User login

Parity for prompt and staged STEMI complete revascularization: MULTISTARS-AMI

The conclusion comes from a randomized outcomes trial of 840 patients that compared prompt same-session CR with a staged procedure carried out weeks later.

That CR is a worthy goal in such cases is largely settled, unlike the question of when to pursue revascularization of nonculprit lesions for best results. So the timing varies in practice, often depending on the patient’s clinical stability, risk status, or practical issues like cath lab resources or personnel.

The new trial, MULTISTARS-AMI, supports that kind of flexibility as safe in practice. Immediate, same-session CR led to a 48% drop in risk for a broad composite primary endpoint at 1 year, compared with staged CR an average of 37 days later. The finding was significant for noninferiority in the study’s primary analysis and secondarily, was significant for superiority (P < .001 in both cases).

The composite endpoint included death from any cause, MI, stroke, unplanned ischemia-driven revascularization, or heart failure (HF) hospitalization.

CR’s immediate effect on outcomes was numerically pronounced, but because it was prespecified as a noninferiority trial, MULTISTARS-AMI could show only that the strategy is comparable to staged CR, emphasized Barbara E. Stähli, MD, MPH, MBA, at a press conference.

Still, it appears to be the first trial of its kind to show that operators and patients can safely choose either percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) approach and attain similar outcomes, said Dr. Stähli, University Hospital Zurich, MULTISTARS-AMI’s principal investigator.

Not only were the two approaches similar with respect to safety, she noted, but immediate CR seemed to require less use of contrast agent and fluoroscopy. “And you have only one procedure, so there’s only one arterial puncture.”

Dr. Stähli formally presented MULTISTARS-AMI at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, held in Amsterdam. She is also lead author on its publication in the New England Journal of Medicine.

After her presentation, invited discussant Robert A. Byrne, PhD, MD, MB, BCh, said that the trial’s central message is that STEMI patients with MVD having primary PCI “should undergo complete revascularization within the first 45 days, with the timing of the non–infarct-related artery procedure individualized according to clinical risk and logistical considerations.”

Still, the trial “provides evidence, but not strong evidence, of benefits with routine immediate PCI during the index procedure as compared with staged outpatient PCI,” said Dr. Byrne, Mater Private Hospital and RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences, Dublin.

MULTISTARS-AMI randomly assigned patients at 37 European sites to undergo same-session CR (418 patients) or CR staged 19-45 days later (422 patients).

Rates for the primary endpoint at 1 year were 8.5% and 16.3%, respectively, for a risk ratio of 0.52 (95% confidence interval, 0.38-0.72). The difference was driven by fewer instances of nonfatal MI, 0.36 (95% CI, 0.16-0.80), and unplanned ischemia-driven revascularization, 0.42 (95% CI, 0.24-0.74), in the immediate-CR group.

The wee hours

Sunil V. Rao, MD, director of interventional cardiology at NYU Langone Health System, New York, said that, in general at his center, patients who are stable with a good primary PCI outcome and whose lesions aren’t very high risk are often discharged to return later for the staged CR procedure.

But after the new insights from MULTISTARS-AMI, Dr. Rao, who is not connected to the study, said in an interview that immediate same-session CR is indeed likely preferable to staged CR performed weeks later.

Same-session CR, however, may not always be practical or wise, he observed. For example, some patients with STEMI can be pretty sick with MVD that involves very complex lesions that might be better handled later.

“The wee hours of the night may not be the best time to tackle such complex lesions,” Dr. Rao observed. If confronted with, for example, a bifurcation that requires a complex procedure, “2 o’clock in the morning is probably not the best time to address something like that.”

So the trial’s more realistic translational message, he proposed, may be to perform CR after the primary PCI but during the same hospitalization, “unless there are some real mitigating circumstances.”

The trial was supported by Boston Scientific. Dr. Stähli had no disclosures. Dr. Byrne discloses research funding to his institution from Abbott Vascular, Translumina, Biosensors, and Boston Scientific. Dr. Rao had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The conclusion comes from a randomized outcomes trial of 840 patients that compared prompt same-session CR with a staged procedure carried out weeks later.

That CR is a worthy goal in such cases is largely settled, unlike the question of when to pursue revascularization of nonculprit lesions for best results. So the timing varies in practice, often depending on the patient’s clinical stability, risk status, or practical issues like cath lab resources or personnel.

The new trial, MULTISTARS-AMI, supports that kind of flexibility as safe in practice. Immediate, same-session CR led to a 48% drop in risk for a broad composite primary endpoint at 1 year, compared with staged CR an average of 37 days later. The finding was significant for noninferiority in the study’s primary analysis and secondarily, was significant for superiority (P < .001 in both cases).

The composite endpoint included death from any cause, MI, stroke, unplanned ischemia-driven revascularization, or heart failure (HF) hospitalization.

CR’s immediate effect on outcomes was numerically pronounced, but because it was prespecified as a noninferiority trial, MULTISTARS-AMI could show only that the strategy is comparable to staged CR, emphasized Barbara E. Stähli, MD, MPH, MBA, at a press conference.

Still, it appears to be the first trial of its kind to show that operators and patients can safely choose either percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) approach and attain similar outcomes, said Dr. Stähli, University Hospital Zurich, MULTISTARS-AMI’s principal investigator.

Not only were the two approaches similar with respect to safety, she noted, but immediate CR seemed to require less use of contrast agent and fluoroscopy. “And you have only one procedure, so there’s only one arterial puncture.”

Dr. Stähli formally presented MULTISTARS-AMI at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, held in Amsterdam. She is also lead author on its publication in the New England Journal of Medicine.

After her presentation, invited discussant Robert A. Byrne, PhD, MD, MB, BCh, said that the trial’s central message is that STEMI patients with MVD having primary PCI “should undergo complete revascularization within the first 45 days, with the timing of the non–infarct-related artery procedure individualized according to clinical risk and logistical considerations.”

Still, the trial “provides evidence, but not strong evidence, of benefits with routine immediate PCI during the index procedure as compared with staged outpatient PCI,” said Dr. Byrne, Mater Private Hospital and RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences, Dublin.

MULTISTARS-AMI randomly assigned patients at 37 European sites to undergo same-session CR (418 patients) or CR staged 19-45 days later (422 patients).

Rates for the primary endpoint at 1 year were 8.5% and 16.3%, respectively, for a risk ratio of 0.52 (95% confidence interval, 0.38-0.72). The difference was driven by fewer instances of nonfatal MI, 0.36 (95% CI, 0.16-0.80), and unplanned ischemia-driven revascularization, 0.42 (95% CI, 0.24-0.74), in the immediate-CR group.

The wee hours

Sunil V. Rao, MD, director of interventional cardiology at NYU Langone Health System, New York, said that, in general at his center, patients who are stable with a good primary PCI outcome and whose lesions aren’t very high risk are often discharged to return later for the staged CR procedure.

But after the new insights from MULTISTARS-AMI, Dr. Rao, who is not connected to the study, said in an interview that immediate same-session CR is indeed likely preferable to staged CR performed weeks later.

Same-session CR, however, may not always be practical or wise, he observed. For example, some patients with STEMI can be pretty sick with MVD that involves very complex lesions that might be better handled later.

“The wee hours of the night may not be the best time to tackle such complex lesions,” Dr. Rao observed. If confronted with, for example, a bifurcation that requires a complex procedure, “2 o’clock in the morning is probably not the best time to address something like that.”

So the trial’s more realistic translational message, he proposed, may be to perform CR after the primary PCI but during the same hospitalization, “unless there are some real mitigating circumstances.”

The trial was supported by Boston Scientific. Dr. Stähli had no disclosures. Dr. Byrne discloses research funding to his institution from Abbott Vascular, Translumina, Biosensors, and Boston Scientific. Dr. Rao had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The conclusion comes from a randomized outcomes trial of 840 patients that compared prompt same-session CR with a staged procedure carried out weeks later.

That CR is a worthy goal in such cases is largely settled, unlike the question of when to pursue revascularization of nonculprit lesions for best results. So the timing varies in practice, often depending on the patient’s clinical stability, risk status, or practical issues like cath lab resources or personnel.

The new trial, MULTISTARS-AMI, supports that kind of flexibility as safe in practice. Immediate, same-session CR led to a 48% drop in risk for a broad composite primary endpoint at 1 year, compared with staged CR an average of 37 days later. The finding was significant for noninferiority in the study’s primary analysis and secondarily, was significant for superiority (P < .001 in both cases).

The composite endpoint included death from any cause, MI, stroke, unplanned ischemia-driven revascularization, or heart failure (HF) hospitalization.

CR’s immediate effect on outcomes was numerically pronounced, but because it was prespecified as a noninferiority trial, MULTISTARS-AMI could show only that the strategy is comparable to staged CR, emphasized Barbara E. Stähli, MD, MPH, MBA, at a press conference.

