User login

Don't Quit on a Quitter: Helping Your Patient Stop Smoking

Although smoking prevalence among US adults declined by about 42% between 1965 and 2011, this reduction has slowed in recent years. According to 2010 figures from the CDC, 19.3% of US adults (nearly one in five) remain current smokers,1 despite all the evidence of negative effects that tobacco use and smoke exposure exert on good health.2 Each year, 443,000 premature deaths in the US are attributed to cigarette smoking.3

In the face of these discouraging data, and in ongoing efforts to minimize the deadly effects of cigarette smoking, the US Department of Health and Human Services’ program, Healthy People 2020,4 restated its 10-year goals pertaining to tobacco use as put forth in Healthy People 2010.5 These are to reduce the proportion of Americans who currently smoke to 12%, and to increase the proportion of current smokers who have attempted cessation to 80%.4

Though trained to encourage smoking cessation in their patients, health care providers often lack the knowledge, skills, or resources to support patients through the difficulties of discontinuing tobacco use. Whatever barriers clinicians may face in accessing smoking cessation services, the barriers faced by underserved patients are often greater.6 A heightened awareness of these barriers and improved understanding of common smoking cessation methods will help providers better support their patients who are trying to quit.

ASSESSING READINESS AND MOTIVATING PATIENTS

In 2008, the Public Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services, updated its clinical practice guidelines for clinicians who manage tobacco-dependent patients.7 According to evidence from randomized controlled trials, even brief interventions on the health care provider’s part (such as raising the issue of smoking cessation at each patient visit to determine whether the patient is ready to quit) can prompt the patient to seriously consider smoking abstinence.3,8 Being asked repeatedly can advance a patient’s readiness, and any attempts patients make to quit must be robustly supported.9

The Public Health Service’s five A’s3,7 outline the recommended conversation with patients:

Ask about tobacco use;

Advise tobacco users to quit in strong, clear terms;

Assess readiness for tobacco cessation;

Assist in developing a plan to stop tobacco use; and

Arrange a follow-up consultation to review the patient’s success or to reassess cessation readiness.

Whenever a patient expresses any interest in smoking cessation, it is essential for the clinician to respond with motivation. To help the patient prepare to stop, the clinician must address the five R’s7:

Relevance—the importance of smoking cessation to the patient;

Risks of continuing to smoke, particularly health concerns;

Rewards of smoking cessation, especially alleviation of health complaints;

Roadblocks that contribute to the threat of relapse—but which can be overcome with sufficient motivation; and

Repetition of support and reinforcement for this healthy lifestyle choice, be it from family, friends, coworkers, or the clinician. To prepare for times when support seems to wane, patients should be encouraged to phone 1-800-QUITNOW, a number that will connect the caller to his or her state’s quit line.

Repetition may also imply repeated cessation attempts if the first (or most recent) was unsuccessful. According to findings from a literature review, the reasons smokers relapse are numerous, including cravings (the most common) and withdrawal symptoms, weight gain, stress, and exposure to other smokers.10,11 Interventions based on patients’ given reasons for relapse have no apparent impact on the rate of return to smoking.12 Nevertheless, clinicians must take responsibility to motivate patients and reinforce their successes at every encounter.

UNAIDED CESSATION

In a culture demanding quick results and in the context of ongoing pharmaceutical advertisements and aisles lined with quit-smoking products, it may be easy to dismiss unaided cessation. Options range from gradual cutting down to the abrupt discontinuation of tobacco—going cold turkey. Although little research has been devoted to these strategies,13 unaided cessation is the method patients most often cite in their attempts to quit—and the method successful quitters report as most effective.14,15 The patients most likely to succeed at quitting are those who do not ask for help.

ASSISTED CESSATION

Patients with a significant dependence on nicotine are likely to request assistance with cessation.15 Identifying those who struggle to quit smoking and offering appropriate support may represent the difference between their success and failure.9

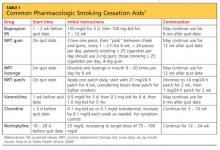

Several available tools to support patients’ “quit smoking” efforts, including pharmacologic options (see table7), are described here.

Nicotine Replacement Therapy

Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) is used to reduce nicotine withdrawal symptoms by replacing smoking-produced nicotine with an alternate source of delivery. NRT is currently available in several forms: a transdermal patch, gum, lozenge, or the electronic cigarette. The chance of successful quitting is increased 50% to 70% when NRT is used, compared with patients using placebo.16 While the various forms of NRT share the same goal, they are not equally effective.17

Nicotine transdermal patches have been used in the US since 1991. The patches are used in a stepwise fashion; each patch delivers nicotine at a consistent quantity per hour, and over time, patches with increasingly lower doses of nicotine are substituted. There is some evidence that the patch is more efficacious for maintenance after smoking cessation than for the initial effort to quit.18

Nicotine gum and lozenges, orally absorbed forms of NRT, are used as needed, depending on patients’ withdrawal symptoms. Japuntich et al18 found that these products alone are not beneficial. However, combining bupropion with gum or lozenge therapy was found more effective for patients attempting to stop smoking than either agent alone.18 Lozenges have also been described as increasingly beneficial when combined with a longer-acting NRT, such as a transdermal patch, when cravings increase and rapid delivery of nicotine is required.16

The electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) is a battery-operated device that aerosolizes liquid nicotine, which is then orally absorbed. In a 2011 study, Siegel et al19 found that more than two-thirds of smokers reduced the number of cigarettes smoked after using an e-cigarette. Six months after subjects first purchased e-cigarettes, 31% remained tobacco-abstinent.

Since e-cigarettes are flameless, their use has been suggested in areas where smoking was previously prohibited. This short-acting NRT may benefit a patient when craving is provoked by forced denial of nicotine.

Current research is under way to examine two newer potential NRT tools: a nicotine mouth spray and a nicotine vaccine.20,21 In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, Tønnesen et al20 found that use of a nicotine mouth spray was associated with significantly higher rates of tobacco abstinence at six, 24, and 52 weeks, compared with patients receiving placebo; however, rates of adverse effects were high in both groups (88% and 71%, respectively).

