User login

The Weekend Effect in Hospitalized Patients: A Meta-Analysis

The presence of a “weekend effect” (increased mortality rate during Saturday and/or Sunday admissions) for hospitalized inpatients is uncertain. Several observational studies1-3 suggested a positive correlation between weekend admission and increased mortality, whereas other studies demonstrated no correlation4-6 or mixed results.7,8 The majority of studies have been published only within the last decade.

Several possible reasons are cited to explain the weekend effect. Decreased and presence of inexperienced staffing on weekends may contribute to a deficit in care.7,9,10 Patients admitted during the weekend may be less likely to undergo procedures or have significant delays before receiving needed intervention.11-13 Another possibility is that there may be differences in severity of illness or comorbidities in patients admitted during the weekend compared with those admitted during the remainder of the week. Due to inconsistency between studies regarding the existence of such an effect, we performed a meta-analysis in hospitalized inpatients to delineate whether or not there is a weekend effect on mortality.

METHODS

Data Sources and Searches

This study was exempt from institutional review board review, and we utilized the recommendations from the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology statement. We examined the mortality rate for hospital inpatients admitted during the weekend (weekend death) compared with the mortality rate for those admitted during the workweek (workweek death). We performed a literature search (January 1966−April 2013) of multiple databases, including PubMed, EMBASE, SCOPUS, and the Cochrane library (see Appendix). Two reviewers (LP, RJP) independently evaluated the full article of each abstract. Any disputes were resolved by a third reviewer (CW). Bibliographic references were hand searched for additional literature.

Study Selection

To be included in the systematic review, the study had to provide discrete mortality data on the weekends (including holidays) versus weekdays, include patients who were admitted as inpatients over the weekend, and be published in the English language. We excluded studies that combined weekend with weekday “off hours” (eg, weekday night shift) data, which could not be extracted or analyzed separately.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Once an article was accepted to be included for the systematic review, the authors extracted relevant data if available, including study location, number and type of patients studied, patient comorbidity data, procedure-related data (type of procedure, difference in rate of procedure and time to procedure performed for both weekday and weekends), any stated and/or implied differences in staffing patterns between weekend and weekdays, and definition of mortality. We used the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale to assess the quality of methodological reporting of the study.14 The definition of weekend and extraction and classification of data (weekend versus weekday) was based on the original study definition. We made no attempt to impose a universal definition of “weekend” on all studies. Similarly, the definition of mortality (eg, 3-/7-/30-day) was based according to the original study definition. Death from a patient admitted on the weekend was defined as a “weekend death” (regardless of ultimate time of death) and similarly, death from a patient admitted on a weekday was defined as a “weekday death.” Although some articles provided specific information on healthcare worker staffing patterns between weekends and weekdays, differences in weekend versus weekday staffing were implied in many articles. In these studies, staffing paradigms were considered to be different between weekend and weekdays if there were specific descriptions of the type of hospitals (urban versus rural, teaching versus nonteaching, large versus small) in the database, which would imply a typical routine staffing pattern as currently occurs in most hospitals (ie, generally less healthcare worker staff on weekends). We only included data that provided times (mean minutes/hours) from admission to the specific intervention and that provided actual rates of intervention performed for both weekend and weekday patients. We only included data that provided an actual rate of intervention performed for both weekend and weekday patients. With regard to patient comorbidities or illness severity index, we used the original studies classification (defined by the original manuscripts), which might include widely accepted global indices or a listing of specific comorbidities and/or physiologic parameters present on admission.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

We used a random effects meta-analysis approach for estimating an overall relative risk (RR) and risk differences of mortality for weekends versus weekdays, as well as subgroup specific estimates, and for computing confidence limits. The DerSimonian and Laird approach was used to estimate the random effects. Within each of the 4 subgroups (weekend staffing, procedure rates and delays, illness severity), we grouped each qualified individual study by the presence of a difference (ie, difference, no difference, or mixed) and then pooled the mortality rates for all of the studies in that group. For instance, in the subgroup of staffing, we sorted available studies by whether weekend staffing was the same or decreased versus weekday staffing, then pooled the mortality rates for studies where staffing levels were the same (versus weekday) and also separately pooled studies where staffing levels were decreased (versus weekday). Data were managed with Stata 13 (Stata Statistical Software: Release 13; StataCorp. 2013, College Station, TX) and R, and all meta-analyses were performed with the metafor package in R.15 Pooled estimated are presented as RR (95% confidence intervals [CI]).

RESULTS

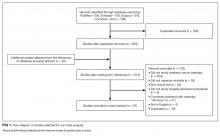

A literature search retrieved a total of 594 unique citations. A review of the bibliographic references yielded an additional 20 articles. Upon evaluation, 97 studies (N = 51,114,109 patients) met inclusion criteria (Figure 1). The articles were published between 2001–2012; the kappa statistic comparing interrater reliability in the selection of articles was 0.86. Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 present a summary of study characteristics and outcomes of the accepted articles. A summary of accepted studies is in Supplementary Table 1. When summing the total number of subjects across all 97 articles, 76% were classified as weekday and 24% were weekend patients.

Weekend Admission/Inpatient Status and Mortality

The definition of the weekend varied among the included studies. The weekend time period was delineated as Friday midnight to Sunday midnight in 66% (65/99) of the studies. The remaining studies typically defined the weekend to be between Friday evening and Monday morning although studies from the Middle East generally defined the weekend as Wednesday/Thursday through Saturday. The definition of mortality also varied among researchers with most studies describing death rate as hospital inpatient mortality although some studies also examined multiple definitions of mortality (eg, 30-day all-cause mortality and hospital inpatient mortality). Not all studies provided a specific timeframe for mortality.

Fifty studies did not report a specific time frame for deaths. When a specific time frame for death was reported, the most common reported time frame was 30 days (n = 15 studies) and risk of mortality at 30 days still was higher for weekends (RR = 1.07; 95% CI,1.03-1.12; I2 = 90%). When we restricted the analysis to the studies that specified any timeframe for mortality (n = 49 studies), the risk of mortality was still significantly higher for weekends (RR = 1.12; 95% CI,1.09-1.15; I2 = 95%).

Weekend Effect Factors

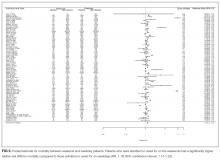

We also performed subgroup analyses to investigate the overall weekend effect by hospital level factors (weekend staffing, procedure rates and delays, illness severity). Complete data were not available for all studies (staffing levels = 73 studies, time to intervention = 18 studies, rate of intervention = 30 studies, illness severity = 64 studies). Patients admitted on the weekends consistently had higher mortality than those admitted during the week, regardless of the levels of weekend/weekday differences in staffing, procedure rates and delays, illness severity (Figure 3). Analysis of studies that included staffing data for weekends revealed that decreased staffing levels on the weekends was associated with a higher mortality for weekend patients (RR = 1.16; 95% CI, 1.12-1.20; I2 = 99%; Figure 3). There was no difference in mortality for weekend patients when staffing was similar to that for the weekdays (RR = 1.21; 95% CI, 0.91-1.63; I2 = 99%).

Analysis for weekend data revealed that longer times to interventions on weekends were associated with significantly higher mortality rates (RR = 1.11; 95% CI, 1.08-1.15; I2 = 0%; Figure 3). When there were no delays to weekend procedure/interventions, there was no difference in mortality between weekend and weekday procedures/interventions (RR = 1.04; 95% CI, 0.96-1.13; I2 = 55%; Figure 3). Some articles included several procedures with “mixed” results (some procedures were “positive,” while other were “negative” for increased mortality). In studies that showed a mixed result for time to intervention, there was a significant increase in mortality (RR = 1.16; 95% CI, 1.06-1.27; I2 = 42%) for weekend patients (Figure 3).

