User login

Community-Acquired Pneumonia: Treatment

Initial management decisions for patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) will depend on severity of infection, with need for hospitalization being one of the first decisions. Because empiric antibiotics are the mainstay of treatment and the causative organisms are seldom identified, underlying medical conditions and epidemiologic risk factors are considered when selecting an empiric regimen. As with other infections, duration of therapy is not standardized, but rather is guided by clinical improvement. Prevention of pneumonia centers around vaccination and smoking cessation. This article, the second in a 2-part review of CAP in adults, focuses on site of care decision, empiric and directed therapies, length of treatment, and prevention strategies. Evaluation and diagnosis of CAP are discussed in a separate article.

Site of Care Decision

For patients diagnosed with CAP, the clinician must decide whether treatment will be done in an outpatient or inpatient setting, and for those in the inpatient setting, whether they can safely be treated on the general medical ward or in the intensive care unit (ICU). Two common scoring systems that can be used to aid the clinician in determining severity of the infection and guide site-of-care decisions are the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) and CURB-65 scores.

The PSI score uses 20 different parameters, including comorbidities, laboratory parameters, and radiographic findings, to stratify patients into 5 mortality risk classes.1 On the basis of associated mortality rates, it has been suggested that risk class I and II patients should be treated as outpatients, risk class III patients should be treated in an observation unit or with a short hospitalization, and risk class IV and V patients should be treated as inpatients.1

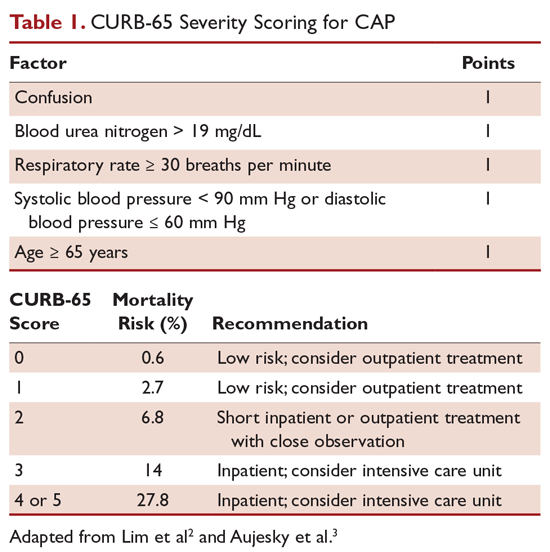

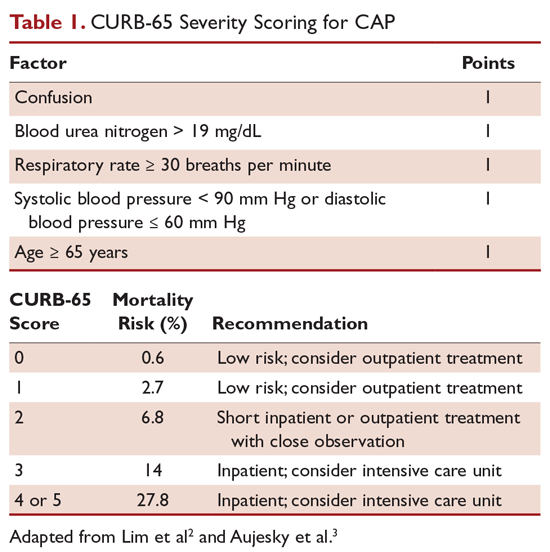

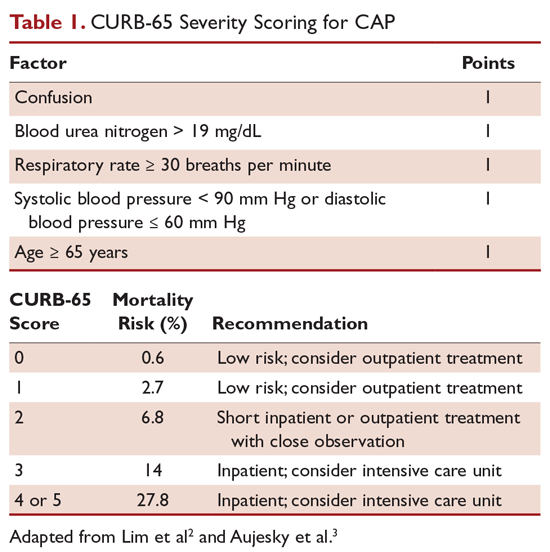

The CURB-65 method of risk stratification is based on 5 clinical parameters: confusion, urea level, respiratory rate, systolic blood pressure, and age ≥ 65 years (Table 1).2,3 A modification to the CURB-65 algorithm tool was CRB-65, which excludes urea nitrogen, making it optimal for making determinations in a clinic-based setting. It should be emphasized that these tools do not take into account other factors that should be used in determining location of treatment, such as stable home, mental illness, or concerns about compliance with medications. In many instances, it is these factors that preclude low-risk patients from being treated as outpatients.4,5 Similarly, these scoring systems have not been validated for immunocompromised patients or those who would qualify as having health care–associated pneumonia.

Patients with CURB-65 scores of 4 or 5 are considered to have severe pneumonia, and admission to the ICU should be considered for these patients. Aside from the CURB-65 score, anyone requiring vasopressor support or mechanical ventilation merits admission to the ICU.6 American Thoracic Society (ATS) and Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines also recommend the use of “minor criteria” for making ICU admission decisions; these include respiratory rate ≥ 30 breaths/minute, PaO2 fraction ≤ 250 mm Hg, multilobar infiltrates, confusion, blood urea nitrogen ≥ 20 mg/dL, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, hypothermia, and hypotension.6 These factors are associated with increased mortality due to CAP, and ICU admission is indicated if 3 of the minor criteria for severe CAP are present.

Another clinical calculator that can be used for assessing severity of CAP is SMART-COP (systolic blood pressure, multilobar chest radiography involvement, albumin level, respiratory rate, tachycardia, confusion, oxygenation and arterial pH).7 This scoring system uses 8 weighted criteria to predict which patients will require intensive respiratory or vasopressor support. SMART-COP has a sensitivity of 79% and a specificity of 64% in predicting ICU admission, whereas CURB-65 has a pooled sensitivity of 57.2% and specificity of 77.2%.8

Antibiotic Therapy

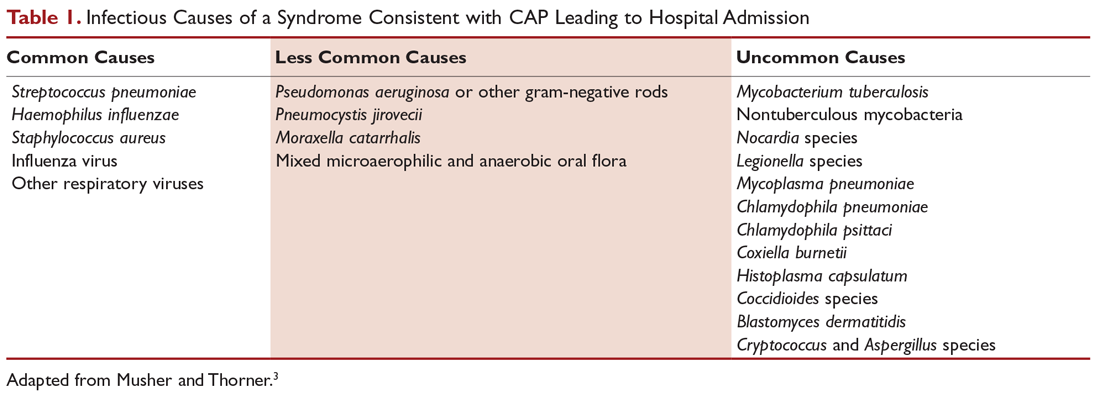

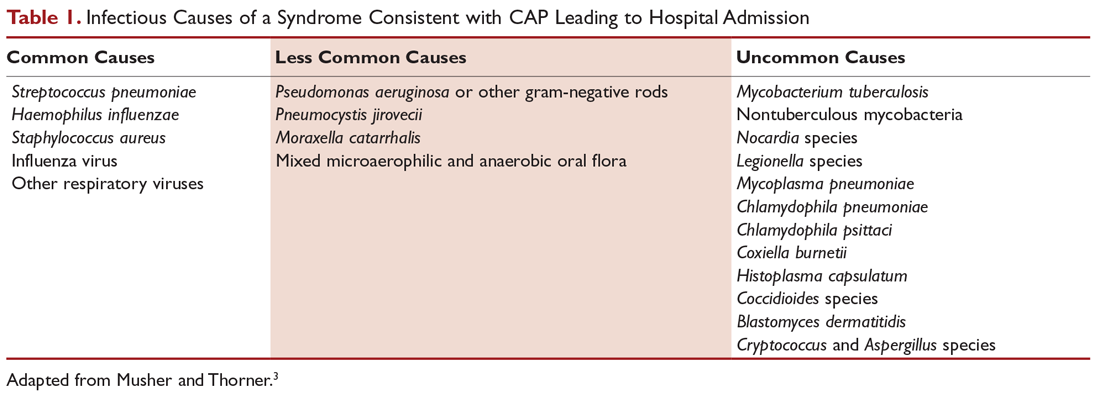

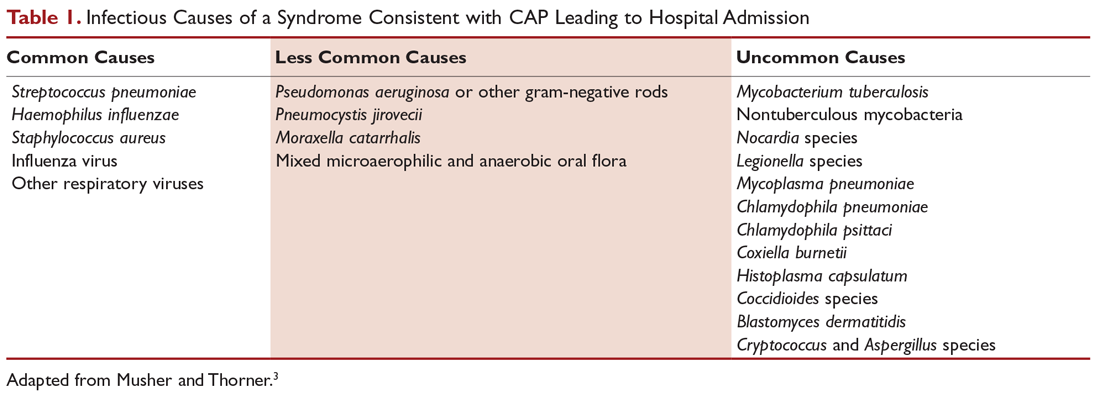

Antibiotics are the mainstay of treatment for CAP, with the majority of patients with CAP treated empirically taking into account the site of care, likely pathogen, and antimicrobial resistance issues. Patients with pneumonia who are treated as outpatients usually respond well to empiric antibiotic treatment, and a causative pathogen is not usually sought. Patients who are hospitalized for treatment of CAP usually receive empiric antibiotic on admission. Once the etiology has been determined by microbiologic or serologic means, antimicrobial therapy should be adjusted accordingly. A CDC study found that the burden of viral etiologies was higher than previously thought, with rhinovirus and influenza accounting for 15% of cases and Streptococcus pneumoniae for only 5%.9 This study highlighted the fact that despite advances in molecular techniques, no pathogen is identified for most patients with pneumonia.9 Given the lack of discernable pathogens in the majority of cases, patients should continue to be treated with antibiotics unless a nonbacterial etiology is found.

