User login

Improving patient outcomes with better care transitions: The role for home health

The US health care system faces many challenges. Quality, cost, access, fragmentation, and misalignment of incentives are only a few. The most pressing dilemma is how this challenged system will handle the demographic wave of aging Americans. Our 21st-century population is living longer with a greater chronic disease burden than its predecessors, and has reasonable expectations of quality care. No setting portrays this challenge more clearly than that of transition: the transfer of a patient and his or her care from the hospital or facility setting to the home. Addressing this challenge requires that we adopt a set of proven effective interventions that can improve quality of care, meet the needs of the patients and families we serve, and lower the staggering economic and social burden of preventable hospital readmissions.

The Medicare system, designed in 1965, has not kept pace with the needs and challenges of the rapidly aging US population. Further, the system is not aligned with today’s—and tomorrow’s—needs. In 1965, average life expectancy for Americans was 70 years; by 2020, that average is predicted to be nearly 80 years.1 In 2000, one in eight Americans, or 12% of the US population, was aged 65 years or older.2 It is expected that by 2030, this group will represent 19% of the population. This means that in 2030, some 72 million Americans will be aged 65 or older—more than twice the number in this age group in 2000.2

The 1965 health care system focused on treating acute disease, but the health care system of the 21st century must effectively manage chronic disease. The burden of chronic disease is especially significant for aging patients, who are likely to be under the care of multiple providers and require multiple medications and ever-higher levels of professional care. The management and sequelae of chronic diseases frequently lead to impaired quality of life as well as significant expense for Medicare.

The discrepancy between our health care system and unmet needs is acutely obvious at the time of hospital discharge. In fact, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) has stated that this burden of unmet needs at hospital discharge is primarily driven by hospital admissions and readmissions.3 Thirty-day readmission rates among older Medicare beneficiaries range from 15% to 25%.4–6 Disagreement persists regarding what percentage of hospital readmissions within 30 days might be preventable. A systematic review of 34 studies has reported that, on average, 27% of readmissions were preventable.7

To address the challenge of avoidable readmissions, our home health and hospice care organization, Amedisys, Inc., developed a care transitions initiative designed to improve quality of life, improve patient outcomes, and prevent unnecessary hospital readmissions. This article, which includes an illustrative case study, describes the initiative and the outcomes observed during its first 12 months of testing.

CASE STUDY

Mrs. Smith is 84 years old and lives alone in her home. She suffers from mild to moderate dementia and heart failure (HF). Mrs. Smith’s daughter is her main caregiver, talking to Mrs. Smith multiple times a day and stopping by Mrs. Smith’s house at least two to three times a week.

Mrs. Smith was admitted to the hospital after her daughter brought her to the emergency department over the weekend because of shortness of breath. This was her third visit to the emergency department within the past year, with each visit resulting in a hospitalization. Because of questions regarding her homebound status, home health was not considered part of the care plan during either of Mrs. Smith’s previous discharges.

Hospitalists made rounds over the weekend and notified Mrs. Smith that she would be released on Tuesday morning; because of her weakness and disorientation, the hospitalist issued an order for home health and a prescription for a new HF medication. Upon hearing the news on Monday of the planned discharge, Mrs. Smith and her daughter selected the home health provider they wished to use and, within the next few hours, a care transitions coordinator (CTC) visited them in the hospital.

The CTC, a registered nurse, talked with Mrs. Smith about her illness, educating her on the impact of diet on her condition and the medications she takes, including the new medication prescribed by the hospitalist. Most importantly, the CTC talked to Mrs. Smith about her personal goals during her recovery. For example, Mrs. Smith loves to visit her granddaughter, where she spends hours at a time watching her great-grandchildren play. Mrs. Smith wants to control her HF so that she can continue these visits that bring her such joy.

Mrs. Smith’s daughter asked the CTC if she would make Mrs. Smith’s primary care physician aware of the change in medication and schedule an appointment within the next week. The CTC did so before Mrs. Smith left the hospital. She also completed a primary care discharge notification, which documented Mrs. Smith’s discharge diagnoses, discharge medications, important test results, and the date of the appointment, and e-faxed it to Mrs. Smith’s primary care physician. The CTC also communicated with the home health nurse who would care for Mrs. Smith following discharge, reviewing her clinical needs as well as her personal goals.

Mrs. Smith’s daughter was present when the home health nurse conducted the admission and in-home assessment. The home health nurse educated both Mrs. Smith and her daughter about foods that might exacerbate HF, reinforcing the education started in the hospital by the CTC. In the course of this conversation, Mrs. Smith’s daughter realized that her mother had been eating popcorn late at night when she could not sleep. The CTC helped both mother and daughter to understand that the salt in her popcorn could have an impact on Mrs. Smith’s illness that would likely result in rehospitalization and an increase in medication dosage; this educational process enhanced the patient’s understanding of her disease and likely reduced the chances of her emergency department–rehospitalization cycle continuing.

