User login

Should physicians with OUDs return to practice after treatment?

New review points to importance of sustained recovery

A new article in the Journal of the Neurological Sciences provides an impressive review of research on the complex impairments produced by a wide range of drugs of abuse with a close look at physicians and other health care professionals.1

This review breaks new ground in outlining fitness for duty as an important outcome of the state physician health programs (PHPs). In addition, the review and case report by Alexandria G. Polles, MD, and colleagues are a response to the growing call for the state PHP system of care management to explicitly endorse the use of medication-assisted treatment, specifically the use of buprenorphine and methadone, in the treatment of physicians diagnosed with opioid use disorder (OUD). , because of the elevated rate of substance use disorders among physicians and the safety-sensitive nature of the practice of medicine.

Medication-assisted treatment (MAT)2 for opioid use disorders now dominates the field of treatment in terms of prescribing and also funding to address the opioid overdose crisis. MAT generally includes naltrexone and injectable naltrexone, though those antagonist medications have been used successfully for many decades by PHPs.3 However, to understand the controversy over the use of MAT in the care management of physicians first requires an understanding of state PHPs and how those programs oversee the care of physicians diagnosed with substance use disorders (SUDs), including OUDs.

A national blueprint study of PHPs showed that care begins with a formal diagnostic evaluation.4 Only when a diagnosis of an SUD is established is a physician referred to the attention of a state PHP, and a monitoring contract is signed. PHPs typically do not offer any direct treatment; instead, they manage the care of physician participants in programs in which the PHPs have confidence. Formal addiction treatment most often is 30 days of residential treatment, but many physicians receive intensive outpatient treatment.

After completing an episode of formal treatment, physicians are closely monitored, usually for 5 years, through random drug and alcohol tests, and work site monitors. They are required to engage in intensive recovery support, typically 12-step fellowships but also other alternative recovery support programs. Comorbid conditions, including mental health disorders, are also treated. Managing PHPs have no sanctions for noncompliance; however, importantly, they do offer a safe haven from state medical licensing boards for physicians who are compliant with their recommendations and who remain abstinent from any use of alcohol, marijuana, illicit drugs, or other nonmedical drug use.

The national blueprint study included 16 state PHPs and reviewed single episodes of PHP care for 908 physicians. Complete abstinence from any use of alcohol, marijuana, or other drugs was required of all physicians for monitoring periods of at least 5 years. During the extended period, 78% of the physicians did not have a single positive or missed test. Two-thirds of physicians who had one positive or missed test did not have a second. About a dozen publications have resulted from this national study, including an analysis of the roughly one-third of the physicians who were diagnosed with OUD.5

A sample of 702 PHP participants was grouped based on primary drug at intake: alcohol only, any opioid with or without alcohol, and nonopioid drugs. No significant differences were found among these groups in the percentage who completed PHP contracts, failed to complete their contract, or extended their contract and continued to be monitored. Only one physician received methadone to treat chronic pain. None received opioid agonists to treat their opioid use disorder. Opioid antagonist medication (naltrexone) was used for 40 physicians, or 5.7% of the total sample: 2 physicians (1%) from the alcohol-only group; 35 physicians (10.3%) from the any opioid group, and 3 physicians (1.9%) from nonopioid group.

The second fact that needs to be understood is that medical practice in relationship to SUDs is treated by state licensing boards as a safety-sensitive job, analogous to commercial airline pilots who have the Human Intervention Motivation Study (HIMS),6 which is their own care management program analogous to that of PHPs. A similar program exists for attorneys known as Commission on Lawyer Assistance Programs (CoLAP).7 Fitness for duty and prevention of harm are major concerns in occupations such as those of physicians, commercial truck drivers, and people working in the nuclear power industry, all of whom have similar safety protections requiring no drug use.

A third fact that deserves special attention is that the unique system of care management for physicians began in the early 1970s. It grew out of employee assistance programs, led then and often now by physicians who are themselves in recovery from SUDs. Many of the successful addiction treatment tools used today come from extensive research of their use in PHPs. Contingency management, 12 steps, caduceus recovery, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and treatment outcomes defined in years are examples in which PHP research helped change treatment and long-term management of SUDs in non-PHP populations.

Dr. Polles and colleagues provide an impressive and comprehensive summary of the issues involved in the new interest in providing the physicians with OUD under PHP care management the option of using buprenorphine or methadone. Such a model within an abstinence-based framework is now being pioneered by a variety of programs, from COAT8 at West Virginia University, Morgantown, to the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation.9 In those programs, patients with OUD are offered the option of using buprenorphine, methadone, or naltrexone as well as the option of using none of those medications in an extended abstinence-based intensive treatment. The authors impressively and fairly summarize the evidence on whether there are cognitive or behavioral deficits associated with the therapeutic use of either buprenorphine or methadone, which might make them unacceptable for physicians. The strongest evidence that these medicines are not necessary in the treatment of OUDs in PHPs is the outstanding outcomes PHPs produce without use of these two medications. If skeptical of the use of medications for OUD treatment in PHP care management, Dr. Polles and colleagues are open to experiments to test the effects of this option just as Florida PHP programs pioneered contracts that included mandatory naltrexone.10 West Virginia University, the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation, and other programs should be tested to evaluate just how safe, effective, and attractive such an option would be to physicians.

Many, if not most, SUD treatment programs that use MAT are not associated with the intensive psychological treatment or extended participation in recovery support, such as the 12-step fellowships. MAT is viewed as a harm reduction strategy rather than conceptualized as an abstinence-oriented treatment. For example, there is seldom a “sobriety date” among individuals in MAT, i.e., the last day the individual used any substance of abuse, including alcohol and marijuana. These are, however, central features of PHP care, and they are features of the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation’s definition of recovery11 and use of MAT.

Dr. Polles and colleagues call attention to the unique care management of the PHP for all SUDs, not just for OUDs, because the PHPs set the standard for returning physicians to work who have the fitness and cognitive skills to first do no harm. They emphasize the importance of making sustained recovery the expected outcome of SUD treatment. There is a robust literature on the ways in which this distinctive system of care management shows the path forward for addiction treatment generally to regularly achieve 5-year recovery.12 The current controversy over the potential use of buprenorphine and buprenorphine plus naloxone in PHPs is a useful entry into this far larger issue of the potential for PHPs to show the path forward for the addiction treatment field.

Dr. DuPont, the first director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), is president of the Institute for Behavior and Health Inc., a nonprofit drug-policy research organization in Rockville, Md. He has no disclosures. Dr. Gold is professor of psychiatry (adjunct) at Washington University in St. Louis. He is also the 17th Distinguished Alumni Professor at the University of Florida Gainesville. He has no disclosures.

References

1. Polles AG et al. J Neurol Sci. 2020 Jan 30;411:116714.

2. Oesterle TS et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019 Oct;94(10):2072-86.

3. Srivastava AB and Gold MS. Cerebrum. 2018 Sep-Oct; cer-13-8.

4. DuPont RL et al. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009 Mar 1;36(2):159-71.

5. Merlo LJ et al. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016 May 1;64:47-54.

6. Human Intervention Motivation Study (HIMS): An Occupational Substance Abuse Treatment Program.

7. Commission on Lawyer Assistance Programs (CoLAP).

8. Lander LR et al. J Neurol Sci. 2020;411:116712-8.

9. Klein AA et al. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019;104:51-63.

10. Merlo LJ et al. J Addict Med. 2012;5(4):279-83.

11. Betty Ford Consensus Panel. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007 Oct;33(3):221-8.

12. Carr GD et al. “Physician health programs: The U.S. model.” In KJ Brower and MB Riba, (eds.) Physician Mental Health and Well-Being (pp. 265-94). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2017.

