User login

Preventing drinking relapse in patients with alcoholic liver disease

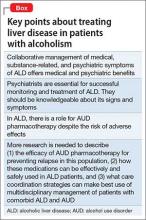

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a mosaic of psychiatric and medical symptoms. Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) in its acute and chronic forms is a common clinical consequence of long-standing AUD. Patients with ALD require specialized care from professionals in addiction, gastroenterology, and psychiatry. However, medical specialists treating ALD might not regularly consider medications to treat AUD because of their limited experience with the drugs or the lack of studies in patients with significant liver disease.1 Similarly, psychiatrists might be reticent to prescribe medications for AUD, fearing that liver disease will be made worse or that they will cause other medical complications. As a result, patients with ALD might not receive care that could help treat their AUD (Box).

Given the high worldwide prevalence and morbidity of ALD,2 general and subspecialized psychiatrists routinely evaluate patients with AUD in and out of the hospital. This article aims to equip a psychiatrist with:

• a practical understanding of the natural history and categorization of ALD

• basic skills to detect symptoms of ALD

• preparation to collaborate with medical colleagues in multidisciplinary management of co-occurring AUD and ALD

• a summary of the pharmacotherapeutics of AUD, with emphasis on patients with clinically apparent ALD.

Categorization and clinical features

Alcoholic liver damage encompasses a spectrum of disorders, including alcoholic fatty liver, acute alcohol hepatitis (AH), and cirrhosis following varying durations and patterns of alcohol use. Manifestations of ALD vary from asymptomatic fatty liver with minimal liver enzyme elevation to severe acute AH with jaundice, coagulopathy, and high short-term mortality (Table 1). Symptoms seen in patients with AH include fever, abdominal pain, anorexia, jaundice, leukocytosis, and coagulopathy.3

Patients with chronic ALD often develop cirrhosis, persistent elevation of the serum aminotransferase level (even after prolonged alcohol abstinence), signs of portal hypertension (ascites, encephalopathy, variceal bleeding), and profound malnutrition. The survival of ALD patients with chronic liver failure is predicted in part by a Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score that incorporates their serum total bilirubin level, creatinine level, and international normalized ratio. The MELD score, which ranges from 6 to 40, also is used to gauge the need for liver transplantation; most patients who have a MELD score >15 benefit from transplant. To definitively determine the severity of ALD, a liver biopsy is required but usually is not performed in clinical practice.

All patients who drink heavily or suffer with AUD are at risk of developing AH; women and binge drinkers are particularly vulnerable.4 Liver dysfunction and malnutrition in ALD patients compromise the immune system, increasing the risk of infection. Patients hospitalized with AH have a 10% to 30% risk of inpatient mortality; their 1- and 2-month post-discharge survival is 50% to 65%, largely determined by whether the patient can maintain sobriety.5 Psychiatrists’ contribution to ALD treatment therefore has the potential to save lives.

Screening and detection of ALD

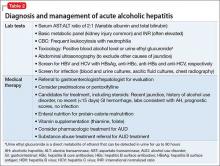

Because of the high mortality associated with AH and cirrhosis, symptom recognition and collaborative medical and psychiatric management are critical (Table 2). A psychiatrist evaluating a jaundiced patient who continues to drink should arrange urgent medical evaluation. While gathering a history, mental health providers might hear a patient refer to symptoms of gastrointestinal bleeding (vomiting blood, bloody or dark stool), painful abdominal distension, fevers, or confusion that should prompt a referral to a gastroenterologist or the emergency department. Testing for urinary ethyl glucuronide—a direct metabolite of ethanol that can be detected for as long as 90 hours after ethanol ingestion—is useful in detecting alcohol use in the past 4 or 5 days.

Medical management of ALD

Corticosteroids are a mainstay in pharmacotherapy for severe AH. There is evidence for improved outcomes in patients with severe AH treated with prednisolone for 4 to 6 weeks.5 Prognostic models such as the Maddrey’s Discriminant Function, Lille Model, and the MELD score help determine the need for steroid use and identify high-risk patients. Patients with active infection or bleeding are not a candidate for steroid treatment. An experienced gastroenterologist or hepatologist should initiate medical intervention after thorough evaluation.

Liver transplantation. A select group of patients with refractory liver failure are considered for liver transplantation. Although transplant programs differ in their criteria for organ listing, many require patients to demonstrate at least 6 months of verified abstinence from alcohol and illicit drugs as well as adherence to a formal AUD treatment and rehabilitation plan. The patient’s psychological health and prognosis for sustained sobriety are central to candidacy for organ listing, which highlights the key role of psychiatrists.

Further considerations. Thiamine and folate often are given to patients with ALD. Abdominal imaging and screening for HIV and viral hepatitis—identified in 10% to 20% of ALD patients—is routine. Alcohol abstinence remains central to survival because relapse increases the risk of recurrent, severe liver disease. Regrettably, many physical symptoms of liver disease, such as portal hypertension, ascites, and jaundice, can take months to improve with abstinence.

Treating AUD in patients with ALD

Successful treatment is multifaceted and includes more than just medications. Initial management often includes addressing alcohol withdrawal in dependent patients.6

Behavioral interventions are effective and indispensable components in preventing relapse,7 including a written relapse prevention plan that formally outlines the patient’s commitment to change, identifies triggers, and outlines a discrete plan of action. Primary psychiatric pathology, including depression and anxiety, often are comorbid with AUD; concurrent treatment of these disorders could improve patient outcomes.8

Benzodiazepines often are used during acute alcohol withdrawal. They should not be used for relapse prevention in ALD because of their additive interactions with alcohol, cognitive and psychomotor side effects, and abuse potential.9,10 Many of these drugs are cleared by the liver and generally are not recommended for use in patients with ALD.

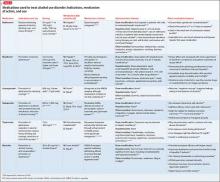

Other agents, further considerations. Drug trials in AUD largely have been conducted in small, heterogeneous populations and revealed modest and, at times, conflicting drug effect sizes.6,11,12 The placebo effect among the AUD population is pronounced.6,7,13 Despite these caveats, several agents have been studied and validated by the FDA to treat AUD. Additional agents with promising pilot data are being investigated. Table 31,7,10,11,13-43 summarizes drugs used to treat AUD—those with and without FDA approval—with a focus on how they might be used in patients with ALD. Of note, several of these agents do not rely on the liver for metabolism or excretion.