NRT is inexpensive and easily accessible to patients. Since its forms are all available OTC, consultation with health care providers is unnecessary. For patients who have tried to quit smoking unaided and who need short-term or immediate assistance to prevent a smoking relapse, NRT can be a helpful resource.

Bupropion

For smokers who want to quit without using a nicotine-based intervention, the antidepressant bupropion can be a promising smoking cessation aid. It is not clear what mechanism of action helps smokers who take bupropion to stop, although its chemical structure resembles that of diethylpropion, a drug used as an appetite suppressant.22 Bupropion does hinder norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake in the nervous system—opposing an effect of nicotine withdrawal.

Bupropion’s effects as an antidepressant and as a smoking cessation aid do not appear to be related.22 For this reason, even a patient who has not responded to bupropion for treatment of depression may benefit from using it as a smoking cessation aid.

Bupropion may be used alone or with other agents to stop nicotine use. Many study groups report that a combination of medications is more effective than monotherapy, and this is true for combinations that include bupropion.23-26 When used with nicotine lozenges, bupropion has been found effective in preventing a return to tobacco after previous lapses in smoking abstinence. Aside from a nicotine patch, no other monotherapy or combination was effective at achieving this goal.18 Thus, bupropion may be best utilized as a component in combination therapy.

Varenicline

Approved for use in the US in 2006, varenicline is the newest pharmaceutical therapy for smoking cessation. As a partial nicotinic receptor agonist,7 varenicline prevents nicotine from activating the mesolimbic dopamine system, which is associated with pleasure and reward (among other functions). By stimulating the nervous system’s dopamine (though to a lesser extent than nicotine), this agent reduces cravings for tobacco and symptoms of nicotine withdrawal—which are among the greatest barriers to smoking cessation.10 Because of its mechanism of action, varenicline is not often used in combination with NRT.

Varenicline has been shown to be as effective as the combination therapy of bupropion with nicotine lozenges.7,27 UK investigators Hajek et al27 found that using varenicline for four weeks before attempting to stop smoking had minimal effect on smoking urges and withdrawal symptoms, compared with using varenicline for just one week before attempting to quit. However, those who used varenicline for four weeks before stopping smoking were more likely to be smoke-free at 12 weeks than those who had used it for just one week before quitting.27

Other Pharmaceutical Options

Clonidine, long recognized as an effective antihypertensive medication, was determined by Gourlay et al9 in a 2004 review to have potential for use in supporting smoking cessation. Because significant adverse events (including drowsiness, sedation, and postural hypotension) have been associated with clonidine use7,28 and the FDA has not yet approved it for the indication of smoking cessation, its use may be most appropriate as a second-line treatment option, in combination with bupropion or nortriptyline, or for specialists’ use.28 Clonidine should not be discontinued suddenly.

Like bupropion, the tricyclic antidepressant nortriptyline has been investigated for its potential in tobacco cessation therapy. While a significant amount is known about plasma concentrations of nortriptyline needed to treat depression, levels required for effective tobacco cessation are less clear. Mooney et al29 found that therapeutic plasma concentrations of nortriptyline varied among subjects by race and smoking habits; although a lower concentration was usually required to assist smoking cessation than to treat depression, adverse effects were common even at lower concentrations. Thus, it was recommended that nortriptyline be reserved for second-line treatment.

This summer, researchers for the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Review Group published a review of the literature (including phase II and phase III trials conducted by pharmaceutical companies—making the risk for bias “high or unclear”) pertaining to two nicotine vaccines in development.21 In two studies, the level of development of nicotine antibodies was associated with commensurate cessation rates; in two others, the outcome measure (12 months’ abstinence from smoking) was met in 11% of subjects, whether they received the vaccine or placebo. Thus, no strong evidence yet exists that nicotine vaccination supports smoking cessation in the long term; further research is needed.

NONPHARMACEUTICAL

INTERVENTIONS

Acupuncture

Variations and modifications of the traditional Chinese therapy of acupuncture, including acupressure and electrostimulation, have been examined in a number of clinical trials. Despite the supporting rhetoric, objective research of good quality in this area is limited. However, one systematic literature review showed acupuncture to be only slightly more effective than sham interventions and less effective than NRT.30 Insufficient evidence was reported on acupressure and laser stimulation, and acupressure was no more effective than psychological treatments. Considering questionable study quality and other limitations in the currently available research, practitioners should not consider acupuncture or related interventions as first-line options—nor should their potential be dismissed altogether.

Hypnotherapy

Conclusive research findings regarding hypnotherapy as an effective treatment for tobacco dependence are also limited. In 2010, Barnes at al31 reviewed 11 studies comparing hypnotherapy with various alternate methods and found little difference in effectiveness among hypnotherapy, psychological counseling, and rapid smoking therapy. Despite the limitations in these data, however, hypnotherapy may be appropriate for some patients.

CONCLUSION

Tobacco dependence is not the same for any two patients. Just as health care providers do not use the same treatment option for every patient with hypertension or diabetes, treatment for tobacco-dependent patients must also be individualized.

Our professional goal is to care for the health of patients. We clinicians must recommend cessation to our patients who smoke at every encounter—and offer support often. When we miss an opportunity to counsel a patient on the importance of quitting, the patient may interpret our silence as condoning the behavior. Empowering patients with an understanding of the options can contribute to their success—a significant move toward better health.

The authors of Healthy People 2020 hope that 80% of current smokers will have tried to stop smoking by that year. Have 80% of your patients been counseled and offered assistance to stop?

REFERENCES

1. CDC. Current cigarette smoking prevalence among working adults—United States, 2004-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(38):1305-1309.

2. CDC. Vital signs: current cigarette smoking among adults aged ≥ 18 years—United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(35):1135-1140.

3. Jamal A, Dube SR, Malarcher AM, et al; CDC. Tobacco use screening and counseling during physician office visits among adults—National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2005-2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61 suppl: 38-45.

