User login

Pot Shots

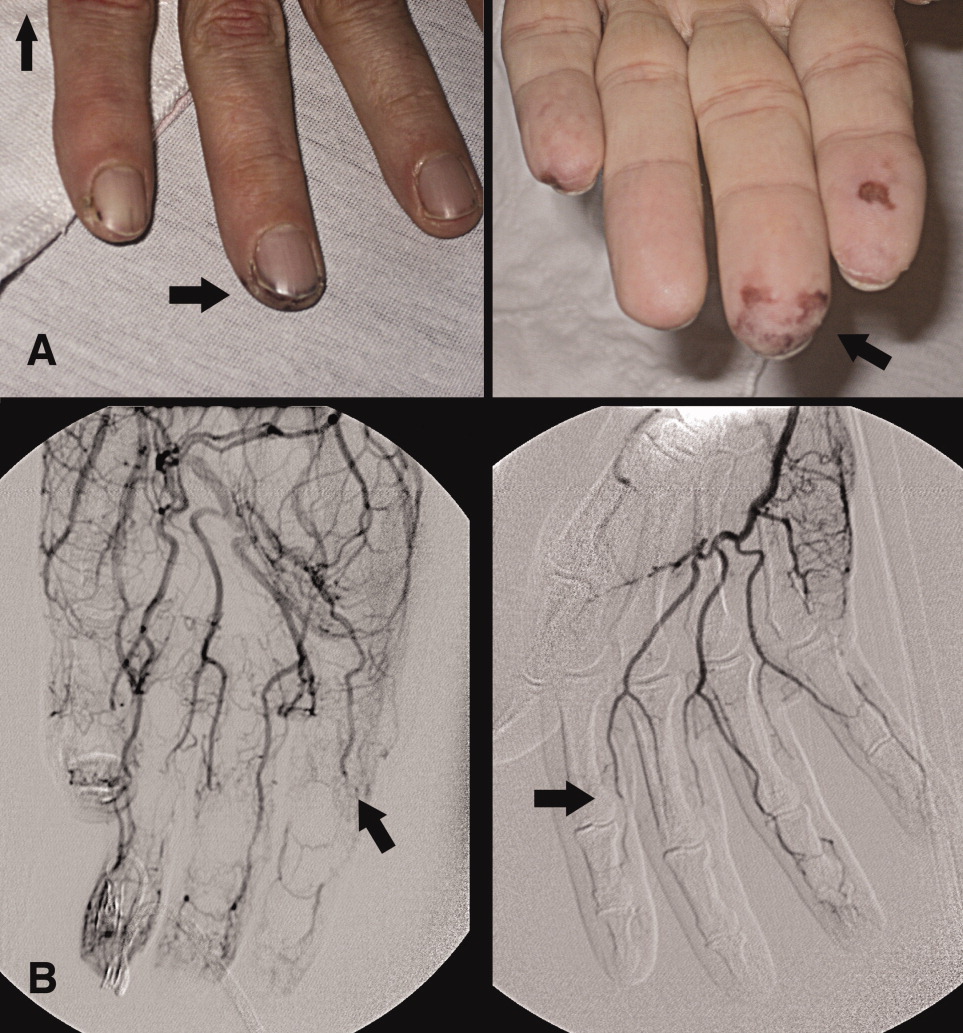

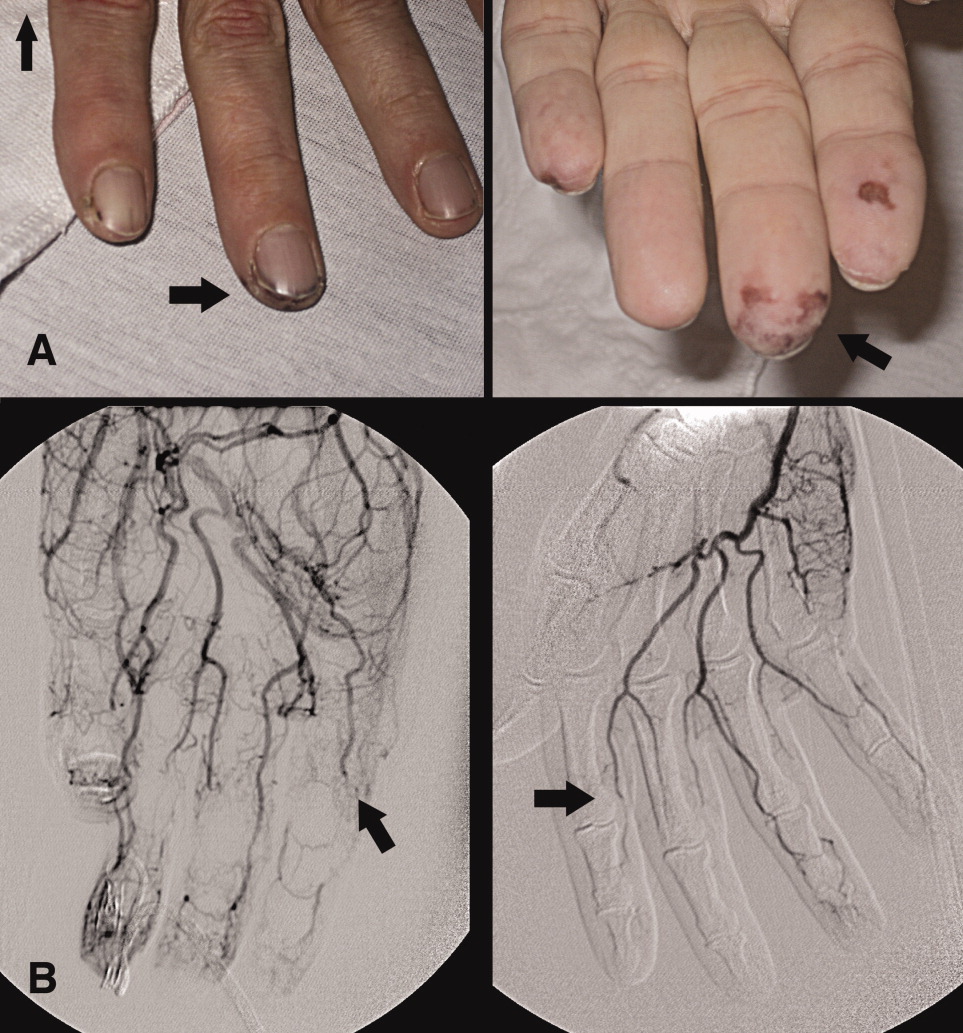

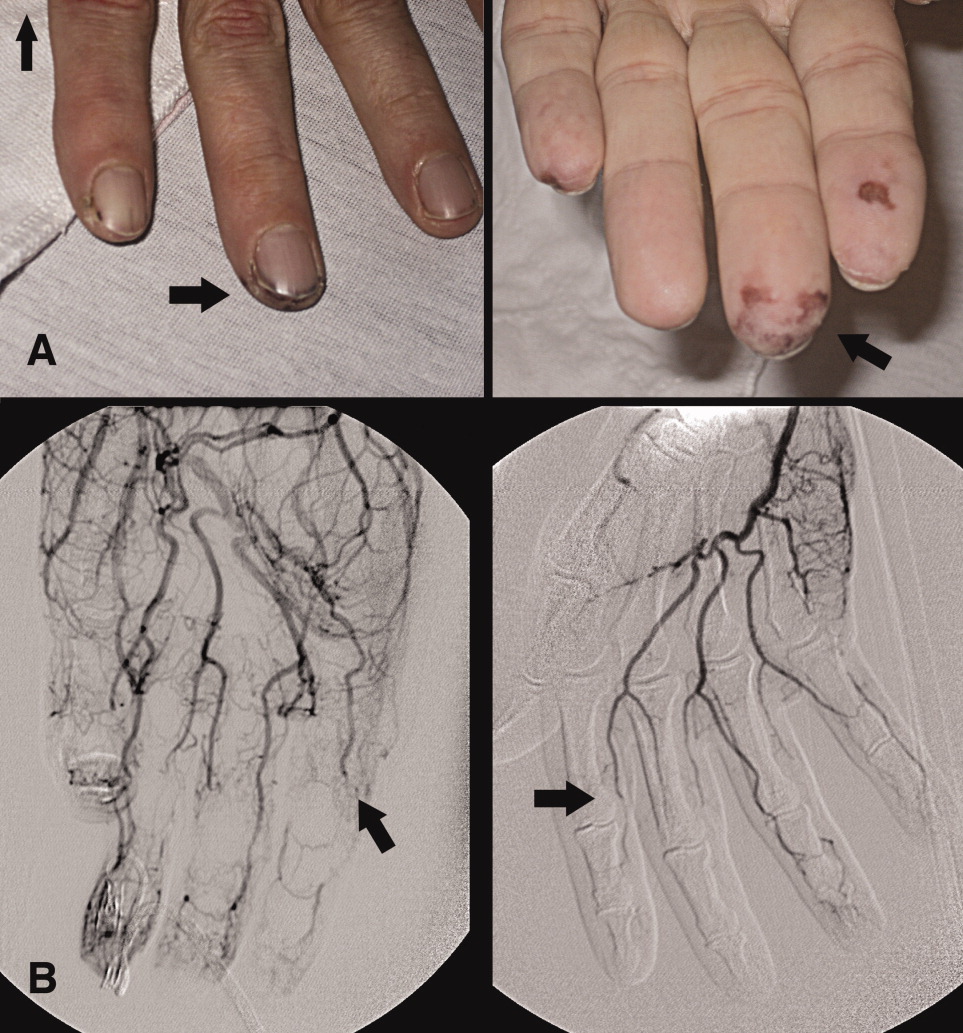

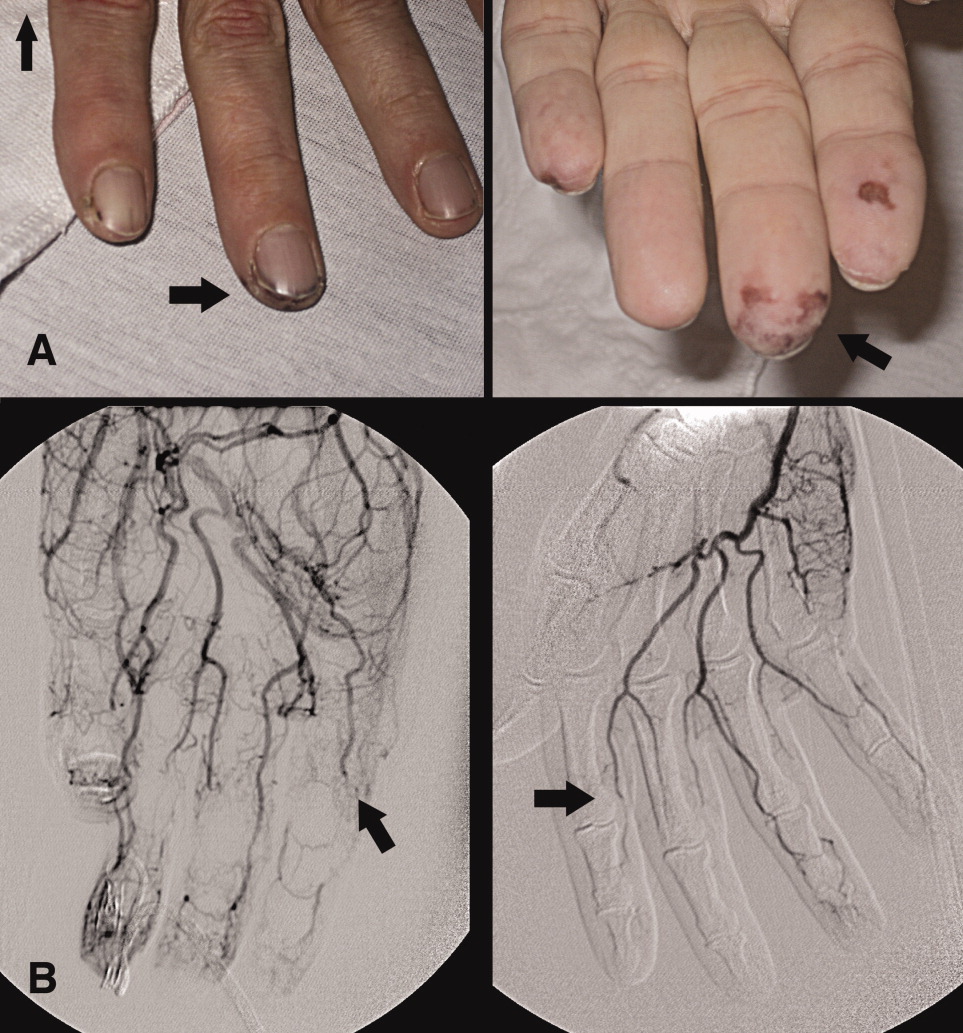

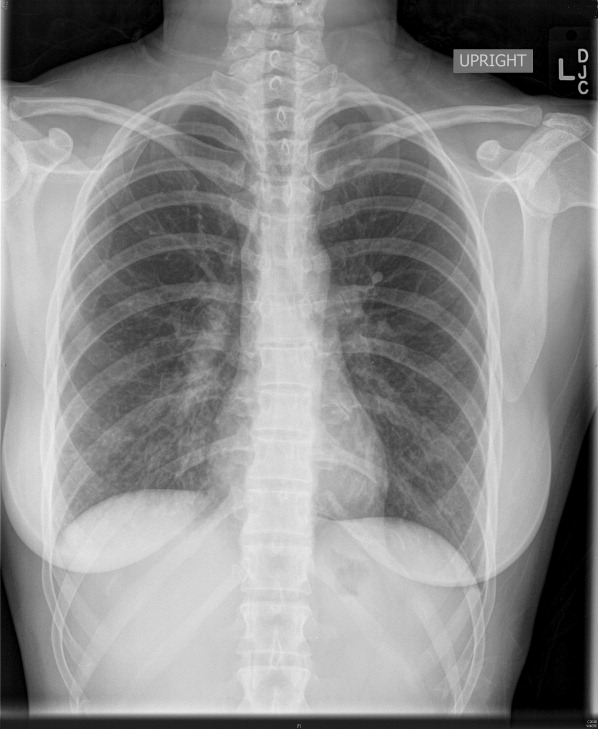

A 46‐year‐old man with a history of heavy marijuana use for 30 years presented to the emergency room with 1 month of progressively worsening distal extremity pain and numbness that had developed into necrosis at the tips of his fingers (Figure 1A, arrows). The patient did not have other systemic symptoms. Transthoracic echocardiogram was normal. An evaluation for hypercoagulable disorders, blood cultures, C‐ANCA, cryoglobulins, Hepatitis C serologies, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) serologies were all negative. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was within normal limits. An arteriogram of the hands showed distal subsegmental obliteration of digital arteries (Figure 1B, arrows), which was consistent with thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger's Disease). While the patient rarely consumed tobacco, he reported smoking up to 10 marijuana cigarettes daily and a diagnosis of cannabis arteritis was made. The patient was encouraged to discontinue smoking and at follow‐up he had marked improvement in symptoms with abstinence from marijuana.

- ,,.Cannabis arteritis.J Am Acad Dermatol.2008;58(5 Suppl 1):S65–S67.

- ,,,,,.Cannabis arteritis.Br J Dermatol.2005;152(1):166–169.

- ,,,,,.Cannabis arteritis: a new case report and a review of literature.J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol.2007;21(3):388–391.

A 46‐year‐old man with a history of heavy marijuana use for 30 years presented to the emergency room with 1 month of progressively worsening distal extremity pain and numbness that had developed into necrosis at the tips of his fingers (Figure 1A, arrows). The patient did not have other systemic symptoms. Transthoracic echocardiogram was normal. An evaluation for hypercoagulable disorders, blood cultures, C‐ANCA, cryoglobulins, Hepatitis C serologies, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) serologies were all negative. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was within normal limits. An arteriogram of the hands showed distal subsegmental obliteration of digital arteries (Figure 1B, arrows), which was consistent with thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger's Disease). While the patient rarely consumed tobacco, he reported smoking up to 10 marijuana cigarettes daily and a diagnosis of cannabis arteritis was made. The patient was encouraged to discontinue smoking and at follow‐up he had marked improvement in symptoms with abstinence from marijuana.