Still, it appears to be the first trial of its kind to show that operators and patients can safely choose either percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) approach and attain similar outcomes, said Dr. Stähli, University Hospital Zurich, MULTISTARS-AMI’s principal investigator.

Not only were the two approaches similar with respect to safety, she noted, but immediate CR seemed to require less use of contrast agent and fluoroscopy. “And you have only one procedure, so there’s only one arterial puncture.”

Dr. Stähli formally presented MULTISTARS-AMI at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, held in Amsterdam. She is also lead author on its publication in the New England Journal of Medicine.

After her presentation, invited discussant Robert A. Byrne, PhD, MD, MB, BCh, said that the trial’s central message is that STEMI patients with MVD having primary PCI “should undergo complete revascularization within the first 45 days, with the timing of the non–infarct-related artery procedure individualized according to clinical risk and logistical considerations.”

Still, the trial “provides evidence, but not strong evidence, of benefits with routine immediate PCI during the index procedure as compared with staged outpatient PCI,” said Dr. Byrne, Mater Private Hospital and RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences, Dublin.

MULTISTARS-AMI randomly assigned patients at 37 European sites to undergo same-session CR (418 patients) or CR staged 19-45 days later (422 patients).

Rates for the primary endpoint at 1 year were 8.5% and 16.3%, respectively, for a risk ratio of 0.52 (95% confidence interval, 0.38-0.72). The difference was driven by fewer instances of nonfatal MI, 0.36 (95% CI, 0.16-0.80), and unplanned ischemia-driven revascularization, 0.42 (95% CI, 0.24-0.74), in the immediate-CR group.

The wee hours

Sunil V. Rao, MD, director of interventional cardiology at NYU Langone Health System, New York, said that, in general at his center, patients who are stable with a good primary PCI outcome and whose lesions aren’t very high risk are often discharged to return later for the staged CR procedure.

But after the new insights from MULTISTARS-AMI, Dr. Rao, who is not connected to the study, said in an interview that immediate same-session CR is indeed likely preferable to staged CR performed weeks later.

Same-session CR, however, may not always be practical or wise, he observed. For example, some patients with STEMI can be pretty sick with MVD that involves very complex lesions that might be better handled later.

“The wee hours of the night may not be the best time to tackle such complex lesions,” Dr. Rao observed. If confronted with, for example, a bifurcation that requires a complex procedure, “2 o’clock in the morning is probably not the best time to address something like that.”

So the trial’s more realistic translational message, he proposed, may be to perform CR after the primary PCI but during the same hospitalization, “unless there are some real mitigating circumstances.”

The trial was supported by Boston Scientific. Dr. Stähli had no disclosures. Dr. Byrne discloses research funding to his institution from Abbott Vascular, Translumina, Biosensors, and Boston Scientific. Dr. Rao had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ESC CONGRESS 2023

Advanced HF no obstacle to AFib ablation success: CASTLE-HTx

Catheter ablation had long taken atrial fibrillation (AF) rhythm control to the next level before clinical trials showed it could help keep AF patients with heart failure (HF) alive and out of the hospital.

But those trials didn’t include many patients with AF on top of advanced or even end-stage HF. Lacking much of an evidence base and often viewed as too sick to gain a lot from the procedure, patients with AF and advanced HF aren’t offered ablation very often.

Now a randomized trial suggests that, on the contrary, AF ablation may confer a similar benefit to patients with HF so advanced that they were referred for evaluation at a transplant center.

The study, modestly sized with fewer than 200 such patients and conducted at a single center, assigned half of them to receive ablation and the other half to continued medical management.

Risk for the composite primary endpoint plunged 76% over a median of 18 months for those who underwent ablation. The outcome comprised death from any cause, implantation of a left ventricular assist device (LVAD), or urgent heart transplantation.

The advantage for ablation emerged early enough that the trial, CASTLE-HTx, was halted for benefit only a year after reaching its planned enrollment, observed Christian Sohns, MD, when formally presenting the results in Amsterdam at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The difference in the primary endpoint “in this severely sick cohort of advanced, end-stage heart failure patients,” he said, was driven mostly by fewer deaths, especially cardiovascular deaths, in the ablation group.

Ablation’s effect on outcomes was associated, perhaps causally, with significant gains in left ventricular (LV) function and more than triple the reduction in AF burden seen in the control group, noted Dr. Sohns, from the Heart and Diabetes Center North-Rhine Westphalia, Bad Oeynhausen, Germany.

states the CASTLE-HTx primary report, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, with Dr. Sohns as lead author, in tandem with his ESC presentation.

One of the study’s key messages “is that AF ablation is safe and effective in patients with end-stage heart failure” and “should be part of our armamentarium” for treating them, said Philipp Sommer, MD, also with Heart and Diabetes Center North-Rhine Westphalia, at a press conference preceding Dr. Sohns’ presentation of CASTLE-HTx.

The intervention could potentially help such patients survive longer on transplant wait lists and even delay need for the surgery, proposed Dr. Sommer, who is senior author on the trial’s publication.

CASTLE-HTx suggests that patients with advanced HF and even persistent AF, “if they have reasonably small atria, should be actually considered for ablation, as it may prevent the need for heart transplant or LVAD implant,” said invited discussant Finn Gustafsson, MD, PhD, DMSc, after Dr. Sohns’ presentation. “And that, of course, would be a huge achievement.”

The trial “should, if anything, help eradicate the current somewhat nihilistic approach to atrial fibrillation management in patients with advanced heart failure,” said Dr. Gustafsson, medical director of cardiac transplantation and mechanical circulatory support, Rigshopsitalet Copenhagen University Hospital.

Still, he disputed the characterization by the investigators and indeed the published report that the patients, or most of them, had “end-stage heart failure.”

For example, about a third of the trial’s patients started out in NYHA class 2, Dr. Gustafsson noted. Not that they weren’t “high-risk” or their HF wasn’t severe, he offered, but they don’t seem to have been “a truly advanced heart failure population.”

The trial population consisted of “patients referred to an advanced heart failure center, rather than patients with advanced heart failure,” agreed Mandeep R. Mehra, MD, director of the Center for Advanced Heart Disease at Brigham and Woman’s Hospital, Boston.

Also citing a large prevalence of patients in NYHA class-2, Dr. Mehra added that “we almost never see paroxysmal atrial fib in these patients. It’s usually an early-stage phenomenon.” In advanced HF, AF “is usually permanent,” he told this news organization. Yet it was paroxysmal in about 30% of cases.

To its credit, Dr. Mehra observed, the study does assert that advanced HF is no reason, necessarily, to avoid catheter ablation. Nor should an AF patient’s referral to an advanced-HF center “mean that you should rush to an LVAD or transplant” before considering ablation.

The study seems to be saying, “please exhaust all options before you biologically replace the heart or put in an LVAD,” Dr. Mehra said. “Certainly, this paper steers you in that direction.”

The trial entered 194 patients with symptomatic AF and HF of at least NYHA class 2, with impaired functional capacity by the 6-minute walk test, who had been referred to a major center in Germany for a heart-transplantation workup. With all on guideline-directed medical therapy, 97 were randomly assigned open-label to catheter ablation and 97 to continued standard care.

Catheter ablation was actually carried out in 81 patients (84%) who had been assigned to it and in 16 (16%) of those in the control group, the report states.

A total of 8 in the ablation group and 29 in the control arm died, received an LVAD, or went to urgent transplantation, for a hazard ratio of 0.24 (95% confidence interval, 0.11-0.52; P < .001) for the primary endpoint.

Death from any cause apparently played a big role in the risk reduction; its HR was 0.29 (95% CI, 0.12-0.72).

One peculiarity of the data, Dr. Mehra said, is that event curves for the primary endpoint and its individual components “diverge almost from day 1.” That would mean the ablation group right away started having fewer deaths, LVAD placements, or heart transplants than the control group.

“It is surprising to see such a large effect size on endpoints that are very much dependent on operators and diverge within the first day.” Probably, Dr. Mehra said, “it has to do with this being a single-center study that may not be generalizable to other practices.”

CASTLE HTx was supported by a grant from Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung. Dr. Sommer discloses consulting for Abbott, Biosense Webster, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic. Dr. Sohns reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Gustafsson discloses receiving honoraria or fees for consulting from Abbott, Alnylam Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Ionis, Novartis, and Pfizer; serving on a speakers bureau for Astra Zeneca and Orion; and receiving grants from Corvia Research. Dr. Mehra has reported receiving payments to his institution from Abbott for consulting; consulting fees from Janssen, Mesoblast, Broadview Ventures, Natera, Paragonix, Moderna, and the Baim Institute for Clinical Research; and serving on a scientific advisory board for NuPulseCV, Leviticus, and FineHeart.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Catheter ablation had long taken atrial fibrillation (AF) rhythm control to the next level before clinical trials showed it could help keep AF patients with heart failure (HF) alive and out of the hospital.

