User login

Antipsychotic-induced priapism: Mitigating the risk

Mr. J, age 35, is brought to the hospital from prison due to priapism that does not improve with treatment. He says he has had priapism 5 times previously, with the first incidence occurring “years ago” due to trazodone.

Recently, he has been receiving risperidone, which the treatment team believes is the cause of his current priapism. His medical history includes asthma, schizophrenia, hypertension, seizures, and sickle cell trait. Mr. J is experiencing auditory hallucinations, which he describes as “continuous, neutral voices that are annoying.” He would like relief from his auditory hallucinations and is willing to change his antipsychotic, but does not want additional treatment for his priapism. His present medications include risperidone, 1 mg twice a day, escitalopram, 10 mg/d, benztropine, 1 mg twice a day, and phenytoin, 500 mg/d at bedtime.

Priapism is a prolonged, persistent, and often painful erection that occurs without sexual stimulation. Although relatively rare, it can result in potentially serious long-term complications, including impotence and gangrene, and requires immediate evaluation and management.

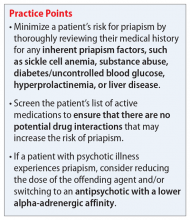

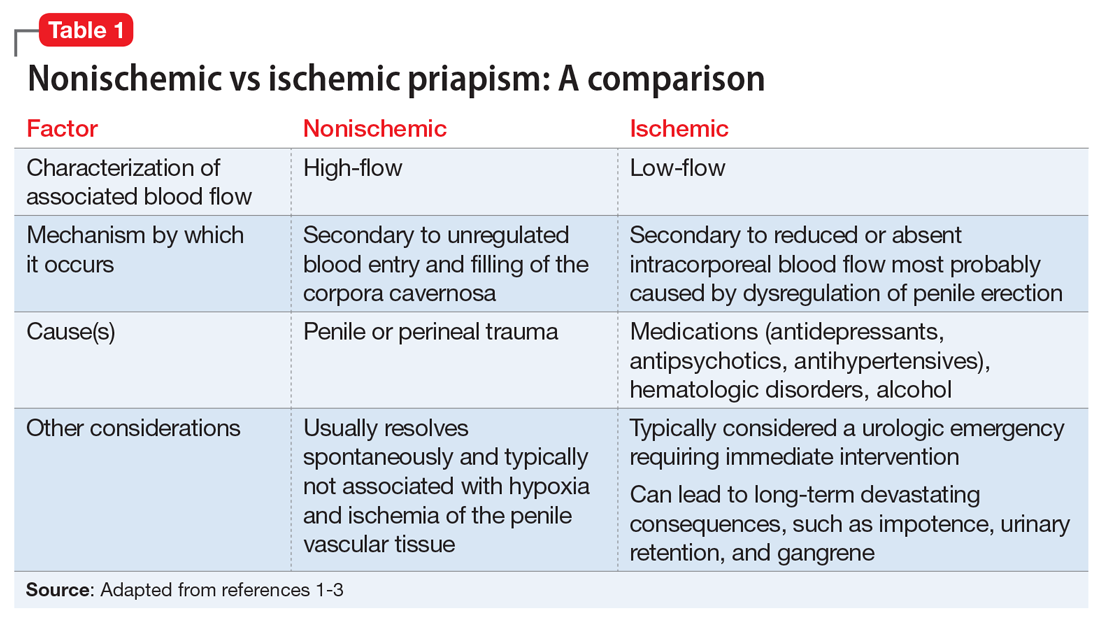

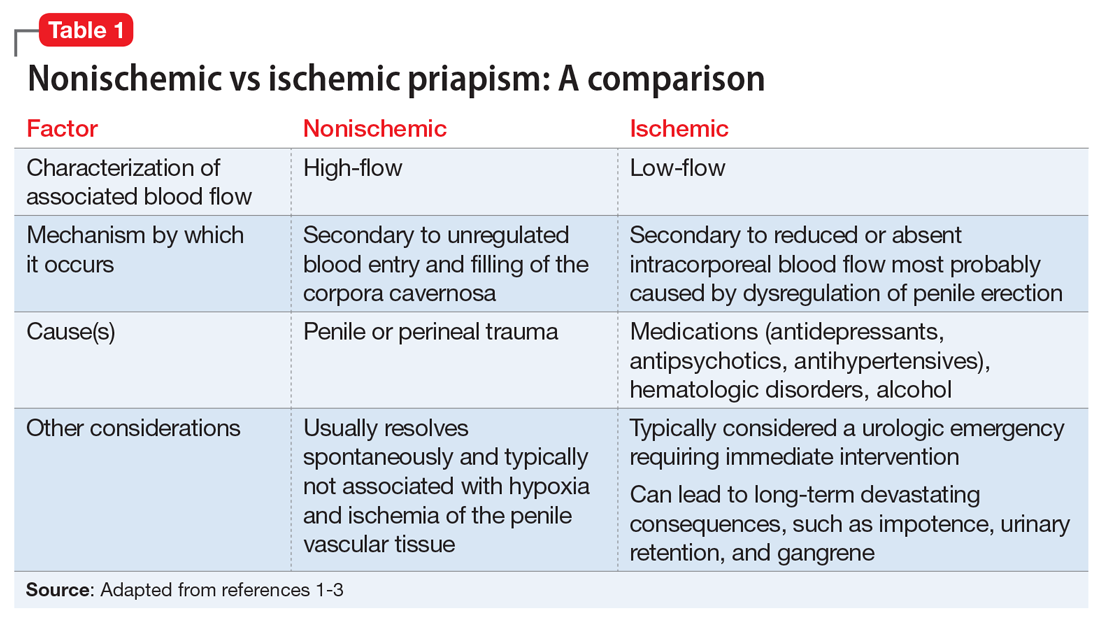

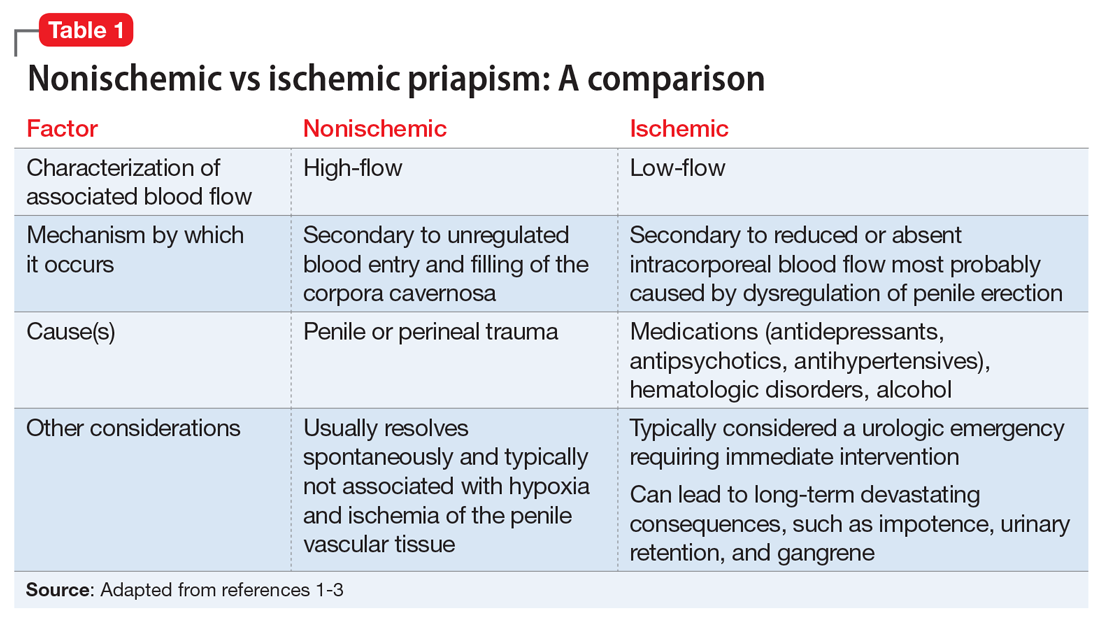

There are 2 types of priapism: nonischemic, or “high-flow,” priapism, and ischemic, or “low-flow,” priapism (Table 1). While nonischemic priapism is typically caused by penile or perineal trauma, ischemic priapism can occur as a result of medications, including antipsychotics, antidepressants, anxiolytics, and antihypertensives, or hematological conditions such as sickle cell disease.1 Other risk factors associated with priapism include substance abuse, hyperprolactinemia, diabetes, and liver disease.4

Antipsychotic-induced priapism

Medication-induced priapism is a rare adverse drug reaction (ADR). Of the medication classes associated with priapism, antipsychotics have the highest incidence and account for approximately 20% of all cases.1