4. US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020 summary of objectives: tobacco use. http://healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/pdfs/TobaccoUse.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2012.

5. US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010 archives. www.healthypeople.gov/2010. Accessed October 18, 2012.

6. Blumenthal DS. Barriers to the provision of smoking cessation services reported by clinicians in underserved communities. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007;20(3):272-279.

7. Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, et al; Public Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services. Clinical practice guideline: treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. www.ahrq.gov/clinic/tobacco/treating_tobacco_use08.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2012.

8. Carson KV, Verbiest ME, Crone MR, et al. Training health professionals in smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 May 16; 5:CD000214.

9. Gourlay SG, Stead LF, Benowitz NL. Clonidine for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD000058.

10. Guirguis AB, Ray SM, Zingone MM, et al. Smoking cessation: barriers to success and readiness to change. Tenn Med. 2010;103(9):45-49.

11. Nørregaard J, Tønnesen P, Petersen L. Predictors and reasons for relapse in smoking cessation with nicotine and placebo patches. Prev Med. 1993;22(2):261-271.

12. Lancaster T, Hajek P, Stead LF, et al. Prevention of relapse after quitting smoking: a systematic review of trials. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(8): 828-835.

13. Chapman S, MacKenzie R. The global research neglect of unassisted smoking cessation: causes and consequences. PLoS Med. 2010;7(2):e1000216.

14. Hung WT, Dunlop SM, Perez D, Cotter T. Use and perceived helpfulness of smoking cessation methods: results from a population survey of recent quitters. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:592.

15. Shiffman S, Brockwell SE, Pillitteri JL, Gitchell JG. Use of smoking-cessation treatments in the United States. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(2):102-111.

16. Stead LF, Perera R, Bullen C, et al. Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 Jan 23;(1):CD000146.

17. Robles GI, Singh-Franco D, Ghin HL. A review of the efficacy of smoking-cessation pharmacotherapies in nonwhite populations. Clin Ther. 2008;30(5):800-812.

18. Japuntich SJ, Piper ME, Leventhal AM, et al. The effect of five smoking cessation pharmacotherapies on smoking cessation milestones. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79(1):34-42.

19. Siegel MB, Tanwar KL, Wood KS. Electronic cigarettes as a smoking-cessation tool: results from an online survey. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40 (4):472-475.

20. Tønnesen P, Lauri H, Perfekt R, et al. Efficacy of a nicotine mouth spray in smoking cessation: a randomised, double-blind trial. Eur Respir J. 2012;40(3):548-554.

21. Hartmann-Boyce J, Cahill K, Hatsukami D, Cornuz J. Nicotine vaccines for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Aug 15;8:CD007072.

22. Roddy E. Bupropion and other non-nicotine pharmacotherapies. BMJ. 2004;328(7438):

509-511.

23. Loh WY, Piper ME, Schlam TR, et al. Should all smokers use combination smoking cessation pharmacotherapy? Using novel analytic methods to detect differential treatment effects over 8 weeks of pharmacotherapy. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(2):131-141.

24. Bolt DM, Piper ME, Theobald WE, Baker TB. Why two smoking cessation agents work better than one: role of craving suppression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(1):44-65.

25. McNeil JJ, Piccenna L, Ioannides-Demos LL. Smoking cessation: recent advances. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2010;24(4):359-367.

26. Ebbert JO, Hays JT, Hurt RD. Combination pharmacotherapy for stopping smoking: what advantages does it offer? Drugs. 2010;70(6):643-650.

27. Hajek P, McRobbie HJ, Myers KE, et al. Use of varenicline for 4 weeks before quitting smoking: decrease in ad lib smoking and increase in smoking cessation rates. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171 (8):770-777.

28. Bentz CJ. Review: clonidine is more effective than placebo for long-term smoking cessation, but has side effects. ACP J Club. 2005;142(1):12.

29. Mooney ME, Reus VI, Gorecki J, et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring of nortriptyline in smoking cessation: a multistudy analysis. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;83(3):436-442.

30. White AR, Rampes H, Liu JP, et al. Acupuncture and related interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(1): CD000009.

31. Barnes J, Dong CY, McRobbie H, et al. Hypnotherapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(10):CD001008.

Although smoking prevalence among US adults declined by about 42% between 1965 and 2011, this reduction has slowed in recent years. According to 2010 figures from the CDC, 19.3% of US adults (nearly one in five) remain current smokers,1 despite all the evidence of negative effects that tobacco use and smoke exposure exert on good health.2 Each year, 443,000 premature deaths in the US are attributed to cigarette smoking.3

In the face of these discouraging data, and in ongoing efforts to minimize the deadly effects of cigarette smoking, the US Department of Health and Human Services’ program, Healthy People 2020,4 restated its 10-year goals pertaining to tobacco use as put forth in Healthy People 2010.5 These are to reduce the proportion of Americans who currently smoke to 12%, and to increase the proportion of current smokers who have attempted cessation to 80%.4

Though trained to encourage smoking cessation in their patients, health care providers often lack the knowledge, skills, or resources to support patients through the difficulties of discontinuing tobacco use. Whatever barriers clinicians may face in accessing smoking cessation services, the barriers faced by underserved patients are often greater.6 A heightened awareness of these barriers and improved understanding of common smoking cessation methods will help providers better support their patients who are trying to quit.

ASSESSING READINESS AND MOTIVATING PATIENTS

In 2008, the Public Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services, updated its clinical practice guidelines for clinicians who manage tobacco-dependent patients.7 According to evidence from randomized controlled trials, even brief interventions on the health care provider’s part (such as raising the issue of smoking cessation at each patient visit to determine whether the patient is ready to quit) can prompt the patient to seriously consider smoking abstinence.3,8 Being asked repeatedly can advance a patient’s readiness, and any attempts patients make to quit must be robustly supported.9

The Public Health Service’s five A’s3,7 outline the recommended conversation with patients:

Ask about tobacco use;

Advise tobacco users to quit in strong, clear terms;

Assess readiness for tobacco cessation;

Assist in developing a plan to stop tobacco use; and

Arrange a follow-up consultation to review the patient’s success or to reassess cessation readiness.

