User login

What's your diagnosis?

Answer to ‘What’s your diagnosis?’: Gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach syndrome.

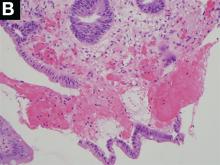

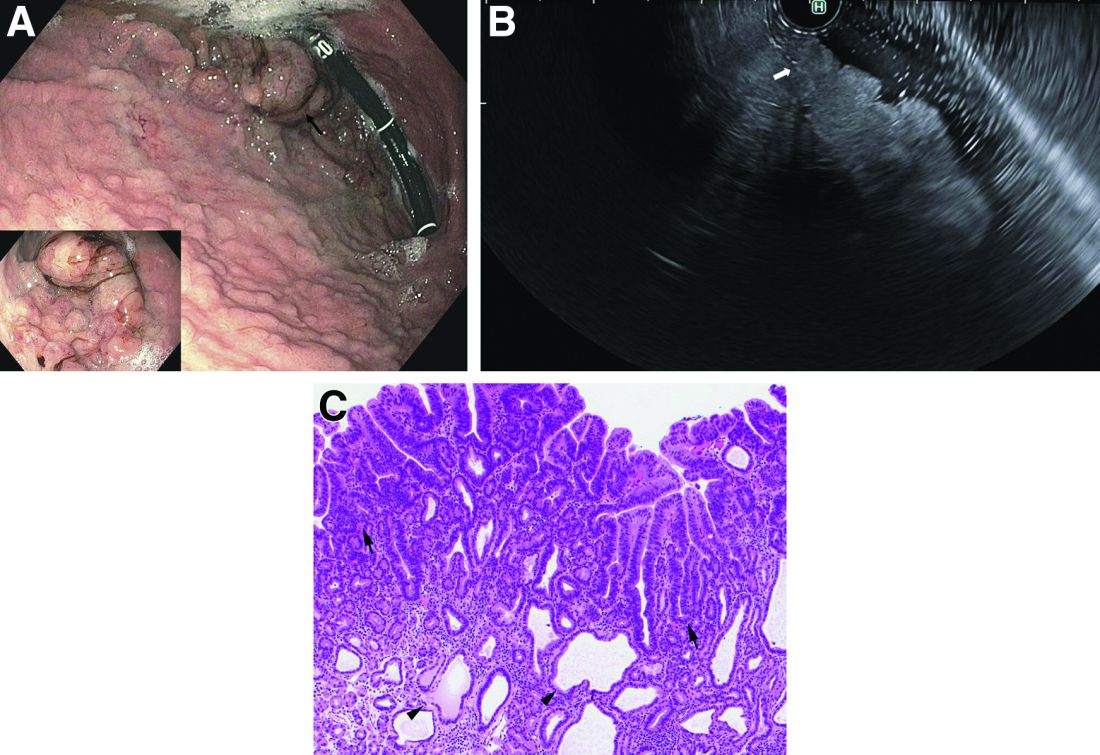

Fundic gland polyps (FGPs) are the most common gastric polyps and when occurring in the sporadic setting are typically benign; however, FGPs that occur in gastrointestinal polyposis syndromes such as familial adenomatosis polyposis can progress to adenocarcinoma and require surveillance. Therefore, it is important to distinguish sporadic versus syndromic fundic gland polyposis. Gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach is a recently described condition that significantly increases the risk of developing invasive gastric adenocarcinoma from FGPs. Diagnostic criteria include (1) gastric polyposis restricted to the body and fundus with no small bowel or colonic involvement, (2) >100 gastric polyps or >30 polyps in a first-degree relative, (3) histology consistent with FGP with areas of dysplasia, (4) a family history consistent with an autosomal-dominant pattern of inheritance, and (5) exclusion of other syndromes and proton pump inhibitor use.1 Unlike familial adenomatosis polyposis, the polyposis is restricted to the oxyntic mucosa of the gastric body and fundus with sparing of the gastric antrum, small bowel, and colon. The genetic basis of the disease has been attributed to a point mutation in the APC gene promotor IB region leading to a loss of tumor suppressor function.2 Typical histology shows large FGPs with areas of low-grade and high-grade dysplasia, as seen in our patient.

