User login

What are the risk factors for pain after endometrial ablation?

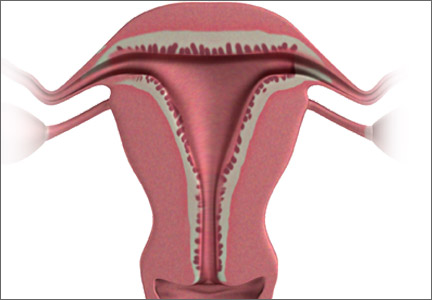

Heavy menstrual bleeding is a common gynecologic problem and can negatively affect a woman’s quality of life.1 Endometrial ablation is an effective treatment option.2 Despite its efficacy, however, endometrial ablation has failure rates ranging from 15% to 30%.3,4 Two consistent reasons for failure are persistent bleeding and new or worsening pain. Endometrial regrowth and intrauterine scarring are thought to be key factors in this pain process.5

Details of the trial

Wishall and colleagues conducted their retrospective cohort study using patient data from two large academic medical centers. The primary outcome was the development of new or worsening pain following endometrial ablation. The two most commonly used endometrial ablation devices in this study were thermal balloon ablation and bipolar radiofrequency ablation.

Twenty-three percent of patients developed new or worsening pain following the ablation, a finding in accordance with earlier studies looking specifically at pain after endometrial ablation.6 In addition, 19% of patients underwent hysterectomy after ablation—again, within the range commonly reported in the literature.3,4

Risk factors for new or worsening pain after ablation included a preprocedure history of dysmenorrhea or tubal sterilization. White race was protective of postprocedure new or worsening pain (adjusted OR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.34–0.89).

Risk factors for hysterectomy after ablation included a history of cesarean delivery (adjusted OR, 2.33; 95% CI, 1.05–5.16) and uterine abnormalities on imaging, including leiomyoma, adenomyosis, a thickened endometrial lining, and polyps (adjusted OR, 3.96; 95% CI, 1.25–12.56). When the ablation procedure was performed in an operating room, the risk of postprocedure hysterectomy decreased (adjusted OR, 0.24; 95% CI, 0.07–0.77). In histopathologic analysis of the hysterectomy specimens, leiomyomas or adenomyosis, or both, were the most common findings, consistent with other reports on pathologic findings in this setting.7

Placing these findings in context

Overall, the findings of Wishall and colleagues support those of other studies exploring endometrial ablation, an effective uterine-conserving procedure for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding. All conservative procedures have inherent failure rates and can lead to unintended adverse effects. Common reasons for failure after endometrial ablation include bleeding or pain, or both.

Although there are discrepancies between studies in regard to some of the individual predictors of failure or development of pain, the collection of retrospective studies on this subject to date have made it clear: There are predictors of treatment failure. Future efforts should focus on model development and prospective validation of these models to improve patient selection.

What this evidence means for practice

This study reinforces the idea that patient selection for conservative procedures such as endometrial ablation is one of the most important steps in the process. In light of these findings, I recommend that women with a history of dysmenorrhea or tubal sterilization be counseled about the potential for postprocedure pain and subsequent treatment failure.

— Matthew R. Hopkins, MD

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE Clinical Guideline CG44: Heavy Menstrual Bleeding. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg44. Published January 2007. Accessed January 18, 2015.

2. Lethaby A, Penninx J, Hickey M, Garry R, Marjoribanks J. Endometrial resection and ablation techniques for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(8):CD001501.

3. El-Nashar SA, Hopkins MR, Creedon DJ, et al. Prediction of treatment outcomes after global endometrial ablation. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(1):97–106.

4. Longinotti MK, Jacobson GF, Hung YY, Learman LA. Probability of hysterectomy after endometrial ablation. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(6):1214–1220.

5. Wortman M, Cholkeri A, McCausland AM, McCausland VM. Late-onset endometrial ablation failure (Loeaf)—etiology, treatment, and prevention [published online ahead of print October 31, 2014]. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. pii: S1553-4650(14)01484-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2014.10.020.

6. Thomassee MS, Curlin H, Yunker A, Anderson TL. Predicting pelvic pain after endometrial ablation: which preoperative patient characteristics are associated? J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20(5):642–647.

7. Carey ET, El-Nashar SA, Hopkins MR, Creedon DJ, Cliby WA, Famuyide AO. Pathologic characteristics of hysterectomy specimens in women undergoing hysterectomy after global endometrial ablation. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18(1):96–99.