A 46‐year‐old man with a history of heavy marijuana use for 30 years presented to the emergency room with 1 month of progressively worsening distal extremity pain and numbness that had developed into necrosis at the tips of his fingers (Figure 1A, arrows). The patient did not have other systemic symptoms. Transthoracic echocardiogram was normal. An evaluation for hypercoagulable disorders, blood cultures, C‐ANCA, cryoglobulins, Hepatitis C serologies, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) serologies were all negative. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was within normal limits. An arteriogram of the hands showed distal subsegmental obliteration of digital arteries (Figure 1B, arrows), which was consistent with thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger's Disease). While the patient rarely consumed tobacco, he reported smoking up to 10 marijuana cigarettes daily and a diagnosis of cannabis arteritis was made. The patient was encouraged to discontinue smoking and at follow‐up he had marked improvement in symptoms with abstinence from marijuana.

- ,,.Cannabis arteritis.J Am Acad Dermatol.2008;58(5 Suppl 1):S65–S67.

- ,,,,,.Cannabis arteritis.Br J Dermatol.2005;152(1):166–169.

- ,,,,,.Cannabis arteritis: a new case report and a review of literature.J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol.2007;21(3):388–391.

- ,,.Cannabis arteritis.J Am Acad Dermatol.2008;58(5 Suppl 1):S65–S67.

- ,,,,,.Cannabis arteritis.Br J Dermatol.2005;152(1):166–169.

- ,,,,,.Cannabis arteritis: a new case report and a review of literature.J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol.2007;21(3):388–391.

Cold case: Bedside diagnosis of Mycoplasma pneumonia

A 35‐year‐old woman with no past medical history presented to the Emergency Department (ED) with 3 weeks of worsening cough and shortness of breath. Two weeks prior to her presentation she was seen by her primary care physician for flu‐like symptoms, including myalgias, subjective fevers, nonproductive cough, and malaise. She was told that her symptoms were attributable to influenza, and she was treated supportively; however, her symptoms progressed, and she was referred to the ED for further care. Of note, she reported recent cross‐continental air travel as well as an upper respiratory illness in her young child.

On physical exam she was afebrile with normal vital signs and normal room air oxygen saturation. Her oropharynx was clear, and she had no sinus tenderness, rashes, joint swelling, or palpable lymphadenopathy. She was in moderate respiratory distress and had inspiratory crackles at both lung bases.

