User login

Botulinum toxin for depression

Botulinum toxin for depression? An idea that’s raising some eyebrows

Psychiatry is experiencing a major paradigm shift.1 No longer is depression a disease of norepinephrine and serotonin deficiency. Today, we are exploring inflammation, methylation, epigenetics, and neuroplasticity as major players; we are using innovative treatment interventions such as ketamine, magnets, psilocin, anti-inflammatories, and even botulinum toxin.

In 2006, dermatologist Eric Finzi, MD, PhD, reported a case series of 10 depressed patients who were given a single course of botulinum toxin A (BTA, onabotulinum-toxinA) injections in the forehead.2 After 2 months, 9 out of the 10 patients were no longer depressed. The 10th patient, who reported improvement in symptoms but not remission, was the only patient with bipolar depression.

As a psychiatrist (M.M.) and a dermatologist (J.R.), we conducted a randomized controlled trial3 to challenge the difficult-to-swallow notion that a cosmetic intervention could help severely depressed patients. After reporting our positive findings and hearing numerous encouraging patient testimonials, we present a favorable review on the treatment of depression using BTA. We also present the top 10 questions we are asked at lectures about this novel treatment.

A deadly toxin used to treat medical conditions

Botulinum toxin is one of the deadliest substance known to man.4 It was named after the gram-positive bacterium Clostridium botulinum, which causes so-called floppy baby syndrome in infants who eat contaminated honey. Botulinum toxin prevents nerves from releasing acetylcholine, which causes muscle paralysis.

In the wrong hands, botulinum toxin can be exploited for chemical warfare.4 However, doctors are using it to treat >50 medical conditions, including migraine, cervical dystonia, strabismus, overactive bladder, urinary incontinence, excessive sweating, muscle spasm, and now depression.5,6 In 2014, BTA was the top cosmetic treatment in the United States, with >3 million procedures performed, generating more than 1 billion dollars in revenue.7

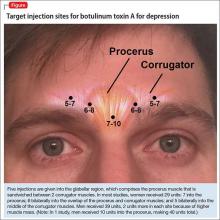

The most common site injected with BTA for cosmetic treatments is the glabellar region, which is the area directly above and in between the eyebrows (ie, the lower forehead). The glabella comprises 2 main muscles: the central procerus flanked by a pair of corrugators (Figure). When expressing fear, anger, sadness, or anguish, these muscles contract, causing the appearance of 2 vertical wrinkles, referred to as the “11s.” The wrinkles also can form the shape of an upside-down “U,” known as the omega sign.8 BTA prevents contraction of these muscles and therefore prevents the appearance of a furrowed brow. During cosmetic procedures, approximately 20 to 50 units of BTA are spread out over 5 glabellar injection sites.9 A similar technique is being used in studies of BTA for depression2,3,10,11 (Figure).

BTA for depression is new to the mental health world but, before psychiatrists caught on, dermatologists were aware that BTA could improve quality of life,12 reduce negative emotions,13 and increase feelings of well-being.14

The evidence

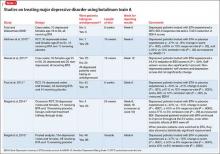

To date, there have been 2 case series,2,15 3 randomized control trials (RCTs),3,10,11 1 pooled analysis,16,17 and 1 meta-analysis18 looking at botulinum for depression (Table 1).2,10,11,15-17 In each trial, a single treatment of BTA (ie, 1 doctor’s visit; 29 to 40 units of BTA distributed into 5 glabellar injections sites), was the intervention studied.2

The first case series, by Finzi and Wasserman2 is described above. A second case series, published in 2013, describes 50 female patients, one-half depressed and one-half non-depressed, all of whom received 20 units of BTA into the glabella.15 At 12 weeks, depression scores in the depressed group had decreased by 54% (14.9 point drop on Beck Depression Inventory [BDI], P < .001) and self-esteem scores had increased significantly. In non-depressed participants, depression scores and self-esteem scores remained constant throughout the 12 weeks.

A pooled analysis reported results of 3 RCTs16,17 consisting of a total of 134 depressed patients, males and females age 18 to 65 who received BTA (n = 59) or placebo (n = 74) into the glabellar region. At the end of 6 weeks, BDI scores in the depressed group had decreased by 47.4% (14.3 points) compared with a 16.2% decrease (5.1 points) in the placebo group. This corresponds to a 52.5% vs 8.0% response rate and a 42.4% vs 8.0% remission rate, respectively (Table 1,1,2,10,11,15-17). There was no difference between the 2 groups in sex, age, depression severity, and number of antidepressants being taken. Females received 29 units and males received 10 to 11 units more to account for higher muscle mass (Figure).

Depression as measured by the physician-administered Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) and the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale showed similar reduction in overall scores (−45.7% vs −14.6%), response rates (54.2% vs 10.7%) and remission rates (30.5% vs 6.7%) with BTA.

Although these improvements in depression scores do not reach those seen with electroconvulsive therapy,19,20 they are comparable to placebo-controlled studies of antidepressants.21,22

Doesn’t this technique work because people who look better, feel better?

Aesthetic improvement alone is unlikely to explain the entire story. A recent study showed that improvement in wrinkle score did not correlate with improvement in mood.23 Furthermore, some patients in RCTs did not like the cosmetic effects of BTA but still reported feeling less depressed after treatment.10

How might it work?

Several theories about the mechanism of action have been proposed:

• The facial feedback hypothesis dates to Charles Darwin in 1872: Facial movements influence emotional states. Numerous studies have confirmed this. Strack et al24 found that patients asked to smile while reading comics found them to be funnier. Ekman et al25 found that imitating angry facial expressions made body temperature and heart rate rise. Dialectical behavioral therapy expert Marsha Linehan recognized the importance of modifying facial expressions (from grimacing to smiling) and posture (from clenched fists to open hands) when feeling distressed, because it is hard to feel “willful” when your “mind is going one way and your body is going another.”26 Accordingly, for a person who continuously “looks” depressed or distressed, reducing the anguished facial expression using botulinum toxin might diminish the entwined negative emotions.

• A more pleasant facial expression improves social interactions, which leads to improvement in self-esteem and mood. Social biologists argue that (1) we are attracted to those who have more pleasant facial expressions and (2) we steer clear of those who appear angry or depressed (a negative facial expression, such as a growling dog, is perceived as a threat). Therefore, anyone who looks depressed might have less rewarding interpersonal interactions, which can contribute to a poor mood.

On a similar note, mirror neurons are regions in the brain that are activated by witnessing another person’s emotional cues. When our mirror neurons light up, we can feel an observed experience, which is why we often feel nervous around anxious people, or cringe when we see others get hurt, or why we might prefer engaging with people who appear happier. It is possible that, after BTA injection, a person’s social connectivity is improved because of a more positive reciprocal firing of mirror neurons.

• BTA leads to direct and indirect neurochemical changes in the brain that can reduce depression. Functional MRI studies have shown that after glabellar BTA injections, the amygdala was less responsive to negative stimuli.27,28 For example, patients who were treated with BTA and then shown pictures of angry people had an attenuated amygdala response to the photos.

This is an important finding, especially for patients who have been traumatized. After a traumatic event, the amygdala “remembers” what happened, which is good, in some ways (it prevents us from getting into a similar dangerous situation), but bad in others (the traumatized amygdala may falsely perceive a non-threatening stimuli as threatening). A hypervigilant amygdala can lead to an out-of-proportion fear response, depression, and anxiety. Therefore, quelling an overactive amygdala with BTA could improve emotional dysregulation and posttraumatic disorders.

Many of our patients reported that, after BTA injection, “traumatic events didn’t feel as traumatizing,” as one said. The emotional pain and rumination that often follow a life stressor “does not overstay its welcome” and patients are able to “move on” more quickly.

It is unknown why the amygdala is quieted after BTA; researchers hypothesize that BTA suppresses facial feedback signals from the forehead branch of the trigeminal nerve to the brain. Another hypothesis is that BTA is directly transported by the trigeminal nerve into the brain and exerts central pharmacological effects on the amygdala.29 This theory has only been studied in rat models.30

When does it start working? How long does it last?