Heavy menstrual bleeding is a common gynecologic problem and can negatively affect a woman’s quality of life.1 Endometrial ablation is an effective treatment option.2 Despite its efficacy, however, endometrial ablation has failure rates ranging from 15% to 30%.3,4 Two consistent reasons for failure are persistent bleeding and new or worsening pain. Endometrial regrowth and intrauterine scarring are thought to be key factors in this pain process.5

Details of the trial

Wishall and colleagues conducted their retrospective cohort study using patient data from two large academic medical centers. The primary outcome was the development of new or worsening pain following endometrial ablation. The two most commonly used endometrial ablation devices in this study were thermal balloon ablation and bipolar radiofrequency ablation.

Twenty-three percent of patients developed new or worsening pain following the ablation, a finding in accordance with earlier studies looking specifically at pain after endometrial ablation.6 In addition, 19% of patients underwent hysterectomy after ablation—again, within the range commonly reported in the literature.3,4

Risk factors for new or worsening pain after ablation included a preprocedure history of dysmenorrhea or tubal sterilization. White race was protective of postprocedure new or worsening pain (adjusted OR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.34–0.89).

Risk factors for hysterectomy after ablation included a history of cesarean delivery (adjusted OR, 2.33; 95% CI, 1.05–5.16) and uterine abnormalities on imaging, including leiomyoma, adenomyosis, a thickened endometrial lining, and polyps (adjusted OR, 3.96; 95% CI, 1.25–12.56). When the ablation procedure was performed in an operating room, the risk of postprocedure hysterectomy decreased (adjusted OR, 0.24; 95% CI, 0.07–0.77). In histopathologic analysis of the hysterectomy specimens, leiomyomas or adenomyosis, or both, were the most common findings, consistent with other reports on pathologic findings in this setting.7

Placing these findings in context

Overall, the findings of Wishall and colleagues support those of other studies exploring endometrial ablation, an effective uterine-conserving procedure for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding. All conservative procedures have inherent failure rates and can lead to unintended adverse effects. Common reasons for failure after endometrial ablation include bleeding or pain, or both.

Although there are discrepancies between studies in regard to some of the individual predictors of failure or development of pain, the collection of retrospective studies on this subject to date have made it clear: There are predictors of treatment failure. Future efforts should focus on model development and prospective validation of these models to improve patient selection.

What this evidence means for practice

This study reinforces the idea that patient selection for conservative procedures such as endometrial ablation is one of the most important steps in the process. In light of these findings, I recommend that women with a history of dysmenorrhea or tubal sterilization be counseled about the potential for postprocedure pain and subsequent treatment failure.

— Matthew R. Hopkins, MD

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Heavy menstrual bleeding is a common gynecologic problem and can negatively affect a woman’s quality of life.1 Endometrial ablation is an effective treatment option.2 Despite its efficacy, however, endometrial ablation has failure rates ranging from 15% to 30%.3,4 Two consistent reasons for failure are persistent bleeding and new or worsening pain. Endometrial regrowth and intrauterine scarring are thought to be key factors in this pain process.5

Details of the trial

Wishall and colleagues conducted their retrospective cohort study using patient data from two large academic medical centers. The primary outcome was the development of new or worsening pain following endometrial ablation. The two most commonly used endometrial ablation devices in this study were thermal balloon ablation and bipolar radiofrequency ablation.

Twenty-three percent of patients developed new or worsening pain following the ablation, a finding in accordance with earlier studies looking specifically at pain after endometrial ablation.6 In addition, 19% of patients underwent hysterectomy after ablation—again, within the range commonly reported in the literature.3,4

Risk factors for new or worsening pain after ablation included a preprocedure history of dysmenorrhea or tubal sterilization. White race was protective of postprocedure new or worsening pain (adjusted OR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.34–0.89).