There are few data on the natural history of gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach, but effective surveillance is limited by the degree of polyposis. There are multiple reports of hidden adenocarcinoma on surgically resected specimens, as well as rapid progression to metastatic adenocarcinoma despite adequate diagnosis and surveillance.1,3 Therefore, total gastrectomy should be offered to patients who are surgical candidates. Our patient underwent genetic testing that revealed a point mutation in the APC promotor IB. He declined surgical intervention and opted for surveillance endoscopy every 6 months.

References

1. Worthley D.L. et al. Gut. 2012;61:774-9

2. Li J et al. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;98:830-42

3. Rudloff U. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2018;11:447-59

Answer to ‘What’s your diagnosis?’: Gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach syndrome.

Fundic gland polyps (FGPs) are the most common gastric polyps and when occurring in the sporadic setting are typically benign; however, FGPs that occur in gastrointestinal polyposis syndromes such as familial adenomatosis polyposis can progress to adenocarcinoma and require surveillance. Therefore, it is important to distinguish sporadic versus syndromic fundic gland polyposis. Gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach is a recently described condition that significantly increases the risk of developing invasive gastric adenocarcinoma from FGPs. Diagnostic criteria include (1) gastric polyposis restricted to the body and fundus with no small bowel or colonic involvement, (2) >100 gastric polyps or >30 polyps in a first-degree relative, (3) histology consistent with FGP with areas of dysplasia, (4) a family history consistent with an autosomal-dominant pattern of inheritance, and (5) exclusion of other syndromes and proton pump inhibitor use.1 Unlike familial adenomatosis polyposis, the polyposis is restricted to the oxyntic mucosa of the gastric body and fundus with sparing of the gastric antrum, small bowel, and colon. The genetic basis of the disease has been attributed to a point mutation in the APC gene promotor IB region leading to a loss of tumor suppressor function.2 Typical histology shows large FGPs with areas of low-grade and high-grade dysplasia, as seen in our patient.

There are few data on the natural history of gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach, but effective surveillance is limited by the degree of polyposis. There are multiple reports of hidden adenocarcinoma on surgically resected specimens, as well as rapid progression to metastatic adenocarcinoma despite adequate diagnosis and surveillance.1,3 Therefore, total gastrectomy should be offered to patients who are surgical candidates. Our patient underwent genetic testing that revealed a point mutation in the APC promotor IB. He declined surgical intervention and opted for surveillance endoscopy every 6 months.

References

1. Worthley D.L. et al. Gut. 2012;61:774-9

2. Li J et al. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;98:830-42

3. Rudloff U. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2018;11:447-59

Answer to ‘What’s your diagnosis?’: Gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach syndrome.

Fundic gland polyps (FGPs) are the most common gastric polyps and when occurring in the sporadic setting are typically benign; however, FGPs that occur in gastrointestinal polyposis syndromes such as familial adenomatosis polyposis can progress to adenocarcinoma and require surveillance. Therefore, it is important to distinguish sporadic versus syndromic fundic gland polyposis. Gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach is a recently described condition that significantly increases the risk of developing invasive gastric adenocarcinoma from FGPs. Diagnostic criteria include (1) gastric polyposis restricted to the body and fundus with no small bowel or colonic involvement, (2) >100 gastric polyps or >30 polyps in a first-degree relative, (3) histology consistent with FGP with areas of dysplasia, (4) a family history consistent with an autosomal-dominant pattern of inheritance, and (5) exclusion of other syndromes and proton pump inhibitor use.1 Unlike familial adenomatosis polyposis, the polyposis is restricted to the oxyntic mucosa of the gastric body and fundus with sparing of the gastric antrum, small bowel, and colon. The genetic basis of the disease has been attributed to a point mutation in the APC gene promotor IB region leading to a loss of tumor suppressor function.2 Typical histology shows large FGPs with areas of low-grade and high-grade dysplasia, as seen in our patient.