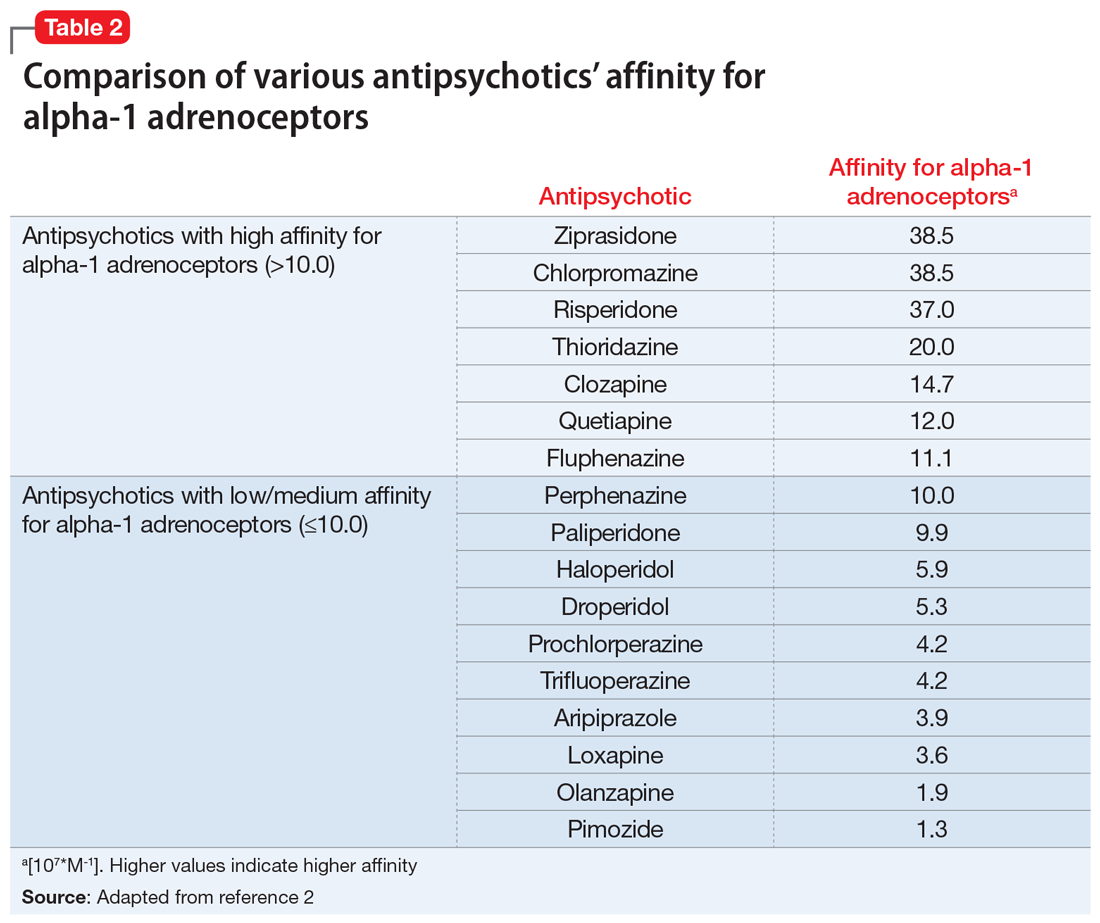

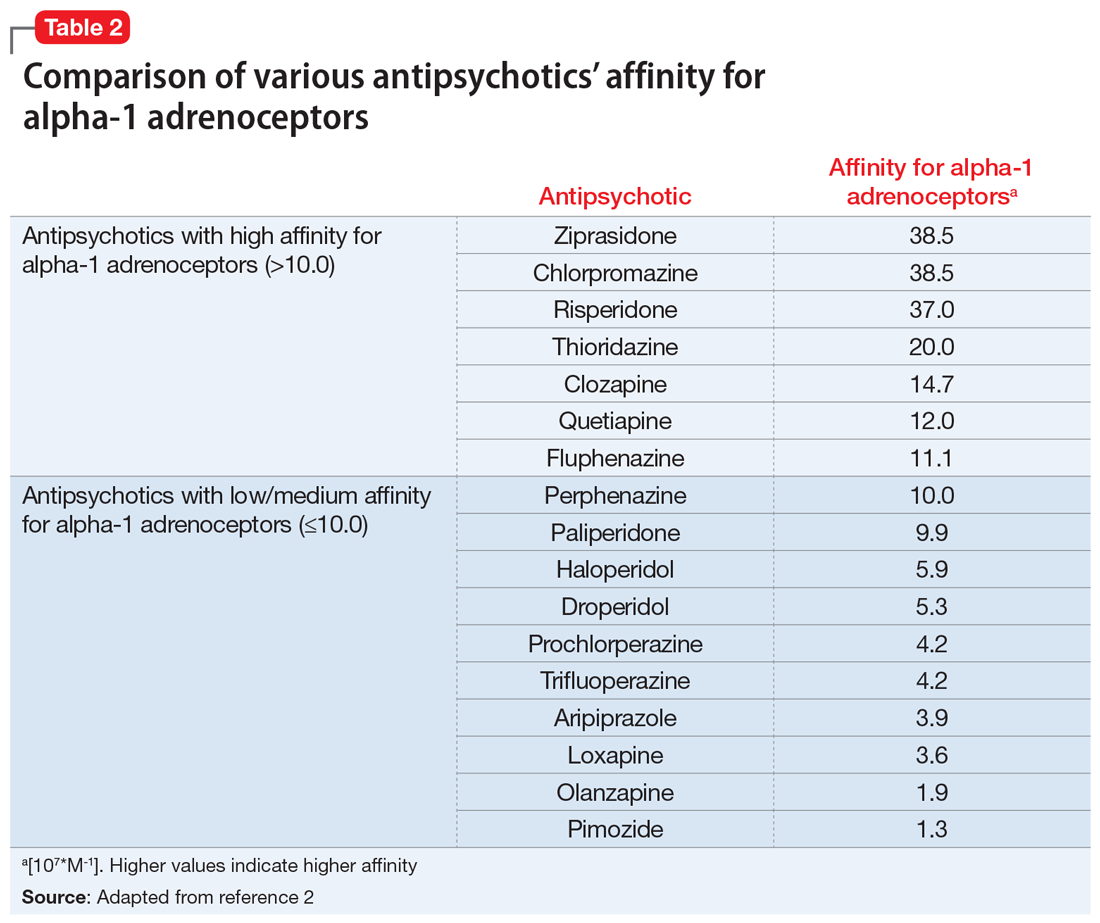

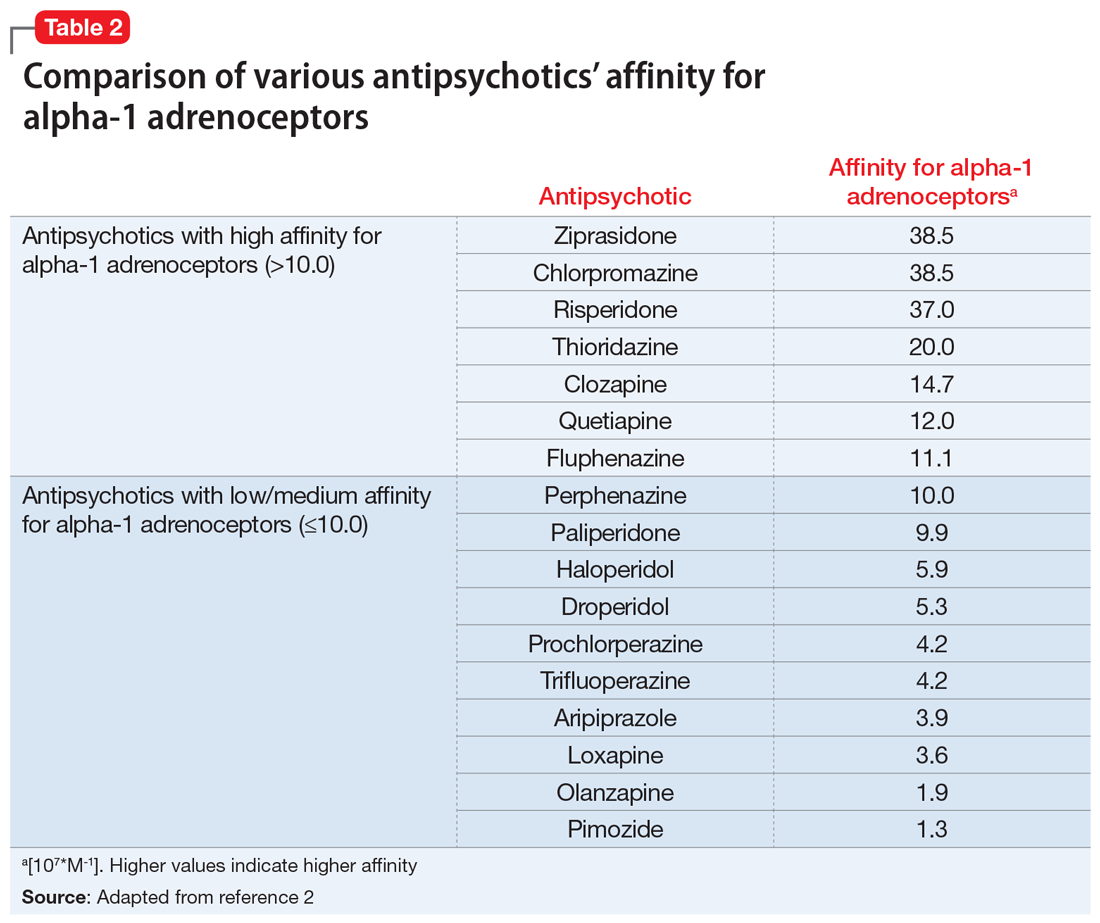

The mechanism of priapism associated with antipsychotics is thought to be related to alpha-1 blockade in the corpora cavernosa of the penis. Although antipsychotics within each class share common characteristics, each agent has a unique profile of receptor affinities. As such, antipsychotics have varying affinities for the alpha-adrenergic receptor (Table 2). Agents such as ziprasidone, chlorpromazine, and risperidone—which have the highest affinity for the alpha-1 adrenoceptors—may be more likely to cause priapism compared with agents with lower affinity, such as olanzapine. Priapism may occur at any time during antipsychotic treatment, and does not appear to be dose-related.

Continue to: Antipsychotic drug interactions and priapism...

Antipsychotic drug interactions and priapism

Patients who are receiving multiple medications as treatment for chronic medical or psychiatric conditions have an increased likelihood of experiencing drug-drug interactions (DDIs) that lead to adverse effects.