Risk factors for hysterectomy after ablation included a history of cesarean delivery (adjusted OR, 2.33; 95% CI, 1.05–5.16) and uterine abnormalities on imaging, including leiomyoma, adenomyosis, a thickened endometrial lining, and polyps (adjusted OR, 3.96; 95% CI, 1.25–12.56). When the ablation procedure was performed in an operating room, the risk of postprocedure hysterectomy decreased (adjusted OR, 0.24; 95% CI, 0.07–0.77). In histopathologic analysis of the hysterectomy specimens, leiomyomas or adenomyosis, or both, were the most common findings, consistent with other reports on pathologic findings in this setting.7

Placing these findings in context

Overall, the findings of Wishall and colleagues support those of other studies exploring endometrial ablation, an effective uterine-conserving procedure for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding. All conservative procedures have inherent failure rates and can lead to unintended adverse effects. Common reasons for failure after endometrial ablation include bleeding or pain, or both.

Although there are discrepancies between studies in regard to some of the individual predictors of failure or development of pain, the collection of retrospective studies on this subject to date have made it clear: There are predictors of treatment failure. Future efforts should focus on model development and prospective validation of these models to improve patient selection.

What this evidence means for practice

This study reinforces the idea that patient selection for conservative procedures such as endometrial ablation is one of the most important steps in the process. In light of these findings, I recommend that women with a history of dysmenorrhea or tubal sterilization be counseled about the potential for postprocedure pain and subsequent treatment failure.

— Matthew R. Hopkins, MD

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE Clinical Guideline CG44: Heavy Menstrual Bleeding. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg44. Published January 2007. Accessed January 18, 2015.

2. Lethaby A, Penninx J, Hickey M, Garry R, Marjoribanks J. Endometrial resection and ablation techniques for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(8):CD001501.

3. El-Nashar SA, Hopkins MR, Creedon DJ, et al. Prediction of treatment outcomes after global endometrial ablation. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(1):97–106.

4. Longinotti MK, Jacobson GF, Hung YY, Learman LA. Probability of hysterectomy after endometrial ablation. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(6):1214–1220.

5. Wortman M, Cholkeri A, McCausland AM, McCausland VM. Late-onset endometrial ablation failure (Loeaf)—etiology, treatment, and prevention [published online ahead of print October 31, 2014]. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. pii: S1553-4650(14)01484-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2014.10.020.

6. Thomassee MS, Curlin H, Yunker A, Anderson TL. Predicting pelvic pain after endometrial ablation: which preoperative patient characteristics are associated? J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20(5):642–647.

7. Carey ET, El-Nashar SA, Hopkins MR, Creedon DJ, Cliby WA, Famuyide AO. Pathologic characteristics of hysterectomy specimens in women undergoing hysterectomy after global endometrial ablation. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18(1):96–99.

1. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE Clinical Guideline CG44: Heavy Menstrual Bleeding. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg44. Published January 2007. Accessed January 18, 2015.

2. Lethaby A, Penninx J, Hickey M, Garry R, Marjoribanks J. Endometrial resection and ablation techniques for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(8):CD001501.

3. El-Nashar SA, Hopkins MR, Creedon DJ, et al. Prediction of treatment outcomes after global endometrial ablation. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(1):97–106.

4. Longinotti MK, Jacobson GF, Hung YY, Learman LA. Probability of hysterectomy after endometrial ablation. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(6):1214–1220.

5. Wortman M, Cholkeri A, McCausland AM, McCausland VM. Late-onset endometrial ablation failure (Loeaf)—etiology, treatment, and prevention [published online ahead of print October 31, 2014]. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. pii: S1553-4650(14)01484-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2014.10.020.

6. Thomassee MS, Curlin H, Yunker A, Anderson TL. Predicting pelvic pain after endometrial ablation: which preoperative patient characteristics are associated? J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20(5):642–647.

7. Carey ET, El-Nashar SA, Hopkins MR, Creedon DJ, Cliby WA, Famuyide AO. Pathologic characteristics of hysterectomy specimens in women undergoing hysterectomy after global endometrial ablation. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18(1):96–99.

Is the LNG–IUS as effective as endometrial ablation in relieving menorrhagia?

Historically, hysterectomy was the only alternative to medical treatment. However, endometrial ablation and the LNG-IUS have both proved to be effective, and less invasive, therapies.

Until recently, the average ObGyn in the United States placed only about four intrauterine devices (IUDs) a year. This low volume made many practitioners reluctant to prescribe the IUD, but we are seeing a resurgence in use.

Details of the study

This analysis, which meets Quality of Reporting of Meta-analyses (QUOROM) guidelines, was restricted to studies that included pre- and posttreatment assessment of menstrual blood loss using the Pictorial Blood Loss Assessment Chart (PBLAC).1 Although the PBLAC has limitations, it is one of the more practical, objective measures available. The PBLAC score does not yield an exact measure of blood loss, but it has been found to correlate well with menstrual blood volume. When it is used to evaluate menstrual blood loss of 80 mL or more, its specificity and sensitivity exceed 80%.

