User login

Fool Me Twice: The Role for Hospitals and Health Systems in Fixing the Broken PPE Supply Chain

The story of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in the United States has been defined, in part, by a persistent shortage of medical supplies that has made it difficult and dangerous for healthcare workers to care for infected patients. States, health systems, and even individual hospitals are currently competing against one another—sometimes at auction—to obtain personal protective equipment (PPE). This “Wild West” scenario has resulted in bizarre stories involving attempts to obtain PPE. One health system recently described a James Bond–like pursuit of essential PPE, complete with a covert trip to an industrial warehouse, trucks filled with masks but labeled as food delivery vehicles, and an intervention by a United States congressman.1 Many states have experienced analogous, but still atypical, stories: masks flown in from China using the private jet of a professional sports team owner,2 widespread use of novel sterilization modalities to allow PPE reuse,3 and one attempt to purchase price-gouged PPE from the host of the show “Shark Tank.”4 In some cases, hospitals and healthcare workers have pleaded for PPE on fundraising and social media sites.5

These profound deviations from operations of contemporary health system supply chains would have seemed beyond belief just a few months ago. Instead, they now echo the collective experiences of healthcare stakeholders trying to obtain PPE to protect their frontline healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

HEALTHCARE MARKETS DURING A PANDEMIC

How did we get into this situation? The manufacture of medical supplies like gowns and masks is a highly competitive business with very slim margins, and as a result, medical equipment manufacturers aim to match their supply with the market’s demand, with hospitals and health systems using just-in-time ordering to limit excess inventory.6 While this approach adds efficiency and reduces costs, it also renders manufacturers and customers vulnerable to supply disruptions and shortages when need surges. The COVID-19 pandemic represents perhaps the most extreme example of a massive, widespread surge in demand that occurred multifocally and in a highly compressed time frame. Unlike other industries (eg, consumer paper products), however, in which demand exceeding supply causes inconvenience, the lack of PPE has led to critical public health consequences, with lives of both healthcare workers and vulnerable patients lost because of these shortages of medical equipment.

THE SPECIAL CASE OF PPE

There are many reasons for the PPE crisis. As noted above, manufacturers have prioritized efficiency over the ability to quickly increase production. They adhere to just-in-time ordering rather than planning for a surge in demand with extra production capacity, all to avoid having warehouses filled with unsold products if surges never occur. This strategy, compounded by the fact that most PPE in the United States is imported from areas in Asia that were profoundly affected early on by COVID-19, led to the observed widespread shortages. When PPE became unavailable from usual suppliers, hospitals were unable to locate other sources of existing PPE because of a lack of transparency about where PPE could be found and how it could be obtained. The Food and Drug Administration and other federal regulatory agencies maintained strict regulations around PPE production and, despite the crisis, made few exceptions.7 The FDA did grant a few Emergency Use Authorizations (EUAs) for certain improvised, decontaminated, or alternative respirators (eg, the Chinese-made KN95), but it has only very infrequently issued EUAs to allow domestic manufacturers to ramp up production.8 These failures were accompanied by an serious increase in PPE use, leading to spikes in price, price gouging, and hoarding,9 problems that were further magnified as health systems and hospitals were forced to compete with nonhealthcare businesses for PPE.

LACK OF FEDERAL GOVERNMENT RESPONSE

The Defense Production Act (DPA) gives the federal government the power to increase production of goods needed during a crisis8 to offer purchasing guarantees, coordinate federal agencies, and regulate distribution and pricing. However, the current administration’s failure to mount a coordinated federal response has contributed to the observed market instability, medical supply shortages, and public health crisis we face. We have previously recommended that the federal government use the power of the DPA to reduce manufacturers’ risk of being uncompensated for excess supply, support temporary reductions in regulatory barriers, and create mandatory centralized reporting of PPE supply, including completed PPE and its components.10 We stand by these recommendations but also acknowledge that hospitals and health systems may be simultaneously considering how to best prepare for future crises and even surges in demand over the next 18 months as the COVID-19 pandemic continues.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR HEALTH SYSTEMS AND HOSPITALS

1. Encourage mandates at the hospital, health system, and state level regarding minimum inventory levels for essential equipment. Stockpiles are essential for emergency preparedness. In the long term, these sorts of stockpiles are economically infeasible without government help to maintain them. In the near term, however, it is sensible that hospitals and health systems would maintain a minimum of 2 weeks’ worth of PPE to prepare for expected regional spikes in COVID-19 cases. However, a soon-to-published study suggests that over 40% of hospitals had a PPE stockpile of less than 2 weeks.11 Although this survey was conducted at the height of the shortage, it suggests that there is opportunity for improvement.

2. Coordinate efforts among states and health systems to collect and report inventory, regionalize resources, and coordinate their distribution. The best example of this is the seven-state purchasing consortium announced by New York Governor Andrew Cuomo in early May.12 Unfortunately, since the announcement, there have been few details about whether the states were successful in their effort to reduce prices or to obtain PPE in bulk. Still, hospitals and health systems could join or emulate purchasing collaboratives to allow resources to be better allocated according to need. There are barriers to such collaboratives because the market is currently set up to encourage competition among health systems and hospitals. During the pandemic, however, cooperation has increasingly been favored over competition in science and healthcare delivery. There are also existing hospital purchasing collaboratives (eg, Premier, Inc13), which have taken steps to vet suppliers and improve access to PPE, but it is not clear how successful these efforts have been to date.

3. Advocate for strong federal leadership, including support for increased domestic manufacturing; replenishment and maintenance of state and health system stockpiles of PPE, ventilators, and medications; and development of a centrally coordinated PPE allocation and distribution process. While hospitals and health systems may favor remaining as apolitical as possible, the need for a federal response to stabilize the PPE market may be too urgent and necessary to ignore.

CONCLUSION

As hospitals and health systems prepare for continued surges in COVID-19 cases, they face challenges in providing PPE for frontline clinicians and staff. A federal plan to enhance nimbleness in responding to multifocal, geographic outbreaks and ensure awareness regarding inventory would improve our chances to successfully navigate the next pandemic and optimize the protection of our health workers, patients, and public health. In the absence of such a plan, hospitals should maintain a minimum of 2 weeks’ worth of PPE to prepare for expected regional spikes in COVID-19 cases and should continue to attempt to coordinate efforts among states and health systems to collect and report inventory, regionalize resources, and coordinate their distribution.