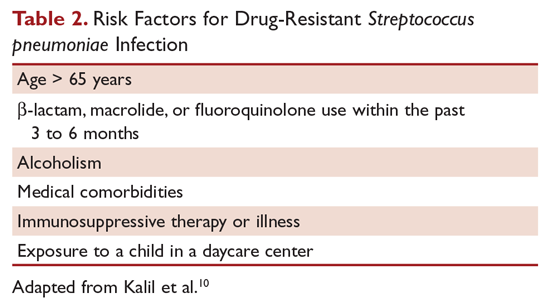

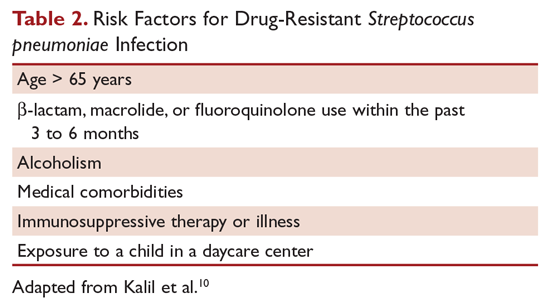

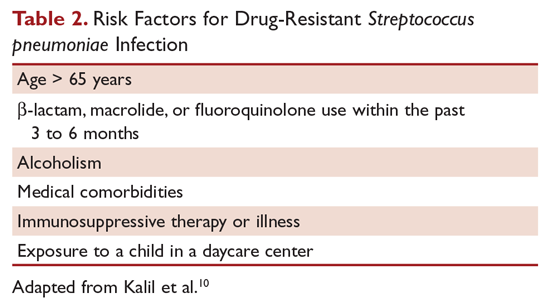

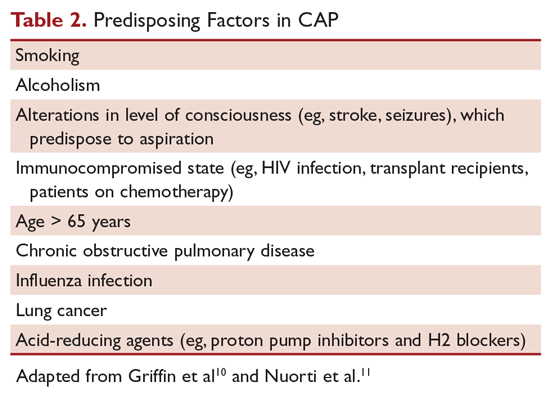

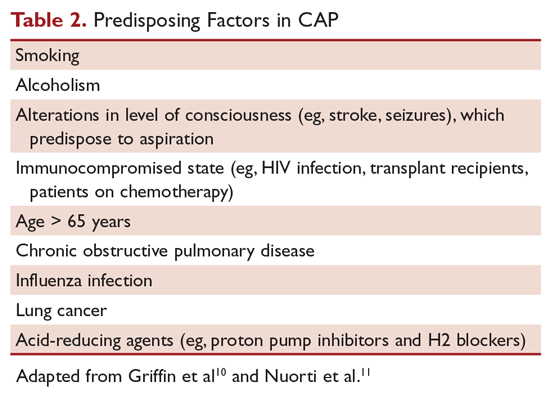

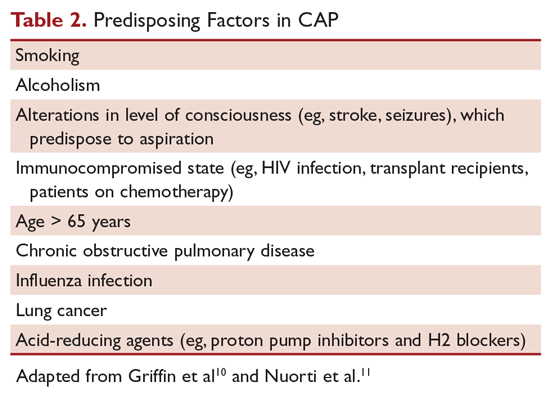

Outpatients without comorbidities or risk factors for drug-resistant S. pneumoniae (Table 2)10 can be treated with monotherapy. Hospitalized patients are usually treated with combination intravenous therapy, although non-ICU patients who receive a respiratory fluoroquinolone can be treated orally.

As previously mentioned, antibiotic therapy is typically empiric, since neither clinical features nor radiographic features are sufficient to include or exclude infectious etiologies. Epidemiologic risk factors should be considered and, in certain cases, antimicrobial coverage should be expanded to include those entities; for example, treatment of anaerobes in the setting of lung abscess and antipseudomonal antibiotics for patients with bronchiectasis.

Of concern in the treatment of CAP is the increased prevalence of antimicrobial resistance among S. pneumoniae. The IDSA guidelines report that drug-resistant S. pneumoniae is more common in persons aged < 2 or > 65 years, and those with β-lactam therapy within the previous 3 months, alcoholism, medical comorbidities, immunosuppressive illness or therapy, or exposure to a child who attends a day care center.6

Staphylococcus aureus should be considered during influenza outbreaks, with either vancomycin or linezolid being the recommended agents in the setting of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA). In a study comparing vancomycin versus linezolid for nosocomial pneumonia, the all-cause 60-day mortality was similar for both agents.11 Daptomycin, another agent used against MRSA, is not indicated in the setting of pneumonia because daptomycin binds to surfactant, yielding it ineffective in the treatment of pneumonia.12 Ceftaroline is a newer cephalosporin with activity against MRSA; its role in treatment of community-acquired MRSA pneumonia has not been fully elucidated, but it appears to be a useful agent for this indication.13,14 Similarly, other agents known to have antibacterial properties against MRSA, such as trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and doxycycline, have not been studied for this indication. Clindamycin has been used to treat MRSA in children, and IDSA guidelines on the treatment of MRSA list clindamycin as an alternative15 if MRSA is known to be sensitive.