In reviewing randomized, controlled trials for this study, the authors found only a small number (n=6) that met their criteria, and those studies involved a relatively small number of patients (LNG-IUS, n=196; endometrial ablation, n=194), limiting the statistical power of this investigation.

Both treatment modalities were associated with a reduction in menstrual blood loss, and the degree of the reduction was similar between modalities at 6, 12, and 24 months.

The treatment failure rate was not time-adjusted; nor was the study powered to address the question of failure.

Only two studies assessed the PBLAC score at 6 months, five did so at 12 months, and only two did so at 24 months. The small number of women who had 24 months of follow-up limits the strength of the conclusion.

How this study compares with other investigations

As Kaunitz and colleagues note in their meta-analysis, studies comparing the LNG-IUS with endometrial ablation have produced conflicting findings about the reduction of menstrual blood loss: Some have found the modalities to be equally effective, others have found the LNG-IUS to be more effective, and still others have demonstrated higher efficacy for endometrial ablation. A recent Cochrane review reported that the LNG-IUS produced smaller mean reductions in menstrual blood loss than endometrial ablation did.2

When quality of life is the main consideration, data point to equivalence of options

The reduction of menstrual blood loss is only one area of focus in the treatment of menorrhagia, part of the larger goal of improving quality of life. Two Cochrane reviews concluded there is no difference between the LNG-IUS and endometrial ablation in regard to satisfaction rates or quality of life.2,3 Five studies reported quality of life scores; all five found them to be equivalent between modalities.

Although the data presented in this study are not definitive, the findings do support the growing body of data suggesting that these two treatments are, in some respects, equivalent options. At the same time, they are different procedures with distinct risks and considerations. When deciding between them, a patient’s desire for fertility may tip the scales in favor of the LNG-IUS.—MATTHEW R. HOPKINS, MD

1. Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, Olkin I, Rennie D, Stroup DF. Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. Quality of Reporting of Meta-analyses. Lancet. 1999;354:1896-1900.

2. Lethaby AE, Cooke I, Rees M. Progesterone on progestogen-releasing intrauterine systems for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(4):CD002126.-

3. Marjoribanks J, Lethaby A, Farquhar C. Surgery versus medical therapy for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(2):CD003855.-

Historically, hysterectomy was the only alternative to medical treatment. However, endometrial ablation and the LNG-IUS have both proved to be effective, and less invasive, therapies.

Until recently, the average ObGyn in the United States placed only about four intrauterine devices (IUDs) a year. This low volume made many practitioners reluctant to prescribe the IUD, but we are seeing a resurgence in use.

Details of the study

This analysis, which meets Quality of Reporting of Meta-analyses (QUOROM) guidelines, was restricted to studies that included pre- and posttreatment assessment of menstrual blood loss using the Pictorial Blood Loss Assessment Chart (PBLAC).1 Although the PBLAC has limitations, it is one of the more practical, objective measures available. The PBLAC score does not yield an exact measure of blood loss, but it has been found to correlate well with menstrual blood volume. When it is used to evaluate menstrual blood loss of 80 mL or more, its specificity and sensitivity exceed 80%.

In reviewing randomized, controlled trials for this study, the authors found only a small number (n=6) that met their criteria, and those studies involved a relatively small number of patients (LNG-IUS, n=196; endometrial ablation, n=194), limiting the statistical power of this investigation.

Both treatment modalities were associated with a reduction in menstrual blood loss, and the degree of the reduction was similar between modalities at 6, 12, and 24 months.

The treatment failure rate was not time-adjusted; nor was the study powered to address the question of failure.

Only two studies assessed the PBLAC score at 6 months, five did so at 12 months, and only two did so at 24 months. The small number of women who had 24 months of follow-up limits the strength of the conclusion.

