User login

CERVICAL DISEASE

The author is a consultant to Merck & Co., Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, and Roche Molecular Diagnostics.

New data enhance our knowledge in two critical areas previously covered in this update: the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine and HPV DNA testing for cervical cancer screening.

Among findings published in 2007:

- results of phase-3 trials of the quadrivalent and bivalent HPV vaccines, which confirm the remarkable efficacy seen in phase-2 trials among women not previously exposed to the vaccine-targeted HPV types

- three large randomized cervical cancer screening trials from Canada, Sweden, and the Netherlands, which confirm the superiority of cervical cancer screening programs that add HPV DNA testing to cytology in women 30 years and older

- the much-anticipated update of consensus guidelines on the management of women with abnormal cervical cancer screening tests.

Efficacy of HPV vaccine approaches 100% in targeted population

Future II Study Group. Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent high-grade cervical lesions. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1915–1927.

Garland SM, Hernandez-Avila M, Wheeler CM, et al. Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent anogenital diseases. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1928–1943.

These trials, referred to as FUTURE I and II, were multicenter, multicountry, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trials of the quadrivalent vaccine (Gardasil) that enrolled women 15 to 26 years of age (TABLE).1 Participants were followed for an average of 3 years after receiving the first of the series of three vaccinations. The efficacy of the vaccine at preventing high-grade neoplasia associated with vaccine-targeted HPV types (HPV 6, 11, 16, and 18) was 98% and 100% in the two trials among the “per-protocol,” susceptible population. That population was defined as women who had no evidence of exposure to the targeted HPV types, according to serologic or HPV DNA testing during the first 7 months of the trials, and who received all three vaccinations. This population is a good indicator of how the vaccine will work in adolescents who are not yet sexually active (TABLE).

Efficacy is high in key phase-3 trials of the HPV vaccine

| AUTHORS | HPV TYPES TARGETED | WOMEN (N) | FOLLOW-UP | ENDPOINT | VACCINE EFFICACY (%)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Garland et al (FUTURE I) (2007) | 6, 11, 16, 18 | 4,499 | 3 years | CIN 2+ and adenocarcinoma in situ | 100 (95% CI, 94–100) |

| FUTURE II Study Group (2007) | 6, 11, 16, 18 | 12,167 | 3 years | CIN 2+ and adenocarcinoma in situ | 98 (95% CI, 86–100) |

| Joura et al1 (2007) | 6, 11, 16, 18 | 15,596 | 3 years | Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia 2+ and vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia 2+ | 100 (95% CI, 72–100) |

| Paavonen et al (2007) | 16, 18 | 15,626 | 15 months | CIN 2+ | 90 (95% CI, 53–99) |

| * In women naïve to vaccine-targeted HPV types by serology and HPV DNA testing. | |||||

| CI, confidence interval; CIN, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. | |||||

The vaccine was less effective in the “intention-to-treat” population that included all women enrolled in the study regardless of HPV status. At 3 years, the vaccine reduced high-grade neoplasia associated with vaccine-targeted HPV types in this population by only 29% and 50% in the two trials.

When these results were published, some experts expressed concern and questioned the benefit of the vaccines.2 There is no reason for concern, however, because lower short-term efficacy in the intention-to-treat population was expected. Because the current generation of HPV vaccines does not have a measurable therapeutic effect, vaccination will not prevent cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) in women who are already infected with vaccine-targeted HPV types; nor will it cause regression of CIN lesions that are already present when the woman is vaccinated.

There were a number of women already infected with vaccine-targeted HPV types at enrollment in the “intention-to-treat” population. Some of these women developed CIN 2,3 associated with vaccine-targeted HPV strains during the first 18 months of the trial (FIGURE 1). However, with longer follow-up, the cumulative number of cases of CIN 2,3 plateaued in vaccinated women, whereas it continued to rise in the placebo arm. Thus, with longer follow-up, vaccine efficacy will improve. Therefore, both the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommend that all sexually active adolescents and young women be vaccinated through 26 years of age.

Figure 1 Cases of CIN 2,3 eventually plateau in vaccinated women

The graph charts the efficacy of the quadrivalent HPV vaccine in preventing CIN 2,3 in the intention-to-treat population of a phase-3 efficacy trial.

SOURCE: Garland et al. Copyright © 2008 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Bivalent vaccine was 90.4% effective against CIN 2,3

Paavonen J, Jenkins D, Bosch FX, et al. Efficacy of a prophylactic adjuvanted bivalent L1 virus-like-particle vaccine against infection with human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in young women: an interim analysis of a phase III double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369:2161–2170.

This interim analysis of a phase-3 double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the bivalent HPV vaccine (Cervarix), which targets HPV types 16 and 18, also was published last year. It enrolled more than 18,000 women 15 to 25 years old who had a mean length of follow-up of 15 months. The vaccine was 90.4% effective against CIN 2,3 associated with the targeted strains (types 16 and 18), the primary endpoint of the trial (TABLE). There was no significant difference in safety outcome between vaccine and placebo recipients.

This trial is ongoing, with final results expected in approximately 2 years. Based on interim findings, the vaccine has been approved for use in a number of countries, including all 27 European Union nations, and the manufacturer of the vaccine has filed an application for approval with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Screening is more effective when HPV testing is included—or used alone

Bulkmans NW, Berkhof J, Rozendaal L, et al. Human papillomavirus DNA testing for the detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 and cancer: 5-year follow-up of a randomised controlled implementation trial. Lancet. 2007;370:1764–1772.

Naucler P, Ryd W, Törnberg S, et al. Human papillomavirus and Papanicolaou tests to screen for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1589–1597.

Mayrand MH, Duarte-Franco E, Rodrigues I, et al. Human papillomavirus DNA versus Papanicolaou screening tests for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1579–1588.

These major studies compared cytology alone with HPV DNA testing for high-risk strains (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68) and found HPV testing—with or without cytology—to be superior to cytology alone.

In a trial from the Netherlands, Bulkmans and colleagues randomly assigned more than 17,000 women 29 years and older to cytologic screening only or a combination of cytology and HPV DNA testing. After 5 years of follow-up, all women were rescreened using both tests. The baseline screen including a combination of cytology and HPV DNA testing identified 70% more CIN 3 lesions and cancers than did cytology alone. More important, during the subsequent round of screening, CIN 3 lesions and cancers decreased by 55% in the group initially screened with both tests.

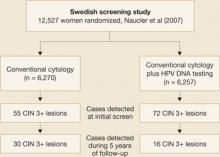

Naucler and associates had similar results in a prospective Swedish trial that randomized women to screening by cytology alone or a combination of cytology and HPV DNA testing. During the initial round of screening, 31% more CIN 3 lesions and cancers were detected in the group screened with both tests (FIGURE 2). In subsequent rounds of screening, 47% fewer CIN 3 lesions or cancers were identified in this group.

Figure 2 Screening protocol that includes HPV DNA testing is superior, large trial confirmsTaken together, these two prospective studies clearly demonstrate that the addition of HPV DNA testing to cytology increases detection of high-grade lesions and reduces the incidence of high-grade neoplasia and cancers detected subsequently.

HPV testing is more sensitive, only slightly less specific, than cytology

In a cross-sectional study from Canada, Mayrand and colleagues compared HPV DNA testing and cytology during a single round of screening in more than 10,000 women. The findings were consistent with those of previous studies showing HPV DNA testing to be significantly more sensitive but somewhat less specific than cytology.3

The sensitivity of HPV testing for CIN 2,3 was 95% (95% confidence interval [CI], 84–100), compared with 55% (95% CI, 34–77) for cytology. Specificity of HPV DNA testing and cytology was 94% and 97%, respectively. When the two tests were used together, sensitivity was 100% and specificity was 93%.

New consensus guidelines clarify screening in special populations

Wright TC Jr, Massad LS, Dunton CJ, Spitzer M, Wilkinson EJ, Solomon D. 2006 consensus guidelines for the management of women with abnormal cervical cancer screening tests. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:346–355.

Wright TC Jr, Massad LS, Dunton CJ, Spitzer M, Wilkinson EJ, Solomon D. 2006 consensus guidelines for the management of women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or adenocarcinoma in situ. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:340–345.

