User login

Cost-conscious choices for minimally invasive gynecologic surgery

CASE: COST-CONSCIOUS LAPAROSCOPIC HYSTERECTOMY

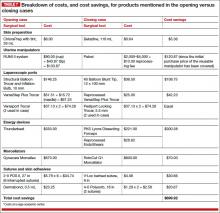

A 43-year-old woman undergoes laparoscopic hysterectomy for treatment of uterine fibroids and menorrhagia. Once she is prepped with ChloraPrep, a RUMI II uterine manipulator is placed. Laparoscopic ports include a Structural Balloon Trocar, a VersaStep Plus trocar, and two Versaport trocars. The surgeon uses an Olympus Thunderbeat device—a combination of ultrasonic and bipolar energy—to perform the majority of the procedure. The uterus is morcellated using the disposable Gynecare Morcellex, and the vaginal cuff is closed using a series of 2-0 PDS II sutures. The skin incisions are closed using Dermabond skin adhesive.

The total cost of the products used in this case: $1,705.60.

Could different product choices have reduced this figure?

As health-care costs continue to rise faster than inflation, with total health-care expenditures accounting for about 18% of the US gross domestic product, we face increasing pressure to take cost into account in the management of our patients.1 Not surprisingly, cost-effectiveness and outcome quality have become measures in many clinical trials that compare standard and alternative therapies. The field of women’s health—and, specifically, minimally invasive gynecologic surgery—is not immune to such comparisons.

Overall, conventional laparoscopic gynecologic procedures tend to have lower costs than laparotomy, due to shorter hospital stays, faster recovery, and fewer complications.2–4 What is not fully appreciated is how the choice of laparoscopic instrumentation and associated products affects surgical costs. In this article, we review these costs with the goal of raising awareness among minimally invasive gynecologic surgeons.

In the sections that follow, we highlight several aspects of laparoscopic gynecologic surgery that may affect your selection of instruments and products, describing the difference in cost as well as some unique characteristics of the products. Please note that our comparison focuses solely on cost, not ease of utility, effectiveness, surgical technique, risk of complications, or any other assessment. We’d also like to point out that numerous other instruments and devices are commercially available besides those listed in this article.

A few variables to keep in mind

Even when taking cost into consideration, tailor the selection of instruments and supplies to your capabilities and comfort, as well as characteristics particular to the patient and the planned procedure. Also keep in mind that your institution may have arrangements with companies that supply minimally invasive instruments, and such arrangements may limit your options to some degree. Be aware that reprocessed ports and instruments are now available at a reduced cost.

We believe it is crucial for surgeons to be cognizant of all products potentially available to them prior to attending a surgical case.

Related article: Update on Technology Barbara S. Levy, MD (September 2013)

Skin preparation and other preoperative considerations

Multiple preoperative skin preparations are available (TABLE 1). Traditionally, a povidone-iodine topical antiseptic such as Betadine has been used for skin and vaginal preparation prior to gynecologic surgery. Hibaclens and ChloraPrep are different combinations of chlorhexidine gluconate and isopropyl alcohol that act as broad-spectrum antiseptics. ChloraPrep is applied with a wand-like applicator and contains a much higher concentration of isopropyl alcohol than Hibaclens (70% vs 4%), rendering it more flammable. It also requires more drying time before the case is started. Clear and tinted ChloraPrep formulations are available.

It makes good sense to have instruments and devices readily available in the operating room (OR) at the start of a case, to avoid unnecessary surgical delays, but we recommend that you refrain from opening these tools until they are required intraoperatively. It is possible that the case will require conversion to laparotomy or that, after direct visualization of the pathology, different ports or instruments will be required.

Uterine manipulators

Cannulation of the cervical canal allows for uterine manipulation, increasing intraoperative traction and exposure and visualization of the adnexae and peritoneal surfaces.

The Hulka and Pelosi reusable uterine manipulators are fairly standard and easy to apply. Specialized, single-use manipulators also are available, including the VCare uterine manipulator/elevator, which consists of two opposing cups. One cup (available in four sizes, from small to extra-large) fits around the cervix and defines the site for colpotomy, and the other cup helps maintain pneumoperitoneum once a colpotomy is created.

The Zinnanti Uterine Manipulator Injector (ZUMI) is a rigid, curved shaft with an intrauterine balloon to help prevent expulsion. It also has an integrated injection channel to allow for intraoperative chromotubation.

The RUMI System fits individual patient anatomy with various tip lengths and colpotomy cup sizes (TABLE 2).