1. Artenstein AW. In pursuit of PPE. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):e46. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmc2010025

2. McGrane V, Ellement JR. A Patriots plane full of 1 million N95 masks from China arrived Thursday. Here’s how the plan came together. Boston Globe. Updated April 2, 2020. Accessed April 27, 2020. https://www.bostonglobe.com/2020/04/02/nation/kraft-family-used-patriots-team-plane-shuttle-protective-masks-china-boston-wsj-reports/

3. Kolodny L. California plans to decontaminate 80,000 masks a day for health workers amid the COVID-19 pandemic. CNBC. April 8, 2020. Updated April 9, 2020. Accessed April 27, 2020. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/04/08/california-plans-to-sanitize-80000-n95-masks-a-day-for-health-workers.html

4. Levenson M. Company questions deal by ‘Shark Tank’ star to sell N95 masks to Florida. New York Times. April 22, 2020. Accessed May 20, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/22/us/daymond-john-n95-masks-florida-3m.html

5. Padilla M. ‘It feels like a war zone’: doctors and nurses plead for masks on social media. New York Times. March 19, 2020. Updated March 22, 2020. Accessed April 27, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/19/us/hospitals-coronavirus-ppe-shortage.html

6. Lee HL, Billington C. Managing supply chain inventory: pitfalls and opportunities. MIT Sloan Management Review. April 15, 1992. Accessed April 27, 2020. https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/managing-supply-chain-inventory-pitfalls-and-opportunities/

7. Emergency Situations (Medical Devices): Emergency Use Authorizations. Food and Drug Administration. Accessed May 10, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/emergency-situations-medical-devices/emergency-use-authorizations

8. Watney C, Stapp A. Masks for All: Using Purchase Guarantees and Targeted Deregulation to Boost Production of Essential Medical Equipment. Mercatus Center: George Mason University. April 8, 2020. Accessed June 23, 2020. https://www.mercatus.org/publications/covid-19-crisis-response/masks-all-using-purchase-guarantees-and-targeted-deregulation

9. Volkov M. DOJ hoarding and price gouging task force seizes critical medical supplies and distributes to New York and New Jersey hospitals. Corruption, Crime & Compliance blog. April 2, 2020. Accessed April 27, 2020. https://blog.volkovlaw.com/2020/04/doj-hoarding-and-price-gouging-task-force-seizes-critical-medical-supplies-and-distributes-to-new-york-and-new-jersey-hospitals/

10. Lagu T, Werner R, Artenstein AW. Why don’t hospitals have enough masks? Because coronavirus broke the market. Washington Post. May 21, 2020. Accessed May 25, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2020/05/21/why-dont-hospitals-have-enough-masks-because-coronavirus-broke-market/

11. Auerbach A, O’Leary KJ, Harrison JD, et al. Hospital ward adaptation during the COVID-19 Pandemic: a national survey of academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:483-488.

12. Voytko L. NY will team up with 6 states to buy medical supplies, Cuomo says. Forbes. May 3, 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/lisettevoytko/2020/05/03/ny-will-team-up-with-6-states-to-buy-medical-supplies-cuomo-says/

13. Premier. Supply Chain Solutions. Accessed May 26, 2020. https://www.premierinc.com/solutions/supply-chain

The story of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in the United States has been defined, in part, by a persistent shortage of medical supplies that has made it difficult and dangerous for healthcare workers to care for infected patients. States, health systems, and even individual hospitals are currently competing against one another—sometimes at auction—to obtain personal protective equipment (PPE). This “Wild West” scenario has resulted in bizarre stories involving attempts to obtain PPE. One health system recently described a James Bond–like pursuit of essential PPE, complete with a covert trip to an industrial warehouse, trucks filled with masks but labeled as food delivery vehicles, and an intervention by a United States congressman.1 Many states have experienced analogous, but still atypical, stories: masks flown in from China using the private jet of a professional sports team owner,2 widespread use of novel sterilization modalities to allow PPE reuse,3 and one attempt to purchase price-gouged PPE from the host of the show “Shark Tank.”4 In some cases, hospitals and healthcare workers have pleaded for PPE on fundraising and social media sites.5

These profound deviations from operations of contemporary health system supply chains would have seemed beyond belief just a few months ago. Instead, they now echo the collective experiences of healthcare stakeholders trying to obtain PPE to protect their frontline healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

HEALTHCARE MARKETS DURING A PANDEMIC

How did we get into this situation? The manufacture of medical supplies like gowns and masks is a highly competitive business with very slim margins, and as a result, medical equipment manufacturers aim to match their supply with the market’s demand, with hospitals and health systems using just-in-time ordering to limit excess inventory.6 While this approach adds efficiency and reduces costs, it also renders manufacturers and customers vulnerable to supply disruptions and shortages when need surges. The COVID-19 pandemic represents perhaps the most extreme example of a massive, widespread surge in demand that occurred multifocally and in a highly compressed time frame. Unlike other industries (eg, consumer paper products), however, in which demand exceeding supply causes inconvenience, the lack of PPE has led to critical public health consequences, with lives of both healthcare workers and vulnerable patients lost because of these shortages of medical equipment.

THE SPECIAL CASE OF PPE

There are many reasons for the PPE crisis. As noted above, manufacturers have prioritized efficiency over the ability to quickly increase production. They adhere to just-in-time ordering rather than planning for a surge in demand with extra production capacity, all to avoid having warehouses filled with unsold products if surges never occur. This strategy, compounded by the fact that most PPE in the United States is imported from areas in Asia that were profoundly affected early on by COVID-19, led to the observed widespread shortages. When PPE became unavailable from usual suppliers, hospitals were unable to locate other sources of existing PPE because of a lack of transparency about where PPE could be found and how it could be obtained. The Food and Drug Administration and other federal regulatory agencies maintained strict regulations around PPE production and, despite the crisis, made few exceptions.7 The FDA did grant a few Emergency Use Authorizations (EUAs) for certain improvised, decontaminated, or alternative respirators (eg, the Chinese-made KN95), but it has only very infrequently issued EUAs to allow domestic manufacturers to ramp up production.8 These failures were accompanied by an serious increase in PPE use, leading to spikes in price, price gouging, and hoarding,9 problems that were further magnified as health systems and hospitals were forced to compete with nonhealthcare businesses for PPE.

LACK OF FEDERAL GOVERNMENT RESPONSE

The Defense Production Act (DPA) gives the federal government the power to increase production of goods needed during a crisis8 to offer purchasing guarantees, coordinate federal agencies, and regulate distribution and pricing. However, the current administration’s failure to mount a coordinated federal response has contributed to the observed market instability, medical supply shortages, and public health crisis we face. We have previously recommended that the federal government use the power of the DPA to reduce manufacturers’ risk of being uncompensated for excess supply, support temporary reductions in regulatory barriers, and create mandatory centralized reporting of PPE supply, including completed PPE and its components.10 We stand by these recommendations but also acknowledge that hospitals and health systems may be simultaneously considering how to best prepare for future crises and even surges in demand over the next 18 months as the COVID-19 pandemic continues.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR HEALTH SYSTEMS AND HOSPITALS

1. Encourage mandates at the hospital, health system, and state level regarding minimum inventory levels for essential equipment. Stockpiles are essential for emergency preparedness. In the long term, these sorts of stockpiles are economically infeasible without government help to maintain them. In the near term, however, it is sensible that hospitals and health systems would maintain a minimum of 2 weeks’ worth of PPE to prepare for expected regional spikes in COVID-19 cases. However, a soon-to-published study suggests that over 40% of hospitals had a PPE stockpile of less than 2 weeks.11 Although this survey was conducted at the height of the shortage, it suggests that there is opportunity for improvement.

2. Coordinate efforts among states and health systems to collect and report inventory, regionalize resources, and coordinate their distribution. The best example of this is the seven-state purchasing consortium announced by New York Governor Andrew Cuomo in early May.12 Unfortunately, since the announcement, there have been few details about whether the states were successful in their effort to reduce prices or to obtain PPE in bulk. Still, hospitals and health systems could join or emulate purchasing collaboratives to allow resources to be better allocated according to need. There are barriers to such collaboratives because the market is currently set up to encourage competition among health systems and hospitals. During the pandemic, however, cooperation has increasingly been favored over competition in science and healthcare delivery. There are also existing hospital purchasing collaboratives (eg, Premier, Inc13), which have taken steps to vet suppliers and improve access to PPE, but it is not clear how successful these efforts have been to date.