But those trials didn’t include many patients with AF on top of advanced or even end-stage HF. Lacking much of an evidence base and often viewed as too sick to gain a lot from the procedure, patients with AF and advanced HF aren’t offered ablation very often.

Now a randomized trial suggests that, on the contrary, AF ablation may confer a similar benefit to patients with HF so advanced that they were referred for evaluation at a transplant center.

The study, modestly sized with fewer than 200 such patients and conducted at a single center, assigned half of them to receive ablation and the other half to continued medical management.

Risk for the composite primary endpoint plunged 76% over a median of 18 months for those who underwent ablation. The outcome comprised death from any cause, implantation of a left ventricular assist device (LVAD), or urgent heart transplantation.

The advantage for ablation emerged early enough that the trial, CASTLE-HTx, was halted for benefit only a year after reaching its planned enrollment, observed Christian Sohns, MD, when formally presenting the results in Amsterdam at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The difference in the primary endpoint “in this severely sick cohort of advanced, end-stage heart failure patients,” he said, was driven mostly by fewer deaths, especially cardiovascular deaths, in the ablation group.

Ablation’s effect on outcomes was associated, perhaps causally, with significant gains in left ventricular (LV) function and more than triple the reduction in AF burden seen in the control group, noted Dr. Sohns, from the Heart and Diabetes Center North-Rhine Westphalia, Bad Oeynhausen, Germany.

states the CASTLE-HTx primary report, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, with Dr. Sohns as lead author, in tandem with his ESC presentation.

One of the study’s key messages “is that AF ablation is safe and effective in patients with end-stage heart failure” and “should be part of our armamentarium” for treating them, said Philipp Sommer, MD, also with Heart and Diabetes Center North-Rhine Westphalia, at a press conference preceding Dr. Sohns’ presentation of CASTLE-HTx.

The intervention could potentially help such patients survive longer on transplant wait lists and even delay need for the surgery, proposed Dr. Sommer, who is senior author on the trial’s publication.

CASTLE-HTx suggests that patients with advanced HF and even persistent AF, “if they have reasonably small atria, should be actually considered for ablation, as it may prevent the need for heart transplant or LVAD implant,” said invited discussant Finn Gustafsson, MD, PhD, DMSc, after Dr. Sohns’ presentation. “And that, of course, would be a huge achievement.”

The trial “should, if anything, help eradicate the current somewhat nihilistic approach to atrial fibrillation management in patients with advanced heart failure,” said Dr. Gustafsson, medical director of cardiac transplantation and mechanical circulatory support, Rigshopsitalet Copenhagen University Hospital.

Still, he disputed the characterization by the investigators and indeed the published report that the patients, or most of them, had “end-stage heart failure.”

For example, about a third of the trial’s patients started out in NYHA class 2, Dr. Gustafsson noted. Not that they weren’t “high-risk” or their HF wasn’t severe, he offered, but they don’t seem to have been “a truly advanced heart failure population.”

The trial population consisted of “patients referred to an advanced heart failure center, rather than patients with advanced heart failure,” agreed Mandeep R. Mehra, MD, director of the Center for Advanced Heart Disease at Brigham and Woman’s Hospital, Boston.

Also citing a large prevalence of patients in NYHA class-2, Dr. Mehra added that “we almost never see paroxysmal atrial fib in these patients. It’s usually an early-stage phenomenon.” In advanced HF, AF “is usually permanent,” he told this news organization. Yet it was paroxysmal in about 30% of cases.

To its credit, Dr. Mehra observed, the study does assert that advanced HF is no reason, necessarily, to avoid catheter ablation. Nor should an AF patient’s referral to an advanced-HF center “mean that you should rush to an LVAD or transplant” before considering ablation.

The study seems to be saying, “please exhaust all options before you biologically replace the heart or put in an LVAD,” Dr. Mehra said. “Certainly, this paper steers you in that direction.”

The trial entered 194 patients with symptomatic AF and HF of at least NYHA class 2, with impaired functional capacity by the 6-minute walk test, who had been referred to a major center in Germany for a heart-transplantation workup. With all on guideline-directed medical therapy, 97 were randomly assigned open-label to catheter ablation and 97 to continued standard care.

Catheter ablation was actually carried out in 81 patients (84%) who had been assigned to it and in 16 (16%) of those in the control group, the report states.

A total of 8 in the ablation group and 29 in the control arm died, received an LVAD, or went to urgent transplantation, for a hazard ratio of 0.24 (95% confidence interval, 0.11-0.52; P < .001) for the primary endpoint.

Death from any cause apparently played a big role in the risk reduction; its HR was 0.29 (95% CI, 0.12-0.72).

One peculiarity of the data, Dr. Mehra said, is that event curves for the primary endpoint and its individual components “diverge almost from day 1.” That would mean the ablation group right away started having fewer deaths, LVAD placements, or heart transplants than the control group.

“It is surprising to see such a large effect size on endpoints that are very much dependent on operators and diverge within the first day.” Probably, Dr. Mehra said, “it has to do with this being a single-center study that may not be generalizable to other practices.”

CASTLE HTx was supported by a grant from Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung. Dr. Sommer discloses consulting for Abbott, Biosense Webster, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic. Dr. Sohns reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Gustafsson discloses receiving honoraria or fees for consulting from Abbott, Alnylam Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Ionis, Novartis, and Pfizer; serving on a speakers bureau for Astra Zeneca and Orion; and receiving grants from Corvia Research. Dr. Mehra has reported receiving payments to his institution from Abbott for consulting; consulting fees from Janssen, Mesoblast, Broadview Ventures, Natera, Paragonix, Moderna, and the Baim Institute for Clinical Research; and serving on a scientific advisory board for NuPulseCV, Leviticus, and FineHeart.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Catheter ablation had long taken atrial fibrillation (AF) rhythm control to the next level before clinical trials showed it could help keep AF patients with heart failure (HF) alive and out of the hospital.

But those trials didn’t include many patients with AF on top of advanced or even end-stage HF. Lacking much of an evidence base and often viewed as too sick to gain a lot from the procedure, patients with AF and advanced HF aren’t offered ablation very often.

Now a randomized trial suggests that, on the contrary, AF ablation may confer a similar benefit to patients with HF so advanced that they were referred for evaluation at a transplant center.

The study, modestly sized with fewer than 200 such patients and conducted at a single center, assigned half of them to receive ablation and the other half to continued medical management.

Risk for the composite primary endpoint plunged 76% over a median of 18 months for those who underwent ablation. The outcome comprised death from any cause, implantation of a left ventricular assist device (LVAD), or urgent heart transplantation.

The advantage for ablation emerged early enough that the trial, CASTLE-HTx, was halted for benefit only a year after reaching its planned enrollment, observed Christian Sohns, MD, when formally presenting the results in Amsterdam at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The difference in the primary endpoint “in this severely sick cohort of advanced, end-stage heart failure patients,” he said, was driven mostly by fewer deaths, especially cardiovascular deaths, in the ablation group.

Ablation’s effect on outcomes was associated, perhaps causally, with significant gains in left ventricular (LV) function and more than triple the reduction in AF burden seen in the control group, noted Dr. Sohns, from the Heart and Diabetes Center North-Rhine Westphalia, Bad Oeynhausen, Germany.

states the CASTLE-HTx primary report, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, with Dr. Sohns as lead author, in tandem with his ESC presentation.

One of the study’s key messages “is that AF ablation is safe and effective in patients with end-stage heart failure” and “should be part of our armamentarium” for treating them, said Philipp Sommer, MD, also with Heart and Diabetes Center North-Rhine Westphalia, at a press conference preceding Dr. Sohns’ presentation of CASTLE-HTx.

The intervention could potentially help such patients survive longer on transplant wait lists and even delay need for the surgery, proposed Dr. Sommer, who is senior author on the trial’s publication.

CASTLE-HTx suggests that patients with advanced HF and even persistent AF, “if they have reasonably small atria, should be actually considered for ablation, as it may prevent the need for heart transplant or LVAD implant,” said invited discussant Finn Gustafsson, MD, PhD, DMSc, after Dr. Sohns’ presentation. “And that, of course, would be a huge achievement.”

The trial “should, if anything, help eradicate the current somewhat nihilistic approach to atrial fibrillation management in patients with advanced heart failure,” said Dr. Gustafsson, medical director of cardiac transplantation and mechanical circulatory support, Rigshopsitalet Copenhagen University Hospital.

Still, he disputed the characterization by the investigators and indeed the published report that the patients, or most of them, had “end-stage heart failure.”

For example, about a third of the trial’s patients started out in NYHA class 2, Dr. Gustafsson noted. Not that they weren’t “high-risk” or their HF wasn’t severe, he offered, but they don’t seem to have been “a truly advanced heart failure population.”

The trial population consisted of “patients referred to an advanced heart failure center, rather than patients with advanced heart failure,” agreed Mandeep R. Mehra, MD, director of the Center for Advanced Heart Disease at Brigham and Woman’s Hospital, Boston.