New review points to importance of sustained recovery

New review points to importance of sustained recovery

A new article in the Journal of the Neurological Sciences provides an impressive review of research on the complex impairments produced by a wide range of drugs of abuse with a close look at physicians and other health care professionals.1

This review breaks new ground in outlining fitness for duty as an important outcome of the state physician health programs (PHPs). In addition, the review and case report by Alexandria G. Polles, MD, and colleagues are a response to the growing call for the state PHP system of care management to explicitly endorse the use of medication-assisted treatment, specifically the use of buprenorphine and methadone, in the treatment of physicians diagnosed with opioid use disorder (OUD). , because of the elevated rate of substance use disorders among physicians and the safety-sensitive nature of the practice of medicine.

Medication-assisted treatment (MAT)2 for opioid use disorders now dominates the field of treatment in terms of prescribing and also funding to address the opioid overdose crisis. MAT generally includes naltrexone and injectable naltrexone, though those antagonist medications have been used successfully for many decades by PHPs.3 However, to understand the controversy over the use of MAT in the care management of physicians first requires an understanding of state PHPs and how those programs oversee the care of physicians diagnosed with substance use disorders (SUDs), including OUDs.

A national blueprint study of PHPs showed that care begins with a formal diagnostic evaluation.4 Only when a diagnosis of an SUD is established is a physician referred to the attention of a state PHP, and a monitoring contract is signed. PHPs typically do not offer any direct treatment; instead, they manage the care of physician participants in programs in which the PHPs have confidence. Formal addiction treatment most often is 30 days of residential treatment, but many physicians receive intensive outpatient treatment.

After completing an episode of formal treatment, physicians are closely monitored, usually for 5 years, through random drug and alcohol tests, and work site monitors. They are required to engage in intensive recovery support, typically 12-step fellowships but also other alternative recovery support programs. Comorbid conditions, including mental health disorders, are also treated. Managing PHPs have no sanctions for noncompliance; however, importantly, they do offer a safe haven from state medical licensing boards for physicians who are compliant with their recommendations and who remain abstinent from any use of alcohol, marijuana, illicit drugs, or other nonmedical drug use.

The national blueprint study included 16 state PHPs and reviewed single episodes of PHP care for 908 physicians. Complete abstinence from any use of alcohol, marijuana, or other drugs was required of all physicians for monitoring periods of at least 5 years. During the extended period, 78% of the physicians did not have a single positive or missed test. Two-thirds of physicians who had one positive or missed test did not have a second. About a dozen publications have resulted from this national study, including an analysis of the roughly one-third of the physicians who were diagnosed with OUD.5

A sample of 702 PHP participants was grouped based on primary drug at intake: alcohol only, any opioid with or without alcohol, and nonopioid drugs. No significant differences were found among these groups in the percentage who completed PHP contracts, failed to complete their contract, or extended their contract and continued to be monitored. Only one physician received methadone to treat chronic pain. None received opioid agonists to treat their opioid use disorder. Opioid antagonist medication (naltrexone) was used for 40 physicians, or 5.7% of the total sample: 2 physicians (1%) from the alcohol-only group; 35 physicians (10.3%) from the any opioid group, and 3 physicians (1.9%) from nonopioid group.

The second fact that needs to be understood is that medical practice in relationship to SUDs is treated by state licensing boards as a safety-sensitive job, analogous to commercial airline pilots who have the Human Intervention Motivation Study (HIMS),6 which is their own care management program analogous to that of PHPs. A similar program exists for attorneys known as Commission on Lawyer Assistance Programs (CoLAP).7 Fitness for duty and prevention of harm are major concerns in occupations such as those of physicians, commercial truck drivers, and people working in the nuclear power industry, all of whom have similar safety protections requiring no drug use.

A third fact that deserves special attention is that the unique system of care management for physicians began in the early 1970s. It grew out of employee assistance programs, led then and often now by physicians who are themselves in recovery from SUDs. Many of the successful addiction treatment tools used today come from extensive research of their use in PHPs. Contingency management, 12 steps, caduceus recovery, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and treatment outcomes defined in years are examples in which PHP research helped change treatment and long-term management of SUDs in non-PHP populations.

Dr. Polles and colleagues provide an impressive and comprehensive summary of the issues involved in the new interest in providing the physicians with OUD under PHP care management the option of using buprenorphine or methadone. Such a model within an abstinence-based framework is now being pioneered by a variety of programs, from COAT8 at West Virginia University, Morgantown, to the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation.9 In those programs, patients with OUD are offered the option of using buprenorphine, methadone, or naltrexone as well as the option of using none of those medications in an extended abstinence-based intensive treatment. The authors impressively and fairly summarize the evidence on whether there are cognitive or behavioral deficits associated with the therapeutic use of either buprenorphine or methadone, which might make them unacceptable for physicians. The strongest evidence that these medicines are not necessary in the treatment of OUDs in PHPs is the outstanding outcomes PHPs produce without use of these two medications. If skeptical of the use of medications for OUD treatment in PHP care management, Dr. Polles and colleagues are open to experiments to test the effects of this option just as Florida PHP programs pioneered contracts that included mandatory naltrexone.10 West Virginia University, the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation, and other programs should be tested to evaluate just how safe, effective, and attractive such an option would be to physicians.

Many, if not most, SUD treatment programs that use MAT are not associated with the intensive psychological treatment or extended participation in recovery support, such as the 12-step fellowships. MAT is viewed as a harm reduction strategy rather than conceptualized as an abstinence-oriented treatment. For example, there is seldom a “sobriety date” among individuals in MAT, i.e., the last day the individual used any substance of abuse, including alcohol and marijuana. These are, however, central features of PHP care, and they are features of the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation’s definition of recovery11 and use of MAT.

Dr. Polles and colleagues call attention to the unique care management of the PHP for all SUDs, not just for OUDs, because the PHPs set the standard for returning physicians to work who have the fitness and cognitive skills to first do no harm. They emphasize the importance of making sustained recovery the expected outcome of SUD treatment. There is a robust literature on the ways in which this distinctive system of care management shows the path forward for addiction treatment generally to regularly achieve 5-year recovery.12 The current controversy over the potential use of buprenorphine and buprenorphine plus naloxone in PHPs is a useful entry into this far larger issue of the potential for PHPs to show the path forward for the addiction treatment field.

Dr. DuPont, the first director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), is president of the Institute for Behavior and Health Inc., a nonprofit drug-policy research organization in Rockville, Md. He has no disclosures. Dr. Gold is professor of psychiatry (adjunct) at Washington University in St. Louis. He is also the 17th Distinguished Alumni Professor at the University of Florida Gainesville. He has no disclosures.

References

1. Polles AG et al. J Neurol Sci. 2020 Jan 30;411:116714.

2. Oesterle TS et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019 Oct;94(10):2072-86.

3. Srivastava AB and Gold MS. Cerebrum. 2018 Sep-Oct; cer-13-8.

4. DuPont RL et al. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009 Mar 1;36(2):159-71.

5. Merlo LJ et al. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016 May 1;64:47-54.

6. Human Intervention Motivation Study (HIMS): An Occupational Substance Abuse Treatment Program.

7. Commission on Lawyer Assistance Programs (CoLAP).

8. Lander LR et al. J Neurol Sci. 2020;411:116712-8.

9. Klein AA et al. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019;104:51-63.

10. Merlo LJ et al. J Addict Med. 2012;5(4):279-83.

11. Betty Ford Consensus Panel. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007 Oct;33(3):221-8.

12. Carr GD et al. “Physician health programs: The U.S. model.” In KJ Brower and MB Riba, (eds.) Physician Mental Health and Well-Being (pp. 265-94). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2017.