The 2006 consensus guidelines for the management of women with abnormal cervical cancer screening tests clarify management of special populations such as adolescents, postmenopausal women, and patients with cervical adenocarcinoma in situ. Although the 2001 guidelines were widely adopted in the United States as the standard for managing women with abnormal screening tests—more than 500,000 copies were downloaded from Web site of the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP)4—it became apparent after their implementation in a variety of clinical settings that some clarification of the guidelines was needed.

In adolescents, treat abnormalities conservatively

A major theme of the 2006 guidelines is a more conservative approach to adolescent patients (ages 13 to 20 years). Although this population has a very low risk of developing invasive cervical cancer, women 15 to 19 years of age are very likely to be diagnosed with minor cytologic abnormalities such as atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US) and low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL), owing to the very high prevalence of anogenital HPV infection in this age group.

Because most anogenital HPV infections will spontaneously clear, minor cytologic abnormalities are usually of little consequence in adolescents.

Therefore, the 2006 consensus guidelines discourage the use of colposcopy in adolescents who have ASC-US and LSIL. Instead, these patients should be followed with annual repeat cytology and referred to colposcopy only when a high-grade cytologic abnormality is identified or when a low-grade cytologic abnormality persists for 24 months.

HPV testing most informative in older women

The new guidelines expand the clinical indications for HPV DNA testing and provide recommendations for managing different combinations of cytology and HPV test results when screening women 30 years and older. For example, they emphasize the use of HPV DNA testing in postmenopausal women because recent studies clearly demonstrate that the prevalence of high-risk HPV DNA positivity is lower in postmenopausal women with ASC-US or LSIL than in younger women.

Use only FDA-approved HPV tests

With the expanded indications for HPV DNA testing, the new guidelines take pains to point out that HPV test methods that have not been approved by the FDA may not produce findings consistent with approved methods. This is a very important point because many laboratories have started using unapproved testing methods. Although these methods have been validated internally by the laboratories, they have not been through the rigorous evaluation required for FDA approval. The new guidelines therefore state: “Appropriate use of these guidelines requires that laboratories utilize only HPV tests that have been analytically and clinically validated with proven acceptable reproducibility, clinical sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values for cervical cancer and verified precancer (CIN 2,3), as documented by FDA approval and/or publication in peer-reviewed scientific literature.”

The guidelines are accessible online at the ASCCP Web site at www.asccp.org/consensus/cytological.shtml.

1. Joura EA, Leodolter S, Hernandez-Avila M, et al. Efficacy of a quadrivalent prophylactic human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16, and 18) L1 virus-like-particle vaccine against high-grade vulval and vaginal lesions: a combined analysis of three randomised clinical trials. Lancet. 2007;369:1693-1702.

2. Sawaya GF. Smith-McCune K. HPV vaccination—more answers, more questions. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1991-1993.

3. Cuzick J, Clavel C, Petry KU, et al. Overview of the European and North American studies on HPV testing in primary cervical cancer screening. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1095-1101.

4. Wright TC, Jr, Cox JT, Massad LS, Twiggs LB. Wilkinson EJ. 2001 consensus guidelines for the management of women with cervical cytological abnormalities. JAMA .2002;287:2120-2129.

The author is a consultant to Merck & Co., Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, and Roche Molecular Diagnostics.

New data enhance our knowledge in two critical areas previously covered in this update: the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine and HPV DNA testing for cervical cancer screening.

Among findings published in 2007:

- results of phase-3 trials of the quadrivalent and bivalent HPV vaccines, which confirm the remarkable efficacy seen in phase-2 trials among women not previously exposed to the vaccine-targeted HPV types

- three large randomized cervical cancer screening trials from Canada, Sweden, and the Netherlands, which confirm the superiority of cervical cancer screening programs that add HPV DNA testing to cytology in women 30 years and older

- the much-anticipated update of consensus guidelines on the management of women with abnormal cervical cancer screening tests.

Efficacy of HPV vaccine approaches 100% in targeted population

Future II Study Group. Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent high-grade cervical lesions. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1915–1927.

Garland SM, Hernandez-Avila M, Wheeler CM, et al. Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent anogenital diseases. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1928–1943.

These trials, referred to as FUTURE I and II, were multicenter, multicountry, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trials of the quadrivalent vaccine (Gardasil) that enrolled women 15 to 26 years of age (TABLE).1 Participants were followed for an average of 3 years after receiving the first of the series of three vaccinations. The efficacy of the vaccine at preventing high-grade neoplasia associated with vaccine-targeted HPV types (HPV 6, 11, 16, and 18) was 98% and 100% in the two trials among the “per-protocol,” susceptible population. That population was defined as women who had no evidence of exposure to the targeted HPV types, according to serologic or HPV DNA testing during the first 7 months of the trials, and who received all three vaccinations. This population is a good indicator of how the vaccine will work in adolescents who are not yet sexually active (TABLE).

Efficacy is high in key phase-3 trials of the HPV vaccine

| AUTHORS | HPV TYPES TARGETED | WOMEN (N) | FOLLOW-UP | ENDPOINT | VACCINE EFFICACY (%)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Garland et al (FUTURE I) (2007) | 6, 11, 16, 18 | 4,499 | 3 years | CIN 2+ and adenocarcinoma in situ | 100 (95% CI, 94–100) |

| FUTURE II Study Group (2007) | 6, 11, 16, 18 | 12,167 | 3 years | CIN 2+ and adenocarcinoma in situ | 98 (95% CI, 86–100) |

| Joura et al1 (2007) | 6, 11, 16, 18 | 15,596 | 3 years | Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia 2+ and vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia 2+ | 100 (95% CI, 72–100) |

| Paavonen et al (2007) | 16, 18 | 15,626 | 15 months | CIN 2+ | 90 (95% CI, 53–99) |

| * In women naïve to vaccine-targeted HPV types by serology and HPV DNA testing. | |||||

| CI, confidence interval; CIN, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. | |||||

The vaccine was less effective in the “intention-to-treat” population that included all women enrolled in the study regardless of HPV status. At 3 years, the vaccine reduced high-grade neoplasia associated with vaccine-targeted HPV types in this population by only 29% and 50% in the two trials.

When these results were published, some experts expressed concern and questioned the benefit of the vaccines.2 There is no reason for concern, however, because lower short-term efficacy in the intention-to-treat population was expected. Because the current generation of HPV vaccines does not have a measurable therapeutic effect, vaccination will not prevent cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) in women who are already infected with vaccine-targeted HPV types; nor will it cause regression of CIN lesions that are already present when the woman is vaccinated.

There were a number of women already infected with vaccine-targeted HPV types at enrollment in the “intention-to-treat” population. Some of these women developed CIN 2,3 associated with vaccine-targeted HPV strains during the first 18 months of the trial (FIGURE 1). However, with longer follow-up, the cumulative number of cases of CIN 2,3 plateaued in vaccinated women, whereas it continued to rise in the placebo arm. Thus, with longer follow-up, vaccine efficacy will improve. Therefore, both the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommend that all sexually active adolescents and young women be vaccinated through 26 years of age.

Figure 1 Cases of CIN 2,3 eventually plateau in vaccinated women

The graph charts the efficacy of the quadrivalent HPV vaccine in preventing CIN 2,3 in the intention-to-treat population of a phase-3 efficacy trial.

SOURCE: Garland et al. Copyright © 2008 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Bivalent vaccine was 90.4% effective against CIN 2,3

Paavonen J, Jenkins D, Bosch FX, et al. Efficacy of a prophylactic adjuvanted bivalent L1 virus-like-particle vaccine against infection with human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in young women: an interim analysis of a phase III double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369:2161–2170.

This interim analysis of a phase-3 double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the bivalent HPV vaccine (Cervarix), which targets HPV types 16 and 18, also was published last year. It enrolled more than 18,000 women 15 to 25 years old who had a mean length of follow-up of 15 months. The vaccine was 90.4% effective against CIN 2,3 associated with the targeted strains (types 16 and 18), the primary endpoint of the trial (TABLE). There was no significant difference in safety outcome between vaccine and placebo recipients.