Also citing a large prevalence of patients in NYHA class-2, Dr. Mehra added that “we almost never see paroxysmal atrial fib in these patients. It’s usually an early-stage phenomenon.” In advanced HF, AF “is usually permanent,” he told this news organization. Yet it was paroxysmal in about 30% of cases.

To its credit, Dr. Mehra observed, the study does assert that advanced HF is no reason, necessarily, to avoid catheter ablation. Nor should an AF patient’s referral to an advanced-HF center “mean that you should rush to an LVAD or transplant” before considering ablation.

The study seems to be saying, “please exhaust all options before you biologically replace the heart or put in an LVAD,” Dr. Mehra said. “Certainly, this paper steers you in that direction.”

The trial entered 194 patients with symptomatic AF and HF of at least NYHA class 2, with impaired functional capacity by the 6-minute walk test, who had been referred to a major center in Germany for a heart-transplantation workup. With all on guideline-directed medical therapy, 97 were randomly assigned open-label to catheter ablation and 97 to continued standard care.

Catheter ablation was actually carried out in 81 patients (84%) who had been assigned to it and in 16 (16%) of those in the control group, the report states.

A total of 8 in the ablation group and 29 in the control arm died, received an LVAD, or went to urgent transplantation, for a hazard ratio of 0.24 (95% confidence interval, 0.11-0.52; P < .001) for the primary endpoint.

Death from any cause apparently played a big role in the risk reduction; its HR was 0.29 (95% CI, 0.12-0.72).

One peculiarity of the data, Dr. Mehra said, is that event curves for the primary endpoint and its individual components “diverge almost from day 1.” That would mean the ablation group right away started having fewer deaths, LVAD placements, or heart transplants than the control group.

“It is surprising to see such a large effect size on endpoints that are very much dependent on operators and diverge within the first day.” Probably, Dr. Mehra said, “it has to do with this being a single-center study that may not be generalizable to other practices.”

CASTLE HTx was supported by a grant from Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung. Dr. Sommer discloses consulting for Abbott, Biosense Webster, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic. Dr. Sohns reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Gustafsson discloses receiving honoraria or fees for consulting from Abbott, Alnylam Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Ionis, Novartis, and Pfizer; serving on a speakers bureau for Astra Zeneca and Orion; and receiving grants from Corvia Research. Dr. Mehra has reported receiving payments to his institution from Abbott for consulting; consulting fees from Janssen, Mesoblast, Broadview Ventures, Natera, Paragonix, Moderna, and the Baim Institute for Clinical Research; and serving on a scientific advisory board for NuPulseCV, Leviticus, and FineHeart.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ESC CONGRESS 2023

FIRE a win for physiology-guided MI complete revascularization in older patients

(MVD) in a large, randomized trial.

In the study with more than 1,400 patients, CR was guided by assessments of the functional effect of coronary lesions other than the MI culprit, a process that selects or excludes the lesions, regardless of angiographic profile, as targets for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Such physiology-guided CR led to a significant 27% drop in risk for a composite primary endpoint over 1 year in the trial, called FIRE (Functional Assessment in Elderly MI Patients with Multivessel Disease), compared with the culprit-only approach. The endpoint included death, MI, stroke, or ischemia-driven revascularization.

Risk for cardiovascular (CV) death or MI fell by 36% in the trial, and all-cause mortality declined 30%. The differences were significant, although the study wasn’t powered for those secondary endpoints. Safety outcomes were similar for the two revascularization approaches.

FIRE was noteworthy for entering only patients with ST-segment elevation or non–ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI or NSTEMI) who were age 75 years or older, a higher-risk age group poorly represented in earlier CR trials. Such patients in practice are usually managed with the culprit lesion–only approach because of a lack of good evidence supporting CR, observed Simone Biscaglia, MD, the study’s principal investigator.

“This is the first trial actually showing a benefit” from physiology-guided CR in older patients with acute MI that is similar to what the strategy can offer younger patients, said Dr. Biscaglia, from Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria S. Anna, Ferrara, Italy.

Biscaglia made the comments at a media briefing on FIRE held during the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, where he presented the study. He is also lead author on its publication in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“This is a remarkable trial that adds substantially to prior studies that examined the topic of complete versus culprit-only revascularization,” Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, MPH, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said in an interview.

It shows “quite clearly” that physiology-guided CR is superior to the culprit-only approach in patients with acute MI, said Dr. Bhatt, who is also director of Mount Sinai Heart at Mount Sinai Hospital and not connected to FIRE.

The primary findings applied to a range of different patient subgroups, including those older than 80. That’s important, he said, because “it is sometimes incorrectly assumed that patients who are older may not benefit from complete revascularization in this setting.”

And the trial’s finding of reduced risk for CV death or MI in the CR group “really should make the complete revascularization approach the standard of care in MI patients without contraindications,” Dr. Bhatt said. And certainly, “age per se should no longer be considered a contraindication.”

“First and foremost, the FIRE trial confirms the benefit of complete revascularization that has been observed in previous trials and provides additional evidence for this approach in older patients,” wrote the author of an editorial accompanying the published report.

The mortality reduction with CR at 1 years “is particularly notable” and underscores that CR should be considered in all patients with acute MI, “regardless of age,” wrote Shamir R. Mehta, MD, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., and Hamilton Health Sciences.

Dr. Mehta was principal investigator for the 2019 COMPLETE trial, which made the case for CR, guided by standard angiography, in patients with MVD and STEMI; their age averaged about 62 years.

FIRE definitely ought to sway practice toward greater use of physiology-guided CR regardless of age, observed Vijay Kunadian, MBBS, MD, invited discussant for the Biscaglia presentation. “My oldest patient is 98,” she said, “and it is beneficial without a doubt.”

But Dr. Kunadian, from Newcastle (England) University, said that the trial results can’t be generalized to all older patients. That’s because their outcomes after CR could vary depending on, for example, their different frailties or comorbidities, cognition, or CV history. “So, there is an absolute need to individualize care.”

FIRE enrolled patients 75 years or older with MVD, about 64% male, who had been admitted with acute STEMI or NSTEMI at 34 sites in Italy, Spain, and Poland. All underwent successful culprit-lesion PCI using, as “strongly” recommended, the same model of sirolimus-eluting stent.

Patients were randomly assigned to physiology-guided CR of nonculprit lesions, at the same session or at least during the same hospitalization, or to no further revascularization: 720 and 725 patients, respectively.

The hazard ratio for the composite primary outcome, CR versus culprit-only PCI was 0.73 (95% confidence interval, 0.57-0.93; P = .01). The benefit was driven by reductions in three individual components of the primary endpoint: death, MI, and revascularization, but not stroke.

The HR for CV death or MI was 0.64 (95% CI, 0.47-0.88) and for death from any cause was 0.70 (95% CI, 0.51-0.96).

There was no significant difference in the primary safety outcome, a composite of contrast-related acute kidney injury, stroke, or Bleeding Academic Research Consortium grade 3 to 5 bleeding at 1 year. The rates were 22.5% in those assigned to CR and 20.4% in the culprit-only group.

The functional effect of individual lesions was assessed by either of two methods, crossing them with a standard “pressure wire” or by angiographic derivation of their quantitative flow ratio.

The choice was “left to operator discretion,” Dr. Biscaglia said in an interview, “because we wanted to mirror clinical practice at the participating centers.” Still, the CR primary benefit was independent of the physiology-guidance method.

FIRE’s sponsor – the nonprofit Consorzio Futuro in Ricerca, Italy – received grant support from Sahajanand Medical Technologies, Medis Medical Imaging systems, Eukon, Siemens Healthineers, General Electric Healthcare, and Insight Lifetech. Dr. Biscaglia had no other disclosures. Dr. Mehta reported receiving grants from Abbott Vascular and personal fees from Amgen, Janssen, and Bristol Myers Squibb. Dr. Bhatt reported numerous disclosures with various companies and organizations. Dr. Kunadian had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

(MVD) in a large, randomized trial.

In the study with more than 1,400 patients, CR was guided by assessments of the functional effect of coronary lesions other than the MI culprit, a process that selects or excludes the lesions, regardless of angiographic profile, as targets for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Such physiology-guided CR led to a significant 27% drop in risk for a composite primary endpoint over 1 year in the trial, called FIRE (Functional Assessment in Elderly MI Patients with Multivessel Disease), compared with the culprit-only approach. The endpoint included death, MI, stroke, or ischemia-driven revascularization.

Risk for cardiovascular (CV) death or MI fell by 36% in the trial, and all-cause mortality declined 30%. The differences were significant, although the study wasn’t powered for those secondary endpoints. Safety outcomes were similar for the two revascularization approaches.

FIRE was noteworthy for entering only patients with ST-segment elevation or non–ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI or NSTEMI) who were age 75 years or older, a higher-risk age group poorly represented in earlier CR trials. Such patients in practice are usually managed with the culprit lesion–only approach because of a lack of good evidence supporting CR, observed Simone Biscaglia, MD, the study’s principal investigator.