There is no agreed-upon algorithm or safety profile to guide a prescriber’s decision making about drug or dosage choices when treating AUD in patients with ALD. Because liver function can vary among patients as well as during an individual patient’s disease course, treatment decisions should be made on a clinical, collaborative, and case-by-case basis.

That being said, the AUD treatment literature suggests that specific drugs might be more useful in patients with varying severity of disease and during different phases of recovery:

• Acamprosate has been found to be effective in supporting abstinence in sober patients.14,44

• Naltrexone has been shown to be useful in patients with severe alcohol cravings. By modulating alcohol’s rewarding effects, naltrexone also reduces heavy alcohol consumption in patients who are drinking.14,15,44

• Disulfiram generally is not recommended for use in patients with clinically apparent hepatic insufficiency, such as decompensated cirrhosis or preexisting jaundice.

Although alcohol abstinence remains the treatment goal and a requirement for liver transplant, providers must recognize that some patients might not be able to maintain long-term sobriety. Therefore, harm reduction models are important companions to abstinence-only models of AUD treatment.45 The array of behavioral, pharmacological, and philosophical approaches to AUD treatment underlines the need for an individualized approach to relapse prevention.

Collaboration between medicine and psychiatry

When AUD and ALD are comorbid, psychiatrists might worry about making the patient’s medical condition worse by prescribing additional psychoactive medications—particularly ones that are cleared by the liver. Remember that AUD confers a substantial mortality rate that is more than 3 times that of the general population, along with severe medical46 and psychosocial31 effects. Although prescribers must remain vigilant for adverse drug effects, medications easily can be blamed for what might be the natural progression and symptoms of AUD in patients with ALD.26 This erroneous conclusion can lead to premature medication discontinuation and under-treatment of AUD.

In the end, keeping the patient sober and mentally well might be more beneficial than eliminating the burden of any medication side effects. Collaborative medical and psychiatric management of ALD patients can ensure that clinicians properly weigh the risks, benefits, and duration of treatment unique to each patient.

Starting AUD treatment promptly after alcohol relapse is essential and entails a multidisciplinary effort between medicine and psychiatry, both in and out of the hospital. Because the relapsing, ill ALD patient most often will be admitted to a medical specialist, AUD might not receive enough attention during the medical admission. Psychiatrists can help in initiating AUD treatment in the acute medical setting, which has been shown to improve the outpatient course.6 For medically stable ALD patients admitted for inpatient psychiatric care or presenting a clinic, the mental health clinician should be aware of key laboratory and physical exam findings.

Bottom Line

Patients with alcoholic liver disease (ALD) require collaborative care from specialists in addiction, gastroenterology, and psychiatry. Psychiatrists have a role in identifying signs of ALD, prescribing medication to treat alcohol use disorder, and encouraging abstinence. There is some evidence supporting specific medications for varying severity of disease and different phases of recovery. Pharmacotherapy decisions should be made case by case.

Related Resources

• Khan A, Tansel A, White DL, et al. Efficacy of psychosocial interventions in inducing and maintaining alcohol abstinence in patients with chronic liver disease: a systematic review [published online August 6, 2015]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.07.047.

• Vuittonet CL, Halse M, Leggio L, et al. Pharmacotherapy for alcoholic patients with alcoholic liver disease. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71(15):1265-1276.

Drug Brand Names

Acamprosate • Campral

Baclofen • Lioresal

Disulfiram • Antabuse

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Naltrexone • ReVia, Vivitrol

Pentoxifylline • Trental

Prednisolone • Prelone

Rifaximin • Xifaxan

Topiramate • Topamax

Disclosures

Dr. Winder and Dr. Mellinger report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products. Dr. Fontana receives research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb, Gilead, and Janssen and consults for the Chronic Liver Disease Foundation.

1. Gache P, Hadengue A. Baclofen improves abstinence in alcoholic cirrhosis: still better to come? J Hepatol. 2008;49(6):1083-1085.

2. Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, et al. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373(9682):2223-2233.

3. Singal AK, Kamath PS, Gores GJ, et al. Alcoholic hepatitis: current challenges and future directions. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(4):555-564; quiz e31-32.

4. Becker U, Deis A, Sørensen TI, et al. Prediction of risk of liver disease by alcohol intake, sex, and age: a prospective population study. Hepatology. 1996;23(5):1025-1029.

5. Mathurin P, Lucey MR. Management of alcoholic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2012;56(suppl 1):S39-S45.

6. Mann K, Lemenager T, Hoffmann S, et al; PREDICT Study Team. Results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled pharmacotherapy trial in alcoholism conducted in Germany and comparison with the US COMBINE study. Addict Biol. 2013;18(6):937-946.

7. Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, et al; COMBINE Study Research Group. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(17):2003-2017.

8. Kranzler HR, Rosenthal RN. Dual diagnosis: alcoholism and co-morbid psychiatric disorders. Am J Addict. 2003;12(suppl 1):S26-S40.

9. Book SW, Myrick H. Novel anticonvulsants in the treatment of alcoholism. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2005;14(4):371-376.

10. Furieri FA, Nakamura-Palacios EM. Gabapentin reduces alcohol consumption and craving: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(11):1691-1700.

11. Blodgett JC, Del Re AC, Maisel NC, et al. A meta-analysis of topiramate’s effects for individuals with alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38(6):1481-1488.

12. Krystal JH, Cramer JA, Krol WF, et al; Veterans Affairs Naltrexone Cooperative Study 425 Group. Naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(24):1734-1739.

13. Petrakis IL, Poling J, Levinson C, et al; VA New England VISN I MIRECC Study Group. Naltrexone and disulfiram in patients with alcohol dependence and comorbid psychiatric disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57(10):1128-1137.

14. Maisel NC, Blodgett JC, Wilbourne PL, et al. Meta-analysis of naltrexone and acamprosate for treating alcohol use disorders: when are these medications most helpful? Addiction. 2013;108(2):275-293.

15. Pettinati HM, O’Brien CP, Rabinowitz AR, et al. The status of naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence: specific effects on heavy drinking. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;26(6):610-625.

16. Anton RF, Myrick H, Wright TM, et al. Gabapentin combined with naltrexone for the treatment of alcohol dependence. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(7):709-717.

17. Srisurapanont M, Jarusuraisin N. Opioid antagonists for alcohol dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005(1):CD001867.

