User login

How best to engage patients in their psychiatric care

Providing patients and their families with information and education about their psychiatric illness is a central tenet of mental health care. Discussions about diagnostic impressions, treatment options, and the risks and benefits of interventions are customary. Additionally, patients and families often receive written material or referral to other information sources, including self-help books and a growing number of online resources. Although patient education remains a useful and expected element of good care, there is evidence that, alone, it is insufficient to change health behaviors.1

A growing body of literature and clinical experience suggests that self-management strategies complement patient education and improve treatment outcomes for patients with chronic illnesses, including psychiatric conditions.2,3 The Cochrane Collaboration describes patient education as “teaching or training of patients concerning their own health needs,” and self-management as “the individual’s ability to manage the symptoms, treatment, physical and psychosocial consequences and lifestyle changes inherent in living with a long-term disorder.”4

In this article, we review:

• characteristics of long-term care models

• literature supporting the benefits of self-management programs

• clinical initiatives illustrating important elements of self-management support

• opportunities and challenges faced by clinicians, patients, families, clinics, and healthcare systems implementing self-management programs.

Principles of self-management

Chronic care models must account for conditions in which the clinical course can be variable, that are not amenable to a cure, and that demand long-term treatment. Optimal health outcomes rely on patients accurately monitoring, reporting, and responding to their symptoms, while engaging in critical health-related behaviors. In addition, clinicians must teach, partner with, and motivate patients to engage in crucial disease-management activities. Although typically not considered in this light, we believe most psychiatric disorders are best approached through a long-term care model, and benefit from self-management principles.

Basics of self-management include:

• patients must formulate goals and learn skills relevant to their disease

• problems are patient-selected and targeted with individualized, flexible treatment plans.

Corbin and Strauss believe effective “self-managers” achieve competency in three areas:

• role management, which entails healthy adjustments to changes in role

responsibilities, expectations, and self-identity

• emotional management, which often is particularly challenging in psychiatric conditions because of the emotional disruption inherent in living with a psychiatric illness.6

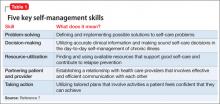

Proficiency in these three “self-manager” domains is enhanced by mastering five key self-management skills outlined in Table 1.7

Successful intervention programs vary widely with regard to individual vs group formats, communication interface, and involved health professionals. However, evidence indicates that problem solving, decision making, and action planning are key components.7 Successful planning includes:

• detailed descriptions of what, how, when, and where the activity will be accomplished

• assessment of patient confidence and adjustment of plans if confidence is limited

• continuous monitoring and self-tailoring of plans through collaborative discussions with providers, fostering a spirit of partnership and ownership.

Table 2 illustrates elements of successful action plans in our Action Planning Worksheet. Adapted from the work of Scharzer,8 Prochaska,9 and Clark,10 we developed this self-management tool for individual and group treatment settings. It serves as a vehicle for collaborative patient-provider discussion and planning. The nuts-and-bolts nature of the discussions inevitably leads to learning new, important, and often unexpected information about our patients’ daily lives and the challenges they face as they share their dominant priorities, fears, and insecurities.

Patients provide consistently positive feedback about action planning, and clinicians often find that the process reveals fruitful areas for further psychotherapeutic intervention. Examples include identifying a range of negative automatic thoughts or catastrophic thinking impeding initiation of important activation, and exposure activities for depressed or anxious patients.

Knowing what to do is different than actually doing it. Changing behavior is difficult in the best circumstances, let alone with the strain of a chronic illness. It is critical to recognize that the presence of depressive symptoms significantly reduces the likelihood that patients will employ self-management practices.11 When combined with anxiety and the impairment of motivation and executive functioning that is common in psychiatric conditions, it is not surprising that patients with a mental health condition struggle to embrace ownership of their illness and engage in critical health behaviors—which may include adhering to medication regimens; maintaining a healthy sleep cycle, nutrition, and exercise routines; vigilant symptom surveillance; and carrying out an agreed-upon action plan.

Interventions

Professionally-guided “light-touch” interventions and technology-assisted self-management interventions also can improve patient engagement in activities through individual encounters, group forums, and technology-mediated exchanges, including telephone, email, text message, tele-health, and web-based interventions.13 The DE-STRESS (Delivery of Self Training and Education for Stressful Situations) model illustrates these principles. This 8-week program combines elements of face-to-face, email, telephone, and web-based assignments and exchanges, and demonstrates a decline in posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety scores.14 Our Michigan Depression Outreach and Collaborative Care program is another example of a self-management intervention (Box 1).