This trial is ongoing, with final results expected in approximately 2 years. Based on interim findings, the vaccine has been approved for use in a number of countries, including all 27 European Union nations, and the manufacturer of the vaccine has filed an application for approval with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Screening is more effective when HPV testing is included—or used alone

Bulkmans NW, Berkhof J, Rozendaal L, et al. Human papillomavirus DNA testing for the detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 and cancer: 5-year follow-up of a randomised controlled implementation trial. Lancet. 2007;370:1764–1772.

Naucler P, Ryd W, Törnberg S, et al. Human papillomavirus and Papanicolaou tests to screen for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1589–1597.

Mayrand MH, Duarte-Franco E, Rodrigues I, et al. Human papillomavirus DNA versus Papanicolaou screening tests for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1579–1588.

These major studies compared cytology alone with HPV DNA testing for high-risk strains (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68) and found HPV testing—with or without cytology—to be superior to cytology alone.

In a trial from the Netherlands, Bulkmans and colleagues randomly assigned more than 17,000 women 29 years and older to cytologic screening only or a combination of cytology and HPV DNA testing. After 5 years of follow-up, all women were rescreened using both tests. The baseline screen including a combination of cytology and HPV DNA testing identified 70% more CIN 3 lesions and cancers than did cytology alone. More important, during the subsequent round of screening, CIN 3 lesions and cancers decreased by 55% in the group initially screened with both tests.

Naucler and associates had similar results in a prospective Swedish trial that randomized women to screening by cytology alone or a combination of cytology and HPV DNA testing. During the initial round of screening, 31% more CIN 3 lesions and cancers were detected in the group screened with both tests (FIGURE 2). In subsequent rounds of screening, 47% fewer CIN 3 lesions or cancers were identified in this group.

Figure 2 Screening protocol that includes HPV DNA testing is superior, large trial confirmsTaken together, these two prospective studies clearly demonstrate that the addition of HPV DNA testing to cytology increases detection of high-grade lesions and reduces the incidence of high-grade neoplasia and cancers detected subsequently.

HPV testing is more sensitive, only slightly less specific, than cytology

In a cross-sectional study from Canada, Mayrand and colleagues compared HPV DNA testing and cytology during a single round of screening in more than 10,000 women. The findings were consistent with those of previous studies showing HPV DNA testing to be significantly more sensitive but somewhat less specific than cytology.3

The sensitivity of HPV testing for CIN 2,3 was 95% (95% confidence interval [CI], 84–100), compared with 55% (95% CI, 34–77) for cytology. Specificity of HPV DNA testing and cytology was 94% and 97%, respectively. When the two tests were used together, sensitivity was 100% and specificity was 93%.

New consensus guidelines clarify screening in special populations

Wright TC Jr, Massad LS, Dunton CJ, Spitzer M, Wilkinson EJ, Solomon D. 2006 consensus guidelines for the management of women with abnormal cervical cancer screening tests. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:346–355.

Wright TC Jr, Massad LS, Dunton CJ, Spitzer M, Wilkinson EJ, Solomon D. 2006 consensus guidelines for the management of women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or adenocarcinoma in situ. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:340–345.

The 2006 consensus guidelines for the management of women with abnormal cervical cancer screening tests clarify management of special populations such as adolescents, postmenopausal women, and patients with cervical adenocarcinoma in situ. Although the 2001 guidelines were widely adopted in the United States as the standard for managing women with abnormal screening tests—more than 500,000 copies were downloaded from Web site of the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP)4—it became apparent after their implementation in a variety of clinical settings that some clarification of the guidelines was needed.

In adolescents, treat abnormalities conservatively

A major theme of the 2006 guidelines is a more conservative approach to adolescent patients (ages 13 to 20 years). Although this population has a very low risk of developing invasive cervical cancer, women 15 to 19 years of age are very likely to be diagnosed with minor cytologic abnormalities such as atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US) and low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL), owing to the very high prevalence of anogenital HPV infection in this age group.

Because most anogenital HPV infections will spontaneously clear, minor cytologic abnormalities are usually of little consequence in adolescents.

Therefore, the 2006 consensus guidelines discourage the use of colposcopy in adolescents who have ASC-US and LSIL. Instead, these patients should be followed with annual repeat cytology and referred to colposcopy only when a high-grade cytologic abnormality is identified or when a low-grade cytologic abnormality persists for 24 months.

HPV testing most informative in older women

The new guidelines expand the clinical indications for HPV DNA testing and provide recommendations for managing different combinations of cytology and HPV test results when screening women 30 years and older. For example, they emphasize the use of HPV DNA testing in postmenopausal women because recent studies clearly demonstrate that the prevalence of high-risk HPV DNA positivity is lower in postmenopausal women with ASC-US or LSIL than in younger women.

Use only FDA-approved HPV tests

With the expanded indications for HPV DNA testing, the new guidelines take pains to point out that HPV test methods that have not been approved by the FDA may not produce findings consistent with approved methods. This is a very important point because many laboratories have started using unapproved testing methods. Although these methods have been validated internally by the laboratories, they have not been through the rigorous evaluation required for FDA approval. The new guidelines therefore state: “Appropriate use of these guidelines requires that laboratories utilize only HPV tests that have been analytically and clinically validated with proven acceptable reproducibility, clinical sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values for cervical cancer and verified precancer (CIN 2,3), as documented by FDA approval and/or publication in peer-reviewed scientific literature.”

The guidelines are accessible online at the ASCCP Web site at www.asccp.org/consensus/cytological.shtml.

The author is a consultant to Merck & Co., Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, and Roche Molecular Diagnostics.

New data enhance our knowledge in two critical areas previously covered in this update: the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine and HPV DNA testing for cervical cancer screening.

Among findings published in 2007:

- results of phase-3 trials of the quadrivalent and bivalent HPV vaccines, which confirm the remarkable efficacy seen in phase-2 trials among women not previously exposed to the vaccine-targeted HPV types

- three large randomized cervical cancer screening trials from Canada, Sweden, and the Netherlands, which confirm the superiority of cervical cancer screening programs that add HPV DNA testing to cytology in women 30 years and older

- the much-anticipated update of consensus guidelines on the management of women with abnormal cervical cancer screening tests.

Efficacy of HPV vaccine approaches 100% in targeted population

Future II Study Group. Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent high-grade cervical lesions. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1915–1927.

Garland SM, Hernandez-Avila M, Wheeler CM, et al. Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent anogenital diseases. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1928–1943.

These trials, referred to as FUTURE I and II, were multicenter, multicountry, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trials of the quadrivalent vaccine (Gardasil) that enrolled women 15 to 26 years of age (TABLE).1 Participants were followed for an average of 3 years after receiving the first of the series of three vaccinations. The efficacy of the vaccine at preventing high-grade neoplasia associated with vaccine-targeted HPV types (HPV 6, 11, 16, and 18) was 98% and 100% in the two trials among the “per-protocol,” susceptible population. That population was defined as women who had no evidence of exposure to the targeted HPV types, according to serologic or HPV DNA testing during the first 7 months of the trials, and who received all three vaccinations. This population is a good indicator of how the vaccine will work in adolescents who are not yet sexually active (TABLE).

Efficacy is high in key phase-3 trials of the HPV vaccine

| AUTHORS | HPV TYPES TARGETED | WOMEN (N) | FOLLOW-UP | ENDPOINT | VACCINE EFFICACY (%)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Garland et al (FUTURE I) (2007) | 6, 11, 16, 18 | 4,499 | 3 years | CIN 2+ and adenocarcinoma in situ | 100 (95% CI, 94–100) |

| FUTURE II Study Group (2007) | 6, 11, 16, 18 | 12,167 | 3 years | CIN 2+ and adenocarcinoma in situ | 98 (95% CI, 86–100) |

| Joura et al1 (2007) | 6, 11, 16, 18 | 15,596 | 3 years | Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia 2+ and vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia 2+ | 100 (95% CI, 72–100) |

| Paavonen et al (2007) | 16, 18 | 15,626 | 15 months | CIN 2+ | 90 (95% CI, 53–99) |

| * In women naïve to vaccine-targeted HPV types by serology and HPV DNA testing. | |||||

| CI, confidence interval; CIN, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. | |||||

The vaccine was less effective in the “intention-to-treat” population that included all women enrolled in the study regardless of HPV status. At 3 years, the vaccine reduced high-grade neoplasia associated with vaccine-targeted HPV types in this population by only 29% and 50% in the two trials.