From what we know, BTA for depression could start working as early as 2 weeks and could last as long as 6 months. In one RCT, the earliest follow-up was 2 weeks,10 at which time the depressed patients had responded to botulinum toxin (P ≤ .05). In the other 2 controlled trials, the earliest follow-up was 3 weeks, at which time a more robust response was seen (P < .001). Aesthetically, BTA usually lasts 3 months. It is unclear how long the antidepressant effects last but, in the longest trial,3 depression symptoms continued to improve at 6 months, after cosmetic effects had worn off.

These findings raise a series of questions:

• Do mood effects outlast cosmetic effects? If so, why?

• Does botulinum toxin start to work sooner than 2 weeks?

• Will adherence improve if a patient has to be treated only every 6 months?

In our clinical experience, depressed patients who responded to BTA injection report a slow resurfacing of depressive symptoms 4 to 6 months after treatment, at which point they usually return for “maintenance treatment” (same dosing, same injection configuration).

Will psychiatrists administer the treatment?

Any physician or physician extender can, when properly trained, inject BTA. The question is: Do psychiatrists want to? Administrating botulinum toxin requires more labor and preparation than prescribing a drug (Table 2,31) and requires placing hands on patients. Depending on the type of psychiatric practice, this may be a “deal-breaker” for some providers, such as those in a psychoanalytic practice who might worry about boundaries.

As a basis for comparison, despite several indications for BTA for headache and neurologic conditions, few neurologists have added botulinum toxin to their practice. Dermatologists who are comfortable seeing psychiatric patients or family practitioners, who are already set up for injection procedures, could become custodians of this intervention.

Which patients are candidates for the treatment?

Patients with anxious or agitated depression might be ideal candidates for BTA injection. A recent study looked at predictors of response: Patients with a high agitation score (as measured on item 9 of the HAM-D) were more likely to respond, with a sensitivity of 100%, a specificity of 56%, and an overall precision of 78%.32 So far, no other predictors of response have been clearly identified. Higher baseline wrinkle scores do not predict better response.23 Sex and age do not have any predictive value. The treatment appears to be equally effective in males and females; because only a handful of males have been treated (n = 14), however, these patients need to be studied further.

Is botulinum toxin better as monotherapy or augmentation strategy?

So far, it appears to be equally effective as monotherapy or augmentation strategy,16 but more studies are needed.

How expensive is it?

Estimates of patient cost include the cost of the product and the professional fee for injection. As a point of reference, for cosmetic purposes, depending on practice location, dermatologists charge $11 to $20 per unit of BTA. Therefore, 1 treatment of BTA for depression (29 to 40 units) can cost a patient $319 to $800.

When treating a patient with BTA for medical indications, such as tension headache, insurance often reimburses the physician for the BTA at cost (paid with a J code: J0585) and pay an injection fee (a procedure code) of $150 to $200. A recent analysis of cost-effectiveness estimated that BTA for depression would cost a patient $1,200 to $1,600 annually.33 Compared with the price of branded medications (eg, $500 to $2,000 annually)33 plus weekly psychotherapy (eg, $2,000 to $5,000 annually), BTA may be a cost-effective option for patients who do not respond to conventional treatments. Of course, for patients who tolerate and respond to generic medications or have a therapist who charges on a sliding scale, BTA is not the most cost-effective option.

What about injecting other areas of the face?

We’ve thought about it but haven’t tried it. There are several muscles around the mouth that allow us to smile and frown. BTA injections in the depressor anguli oris, a muscle around the mouth that is largely responsible for frowning, could treat depression. However, if the mechanism of action is via amygdala desensitization through the trigeminal nerve, treating mouth frown muscles might not work.

Is it safe?

BTA in the glabella has an exceptionally good safety profile.9,31,34 Adverse reactions, which include eyelid droop, pain, bruising, and redness at the injection site, are minor and temporary.9 In addition, BTA has few drug–drug interactions. The biggest complaint for most patients is discomfort upon injection, which often is described as feeling like “an ant bite.”

In the pooled analysis of RCTs, apart from local irritation immediately after injection, temporary headache was the only relevant, and possibly treatment-related, adverse event. Headache occurred in 13.6% (n = 8) of the BTA group and 9.3% (n = 7) of the placebo group (P = .44). Compared with antidepressants such as citalopram, where approximately 38.6% of patients report a moderate or severe side-effect burden,21 BTA is well tolerated.

Are other studies underway?

Larger studies are being conducted,35 mainly to confirm what pilot studies have shown. It would be interesting to discover other predictors of response and if different dosing and injection configurations could strengthen the response rate and extend the duration of effect.

Because of the cosmetic effects of BTA, further studies are needed to address the problem of blinding. In earlier studies, raters were blinded during appointments because patients wore surgical caps that covered their glabellar region.3,10 Patients did not know their treatment intervention, but 52% to 90% of patients guessed correctly.3,10,11 Although unblinding is a common problem in “blinded” trials in which some researchers have reported >75% of participants and raters guessed the intervention correctly,36 it is a particularly sensitive area in studies that involve a change in appearance because it is almost impossible to prevent someone from looking in a mirror.

Summing up

Botulinum toxin for depression is not ready for prime time. The FDA has not approved its use for psychiatric indications, and Medicare and commercial insurance do not reimburse for this procedure as a treatment for depression. Patients who request BTA for depression must be informed that this use is off-label.

For now, we recommend psychotherapy or medication management, or both, for most patients with major depression. In addition, until larger studies are done, we recommend that patients who are interested in BTA for depression use it as an add-on to conventional treatment. However, if larger studies replicate the findings of the smaller studies we have described, botulinum toxin could become a novel therapeutic agent in the fight against depression.

Bottom Line

In pilot studies, botulinum toxin A (BTA) has shown efficacy in improving symptoms of depression. Although considered safe, BTA is not FDA-approved for psychiatric indications, and Medicare and commercial insurance do not reimburse for this procedure for depression. Larger studies are underway to determine if this novel treatment can be introduced into practice.

Related Resources

• Wollmer MA, Magid M, Kruger THC. Botulinum toxin treatment in depression. In: Bewley A, Taylor RE, Reichenberg JS, et al, eds. Practical psychodermatology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2014:216-219.

• Botox for depression. www.botoxfordepression.com.

• Botox and depression. www.botoxanddepression.com.

Drug Brand Names

Botulinum toxin A • Botox

Citalopram • Celexa

Acknowledgments

We thank the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation for granting Dr. Magid a young investigator award and for continuing to invest in innovative research ideas. We thank Dr. Eric Finzi, MD, PhD, Axel Wollmer, MD, and Tillmann Krüger, MD, for their continued collaboration in this area of research.

Disclosures

In July 2011, Dr. Magid received a young investigator award from the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation for her study on treating depression using botulinum toxin (Grant number 17648). In November 2012, after completion and as a result of the study on treating depression using botulinum toxin, Dr. Magid became a consultant with Allergan to discuss study findings. In September 2015, Dr. Magid became a speaker for IPSEN Innovation. Dr. Reichenberg is married to Dr. Magid. Dr. Reichenberg has no other conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Nasrallah HA. 10 Recent paradigm shifts in the neurobiology and treatment of depression. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(2):10-13.

2. Finzi E, Wasserman E. Treatment of depression with botulinum toxin A: a case series. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32(5):645-649; discussion 649-650.

3. Magid M, Reichenberg JS, Poth PE, et al. Treatment of major depressive disorder using botulinum toxin A: a 24-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(8):837-844.

4. Koussoulakos S. Botulinum neurotoxin: the ugly duckling. Eur Neurol. 2008;61(6):331-342.

5. Chen S. Clinical uses of botulinum neurotoxins: current indications, limitations and future developments. Toxins (Basel). 2012;4(10):913-939.

6. Bhidayasiri R, Truong DD. Expanding use of botulinum toxin. J Neurol Sci. 2005;235(1-1):1-9.

7. Cosmetic surgery national data bank statistics. American Society for Asethetic Plastic Surgery. http://www.surgery. org/sites/default/files/2014-Stats.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed May 30, 2015.

8. Shorter E. Darwin’s contribution to psychiatry. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195(6):473-474.

9. Winter L, Spiegel J. Botulinum toxin type-A in the treatment of glabellar lines. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2009;3:1-4.

10. Wollmer MA, de Boer C, Kalak N, et al. Facing depression with botulinum toxin: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46(5):574-581.

11. Finzi E, Rosenthal NE. Treatment of depression with onabotulinumtoxinA: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;52:1-6.