INTERVENTION

The design of the Amedisys care transitions initiative is based on work by Naylor et al8 and Coleman et al,6 who are recognized in the home health industry for their models of intervention at the time of hospital discharge. The Amedisys initiative’s objective is to prevent avoidable readmissions through patient and caregiver health coaching and care coordination, starting in the hospital and continuing through completion of the patient’s home health plan of care. Table 1 compares the essential interventions of the Naylor and Coleman models with those of the Amedisys initiative.

The Amedisys initiative includes these specific interventions:

- use of a CTC;

- early engagement of the patient, caregiver, and family with condition-specific coaching;

- careful medication management; and

- physician engagement with scheduling and reminders of physician visits early in the transition process.

Using a care transitions coordinator

Amedisys has placed CTCs in the acute care facilities that it serves. The CTC’s responsibility is to ensure that patients transition safely home from the acute care setting. With fragmentation of care, patients are most vulnerable during the initial few days postdischarge; this is particularly true for the frail elderly. Consequently, the CTC meets with the patient and caregiver as soon as possible upon his or her referral to Amedisys to plan the transition home from the facility and determine the resources needed once home. The CTC becomes the patient’s “touchpoint” for any questions or problems that arise between the time of discharge and the time when an Amedisys nurse visits the patient’s home.

Early engagement and coaching

The CTC uses a proprietary tool, Bridge to Healt0hy Living, to begin the process of early engagement, education, and coaching. This bound notebook is personalized for each patient with the CTC’s name and 24-hour phone contact information. The CTC records the patient’s diagnoses as well as social and economic barriers that may affect the patient’s outcomes. The diagnoses are written in the notebook along with a list of the patient’s medications that describes what each drug is for, its exact dosage, and instructions for taking it.

Coaching focuses on the patient’s diagnoses and capabilities, with discussion of diet and lifestyle needs and identification of “red flags” about each condition. The CTC asks the patient to describe his or her treatment goals and care plan. Ideally, the patient or a family member puts the goals and care plan in writing in the notebook in the patient’s own words; this strategy makes the goals and plan more meaningful and relevant to the patient. The CTC revisits this information at each encounter with the patient and caregiver.

Patient/family and caregiver engagement are crucial to the success of the initiative with frail, older patients.8,9 One 1998 study indicated that patient and caregiver satisfaction with home health services correlated with receiving information from the home health staff regarding medications, equipment and supplies, and self-care; further, the degree of caregiver burden was inversely related to receipt of information from the home health staff.10 The engagement required for the patient and caregiver to record the necessary information in the care transitions tool improves the likelihood of their understanding and adhering to lifestyle, behavioral, and medication recommendations.

At the time of hospital discharge, the CTC arranges the patient’s appointment with the primary care physician and records this in the patient’s notebook. The date and time for the patient’s first home nursing visit is also arranged and recorded so that the patient and caregiver know exactly when to expect that visit.

Medication management

The first home nursing visit typically occurs within 24 hours of hospital discharge. During this visit, the home health nurse reviews the Bridge to Healthy Living tool and uses it to guide care in partnership with the patient, enhancing adherence to the care plan. The nurse reviews the patient’s medications, checks them against the hospital discharge list, and then asks about other medications that might be in a cabinet or the refrigerator that the patient might be taking. At each subsequent visit, the nurse reviews the medication list and adjusts it as indicated if the patient’s physicians have changed any medication. If there has been a medication change, this is communicated by the home health nurse to all physicians caring for the patient.

The initial home nursing visit includes an environmental assessment with observation for hazards that could increase the risk for falls or other injury. The nurse also reinforces coaching on medications, red flags, and dietary or lifestyle issues that was begun by the CTC in the hospital.

Physician engagement

Physician engagement in the transition process is critical to reducing avoidable rehospitalizations. Coleman’s work has emphasized the need for the patient to follow up with his or her primary care physician within 1 week of discharge; but too frequently, the primary care physician is unaware that the patient was admitted to the hospital, and discharge summaries may take weeks to arrive. The care transitions initiative is a relationship-based, physician-led care delivery model in which the CTC serves as the funnel for information-sharing among all providers engaged with the patient. Although the CTC functions as the information manager, a successful transition requires an unprecedented level of cooperation among physicians and other health care providers. Health care is changing; outcomes must improve and costs must decrease. Therefore, this level of cooperation is no longer optional, but has become mandatory.