3. Advocate for strong federal leadership, including support for increased domestic manufacturing; replenishment and maintenance of state and health system stockpiles of PPE, ventilators, and medications; and development of a centrally coordinated PPE allocation and distribution process. While hospitals and health systems may favor remaining as apolitical as possible, the need for a federal response to stabilize the PPE market may be too urgent and necessary to ignore.

CONCLUSION

As hospitals and health systems prepare for continued surges in COVID-19 cases, they face challenges in providing PPE for frontline clinicians and staff. A federal plan to enhance nimbleness in responding to multifocal, geographic outbreaks and ensure awareness regarding inventory would improve our chances to successfully navigate the next pandemic and optimize the protection of our health workers, patients, and public health. In the absence of such a plan, hospitals should maintain a minimum of 2 weeks’ worth of PPE to prepare for expected regional spikes in COVID-19 cases and should continue to attempt to coordinate efforts among states and health systems to collect and report inventory, regionalize resources, and coordinate their distribution.

The story of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in the United States has been defined, in part, by a persistent shortage of medical supplies that has made it difficult and dangerous for healthcare workers to care for infected patients. States, health systems, and even individual hospitals are currently competing against one another—sometimes at auction—to obtain personal protective equipment (PPE). This “Wild West” scenario has resulted in bizarre stories involving attempts to obtain PPE. One health system recently described a James Bond–like pursuit of essential PPE, complete with a covert trip to an industrial warehouse, trucks filled with masks but labeled as food delivery vehicles, and an intervention by a United States congressman.1 Many states have experienced analogous, but still atypical, stories: masks flown in from China using the private jet of a professional sports team owner,2 widespread use of novel sterilization modalities to allow PPE reuse,3 and one attempt to purchase price-gouged PPE from the host of the show “Shark Tank.”4 In some cases, hospitals and healthcare workers have pleaded for PPE on fundraising and social media sites.5

These profound deviations from operations of contemporary health system supply chains would have seemed beyond belief just a few months ago. Instead, they now echo the collective experiences of healthcare stakeholders trying to obtain PPE to protect their frontline healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

HEALTHCARE MARKETS DURING A PANDEMIC

How did we get into this situation? The manufacture of medical supplies like gowns and masks is a highly competitive business with very slim margins, and as a result, medical equipment manufacturers aim to match their supply with the market’s demand, with hospitals and health systems using just-in-time ordering to limit excess inventory.6 While this approach adds efficiency and reduces costs, it also renders manufacturers and customers vulnerable to supply disruptions and shortages when need surges. The COVID-19 pandemic represents perhaps the most extreme example of a massive, widespread surge in demand that occurred multifocally and in a highly compressed time frame. Unlike other industries (eg, consumer paper products), however, in which demand exceeding supply causes inconvenience, the lack of PPE has led to critical public health consequences, with lives of both healthcare workers and vulnerable patients lost because of these shortages of medical equipment.

THE SPECIAL CASE OF PPE

There are many reasons for the PPE crisis. As noted above, manufacturers have prioritized efficiency over the ability to quickly increase production. They adhere to just-in-time ordering rather than planning for a surge in demand with extra production capacity, all to avoid having warehouses filled with unsold products if surges never occur. This strategy, compounded by the fact that most PPE in the United States is imported from areas in Asia that were profoundly affected early on by COVID-19, led to the observed widespread shortages. When PPE became unavailable from usual suppliers, hospitals were unable to locate other sources of existing PPE because of a lack of transparency about where PPE could be found and how it could be obtained. The Food and Drug Administration and other federal regulatory agencies maintained strict regulations around PPE production and, despite the crisis, made few exceptions.7 The FDA did grant a few Emergency Use Authorizations (EUAs) for certain improvised, decontaminated, or alternative respirators (eg, the Chinese-made KN95), but it has only very infrequently issued EUAs to allow domestic manufacturers to ramp up production.8 These failures were accompanied by an serious increase in PPE use, leading to spikes in price, price gouging, and hoarding,9 problems that were further magnified as health systems and hospitals were forced to compete with nonhealthcare businesses for PPE.

LACK OF FEDERAL GOVERNMENT RESPONSE

The Defense Production Act (DPA) gives the federal government the power to increase production of goods needed during a crisis8 to offer purchasing guarantees, coordinate federal agencies, and regulate distribution and pricing. However, the current administration’s failure to mount a coordinated federal response has contributed to the observed market instability, medical supply shortages, and public health crisis we face. We have previously recommended that the federal government use the power of the DPA to reduce manufacturers’ risk of being uncompensated for excess supply, support temporary reductions in regulatory barriers, and create mandatory centralized reporting of PPE supply, including completed PPE and its components.10 We stand by these recommendations but also acknowledge that hospitals and health systems may be simultaneously considering how to best prepare for future crises and even surges in demand over the next 18 months as the COVID-19 pandemic continues.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR HEALTH SYSTEMS AND HOSPITALS

1. Encourage mandates at the hospital, health system, and state level regarding minimum inventory levels for essential equipment. Stockpiles are essential for emergency preparedness. In the long term, these sorts of stockpiles are economically infeasible without government help to maintain them. In the near term, however, it is sensible that hospitals and health systems would maintain a minimum of 2 weeks’ worth of PPE to prepare for expected regional spikes in COVID-19 cases. However, a soon-to-published study suggests that over 40% of hospitals had a PPE stockpile of less than 2 weeks.11 Although this survey was conducted at the height of the shortage, it suggests that there is opportunity for improvement.

2. Coordinate efforts among states and health systems to collect and report inventory, regionalize resources, and coordinate their distribution. The best example of this is the seven-state purchasing consortium announced by New York Governor Andrew Cuomo in early May.12 Unfortunately, since the announcement, there have been few details about whether the states were successful in their effort to reduce prices or to obtain PPE in bulk. Still, hospitals and health systems could join or emulate purchasing collaboratives to allow resources to be better allocated according to need. There are barriers to such collaboratives because the market is currently set up to encourage competition among health systems and hospitals. During the pandemic, however, cooperation has increasingly been favored over competition in science and healthcare delivery. There are also existing hospital purchasing collaboratives (eg, Premier, Inc13), which have taken steps to vet suppliers and improve access to PPE, but it is not clear how successful these efforts have been to date.

3. Advocate for strong federal leadership, including support for increased domestic manufacturing; replenishment and maintenance of state and health system stockpiles of PPE, ventilators, and medications; and development of a centrally coordinated PPE allocation and distribution process. While hospitals and health systems may favor remaining as apolitical as possible, the need for a federal response to stabilize the PPE market may be too urgent and necessary to ignore.

CONCLUSION

As hospitals and health systems prepare for continued surges in COVID-19 cases, they face challenges in providing PPE for frontline clinicians and staff. A federal plan to enhance nimbleness in responding to multifocal, geographic outbreaks and ensure awareness regarding inventory would improve our chances to successfully navigate the next pandemic and optimize the protection of our health workers, patients, and public health. In the absence of such a plan, hospitals should maintain a minimum of 2 weeks’ worth of PPE to prepare for expected regional spikes in COVID-19 cases and should continue to attempt to coordinate efforts among states and health systems to collect and report inventory, regionalize resources, and coordinate their distribution.

