the:

- family disagrees with the patient’s decision

- patient changes his mind several times

- patient has a formidable psychiatric history.

Determining capacity requires that you assess the patient’s ability to communicate choices, understand and retain information about his condition and proposed treatment, appreciate likely consequences, and rationally manipulate information (Table 2).7

You can often gauge a patient’s attitude the moment you walk into his or her room. Those who feel insulted or defensive about being evaluated by a psychiatrist say things like:

- “I’m not crazy; I don’t need to talk to you.”

- “I think you need to evaluate my doctors, not me.”

- “Why is it so hard to believe that I’m ready to die? You can’t change my mind. Get out!”

To put the patient at ease, consider an inoffensive introduction such as: “My name is Dr. Y and I’m one of the psychiatrists who work here. I’m often called by the primary team to help explain the pros and cons of the various treatments we can provide to you. I’m not here to change your mind; I just want to make sure you are aware of all your options.”

Table 2

Psychiatry C/L service capacity evaluation

Ability to communicate choices

|

Ability to understand information about a treatment

|

Appreciation of likely consequences

|

Rational manipulation of information

|

| Source: References 5,6 |

Is it ever ok not to assess capacity?

In rare situations, informed consent does not need to be pursued and neither does capacity. Informed consent occurs when a capable patient receives adequate information to make a decision and voluntarily consents to the proposed intervention.8 Informed consent is not required in emergency, patient waiver, or therapeutic privilege situations.8,9

Emergency exception is permitted if the patient lacks the capacity to consent and the harm of postponing therapy is imminent and outweighs the proposed intervention’s risks. These cases are usually life-threatening situations in the emergency department, such as when a patient suffers severe physical trauma in a motor vehicle accident and is unable to communicate. Although capacity cannot be established, patients are taken immediately to the operating room.

If a patient with capacity refuses emergent treatment, however, the treating physician cannot override the patient’s wishes simply because it is an emergency. For example:

Mrs. L, age 32, lost several liters of blood during a complicated vaginal delivery. Her obstetrician felt she needed an emergent blood transfusion to avoid further medical complications. Mrs. L—a Jehovah’s Witness—refused the transfusion because of her religious beliefs. She was deemed capable of making this decision, and the transfusion was deferred.8-10

Patient waiver applies when a patient does not want to know all the relevant information about a procedure; he or she may wish for the physician (or another person) to make decisions.

Therapeutic privilege, a controversial idea, allows the physician to make decisions for the patient without informed consent when the physician believes the risk of giving pertinent information poses a serious detriment to the patient. In the rare cases when this is invoked, obtain family input if possible. For example:

Mrs. J, age 70, has severe health anxiety. When the primary care physician she has seen for 30 years tries to discuss treatments with her, Mrs. J fixates on potential harms and refuses treatments with even minimal risk. Her doctor tells her that it may be in her best interest to not hear the risks of treatment. Mrs. J agrees and gives her doctor permission to discusses treatment risks and benefits with her daughter, who is intricately involved in her mother’s health care.

Related resources

- Harvard Medical School department of psychiatry. Web site on forensic psychiatry and medicine. www.forensic-psych.com.

- Stern TA, Fricchione GL, Cassem, NH, et al (eds). Massachusetts General Hospital handbook of general hospital psychiatry (5th ed). Philadelphia: CV Mosby; 2004:355-9.

Consultation/liaison (C/L) psychiatrists assess capacity in 1 of 6 consults,1 and these evaluations must be quick but systematic. Hospital time is precious, and asking for a psychiatry consult inevitably slows down the medical team’s efforts to care for sick or injured patients.

We suggest an approach our C/L service developed to rapidly weigh capacity’s three dimensions—risks, benefits, and patient decisions—to formulate appropriate opinions for the medical team.

A standard for capacity

In most cases, capacity must be assessed and considered adequate before a patient can provide informed consent for a medical intervention. Because a patient might be capable of making some decisions but not others, the standard for determining capacity is not black and white but a sliding scale that depends on the magnitude of the decision being made.

As physicians, psychiatrists understand doctors’ frustrations when they believe a patient is making the wrong treatment choice. When the primary team turns to us, they want us to help determine the most appropriate course of action.

Capacity is determined by weighing whether the patient is competent to exercise his or her autonomy in making a decision about medical treatment. We do not assess global capacity; the goal is to provide an unbiased opinion about specific capacity for a given situation–“Does Mr. X have the ability to accept/refuse this treatment option presented to him?”

Capacity’s three dimensions. The means to achieve this goal are often complex. Roth et al2 proposed that capacity could be measured on a sliding scale. Wise and Rundell3 agreed and developed a two-dimension table to show that capacity can be evaluated at different thresholds, depending on the patient’s clinical situation. We expanded this model (Figure) to include three dimensions to consider when you evaluate capacity:

- risk of the proposed treatment (high vs. low)

- benefit of the treatment (high vs. low)

- the patient’s decision about the treatment (accept vs. refuse).