There are few data on the natural history of gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach, but effective surveillance is limited by the degree of polyposis. There are multiple reports of hidden adenocarcinoma on surgically resected specimens, as well as rapid progression to metastatic adenocarcinoma despite adequate diagnosis and surveillance.1,3 Therefore, total gastrectomy should be offered to patients who are surgical candidates. Our patient underwent genetic testing that revealed a point mutation in the APC promotor IB. He declined surgical intervention and opted for surveillance endoscopy every 6 months.

References

1. Worthley D.L. et al. Gut. 2012;61:774-9

2. Li J et al. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;98:830-42

3. Rudloff U. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2018;11:447-59

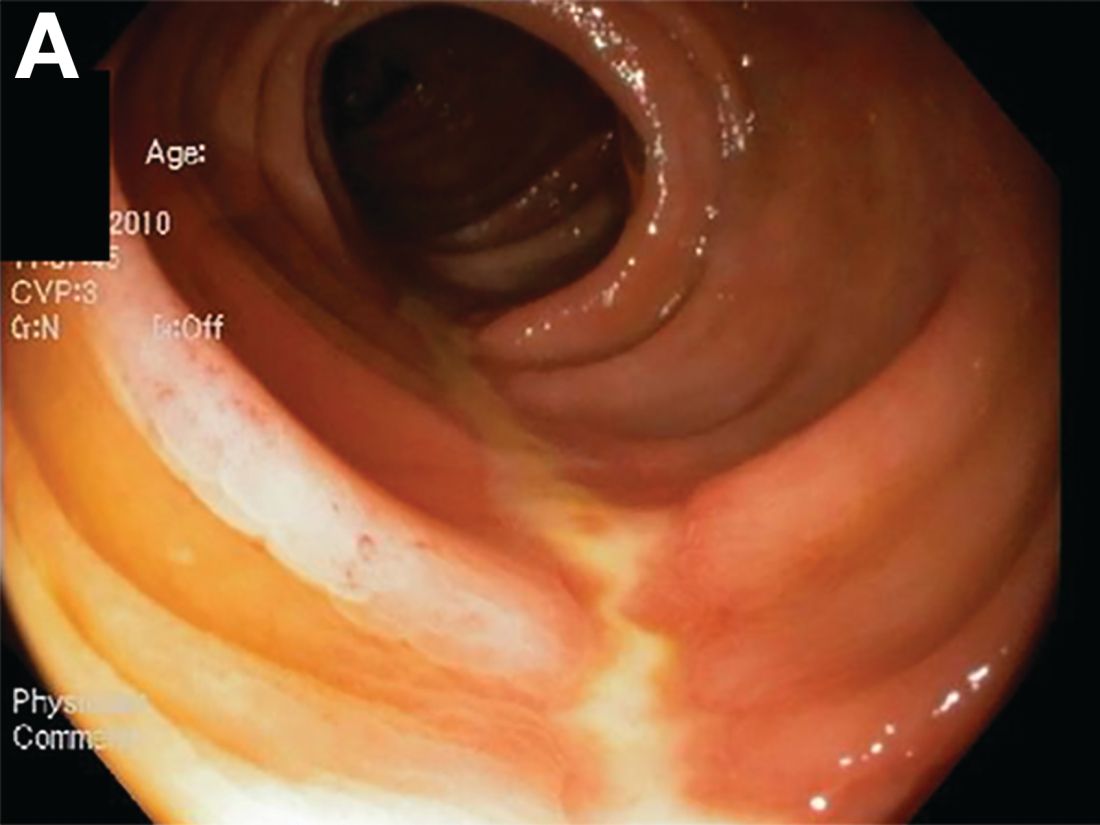

A 72-year-old man with compensated cirrhosis owing to autoimmune hepatitis presented for evaluation of an indeterminate gastric lesion found during an otherwise normal endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography performed for incidental ductal dilation seen on cross-sectional imaging. He did not endorse any abdominal pain, dyspepsia, or weight loss and was not on a proton pump inhibitor. Family history was notable for a daughter diagnosed with metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma at the age of 44 years.