Whenever a patient expresses any interest in smoking cessation, it is essential for the clinician to respond with motivation. To help the patient prepare to stop, the clinician must address the five R’s7:

Relevance—the importance of smoking cessation to the patient;

Risks of continuing to smoke, particularly health concerns;

Rewards of smoking cessation, especially alleviation of health complaints;

Roadblocks that contribute to the threat of relapse—but which can be overcome with sufficient motivation; and

Repetition of support and reinforcement for this healthy lifestyle choice, be it from family, friends, coworkers, or the clinician. To prepare for times when support seems to wane, patients should be encouraged to phone 1-800-QUITNOW, a number that will connect the caller to his or her state’s quit line.

Repetition may also imply repeated cessation attempts if the first (or most recent) was unsuccessful. According to findings from a literature review, the reasons smokers relapse are numerous, including cravings (the most common) and withdrawal symptoms, weight gain, stress, and exposure to other smokers.10,11 Interventions based on patients’ given reasons for relapse have no apparent impact on the rate of return to smoking.12 Nevertheless, clinicians must take responsibility to motivate patients and reinforce their successes at every encounter.

UNAIDED CESSATION

In a culture demanding quick results and in the context of ongoing pharmaceutical advertisements and aisles lined with quit-smoking products, it may be easy to dismiss unaided cessation. Options range from gradual cutting down to the abrupt discontinuation of tobacco—going cold turkey. Although little research has been devoted to these strategies,13 unaided cessation is the method patients most often cite in their attempts to quit—and the method successful quitters report as most effective.14,15 The patients most likely to succeed at quitting are those who do not ask for help.

ASSISTED CESSATION

Patients with a significant dependence on nicotine are likely to request assistance with cessation.15 Identifying those who struggle to quit smoking and offering appropriate support may represent the difference between their success and failure.9

Several available tools to support patients’ “quit smoking” efforts, including pharmacologic options (see table7), are described here.

Nicotine Replacement Therapy

Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) is used to reduce nicotine withdrawal symptoms by replacing smoking-produced nicotine with an alternate source of delivery. NRT is currently available in several forms: a transdermal patch, gum, lozenge, or the electronic cigarette. The chance of successful quitting is increased 50% to 70% when NRT is used, compared with patients using placebo.16 While the various forms of NRT share the same goal, they are not equally effective.17

Nicotine transdermal patches have been used in the US since 1991. The patches are used in a stepwise fashion; each patch delivers nicotine at a consistent quantity per hour, and over time, patches with increasingly lower doses of nicotine are substituted. There is some evidence that the patch is more efficacious for maintenance after smoking cessation than for the initial effort to quit.18

Nicotine gum and lozenges, orally absorbed forms of NRT, are used as needed, depending on patients’ withdrawal symptoms. Japuntich et al18 found that these products alone are not beneficial. However, combining bupropion with gum or lozenge therapy was found more effective for patients attempting to stop smoking than either agent alone.18 Lozenges have also been described as increasingly beneficial when combined with a longer-acting NRT, such as a transdermal patch, when cravings increase and rapid delivery of nicotine is required.16

The electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) is a battery-operated device that aerosolizes liquid nicotine, which is then orally absorbed. In a 2011 study, Siegel et al19 found that more than two-thirds of smokers reduced the number of cigarettes smoked after using an e-cigarette. Six months after subjects first purchased e-cigarettes, 31% remained tobacco-abstinent.

Since e-cigarettes are flameless, their use has been suggested in areas where smoking was previously prohibited. This short-acting NRT may benefit a patient when craving is provoked by forced denial of nicotine.

Current research is under way to examine two newer potential NRT tools: a nicotine mouth spray and a nicotine vaccine.20,21 In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, Tønnesen et al20 found that use of a nicotine mouth spray was associated with significantly higher rates of tobacco abstinence at six, 24, and 52 weeks, compared with patients receiving placebo; however, rates of adverse effects were high in both groups (88% and 71%, respectively).

NRT is inexpensive and easily accessible to patients. Since its forms are all available OTC, consultation with health care providers is unnecessary. For patients who have tried to quit smoking unaided and who need short-term or immediate assistance to prevent a smoking relapse, NRT can be a helpful resource.

Bupropion

For smokers who want to quit without using a nicotine-based intervention, the antidepressant bupropion can be a promising smoking cessation aid. It is not clear what mechanism of action helps smokers who take bupropion to stop, although its chemical structure resembles that of diethylpropion, a drug used as an appetite suppressant.22 Bupropion does hinder norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake in the nervous system—opposing an effect of nicotine withdrawal.

Bupropion’s effects as an antidepressant and as a smoking cessation aid do not appear to be related.22 For this reason, even a patient who has not responded to bupropion for treatment of depression may benefit from using it as a smoking cessation aid.

Bupropion may be used alone or with other agents to stop nicotine use. Many study groups report that a combination of medications is more effective than monotherapy, and this is true for combinations that include bupropion.23-26 When used with nicotine lozenges, bupropion has been found effective in preventing a return to tobacco after previous lapses in smoking abstinence. Aside from a nicotine patch, no other monotherapy or combination was effective at achieving this goal.18 Thus, bupropion may be best utilized as a component in combination therapy.

Varenicline

Approved for use in the US in 2006, varenicline is the newest pharmaceutical therapy for smoking cessation. As a partial nicotinic receptor agonist,7 varenicline prevents nicotine from activating the mesolimbic dopamine system, which is associated with pleasure and reward (among other functions). By stimulating the nervous system’s dopamine (though to a lesser extent than nicotine), this agent reduces cravings for tobacco and symptoms of nicotine withdrawal—which are among the greatest barriers to smoking cessation.10 Because of its mechanism of action, varenicline is not often used in combination with NRT.