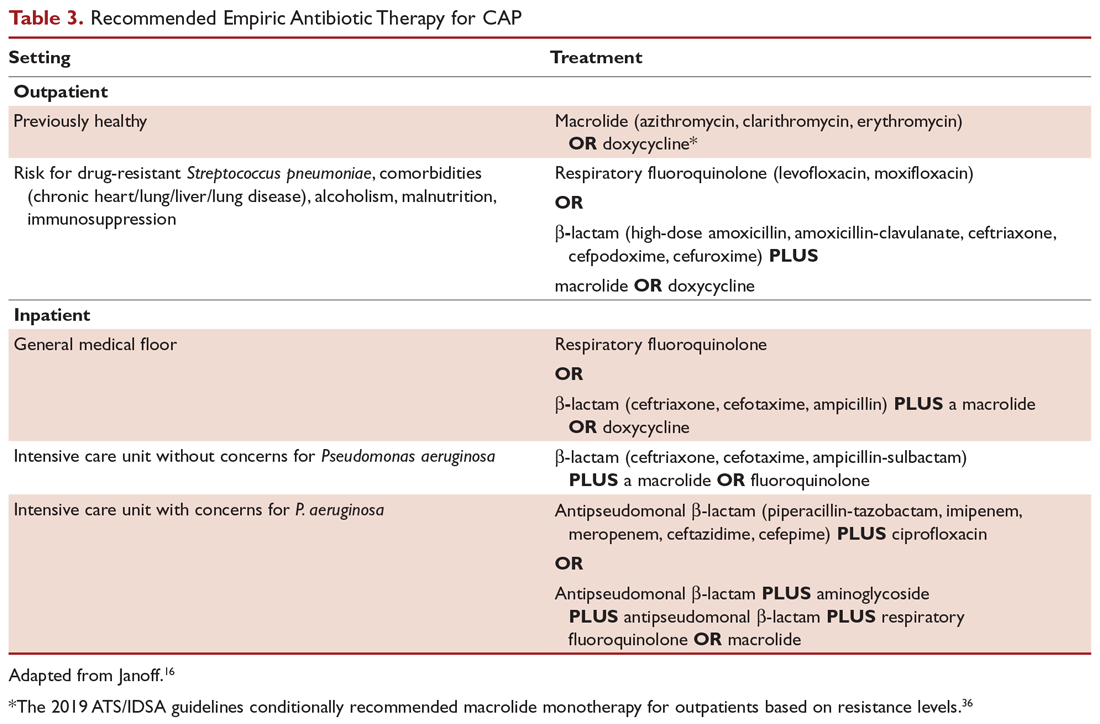

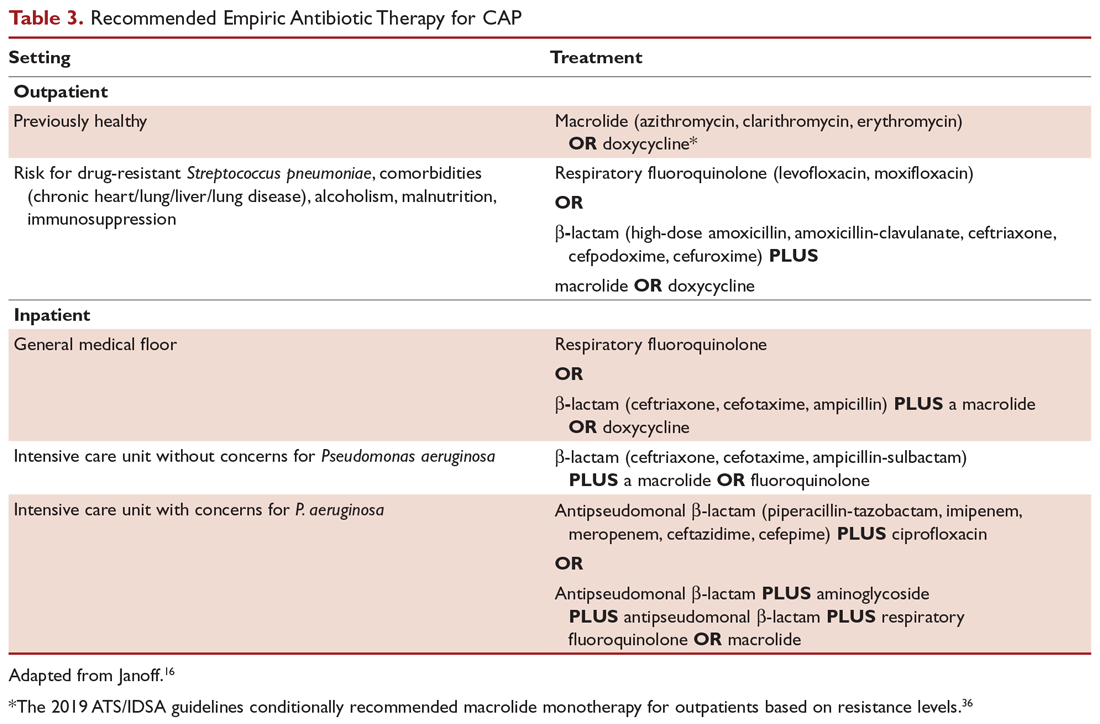

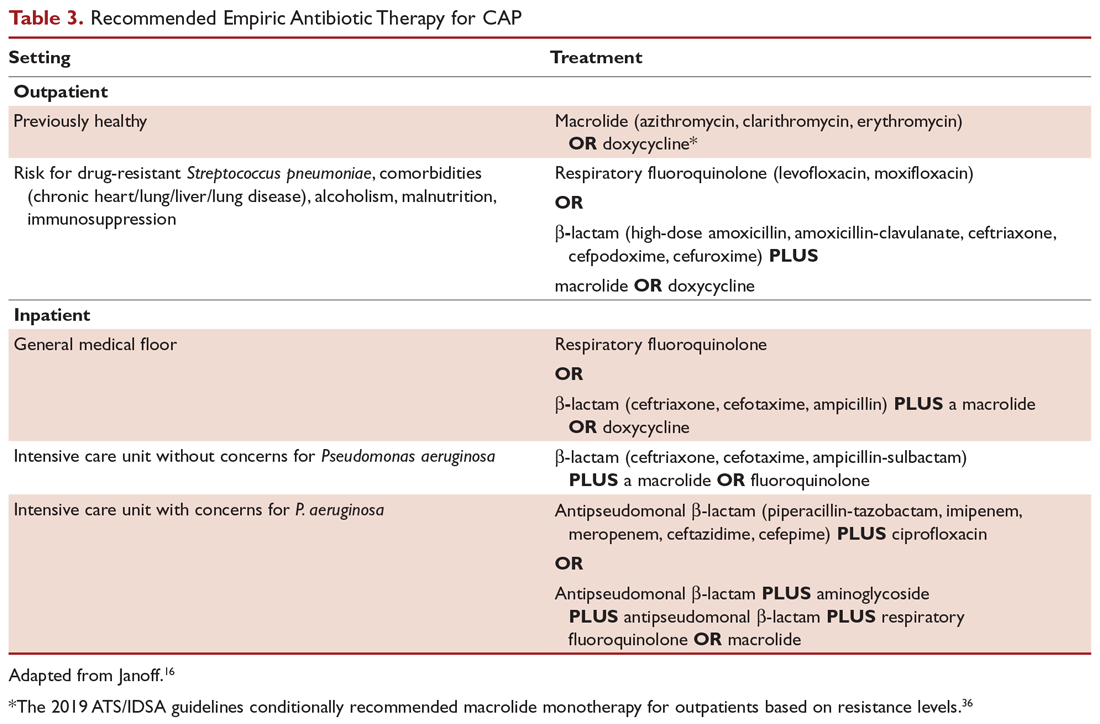

A summary of recommended empiric antibiotic therapy is presented in Table 3.16

Three antibiotics were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of CAP after the release of the IDSA/ATS guidelines in 2007. Ceftaroline fosamil is a fifth-generation cephalosporin that has coverage for MRSA and was approved in November 2010.17 It can only be administered intravenously and needs dose adjustment for renal function. Omadacycline is a new tetracycline that was approved by the FDA in October 2018.18 It is available in both intravenous injectable and oral forms. No dose adjustment is needed for renal function. Lefamulin is a first-in-class novel pleuromutilin antibiotic which was FDA-approved in August 2019. It can be administered intravenously or orally, with no dosage adjustment necessary in patients with renal impairment.19

Antibiotic Therapy for Selected Pathogens

Streptococcus pneumoniae

Patients with pneumococcal pneumonia who have penicillin-susceptible strains can be treated with intravenous penicillin (2 or 3 million units every 4 hours) or ceftriaxone. Once a patient meets criteria of stability, they can then be transitioned to oral penicillin, amoxicillin, or clarithromycin. Those with strains with reduced susceptibility can still be treated with penicillin, but at a higher dose (4 million units intravenously [IV] every 4 hours), or a third-generation cephalosporin. Those whose pneumococcal pneumonia is complicated by bacteremia will benefit from dual therapy if severely ill, requiring ICU monitoring. Those not severely ill can be treated with monotherapy.20

Staphylococcus aureus

Staphylococcus aureus is more commonly associated with hospital-acquired pneumonia, but it may also be seen during the influenza season and in those with severe necrotizing CAP. Both linezolid and vancomycin can be used to treat MRSA CAP. As noted, ceftaroline has activity against MRSA and is approved for treatment of CAP, but is not approved by the FDA for MRSA CAP treatment. Similarly, tigecycline is approved for CAP and has activity against MRSA, but is not approved for MRSA CAP. Moreover, the FDA has warned of increased risk of death with tigecycline and has a black box warning to that effect.21

Legionella

Legionellosis can be treated with tetra¬cyclines, macrolides, or fluoroquinolones. For non-immunocompromised patients with mild pneumonia, any of the listed antibiotics is considered appropriate. However, patients with severe infection or those with immunosuppression should be treated with either levofloxacin or azithromycin for 7 to 10 days.22

Chlamydophila pneumoniae

As with other atypical organisms, Chlamydophila pneumoniae can be treated with doxycycline, a macrolide, or respiratory fluoroquinolones. However, length of therapy varies by regimen used; treating with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily generally requires 14 to 21 days, whereas moxifloxacin 400 mg daily requires 10 days.23

Mycoplasma pneumoniae

As with C. pneumoniae, length of therapy of Mycoplasma pneumoniae varies by which antimicrobial regimen is used. Shortest courses are seen with the use of macrolides for 5 days, whereas 14 days is considered standard for doxycycline or a respiratory fluoroquinolone.24 It should be noted that there has been increasingly documented resistance to macrolides, with known resistance of 8.2% in the United States.25

Duration of Treatment

Most patients with CAP respond to appropriate therapy within 72 hours. IDSA/ATS guidelines recommend that patients with routine cases of CAP be treated for a minimum of 5 days. Despite this, many patients are treated for an excessive amount of time, with over 70% of patients reported to have received antibiotics for more than 10 days for uncomplicated CAP.26 There are instances that require longer courses of antibiotics, including cases caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, S. aureus, and Legionella species and patients with lung abscesses or necrotizing infections, among others.27

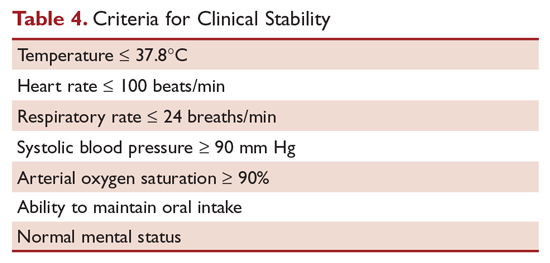

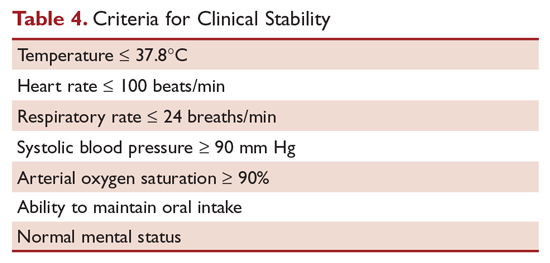

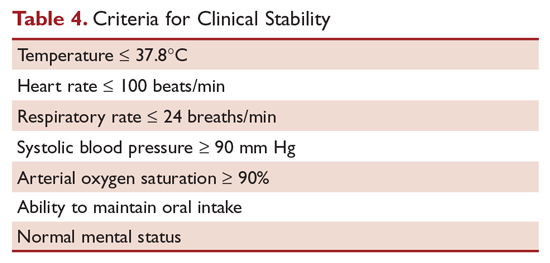

Hospitalized patients do not need to be monitored for an additional day once they have reached clinical stability (Table 4), are able to maintain oral intake, and have normal mentation, provided that other comorbidities are stable and social needs have been met.6 C-reactive protein (CRP) level has been postulated as an additional measure of stability, specifically monitoring for a greater than 50% reduction in CRP; however, this was validated only for those with complicated pneumonia.28 Patients discharged from the hospital with instability have higher risk of readmission or death.29

Transition to Oral Therapy

IDSA/ATS guidelines6 recommend that patients should be transitioned from intravenous to oral antibiotics when they are improving clinically, have stable vital signs, and are able to ingest food/fluids and medications.

Management of Nonresponders

Although the majority of patients respond to antibiotics within 72 hours, treatment failure occurs in up to 15% of patients.15 Nonresponding pneumonia is generally seen in 2 patterns: worsening of clinical status despite empiric antibiotics or delay in achieving clinical stability, as defined in Table 4, after 72 hours of treatment.30 Risk factors associated with nonresponding pneumonia31 are:

- Radiographic: multilobar infiltrates, pleural effusion, cavitation

- Bacteriologic: MRSA, gram-negative or Legionella pneumonia

- Severity index: PSI > 90

- Pharmacologic: incorrect antibiotic choice based on susceptibility

Patients with acute deterioration of clinical status require prompt transfer to a higher level of care and may require mechanical ventilator support. In those with delay in achieving clinical stability, a question centers on whether the same antibiotics can be continued while doing further radiographic/microbiologic work-up and/or changing antibiotics. History should be reviewed, with particular attention to exposures, travel history, and microbiologic and radiographic data. Clinicians should recall that viruses account for up to 20% of pneumonias and that there are also noninfectious causes that can mimic pyogenic infections.32 If adequate initial cultures were not obtained, they should be obtained; however, care must be taken in reviewing new sets of cultures while on antibiotics, as they may reveal colonization selected out by antibiotics and not a true pathogen. If repeat evaluation is unrevealing, then further evaluation with computed tomography (CT) scan and bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage and biopsy is warranted. CT scans can show pleural effusions, bronchial obstructions, or a pattern suggestive of cryptogenic pneumonia. A bronchoscopy might yield a microbiologic diagnosis and, when combined with biopsy, can also evaluate for noninfectious causes.