1. Artenstein AW. In pursuit of PPE. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):e46. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmc2010025

2. McGrane V, Ellement JR. A Patriots plane full of 1 million N95 masks from China arrived Thursday. Here’s how the plan came together. Boston Globe. Updated April 2, 2020. Accessed April 27, 2020. https://www.bostonglobe.com/2020/04/02/nation/kraft-family-used-patriots-team-plane-shuttle-protective-masks-china-boston-wsj-reports/

3. Kolodny L. California plans to decontaminate 80,000 masks a day for health workers amid the COVID-19 pandemic. CNBC. April 8, 2020. Updated April 9, 2020. Accessed April 27, 2020. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/04/08/california-plans-to-sanitize-80000-n95-masks-a-day-for-health-workers.html

4. Levenson M. Company questions deal by ‘Shark Tank’ star to sell N95 masks to Florida. New York Times. April 22, 2020. Accessed May 20, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/22/us/daymond-john-n95-masks-florida-3m.html

5. Padilla M. ‘It feels like a war zone’: doctors and nurses plead for masks on social media. New York Times. March 19, 2020. Updated March 22, 2020. Accessed April 27, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/19/us/hospitals-coronavirus-ppe-shortage.html

6. Lee HL, Billington C. Managing supply chain inventory: pitfalls and opportunities. MIT Sloan Management Review. April 15, 1992. Accessed April 27, 2020. https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/managing-supply-chain-inventory-pitfalls-and-opportunities/

7. Emergency Situations (Medical Devices): Emergency Use Authorizations. Food and Drug Administration. Accessed May 10, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/emergency-situations-medical-devices/emergency-use-authorizations

8. Watney C, Stapp A. Masks for All: Using Purchase Guarantees and Targeted Deregulation to Boost Production of Essential Medical Equipment. Mercatus Center: George Mason University. April 8, 2020. Accessed June 23, 2020. https://www.mercatus.org/publications/covid-19-crisis-response/masks-all-using-purchase-guarantees-and-targeted-deregulation

9. Volkov M. DOJ hoarding and price gouging task force seizes critical medical supplies and distributes to New York and New Jersey hospitals. Corruption, Crime & Compliance blog. April 2, 2020. Accessed April 27, 2020. https://blog.volkovlaw.com/2020/04/doj-hoarding-and-price-gouging-task-force-seizes-critical-medical-supplies-and-distributes-to-new-york-and-new-jersey-hospitals/

10. Lagu T, Werner R, Artenstein AW. Why don’t hospitals have enough masks? Because coronavirus broke the market. Washington Post. May 21, 2020. Accessed May 25, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2020/05/21/why-dont-hospitals-have-enough-masks-because-coronavirus-broke-market/

11. Auerbach A, O’Leary KJ, Harrison JD, et al. Hospital ward adaptation during the COVID-19 Pandemic: a national survey of academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:483-488.

12. Voytko L. NY will team up with 6 states to buy medical supplies, Cuomo says. Forbes. May 3, 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/lisettevoytko/2020/05/03/ny-will-team-up-with-6-states-to-buy-medical-supplies-cuomo-says/

13. Premier. Supply Chain Solutions. Accessed May 26, 2020. https://www.premierinc.com/solutions/supply-chain

1. Artenstein AW. In pursuit of PPE. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):e46. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmc2010025

2. McGrane V, Ellement JR. A Patriots plane full of 1 million N95 masks from China arrived Thursday. Here’s how the plan came together. Boston Globe. Updated April 2, 2020. Accessed April 27, 2020. https://www.bostonglobe.com/2020/04/02/nation/kraft-family-used-patriots-team-plane-shuttle-protective-masks-china-boston-wsj-reports/

3. Kolodny L. California plans to decontaminate 80,000 masks a day for health workers amid the COVID-19 pandemic. CNBC. April 8, 2020. Updated April 9, 2020. Accessed April 27, 2020. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/04/08/california-plans-to-sanitize-80000-n95-masks-a-day-for-health-workers.html

4. Levenson M. Company questions deal by ‘Shark Tank’ star to sell N95 masks to Florida. New York Times. April 22, 2020. Accessed May 20, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/22/us/daymond-john-n95-masks-florida-3m.html

5. Padilla M. ‘It feels like a war zone’: doctors and nurses plead for masks on social media. New York Times. March 19, 2020. Updated March 22, 2020. Accessed April 27, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/19/us/hospitals-coronavirus-ppe-shortage.html

6. Lee HL, Billington C. Managing supply chain inventory: pitfalls and opportunities. MIT Sloan Management Review. April 15, 1992. Accessed April 27, 2020. https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/managing-supply-chain-inventory-pitfalls-and-opportunities/

7. Emergency Situations (Medical Devices): Emergency Use Authorizations. Food and Drug Administration. Accessed May 10, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/emergency-situations-medical-devices/emergency-use-authorizations

8. Watney C, Stapp A. Masks for All: Using Purchase Guarantees and Targeted Deregulation to Boost Production of Essential Medical Equipment. Mercatus Center: George Mason University. April 8, 2020. Accessed June 23, 2020. https://www.mercatus.org/publications/covid-19-crisis-response/masks-all-using-purchase-guarantees-and-targeted-deregulation

9. Volkov M. DOJ hoarding and price gouging task force seizes critical medical supplies and distributes to New York and New Jersey hospitals. Corruption, Crime & Compliance blog. April 2, 2020. Accessed April 27, 2020. https://blog.volkovlaw.com/2020/04/doj-hoarding-and-price-gouging-task-force-seizes-critical-medical-supplies-and-distributes-to-new-york-and-new-jersey-hospitals/

10. Lagu T, Werner R, Artenstein AW. Why don’t hospitals have enough masks? Because coronavirus broke the market. Washington Post. May 21, 2020. Accessed May 25, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2020/05/21/why-dont-hospitals-have-enough-masks-because-coronavirus-broke-market/

11. Auerbach A, O’Leary KJ, Harrison JD, et al. Hospital ward adaptation during the COVID-19 Pandemic: a national survey of academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:483-488.

12. Voytko L. NY will team up with 6 states to buy medical supplies, Cuomo says. Forbes. May 3, 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/lisettevoytko/2020/05/03/ny-will-team-up-with-6-states-to-buy-medical-supplies-cuomo-says/

13. Premier. Supply Chain Solutions. Accessed May 26, 2020. https://www.premierinc.com/solutions/supply-chain

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Overlap between Medicare’s Voluntary Bundled Payment and Accountable Care Organization Programs

Voluntary accountable care organizations (ACOs) and bundled payments have concurrently become cornerstone strategies in Medicare’s shift from volume-based fee-for-service toward value-based payment.

Physician practice and hospital participation in Medicare’s largest ACO model, the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP),1 grew to include 561 organizations in 2018. Under MSSP, participants assume financial accountability for the global quality and costs of care for defined populations of Medicare fee-for-service patients. ACOs that manage to maintain or improve quality while achieving savings (ie, containing costs below a predefined population-wide spending benchmark) are eligible to receive a portion of the difference back from Medicare in the form of “shared savings”.