Varenicline has been shown to be as effective as the combination therapy of bupropion with nicotine lozenges.7,27 UK investigators Hajek et al27 found that using varenicline for four weeks before attempting to stop smoking had minimal effect on smoking urges and withdrawal symptoms, compared with using varenicline for just one week before attempting to quit. However, those who used varenicline for four weeks before stopping smoking were more likely to be smoke-free at 12 weeks than those who had used it for just one week before quitting.27

Other Pharmaceutical Options

Clonidine, long recognized as an effective antihypertensive medication, was determined by Gourlay et al9 in a 2004 review to have potential for use in supporting smoking cessation. Because significant adverse events (including drowsiness, sedation, and postural hypotension) have been associated with clonidine use7,28 and the FDA has not yet approved it for the indication of smoking cessation, its use may be most appropriate as a second-line treatment option, in combination with bupropion or nortriptyline, or for specialists’ use.28 Clonidine should not be discontinued suddenly.

Like bupropion, the tricyclic antidepressant nortriptyline has been investigated for its potential in tobacco cessation therapy. While a significant amount is known about plasma concentrations of nortriptyline needed to treat depression, levels required for effective tobacco cessation are less clear. Mooney et al29 found that therapeutic plasma concentrations of nortriptyline varied among subjects by race and smoking habits; although a lower concentration was usually required to assist smoking cessation than to treat depression, adverse effects were common even at lower concentrations. Thus, it was recommended that nortriptyline be reserved for second-line treatment.

This summer, researchers for the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Review Group published a review of the literature (including phase II and phase III trials conducted by pharmaceutical companies—making the risk for bias “high or unclear”) pertaining to two nicotine vaccines in development.21 In two studies, the level of development of nicotine antibodies was associated with commensurate cessation rates; in two others, the outcome measure (12 months’ abstinence from smoking) was met in 11% of subjects, whether they received the vaccine or placebo. Thus, no strong evidence yet exists that nicotine vaccination supports smoking cessation in the long term; further research is needed.

NONPHARMACEUTICAL

INTERVENTIONS

Acupuncture

Variations and modifications of the traditional Chinese therapy of acupuncture, including acupressure and electrostimulation, have been examined in a number of clinical trials. Despite the supporting rhetoric, objective research of good quality in this area is limited. However, one systematic literature review showed acupuncture to be only slightly more effective than sham interventions and less effective than NRT.30 Insufficient evidence was reported on acupressure and laser stimulation, and acupressure was no more effective than psychological treatments. Considering questionable study quality and other limitations in the currently available research, practitioners should not consider acupuncture or related interventions as first-line options—nor should their potential be dismissed altogether.

Hypnotherapy

Conclusive research findings regarding hypnotherapy as an effective treatment for tobacco dependence are also limited. In 2010, Barnes at al31 reviewed 11 studies comparing hypnotherapy with various alternate methods and found little difference in effectiveness among hypnotherapy, psychological counseling, and rapid smoking therapy. Despite the limitations in these data, however, hypnotherapy may be appropriate for some patients.

CONCLUSION

Tobacco dependence is not the same for any two patients. Just as health care providers do not use the same treatment option for every patient with hypertension or diabetes, treatment for tobacco-dependent patients must also be individualized.

Our professional goal is to care for the health of patients. We clinicians must recommend cessation to our patients who smoke at every encounter—and offer support often. When we miss an opportunity to counsel a patient on the importance of quitting, the patient may interpret our silence as condoning the behavior. Empowering patients with an understanding of the options can contribute to their success—a significant move toward better health.

The authors of Healthy People 2020 hope that 80% of current smokers will have tried to stop smoking by that year. Have 80% of your patients been counseled and offered assistance to stop?

REFERENCES

1. CDC. Current cigarette smoking prevalence among working adults—United States, 2004-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(38):1305-1309.

2. CDC. Vital signs: current cigarette smoking among adults aged ≥ 18 years—United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(35):1135-1140.

3. Jamal A, Dube SR, Malarcher AM, et al; CDC. Tobacco use screening and counseling during physician office visits among adults—National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2005-2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61 suppl: 38-45.

4. US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020 summary of objectives: tobacco use. http://healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/pdfs/TobaccoUse.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2012.

5. US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010 archives. www.healthypeople.gov/2010. Accessed October 18, 2012.

6. Blumenthal DS. Barriers to the provision of smoking cessation services reported by clinicians in underserved communities. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007;20(3):272-279.

7. Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, et al; Public Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services. Clinical practice guideline: treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. www.ahrq.gov/clinic/tobacco/treating_tobacco_use08.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2012.

8. Carson KV, Verbiest ME, Crone MR, et al. Training health professionals in smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 May 16; 5:CD000214.

9. Gourlay SG, Stead LF, Benowitz NL. Clonidine for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD000058.

10. Guirguis AB, Ray SM, Zingone MM, et al. Smoking cessation: barriers to success and readiness to change. Tenn Med. 2010;103(9):45-49.

11. Nørregaard J, Tønnesen P, Petersen L. Predictors and reasons for relapse in smoking cessation with nicotine and placebo patches. Prev Med. 1993;22(2):261-271.

12. Lancaster T, Hajek P, Stead LF, et al. Prevention of relapse after quitting smoking: a systematic review of trials. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(8): 828-835.

13. Chapman S, MacKenzie R. The global research neglect of unassisted smoking cessation: causes and consequences. PLoS Med. 2010;7(2):e1000216.

14. Hung WT, Dunlop SM, Perez D, Cotter T. Use and perceived helpfulness of smoking cessation methods: results from a population survey of recent quitters. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:592.

15. Shiffman S, Brockwell SE, Pillitteri JL, Gitchell JG. Use of smoking-cessation treatments in the United States. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(2):102-111.

16. Stead LF, Perera R, Bullen C, et al. Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 Jan 23;(1):CD000146.

17. Robles GI, Singh-Franco D, Ghin HL. A review of the efficacy of smoking-cessation pharmacotherapies in nonwhite populations. Clin Ther. 2008;30(5):800-812.

18. Japuntich SJ, Piper ME, Leventhal AM, et al. The effect of five smoking cessation pharmacotherapies on smoking cessation milestones. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79(1):34-42.