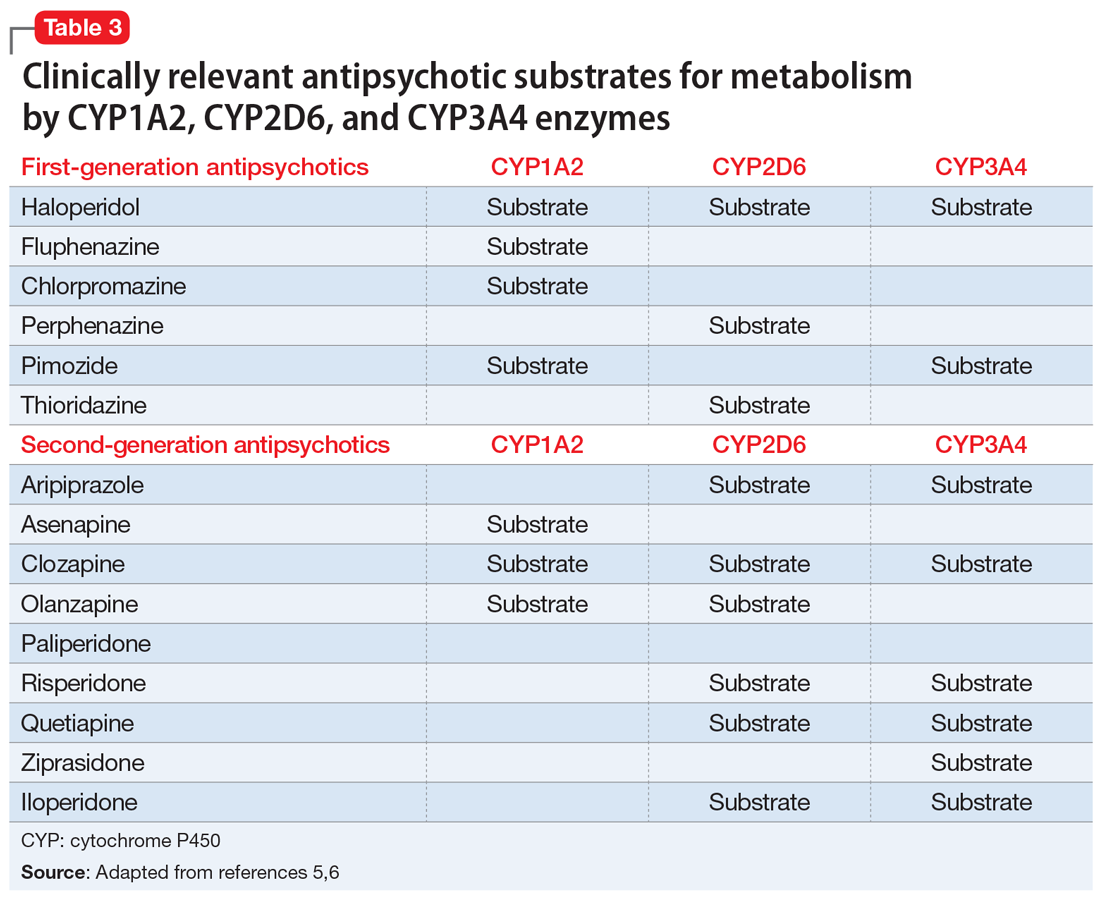

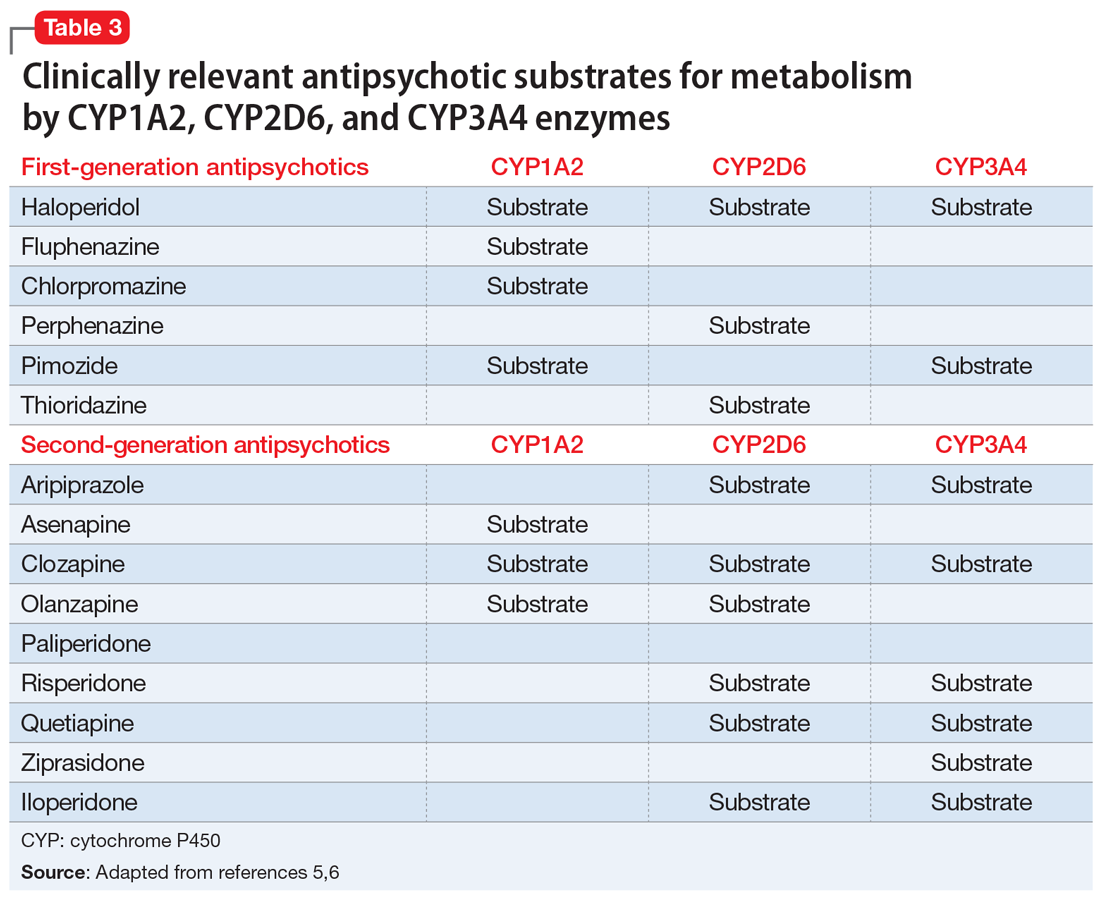

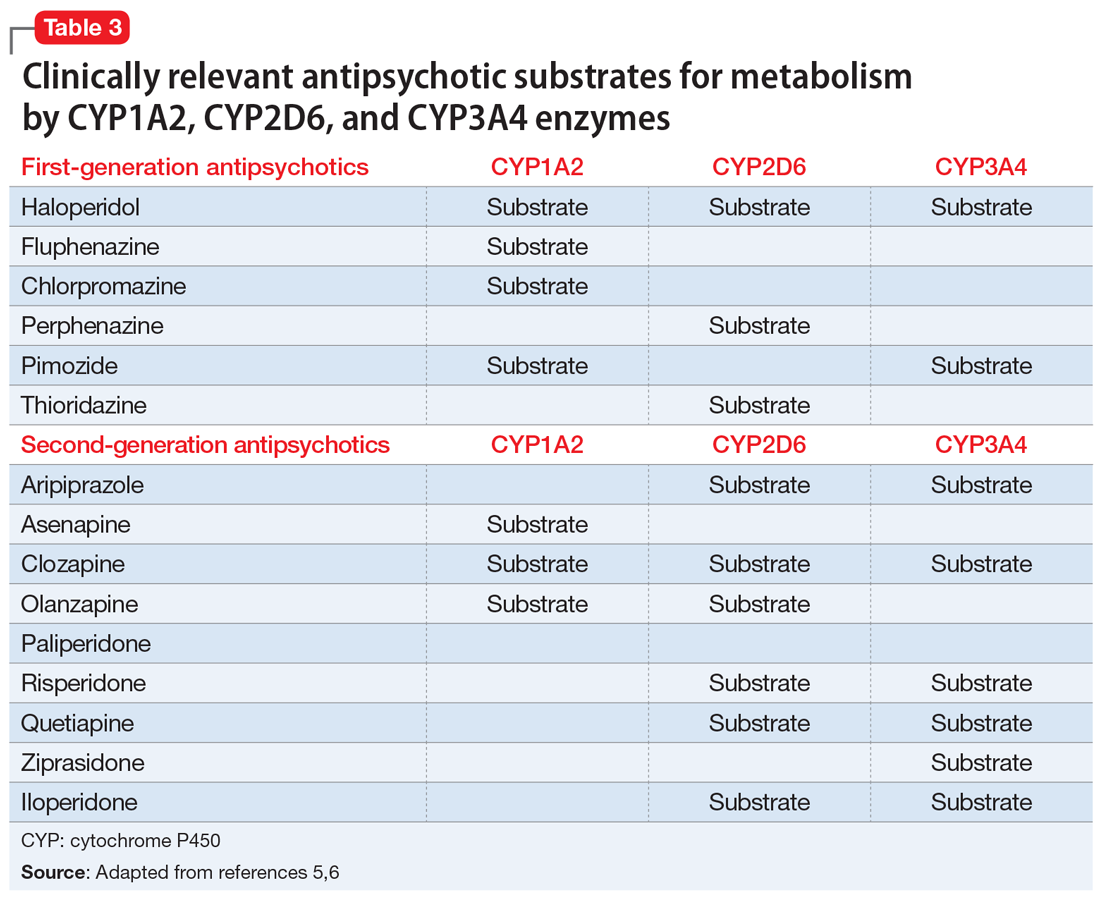

Various case reports have described priapism as a result of DDIs related to antipsychotic agents combined with other psychotropic or nonpsychotropic medications.3 Most of these DDIs have been attributed to the cytochrome P450 (CYP) family of enzymes, including CYP2D6, CYP1A2, and CYP3A4/5, which are major enzymes implicated in the metabolism of antipsychotics (Table 3).

It is imperative to be vigilant during the concomitant administration of antipsychotics with other medications that may be substrates, inducers, or inhibitors of CYP enzymes, as this could alter the metabolism and kinetics of the antipsychotic and result in ADRs such as priapism. For example, drug interactions exist between strong CYP2D6 inhibitors—such as the antidepressants paroxetine, fluoxetine, and bupropion—and antipsychotics that are substrates of CYP2D6, such as risperidone, aripiprazole, haloperidol, and perphenazine. This interaction can lead to higher levels of the antipsychotic, which would increase the patient’s risk of experiencing ADRs. Because psychotic illnesses and depression/anxiety often coexist, it is not uncommon for individuals with these conditions to be receiving both an antipsychotic and an antidepressant.

Because there is a high incidence of comorbidities such as HIV and cardiovascular disease among individuals with mental illnesses, clinicians must also be cognizant of any nonpsychotropic medications the patient may be taking. For instance, clinically relevant DDIs exist between protease inhibitors, such as ritonavir, a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor, and antipsychotics that are substrates of CYP3A4, such as pimozide, aripiprazole, and quetiapine.

Mitigating the risk of priapism