As with other infections, if escalation of antibiotics is undertaken, clinicians should try to determine the reason for nonresponse. To simply broaden antimicrobial therapy without attempts at establishing a microbiologic or radiographic cause for nonresponse may lead to inappropriate treatment and recurrence of infection. Aside from patients who have bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia in an ICU setting, there are no published reports pointing to superiority of combination antibiotics.20

Other Treatment

Several agents have been evaluated as adjunctive treatment of pneumonia to decrease the inflammatory response associated with pneumonia; namely, steroids, macrolide antibiotics, and statins. To date, only the use of steroids (methylprednisolone 0.5 mg/kg every 12 hours for 5 days) in those with severe CAP and high initial anti-inflammatory response (CRP > 150) has been shown to decrease treatment failure, decrease risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome, and possibly reduce length of stay and duration of intravenous antibiotics, without effect on mortality or adverse side effects.33,34 However, a recent double-blind randomized study conducted in Australia in which patients admitted with CAP were prescribed prednisolone acetate (50 mg/day for 7 days) and de-escalated from parenteral to oral antibiotics according to standardized criteria revealed no difference in mortality, length of stay, or readmission rates between the corticosteroids group and the control group at 90-day follow-up.35 At this point, corticosteroid as an adjunctive treatment for CAP is still controversial and the new 2019 ATS/IDSA guidelines recommend not routinely using corticosteroids in all patients with CAP.36 Other adjunctive methods have not been found to have significant impact.6

Prevention of Pneumonia

Prevention of pneumococcal pneumonia involves vaccinations to prevent infection caused by S. pneumoniae and influenza viruses. As influenza is a risk factor for bacterial infection, specifically with S. pneumoniae, influenza vaccination can help prevent bacterial pneumonia.37 In their most recent recommendations, the CDC continues to recommend routine influenza vaccination for all persons older than age 6 months, unless otherwise contraindicated.38

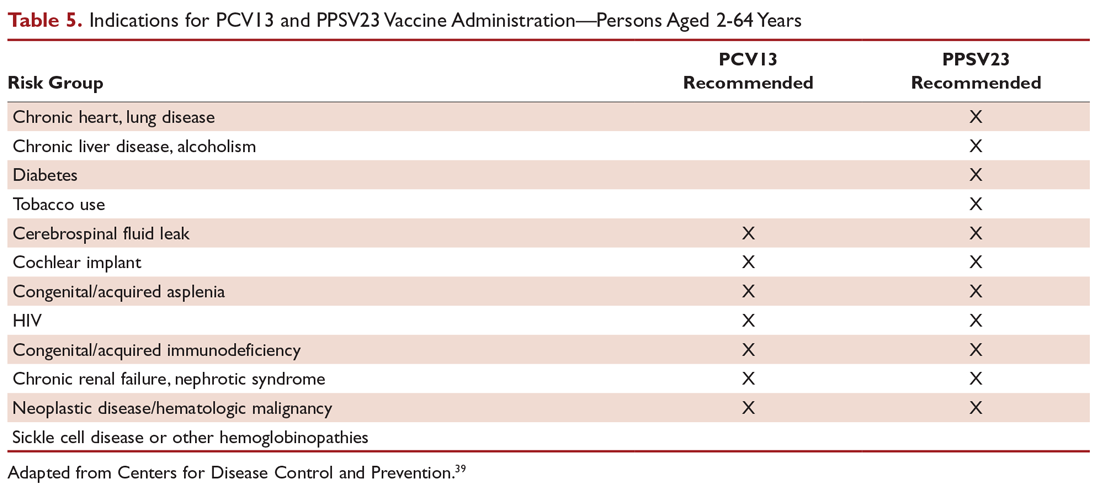

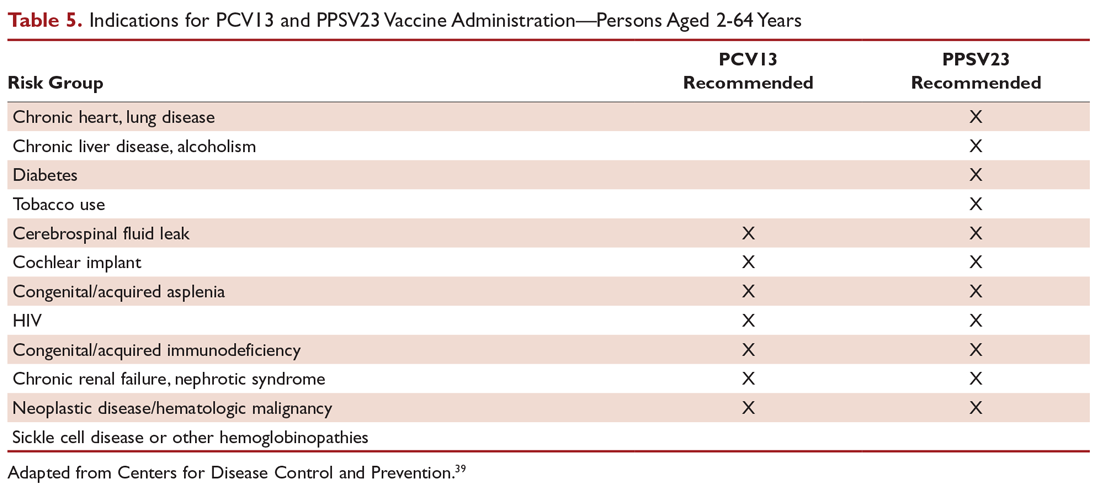

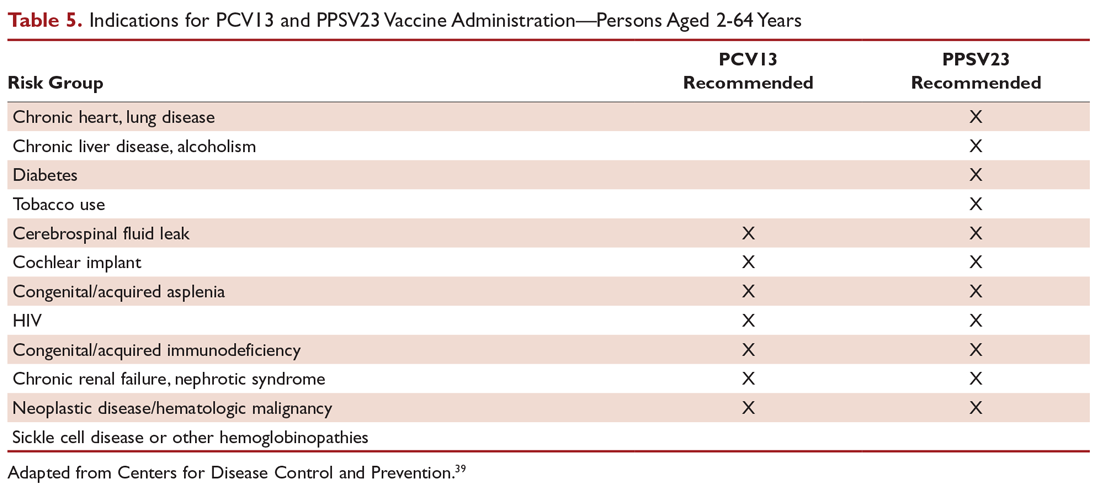

There are 2 vaccines for prevention of pneumococcal disease: the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) and a conjugate vaccine (PCV13). Following vaccination with PPSV23, 80% of adults develop antibodies against at least 18 of the 23 serotypes.39 PPSV23 is reported to be protective against invasive pneumococcal infection, although there is no consensus regarding whether PPSV23 leads to decreased rates of pneumonia.40 On the other hand, PCV13 vaccination was associated with prevention of both invasive disease and CAP in adults aged 65 years or older.41 The CDC recommends that all children aged 2 years or younger receive PCV13, and those aged 65 or older receive PCV13 followed by a dose of PPSV23.42,43 The dose of PPSV23 should be given at least 1 year after the dose of PCV13 is administered.44 Persons younger than 65 years with immunocompromising and certain other conditions should also receive vaccination (Table 5).44 Full recommendations, many scenarios, and details on timing of vaccinations can be found at the CDC’s website.

Cigarette smoking increases the risk of respiratory infections, as evidenced by smokers accounting for almost half of all patients with invasive pneumococcal disease.11 As this is a modifiable risk factor, smoking cessation should be part of a comprehensive approach toward prevention of pneumonia.

Summary

Most patients with CAP are treated empirically with antibiotics, with therapy selection based on the site of care, likely pathogen, and antimicrobial resistance issues. Those treated as outpatients usually respond well to empiric antibiotic treatment, and a causative pathogen is not usually sought. Patients who are hospitalized for treatment usually receive empiric antibiotic on admission, and antimicrobial therapy is adjusted accordingly once the etiology has been determined by microbiologic or serologic means. At this time, the use of corticosteroid as an adjunctive treatment for CAP is still controversial, so not all patients with CAP should routinely receive corticosteroids. Because vaccination (PPSV23, PCV13, and influenza vaccine) remains the most effective tool in preventing the development of CAP, clinicians should strive for 100% vaccination rates in persons without contraindications.

1. Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM, et al A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med.1997;336:243-250.

2. Lim WS, van der Eerden MM, Laing R, et al. Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on presentation to hospital: an international derivation and validation study. Thorax. 2003;58:377-382.

3. Aujesky D, Auble TE, Yealy DM, et al. Prospective comparison of three validated prediction rules for prognosis in community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Med. 2005;118:384-392.

4. Arnold FW, Ramirez JA, McDonald LC, Xia EL. Hospitalization for community-acquired pneumonia: the pneumonia severity index vs clinical judgment. Chest. 2003;124:121-124.

5. Aujesky D, McCausland JB, Whittle J, et al. Reasons why emergency department providers do not rely on the pneumonia severity index to determine the initial site of treatment for patients with pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:e100-108.

6. Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44 Suppl 2:S27-72.

7. Charles PG, Wolfe R, Whitby M, et al. SMART-COP: a tool for predicting the need for intensive respiratory or vasopressor support in community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:375-384.

8. Marti C, Garin N, Grosgurin O, et al. Prediction of severe community-acquired pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2012;16:R141.

9. Jain S, Self WH, Wunderink RG, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:415-427.

10. Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, et al. Management of adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia: 2016 Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:e61-e111.

11. Wunderink RG, Niederman MS, Kollef MH, et al. Linezolid in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nosocomial pneumonia: a randomized, controlled study. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:621-629.

12. Silverman JA, Mortin LI, Vanpraagh AD, et al. Inhibition of daptomycin by pulmonary surfactant: in vitro modeling and clinical impact. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:2149-2152.

13. El Hajj MS, Turgeon RD, Wilby KJ. Ceftaroline fosamil for community-acquired pneumonia and skin and skin structure infections: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pharm. 2017;39:26-32.

14. Taboada M, Melnick D, Iaconis JP, et al. Ceftaroline fosamil versus ceftriaxone for the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia: individual patient data meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71:862-870.

15. Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children: executive summary. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:285-292.

16. Janoff EM. Streptococcus pneumonia. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, editors. Mandell, Douglas and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Sauders; 2015:2310-2327.

17. Teflaro (ceftaroline fosamil) [package insert]. St. Louis, MO: Forest Pharmaceuticals; 2010.

18. Nuzyra (omadacycline) [package insert]. Boston, MA: Paratek Pharmaceuticals; 2018.

19. Xenleta (lefamulin) [package insert]. Dublin, Ireland: Nabriva Therapeutics; 2019.

20. Baddour LM, Yu VL, Klugman KP, et al. Combination antibiotic therapy lowers mortality among severely ill patients with pneumococcal bacteremia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:440-444.

21. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA warns of increased risk of death with IV antibacterial Tygacil (tigecycline) and approves new boxed warning. www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm369580.htm. Accessed 16 September 2019.

22. Edelstein PR, CR. Legionnaires’ disease and Pontiac fever. In: Kasper DF, editor. Harrison’s Infectious Diseases. 1st ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2010:2633.