19. Siegel MB, Tanwar KL, Wood KS. Electronic cigarettes as a smoking-cessation tool: results from an online survey. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40 (4):472-475.

20. Tønnesen P, Lauri H, Perfekt R, et al. Efficacy of a nicotine mouth spray in smoking cessation: a randomised, double-blind trial. Eur Respir J. 2012;40(3):548-554.

21. Hartmann-Boyce J, Cahill K, Hatsukami D, Cornuz J. Nicotine vaccines for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Aug 15;8:CD007072.

22. Roddy E. Bupropion and other non-nicotine pharmacotherapies. BMJ. 2004;328(7438):

509-511.

23. Loh WY, Piper ME, Schlam TR, et al. Should all smokers use combination smoking cessation pharmacotherapy? Using novel analytic methods to detect differential treatment effects over 8 weeks of pharmacotherapy. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(2):131-141.

24. Bolt DM, Piper ME, Theobald WE, Baker TB. Why two smoking cessation agents work better than one: role of craving suppression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(1):44-65.

25. McNeil JJ, Piccenna L, Ioannides-Demos LL. Smoking cessation: recent advances. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2010;24(4):359-367.

26. Ebbert JO, Hays JT, Hurt RD. Combination pharmacotherapy for stopping smoking: what advantages does it offer? Drugs. 2010;70(6):643-650.

27. Hajek P, McRobbie HJ, Myers KE, et al. Use of varenicline for 4 weeks before quitting smoking: decrease in ad lib smoking and increase in smoking cessation rates. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171 (8):770-777.

28. Bentz CJ. Review: clonidine is more effective than placebo for long-term smoking cessation, but has side effects. ACP J Club. 2005;142(1):12.

29. Mooney ME, Reus VI, Gorecki J, et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring of nortriptyline in smoking cessation: a multistudy analysis. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;83(3):436-442.

30. White AR, Rampes H, Liu JP, et al. Acupuncture and related interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(1): CD000009.

31. Barnes J, Dong CY, McRobbie H, et al. Hypnotherapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(10):CD001008.

Although smoking prevalence among US adults declined by about 42% between 1965 and 2011, this reduction has slowed in recent years. According to 2010 figures from the CDC, 19.3% of US adults (nearly one in five) remain current smokers,1 despite all the evidence of negative effects that tobacco use and smoke exposure exert on good health.2 Each year, 443,000 premature deaths in the US are attributed to cigarette smoking.3

In the face of these discouraging data, and in ongoing efforts to minimize the deadly effects of cigarette smoking, the US Department of Health and Human Services’ program, Healthy People 2020,4 restated its 10-year goals pertaining to tobacco use as put forth in Healthy People 2010.5 These are to reduce the proportion of Americans who currently smoke to 12%, and to increase the proportion of current smokers who have attempted cessation to 80%.4

Though trained to encourage smoking cessation in their patients, health care providers often lack the knowledge, skills, or resources to support patients through the difficulties of discontinuing tobacco use. Whatever barriers clinicians may face in accessing smoking cessation services, the barriers faced by underserved patients are often greater.6 A heightened awareness of these barriers and improved understanding of common smoking cessation methods will help providers better support their patients who are trying to quit.

ASSESSING READINESS AND MOTIVATING PATIENTS

In 2008, the Public Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services, updated its clinical practice guidelines for clinicians who manage tobacco-dependent patients.7 According to evidence from randomized controlled trials, even brief interventions on the health care provider’s part (such as raising the issue of smoking cessation at each patient visit to determine whether the patient is ready to quit) can prompt the patient to seriously consider smoking abstinence.3,8 Being asked repeatedly can advance a patient’s readiness, and any attempts patients make to quit must be robustly supported.9

The Public Health Service’s five A’s3,7 outline the recommended conversation with patients:

Ask about tobacco use;

Advise tobacco users to quit in strong, clear terms;

Assess readiness for tobacco cessation;

Assist in developing a plan to stop tobacco use; and

Arrange a follow-up consultation to review the patient’s success or to reassess cessation readiness.

Whenever a patient expresses any interest in smoking cessation, it is essential for the clinician to respond with motivation. To help the patient prepare to stop, the clinician must address the five R’s7:

Relevance—the importance of smoking cessation to the patient;

Risks of continuing to smoke, particularly health concerns;

Rewards of smoking cessation, especially alleviation of health complaints;

Roadblocks that contribute to the threat of relapse—but which can be overcome with sufficient motivation; and

Repetition of support and reinforcement for this healthy lifestyle choice, be it from family, friends, coworkers, or the clinician. To prepare for times when support seems to wane, patients should be encouraged to phone 1-800-QUITNOW, a number that will connect the caller to his or her state’s quit line.

Repetition may also imply repeated cessation attempts if the first (or most recent) was unsuccessful. According to findings from a literature review, the reasons smokers relapse are numerous, including cravings (the most common) and withdrawal symptoms, weight gain, stress, and exposure to other smokers.10,11 Interventions based on patients’ given reasons for relapse have no apparent impact on the rate of return to smoking.12 Nevertheless, clinicians must take responsibility to motivate patients and reinforce their successes at every encounter.

UNAIDED CESSATION

In a culture demanding quick results and in the context of ongoing pharmaceutical advertisements and aisles lined with quit-smoking products, it may be easy to dismiss unaided cessation. Options range from gradual cutting down to the abrupt discontinuation of tobacco—going cold turkey. Although little research has been devoted to these strategies,13 unaided cessation is the method patients most often cite in their attempts to quit—and the method successful quitters report as most effective.14,15 The patients most likely to succeed at quitting are those who do not ask for help.

ASSISTED CESSATION

Patients with a significant dependence on nicotine are likely to request assistance with cessation.15 Identifying those who struggle to quit smoking and offering appropriate support may represent the difference between their success and failure.9

Several available tools to support patients’ “quit smoking” efforts, including pharmacologic options (see table7), are described here.