Although there are associated risk factors for priapism, there are no concrete indicators to predict the onset or development of the condition. The best predictor may be a history of prolonged and painless erections.3

As such, when choosing an antipsychotic, it is critical to screen the patient for the previously mentioned risk factors, including the presence of medications with strong alpha-1 receptor affinity and CYP interactions, especially to minimize the risk of recurrence of priapism in those with prior or similar episodes. Management of patients with priapism due to antipsychotics has involved reducing the dose of the offending agent and/or changing the medication to one with a lower alpha-adrenergic affinity (Table 22).

Similar to most situations, management is patient-specific and depends on several factors, including the severity of the patient’s psychiatric disease, history/severity of priapism and treatment, concurrent medication list, etc. For example, although clozapine is considered to have relatively high affinity for the alpha-1 receptor, it is also the agent of choice for treatment-refractory schizophrenia. Risks and benefits must be weighed on a individualized basis. Case reports have described symptom improvement via lowering the dose of clozapine and adding on or switching to an antipsychotic agent with minimal alpha-1 receptor affinity.4

After considering Mr. J’s history, risk factors, and preferences, the treatment team discontinues risperidone and initiates haloperidol, 5 mg twice a day. Soon after, Mr. J no longer experiences priapism.

1. Weiner DM, Lowe FC. Psychotropic drug-induced priapism. Mol Diag Ther 9. 1998;371-379. doi:10.2165/00023210-199809050-00004

2. Andersohn F, Schmedt N, Weinmann S, et al. Priapism associated with antipsychotics: role of alpha1 adrenoceptor affinity. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30(1):68-71. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181c8273d