OUTCOMES

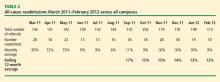

The primary outcome measure in the care transitions initiative was the rate of nonelective rehospitalization related to any cause, recurrence, or exacerbation of the index hospitalization diagnosis-related group, comorbid conditions, or new health problems. The Amedisys care transitions initiative was tested in three large, academic institutions in the northeast and southeast United States for 12 months. The 12-month average readmission rate (as calculated month by month) in the last 6 months of the study decreased from 17% to 12% (Table 2). During this period both patient and physician satisfaction were enhanced, according to internal survey data.

CALL TO ACTION

Americans want to live in their own homes as long as possible. In fact, when elderly Americans are admitted to a hospital, what is actually occurring is that they are being “discharged from their communities.”11 A health care delivery system that provides a true patient-centered approach to care recognizes that this situation often compounds issues of health care costs and quality. Adequate transitional care can provide simpler and more cost-effective options. If a CTC and follow-up care at home had been provided to Mrs. Smith and her daughter upon the first emergency room visit earlier in the year (see “Case study,” page e-S2), Mrs. Smith might have avoided multiple costly readmissions. Each member of the home health industry and its partners should be required to provide a basic set of evidence-based care transition elements to the patients they serve. By coordinating care at the time of discharge, some of the fragmentation that has become embedded in our system might be overcome.

- Life expectancy—United States. Data360 Web site. http://www.data360.org/dsg.aspx?Data_Set_Group_Id=195. Accessed August 15, 2012.

- Aging statistics. Administration on Aging Web site. http://www.aoa.gov/aoaroot/aging_statistics/index.aspx. Updated September 1, 2011. Accessed August 15, 2012.

- Report to the Congress. Medicare Payment Policy. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission Web site. http://medpac.gov/documents/Mar08_EntireReport.pdf. Published March 2008. Accessed August 15, 2012.

- Coleman EA, Min S, Chomiak A, Kramer AM. Post-hospital care transitions: patterns, complications, and risk identification. Health Serv Res 2004; 39:1449–1465.

- Quality initiatives—general information. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. http://www.cms.hhs.gov/QualityInitiativesGenInfo/15_MQMS.asp. Updated April 4, 2012. Accessed August 15, 2012.

- Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166:1822–1828.

- van Walraven C, Bennett C, Jennings A, Austin PC, Forster AJ. Proportion of hospital readmissions deemed avoidable: a systematic review [published online ahead of print]. CMAJ 2011; 183:E391–E402. 10.1503/cmaj.101860

- Naylor MD, Brooten D, Campbell R, et al. Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow-up of hospitalized elders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 1999; 281:613–620.

- Coleman EA, Smith JD, Frank JC, Min S, Parry C, Kramer AM. Preparing patients and caregivers to participate in care delivered across settings: the Care Transitions Intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004; 52:1817–1825.

- Weaver FM, Perloff L, Waters T. Patients’ and caregivers’ transition from hospital to home: needs and recommendations. Home Health Care Serv Q 1998; 17:27–48.

- Fleming MO. The value of healthcare at home. Presented at: American Osteopathic Visiting Professorship, Louisiana State University Health System; April 12, 2012; New Orleans, LA.

The US health care system faces many challenges. Quality, cost, access, fragmentation, and misalignment of incentives are only a few. The most pressing dilemma is how this challenged system will handle the demographic wave of aging Americans. Our 21st-century population is living longer with a greater chronic disease burden than its predecessors, and has reasonable expectations of quality care. No setting portrays this challenge more clearly than that of transition: the transfer of a patient and his or her care from the hospital or facility setting to the home. Addressing this challenge requires that we adopt a set of proven effective interventions that can improve quality of care, meet the needs of the patients and families we serve, and lower the staggering economic and social burden of preventable hospital readmissions.

The Medicare system, designed in 1965, has not kept pace with the needs and challenges of the rapidly aging US population. Further, the system is not aligned with today’s—and tomorrow’s—needs. In 1965, average life expectancy for Americans was 70 years; by 2020, that average is predicted to be nearly 80 years.1 In 2000, one in eight Americans, or 12% of the US population, was aged 65 years or older.2 It is expected that by 2030, this group will represent 19% of the population. This means that in 2030, some 72 million Americans will be aged 65 or older—more than twice the number in this age group in 2000.2

The 1965 health care system focused on treating acute disease, but the health care system of the 21st century must effectively manage chronic disease. The burden of chronic disease is especially significant for aging patients, who are likely to be under the care of multiple providers and require multiple medications and ever-higher levels of professional care. The management and sequelae of chronic diseases frequently lead to impaired quality of life as well as significant expense for Medicare.