“This is the first trial actually showing a benefit” from physiology-guided CR in older patients with acute MI that is similar to what the strategy can offer younger patients, said Dr. Biscaglia, from Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria S. Anna, Ferrara, Italy.

Biscaglia made the comments at a media briefing on FIRE held during the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, where he presented the study. He is also lead author on its publication in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“This is a remarkable trial that adds substantially to prior studies that examined the topic of complete versus culprit-only revascularization,” Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, MPH, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said in an interview.

It shows “quite clearly” that physiology-guided CR is superior to the culprit-only approach in patients with acute MI, said Dr. Bhatt, who is also director of Mount Sinai Heart at Mount Sinai Hospital and not connected to FIRE.

The primary findings applied to a range of different patient subgroups, including those older than 80. That’s important, he said, because “it is sometimes incorrectly assumed that patients who are older may not benefit from complete revascularization in this setting.”

And the trial’s finding of reduced risk for CV death or MI in the CR group “really should make the complete revascularization approach the standard of care in MI patients without contraindications,” Dr. Bhatt said. And certainly, “age per se should no longer be considered a contraindication.”

“First and foremost, the FIRE trial confirms the benefit of complete revascularization that has been observed in previous trials and provides additional evidence for this approach in older patients,” wrote the author of an editorial accompanying the published report.

The mortality reduction with CR at 1 years “is particularly notable” and underscores that CR should be considered in all patients with acute MI, “regardless of age,” wrote Shamir R. Mehta, MD, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., and Hamilton Health Sciences.

Dr. Mehta was principal investigator for the 2019 COMPLETE trial, which made the case for CR, guided by standard angiography, in patients with MVD and STEMI; their age averaged about 62 years.

FIRE definitely ought to sway practice toward greater use of physiology-guided CR regardless of age, observed Vijay Kunadian, MBBS, MD, invited discussant for the Biscaglia presentation. “My oldest patient is 98,” she said, “and it is beneficial without a doubt.”

But Dr. Kunadian, from Newcastle (England) University, said that the trial results can’t be generalized to all older patients. That’s because their outcomes after CR could vary depending on, for example, their different frailties or comorbidities, cognition, or CV history. “So, there is an absolute need to individualize care.”

FIRE enrolled patients 75 years or older with MVD, about 64% male, who had been admitted with acute STEMI or NSTEMI at 34 sites in Italy, Spain, and Poland. All underwent successful culprit-lesion PCI using, as “strongly” recommended, the same model of sirolimus-eluting stent.

Patients were randomly assigned to physiology-guided CR of nonculprit lesions, at the same session or at least during the same hospitalization, or to no further revascularization: 720 and 725 patients, respectively.

The hazard ratio for the composite primary outcome, CR versus culprit-only PCI was 0.73 (95% confidence interval, 0.57-0.93; P = .01). The benefit was driven by reductions in three individual components of the primary endpoint: death, MI, and revascularization, but not stroke.

The HR for CV death or MI was 0.64 (95% CI, 0.47-0.88) and for death from any cause was 0.70 (95% CI, 0.51-0.96).

There was no significant difference in the primary safety outcome, a composite of contrast-related acute kidney injury, stroke, or Bleeding Academic Research Consortium grade 3 to 5 bleeding at 1 year. The rates were 22.5% in those assigned to CR and 20.4% in the culprit-only group.

The functional effect of individual lesions was assessed by either of two methods, crossing them with a standard “pressure wire” or by angiographic derivation of their quantitative flow ratio.

The choice was “left to operator discretion,” Dr. Biscaglia said in an interview, “because we wanted to mirror clinical practice at the participating centers.” Still, the CR primary benefit was independent of the physiology-guidance method.

FIRE’s sponsor – the nonprofit Consorzio Futuro in Ricerca, Italy – received grant support from Sahajanand Medical Technologies, Medis Medical Imaging systems, Eukon, Siemens Healthineers, General Electric Healthcare, and Insight Lifetech. Dr. Biscaglia had no other disclosures. Dr. Mehta reported receiving grants from Abbott Vascular and personal fees from Amgen, Janssen, and Bristol Myers Squibb. Dr. Bhatt reported numerous disclosures with various companies and organizations. Dr. Kunadian had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

(MVD) in a large, randomized trial.

In the study with more than 1,400 patients, CR was guided by assessments of the functional effect of coronary lesions other than the MI culprit, a process that selects or excludes the lesions, regardless of angiographic profile, as targets for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Such physiology-guided CR led to a significant 27% drop in risk for a composite primary endpoint over 1 year in the trial, called FIRE (Functional Assessment in Elderly MI Patients with Multivessel Disease), compared with the culprit-only approach. The endpoint included death, MI, stroke, or ischemia-driven revascularization.

Risk for cardiovascular (CV) death or MI fell by 36% in the trial, and all-cause mortality declined 30%. The differences were significant, although the study wasn’t powered for those secondary endpoints. Safety outcomes were similar for the two revascularization approaches.

FIRE was noteworthy for entering only patients with ST-segment elevation or non–ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI or NSTEMI) who were age 75 years or older, a higher-risk age group poorly represented in earlier CR trials. Such patients in practice are usually managed with the culprit lesion–only approach because of a lack of good evidence supporting CR, observed Simone Biscaglia, MD, the study’s principal investigator.

“This is the first trial actually showing a benefit” from physiology-guided CR in older patients with acute MI that is similar to what the strategy can offer younger patients, said Dr. Biscaglia, from Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria S. Anna, Ferrara, Italy.

Biscaglia made the comments at a media briefing on FIRE held during the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, where he presented the study. He is also lead author on its publication in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“This is a remarkable trial that adds substantially to prior studies that examined the topic of complete versus culprit-only revascularization,” Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, MPH, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said in an interview.

It shows “quite clearly” that physiology-guided CR is superior to the culprit-only approach in patients with acute MI, said Dr. Bhatt, who is also director of Mount Sinai Heart at Mount Sinai Hospital and not connected to FIRE.

The primary findings applied to a range of different patient subgroups, including those older than 80. That’s important, he said, because “it is sometimes incorrectly assumed that patients who are older may not benefit from complete revascularization in this setting.”

And the trial’s finding of reduced risk for CV death or MI in the CR group “really should make the complete revascularization approach the standard of care in MI patients without contraindications,” Dr. Bhatt said. And certainly, “age per se should no longer be considered a contraindication.”

“First and foremost, the FIRE trial confirms the benefit of complete revascularization that has been observed in previous trials and provides additional evidence for this approach in older patients,” wrote the author of an editorial accompanying the published report.

The mortality reduction with CR at 1 years “is particularly notable” and underscores that CR should be considered in all patients with acute MI, “regardless of age,” wrote Shamir R. Mehta, MD, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., and Hamilton Health Sciences.

Dr. Mehta was principal investigator for the 2019 COMPLETE trial, which made the case for CR, guided by standard angiography, in patients with MVD and STEMI; their age averaged about 62 years.

FIRE definitely ought to sway practice toward greater use of physiology-guided CR regardless of age, observed Vijay Kunadian, MBBS, MD, invited discussant for the Biscaglia presentation. “My oldest patient is 98,” she said, “and it is beneficial without a doubt.”

But Dr. Kunadian, from Newcastle (England) University, said that the trial results can’t be generalized to all older patients. That’s because their outcomes after CR could vary depending on, for example, their different frailties or comorbidities, cognition, or CV history. “So, there is an absolute need to individualize care.”

FIRE enrolled patients 75 years or older with MVD, about 64% male, who had been admitted with acute STEMI or NSTEMI at 34 sites in Italy, Spain, and Poland. All underwent successful culprit-lesion PCI using, as “strongly” recommended, the same model of sirolimus-eluting stent.

Patients were randomly assigned to physiology-guided CR of nonculprit lesions, at the same session or at least during the same hospitalization, or to no further revascularization: 720 and 725 patients, respectively.

The hazard ratio for the composite primary outcome, CR versus culprit-only PCI was 0.73 (95% confidence interval, 0.57-0.93; P = .01). The benefit was driven by reductions in three individual components of the primary endpoint: death, MI, and revascularization, but not stroke.

The HR for CV death or MI was 0.64 (95% CI, 0.47-0.88) and for death from any cause was 0.70 (95% CI, 0.51-0.96).

There was no significant difference in the primary safety outcome, a composite of contrast-related acute kidney injury, stroke, or Bleeding Academic Research Consortium grade 3 to 5 bleeding at 1 year. The rates were 22.5% in those assigned to CR and 20.4% in the culprit-only group.

The functional effect of individual lesions was assessed by either of two methods, crossing them with a standard “pressure wire” or by angiographic derivation of their quantitative flow ratio.