• modeling and social persuasion through having patients observe and engage others as they struggle to overcome similar obstacles

• re-interpretation of symptoms aimed at fostering the belief that symptoms generally are multi-determined with several potential explanations, and vary with daily routines.

Helping patients understand when common symptoms such as impaired concentration or dizziness should be “watched”—rather than responded to aggressively—is crucial for effective long-term management.

Challenges

Health care delivery and medical educational models have been slow to embrace this change to long-term care models because doing so involves what might be uncomfortable shifts in roles and responsibilities. Effective care for long-term illness necessitates that the patient become an expert on his (her) illness, and be an active participant and partner in their treatment. Preparing health professionals for this new role as teacher, mentor, and collaborator presents a challenge to health care systems and educational programs across disciplines.

When trying to facilitate effective patient-provider partnerships, it is important to recognize the variability in patient preference for what and how information is shared, how decisions are made, and the role patients are asked to play in their care. Patients differ in their desire for an active or collaborative shared-decision model; some prefer more directive provider communication and a passive role.18 Preferences are influenced by variables such as age, sex, race, anxiety level, and education.19 Open discussion of these matters between caregivers and patients is important; studies have shown that failure to address these issues of “fit” can

impede communication, healthy behavior, and positive outcomes.

Bottom Line

Emerging care models demand that health care providers become teachers and motivators to help patients develop and implement patterns of health surveillance and intervention that will optimize their well-being and functionality. As active collaborators in their care, patients form a partnership with their care teams, allowing for regular, reciprocal exchange of information and shared decision-making. This shift to a partnership creates new, exciting roles and responsibilities for all parties.

Related Resources

- Improving Chronic Illness Care. www.improvingchroniccare.org.

- Chronic disease self-management program (Better Choices, Better Health workshop). Stanford School of Medicine. http://patienteducation.stanford.edu/programs/cdsmp.html.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Featured Audio

Thomas E. Fluent, MD, talks about addressing patient resistance to a self-management model of care. Dr. Fluent is Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

1. Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, et al. Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA. 2002;288(19):2469-2475.

2. Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model, part 2. JAMA. 2002;288(15):1909-1914.

3. Druss BG, Zhao L, von Esenwein SA, et al. The Health and Recovery Peer (HARP) Program: a peer-led intervention to improve medical self-management for persons with serious mental illness. Schizophr Res. 2010;118(1-3):264-270.

4. Tomkins S, Collins A. Promoting optimal self-care: consultation techniques that improve quality of life for patients and clinicians. London, United Kingdom: National Health Service; 2005.

5. Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996;74(4):511-544.

6. Corbin JM, Strauss AL. Unending work and care : managing chronic illness at home. 1st ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1988.

7. Lorig KR, Holman H. Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26(1):1-7.

8. Schwarzer R. Social-cognitive factors in changing health-related behaviors. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2001;10(2):47-51.

9. Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. In search of how people change: Applications to addictive behaviors. Am Psycholt. 1992;47(9):1102-1114.

10. Clark NM, Gong M, Kaciroti N. A model of self-regulation for control of chronic disease. Health Educ Behav. 2001; 28(6):769-782.

11. Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stock R, et al. Do increases in patient activation result in improved self-management behaviors? Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1443-1463.

12. Lundahl B, Burke BL. The effectiveness and applicability of motivational interviewing: a practice-friendly review of four meta-analyses. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65(11):

1232-1245.

13. Tumur I, Kaltenthaler E, Ferriter M, et al. Computerised cognitive behaviour therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a systematic review. Psychother Psychosom. 2007; 76(4):196-202.

14. Litz BT, Engel CC, Bryant RA, et al. A randomized, controlled proof-of-concept trial of an Internet-based, therapist-assisted self-management treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(11):1676-1683.

15. Holman H, Lorig K. Patient self-management: a key to effectiveness and efficiency in care of chronic disease. Public Health Rep. 2004;119(3):239-243.

16. Williams A, Hagerty BM, Brasington SJ, et al. Stress Gym: feasibility of deploying a web-enhanced behavioral self-management program for stress in a military setting. Mil Med. 2010;175(7):487-493.