Similarly, hospital participation in Medicare’s bundled payment programs has grown over time. Most notably, more than 700 participants enrolled in the recently concluded Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative,2 Medicare’s largest bundled payment program over the past five years.3 Under BPCI, participants assumed financial accountability for the quality and costs of care for all Medicare patients triggering a qualifying “episode of care”. Participants that limit episode spending below a predefined benchmark without compromising quality were eligible for financial incentives.

As both ACOs and bundled payments grow in prominence and scale, they may increasingly overlap if patients attributed to ACOs receive care at bundled payment hospitals. Overlap could create synergies by increasing incentives to address shared processes (eg, discharge planning) or outcomes (eg, readmissions).4 An ACO focus on reducing hospital admissions could complement bundled payment efforts to increase hospital efficiency.

Conversely, Medicare’s approach to allocating savings and losses can penalize ACOs or bundled payment participants.3 For example, when a patient included in an MSSP ACO population receives episodic care at a hospital participating in BPCI, the historical costs of care for the hospital and the episode type, not the actual costs of care for that specific patient and his/her episode, are counted in the performance of the ACO. In other words, in these cases, the performance of the MSSP ACO is dependent on the historical spending at BPCI hospitals—despite it being out of ACO’s control and having little to do with the actual care its patients receive at BPCI hospitals—and MSSP ACOs cannot benefit from improvements over time. Therefore, MSSP ACOs may be functionally penalized if patients receive care at historically high-cost BPCI hospitals regardless of whether they have considerably improved the value of care delivered. As a corollary, Medicare rules involve a “claw back” stipulation in which savings are recouped from hospitals that participate in both BPCI and MSSP, effectively discouraging participation in both payment models.

Although these dynamics are complex, they highlight an intuitive point that has gained increasing awareness,5 ie, policymakers must understand the magnitude of overlap to evaluate the urgency in coordinating between the payment models. Our objective was to describe the extent of overlap and the characteristics of patients affected by it.

METHODS

We used 100% institutional Medicare claims, MSSP beneficiary attribution, and BPCI hospital data to identify fee-for-service beneficiaries attributed to MSSP and/or receiving care at BPCI hospitals for its 48 included episodes from the start of BPCI in 2013 quarter 4 through 2016 quarter 4.

We examined the trends in the number of episodes across the following three groups: MSSP-attributed patients hospitalized at BPCI hospitals for an episode included in BPCI (Overlap), MSSP-attributed patients hospitalized for that episode at non-BPCI hospitals (MSSP-only), and non-MSSP-attributed patients hospitalized at BPCI hospitals for a BPCI episode (BPCI-only). We used Medicare and United States Census Bureau data to compare groups with respect to sociodemographic (eg, age, sex, residence in a low-income area),6 clinical (eg, Elixhauser comorbidity index),7 and prior utilization (eg, skilled nursing facility discharge) characteristics.

Categorical and continuous variables were compared using logistic regression and one-way analysis of variance, respectively. Analyses were performed using Stata (StataCorp, College Station, Texas), version 15.0. Statistical tests were 2-tailed and significant at α = 0.05. This study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Pennsylvania.

RESULTS

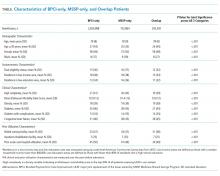

The number of MSSP ACOs increased from 220 in 2013 to 432 in 2016. The number of BPCI hospitals increased from 9 to 389 over this period, peaking at 413 hospitals in 2015. Over our study period, a total of 243,392, 2,824,898, and 702,864 episodes occurred in the Overlap, ACO-only, and BPCI-only groups, respectively (Table). Among episodes, patients in the Overlap group generally showed lower severity than those in other groups, although the differences were small. The BPCI-only, MSSP-only, and Overlap groups also exhibited small differences with respect to other characteristics such as the proportion of patients with Medicare/Medicaid dual-eligibility (15% of individual vs 16% and 12%, respectively) and prior use of skilled nursing facilities (33% vs 34% vs 31%, respectively) and acute care hospitals (45% vs 41% vs 39%, respectively) (P < .001 for all).

The overall overlap facing MSSP patients (overlap as a proportion of all MSSP patients) increased from 0.3% at the end of 2013 to 10% at the end of 2016, whereas over the same period, overlap facing bundled payment patients (overlap as a proportion of all bundled payment patients) increased from 11.9% to 27% (Appendix Figure). Overlap facing MSSP ACOs varied according to episode type, ranging from 3% for both acute myocardial infarction and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease episodes to 18% for automatic implantable cardiac defibrillator episodes at the end of 2016. Similarly, overlap facing bundled payment patients varied from 21% for spinal fusion episodes to 32% for lower extremity joint replacement and automatic implantable cardiac defibrillator episodes.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe the sizable and growing overlap facing ACOs with attributed patients who receive care at bundled payment hospitals, as well as bundled payment hospitals that treat patients attributed to ACOs.

The major implication of our findings is that policymakers must address and anticipate forthcoming payment model overlap as a key policy priority. Given the emphasis on ACOs and bundled payments as payment models—for example, Medicare continues to implement both nationwide via the Next Generation ACO model8 and the recently launched BPCI-Advanced program9—policymakers urgently need insights about the extent of payment model overlap. In that context, it is notable that although we have evaluated MSSP and BPCI as flagship programs, true overlap may actually be greater once other programs are considered.

Several factors may underlie the differences in the magnitude of overlap facing bundled payment versus ACO patients. The models differ in how they identify relevant patient populations, with patients falling under bundled payments via hospitalization for certain episode types but patients falling under ACOs via attribution based on the plurality of primary care services. Furthermore, BPCI participation lagged behind MSSP participation in time, while also occurring disproportionately in areas with existing MSSP ACOs.

Given these findings, understanding the implications of overlap should be a priority for future research and policy strategies. Potential policy considerations should include revising cost accounting processes so that when ACO-attributed patients receive episodic care at bundled payment hospitals, actual rather than historical hospital costs are counted toward ACO cost performance. To encourage hospitals to assume more accountability over outcomes—the ostensible overarching goal of value-based payment reform—Medicare could elect not to recoup savings from hospitals in both payment models. Although such changes require careful accounting to protect Medicare from financial losses as it forgoes some savings achieved through payment reforms, this may be worthwhile if hospital engagement in both models yields synergies.

Importantly, any policy changes made to address program overlap would need to accommodate ongoing changes in ACO, bundled payments, and other payment programs. For example, Medicare overhauled MSSP in December 2018. Compared to the earlier rules, in which ACOs could avoid downside financial risk altogether via “upside only” arrangements for up to six years, new MSSP rules require all participants to assume downside risk after several years of participation. Separately, forthcoming payment reforms such as direct contracting10 may draw clinicians and hospitals previously not participating in either Medicare fee-for-service or value-based payment models into payment reform. These factors may affect overlap in unpredictable ways (eg, they may increase the overlap by increasing the number of patients whose care is covered by different payment models or they may decrease overlap by raising the financial stakes of payment reforms to a degree that organizations drop out altogether).