Analyses showed a higher mortality rate on the weekends regardless of whether the rate of intervention/procedures was lower (RR=1.12; 95% CI, 1.07-1.17; I2 = 79%) or the same between weekend and weekdays (RR = 1.08; 95% CI, 1.01-1.16; I2 = 90%; Figure 3). Analyses showed a higher mortality rate on the weekends regardless of whether the illness severity was higher on the weekends (RR = 1.21; 95% CI, 1.07-1.38; I2 = 99%) or the same (RR = 1.21; 95% CI, 1.14-1.28; I2 = 99%) versus that for weekday patients (Figure 3). An inverse funnel plot for publication bias is shown in Figure 4.

DISCUSSION

We have presented one of the first meta-analyses to examine the mortality rate for hospital inpatients admitted during the weekend compared with those admitted during the workweek. We found that patients admitted on the weekends had a significantly higher overall mortality (RR = 1.19; 95% CI, 1.14-1.23; risk difference = 0.014; 95% CI, 0.013-0.016). This association was not modified by differences in weekday and weekend staffing patterns, and other hospital characteristics. Previous systematic reviews have been exclusive to the intensive care unit setting16 or did not specifically examine weekend mortality, which was a component of “off-shift” and/or “after-hours” care.17

These findings should be placed in the context of the recently published literature.18,19 A meta-analysis of cohort studies found that off-hour admission was associated with increased mortality for 28 diseases although the associations varied considerably for different diseases.18 Likewise, a meta-analysis of 21 cohort studies noted that off-hour presentation for patients with acute ischemic stroke was associated with significantly higher short-term mortality.19 Our results of increased weekend mortality corroborate that found in these two meta-analyses. However, our study differs in that we specifically examined only weekend mortality and did not include after-hours care on weekdays, which was included in the off-hour mortality in the other meta-analyses.18,19

Differences in healthcare worker staffing between weekends and weekdays have been proposed to contribute to the observed increase in mortality.7,16,20 Data indicate that lower levels of nursing are associated with increased mortality.10,21-23 The presence of less experienced and/or fewer physician specialists may contribute to increases in mortality.24-26 Fewer or less experienced staff during weekends may contribute to inadequacies in patient handovers and/or handoffs, delays in patient assessment and/or interventions, and overall continuity of care for newly admitted patients.27-33

Our data show little conclusive evidence that the weekend mortality versus weekday mortality vary by staffing level differences. While the estimated RR of mortality differs in magnitude for facilities with no difference in weekend and weekday staffing versus those that have a difference in staffing levels, both estimate an increased mortality on weekends, and the difference in these effects is not statistically significant. It should be noted that there was no difference in mortality for weekend (versus weekday) patients where there was no difference between weekend and weekday staffing; these studies were typically in high acuity units or centers where the general expectation is for 24/7/365 uniform staffing coverage.

A decrease in the use of interventions and/or procedures on weekends has been suggested to contribute to increases in mortality for patients admitted on the weekends.34 Several studies have associated lower weekend rates to higher mortality for a variety of interventions,13,35-37 although some other studies have suggested that lower procedure rates on weekends have no effect on mortality.38-40 Lower diagnostic procedure weekend rates linked to higher mortality rates may exacerbate underlying healthcare disparities.41 Our results do not conclusively show that a decrease rate of intervention and/or procedures for weekends patients is associated with a higher risk of mortality for weekends compared to weekdays.

Delays in intervention and/or procedure on weekends have also been suggested to contribute to increases in mortality.34,42 Similar to that seen with lower rates of diagnostic or therapeutic intervention and/or procedure performed on weekends, delays in potentially critical intervention and/or procedures might ultimately manifest as an increase in mortality.43 Patients admitted to the hospital on weekends and requiring an early procedure were less likely to receive it within 2 days of admission.42 Several studies have shown an association between delays in diagnostic or therapeutic intervention and/or procedure on weekends to a higher hospital inpatient mortality35,42,44,45; however, some data suggested that a delay in time to procedure on weekends may not always be associated with increased mortality.46 Depending on the procedure, there may be a threshold below which the effect of reducing delay times will have no effect on mortality rates.47,48

Patients admitted on the weekends may be different (in the severity of illness and/or comorbidities) than those admitted during the workweek and these potential differences may be a factor for increases in mortality for weekend patients. Whether there is a selection bias for weekend versus weekday patients is not clear.34 This is a complex issue as there is significant heterogeneity in patient case mix depending on the specific disease or condition studied. For instance, one would expect that weekend trauma patients would be different than those seen during the regular workweek.49 Some large scale studies suggest that weekend patients may not be more sick than weekday patients and that any increase in weekend mortality is probably not due to factors such as severity of illness.1,7 Although we were unable to determine if there was an overall difference in illness severity between weekend and weekday patients due to the wide variety of assessments used for illness severity, our results showed statistically comparable higher mortality rate on the weekends regardless of whether the illness severity was higher, the same, or mixed between weekend and weekday patients, suggesting that general illness severity per se may not be as important as the weekend effect on mortality; however, illness severity may still have an important effect on mortality for more specific subgroups (eg, trauma).49

There are several implications of our results. We found a mean increased RR mortality of approximately 19% for patients admitted on the weekends, a number similar to one of the largest published observational studies containing almost 5 million subjects.2 Even if we took a more conservative estimate of 10% increased risk of weekend mortality, this would be equivalent to an excess of 25,000 preventable deaths per year. If the weekend effect were to be placed in context of a public health issue, the weekend effect would be the number 8 cause of death below the 29,000 deaths due to gun violence, but above the 20,000 deaths resulting from sexual behavior (sexual transmitted diseases) in 2000.3, 50,51 Although our data suggest that staffing shortfalls and decreases or delays for procedures on weekends may be associated with an increased mortality for patients admitted on the weekends, further large-scale studies are needed to confirm these findings. Increasing nurse and physician staffing levels and skill mix to cover any potential shortfall on weekends may be expensive, although theoretically, there may be savings accrued from reduced adverse events and shorter length of stay.26,52 Changes to weekend care might only benefit daytime hospitalizations because some studies have shown increased mortality during nighttime regardless of weekend or weekday admission.53

Several methodologic points in our study need to be clarified. We excluded many studies which examined the relationship of off-hours or after-hours admissions and mortality as off-hours studies typically combined weekend and after-hours weekday data. Some studies suggest that off-hour admission may be associated with increased mortality and delays in time for critical procedures during off-hours.18,19 This is a complex topic, but it is clear that the risks of hospitalization vary not just by the day of the week but also by time of the day.54 The use of meta-analyses of nonrandomized trials has been somewhat controversial,55,56 and there may be significant bias or confounding in the pooling of highly varied studies. It is important to keep in mind that there are very different definitions of weekends, populations studied, and measures of mortality rates, even as the pooled statistic suggests a homogeneity among the studies that does not exist.

There are several limitations to our study. Our systematic review may be seen as limited as we included only English language papers. In addition, we did not search nontraditional sources and abstracts. We accepted the definition of a weekend as defined by the original study, which resulted in varied definitions of weekend time period and mortality. There was a lack of specific data on staffing patterns and procedures in many studies, particularly those using databases. We were not able to further subdivide our analysis by admitting service. We were not able to undertake a subgroup analysis by country or continent, which may have implications on the effect of different healthcare systems on healthcare quality. It is unclear whether correlations in our study are a direct consequence of poorer weekend care or are the result of other unknown or unexamined differences between weekend and weekday patient populations.34,57 For instance, there may be other global factors (higher rates of medical errors, higher hospital volumes) which may not be specifically related to weekend care and therefore not been accounted for in many of the studies we examined.10,27,58-61 There may be potential bias of patient phenotypes (are weekend patients different than weekday patients?) admitted on the weekend. Holidays were included in the weekend data and it is not clear how this would affect our findings as some data suggest that there is a significantly higher mortality rate on holidays (versus weekends or weekdays),61 while other data do not.62 There was no universal definition for the timeframe for a weekend and as such, we had to rely on the original article for their determination and definition of weekend versus weekday death.

In summary, our meta-analysis suggests that hospital inpatients admitted during the weekend have a significantly increased mortality compared with those admitted on weekday. While none of our subgroup analyses showed strong evidence on effect modification, the interpretation of these results is hampered by the relatively small number of studies. Further research should be directed to determine the presence of causality between various factors purported to affect mortality and it is possible that we ultimately find that the weekend effect may exist for some but not all patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Jaime Blanck, MLIS, MPA, AHIP, Clinical Informationist, Welch Medical Library, for her invaluable assistance in undertaking the literature searches for this manuscript.