12. Hexsel D, Brum C, Porto MD, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction of patients after full-face injections of abobotulinum toxin type A: a randomized, phase IV clinical trial. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12(12):1363-1367.

13. Lewis MB, Bowler PJ. Botulinum toxin cosmetic therapy correlates with a more positive mood. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2009;8(1):24-26.

14. Sommer B, Zschocke I, Bergfeld D, et al. Satisfaction of patients after treatment with botulinum toxin for dynamic facial lines. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29(5):456-460.

15. Hexsel D, Brum C, Siega C, et al. Evaluation of self‐esteem and depression symptoms in depressed and nondepressed subjects treated with onabotulinumtoxina for glabellar lines. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39(7):1088-1096.

16. Magid M, Reichenberg JS, Finzi E, et al. Treating depression with botulinum toxin: update and meta-analysis from clinic trials. Paper presented at: XVI World Congress of Psychiatry; September 14-18, 2014; Madrid, Spain.

17. Magid M, Finzi E, Kruger TH, et al. Treating depression with botulinum toxin: a pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2015;48(6):205-210.

18. Parsaik A, Mascarenhas S, Hashmi A, et al. Role of botulinum toxin in depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Pract. In press.

19. Scott AI, ed. The ECT handbook, 2nd ed. The third report of the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Special Committee of ECT. London, United Kingdom: The Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2005.

20. Ren J, Li H, Palaniyappan L, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation versus electroconvulsive therapy for major depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2014;51:181-189.

21. Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al; STAR*D Study Team. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR* D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):28-40.

22. Gibbons RD, Hur K, Brown CH, et al. Benefits from antidepressants: synthesis of 6-week patient-level outcomes from double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trials of fluoxetine and venlafaxine. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(6):572-579.

23. Reichenberg JS, Magid M, Keeling B. Botulinum toxin for depression: does the presence of rhytids predict response? Presented at: Texas Dermatology Society; May 2015; Bastrop, Texas.

24. Strack F, Martin LL, Stepper S. Inhibiting and facilitating conditions of the human smile: a nonobtrusive test of the facial feedback hypothesis. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(5):768-777.

25. Ekman P, Levenson RW, Friesen WV. Autonomic nervous system activity distinguishes among emotions. Science. 1983;221(4616):1208-1210.

26. Linehan MM. DBT skills training manual, 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Publications; 2014.

27. Hennenlotter A, Dresel C, Castrop F, et al. The link between facial feedback and neural activity within central circuitries of emotion—new insights from botulinum toxin-induced denervation of frown muscles. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19(3):537-542.

28. Kim MJ, Neta M, Davis FC, et al. Botulinum toxin-induced facial muscle paralysis affects amygdala responses to the perception of emotional expressions: preliminary findings from an A-B-A design. Biol Mood Anxiety Disord. 2014;4:11.

29. Mazzocchio R, Caleo M. More than at the neuromuscular synapse: actions of botulinum neurotoxin A in the central nervous system. Neuroscientist. 2015;21(1):44-61.

30. Antonucci F, Rossi C, Gianfranceschi L, et al. Long-distance retrograde effects of botulinum neurotoxin A. J Neurosci. 2008;28(14):3689-3696.

31. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Medication guide: botox. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/drugsafety/ucm176360.pdf. Updated September 2013. Accessed June 7, 2015.

32. Wollmer MA, Kalak N, Jung S, et al. Agitation predicts response of depression to botulinum toxin treatment in a randomized controlled trial. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:36.

33. Beer K. Cost effectiveness of botulinum toxins for the treatment of depression: preliminary observations. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9(1):27-30.

34. Brin MF, Boodhoo TI, Pogoda JM, et al. Safety and tolerability of onabotulinumtoxinA in the treatment of facial lines: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from global clinical registration studies in 1678 participants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61(6):961-970.e1-11.

35. Botulinum toxin and depression. ClinicalTrials.gov. https:// clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=botulinum+toxin+and+ depression&Search=Search. Accessed June 1, 2015.

36. Rabkin JG, Markowitz JS, Stewart J, et al. How blind is blind? Assessment of patient and doctor medication guesses in a placebo-controlled trial of imipramine and phenelzine. Psychiatry Res. 1986;19(1):75-86.

Psychiatry is experiencing a major paradigm shift.1 No longer is depression a disease of norepinephrine and serotonin deficiency. Today, we are exploring inflammation, methylation, epigenetics, and neuroplasticity as major players; we are using innovative treatment interventions such as ketamine, magnets, psilocin, anti-inflammatories, and even botulinum toxin.

In 2006, dermatologist Eric Finzi, MD, PhD, reported a case series of 10 depressed patients who were given a single course of botulinum toxin A (BTA, onabotulinum-toxinA) injections in the forehead.2 After 2 months, 9 out of the 10 patients were no longer depressed. The 10th patient, who reported improvement in symptoms but not remission, was the only patient with bipolar depression.

As a psychiatrist (M.M.) and a dermatologist (J.R.), we conducted a randomized controlled trial3 to challenge the difficult-to-swallow notion that a cosmetic intervention could help severely depressed patients. After reporting our positive findings and hearing numerous encouraging patient testimonials, we present a favorable review on the treatment of depression using BTA. We also present the top 10 questions we are asked at lectures about this novel treatment.

A deadly toxin used to treat medical conditions

Botulinum toxin is one of the deadliest substance known to man.4 It was named after the gram-positive bacterium Clostridium botulinum, which causes so-called floppy baby syndrome in infants who eat contaminated honey. Botulinum toxin prevents nerves from releasing acetylcholine, which causes muscle paralysis.

In the wrong hands, botulinum toxin can be exploited for chemical warfare.4 However, doctors are using it to treat >50 medical conditions, including migraine, cervical dystonia, strabismus, overactive bladder, urinary incontinence, excessive sweating, muscle spasm, and now depression.5,6 In 2014, BTA was the top cosmetic treatment in the United States, with >3 million procedures performed, generating more than 1 billion dollars in revenue.7

The most common site injected with BTA for cosmetic treatments is the glabellar region, which is the area directly above and in between the eyebrows (ie, the lower forehead). The glabella comprises 2 main muscles: the central procerus flanked by a pair of corrugators (Figure). When expressing fear, anger, sadness, or anguish, these muscles contract, causing the appearance of 2 vertical wrinkles, referred to as the “11s.” The wrinkles also can form the shape of an upside-down “U,” known as the omega sign.8 BTA prevents contraction of these muscles and therefore prevents the appearance of a furrowed brow. During cosmetic procedures, approximately 20 to 50 units of BTA are spread out over 5 glabellar injection sites.9 A similar technique is being used in studies of BTA for depression2,3,10,11 (Figure).

BTA for depression is new to the mental health world but, before psychiatrists caught on, dermatologists were aware that BTA could improve quality of life,12 reduce negative emotions,13 and increase feelings of well-being.14

The evidence

To date, there have been 2 case series,2,15 3 randomized control trials (RCTs),3,10,11 1 pooled analysis,16,17 and 1 meta-analysis18 looking at botulinum for depression (Table 1).2,10,11,15-17 In each trial, a single treatment of BTA (ie, 1 doctor’s visit; 29 to 40 units of BTA distributed into 5 glabellar injections sites), was the intervention studied.2

The first case series, by Finzi and Wasserman2 is described above. A second case series, published in 2013, describes 50 female patients, one-half depressed and one-half non-depressed, all of whom received 20 units of BTA into the glabella.15 At 12 weeks, depression scores in the depressed group had decreased by 54% (14.9 point drop on Beck Depression Inventory [BDI], P < .001) and self-esteem scores had increased significantly. In non-depressed participants, depression scores and self-esteem scores remained constant throughout the 12 weeks.

A pooled analysis reported results of 3 RCTs16,17 consisting of a total of 134 depressed patients, males and females age 18 to 65 who received BTA (n = 59) or placebo (n = 74) into the glabellar region. At the end of 6 weeks, BDI scores in the depressed group had decreased by 47.4% (14.3 points) compared with a 16.2% decrease (5.1 points) in the placebo group. This corresponds to a 52.5% vs 8.0% response rate and a 42.4% vs 8.0% remission rate, respectively (Table 1,1,2,10,11,15-17). There was no difference between the 2 groups in sex, age, depression severity, and number of antidepressants being taken. Females received 29 units and males received 10 to 11 units more to account for higher muscle mass (Figure).