The discrepancy between our health care system and unmet needs is acutely obvious at the time of hospital discharge. In fact, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) has stated that this burden of unmet needs at hospital discharge is primarily driven by hospital admissions and readmissions.3 Thirty-day readmission rates among older Medicare beneficiaries range from 15% to 25%.4–6 Disagreement persists regarding what percentage of hospital readmissions within 30 days might be preventable. A systematic review of 34 studies has reported that, on average, 27% of readmissions were preventable.7

To address the challenge of avoidable readmissions, our home health and hospice care organization, Amedisys, Inc., developed a care transitions initiative designed to improve quality of life, improve patient outcomes, and prevent unnecessary hospital readmissions. This article, which includes an illustrative case study, describes the initiative and the outcomes observed during its first 12 months of testing.

CASE STUDY

Mrs. Smith is 84 years old and lives alone in her home. She suffers from mild to moderate dementia and heart failure (HF). Mrs. Smith’s daughter is her main caregiver, talking to Mrs. Smith multiple times a day and stopping by Mrs. Smith’s house at least two to three times a week.

Mrs. Smith was admitted to the hospital after her daughter brought her to the emergency department over the weekend because of shortness of breath. This was her third visit to the emergency department within the past year, with each visit resulting in a hospitalization. Because of questions regarding her homebound status, home health was not considered part of the care plan during either of Mrs. Smith’s previous discharges.

Hospitalists made rounds over the weekend and notified Mrs. Smith that she would be released on Tuesday morning; because of her weakness and disorientation, the hospitalist issued an order for home health and a prescription for a new HF medication. Upon hearing the news on Monday of the planned discharge, Mrs. Smith and her daughter selected the home health provider they wished to use and, within the next few hours, a care transitions coordinator (CTC) visited them in the hospital.

The CTC, a registered nurse, talked with Mrs. Smith about her illness, educating her on the impact of diet on her condition and the medications she takes, including the new medication prescribed by the hospitalist. Most importantly, the CTC talked to Mrs. Smith about her personal goals during her recovery. For example, Mrs. Smith loves to visit her granddaughter, where she spends hours at a time watching her great-grandchildren play. Mrs. Smith wants to control her HF so that she can continue these visits that bring her such joy.

Mrs. Smith’s daughter asked the CTC if she would make Mrs. Smith’s primary care physician aware of the change in medication and schedule an appointment within the next week. The CTC did so before Mrs. Smith left the hospital. She also completed a primary care discharge notification, which documented Mrs. Smith’s discharge diagnoses, discharge medications, important test results, and the date of the appointment, and e-faxed it to Mrs. Smith’s primary care physician. The CTC also communicated with the home health nurse who would care for Mrs. Smith following discharge, reviewing her clinical needs as well as her personal goals.

Mrs. Smith’s daughter was present when the home health nurse conducted the admission and in-home assessment. The home health nurse educated both Mrs. Smith and her daughter about foods that might exacerbate HF, reinforcing the education started in the hospital by the CTC. In the course of this conversation, Mrs. Smith’s daughter realized that her mother had been eating popcorn late at night when she could not sleep. The CTC helped both mother and daughter to understand that the salt in her popcorn could have an impact on Mrs. Smith’s illness that would likely result in rehospitalization and an increase in medication dosage; this educational process enhanced the patient’s understanding of her disease and likely reduced the chances of her emergency department–rehospitalization cycle continuing.

INTERVENTION

The design of the Amedisys care transitions initiative is based on work by Naylor et al8 and Coleman et al,6 who are recognized in the home health industry for their models of intervention at the time of hospital discharge. The Amedisys initiative’s objective is to prevent avoidable readmissions through patient and caregiver health coaching and care coordination, starting in the hospital and continuing through completion of the patient’s home health plan of care. Table 1 compares the essential interventions of the Naylor and Coleman models with those of the Amedisys initiative.

The Amedisys initiative includes these specific interventions:

- use of a CTC;

- early engagement of the patient, caregiver, and family with condition-specific coaching;

- careful medication management; and

- physician engagement with scheduling and reminders of physician visits early in the transition process.

Using a care transitions coordinator

Amedisys has placed CTCs in the acute care facilities that it serves. The CTC’s responsibility is to ensure that patients transition safely home from the acute care setting. With fragmentation of care, patients are most vulnerable during the initial few days postdischarge; this is particularly true for the frail elderly. Consequently, the CTC meets with the patient and caregiver as soon as possible upon his or her referral to Amedisys to plan the transition home from the facility and determine the resources needed once home. The CTC becomes the patient’s “touchpoint” for any questions or problems that arise between the time of discharge and the time when an Amedisys nurse visits the patient’s home.