Disclosure

This manuscript has been supported by the Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine; The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine; Baltimore, Maryland. There are no relevant conflicts of interests.

1. Aylin P, Yunus A, Bottle A, Majeed A, Bell D. Weekend mortality for emergency

admissions. A large, multicentre study. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(3):213-217. PubMed

2. Handel AE, Patel SV, Skingsley A, Bramley K, Sobieski R, Ramagopalan SV.

Weekend admissions as an independent predictor of mortality: an analysis of

Scottish hospital admissions. BMJ Open. 2012;2(6): pii: e001789. PubMed

3. Ricciardi R, Roberts PL, Read TE, Baxter NN, Marcello PW, Schoetz DJ. Mortality

rate after nonelective hospital admission. Arch Surg. 2011;146(5):545-551. PubMed

4. Fonarow GC, Abraham WT, Albert NM, et al. Day of admission and clinical

outcomes for patients hospitalized for heart failure: findings from the Organized

Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients With Heart

Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF). Circ Heart Fail. 2008;1(1):50-57. PubMed

5. Hoh BL, Chi YY, Waters MF, Mocco J, Barker FG 2nd. Effect of weekend compared

with weekday stroke admission on thrombolytic use, in-hospital mortality,

discharge disposition, hospital charges, and length of stay in the Nationwide Inpatient

Sample Database, 2002 to 2007. Stroke. 2010;41(10):2323-2328. PubMed

6. Koike S, Tanabe S, Ogawa T, et al. Effect of time and day of admission on 1-month

survival and neurologically favourable 1-month survival in out-of-hospital cardiopulmonary

arrest patients. Resuscitation. 2011;82(7):863-868. PubMed

7. Bell CM, Redelmeier DA. Mortality among patients admitted to hospitals on

weekends as compared with weekdays. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(9):663-668. PubMed

8. Freemantle N, Richardson M, Wood J, et al. Weekend hospitalization and additional

risk of death: an analysis of inpatient data. J R Soc Med. 2012;105(2):74-84. PubMed

9. Schilling PL, Campbell DA Jr, Englesbe MJ, Davis MM. A comparison of in-hospital

mortality risk conferred by high hospital occupancy, differences in nurse

staffing levels, weekend admission, and seasonal influenza. Med Care. 2010;48(3):

224-232. PubMed

10. Wong HJ, Morra D. Excellent hospital care for all: open and operating 24/7. J Gen

Intern Med. 2011;26(9):1050-1052. PubMed

11. Dorn SD, Shah ND, Berg BP, Naessens JM. Effect of weekend hospital admission

on gastrointestinal hemorrhage outcomes. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(6):1658-1666. PubMed

12. Kostis WJ, Demissie K, Marcella SW, et al. Weekend versus weekday admission

and mortality from myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(11):1099-1109. PubMed

13. McKinney JS, Deng Y, Kasner SE, Kostis JB; Myocardial Infarction Data Acquisition

System (MIDAS 15) Study Group. Comprehensive stroke centers overcome

the weekend versus weekday gap in stroke treatment and mortality. Stroke.

2011;42(9):2403-2409. PubMed

14. Margulis AV, Pladevall M, Riera-Guardia N, et al. Quality assessment of observational

studies in a drug-safety systematic review, comparison of two tools: the

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale and the RTI item bank. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:359-368. PubMed

15. Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat

Softw. 2010;36(3):1-48.

16. Cavallazzi R, Marik PE, Hirani A, Pachinburavan M, Vasu TS, Leiby BE. Association

between time of admission to the ICU and mortality: a systematic review and

metaanalysis. Chest. 2010;138(1):68-75. PubMed

17. de Cordova PB, Phibbs CS, Bartel AP, Stone PW. Twenty-four/seven: a

mixed-method systematic review of the off-shift literature. J Adv Nurs.

2012;68(7):1454-1468. PubMed

18. Zhou Y, Li W, Herath C, Xia J, Hu B, Song F, Cao S, Lu Z. Off-hour admission and

mortality risk for 28 specific diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 251

cohorts. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(3):e003102. PubMed

19. Sorita A, Ahmed A, Starr SR, et al. Off-hour presentation and outcomes in

patients with acute myocardial infarction: systematic review and meta-analysis.

BMJ. 2014;348:f7393. PubMed

20. Ricciardi R, Nelson J, Roberts PL, Marcello PW, Read TE, Schoetz DJ. Is the

presence of medical trainees associated with increased mortality with weekend

admission? BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(1):4. PubMed

21. Needleman J, Buerhaus P, Pankratz VS, Leibson CL, Stevens SR, Harris M. Nurse

staffing and inpatient hospital mortality. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(11):1037-1045. PubMed

22. Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Sochalski J, Silber JH. Hospital nurse

staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. JAMA.

2002;288(16):1987-1993. PubMed

23. Hamilton KE, Redshaw ME, Tarnow-Mordi W. Nurse staffing in relation to

risk-adjusted mortality in neonatal care. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed.

2007;92(2):F99-F103. PubMed

766 An Official Publication of the Society of Hospital Medicine Journal of Hospital Medicine Vol 12 | No 9 | September 2017

Pauls et al | The Weekend Effect: A Meta-Analysis

24. Haut ER, Chang DC, Efron DT, Cornwell EE 3rd. Injured patients have lower

mortality when treated by “full-time” trauma surgeons vs. surgeons who cover

trauma “part-time”. J Trauma. 2006;61(2):272-278. PubMed

25. Wallace DJ, Angus DC, Barnato AE, Kramer AA, Kahn JM. Nighttime intensivist

staffing and mortality among critically ill patients. N Engl J Med.

2012;366(22):2093-2101. PubMed

26. Pronovost PJ, Angus DC, Dorman T, Robinson KA, Dremsizov TT, Young TL.

Physician staffing patterns and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients: a systematic

review. JAMA. 2002;288(17):2151-2162. PubMed

27. Weissman JS, Rothschild JM, Bendavid E, et al. Hospital workload and adverse

events. Med Care. 2007;45(5):448-455. PubMed

28. Hamilton P, Eschiti VS, Hernandez K, Neill D. Differences between weekend and

weekday nurse work environments and patient outcomes: a focus group approach

to model testing. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2007;21(4):331-341. PubMed

29. Johner AM, Merchant S, Aslani N, et al Acute general surgery in Canada: a survey

of current handover practices. Can J Surg. 2013;56(3):E24-E28. PubMed

30. de Cordova PB, Phibbs CS, Stone PW. Perceptions and observations of off-shift

nursing. J Nurs Manag. 2013;21(2):283-292. PubMed

31. Pfeffer PE, Nazareth D, Main N, Hardoon S, Choudhury AB. Are weekend

handovers of adequate quality for the on-call general medical team? Clin Med.

2011;11(6):536-540. PubMed

32. Eschiti V, Hamilton P. Off-peak nurse staffing: critical-care nurses speak. Dimens

Crit Care Nurs. 2011;30(1):62-69. PubMed

33. Button LA, Roberts SE, Evans PA, et al. Hospitalized incidence and case fatality

for upper gastrointestinal bleeding from 1999 to 2007: a record linkage study. Aliment

Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33(1):64-76. PubMed

34. Becker DJ. Weekend hospitalization and mortality: a critical review. Expert Rev

Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2008;8(1):23-26. PubMed

35. Deshmukh A, Pant S, Kumar G, Bursac Z, Paydak H, Mehta JL. Comparison of

outcomes of weekend versus weekday admissions for atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol.