Depression as measured by the physician-administered Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) and the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale showed similar reduction in overall scores (−45.7% vs −14.6%), response rates (54.2% vs 10.7%) and remission rates (30.5% vs 6.7%) with BTA.

Although these improvements in depression scores do not reach those seen with electroconvulsive therapy,19,20 they are comparable to placebo-controlled studies of antidepressants.21,22

Doesn’t this technique work because people who look better, feel better?

Aesthetic improvement alone is unlikely to explain the entire story. A recent study showed that improvement in wrinkle score did not correlate with improvement in mood.23 Furthermore, some patients in RCTs did not like the cosmetic effects of BTA but still reported feeling less depressed after treatment.10

How might it work?

Several theories about the mechanism of action have been proposed:

• The facial feedback hypothesis dates to Charles Darwin in 1872: Facial movements influence emotional states. Numerous studies have confirmed this. Strack et al24 found that patients asked to smile while reading comics found them to be funnier. Ekman et al25 found that imitating angry facial expressions made body temperature and heart rate rise. Dialectical behavioral therapy expert Marsha Linehan recognized the importance of modifying facial expressions (from grimacing to smiling) and posture (from clenched fists to open hands) when feeling distressed, because it is hard to feel “willful” when your “mind is going one way and your body is going another.”26 Accordingly, for a person who continuously “looks” depressed or distressed, reducing the anguished facial expression using botulinum toxin might diminish the entwined negative emotions.

• A more pleasant facial expression improves social interactions, which leads to improvement in self-esteem and mood. Social biologists argue that (1) we are attracted to those who have more pleasant facial expressions and (2) we steer clear of those who appear angry or depressed (a negative facial expression, such as a growling dog, is perceived as a threat). Therefore, anyone who looks depressed might have less rewarding interpersonal interactions, which can contribute to a poor mood.

On a similar note, mirror neurons are regions in the brain that are activated by witnessing another person’s emotional cues. When our mirror neurons light up, we can feel an observed experience, which is why we often feel nervous around anxious people, or cringe when we see others get hurt, or why we might prefer engaging with people who appear happier. It is possible that, after BTA injection, a person’s social connectivity is improved because of a more positive reciprocal firing of mirror neurons.

• BTA leads to direct and indirect neurochemical changes in the brain that can reduce depression. Functional MRI studies have shown that after glabellar BTA injections, the amygdala was less responsive to negative stimuli.27,28 For example, patients who were treated with BTA and then shown pictures of angry people had an attenuated amygdala response to the photos.

This is an important finding, especially for patients who have been traumatized. After a traumatic event, the amygdala “remembers” what happened, which is good, in some ways (it prevents us from getting into a similar dangerous situation), but bad in others (the traumatized amygdala may falsely perceive a non-threatening stimuli as threatening). A hypervigilant amygdala can lead to an out-of-proportion fear response, depression, and anxiety. Therefore, quelling an overactive amygdala with BTA could improve emotional dysregulation and posttraumatic disorders.

Many of our patients reported that, after BTA injection, “traumatic events didn’t feel as traumatizing,” as one said. The emotional pain and rumination that often follow a life stressor “does not overstay its welcome” and patients are able to “move on” more quickly.

It is unknown why the amygdala is quieted after BTA; researchers hypothesize that BTA suppresses facial feedback signals from the forehead branch of the trigeminal nerve to the brain. Another hypothesis is that BTA is directly transported by the trigeminal nerve into the brain and exerts central pharmacological effects on the amygdala.29 This theory has only been studied in rat models.30

When does it start working? How long does it last?

From what we know, BTA for depression could start working as early as 2 weeks and could last as long as 6 months. In one RCT, the earliest follow-up was 2 weeks,10 at which time the depressed patients had responded to botulinum toxin (P ≤ .05). In the other 2 controlled trials, the earliest follow-up was 3 weeks, at which time a more robust response was seen (P < .001). Aesthetically, BTA usually lasts 3 months. It is unclear how long the antidepressant effects last but, in the longest trial,3 depression symptoms continued to improve at 6 months, after cosmetic effects had worn off.

These findings raise a series of questions:

• Do mood effects outlast cosmetic effects? If so, why?

• Does botulinum toxin start to work sooner than 2 weeks?

• Will adherence improve if a patient has to be treated only every 6 months?

In our clinical experience, depressed patients who responded to BTA injection report a slow resurfacing of depressive symptoms 4 to 6 months after treatment, at which point they usually return for “maintenance treatment” (same dosing, same injection configuration).

Will psychiatrists administer the treatment?

Any physician or physician extender can, when properly trained, inject BTA. The question is: Do psychiatrists want to? Administrating botulinum toxin requires more labor and preparation than prescribing a drug (Table 2,31) and requires placing hands on patients. Depending on the type of psychiatric practice, this may be a “deal-breaker” for some providers, such as those in a psychoanalytic practice who might worry about boundaries.

As a basis for comparison, despite several indications for BTA for headache and neurologic conditions, few neurologists have added botulinum toxin to their practice. Dermatologists who are comfortable seeing psychiatric patients or family practitioners, who are already set up for injection procedures, could become custodians of this intervention.

Which patients are candidates for the treatment?

Patients with anxious or agitated depression might be ideal candidates for BTA injection. A recent study looked at predictors of response: Patients with a high agitation score (as measured on item 9 of the HAM-D) were more likely to respond, with a sensitivity of 100%, a specificity of 56%, and an overall precision of 78%.32 So far, no other predictors of response have been clearly identified. Higher baseline wrinkle scores do not predict better response.23 Sex and age do not have any predictive value. The treatment appears to be equally effective in males and females; because only a handful of males have been treated (n = 14), however, these patients need to be studied further.

Is botulinum toxin better as monotherapy or augmentation strategy?

So far, it appears to be equally effective as monotherapy or augmentation strategy,16 but more studies are needed.

How expensive is it?

Estimates of patient cost include the cost of the product and the professional fee for injection. As a point of reference, for cosmetic purposes, depending on practice location, dermatologists charge $11 to $20 per unit of BTA. Therefore, 1 treatment of BTA for depression (29 to 40 units) can cost a patient $319 to $800.

When treating a patient with BTA for medical indications, such as tension headache, insurance often reimburses the physician for the BTA at cost (paid with a J code: J0585) and pay an injection fee (a procedure code) of $150 to $200. A recent analysis of cost-effectiveness estimated that BTA for depression would cost a patient $1,200 to $1,600 annually.33 Compared with the price of branded medications (eg, $500 to $2,000 annually)33 plus weekly psychotherapy (eg, $2,000 to $5,000 annually), BTA may be a cost-effective option for patients who do not respond to conventional treatments. Of course, for patients who tolerate and respond to generic medications or have a therapist who charges on a sliding scale, BTA is not the most cost-effective option.

What about injecting other areas of the face?

We’ve thought about it but haven’t tried it. There are several muscles around the mouth that allow us to smile and frown. BTA injections in the depressor anguli oris, a muscle around the mouth that is largely responsible for frowning, could treat depression. However, if the mechanism of action is via amygdala desensitization through the trigeminal nerve, treating mouth frown muscles might not work.

Is it safe?

BTA in the glabella has an exceptionally good safety profile.9,31,34 Adverse reactions, which include eyelid droop, pain, bruising, and redness at the injection site, are minor and temporary.9 In addition, BTA has few drug–drug interactions. The biggest complaint for most patients is discomfort upon injection, which often is described as feeling like “an ant bite.”

In the pooled analysis of RCTs, apart from local irritation immediately after injection, temporary headache was the only relevant, and possibly treatment-related, adverse event. Headache occurred in 13.6% (n = 8) of the BTA group and 9.3% (n = 7) of the placebo group (P = .44). Compared with antidepressants such as citalopram, where approximately 38.6% of patients report a moderate or severe side-effect burden,21 BTA is well tolerated.

Are other studies underway?

Larger studies are being conducted,35 mainly to confirm what pilot studies have shown. It would be interesting to discover other predictors of response and if different dosing and injection configurations could strengthen the response rate and extend the duration of effect.