23. Hammerschlag MR, Kohlhoff SA, Gaydos, CA. Chlamydia pneumoniae. In: Kasper DF, editor. Harrison’s Infectious Diseases. 1st ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2010:2174.

24. Holzman RS, MS. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and atypical pneumonia. In: Kasper DF, editor. Harrison’s Infectious Diseases. 1st ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2010:2183.

25. Yamada M, Buller R, Bledsoe S, Storch GA. Rising rates of macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae in the central United States. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31:409-410.

26. Yi SH, Hatfield KM, Baggs J, et al. Duration of antibiotic use among adults with uncomplicated community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66:1333-1341.

27. Hayashi Y, Paterson DL. Strategies for reduction in duration of antibiotic use in hospitalized patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:1232-1240.

28. Akram AR, Chalmers JD, Taylor JK, et al. An evaluation of clinical stability criteria to predict hospital course in community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19:1174-1180.

29. Halm EA, Fine MJ, Kapoor WN, et al. Instability on hospital discharge and the risk of adverse outcomes in patients with pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1278-1284.

30. Janoff EM. Streptococcus pneumonia. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, editors. Mandell, Douglas and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2015:2310-2327.

31. Roson B, Carratala J, Fernandez-Sabe N, et al. Causes and factors associated with early failure in hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:502-508.

32. El-Solh AA, Pietrantoni C, Bhat A, et al. Microbiology of severe aspiration pneumonia in institutionalized elderly. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:1650-1654.

33. Wan YD, Sun TW, Liu ZQ, et al. Efficacy and safety of corticosteroids for community-acquired pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2016;149:209-219.

34. Torres A, Sibila O, Ferrer M, et al. Effect of corticosteroids on treatment failure among hospitalized patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia and high inflammatory response: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313:677-686.

35. Lloyd M, Karahalios, Janus E, et al. Effectiveness of a bundled intervention including adjunctive corticosteroids on outcomes of hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia: a stepped-wedge randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:1052-1060.

36. Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. An official Clinical Practice Guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200:e45-e67.

37. McCullers JA. Insights into the interaction between influenza virus and pneumococcus. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:571-582.

38. Grohskopf LA, Alyanak E, Broder KR, et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices - United States, 2019-20 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2019;68:1-21.

39. Rubins JB, Alter M, Loch J, Janoff EN. Determination of antibody responses of elderly adults to all 23 capsular polysaccharides after pneumococcal vaccination. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5979-5984.

40. Vaccines and preventable diseases. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/pneumo/hcp/about-vaccine.html. Accessed 16 September 2019.

41. Bonten MJ, Huijts SM, Bolkenbaas M, et al. Polysaccharide conjugate vaccine against pneumococcal pneumonia in adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1114-1125.

42. Recommended adult immunization schedule -- United States -- 2019. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/downloads/adult/adult-combined-schedule.pdf. Accessed 16 September 2019.

43. Recommended child and adolescent immunization schedule for ages 18 years or younger – United States – 2019. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/imz/child-adolescent.html. Accessed 22 September 2019.

44. Pneumococcal vaccine timing for adults – United States – 2019. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/pneumo/downloads/pneumo-vaccine-timing.pdf. Accessed 22 September 2019.

Initial management decisions for patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) will depend on severity of infection, with need for hospitalization being one of the first decisions. Because empiric antibiotics are the mainstay of treatment and the causative organisms are seldom identified, underlying medical conditions and epidemiologic risk factors are considered when selecting an empiric regimen. As with other infections, duration of therapy is not standardized, but rather is guided by clinical improvement. Prevention of pneumonia centers around vaccination and smoking cessation. This article, the second in a 2-part review of CAP in adults, focuses on site of care decision, empiric and directed therapies, length of treatment, and prevention strategies. Evaluation and diagnosis of CAP are discussed in a separate article.

Site of Care Decision

For patients diagnosed with CAP, the clinician must decide whether treatment will be done in an outpatient or inpatient setting, and for those in the inpatient setting, whether they can safely be treated on the general medical ward or in the intensive care unit (ICU). Two common scoring systems that can be used to aid the clinician in determining severity of the infection and guide site-of-care decisions are the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) and CURB-65 scores.

The PSI score uses 20 different parameters, including comorbidities, laboratory parameters, and radiographic findings, to stratify patients into 5 mortality risk classes.1 On the basis of associated mortality rates, it has been suggested that risk class I and II patients should be treated as outpatients, risk class III patients should be treated in an observation unit or with a short hospitalization, and risk class IV and V patients should be treated as inpatients.1

The CURB-65 method of risk stratification is based on 5 clinical parameters: confusion, urea level, respiratory rate, systolic blood pressure, and age ≥ 65 years (Table 1).2,3 A modification to the CURB-65 algorithm tool was CRB-65, which excludes urea nitrogen, making it optimal for making determinations in a clinic-based setting. It should be emphasized that these tools do not take into account other factors that should be used in determining location of treatment, such as stable home, mental illness, or concerns about compliance with medications. In many instances, it is these factors that preclude low-risk patients from being treated as outpatients.4,5 Similarly, these scoring systems have not been validated for immunocompromised patients or those who would qualify as having health care–associated pneumonia.

Patients with CURB-65 scores of 4 or 5 are considered to have severe pneumonia, and admission to the ICU should be considered for these patients. Aside from the CURB-65 score, anyone requiring vasopressor support or mechanical ventilation merits admission to the ICU.6 American Thoracic Society (ATS) and Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines also recommend the use of “minor criteria” for making ICU admission decisions; these include respiratory rate ≥ 30 breaths/minute, PaO2 fraction ≤ 250 mm Hg, multilobar infiltrates, confusion, blood urea nitrogen ≥ 20 mg/dL, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, hypothermia, and hypotension.6 These factors are associated with increased mortality due to CAP, and ICU admission is indicated if 3 of the minor criteria for severe CAP are present.

Another clinical calculator that can be used for assessing severity of CAP is SMART-COP (systolic blood pressure, multilobar chest radiography involvement, albumin level, respiratory rate, tachycardia, confusion, oxygenation and arterial pH).7 This scoring system uses 8 weighted criteria to predict which patients will require intensive respiratory or vasopressor support. SMART-COP has a sensitivity of 79% and a specificity of 64% in predicting ICU admission, whereas CURB-65 has a pooled sensitivity of 57.2% and specificity of 77.2%.8

Antibiotic Therapy

Antibiotics are the mainstay of treatment for CAP, with the majority of patients with CAP treated empirically taking into account the site of care, likely pathogen, and antimicrobial resistance issues. Patients with pneumonia who are treated as outpatients usually respond well to empiric antibiotic treatment, and a causative pathogen is not usually sought. Patients who are hospitalized for treatment of CAP usually receive empiric antibiotic on admission. Once the etiology has been determined by microbiologic or serologic means, antimicrobial therapy should be adjusted accordingly. A CDC study found that the burden of viral etiologies was higher than previously thought, with rhinovirus and influenza accounting for 15% of cases and Streptococcus pneumoniae for only 5%.9 This study highlighted the fact that despite advances in molecular techniques, no pathogen is identified for most patients with pneumonia.9 Given the lack of discernable pathogens in the majority of cases, patients should continue to be treated with antibiotics unless a nonbacterial etiology is found.

Outpatients without comorbidities or risk factors for drug-resistant S. pneumoniae (Table 2)10 can be treated with monotherapy. Hospitalized patients are usually treated with combination intravenous therapy, although non-ICU patients who receive a respiratory fluoroquinolone can be treated orally.

As previously mentioned, antibiotic therapy is typically empiric, since neither clinical features nor radiographic features are sufficient to include or exclude infectious etiologies. Epidemiologic risk factors should be considered and, in certain cases, antimicrobial coverage should be expanded to include those entities; for example, treatment of anaerobes in the setting of lung abscess and antipseudomonal antibiotics for patients with bronchiectasis.

Of concern in the treatment of CAP is the increased prevalence of antimicrobial resistance among S. pneumoniae. The IDSA guidelines report that drug-resistant S. pneumoniae is more common in persons aged < 2 or > 65 years, and those with β-lactam therapy within the previous 3 months, alcoholism, medical comorbidities, immunosuppressive illness or therapy, or exposure to a child who attends a day care center.6

Staphylococcus aureus should be considered during influenza outbreaks, with either vancomycin or linezolid being the recommended agents in the setting of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA). In a study comparing vancomycin versus linezolid for nosocomial pneumonia, the all-cause 60-day mortality was similar for both agents.11 Daptomycin, another agent used against MRSA, is not indicated in the setting of pneumonia because daptomycin binds to surfactant, yielding it ineffective in the treatment of pneumonia.12 Ceftaroline is a newer cephalosporin with activity against MRSA; its role in treatment of community-acquired MRSA pneumonia has not been fully elucidated, but it appears to be a useful agent for this indication.13,14 Similarly, other agents known to have antibacterial properties against MRSA, such as trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and doxycycline, have not been studied for this indication. Clindamycin has been used to treat MRSA in children, and IDSA guidelines on the treatment of MRSA list clindamycin as an alternative15 if MRSA is known to be sensitive.

A summary of recommended empiric antibiotic therapy is presented in Table 3.16

Three antibiotics were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of CAP after the release of the IDSA/ATS guidelines in 2007. Ceftaroline fosamil is a fifth-generation cephalosporin that has coverage for MRSA and was approved in November 2010.17 It can only be administered intravenously and needs dose adjustment for renal function. Omadacycline is a new tetracycline that was approved by the FDA in October 2018.18 It is available in both intravenous injectable and oral forms. No dose adjustment is needed for renal function. Lefamulin is a first-in-class novel pleuromutilin antibiotic which was FDA-approved in August 2019. It can be administered intravenously or orally, with no dosage adjustment necessary in patients with renal impairment.19

Antibiotic Therapy for Selected Pathogens

Streptococcus pneumoniae

Patients with pneumococcal pneumonia who have penicillin-susceptible strains can be treated with intravenous penicillin (2 or 3 million units every 4 hours) or ceftriaxone. Once a patient meets criteria of stability, they can then be transitioned to oral penicillin, amoxicillin, or clarithromycin. Those with strains with reduced susceptibility can still be treated with penicillin, but at a higher dose (4 million units intravenously [IV] every 4 hours), or a third-generation cephalosporin. Those whose pneumococcal pneumonia is complicated by bacteremia will benefit from dual therapy if severely ill, requiring ICU monitoring. Those not severely ill can be treated with monotherapy.20

Staphylococcus aureus

Staphylococcus aureus is more commonly associated with hospital-acquired pneumonia, but it may also be seen during the influenza season and in those with severe necrotizing CAP. Both linezolid and vancomycin can be used to treat MRSA CAP. As noted, ceftaroline has activity against MRSA and is approved for treatment of CAP, but is not approved by the FDA for MRSA CAP treatment. Similarly, tigecycline is approved for CAP and has activity against MRSA, but is not approved for MRSA CAP. Moreover, the FDA has warned of increased risk of death with tigecycline and has a black box warning to that effect.21