Early engagement and coaching

The CTC uses a proprietary tool, Bridge to Healt0hy Living, to begin the process of early engagement, education, and coaching. This bound notebook is personalized for each patient with the CTC’s name and 24-hour phone contact information. The CTC records the patient’s diagnoses as well as social and economic barriers that may affect the patient’s outcomes. The diagnoses are written in the notebook along with a list of the patient’s medications that describes what each drug is for, its exact dosage, and instructions for taking it.

Coaching focuses on the patient’s diagnoses and capabilities, with discussion of diet and lifestyle needs and identification of “red flags” about each condition. The CTC asks the patient to describe his or her treatment goals and care plan. Ideally, the patient or a family member puts the goals and care plan in writing in the notebook in the patient’s own words; this strategy makes the goals and plan more meaningful and relevant to the patient. The CTC revisits this information at each encounter with the patient and caregiver.

Patient/family and caregiver engagement are crucial to the success of the initiative with frail, older patients.8,9 One 1998 study indicated that patient and caregiver satisfaction with home health services correlated with receiving information from the home health staff regarding medications, equipment and supplies, and self-care; further, the degree of caregiver burden was inversely related to receipt of information from the home health staff.10 The engagement required for the patient and caregiver to record the necessary information in the care transitions tool improves the likelihood of their understanding and adhering to lifestyle, behavioral, and medication recommendations.

At the time of hospital discharge, the CTC arranges the patient’s appointment with the primary care physician and records this in the patient’s notebook. The date and time for the patient’s first home nursing visit is also arranged and recorded so that the patient and caregiver know exactly when to expect that visit.

Medication management

The first home nursing visit typically occurs within 24 hours of hospital discharge. During this visit, the home health nurse reviews the Bridge to Healthy Living tool and uses it to guide care in partnership with the patient, enhancing adherence to the care plan. The nurse reviews the patient’s medications, checks them against the hospital discharge list, and then asks about other medications that might be in a cabinet or the refrigerator that the patient might be taking. At each subsequent visit, the nurse reviews the medication list and adjusts it as indicated if the patient’s physicians have changed any medication. If there has been a medication change, this is communicated by the home health nurse to all physicians caring for the patient.

The initial home nursing visit includes an environmental assessment with observation for hazards that could increase the risk for falls or other injury. The nurse also reinforces coaching on medications, red flags, and dietary or lifestyle issues that was begun by the CTC in the hospital.

Physician engagement

Physician engagement in the transition process is critical to reducing avoidable rehospitalizations. Coleman’s work has emphasized the need for the patient to follow up with his or her primary care physician within 1 week of discharge; but too frequently, the primary care physician is unaware that the patient was admitted to the hospital, and discharge summaries may take weeks to arrive. The care transitions initiative is a relationship-based, physician-led care delivery model in which the CTC serves as the funnel for information-sharing among all providers engaged with the patient. Although the CTC functions as the information manager, a successful transition requires an unprecedented level of cooperation among physicians and other health care providers. Health care is changing; outcomes must improve and costs must decrease. Therefore, this level of cooperation is no longer optional, but has become mandatory.

OUTCOMES

The primary outcome measure in the care transitions initiative was the rate of nonelective rehospitalization related to any cause, recurrence, or exacerbation of the index hospitalization diagnosis-related group, comorbid conditions, or new health problems. The Amedisys care transitions initiative was tested in three large, academic institutions in the northeast and southeast United States for 12 months. The 12-month average readmission rate (as calculated month by month) in the last 6 months of the study decreased from 17% to 12% (Table 2). During this period both patient and physician satisfaction were enhanced, according to internal survey data.

CALL TO ACTION

Americans want to live in their own homes as long as possible. In fact, when elderly Americans are admitted to a hospital, what is actually occurring is that they are being “discharged from their communities.”11 A health care delivery system that provides a true patient-centered approach to care recognizes that this situation often compounds issues of health care costs and quality. Adequate transitional care can provide simpler and more cost-effective options. If a CTC and follow-up care at home had been provided to Mrs. Smith and her daughter upon the first emergency room visit earlier in the year (see “Case study,” page e-S2), Mrs. Smith might have avoided multiple costly readmissions. Each member of the home health industry and its partners should be required to provide a basic set of evidence-based care transition elements to the patients they serve. By coordinating care at the time of discharge, some of the fragmentation that has become embedded in our system might be overcome.