2012;110(2):208-211. PubMed

36. Nanchal R, Kumar G, Taneja A, et al. Pulmonary embolism: the weekend effect.

Chest. 2012;142(3):690-696. PubMed

37. Palmer WL, Bottle A, Davie C, Vincent CA, Aylin P. Dying for the weekend: a

retrospective cohort study on the association between day of hospital presentation

and the quality and safety of stroke care. Arch Neurol. 2012;69(10):1296-1302. PubMed

38. Dasenbrock HH, Pradilla G, Witham TF, Gokaslan ZL, Bydon A. The impact

of weekend hospital admission on the timing of intervention and outcomes after

surgery for spinal metastases. Neurosurgery. 2012;70(3):586-593. PubMed

39. Jairath V, Kahan BC, Logan RF, et al. Mortality from acute upper gastrointestinal

bleeding in the United Kingdom: does it display a “weekend effect”? Am J Gastroenterol.

2011;106(9):1621-1628. PubMed

40. Myers RP, Kaplan GG, Shaheen AM. The effect of weekend versus weekday

admission on outcomes of esophageal variceal hemorrhage. Can J Gastroenterol.

2009;23(7):495-501. PubMed

41. Rudd AG, Hoffman A, Down C, Pearson M, Lowe D. Access to stroke care in

England, Wales and Northern Ireland: the effect of age, gender and weekend admission.

Age Ageing. 2007;36(3):247-255. PubMed

42. Lapointe-Shaw L, Abushomar H, Chen XK, et al. Care and outcomes of patients

with cancer admitted to the hospital on weekends and holidays: a retrospective

cohort study. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14(7):867-874. PubMed

43. Chan PS, Krumholz HM, Nichol G, Nallamothu BK; American Heart Association

National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Investigators. Delayed time to

defibrillation after in-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(1):9-17. PubMed

44. McGuire KJ, Bernstein J, Polsky D, Silber JH. The 2004 Marshall Urist Award:

Delays until surgery after hip fracture increases mortality. Clin Orthop Relat Res.

2004;(428):294-301. PubMed

45. Krüth P, Zeymer U, Gitt A, et al. Influence of presentation at the weekend on

treatment and outcome in ST-elevation myocardial infarction in hospitals with

catheterization laboratories. Clin Res Cardiol. 2008;97(10):742-747. PubMed

46. Jneid H, Fonarow GC, Cannon CP, et al. Impact of time of presentation on the care

and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2008;117(19):2502-2509. PubMed

47. Menees DS, Peterson ED, Wang Y, et al. Door-to-balloon time and mortality

among patients undergoing primary PCI. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(10):901-909. PubMed

48. Bates ER, Jacobs AK. Time to treatment in patients with STEMI. N Engl J Med.

2013;369(10):889-892. PubMed

49. Carmody IC, Romero J, Velmahos GC. Day for night: should we staff a trauma

center like a nightclub? Am Surg. 2002;68(12):1048-1051. PubMed

50. Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the

United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291(10):1238-1245. PubMed

51. McCook A. More hospital deaths on weekends. http://www.reuters.com/article/

2011/05/20/us-more-hospital-deaths-weekends-idUSTRE74J5RM20110520.

Accessed March 7, 2017.

52. Mourad M, Adler J. Safe, high quality care around the clock: what will it take to

get us there? J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(9):948-950. PubMed

53. Magid DJ, Wang Y, Herrin J, et al. Relationship between time of day, day of week,

timeliness of reperfusion, and in-hospital mortality for patients with acute ST-segment

elevation myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2005;294(7):803-812. PubMed

54. Coiera E, Wang Y, Magrabi F, Concha OP, Gallego B, Runciman W. Predicting

the cumulative risk of death during hospitalization by modeling weekend, weekday

and diurnal mortality risks. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:226. PubMed

55. Greenland S. Can meta-analysis be salvaged? Am J Epidemiol. 1994;140(9):783-787. PubMed

56. Shapiro S. Meta-analysis/Shmeta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;140(9):771-778. PubMed

57. Halm EA, Chassin MR. Why do hospital death rates vary? N Engl J Med.

2001;345(9):692-694. PubMed

58. Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality

in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(15):1128-1137. PubMed

59. Kaier K, Mutters NT, Frank U. Bed occupancy rates and hospital-acquired infections

– should beds be kept empty? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(10):941-945. PubMed

60. Chrusch CA, Olafson KP, McMillian PM, Roberts DE, Gray PR. High occupancy

increases the risk of early death or readmission after transfer from intensive care.

Crit Care Med. 2009;37(10):2753-2758. PubMed

61. Foss NB, Kehlet H. Short-term mortality in hip fracture patients admitted during

weekends and holidays. Br J Anaesth. 2006;96(4):450-454. PubMed

62. Daugaard CL, Jørgensen HL, Riis T, Lauritzen JB, Duus BR, van der Mark S. Is

mortality after hip fracture associated with surgical delay or admission during

weekends and public holidays? A retrospective study of 38,020 patients. Acta Orthop.

2012;83(6):609-613. PubMed

The presence of a “weekend effect” (increased mortality rate during Saturday and/or Sunday admissions) for hospitalized inpatients is uncertain. Several observational studies1-3 suggested a positive correlation between weekend admission and increased mortality, whereas other studies demonstrated no correlation4-6 or mixed results.7,8 The majority of studies have been published only within the last decade.

Several possible reasons are cited to explain the weekend effect. Decreased and presence of inexperienced staffing on weekends may contribute to a deficit in care.7,9,10 Patients admitted during the weekend may be less likely to undergo procedures or have significant delays before receiving needed intervention.11-13 Another possibility is that there may be differences in severity of illness or comorbidities in patients admitted during the weekend compared with those admitted during the remainder of the week. Due to inconsistency between studies regarding the existence of such an effect, we performed a meta-analysis in hospitalized inpatients to delineate whether or not there is a weekend effect on mortality.

METHODS

Data Sources and Searches

This study was exempt from institutional review board review, and we utilized the recommendations from the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology statement. We examined the mortality rate for hospital inpatients admitted during the weekend (weekend death) compared with the mortality rate for those admitted during the workweek (workweek death). We performed a literature search (January 1966−April 2013) of multiple databases, including PubMed, EMBASE, SCOPUS, and the Cochrane library (see Appendix). Two reviewers (LP, RJP) independently evaluated the full article of each abstract. Any disputes were resolved by a third reviewer (CW). Bibliographic references were hand searched for additional literature.

Study Selection

To be included in the systematic review, the study had to provide discrete mortality data on the weekends (including holidays) versus weekdays, include patients who were admitted as inpatients over the weekend, and be published in the English language. We excluded studies that combined weekend with weekday “off hours” (eg, weekday night shift) data, which could not be extracted or analyzed separately.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Once an article was accepted to be included for the systematic review, the authors extracted relevant data if available, including study location, number and type of patients studied, patient comorbidity data, procedure-related data (type of procedure, difference in rate of procedure and time to procedure performed for both weekday and weekends), any stated and/or implied differences in staffing patterns between weekend and weekdays, and definition of mortality. We used the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale to assess the quality of methodological reporting of the study.14 The definition of weekend and extraction and classification of data (weekend versus weekday) was based on the original study definition. We made no attempt to impose a universal definition of “weekend” on all studies. Similarly, the definition of mortality (eg, 3-/7-/30-day) was based according to the original study definition. Death from a patient admitted on the weekend was defined as a “weekend death” (regardless of ultimate time of death) and similarly, death from a patient admitted on a weekday was defined as a “weekday death.” Although some articles provided specific information on healthcare worker staffing patterns between weekends and weekdays, differences in weekend versus weekday staffing were implied in many articles. In these studies, staffing paradigms were considered to be different between weekend and weekdays if there were specific descriptions of the type of hospitals (urban versus rural, teaching versus nonteaching, large versus small) in the database, which would imply a typical routine staffing pattern as currently occurs in most hospitals (ie, generally less healthcare worker staff on weekends). We only included data that provided times (mean minutes/hours) from admission to the specific intervention and that provided actual rates of intervention performed for both weekend and weekday patients. We only included data that provided an actual rate of intervention performed for both weekend and weekday patients. With regard to patient comorbidities or illness severity index, we used the original studies classification (defined by the original manuscripts), which might include widely accepted global indices or a listing of specific comorbidities and/or physiologic parameters present on admission.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

We used a random effects meta-analysis approach for estimating an overall relative risk (RR) and risk differences of mortality for weekends versus weekdays, as well as subgroup specific estimates, and for computing confidence limits. The DerSimonian and Laird approach was used to estimate the random effects. Within each of the 4 subgroups (weekend staffing, procedure rates and delays, illness severity), we grouped each qualified individual study by the presence of a difference (ie, difference, no difference, or mixed) and then pooled the mortality rates for all of the studies in that group. For instance, in the subgroup of staffing, we sorted available studies by whether weekend staffing was the same or decreased versus weekday staffing, then pooled the mortality rates for studies where staffing levels were the same (versus weekday) and also separately pooled studies where staffing levels were decreased (versus weekday). Data were managed with Stata 13 (Stata Statistical Software: Release 13; StataCorp. 2013, College Station, TX) and R, and all meta-analyses were performed with the metafor package in R.15 Pooled estimated are presented as RR (95% confidence intervals [CI]).