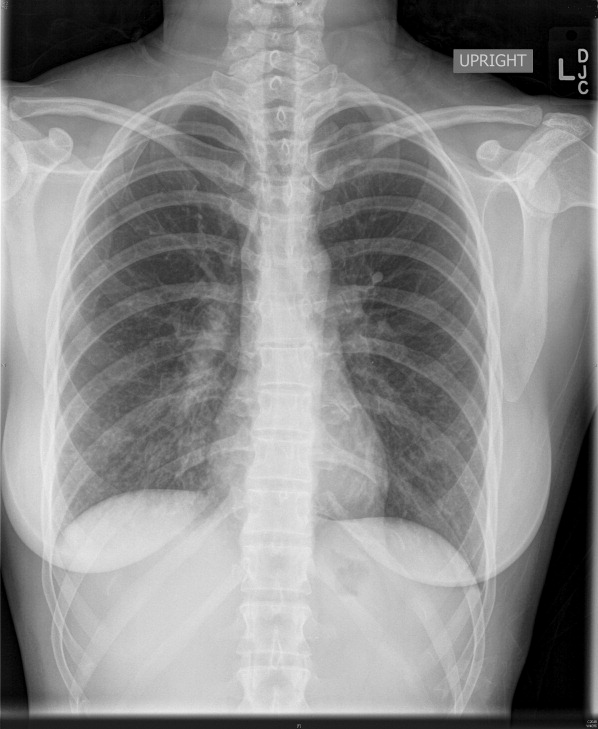

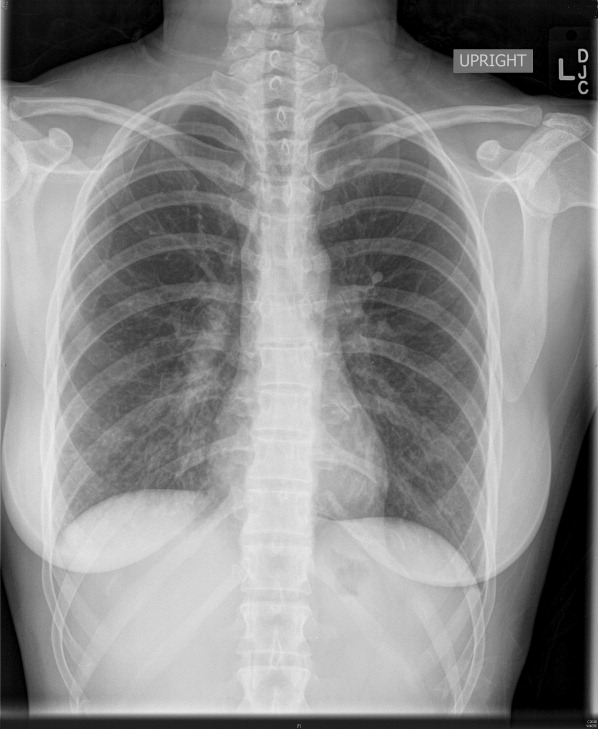

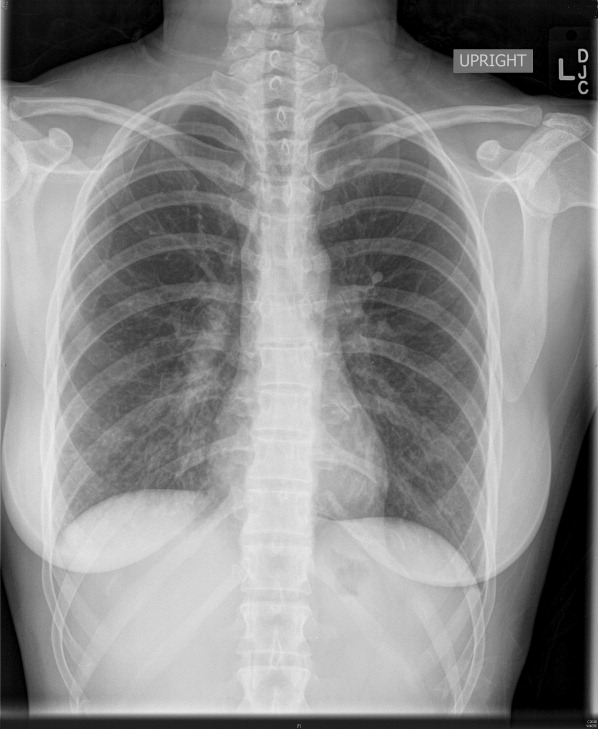

Complete blood count, electrolytes, and electrocardiogram (ECG) were within normal limits. A D‐dimer level was slightly elevated. Chest X‐ray showed a mild hazy opacity at the right lung base (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) angiography of the chest showed bilateral lower lobe infiltrates (Figure 2) but no pulmonary emboli.

A bedside cold agglutinin test, in which the patients blood is drawn into an ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) tube and placed on ice for 30 seconds to 60 seconds, was positive for grains of sand, suggestive of high titers of Mycoplasma pneumoniae immunoglobulin M (IgM) (Figure 3). The patient was discharged with oral antibiotics and reported marked symptomatic relief within 2 days.