18. Naltrexone. 2014. http://www.micromedexsolutions.com. Accessed January 31, 2015.

19. Soyka M, Chick J. Use of acamprosate and opioid antagonists in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a European perspective. Am J Addict. 2003;12(suppl 1):S69-S80.

20. Turncliff RZ, Dunbar JL, Dong Q, et al. Pharmacokinetics of long-acting naltrexone in subjects with mild to moderate hepatic impairment. J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;45(11):1259-1267.

21. United States National Library of Medicine. Naltrexone. http://livertox.nlm.nih.gov/Naltrexone.htm. Updated September 30, 2015. Accessed November 10, 2015.

22. Terg R, Coronel E, Sordá J, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral naltrexone treatment for pruritus of cholestasis, a crossover, double blind, placebo-controlled study. J Hepatol. 2002;37(6):717-722.

23. Skinner MD, Lahmek P, Pham H, et al. Disulfiram efficacy in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a meta-analysis [published online February 10, 2014]. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e87366. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087366.

24. Disulfiram. 2014. http://www.micromedexsolutions.com. Accessed January 31, 2015.

25. Björnsson E, Nordlinder H, Olsson R. Clinical characteristics and prognostic markers in disulfiram-induced liver injury. J Hepatol. 2006;44(4):791-797.

26. Chick J. Safety issues concerning the use of disulfiram in treating alcohol dependence. Drug Saf. 1999;20(5):427-435.

27. Campral [package insert]. St. Louis, MO: Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2012.

28. Brower KJ, Myra Kim H, Strobbe S, et al. A randomized double-blind pilot trial of gabapentin versus placebo to treat alcohol dependence and comorbid insomnia. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(8):1429-1438.

29. Mason BJ, Quello S, Goodell V, et al. Gabapentin treatment for alcohol dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(1):70-77.

30. Neurontin [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer; 2015.

31. Johnson BA, Ait-Daoud N, Akhtar FZ, et al. Oral topiramate reduces the consequences of drinking and improves the quality of life of alcohol-dependent individuals: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(9):905-912.

32. Paparrigopoulos T, Tzavellas E, Karaiskos D, et al. Treatment of alcohol dependence with low-dose topiramate: an open-label controlled study. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:41.

33. Rubio G, Ponce G, Jiménez-Arriero MA, et al. Effects of topiramate in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2004;37(1):37-40.

34. Topamax [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals; 2009.

35. De Sousa AA, De Sousa J, Kapoor H. An open randomized trial comparing disulfiram and topiramate in the treatment of alcohol dependence. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;34(4):460-463.

36. Kampman KM, Pettinati HM, Lynch KG, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of topiramate for the treatment of comorbid cocaine and alcohol dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133(1):94-99.

37. Addolorato G, Leggio L, Ferrulli A, et al. Dose-response effect of baclofen in reducing daily alcohol intake in alcohol dependence: secondary analysis of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Alcohol Alcohol. 2011;46(3):312-317.

38. Balcofen [package insert]. Concord, NC: McKesson Packing Services; 2013.

39. United States National Library of Medicine. Baclofen. 2015. http://livertox.nlm.nih.gov/Baclofen.htm. Accessed November 7, 2015.

40. Addolorato G, Leggio L, Ferrulli A, et al. Effectiveness and safety of baclofen for maintenance of alcohol abstinence in alcohol-dependent patients with liver cirrhosis: randomised, double-blind controlled study. Lancet. 2007;370(9603):1915-1922.

41. Leggio L, Ferrulli A, Zambon A, et al. Baclofen promotes alcohol abstinence in alcohol dependent cirrhotic patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Addict Behav. 2012;37(4):561-564.

42. Franchitto N, Pelissier F, Lauque D, et al. Self-intoxication with baclofen in alcohol-dependent patients with co-existing psychiatric illness: an emergency department case series. Alcohol Alcohol. 2014;49(1):79-83.

43. Brennan JL, Leung JG, Gagliardi JP, et al. Clinical effectiveness of baclofen for the treatment of alcohol dependence: a review. Clin Pharmacol. 2013;5:99-107.

44. Rösner S, Leucht S, Lehert P, et al. Acamprosate supports abstinence, naltrexone prevents excessive drinking: evidence from a meta-analysis with unreported outcomes. J Psychopharmacol. 2008;22(1):11-23.

45. Marlatt GA, Witkiewitz K. Harm reduction approaches to alcohol use: health promotion, prevention, and treatment. Addict Behav. 2002;27(6):867-886.

46. O’Shea RS, Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ. Alcoholic liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(1):14-32; quiz 33.

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a mosaic of psychiatric and medical symptoms. Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) in its acute and chronic forms is a common clinical consequence of long-standing AUD. Patients with ALD require specialized care from professionals in addiction, gastroenterology, and psychiatry. However, medical specialists treating ALD might not regularly consider medications to treat AUD because of their limited experience with the drugs or the lack of studies in patients with significant liver disease.1 Similarly, psychiatrists might be reticent to prescribe medications for AUD, fearing that liver disease will be made worse or that they will cause other medical complications. As a result, patients with ALD might not receive care that could help treat their AUD (Box).

Given the high worldwide prevalence and morbidity of ALD,2 general and subspecialized psychiatrists routinely evaluate patients with AUD in and out of the hospital. This article aims to equip a psychiatrist with:

• a practical understanding of the natural history and categorization of ALD

• basic skills to detect symptoms of ALD

• preparation to collaborate with medical colleagues in multidisciplinary management of co-occurring AUD and ALD

• a summary of the pharmacotherapeutics of AUD, with emphasis on patients with clinically apparent ALD.

Categorization and clinical features

Alcoholic liver damage encompasses a spectrum of disorders, including alcoholic fatty liver, acute alcohol hepatitis (AH), and cirrhosis following varying durations and patterns of alcohol use. Manifestations of ALD vary from asymptomatic fatty liver with minimal liver enzyme elevation to severe acute AH with jaundice, coagulopathy, and high short-term mortality (Table 1). Symptoms seen in patients with AH include fever, abdominal pain, anorexia, jaundice, leukocytosis, and coagulopathy.3

Patients with chronic ALD often develop cirrhosis, persistent elevation of the serum aminotransferase level (even after prolonged alcohol abstinence), signs of portal hypertension (ascites, encephalopathy, variceal bleeding), and profound malnutrition. The survival of ALD patients with chronic liver failure is predicted in part by a Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score that incorporates their serum total bilirubin level, creatinine level, and international normalized ratio. The MELD score, which ranges from 6 to 40, also is used to gauge the need for liver transplantation; most patients who have a MELD score >15 benefit from transplant. To definitively determine the severity of ALD, a liver biopsy is required but usually is not performed in clinical practice.