How this study compares with other investigations

As Kaunitz and colleagues note in their meta-analysis, studies comparing the LNG-IUS with endometrial ablation have produced conflicting findings about the reduction of menstrual blood loss: Some have found the modalities to be equally effective, others have found the LNG-IUS to be more effective, and still others have demonstrated higher efficacy for endometrial ablation. A recent Cochrane review reported that the LNG-IUS produced smaller mean reductions in menstrual blood loss than endometrial ablation did.2

When quality of life is the main consideration, data point to equivalence of options

The reduction of menstrual blood loss is only one area of focus in the treatment of menorrhagia, part of the larger goal of improving quality of life. Two Cochrane reviews concluded there is no difference between the LNG-IUS and endometrial ablation in regard to satisfaction rates or quality of life.2,3 Five studies reported quality of life scores; all five found them to be equivalent between modalities.

Although the data presented in this study are not definitive, the findings do support the growing body of data suggesting that these two treatments are, in some respects, equivalent options. At the same time, they are different procedures with distinct risks and considerations. When deciding between them, a patient’s desire for fertility may tip the scales in favor of the LNG-IUS.—MATTHEW R. HOPKINS, MD

Historically, hysterectomy was the only alternative to medical treatment. However, endometrial ablation and the LNG-IUS have both proved to be effective, and less invasive, therapies.

Until recently, the average ObGyn in the United States placed only about four intrauterine devices (IUDs) a year. This low volume made many practitioners reluctant to prescribe the IUD, but we are seeing a resurgence in use.

Details of the study

This analysis, which meets Quality of Reporting of Meta-analyses (QUOROM) guidelines, was restricted to studies that included pre- and posttreatment assessment of menstrual blood loss using the Pictorial Blood Loss Assessment Chart (PBLAC).1 Although the PBLAC has limitations, it is one of the more practical, objective measures available. The PBLAC score does not yield an exact measure of blood loss, but it has been found to correlate well with menstrual blood volume. When it is used to evaluate menstrual blood loss of 80 mL or more, its specificity and sensitivity exceed 80%.

In reviewing randomized, controlled trials for this study, the authors found only a small number (n=6) that met their criteria, and those studies involved a relatively small number of patients (LNG-IUS, n=196; endometrial ablation, n=194), limiting the statistical power of this investigation.

Both treatment modalities were associated with a reduction in menstrual blood loss, and the degree of the reduction was similar between modalities at 6, 12, and 24 months.

The treatment failure rate was not time-adjusted; nor was the study powered to address the question of failure.

Only two studies assessed the PBLAC score at 6 months, five did so at 12 months, and only two did so at 24 months. The small number of women who had 24 months of follow-up limits the strength of the conclusion.

How this study compares with other investigations

As Kaunitz and colleagues note in their meta-analysis, studies comparing the LNG-IUS with endometrial ablation have produced conflicting findings about the reduction of menstrual blood loss: Some have found the modalities to be equally effective, others have found the LNG-IUS to be more effective, and still others have demonstrated higher efficacy for endometrial ablation. A recent Cochrane review reported that the LNG-IUS produced smaller mean reductions in menstrual blood loss than endometrial ablation did.2

When quality of life is the main consideration, data point to equivalence of options

The reduction of menstrual blood loss is only one area of focus in the treatment of menorrhagia, part of the larger goal of improving quality of life. Two Cochrane reviews concluded there is no difference between the LNG-IUS and endometrial ablation in regard to satisfaction rates or quality of life.2,3 Five studies reported quality of life scores; all five found them to be equivalent between modalities.

Although the data presented in this study are not definitive, the findings do support the growing body of data suggesting that these two treatments are, in some respects, equivalent options. At the same time, they are different procedures with distinct risks and considerations. When deciding between them, a patient’s desire for fertility may tip the scales in favor of the LNG-IUS.—MATTHEW R. HOPKINS, MD

1. Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, Olkin I, Rennie D, Stroup DF. Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. Quality of Reporting of Meta-analyses. Lancet. 1999;354:1896-1900.

2. Lethaby AE, Cooke I, Rees M. Progesterone on progestogen-releasing intrauterine systems for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(4):CD002126.-

3. Marjoribanks J, Lethaby A, Farquhar C. Surgery versus medical therapy for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(2):CD003855.-

1. Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, Olkin I, Rennie D, Stroup DF. Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. Quality of Reporting of Meta-analyses. Lancet. 1999;354:1896-1900.

2. Lethaby AE, Cooke I, Rees M. Progesterone on progestogen-releasing intrauterine systems for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(4):CD002126.-

3. Marjoribanks J, Lethaby A, Farquhar C. Surgery versus medical therapy for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(2):CD003855.-