17. Woltmann E, Grogan-Kaylor A, Perron B, et al. Comparative effectiveness of collaborative chronic care models for mental health conditions across primary, specialty, and behavioral health care settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(8):790-804.

18. Davison BJ, Breckon E. Factors influencing treatment decision making and information p of prostate cancer patients on active surveillance. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;87(3):369-374.

19. Chewning B, Bylund CL, Shah B, et al. Patient p for shared decisions: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(1):9-18.

Providing patients and their families with information and education about their psychiatric illness is a central tenet of mental health care. Discussions about diagnostic impressions, treatment options, and the risks and benefits of interventions are customary. Additionally, patients and families often receive written material or referral to other information sources, including self-help books and a growing number of online resources. Although patient education remains a useful and expected element of good care, there is evidence that, alone, it is insufficient to change health behaviors.1

A growing body of literature and clinical experience suggests that self-management strategies complement patient education and improve treatment outcomes for patients with chronic illnesses, including psychiatric conditions.2,3 The Cochrane Collaboration describes patient education as “teaching or training of patients concerning their own health needs,” and self-management as “the individual’s ability to manage the symptoms, treatment, physical and psychosocial consequences and lifestyle changes inherent in living with a long-term disorder.”4

In this article, we review:

• characteristics of long-term care models

• literature supporting the benefits of self-management programs

• clinical initiatives illustrating important elements of self-management support

• opportunities and challenges faced by clinicians, patients, families, clinics, and healthcare systems implementing self-management programs.

Principles of self-management

Chronic care models must account for conditions in which the clinical course can be variable, that are not amenable to a cure, and that demand long-term treatment. Optimal health outcomes rely on patients accurately monitoring, reporting, and responding to their symptoms, while engaging in critical health-related behaviors. In addition, clinicians must teach, partner with, and motivate patients to engage in crucial disease-management activities. Although typically not considered in this light, we believe most psychiatric disorders are best approached through a long-term care model, and benefit from self-management principles.

Basics of self-management include:

• patients must formulate goals and learn skills relevant to their disease

• problems are patient-selected and targeted with individualized, flexible treatment plans.

Corbin and Strauss believe effective “self-managers” achieve competency in three areas:

• role management, which entails healthy adjustments to changes in role

responsibilities, expectations, and self-identity

• emotional management, which often is particularly challenging in psychiatric conditions because of the emotional disruption inherent in living with a psychiatric illness.6

Proficiency in these three “self-manager” domains is enhanced by mastering five key self-management skills outlined in Table 1.7

Successful intervention programs vary widely with regard to individual vs group formats, communication interface, and involved health professionals. However, evidence indicates that problem solving, decision making, and action planning are key components.7 Successful planning includes:

• detailed descriptions of what, how, when, and where the activity will be accomplished

• assessment of patient confidence and adjustment of plans if confidence is limited

• continuous monitoring and self-tailoring of plans through collaborative discussions with providers, fostering a spirit of partnership and ownership.

Table 2 illustrates elements of successful action plans in our Action Planning Worksheet. Adapted from the work of Scharzer,8 Prochaska,9 and Clark,10 we developed this self-management tool for individual and group treatment settings. It serves as a vehicle for collaborative patient-provider discussion and planning. The nuts-and-bolts nature of the discussions inevitably leads to learning new, important, and often unexpected information about our patients’ daily lives and the challenges they face as they share their dominant priorities, fears, and insecurities.

Patients provide consistently positive feedback about action planning, and clinicians often find that the process reveals fruitful areas for further psychotherapeutic intervention. Examples include identifying a range of negative automatic thoughts or catastrophic thinking impeding initiation of important activation, and exposure activities for depressed or anxious patients.

Knowing what to do is different than actually doing it. Changing behavior is difficult in the best circumstances, let alone with the strain of a chronic illness. It is critical to recognize that the presence of depressive symptoms significantly reduces the likelihood that patients will employ self-management practices.11 When combined with anxiety and the impairment of motivation and executive functioning that is common in psychiatric conditions, it is not surprising that patients with a mental health condition struggle to embrace ownership of their illness and engage in critical health behaviors—which may include adhering to medication regimens; maintaining a healthy sleep cycle, nutrition, and exercise routines; vigilant symptom surveillance; and carrying out an agreed-upon action plan.