All patients who drink heavily or suffer with AUD are at risk of developing AH; women and binge drinkers are particularly vulnerable.4 Liver dysfunction and malnutrition in ALD patients compromise the immune system, increasing the risk of infection. Patients hospitalized with AH have a 10% to 30% risk of inpatient mortality; their 1- and 2-month post-discharge survival is 50% to 65%, largely determined by whether the patient can maintain sobriety.5 Psychiatrists’ contribution to ALD treatment therefore has the potential to save lives.

Screening and detection of ALD

Because of the high mortality associated with AH and cirrhosis, symptom recognition and collaborative medical and psychiatric management are critical (Table 2). A psychiatrist evaluating a jaundiced patient who continues to drink should arrange urgent medical evaluation. While gathering a history, mental health providers might hear a patient refer to symptoms of gastrointestinal bleeding (vomiting blood, bloody or dark stool), painful abdominal distension, fevers, or confusion that should prompt a referral to a gastroenterologist or the emergency department. Testing for urinary ethyl glucuronide—a direct metabolite of ethanol that can be detected for as long as 90 hours after ethanol ingestion—is useful in detecting alcohol use in the past 4 or 5 days.

Medical management of ALD

Corticosteroids are a mainstay in pharmacotherapy for severe AH. There is evidence for improved outcomes in patients with severe AH treated with prednisolone for 4 to 6 weeks.5 Prognostic models such as the Maddrey’s Discriminant Function, Lille Model, and the MELD score help determine the need for steroid use and identify high-risk patients. Patients with active infection or bleeding are not a candidate for steroid treatment. An experienced gastroenterologist or hepatologist should initiate medical intervention after thorough evaluation.

Liver transplantation. A select group of patients with refractory liver failure are considered for liver transplantation. Although transplant programs differ in their criteria for organ listing, many require patients to demonstrate at least 6 months of verified abstinence from alcohol and illicit drugs as well as adherence to a formal AUD treatment and rehabilitation plan. The patient’s psychological health and prognosis for sustained sobriety are central to candidacy for organ listing, which highlights the key role of psychiatrists.

Further considerations. Thiamine and folate often are given to patients with ALD. Abdominal imaging and screening for HIV and viral hepatitis—identified in 10% to 20% of ALD patients—is routine. Alcohol abstinence remains central to survival because relapse increases the risk of recurrent, severe liver disease. Regrettably, many physical symptoms of liver disease, such as portal hypertension, ascites, and jaundice, can take months to improve with abstinence.

Treating AUD in patients with ALD

Successful treatment is multifaceted and includes more than just medications. Initial management often includes addressing alcohol withdrawal in dependent patients.6

Behavioral interventions are effective and indispensable components in preventing relapse,7 including a written relapse prevention plan that formally outlines the patient’s commitment to change, identifies triggers, and outlines a discrete plan of action. Primary psychiatric pathology, including depression and anxiety, often are comorbid with AUD; concurrent treatment of these disorders could improve patient outcomes.8

Benzodiazepines often are used during acute alcohol withdrawal. They should not be used for relapse prevention in ALD because of their additive interactions with alcohol, cognitive and psychomotor side effects, and abuse potential.9,10 Many of these drugs are cleared by the liver and generally are not recommended for use in patients with ALD.

Other agents, further considerations. Drug trials in AUD largely have been conducted in small, heterogeneous populations and revealed modest and, at times, conflicting drug effect sizes.6,11,12 The placebo effect among the AUD population is pronounced.6,7,13 Despite these caveats, several agents have been studied and validated by the FDA to treat AUD. Additional agents with promising pilot data are being investigated. Table 31,7,10,11,13-43 summarizes drugs used to treat AUD—those with and without FDA approval—with a focus on how they might be used in patients with ALD. Of note, several of these agents do not rely on the liver for metabolism or excretion.

There is no agreed-upon algorithm or safety profile to guide a prescriber’s decision making about drug or dosage choices when treating AUD in patients with ALD. Because liver function can vary among patients as well as during an individual patient’s disease course, treatment decisions should be made on a clinical, collaborative, and case-by-case basis.

That being said, the AUD treatment literature suggests that specific drugs might be more useful in patients with varying severity of disease and during different phases of recovery:

• Acamprosate has been found to be effective in supporting abstinence in sober patients.14,44

• Naltrexone has been shown to be useful in patients with severe alcohol cravings. By modulating alcohol’s rewarding effects, naltrexone also reduces heavy alcohol consumption in patients who are drinking.14,15,44

• Disulfiram generally is not recommended for use in patients with clinically apparent hepatic insufficiency, such as decompensated cirrhosis or preexisting jaundice.

Although alcohol abstinence remains the treatment goal and a requirement for liver transplant, providers must recognize that some patients might not be able to maintain long-term sobriety. Therefore, harm reduction models are important companions to abstinence-only models of AUD treatment.45 The array of behavioral, pharmacological, and philosophical approaches to AUD treatment underlines the need for an individualized approach to relapse prevention.

Collaboration between medicine and psychiatry

When AUD and ALD are comorbid, psychiatrists might worry about making the patient’s medical condition worse by prescribing additional psychoactive medications—particularly ones that are cleared by the liver. Remember that AUD confers a substantial mortality rate that is more than 3 times that of the general population, along with severe medical46 and psychosocial31 effects. Although prescribers must remain vigilant for adverse drug effects, medications easily can be blamed for what might be the natural progression and symptoms of AUD in patients with ALD.26 This erroneous conclusion can lead to premature medication discontinuation and under-treatment of AUD.

In the end, keeping the patient sober and mentally well might be more beneficial than eliminating the burden of any medication side effects. Collaborative medical and psychiatric management of ALD patients can ensure that clinicians properly weigh the risks, benefits, and duration of treatment unique to each patient.