If a treatment’s benefits far outweigh the risks and the patient accepts that treatment, he is probably capable of making that decision and a lenient (low) threshold to establish capacity applies. If the same patient refuses the high-benefit, low-risk treatment, then he might be incapable of making that decision and a stringent (high) threshold to establish capacity comes into play. Our C/L service often uses this model when discussing capacity evaluations with the primary team. It explains why some capacity evaluations—when a patient agrees to a low-risk, high-benefit procedure—might take minutes, whereas others—those that fall into the medium threshold for capacity—take hours. Consider the following cases.

Figure 3-dimension model for evaluating capacity

Three cases: Is capacity evaluation needed?

Mr. X, age 25, was in a motor vehicle accident that caused trauma to his esophagus. He requires a feeding tube because he will be unable to eat for several weeks. The risk of the procedure (feeding tube placement) is low, and the benefit (getting possibly life-saving nutrition) is high.

If Mr. X refuses the feeding tube, he may be incapable of making this decision and would require a rigorous capacity evaluation (high-threshold capacity). If he consents, he is making a choice with which most reasonable people would agree, and establishing capacity would be less important (low-threshold capacity).

Mr. J, age 95, has congestive heart failure, diabetes, and liver disease. If he consents to a liver transplant—a treatment likely to be low-benefit and high-risk—he would require a rigorous capacity evaluation. If he refuses this surgical intervention, then more-lenient capacity criteria would apply.

Mrs. F, age 59, has breast cancer with metastases. Her oncologist is recommending bilateral mastectomy, radiation, chemotherapy, and an experimental treatment that has shown favorable results. The risk of treatment is high, and the benefit is unknown but most likely high. Since this is a high-risk, high-benefit intervention, the capacity threshold is medium. Whether she consents to or refuses treatment, you must weigh risks and benefits very carefully with her.

The primary team’s role

A common myth holds that only psychiatrists can determine capacity, but any physician can.4 The primary team may feel comfortable deciding a patient’s capacity without seeking consultation after asking the screening questions in Table 1.5,6 A patient who gives consistent and appropriate answers to these screening questions usually also can answer the more detailed questions psychiatrists would ask and thus has sufficient capacity.

When uncertainties remain after screening, we recommend that the primary team ask psychiatry for an opinion. Knowing what the primary team is thinking about a difficult case often helps the psychiatric consultant. So when consulting with psychiatry, we suggest that the primary team:

- clarify the question (such as, “Does Mrs. Z have the capacity to refuse dialysis?”)

- give an opinion about whether the patient does or does not have capacity and why.

When sharing of opinions was studied at institutions trying this idea, C/L teams agreed with the primary teams’ initial impression of patients’ capacity 80% of the time.4 Most consults occurred because the patient was refusing an intervention the primary team felt was “essential,” or the patient and primary team disagreed on code status. At our institution, anecdotal evidence shows that if the primary team spends a few minutes asking screening questions, the C/L service and primary team agree on the patient’s capacity >90% of the time.

Table 1

Primary team capacity evaluation: 5 W’s

Explain to the patient the treatment you recommend. Review risks and benefits of accepting and of refusing the treatment. Describe alternatives. Then ask these screening questions to assess capacity:

|

| Source: References 5,6 |

Tips for the psychiatrist

C/L psychiatrists are usually asked to evaluate capacity in complicated cases, such as when the:

- family disagrees with the patient’s decision

- patient changes his mind several times

- patient has a formidable psychiatric history.

Determining capacity requires that you assess the patient’s ability to communicate choices, understand and retain information about his condition and proposed treatment, appreciate likely consequences, and rationally manipulate information (Table 2).7

You can often gauge a patient’s attitude the moment you walk into his or her room. Those who feel insulted or defensive about being evaluated by a psychiatrist say things like:

- “I’m not crazy; I don’t need to talk to you.”

- “I think you need to evaluate my doctors, not me.”

- “Why is it so hard to believe that I’m ready to die? You can’t change my mind. Get out!”

To put the patient at ease, consider an inoffensive introduction such as: “My name is Dr. Y and I’m one of the psychiatrists who work here. I’m often called by the primary team to help explain the pros and cons of the various treatments we can provide to you. I’m not here to change your mind; I just want to make sure you are aware of all your options.”

Table 2

Psychiatry C/L service capacity evaluation

Ability to communicate choices

|

Ability to understand information about a treatment

|

Appreciation of likely consequences

|

Rational manipulation of information

|

| Source: References 5,6 |

Is it ever ok not to assess capacity?

In rare situations, informed consent does not need to be pursued and neither does capacity. Informed consent occurs when a capable patient receives adequate information to make a decision and voluntarily consents to the proposed intervention.8 Informed consent is not required in emergency, patient waiver, or therapeutic privilege situations.8,9

Emergency exception is permitted if the patient lacks the capacity to consent and the harm of postponing therapy is imminent and outweighs the proposed intervention’s risks. These cases are usually life-threatening situations in the emergency department, such as when a patient suffers severe physical trauma in a motor vehicle accident and is unable to communicate. Although capacity cannot be established, patients are taken immediately to the operating room.