This study has limitations. First, generalizability is limited by the fact that our analysis did not include bundled payment episodes assigned to physician group participants in BPCI or hospitals in mandatory joint replacement bundles under the Medicare Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement model.11 Second, although this study provides the first description of overlap between ACO and bundled payment programs, it was descriptive in nature. Future research is needed to evaluate the impact of overlap on clinical, quality, and cost outcomes. This is particularly important because although we observed only small differences in patient characteristics among MSSP-only, BPCI-only, and Overlap groups, characteristics could change differentially over time. Payment reforms must be carefully monitored for potentially unintended consequences that could arise from differential changes in patient characteristics (eg, cherry-picking behavior that is disadvantageous to vulnerable individuals).

Nonetheless, this study underscores the importance and extent of overlap and the urgency to consider policy measures to coordinate between the payment models.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank research assistance from Sandra Vanderslice who did not receive any compensation for her work. This research was supported in part by The Commonwealth Fund. Rachel Werner was supported in part by K24-AG047908 from the NIA.

1. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Shared Savings Program. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-For-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/index.html. Accessed July 22, 2019.

2. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) Initiative: General Information. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bundled-payments/. Accessed July 22, 2019.

3. Mechanic RE. When new Medicare payment systems collide. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(18):1706-1709. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1601464.

4. Ryan AM, Krinsky S, Adler-Milstein J, Damberg CL, Maurer KA, Hollingsworth JM. Association between hospitals’ engagement in value-based reforms and readmission reduction in the hospital readmission reduction program. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(6):863-868. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0518.

5. Liao JM, Dykstra SE, Werner RM, Navathe AS. BPCI Advanced will further emphasize the need to address overlap between bundled payments and accountable care organizations. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20180409.159181/full/. Accessed May 14, 2019.

6. Census Bureau. United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/. Accessed May 14, 2018.

7. van Walraven C, Austin PC, Jennings A, Quan H, Forster AJ. A modification of the elixhauser comorbidity measures into a point system for hospital death using administrative data. Med Care. 2009;47(6):626-633. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819432e5.

8. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Next, Generation ACO Model. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/next-generation-aco-model/. Accessed July 22, 2019.

9. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. BPCI Advanced. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bpci-advanced. Accessed July 22, 2019.

10. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Direct Contracting. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/direct-contracting. Accessed July 22, 2019.

11. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Model. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/CJR. Accessed July 22, 2019.

Voluntary accountable care organizations (ACOs) and bundled payments have concurrently become cornerstone strategies in Medicare’s shift from volume-based fee-for-service toward value-based payment.

Physician practice and hospital participation in Medicare’s largest ACO model, the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP),1 grew to include 561 organizations in 2018. Under MSSP, participants assume financial accountability for the global quality and costs of care for defined populations of Medicare fee-for-service patients. ACOs that manage to maintain or improve quality while achieving savings (ie, containing costs below a predefined population-wide spending benchmark) are eligible to receive a portion of the difference back from Medicare in the form of “shared savings”.

Similarly, hospital participation in Medicare’s bundled payment programs has grown over time. Most notably, more than 700 participants enrolled in the recently concluded Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative,2 Medicare’s largest bundled payment program over the past five years.3 Under BPCI, participants assumed financial accountability for the quality and costs of care for all Medicare patients triggering a qualifying “episode of care”. Participants that limit episode spending below a predefined benchmark without compromising quality were eligible for financial incentives.

As both ACOs and bundled payments grow in prominence and scale, they may increasingly overlap if patients attributed to ACOs receive care at bundled payment hospitals. Overlap could create synergies by increasing incentives to address shared processes (eg, discharge planning) or outcomes (eg, readmissions).4 An ACO focus on reducing hospital admissions could complement bundled payment efforts to increase hospital efficiency.

Conversely, Medicare’s approach to allocating savings and losses can penalize ACOs or bundled payment participants.3 For example, when a patient included in an MSSP ACO population receives episodic care at a hospital participating in BPCI, the historical costs of care for the hospital and the episode type, not the actual costs of care for that specific patient and his/her episode, are counted in the performance of the ACO. In other words, in these cases, the performance of the MSSP ACO is dependent on the historical spending at BPCI hospitals—despite it being out of ACO’s control and having little to do with the actual care its patients receive at BPCI hospitals—and MSSP ACOs cannot benefit from improvements over time. Therefore, MSSP ACOs may be functionally penalized if patients receive care at historically high-cost BPCI hospitals regardless of whether they have considerably improved the value of care delivered. As a corollary, Medicare rules involve a “claw back” stipulation in which savings are recouped from hospitals that participate in both BPCI and MSSP, effectively discouraging participation in both payment models.

Although these dynamics are complex, they highlight an intuitive point that has gained increasing awareness,5 ie, policymakers must understand the magnitude of overlap to evaluate the urgency in coordinating between the payment models. Our objective was to describe the extent of overlap and the characteristics of patients affected by it.

METHODS

We used 100% institutional Medicare claims, MSSP beneficiary attribution, and BPCI hospital data to identify fee-for-service beneficiaries attributed to MSSP and/or receiving care at BPCI hospitals for its 48 included episodes from the start of BPCI in 2013 quarter 4 through 2016 quarter 4.

We examined the trends in the number of episodes across the following three groups: MSSP-attributed patients hospitalized at BPCI hospitals for an episode included in BPCI (Overlap), MSSP-attributed patients hospitalized for that episode at non-BPCI hospitals (MSSP-only), and non-MSSP-attributed patients hospitalized at BPCI hospitals for a BPCI episode (BPCI-only). We used Medicare and United States Census Bureau data to compare groups with respect to sociodemographic (eg, age, sex, residence in a low-income area),6 clinical (eg, Elixhauser comorbidity index),7 and prior utilization (eg, skilled nursing facility discharge) characteristics.

Categorical and continuous variables were compared using logistic regression and one-way analysis of variance, respectively. Analyses were performed using Stata (StataCorp, College Station, Texas), version 15.0. Statistical tests were 2-tailed and significant at α = 0.05. This study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Pennsylvania.

RESULTS

The number of MSSP ACOs increased from 220 in 2013 to 432 in 2016. The number of BPCI hospitals increased from 9 to 389 over this period, peaking at 413 hospitals in 2015. Over our study period, a total of 243,392, 2,824,898, and 702,864 episodes occurred in the Overlap, ACO-only, and BPCI-only groups, respectively (Table). Among episodes, patients in the Overlap group generally showed lower severity than those in other groups, although the differences were small. The BPCI-only, MSSP-only, and Overlap groups also exhibited small differences with respect to other characteristics such as the proportion of patients with Medicare/Medicaid dual-eligibility (15% of individual vs 16% and 12%, respectively) and prior use of skilled nursing facilities (33% vs 34% vs 31%, respectively) and acute care hospitals (45% vs 41% vs 39%, respectively) (P < .001 for all).

The overall overlap facing MSSP patients (overlap as a proportion of all MSSP patients) increased from 0.3% at the end of 2013 to 10% at the end of 2016, whereas over the same period, overlap facing bundled payment patients (overlap as a proportion of all bundled payment patients) increased from 11.9% to 27% (Appendix Figure). Overlap facing MSSP ACOs varied according to episode type, ranging from 3% for both acute myocardial infarction and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease episodes to 18% for automatic implantable cardiac defibrillator episodes at the end of 2016. Similarly, overlap facing bundled payment patients varied from 21% for spinal fusion episodes to 32% for lower extremity joint replacement and automatic implantable cardiac defibrillator episodes.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe the sizable and growing overlap facing ACOs with attributed patients who receive care at bundled payment hospitals, as well as bundled payment hospitals that treat patients attributed to ACOs.