3. Sood S, James W, Bailon MJ. Priapism associated with atypical antipsychotic medications: a review. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(1):9-17.

4. Sinkeviciute I, Kroken RA, Johnsen E. Priapism in antipsychotic drug use: a rare but important side effect. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2012;2012:496364. doi:10.1155/2012/496364

5. Mora F, Martín JDD, Zubillaga E, et al. CYP450 and its implications in the clinical use of antipsychotic drugs. Clin Exp Pharmacol. 2015;5(176):1-10. doi:10.4172/2161-1459.1000176

6. Puangpetch A, Vanwong N, Nuntamool N, et al. CYP2D6 polymorphisms and their influence on risperidone treatment. Pharmgenomics Pers Med. 2016;9:131-147. doi:10.2147/PGPM.S107772

Mr. J, age 35, is brought to the hospital from prison due to priapism that does not improve with treatment. He says he has had priapism 5 times previously, with the first incidence occurring “years ago” due to trazodone.

Recently, he has been receiving risperidone, which the treatment team believes is the cause of his current priapism. His medical history includes asthma, schizophrenia, hypertension, seizures, and sickle cell trait. Mr. J is experiencing auditory hallucinations, which he describes as “continuous, neutral voices that are annoying.” He would like relief from his auditory hallucinations and is willing to change his antipsychotic, but does not want additional treatment for his priapism. His present medications include risperidone, 1 mg twice a day, escitalopram, 10 mg/d, benztropine, 1 mg twice a day, and phenytoin, 500 mg/d at bedtime.

Priapism is a prolonged, persistent, and often painful erection that occurs without sexual stimulation. Although relatively rare, it can result in potentially serious long-term complications, including impotence and gangrene, and requires immediate evaluation and management.