A new article in the Journal of the Neurological Sciences provides an impressive review of research on the complex impairments produced by a wide range of drugs of abuse with a close look at physicians and other health care professionals.1

This review breaks new ground in outlining fitness for duty as an important outcome of the state physician health programs (PHPs). In addition, the review and case report by Alexandria G. Polles, MD, and colleagues are a response to the growing call for the state PHP system of care management to explicitly endorse the use of medication-assisted treatment, specifically the use of buprenorphine and methadone, in the treatment of physicians diagnosed with opioid use disorder (OUD). , because of the elevated rate of substance use disorders among physicians and the safety-sensitive nature of the practice of medicine.

Medication-assisted treatment (MAT)2 for opioid use disorders now dominates the field of treatment in terms of prescribing and also funding to address the opioid overdose crisis. MAT generally includes naltrexone and injectable naltrexone, though those antagonist medications have been used successfully for many decades by PHPs.3 However, to understand the controversy over the use of MAT in the care management of physicians first requires an understanding of state PHPs and how those programs oversee the care of physicians diagnosed with substance use disorders (SUDs), including OUDs.

A national blueprint study of PHPs showed that care begins with a formal diagnostic evaluation.4 Only when a diagnosis of an SUD is established is a physician referred to the attention of a state PHP, and a monitoring contract is signed. PHPs typically do not offer any direct treatment; instead, they manage the care of physician participants in programs in which the PHPs have confidence. Formal addiction treatment most often is 30 days of residential treatment, but many physicians receive intensive outpatient treatment.

After completing an episode of formal treatment, physicians are closely monitored, usually for 5 years, through random drug and alcohol tests, and work site monitors. They are required to engage in intensive recovery support, typically 12-step fellowships but also other alternative recovery support programs. Comorbid conditions, including mental health disorders, are also treated. Managing PHPs have no sanctions for noncompliance; however, importantly, they do offer a safe haven from state medical licensing boards for physicians who are compliant with their recommendations and who remain abstinent from any use of alcohol, marijuana, illicit drugs, or other nonmedical drug use.

The national blueprint study included 16 state PHPs and reviewed single episodes of PHP care for 908 physicians. Complete abstinence from any use of alcohol, marijuana, or other drugs was required of all physicians for monitoring periods of at least 5 years. During the extended period, 78% of the physicians did not have a single positive or missed test. Two-thirds of physicians who had one positive or missed test did not have a second. About a dozen publications have resulted from this national study, including an analysis of the roughly one-third of the physicians who were diagnosed with OUD.5

A sample of 702 PHP participants was grouped based on primary drug at intake: alcohol only, any opioid with or without alcohol, and nonopioid drugs. No significant differences were found among these groups in the percentage who completed PHP contracts, failed to complete their contract, or extended their contract and continued to be monitored. Only one physician received methadone to treat chronic pain. None received opioid agonists to treat their opioid use disorder. Opioid antagonist medication (naltrexone) was used for 40 physicians, or 5.7% of the total sample: 2 physicians (1%) from the alcohol-only group; 35 physicians (10.3%) from the any opioid group, and 3 physicians (1.9%) from nonopioid group.

The second fact that needs to be understood is that medical practice in relationship to SUDs is treated by state licensing boards as a safety-sensitive job, analogous to commercial airline pilots who have the Human Intervention Motivation Study (HIMS),6 which is their own care management program analogous to that of PHPs. A similar program exists for attorneys known as Commission on Lawyer Assistance Programs (CoLAP).7 Fitness for duty and prevention of harm are major concerns in occupations such as those of physicians, commercial truck drivers, and people working in the nuclear power industry, all of whom have similar safety protections requiring no drug use.

A third fact that deserves special attention is that the unique system of care management for physicians began in the early 1970s. It grew out of employee assistance programs, led then and often now by physicians who are themselves in recovery from SUDs. Many of the successful addiction treatment tools used today come from extensive research of their use in PHPs. Contingency management, 12 steps, caduceus recovery, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and treatment outcomes defined in years are examples in which PHP research helped change treatment and long-term management of SUDs in non-PHP populations.

Dr. Polles and colleagues provide an impressive and comprehensive summary of the issues involved in the new interest in providing the physicians with OUD under PHP care management the option of using buprenorphine or methadone. Such a model within an abstinence-based framework is now being pioneered by a variety of programs, from COAT8 at West Virginia University, Morgantown, to the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation.9 In those programs, patients with OUD are offered the option of using buprenorphine, methadone, or naltrexone as well as the option of using none of those medications in an extended abstinence-based intensive treatment. The authors impressively and fairly summarize the evidence on whether there are cognitive or behavioral deficits associated with the therapeutic use of either buprenorphine or methadone, which might make them unacceptable for physicians. The strongest evidence that these medicines are not necessary in the treatment of OUDs in PHPs is the outstanding outcomes PHPs produce without use of these two medications. If skeptical of the use of medications for OUD treatment in PHP care management, Dr. Polles and colleagues are open to experiments to test the effects of this option just as Florida PHP programs pioneered contracts that included mandatory naltrexone.10 West Virginia University, the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation, and other programs should be tested to evaluate just how safe, effective, and attractive such an option would be to physicians.

Many, if not most, SUD treatment programs that use MAT are not associated with the intensive psychological treatment or extended participation in recovery support, such as the 12-step fellowships. MAT is viewed as a harm reduction strategy rather than conceptualized as an abstinence-oriented treatment. For example, there is seldom a “sobriety date” among individuals in MAT, i.e., the last day the individual used any substance of abuse, including alcohol and marijuana. These are, however, central features of PHP care, and they are features of the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation’s definition of recovery11 and use of MAT.

Dr. Polles and colleagues call attention to the unique care management of the PHP for all SUDs, not just for OUDs, because the PHPs set the standard for returning physicians to work who have the fitness and cognitive skills to first do no harm. They emphasize the importance of making sustained recovery the expected outcome of SUD treatment. There is a robust literature on the ways in which this distinctive system of care management shows the path forward for addiction treatment generally to regularly achieve 5-year recovery.12 The current controversy over the potential use of buprenorphine and buprenorphine plus naloxone in PHPs is a useful entry into this far larger issue of the potential for PHPs to show the path forward for the addiction treatment field.

Dr. DuPont, the first director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), is president of the Institute for Behavior and Health Inc., a nonprofit drug-policy research organization in Rockville, Md. He has no disclosures. Dr. Gold is professor of psychiatry (adjunct) at Washington University in St. Louis. He is also the 17th Distinguished Alumni Professor at the University of Florida Gainesville. He has no disclosures.

References

1. Polles AG et al. J Neurol Sci. 2020 Jan 30;411:116714.

2. Oesterle TS et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019 Oct;94(10):2072-86.

3. Srivastava AB and Gold MS. Cerebrum. 2018 Sep-Oct; cer-13-8.

4. DuPont RL et al. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009 Mar 1;36(2):159-71.

5. Merlo LJ et al. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016 May 1;64:47-54.

6. Human Intervention Motivation Study (HIMS): An Occupational Substance Abuse Treatment Program.

7. Commission on Lawyer Assistance Programs (CoLAP).

8. Lander LR et al. J Neurol Sci. 2020;411:116712-8.

9. Klein AA et al. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019;104:51-63.

10. Merlo LJ et al. J Addict Med. 2012;5(4):279-83.

11. Betty Ford Consensus Panel. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007 Oct;33(3):221-8.

12. Carr GD et al. “Physician health programs: The U.S. model.” In KJ Brower and MB Riba, (eds.) Physician Mental Health and Well-Being (pp. 265-94). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2017.

Beyond the opioids

The drug epidemic of early initiation, frequent use, and a polydrug reality

The national opioid epidemic is one of the most important public health challenges facing the United States today. This crisis has resulted in death, disability, and increased infectious and other comorbid diseases.

Public attention has been focused on the medical management of pain, patterns of opioid prescriptions, and use of heroin and fentanyl. But the opioid crisis is, in fact, part of a far larger drug epidemic. The foundation on which the opioid epidemic is built is recreational pharmacology – the widespread use of aggressively marketed chemicals that seductively superstimulate brain-reward producing alterations in consciousness and pleasure, often mislabeled “self-medication.”