The choice was “left to operator discretion,” Dr. Biscaglia said in an interview, “because we wanted to mirror clinical practice at the participating centers.” Still, the CR primary benefit was independent of the physiology-guidance method.

FIRE’s sponsor – the nonprofit Consorzio Futuro in Ricerca, Italy – received grant support from Sahajanand Medical Technologies, Medis Medical Imaging systems, Eukon, Siemens Healthineers, General Electric Healthcare, and Insight Lifetech. Dr. Biscaglia had no other disclosures. Dr. Mehta reported receiving grants from Abbott Vascular and personal fees from Amgen, Janssen, and Bristol Myers Squibb. Dr. Bhatt reported numerous disclosures with various companies and organizations. Dr. Kunadian had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE ESC CONGRESS 2023

ECMO for shock in acute MI won’t help, may harm: ECLS-SHOCK

Patients with acute myocardial infarction (MI) and shock are often put on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support before heading to the catheterization laboratory. But the practice, done routinely, doesn’t have much backing from randomized trials. Now it’s being challenged by one of the largest such studies to explore the issue.

ECMO-managed patients, moreover, had sharply increased risks for moderate and severe bleeding and vascular complications.

A challenge to common practice

The results undercut guidelines that promote mechanical circulatory support in MI-related cardiogenic shock primarily based on observational data, and they argue against what’s become common practice, said Holger Thiele, MD, Heart Center Leipzig, University of Leipzig, Germany.

Such use of ECMO could well offer some type of advantage in MI-related shock, but the data so far don’t show it, Dr. Thiele said at a press conference on the new study, called ECLS-SHOCK, at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology in Amsterdam. He formally presented the trial at the meeting and is lead author on its simultaneous publication in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Almost half of the trial’s patients died, whether or not they had been put on ECMO. All-cause mortality at 30 days, the primary endpoint, was about the same, at 47.8% and 49.0% for the ECMO and usual-care groups, respectively.

Meanwhile, Dr. Thiele reported, risks for moderate or severe bleeding more than doubled and serious peripheral vascular complications almost tripled with addition of ECMO support.

The findings, he noted, are consistent with a new meta-analysis of trials testing ECMO in MI-related shock that also showed increases in bleeding with survival gains using the devices. Dr. Thiele is senior author on that report, published in The Lancet to coincide with his ECLS-SHOCK presentation.

Would any subgroups benefit?

Importantly, he said in an interview, ECMO’s failure to improve 30-day survival in the trial probably applies across the spectrum of patients with MI-related shock. Subgroup analyses in both ECLS-SHOCK and the meta-analysis didn’t identify any groups that benefit, Dr. Thiele observed.

For example, there were no significant differences for the primary outcome by age, sex, whether the MI was ST-segment elevation MI or non–ST-segment elevation MI or anterior or nonanterior, or whether the patient had diabetes.

If there is a subgroup in MI-related shock that is likely to benefit from the intervention with lower mortality, he said, “it’s less than 1%, if you ask me.”

An accompanying editorial essentially agreed, arguing that ECLS-SHOCK contests the intervention’s broad application in MI-related shock without shedding light on any selective benefits.

“Will the results of the ECLS-SHOCK trial change current clinical practice? If the goal of [ECMO] is to improve 30-day mortality, these data should steer interventional and critical care cardiologists away from its early routine implementation for all or even most patients with myocardial infarction and cardiogenic shock,” the editorialists say.

“There will be some patients in this population for whom [ECMO] is necessary and lifesaving, but the results of the ECLS-SHOCK trial do not tell us which ones,” write Jane A. Leopold, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and Darren B. Taichman, MD, PhD, Penn Presbyterian Medical Center, Philadelphia.

“For now, the best course may be to reserve the early initiation of [ECMO] for those patients with infarct-related cardiogenic shock in whom the likely benefits more clearly outweigh the potential harms. We need further studies to tell us who they are,” write Dr. Leopold and Dr. Taichman, who are deputy editors with The New England Journal of Medicine.

ECLS-SHOCK randomly assigned 420 patients with acute MI complicated by shock and slated for coronary revascularization to receive standard care with or without early ECMO at 44 centers in Germany and Slovenia. Their median age was 63 years, and about 81% were men.

The relative risk for death from any cause, ECMO vs. usual care, was flatly nonsignificant at 0.98 (95% confidence interval, 0.80-1.19; P = .81).

ECMO came at the cost of significantly more cases of the primary safety endpoint, moderate or severe bleeding by Bleeding Academic Research Consortium criteria. That endpoint was met by 23.4% of ECMO patients and 9.6% of the control group, for an RR of 2.44 (95% CI, 1.50-3.95).

Rates of stroke or systemic embolization were nonsignificantly different at 3.8% and 2.9%, respectively (RR, 1.33; 95% CI, 0.47-3.76).

Speaking with this news organization, Sripal Bangalore, MD, MHA, pointed out that only 5.8% of the ECMO group but about 32% of those managed with usual care received some form of left ventricular (LV) unloading therapy.

Such measures can include atrial septostomy or the addition of an intra-aortic balloon pump or percutaneous LV-assist pump.

Given that ECMO increases afterload, “which is physiologically detrimental in patients with an ongoing MI, one is left to wonder if the results would have been different with greater use of LV unloading,” said Dr. Bangalore, of NYU Langone Health, New York, who isn’t associated with ECLS-SHOCK.

Also, he pointed out, about 78% of the trial’s patients had experienced some degree of cardiopulmonary resuscitation despite exclusion of anyone who had undergone it for more than 45 minutes. That may make the study more generalizable but also harder to show a benefit from ECMO. “The overall prognosis of that subset of patients despite heroic efforts is bleak at best.”

Dr. Thiele had no disclosures; statements for the other authors can be found at nejm.org. Dr. Bangalore has previously disclosed financial relationships with Abbott Vascular, Amgen, Biotronik, Inari, Pfizer, Reata, and Truvic. Dr. Leopold reports grants from Astellas and personal fees from United Therapeutics, Abbott Vascular, and North America Thrombosis Forum. Dr. Leopold and Dr. Taichman both report employment by The New England Journal of Medicine.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients with acute myocardial infarction (MI) and shock are often put on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support before heading to the catheterization laboratory. But the practice, done routinely, doesn’t have much backing from randomized trials. Now it’s being challenged by one of the largest such studies to explore the issue.

ECMO-managed patients, moreover, had sharply increased risks for moderate and severe bleeding and vascular complications.

A challenge to common practice

The results undercut guidelines that promote mechanical circulatory support in MI-related cardiogenic shock primarily based on observational data, and they argue against what’s become common practice, said Holger Thiele, MD, Heart Center Leipzig, University of Leipzig, Germany.

Such use of ECMO could well offer some type of advantage in MI-related shock, but the data so far don’t show it, Dr. Thiele said at a press conference on the new study, called ECLS-SHOCK, at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology in Amsterdam. He formally presented the trial at the meeting and is lead author on its simultaneous publication in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Almost half of the trial’s patients died, whether or not they had been put on ECMO. All-cause mortality at 30 days, the primary endpoint, was about the same, at 47.8% and 49.0% for the ECMO and usual-care groups, respectively.

Meanwhile, Dr. Thiele reported, risks for moderate or severe bleeding more than doubled and serious peripheral vascular complications almost tripled with addition of ECMO support.

The findings, he noted, are consistent with a new meta-analysis of trials testing ECMO in MI-related shock that also showed increases in bleeding with survival gains using the devices. Dr. Thiele is senior author on that report, published in The Lancet to coincide with his ECLS-SHOCK presentation.

Would any subgroups benefit?

Importantly, he said in an interview, ECMO’s failure to improve 30-day survival in the trial probably applies across the spectrum of patients with MI-related shock. Subgroup analyses in both ECLS-SHOCK and the meta-analysis didn’t identify any groups that benefit, Dr. Thiele observed.

For example, there were no significant differences for the primary outcome by age, sex, whether the MI was ST-segment elevation MI or non–ST-segment elevation MI or anterior or nonanterior, or whether the patient had diabetes.

If there is a subgroup in MI-related shock that is likely to benefit from the intervention with lower mortality, he said, “it’s less than 1%, if you ask me.”

An accompanying editorial essentially agreed, arguing that ECLS-SHOCK contests the intervention’s broad application in MI-related shock without shedding light on any selective benefits.

“Will the results of the ECLS-SHOCK trial change current clinical practice? If the goal of [ECMO] is to improve 30-day mortality, these data should steer interventional and critical care cardiologists away from its early routine implementation for all or even most patients with myocardial infarction and cardiogenic shock,” the editorialists say.

“There will be some patients in this population for whom [ECMO] is necessary and lifesaving, but the results of the ECLS-SHOCK trial do not tell us which ones,” write Jane A. Leopold, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and Darren B. Taichman, MD, PhD, Penn Presbyterian Medical Center, Philadelphia.