Interventions

Professionally-guided “light-touch” interventions and technology-assisted self-management interventions also can improve patient engagement in activities through individual encounters, group forums, and technology-mediated exchanges, including telephone, email, text message, tele-health, and web-based interventions.13 The DE-STRESS (Delivery of Self Training and Education for Stressful Situations) model illustrates these principles. This 8-week program combines elements of face-to-face, email, telephone, and web-based assignments and exchanges, and demonstrates a decline in posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety scores.14 Our Michigan Depression Outreach and Collaborative Care program is another example of a self-management intervention (Box 1).

• modeling and social persuasion through having patients observe and engage others as they struggle to overcome similar obstacles

• re-interpretation of symptoms aimed at fostering the belief that symptoms generally are multi-determined with several potential explanations, and vary with daily routines.

Helping patients understand when common symptoms such as impaired concentration or dizziness should be “watched”—rather than responded to aggressively—is crucial for effective long-term management.

Challenges

Health care delivery and medical educational models have been slow to embrace this change to long-term care models because doing so involves what might be uncomfortable shifts in roles and responsibilities. Effective care for long-term illness necessitates that the patient become an expert on his (her) illness, and be an active participant and partner in their treatment. Preparing health professionals for this new role as teacher, mentor, and collaborator presents a challenge to health care systems and educational programs across disciplines.

When trying to facilitate effective patient-provider partnerships, it is important to recognize the variability in patient preference for what and how information is shared, how decisions are made, and the role patients are asked to play in their care. Patients differ in their desire for an active or collaborative shared-decision model; some prefer more directive provider communication and a passive role.18 Preferences are influenced by variables such as age, sex, race, anxiety level, and education.19 Open discussion of these matters between caregivers and patients is important; studies have shown that failure to address these issues of “fit” can

impede communication, healthy behavior, and positive outcomes.

Bottom Line

Emerging care models demand that health care providers become teachers and motivators to help patients develop and implement patterns of health surveillance and intervention that will optimize their well-being and functionality. As active collaborators in their care, patients form a partnership with their care teams, allowing for regular, reciprocal exchange of information and shared decision-making. This shift to a partnership creates new, exciting roles and responsibilities for all parties.

Related Resources

- Improving Chronic Illness Care. www.improvingchroniccare.org.

- Chronic disease self-management program (Better Choices, Better Health workshop). Stanford School of Medicine. http://patienteducation.stanford.edu/programs/cdsmp.html.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Featured Audio

Thomas E. Fluent, MD, talks about addressing patient resistance to a self-management model of care. Dr. Fluent is Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Providing patients and their families with information and education about their psychiatric illness is a central tenet of mental health care. Discussions about diagnostic impressions, treatment options, and the risks and benefits of interventions are customary. Additionally, patients and families often receive written material or referral to other information sources, including self-help books and a growing number of online resources. Although patient education remains a useful and expected element of good care, there is evidence that, alone, it is insufficient to change health behaviors.1

A growing body of literature and clinical experience suggests that self-management strategies complement patient education and improve treatment outcomes for patients with chronic illnesses, including psychiatric conditions.2,3 The Cochrane Collaboration describes patient education as “teaching or training of patients concerning their own health needs,” and self-management as “the individual’s ability to manage the symptoms, treatment, physical and psychosocial consequences and lifestyle changes inherent in living with a long-term disorder.”4

In this article, we review:

• characteristics of long-term care models

• literature supporting the benefits of self-management programs

• clinical initiatives illustrating important elements of self-management support

• opportunities and challenges faced by clinicians, patients, families, clinics, and healthcare systems implementing self-management programs.

Principles of self-management

Chronic care models must account for conditions in which the clinical course can be variable, that are not amenable to a cure, and that demand long-term treatment. Optimal health outcomes rely on patients accurately monitoring, reporting, and responding to their symptoms, while engaging in critical health-related behaviors. In addition, clinicians must teach, partner with, and motivate patients to engage in crucial disease-management activities. Although typically not considered in this light, we believe most psychiatric disorders are best approached through a long-term care model, and benefit from self-management principles.

Basics of self-management include:

• patients must formulate goals and learn skills relevant to their disease

• problems are patient-selected and targeted with individualized, flexible treatment plans.