RESULTS

A literature search retrieved a total of 594 unique citations. A review of the bibliographic references yielded an additional 20 articles. Upon evaluation, 97 studies (N = 51,114,109 patients) met inclusion criteria (Figure 1). The articles were published between 2001–2012; the kappa statistic comparing interrater reliability in the selection of articles was 0.86. Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 present a summary of study characteristics and outcomes of the accepted articles. A summary of accepted studies is in Supplementary Table 1. When summing the total number of subjects across all 97 articles, 76% were classified as weekday and 24% were weekend patients.

Weekend Admission/Inpatient Status and Mortality

The definition of the weekend varied among the included studies. The weekend time period was delineated as Friday midnight to Sunday midnight in 66% (65/99) of the studies. The remaining studies typically defined the weekend to be between Friday evening and Monday morning although studies from the Middle East generally defined the weekend as Wednesday/Thursday through Saturday. The definition of mortality also varied among researchers with most studies describing death rate as hospital inpatient mortality although some studies also examined multiple definitions of mortality (eg, 30-day all-cause mortality and hospital inpatient mortality). Not all studies provided a specific timeframe for mortality.

Fifty studies did not report a specific time frame for deaths. When a specific time frame for death was reported, the most common reported time frame was 30 days (n = 15 studies) and risk of mortality at 30 days still was higher for weekends (RR = 1.07; 95% CI,1.03-1.12; I2 = 90%). When we restricted the analysis to the studies that specified any timeframe for mortality (n = 49 studies), the risk of mortality was still significantly higher for weekends (RR = 1.12; 95% CI,1.09-1.15; I2 = 95%).

Weekend Effect Factors

We also performed subgroup analyses to investigate the overall weekend effect by hospital level factors (weekend staffing, procedure rates and delays, illness severity). Complete data were not available for all studies (staffing levels = 73 studies, time to intervention = 18 studies, rate of intervention = 30 studies, illness severity = 64 studies). Patients admitted on the weekends consistently had higher mortality than those admitted during the week, regardless of the levels of weekend/weekday differences in staffing, procedure rates and delays, illness severity (Figure 3). Analysis of studies that included staffing data for weekends revealed that decreased staffing levels on the weekends was associated with a higher mortality for weekend patients (RR = 1.16; 95% CI, 1.12-1.20; I2 = 99%; Figure 3). There was no difference in mortality for weekend patients when staffing was similar to that for the weekdays (RR = 1.21; 95% CI, 0.91-1.63; I2 = 99%).

Analysis for weekend data revealed that longer times to interventions on weekends were associated with significantly higher mortality rates (RR = 1.11; 95% CI, 1.08-1.15; I2 = 0%; Figure 3). When there were no delays to weekend procedure/interventions, there was no difference in mortality between weekend and weekday procedures/interventions (RR = 1.04; 95% CI, 0.96-1.13; I2 = 55%; Figure 3). Some articles included several procedures with “mixed” results (some procedures were “positive,” while other were “negative” for increased mortality). In studies that showed a mixed result for time to intervention, there was a significant increase in mortality (RR = 1.16; 95% CI, 1.06-1.27; I2 = 42%) for weekend patients (Figure 3).

Analyses showed a higher mortality rate on the weekends regardless of whether the rate of intervention/procedures was lower (RR=1.12; 95% CI, 1.07-1.17; I2 = 79%) or the same between weekend and weekdays (RR = 1.08; 95% CI, 1.01-1.16; I2 = 90%; Figure 3). Analyses showed a higher mortality rate on the weekends regardless of whether the illness severity was higher on the weekends (RR = 1.21; 95% CI, 1.07-1.38; I2 = 99%) or the same (RR = 1.21; 95% CI, 1.14-1.28; I2 = 99%) versus that for weekday patients (Figure 3). An inverse funnel plot for publication bias is shown in Figure 4.

DISCUSSION

We have presented one of the first meta-analyses to examine the mortality rate for hospital inpatients admitted during the weekend compared with those admitted during the workweek. We found that patients admitted on the weekends had a significantly higher overall mortality (RR = 1.19; 95% CI, 1.14-1.23; risk difference = 0.014; 95% CI, 0.013-0.016). This association was not modified by differences in weekday and weekend staffing patterns, and other hospital characteristics. Previous systematic reviews have been exclusive to the intensive care unit setting16 or did not specifically examine weekend mortality, which was a component of “off-shift” and/or “after-hours” care.17

These findings should be placed in the context of the recently published literature.18,19 A meta-analysis of cohort studies found that off-hour admission was associated with increased mortality for 28 diseases although the associations varied considerably for different diseases.18 Likewise, a meta-analysis of 21 cohort studies noted that off-hour presentation for patients with acute ischemic stroke was associated with significantly higher short-term mortality.19 Our results of increased weekend mortality corroborate that found in these two meta-analyses. However, our study differs in that we specifically examined only weekend mortality and did not include after-hours care on weekdays, which was included in the off-hour mortality in the other meta-analyses.18,19

Differences in healthcare worker staffing between weekends and weekdays have been proposed to contribute to the observed increase in mortality.7,16,20 Data indicate that lower levels of nursing are associated with increased mortality.10,21-23 The presence of less experienced and/or fewer physician specialists may contribute to increases in mortality.24-26 Fewer or less experienced staff during weekends may contribute to inadequacies in patient handovers and/or handoffs, delays in patient assessment and/or interventions, and overall continuity of care for newly admitted patients.27-33

Our data show little conclusive evidence that the weekend mortality versus weekday mortality vary by staffing level differences. While the estimated RR of mortality differs in magnitude for facilities with no difference in weekend and weekday staffing versus those that have a difference in staffing levels, both estimate an increased mortality on weekends, and the difference in these effects is not statistically significant. It should be noted that there was no difference in mortality for weekend (versus weekday) patients where there was no difference between weekend and weekday staffing; these studies were typically in high acuity units or centers where the general expectation is for 24/7/365 uniform staffing coverage.

A decrease in the use of interventions and/or procedures on weekends has been suggested to contribute to increases in mortality for patients admitted on the weekends.34 Several studies have associated lower weekend rates to higher mortality for a variety of interventions,13,35-37 although some other studies have suggested that lower procedure rates on weekends have no effect on mortality.38-40 Lower diagnostic procedure weekend rates linked to higher mortality rates may exacerbate underlying healthcare disparities.41 Our results do not conclusively show that a decrease rate of intervention and/or procedures for weekends patients is associated with a higher risk of mortality for weekends compared to weekdays.