There are 2 types of priapism: nonischemic, or “high-flow,” priapism, and ischemic, or “low-flow,” priapism (Table 1). While nonischemic priapism is typically caused by penile or perineal trauma, ischemic priapism can occur as a result of medications, including antipsychotics, antidepressants, anxiolytics, and antihypertensives, or hematological conditions such as sickle cell disease.1 Other risk factors associated with priapism include substance abuse, hyperprolactinemia, diabetes, and liver disease.4

Antipsychotic-induced priapism

Medication-induced priapism is a rare adverse drug reaction (ADR). Of the medication classes associated with priapism, antipsychotics have the highest incidence and account for approximately 20% of all cases.1

The mechanism of priapism associated with antipsychotics is thought to be related to alpha-1 blockade in the corpora cavernosa of the penis. Although antipsychotics within each class share common characteristics, each agent has a unique profile of receptor affinities. As such, antipsychotics have varying affinities for the alpha-adrenergic receptor (Table 2). Agents such as ziprasidone, chlorpromazine, and risperidone—which have the highest affinity for the alpha-1 adrenoceptors—may be more likely to cause priapism compared with agents with lower affinity, such as olanzapine. Priapism may occur at any time during antipsychotic treatment, and does not appear to be dose-related.

Continue to: Antipsychotic drug interactions and priapism...

Antipsychotic drug interactions and priapism

Patients who are receiving multiple medications as treatment for chronic medical or psychiatric conditions have an increased likelihood of experiencing drug-drug interactions (DDIs) that lead to adverse effects.

Various case reports have described priapism as a result of DDIs related to antipsychotic agents combined with other psychotropic or nonpsychotropic medications.3 Most of these DDIs have been attributed to the cytochrome P450 (CYP) family of enzymes, including CYP2D6, CYP1A2, and CYP3A4/5, which are major enzymes implicated in the metabolism of antipsychotics (Table 3).

It is imperative to be vigilant during the concomitant administration of antipsychotics with other medications that may be substrates, inducers, or inhibitors of CYP enzymes, as this could alter the metabolism and kinetics of the antipsychotic and result in ADRs such as priapism. For example, drug interactions exist between strong CYP2D6 inhibitors—such as the antidepressants paroxetine, fluoxetine, and bupropion—and antipsychotics that are substrates of CYP2D6, such as risperidone, aripiprazole, haloperidol, and perphenazine. This interaction can lead to higher levels of the antipsychotic, which would increase the patient’s risk of experiencing ADRs. Because psychotic illnesses and depression/anxiety often coexist, it is not uncommon for individuals with these conditions to be receiving both an antipsychotic and an antidepressant.

Because there is a high incidence of comorbidities such as HIV and cardiovascular disease among individuals with mental illnesses, clinicians must also be cognizant of any nonpsychotropic medications the patient may be taking. For instance, clinically relevant DDIs exist between protease inhibitors, such as ritonavir, a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor, and antipsychotics that are substrates of CYP3A4, such as pimozide, aripiprazole, and quetiapine.

Mitigating the risk of priapism

Although there are associated risk factors for priapism, there are no concrete indicators to predict the onset or development of the condition. The best predictor may be a history of prolonged and painless erections.3

As such, when choosing an antipsychotic, it is critical to screen the patient for the previously mentioned risk factors, including the presence of medications with strong alpha-1 receptor affinity and CYP interactions, especially to minimize the risk of recurrence of priapism in those with prior or similar episodes. Management of patients with priapism due to antipsychotics has involved reducing the dose of the offending agent and/or changing the medication to one with a lower alpha-adrenergic affinity (Table 22).

Similar to most situations, management is patient-specific and depends on several factors, including the severity of the patient’s psychiatric disease, history/severity of priapism and treatment, concurrent medication list, etc. For example, although clozapine is considered to have relatively high affinity for the alpha-1 receptor, it is also the agent of choice for treatment-refractory schizophrenia. Risks and benefits must be weighed on a individualized basis. Case reports have described symptom improvement via lowering the dose of clozapine and adding on or switching to an antipsychotic agent with minimal alpha-1 receptor affinity.4

After considering Mr. J’s history, risk factors, and preferences, the treatment team discontinues risperidone and initiates haloperidol, 5 mg twice a day. Soon after, Mr. J no longer experiences priapism.

Mr. J, age 35, is brought to the hospital from prison due to priapism that does not improve with treatment. He says he has had priapism 5 times previously, with the first incidence occurring “years ago” due to trazodone.

Recently, he has been receiving risperidone, which the treatment team believes is the cause of his current priapism. His medical history includes asthma, schizophrenia, hypertension, seizures, and sickle cell trait. Mr. J is experiencing auditory hallucinations, which he describes as “continuous, neutral voices that are annoying.” He would like relief from his auditory hallucinations and is willing to change his antipsychotic, but does not want additional treatment for his priapism. His present medications include risperidone, 1 mg twice a day, escitalopram, 10 mg/d, benztropine, 1 mg twice a day, and phenytoin, 500 mg/d at bedtime.

Priapism is a prolonged, persistent, and often painful erection that occurs without sexual stimulation. Although relatively rare, it can result in potentially serious long-term complications, including impotence and gangrene, and requires immediate evaluation and management.

There are 2 types of priapism: nonischemic, or “high-flow,” priapism, and ischemic, or “low-flow,” priapism (Table 1). While nonischemic priapism is typically caused by penile or perineal trauma, ischemic priapism can occur as a result of medications, including antipsychotics, antidepressants, anxiolytics, and antihypertensives, or hematological conditions such as sickle cell disease.1 Other risk factors associated with priapism include substance abuse, hyperprolactinemia, diabetes, and liver disease.4

Antipsychotic-induced priapism

Medication-induced priapism is a rare adverse drug reaction (ADR). Of the medication classes associated with priapism, antipsychotics have the highest incidence and account for approximately 20% of all cases.1

The mechanism of priapism associated with antipsychotics is thought to be related to alpha-1 blockade in the corpora cavernosa of the penis. Although antipsychotics within each class share common characteristics, each agent has a unique profile of receptor affinities. As such, antipsychotics have varying affinities for the alpha-adrenergic receptor (Table 2). Agents such as ziprasidone, chlorpromazine, and risperidone—which have the highest affinity for the alpha-1 adrenoceptors—may be more likely to cause priapism compared with agents with lower affinity, such as olanzapine. Priapism may occur at any time during antipsychotic treatment, and does not appear to be dose-related.