Drugs of abuse are unique chemicals that stimulate their own taking by producing an intense reinforcement in the human brain, which tells users that they have done something monumentally good. Instead of preserving the species, this chemical stimulation of brain reward begins the process of retraining the brain and reward system to respond quickly to drugs of abuse and drug-promoting cues. Drugs of abuse do not come from one class or chemical structure, but, rather, from disparate chemical classes that have in common the stimulation of brain reward. This bad learning is accelerated to addiction when drugs of abuse are smoked, snorted, vaped, or injected, as these routes of administration produce rapidly rising and falling blood levels.

Thanks to the science of animal models, we understand drug self-administration and abstinence. However, in animals, we cannot approximate addiction beyond the mechanical because of the cultural complexity of human behavior. Most animal models are good at predicting what treatments will work for drug addiction in animals. They are less predictive when it comes to humans. Animal models are good for understanding withdrawal reversal and identifying self-administration reductions and even changes in place preference. Animal models have consistently shown that drugs of abuse raise the brain’s reward threshold and cause epigenetic changes, and that many of these changes are persistent, if not permanent. In animal models, clonidine or opioid detoxification followed by naltrexone is a cure for opioid use disorder. Again, in animal models, this protocol is tied to no relapses – just a cure. We know that this is not the case for humans suffering from opioid addiction, where relapses define the disorder.

A closer look at opioid overdoses

Opioid overdose deaths are skyrocketing in the United States. The number of deaths tied to opioid overdoses quadrupled between 1999 and 2015 (in this 15-year period, that is more than 500,000 deaths). Then, between 2015 and 2016, they further increased dramatically to more than 60,000 and in 2017 topped 72,000. This increase was driven partly by a sevenfold increase in overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids (excluding methadone): from 3,105 in 2013 to about 20,000 in 2016.

Illicitly manufactured fentanyl, a synthetic opioid 50-100 times more potent than morphine, is primarily responsible for this rapid increase. In addition, fentanyl analogs such as acetyl fentanyl, furanyl fentanyl, and carfentanil are being detected increasingly in overdose deaths and the illicit opioid drug supply. Drug overdose is the leading cause of accidental death in the United States, with opioids implicated in more than half of these deaths. Moreover, drug overdose is now the leading cause of death of all Americans under age 50. As if these data were not bad enough, recent analyses suggest that the number of opioid overdose deaths might be significantly undercounted. Without intervention, we would expect 235,000 opioid-related deaths (85,000 from prescription opioids and 150,000 from heroin) from 2016 to 2020; and 510,000 opioid-related deaths (170,000 from prescription opioids and 340,000 from heroin) from 2016 to 2025.1 In these opioid overdose deaths, rarely is the opioid the only drug present. Data from the Florida Drug-Related Outcomes Surveillance & Tracking System show that, in that state, more than 90% of opioid overdose deaths in 2016 showed other drugs of abuse present at death, an average of 2 to 4 – but as many as 11.2

It is well-accepted that medicine – in particular the overprescribing of opioids for pain and downplaying the risks of prescription opioid use – has played a fundamental role in the exponential rise in addiction and overdose death. The prescribing of other controlled substances, especially stimulants and benzodiazepines, also is a factor in overdose deaths.

To say that the country has an opioid problem would be a simplistic understatement. Drug sellers are innovative, consistently adding new chemicals to the menu of available drugs. The user market keeps adding potential customers who already have trained their brains and dopamine systems to respond vigorously to drug-promoting cues and drugs. We are a nation of polydrug users without drug or brand loyalty, engaging in “recreational pharmacology.” Framing the national drug problem around opioids misses the bigger target. The future of the national drug problem is more drugs used by more drug users – not simply prescription misuse or even opioids but instead globally produced illegal synthetic drugs as is now common in Hong Kong and Southeast Asia. A focus exclusively on opioid use disorders might yield great progress in new treatment developments that are specific to opioids. But few people addicted to opioids do not also use many other drugs in other drug classes. The opioid treatments (for example, buprenorphine, methadone, naltrexone) are irrelevant to these other addictive and problem-generating drugs.

Finally, as a very recent report found, the national opioid epidemic has had profound second- and third-hand effects on those with opioid use disorders, their families, and communities, costing about $80 billion yearly in lost productivity, treatment (including emergency, medical, psychiatric, and addiction-specific care), and criminal justice involvement.1 Worse yet, missing from current discussion is the simple fact that drug users in the United States spend $100 billion on drugs each year. The entire annual cost of all treatment – both public and private – for alcohol and other substance use disorders is $34 billion a year. Drug users could pay for all of the treatment in the country with one-third of the money they now spend on drugs.

How much do drug users themselves spend on addiction treatment? Close to zero. The costs of both treatment and prevention are almost all carried by nondrug users. While many drug policy discussions call for “more treatment,” as important as that objective is, overlooked is the fact that 95% of people with substance use disorders do not think they have a drug problem and do not want treatment. What actions are needed now?

Control drug supply

Illicit drug supply used to be centrally controlled and reasonably well understood by law enforcement. Today, the illegal supply of addicting chemicals is global, innovative, massive, and decentralized. More drugs, including opioids, are now manufactured and delivered to users in higher potency, at lower prices, and with greater convenience than ever before. At the same time, illegal drug suppliers are moving away from agriculturally produced drugs such as marijuana, cocaine, and heroin to purely synthetic drugs such as synthetic cannabis, methamphetamine, and fentanyl. These synthetics do not require growing fields that are difficult to conceal, nor do they require farmers, or complex, clandestine, and vulnerable modes of transportation.

Instead, these new drugs can be synthesized in small and mobile laboratories located in any part of the globe and delivered anonymously, often by mail, to the users’ addresses. In addition, there remains ample illegal access to the older addicting agricultural chemicals and access to the many addicting legal chemicals that are widely used in the practice of medicine (for example, prescription drugs, including opioids). These abundant and varied sources make addicting drugs widely available to millions of Americans. Strong supply reduction efforts are needed. We must use the Drug Enforcement Administration to increase the cost of doing business in the illegal drug supply chain, and decrease access to drugs by bolstering interdiction and reducing precursor access. We can work to screen packages for drugs sent by U.S. mail or other express services.

It is gratifying to see so many of the missing pieces identified in the classic report3 published in 2012 by Columbia University in New York. Health care providers and professionals-in-training are being taught addiction medicine principles and practices. The Surgeon General has helped mobilize the public response to this crisis, and rightly suggested4 that everyone learn how to use and carry naloxone. Researchers are refocused on more than supply reduction.5 In addition, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) are working on delivery service improvements, developing nonopioid pain medications, and new treatments for addiction.

Increase access to naloxone

Increasing access to the opioid reversal medication is critical. Because of the surge in opioid overdose–related mortality, considerable resources have been devoted to emergency response and the widespread dissemination of the mu-opioid receptor antagonist naloxone.6

Naloxone should be readily available without prescription and at a price that makes access practical for emergency technicians and any concerned citizen. Administering naloxone should be analogous to CPR or cardioversion. They are similar, in that they are life-saving actions, but the target within the patient is the brain, rather than the heart. CPR education and cardioversion training efforts and access have been promoted well across the United States and can be done for naloxone.

Another comparison has been made between naloxone and giving an EpiPen to an allergic person in an anaphylaxis emergency or crisis. We need and want to rescue, resuscitate, and revive the overdosed patient and give the person another chance to make a change. We want to administer naloxone and get the patient evaluated and into long-term treatment. Now, rapid return to drug use is common after overdose reversal. We need to use overdose reversal as a path to treatment and see that it is sustained to long-term abstinence from drug use. The most recent report on the high cost of drug use correctly points out that none of the current treatment and policy proposals can reduce substantially the number of overdose deaths.1 Among 11 interventions analyzed by those researchers, making naloxone more available resulted in the greatest number of addiction deaths prevented.