When these results were published, some experts expressed concern and questioned the benefit of the vaccines.2 There is no reason for concern, however, because lower short-term efficacy in the intention-to-treat population was expected. Because the current generation of HPV vaccines does not have a measurable therapeutic effect, vaccination will not prevent cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) in women who are already infected with vaccine-targeted HPV types; nor will it cause regression of CIN lesions that are already present when the woman is vaccinated.

There were a number of women already infected with vaccine-targeted HPV types at enrollment in the “intention-to-treat” population. Some of these women developed CIN 2,3 associated with vaccine-targeted HPV strains during the first 18 months of the trial (FIGURE 1). However, with longer follow-up, the cumulative number of cases of CIN 2,3 plateaued in vaccinated women, whereas it continued to rise in the placebo arm. Thus, with longer follow-up, vaccine efficacy will improve. Therefore, both the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommend that all sexually active adolescents and young women be vaccinated through 26 years of age.

Figure 1 Cases of CIN 2,3 eventually plateau in vaccinated women

The graph charts the efficacy of the quadrivalent HPV vaccine in preventing CIN 2,3 in the intention-to-treat population of a phase-3 efficacy trial.

SOURCE: Garland et al. Copyright © 2008 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Bivalent vaccine was 90.4% effective against CIN 2,3

Paavonen J, Jenkins D, Bosch FX, et al. Efficacy of a prophylactic adjuvanted bivalent L1 virus-like-particle vaccine against infection with human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in young women: an interim analysis of a phase III double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369:2161–2170.

This interim analysis of a phase-3 double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the bivalent HPV vaccine (Cervarix), which targets HPV types 16 and 18, also was published last year. It enrolled more than 18,000 women 15 to 25 years old who had a mean length of follow-up of 15 months. The vaccine was 90.4% effective against CIN 2,3 associated with the targeted strains (types 16 and 18), the primary endpoint of the trial (TABLE). There was no significant difference in safety outcome between vaccine and placebo recipients.

This trial is ongoing, with final results expected in approximately 2 years. Based on interim findings, the vaccine has been approved for use in a number of countries, including all 27 European Union nations, and the manufacturer of the vaccine has filed an application for approval with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Screening is more effective when HPV testing is included—or used alone

Bulkmans NW, Berkhof J, Rozendaal L, et al. Human papillomavirus DNA testing for the detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 and cancer: 5-year follow-up of a randomised controlled implementation trial. Lancet. 2007;370:1764–1772.

Naucler P, Ryd W, Törnberg S, et al. Human papillomavirus and Papanicolaou tests to screen for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1589–1597.

Mayrand MH, Duarte-Franco E, Rodrigues I, et al. Human papillomavirus DNA versus Papanicolaou screening tests for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1579–1588.

These major studies compared cytology alone with HPV DNA testing for high-risk strains (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68) and found HPV testing—with or without cytology—to be superior to cytology alone.

In a trial from the Netherlands, Bulkmans and colleagues randomly assigned more than 17,000 women 29 years and older to cytologic screening only or a combination of cytology and HPV DNA testing. After 5 years of follow-up, all women were rescreened using both tests. The baseline screen including a combination of cytology and HPV DNA testing identified 70% more CIN 3 lesions and cancers than did cytology alone. More important, during the subsequent round of screening, CIN 3 lesions and cancers decreased by 55% in the group initially screened with both tests.

Naucler and associates had similar results in a prospective Swedish trial that randomized women to screening by cytology alone or a combination of cytology and HPV DNA testing. During the initial round of screening, 31% more CIN 3 lesions and cancers were detected in the group screened with both tests (FIGURE 2). In subsequent rounds of screening, 47% fewer CIN 3 lesions or cancers were identified in this group.

Figure 2 Screening protocol that includes HPV DNA testing is superior, large trial confirmsTaken together, these two prospective studies clearly demonstrate that the addition of HPV DNA testing to cytology increases detection of high-grade lesions and reduces the incidence of high-grade neoplasia and cancers detected subsequently.

HPV testing is more sensitive, only slightly less specific, than cytology

In a cross-sectional study from Canada, Mayrand and colleagues compared HPV DNA testing and cytology during a single round of screening in more than 10,000 women. The findings were consistent with those of previous studies showing HPV DNA testing to be significantly more sensitive but somewhat less specific than cytology.3

The sensitivity of HPV testing for CIN 2,3 was 95% (95% confidence interval [CI], 84–100), compared with 55% (95% CI, 34–77) for cytology. Specificity of HPV DNA testing and cytology was 94% and 97%, respectively. When the two tests were used together, sensitivity was 100% and specificity was 93%.

New consensus guidelines clarify screening in special populations

Wright TC Jr, Massad LS, Dunton CJ, Spitzer M, Wilkinson EJ, Solomon D. 2006 consensus guidelines for the management of women with abnormal cervical cancer screening tests. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:346–355.

Wright TC Jr, Massad LS, Dunton CJ, Spitzer M, Wilkinson EJ, Solomon D. 2006 consensus guidelines for the management of women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or adenocarcinoma in situ. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:340–345.

The 2006 consensus guidelines for the management of women with abnormal cervical cancer screening tests clarify management of special populations such as adolescents, postmenopausal women, and patients with cervical adenocarcinoma in situ. Although the 2001 guidelines were widely adopted in the United States as the standard for managing women with abnormal screening tests—more than 500,000 copies were downloaded from Web site of the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP)4—it became apparent after their implementation in a variety of clinical settings that some clarification of the guidelines was needed.

In adolescents, treat abnormalities conservatively

A major theme of the 2006 guidelines is a more conservative approach to adolescent patients (ages 13 to 20 years). Although this population has a very low risk of developing invasive cervical cancer, women 15 to 19 years of age are very likely to be diagnosed with minor cytologic abnormalities such as atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US) and low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL), owing to the very high prevalence of anogenital HPV infection in this age group.

Because most anogenital HPV infections will spontaneously clear, minor cytologic abnormalities are usually of little consequence in adolescents.

Therefore, the 2006 consensus guidelines discourage the use of colposcopy in adolescents who have ASC-US and LSIL. Instead, these patients should be followed with annual repeat cytology and referred to colposcopy only when a high-grade cytologic abnormality is identified or when a low-grade cytologic abnormality persists for 24 months.

HPV testing most informative in older women

The new guidelines expand the clinical indications for HPV DNA testing and provide recommendations for managing different combinations of cytology and HPV test results when screening women 30 years and older. For example, they emphasize the use of HPV DNA testing in postmenopausal women because recent studies clearly demonstrate that the prevalence of high-risk HPV DNA positivity is lower in postmenopausal women with ASC-US or LSIL than in younger women.

Use only FDA-approved HPV tests

With the expanded indications for HPV DNA testing, the new guidelines take pains to point out that HPV test methods that have not been approved by the FDA may not produce findings consistent with approved methods. This is a very important point because many laboratories have started using unapproved testing methods. Although these methods have been validated internally by the laboratories, they have not been through the rigorous evaluation required for FDA approval. The new guidelines therefore state: “Appropriate use of these guidelines requires that laboratories utilize only HPV tests that have been analytically and clinically validated with proven acceptable reproducibility, clinical sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values for cervical cancer and verified precancer (CIN 2,3), as documented by FDA approval and/or publication in peer-reviewed scientific literature.”

The guidelines are accessible online at the ASCCP Web site at www.asccp.org/consensus/cytological.shtml.

1. Joura EA, Leodolter S, Hernandez-Avila M, et al. Efficacy of a quadrivalent prophylactic human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16, and 18) L1 virus-like-particle vaccine against high-grade vulval and vaginal lesions: a combined analysis of three randomised clinical trials. Lancet. 2007;369:1693-1702.