The US health care system faces many challenges. Quality, cost, access, fragmentation, and misalignment of incentives are only a few. The most pressing dilemma is how this challenged system will handle the demographic wave of aging Americans. Our 21st-century population is living longer with a greater chronic disease burden than its predecessors, and has reasonable expectations of quality care. No setting portrays this challenge more clearly than that of transition: the transfer of a patient and his or her care from the hospital or facility setting to the home. Addressing this challenge requires that we adopt a set of proven effective interventions that can improve quality of care, meet the needs of the patients and families we serve, and lower the staggering economic and social burden of preventable hospital readmissions.

The Medicare system, designed in 1965, has not kept pace with the needs and challenges of the rapidly aging US population. Further, the system is not aligned with today’s—and tomorrow’s—needs. In 1965, average life expectancy for Americans was 70 years; by 2020, that average is predicted to be nearly 80 years.1 In 2000, one in eight Americans, or 12% of the US population, was aged 65 years or older.2 It is expected that by 2030, this group will represent 19% of the population. This means that in 2030, some 72 million Americans will be aged 65 or older—more than twice the number in this age group in 2000.2

The 1965 health care system focused on treating acute disease, but the health care system of the 21st century must effectively manage chronic disease. The burden of chronic disease is especially significant for aging patients, who are likely to be under the care of multiple providers and require multiple medications and ever-higher levels of professional care. The management and sequelae of chronic diseases frequently lead to impaired quality of life as well as significant expense for Medicare.

The discrepancy between our health care system and unmet needs is acutely obvious at the time of hospital discharge. In fact, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) has stated that this burden of unmet needs at hospital discharge is primarily driven by hospital admissions and readmissions.3 Thirty-day readmission rates among older Medicare beneficiaries range from 15% to 25%.4–6 Disagreement persists regarding what percentage of hospital readmissions within 30 days might be preventable. A systematic review of 34 studies has reported that, on average, 27% of readmissions were preventable.7

To address the challenge of avoidable readmissions, our home health and hospice care organization, Amedisys, Inc., developed a care transitions initiative designed to improve quality of life, improve patient outcomes, and prevent unnecessary hospital readmissions. This article, which includes an illustrative case study, describes the initiative and the outcomes observed during its first 12 months of testing.

CASE STUDY

Mrs. Smith is 84 years old and lives alone in her home. She suffers from mild to moderate dementia and heart failure (HF). Mrs. Smith’s daughter is her main caregiver, talking to Mrs. Smith multiple times a day and stopping by Mrs. Smith’s house at least two to three times a week.

Mrs. Smith was admitted to the hospital after her daughter brought her to the emergency department over the weekend because of shortness of breath. This was her third visit to the emergency department within the past year, with each visit resulting in a hospitalization. Because of questions regarding her homebound status, home health was not considered part of the care plan during either of Mrs. Smith’s previous discharges.

Hospitalists made rounds over the weekend and notified Mrs. Smith that she would be released on Tuesday morning; because of her weakness and disorientation, the hospitalist issued an order for home health and a prescription for a new HF medication. Upon hearing the news on Monday of the planned discharge, Mrs. Smith and her daughter selected the home health provider they wished to use and, within the next few hours, a care transitions coordinator (CTC) visited them in the hospital.

The CTC, a registered nurse, talked with Mrs. Smith about her illness, educating her on the impact of diet on her condition and the medications she takes, including the new medication prescribed by the hospitalist. Most importantly, the CTC talked to Mrs. Smith about her personal goals during her recovery. For example, Mrs. Smith loves to visit her granddaughter, where she spends hours at a time watching her great-grandchildren play. Mrs. Smith wants to control her HF so that she can continue these visits that bring her such joy.

Mrs. Smith’s daughter asked the CTC if she would make Mrs. Smith’s primary care physician aware of the change in medication and schedule an appointment within the next week. The CTC did so before Mrs. Smith left the hospital. She also completed a primary care discharge notification, which documented Mrs. Smith’s discharge diagnoses, discharge medications, important test results, and the date of the appointment, and e-faxed it to Mrs. Smith’s primary care physician. The CTC also communicated with the home health nurse who would care for Mrs. Smith following discharge, reviewing her clinical needs as well as her personal goals.

Mrs. Smith’s daughter was present when the home health nurse conducted the admission and in-home assessment. The home health nurse educated both Mrs. Smith and her daughter about foods that might exacerbate HF, reinforcing the education started in the hospital by the CTC. In the course of this conversation, Mrs. Smith’s daughter realized that her mother had been eating popcorn late at night when she could not sleep. The CTC helped both mother and daughter to understand that the salt in her popcorn could have an impact on Mrs. Smith’s illness that would likely result in rehospitalization and an increase in medication dosage; this educational process enhanced the patient’s understanding of her disease and likely reduced the chances of her emergency department–rehospitalization cycle continuing.