Learn from physician health model of care

An assessment is needed of the 5-year recovery outcomes of all interventions for substance use disorder, including treatments that use and do not use medications, and harm-reduction interventions such as naloxone, needle exchange, and safe injection sites. A few years ago, researchers reported on a sample of 904 physicians consecutively admitted to 16 state Physician Health Programs (PHPs) that was monitored for 5 years or longer.7

This study characterized the outcomes of this episode of care and explored the elements of those programs that could improve the care routinely given to physicians but not to other addicted populations. PHPs were abstinence based and required physicians to abstain from any use of alcohol or other drugs of abuse as assessed by frequent random tests typically lasting for 5 years. Random tests rapidly identified any return to substance use, leading to swift and significant consequences.

Remarkably, 78% of participants had no positive test for either alcohol or drugs over the 5-year period of intensive monitoring. At posttreatment follow-up, 72% of the physicians were continuing to practice medicine. A key to the PHPs’ success is the 5 years of close monitoring with immediate consequences for any use and rapid, vigorous intervention upon any relapse to alcohol or drugs.

The unique PHP care management included close links to the 12-step fellowships of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), Narcotics Anonymous, and other intensive recovery support for the entire 5 years of care management. The PHPs used relatively brief residential and outpatient treatment programs. Given the remarkable long-term outcomes of the PHPs, this model of care management should inspire new approaches to integrated and sustained care management of addiction in health care generally. The 5-year recovery standard should be applied to all addiction treatments to judge their value.8

Re-energize prevention efforts

The country must integrate addiction care into all of health care in the model of other chronic disease management: from prevention to intervention, treatment, monitoring, and intervention for any relapse. For prevention, we must retarget the health goal for youth under age 21 of no use of alcohol, nicotine, marijuana, or other drugs. Substance use disorders, including opioid use disorders, can be traced to adolescent use of alcohol and other drugs. The younger the age of a person initiating the use of any addicting substance – and the more chronic that use – the greater the likelihood of subsequent substance use problems persisting, or reigniting, later in life.

This later addiction risk resulting from adolescent drug use is no surprise, given the unique vulnerability of the adolescent brain, a brain that is especially vulnerable to addicting chemicals and that is not fully developed until about age 25. Effective addiction prevention – for example, helping youth grow up drug free – can improve dramatically public health by reducing the lifetime prevalence of substance use disorders, including opioid addiction.

Youth prevention efforts today vary tremendously in message and scope. Often, prevention messages for youth are limited to specific drugs (for example, nonmedical use of prescription drugs or tobacco) to specific situations (e.g., drunk driving), or to specific amounts of drug use (for example, binge drinking) when all substance use among youth is linked and all drug use poses health risks during adolescence and beyond. Among youth aged 12-17, the use of any one of the three most widely used and available drugs – alcohol, nicotine, and marijuana – increases the likelihood of using the other two drugs, as well as other illicit drugs.9 Similarly, no use of alcohol, nicotine, or marijuana decreases the likelihood of using the others, or of using other illicit drugs.

A recent clinical report and policy statement issued by the American Academy of Pediatrics affirms that it is in the best interests of young patients to not use any substances.10 The screening recommendations issued by the AAP further encourage pediatricians and adolescent medicine physicians to help guide their patients to this fundamental and easily-understood health goal.

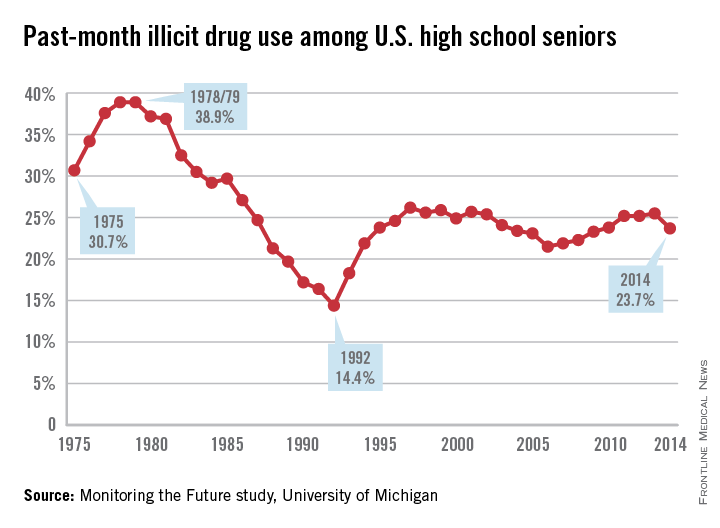

A new and better vision for addiction prevention must focus on the single, clear goal of no use of alcohol, nicotine, marijuana, or other drugs for health by youth under age 21.11 Some good news for prevention is that, for the past 3 decades, there has been a slow but steadily increasing percentage of American high school seniors reporting abstinence from any use of alcohol, cigarettes, marijuana, and other illicit drugs.12 In 2014, 25.5% of high school seniors reported lifetime abstinence, and fully 50% reported past-month abstinence from all substances. Those figures are dramatic, compared with abstinence rates during the nation’s peak years of youth drug use. In 1978, among high school seniors, 4.4% reported lifetime abstinence from any use of alcohol, cigarettes, marijuana, and other illicit drugs and 21% reported past-month abstinence. Notably, similar increasing rates of abstinence have been recorded among eighth- and 10th-graders. This encouraging and largely overlooked reality demonstrates that the no-use prevention goal for youth is both realistic and attainable.

Expand drug and alcohol courts

We need to rehabilitate the role of the criminal justice system in a public health–oriented policy to achieve two essential goals: 1) to improve supply reduction as described above, and 2) to reshape the criminal justice system as an engine of recovery as it is now for alcohol addiction.

The landmark report, “Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs and Health,” called for a continuum of health care extending from prevention to early identification and treatment of substance use disorders and long-term health care management with the goal of sustained recovery.13 A growing number of pioneering programs within the criminal justice system (for example, Hawaii’s HOPE Probation, South Dakota’s 24/7 Sobriety Project, and drug courts) are using innovative monitoring strategies for individuals with substance use problems, including providing substance use disorder treatment, with results showing reduced substance use, reduced recidivism, and reduced incarceration.14

In HOPE, drug-involved offenders are subject to frequent random drug testing, rather than the typical drug testing done on standard probation, only at the time of scheduled meetings with probation officers. Failure to abstain from drugs or failure to show up for random drug testing always results in a brief jail sanction, usually 2-15 days, depending on the nature and severity of the offense. Upon placement in HOPE at a warning hearing, probationers are encouraged to succeed, and are fully informed of the length of the jail sanctions that will be imposed for each type of violation. They are assured of the certainty and speed with which the sanctions will be applied.

Sanctions are applied consistently and impartially to ensure fairness for all. Substance abuse treatment is available to all offenders who want it and to those who demonstrate a need for treatment through “behavioral triage.” Offenders who test positive for drugs two or more times in short order with jail sanctions are referred for a substance abuse assessment and instructed to follow any recommended treatment. For this reason, offenders in HOPE succeed in treatment – because they are the offenders in most need and are supported by the leverage provided by the court to help them complete treatment.

A randomized, controlled trial compared offenders assigned to HOPE Probation and a control group assigned to probation as usual. Compared with offenders on probation as usual, at 1-year follow-up, HOPE offenders were:

• 55% less likely to be arrested for a new crime.

• 72% less likely to test positive for illegal drugs.

• 61% less likely to skip appointments with their supervisory officer.

• 53% less likely to have their probation revoked.

There also is a growing potential to harness the latent but enormous strength of the families who have confronted and are continuing to confront addiction in a family member. Families and those with addictions can be engaged in alcohol or drug courts, which can act like the PHP for addicted individuals in the criminal justice system.