Nicotine Replacement Therapy

Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) is used to reduce nicotine withdrawal symptoms by replacing smoking-produced nicotine with an alternate source of delivery. NRT is currently available in several forms: a transdermal patch, gum, lozenge, or the electronic cigarette. The chance of successful quitting is increased 50% to 70% when NRT is used, compared with patients using placebo.16 While the various forms of NRT share the same goal, they are not equally effective.17

Nicotine transdermal patches have been used in the US since 1991. The patches are used in a stepwise fashion; each patch delivers nicotine at a consistent quantity per hour, and over time, patches with increasingly lower doses of nicotine are substituted. There is some evidence that the patch is more efficacious for maintenance after smoking cessation than for the initial effort to quit.18

Nicotine gum and lozenges, orally absorbed forms of NRT, are used as needed, depending on patients’ withdrawal symptoms. Japuntich et al18 found that these products alone are not beneficial. However, combining bupropion with gum or lozenge therapy was found more effective for patients attempting to stop smoking than either agent alone.18 Lozenges have also been described as increasingly beneficial when combined with a longer-acting NRT, such as a transdermal patch, when cravings increase and rapid delivery of nicotine is required.16

The electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) is a battery-operated device that aerosolizes liquid nicotine, which is then orally absorbed. In a 2011 study, Siegel et al19 found that more than two-thirds of smokers reduced the number of cigarettes smoked after using an e-cigarette. Six months after subjects first purchased e-cigarettes, 31% remained tobacco-abstinent.

Since e-cigarettes are flameless, their use has been suggested in areas where smoking was previously prohibited. This short-acting NRT may benefit a patient when craving is provoked by forced denial of nicotine.

Current research is under way to examine two newer potential NRT tools: a nicotine mouth spray and a nicotine vaccine.20,21 In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, Tønnesen et al20 found that use of a nicotine mouth spray was associated with significantly higher rates of tobacco abstinence at six, 24, and 52 weeks, compared with patients receiving placebo; however, rates of adverse effects were high in both groups (88% and 71%, respectively).

NRT is inexpensive and easily accessible to patients. Since its forms are all available OTC, consultation with health care providers is unnecessary. For patients who have tried to quit smoking unaided and who need short-term or immediate assistance to prevent a smoking relapse, NRT can be a helpful resource.

Bupropion

For smokers who want to quit without using a nicotine-based intervention, the antidepressant bupropion can be a promising smoking cessation aid. It is not clear what mechanism of action helps smokers who take bupropion to stop, although its chemical structure resembles that of diethylpropion, a drug used as an appetite suppressant.22 Bupropion does hinder norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake in the nervous system—opposing an effect of nicotine withdrawal.

Bupropion’s effects as an antidepressant and as a smoking cessation aid do not appear to be related.22 For this reason, even a patient who has not responded to bupropion for treatment of depression may benefit from using it as a smoking cessation aid.

Bupropion may be used alone or with other agents to stop nicotine use. Many study groups report that a combination of medications is more effective than monotherapy, and this is true for combinations that include bupropion.23-26 When used with nicotine lozenges, bupropion has been found effective in preventing a return to tobacco after previous lapses in smoking abstinence. Aside from a nicotine patch, no other monotherapy or combination was effective at achieving this goal.18 Thus, bupropion may be best utilized as a component in combination therapy.

Varenicline

Approved for use in the US in 2006, varenicline is the newest pharmaceutical therapy for smoking cessation. As a partial nicotinic receptor agonist,7 varenicline prevents nicotine from activating the mesolimbic dopamine system, which is associated with pleasure and reward (among other functions). By stimulating the nervous system’s dopamine (though to a lesser extent than nicotine), this agent reduces cravings for tobacco and symptoms of nicotine withdrawal—which are among the greatest barriers to smoking cessation.10 Because of its mechanism of action, varenicline is not often used in combination with NRT.

Varenicline has been shown to be as effective as the combination therapy of bupropion with nicotine lozenges.7,27 UK investigators Hajek et al27 found that using varenicline for four weeks before attempting to stop smoking had minimal effect on smoking urges and withdrawal symptoms, compared with using varenicline for just one week before attempting to quit. However, those who used varenicline for four weeks before stopping smoking were more likely to be smoke-free at 12 weeks than those who had used it for just one week before quitting.27

Other Pharmaceutical Options

Clonidine, long recognized as an effective antihypertensive medication, was determined by Gourlay et al9 in a 2004 review to have potential for use in supporting smoking cessation. Because significant adverse events (including drowsiness, sedation, and postural hypotension) have been associated with clonidine use7,28 and the FDA has not yet approved it for the indication of smoking cessation, its use may be most appropriate as a second-line treatment option, in combination with bupropion or nortriptyline, or for specialists’ use.28 Clonidine should not be discontinued suddenly.

Like bupropion, the tricyclic antidepressant nortriptyline has been investigated for its potential in tobacco cessation therapy. While a significant amount is known about plasma concentrations of nortriptyline needed to treat depression, levels required for effective tobacco cessation are less clear. Mooney et al29 found that therapeutic plasma concentrations of nortriptyline varied among subjects by race and smoking habits; although a lower concentration was usually required to assist smoking cessation than to treat depression, adverse effects were common even at lower concentrations. Thus, it was recommended that nortriptyline be reserved for second-line treatment.

This summer, researchers for the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Review Group published a review of the literature (including phase II and phase III trials conducted by pharmaceutical companies—making the risk for bias “high or unclear”) pertaining to two nicotine vaccines in development.21 In two studies, the level of development of nicotine antibodies was associated with commensurate cessation rates; in two others, the outcome measure (12 months’ abstinence from smoking) was met in 11% of subjects, whether they received the vaccine or placebo. Thus, no strong evidence yet exists that nicotine vaccination supports smoking cessation in the long term; further research is needed.