Delays in intervention and/or procedure on weekends have also been suggested to contribute to increases in mortality.34,42 Similar to that seen with lower rates of diagnostic or therapeutic intervention and/or procedure performed on weekends, delays in potentially critical intervention and/or procedures might ultimately manifest as an increase in mortality.43 Patients admitted to the hospital on weekends and requiring an early procedure were less likely to receive it within 2 days of admission.42 Several studies have shown an association between delays in diagnostic or therapeutic intervention and/or procedure on weekends to a higher hospital inpatient mortality35,42,44,45; however, some data suggested that a delay in time to procedure on weekends may not always be associated with increased mortality.46 Depending on the procedure, there may be a threshold below which the effect of reducing delay times will have no effect on mortality rates.47,48

Patients admitted on the weekends may be different (in the severity of illness and/or comorbidities) than those admitted during the workweek and these potential differences may be a factor for increases in mortality for weekend patients. Whether there is a selection bias for weekend versus weekday patients is not clear.34 This is a complex issue as there is significant heterogeneity in patient case mix depending on the specific disease or condition studied. For instance, one would expect that weekend trauma patients would be different than those seen during the regular workweek.49 Some large scale studies suggest that weekend patients may not be more sick than weekday patients and that any increase in weekend mortality is probably not due to factors such as severity of illness.1,7 Although we were unable to determine if there was an overall difference in illness severity between weekend and weekday patients due to the wide variety of assessments used for illness severity, our results showed statistically comparable higher mortality rate on the weekends regardless of whether the illness severity was higher, the same, or mixed between weekend and weekday patients, suggesting that general illness severity per se may not be as important as the weekend effect on mortality; however, illness severity may still have an important effect on mortality for more specific subgroups (eg, trauma).49

There are several implications of our results. We found a mean increased RR mortality of approximately 19% for patients admitted on the weekends, a number similar to one of the largest published observational studies containing almost 5 million subjects.2 Even if we took a more conservative estimate of 10% increased risk of weekend mortality, this would be equivalent to an excess of 25,000 preventable deaths per year. If the weekend effect were to be placed in context of a public health issue, the weekend effect would be the number 8 cause of death below the 29,000 deaths due to gun violence, but above the 20,000 deaths resulting from sexual behavior (sexual transmitted diseases) in 2000.3, 50,51 Although our data suggest that staffing shortfalls and decreases or delays for procedures on weekends may be associated with an increased mortality for patients admitted on the weekends, further large-scale studies are needed to confirm these findings. Increasing nurse and physician staffing levels and skill mix to cover any potential shortfall on weekends may be expensive, although theoretically, there may be savings accrued from reduced adverse events and shorter length of stay.26,52 Changes to weekend care might only benefit daytime hospitalizations because some studies have shown increased mortality during nighttime regardless of weekend or weekday admission.53

Several methodologic points in our study need to be clarified. We excluded many studies which examined the relationship of off-hours or after-hours admissions and mortality as off-hours studies typically combined weekend and after-hours weekday data. Some studies suggest that off-hour admission may be associated with increased mortality and delays in time for critical procedures during off-hours.18,19 This is a complex topic, but it is clear that the risks of hospitalization vary not just by the day of the week but also by time of the day.54 The use of meta-analyses of nonrandomized trials has been somewhat controversial,55,56 and there may be significant bias or confounding in the pooling of highly varied studies. It is important to keep in mind that there are very different definitions of weekends, populations studied, and measures of mortality rates, even as the pooled statistic suggests a homogeneity among the studies that does not exist.

There are several limitations to our study. Our systematic review may be seen as limited as we included only English language papers. In addition, we did not search nontraditional sources and abstracts. We accepted the definition of a weekend as defined by the original study, which resulted in varied definitions of weekend time period and mortality. There was a lack of specific data on staffing patterns and procedures in many studies, particularly those using databases. We were not able to further subdivide our analysis by admitting service. We were not able to undertake a subgroup analysis by country or continent, which may have implications on the effect of different healthcare systems on healthcare quality. It is unclear whether correlations in our study are a direct consequence of poorer weekend care or are the result of other unknown or unexamined differences between weekend and weekday patient populations.34,57 For instance, there may be other global factors (higher rates of medical errors, higher hospital volumes) which may not be specifically related to weekend care and therefore not been accounted for in many of the studies we examined.10,27,58-61 There may be potential bias of patient phenotypes (are weekend patients different than weekday patients?) admitted on the weekend. Holidays were included in the weekend data and it is not clear how this would affect our findings as some data suggest that there is a significantly higher mortality rate on holidays (versus weekends or weekdays),61 while other data do not.62 There was no universal definition for the timeframe for a weekend and as such, we had to rely on the original article for their determination and definition of weekend versus weekday death.

In summary, our meta-analysis suggests that hospital inpatients admitted during the weekend have a significantly increased mortality compared with those admitted on weekday. While none of our subgroup analyses showed strong evidence on effect modification, the interpretation of these results is hampered by the relatively small number of studies. Further research should be directed to determine the presence of causality between various factors purported to affect mortality and it is possible that we ultimately find that the weekend effect may exist for some but not all patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Jaime Blanck, MLIS, MPA, AHIP, Clinical Informationist, Welch Medical Library, for her invaluable assistance in undertaking the literature searches for this manuscript.

Disclosure

This manuscript has been supported by the Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine; The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine; Baltimore, Maryland. There are no relevant conflicts of interests.

The presence of a “weekend effect” (increased mortality rate during Saturday and/or Sunday admissions) for hospitalized inpatients is uncertain. Several observational studies1-3 suggested a positive correlation between weekend admission and increased mortality, whereas other studies demonstrated no correlation4-6 or mixed results.7,8 The majority of studies have been published only within the last decade.

Several possible reasons are cited to explain the weekend effect. Decreased and presence of inexperienced staffing on weekends may contribute to a deficit in care.7,9,10 Patients admitted during the weekend may be less likely to undergo procedures or have significant delays before receiving needed intervention.11-13 Another possibility is that there may be differences in severity of illness or comorbidities in patients admitted during the weekend compared with those admitted during the remainder of the week. Due to inconsistency between studies regarding the existence of such an effect, we performed a meta-analysis in hospitalized inpatients to delineate whether or not there is a weekend effect on mortality.

METHODS

Data Sources and Searches

This study was exempt from institutional review board review, and we utilized the recommendations from the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology statement. We examined the mortality rate for hospital inpatients admitted during the weekend (weekend death) compared with the mortality rate for those admitted during the workweek (workweek death). We performed a literature search (January 1966−April 2013) of multiple databases, including PubMed, EMBASE, SCOPUS, and the Cochrane library (see Appendix). Two reviewers (LP, RJP) independently evaluated the full article of each abstract. Any disputes were resolved by a third reviewer (CW). Bibliographic references were hand searched for additional literature.

Study Selection

To be included in the systematic review, the study had to provide discrete mortality data on the weekends (including holidays) versus weekdays, include patients who were admitted as inpatients over the weekend, and be published in the English language. We excluded studies that combined weekend with weekday “off hours” (eg, weekday night shift) data, which could not be extracted or analyzed separately.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Once an article was accepted to be included for the systematic review, the authors extracted relevant data if available, including study location, number and type of patients studied, patient comorbidity data, procedure-related data (type of procedure, difference in rate of procedure and time to procedure performed for both weekday and weekends), any stated and/or implied differences in staffing patterns between weekend and weekdays, and definition of mortality. We used the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale to assess the quality of methodological reporting of the study.14 The definition of weekend and extraction and classification of data (weekend versus weekday) was based on the original study definition. We made no attempt to impose a universal definition of “weekend” on all studies. Similarly, the definition of mortality (eg, 3-/7-/30-day) was based according to the original study definition. Death from a patient admitted on the weekend was defined as a “weekend death” (regardless of ultimate time of death) and similarly, death from a patient admitted on a weekday was defined as a “weekday death.” Although some articles provided specific information on healthcare worker staffing patterns between weekends and weekdays, differences in weekend versus weekday staffing were implied in many articles. In these studies, staffing paradigms were considered to be different between weekend and weekdays if there were specific descriptions of the type of hospitals (urban versus rural, teaching versus nonteaching, large versus small) in the database, which would imply a typical routine staffing pattern as currently occurs in most hospitals (ie, generally less healthcare worker staff on weekends). We only included data that provided times (mean minutes/hours) from admission to the specific intervention and that provided actual rates of intervention performed for both weekend and weekday patients. We only included data that provided an actual rate of intervention performed for both weekend and weekday patients. With regard to patient comorbidities or illness severity index, we used the original studies classification (defined by the original manuscripts), which might include widely accepted global indices or a listing of specific comorbidities and/or physiologic parameters present on admission.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

We used a random effects meta-analysis approach for estimating an overall relative risk (RR) and risk differences of mortality for weekends versus weekdays, as well as subgroup specific estimates, and for computing confidence limits. The DerSimonian and Laird approach was used to estimate the random effects. Within each of the 4 subgroups (weekend staffing, procedure rates and delays, illness severity), we grouped each qualified individual study by the presence of a difference (ie, difference, no difference, or mixed) and then pooled the mortality rates for all of the studies in that group. For instance, in the subgroup of staffing, we sorted available studies by whether weekend staffing was the same or decreased versus weekday staffing, then pooled the mortality rates for studies where staffing levels were the same (versus weekday) and also separately pooled studies where staffing levels were decreased (versus weekday). Data were managed with Stata 13 (Stata Statistical Software: Release 13; StataCorp. 2013, College Station, TX) and R, and all meta-analyses were performed with the metafor package in R.15 Pooled estimated are presented as RR (95% confidence intervals [CI]).