If a patient with capacity refuses emergent treatment, however, the treating physician cannot override the patient’s wishes simply because it is an emergency. For example:

Mrs. L, age 32, lost several liters of blood during a complicated vaginal delivery. Her obstetrician felt she needed an emergent blood transfusion to avoid further medical complications. Mrs. L—a Jehovah’s Witness—refused the transfusion because of her religious beliefs. She was deemed capable of making this decision, and the transfusion was deferred.8-10

Patient waiver applies when a patient does not want to know all the relevant information about a procedure; he or she may wish for the physician (or another person) to make decisions.

Therapeutic privilege, a controversial idea, allows the physician to make decisions for the patient without informed consent when the physician believes the risk of giving pertinent information poses a serious detriment to the patient. In the rare cases when this is invoked, obtain family input if possible. For example:

Mrs. J, age 70, has severe health anxiety. When the primary care physician she has seen for 30 years tries to discuss treatments with her, Mrs. J fixates on potential harms and refuses treatments with even minimal risk. Her doctor tells her that it may be in her best interest to not hear the risks of treatment. Mrs. J agrees and gives her doctor permission to discusses treatment risks and benefits with her daughter, who is intricately involved in her mother’s health care.

Related resources

- Harvard Medical School department of psychiatry. Web site on forensic psychiatry and medicine. www.forensic-psych.com.

- Stern TA, Fricchione GL, Cassem, NH, et al (eds). Massachusetts General Hospital handbook of general hospital psychiatry (5th ed). Philadelphia: CV Mosby; 2004:355-9.

1. Viswanathan R, Schindler B, Brendel RW, et al. Should APM develop practice guidelines for decisional capacity assessments in the medical setting? Presented at: Annual Meeting of the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine; November 16-20, 2005; Santa Ana Pueblo, NM.

2. Roth LH, Meisel A, Lidz CW. Tests of competency to consent to treatment. Am J Psychiatry 1977;124:279-84.

3. Wise MG, Rundell JR. Medicolegal issues in consultation. In: Clinical manual of psychosomatic medicine: a guide to consultation-liaison psychiatry. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2005:254-67.

4. Muskin PR, Kornfeld DS, Aladjem A, Tahil F. Determining capacity: Is it just capacity? Plenary workshop at: Annual Meeting of the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine; November 16-20, 2005; Santa Ana Pueblo, NM.

5. Malin PJ. Creighton University. Educational handout (adapted with permission).

6. Poole K, Singh M, Murphy J. Law and medicine: the dilemmas of capacity, consultation/liaison psychiatry. Presented at: The Mayo Clinic; February 15, 2001; Rochester, MN.

7. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS. Assessing competence to consent to treatment: A guide for physicians and other health professionals. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998.

8. Nora LM, Benvenuti RJ. Iatrogenic disorders: medicolegal aspects of informed consent. Neurol Clin 1998;16:207-16.

9. Coulson KM, Glasser BL, Liang BA. Informed consent: issues for providers. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2002;16:1365-80.

10. Magid M, Reichenberg JS, Philbrick KL. To cut or not to cut: that was the question. Poster presented at: Meeting of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law; October 2005; Montreal, Canada.

1. Viswanathan R, Schindler B, Brendel RW, et al. Should APM develop practice guidelines for decisional capacity assessments in the medical setting? Presented at: Annual Meeting of the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine; November 16-20, 2005; Santa Ana Pueblo, NM.

2. Roth LH, Meisel A, Lidz CW. Tests of competency to consent to treatment. Am J Psychiatry 1977;124:279-84.

3. Wise MG, Rundell JR. Medicolegal issues in consultation. In: Clinical manual of psychosomatic medicine: a guide to consultation-liaison psychiatry. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2005:254-67.

4. Muskin PR, Kornfeld DS, Aladjem A, Tahil F. Determining capacity: Is it just capacity? Plenary workshop at: Annual Meeting of the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine; November 16-20, 2005; Santa Ana Pueblo, NM.

5. Malin PJ. Creighton University. Educational handout (adapted with permission).

6. Poole K, Singh M, Murphy J. Law and medicine: the dilemmas of capacity, consultation/liaison psychiatry. Presented at: The Mayo Clinic; February 15, 2001; Rochester, MN.

7. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS. Assessing competence to consent to treatment: A guide for physicians and other health professionals. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998.

8. Nora LM, Benvenuti RJ. Iatrogenic disorders: medicolegal aspects of informed consent. Neurol Clin 1998;16:207-16.

9. Coulson KM, Glasser BL, Liang BA. Informed consent: issues for providers. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2002;16:1365-80.

10. Magid M, Reichenberg JS, Philbrick KL. To cut or not to cut: that was the question. Poster presented at: Meeting of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law; October 2005; Montreal, Canada.