Because of the cosmetic effects of BTA, further studies are needed to address the problem of blinding. In earlier studies, raters were blinded during appointments because patients wore surgical caps that covered their glabellar region.3,10 Patients did not know their treatment intervention, but 52% to 90% of patients guessed correctly.3,10,11 Although unblinding is a common problem in “blinded” trials in which some researchers have reported >75% of participants and raters guessed the intervention correctly,36 it is a particularly sensitive area in studies that involve a change in appearance because it is almost impossible to prevent someone from looking in a mirror.

Summing up

Botulinum toxin for depression is not ready for prime time. The FDA has not approved its use for psychiatric indications, and Medicare and commercial insurance do not reimburse for this procedure as a treatment for depression. Patients who request BTA for depression must be informed that this use is off-label.

For now, we recommend psychotherapy or medication management, or both, for most patients with major depression. In addition, until larger studies are done, we recommend that patients who are interested in BTA for depression use it as an add-on to conventional treatment. However, if larger studies replicate the findings of the smaller studies we have described, botulinum toxin could become a novel therapeutic agent in the fight against depression.

Bottom Line

In pilot studies, botulinum toxin A (BTA) has shown efficacy in improving symptoms of depression. Although considered safe, BTA is not FDA-approved for psychiatric indications, and Medicare and commercial insurance do not reimburse for this procedure for depression. Larger studies are underway to determine if this novel treatment can be introduced into practice.

Related Resources

• Wollmer MA, Magid M, Kruger THC. Botulinum toxin treatment in depression. In: Bewley A, Taylor RE, Reichenberg JS, et al, eds. Practical psychodermatology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2014:216-219.

• Botox for depression. www.botoxfordepression.com.

• Botox and depression. www.botoxanddepression.com.

Drug Brand Names

Botulinum toxin A • Botox

Citalopram • Celexa

Acknowledgments

We thank the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation for granting Dr. Magid a young investigator award and for continuing to invest in innovative research ideas. We thank Dr. Eric Finzi, MD, PhD, Axel Wollmer, MD, and Tillmann Krüger, MD, for their continued collaboration in this area of research.

Disclosures

In July 2011, Dr. Magid received a young investigator award from the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation for her study on treating depression using botulinum toxin (Grant number 17648). In November 2012, after completion and as a result of the study on treating depression using botulinum toxin, Dr. Magid became a consultant with Allergan to discuss study findings. In September 2015, Dr. Magid became a speaker for IPSEN Innovation. Dr. Reichenberg is married to Dr. Magid. Dr. Reichenberg has no other conflicts of interest to disclose.

Psychiatry is experiencing a major paradigm shift.1 No longer is depression a disease of norepinephrine and serotonin deficiency. Today, we are exploring inflammation, methylation, epigenetics, and neuroplasticity as major players; we are using innovative treatment interventions such as ketamine, magnets, psilocin, anti-inflammatories, and even botulinum toxin.

In 2006, dermatologist Eric Finzi, MD, PhD, reported a case series of 10 depressed patients who were given a single course of botulinum toxin A (BTA, onabotulinum-toxinA) injections in the forehead.2 After 2 months, 9 out of the 10 patients were no longer depressed. The 10th patient, who reported improvement in symptoms but not remission, was the only patient with bipolar depression.

As a psychiatrist (M.M.) and a dermatologist (J.R.), we conducted a randomized controlled trial3 to challenge the difficult-to-swallow notion that a cosmetic intervention could help severely depressed patients. After reporting our positive findings and hearing numerous encouraging patient testimonials, we present a favorable review on the treatment of depression using BTA. We also present the top 10 questions we are asked at lectures about this novel treatment.

A deadly toxin used to treat medical conditions

Botulinum toxin is one of the deadliest substance known to man.4 It was named after the gram-positive bacterium Clostridium botulinum, which causes so-called floppy baby syndrome in infants who eat contaminated honey. Botulinum toxin prevents nerves from releasing acetylcholine, which causes muscle paralysis.

In the wrong hands, botulinum toxin can be exploited for chemical warfare.4 However, doctors are using it to treat >50 medical conditions, including migraine, cervical dystonia, strabismus, overactive bladder, urinary incontinence, excessive sweating, muscle spasm, and now depression.5,6 In 2014, BTA was the top cosmetic treatment in the United States, with >3 million procedures performed, generating more than 1 billion dollars in revenue.7

The most common site injected with BTA for cosmetic treatments is the glabellar region, which is the area directly above and in between the eyebrows (ie, the lower forehead). The glabella comprises 2 main muscles: the central procerus flanked by a pair of corrugators (Figure). When expressing fear, anger, sadness, or anguish, these muscles contract, causing the appearance of 2 vertical wrinkles, referred to as the “11s.” The wrinkles also can form the shape of an upside-down “U,” known as the omega sign.8 BTA prevents contraction of these muscles and therefore prevents the appearance of a furrowed brow. During cosmetic procedures, approximately 20 to 50 units of BTA are spread out over 5 glabellar injection sites.9 A similar technique is being used in studies of BTA for depression2,3,10,11 (Figure).

BTA for depression is new to the mental health world but, before psychiatrists caught on, dermatologists were aware that BTA could improve quality of life,12 reduce negative emotions,13 and increase feelings of well-being.14

The evidence

To date, there have been 2 case series,2,15 3 randomized control trials (RCTs),3,10,11 1 pooled analysis,16,17 and 1 meta-analysis18 looking at botulinum for depression (Table 1).2,10,11,15-17 In each trial, a single treatment of BTA (ie, 1 doctor’s visit; 29 to 40 units of BTA distributed into 5 glabellar injections sites), was the intervention studied.2

The first case series, by Finzi and Wasserman2 is described above. A second case series, published in 2013, describes 50 female patients, one-half depressed and one-half non-depressed, all of whom received 20 units of BTA into the glabella.15 At 12 weeks, depression scores in the depressed group had decreased by 54% (14.9 point drop on Beck Depression Inventory [BDI], P < .001) and self-esteem scores had increased significantly. In non-depressed participants, depression scores and self-esteem scores remained constant throughout the 12 weeks.

A pooled analysis reported results of 3 RCTs16,17 consisting of a total of 134 depressed patients, males and females age 18 to 65 who received BTA (n = 59) or placebo (n = 74) into the glabellar region. At the end of 6 weeks, BDI scores in the depressed group had decreased by 47.4% (14.3 points) compared with a 16.2% decrease (5.1 points) in the placebo group. This corresponds to a 52.5% vs 8.0% response rate and a 42.4% vs 8.0% remission rate, respectively (Table 1,1,2,10,11,15-17). There was no difference between the 2 groups in sex, age, depression severity, and number of antidepressants being taken. Females received 29 units and males received 10 to 11 units more to account for higher muscle mass (Figure).

Depression as measured by the physician-administered Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) and the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale showed similar reduction in overall scores (−45.7% vs −14.6%), response rates (54.2% vs 10.7%) and remission rates (30.5% vs 6.7%) with BTA.

Although these improvements in depression scores do not reach those seen with electroconvulsive therapy,19,20 they are comparable to placebo-controlled studies of antidepressants.21,22

Doesn’t this technique work because people who look better, feel better?

Aesthetic improvement alone is unlikely to explain the entire story. A recent study showed that improvement in wrinkle score did not correlate with improvement in mood.23 Furthermore, some patients in RCTs did not like the cosmetic effects of BTA but still reported feeling less depressed after treatment.10

How might it work?

Several theories about the mechanism of action have been proposed:

• The facial feedback hypothesis dates to Charles Darwin in 1872: Facial movements influence emotional states. Numerous studies have confirmed this. Strack et al24 found that patients asked to smile while reading comics found them to be funnier. Ekman et al25 found that imitating angry facial expressions made body temperature and heart rate rise. Dialectical behavioral therapy expert Marsha Linehan recognized the importance of modifying facial expressions (from grimacing to smiling) and posture (from clenched fists to open hands) when feeling distressed, because it is hard to feel “willful” when your “mind is going one way and your body is going another.”26 Accordingly, for a person who continuously “looks” depressed or distressed, reducing the anguished facial expression using botulinum toxin might diminish the entwined negative emotions.

• A more pleasant facial expression improves social interactions, which leads to improvement in self-esteem and mood. Social biologists argue that (1) we are attracted to those who have more pleasant facial expressions and (2) we steer clear of those who appear angry or depressed (a negative facial expression, such as a growling dog, is perceived as a threat). Therefore, anyone who looks depressed might have less rewarding interpersonal interactions, which can contribute to a poor mood.