2. Sawaya GF. Smith-McCune K. HPV vaccination—more answers, more questions. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1991-1993.

3. Cuzick J, Clavel C, Petry KU, et al. Overview of the European and North American studies on HPV testing in primary cervical cancer screening. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1095-1101.

4. Wright TC, Jr, Cox JT, Massad LS, Twiggs LB. Wilkinson EJ. 2001 consensus guidelines for the management of women with cervical cytological abnormalities. JAMA .2002;287:2120-2129.

1. Joura EA, Leodolter S, Hernandez-Avila M, et al. Efficacy of a quadrivalent prophylactic human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16, and 18) L1 virus-like-particle vaccine against high-grade vulval and vaginal lesions: a combined analysis of three randomised clinical trials. Lancet. 2007;369:1693-1702.

2. Sawaya GF. Smith-McCune K. HPV vaccination—more answers, more questions. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1991-1993.

3. Cuzick J, Clavel C, Petry KU, et al. Overview of the European and North American studies on HPV testing in primary cervical cancer screening. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1095-1101.

4. Wright TC, Jr, Cox JT, Massad LS, Twiggs LB. Wilkinson EJ. 2001 consensus guidelines for the management of women with cervical cytological abnormalities. JAMA .2002;287:2120-2129.

What you need to know about cervical cancer, genital warts, and HPV

CERVICAL DISEASE

The year 2006 was a busy one for those of us engaged in cervical cancer prevention. The most notable development was approval by the US Food and Drug Administration of the human papillomavirus (HPV) quadrivalent vaccine in June, followed closely by guidelines for its use from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (June) and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (September). Key issues related to the introduction of the HPV vaccine into clinical practice were reviewed in a roundtable discussion in the January 2007 issue of OBG Management.

Therefore, this update will depart, for the moment, from matters related to the vaccine and concentrate on several other critical areas:

- Testing for high-risk HPV types is useful. Large European cervical cancer screening trials confirm a benefit.

- Condoms and oral contraceptives—are they risk modifiers for HPV infection? Answers (“Yes” and “No,” respectively) come from new data.

- Loop electrosurgical excision carries obstetric risks. In fact, all types of excisional procedures produce similar pregnancy-related morbidity.

- Liquid-based cytology may not be superior to conventional cytology. So suggest new studies and a systematic review of the literature.

HPV testing outperforms cytology for screening

Cuzick J, Clavel C, Petry KU, et al. Overview of the European and North American studies on HPV testing in primary cervical cancer screening. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1095–1101.

Ronco G, Segnan N, Giorgi-Rossi P, et al. Human papillomavirus testing and liquid-based cytology: results at recruitment from the new technologies for cervical cancer randomized controlled trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:765–774.

HPV DNA testing is more sensitive than cervical cytology, reduces specificity to only a moderate degree, and performs similarly in different parts of Europe and North America. Those are the findings of a review by Cuzick and colleagues of all recent large European and North American cervical cancer screening studies. To date, 4 large European trials and 1 from Mexico have directly compared HPV testing and cytology in women aged 30 years and older. Combined, these trials have enrolled over 60,000 women. In every study, testing for high-risk types of HPV using the commercially available Hybrid Capture 2 HPV DNA assay had a much higher sensitivity for identifying women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 2,3 or cancer (86–97%) than did cervical cytology (34–74%). Moreover, the combination of cytology and HPV testing had a sensitivity ranging from 94% to 100% in the different studies. The average sensitivity of 98% for the combination of cytology and HPV testing means that there is a less than 1 in 1,000 chance of missing CIN 2,3 or cancer when women are screened with both tests (TABLE 1).

Specificity is reasonable, too

If you worry that using HPV DNA testing in women aged 30 and older will flag too many as high-risk HPV-positive and cause them unnecessary colposcopic examinations or anxiety, here is a comforting finding: The specificity of HPV DNA testing is not as low as many had feared—provided we limit screening to women aged 30 and older. In the 5 trials mentioned, the specificity of HPV DNA testing ranged from 92% to 97%. Even when HPV DNA testing and cytology were used together, the average specificity of the 2 tests combined was 93%. A specificity of 93% means that only 7 of 100 screened women who don’t have CIN 2,3 or cancer will be classified as “positive.”

To put this number into perspective, a 2003 survey of US cytology laboratories found a median rate of abnormal results of 6.9%.1 Therefore, in routine clinical practice, incorporation of HPV DNA testing into screening for women aged 30 and older is not expected to greatly increase the number of women requiring additional follow-up.

The single most important component of management is appropriate counseling. Even though there are fewer of these women than we anticipated, these patients need to be reassured that their risk of having a significant lesion (CIN 2,3 or cancer) is quite low—only about 1 in 20. They also need to know that about two thirds of women—even women aged 30 and older—are HPV-negative when they are retested in 12 months.

In addition, clinicians need to stress that positive HPV status is a risk factor for having or developing cervical disease, not an indication that disease is present. One analogy that patients readily understand is the relationship between other types of health risk factors, such as mild hypertension or mildly elevated serum cholesterol, and disease. These explanations help the patient understand why, in settings where genotyping for HPV 16 and 18 is not available, the best course of action is to wait 12 months and be retested.2

Which test should be used first?

Basic screening principles suggest that, whenever 2 tests are used in combination, the most sensitive test should be used first, with patients who test positive tested again using the second, more specific, test. These principles suggest we should be using HPV testing alone as the initial screening test and limiting the use of cytology to triage HPV-positive women. This sequence of testing could potentially be done in a “reflex” fashion.

The large Italian screening trial by Ronco and colleagues randomized 33,364 women aged 35 to 60 years to 2 different screening strategies: routine conventional cytology or liquid-based cytology with HPV testing.3 In the routine cytology arm, researchers identified only 51 cases of CIN 2,3 or cancer, but in the experimental arm, they identified 75 cases. A breakdown of the initial screening results in the women found to have CIN 2,3 or cancer in the experimental arm shows that cytology adds very little benefit. Only 2 of 75 women with CIN 2,3 or cancer were identified by cytology alone. In contrast, 21 (28%) of the cases of CIN 2,3 or cancer were in women who were high-risk HPV-positive and cytology-negative (TABLE 2).

TABLE 2

How cytology and HPV testing compare: Results from the Italian screening trial

| CYTOLOGY/HPV TEST | TOTAL NO. | CIN 2+ |

|---|---|---|

| ≥ASCUS/positive | 300 | 52 (69%) |

| ≥ASCUS/negative | 594 | 2 (3%) |

| Within normal limits/positive | 885 | 21 (28%) |

| Modified from Ronco G et al | ||

The United States is falling behind other countries in assessing how best to utilize HPV testing for screening. Ongoing trials in The Netherlands, Italy, United Kingdom, Canada, and Finland are evaluating whether cytology can be replaced by HPV DNA testing for screening. Currently, HPV testing is only approved as an adjunct to cytology for cervical cancer screening in the United States, and no similar trials are under way.

OCs not linked to HPV infection, and condoms afford some protection

Vaccarella S, Lazcano-Ponce E, Castro-Garduno JA, et al. Prevalence and determinants of human papillomavirus infection in men attending vasectomy clinics in Mexico. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1934–1939.

Vaccarella S, Franceschi S, Herrero R, et al. Sexual behavior, condom use, and human papillomavirus: pooled analysis of the IARC human papillomavirus prevalence surveys. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:326–333.

Winer RL, Hughes JP, Feng Q, et al. Condom use and the risk of genital human papillomavirus infection in young women. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2645–2654.

No question: Anogenital HPV infections are transmitted almost exclusively through intimate sexual contact.3 The standard markers of sexual exposure, such as the number of sexual partners and the number of partners that one’s partner has had, are key risk factors for infection with HPV. Women often ask whether other factors such as oral contraceptive (OC) use, diet, smoking, and condom use affect their risk for infection. But nonsexual risk factors are difficult to evaluate because the strength of sexual risk factors is so high.