Legionella

Legionellosis can be treated with tetra¬cyclines, macrolides, or fluoroquinolones. For non-immunocompromised patients with mild pneumonia, any of the listed antibiotics is considered appropriate. However, patients with severe infection or those with immunosuppression should be treated with either levofloxacin or azithromycin for 7 to 10 days.22

Chlamydophila pneumoniae

As with other atypical organisms, Chlamydophila pneumoniae can be treated with doxycycline, a macrolide, or respiratory fluoroquinolones. However, length of therapy varies by regimen used; treating with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily generally requires 14 to 21 days, whereas moxifloxacin 400 mg daily requires 10 days.23

Mycoplasma pneumoniae

As with C. pneumoniae, length of therapy of Mycoplasma pneumoniae varies by which antimicrobial regimen is used. Shortest courses are seen with the use of macrolides for 5 days, whereas 14 days is considered standard for doxycycline or a respiratory fluoroquinolone.24 It should be noted that there has been increasingly documented resistance to macrolides, with known resistance of 8.2% in the United States.25

Duration of Treatment

Most patients with CAP respond to appropriate therapy within 72 hours. IDSA/ATS guidelines recommend that patients with routine cases of CAP be treated for a minimum of 5 days. Despite this, many patients are treated for an excessive amount of time, with over 70% of patients reported to have received antibiotics for more than 10 days for uncomplicated CAP.26 There are instances that require longer courses of antibiotics, including cases caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, S. aureus, and Legionella species and patients with lung abscesses or necrotizing infections, among others.27

Hospitalized patients do not need to be monitored for an additional day once they have reached clinical stability (Table 4), are able to maintain oral intake, and have normal mentation, provided that other comorbidities are stable and social needs have been met.6 C-reactive protein (CRP) level has been postulated as an additional measure of stability, specifically monitoring for a greater than 50% reduction in CRP; however, this was validated only for those with complicated pneumonia.28 Patients discharged from the hospital with instability have higher risk of readmission or death.29

Transition to Oral Therapy

IDSA/ATS guidelines6 recommend that patients should be transitioned from intravenous to oral antibiotics when they are improving clinically, have stable vital signs, and are able to ingest food/fluids and medications.

Management of Nonresponders

Although the majority of patients respond to antibiotics within 72 hours, treatment failure occurs in up to 15% of patients.15 Nonresponding pneumonia is generally seen in 2 patterns: worsening of clinical status despite empiric antibiotics or delay in achieving clinical stability, as defined in Table 4, after 72 hours of treatment.30 Risk factors associated with nonresponding pneumonia31 are:

- Radiographic: multilobar infiltrates, pleural effusion, cavitation

- Bacteriologic: MRSA, gram-negative or Legionella pneumonia

- Severity index: PSI > 90

- Pharmacologic: incorrect antibiotic choice based on susceptibility

Patients with acute deterioration of clinical status require prompt transfer to a higher level of care and may require mechanical ventilator support. In those with delay in achieving clinical stability, a question centers on whether the same antibiotics can be continued while doing further radiographic/microbiologic work-up and/or changing antibiotics. History should be reviewed, with particular attention to exposures, travel history, and microbiologic and radiographic data. Clinicians should recall that viruses account for up to 20% of pneumonias and that there are also noninfectious causes that can mimic pyogenic infections.32 If adequate initial cultures were not obtained, they should be obtained; however, care must be taken in reviewing new sets of cultures while on antibiotics, as they may reveal colonization selected out by antibiotics and not a true pathogen. If repeat evaluation is unrevealing, then further evaluation with computed tomography (CT) scan and bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage and biopsy is warranted. CT scans can show pleural effusions, bronchial obstructions, or a pattern suggestive of cryptogenic pneumonia. A bronchoscopy might yield a microbiologic diagnosis and, when combined with biopsy, can also evaluate for noninfectious causes.

As with other infections, if escalation of antibiotics is undertaken, clinicians should try to determine the reason for nonresponse. To simply broaden antimicrobial therapy without attempts at establishing a microbiologic or radiographic cause for nonresponse may lead to inappropriate treatment and recurrence of infection. Aside from patients who have bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia in an ICU setting, there are no published reports pointing to superiority of combination antibiotics.20

Other Treatment

Several agents have been evaluated as adjunctive treatment of pneumonia to decrease the inflammatory response associated with pneumonia; namely, steroids, macrolide antibiotics, and statins. To date, only the use of steroids (methylprednisolone 0.5 mg/kg every 12 hours for 5 days) in those with severe CAP and high initial anti-inflammatory response (CRP > 150) has been shown to decrease treatment failure, decrease risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome, and possibly reduce length of stay and duration of intravenous antibiotics, without effect on mortality or adverse side effects.33,34 However, a recent double-blind randomized study conducted in Australia in which patients admitted with CAP were prescribed prednisolone acetate (50 mg/day for 7 days) and de-escalated from parenteral to oral antibiotics according to standardized criteria revealed no difference in mortality, length of stay, or readmission rates between the corticosteroids group and the control group at 90-day follow-up.35 At this point, corticosteroid as an adjunctive treatment for CAP is still controversial and the new 2019 ATS/IDSA guidelines recommend not routinely using corticosteroids in all patients with CAP.36 Other adjunctive methods have not been found to have significant impact.6

Prevention of Pneumonia

Prevention of pneumococcal pneumonia involves vaccinations to prevent infection caused by S. pneumoniae and influenza viruses. As influenza is a risk factor for bacterial infection, specifically with S. pneumoniae, influenza vaccination can help prevent bacterial pneumonia.37 In their most recent recommendations, the CDC continues to recommend routine influenza vaccination for all persons older than age 6 months, unless otherwise contraindicated.38

There are 2 vaccines for prevention of pneumococcal disease: the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) and a conjugate vaccine (PCV13). Following vaccination with PPSV23, 80% of adults develop antibodies against at least 18 of the 23 serotypes.39 PPSV23 is reported to be protective against invasive pneumococcal infection, although there is no consensus regarding whether PPSV23 leads to decreased rates of pneumonia.40 On the other hand, PCV13 vaccination was associated with prevention of both invasive disease and CAP in adults aged 65 years or older.41 The CDC recommends that all children aged 2 years or younger receive PCV13, and those aged 65 or older receive PCV13 followed by a dose of PPSV23.42,43 The dose of PPSV23 should be given at least 1 year after the dose of PCV13 is administered.44 Persons younger than 65 years with immunocompromising and certain other conditions should also receive vaccination (Table 5).44 Full recommendations, many scenarios, and details on timing of vaccinations can be found at the CDC’s website.

Cigarette smoking increases the risk of respiratory infections, as evidenced by smokers accounting for almost half of all patients with invasive pneumococcal disease.11 As this is a modifiable risk factor, smoking cessation should be part of a comprehensive approach toward prevention of pneumonia.

Summary

Most patients with CAP are treated empirically with antibiotics, with therapy selection based on the site of care, likely pathogen, and antimicrobial resistance issues. Those treated as outpatients usually respond well to empiric antibiotic treatment, and a causative pathogen is not usually sought. Patients who are hospitalized for treatment usually receive empiric antibiotic on admission, and antimicrobial therapy is adjusted accordingly once the etiology has been determined by microbiologic or serologic means. At this time, the use of corticosteroid as an adjunctive treatment for CAP is still controversial, so not all patients with CAP should routinely receive corticosteroids. Because vaccination (PPSV23, PCV13, and influenza vaccine) remains the most effective tool in preventing the development of CAP, clinicians should strive for 100% vaccination rates in persons without contraindications.

Initial management decisions for patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) will depend on severity of infection, with need for hospitalization being one of the first decisions. Because empiric antibiotics are the mainstay of treatment and the causative organisms are seldom identified, underlying medical conditions and epidemiologic risk factors are considered when selecting an empiric regimen. As with other infections, duration of therapy is not standardized, but rather is guided by clinical improvement. Prevention of pneumonia centers around vaccination and smoking cessation. This article, the second in a 2-part review of CAP in adults, focuses on site of care decision, empiric and directed therapies, length of treatment, and prevention strategies. Evaluation and diagnosis of CAP are discussed in a separate article.

Site of Care Decision

For patients diagnosed with CAP, the clinician must decide whether treatment will be done in an outpatient or inpatient setting, and for those in the inpatient setting, whether they can safely be treated on the general medical ward or in the intensive care unit (ICU). Two common scoring systems that can be used to aid the clinician in determining severity of the infection and guide site-of-care decisions are the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) and CURB-65 scores.

The PSI score uses 20 different parameters, including comorbidities, laboratory parameters, and radiographic findings, to stratify patients into 5 mortality risk classes.1 On the basis of associated mortality rates, it has been suggested that risk class I and II patients should be treated as outpatients, risk class III patients should be treated in an observation unit or with a short hospitalization, and risk class IV and V patients should be treated as inpatients.1

The CURB-65 method of risk stratification is based on 5 clinical parameters: confusion, urea level, respiratory rate, systolic blood pressure, and age ≥ 65 years (Table 1).2,3 A modification to the CURB-65 algorithm tool was CRB-65, which excludes urea nitrogen, making it optimal for making determinations in a clinic-based setting. It should be emphasized that these tools do not take into account other factors that should be used in determining location of treatment, such as stable home, mental illness, or concerns about compliance with medications. In many instances, it is these factors that preclude low-risk patients from being treated as outpatients.4,5 Similarly, these scoring systems have not been validated for immunocompromised patients or those who would qualify as having health care–associated pneumonia.

Patients with CURB-65 scores of 4 or 5 are considered to have severe pneumonia, and admission to the ICU should be considered for these patients. Aside from the CURB-65 score, anyone requiring vasopressor support or mechanical ventilation merits admission to the ICU.6 American Thoracic Society (ATS) and Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines also recommend the use of “minor criteria” for making ICU admission decisions; these include respiratory rate ≥ 30 breaths/minute, PaO2 fraction ≤ 250 mm Hg, multilobar infiltrates, confusion, blood urea nitrogen ≥ 20 mg/dL, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, hypothermia, and hypotension.6 These factors are associated with increased mortality due to CAP, and ICU admission is indicated if 3 of the minor criteria for severe CAP are present.

Another clinical calculator that can be used for assessing severity of CAP is SMART-COP (systolic blood pressure, multilobar chest radiography involvement, albumin level, respiratory rate, tachycardia, confusion, oxygenation and arterial pH).7 This scoring system uses 8 weighted criteria to predict which patients will require intensive respiratory or vasopressor support. SMART-COP has a sensitivity of 79% and a specificity of 64% in predicting ICU admission, whereas CURB-65 has a pooled sensitivity of 57.2% and specificity of 77.2%.8

Antibiotic Therapy

Antibiotics are the mainstay of treatment for CAP, with the majority of patients with CAP treated empirically taking into account the site of care, likely pathogen, and antimicrobial resistance issues. Patients with pneumonia who are treated as outpatients usually respond well to empiric antibiotic treatment, and a causative pathogen is not usually sought. Patients who are hospitalized for treatment of CAP usually receive empiric antibiotic on admission. Once the etiology has been determined by microbiologic or serologic means, antimicrobial therapy should be adjusted accordingly. A CDC study found that the burden of viral etiologies was higher than previously thought, with rhinovirus and influenza accounting for 15% of cases and Streptococcus pneumoniae for only 5%.9 This study highlighted the fact that despite advances in molecular techniques, no pathogen is identified for most patients with pneumonia.9 Given the lack of discernable pathogens in the majority of cases, patients should continue to be treated with antibiotics unless a nonbacterial etiology is found.