On a similar note, mirror neurons are regions in the brain that are activated by witnessing another person’s emotional cues. When our mirror neurons light up, we can feel an observed experience, which is why we often feel nervous around anxious people, or cringe when we see others get hurt, or why we might prefer engaging with people who appear happier. It is possible that, after BTA injection, a person’s social connectivity is improved because of a more positive reciprocal firing of mirror neurons.

• BTA leads to direct and indirect neurochemical changes in the brain that can reduce depression. Functional MRI studies have shown that after glabellar BTA injections, the amygdala was less responsive to negative stimuli.27,28 For example, patients who were treated with BTA and then shown pictures of angry people had an attenuated amygdala response to the photos.

This is an important finding, especially for patients who have been traumatized. After a traumatic event, the amygdala “remembers” what happened, which is good, in some ways (it prevents us from getting into a similar dangerous situation), but bad in others (the traumatized amygdala may falsely perceive a non-threatening stimuli as threatening). A hypervigilant amygdala can lead to an out-of-proportion fear response, depression, and anxiety. Therefore, quelling an overactive amygdala with BTA could improve emotional dysregulation and posttraumatic disorders.

Many of our patients reported that, after BTA injection, “traumatic events didn’t feel as traumatizing,” as one said. The emotional pain and rumination that often follow a life stressor “does not overstay its welcome” and patients are able to “move on” more quickly.

It is unknown why the amygdala is quieted after BTA; researchers hypothesize that BTA suppresses facial feedback signals from the forehead branch of the trigeminal nerve to the brain. Another hypothesis is that BTA is directly transported by the trigeminal nerve into the brain and exerts central pharmacological effects on the amygdala.29 This theory has only been studied in rat models.30

When does it start working? How long does it last?

From what we know, BTA for depression could start working as early as 2 weeks and could last as long as 6 months. In one RCT, the earliest follow-up was 2 weeks,10 at which time the depressed patients had responded to botulinum toxin (P ≤ .05). In the other 2 controlled trials, the earliest follow-up was 3 weeks, at which time a more robust response was seen (P < .001). Aesthetically, BTA usually lasts 3 months. It is unclear how long the antidepressant effects last but, in the longest trial,3 depression symptoms continued to improve at 6 months, after cosmetic effects had worn off.

These findings raise a series of questions:

• Do mood effects outlast cosmetic effects? If so, why?

• Does botulinum toxin start to work sooner than 2 weeks?

• Will adherence improve if a patient has to be treated only every 6 months?

In our clinical experience, depressed patients who responded to BTA injection report a slow resurfacing of depressive symptoms 4 to 6 months after treatment, at which point they usually return for “maintenance treatment” (same dosing, same injection configuration).

Will psychiatrists administer the treatment?

Any physician or physician extender can, when properly trained, inject BTA. The question is: Do psychiatrists want to? Administrating botulinum toxin requires more labor and preparation than prescribing a drug (Table 2,31) and requires placing hands on patients. Depending on the type of psychiatric practice, this may be a “deal-breaker” for some providers, such as those in a psychoanalytic practice who might worry about boundaries.

As a basis for comparison, despite several indications for BTA for headache and neurologic conditions, few neurologists have added botulinum toxin to their practice. Dermatologists who are comfortable seeing psychiatric patients or family practitioners, who are already set up for injection procedures, could become custodians of this intervention.

Which patients are candidates for the treatment?

Patients with anxious or agitated depression might be ideal candidates for BTA injection. A recent study looked at predictors of response: Patients with a high agitation score (as measured on item 9 of the HAM-D) were more likely to respond, with a sensitivity of 100%, a specificity of 56%, and an overall precision of 78%.32 So far, no other predictors of response have been clearly identified. Higher baseline wrinkle scores do not predict better response.23 Sex and age do not have any predictive value. The treatment appears to be equally effective in males and females; because only a handful of males have been treated (n = 14), however, these patients need to be studied further.

Is botulinum toxin better as monotherapy or augmentation strategy?

So far, it appears to be equally effective as monotherapy or augmentation strategy,16 but more studies are needed.

How expensive is it?

Estimates of patient cost include the cost of the product and the professional fee for injection. As a point of reference, for cosmetic purposes, depending on practice location, dermatologists charge $11 to $20 per unit of BTA. Therefore, 1 treatment of BTA for depression (29 to 40 units) can cost a patient $319 to $800.

When treating a patient with BTA for medical indications, such as tension headache, insurance often reimburses the physician for the BTA at cost (paid with a J code: J0585) and pay an injection fee (a procedure code) of $150 to $200. A recent analysis of cost-effectiveness estimated that BTA for depression would cost a patient $1,200 to $1,600 annually.33 Compared with the price of branded medications (eg, $500 to $2,000 annually)33 plus weekly psychotherapy (eg, $2,000 to $5,000 annually), BTA may be a cost-effective option for patients who do not respond to conventional treatments. Of course, for patients who tolerate and respond to generic medications or have a therapist who charges on a sliding scale, BTA is not the most cost-effective option.

What about injecting other areas of the face?

We’ve thought about it but haven’t tried it. There are several muscles around the mouth that allow us to smile and frown. BTA injections in the depressor anguli oris, a muscle around the mouth that is largely responsible for frowning, could treat depression. However, if the mechanism of action is via amygdala desensitization through the trigeminal nerve, treating mouth frown muscles might not work.

Is it safe?

BTA in the glabella has an exceptionally good safety profile.9,31,34 Adverse reactions, which include eyelid droop, pain, bruising, and redness at the injection site, are minor and temporary.9 In addition, BTA has few drug–drug interactions. The biggest complaint for most patients is discomfort upon injection, which often is described as feeling like “an ant bite.”

In the pooled analysis of RCTs, apart from local irritation immediately after injection, temporary headache was the only relevant, and possibly treatment-related, adverse event. Headache occurred in 13.6% (n = 8) of the BTA group and 9.3% (n = 7) of the placebo group (P = .44). Compared with antidepressants such as citalopram, where approximately 38.6% of patients report a moderate or severe side-effect burden,21 BTA is well tolerated.

Are other studies underway?

Larger studies are being conducted,35 mainly to confirm what pilot studies have shown. It would be interesting to discover other predictors of response and if different dosing and injection configurations could strengthen the response rate and extend the duration of effect.

Because of the cosmetic effects of BTA, further studies are needed to address the problem of blinding. In earlier studies, raters were blinded during appointments because patients wore surgical caps that covered their glabellar region.3,10 Patients did not know their treatment intervention, but 52% to 90% of patients guessed correctly.3,10,11 Although unblinding is a common problem in “blinded” trials in which some researchers have reported >75% of participants and raters guessed the intervention correctly,36 it is a particularly sensitive area in studies that involve a change in appearance because it is almost impossible to prevent someone from looking in a mirror.

Summing up

Botulinum toxin for depression is not ready for prime time. The FDA has not approved its use for psychiatric indications, and Medicare and commercial insurance do not reimburse for this procedure as a treatment for depression. Patients who request BTA for depression must be informed that this use is off-label.

For now, we recommend psychotherapy or medication management, or both, for most patients with major depression. In addition, until larger studies are done, we recommend that patients who are interested in BTA for depression use it as an add-on to conventional treatment. However, if larger studies replicate the findings of the smaller studies we have described, botulinum toxin could become a novel therapeutic agent in the fight against depression.

Bottom Line

In pilot studies, botulinum toxin A (BTA) has shown efficacy in improving symptoms of depression. Although considered safe, BTA is not FDA-approved for psychiatric indications, and Medicare and commercial insurance do not reimburse for this procedure for depression. Larger studies are underway to determine if this novel treatment can be introduced into practice.

Related Resources

• Wollmer MA, Magid M, Kruger THC. Botulinum toxin treatment in depression. In: Bewley A, Taylor RE, Reichenberg JS, et al, eds. Practical psychodermatology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2014:216-219.

• Botox for depression. www.botoxfordepression.com.

• Botox and depression. www.botoxanddepression.com.

Drug Brand Names

Botulinum toxin A • Botox

Citalopram • Celexa

Acknowledgments

We thank the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation for granting Dr. Magid a young investigator award and for continuing to invest in innovative research ideas. We thank Dr. Eric Finzi, MD, PhD, Axel Wollmer, MD, and Tillmann Krüger, MD, for their continued collaboration in this area of research.