To clarify the role played by non-sexual factors, the International Association for Research on Cancer (IARC) pooled data from multiple HPV prevalence studies involving more than 15,000 women from 14 different areas worldwide. This study clearly indicates that the use of OCs is not associated with HPV infection. Current, former, and never users of OCs all had the same risk of being HPV-positive. Therefore, although OCs are a risk factor for cervical cancer, the elevated risk cannot be explained by an increased susceptibility to HPV infection. This study also found that the menopausal transition had no clear effect on HPV infection.

New data show condoms to be more beneficial than not

Condoms are widely recognized as an effective barrier to the sexual transmission of HIV; their efficacy in blocking the transmission of other sexual diseases is less well documented. Most studies that have evaluated the impact of condom use on HPV infection have failed to find a beneficial effect. This may reflect the fact that condoms are often used inconsistently. In addition, there is a tendency to use condoms when having higher-risk sexual encounters, such as with a new partner.

In a recent study from Seattle, Winer and colleagues followed 82 female university students who first initiated sex while enrolled in the study or within 2 weeks of joining the study. The incidence of HPV infection was 38 per 100 patient-years of follow-up among women whose partners used condoms during all acts of intercourse, compared with 89.3 per 100 patient-years of follow-up among women whose partners used condoms less than 5% of the time. Risk reductions were observed for both high- and low-risk types of HPV.

Condoms also appeared to protect against the development of CIN. There were no cases of CIN during 32 patient-years among women whose partners consistently used condoms, compared with 14 cases of incident CIN during 97 patient-years of follow-up among women whose partners did not use condoms or who used them less consistently.

LEEP may have an adverse obstetric impact

Kyrgiou M, Koliopoulos G, Martin-Hirsch P, Arbyn M, Prendiville W, Paraskevaidis E. Obstetric outcomes after conservative treatment for intraepithelial or early invasive cervical lesions: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2006;367:489–498.

Although most clinicians recognize that cold-knife conization has the potential to cause adverse obstetric outcomes, the same has not been recognized for loop electrosurgical excisional procedures (LEEP). In fact, most of the studies published in the early 1990s showed that LEEP had little impact on obstetric outcomes. Now we know better: Kyrgiou and colleagues conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of the published literature on obstetric outcomes after treatment of CIN lesions, and found that all types of excisional procedures produce similar pregnancy-related morbidities.

LEEP had a significant association with preterm delivery (11% risk in treated women versus 7% in untreated women), low-birth-weight infants (8% in treated women versus 4% in untreated women), and premature rupture of membranes (5% in treated women versus 2% in untreated women). Although there were no significant increases in NICU admissions or perinatal mortality among the offspring of women who had undergone LEEP versus those who had not, nonsignificant increases were observed.

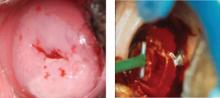

Similar increases in pregnancy-related morbidity were not observed among patients who underwent ablative procedures. This suggests that the amount of tissue that is removed during the LEEP (FIGURE 1) is important. Therefore, when treating CIN 2,3 lesions, especially in young women, consider using an ablative method such as cryotherapy or electrofulguration, unless colposcopy is unsatisfactory or there is a colposcopic or pathologic suspicion that an occult cancer is present.

FIGURE 1 CIN 2,3 and its treatment by LEEP

Is liquid-based cytology as sensitive as we thought?

Davey E, Barratt A, Irwig L, et al. Effect of study design and quality on unsatisfactory rates, cytology classifications, and accuracy in liquid-based versus conventional cervical cytology: a systematic review. Lancet. 2006;367:122–132.

Ronco G, Segnan N, Giorgi-Rossi P, et al. Human papillomavirus testing and liquid-based cytology: results at recruitment from the new technologies for cervical cancer randomized controlled trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:765–774.

Taylor S, Kuhn L, Dupree W, Denny L, De Souza M, Wright TC Jr. Direct comparison of liquid-based and conventional cytology in a South African screening trial. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:957–962.

A major reappraisal of liquid-based cytology (LBC) is under way. When it was first introduced, LBC was believed to provide a significant advantage over conventional cervical cytology in terms of sensitivity for CIN 2,3 or cancer. However, most of the studies that compared the 2 modalities had severe methodological problems. Many utilized historical controls, and most others simply reported increases in the number of cases cytologically diagnosed as squamous intraepithelial lesions (SIL). Very few measured histologic endpoints, and the few studies that did failed to blind the pathologists evaluating the histology to the cytologic findings. Only 1 small study was randomized.

Focus on high-quality studies finds lower sensitivity for LBC

Recently, Davey and colleagues conducted a systematic review of the published literature comparing LBC with conventional cytology. A total of 56 studies were evaluated, 52 of which provided enough information to evaluate differences between the 2 methods in the detection of low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL) and high-grade SIL (HSIL). These 52 studies included more than 1.25 million slides.

None of the studies that were evaluated were judged to be of “ideal quality,” and only 5 were judged to be of “high quality.” When all of the studies are taken into account and combined, there appears to be an increase in the cytologic detection of LSIL and HSIL with the use of LBC. However, further evaluation showed marked differences in the results obtained by studies of different quality.

When only “high-quality” studies are analyzed, there is no indication that LBC increases the detection of HSIL. Davey and colleagues concluded that there is no evidence that LBC reduces the proportion of unsatisfactory slides or outperforms conventional cytology in identifying women with CIN 2,3. They also noted that large randomized trials are needed.

Little difference between modalities in randomized trials

After the systematic review was conducted, 2 large trials comparing LBC with conventional cytology were published. In the first trial, Taylor and colleagues collected samples from South African women and analyzed them in blinded fashion in US laboratories. In their carefully controlled study, 5,652 women received either LBC or conventional cytology (rotated on a 6-month basis), and all women underwent colposcopy and cervical biopsy. No significant difference was observed in the sensitivity of LBC and conventional cytology in the detection of CIN 2,3 or cancer. In fact, there was a nonsignificant increase in sensitivity with conventional cytology, compared with LBC. Positive predictive value was lower with LBC than with conventional cytology. This means that a smaller proportion of women with an abnormal result on LBC had CIN 2,3 or cancer identified at colposcopy than did women who had an abnormal result on conventional cytology.

Similarly, in a large trial from Italy, Ronco and colleagues also failed to find LBC to be more sensitive than conventional cytology. Their trial randomized 33,364 women to LBC or conventional cytology. The use of LBC did not increase the detection of CIN 2,3 or cancer, compared with conventional cytology, but did lead to a dramatic reduction (43%) in positive predictive value due to an increase in the number of abnormal samples.

A similar increase in minor cytologic abnormalities with the use of LBC is now well documented in the United States. According to surveys from the College of American Pathologists, the median percentile reporting rate of LSIL in US laboratories in 2003 was 1.4% for conventional cytology specimens and 2.4% for liquid-based specimens.1

Taken together (TABLE 3), these studies suggest that LBC has no greater sensitivity than conventional cytology and therefore does not solve the problems associated with the poor sensitivity of cervical cytology. However, LBC does have other advantages, the greatest being the availability of residual fluid for “reflex” HPV testing in women with ASC-US and for testing for other pathogens, such as Chlamydia.

TABLE 3

When conventional and liquid-based cytology are compared, the latter isn’t more sensitive

| STUDY | NO. WOMEN | CONVENTIONAL CYTOLOGY | LIQUID-BASED CYTOLOGY | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SENSITIVITY* | PPV* | SENSITIVITY* | PPV* | ||

| Taylor et al | 5,652 | 84%† | 11.4 | 71% | 9.4 |

| Ronco et al | 33,364 | 70% | 11.4 | 74%† | 6.5 |

| PPV=positive predictive value | |||||

| *for detection of CIN 2,3 or cancer | |||||

| †Nonsignificant | |||||

Most cytologists find it easier to evaluate LBC specimens than conventional cytology specimens. Nor is it likely that cytology laboratories will want to switch back to conventional cytology now that the conversion to LBC has taken place.

Dr. Wright reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article.

1. Davey DD, Neal MH, Wilbur DC, Colgan TJ, Styer PE, Mody DR. Bethesda 2001 implementation and reporting rates: 2003 practices of participants in the College of American Pathologists Interlaboratory Comparison Program in Cervicovaginal Cytology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:1224-1229.