Implications for treatment

The diversion of medications that are prescribed and intended for patients in pain is just one part of the far larger drug use and overdose problem. An addicted person with a hijacked brain is not the same as a nonaddicted pain patient. Taking medication as prescribed for pain can produce physical dependence, but importantly, this is not addiction. The person who is using drugs – whether or not prescribed – to produce euphoria is a different person from the person in that same body who is abstinent and not using. Talking with a person in active addiction often is frustrating and futile. That addicted user’s brain wants to use drugs.

The PHP system of care management demonstrates that individuals with substance use disorders can refrain from any substance use for extended periods of time with a carrot and stick approach; permitting a physician to earn a livelihood as a physician is the carrot. In medication-assisted treatment (MAT), the carrot is provided by agonist drugs and the comfort-fit they provide in the brain. They protect the patient from anxiety, and reduce stress and craving responsivity. The stick is an environment that is intolerant of continued nonmedical or addicting drug use. This can be the family, an employer, the criminal justice system, or others in a position to insist on abstinence.

PHP care management shows the way to improve all treatment outcomes; however, an even larger lesson can be learned from the millions of Americans now in recovery from addiction to opioids and other drugs. The “evidence” of what recovery is and how it is achieved and sustained is available to everyone who knows or comes into contact with people in recovery. How did that near-miraculous transformation happen? Even more importantly, how is it sustained when relapse is so common in addiction? The millions of Americans in recovery are the inspiration for a new generation of improved addiction treatment.

Addiction reprioritizes the brain toward continued drug use first, rather than family, friends, health, job, or another important remnant of the addicted person’s past having any meaningful standing. It is often a question like that raised by the AA axiom that it is easy to change a cucumber (naive or new drug user) into a pickle (an addict), but turning a pickle into a cucumber is very difficult. Risk-benefit research has shown that drugs change the ability to accurately assess risks and benefits by prioritizing drug use over virtually everything else, including the interests of the drug users themselves.

Along with judgment deficits comes dishonesty – a hallmark of addiction. The person with addictions lies, minimizes, and denies drug use, thus keeping the addictive run going. That often is the heart of addiction. The point is that once the disease is in control of the addicted brain, those around that hijacked brain must intervene – and the goal of cutting down drug use or limiting it to exclude one or another drug is not useful. Rather, it perpetuates the addiction. Freedom from addiction, that modern chemical slavery, requires no use of alcohol and other drugs, including marijuana, and a return to healthy relationships, sleep, eating, exercise, etc.

Recovery is more than abstinence from all drug use; it includes character development and citizenship. The data supporting the essential goal of recovery are found in the people who are in recovery not in today’s scientific research, which generally is off-target on recovery. Just because recovering people are anonymous does not mean that they do not exist. They prove that recovery happens all the time. They show what recovery is, and how it is achieved and maintained. Current arguments over which MAT is the best in a 3-month study is too short-term for a lifetime disorder and it ignores the concept of recovery despite the millions of people who are living it. Their stories are the bedrock of our message.

Our core evidence, our inspiration, comes from asking the people in recovery from the deadly, chronic disease of addiction three questions: 1) What was your life like when using drugs? 2) What happened to get you to stop using drugs? and 3) What is your life like when not using any drugs?” Every American who knows someone in recovery can do this research for themselves. We have been doing that research for decades.

People in recovery all have sobriety dates. Few in MAT have sobriety dates. Recovery from addiction is not just not taking Vicodin but living the life of a drug-free, recovering person. How do they hold onto recovery, and prevent and deal with relapses and slips? MAT is a major achievement in addiction treatment, including agonist maintenance with buprenorphine and methadone, but it needs to build in the goal of sustained recovery and strong recovery support. That means building into MAT the 12-step fellowships and related recovery support, as is done every day by James H. Berry, DO, of the Chestnut Ridge Center at West Virginia University’s Comprehensive Opioid Addiction Treatment, or COAT, program.15

MAT is good. It needs to be targeted on recovery, which can include continued use of the medicines now widely used: methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone. But recovery cannot include continued nonmedical drug use, and it also must include character development – with honesty replacing the dishonesty that is at the heart of addiction.

Holding up that widely available picture of recovery and making it clear to our readers is our goal in this article. For too many people, including some of our most treasured colleagues in addiction treatment, this message is new and radical. The PHP model has put it together in a program that is now more than 4 decades old. It is real, possible, and understandable. The key to its success is the commitment to living drug free, the active and sustained testing for any use of alcohol or other drugs linked to prompt intervention to any relapse, the use of recovery support, and the long duration of active care management: 5 years. That package is seldom seen in the current approach to addiction treatment, which often is siloed out of mainstream medicine – with little or no monitoring or support after the typically short duration of treatment.

People with addictions in recovery remain vulnerable to relapse for life, but the disease now is being managed successfully by millions of people. As dishonesty and self-centeredness were the heart of behaviors during active addiction, so honesty and caring for others are at the heart of life in recovery. This is an easily seen spiritual transformation that gives hope and guidance to addiction treatment, and inspiration to us in our work in treatment – and to all people with addictions.

Dr. Gold is the 17th Distinguished Alumni Professor at the University of Florida, Gainesville, professor of psychiatry (adjunct) at Washington University in St. Louis. Dr. DuPont is the first director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the second White House drug chief, founding president of the Institute for Behavior and Health in Rockville, Md., and author of “Chemical Slavery: Understanding Addiction and Stopping the Drug Epidemic” (Create Space Independent Publishing Platform), 2018.

References

1. Am J Public Health. 2018 Oct 108(10):1394-1400.

2. Florida Drug-Related Outcomes Surveillance & Tracking system (FROST)

3. Center on Addiction. Addiction Medicine: Closing the Gap Between Science and Practice. 2012 Jun.

4. Surgeon General’s Advisory on Naloxone and Opioid Overdose.

5. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018 Mar;93(3):269-72.

6. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2015 Feb;6(1):20-31.

7. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009 Mar;36(2):159-71.

8. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015 Nov;58:1-5.

9. Prev Med. 2018 Aug;113:68-73.

10. Pediatrics. 2016 Jun;138(1). doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1211.

11. Institute for Behavior and Health. (updated) 2018 Aug 29.

12. Pediatrics. 2018 Aug;142(2). doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3498.

13. Office of the Surgeon General. 2016.

14. The ASAM Principles of Addiction Medicine. (6th ed.) (in press) Wolters Kluwer, 2018.

15. West Virginia Clinical and Translational Science Institute. 2017 Aug 21.

The drug epidemic of early initiation, frequent use, and a polydrug reality

The drug epidemic of early initiation, frequent use, and a polydrug reality

The national opioid epidemic is one of the most important public health challenges facing the United States today. This crisis has resulted in death, disability, and increased infectious and other comorbid diseases.

Public attention has been focused on the medical management of pain, patterns of opioid prescriptions, and use of heroin and fentanyl. But the opioid crisis is, in fact, part of a far larger drug epidemic. The foundation on which the opioid epidemic is built is recreational pharmacology – the widespread use of aggressively marketed chemicals that seductively superstimulate brain-reward producing alterations in consciousness and pleasure, often mislabeled “self-medication.”

Drugs of abuse are unique chemicals that stimulate their own taking by producing an intense reinforcement in the human brain, which tells users that they have done something monumentally good. Instead of preserving the species, this chemical stimulation of brain reward begins the process of retraining the brain and reward system to respond quickly to drugs of abuse and drug-promoting cues. Drugs of abuse do not come from one class or chemical structure, but, rather, from disparate chemical classes that have in common the stimulation of brain reward. This bad learning is accelerated to addiction when drugs of abuse are smoked, snorted, vaped, or injected, as these routes of administration produce rapidly rising and falling blood levels.