Starting AUD treatment promptly after alcohol relapse is essential and entails a multidisciplinary effort between medicine and psychiatry, both in and out of the hospital. Because the relapsing, ill ALD patient most often will be admitted to a medical specialist, AUD might not receive enough attention during the medical admission. Psychiatrists can help in initiating AUD treatment in the acute medical setting, which has been shown to improve the outpatient course.6 For medically stable ALD patients admitted for inpatient psychiatric care or presenting a clinic, the mental health clinician should be aware of key laboratory and physical exam findings.

Bottom Line

Patients with alcoholic liver disease (ALD) require collaborative care from specialists in addiction, gastroenterology, and psychiatry. Psychiatrists have a role in identifying signs of ALD, prescribing medication to treat alcohol use disorder, and encouraging abstinence. There is some evidence supporting specific medications for varying severity of disease and different phases of recovery. Pharmacotherapy decisions should be made case by case.

Related Resources

• Khan A, Tansel A, White DL, et al. Efficacy of psychosocial interventions in inducing and maintaining alcohol abstinence in patients with chronic liver disease: a systematic review [published online August 6, 2015]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.07.047.

• Vuittonet CL, Halse M, Leggio L, et al. Pharmacotherapy for alcoholic patients with alcoholic liver disease. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71(15):1265-1276.

Drug Brand Names

Acamprosate • Campral

Baclofen • Lioresal

Disulfiram • Antabuse

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Naltrexone • ReVia, Vivitrol

Pentoxifylline • Trental

Prednisolone • Prelone

Rifaximin • Xifaxan

Topiramate • Topamax

Disclosures

Dr. Winder and Dr. Mellinger report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products. Dr. Fontana receives research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb, Gilead, and Janssen and consults for the Chronic Liver Disease Foundation.

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a mosaic of psychiatric and medical symptoms. Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) in its acute and chronic forms is a common clinical consequence of long-standing AUD. Patients with ALD require specialized care from professionals in addiction, gastroenterology, and psychiatry. However, medical specialists treating ALD might not regularly consider medications to treat AUD because of their limited experience with the drugs or the lack of studies in patients with significant liver disease.1 Similarly, psychiatrists might be reticent to prescribe medications for AUD, fearing that liver disease will be made worse or that they will cause other medical complications. As a result, patients with ALD might not receive care that could help treat their AUD (Box).

Given the high worldwide prevalence and morbidity of ALD,2 general and subspecialized psychiatrists routinely evaluate patients with AUD in and out of the hospital. This article aims to equip a psychiatrist with:

• a practical understanding of the natural history and categorization of ALD

• basic skills to detect symptoms of ALD

• preparation to collaborate with medical colleagues in multidisciplinary management of co-occurring AUD and ALD

• a summary of the pharmacotherapeutics of AUD, with emphasis on patients with clinically apparent ALD.

Categorization and clinical features

Alcoholic liver damage encompasses a spectrum of disorders, including alcoholic fatty liver, acute alcohol hepatitis (AH), and cirrhosis following varying durations and patterns of alcohol use. Manifestations of ALD vary from asymptomatic fatty liver with minimal liver enzyme elevation to severe acute AH with jaundice, coagulopathy, and high short-term mortality (Table 1). Symptoms seen in patients with AH include fever, abdominal pain, anorexia, jaundice, leukocytosis, and coagulopathy.3

Patients with chronic ALD often develop cirrhosis, persistent elevation of the serum aminotransferase level (even after prolonged alcohol abstinence), signs of portal hypertension (ascites, encephalopathy, variceal bleeding), and profound malnutrition. The survival of ALD patients with chronic liver failure is predicted in part by a Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score that incorporates their serum total bilirubin level, creatinine level, and international normalized ratio. The MELD score, which ranges from 6 to 40, also is used to gauge the need for liver transplantation; most patients who have a MELD score >15 benefit from transplant. To definitively determine the severity of ALD, a liver biopsy is required but usually is not performed in clinical practice.

All patients who drink heavily or suffer with AUD are at risk of developing AH; women and binge drinkers are particularly vulnerable.4 Liver dysfunction and malnutrition in ALD patients compromise the immune system, increasing the risk of infection. Patients hospitalized with AH have a 10% to 30% risk of inpatient mortality; their 1- and 2-month post-discharge survival is 50% to 65%, largely determined by whether the patient can maintain sobriety.5 Psychiatrists’ contribution to ALD treatment therefore has the potential to save lives.

Screening and detection of ALD

Because of the high mortality associated with AH and cirrhosis, symptom recognition and collaborative medical and psychiatric management are critical (Table 2). A psychiatrist evaluating a jaundiced patient who continues to drink should arrange urgent medical evaluation. While gathering a history, mental health providers might hear a patient refer to symptoms of gastrointestinal bleeding (vomiting blood, bloody or dark stool), painful abdominal distension, fevers, or confusion that should prompt a referral to a gastroenterologist or the emergency department. Testing for urinary ethyl glucuronide—a direct metabolite of ethanol that can be detected for as long as 90 hours after ethanol ingestion—is useful in detecting alcohol use in the past 4 or 5 days.

Medical management of ALD

Corticosteroids are a mainstay in pharmacotherapy for severe AH. There is evidence for improved outcomes in patients with severe AH treated with prednisolone for 4 to 6 weeks.5 Prognostic models such as the Maddrey’s Discriminant Function, Lille Model, and the MELD score help determine the need for steroid use and identify high-risk patients. Patients with active infection or bleeding are not a candidate for steroid treatment. An experienced gastroenterologist or hepatologist should initiate medical intervention after thorough evaluation.

Liver transplantation. A select group of patients with refractory liver failure are considered for liver transplantation. Although transplant programs differ in their criteria for organ listing, many require patients to demonstrate at least 6 months of verified abstinence from alcohol and illicit drugs as well as adherence to a formal AUD treatment and rehabilitation plan. The patient’s psychological health and prognosis for sustained sobriety are central to candidacy for organ listing, which highlights the key role of psychiatrists.

Further considerations. Thiamine and folate often are given to patients with ALD. Abdominal imaging and screening for HIV and viral hepatitis—identified in 10% to 20% of ALD patients—is routine. Alcohol abstinence remains central to survival because relapse increases the risk of recurrent, severe liver disease. Regrettably, many physical symptoms of liver disease, such as portal hypertension, ascites, and jaundice, can take months to improve with abstinence.