Related article: Tips and techniques for robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy Arnold P. Advincula, MD, and Bich-Van Tran, MD (August 2013)

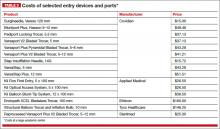

Entry style and ports

The peritoneal cavity can be entered using either a closed (Veress needle) or open (Hasson) technique.5 Closed entry may allow for quicker access to the peritoneal cavity. A recent Cochrane review of 28 randomized, controlled trials, including 4,860 patients undergoing laparoscopy, compared outcomes between laparoscopic entry techniques.6 It found no difference in major vascular or visceral injury between closed and open techniques at the umbilicus. However, open entry was associated with greater successful entry into the peritoneal cavity, as well as less extraperitoneal insufflation and a lower omental injury rate, compared with closed entry.6

Left-upper-quadrant entry is another option when adhesions are anticipated or abnormal anatomy is encountered at the umbilicus.

In general, complications related to laparoscopic entry are quite rare in gynecologic surgery, ranging from 0.18% to 0.5%.7,8 A minimally invasive surgeon may prefer one entry technique over the other, but should be able to perform both methods competently and recognize when a particular technique is warranted.

Choosing a port

Laparoscopic ports usually range from 5 mm to 12 mm and can be fixed or variable in size. The primary port, usually placed through the umbilicus, can be a standard, blunt, 10-mm (Hasson) port, or it can be specialized to ease entry of the port or stabilize the port once it is introduced through the skin incision.

Optical trocars have a transparent tip that allows the surgeon to visualize the abdominal-wall entry layer by layer using a 0° laparoscope, usually after pneumoperitoneum is created with a Veress needle. Other specialized ports include those that have balloons or foam collars, or both, to secure the port without traditional stay sutures on the fascia and minimize leakage of pneumoperitoneum.

Accessory ports

When choosing an accessory port type and size, it is important to anticipate what instruments and devices, such as an Endo Catch bag, suture, needle, or morcellator, will need to pass through it. Also know whether 5-mm and 10-mm laparoscopes are available, and anticipate whether a second port with insufflation capabilities will be required.

Related article: Update on Minimally Invasive Surgery Amy Garcia, MD (April 2011)

Pediport trocars are user-friendly 5-mm bladed ports that deploy a mushroom-shaped stabilizer to prevent dislodgement. A Versaport bladed trocar has a spring-loaded entry shield, which slides over to protect the blade once the peritoneal cavity is entered.

VersaStep bladeless trocars are introduced after a Step insufflation needle has been inserted. These trocars create a smaller fascial defect than conventional bladed trocars for an equivalent cannula size (TABLE 3).

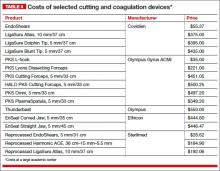

Cutting and coagulating

Both monopolar and bipolar electrosurgical techniques are commonly employed in gynecologic laparoscopy. A wide variety of disposable and reusable instruments are available for monopolar energy, such as scissors, a hook, and a spatula.

Bipolar devices also can be disposable or reusable. Although bipolar electrosurgery minimizes injury to surrounding tissues by containing the current within the jaws of the forceps, it cannot cut or seal large vessels. As a result, several advanced bipolar devices with sealing and transecting capabilities have emerged (LigaSure, ENSEAL). Ultrasonic devices also can coagulate and cut at lower temperatures by converting electrical energy to mechanical energy (TABLE 4).

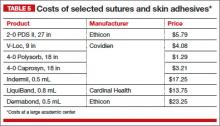

Sutures

Aspects of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery that require the use of suture include, but are not limited to, closure of the vaginal cuff, oophoropexy, and reapproximation of the ovarian cortex after cystectomy. Syntheticand delayed absorbable sutures, such as PDS II, are used frequently.

Recently, a new class of suture emerged and continues to gain popularity: barbed suture. This type of suture anchors to the tissue without the need for intra- or extracorporeal knots (TABLE 5).

Related article: Ins and outs of straight-stick laparoscopic myomectomy James Robinson, MD, MS, and Gaby Moawad, MD (September 2012)

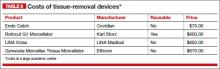

Tissue removal

Adnexae and pathologic tissue, such as dermoid cysts, can be removed intact from the peritoneal cavity using an Endo Catch Single-Use Specimen Pouch, a polyurethane sac. Careful use, with placement of the ovary with the cyst into the pouch prior to cystectomy, can prevent spillage beyond the bag.

Large uteri that cannot be extracted through a colpotomy can be morcellated into smaller pieces to ease removal through a small laparoscopic incision or the colpotomy. Both reusable and disposable morcellator hand pieces are available (TABLE 6).