NONPHARMACEUTICAL

INTERVENTIONS

Acupuncture

Variations and modifications of the traditional Chinese therapy of acupuncture, including acupressure and electrostimulation, have been examined in a number of clinical trials. Despite the supporting rhetoric, objective research of good quality in this area is limited. However, one systematic literature review showed acupuncture to be only slightly more effective than sham interventions and less effective than NRT.30 Insufficient evidence was reported on acupressure and laser stimulation, and acupressure was no more effective than psychological treatments. Considering questionable study quality and other limitations in the currently available research, practitioners should not consider acupuncture or related interventions as first-line options—nor should their potential be dismissed altogether.

Hypnotherapy

Conclusive research findings regarding hypnotherapy as an effective treatment for tobacco dependence are also limited. In 2010, Barnes at al31 reviewed 11 studies comparing hypnotherapy with various alternate methods and found little difference in effectiveness among hypnotherapy, psychological counseling, and rapid smoking therapy. Despite the limitations in these data, however, hypnotherapy may be appropriate for some patients.

CONCLUSION

Tobacco dependence is not the same for any two patients. Just as health care providers do not use the same treatment option for every patient with hypertension or diabetes, treatment for tobacco-dependent patients must also be individualized.

Our professional goal is to care for the health of patients. We clinicians must recommend cessation to our patients who smoke at every encounter—and offer support often. When we miss an opportunity to counsel a patient on the importance of quitting, the patient may interpret our silence as condoning the behavior. Empowering patients with an understanding of the options can contribute to their success—a significant move toward better health.

The authors of Healthy People 2020 hope that 80% of current smokers will have tried to stop smoking by that year. Have 80% of your patients been counseled and offered assistance to stop?

REFERENCES

1. CDC. Current cigarette smoking prevalence among working adults—United States, 2004-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(38):1305-1309.

2. CDC. Vital signs: current cigarette smoking among adults aged ≥ 18 years—United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(35):1135-1140.

3. Jamal A, Dube SR, Malarcher AM, et al; CDC. Tobacco use screening and counseling during physician office visits among adults—National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2005-2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61 suppl: 38-45.

4. US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020 summary of objectives: tobacco use. http://healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/pdfs/TobaccoUse.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2012.

5. US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010 archives. www.healthypeople.gov/2010. Accessed October 18, 2012.

6. Blumenthal DS. Barriers to the provision of smoking cessation services reported by clinicians in underserved communities. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007;20(3):272-279.

7. Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, et al; Public Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services. Clinical practice guideline: treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. www.ahrq.gov/clinic/tobacco/treating_tobacco_use08.pdf. Accessed October 18, 2012.

8. Carson KV, Verbiest ME, Crone MR, et al. Training health professionals in smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 May 16; 5:CD000214.

9. Gourlay SG, Stead LF, Benowitz NL. Clonidine for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD000058.

10. Guirguis AB, Ray SM, Zingone MM, et al. Smoking cessation: barriers to success and readiness to change. Tenn Med. 2010;103(9):45-49.

11. Nørregaard J, Tønnesen P, Petersen L. Predictors and reasons for relapse in smoking cessation with nicotine and placebo patches. Prev Med. 1993;22(2):261-271.

12. Lancaster T, Hajek P, Stead LF, et al. Prevention of relapse after quitting smoking: a systematic review of trials. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(8): 828-835.

13. Chapman S, MacKenzie R. The global research neglect of unassisted smoking cessation: causes and consequences. PLoS Med. 2010;7(2):e1000216.

14. Hung WT, Dunlop SM, Perez D, Cotter T. Use and perceived helpfulness of smoking cessation methods: results from a population survey of recent quitters. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:592.

15. Shiffman S, Brockwell SE, Pillitteri JL, Gitchell JG. Use of smoking-cessation treatments in the United States. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(2):102-111.

16. Stead LF, Perera R, Bullen C, et al. Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 Jan 23;(1):CD000146.

17. Robles GI, Singh-Franco D, Ghin HL. A review of the efficacy of smoking-cessation pharmacotherapies in nonwhite populations. Clin Ther. 2008;30(5):800-812.

18. Japuntich SJ, Piper ME, Leventhal AM, et al. The effect of five smoking cessation pharmacotherapies on smoking cessation milestones. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79(1):34-42.

19. Siegel MB, Tanwar KL, Wood KS. Electronic cigarettes as a smoking-cessation tool: results from an online survey. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40 (4):472-475.

20. Tønnesen P, Lauri H, Perfekt R, et al. Efficacy of a nicotine mouth spray in smoking cessation: a randomised, double-blind trial. Eur Respir J. 2012;40(3):548-554.

21. Hartmann-Boyce J, Cahill K, Hatsukami D, Cornuz J. Nicotine vaccines for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Aug 15;8:CD007072.

22. Roddy E. Bupropion and other non-nicotine pharmacotherapies. BMJ. 2004;328(7438):

509-511.

23. Loh WY, Piper ME, Schlam TR, et al. Should all smokers use combination smoking cessation pharmacotherapy? Using novel analytic methods to detect differential treatment effects over 8 weeks of pharmacotherapy. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(2):131-141.

24. Bolt DM, Piper ME, Theobald WE, Baker TB. Why two smoking cessation agents work better than one: role of craving suppression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(1):44-65.

25. McNeil JJ, Piccenna L, Ioannides-Demos LL. Smoking cessation: recent advances. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2010;24(4):359-367.

26. Ebbert JO, Hays JT, Hurt RD. Combination pharmacotherapy for stopping smoking: what advantages does it offer? Drugs. 2010;70(6):643-650.

27. Hajek P, McRobbie HJ, Myers KE, et al. Use of varenicline for 4 weeks before quitting smoking: decrease in ad lib smoking and increase in smoking cessation rates. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171 (8):770-777.

28. Bentz CJ. Review: clonidine is more effective than placebo for long-term smoking cessation, but has side effects. ACP J Club. 2005;142(1):12.

29. Mooney ME, Reus VI, Gorecki J, et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring of nortriptyline in smoking cessation: a multistudy analysis. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;83(3):436-442.

30. White AR, Rampes H, Liu JP, et al. Acupuncture and related interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(1): CD000009.

31. Barnes J, Dong CY, McRobbie H, et al. Hypnotherapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(10):CD001008.