The major implication of our findings is that policymakers must address and anticipate forthcoming payment model overlap as a key policy priority. Given the emphasis on ACOs and bundled payments as payment models—for example, Medicare continues to implement both nationwide via the Next Generation ACO model8 and the recently launched BPCI-Advanced program9—policymakers urgently need insights about the extent of payment model overlap. In that context, it is notable that although we have evaluated MSSP and BPCI as flagship programs, true overlap may actually be greater once other programs are considered.

Several factors may underlie the differences in the magnitude of overlap facing bundled payment versus ACO patients. The models differ in how they identify relevant patient populations, with patients falling under bundled payments via hospitalization for certain episode types but patients falling under ACOs via attribution based on the plurality of primary care services. Furthermore, BPCI participation lagged behind MSSP participation in time, while also occurring disproportionately in areas with existing MSSP ACOs.

Given these findings, understanding the implications of overlap should be a priority for future research and policy strategies. Potential policy considerations should include revising cost accounting processes so that when ACO-attributed patients receive episodic care at bundled payment hospitals, actual rather than historical hospital costs are counted toward ACO cost performance. To encourage hospitals to assume more accountability over outcomes—the ostensible overarching goal of value-based payment reform—Medicare could elect not to recoup savings from hospitals in both payment models. Although such changes require careful accounting to protect Medicare from financial losses as it forgoes some savings achieved through payment reforms, this may be worthwhile if hospital engagement in both models yields synergies.

Importantly, any policy changes made to address program overlap would need to accommodate ongoing changes in ACO, bundled payments, and other payment programs. For example, Medicare overhauled MSSP in December 2018. Compared to the earlier rules, in which ACOs could avoid downside financial risk altogether via “upside only” arrangements for up to six years, new MSSP rules require all participants to assume downside risk after several years of participation. Separately, forthcoming payment reforms such as direct contracting10 may draw clinicians and hospitals previously not participating in either Medicare fee-for-service or value-based payment models into payment reform. These factors may affect overlap in unpredictable ways (eg, they may increase the overlap by increasing the number of patients whose care is covered by different payment models or they may decrease overlap by raising the financial stakes of payment reforms to a degree that organizations drop out altogether).

This study has limitations. First, generalizability is limited by the fact that our analysis did not include bundled payment episodes assigned to physician group participants in BPCI or hospitals in mandatory joint replacement bundles under the Medicare Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement model.11 Second, although this study provides the first description of overlap between ACO and bundled payment programs, it was descriptive in nature. Future research is needed to evaluate the impact of overlap on clinical, quality, and cost outcomes. This is particularly important because although we observed only small differences in patient characteristics among MSSP-only, BPCI-only, and Overlap groups, characteristics could change differentially over time. Payment reforms must be carefully monitored for potentially unintended consequences that could arise from differential changes in patient characteristics (eg, cherry-picking behavior that is disadvantageous to vulnerable individuals).

Nonetheless, this study underscores the importance and extent of overlap and the urgency to consider policy measures to coordinate between the payment models.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank research assistance from Sandra Vanderslice who did not receive any compensation for her work. This research was supported in part by The Commonwealth Fund. Rachel Werner was supported in part by K24-AG047908 from the NIA.

Voluntary accountable care organizations (ACOs) and bundled payments have concurrently become cornerstone strategies in Medicare’s shift from volume-based fee-for-service toward value-based payment.

Physician practice and hospital participation in Medicare’s largest ACO model, the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP),1 grew to include 561 organizations in 2018. Under MSSP, participants assume financial accountability for the global quality and costs of care for defined populations of Medicare fee-for-service patients. ACOs that manage to maintain or improve quality while achieving savings (ie, containing costs below a predefined population-wide spending benchmark) are eligible to receive a portion of the difference back from Medicare in the form of “shared savings”.

Similarly, hospital participation in Medicare’s bundled payment programs has grown over time. Most notably, more than 700 participants enrolled in the recently concluded Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative,2 Medicare’s largest bundled payment program over the past five years.3 Under BPCI, participants assumed financial accountability for the quality and costs of care for all Medicare patients triggering a qualifying “episode of care”. Participants that limit episode spending below a predefined benchmark without compromising quality were eligible for financial incentives.

As both ACOs and bundled payments grow in prominence and scale, they may increasingly overlap if patients attributed to ACOs receive care at bundled payment hospitals. Overlap could create synergies by increasing incentives to address shared processes (eg, discharge planning) or outcomes (eg, readmissions).4 An ACO focus on reducing hospital admissions could complement bundled payment efforts to increase hospital efficiency.

Conversely, Medicare’s approach to allocating savings and losses can penalize ACOs or bundled payment participants.3 For example, when a patient included in an MSSP ACO population receives episodic care at a hospital participating in BPCI, the historical costs of care for the hospital and the episode type, not the actual costs of care for that specific patient and his/her episode, are counted in the performance of the ACO. In other words, in these cases, the performance of the MSSP ACO is dependent on the historical spending at BPCI hospitals—despite it being out of ACO’s control and having little to do with the actual care its patients receive at BPCI hospitals—and MSSP ACOs cannot benefit from improvements over time. Therefore, MSSP ACOs may be functionally penalized if patients receive care at historically high-cost BPCI hospitals regardless of whether they have considerably improved the value of care delivered. As a corollary, Medicare rules involve a “claw back” stipulation in which savings are recouped from hospitals that participate in both BPCI and MSSP, effectively discouraging participation in both payment models.

Although these dynamics are complex, they highlight an intuitive point that has gained increasing awareness,5 ie, policymakers must understand the magnitude of overlap to evaluate the urgency in coordinating between the payment models. Our objective was to describe the extent of overlap and the characteristics of patients affected by it.

METHODS

We used 100% institutional Medicare claims, MSSP beneficiary attribution, and BPCI hospital data to identify fee-for-service beneficiaries attributed to MSSP and/or receiving care at BPCI hospitals for its 48 included episodes from the start of BPCI in 2013 quarter 4 through 2016 quarter 4.

We examined the trends in the number of episodes across the following three groups: MSSP-attributed patients hospitalized at BPCI hospitals for an episode included in BPCI (Overlap), MSSP-attributed patients hospitalized for that episode at non-BPCI hospitals (MSSP-only), and non-MSSP-attributed patients hospitalized at BPCI hospitals for a BPCI episode (BPCI-only). We used Medicare and United States Census Bureau data to compare groups with respect to sociodemographic (eg, age, sex, residence in a low-income area),6 clinical (eg, Elixhauser comorbidity index),7 and prior utilization (eg, skilled nursing facility discharge) characteristics.

Categorical and continuous variables were compared using logistic regression and one-way analysis of variance, respectively. Analyses were performed using Stata (StataCorp, College Station, Texas), version 15.0. Statistical tests were 2-tailed and significant at α = 0.05. This study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Pennsylvania.