Skin closure

Final subcuticular closure can be accomplished using sutures or skin adhesive. Sutures may be synthetic, absorbable monofilament (eg, Caprosyn), or synthetic, absorbable, braided multifilament (eg, PolySorb).

Related article: 10 practical, evidence-based recommendations for improving maternal outcomes of cesarean delivery Baha M. Sibai, MD (March 2012)

Skin adhesives close incisions quickly, avoid inflammation related to foreign bodies, and ease patient concerns that sometimes arise when absorbable suture persists postoperatively (TABLE 5).

Take-home points

As health-care third-party payers and hospitals continue to evaluate surgeons individually and compare procedures between surgeons, reimbursements may be stratified, favoring physicians who demonstrate both quality outcomes and cost-containment.

There are many ways a minimally invasive surgeon can implement cost-conscious choices that have little to no impact on the quality of the outcome.

Surgeons who are familiar with the instruments and models available for use at their institution are better prepared to make wise cost-conscious decisions.

Cost is not the only indicator of value, however. The surgeon must know how to apply tools correctly and be familiar with their limitations, and should choose instruments and products for their safety and ease of use. More often than not, a surgeon’s training and personal experience define—and sometimes restrict—the choice of devices.

CASE: SAME OUTCOME, LOWER COST

The patient undergoes laparoscopic hysterectomy for treatment of uterine fibroids and menorrhagia. However, in this scenario, the surgeon makes the following product choices: The patient is prepped with Betadine, and a reusable Pelosi uterine manipulator is placed. Laparoscopic ports include a Kii Balloon Blunt Tip, a reprocessed VersaStep Plus trocar, and two Pediport trocars. The surgeon uses the PKS Lyons Dissecting Forceps and reprocessed EndoShears to perform the hysterectomy, incorporating the Karl Storz Rotocut G1 Morcellator, a reusable system with single-use blades, to morcellate the uterus. The vaginal cuff is closed using V-Loc barbed suture, and skin incisions are closed with 4-0 Polysorb, a polyglycolic acid, absorbable suture.

The cost of these products: $1,005.68, or roughly $700 less than the set-up described at the beginning of this article (TABLE 7).

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Susan Wykoop, BSN, RN, and Anna Emery, MSN, RN, for their assistance in gathering specific cost-related information.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

- Health expenditure, total (% of GDP). The World Bank. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.TOTL.ZS. Accessed October 17, 2013.

- Vilos GA, Alshimmiri MM. Cost-benefit analysis of laparoscopic versus laparotomy salpingo-oophorectomy for benign tubo-ovarian disease. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1995;2(3):299–303.

- Gray DT, Thorburn J, Lundorff P, et al. A cost-effectiveness study of a randomized trial of laparoscopy versus laparotomy for ectopic pregnancy. Lancet. 1995;345(8958):1139–1143.

- Chapron C, Fauconnier A, Goffinet F, et al. Laparoscopic surgery is not inherently dangerous for patients presenting with benign gynaecologic pathology. Results of a meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(5):1334–1342.

- Hasson HM. A modified instrument and method for laparoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1971;110(6):886–887.

- Ahmad G, O’Flynn H, Duffy JM, Phillips K, Watson A. Laparoscopic entry techniques. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2:CD006583.

- Hasson HM, Rotman C, Rana N, Kumari NA. Open laparoscopy: 29-year experience. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96(5 Pt 1):763–766.

- Schafer M, Lauper M, Krahenbuhl L. Trocar and Veress needle injuries during laparoscopy. Surg Endosc. 2001;15(3):275–280.

CASE: COST-CONSCIOUS LAPAROSCOPIC HYSTERECTOMY

A 43-year-old woman undergoes laparoscopic hysterectomy for treatment of uterine fibroids and menorrhagia. Once she is prepped with ChloraPrep, a RUMI II uterine manipulator is placed. Laparoscopic ports include a Structural Balloon Trocar, a VersaStep Plus trocar, and two Versaport trocars. The surgeon uses an Olympus Thunderbeat device—a combination of ultrasonic and bipolar energy—to perform the majority of the procedure. The uterus is morcellated using the disposable Gynecare Morcellex, and the vaginal cuff is closed using a series of 2-0 PDS II sutures. The skin incisions are closed using Dermabond skin adhesive.

The total cost of the products used in this case: $1,705.60.

Could different product choices have reduced this figure?

As health-care costs continue to rise faster than inflation, with total health-care expenditures accounting for about 18% of the US gross domestic product, we face increasing pressure to take cost into account in the management of our patients.1 Not surprisingly, cost-effectiveness and outcome quality have become measures in many clinical trials that compare standard and alternative therapies. The field of women’s health—and, specifically, minimally invasive gynecologic surgery—is not immune to such comparisons.