Upper endoscopy showed innumerable sessile polyps of variable size carpeting the gastric body and fundus (Figure A) with a large, mound-like mass lesion in the fundus (Figure A, arrow and inset). Echoendoscopy revealed a hypoechoic, noncircumferential mass restricted to the mucosal surface with well-defined borders (Figure B, arrow). A technically challenging, piecemeal endoscopic mucosal resection was performed. The patient also underwent a colonoscopy that was unremarkable. Pathology of the gastric lesion was consistent with a fundic gland polyp (Figure C, arrowheads) containing low-grade and high-grade dysplasia (Figure C, arrows).

What is the most likely diagnosis?

What is your diagnosis? - December 2018

Cecal carcinoma–associated paraneoplastic Sweet’s syndrome

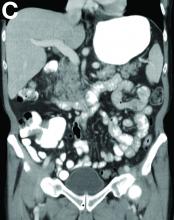

Based on the tomographic appearance of an “apple core”–like lesion in the right lower quadrant, the patient was referred for colonoscopy, which revealed a malignant-appearing cecal mass (Figure D), with biopsies confirming adenocarcinoma; despite these findings, no bowel-related symptoms were reported. The patient underwent laparoscopic right hemicolectomy, after which the skin lesions began to resolve, and corticosteroids were successfully tapered. The overall presentation was consistent with Sweet’s syndrome, with a paraneoplastic etiology being favored given the clinical scenario, including absence of alternative etiologies and dependence on corticosteroids for control of skin disease until resection of the underlying malignancy was performed.

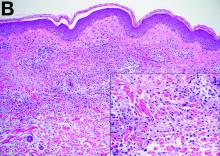

Sweet’s syndrome was first described in a case series of eight patients published in 1964 by the English dermatologist Dr. Robert Douglas Sweet.1,2 Sweet’s syndrome is characterized by fever, neutrophilia, and sterile erythematous plaques or nodules, which most commonly involve the upper extremities and face and respond to corticosteroid therapy. It may be malignancy associated, drug induced, autoimmune disease related, or idiopathic.2,3 The pathogenesis of Sweet’s syndrome is unclear, but T-lymphocyte, neutrophil chemotaxis, and cytokine (e.g., interleukin-6 and granulocyte colony–stimulating factor) abnormalities have been suggested.2 Diagnosis is based on the clinical presentation and context together with typical dermatopathologic findings, including a dense neutrophilic infiltrate. Skin lesions may be phasic, but persist typically until appropriate therapy (e.g., corticosteroids, chemotherapy) is administered or the offending drug removed. Malignancy-associated (i.e., paraneoplastic) Sweet’s syndrome accounts for approximately 20% of all cases; these primarily involve hematologic malignancies, most commonly leukemia, but adenocarcinomata have also been implicated.3 Recurrence of Sweet’s syndrome can occur and often heralds relapse of the underlying disease.

References

1. Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:349-56.

2. Von den Driesch P. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:535-56.

3. Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome–a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

Cecal carcinoma–associated paraneoplastic Sweet’s syndrome

Based on the tomographic appearance of an “apple core”–like lesion in the right lower quadrant, the patient was referred for colonoscopy, which revealed a malignant-appearing cecal mass (Figure D), with biopsies confirming adenocarcinoma; despite these findings, no bowel-related symptoms were reported. The patient underwent laparoscopic right hemicolectomy, after which the skin lesions began to resolve, and corticosteroids were successfully tapered. The overall presentation was consistent with Sweet’s syndrome, with a paraneoplastic etiology being favored given the clinical scenario, including absence of alternative etiologies and dependence on corticosteroids for control of skin disease until resection of the underlying malignancy was performed.

Sweet’s syndrome was first described in a case series of eight patients published in 1964 by the English dermatologist Dr. Robert Douglas Sweet.1,2 Sweet’s syndrome is characterized by fever, neutrophilia, and sterile erythematous plaques or nodules, which most commonly involve the upper extremities and face and respond to corticosteroid therapy. It may be malignancy associated, drug induced, autoimmune disease related, or idiopathic.2,3 The pathogenesis of Sweet’s syndrome is unclear, but T-lymphocyte, neutrophil chemotaxis, and cytokine (e.g., interleukin-6 and granulocyte colony–stimulating factor) abnormalities have been suggested.2 Diagnosis is based on the clinical presentation and context together with typical dermatopathologic findings, including a dense neutrophilic infiltrate. Skin lesions may be phasic, but persist typically until appropriate therapy (e.g., corticosteroids, chemotherapy) is administered or the offending drug removed. Malignancy-associated (i.e., paraneoplastic) Sweet’s syndrome accounts for approximately 20% of all cases; these primarily involve hematologic malignancies, most commonly leukemia, but adenocarcinomata have also been implicated.3 Recurrence of Sweet’s syndrome can occur and often heralds relapse of the underlying disease.