Outpatients without comorbidities or risk factors for drug-resistant S. pneumoniae (Table 2)10 can be treated with monotherapy. Hospitalized patients are usually treated with combination intravenous therapy, although non-ICU patients who receive a respiratory fluoroquinolone can be treated orally.

As previously mentioned, antibiotic therapy is typically empiric, since neither clinical features nor radiographic features are sufficient to include or exclude infectious etiologies. Epidemiologic risk factors should be considered and, in certain cases, antimicrobial coverage should be expanded to include those entities; for example, treatment of anaerobes in the setting of lung abscess and antipseudomonal antibiotics for patients with bronchiectasis.

Of concern in the treatment of CAP is the increased prevalence of antimicrobial resistance among S. pneumoniae. The IDSA guidelines report that drug-resistant S. pneumoniae is more common in persons aged < 2 or > 65 years, and those with β-lactam therapy within the previous 3 months, alcoholism, medical comorbidities, immunosuppressive illness or therapy, or exposure to a child who attends a day care center.6

Staphylococcus aureus should be considered during influenza outbreaks, with either vancomycin or linezolid being the recommended agents in the setting of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA). In a study comparing vancomycin versus linezolid for nosocomial pneumonia, the all-cause 60-day mortality was similar for both agents.11 Daptomycin, another agent used against MRSA, is not indicated in the setting of pneumonia because daptomycin binds to surfactant, yielding it ineffective in the treatment of pneumonia.12 Ceftaroline is a newer cephalosporin with activity against MRSA; its role in treatment of community-acquired MRSA pneumonia has not been fully elucidated, but it appears to be a useful agent for this indication.13,14 Similarly, other agents known to have antibacterial properties against MRSA, such as trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and doxycycline, have not been studied for this indication. Clindamycin has been used to treat MRSA in children, and IDSA guidelines on the treatment of MRSA list clindamycin as an alternative15 if MRSA is known to be sensitive.

A summary of recommended empiric antibiotic therapy is presented in Table 3.16

Three antibiotics were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of CAP after the release of the IDSA/ATS guidelines in 2007. Ceftaroline fosamil is a fifth-generation cephalosporin that has coverage for MRSA and was approved in November 2010.17 It can only be administered intravenously and needs dose adjustment for renal function. Omadacycline is a new tetracycline that was approved by the FDA in October 2018.18 It is available in both intravenous injectable and oral forms. No dose adjustment is needed for renal function. Lefamulin is a first-in-class novel pleuromutilin antibiotic which was FDA-approved in August 2019. It can be administered intravenously or orally, with no dosage adjustment necessary in patients with renal impairment.19

Antibiotic Therapy for Selected Pathogens

Streptococcus pneumoniae

Patients with pneumococcal pneumonia who have penicillin-susceptible strains can be treated with intravenous penicillin (2 or 3 million units every 4 hours) or ceftriaxone. Once a patient meets criteria of stability, they can then be transitioned to oral penicillin, amoxicillin, or clarithromycin. Those with strains with reduced susceptibility can still be treated with penicillin, but at a higher dose (4 million units intravenously [IV] every 4 hours), or a third-generation cephalosporin. Those whose pneumococcal pneumonia is complicated by bacteremia will benefit from dual therapy if severely ill, requiring ICU monitoring. Those not severely ill can be treated with monotherapy.20

Staphylococcus aureus

Staphylococcus aureus is more commonly associated with hospital-acquired pneumonia, but it may also be seen during the influenza season and in those with severe necrotizing CAP. Both linezolid and vancomycin can be used to treat MRSA CAP. As noted, ceftaroline has activity against MRSA and is approved for treatment of CAP, but is not approved by the FDA for MRSA CAP treatment. Similarly, tigecycline is approved for CAP and has activity against MRSA, but is not approved for MRSA CAP. Moreover, the FDA has warned of increased risk of death with tigecycline and has a black box warning to that effect.21

Legionella

Legionellosis can be treated with tetra¬cyclines, macrolides, or fluoroquinolones. For non-immunocompromised patients with mild pneumonia, any of the listed antibiotics is considered appropriate. However, patients with severe infection or those with immunosuppression should be treated with either levofloxacin or azithromycin for 7 to 10 days.22

Chlamydophila pneumoniae

As with other atypical organisms, Chlamydophila pneumoniae can be treated with doxycycline, a macrolide, or respiratory fluoroquinolones. However, length of therapy varies by regimen used; treating with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily generally requires 14 to 21 days, whereas moxifloxacin 400 mg daily requires 10 days.23

Mycoplasma pneumoniae

As with C. pneumoniae, length of therapy of Mycoplasma pneumoniae varies by which antimicrobial regimen is used. Shortest courses are seen with the use of macrolides for 5 days, whereas 14 days is considered standard for doxycycline or a respiratory fluoroquinolone.24 It should be noted that there has been increasingly documented resistance to macrolides, with known resistance of 8.2% in the United States.25

Duration of Treatment

Most patients with CAP respond to appropriate therapy within 72 hours. IDSA/ATS guidelines recommend that patients with routine cases of CAP be treated for a minimum of 5 days. Despite this, many patients are treated for an excessive amount of time, with over 70% of patients reported to have received antibiotics for more than 10 days for uncomplicated CAP.26 There are instances that require longer courses of antibiotics, including cases caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, S. aureus, and Legionella species and patients with lung abscesses or necrotizing infections, among others.27

Hospitalized patients do not need to be monitored for an additional day once they have reached clinical stability (Table 4), are able to maintain oral intake, and have normal mentation, provided that other comorbidities are stable and social needs have been met.6 C-reactive protein (CRP) level has been postulated as an additional measure of stability, specifically monitoring for a greater than 50% reduction in CRP; however, this was validated only for those with complicated pneumonia.28 Patients discharged from the hospital with instability have higher risk of readmission or death.29

Transition to Oral Therapy

IDSA/ATS guidelines6 recommend that patients should be transitioned from intravenous to oral antibiotics when they are improving clinically, have stable vital signs, and are able to ingest food/fluids and medications.

Management of Nonresponders

Although the majority of patients respond to antibiotics within 72 hours, treatment failure occurs in up to 15% of patients.15 Nonresponding pneumonia is generally seen in 2 patterns: worsening of clinical status despite empiric antibiotics or delay in achieving clinical stability, as defined in Table 4, after 72 hours of treatment.30 Risk factors associated with nonresponding pneumonia31 are:

- Radiographic: multilobar infiltrates, pleural effusion, cavitation

- Bacteriologic: MRSA, gram-negative or Legionella pneumonia

- Severity index: PSI > 90

- Pharmacologic: incorrect antibiotic choice based on susceptibility

Patients with acute deterioration of clinical status require prompt transfer to a higher level of care and may require mechanical ventilator support. In those with delay in achieving clinical stability, a question centers on whether the same antibiotics can be continued while doing further radiographic/microbiologic work-up and/or changing antibiotics. History should be reviewed, with particular attention to exposures, travel history, and microbiologic and radiographic data. Clinicians should recall that viruses account for up to 20% of pneumonias and that there are also noninfectious causes that can mimic pyogenic infections.32 If adequate initial cultures were not obtained, they should be obtained; however, care must be taken in reviewing new sets of cultures while on antibiotics, as they may reveal colonization selected out by antibiotics and not a true pathogen. If repeat evaluation is unrevealing, then further evaluation with computed tomography (CT) scan and bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage and biopsy is warranted. CT scans can show pleural effusions, bronchial obstructions, or a pattern suggestive of cryptogenic pneumonia. A bronchoscopy might yield a microbiologic diagnosis and, when combined with biopsy, can also evaluate for noninfectious causes.

As with other infections, if escalation of antibiotics is undertaken, clinicians should try to determine the reason for nonresponse. To simply broaden antimicrobial therapy without attempts at establishing a microbiologic or radiographic cause for nonresponse may lead to inappropriate treatment and recurrence of infection. Aside from patients who have bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia in an ICU setting, there are no published reports pointing to superiority of combination antibiotics.20

Other Treatment

Several agents have been evaluated as adjunctive treatment of pneumonia to decrease the inflammatory response associated with pneumonia; namely, steroids, macrolide antibiotics, and statins. To date, only the use of steroids (methylprednisolone 0.5 mg/kg every 12 hours for 5 days) in those with severe CAP and high initial anti-inflammatory response (CRP > 150) has been shown to decrease treatment failure, decrease risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome, and possibly reduce length of stay and duration of intravenous antibiotics, without effect on mortality or adverse side effects.33,34 However, a recent double-blind randomized study conducted in Australia in which patients admitted with CAP were prescribed prednisolone acetate (50 mg/day for 7 days) and de-escalated from parenteral to oral antibiotics according to standardized criteria revealed no difference in mortality, length of stay, or readmission rates between the corticosteroids group and the control group at 90-day follow-up.35 At this point, corticosteroid as an adjunctive treatment for CAP is still controversial and the new 2019 ATS/IDSA guidelines recommend not routinely using corticosteroids in all patients with CAP.36 Other adjunctive methods have not been found to have significant impact.6

Prevention of Pneumonia

Prevention of pneumococcal pneumonia involves vaccinations to prevent infection caused by S. pneumoniae and influenza viruses. As influenza is a risk factor for bacterial infection, specifically with S. pneumoniae, influenza vaccination can help prevent bacterial pneumonia.37 In their most recent recommendations, the CDC continues to recommend routine influenza vaccination for all persons older than age 6 months, unless otherwise contraindicated.38

There are 2 vaccines for prevention of pneumococcal disease: the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) and a conjugate vaccine (PCV13). Following vaccination with PPSV23, 80% of adults develop antibodies against at least 18 of the 23 serotypes.39 PPSV23 is reported to be protective against invasive pneumococcal infection, although there is no consensus regarding whether PPSV23 leads to decreased rates of pneumonia.40 On the other hand, PCV13 vaccination was associated with prevention of both invasive disease and CAP in adults aged 65 years or older.41 The CDC recommends that all children aged 2 years or younger receive PCV13, and those aged 65 or older receive PCV13 followed by a dose of PPSV23.42,43 The dose of PPSV23 should be given at least 1 year after the dose of PCV13 is administered.44 Persons younger than 65 years with immunocompromising and certain other conditions should also receive vaccination (Table 5).44 Full recommendations, many scenarios, and details on timing of vaccinations can be found at the CDC’s website.

Cigarette smoking increases the risk of respiratory infections, as evidenced by smokers accounting for almost half of all patients with invasive pneumococcal disease.11 As this is a modifiable risk factor, smoking cessation should be part of a comprehensive approach toward prevention of pneumonia.