Treating AUD in patients with ALD

Successful treatment is multifaceted and includes more than just medications. Initial management often includes addressing alcohol withdrawal in dependent patients.6

Behavioral interventions are effective and indispensable components in preventing relapse,7 including a written relapse prevention plan that formally outlines the patient’s commitment to change, identifies triggers, and outlines a discrete plan of action. Primary psychiatric pathology, including depression and anxiety, often are comorbid with AUD; concurrent treatment of these disorders could improve patient outcomes.8

Benzodiazepines often are used during acute alcohol withdrawal. They should not be used for relapse prevention in ALD because of their additive interactions with alcohol, cognitive and psychomotor side effects, and abuse potential.9,10 Many of these drugs are cleared by the liver and generally are not recommended for use in patients with ALD.

Other agents, further considerations. Drug trials in AUD largely have been conducted in small, heterogeneous populations and revealed modest and, at times, conflicting drug effect sizes.6,11,12 The placebo effect among the AUD population is pronounced.6,7,13 Despite these caveats, several agents have been studied and validated by the FDA to treat AUD. Additional agents with promising pilot data are being investigated. Table 31,7,10,11,13-43 summarizes drugs used to treat AUD—those with and without FDA approval—with a focus on how they might be used in patients with ALD. Of note, several of these agents do not rely on the liver for metabolism or excretion.

There is no agreed-upon algorithm or safety profile to guide a prescriber’s decision making about drug or dosage choices when treating AUD in patients with ALD. Because liver function can vary among patients as well as during an individual patient’s disease course, treatment decisions should be made on a clinical, collaborative, and case-by-case basis.

That being said, the AUD treatment literature suggests that specific drugs might be more useful in patients with varying severity of disease and during different phases of recovery:

• Acamprosate has been found to be effective in supporting abstinence in sober patients.14,44

• Naltrexone has been shown to be useful in patients with severe alcohol cravings. By modulating alcohol’s rewarding effects, naltrexone also reduces heavy alcohol consumption in patients who are drinking.14,15,44

• Disulfiram generally is not recommended for use in patients with clinically apparent hepatic insufficiency, such as decompensated cirrhosis or preexisting jaundice.

Although alcohol abstinence remains the treatment goal and a requirement for liver transplant, providers must recognize that some patients might not be able to maintain long-term sobriety. Therefore, harm reduction models are important companions to abstinence-only models of AUD treatment.45 The array of behavioral, pharmacological, and philosophical approaches to AUD treatment underlines the need for an individualized approach to relapse prevention.

Collaboration between medicine and psychiatry

When AUD and ALD are comorbid, psychiatrists might worry about making the patient’s medical condition worse by prescribing additional psychoactive medications—particularly ones that are cleared by the liver. Remember that AUD confers a substantial mortality rate that is more than 3 times that of the general population, along with severe medical46 and psychosocial31 effects. Although prescribers must remain vigilant for adverse drug effects, medications easily can be blamed for what might be the natural progression and symptoms of AUD in patients with ALD.26 This erroneous conclusion can lead to premature medication discontinuation and under-treatment of AUD.

In the end, keeping the patient sober and mentally well might be more beneficial than eliminating the burden of any medication side effects. Collaborative medical and psychiatric management of ALD patients can ensure that clinicians properly weigh the risks, benefits, and duration of treatment unique to each patient.

Starting AUD treatment promptly after alcohol relapse is essential and entails a multidisciplinary effort between medicine and psychiatry, both in and out of the hospital. Because the relapsing, ill ALD patient most often will be admitted to a medical specialist, AUD might not receive enough attention during the medical admission. Psychiatrists can help in initiating AUD treatment in the acute medical setting, which has been shown to improve the outpatient course.6 For medically stable ALD patients admitted for inpatient psychiatric care or presenting a clinic, the mental health clinician should be aware of key laboratory and physical exam findings.

Bottom Line

Patients with alcoholic liver disease (ALD) require collaborative care from specialists in addiction, gastroenterology, and psychiatry. Psychiatrists have a role in identifying signs of ALD, prescribing medication to treat alcohol use disorder, and encouraging abstinence. There is some evidence supporting specific medications for varying severity of disease and different phases of recovery. Pharmacotherapy decisions should be made case by case.

Related Resources

• Khan A, Tansel A, White DL, et al. Efficacy of psychosocial interventions in inducing and maintaining alcohol abstinence in patients with chronic liver disease: a systematic review [published online August 6, 2015]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.07.047.

• Vuittonet CL, Halse M, Leggio L, et al. Pharmacotherapy for alcoholic patients with alcoholic liver disease. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71(15):1265-1276.

Drug Brand Names

Acamprosate • Campral

Baclofen • Lioresal

Disulfiram • Antabuse

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Naltrexone • ReVia, Vivitrol

Pentoxifylline • Trental

Prednisolone • Prelone

Rifaximin • Xifaxan

Topiramate • Topamax

Disclosures

Dr. Winder and Dr. Mellinger report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products. Dr. Fontana receives research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb, Gilead, and Janssen and consults for the Chronic Liver Disease Foundation.

1. Gache P, Hadengue A. Baclofen improves abstinence in alcoholic cirrhosis: still better to come? J Hepatol. 2008;49(6):1083-1085.

2. Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, et al. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373(9682):2223-2233.

3. Singal AK, Kamath PS, Gores GJ, et al. Alcoholic hepatitis: current challenges and future directions. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(4):555-564; quiz e31-32.

4. Becker U, Deis A, Sørensen TI, et al. Prediction of risk of liver disease by alcohol intake, sex, and age: a prospective population study. Hepatology. 1996;23(5):1025-1029.

5. Mathurin P, Lucey MR. Management of alcoholic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2012;56(suppl 1):S39-S45.

6. Mann K, Lemenager T, Hoffmann S, et al; PREDICT Study Team. Results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled pharmacotherapy trial in alcoholism conducted in Germany and comparison with the US COMBINE study. Addict Biol. 2013;18(6):937-946.

7. Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, et al; COMBINE Study Research Group. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(17):2003-2017.

8. Kranzler HR, Rosenthal RN. Dual diagnosis: alcoholism and co-morbid psychiatric disorders. Am J Addict. 2003;12(suppl 1):S26-S40.

9. Book SW, Myrick H. Novel anticonvulsants in the treatment of alcoholism. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2005;14(4):371-376.

10. Furieri FA, Nakamura-Palacios EM. Gabapentin reduces alcohol consumption and craving: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(11):1691-1700.

11. Blodgett JC, Del Re AC, Maisel NC, et al. A meta-analysis of topiramate’s effects for individuals with alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38(6):1481-1488.