References

1. Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:349-56.

2. Von den Driesch P. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:535-56.

3. Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome–a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

Cecal carcinoma–associated paraneoplastic Sweet’s syndrome

Based on the tomographic appearance of an “apple core”–like lesion in the right lower quadrant, the patient was referred for colonoscopy, which revealed a malignant-appearing cecal mass (Figure D), with biopsies confirming adenocarcinoma; despite these findings, no bowel-related symptoms were reported. The patient underwent laparoscopic right hemicolectomy, after which the skin lesions began to resolve, and corticosteroids were successfully tapered. The overall presentation was consistent with Sweet’s syndrome, with a paraneoplastic etiology being favored given the clinical scenario, including absence of alternative etiologies and dependence on corticosteroids for control of skin disease until resection of the underlying malignancy was performed.

Sweet’s syndrome was first described in a case series of eight patients published in 1964 by the English dermatologist Dr. Robert Douglas Sweet.1,2 Sweet’s syndrome is characterized by fever, neutrophilia, and sterile erythematous plaques or nodules, which most commonly involve the upper extremities and face and respond to corticosteroid therapy. It may be malignancy associated, drug induced, autoimmune disease related, or idiopathic.2,3 The pathogenesis of Sweet’s syndrome is unclear, but T-lymphocyte, neutrophil chemotaxis, and cytokine (e.g., interleukin-6 and granulocyte colony–stimulating factor) abnormalities have been suggested.2 Diagnosis is based on the clinical presentation and context together with typical dermatopathologic findings, including a dense neutrophilic infiltrate. Skin lesions may be phasic, but persist typically until appropriate therapy (e.g., corticosteroids, chemotherapy) is administered or the offending drug removed. Malignancy-associated (i.e., paraneoplastic) Sweet’s syndrome accounts for approximately 20% of all cases; these primarily involve hematologic malignancies, most commonly leukemia, but adenocarcinomata have also been implicated.3 Recurrence of Sweet’s syndrome can occur and often heralds relapse of the underlying disease.

References

1. Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:349-56.

2. Von den Driesch P. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:535-56.

3. Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome–a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

What is the diagnosis?

A Rare Endoscopic Clue to a Common Clinical Condition

The correct answer is C: colonic ischemia.

References

1. Zuckerman G.R., et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2018-22.

2. Tanapanpanit O., Pongpirul K. BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Sept. 17;2015.

This article has an accompanying continuing medical education activity, also eligible for MOC credit (see gastrojournal.org for details). Learning Objective: Upon completion of this activity, successful learners will be able to recognize colon single-stripe sign as an endoscopic feature of colonic ischemia.

The correct answer is C: colonic ischemia.

References

1. Zuckerman G.R., et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2018-22.

2. Tanapanpanit O., Pongpirul K. BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Sept. 17;2015.

This article has an accompanying continuing medical education activity, also eligible for MOC credit (see gastrojournal.org for details). Learning Objective: Upon completion of this activity, successful learners will be able to recognize colon single-stripe sign as an endoscopic feature of colonic ischemia.

The correct answer is C: colonic ischemia.

References

1. Zuckerman G.R., et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2018-22.

2. Tanapanpanit O., Pongpirul K. BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Sept. 17;2015.

This article has an accompanying continuing medical education activity, also eligible for MOC credit (see gastrojournal.org for details). Learning Objective: Upon completion of this activity, successful learners will be able to recognize colon single-stripe sign as an endoscopic feature of colonic ischemia.

Published previously in Gastroenterology (2017;152:492-3)

Dr. Anderson and Dr. Sweetser are in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minn.