Disclosures

In July 2011, Dr. Magid received a young investigator award from the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation for her study on treating depression using botulinum toxin (Grant number 17648). In November 2012, after completion and as a result of the study on treating depression using botulinum toxin, Dr. Magid became a consultant with Allergan to discuss study findings. In September 2015, Dr. Magid became a speaker for IPSEN Innovation. Dr. Reichenberg is married to Dr. Magid. Dr. Reichenberg has no other conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Nasrallah HA. 10 Recent paradigm shifts in the neurobiology and treatment of depression. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(2):10-13.

2. Finzi E, Wasserman E. Treatment of depression with botulinum toxin A: a case series. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32(5):645-649; discussion 649-650.

3. Magid M, Reichenberg JS, Poth PE, et al. Treatment of major depressive disorder using botulinum toxin A: a 24-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(8):837-844.

4. Koussoulakos S. Botulinum neurotoxin: the ugly duckling. Eur Neurol. 2008;61(6):331-342.

5. Chen S. Clinical uses of botulinum neurotoxins: current indications, limitations and future developments. Toxins (Basel). 2012;4(10):913-939.

6. Bhidayasiri R, Truong DD. Expanding use of botulinum toxin. J Neurol Sci. 2005;235(1-1):1-9.

7. Cosmetic surgery national data bank statistics. American Society for Asethetic Plastic Surgery. http://www.surgery. org/sites/default/files/2014-Stats.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed May 30, 2015.

8. Shorter E. Darwin’s contribution to psychiatry. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195(6):473-474.

9. Winter L, Spiegel J. Botulinum toxin type-A in the treatment of glabellar lines. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2009;3:1-4.

10. Wollmer MA, de Boer C, Kalak N, et al. Facing depression with botulinum toxin: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46(5):574-581.

11. Finzi E, Rosenthal NE. Treatment of depression with onabotulinumtoxinA: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;52:1-6.

12. Hexsel D, Brum C, Porto MD, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction of patients after full-face injections of abobotulinum toxin type A: a randomized, phase IV clinical trial. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12(12):1363-1367.

13. Lewis MB, Bowler PJ. Botulinum toxin cosmetic therapy correlates with a more positive mood. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2009;8(1):24-26.

14. Sommer B, Zschocke I, Bergfeld D, et al. Satisfaction of patients after treatment with botulinum toxin for dynamic facial lines. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29(5):456-460.

15. Hexsel D, Brum C, Siega C, et al. Evaluation of self‐esteem and depression symptoms in depressed and nondepressed subjects treated with onabotulinumtoxina for glabellar lines. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39(7):1088-1096.

16. Magid M, Reichenberg JS, Finzi E, et al. Treating depression with botulinum toxin: update and meta-analysis from clinic trials. Paper presented at: XVI World Congress of Psychiatry; September 14-18, 2014; Madrid, Spain.

17. Magid M, Finzi E, Kruger TH, et al. Treating depression with botulinum toxin: a pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2015;48(6):205-210.

18. Parsaik A, Mascarenhas S, Hashmi A, et al. Role of botulinum toxin in depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Pract. In press.

19. Scott AI, ed. The ECT handbook, 2nd ed. The third report of the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Special Committee of ECT. London, United Kingdom: The Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2005.

20. Ren J, Li H, Palaniyappan L, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation versus electroconvulsive therapy for major depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2014;51:181-189.

21. Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al; STAR*D Study Team. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR* D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):28-40.

22. Gibbons RD, Hur K, Brown CH, et al. Benefits from antidepressants: synthesis of 6-week patient-level outcomes from double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trials of fluoxetine and venlafaxine. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(6):572-579.

23. Reichenberg JS, Magid M, Keeling B. Botulinum toxin for depression: does the presence of rhytids predict response? Presented at: Texas Dermatology Society; May 2015; Bastrop, Texas.

24. Strack F, Martin LL, Stepper S. Inhibiting and facilitating conditions of the human smile: a nonobtrusive test of the facial feedback hypothesis. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(5):768-777.

25. Ekman P, Levenson RW, Friesen WV. Autonomic nervous system activity distinguishes among emotions. Science. 1983;221(4616):1208-1210.

26. Linehan MM. DBT skills training manual, 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Publications; 2014.

27. Hennenlotter A, Dresel C, Castrop F, et al. The link between facial feedback and neural activity within central circuitries of emotion—new insights from botulinum toxin-induced denervation of frown muscles. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19(3):537-542.

28. Kim MJ, Neta M, Davis FC, et al. Botulinum toxin-induced facial muscle paralysis affects amygdala responses to the perception of emotional expressions: preliminary findings from an A-B-A design. Biol Mood Anxiety Disord. 2014;4:11.

29. Mazzocchio R, Caleo M. More than at the neuromuscular synapse: actions of botulinum neurotoxin A in the central nervous system. Neuroscientist. 2015;21(1):44-61.

30. Antonucci F, Rossi C, Gianfranceschi L, et al. Long-distance retrograde effects of botulinum neurotoxin A. J Neurosci. 2008;28(14):3689-3696.

31. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Medication guide: botox. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/drugsafety/ucm176360.pdf. Updated September 2013. Accessed June 7, 2015.

32. Wollmer MA, Kalak N, Jung S, et al. Agitation predicts response of depression to botulinum toxin treatment in a randomized controlled trial. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:36.

33. Beer K. Cost effectiveness of botulinum toxins for the treatment of depression: preliminary observations. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9(1):27-30.

34. Brin MF, Boodhoo TI, Pogoda JM, et al. Safety and tolerability of onabotulinumtoxinA in the treatment of facial lines: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from global clinical registration studies in 1678 participants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61(6):961-970.e1-11.

35. Botulinum toxin and depression. ClinicalTrials.gov. https:// clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=botulinum+toxin+and+ depression&Search=Search. Accessed June 1, 2015.

36. Rabkin JG, Markowitz JS, Stewart J, et al. How blind is blind? Assessment of patient and doctor medication guesses in a placebo-controlled trial of imipramine and phenelzine. Psychiatry Res. 1986;19(1):75-86.

1. Nasrallah HA. 10 Recent paradigm shifts in the neurobiology and treatment of depression. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(2):10-13.

2. Finzi E, Wasserman E. Treatment of depression with botulinum toxin A: a case series. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32(5):645-649; discussion 649-650.

3. Magid M, Reichenberg JS, Poth PE, et al. Treatment of major depressive disorder using botulinum toxin A: a 24-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(8):837-844.

4. Koussoulakos S. Botulinum neurotoxin: the ugly duckling. Eur Neurol. 2008;61(6):331-342.

5. Chen S. Clinical uses of botulinum neurotoxins: current indications, limitations and future developments. Toxins (Basel). 2012;4(10):913-939.

6. Bhidayasiri R, Truong DD. Expanding use of botulinum toxin. J Neurol Sci. 2005;235(1-1):1-9.

7. Cosmetic surgery national data bank statistics. American Society for Asethetic Plastic Surgery. http://www.surgery. org/sites/default/files/2014-Stats.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed May 30, 2015.

8. Shorter E. Darwin’s contribution to psychiatry. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195(6):473-474.

9. Winter L, Spiegel J. Botulinum toxin type-A in the treatment of glabellar lines. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2009;3:1-4.

10. Wollmer MA, de Boer C, Kalak N, et al. Facing depression with botulinum toxin: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46(5):574-581.

11. Finzi E, Rosenthal NE. Treatment of depression with onabotulinumtoxinA: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;52:1-6.

12. Hexsel D, Brum C, Porto MD, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction of patients after full-face injections of abobotulinum toxin type A: a randomized, phase IV clinical trial. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12(12):1363-1367.

13. Lewis MB, Bowler PJ. Botulinum toxin cosmetic therapy correlates with a more positive mood. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2009;8(1):24-26.

14. Sommer B, Zschocke I, Bergfeld D, et al. Satisfaction of patients after treatment with botulinum toxin for dynamic facial lines. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29(5):456-460.

15. Hexsel D, Brum C, Siega C, et al. Evaluation of self‐esteem and depression symptoms in depressed and nondepressed subjects treated with onabotulinumtoxina for glabellar lines. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39(7):1088-1096.