RESULTS

A literature search retrieved a total of 594 unique citations. A review of the bibliographic references yielded an additional 20 articles. Upon evaluation, 97 studies (N = 51,114,109 patients) met inclusion criteria (Figure 1). The articles were published between 2001–2012; the kappa statistic comparing interrater reliability in the selection of articles was 0.86. Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 present a summary of study characteristics and outcomes of the accepted articles. A summary of accepted studies is in Supplementary Table 1. When summing the total number of subjects across all 97 articles, 76% were classified as weekday and 24% were weekend patients.

Weekend Admission/Inpatient Status and Mortality

The definition of the weekend varied among the included studies. The weekend time period was delineated as Friday midnight to Sunday midnight in 66% (65/99) of the studies. The remaining studies typically defined the weekend to be between Friday evening and Monday morning although studies from the Middle East generally defined the weekend as Wednesday/Thursday through Saturday. The definition of mortality also varied among researchers with most studies describing death rate as hospital inpatient mortality although some studies also examined multiple definitions of mortality (eg, 30-day all-cause mortality and hospital inpatient mortality). Not all studies provided a specific timeframe for mortality.

Fifty studies did not report a specific time frame for deaths. When a specific time frame for death was reported, the most common reported time frame was 30 days (n = 15 studies) and risk of mortality at 30 days still was higher for weekends (RR = 1.07; 95% CI,1.03-1.12; I2 = 90%). When we restricted the analysis to the studies that specified any timeframe for mortality (n = 49 studies), the risk of mortality was still significantly higher for weekends (RR = 1.12; 95% CI,1.09-1.15; I2 = 95%).

Weekend Effect Factors

We also performed subgroup analyses to investigate the overall weekend effect by hospital level factors (weekend staffing, procedure rates and delays, illness severity). Complete data were not available for all studies (staffing levels = 73 studies, time to intervention = 18 studies, rate of intervention = 30 studies, illness severity = 64 studies). Patients admitted on the weekends consistently had higher mortality than those admitted during the week, regardless of the levels of weekend/weekday differences in staffing, procedure rates and delays, illness severity (Figure 3). Analysis of studies that included staffing data for weekends revealed that decreased staffing levels on the weekends was associated with a higher mortality for weekend patients (RR = 1.16; 95% CI, 1.12-1.20; I2 = 99%; Figure 3). There was no difference in mortality for weekend patients when staffing was similar to that for the weekdays (RR = 1.21; 95% CI, 0.91-1.63; I2 = 99%).

Analysis for weekend data revealed that longer times to interventions on weekends were associated with significantly higher mortality rates (RR = 1.11; 95% CI, 1.08-1.15; I2 = 0%; Figure 3). When there were no delays to weekend procedure/interventions, there was no difference in mortality between weekend and weekday procedures/interventions (RR = 1.04; 95% CI, 0.96-1.13; I2 = 55%; Figure 3). Some articles included several procedures with “mixed” results (some procedures were “positive,” while other were “negative” for increased mortality). In studies that showed a mixed result for time to intervention, there was a significant increase in mortality (RR = 1.16; 95% CI, 1.06-1.27; I2 = 42%) for weekend patients (Figure 3).

Analyses showed a higher mortality rate on the weekends regardless of whether the rate of intervention/procedures was lower (RR=1.12; 95% CI, 1.07-1.17; I2 = 79%) or the same between weekend and weekdays (RR = 1.08; 95% CI, 1.01-1.16; I2 = 90%; Figure 3). Analyses showed a higher mortality rate on the weekends regardless of whether the illness severity was higher on the weekends (RR = 1.21; 95% CI, 1.07-1.38; I2 = 99%) or the same (RR = 1.21; 95% CI, 1.14-1.28; I2 = 99%) versus that for weekday patients (Figure 3). An inverse funnel plot for publication bias is shown in Figure 4.

DISCUSSION

We have presented one of the first meta-analyses to examine the mortality rate for hospital inpatients admitted during the weekend compared with those admitted during the workweek. We found that patients admitted on the weekends had a significantly higher overall mortality (RR = 1.19; 95% CI, 1.14-1.23; risk difference = 0.014; 95% CI, 0.013-0.016). This association was not modified by differences in weekday and weekend staffing patterns, and other hospital characteristics. Previous systematic reviews have been exclusive to the intensive care unit setting16 or did not specifically examine weekend mortality, which was a component of “off-shift” and/or “after-hours” care.17

These findings should be placed in the context of the recently published literature.18,19 A meta-analysis of cohort studies found that off-hour admission was associated with increased mortality for 28 diseases although the associations varied considerably for different diseases.18 Likewise, a meta-analysis of 21 cohort studies noted that off-hour presentation for patients with acute ischemic stroke was associated with significantly higher short-term mortality.19 Our results of increased weekend mortality corroborate that found in these two meta-analyses. However, our study differs in that we specifically examined only weekend mortality and did not include after-hours care on weekdays, which was included in the off-hour mortality in the other meta-analyses.18,19

Differences in healthcare worker staffing between weekends and weekdays have been proposed to contribute to the observed increase in mortality.7,16,20 Data indicate that lower levels of nursing are associated with increased mortality.10,21-23 The presence of less experienced and/or fewer physician specialists may contribute to increases in mortality.24-26 Fewer or less experienced staff during weekends may contribute to inadequacies in patient handovers and/or handoffs, delays in patient assessment and/or interventions, and overall continuity of care for newly admitted patients.27-33

Our data show little conclusive evidence that the weekend mortality versus weekday mortality vary by staffing level differences. While the estimated RR of mortality differs in magnitude for facilities with no difference in weekend and weekday staffing versus those that have a difference in staffing levels, both estimate an increased mortality on weekends, and the difference in these effects is not statistically significant. It should be noted that there was no difference in mortality for weekend (versus weekday) patients where there was no difference between weekend and weekday staffing; these studies were typically in high acuity units or centers where the general expectation is for 24/7/365 uniform staffing coverage.

A decrease in the use of interventions and/or procedures on weekends has been suggested to contribute to increases in mortality for patients admitted on the weekends.34 Several studies have associated lower weekend rates to higher mortality for a variety of interventions,13,35-37 although some other studies have suggested that lower procedure rates on weekends have no effect on mortality.38-40 Lower diagnostic procedure weekend rates linked to higher mortality rates may exacerbate underlying healthcare disparities.41 Our results do not conclusively show that a decrease rate of intervention and/or procedures for weekends patients is associated with a higher risk of mortality for weekends compared to weekdays.