Continue to: Antipsychotic drug interactions and priapism...

Antipsychotic drug interactions and priapism

Patients who are receiving multiple medications as treatment for chronic medical or psychiatric conditions have an increased likelihood of experiencing drug-drug interactions (DDIs) that lead to adverse effects.

Various case reports have described priapism as a result of DDIs related to antipsychotic agents combined with other psychotropic or nonpsychotropic medications.3 Most of these DDIs have been attributed to the cytochrome P450 (CYP) family of enzymes, including CYP2D6, CYP1A2, and CYP3A4/5, which are major enzymes implicated in the metabolism of antipsychotics (Table 3).

It is imperative to be vigilant during the concomitant administration of antipsychotics with other medications that may be substrates, inducers, or inhibitors of CYP enzymes, as this could alter the metabolism and kinetics of the antipsychotic and result in ADRs such as priapism. For example, drug interactions exist between strong CYP2D6 inhibitors—such as the antidepressants paroxetine, fluoxetine, and bupropion—and antipsychotics that are substrates of CYP2D6, such as risperidone, aripiprazole, haloperidol, and perphenazine. This interaction can lead to higher levels of the antipsychotic, which would increase the patient’s risk of experiencing ADRs. Because psychotic illnesses and depression/anxiety often coexist, it is not uncommon for individuals with these conditions to be receiving both an antipsychotic and an antidepressant.

Because there is a high incidence of comorbidities such as HIV and cardiovascular disease among individuals with mental illnesses, clinicians must also be cognizant of any nonpsychotropic medications the patient may be taking. For instance, clinically relevant DDIs exist between protease inhibitors, such as ritonavir, a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor, and antipsychotics that are substrates of CYP3A4, such as pimozide, aripiprazole, and quetiapine.

Mitigating the risk of priapism

Although there are associated risk factors for priapism, there are no concrete indicators to predict the onset or development of the condition. The best predictor may be a history of prolonged and painless erections.3

As such, when choosing an antipsychotic, it is critical to screen the patient for the previously mentioned risk factors, including the presence of medications with strong alpha-1 receptor affinity and CYP interactions, especially to minimize the risk of recurrence of priapism in those with prior or similar episodes. Management of patients with priapism due to antipsychotics has involved reducing the dose of the offending agent and/or changing the medication to one with a lower alpha-adrenergic affinity (Table 22).

Similar to most situations, management is patient-specific and depends on several factors, including the severity of the patient’s psychiatric disease, history/severity of priapism and treatment, concurrent medication list, etc. For example, although clozapine is considered to have relatively high affinity for the alpha-1 receptor, it is also the agent of choice for treatment-refractory schizophrenia. Risks and benefits must be weighed on a individualized basis. Case reports have described symptom improvement via lowering the dose of clozapine and adding on or switching to an antipsychotic agent with minimal alpha-1 receptor affinity.4

After considering Mr. J’s history, risk factors, and preferences, the treatment team discontinues risperidone and initiates haloperidol, 5 mg twice a day. Soon after, Mr. J no longer experiences priapism.

1. Weiner DM, Lowe FC. Psychotropic drug-induced priapism. Mol Diag Ther 9. 1998;371-379. doi:10.2165/00023210-199809050-00004

2. Andersohn F, Schmedt N, Weinmann S, et al. Priapism associated with antipsychotics: role of alpha1 adrenoceptor affinity. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30(1):68-71. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181c8273d

3. Sood S, James W, Bailon MJ. Priapism associated with atypical antipsychotic medications: a review. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(1):9-17.

4. Sinkeviciute I, Kroken RA, Johnsen E. Priapism in antipsychotic drug use: a rare but important side effect. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2012;2012:496364. doi:10.1155/2012/496364

5. Mora F, Martín JDD, Zubillaga E, et al. CYP450 and its implications in the clinical use of antipsychotic drugs. Clin Exp Pharmacol. 2015;5(176):1-10. doi:10.4172/2161-1459.1000176

6. Puangpetch A, Vanwong N, Nuntamool N, et al. CYP2D6 polymorphisms and their influence on risperidone treatment. Pharmgenomics Pers Med. 2016;9:131-147. doi:10.2147/PGPM.S107772

1. Weiner DM, Lowe FC. Psychotropic drug-induced priapism. Mol Diag Ther 9. 1998;371-379. doi:10.2165/00023210-199809050-00004

2. Andersohn F, Schmedt N, Weinmann S, et al. Priapism associated with antipsychotics: role of alpha1 adrenoceptor affinity. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30(1):68-71. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181c8273d

3. Sood S, James W, Bailon MJ. Priapism associated with atypical antipsychotic medications: a review. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(1):9-17.

4. Sinkeviciute I, Kroken RA, Johnsen E. Priapism in antipsychotic drug use: a rare but important side effect. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2012;2012:496364. doi:10.1155/2012/496364

5. Mora F, Martín JDD, Zubillaga E, et al. CYP450 and its implications in the clinical use of antipsychotic drugs. Clin Exp Pharmacol. 2015;5(176):1-10. doi:10.4172/2161-1459.1000176

6. Puangpetch A, Vanwong N, Nuntamool N, et al. CYP2D6 polymorphisms and their influence on risperidone treatment. Pharmgenomics Pers Med. 2016;9:131-147. doi:10.2147/PGPM.S107772