12. Krystal JH, Cramer JA, Krol WF, et al; Veterans Affairs Naltrexone Cooperative Study 425 Group. Naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(24):1734-1739.

13. Petrakis IL, Poling J, Levinson C, et al; VA New England VISN I MIRECC Study Group. Naltrexone and disulfiram in patients with alcohol dependence and comorbid psychiatric disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57(10):1128-1137.

14. Maisel NC, Blodgett JC, Wilbourne PL, et al. Meta-analysis of naltrexone and acamprosate for treating alcohol use disorders: when are these medications most helpful? Addiction. 2013;108(2):275-293.

15. Pettinati HM, O’Brien CP, Rabinowitz AR, et al. The status of naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence: specific effects on heavy drinking. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;26(6):610-625.

16. Anton RF, Myrick H, Wright TM, et al. Gabapentin combined with naltrexone for the treatment of alcohol dependence. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(7):709-717.

17. Srisurapanont M, Jarusuraisin N. Opioid antagonists for alcohol dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005(1):CD001867.

18. Naltrexone. 2014. http://www.micromedexsolutions.com. Accessed January 31, 2015.

19. Soyka M, Chick J. Use of acamprosate and opioid antagonists in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a European perspective. Am J Addict. 2003;12(suppl 1):S69-S80.

20. Turncliff RZ, Dunbar JL, Dong Q, et al. Pharmacokinetics of long-acting naltrexone in subjects with mild to moderate hepatic impairment. J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;45(11):1259-1267.

21. United States National Library of Medicine. Naltrexone. http://livertox.nlm.nih.gov/Naltrexone.htm. Updated September 30, 2015. Accessed November 10, 2015.

22. Terg R, Coronel E, Sordá J, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral naltrexone treatment for pruritus of cholestasis, a crossover, double blind, placebo-controlled study. J Hepatol. 2002;37(6):717-722.

23. Skinner MD, Lahmek P, Pham H, et al. Disulfiram efficacy in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a meta-analysis [published online February 10, 2014]. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e87366. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087366.

24. Disulfiram. 2014. http://www.micromedexsolutions.com. Accessed January 31, 2015.

25. Björnsson E, Nordlinder H, Olsson R. Clinical characteristics and prognostic markers in disulfiram-induced liver injury. J Hepatol. 2006;44(4):791-797.

26. Chick J. Safety issues concerning the use of disulfiram in treating alcohol dependence. Drug Saf. 1999;20(5):427-435.

27. Campral [package insert]. St. Louis, MO: Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2012.

28. Brower KJ, Myra Kim H, Strobbe S, et al. A randomized double-blind pilot trial of gabapentin versus placebo to treat alcohol dependence and comorbid insomnia. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(8):1429-1438.

29. Mason BJ, Quello S, Goodell V, et al. Gabapentin treatment for alcohol dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(1):70-77.

30. Neurontin [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer; 2015.

31. Johnson BA, Ait-Daoud N, Akhtar FZ, et al. Oral topiramate reduces the consequences of drinking and improves the quality of life of alcohol-dependent individuals: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(9):905-912.

32. Paparrigopoulos T, Tzavellas E, Karaiskos D, et al. Treatment of alcohol dependence with low-dose topiramate: an open-label controlled study. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:41.

33. Rubio G, Ponce G, Jiménez-Arriero MA, et al. Effects of topiramate in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2004;37(1):37-40.

34. Topamax [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals; 2009.

35. De Sousa AA, De Sousa J, Kapoor H. An open randomized trial comparing disulfiram and topiramate in the treatment of alcohol dependence. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;34(4):460-463.

36. Kampman KM, Pettinati HM, Lynch KG, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of topiramate for the treatment of comorbid cocaine and alcohol dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133(1):94-99.

37. Addolorato G, Leggio L, Ferrulli A, et al. Dose-response effect of baclofen in reducing daily alcohol intake in alcohol dependence: secondary analysis of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Alcohol Alcohol. 2011;46(3):312-317.

38. Balcofen [package insert]. Concord, NC: McKesson Packing Services; 2013.

39. United States National Library of Medicine. Baclofen. 2015. http://livertox.nlm.nih.gov/Baclofen.htm. Accessed November 7, 2015.

40. Addolorato G, Leggio L, Ferrulli A, et al. Effectiveness and safety of baclofen for maintenance of alcohol abstinence in alcohol-dependent patients with liver cirrhosis: randomised, double-blind controlled study. Lancet. 2007;370(9603):1915-1922.

41. Leggio L, Ferrulli A, Zambon A, et al. Baclofen promotes alcohol abstinence in alcohol dependent cirrhotic patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Addict Behav. 2012;37(4):561-564.

42. Franchitto N, Pelissier F, Lauque D, et al. Self-intoxication with baclofen in alcohol-dependent patients with co-existing psychiatric illness: an emergency department case series. Alcohol Alcohol. 2014;49(1):79-83.

43. Brennan JL, Leung JG, Gagliardi JP, et al. Clinical effectiveness of baclofen for the treatment of alcohol dependence: a review. Clin Pharmacol. 2013;5:99-107.

44. Rösner S, Leucht S, Lehert P, et al. Acamprosate supports abstinence, naltrexone prevents excessive drinking: evidence from a meta-analysis with unreported outcomes. J Psychopharmacol. 2008;22(1):11-23.

45. Marlatt GA, Witkiewitz K. Harm reduction approaches to alcohol use: health promotion, prevention, and treatment. Addict Behav. 2002;27(6):867-886.

46. O’Shea RS, Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ. Alcoholic liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(1):14-32; quiz 33.

1. Gache P, Hadengue A. Baclofen improves abstinence in alcoholic cirrhosis: still better to come? J Hepatol. 2008;49(6):1083-1085.

2. Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, et al. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373(9682):2223-2233.

3. Singal AK, Kamath PS, Gores GJ, et al. Alcoholic hepatitis: current challenges and future directions. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(4):555-564; quiz e31-32.

4. Becker U, Deis A, Sørensen TI, et al. Prediction of risk of liver disease by alcohol intake, sex, and age: a prospective population study. Hepatology. 1996;23(5):1025-1029.

5. Mathurin P, Lucey MR. Management of alcoholic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2012;56(suppl 1):S39-S45.