“For now, the best course may be to reserve the early initiation of [ECMO] for those patients with infarct-related cardiogenic shock in whom the likely benefits more clearly outweigh the potential harms. We need further studies to tell us who they are,” write Dr. Leopold and Dr. Taichman, who are deputy editors with The New England Journal of Medicine.

ECLS-SHOCK randomly assigned 420 patients with acute MI complicated by shock and slated for coronary revascularization to receive standard care with or without early ECMO at 44 centers in Germany and Slovenia. Their median age was 63 years, and about 81% were men.

The relative risk for death from any cause, ECMO vs. usual care, was flatly nonsignificant at 0.98 (95% confidence interval, 0.80-1.19; P = .81).

ECMO came at the cost of significantly more cases of the primary safety endpoint, moderate or severe bleeding by Bleeding Academic Research Consortium criteria. That endpoint was met by 23.4% of ECMO patients and 9.6% of the control group, for an RR of 2.44 (95% CI, 1.50-3.95).

Rates of stroke or systemic embolization were nonsignificantly different at 3.8% and 2.9%, respectively (RR, 1.33; 95% CI, 0.47-3.76).

Speaking with this news organization, Sripal Bangalore, MD, MHA, pointed out that only 5.8% of the ECMO group but about 32% of those managed with usual care received some form of left ventricular (LV) unloading therapy.

Such measures can include atrial septostomy or the addition of an intra-aortic balloon pump or percutaneous LV-assist pump.

Given that ECMO increases afterload, “which is physiologically detrimental in patients with an ongoing MI, one is left to wonder if the results would have been different with greater use of LV unloading,” said Dr. Bangalore, of NYU Langone Health, New York, who isn’t associated with ECLS-SHOCK.

Also, he pointed out, about 78% of the trial’s patients had experienced some degree of cardiopulmonary resuscitation despite exclusion of anyone who had undergone it for more than 45 minutes. That may make the study more generalizable but also harder to show a benefit from ECMO. “The overall prognosis of that subset of patients despite heroic efforts is bleak at best.”

Dr. Thiele had no disclosures; statements for the other authors can be found at nejm.org. Dr. Bangalore has previously disclosed financial relationships with Abbott Vascular, Amgen, Biotronik, Inari, Pfizer, Reata, and Truvic. Dr. Leopold reports grants from Astellas and personal fees from United Therapeutics, Abbott Vascular, and North America Thrombosis Forum. Dr. Leopold and Dr. Taichman both report employment by The New England Journal of Medicine.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients with acute myocardial infarction (MI) and shock are often put on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support before heading to the catheterization laboratory. But the practice, done routinely, doesn’t have much backing from randomized trials. Now it’s being challenged by one of the largest such studies to explore the issue.

ECMO-managed patients, moreover, had sharply increased risks for moderate and severe bleeding and vascular complications.

A challenge to common practice

The results undercut guidelines that promote mechanical circulatory support in MI-related cardiogenic shock primarily based on observational data, and they argue against what’s become common practice, said Holger Thiele, MD, Heart Center Leipzig, University of Leipzig, Germany.

Such use of ECMO could well offer some type of advantage in MI-related shock, but the data so far don’t show it, Dr. Thiele said at a press conference on the new study, called ECLS-SHOCK, at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology in Amsterdam. He formally presented the trial at the meeting and is lead author on its simultaneous publication in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Almost half of the trial’s patients died, whether or not they had been put on ECMO. All-cause mortality at 30 days, the primary endpoint, was about the same, at 47.8% and 49.0% for the ECMO and usual-care groups, respectively.

Meanwhile, Dr. Thiele reported, risks for moderate or severe bleeding more than doubled and serious peripheral vascular complications almost tripled with addition of ECMO support.

The findings, he noted, are consistent with a new meta-analysis of trials testing ECMO in MI-related shock that also showed increases in bleeding with survival gains using the devices. Dr. Thiele is senior author on that report, published in The Lancet to coincide with his ECLS-SHOCK presentation.

Would any subgroups benefit?

Importantly, he said in an interview, ECMO’s failure to improve 30-day survival in the trial probably applies across the spectrum of patients with MI-related shock. Subgroup analyses in both ECLS-SHOCK and the meta-analysis didn’t identify any groups that benefit, Dr. Thiele observed.

For example, there were no significant differences for the primary outcome by age, sex, whether the MI was ST-segment elevation MI or non–ST-segment elevation MI or anterior or nonanterior, or whether the patient had diabetes.

If there is a subgroup in MI-related shock that is likely to benefit from the intervention with lower mortality, he said, “it’s less than 1%, if you ask me.”

An accompanying editorial essentially agreed, arguing that ECLS-SHOCK contests the intervention’s broad application in MI-related shock without shedding light on any selective benefits.

“Will the results of the ECLS-SHOCK trial change current clinical practice? If the goal of [ECMO] is to improve 30-day mortality, these data should steer interventional and critical care cardiologists away from its early routine implementation for all or even most patients with myocardial infarction and cardiogenic shock,” the editorialists say.

“There will be some patients in this population for whom [ECMO] is necessary and lifesaving, but the results of the ECLS-SHOCK trial do not tell us which ones,” write Jane A. Leopold, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and Darren B. Taichman, MD, PhD, Penn Presbyterian Medical Center, Philadelphia.

“For now, the best course may be to reserve the early initiation of [ECMO] for those patients with infarct-related cardiogenic shock in whom the likely benefits more clearly outweigh the potential harms. We need further studies to tell us who they are,” write Dr. Leopold and Dr. Taichman, who are deputy editors with The New England Journal of Medicine.

ECLS-SHOCK randomly assigned 420 patients with acute MI complicated by shock and slated for coronary revascularization to receive standard care with or without early ECMO at 44 centers in Germany and Slovenia. Their median age was 63 years, and about 81% were men.

The relative risk for death from any cause, ECMO vs. usual care, was flatly nonsignificant at 0.98 (95% confidence interval, 0.80-1.19; P = .81).

ECMO came at the cost of significantly more cases of the primary safety endpoint, moderate or severe bleeding by Bleeding Academic Research Consortium criteria. That endpoint was met by 23.4% of ECMO patients and 9.6% of the control group, for an RR of 2.44 (95% CI, 1.50-3.95).

Rates of stroke or systemic embolization were nonsignificantly different at 3.8% and 2.9%, respectively (RR, 1.33; 95% CI, 0.47-3.76).

Speaking with this news organization, Sripal Bangalore, MD, MHA, pointed out that only 5.8% of the ECMO group but about 32% of those managed with usual care received some form of left ventricular (LV) unloading therapy.

Such measures can include atrial septostomy or the addition of an intra-aortic balloon pump or percutaneous LV-assist pump.

Given that ECMO increases afterload, “which is physiologically detrimental in patients with an ongoing MI, one is left to wonder if the results would have been different with greater use of LV unloading,” said Dr. Bangalore, of NYU Langone Health, New York, who isn’t associated with ECLS-SHOCK.

Also, he pointed out, about 78% of the trial’s patients had experienced some degree of cardiopulmonary resuscitation despite exclusion of anyone who had undergone it for more than 45 minutes. That may make the study more generalizable but also harder to show a benefit from ECMO. “The overall prognosis of that subset of patients despite heroic efforts is bleak at best.”

Dr. Thiele had no disclosures; statements for the other authors can be found at nejm.org. Dr. Bangalore has previously disclosed financial relationships with Abbott Vascular, Amgen, Biotronik, Inari, Pfizer, Reata, and Truvic. Dr. Leopold reports grants from Astellas and personal fees from United Therapeutics, Abbott Vascular, and North America Thrombosis Forum. Dr. Leopold and Dr. Taichman both report employment by The New England Journal of Medicine.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ESC CONGRESS 2023

Triglyceride puzzle: Do TG metabolites better predict risk?

Triglyceride levels are a measure of cardiovascular risk and a target for therapy, but a focus on TG levels as a bad guy in CV risk assessments may be missing the mark, a population-based cohort study suggests.

The analysis, based on 30,000 participants in the Copenhagen General Population Study, saw sharply increased risks for all-cause mortality, CV mortality, and cancer mortality over 10 years among those with robust TG metabolism.

Those significant risks, gauged by concentrations of two molecules considered markers of TG metabolic rate, were independent of body mass index (BMI) and a range of other TG-linked risk factors, including plasma TG levels themselves.