Delays in intervention and/or procedure on weekends have also been suggested to contribute to increases in mortality.34,42 Similar to that seen with lower rates of diagnostic or therapeutic intervention and/or procedure performed on weekends, delays in potentially critical intervention and/or procedures might ultimately manifest as an increase in mortality.43 Patients admitted to the hospital on weekends and requiring an early procedure were less likely to receive it within 2 days of admission.42 Several studies have shown an association between delays in diagnostic or therapeutic intervention and/or procedure on weekends to a higher hospital inpatient mortality35,42,44,45; however, some data suggested that a delay in time to procedure on weekends may not always be associated with increased mortality.46 Depending on the procedure, there may be a threshold below which the effect of reducing delay times will have no effect on mortality rates.47,48

Patients admitted on the weekends may be different (in the severity of illness and/or comorbidities) than those admitted during the workweek and these potential differences may be a factor for increases in mortality for weekend patients. Whether there is a selection bias for weekend versus weekday patients is not clear.34 This is a complex issue as there is significant heterogeneity in patient case mix depending on the specific disease or condition studied. For instance, one would expect that weekend trauma patients would be different than those seen during the regular workweek.49 Some large scale studies suggest that weekend patients may not be more sick than weekday patients and that any increase in weekend mortality is probably not due to factors such as severity of illness.1,7 Although we were unable to determine if there was an overall difference in illness severity between weekend and weekday patients due to the wide variety of assessments used for illness severity, our results showed statistically comparable higher mortality rate on the weekends regardless of whether the illness severity was higher, the same, or mixed between weekend and weekday patients, suggesting that general illness severity per se may not be as important as the weekend effect on mortality; however, illness severity may still have an important effect on mortality for more specific subgroups (eg, trauma).49

There are several implications of our results. We found a mean increased RR mortality of approximately 19% for patients admitted on the weekends, a number similar to one of the largest published observational studies containing almost 5 million subjects.2 Even if we took a more conservative estimate of 10% increased risk of weekend mortality, this would be equivalent to an excess of 25,000 preventable deaths per year. If the weekend effect were to be placed in context of a public health issue, the weekend effect would be the number 8 cause of death below the 29,000 deaths due to gun violence, but above the 20,000 deaths resulting from sexual behavior (sexual transmitted diseases) in 2000.3, 50,51 Although our data suggest that staffing shortfalls and decreases or delays for procedures on weekends may be associated with an increased mortality for patients admitted on the weekends, further large-scale studies are needed to confirm these findings. Increasing nurse and physician staffing levels and skill mix to cover any potential shortfall on weekends may be expensive, although theoretically, there may be savings accrued from reduced adverse events and shorter length of stay.26,52 Changes to weekend care might only benefit daytime hospitalizations because some studies have shown increased mortality during nighttime regardless of weekend or weekday admission.53

Several methodologic points in our study need to be clarified. We excluded many studies which examined the relationship of off-hours or after-hours admissions and mortality as off-hours studies typically combined weekend and after-hours weekday data. Some studies suggest that off-hour admission may be associated with increased mortality and delays in time for critical procedures during off-hours.18,19 This is a complex topic, but it is clear that the risks of hospitalization vary not just by the day of the week but also by time of the day.54 The use of meta-analyses of nonrandomized trials has been somewhat controversial,55,56 and there may be significant bias or confounding in the pooling of highly varied studies. It is important to keep in mind that there are very different definitions of weekends, populations studied, and measures of mortality rates, even as the pooled statistic suggests a homogeneity among the studies that does not exist.

There are several limitations to our study. Our systematic review may be seen as limited as we included only English language papers. In addition, we did not search nontraditional sources and abstracts. We accepted the definition of a weekend as defined by the original study, which resulted in varied definitions of weekend time period and mortality. There was a lack of specific data on staffing patterns and procedures in many studies, particularly those using databases. We were not able to further subdivide our analysis by admitting service. We were not able to undertake a subgroup analysis by country or continent, which may have implications on the effect of different healthcare systems on healthcare quality. It is unclear whether correlations in our study are a direct consequence of poorer weekend care or are the result of other unknown or unexamined differences between weekend and weekday patient populations.34,57 For instance, there may be other global factors (higher rates of medical errors, higher hospital volumes) which may not be specifically related to weekend care and therefore not been accounted for in many of the studies we examined.10,27,58-61 There may be potential bias of patient phenotypes (are weekend patients different than weekday patients?) admitted on the weekend. Holidays were included in the weekend data and it is not clear how this would affect our findings as some data suggest that there is a significantly higher mortality rate on holidays (versus weekends or weekdays),61 while other data do not.62 There was no universal definition for the timeframe for a weekend and as such, we had to rely on the original article for their determination and definition of weekend versus weekday death.

In summary, our meta-analysis suggests that hospital inpatients admitted during the weekend have a significantly increased mortality compared with those admitted on weekday. While none of our subgroup analyses showed strong evidence on effect modification, the interpretation of these results is hampered by the relatively small number of studies. Further research should be directed to determine the presence of causality between various factors purported to affect mortality and it is possible that we ultimately find that the weekend effect may exist for some but not all patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Jaime Blanck, MLIS, MPA, AHIP, Clinical Informationist, Welch Medical Library, for her invaluable assistance in undertaking the literature searches for this manuscript.

Disclosure

This manuscript has been supported by the Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine; The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine; Baltimore, Maryland. There are no relevant conflicts of interests.

1. Aylin P, Yunus A, Bottle A, Majeed A, Bell D. Weekend mortality for emergency

admissions. A large, multicentre study. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(3):213-217. PubMed

2. Handel AE, Patel SV, Skingsley A, Bramley K, Sobieski R, Ramagopalan SV.

Weekend admissions as an independent predictor of mortality: an analysis of

Scottish hospital admissions. BMJ Open. 2012;2(6): pii: e001789. PubMed

3. Ricciardi R, Roberts PL, Read TE, Baxter NN, Marcello PW, Schoetz DJ. Mortality

rate after nonelective hospital admission. Arch Surg. 2011;146(5):545-551. PubMed

4. Fonarow GC, Abraham WT, Albert NM, et al. Day of admission and clinical

outcomes for patients hospitalized for heart failure: findings from the Organized

Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients With Heart

Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF). Circ Heart Fail. 2008;1(1):50-57. PubMed

5. Hoh BL, Chi YY, Waters MF, Mocco J, Barker FG 2nd. Effect of weekend compared

with weekday stroke admission on thrombolytic use, in-hospital mortality,

discharge disposition, hospital charges, and length of stay in the Nationwide Inpatient

Sample Database, 2002 to 2007. Stroke. 2010;41(10):2323-2328. PubMed

6. Koike S, Tanabe S, Ogawa T, et al. Effect of time and day of admission on 1-month

survival and neurologically favourable 1-month survival in out-of-hospital cardiopulmonary

arrest patients. Resuscitation. 2011;82(7):863-868. PubMed

7. Bell CM, Redelmeier DA. Mortality among patients admitted to hospitals on

weekends as compared with weekdays. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(9):663-668. PubMed

8. Freemantle N, Richardson M, Wood J, et al. Weekend hospitalization and additional

risk of death: an analysis of inpatient data. J R Soc Med. 2012;105(2):74-84. PubMed

9. Schilling PL, Campbell DA Jr, Englesbe MJ, Davis MM. A comparison of in-hospital

mortality risk conferred by high hospital occupancy, differences in nurse

staffing levels, weekend admission, and seasonal influenza. Med Care. 2010;48(3):

224-232. PubMed

10. Wong HJ, Morra D. Excellent hospital care for all: open and operating 24/7. J Gen

Intern Med. 2011;26(9):1050-1052. PubMed

11. Dorn SD, Shah ND, Berg BP, Naessens JM. Effect of weekend hospital admission

on gastrointestinal hemorrhage outcomes. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(6):1658-1666. PubMed

12. Kostis WJ, Demissie K, Marcella SW, et al. Weekend versus weekday admission

and mortality from myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(11):1099-1109. PubMed

13. McKinney JS, Deng Y, Kasner SE, Kostis JB; Myocardial Infarction Data Acquisition

System (MIDAS 15) Study Group. Comprehensive stroke centers overcome

the weekend versus weekday gap in stroke treatment and mortality. Stroke.

2011;42(9):2403-2409. PubMed

14. Margulis AV, Pladevall M, Riera-Guardia N, et al. Quality assessment of observational

studies in a drug-safety systematic review, comparison of two tools: the

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale and the RTI item bank. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:359-368. PubMed

15. Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat

Softw. 2010;36(3):1-48.

16. Cavallazzi R, Marik PE, Hirani A, Pachinburavan M, Vasu TS, Leiby BE. Association