6. Mann K, Lemenager T, Hoffmann S, et al; PREDICT Study Team. Results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled pharmacotherapy trial in alcoholism conducted in Germany and comparison with the US COMBINE study. Addict Biol. 2013;18(6):937-946.

7. Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, et al; COMBINE Study Research Group. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(17):2003-2017.

8. Kranzler HR, Rosenthal RN. Dual diagnosis: alcoholism and co-morbid psychiatric disorders. Am J Addict. 2003;12(suppl 1):S26-S40.

9. Book SW, Myrick H. Novel anticonvulsants in the treatment of alcoholism. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2005;14(4):371-376.

10. Furieri FA, Nakamura-Palacios EM. Gabapentin reduces alcohol consumption and craving: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(11):1691-1700.

11. Blodgett JC, Del Re AC, Maisel NC, et al. A meta-analysis of topiramate’s effects for individuals with alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38(6):1481-1488.

12. Krystal JH, Cramer JA, Krol WF, et al; Veterans Affairs Naltrexone Cooperative Study 425 Group. Naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(24):1734-1739.

13. Petrakis IL, Poling J, Levinson C, et al; VA New England VISN I MIRECC Study Group. Naltrexone and disulfiram in patients with alcohol dependence and comorbid psychiatric disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57(10):1128-1137.

14. Maisel NC, Blodgett JC, Wilbourne PL, et al. Meta-analysis of naltrexone and acamprosate for treating alcohol use disorders: when are these medications most helpful? Addiction. 2013;108(2):275-293.

15. Pettinati HM, O’Brien CP, Rabinowitz AR, et al. The status of naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence: specific effects on heavy drinking. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;26(6):610-625.

16. Anton RF, Myrick H, Wright TM, et al. Gabapentin combined with naltrexone for the treatment of alcohol dependence. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(7):709-717.

17. Srisurapanont M, Jarusuraisin N. Opioid antagonists for alcohol dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005(1):CD001867.

18. Naltrexone. 2014. http://www.micromedexsolutions.com. Accessed January 31, 2015.

19. Soyka M, Chick J. Use of acamprosate and opioid antagonists in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a European perspective. Am J Addict. 2003;12(suppl 1):S69-S80.

20. Turncliff RZ, Dunbar JL, Dong Q, et al. Pharmacokinetics of long-acting naltrexone in subjects with mild to moderate hepatic impairment. J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;45(11):1259-1267.

21. United States National Library of Medicine. Naltrexone. http://livertox.nlm.nih.gov/Naltrexone.htm. Updated September 30, 2015. Accessed November 10, 2015.

22. Terg R, Coronel E, Sordá J, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral naltrexone treatment for pruritus of cholestasis, a crossover, double blind, placebo-controlled study. J Hepatol. 2002;37(6):717-722.

23. Skinner MD, Lahmek P, Pham H, et al. Disulfiram efficacy in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a meta-analysis [published online February 10, 2014]. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e87366. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087366.

24. Disulfiram. 2014. http://www.micromedexsolutions.com. Accessed January 31, 2015.

25. Björnsson E, Nordlinder H, Olsson R. Clinical characteristics and prognostic markers in disulfiram-induced liver injury. J Hepatol. 2006;44(4):791-797.

26. Chick J. Safety issues concerning the use of disulfiram in treating alcohol dependence. Drug Saf. 1999;20(5):427-435.

27. Campral [package insert]. St. Louis, MO: Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2012.

28. Brower KJ, Myra Kim H, Strobbe S, et al. A randomized double-blind pilot trial of gabapentin versus placebo to treat alcohol dependence and comorbid insomnia. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(8):1429-1438.

29. Mason BJ, Quello S, Goodell V, et al. Gabapentin treatment for alcohol dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(1):70-77.

30. Neurontin [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer; 2015.

31. Johnson BA, Ait-Daoud N, Akhtar FZ, et al. Oral topiramate reduces the consequences of drinking and improves the quality of life of alcohol-dependent individuals: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(9):905-912.

32. Paparrigopoulos T, Tzavellas E, Karaiskos D, et al. Treatment of alcohol dependence with low-dose topiramate: an open-label controlled study. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:41.

33. Rubio G, Ponce G, Jiménez-Arriero MA, et al. Effects of topiramate in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2004;37(1):37-40.

34. Topamax [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals; 2009.

35. De Sousa AA, De Sousa J, Kapoor H. An open randomized trial comparing disulfiram and topiramate in the treatment of alcohol dependence. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;34(4):460-463.

36. Kampman KM, Pettinati HM, Lynch KG, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of topiramate for the treatment of comorbid cocaine and alcohol dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133(1):94-99.

37. Addolorato G, Leggio L, Ferrulli A, et al. Dose-response effect of baclofen in reducing daily alcohol intake in alcohol dependence: secondary analysis of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Alcohol Alcohol. 2011;46(3):312-317.

38. Balcofen [package insert]. Concord, NC: McKesson Packing Services; 2013.

39. United States National Library of Medicine. Baclofen. 2015. http://livertox.nlm.nih.gov/Baclofen.htm. Accessed November 7, 2015.

40. Addolorato G, Leggio L, Ferrulli A, et al. Effectiveness and safety of baclofen for maintenance of alcohol abstinence in alcohol-dependent patients with liver cirrhosis: randomised, double-blind controlled study. Lancet. 2007;370(9603):1915-1922.

41. Leggio L, Ferrulli A, Zambon A, et al. Baclofen promotes alcohol abstinence in alcohol dependent cirrhotic patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Addict Behav. 2012;37(4):561-564.

42. Franchitto N, Pelissier F, Lauque D, et al. Self-intoxication with baclofen in alcohol-dependent patients with co-existing psychiatric illness: an emergency department case series. Alcohol Alcohol. 2014;49(1):79-83.

43. Brennan JL, Leung JG, Gagliardi JP, et al. Clinical effectiveness of baclofen for the treatment of alcohol dependence: a review. Clin Pharmacol. 2013;5:99-107.

44. Rösner S, Leucht S, Lehert P, et al. Acamprosate supports abstinence, naltrexone prevents excessive drinking: evidence from a meta-analysis with unreported outcomes. J Psychopharmacol. 2008;22(1):11-23.

45. Marlatt GA, Witkiewitz K. Harm reduction approaches to alcohol use: health promotion, prevention, and treatment. Addict Behav. 2002;27(6):867-886.

46. O’Shea RS, Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ. Alcoholic liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(1):14-32; quiz 33.