2. Wright TC, Jr, Schiffman M, Solomon D, et al. Interim guidance for the use of human papillomavirus DNA testing as an adjunct to cervical cytology for screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:304-309.

3. Burchell AN, Winer RL, de Sanjose S, Franco EL. Chapter 6: Epidemiology and transmission dynamics of genital HPV infection. Vaccine. 2006;24 Suppl 3:S52-61.

The year 2006 was a busy one for those of us engaged in cervical cancer prevention. The most notable development was approval by the US Food and Drug Administration of the human papillomavirus (HPV) quadrivalent vaccine in June, followed closely by guidelines for its use from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (June) and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (September). Key issues related to the introduction of the HPV vaccine into clinical practice were reviewed in a roundtable discussion in the January 2007 issue of OBG Management.

Therefore, this update will depart, for the moment, from matters related to the vaccine and concentrate on several other critical areas:

- Testing for high-risk HPV types is useful. Large European cervical cancer screening trials confirm a benefit.

- Condoms and oral contraceptives—are they risk modifiers for HPV infection? Answers (“Yes” and “No,” respectively) come from new data.

- Loop electrosurgical excision carries obstetric risks. In fact, all types of excisional procedures produce similar pregnancy-related morbidity.

- Liquid-based cytology may not be superior to conventional cytology. So suggest new studies and a systematic review of the literature.

HPV testing outperforms cytology for screening

Cuzick J, Clavel C, Petry KU, et al. Overview of the European and North American studies on HPV testing in primary cervical cancer screening. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1095–1101.

Ronco G, Segnan N, Giorgi-Rossi P, et al. Human papillomavirus testing and liquid-based cytology: results at recruitment from the new technologies for cervical cancer randomized controlled trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:765–774.

HPV DNA testing is more sensitive than cervical cytology, reduces specificity to only a moderate degree, and performs similarly in different parts of Europe and North America. Those are the findings of a review by Cuzick and colleagues of all recent large European and North American cervical cancer screening studies. To date, 4 large European trials and 1 from Mexico have directly compared HPV testing and cytology in women aged 30 years and older. Combined, these trials have enrolled over 60,000 women. In every study, testing for high-risk types of HPV using the commercially available Hybrid Capture 2 HPV DNA assay had a much higher sensitivity for identifying women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 2,3 or cancer (86–97%) than did cervical cytology (34–74%). Moreover, the combination of cytology and HPV testing had a sensitivity ranging from 94% to 100% in the different studies. The average sensitivity of 98% for the combination of cytology and HPV testing means that there is a less than 1 in 1,000 chance of missing CIN 2,3 or cancer when women are screened with both tests (TABLE 1).

Specificity is reasonable, too

If you worry that using HPV DNA testing in women aged 30 and older will flag too many as high-risk HPV-positive and cause them unnecessary colposcopic examinations or anxiety, here is a comforting finding: The specificity of HPV DNA testing is not as low as many had feared—provided we limit screening to women aged 30 and older. In the 5 trials mentioned, the specificity of HPV DNA testing ranged from 92% to 97%. Even when HPV DNA testing and cytology were used together, the average specificity of the 2 tests combined was 93%. A specificity of 93% means that only 7 of 100 screened women who don’t have CIN 2,3 or cancer will be classified as “positive.”

To put this number into perspective, a 2003 survey of US cytology laboratories found a median rate of abnormal results of 6.9%.1 Therefore, in routine clinical practice, incorporation of HPV DNA testing into screening for women aged 30 and older is not expected to greatly increase the number of women requiring additional follow-up.

The single most important component of management is appropriate counseling. Even though there are fewer of these women than we anticipated, these patients need to be reassured that their risk of having a significant lesion (CIN 2,3 or cancer) is quite low—only about 1 in 20. They also need to know that about two thirds of women—even women aged 30 and older—are HPV-negative when they are retested in 12 months.

In addition, clinicians need to stress that positive HPV status is a risk factor for having or developing cervical disease, not an indication that disease is present. One analogy that patients readily understand is the relationship between other types of health risk factors, such as mild hypertension or mildly elevated serum cholesterol, and disease. These explanations help the patient understand why, in settings where genotyping for HPV 16 and 18 is not available, the best course of action is to wait 12 months and be retested.2

Which test should be used first?

Basic screening principles suggest that, whenever 2 tests are used in combination, the most sensitive test should be used first, with patients who test positive tested again using the second, more specific, test. These principles suggest we should be using HPV testing alone as the initial screening test and limiting the use of cytology to triage HPV-positive women. This sequence of testing could potentially be done in a “reflex” fashion.

The large Italian screening trial by Ronco and colleagues randomized 33,364 women aged 35 to 60 years to 2 different screening strategies: routine conventional cytology or liquid-based cytology with HPV testing.3 In the routine cytology arm, researchers identified only 51 cases of CIN 2,3 or cancer, but in the experimental arm, they identified 75 cases. A breakdown of the initial screening results in the women found to have CIN 2,3 or cancer in the experimental arm shows that cytology adds very little benefit. Only 2 of 75 women with CIN 2,3 or cancer were identified by cytology alone. In contrast, 21 (28%) of the cases of CIN 2,3 or cancer were in women who were high-risk HPV-positive and cytology-negative (TABLE 2).

TABLE 2

How cytology and HPV testing compare: Results from the Italian screening trial

| CYTOLOGY/HPV TEST | TOTAL NO. | CIN 2+ |

|---|---|---|

| ≥ASCUS/positive | 300 | 52 (69%) |

| ≥ASCUS/negative | 594 | 2 (3%) |

| Within normal limits/positive | 885 | 21 (28%) |

| Modified from Ronco G et al | ||

The United States is falling behind other countries in assessing how best to utilize HPV testing for screening. Ongoing trials in The Netherlands, Italy, United Kingdom, Canada, and Finland are evaluating whether cytology can be replaced by HPV DNA testing for screening. Currently, HPV testing is only approved as an adjunct to cytology for cervical cancer screening in the United States, and no similar trials are under way.

OCs not linked to HPV infection, and condoms afford some protection

Vaccarella S, Lazcano-Ponce E, Castro-Garduno JA, et al. Prevalence and determinants of human papillomavirus infection in men attending vasectomy clinics in Mexico. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1934–1939.

Vaccarella S, Franceschi S, Herrero R, et al. Sexual behavior, condom use, and human papillomavirus: pooled analysis of the IARC human papillomavirus prevalence surveys. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:326–333.

Winer RL, Hughes JP, Feng Q, et al. Condom use and the risk of genital human papillomavirus infection in young women. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2645–2654.

No question: Anogenital HPV infections are transmitted almost exclusively through intimate sexual contact.3 The standard markers of sexual exposure, such as the number of sexual partners and the number of partners that one’s partner has had, are key risk factors for infection with HPV. Women often ask whether other factors such as oral contraceptive (OC) use, diet, smoking, and condom use affect their risk for infection. But nonsexual risk factors are difficult to evaluate because the strength of sexual risk factors is so high.

To clarify the role played by non-sexual factors, the International Association for Research on Cancer (IARC) pooled data from multiple HPV prevalence studies involving more than 15,000 women from 14 different areas worldwide. This study clearly indicates that the use of OCs is not associated with HPV infection. Current, former, and never users of OCs all had the same risk of being HPV-positive. Therefore, although OCs are a risk factor for cervical cancer, the elevated risk cannot be explained by an increased susceptibility to HPV infection. This study also found that the menopausal transition had no clear effect on HPV infection.

New data show condoms to be more beneficial than not

Condoms are widely recognized as an effective barrier to the sexual transmission of HIV; their efficacy in blocking the transmission of other sexual diseases is less well documented. Most studies that have evaluated the impact of condom use on HPV infection have failed to find a beneficial effect. This may reflect the fact that condoms are often used inconsistently. In addition, there is a tendency to use condoms when having higher-risk sexual encounters, such as with a new partner.

In a recent study from Seattle, Winer and colleagues followed 82 female university students who first initiated sex while enrolled in the study or within 2 weeks of joining the study. The incidence of HPV infection was 38 per 100 patient-years of follow-up among women whose partners used condoms during all acts of intercourse, compared with 89.3 per 100 patient-years of follow-up among women whose partners used condoms less than 5% of the time. Risk reductions were observed for both high- and low-risk types of HPV.