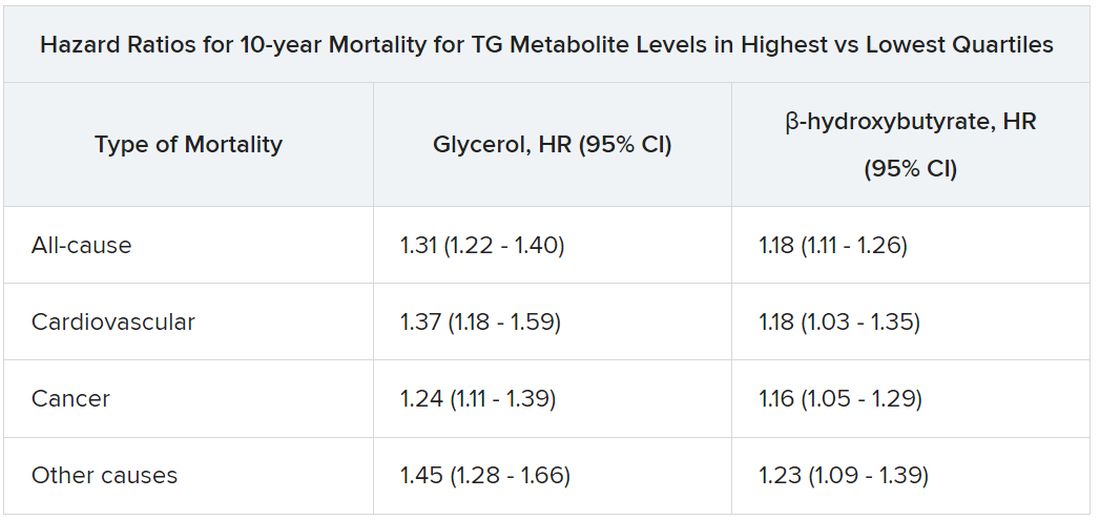

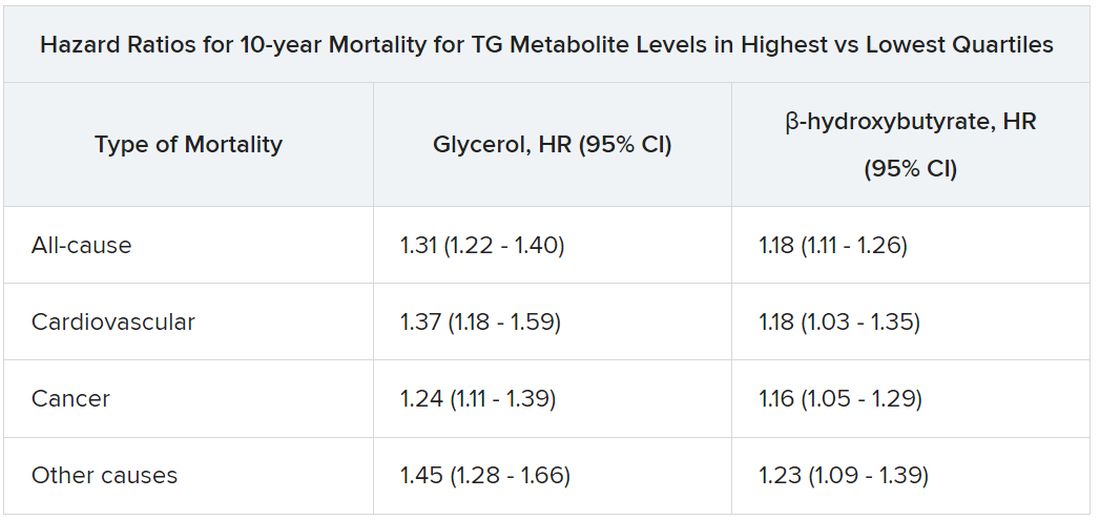

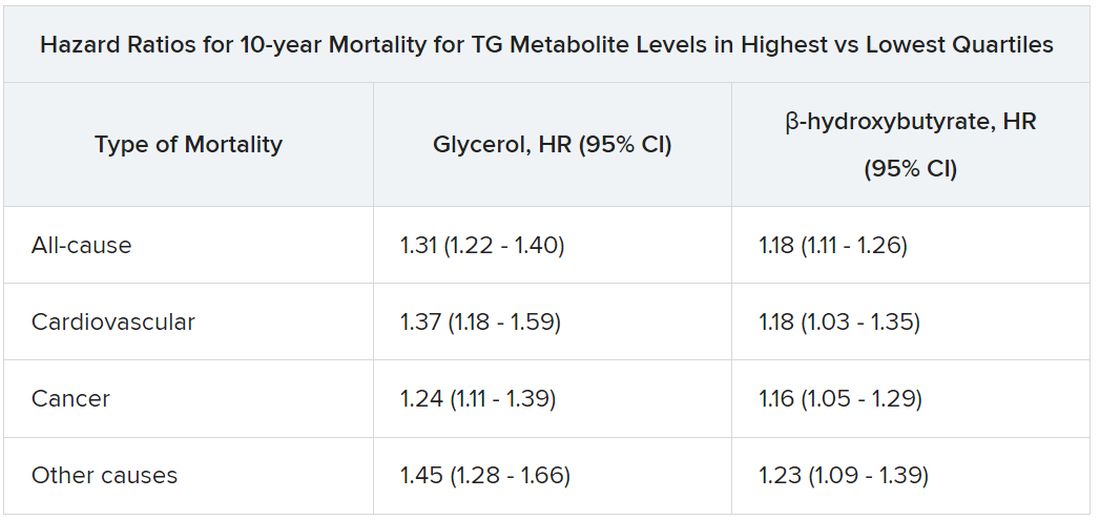

All-cause mortality jumped 31% for plasma levels of glycerol in the highest versus lowest quartiles and rose 18% for highest-quartile levels of beta-hydroxybutyrate. In parallel, CV mortality climbed 37% for glycerol and 18% for beta-hydroxybutyrate in the study, published in the European Heart Journal.

The findings “implicate triglyceride metabolic rate as a risk factor for mortality not explained by high plasma triglycerides or high BMI,” the report states. The study, it continues, may be the first to link increased mortality to more active TG metabolism – according to levels of the two biomarkers – in the general population.

The results were “really, really surprising,” senior author Børge G. Nordestgaard, MD, DMSc, said in an interview. They are “completely novel” and “may make people think differently” about TG and mortality risk.

Given their unexpected findings, the group conducted further analyses for evidence that the metabolite-mortality associations weren’t independent. “We tried to stratify them away, but they stayed,” said Dr. Nordestgaard, of the University of Copenhagen.

In a weight-stratified analysis, for example, findings were similar in people with normal weight and with overweight and who were obese, Dr. Nordestgaard observed. “Even in the ones with normal weight by World Health Organization criteria, we saw the same and maybe even stronger relationships” between TG metabolism and mortality.

The study authors were is careful to note the retrospective cohort study’s limitations, but its findings “at most support an association, not causation,” Michael Miller, MD, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, observed in an interview. Therefore, it can’t answer “whether and to what extent glycerol and/or beta-hydroxybutyrate independently contribute to mortality beyond triglyceride levels per se.”

Assessing levels of the two biomarkers “was an interesting way to indirectly assess whole-body TG metabolism,” but they were not fasting levels, said Dr. Miller, who wasn’t part of the study.

Also, the analysis doesn’t account for heparinization and other factors “that artificially raise glycerol levels” and suffers in other ways “from the inherent limitations of residual confounding,” said Dr. Miller, who is also chief of medicine at Corporal Michael J Crescenz VA Medical Center, Philadelphia.

The analysis tracked 30,000 men and women, participants in the much larger Copenhagen General Population Study cohort, for a median of 10.7 years. During that time, 9,897 of them died.

Plasma levels of glycerol and beta-hydroxybutyrate, the study authors noted, were measured using high-throughput nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy.

Glycerol levels greater than 80 mcmol/L represented the highest quartile and those less than 52 mcmol/L the lowest quartile. The corresponding beta-hydroxybutyrate quartiles were greater than 154 mcmol/L and less than 91 mcmol/L, respectively.

Mortality risks were independent not only of BMI and TG levels but also of age, greater waist circumference, many other standard CV risk factors, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, insulin use, and CV comorbidities and medications.

Dr. Nordestgaard, who also stressed that the findings are only hypothesis generating, speculated that glycerol and beta-hydroxybutyrate could potentially serve as biomarkers for predicting risk or guiding therapy and, indeed, might be amenable to risk-factor modification. “But I have absolutely no data to support that.”

The study was funded by the Independent Research Fund, and by Johan Boserup and Lise Boserups Grant. Dr. Nordestgaard reported consulting for or giving talks sponsored by AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Regeneron, Akcea, Amgen, Kowa, Denka, Amarin, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Esperion, and Silence Therapeutics. The other authors reported no conflicts. Dr. Miller disclosed serving as a scientific adviser for Amarin and 89bio.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Triglyceride levels are a measure of cardiovascular risk and a target for therapy, but a focus on TG levels as a bad guy in CV risk assessments may be missing the mark, a population-based cohort study suggests.

The analysis, based on 30,000 participants in the Copenhagen General Population Study, saw sharply increased risks for all-cause mortality, CV mortality, and cancer mortality over 10 years among those with robust TG metabolism.

Those significant risks, gauged by concentrations of two molecules considered markers of TG metabolic rate, were independent of body mass index (BMI) and a range of other TG-linked risk factors, including plasma TG levels themselves.