Thanks to the science of animal models, we understand drug self-administration and abstinence. However, in animals, we cannot approximate addiction beyond the mechanical because of the cultural complexity of human behavior. Most animal models are good at predicting what treatments will work for drug addiction in animals. They are less predictive when it comes to humans. Animal models are good for understanding withdrawal reversal and identifying self-administration reductions and even changes in place preference. Animal models have consistently shown that drugs of abuse raise the brain’s reward threshold and cause epigenetic changes, and that many of these changes are persistent, if not permanent. In animal models, clonidine or opioid detoxification followed by naltrexone is a cure for opioid use disorder. Again, in animal models, this protocol is tied to no relapses – just a cure. We know that this is not the case for humans suffering from opioid addiction, where relapses define the disorder.

A closer look at opioid overdoses

Opioid overdose deaths are skyrocketing in the United States. The number of deaths tied to opioid overdoses quadrupled between 1999 and 2015 (in this 15-year period, that is more than 500,000 deaths). Then, between 2015 and 2016, they further increased dramatically to more than 60,000 and in 2017 topped 72,000. This increase was driven partly by a sevenfold increase in overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids (excluding methadone): from 3,105 in 2013 to about 20,000 in 2016.

Illicitly manufactured fentanyl, a synthetic opioid 50-100 times more potent than morphine, is primarily responsible for this rapid increase. In addition, fentanyl analogs such as acetyl fentanyl, furanyl fentanyl, and carfentanil are being detected increasingly in overdose deaths and the illicit opioid drug supply. Drug overdose is the leading cause of accidental death in the United States, with opioids implicated in more than half of these deaths. Moreover, drug overdose is now the leading cause of death of all Americans under age 50. As if these data were not bad enough, recent analyses suggest that the number of opioid overdose deaths might be significantly undercounted. Without intervention, we would expect 235,000 opioid-related deaths (85,000 from prescription opioids and 150,000 from heroin) from 2016 to 2020; and 510,000 opioid-related deaths (170,000 from prescription opioids and 340,000 from heroin) from 2016 to 2025.1 In these opioid overdose deaths, rarely is the opioid the only drug present. Data from the Florida Drug-Related Outcomes Surveillance & Tracking System show that, in that state, more than 90% of opioid overdose deaths in 2016 showed other drugs of abuse present at death, an average of 2 to 4 – but as many as 11.2

It is well-accepted that medicine – in particular the overprescribing of opioids for pain and downplaying the risks of prescription opioid use – has played a fundamental role in the exponential rise in addiction and overdose death. The prescribing of other controlled substances, especially stimulants and benzodiazepines, also is a factor in overdose deaths.

To say that the country has an opioid problem would be a simplistic understatement. Drug sellers are innovative, consistently adding new chemicals to the menu of available drugs. The user market keeps adding potential customers who already have trained their brains and dopamine systems to respond vigorously to drug-promoting cues and drugs. We are a nation of polydrug users without drug or brand loyalty, engaging in “recreational pharmacology.” Framing the national drug problem around opioids misses the bigger target. The future of the national drug problem is more drugs used by more drug users – not simply prescription misuse or even opioids but instead globally produced illegal synthetic drugs as is now common in Hong Kong and Southeast Asia. A focus exclusively on opioid use disorders might yield great progress in new treatment developments that are specific to opioids. But few people addicted to opioids do not also use many other drugs in other drug classes. The opioid treatments (for example, buprenorphine, methadone, naltrexone) are irrelevant to these other addictive and problem-generating drugs.

Finally, as a very recent report found, the national opioid epidemic has had profound second- and third-hand effects on those with opioid use disorders, their families, and communities, costing about $80 billion yearly in lost productivity, treatment (including emergency, medical, psychiatric, and addiction-specific care), and criminal justice involvement.1 Worse yet, missing from current discussion is the simple fact that drug users in the United States spend $100 billion on drugs each year. The entire annual cost of all treatment – both public and private – for alcohol and other substance use disorders is $34 billion a year. Drug users could pay for all of the treatment in the country with one-third of the money they now spend on drugs.

How much do drug users themselves spend on addiction treatment? Close to zero. The costs of both treatment and prevention are almost all carried by nondrug users. While many drug policy discussions call for “more treatment,” as important as that objective is, overlooked is the fact that 95% of people with substance use disorders do not think they have a drug problem and do not want treatment. What actions are needed now?

Control drug supply

Illicit drug supply used to be centrally controlled and reasonably well understood by law enforcement. Today, the illegal supply of addicting chemicals is global, innovative, massive, and decentralized. More drugs, including opioids, are now manufactured and delivered to users in higher potency, at lower prices, and with greater convenience than ever before. At the same time, illegal drug suppliers are moving away from agriculturally produced drugs such as marijuana, cocaine, and heroin to purely synthetic drugs such as synthetic cannabis, methamphetamine, and fentanyl. These synthetics do not require growing fields that are difficult to conceal, nor do they require farmers, or complex, clandestine, and vulnerable modes of transportation.

Instead, these new drugs can be synthesized in small and mobile laboratories located in any part of the globe and delivered anonymously, often by mail, to the users’ addresses. In addition, there remains ample illegal access to the older addicting agricultural chemicals and access to the many addicting legal chemicals that are widely used in the practice of medicine (for example, prescription drugs, including opioids). These abundant and varied sources make addicting drugs widely available to millions of Americans. Strong supply reduction efforts are needed. We must use the Drug Enforcement Administration to increase the cost of doing business in the illegal drug supply chain, and decrease access to drugs by bolstering interdiction and reducing precursor access. We can work to screen packages for drugs sent by U.S. mail or other express services.

It is gratifying to see so many of the missing pieces identified in the classic report3 published in 2012 by Columbia University in New York. Health care providers and professionals-in-training are being taught addiction medicine principles and practices. The Surgeon General has helped mobilize the public response to this crisis, and rightly suggested4 that everyone learn how to use and carry naloxone. Researchers are refocused on more than supply reduction.5 In addition, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) are working on delivery service improvements, developing nonopioid pain medications, and new treatments for addiction.

Increase access to naloxone

Increasing access to the opioid reversal medication is critical. Because of the surge in opioid overdose–related mortality, considerable resources have been devoted to emergency response and the widespread dissemination of the mu-opioid receptor antagonist naloxone.6

Naloxone should be readily available without prescription and at a price that makes access practical for emergency technicians and any concerned citizen. Administering naloxone should be analogous to CPR or cardioversion. They are similar, in that they are life-saving actions, but the target within the patient is the brain, rather than the heart. CPR education and cardioversion training efforts and access have been promoted well across the United States and can be done for naloxone.

Another comparison has been made between naloxone and giving an EpiPen to an allergic person in an anaphylaxis emergency or crisis. We need and want to rescue, resuscitate, and revive the overdosed patient and give the person another chance to make a change. We want to administer naloxone and get the patient evaluated and into long-term treatment. Now, rapid return to drug use is common after overdose reversal. We need to use overdose reversal as a path to treatment and see that it is sustained to long-term abstinence from drug use. The most recent report on the high cost of drug use correctly points out that none of the current treatment and policy proposals can reduce substantially the number of overdose deaths.1 Among 11 interventions analyzed by those researchers, making naloxone more available resulted in the greatest number of addiction deaths prevented.

Learn from physician health model of care

An assessment is needed of the 5-year recovery outcomes of all interventions for substance use disorder, including treatments that use and do not use medications, and harm-reduction interventions such as naloxone, needle exchange, and safe injection sites. A few years ago, researchers reported on a sample of 904 physicians consecutively admitted to 16 state Physician Health Programs (PHPs) that was monitored for 5 years or longer.7

This study characterized the outcomes of this episode of care and explored the elements of those programs that could improve the care routinely given to physicians but not to other addicted populations. PHPs were abstinence based and required physicians to abstain from any use of alcohol or other drugs of abuse as assessed by frequent random tests typically lasting for 5 years. Random tests rapidly identified any return to substance use, leading to swift and significant consequences.