INTERVENTION

The design of the Amedisys care transitions initiative is based on work by Naylor et al8 and Coleman et al,6 who are recognized in the home health industry for their models of intervention at the time of hospital discharge. The Amedisys initiative’s objective is to prevent avoidable readmissions through patient and caregiver health coaching and care coordination, starting in the hospital and continuing through completion of the patient’s home health plan of care. Table 1 compares the essential interventions of the Naylor and Coleman models with those of the Amedisys initiative.

The Amedisys initiative includes these specific interventions:

- use of a CTC;

- early engagement of the patient, caregiver, and family with condition-specific coaching;

- careful medication management; and

- physician engagement with scheduling and reminders of physician visits early in the transition process.

Using a care transitions coordinator

Amedisys has placed CTCs in the acute care facilities that it serves. The CTC’s responsibility is to ensure that patients transition safely home from the acute care setting. With fragmentation of care, patients are most vulnerable during the initial few days postdischarge; this is particularly true for the frail elderly. Consequently, the CTC meets with the patient and caregiver as soon as possible upon his or her referral to Amedisys to plan the transition home from the facility and determine the resources needed once home. The CTC becomes the patient’s “touchpoint” for any questions or problems that arise between the time of discharge and the time when an Amedisys nurse visits the patient’s home.

Early engagement and coaching

The CTC uses a proprietary tool, Bridge to Healt0hy Living, to begin the process of early engagement, education, and coaching. This bound notebook is personalized for each patient with the CTC’s name and 24-hour phone contact information. The CTC records the patient’s diagnoses as well as social and economic barriers that may affect the patient’s outcomes. The diagnoses are written in the notebook along with a list of the patient’s medications that describes what each drug is for, its exact dosage, and instructions for taking it.

Coaching focuses on the patient’s diagnoses and capabilities, with discussion of diet and lifestyle needs and identification of “red flags” about each condition. The CTC asks the patient to describe his or her treatment goals and care plan. Ideally, the patient or a family member puts the goals and care plan in writing in the notebook in the patient’s own words; this strategy makes the goals and plan more meaningful and relevant to the patient. The CTC revisits this information at each encounter with the patient and caregiver.

Patient/family and caregiver engagement are crucial to the success of the initiative with frail, older patients.8,9 One 1998 study indicated that patient and caregiver satisfaction with home health services correlated with receiving information from the home health staff regarding medications, equipment and supplies, and self-care; further, the degree of caregiver burden was inversely related to receipt of information from the home health staff.10 The engagement required for the patient and caregiver to record the necessary information in the care transitions tool improves the likelihood of their understanding and adhering to lifestyle, behavioral, and medication recommendations.

At the time of hospital discharge, the CTC arranges the patient’s appointment with the primary care physician and records this in the patient’s notebook. The date and time for the patient’s first home nursing visit is also arranged and recorded so that the patient and caregiver know exactly when to expect that visit.

Medication management

The first home nursing visit typically occurs within 24 hours of hospital discharge. During this visit, the home health nurse reviews the Bridge to Healthy Living tool and uses it to guide care in partnership with the patient, enhancing adherence to the care plan. The nurse reviews the patient’s medications, checks them against the hospital discharge list, and then asks about other medications that might be in a cabinet or the refrigerator that the patient might be taking. At each subsequent visit, the nurse reviews the medication list and adjusts it as indicated if the patient’s physicians have changed any medication. If there has been a medication change, this is communicated by the home health nurse to all physicians caring for the patient.

The initial home nursing visit includes an environmental assessment with observation for hazards that could increase the risk for falls or other injury. The nurse also reinforces coaching on medications, red flags, and dietary or lifestyle issues that was begun by the CTC in the hospital.

Physician engagement

Physician engagement in the transition process is critical to reducing avoidable rehospitalizations. Coleman’s work has emphasized the need for the patient to follow up with his or her primary care physician within 1 week of discharge; but too frequently, the primary care physician is unaware that the patient was admitted to the hospital, and discharge summaries may take weeks to arrive. The care transitions initiative is a relationship-based, physician-led care delivery model in which the CTC serves as the funnel for information-sharing among all providers engaged with the patient. Although the CTC functions as the information manager, a successful transition requires an unprecedented level of cooperation among physicians and other health care providers. Health care is changing; outcomes must improve and costs must decrease. Therefore, this level of cooperation is no longer optional, but has become mandatory.

OUTCOMES

The primary outcome measure in the care transitions initiative was the rate of nonelective rehospitalization related to any cause, recurrence, or exacerbation of the index hospitalization diagnosis-related group, comorbid conditions, or new health problems. The Amedisys care transitions initiative was tested in three large, academic institutions in the northeast and southeast United States for 12 months. The 12-month average readmission rate (as calculated month by month) in the last 6 months of the study decreased from 17% to 12% (Table 2). During this period both patient and physician satisfaction were enhanced, according to internal survey data.

CALL TO ACTION

Americans want to live in their own homes as long as possible. In fact, when elderly Americans are admitted to a hospital, what is actually occurring is that they are being “discharged from their communities.”11 A health care delivery system that provides a true patient-centered approach to care recognizes that this situation often compounds issues of health care costs and quality. Adequate transitional care can provide simpler and more cost-effective options. If a CTC and follow-up care at home had been provided to Mrs. Smith and her daughter upon the first emergency room visit earlier in the year (see “Case study,” page e-S2), Mrs. Smith might have avoided multiple costly readmissions. Each member of the home health industry and its partners should be required to provide a basic set of evidence-based care transition elements to the patients they serve. By coordinating care at the time of discharge, some of the fragmentation that has become embedded in our system might be overcome.

- Life expectancy—United States. Data360 Web site. http://www.data360.org/dsg.aspx?Data_Set_Group_Id=195. Accessed August 15, 2012.

- Aging statistics. Administration on Aging Web site. http://www.aoa.gov/aoaroot/aging_statistics/index.aspx. Updated September 1, 2011. Accessed August 15, 2012.

- Report to the Congress. Medicare Payment Policy. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission Web site. http://medpac.gov/documents/Mar08_EntireReport.pdf. Published March 2008. Accessed August 15, 2012.

- Coleman EA, Min S, Chomiak A, Kramer AM. Post-hospital care transitions: patterns, complications, and risk identification. Health Serv Res 2004; 39:1449–1465.

- Quality initiatives—general information. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. http://www.cms.hhs.gov/QualityInitiativesGenInfo/15_MQMS.asp. Updated April 4, 2012. Accessed August 15, 2012.

- Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166:1822–1828.

- van Walraven C, Bennett C, Jennings A, Austin PC, Forster AJ. Proportion of hospital readmissions deemed avoidable: a systematic review [published online ahead of print]. CMAJ 2011; 183:E391–E402. 10.1503/cmaj.101860

- Naylor MD, Brooten D, Campbell R, et al. Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow-up of hospitalized elders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 1999; 281:613–620.

- Coleman EA, Smith JD, Frank JC, Min S, Parry C, Kramer AM. Preparing patients and caregivers to participate in care delivered across settings: the Care Transitions Intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004; 52:1817–1825.

- Weaver FM, Perloff L, Waters T. Patients’ and caregivers’ transition from hospital to home: needs and recommendations. Home Health Care Serv Q 1998; 17:27–48.

- Fleming MO. The value of healthcare at home. Presented at: American Osteopathic Visiting Professorship, Louisiana State University Health System; April 12, 2012; New Orleans, LA.

- Life expectancy—United States. Data360 Web site. http://www.data360.org/dsg.aspx?Data_Set_Group_Id=195. Accessed August 15, 2012.

- Aging statistics. Administration on Aging Web site. http://www.aoa.gov/aoaroot/aging_statistics/index.aspx. Updated September 1, 2011. Accessed August 15, 2012.

- Report to the Congress. Medicare Payment Policy. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission Web site. http://medpac.gov/documents/Mar08_EntireReport.pdf. Published March 2008. Accessed August 15, 2012.

- Coleman EA, Min S, Chomiak A, Kramer AM. Post-hospital care transitions: patterns, complications, and risk identification. Health Serv Res 2004; 39:1449–1465.

- Quality initiatives—general information. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. http://www.cms.hhs.gov/QualityInitiativesGenInfo/15_MQMS.asp. Updated April 4, 2012. Accessed August 15, 2012.

- Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166:1822–1828.

- van Walraven C, Bennett C, Jennings A, Austin PC, Forster AJ. Proportion of hospital readmissions deemed avoidable: a systematic review [published online ahead of print]. CMAJ 2011; 183:E391–E402. 10.1503/cmaj.101860

- Naylor MD, Brooten D, Campbell R, et al. Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow-up of hospitalized elders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 1999; 281:613–620.

- Coleman EA, Smith JD, Frank JC, Min S, Parry C, Kramer AM. Preparing patients and caregivers to participate in care delivered across settings: the Care Transitions Intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004; 52:1817–1825.

- Weaver FM, Perloff L, Waters T. Patients’ and caregivers’ transition from hospital to home: needs and recommendations. Home Health Care Serv Q 1998; 17:27–48.

- Fleming MO. The value of healthcare at home. Presented at: American Osteopathic Visiting Professorship, Louisiana State University Health System; April 12, 2012; New Orleans, LA.