Summary

Most patients with CAP are treated empirically with antibiotics, with therapy selection based on the site of care, likely pathogen, and antimicrobial resistance issues. Those treated as outpatients usually respond well to empiric antibiotic treatment, and a causative pathogen is not usually sought. Patients who are hospitalized for treatment usually receive empiric antibiotic on admission, and antimicrobial therapy is adjusted accordingly once the etiology has been determined by microbiologic or serologic means. At this time, the use of corticosteroid as an adjunctive treatment for CAP is still controversial, so not all patients with CAP should routinely receive corticosteroids. Because vaccination (PPSV23, PCV13, and influenza vaccine) remains the most effective tool in preventing the development of CAP, clinicians should strive for 100% vaccination rates in persons without contraindications.

1. Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM, et al A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med.1997;336:243-250.

2. Lim WS, van der Eerden MM, Laing R, et al. Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on presentation to hospital: an international derivation and validation study. Thorax. 2003;58:377-382.

3. Aujesky D, Auble TE, Yealy DM, et al. Prospective comparison of three validated prediction rules for prognosis in community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Med. 2005;118:384-392.

4. Arnold FW, Ramirez JA, McDonald LC, Xia EL. Hospitalization for community-acquired pneumonia: the pneumonia severity index vs clinical judgment. Chest. 2003;124:121-124.

5. Aujesky D, McCausland JB, Whittle J, et al. Reasons why emergency department providers do not rely on the pneumonia severity index to determine the initial site of treatment for patients with pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:e100-108.

6. Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44 Suppl 2:S27-72.

7. Charles PG, Wolfe R, Whitby M, et al. SMART-COP: a tool for predicting the need for intensive respiratory or vasopressor support in community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:375-384.

8. Marti C, Garin N, Grosgurin O, et al. Prediction of severe community-acquired pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2012;16:R141.

9. Jain S, Self WH, Wunderink RG, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:415-427.

10. Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, et al. Management of adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia: 2016 Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:e61-e111.

11. Wunderink RG, Niederman MS, Kollef MH, et al. Linezolid in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nosocomial pneumonia: a randomized, controlled study. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:621-629.

12. Silverman JA, Mortin LI, Vanpraagh AD, et al. Inhibition of daptomycin by pulmonary surfactant: in vitro modeling and clinical impact. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:2149-2152.

13. El Hajj MS, Turgeon RD, Wilby KJ. Ceftaroline fosamil for community-acquired pneumonia and skin and skin structure infections: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pharm. 2017;39:26-32.

14. Taboada M, Melnick D, Iaconis JP, et al. Ceftaroline fosamil versus ceftriaxone for the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia: individual patient data meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71:862-870.

15. Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children: executive summary. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:285-292.

16. Janoff EM. Streptococcus pneumonia. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, editors. Mandell, Douglas and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Sauders; 2015:2310-2327.

17. Teflaro (ceftaroline fosamil) [package insert]. St. Louis, MO: Forest Pharmaceuticals; 2010.

18. Nuzyra (omadacycline) [package insert]. Boston, MA: Paratek Pharmaceuticals; 2018.

19. Xenleta (lefamulin) [package insert]. Dublin, Ireland: Nabriva Therapeutics; 2019.

20. Baddour LM, Yu VL, Klugman KP, et al. Combination antibiotic therapy lowers mortality among severely ill patients with pneumococcal bacteremia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:440-444.

21. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA warns of increased risk of death with IV antibacterial Tygacil (tigecycline) and approves new boxed warning. www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm369580.htm. Accessed 16 September 2019.

22. Edelstein PR, CR. Legionnaires’ disease and Pontiac fever. In: Kasper DF, editor. Harrison’s Infectious Diseases. 1st ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2010:2633.

23. Hammerschlag MR, Kohlhoff SA, Gaydos, CA. Chlamydia pneumoniae. In: Kasper DF, editor. Harrison’s Infectious Diseases. 1st ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2010:2174.

24. Holzman RS, MS. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and atypical pneumonia. In: Kasper DF, editor. Harrison’s Infectious Diseases. 1st ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2010:2183.

25. Yamada M, Buller R, Bledsoe S, Storch GA. Rising rates of macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae in the central United States. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31:409-410.

26. Yi SH, Hatfield KM, Baggs J, et al. Duration of antibiotic use among adults with uncomplicated community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66:1333-1341.

27. Hayashi Y, Paterson DL. Strategies for reduction in duration of antibiotic use in hospitalized patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:1232-1240.

28. Akram AR, Chalmers JD, Taylor JK, et al. An evaluation of clinical stability criteria to predict hospital course in community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19:1174-1180.

29. Halm EA, Fine MJ, Kapoor WN, et al. Instability on hospital discharge and the risk of adverse outcomes in patients with pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1278-1284.

30. Janoff EM. Streptococcus pneumonia. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, editors. Mandell, Douglas and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2015:2310-2327.

31. Roson B, Carratala J, Fernandez-Sabe N, et al. Causes and factors associated with early failure in hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:502-508.

32. El-Solh AA, Pietrantoni C, Bhat A, et al. Microbiology of severe aspiration pneumonia in institutionalized elderly. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:1650-1654.

33. Wan YD, Sun TW, Liu ZQ, et al. Efficacy and safety of corticosteroids for community-acquired pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2016;149:209-219.

34. Torres A, Sibila O, Ferrer M, et al. Effect of corticosteroids on treatment failure among hospitalized patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia and high inflammatory response: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313:677-686.

35. Lloyd M, Karahalios, Janus E, et al. Effectiveness of a bundled intervention including adjunctive corticosteroids on outcomes of hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia: a stepped-wedge randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:1052-1060.

36. Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. An official Clinical Practice Guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200:e45-e67.

37. McCullers JA. Insights into the interaction between influenza virus and pneumococcus. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:571-582.

38. Grohskopf LA, Alyanak E, Broder KR, et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices - United States, 2019-20 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2019;68:1-21.

39. Rubins JB, Alter M, Loch J, Janoff EN. Determination of antibody responses of elderly adults to all 23 capsular polysaccharides after pneumococcal vaccination. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5979-5984.

40. Vaccines and preventable diseases. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/pneumo/hcp/about-vaccine.html. Accessed 16 September 2019.

41. Bonten MJ, Huijts SM, Bolkenbaas M, et al. Polysaccharide conjugate vaccine against pneumococcal pneumonia in adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1114-1125.

42. Recommended adult immunization schedule -- United States -- 2019. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/downloads/adult/adult-combined-schedule.pdf. Accessed 16 September 2019.

43. Recommended child and adolescent immunization schedule for ages 18 years or younger – United States – 2019. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/imz/child-adolescent.html. Accessed 22 September 2019.

44. Pneumococcal vaccine timing for adults – United States – 2019. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/pneumo/downloads/pneumo-vaccine-timing.pdf. Accessed 22 September 2019.

1. Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM, et al A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med.1997;336:243-250.

2. Lim WS, van der Eerden MM, Laing R, et al. Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on presentation to hospital: an international derivation and validation study. Thorax. 2003;58:377-382.

3. Aujesky D, Auble TE, Yealy DM, et al. Prospective comparison of three validated prediction rules for prognosis in community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Med. 2005;118:384-392.

4. Arnold FW, Ramirez JA, McDonald LC, Xia EL. Hospitalization for community-acquired pneumonia: the pneumonia severity index vs clinical judgment. Chest. 2003;124:121-124.

5. Aujesky D, McCausland JB, Whittle J, et al. Reasons why emergency department providers do not rely on the pneumonia severity index to determine the initial site of treatment for patients with pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:e100-108.

6. Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44 Suppl 2:S27-72.

7. Charles PG, Wolfe R, Whitby M, et al. SMART-COP: a tool for predicting the need for intensive respiratory or vasopressor support in community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:375-384.

8. Marti C, Garin N, Grosgurin O, et al. Prediction of severe community-acquired pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2012;16:R141.

9. Jain S, Self WH, Wunderink RG, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:415-427.

10. Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, et al. Management of adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia: 2016 Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:e61-e111.

11. Wunderink RG, Niederman MS, Kollef MH, et al. Linezolid in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nosocomial pneumonia: a randomized, controlled study. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:621-629.

12. Silverman JA, Mortin LI, Vanpraagh AD, et al. Inhibition of daptomycin by pulmonary surfactant: in vitro modeling and clinical impact. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:2149-2152.

13. El Hajj MS, Turgeon RD, Wilby KJ. Ceftaroline fosamil for community-acquired pneumonia and skin and skin structure infections: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pharm. 2017;39:26-32.

14. Taboada M, Melnick D, Iaconis JP, et al. Ceftaroline fosamil versus ceftriaxone for the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia: individual patient data meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71:862-870.

15. Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children: executive summary. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:285-292.

16. Janoff EM. Streptococcus pneumonia. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, editors. Mandell, Douglas and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Sauders; 2015:2310-2327.

17. Teflaro (ceftaroline fosamil) [package insert]. St. Louis, MO: Forest Pharmaceuticals; 2010.

18. Nuzyra (omadacycline) [package insert]. Boston, MA: Paratek Pharmaceuticals; 2018.

19. Xenleta (lefamulin) [package insert]. Dublin, Ireland: Nabriva Therapeutics; 2019.

20. Baddour LM, Yu VL, Klugman KP, et al. Combination antibiotic therapy lowers mortality among severely ill patients with pneumococcal bacteremia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:440-444.

21. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA warns of increased risk of death with IV antibacterial Tygacil (tigecycline) and approves new boxed warning. www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm369580.htm. Accessed 16 September 2019.

22. Edelstein PR, CR. Legionnaires’ disease and Pontiac fever. In: Kasper DF, editor. Harrison’s Infectious Diseases. 1st ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2010:2633.

23. Hammerschlag MR, Kohlhoff SA, Gaydos, CA. Chlamydia pneumoniae. In: Kasper DF, editor. Harrison’s Infectious Diseases. 1st ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2010:2174.

24. Holzman RS, MS. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and atypical pneumonia. In: Kasper DF, editor. Harrison’s Infectious Diseases. 1st ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2010:2183.

25. Yamada M, Buller R, Bledsoe S, Storch GA. Rising rates of macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae in the central United States. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31:409-410.

26. Yi SH, Hatfield KM, Baggs J, et al. Duration of antibiotic use among adults with uncomplicated community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66:1333-1341.

27. Hayashi Y, Paterson DL. Strategies for reduction in duration of antibiotic use in hospitalized patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:1232-1240.

28. Akram AR, Chalmers JD, Taylor JK, et al. An evaluation of clinical stability criteria to predict hospital course in community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19:1174-1180.

29. Halm EA, Fine MJ, Kapoor WN, et al. Instability on hospital discharge and the risk of adverse outcomes in patients with pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1278-1284.

30. Janoff EM. Streptococcus pneumonia. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, editors. Mandell, Douglas and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2015:2310-2327.

31. Roson B, Carratala J, Fernandez-Sabe N, et al. Causes and factors associated with early failure in hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:502-508.