Remarkably, 78% of participants had no positive test for either alcohol or drugs over the 5-year period of intensive monitoring. At posttreatment follow-up, 72% of the physicians were continuing to practice medicine. A key to the PHPs’ success is the 5 years of close monitoring with immediate consequences for any use and rapid, vigorous intervention upon any relapse to alcohol or drugs.

The unique PHP care management included close links to the 12-step fellowships of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), Narcotics Anonymous, and other intensive recovery support for the entire 5 years of care management. The PHPs used relatively brief residential and outpatient treatment programs. Given the remarkable long-term outcomes of the PHPs, this model of care management should inspire new approaches to integrated and sustained care management of addiction in health care generally. The 5-year recovery standard should be applied to all addiction treatments to judge their value.8

Re-energize prevention efforts

The country must integrate addiction care into all of health care in the model of other chronic disease management: from prevention to intervention, treatment, monitoring, and intervention for any relapse. For prevention, we must retarget the health goal for youth under age 21 of no use of alcohol, nicotine, marijuana, or other drugs. Substance use disorders, including opioid use disorders, can be traced to adolescent use of alcohol and other drugs. The younger the age of a person initiating the use of any addicting substance – and the more chronic that use – the greater the likelihood of subsequent substance use problems persisting, or reigniting, later in life.

This later addiction risk resulting from adolescent drug use is no surprise, given the unique vulnerability of the adolescent brain, a brain that is especially vulnerable to addicting chemicals and that is not fully developed until about age 25. Effective addiction prevention – for example, helping youth grow up drug free – can improve dramatically public health by reducing the lifetime prevalence of substance use disorders, including opioid addiction.

Youth prevention efforts today vary tremendously in message and scope. Often, prevention messages for youth are limited to specific drugs (for example, nonmedical use of prescription drugs or tobacco) to specific situations (e.g., drunk driving), or to specific amounts of drug use (for example, binge drinking) when all substance use among youth is linked and all drug use poses health risks during adolescence and beyond. Among youth aged 12-17, the use of any one of the three most widely used and available drugs – alcohol, nicotine, and marijuana – increases the likelihood of using the other two drugs, as well as other illicit drugs.9 Similarly, no use of alcohol, nicotine, or marijuana decreases the likelihood of using the others, or of using other illicit drugs.

A recent clinical report and policy statement issued by the American Academy of Pediatrics affirms that it is in the best interests of young patients to not use any substances.10 The screening recommendations issued by the AAP further encourage pediatricians and adolescent medicine physicians to help guide their patients to this fundamental and easily-understood health goal.

A new and better vision for addiction prevention must focus on the single, clear goal of no use of alcohol, nicotine, marijuana, or other drugs for health by youth under age 21.11 Some good news for prevention is that, for the past 3 decades, there has been a slow but steadily increasing percentage of American high school seniors reporting abstinence from any use of alcohol, cigarettes, marijuana, and other illicit drugs.12 In 2014, 25.5% of high school seniors reported lifetime abstinence, and fully 50% reported past-month abstinence from all substances. Those figures are dramatic, compared with abstinence rates during the nation’s peak years of youth drug use. In 1978, among high school seniors, 4.4% reported lifetime abstinence from any use of alcohol, cigarettes, marijuana, and other illicit drugs and 21% reported past-month abstinence. Notably, similar increasing rates of abstinence have been recorded among eighth- and 10th-graders. This encouraging and largely overlooked reality demonstrates that the no-use prevention goal for youth is both realistic and attainable.

Expand drug and alcohol courts

We need to rehabilitate the role of the criminal justice system in a public health–oriented policy to achieve two essential goals: 1) to improve supply reduction as described above, and 2) to reshape the criminal justice system as an engine of recovery as it is now for alcohol addiction.

The landmark report, “Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs and Health,” called for a continuum of health care extending from prevention to early identification and treatment of substance use disorders and long-term health care management with the goal of sustained recovery.13 A growing number of pioneering programs within the criminal justice system (for example, Hawaii’s HOPE Probation, South Dakota’s 24/7 Sobriety Project, and drug courts) are using innovative monitoring strategies for individuals with substance use problems, including providing substance use disorder treatment, with results showing reduced substance use, reduced recidivism, and reduced incarceration.14

In HOPE, drug-involved offenders are subject to frequent random drug testing, rather than the typical drug testing done on standard probation, only at the time of scheduled meetings with probation officers. Failure to abstain from drugs or failure to show up for random drug testing always results in a brief jail sanction, usually 2-15 days, depending on the nature and severity of the offense. Upon placement in HOPE at a warning hearing, probationers are encouraged to succeed, and are fully informed of the length of the jail sanctions that will be imposed for each type of violation. They are assured of the certainty and speed with which the sanctions will be applied.

Sanctions are applied consistently and impartially to ensure fairness for all. Substance abuse treatment is available to all offenders who want it and to those who demonstrate a need for treatment through “behavioral triage.” Offenders who test positive for drugs two or more times in short order with jail sanctions are referred for a substance abuse assessment and instructed to follow any recommended treatment. For this reason, offenders in HOPE succeed in treatment – because they are the offenders in most need and are supported by the leverage provided by the court to help them complete treatment.

A randomized, controlled trial compared offenders assigned to HOPE Probation and a control group assigned to probation as usual. Compared with offenders on probation as usual, at 1-year follow-up, HOPE offenders were:

• 55% less likely to be arrested for a new crime.

• 72% less likely to test positive for illegal drugs.

• 61% less likely to skip appointments with their supervisory officer.

• 53% less likely to have their probation revoked.

There also is a growing potential to harness the latent but enormous strength of the families who have confronted and are continuing to confront addiction in a family member. Families and those with addictions can be engaged in alcohol or drug courts, which can act like the PHP for addicted individuals in the criminal justice system.

Implications for treatment

The diversion of medications that are prescribed and intended for patients in pain is just one part of the far larger drug use and overdose problem. An addicted person with a hijacked brain is not the same as a nonaddicted pain patient. Taking medication as prescribed for pain can produce physical dependence, but importantly, this is not addiction. The person who is using drugs – whether or not prescribed – to produce euphoria is a different person from the person in that same body who is abstinent and not using. Talking with a person in active addiction often is frustrating and futile. That addicted user’s brain wants to use drugs.

The PHP system of care management demonstrates that individuals with substance use disorders can refrain from any substance use for extended periods of time with a carrot and stick approach; permitting a physician to earn a livelihood as a physician is the carrot. In medication-assisted treatment (MAT), the carrot is provided by agonist drugs and the comfort-fit they provide in the brain. They protect the patient from anxiety, and reduce stress and craving responsivity. The stick is an environment that is intolerant of continued nonmedical or addicting drug use. This can be the family, an employer, the criminal justice system, or others in a position to insist on abstinence.

PHP care management shows the way to improve all treatment outcomes; however, an even larger lesson can be learned from the millions of Americans now in recovery from addiction to opioids and other drugs. The “evidence” of what recovery is and how it is achieved and sustained is available to everyone who knows or comes into contact with people in recovery. How did that near-miraculous transformation happen? Even more importantly, how is it sustained when relapse is so common in addiction? The millions of Americans in recovery are the inspiration for a new generation of improved addiction treatment.

Addiction reprioritizes the brain toward continued drug use first, rather than family, friends, health, job, or another important remnant of the addicted person’s past having any meaningful standing. It is often a question like that raised by the AA axiom that it is easy to change a cucumber (naive or new drug user) into a pickle (an addict), but turning a pickle into a cucumber is very difficult. Risk-benefit research has shown that drugs change the ability to accurately assess risks and benefits by prioritizing drug use over virtually everything else, including the interests of the drug users themselves.