16. Magid M, Reichenberg JS, Finzi E, et al. Treating depression with botulinum toxin: update and meta-analysis from clinic trials. Paper presented at: XVI World Congress of Psychiatry; September 14-18, 2014; Madrid, Spain.

17. Magid M, Finzi E, Kruger TH, et al. Treating depression with botulinum toxin: a pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2015;48(6):205-210.

18. Parsaik A, Mascarenhas S, Hashmi A, et al. Role of botulinum toxin in depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Pract. In press.

19. Scott AI, ed. The ECT handbook, 2nd ed. The third report of the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Special Committee of ECT. London, United Kingdom: The Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2005.

20. Ren J, Li H, Palaniyappan L, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation versus electroconvulsive therapy for major depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2014;51:181-189.

21. Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al; STAR*D Study Team. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR* D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):28-40.

22. Gibbons RD, Hur K, Brown CH, et al. Benefits from antidepressants: synthesis of 6-week patient-level outcomes from double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trials of fluoxetine and venlafaxine. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(6):572-579.

23. Reichenberg JS, Magid M, Keeling B. Botulinum toxin for depression: does the presence of rhytids predict response? Presented at: Texas Dermatology Society; May 2015; Bastrop, Texas.

24. Strack F, Martin LL, Stepper S. Inhibiting and facilitating conditions of the human smile: a nonobtrusive test of the facial feedback hypothesis. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(5):768-777.

25. Ekman P, Levenson RW, Friesen WV. Autonomic nervous system activity distinguishes among emotions. Science. 1983;221(4616):1208-1210.

26. Linehan MM. DBT skills training manual, 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Publications; 2014.

27. Hennenlotter A, Dresel C, Castrop F, et al. The link between facial feedback and neural activity within central circuitries of emotion—new insights from botulinum toxin-induced denervation of frown muscles. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19(3):537-542.

28. Kim MJ, Neta M, Davis FC, et al. Botulinum toxin-induced facial muscle paralysis affects amygdala responses to the perception of emotional expressions: preliminary findings from an A-B-A design. Biol Mood Anxiety Disord. 2014;4:11.

29. Mazzocchio R, Caleo M. More than at the neuromuscular synapse: actions of botulinum neurotoxin A in the central nervous system. Neuroscientist. 2015;21(1):44-61.

30. Antonucci F, Rossi C, Gianfranceschi L, et al. Long-distance retrograde effects of botulinum neurotoxin A. J Neurosci. 2008;28(14):3689-3696.

31. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Medication guide: botox. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/drugsafety/ucm176360.pdf. Updated September 2013. Accessed June 7, 2015.

32. Wollmer MA, Kalak N, Jung S, et al. Agitation predicts response of depression to botulinum toxin treatment in a randomized controlled trial. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:36.

33. Beer K. Cost effectiveness of botulinum toxins for the treatment of depression: preliminary observations. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9(1):27-30.

34. Brin MF, Boodhoo TI, Pogoda JM, et al. Safety and tolerability of onabotulinumtoxinA in the treatment of facial lines: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from global clinical registration studies in 1678 participants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61(6):961-970.e1-11.

35. Botulinum toxin and depression. ClinicalTrials.gov. https:// clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=botulinum+toxin+and+ depression&Search=Search. Accessed June 1, 2015.

36. Rabkin JG, Markowitz JS, Stewart J, et al. How blind is blind? Assessment of patient and doctor medication guesses in a placebo-controlled trial of imipramine and phenelzine. Psychiatry Res. 1986;19(1):75-86.

Is your patient making the ‘wrong’ treatment choice?

Consultation/liaison (C/L) psychiatrists assess capacity in 1 of 6 consults,1 and these evaluations must be quick but systematic. Hospital time is precious, and asking for a psychiatry consult inevitably slows down the medical team’s efforts to care for sick or injured patients.

We suggest an approach our C/L service developed to rapidly weigh capacity’s three dimensions—risks, benefits, and patient decisions—to formulate appropriate opinions for the medical team.

A standard for capacity

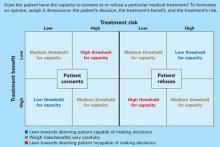

In most cases, capacity must be assessed and considered adequate before a patient can provide informed consent for a medical intervention. Because a patient might be capable of making some decisions but not others, the standard for determining capacity is not black and white but a sliding scale that depends on the magnitude of the decision being made.

As physicians, psychiatrists understand doctors’ frustrations when they believe a patient is making the wrong treatment choice. When the primary team turns to us, they want us to help determine the most appropriate course of action.

Capacity is determined by weighing whether the patient is competent to exercise his or her autonomy in making a decision about medical treatment. We do not assess global capacity; the goal is to provide an unbiased opinion about specific capacity for a given situation–“Does Mr. X have the ability to accept/refuse this treatment option presented to him?”

Capacity’s three dimensions. The means to achieve this goal are often complex. Roth et al2 proposed that capacity could be measured on a sliding scale. Wise and Rundell3 agreed and developed a two-dimension table to show that capacity can be evaluated at different thresholds, depending on the patient’s clinical situation. We expanded this model (Figure) to include three dimensions to consider when you evaluate capacity:

- risk of the proposed treatment (high vs. low)

- benefit of the treatment (high vs. low)

- the patient’s decision about the treatment (accept vs. refuse).

If a treatment’s benefits far outweigh the risks and the patient accepts that treatment, he is probably capable of making that decision and a lenient (low) threshold to establish capacity applies. If the same patient refuses the high-benefit, low-risk treatment, then he might be incapable of making that decision and a stringent (high) threshold to establish capacity comes into play. Our C/L service often uses this model when discussing capacity evaluations with the primary team. It explains why some capacity evaluations—when a patient agrees to a low-risk, high-benefit procedure—might take minutes, whereas others—those that fall into the medium threshold for capacity—take hours. Consider the following cases.

Figure 3-dimension model for evaluating capacity

Three cases: Is capacity evaluation needed?

Mr. X, age 25, was in a motor vehicle accident that caused trauma to his esophagus. He requires a feeding tube because he will be unable to eat for several weeks. The risk of the procedure (feeding tube placement) is low, and the benefit (getting possibly life-saving nutrition) is high.

If Mr. X refuses the feeding tube, he may be incapable of making this decision and would require a rigorous capacity evaluation (high-threshold capacity). If he consents, he is making a choice with which most reasonable people would agree, and establishing capacity would be less important (low-threshold capacity).

Mr. J, age 95, has congestive heart failure, diabetes, and liver disease. If he consents to a liver transplant—a treatment likely to be low-benefit and high-risk—he would require a rigorous capacity evaluation. If he refuses this surgical intervention, then more-lenient capacity criteria would apply.

Mrs. F, age 59, has breast cancer with metastases. Her oncologist is recommending bilateral mastectomy, radiation, chemotherapy, and an experimental treatment that has shown favorable results. The risk of treatment is high, and the benefit is unknown but most likely high. Since this is a high-risk, high-benefit intervention, the capacity threshold is medium. Whether she consents to or refuses treatment, you must weigh risks and benefits very carefully with her.

The primary team’s role

A common myth holds that only psychiatrists can determine capacity, but any physician can.4 The primary team may feel comfortable deciding a patient’s capacity without seeking consultation after asking the screening questions in Table 1.5,6 A patient who gives consistent and appropriate answers to these screening questions usually also can answer the more detailed questions psychiatrists would ask and thus has sufficient capacity.

When uncertainties remain after screening, we recommend that the primary team ask psychiatry for an opinion. Knowing what the primary team is thinking about a difficult case often helps the psychiatric consultant. So when consulting with psychiatry, we suggest that the primary team:

- clarify the question (such as, “Does Mrs. Z have the capacity to refuse dialysis?”)

- give an opinion about whether the patient does or does not have capacity and why.

When sharing of opinions was studied at institutions trying this idea, C/L teams agreed with the primary teams’ initial impression of patients’ capacity 80% of the time.4 Most consults occurred because the patient was refusing an intervention the primary team felt was “essential,” or the patient and primary team disagreed on code status. At our institution, anecdotal evidence shows that if the primary team spends a few minutes asking screening questions, the C/L service and primary team agree on the patient’s capacity >90% of the time.

Table 1

Primary team capacity evaluation: 5 W’s

Explain to the patient the treatment you recommend. Review risks and benefits of accepting and of refusing the treatment. Describe alternatives. Then ask these screening questions to assess capacity:

|