The utility of culture and serology for acute diagnosis of M. pneumoniae infection is limited. Cold agglutinins are antibodiesmost commonly IgMthat cross‐react with red blood cell antigens. They develop in 50% to 75% of patients 1 week to 2 weeks following initial exposure to M. pneumoniae and their incidence decreases with age. Within the clinical context of community‐acquired pneumonia, a bedside cold agglutinin test is specific for M. pneumoniae and provides a rapid and inexpensive means for confirming a suspected diagnosis.

A 35‐year‐old woman with no past medical history presented to the Emergency Department (ED) with 3 weeks of worsening cough and shortness of breath. Two weeks prior to her presentation she was seen by her primary care physician for flu‐like symptoms, including myalgias, subjective fevers, nonproductive cough, and malaise. She was told that her symptoms were attributable to influenza, and she was treated supportively; however, her symptoms progressed, and she was referred to the ED for further care. Of note, she reported recent cross‐continental air travel as well as an upper respiratory illness in her young child.

On physical exam she was afebrile with normal vital signs and normal room air oxygen saturation. Her oropharynx was clear, and she had no sinus tenderness, rashes, joint swelling, or palpable lymphadenopathy. She was in moderate respiratory distress and had inspiratory crackles at both lung bases.

Complete blood count, electrolytes, and electrocardiogram (ECG) were within normal limits. A D‐dimer level was slightly elevated. Chest X‐ray showed a mild hazy opacity at the right lung base (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) angiography of the chest showed bilateral lower lobe infiltrates (Figure 2) but no pulmonary emboli.

A bedside cold agglutinin test, in which the patients blood is drawn into an ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) tube and placed on ice for 30 seconds to 60 seconds, was positive for grains of sand, suggestive of high titers of Mycoplasma pneumoniae immunoglobulin M (IgM) (Figure 3). The patient was discharged with oral antibiotics and reported marked symptomatic relief within 2 days.

The utility of culture and serology for acute diagnosis of M. pneumoniae infection is limited. Cold agglutinins are antibodiesmost commonly IgMthat cross‐react with red blood cell antigens. They develop in 50% to 75% of patients 1 week to 2 weeks following initial exposure to M. pneumoniae and their incidence decreases with age. Within the clinical context of community‐acquired pneumonia, a bedside cold agglutinin test is specific for M. pneumoniae and provides a rapid and inexpensive means for confirming a suspected diagnosis.

A 35‐year‐old woman with no past medical history presented to the Emergency Department (ED) with 3 weeks of worsening cough and shortness of breath. Two weeks prior to her presentation she was seen by her primary care physician for flu‐like symptoms, including myalgias, subjective fevers, nonproductive cough, and malaise. She was told that her symptoms were attributable to influenza, and she was treated supportively; however, her symptoms progressed, and she was referred to the ED for further care. Of note, she reported recent cross‐continental air travel as well as an upper respiratory illness in her young child.

On physical exam she was afebrile with normal vital signs and normal room air oxygen saturation. Her oropharynx was clear, and she had no sinus tenderness, rashes, joint swelling, or palpable lymphadenopathy. She was in moderate respiratory distress and had inspiratory crackles at both lung bases.

Complete blood count, electrolytes, and electrocardiogram (ECG) were within normal limits. A D‐dimer level was slightly elevated. Chest X‐ray showed a mild hazy opacity at the right lung base (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) angiography of the chest showed bilateral lower lobe infiltrates (Figure 2) but no pulmonary emboli.

A bedside cold agglutinin test, in which the patients blood is drawn into an ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) tube and placed on ice for 30 seconds to 60 seconds, was positive for grains of sand, suggestive of high titers of Mycoplasma pneumoniae immunoglobulin M (IgM) (Figure 3). The patient was discharged with oral antibiotics and reported marked symptomatic relief within 2 days.

The utility of culture and serology for acute diagnosis of M. pneumoniae infection is limited. Cold agglutinins are antibodiesmost commonly IgMthat cross‐react with red blood cell antigens. They develop in 50% to 75% of patients 1 week to 2 weeks following initial exposure to M. pneumoniae and their incidence decreases with age. Within the clinical context of community‐acquired pneumonia, a bedside cold agglutinin test is specific for M. pneumoniae and provides a rapid and inexpensive means for confirming a suspected diagnosis.