RESULTS

The number of MSSP ACOs increased from 220 in 2013 to 432 in 2016. The number of BPCI hospitals increased from 9 to 389 over this period, peaking at 413 hospitals in 2015. Over our study period, a total of 243,392, 2,824,898, and 702,864 episodes occurred in the Overlap, ACO-only, and BPCI-only groups, respectively (Table). Among episodes, patients in the Overlap group generally showed lower severity than those in other groups, although the differences were small. The BPCI-only, MSSP-only, and Overlap groups also exhibited small differences with respect to other characteristics such as the proportion of patients with Medicare/Medicaid dual-eligibility (15% of individual vs 16% and 12%, respectively) and prior use of skilled nursing facilities (33% vs 34% vs 31%, respectively) and acute care hospitals (45% vs 41% vs 39%, respectively) (P < .001 for all).

The overall overlap facing MSSP patients (overlap as a proportion of all MSSP patients) increased from 0.3% at the end of 2013 to 10% at the end of 2016, whereas over the same period, overlap facing bundled payment patients (overlap as a proportion of all bundled payment patients) increased from 11.9% to 27% (Appendix Figure). Overlap facing MSSP ACOs varied according to episode type, ranging from 3% for both acute myocardial infarction and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease episodes to 18% for automatic implantable cardiac defibrillator episodes at the end of 2016. Similarly, overlap facing bundled payment patients varied from 21% for spinal fusion episodes to 32% for lower extremity joint replacement and automatic implantable cardiac defibrillator episodes.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe the sizable and growing overlap facing ACOs with attributed patients who receive care at bundled payment hospitals, as well as bundled payment hospitals that treat patients attributed to ACOs.

The major implication of our findings is that policymakers must address and anticipate forthcoming payment model overlap as a key policy priority. Given the emphasis on ACOs and bundled payments as payment models—for example, Medicare continues to implement both nationwide via the Next Generation ACO model8 and the recently launched BPCI-Advanced program9—policymakers urgently need insights about the extent of payment model overlap. In that context, it is notable that although we have evaluated MSSP and BPCI as flagship programs, true overlap may actually be greater once other programs are considered.

Several factors may underlie the differences in the magnitude of overlap facing bundled payment versus ACO patients. The models differ in how they identify relevant patient populations, with patients falling under bundled payments via hospitalization for certain episode types but patients falling under ACOs via attribution based on the plurality of primary care services. Furthermore, BPCI participation lagged behind MSSP participation in time, while also occurring disproportionately in areas with existing MSSP ACOs.

Given these findings, understanding the implications of overlap should be a priority for future research and policy strategies. Potential policy considerations should include revising cost accounting processes so that when ACO-attributed patients receive episodic care at bundled payment hospitals, actual rather than historical hospital costs are counted toward ACO cost performance. To encourage hospitals to assume more accountability over outcomes—the ostensible overarching goal of value-based payment reform—Medicare could elect not to recoup savings from hospitals in both payment models. Although such changes require careful accounting to protect Medicare from financial losses as it forgoes some savings achieved through payment reforms, this may be worthwhile if hospital engagement in both models yields synergies.

Importantly, any policy changes made to address program overlap would need to accommodate ongoing changes in ACO, bundled payments, and other payment programs. For example, Medicare overhauled MSSP in December 2018. Compared to the earlier rules, in which ACOs could avoid downside financial risk altogether via “upside only” arrangements for up to six years, new MSSP rules require all participants to assume downside risk after several years of participation. Separately, forthcoming payment reforms such as direct contracting10 may draw clinicians and hospitals previously not participating in either Medicare fee-for-service or value-based payment models into payment reform. These factors may affect overlap in unpredictable ways (eg, they may increase the overlap by increasing the number of patients whose care is covered by different payment models or they may decrease overlap by raising the financial stakes of payment reforms to a degree that organizations drop out altogether).

This study has limitations. First, generalizability is limited by the fact that our analysis did not include bundled payment episodes assigned to physician group participants in BPCI or hospitals in mandatory joint replacement bundles under the Medicare Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement model.11 Second, although this study provides the first description of overlap between ACO and bundled payment programs, it was descriptive in nature. Future research is needed to evaluate the impact of overlap on clinical, quality, and cost outcomes. This is particularly important because although we observed only small differences in patient characteristics among MSSP-only, BPCI-only, and Overlap groups, characteristics could change differentially over time. Payment reforms must be carefully monitored for potentially unintended consequences that could arise from differential changes in patient characteristics (eg, cherry-picking behavior that is disadvantageous to vulnerable individuals).

Nonetheless, this study underscores the importance and extent of overlap and the urgency to consider policy measures to coordinate between the payment models.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank research assistance from Sandra Vanderslice who did not receive any compensation for her work. This research was supported in part by The Commonwealth Fund. Rachel Werner was supported in part by K24-AG047908 from the NIA.

1. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Shared Savings Program. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-For-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/index.html. Accessed July 22, 2019.

2. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) Initiative: General Information. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bundled-payments/. Accessed July 22, 2019.

3. Mechanic RE. When new Medicare payment systems collide. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(18):1706-1709. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1601464.

4. Ryan AM, Krinsky S, Adler-Milstein J, Damberg CL, Maurer KA, Hollingsworth JM. Association between hospitals’ engagement in value-based reforms and readmission reduction in the hospital readmission reduction program. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(6):863-868. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0518.

5. Liao JM, Dykstra SE, Werner RM, Navathe AS. BPCI Advanced will further emphasize the need to address overlap between bundled payments and accountable care organizations. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20180409.159181/full/. Accessed May 14, 2019.

6. Census Bureau. United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/. Accessed May 14, 2018.

7. van Walraven C, Austin PC, Jennings A, Quan H, Forster AJ. A modification of the elixhauser comorbidity measures into a point system for hospital death using administrative data. Med Care. 2009;47(6):626-633. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819432e5.

8. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Next, Generation ACO Model. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/next-generation-aco-model/. Accessed July 22, 2019.

9. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. BPCI Advanced. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bpci-advanced. Accessed July 22, 2019.

10. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Direct Contracting. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/direct-contracting. Accessed July 22, 2019.

11. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Model. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/CJR. Accessed July 22, 2019.

1. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Shared Savings Program. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-For-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/index.html. Accessed July 22, 2019.

2. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) Initiative: General Information. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bundled-payments/. Accessed July 22, 2019.

3. Mechanic RE. When new Medicare payment systems collide. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(18):1706-1709. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1601464.

4. Ryan AM, Krinsky S, Adler-Milstein J, Damberg CL, Maurer KA, Hollingsworth JM. Association between hospitals’ engagement in value-based reforms and readmission reduction in the hospital readmission reduction program. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(6):863-868. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0518.

5. Liao JM, Dykstra SE, Werner RM, Navathe AS. BPCI Advanced will further emphasize the need to address overlap between bundled payments and accountable care organizations. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20180409.159181/full/. Accessed May 14, 2019.

6. Census Bureau. United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/. Accessed May 14, 2018.

7. van Walraven C, Austin PC, Jennings A, Quan H, Forster AJ. A modification of the elixhauser comorbidity measures into a point system for hospital death using administrative data. Med Care. 2009;47(6):626-633. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819432e5.

8. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Next, Generation ACO Model. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/next-generation-aco-model/. Accessed July 22, 2019.

9. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. BPCI Advanced. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bpci-advanced. Accessed July 22, 2019.

10. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Direct Contracting. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/direct-contracting. Accessed July 22, 2019.

11. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Model. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/CJR. Accessed July 22, 2019.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine