User login

Angry, inattentive, and sidelined

CASE Angry and depressed

Y is a 16-year-old male who presents with his mother to our clinic for medication evaluation because of anger issues and problems learning in school. He says he has been feeling depressed for several months and noticed significant irritability. Y sleeps excessively, sometimes for more than 12 hours a day, and eats more than he usually does. He reports feeling hopeless, helpless, and guilty for letting his family down. Y, who is in the 10th grade, acknowledges trouble focusing and concentrating but attributed this to a previous diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). He stopped taking his stimulant medication several months ago because he did not like taking it. He denies thoughts of self-harm or thinking about death.

Y’s mother reports that her son had been athletic but had to stop playing football because he has had 5 concussions. Y’s inability to play sports appears to be a precipitating factor in his decline in mood (Box). He had his first concussion at age 13; the last one was several months before his presenting to the clinic. Y experienced loss of consciousness and unsteady gait after his concussions and was hospitalized for some of them. Y says his life goals are “playing sports and being a marine,” which may be compromised because of his head injuries.

His mother reports Y is having more anger outbursts and says his personality is changing. Y viewed this change as just being more assertive and fails to see that others may be scared by his behavior. He is getting into more fights at school and is more impulsive and unpredictable, according to his mother. Y is struggling in school with cognitive deficits and memory problems; his grade point average (GPA) drops from 3.5 to 0.3 over several months. He had been homeschooled initially because of uncontrolled impulsivity and aggression, but was reintegrated to public school. Y has a history of a mathematics disorder but had done well without school accommodations before the head injuries. Lack of access to his peers and poor self-esteem because of his declining grades are making his mood worse. He denies a history of substance use and his urine drug screen is negative.

Recently, Y’s grandfather, with whom he had been close, died and 2 friends were killed in car accidents in the last few years. Y has no history of psychiatric hospitalization. He had seen a psychotherapist for depression. He had been on lisdexamfetamine, 30 mg/d, citalopram, 10 mg/d, and an unknown dose of dextroamphetamine. He had no major medical comorbidities. He lives with his mother. His parents are separated but he has frequent contact with his father. His developmental history is unremarkable. There was a questionable family history of schizophrenia, “nervous breakdowns,” depression, and bipolar disorder. There was no family history of suicide.

On his initial mental status examination, Y appears to be his stated age and is dressed appropriately. He is well dressed, suggesting that he puts a lot of care into his personal appearance. He is alert and oriented. He is cooperative and has fair eye contact. His gait is normal and no motor abnormalities are evident. His speech is normal in rate, rhythm, and volume. He can remember events with great accuracy. He reports that his mood is depressed and “down.” His affect appears irritable and he has low frustration tolerance, especially towards his mother. He is easy to anger but is re-directable. He does not endorse thoughts of suicidality or harm to others. He denies auditory or visual hallucinations, and paranoia. He does not appear to be responding to internal stimuli. His judgment and insight are fair.

a) major depressive disorder

b) oppositional defiant disorder

c) bipolar disorder, most recent episode depressed

d) ADHD, untreated

e) post-concussion syndrome

The authors' observations

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) affects 1.7 to 3.8 million people in the United States. More than 473,000 children present to the emergency room annually with TBI, approximately 75% of whom are given a label of mild TBI in the United States.1-3 TBI patients present with varying degrees of problems ranging from headaches to cognitive deficits and death. Symptoms may be transient or permanent.4 Prepubescent children are at higher risk and are more likely to sustain permanent damage post-TBI, with problems in attention, executive functioning, memory, and cognition.5-7

Prognosis depends on severity of injury and environmental factors, including socioeconomic status, family dysfunction, and access to resources.8 Patients may present during the acute concussion phase with physical symptoms, such as headaches, nausea, vomiting, sensitivity to light and sounds, and memory deficits, and psychiatric complaints such as anger, irritability, and mood swings. Symptoms may persist post-concussion, leading to problems in personal relationships and social and occupational functioning, and neuropsychiatric manifestations, including changes in personality, depression, suicidal thoughts, and substance dependence. As seen in this case, Y had neuropsychiatric manifestations after his TBI but other factors, such as his ADHD diagnosis and the death of his grandfather and friends, may have contributed to his presentation.

Up to one-half of children with brain injuries may be at increased risk for unfavorable behavioral outcomes, which include internalizing and externalizing presentations.9 These behavioral problems may emerge several years after the injury and often persist or get worse with time. Behavioral functioning before injury usually dictates long-term outcomes post injury. The American Academy of Neurology recently released guidelines for the assessment and treatment of athletes with concussions (see Related Resources).

TREATMENT Restart medication

We restart Y on citalopram, 10 mg/d, which he tolerated in the past, and increase it to 20 mg/d after 4 days to address his depression and irritability. He also is restarted on lisdexamfetamine, 30 mg/d, for his ADHD. We give his mother the Child Behavior Checklist and Teacher’s Report Forms to gather additional collateral information. We ask Y to follow up in 1 month and we encourage him to continue seeing his psychotherapist.

a) neuropsychological testing

b) neurology referral

c) imaging studies

d) no testing

EVALUATION Testing

Although Y denies feeling depressed to the neuropsychologist, the examiner notes her concerns about his depression based on his mental status examination during testing.

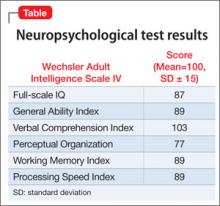

Neuropsychological testing reveals a discrepancy noted between normal verbal skills and perceptual intellectual skills that were in the borderline range (Table). Testing revealed results supporting executive dysfunction and distractibility, which are consistent with his history of ADHD. Y’s broad reading scores are in the 20th percentile and math scores in the 30th percentile. Although he has a history of a mathematics disorder, his reading deficits are considered a decline compared with his previous performance.

The authors' observations

Y is a 16-year-old male who presented with anger, depression, and academic problems. He had genetic loading with a questionable family history of schizophrenia, “nervous breakdowns,” depression, and bipolar disorder. Other than his concussions, Y was healthy, however, he had pre-morbid, untreated ADHD. He was doing well academically until his concussions, after which he started to see a steep decline in his grades. He was struggling with low self-esteem, which affected his mood. Multiple contributors perpetuated his difficulties, including, his inability to play sports; being home-schooled; removal from his friends; deaths of close friends and family; and a concern that his medical limitation to refrain from physical activities was affecting his career ambitions, contributing to his sense of hopelessness.

Y responded well to the stimulant and antidepressant, but it is important to note the increased risk of non-compliance in teenagers, even when they report seemingly minor side effects, despite doing well clinically. Y required frequent psychiatric follow up and repeat neuropsychological evaluation to monitor his progress.

OUTCOME Back on the playing field

At Y’s 1 month follow up, he reports feeling less depressed but citalopram, 20 mg/d, makes him feel “plain.” His GPA increases to 2.5 and he completes 10th grade. Lisdexamfetamine is titrated to 60 mg/d, he is focusing at school, and his anger is better controlled. Y’s mother is hesitant to change any medications because of her son’s overall improvement.

A few weeks before his next follow up appointment, Y’s mother calls stating that his depression is worse as he has not been taking citalopram because he doesn’t like how it makes him feel. He is started on fluoxetine, 10 mg/d. At his next appointment, Y says that he tolerates fluoxetine. His mood improves substantially and he is doing much better. Y’s mother says she feel that her son is more social, smiling more, and sleeping and eating better.

Several months after Y’s school performance, mood, and behaviors improve, his physicians give him permission to play non-contact sports. He is excited to play baseball. Because of his symptoms, we recommend continuing treating his ADHD and depressive symptoms and monitoring the need for medication. We discussed with Y nonpharmacotherapeutic options, including access to an individualized education plan at school, individual therapy, and formalized cognitive training.

Bottom Line

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) affects children and adults with long-term sequelae, which affects outcomes. Outcome is dependent on several risk factors. Many patients with TBI also suffer from neuropsychiatric symptoms that affect their functioning at home and in social and occupational settings. Those with premorbid psychiatric conditions need to be closely monitored because they may be at greater risk for problems with mood and executive function. Treatment should be targeted to individual complaints.

Related Resources

- Giza CC, Kutcher JS, Ashwal S, et al. Summary of evidence-based guideline update: evaluation and management of concussion in sports: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2013;80(24): 2250-2257.

- Reardon CL, Factor RM. Sport psychiatry: a systematic review of diagnosis and medical treatment of mental illness in athletes. Sports Med. 2010;40(11):961-980.

Drug Brand Names

Citalopram • Celexa Dextroamphetamine • Adderall

Fluoxetine • Prozac Lisdexamfetamine dimesylate • Vyvanse

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Jager TE, Weiss HB, Coben JH, et al. Traumatic brain injuries evaluated in US emergency departments, 1992-1994. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(2):134-140.

2. Committee on Quality Improvement American Academy of Pediatrics; Commission on Clinical Policies and Research American Academy of Family Physicians. The management of minor closed head injury in children. Pediatrics. 1999;104(6):1407-1415.

3. Koepsell TD, Rivara FP, Vavilala MS, et al. Incidence and descriptive epidemiologic features of traumatic brain injury in King County, Washington. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):946-954.

4. Sahler CS, Greenwald BD. Traumatic brain injury in sports: a review [published online July 9, 2012]. Rehabil Res Pract. 2012;2012:659652. doi: 10.1155/2012/659652.

5. Crowe L, Babl F, Anderson V, et al. The epidemiology of paediatric head injuries: data from a referral centre in Victoria, Australia. J Paediatr Child Health. 2009;45(6):346-350.

6. Anderson V, Catroppa C, Morse S, et al. Intellectual outcome from preschool traumatic brain injury: a 5-year prospective, longitudinal study. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):e1064-1071.

7. Jaffe KM, Fay GC, Polissar NL, et al. Severity of pediatric traumatic brain injury and neurobehavioral recovery at one year—a cohort study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993; 74(6):587-595.

8. Anderson VA, Catroppa C, Dudgeon P, et al. Understanding predictors of functional recovery and outcome 30 months following early childhood head injury. Neuropsychology. 2006;20(1):42-57.

9. Li L, Liu J. The effect of pediatric traumatic brain injury on behavioral outcomes: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55(1):37-45.

CASE Angry and depressed

Y is a 16-year-old male who presents with his mother to our clinic for medication evaluation because of anger issues and problems learning in school. He says he has been feeling depressed for several months and noticed significant irritability. Y sleeps excessively, sometimes for more than 12 hours a day, and eats more than he usually does. He reports feeling hopeless, helpless, and guilty for letting his family down. Y, who is in the 10th grade, acknowledges trouble focusing and concentrating but attributed this to a previous diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). He stopped taking his stimulant medication several months ago because he did not like taking it. He denies thoughts of self-harm or thinking about death.

Y’s mother reports that her son had been athletic but had to stop playing football because he has had 5 concussions. Y’s inability to play sports appears to be a precipitating factor in his decline in mood (Box). He had his first concussion at age 13; the last one was several months before his presenting to the clinic. Y experienced loss of consciousness and unsteady gait after his concussions and was hospitalized for some of them. Y says his life goals are “playing sports and being a marine,” which may be compromised because of his head injuries.

His mother reports Y is having more anger outbursts and says his personality is changing. Y viewed this change as just being more assertive and fails to see that others may be scared by his behavior. He is getting into more fights at school and is more impulsive and unpredictable, according to his mother. Y is struggling in school with cognitive deficits and memory problems; his grade point average (GPA) drops from 3.5 to 0.3 over several months. He had been homeschooled initially because of uncontrolled impulsivity and aggression, but was reintegrated to public school. Y has a history of a mathematics disorder but had done well without school accommodations before the head injuries. Lack of access to his peers and poor self-esteem because of his declining grades are making his mood worse. He denies a history of substance use and his urine drug screen is negative.

Recently, Y’s grandfather, with whom he had been close, died and 2 friends were killed in car accidents in the last few years. Y has no history of psychiatric hospitalization. He had seen a psychotherapist for depression. He had been on lisdexamfetamine, 30 mg/d, citalopram, 10 mg/d, and an unknown dose of dextroamphetamine. He had no major medical comorbidities. He lives with his mother. His parents are separated but he has frequent contact with his father. His developmental history is unremarkable. There was a questionable family history of schizophrenia, “nervous breakdowns,” depression, and bipolar disorder. There was no family history of suicide.

On his initial mental status examination, Y appears to be his stated age and is dressed appropriately. He is well dressed, suggesting that he puts a lot of care into his personal appearance. He is alert and oriented. He is cooperative and has fair eye contact. His gait is normal and no motor abnormalities are evident. His speech is normal in rate, rhythm, and volume. He can remember events with great accuracy. He reports that his mood is depressed and “down.” His affect appears irritable and he has low frustration tolerance, especially towards his mother. He is easy to anger but is re-directable. He does not endorse thoughts of suicidality or harm to others. He denies auditory or visual hallucinations, and paranoia. He does not appear to be responding to internal stimuli. His judgment and insight are fair.

a) major depressive disorder

b) oppositional defiant disorder

c) bipolar disorder, most recent episode depressed

d) ADHD, untreated

e) post-concussion syndrome

The authors' observations

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) affects 1.7 to 3.8 million people in the United States. More than 473,000 children present to the emergency room annually with TBI, approximately 75% of whom are given a label of mild TBI in the United States.1-3 TBI patients present with varying degrees of problems ranging from headaches to cognitive deficits and death. Symptoms may be transient or permanent.4 Prepubescent children are at higher risk and are more likely to sustain permanent damage post-TBI, with problems in attention, executive functioning, memory, and cognition.5-7

Prognosis depends on severity of injury and environmental factors, including socioeconomic status, family dysfunction, and access to resources.8 Patients may present during the acute concussion phase with physical symptoms, such as headaches, nausea, vomiting, sensitivity to light and sounds, and memory deficits, and psychiatric complaints such as anger, irritability, and mood swings. Symptoms may persist post-concussion, leading to problems in personal relationships and social and occupational functioning, and neuropsychiatric manifestations, including changes in personality, depression, suicidal thoughts, and substance dependence. As seen in this case, Y had neuropsychiatric manifestations after his TBI but other factors, such as his ADHD diagnosis and the death of his grandfather and friends, may have contributed to his presentation.

Up to one-half of children with brain injuries may be at increased risk for unfavorable behavioral outcomes, which include internalizing and externalizing presentations.9 These behavioral problems may emerge several years after the injury and often persist or get worse with time. Behavioral functioning before injury usually dictates long-term outcomes post injury. The American Academy of Neurology recently released guidelines for the assessment and treatment of athletes with concussions (see Related Resources).

TREATMENT Restart medication

We restart Y on citalopram, 10 mg/d, which he tolerated in the past, and increase it to 20 mg/d after 4 days to address his depression and irritability. He also is restarted on lisdexamfetamine, 30 mg/d, for his ADHD. We give his mother the Child Behavior Checklist and Teacher’s Report Forms to gather additional collateral information. We ask Y to follow up in 1 month and we encourage him to continue seeing his psychotherapist.

a) neuropsychological testing

b) neurology referral

c) imaging studies

d) no testing

EVALUATION Testing

Although Y denies feeling depressed to the neuropsychologist, the examiner notes her concerns about his depression based on his mental status examination during testing.

Neuropsychological testing reveals a discrepancy noted between normal verbal skills and perceptual intellectual skills that were in the borderline range (Table). Testing revealed results supporting executive dysfunction and distractibility, which are consistent with his history of ADHD. Y’s broad reading scores are in the 20th percentile and math scores in the 30th percentile. Although he has a history of a mathematics disorder, his reading deficits are considered a decline compared with his previous performance.

The authors' observations

Y is a 16-year-old male who presented with anger, depression, and academic problems. He had genetic loading with a questionable family history of schizophrenia, “nervous breakdowns,” depression, and bipolar disorder. Other than his concussions, Y was healthy, however, he had pre-morbid, untreated ADHD. He was doing well academically until his concussions, after which he started to see a steep decline in his grades. He was struggling with low self-esteem, which affected his mood. Multiple contributors perpetuated his difficulties, including, his inability to play sports; being home-schooled; removal from his friends; deaths of close friends and family; and a concern that his medical limitation to refrain from physical activities was affecting his career ambitions, contributing to his sense of hopelessness.

Y responded well to the stimulant and antidepressant, but it is important to note the increased risk of non-compliance in teenagers, even when they report seemingly minor side effects, despite doing well clinically. Y required frequent psychiatric follow up and repeat neuropsychological evaluation to monitor his progress.

OUTCOME Back on the playing field

At Y’s 1 month follow up, he reports feeling less depressed but citalopram, 20 mg/d, makes him feel “plain.” His GPA increases to 2.5 and he completes 10th grade. Lisdexamfetamine is titrated to 60 mg/d, he is focusing at school, and his anger is better controlled. Y’s mother is hesitant to change any medications because of her son’s overall improvement.

A few weeks before his next follow up appointment, Y’s mother calls stating that his depression is worse as he has not been taking citalopram because he doesn’t like how it makes him feel. He is started on fluoxetine, 10 mg/d. At his next appointment, Y says that he tolerates fluoxetine. His mood improves substantially and he is doing much better. Y’s mother says she feel that her son is more social, smiling more, and sleeping and eating better.

Several months after Y’s school performance, mood, and behaviors improve, his physicians give him permission to play non-contact sports. He is excited to play baseball. Because of his symptoms, we recommend continuing treating his ADHD and depressive symptoms and monitoring the need for medication. We discussed with Y nonpharmacotherapeutic options, including access to an individualized education plan at school, individual therapy, and formalized cognitive training.

Bottom Line

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) affects children and adults with long-term sequelae, which affects outcomes. Outcome is dependent on several risk factors. Many patients with TBI also suffer from neuropsychiatric symptoms that affect their functioning at home and in social and occupational settings. Those with premorbid psychiatric conditions need to be closely monitored because they may be at greater risk for problems with mood and executive function. Treatment should be targeted to individual complaints.

Related Resources

- Giza CC, Kutcher JS, Ashwal S, et al. Summary of evidence-based guideline update: evaluation and management of concussion in sports: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2013;80(24): 2250-2257.

- Reardon CL, Factor RM. Sport psychiatry: a systematic review of diagnosis and medical treatment of mental illness in athletes. Sports Med. 2010;40(11):961-980.

Drug Brand Names

Citalopram • Celexa Dextroamphetamine • Adderall

Fluoxetine • Prozac Lisdexamfetamine dimesylate • Vyvanse

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE Angry and depressed

Y is a 16-year-old male who presents with his mother to our clinic for medication evaluation because of anger issues and problems learning in school. He says he has been feeling depressed for several months and noticed significant irritability. Y sleeps excessively, sometimes for more than 12 hours a day, and eats more than he usually does. He reports feeling hopeless, helpless, and guilty for letting his family down. Y, who is in the 10th grade, acknowledges trouble focusing and concentrating but attributed this to a previous diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). He stopped taking his stimulant medication several months ago because he did not like taking it. He denies thoughts of self-harm or thinking about death.

Y’s mother reports that her son had been athletic but had to stop playing football because he has had 5 concussions. Y’s inability to play sports appears to be a precipitating factor in his decline in mood (Box). He had his first concussion at age 13; the last one was several months before his presenting to the clinic. Y experienced loss of consciousness and unsteady gait after his concussions and was hospitalized for some of them. Y says his life goals are “playing sports and being a marine,” which may be compromised because of his head injuries.

His mother reports Y is having more anger outbursts and says his personality is changing. Y viewed this change as just being more assertive and fails to see that others may be scared by his behavior. He is getting into more fights at school and is more impulsive and unpredictable, according to his mother. Y is struggling in school with cognitive deficits and memory problems; his grade point average (GPA) drops from 3.5 to 0.3 over several months. He had been homeschooled initially because of uncontrolled impulsivity and aggression, but was reintegrated to public school. Y has a history of a mathematics disorder but had done well without school accommodations before the head injuries. Lack of access to his peers and poor self-esteem because of his declining grades are making his mood worse. He denies a history of substance use and his urine drug screen is negative.

Recently, Y’s grandfather, with whom he had been close, died and 2 friends were killed in car accidents in the last few years. Y has no history of psychiatric hospitalization. He had seen a psychotherapist for depression. He had been on lisdexamfetamine, 30 mg/d, citalopram, 10 mg/d, and an unknown dose of dextroamphetamine. He had no major medical comorbidities. He lives with his mother. His parents are separated but he has frequent contact with his father. His developmental history is unremarkable. There was a questionable family history of schizophrenia, “nervous breakdowns,” depression, and bipolar disorder. There was no family history of suicide.

On his initial mental status examination, Y appears to be his stated age and is dressed appropriately. He is well dressed, suggesting that he puts a lot of care into his personal appearance. He is alert and oriented. He is cooperative and has fair eye contact. His gait is normal and no motor abnormalities are evident. His speech is normal in rate, rhythm, and volume. He can remember events with great accuracy. He reports that his mood is depressed and “down.” His affect appears irritable and he has low frustration tolerance, especially towards his mother. He is easy to anger but is re-directable. He does not endorse thoughts of suicidality or harm to others. He denies auditory or visual hallucinations, and paranoia. He does not appear to be responding to internal stimuli. His judgment and insight are fair.

a) major depressive disorder

b) oppositional defiant disorder

c) bipolar disorder, most recent episode depressed

d) ADHD, untreated

e) post-concussion syndrome

The authors' observations

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) affects 1.7 to 3.8 million people in the United States. More than 473,000 children present to the emergency room annually with TBI, approximately 75% of whom are given a label of mild TBI in the United States.1-3 TBI patients present with varying degrees of problems ranging from headaches to cognitive deficits and death. Symptoms may be transient or permanent.4 Prepubescent children are at higher risk and are more likely to sustain permanent damage post-TBI, with problems in attention, executive functioning, memory, and cognition.5-7

Prognosis depends on severity of injury and environmental factors, including socioeconomic status, family dysfunction, and access to resources.8 Patients may present during the acute concussion phase with physical symptoms, such as headaches, nausea, vomiting, sensitivity to light and sounds, and memory deficits, and psychiatric complaints such as anger, irritability, and mood swings. Symptoms may persist post-concussion, leading to problems in personal relationships and social and occupational functioning, and neuropsychiatric manifestations, including changes in personality, depression, suicidal thoughts, and substance dependence. As seen in this case, Y had neuropsychiatric manifestations after his TBI but other factors, such as his ADHD diagnosis and the death of his grandfather and friends, may have contributed to his presentation.

Up to one-half of children with brain injuries may be at increased risk for unfavorable behavioral outcomes, which include internalizing and externalizing presentations.9 These behavioral problems may emerge several years after the injury and often persist or get worse with time. Behavioral functioning before injury usually dictates long-term outcomes post injury. The American Academy of Neurology recently released guidelines for the assessment and treatment of athletes with concussions (see Related Resources).

TREATMENT Restart medication

We restart Y on citalopram, 10 mg/d, which he tolerated in the past, and increase it to 20 mg/d after 4 days to address his depression and irritability. He also is restarted on lisdexamfetamine, 30 mg/d, for his ADHD. We give his mother the Child Behavior Checklist and Teacher’s Report Forms to gather additional collateral information. We ask Y to follow up in 1 month and we encourage him to continue seeing his psychotherapist.

a) neuropsychological testing

b) neurology referral

c) imaging studies

d) no testing

EVALUATION Testing

Although Y denies feeling depressed to the neuropsychologist, the examiner notes her concerns about his depression based on his mental status examination during testing.

Neuropsychological testing reveals a discrepancy noted between normal verbal skills and perceptual intellectual skills that were in the borderline range (Table). Testing revealed results supporting executive dysfunction and distractibility, which are consistent with his history of ADHD. Y’s broad reading scores are in the 20th percentile and math scores in the 30th percentile. Although he has a history of a mathematics disorder, his reading deficits are considered a decline compared with his previous performance.

The authors' observations

Y is a 16-year-old male who presented with anger, depression, and academic problems. He had genetic loading with a questionable family history of schizophrenia, “nervous breakdowns,” depression, and bipolar disorder. Other than his concussions, Y was healthy, however, he had pre-morbid, untreated ADHD. He was doing well academically until his concussions, after which he started to see a steep decline in his grades. He was struggling with low self-esteem, which affected his mood. Multiple contributors perpetuated his difficulties, including, his inability to play sports; being home-schooled; removal from his friends; deaths of close friends and family; and a concern that his medical limitation to refrain from physical activities was affecting his career ambitions, contributing to his sense of hopelessness.

Y responded well to the stimulant and antidepressant, but it is important to note the increased risk of non-compliance in teenagers, even when they report seemingly minor side effects, despite doing well clinically. Y required frequent psychiatric follow up and repeat neuropsychological evaluation to monitor his progress.

OUTCOME Back on the playing field

At Y’s 1 month follow up, he reports feeling less depressed but citalopram, 20 mg/d, makes him feel “plain.” His GPA increases to 2.5 and he completes 10th grade. Lisdexamfetamine is titrated to 60 mg/d, he is focusing at school, and his anger is better controlled. Y’s mother is hesitant to change any medications because of her son’s overall improvement.

A few weeks before his next follow up appointment, Y’s mother calls stating that his depression is worse as he has not been taking citalopram because he doesn’t like how it makes him feel. He is started on fluoxetine, 10 mg/d. At his next appointment, Y says that he tolerates fluoxetine. His mood improves substantially and he is doing much better. Y’s mother says she feel that her son is more social, smiling more, and sleeping and eating better.

Several months after Y’s school performance, mood, and behaviors improve, his physicians give him permission to play non-contact sports. He is excited to play baseball. Because of his symptoms, we recommend continuing treating his ADHD and depressive symptoms and monitoring the need for medication. We discussed with Y nonpharmacotherapeutic options, including access to an individualized education plan at school, individual therapy, and formalized cognitive training.

Bottom Line

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) affects children and adults with long-term sequelae, which affects outcomes. Outcome is dependent on several risk factors. Many patients with TBI also suffer from neuropsychiatric symptoms that affect their functioning at home and in social and occupational settings. Those with premorbid psychiatric conditions need to be closely monitored because they may be at greater risk for problems with mood and executive function. Treatment should be targeted to individual complaints.

Related Resources

- Giza CC, Kutcher JS, Ashwal S, et al. Summary of evidence-based guideline update: evaluation and management of concussion in sports: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2013;80(24): 2250-2257.

- Reardon CL, Factor RM. Sport psychiatry: a systematic review of diagnosis and medical treatment of mental illness in athletes. Sports Med. 2010;40(11):961-980.

Drug Brand Names

Citalopram • Celexa Dextroamphetamine • Adderall

Fluoxetine • Prozac Lisdexamfetamine dimesylate • Vyvanse

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Jager TE, Weiss HB, Coben JH, et al. Traumatic brain injuries evaluated in US emergency departments, 1992-1994. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(2):134-140.

2. Committee on Quality Improvement American Academy of Pediatrics; Commission on Clinical Policies and Research American Academy of Family Physicians. The management of minor closed head injury in children. Pediatrics. 1999;104(6):1407-1415.

3. Koepsell TD, Rivara FP, Vavilala MS, et al. Incidence and descriptive epidemiologic features of traumatic brain injury in King County, Washington. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):946-954.

4. Sahler CS, Greenwald BD. Traumatic brain injury in sports: a review [published online July 9, 2012]. Rehabil Res Pract. 2012;2012:659652. doi: 10.1155/2012/659652.

5. Crowe L, Babl F, Anderson V, et al. The epidemiology of paediatric head injuries: data from a referral centre in Victoria, Australia. J Paediatr Child Health. 2009;45(6):346-350.

6. Anderson V, Catroppa C, Morse S, et al. Intellectual outcome from preschool traumatic brain injury: a 5-year prospective, longitudinal study. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):e1064-1071.

7. Jaffe KM, Fay GC, Polissar NL, et al. Severity of pediatric traumatic brain injury and neurobehavioral recovery at one year—a cohort study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993; 74(6):587-595.

8. Anderson VA, Catroppa C, Dudgeon P, et al. Understanding predictors of functional recovery and outcome 30 months following early childhood head injury. Neuropsychology. 2006;20(1):42-57.

9. Li L, Liu J. The effect of pediatric traumatic brain injury on behavioral outcomes: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55(1):37-45.

1. Jager TE, Weiss HB, Coben JH, et al. Traumatic brain injuries evaluated in US emergency departments, 1992-1994. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(2):134-140.

2. Committee on Quality Improvement American Academy of Pediatrics; Commission on Clinical Policies and Research American Academy of Family Physicians. The management of minor closed head injury in children. Pediatrics. 1999;104(6):1407-1415.

3. Koepsell TD, Rivara FP, Vavilala MS, et al. Incidence and descriptive epidemiologic features of traumatic brain injury in King County, Washington. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):946-954.

4. Sahler CS, Greenwald BD. Traumatic brain injury in sports: a review [published online July 9, 2012]. Rehabil Res Pract. 2012;2012:659652. doi: 10.1155/2012/659652.

5. Crowe L, Babl F, Anderson V, et al. The epidemiology of paediatric head injuries: data from a referral centre in Victoria, Australia. J Paediatr Child Health. 2009;45(6):346-350.

6. Anderson V, Catroppa C, Morse S, et al. Intellectual outcome from preschool traumatic brain injury: a 5-year prospective, longitudinal study. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):e1064-1071.

7. Jaffe KM, Fay GC, Polissar NL, et al. Severity of pediatric traumatic brain injury and neurobehavioral recovery at one year—a cohort study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993; 74(6):587-595.

8. Anderson VA, Catroppa C, Dudgeon P, et al. Understanding predictors of functional recovery and outcome 30 months following early childhood head injury. Neuropsychology. 2006;20(1):42-57.

9. Li L, Liu J. The effect of pediatric traumatic brain injury on behavioral outcomes: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55(1):37-45.

A perplexing case of altered mental status

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

CASE: Agitated and paranoid

Mr. E, age 55, presents to the emergency department (ED) with a 2-week history of altered mental status (AMS). His wife reports, “He was normal one day and the next day he was not.” Mr. E also presents with sleep disturbance, decreased appetite and speech, and a 20-lb weight loss. His family reports no recent stressors or head trauma. Mr. E is agitated in the ED and receives a single dose of IV haloperidol, 5 mg. He exhibits paranoia and is afraid to get a CT scan. The medical team attempts a lumbar puncture (LP), but Mr. E does not cooperate.

His laboratory values are: potassium, 3.0 mEq/L; creatinine, 1.60 mg/dL; calcium, 10.6 mg/dL; thyroid-stimulating hormone, 0.177 IU/L; vitamin B12, >1500 pg/mL; folate, >20 ng/mL; and creatine kinase, 281 U/L. Urine drug screen is positive for benzodiazepines and opiates, neither of which was prescribed, and blood alcohol is negative.

Mr. E is admitted for further workup of AMS. His daughter-in-law states that Mr. E is an alcoholic and she is concerned that he may have mixed drugs and alcohol. The medical service starts Mr. E on empiric antimicrobials—vancomycin, ceftriaxone, and acyclovir—because of his AMS, and performs an LP to rule out intracranial pathology. His LP results are unremarkable.

Mr. E appears to be confused during psychiatric evaluation. He requests to be “hypnotized on a helicopter to find out what is wrong with me.” His wife states that Mr. E drank vodka daily but decreased his alcohol consumption after surgery 5 months ago. Before his current admission, he was drinking approximately half a glass of vodka every few days, according to his wife. Mr. E says he has no prior psychiatric admissions. During the mental status exam, his eye contact is poor, with latency of response to questions, thought blocking, and psychomotor retardation. He is alert, oriented to time, place, and person, and cooperative. He cannot concentrate or focus during the interview. He denies suicidal or homicidal ideation.

The authors’ observations

Mr. E appeared to be delirious, as evidenced by the sudden onset of waxing and waning changes in consciousness, attention deficits, and cognition. He also had a history of daily alcohol use and decreased his alcohol intake after a surgery 5 months ago, which puts him at risk for Wernicke’s encephalopathy.1-3 The type of surgery and whether he received adequate thiamine supplementation at that time was unclear. Because Mr. E is older, he has a higher risk of mortality and morbidity from delirium.4,5 We started Mr. E on quetiapine, 50 mg/d, for delirium and an IV lorazepam taper, starting at 2 mg every 8 hours, because the extent of his alcohol and benzodiazepine use was unclear—we weren’t sure how forthcoming he was about his alcohol use. He received IV thiamine supplementation followed by oral thiamine, 100 mg/d.

The authors’ recommendations

We requested a neurology consult, EEG, CSF cultures, and brain MRI (Table 1).6 EEG, chest radiography, thyroid scan, and CT scan were normal and MRI showed no acute intracranial process. However, there was a redemonstration of increased T1 signal seen within the bilateral basal ganglia and relative diminutive appearance to the bilateral mamillary bodies, which suggests possible liver disease and/or alcohol abuse. These findings were unchanged from an MRI Mr. E received 10 years ago, were consistent with his history of alcohol abuse, and may indicate an underlying predisposition to delirium. A CT scan of the abdomen showed hepatic cirrhosis with prominent, tortuous vessels of the upper abdomen, subtle ill-defined hypodensity of the anterior aspect of the liver, and an enlarged spleen.

Mr. E’s mental functioning did not improve with quetiapine and lorazepam. Further evaluation revealed a negative human immunodeficiency virus test and normal heavy metals, ammonia, ceruloplasmin, and thiamine. We suspected limbic encephalitis because of Mr. E’s memory problems and behavioral and psychiatric manifestations,7 but CSF was unremarkable and limbic encephalitis workup of CSF and paraneoplastic antibody panel were negative.

Mr. E’s primary care physician stated that at an appointment 1 month ago, Mr. E was alert, oriented, and conversational with normal thought processing. At that time he had presented with rectal bleeding, occult blood in his stool, and an unintentional 25-lb weight loss over 2 months. It was not clear if his weight loss was caused by poor nutrition—which is common among chronic alcoholics—or an occult disease process.

After 10 days, Mr. E was discharged home from the medicine service with no clear cause of his AMS.

Table 1

Suggested workup for altered mental status

| Complete blood count, basic metabolic profile, creatine kinase |

| Thyroid-stimulating hormone, thyroid scan |

| Vitamin B12, folate, thiamine |

| Blood alcohol, urine drug screen |

| Urine analysis and cultures |

| Lumbar puncture—CSF staining and cultures |

| Chest radiography |

| CT and MRI scan of brain |

| Electroencephalography |

| Neuropsychiatric testing |

| CSF: cerebrospinal fluid Source: Reference 6 |

EVALUATION: Worsening behavior

One week later, Mr. E presents to the ED with continued AMS and worsening behavior at home. Two days ago, he attempted to strangle his dog and cut himself with a knife. His paranoia was worsening and his oral intake continued to decrease. In the ED, Mr. E does not want a chest radiograph because, “I don’t like radiation contaminating my body”; his family stated that he had been suspicious of radiography all of his life. He receives empiric ceftriaxone because of a possible urinary tract infection. Urine culture is positive for Pseudomonas aeruginosa and he is switched to ciprofloxacin. Mr. E is admitted for further workup.

Mr. E’s mother states, “I think this change in behavior is related to my son drinking alcohol for 20 years. This is exactly how he acted when he was on drugs. I think he is having a flashback.” She also reports her son purchased multiple chemicals—the details of which are unclear—that he left lying around the house.

His wife says that after discharge a week ago, Mr. E was stable for 1 or 2 days and then “he started going downhill.” He became more paranoid and he started talking about cameras watching him in his house. Mr. E took quetiapine, 50 mg/d, for a few days, then refused because he thought there was something in the medication. Mr. E’s family feels that at times he is responding to internal stimuli. He makes statements about his DNA being changed and reports that he has 2 wives and the wife in the room was not the real one, which suggests Capgras syndrome. His wife provides a home medication list that includes vitamin B complex, vitamins B12, E, and C, a multivitamin, zinc, magnesium, fish oil, garlic, calcium, glucosamine, chondroitin, herbal supplements, and gingko. The psychiatry team recommends switching from quetiapine to olanzapine, 15 mg/d, because Mr. E was paranoid about taking quetiapine.

We determine that Mr. E does not have medical decision-making capacity.

Because his symptoms do not improve, Mr. E is transferred to the psychiatric intensive care unit. His mental status shows little change while there. Neuropsychiatric testing shows only “cognitive deficits.” He shows signs consistent with neurologic dysfunction in terms of stimulus-bound responding and perseveration, which is compatible with the bilateral basal ganglia lesion seen on MRI. However, some of his behaviors suggest psychiatric and motivationally driven or manipulative etiology. During this testing he was difficult to evaluate and needed to be convinced to engage. At times he was illogical and at other times he showed good focus and recall. It is difficult to draw more definitive conclusions and Mr. E is discharged home with minor improvement in his symptoms. He didn’t attend follow-up appointments. During a courtesy call a few months after his admission, his wife revealed that Mr. E had died after shooting himself. It is unclear if it was an accident or suicide.

The authors’ observations

Mr. E’s diagnosis remains unclear (for a summary of his clinical course, see Table 2). Although his initial presentation was consistent with delirium, the lack of an identifiable medical cause, prolonged time course, and lack of improvement with dopamine blocking agents suggest additional diagnoses such as Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome, rapidly progressive dementia, or a substance-induced disorder. He displayed paranoia and bizarre delusions, which would suggest a thought disorder. However, he also had a history of substance use. A few months after we saw Mr. E, “bath salt” (methylenedioxypyrovalerone) abuse gained national attention. Patients with bath salt intoxication present with confusion, paranoia, and behavioral disturbances as well as a prolonged course.8

Mr. E’s CT and MRI scans, history of alcohol use, and cirrhosis also point to Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome as an underlying diagnosis. It is unclear whether Mr. E experienced alcohol withdrawal and IV glucose without adequate thiamine replacement during a prior surgery. However, MRI findings were unchanged from a previous study 10 years ago.

It is puzzling whether Mr. E’s AMS was a first psychotic break, a result of drug and alcohol use, rapidly progressing dementia, or another neurologic problem that we have not identified. Our tentative diagnosis was Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome because of his history of alcohol use and imaging findings.

Although we used a multidisciplinary team approach that included psychiatry, internal medicine, neurology, neuropsychology, and an aggressive and thorough workup, we could not establish a definitive diagnosis. Unsolved cases such as this can leave patients and clinicians frustrated and may lead to unfavorable outcomes. Additional resources such as a telephone call after the first missed appointment may have been warranted.

Table 2

Mr. E’s clinical course

| Symptoms | Treatment | |

|---|---|---|

| First ED visit | Agitation Confusion Sleep disturbance Decreased appetite and speech 20-lb weight loss | Empiric antimicrobials for possible meningitis Haloperidol for agitation Quetiapine for delirium Lorazepam taper Thiamine supplementation |

| Second ED visit | Violent behavior Worsening paranoia Responding to internal stimuli Mr. E believes he has 2 wives, but the wife in the room is not the real one, which suggests possible Capgras syndrome Cognitive deficits on mental status exam | Switch from ceftriaxone to ciprofloxacin for Pseudomonas aeruginosa Switch from quetiapine to olanzapine |

| ED: emergency department | ||

Related Resources

- Kaufman DM. Clinical neurology for psychiatrists. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2007.

- Sidhu KS, Balon R, Ajluni V, et al. Standard EEG and the difficult-to-assess mental status. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2009;21(2):103-108.

Drug Brand Names

- Acyclovir • Zovirax

- Ceftriaxone • Rocephin

- Ciprofloxacin • Cipro

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Lorazepam • Ativan

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Thiamine • Betaxin

- Vancomycin • Vancocin

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Jiang W, Gagliardi JP, Raj YP, et al. Acute psychotic disorder after gastric bypass surgery: differential diagnosis and treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):15-19.

2. Harrison RA, Vu T, Hunter AJ. Wernicke’s encephalopathy in a patient with schizophrenia. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(12):C8-C11.

3. Sechi GP, Serra A. Wernicke’s encephalopathy: new clinical settings and recent advances in diagnosis and treatment. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(5):442-455.

4. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with delirium. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(5 suppl):1-20.

5. Sharon KI, Fearing MA, Marcantonio RA. Delirium. In: Halter JB Ouslander JG, Tinetti ME, et al, eds. Hazzard’s geriatric medicine and gerontology. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2009:647–658.

6. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Delirium dementia, and amnestic and other cognitive disorders. In: Sadock BJ, Kaplan HI, Sadock VA. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007:319–372.

7. Ahmad SA, Archer HA, Rice CM, et al. Seronegative limbic encephalitis: case report, literature review and proposed treatment algorithm. Pract Neurol. 2011;11(6):355-361.

8. Ross EA, Watson M, Goldberger B. “Bath salts” intoxication. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(10):967-968.

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

CASE: Agitated and paranoid

Mr. E, age 55, presents to the emergency department (ED) with a 2-week history of altered mental status (AMS). His wife reports, “He was normal one day and the next day he was not.” Mr. E also presents with sleep disturbance, decreased appetite and speech, and a 20-lb weight loss. His family reports no recent stressors or head trauma. Mr. E is agitated in the ED and receives a single dose of IV haloperidol, 5 mg. He exhibits paranoia and is afraid to get a CT scan. The medical team attempts a lumbar puncture (LP), but Mr. E does not cooperate.

His laboratory values are: potassium, 3.0 mEq/L; creatinine, 1.60 mg/dL; calcium, 10.6 mg/dL; thyroid-stimulating hormone, 0.177 IU/L; vitamin B12, >1500 pg/mL; folate, >20 ng/mL; and creatine kinase, 281 U/L. Urine drug screen is positive for benzodiazepines and opiates, neither of which was prescribed, and blood alcohol is negative.

Mr. E is admitted for further workup of AMS. His daughter-in-law states that Mr. E is an alcoholic and she is concerned that he may have mixed drugs and alcohol. The medical service starts Mr. E on empiric antimicrobials—vancomycin, ceftriaxone, and acyclovir—because of his AMS, and performs an LP to rule out intracranial pathology. His LP results are unremarkable.

Mr. E appears to be confused during psychiatric evaluation. He requests to be “hypnotized on a helicopter to find out what is wrong with me.” His wife states that Mr. E drank vodka daily but decreased his alcohol consumption after surgery 5 months ago. Before his current admission, he was drinking approximately half a glass of vodka every few days, according to his wife. Mr. E says he has no prior psychiatric admissions. During the mental status exam, his eye contact is poor, with latency of response to questions, thought blocking, and psychomotor retardation. He is alert, oriented to time, place, and person, and cooperative. He cannot concentrate or focus during the interview. He denies suicidal or homicidal ideation.

The authors’ observations

Mr. E appeared to be delirious, as evidenced by the sudden onset of waxing and waning changes in consciousness, attention deficits, and cognition. He also had a history of daily alcohol use and decreased his alcohol intake after a surgery 5 months ago, which puts him at risk for Wernicke’s encephalopathy.1-3 The type of surgery and whether he received adequate thiamine supplementation at that time was unclear. Because Mr. E is older, he has a higher risk of mortality and morbidity from delirium.4,5 We started Mr. E on quetiapine, 50 mg/d, for delirium and an IV lorazepam taper, starting at 2 mg every 8 hours, because the extent of his alcohol and benzodiazepine use was unclear—we weren’t sure how forthcoming he was about his alcohol use. He received IV thiamine supplementation followed by oral thiamine, 100 mg/d.

The authors’ recommendations

We requested a neurology consult, EEG, CSF cultures, and brain MRI (Table 1).6 EEG, chest radiography, thyroid scan, and CT scan were normal and MRI showed no acute intracranial process. However, there was a redemonstration of increased T1 signal seen within the bilateral basal ganglia and relative diminutive appearance to the bilateral mamillary bodies, which suggests possible liver disease and/or alcohol abuse. These findings were unchanged from an MRI Mr. E received 10 years ago, were consistent with his history of alcohol abuse, and may indicate an underlying predisposition to delirium. A CT scan of the abdomen showed hepatic cirrhosis with prominent, tortuous vessels of the upper abdomen, subtle ill-defined hypodensity of the anterior aspect of the liver, and an enlarged spleen.

Mr. E’s mental functioning did not improve with quetiapine and lorazepam. Further evaluation revealed a negative human immunodeficiency virus test and normal heavy metals, ammonia, ceruloplasmin, and thiamine. We suspected limbic encephalitis because of Mr. E’s memory problems and behavioral and psychiatric manifestations,7 but CSF was unremarkable and limbic encephalitis workup of CSF and paraneoplastic antibody panel were negative.

Mr. E’s primary care physician stated that at an appointment 1 month ago, Mr. E was alert, oriented, and conversational with normal thought processing. At that time he had presented with rectal bleeding, occult blood in his stool, and an unintentional 25-lb weight loss over 2 months. It was not clear if his weight loss was caused by poor nutrition—which is common among chronic alcoholics—or an occult disease process.

After 10 days, Mr. E was discharged home from the medicine service with no clear cause of his AMS.

Table 1

Suggested workup for altered mental status

| Complete blood count, basic metabolic profile, creatine kinase |

| Thyroid-stimulating hormone, thyroid scan |

| Vitamin B12, folate, thiamine |

| Blood alcohol, urine drug screen |

| Urine analysis and cultures |

| Lumbar puncture—CSF staining and cultures |

| Chest radiography |

| CT and MRI scan of brain |

| Electroencephalography |

| Neuropsychiatric testing |

| CSF: cerebrospinal fluid Source: Reference 6 |

EVALUATION: Worsening behavior

One week later, Mr. E presents to the ED with continued AMS and worsening behavior at home. Two days ago, he attempted to strangle his dog and cut himself with a knife. His paranoia was worsening and his oral intake continued to decrease. In the ED, Mr. E does not want a chest radiograph because, “I don’t like radiation contaminating my body”; his family stated that he had been suspicious of radiography all of his life. He receives empiric ceftriaxone because of a possible urinary tract infection. Urine culture is positive for Pseudomonas aeruginosa and he is switched to ciprofloxacin. Mr. E is admitted for further workup.

Mr. E’s mother states, “I think this change in behavior is related to my son drinking alcohol for 20 years. This is exactly how he acted when he was on drugs. I think he is having a flashback.” She also reports her son purchased multiple chemicals—the details of which are unclear—that he left lying around the house.

His wife says that after discharge a week ago, Mr. E was stable for 1 or 2 days and then “he started going downhill.” He became more paranoid and he started talking about cameras watching him in his house. Mr. E took quetiapine, 50 mg/d, for a few days, then refused because he thought there was something in the medication. Mr. E’s family feels that at times he is responding to internal stimuli. He makes statements about his DNA being changed and reports that he has 2 wives and the wife in the room was not the real one, which suggests Capgras syndrome. His wife provides a home medication list that includes vitamin B complex, vitamins B12, E, and C, a multivitamin, zinc, magnesium, fish oil, garlic, calcium, glucosamine, chondroitin, herbal supplements, and gingko. The psychiatry team recommends switching from quetiapine to olanzapine, 15 mg/d, because Mr. E was paranoid about taking quetiapine.

We determine that Mr. E does not have medical decision-making capacity.

Because his symptoms do not improve, Mr. E is transferred to the psychiatric intensive care unit. His mental status shows little change while there. Neuropsychiatric testing shows only “cognitive deficits.” He shows signs consistent with neurologic dysfunction in terms of stimulus-bound responding and perseveration, which is compatible with the bilateral basal ganglia lesion seen on MRI. However, some of his behaviors suggest psychiatric and motivationally driven or manipulative etiology. During this testing he was difficult to evaluate and needed to be convinced to engage. At times he was illogical and at other times he showed good focus and recall. It is difficult to draw more definitive conclusions and Mr. E is discharged home with minor improvement in his symptoms. He didn’t attend follow-up appointments. During a courtesy call a few months after his admission, his wife revealed that Mr. E had died after shooting himself. It is unclear if it was an accident or suicide.

The authors’ observations

Mr. E’s diagnosis remains unclear (for a summary of his clinical course, see Table 2). Although his initial presentation was consistent with delirium, the lack of an identifiable medical cause, prolonged time course, and lack of improvement with dopamine blocking agents suggest additional diagnoses such as Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome, rapidly progressive dementia, or a substance-induced disorder. He displayed paranoia and bizarre delusions, which would suggest a thought disorder. However, he also had a history of substance use. A few months after we saw Mr. E, “bath salt” (methylenedioxypyrovalerone) abuse gained national attention. Patients with bath salt intoxication present with confusion, paranoia, and behavioral disturbances as well as a prolonged course.8

Mr. E’s CT and MRI scans, history of alcohol use, and cirrhosis also point to Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome as an underlying diagnosis. It is unclear whether Mr. E experienced alcohol withdrawal and IV glucose without adequate thiamine replacement during a prior surgery. However, MRI findings were unchanged from a previous study 10 years ago.

It is puzzling whether Mr. E’s AMS was a first psychotic break, a result of drug and alcohol use, rapidly progressing dementia, or another neurologic problem that we have not identified. Our tentative diagnosis was Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome because of his history of alcohol use and imaging findings.

Although we used a multidisciplinary team approach that included psychiatry, internal medicine, neurology, neuropsychology, and an aggressive and thorough workup, we could not establish a definitive diagnosis. Unsolved cases such as this can leave patients and clinicians frustrated and may lead to unfavorable outcomes. Additional resources such as a telephone call after the first missed appointment may have been warranted.

Table 2

Mr. E’s clinical course

| Symptoms | Treatment | |

|---|---|---|

| First ED visit | Agitation Confusion Sleep disturbance Decreased appetite and speech 20-lb weight loss | Empiric antimicrobials for possible meningitis Haloperidol for agitation Quetiapine for delirium Lorazepam taper Thiamine supplementation |

| Second ED visit | Violent behavior Worsening paranoia Responding to internal stimuli Mr. E believes he has 2 wives, but the wife in the room is not the real one, which suggests possible Capgras syndrome Cognitive deficits on mental status exam | Switch from ceftriaxone to ciprofloxacin for Pseudomonas aeruginosa Switch from quetiapine to olanzapine |

| ED: emergency department | ||

Related Resources

- Kaufman DM. Clinical neurology for psychiatrists. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2007.

- Sidhu KS, Balon R, Ajluni V, et al. Standard EEG and the difficult-to-assess mental status. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2009;21(2):103-108.

Drug Brand Names

- Acyclovir • Zovirax

- Ceftriaxone • Rocephin

- Ciprofloxacin • Cipro

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Lorazepam • Ativan

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Thiamine • Betaxin

- Vancomycin • Vancocin

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

CASE: Agitated and paranoid

Mr. E, age 55, presents to the emergency department (ED) with a 2-week history of altered mental status (AMS). His wife reports, “He was normal one day and the next day he was not.” Mr. E also presents with sleep disturbance, decreased appetite and speech, and a 20-lb weight loss. His family reports no recent stressors or head trauma. Mr. E is agitated in the ED and receives a single dose of IV haloperidol, 5 mg. He exhibits paranoia and is afraid to get a CT scan. The medical team attempts a lumbar puncture (LP), but Mr. E does not cooperate.

His laboratory values are: potassium, 3.0 mEq/L; creatinine, 1.60 mg/dL; calcium, 10.6 mg/dL; thyroid-stimulating hormone, 0.177 IU/L; vitamin B12, >1500 pg/mL; folate, >20 ng/mL; and creatine kinase, 281 U/L. Urine drug screen is positive for benzodiazepines and opiates, neither of which was prescribed, and blood alcohol is negative.

Mr. E is admitted for further workup of AMS. His daughter-in-law states that Mr. E is an alcoholic and she is concerned that he may have mixed drugs and alcohol. The medical service starts Mr. E on empiric antimicrobials—vancomycin, ceftriaxone, and acyclovir—because of his AMS, and performs an LP to rule out intracranial pathology. His LP results are unremarkable.

Mr. E appears to be confused during psychiatric evaluation. He requests to be “hypnotized on a helicopter to find out what is wrong with me.” His wife states that Mr. E drank vodka daily but decreased his alcohol consumption after surgery 5 months ago. Before his current admission, he was drinking approximately half a glass of vodka every few days, according to his wife. Mr. E says he has no prior psychiatric admissions. During the mental status exam, his eye contact is poor, with latency of response to questions, thought blocking, and psychomotor retardation. He is alert, oriented to time, place, and person, and cooperative. He cannot concentrate or focus during the interview. He denies suicidal or homicidal ideation.

The authors’ observations

Mr. E appeared to be delirious, as evidenced by the sudden onset of waxing and waning changes in consciousness, attention deficits, and cognition. He also had a history of daily alcohol use and decreased his alcohol intake after a surgery 5 months ago, which puts him at risk for Wernicke’s encephalopathy.1-3 The type of surgery and whether he received adequate thiamine supplementation at that time was unclear. Because Mr. E is older, he has a higher risk of mortality and morbidity from delirium.4,5 We started Mr. E on quetiapine, 50 mg/d, for delirium and an IV lorazepam taper, starting at 2 mg every 8 hours, because the extent of his alcohol and benzodiazepine use was unclear—we weren’t sure how forthcoming he was about his alcohol use. He received IV thiamine supplementation followed by oral thiamine, 100 mg/d.

The authors’ recommendations

We requested a neurology consult, EEG, CSF cultures, and brain MRI (Table 1).6 EEG, chest radiography, thyroid scan, and CT scan were normal and MRI showed no acute intracranial process. However, there was a redemonstration of increased T1 signal seen within the bilateral basal ganglia and relative diminutive appearance to the bilateral mamillary bodies, which suggests possible liver disease and/or alcohol abuse. These findings were unchanged from an MRI Mr. E received 10 years ago, were consistent with his history of alcohol abuse, and may indicate an underlying predisposition to delirium. A CT scan of the abdomen showed hepatic cirrhosis with prominent, tortuous vessels of the upper abdomen, subtle ill-defined hypodensity of the anterior aspect of the liver, and an enlarged spleen.

Mr. E’s mental functioning did not improve with quetiapine and lorazepam. Further evaluation revealed a negative human immunodeficiency virus test and normal heavy metals, ammonia, ceruloplasmin, and thiamine. We suspected limbic encephalitis because of Mr. E’s memory problems and behavioral and psychiatric manifestations,7 but CSF was unremarkable and limbic encephalitis workup of CSF and paraneoplastic antibody panel were negative.

Mr. E’s primary care physician stated that at an appointment 1 month ago, Mr. E was alert, oriented, and conversational with normal thought processing. At that time he had presented with rectal bleeding, occult blood in his stool, and an unintentional 25-lb weight loss over 2 months. It was not clear if his weight loss was caused by poor nutrition—which is common among chronic alcoholics—or an occult disease process.

After 10 days, Mr. E was discharged home from the medicine service with no clear cause of his AMS.

Table 1

Suggested workup for altered mental status

| Complete blood count, basic metabolic profile, creatine kinase |

| Thyroid-stimulating hormone, thyroid scan |

| Vitamin B12, folate, thiamine |

| Blood alcohol, urine drug screen |

| Urine analysis and cultures |

| Lumbar puncture—CSF staining and cultures |

| Chest radiography |

| CT and MRI scan of brain |

| Electroencephalography |

| Neuropsychiatric testing |

| CSF: cerebrospinal fluid Source: Reference 6 |

EVALUATION: Worsening behavior

One week later, Mr. E presents to the ED with continued AMS and worsening behavior at home. Two days ago, he attempted to strangle his dog and cut himself with a knife. His paranoia was worsening and his oral intake continued to decrease. In the ED, Mr. E does not want a chest radiograph because, “I don’t like radiation contaminating my body”; his family stated that he had been suspicious of radiography all of his life. He receives empiric ceftriaxone because of a possible urinary tract infection. Urine culture is positive for Pseudomonas aeruginosa and he is switched to ciprofloxacin. Mr. E is admitted for further workup.

Mr. E’s mother states, “I think this change in behavior is related to my son drinking alcohol for 20 years. This is exactly how he acted when he was on drugs. I think he is having a flashback.” She also reports her son purchased multiple chemicals—the details of which are unclear—that he left lying around the house.

His wife says that after discharge a week ago, Mr. E was stable for 1 or 2 days and then “he started going downhill.” He became more paranoid and he started talking about cameras watching him in his house. Mr. E took quetiapine, 50 mg/d, for a few days, then refused because he thought there was something in the medication. Mr. E’s family feels that at times he is responding to internal stimuli. He makes statements about his DNA being changed and reports that he has 2 wives and the wife in the room was not the real one, which suggests Capgras syndrome. His wife provides a home medication list that includes vitamin B complex, vitamins B12, E, and C, a multivitamin, zinc, magnesium, fish oil, garlic, calcium, glucosamine, chondroitin, herbal supplements, and gingko. The psychiatry team recommends switching from quetiapine to olanzapine, 15 mg/d, because Mr. E was paranoid about taking quetiapine.

We determine that Mr. E does not have medical decision-making capacity.

Because his symptoms do not improve, Mr. E is transferred to the psychiatric intensive care unit. His mental status shows little change while there. Neuropsychiatric testing shows only “cognitive deficits.” He shows signs consistent with neurologic dysfunction in terms of stimulus-bound responding and perseveration, which is compatible with the bilateral basal ganglia lesion seen on MRI. However, some of his behaviors suggest psychiatric and motivationally driven or manipulative etiology. During this testing he was difficult to evaluate and needed to be convinced to engage. At times he was illogical and at other times he showed good focus and recall. It is difficult to draw more definitive conclusions and Mr. E is discharged home with minor improvement in his symptoms. He didn’t attend follow-up appointments. During a courtesy call a few months after his admission, his wife revealed that Mr. E had died after shooting himself. It is unclear if it was an accident or suicide.

The authors’ observations

Mr. E’s diagnosis remains unclear (for a summary of his clinical course, see Table 2). Although his initial presentation was consistent with delirium, the lack of an identifiable medical cause, prolonged time course, and lack of improvement with dopamine blocking agents suggest additional diagnoses such as Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome, rapidly progressive dementia, or a substance-induced disorder. He displayed paranoia and bizarre delusions, which would suggest a thought disorder. However, he also had a history of substance use. A few months after we saw Mr. E, “bath salt” (methylenedioxypyrovalerone) abuse gained national attention. Patients with bath salt intoxication present with confusion, paranoia, and behavioral disturbances as well as a prolonged course.8

Mr. E’s CT and MRI scans, history of alcohol use, and cirrhosis also point to Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome as an underlying diagnosis. It is unclear whether Mr. E experienced alcohol withdrawal and IV glucose without adequate thiamine replacement during a prior surgery. However, MRI findings were unchanged from a previous study 10 years ago.

It is puzzling whether Mr. E’s AMS was a first psychotic break, a result of drug and alcohol use, rapidly progressing dementia, or another neurologic problem that we have not identified. Our tentative diagnosis was Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome because of his history of alcohol use and imaging findings.

Although we used a multidisciplinary team approach that included psychiatry, internal medicine, neurology, neuropsychology, and an aggressive and thorough workup, we could not establish a definitive diagnosis. Unsolved cases such as this can leave patients and clinicians frustrated and may lead to unfavorable outcomes. Additional resources such as a telephone call after the first missed appointment may have been warranted.

Table 2

Mr. E’s clinical course

| Symptoms | Treatment | |

|---|---|---|

| First ED visit | Agitation Confusion Sleep disturbance Decreased appetite and speech 20-lb weight loss | Empiric antimicrobials for possible meningitis Haloperidol for agitation Quetiapine for delirium Lorazepam taper Thiamine supplementation |

| Second ED visit | Violent behavior Worsening paranoia Responding to internal stimuli Mr. E believes he has 2 wives, but the wife in the room is not the real one, which suggests possible Capgras syndrome Cognitive deficits on mental status exam | Switch from ceftriaxone to ciprofloxacin for Pseudomonas aeruginosa Switch from quetiapine to olanzapine |

| ED: emergency department | ||

Related Resources

- Kaufman DM. Clinical neurology for psychiatrists. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2007.

- Sidhu KS, Balon R, Ajluni V, et al. Standard EEG and the difficult-to-assess mental status. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2009;21(2):103-108.

Drug Brand Names

- Acyclovir • Zovirax

- Ceftriaxone • Rocephin

- Ciprofloxacin • Cipro

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Lorazepam • Ativan

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Thiamine • Betaxin

- Vancomycin • Vancocin

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Jiang W, Gagliardi JP, Raj YP, et al. Acute psychotic disorder after gastric bypass surgery: differential diagnosis and treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):15-19.

2. Harrison RA, Vu T, Hunter AJ. Wernicke’s encephalopathy in a patient with schizophrenia. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(12):C8-C11.

3. Sechi GP, Serra A. Wernicke’s encephalopathy: new clinical settings and recent advances in diagnosis and treatment. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(5):442-455.

4. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with delirium. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(5 suppl):1-20.

5. Sharon KI, Fearing MA, Marcantonio RA. Delirium. In: Halter JB Ouslander JG, Tinetti ME, et al, eds. Hazzard’s geriatric medicine and gerontology. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2009:647–658.

6. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Delirium dementia, and amnestic and other cognitive disorders. In: Sadock BJ, Kaplan HI, Sadock VA. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007:319–372.

7. Ahmad SA, Archer HA, Rice CM, et al. Seronegative limbic encephalitis: case report, literature review and proposed treatment algorithm. Pract Neurol. 2011;11(6):355-361.

8. Ross EA, Watson M, Goldberger B. “Bath salts” intoxication. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(10):967-968.

1. Jiang W, Gagliardi JP, Raj YP, et al. Acute psychotic disorder after gastric bypass surgery: differential diagnosis and treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):15-19.

2. Harrison RA, Vu T, Hunter AJ. Wernicke’s encephalopathy in a patient with schizophrenia. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(12):C8-C11.

3. Sechi GP, Serra A. Wernicke’s encephalopathy: new clinical settings and recent advances in diagnosis and treatment. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(5):442-455.

4. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with delirium. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(5 suppl):1-20.

5. Sharon KI, Fearing MA, Marcantonio RA. Delirium. In: Halter JB Ouslander JG, Tinetti ME, et al, eds. Hazzard’s geriatric medicine and gerontology. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2009:647–658.

6. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Delirium dementia, and amnestic and other cognitive disorders. In: Sadock BJ, Kaplan HI, Sadock VA. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007:319–372.

7. Ahmad SA, Archer HA, Rice CM, et al. Seronegative limbic encephalitis: case report, literature review and proposed treatment algorithm. Pract Neurol. 2011;11(6):355-361.

8. Ross EA, Watson M, Goldberger B. “Bath salts” intoxication. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(10):967-968.