Condoms also appeared to protect against the development of CIN. There were no cases of CIN during 32 patient-years among women whose partners consistently used condoms, compared with 14 cases of incident CIN during 97 patient-years of follow-up among women whose partners did not use condoms or who used them less consistently.

LEEP may have an adverse obstetric impact

Kyrgiou M, Koliopoulos G, Martin-Hirsch P, Arbyn M, Prendiville W, Paraskevaidis E. Obstetric outcomes after conservative treatment for intraepithelial or early invasive cervical lesions: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2006;367:489–498.

Although most clinicians recognize that cold-knife conization has the potential to cause adverse obstetric outcomes, the same has not been recognized for loop electrosurgical excisional procedures (LEEP). In fact, most of the studies published in the early 1990s showed that LEEP had little impact on obstetric outcomes. Now we know better: Kyrgiou and colleagues conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of the published literature on obstetric outcomes after treatment of CIN lesions, and found that all types of excisional procedures produce similar pregnancy-related morbidities.

LEEP had a significant association with preterm delivery (11% risk in treated women versus 7% in untreated women), low-birth-weight infants (8% in treated women versus 4% in untreated women), and premature rupture of membranes (5% in treated women versus 2% in untreated women). Although there were no significant increases in NICU admissions or perinatal mortality among the offspring of women who had undergone LEEP versus those who had not, nonsignificant increases were observed.

Similar increases in pregnancy-related morbidity were not observed among patients who underwent ablative procedures. This suggests that the amount of tissue that is removed during the LEEP (FIGURE 1) is important. Therefore, when treating CIN 2,3 lesions, especially in young women, consider using an ablative method such as cryotherapy or electrofulguration, unless colposcopy is unsatisfactory or there is a colposcopic or pathologic suspicion that an occult cancer is present.

FIGURE 1 CIN 2,3 and its treatment by LEEP

Is liquid-based cytology as sensitive as we thought?

Davey E, Barratt A, Irwig L, et al. Effect of study design and quality on unsatisfactory rates, cytology classifications, and accuracy in liquid-based versus conventional cervical cytology: a systematic review. Lancet. 2006;367:122–132.

Ronco G, Segnan N, Giorgi-Rossi P, et al. Human papillomavirus testing and liquid-based cytology: results at recruitment from the new technologies for cervical cancer randomized controlled trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:765–774.

Taylor S, Kuhn L, Dupree W, Denny L, De Souza M, Wright TC Jr. Direct comparison of liquid-based and conventional cytology in a South African screening trial. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:957–962.

A major reappraisal of liquid-based cytology (LBC) is under way. When it was first introduced, LBC was believed to provide a significant advantage over conventional cervical cytology in terms of sensitivity for CIN 2,3 or cancer. However, most of the studies that compared the 2 modalities had severe methodological problems. Many utilized historical controls, and most others simply reported increases in the number of cases cytologically diagnosed as squamous intraepithelial lesions (SIL). Very few measured histologic endpoints, and the few studies that did failed to blind the pathologists evaluating the histology to the cytologic findings. Only 1 small study was randomized.

Focus on high-quality studies finds lower sensitivity for LBC

Recently, Davey and colleagues conducted a systematic review of the published literature comparing LBC with conventional cytology. A total of 56 studies were evaluated, 52 of which provided enough information to evaluate differences between the 2 methods in the detection of low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL) and high-grade SIL (HSIL). These 52 studies included more than 1.25 million slides.

None of the studies that were evaluated were judged to be of “ideal quality,” and only 5 were judged to be of “high quality.” When all of the studies are taken into account and combined, there appears to be an increase in the cytologic detection of LSIL and HSIL with the use of LBC. However, further evaluation showed marked differences in the results obtained by studies of different quality.

When only “high-quality” studies are analyzed, there is no indication that LBC increases the detection of HSIL. Davey and colleagues concluded that there is no evidence that LBC reduces the proportion of unsatisfactory slides or outperforms conventional cytology in identifying women with CIN 2,3. They also noted that large randomized trials are needed.

Little difference between modalities in randomized trials

After the systematic review was conducted, 2 large trials comparing LBC with conventional cytology were published. In the first trial, Taylor and colleagues collected samples from South African women and analyzed them in blinded fashion in US laboratories. In their carefully controlled study, 5,652 women received either LBC or conventional cytology (rotated on a 6-month basis), and all women underwent colposcopy and cervical biopsy. No significant difference was observed in the sensitivity of LBC and conventional cytology in the detection of CIN 2,3 or cancer. In fact, there was a nonsignificant increase in sensitivity with conventional cytology, compared with LBC. Positive predictive value was lower with LBC than with conventional cytology. This means that a smaller proportion of women with an abnormal result on LBC had CIN 2,3 or cancer identified at colposcopy than did women who had an abnormal result on conventional cytology.

Similarly, in a large trial from Italy, Ronco and colleagues also failed to find LBC to be more sensitive than conventional cytology. Their trial randomized 33,364 women to LBC or conventional cytology. The use of LBC did not increase the detection of CIN 2,3 or cancer, compared with conventional cytology, but did lead to a dramatic reduction (43%) in positive predictive value due to an increase in the number of abnormal samples.

A similar increase in minor cytologic abnormalities with the use of LBC is now well documented in the United States. According to surveys from the College of American Pathologists, the median percentile reporting rate of LSIL in US laboratories in 2003 was 1.4% for conventional cytology specimens and 2.4% for liquid-based specimens.1

Taken together (TABLE 3), these studies suggest that LBC has no greater sensitivity than conventional cytology and therefore does not solve the problems associated with the poor sensitivity of cervical cytology. However, LBC does have other advantages, the greatest being the availability of residual fluid for “reflex” HPV testing in women with ASC-US and for testing for other pathogens, such as Chlamydia.

TABLE 3

When conventional and liquid-based cytology are compared, the latter isn’t more sensitive

| STUDY | NO. WOMEN | CONVENTIONAL CYTOLOGY | LIQUID-BASED CYTOLOGY | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SENSITIVITY* | PPV* | SENSITIVITY* | PPV* | ||

| Taylor et al | 5,652 | 84%† | 11.4 | 71% | 9.4 |

| Ronco et al | 33,364 | 70% | 11.4 | 74%† | 6.5 |

| PPV=positive predictive value | |||||

| *for detection of CIN 2,3 or cancer | |||||

| †Nonsignificant | |||||

Most cytologists find it easier to evaluate LBC specimens than conventional cytology specimens. Nor is it likely that cytology laboratories will want to switch back to conventional cytology now that the conversion to LBC has taken place.

Dr. Wright reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article.

The year 2006 was a busy one for those of us engaged in cervical cancer prevention. The most notable development was approval by the US Food and Drug Administration of the human papillomavirus (HPV) quadrivalent vaccine in June, followed closely by guidelines for its use from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (June) and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (September). Key issues related to the introduction of the HPV vaccine into clinical practice were reviewed in a roundtable discussion in the January 2007 issue of OBG Management.

Therefore, this update will depart, for the moment, from matters related to the vaccine and concentrate on several other critical areas:

- Testing for high-risk HPV types is useful. Large European cervical cancer screening trials confirm a benefit.

- Condoms and oral contraceptives—are they risk modifiers for HPV infection? Answers (“Yes” and “No,” respectively) come from new data.

- Loop electrosurgical excision carries obstetric risks. In fact, all types of excisional procedures produce similar pregnancy-related morbidity.

- Liquid-based cytology may not be superior to conventional cytology. So suggest new studies and a systematic review of the literature.

HPV testing outperforms cytology for screening

Cuzick J, Clavel C, Petry KU, et al. Overview of the European and North American studies on HPV testing in primary cervical cancer screening. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1095–1101.

Ronco G, Segnan N, Giorgi-Rossi P, et al. Human papillomavirus testing and liquid-based cytology: results at recruitment from the new technologies for cervical cancer randomized controlled trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:765–774.