Overall, conventional laparoscopic gynecologic procedures tend to have lower costs than laparotomy, due to shorter hospital stays, faster recovery, and fewer complications.2–4 What is not fully appreciated is how the choice of laparoscopic instrumentation and associated products affects surgical costs. In this article, we review these costs with the goal of raising awareness among minimally invasive gynecologic surgeons.

In the sections that follow, we highlight several aspects of laparoscopic gynecologic surgery that may affect your selection of instruments and products, describing the difference in cost as well as some unique characteristics of the products. Please note that our comparison focuses solely on cost, not ease of utility, effectiveness, surgical technique, risk of complications, or any other assessment. We’d also like to point out that numerous other instruments and devices are commercially available besides those listed in this article.

A few variables to keep in mind

Even when taking cost into consideration, tailor the selection of instruments and supplies to your capabilities and comfort, as well as characteristics particular to the patient and the planned procedure. Also keep in mind that your institution may have arrangements with companies that supply minimally invasive instruments, and such arrangements may limit your options to some degree. Be aware that reprocessed ports and instruments are now available at a reduced cost.

We believe it is crucial for surgeons to be cognizant of all products potentially available to them prior to attending a surgical case.

Related article: Update on Technology Barbara S. Levy, MD (September 2013)

Skin preparation and other preoperative considerations

Multiple preoperative skin preparations are available (TABLE 1). Traditionally, a povidone-iodine topical antiseptic such as Betadine has been used for skin and vaginal preparation prior to gynecologic surgery. Hibaclens and ChloraPrep are different combinations of chlorhexidine gluconate and isopropyl alcohol that act as broad-spectrum antiseptics. ChloraPrep is applied with a wand-like applicator and contains a much higher concentration of isopropyl alcohol than Hibaclens (70% vs 4%), rendering it more flammable. It also requires more drying time before the case is started. Clear and tinted ChloraPrep formulations are available.

It makes good sense to have instruments and devices readily available in the operating room (OR) at the start of a case, to avoid unnecessary surgical delays, but we recommend that you refrain from opening these tools until they are required intraoperatively. It is possible that the case will require conversion to laparotomy or that, after direct visualization of the pathology, different ports or instruments will be required.

Uterine manipulators

Cannulation of the cervical canal allows for uterine manipulation, increasing intraoperative traction and exposure and visualization of the adnexae and peritoneal surfaces.

The Hulka and Pelosi reusable uterine manipulators are fairly standard and easy to apply. Specialized, single-use manipulators also are available, including the VCare uterine manipulator/elevator, which consists of two opposing cups. One cup (available in four sizes, from small to extra-large) fits around the cervix and defines the site for colpotomy, and the other cup helps maintain pneumoperitoneum once a colpotomy is created.

The Zinnanti Uterine Manipulator Injector (ZUMI) is a rigid, curved shaft with an intrauterine balloon to help prevent expulsion. It also has an integrated injection channel to allow for intraoperative chromotubation.

The RUMI System fits individual patient anatomy with various tip lengths and colpotomy cup sizes (TABLE 2).

Related article: Tips and techniques for robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy Arnold P. Advincula, MD, and Bich-Van Tran, MD (August 2013)

Entry style and ports

The peritoneal cavity can be entered using either a closed (Veress needle) or open (Hasson) technique.5 Closed entry may allow for quicker access to the peritoneal cavity. A recent Cochrane review of 28 randomized, controlled trials, including 4,860 patients undergoing laparoscopy, compared outcomes between laparoscopic entry techniques.6 It found no difference in major vascular or visceral injury between closed and open techniques at the umbilicus. However, open entry was associated with greater successful entry into the peritoneal cavity, as well as less extraperitoneal insufflation and a lower omental injury rate, compared with closed entry.6

Left-upper-quadrant entry is another option when adhesions are anticipated or abnormal anatomy is encountered at the umbilicus.

In general, complications related to laparoscopic entry are quite rare in gynecologic surgery, ranging from 0.18% to 0.5%.7,8 A minimally invasive surgeon may prefer one entry technique over the other, but should be able to perform both methods competently and recognize when a particular technique is warranted.

Choosing a port

Laparoscopic ports usually range from 5 mm to 12 mm and can be fixed or variable in size. The primary port, usually placed through the umbilicus, can be a standard, blunt, 10-mm (Hasson) port, or it can be specialized to ease entry of the port or stabilize the port once it is introduced through the skin incision.

Optical trocars have a transparent tip that allows the surgeon to visualize the abdominal-wall entry layer by layer using a 0° laparoscope, usually after pneumoperitoneum is created with a Veress needle. Other specialized ports include those that have balloons or foam collars, or both, to secure the port without traditional stay sutures on the fascia and minimize leakage of pneumoperitoneum.

Accessory ports

When choosing an accessory port type and size, it is important to anticipate what instruments and devices, such as an Endo Catch bag, suture, needle, or morcellator, will need to pass through it. Also know whether 5-mm and 10-mm laparoscopes are available, and anticipate whether a second port with insufflation capabilities will be required.

Related article: Update on Minimally Invasive Surgery Amy Garcia, MD (April 2011)

Pediport trocars are user-friendly 5-mm bladed ports that deploy a mushroom-shaped stabilizer to prevent dislodgement. A Versaport bladed trocar has a spring-loaded entry shield, which slides over to protect the blade once the peritoneal cavity is entered.

VersaStep bladeless trocars are introduced after a Step insufflation needle has been inserted. These trocars create a smaller fascial defect than conventional bladed trocars for an equivalent cannula size (TABLE 3).

Cutting and coagulating

Both monopolar and bipolar electrosurgical techniques are commonly employed in gynecologic laparoscopy. A wide variety of disposable and reusable instruments are available for monopolar energy, such as scissors, a hook, and a spatula.

Bipolar devices also can be disposable or reusable. Although bipolar electrosurgery minimizes injury to surrounding tissues by containing the current within the jaws of the forceps, it cannot cut or seal large vessels. As a result, several advanced bipolar devices with sealing and transecting capabilities have emerged (LigaSure, ENSEAL). Ultrasonic devices also can coagulate and cut at lower temperatures by converting electrical energy to mechanical energy (TABLE 4).

Sutures

Aspects of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery that require the use of suture include, but are not limited to, closure of the vaginal cuff, oophoropexy, and reapproximation of the ovarian cortex after cystectomy. Syntheticand delayed absorbable sutures, such as PDS II, are used frequently.

Recently, a new class of suture emerged and continues to gain popularity: barbed suture. This type of suture anchors to the tissue without the need for intra- or extracorporeal knots (TABLE 5).

Related article: Ins and outs of straight-stick laparoscopic myomectomy James Robinson, MD, MS, and Gaby Moawad, MD (September 2012)

Tissue removal

Adnexae and pathologic tissue, such as dermoid cysts, can be removed intact from the peritoneal cavity using an Endo Catch Single-Use Specimen Pouch, a polyurethane sac. Careful use, with placement of the ovary with the cyst into the pouch prior to cystectomy, can prevent spillage beyond the bag.

Large uteri that cannot be extracted through a colpotomy can be morcellated into smaller pieces to ease removal through a small laparoscopic incision or the colpotomy. Both reusable and disposable morcellator hand pieces are available (TABLE 6).

Skin closure

Final subcuticular closure can be accomplished using sutures or skin adhesive. Sutures may be synthetic, absorbable monofilament (eg, Caprosyn), or synthetic, absorbable, braided multifilament (eg, PolySorb).

Related article: 10 practical, evidence-based recommendations for improving maternal outcomes of cesarean delivery Baha M. Sibai, MD (March 2012)

Skin adhesives close incisions quickly, avoid inflammation related to foreign bodies, and ease patient concerns that sometimes arise when absorbable suture persists postoperatively (TABLE 5).

Take-home points

As health-care third-party payers and hospitals continue to evaluate surgeons individually and compare procedures between surgeons, reimbursements may be stratified, favoring physicians who demonstrate both quality outcomes and cost-containment.

There are many ways a minimally invasive surgeon can implement cost-conscious choices that have little to no impact on the quality of the outcome.

Surgeons who are familiar with the instruments and models available for use at their institution are better prepared to make wise cost-conscious decisions.

Cost is not the only indicator of value, however. The surgeon must know how to apply tools correctly and be familiar with their limitations, and should choose instruments and products for their safety and ease of use. More often than not, a surgeon’s training and personal experience define—and sometimes restrict—the choice of devices.

CASE: SAME OUTCOME, LOWER COST

The patient undergoes laparoscopic hysterectomy for treatment of uterine fibroids and menorrhagia. However, in this scenario, the surgeon makes the following product choices: The patient is prepped with Betadine, and a reusable Pelosi uterine manipulator is placed. Laparoscopic ports include a Kii Balloon Blunt Tip, a reprocessed VersaStep Plus trocar, and two Pediport trocars. The surgeon uses the PKS Lyons Dissecting Forceps and reprocessed EndoShears to perform the hysterectomy, incorporating the Karl Storz Rotocut G1 Morcellator, a reusable system with single-use blades, to morcellate the uterus. The vaginal cuff is closed using V-Loc barbed suture, and skin incisions are closed with 4-0 Polysorb, a polyglycolic acid, absorbable suture.

The cost of these products: $1,005.68, or roughly $700 less than the set-up described at the beginning of this article (TABLE 7).

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Susan Wykoop, BSN, RN, and Anna Emery, MSN, RN, for their assistance in gathering specific cost-related information.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

CASE: COST-CONSCIOUS LAPAROSCOPIC HYSTERECTOMY

A 43-year-old woman undergoes laparoscopic hysterectomy for treatment of uterine fibroids and menorrhagia. Once she is prepped with ChloraPrep, a RUMI II uterine manipulator is placed. Laparoscopic ports include a Structural Balloon Trocar, a VersaStep Plus trocar, and two Versaport trocars. The surgeon uses an Olympus Thunderbeat device—a combination of ultrasonic and bipolar energy—to perform the majority of the procedure. The uterus is morcellated using the disposable Gynecare Morcellex, and the vaginal cuff is closed using a series of 2-0 PDS II sutures. The skin incisions are closed using Dermabond skin adhesive.

The total cost of the products used in this case: $1,705.60.

Could different product choices have reduced this figure?

As health-care costs continue to rise faster than inflation, with total health-care expenditures accounting for about 18% of the US gross domestic product, we face increasing pressure to take cost into account in the management of our patients.1 Not surprisingly, cost-effectiveness and outcome quality have become measures in many clinical trials that compare standard and alternative therapies. The field of women’s health—and, specifically, minimally invasive gynecologic surgery—is not immune to such comparisons.

Overall, conventional laparoscopic gynecologic procedures tend to have lower costs than laparotomy, due to shorter hospital stays, faster recovery, and fewer complications.2–4 What is not fully appreciated is how the choice of laparoscopic instrumentation and associated products affects surgical costs. In this article, we review these costs with the goal of raising awareness among minimally invasive gynecologic surgeons.

In the sections that follow, we highlight several aspects of laparoscopic gynecologic surgery that may affect your selection of instruments and products, describing the difference in cost as well as some unique characteristics of the products. Please note that our comparison focuses solely on cost, not ease of utility, effectiveness, surgical technique, risk of complications, or any other assessment. We’d also like to point out that numerous other instruments and devices are commercially available besides those listed in this article.

A few variables to keep in mind

Even when taking cost into consideration, tailor the selection of instruments and supplies to your capabilities and comfort, as well as characteristics particular to the patient and the planned procedure. Also keep in mind that your institution may have arrangements with companies that supply minimally invasive instruments, and such arrangements may limit your options to some degree. Be aware that reprocessed ports and instruments are now available at a reduced cost.

We believe it is crucial for surgeons to be cognizant of all products potentially available to them prior to attending a surgical case.

Related article: Update on Technology Barbara S. Levy, MD (September 2013)

Skin preparation and other preoperative considerations

Multiple preoperative skin preparations are available (TABLE 1). Traditionally, a povidone-iodine topical antiseptic such as Betadine has been used for skin and vaginal preparation prior to gynecologic surgery. Hibaclens and ChloraPrep are different combinations of chlorhexidine gluconate and isopropyl alcohol that act as broad-spectrum antiseptics. ChloraPrep is applied with a wand-like applicator and contains a much higher concentration of isopropyl alcohol than Hibaclens (70% vs 4%), rendering it more flammable. It also requires more drying time before the case is started. Clear and tinted ChloraPrep formulations are available.

It makes good sense to have instruments and devices readily available in the operating room (OR) at the start of a case, to avoid unnecessary surgical delays, but we recommend that you refrain from opening these tools until they are required intraoperatively. It is possible that the case will require conversion to laparotomy or that, after direct visualization of the pathology, different ports or instruments will be required.

Uterine manipulators

Cannulation of the cervical canal allows for uterine manipulation, increasing intraoperative traction and exposure and visualization of the adnexae and peritoneal surfaces.

The Hulka and Pelosi reusable uterine manipulators are fairly standard and easy to apply. Specialized, single-use manipulators also are available, including the VCare uterine manipulator/elevator, which consists of two opposing cups. One cup (available in four sizes, from small to extra-large) fits around the cervix and defines the site for colpotomy, and the other cup helps maintain pneumoperitoneum once a colpotomy is created.

The Zinnanti Uterine Manipulator Injector (ZUMI) is a rigid, curved shaft with an intrauterine balloon to help prevent expulsion. It also has an integrated injection channel to allow for intraoperative chromotubation.

The RUMI System fits individual patient anatomy with various tip lengths and colpotomy cup sizes (TABLE 2).

Related article: Tips and techniques for robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy Arnold P. Advincula, MD, and Bich-Van Tran, MD (August 2013)

Entry style and ports

The peritoneal cavity can be entered using either a closed (Veress needle) or open (Hasson) technique.5 Closed entry may allow for quicker access to the peritoneal cavity. A recent Cochrane review of 28 randomized, controlled trials, including 4,860 patients undergoing laparoscopy, compared outcomes between laparoscopic entry techniques.6 It found no difference in major vascular or visceral injury between closed and open techniques at the umbilicus. However, open entry was associated with greater successful entry into the peritoneal cavity, as well as less extraperitoneal insufflation and a lower omental injury rate, compared with closed entry.6

Left-upper-quadrant entry is another option when adhesions are anticipated or abnormal anatomy is encountered at the umbilicus.

In general, complications related to laparoscopic entry are quite rare in gynecologic surgery, ranging from 0.18% to 0.5%.7,8 A minimally invasive surgeon may prefer one entry technique over the other, but should be able to perform both methods competently and recognize when a particular technique is warranted.

Choosing a port

Laparoscopic ports usually range from 5 mm to 12 mm and can be fixed or variable in size. The primary port, usually placed through the umbilicus, can be a standard, blunt, 10-mm (Hasson) port, or it can be specialized to ease entry of the port or stabilize the port once it is introduced through the skin incision.

Optical trocars have a transparent tip that allows the surgeon to visualize the abdominal-wall entry layer by layer using a 0° laparoscope, usually after pneumoperitoneum is created with a Veress needle. Other specialized ports include those that have balloons or foam collars, or both, to secure the port without traditional stay sutures on the fascia and minimize leakage of pneumoperitoneum.

Accessory ports

When choosing an accessory port type and size, it is important to anticipate what instruments and devices, such as an Endo Catch bag, suture, needle, or morcellator, will need to pass through it. Also know whether 5-mm and 10-mm laparoscopes are available, and anticipate whether a second port with insufflation capabilities will be required.

Related article: Update on Minimally Invasive Surgery Amy Garcia, MD (April 2011)

Pediport trocars are user-friendly 5-mm bladed ports that deploy a mushroom-shaped stabilizer to prevent dislodgement. A Versaport bladed trocar has a spring-loaded entry shield, which slides over to protect the blade once the peritoneal cavity is entered.

VersaStep bladeless trocars are introduced after a Step insufflation needle has been inserted. These trocars create a smaller fascial defect than conventional bladed trocars for an equivalent cannula size (TABLE 3).

Cutting and coagulating

Both monopolar and bipolar electrosurgical techniques are commonly employed in gynecologic laparoscopy. A wide variety of disposable and reusable instruments are available for monopolar energy, such as scissors, a hook, and a spatula.

Bipolar devices also can be disposable or reusable. Although bipolar electrosurgery minimizes injury to surrounding tissues by containing the current within the jaws of the forceps, it cannot cut or seal large vessels. As a result, several advanced bipolar devices with sealing and transecting capabilities have emerged (LigaSure, ENSEAL). Ultrasonic devices also can coagulate and cut at lower temperatures by converting electrical energy to mechanical energy (TABLE 4).

Sutures

Aspects of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery that require the use of suture include, but are not limited to, closure of the vaginal cuff, oophoropexy, and reapproximation of the ovarian cortex after cystectomy. Syntheticand delayed absorbable sutures, such as PDS II, are used frequently.

Recently, a new class of suture emerged and continues to gain popularity: barbed suture. This type of suture anchors to the tissue without the need for intra- or extracorporeal knots (TABLE 5).

Related article: Ins and outs of straight-stick laparoscopic myomectomy James Robinson, MD, MS, and Gaby Moawad, MD (September 2012)

Tissue removal

Adnexae and pathologic tissue, such as dermoid cysts, can be removed intact from the peritoneal cavity using an Endo Catch Single-Use Specimen Pouch, a polyurethane sac. Careful use, with placement of the ovary with the cyst into the pouch prior to cystectomy, can prevent spillage beyond the bag.

Large uteri that cannot be extracted through a colpotomy can be morcellated into smaller pieces to ease removal through a small laparoscopic incision or the colpotomy. Both reusable and disposable morcellator hand pieces are available (TABLE 6).

Skin closure

Final subcuticular closure can be accomplished using sutures or skin adhesive. Sutures may be synthetic, absorbable monofilament (eg, Caprosyn), or synthetic, absorbable, braided multifilament (eg, PolySorb).

Related article: 10 practical, evidence-based recommendations for improving maternal outcomes of cesarean delivery Baha M. Sibai, MD (March 2012)

Skin adhesives close incisions quickly, avoid inflammation related to foreign bodies, and ease patient concerns that sometimes arise when absorbable suture persists postoperatively (TABLE 5).

Take-home points

As health-care third-party payers and hospitals continue to evaluate surgeons individually and compare procedures between surgeons, reimbursements may be stratified, favoring physicians who demonstrate both quality outcomes and cost-containment.

There are many ways a minimally invasive surgeon can implement cost-conscious choices that have little to no impact on the quality of the outcome.

Surgeons who are familiar with the instruments and models available for use at their institution are better prepared to make wise cost-conscious decisions.

Cost is not the only indicator of value, however. The surgeon must know how to apply tools correctly and be familiar with their limitations, and should choose instruments and products for their safety and ease of use. More often than not, a surgeon’s training and personal experience define—and sometimes restrict—the choice of devices.

CASE: SAME OUTCOME, LOWER COST

The patient undergoes laparoscopic hysterectomy for treatment of uterine fibroids and menorrhagia. However, in this scenario, the surgeon makes the following product choices: The patient is prepped with Betadine, and a reusable Pelosi uterine manipulator is placed. Laparoscopic ports include a Kii Balloon Blunt Tip, a reprocessed VersaStep Plus trocar, and two Pediport trocars. The surgeon uses the PKS Lyons Dissecting Forceps and reprocessed EndoShears to perform the hysterectomy, incorporating the Karl Storz Rotocut G1 Morcellator, a reusable system with single-use blades, to morcellate the uterus. The vaginal cuff is closed using V-Loc barbed suture, and skin incisions are closed with 4-0 Polysorb, a polyglycolic acid, absorbable suture.

The cost of these products: $1,005.68, or roughly $700 less than the set-up described at the beginning of this article (TABLE 7).

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Susan Wykoop, BSN, RN, and Anna Emery, MSN, RN, for their assistance in gathering specific cost-related information.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

- Health expenditure, total (% of GDP). The World Bank. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.TOTL.ZS. Accessed October 17, 2013.

- Vilos GA, Alshimmiri MM. Cost-benefit analysis of laparoscopic versus laparotomy salpingo-oophorectomy for benign tubo-ovarian disease. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1995;2(3):299–303.

- Gray DT, Thorburn J, Lundorff P, et al. A cost-effectiveness study of a randomized trial of laparoscopy versus laparotomy for ectopic pregnancy. Lancet. 1995;345(8958):1139–1143.

- Chapron C, Fauconnier A, Goffinet F, et al. Laparoscopic surgery is not inherently dangerous for patients presenting with benign gynaecologic pathology. Results of a meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(5):1334–1342.

- Hasson HM. A modified instrument and method for laparoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1971;110(6):886–887.

- Ahmad G, O’Flynn H, Duffy JM, Phillips K, Watson A. Laparoscopic entry techniques. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2:CD006583.

- Hasson HM, Rotman C, Rana N, Kumari NA. Open laparoscopy: 29-year experience. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96(5 Pt 1):763–766.

- Schafer M, Lauper M, Krahenbuhl L. Trocar and Veress needle injuries during laparoscopy. Surg Endosc. 2001;15(3):275–280.

- Health expenditure, total (% of GDP). The World Bank. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.TOTL.ZS. Accessed October 17, 2013.

- Vilos GA, Alshimmiri MM. Cost-benefit analysis of laparoscopic versus laparotomy salpingo-oophorectomy for benign tubo-ovarian disease. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1995;2(3):299–303.

- Gray DT, Thorburn J, Lundorff P, et al. A cost-effectiveness study of a randomized trial of laparoscopy versus laparotomy for ectopic pregnancy. Lancet. 1995;345(8958):1139–1143.

- Chapron C, Fauconnier A, Goffinet F, et al. Laparoscopic surgery is not inherently dangerous for patients presenting with benign gynaecologic pathology. Results of a meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(5):1334–1342.

- Hasson HM. A modified instrument and method for laparoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1971;110(6):886–887.

- Ahmad G, O’Flynn H, Duffy JM, Phillips K, Watson A. Laparoscopic entry techniques. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2:CD006583.

- Hasson HM, Rotman C, Rana N, Kumari NA. Open laparoscopy: 29-year experience. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96(5 Pt 1):763–766.

- Schafer M, Lauper M, Krahenbuhl L. Trocar and Veress needle injuries during laparoscopy. Surg Endosc. 2001;15(3):275–280.