Corbin and Strauss believe effective “self-managers” achieve competency in three areas:

• role management, which entails healthy adjustments to changes in role

responsibilities, expectations, and self-identity

• emotional management, which often is particularly challenging in psychiatric conditions because of the emotional disruption inherent in living with a psychiatric illness.6

Proficiency in these three “self-manager” domains is enhanced by mastering five key self-management skills outlined in Table 1.7

Successful intervention programs vary widely with regard to individual vs group formats, communication interface, and involved health professionals. However, evidence indicates that problem solving, decision making, and action planning are key components.7 Successful planning includes:

• detailed descriptions of what, how, when, and where the activity will be accomplished

• assessment of patient confidence and adjustment of plans if confidence is limited

• continuous monitoring and self-tailoring of plans through collaborative discussions with providers, fostering a spirit of partnership and ownership.

Table 2 illustrates elements of successful action plans in our Action Planning Worksheet. Adapted from the work of Scharzer,8 Prochaska,9 and Clark,10 we developed this self-management tool for individual and group treatment settings. It serves as a vehicle for collaborative patient-provider discussion and planning. The nuts-and-bolts nature of the discussions inevitably leads to learning new, important, and often unexpected information about our patients’ daily lives and the challenges they face as they share their dominant priorities, fears, and insecurities.

Patients provide consistently positive feedback about action planning, and clinicians often find that the process reveals fruitful areas for further psychotherapeutic intervention. Examples include identifying a range of negative automatic thoughts or catastrophic thinking impeding initiation of important activation, and exposure activities for depressed or anxious patients.

Knowing what to do is different than actually doing it. Changing behavior is difficult in the best circumstances, let alone with the strain of a chronic illness. It is critical to recognize that the presence of depressive symptoms significantly reduces the likelihood that patients will employ self-management practices.11 When combined with anxiety and the impairment of motivation and executive functioning that is common in psychiatric conditions, it is not surprising that patients with a mental health condition struggle to embrace ownership of their illness and engage in critical health behaviors—which may include adhering to medication regimens; maintaining a healthy sleep cycle, nutrition, and exercise routines; vigilant symptom surveillance; and carrying out an agreed-upon action plan.

Interventions

Professionally-guided “light-touch” interventions and technology-assisted self-management interventions also can improve patient engagement in activities through individual encounters, group forums, and technology-mediated exchanges, including telephone, email, text message, tele-health, and web-based interventions.13 The DE-STRESS (Delivery of Self Training and Education for Stressful Situations) model illustrates these principles. This 8-week program combines elements of face-to-face, email, telephone, and web-based assignments and exchanges, and demonstrates a decline in posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety scores.14 Our Michigan Depression Outreach and Collaborative Care program is another example of a self-management intervention (Box 1).

• modeling and social persuasion through having patients observe and engage others as they struggle to overcome similar obstacles

• re-interpretation of symptoms aimed at fostering the belief that symptoms generally are multi-determined with several potential explanations, and vary with daily routines.

Helping patients understand when common symptoms such as impaired concentration or dizziness should be “watched”—rather than responded to aggressively—is crucial for effective long-term management.

Challenges

Health care delivery and medical educational models have been slow to embrace this change to long-term care models because doing so involves what might be uncomfortable shifts in roles and responsibilities. Effective care for long-term illness necessitates that the patient become an expert on his (her) illness, and be an active participant and partner in their treatment. Preparing health professionals for this new role as teacher, mentor, and collaborator presents a challenge to health care systems and educational programs across disciplines.

When trying to facilitate effective patient-provider partnerships, it is important to recognize the variability in patient preference for what and how information is shared, how decisions are made, and the role patients are asked to play in their care. Patients differ in their desire for an active or collaborative shared-decision model; some prefer more directive provider communication and a passive role.18 Preferences are influenced by variables such as age, sex, race, anxiety level, and education.19 Open discussion of these matters between caregivers and patients is important; studies have shown that failure to address these issues of “fit” can

impede communication, healthy behavior, and positive outcomes.

Bottom Line

Emerging care models demand that health care providers become teachers and motivators to help patients develop and implement patterns of health surveillance and intervention that will optimize their well-being and functionality. As active collaborators in their care, patients form a partnership with their care teams, allowing for regular, reciprocal exchange of information and shared decision-making. This shift to a partnership creates new, exciting roles and responsibilities for all parties.

Related Resources

- Improving Chronic Illness Care. www.improvingchroniccare.org.

- Chronic disease self-management program (Better Choices, Better Health workshop). Stanford School of Medicine. http://patienteducation.stanford.edu/programs/cdsmp.html.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Featured Audio

Thomas E. Fluent, MD, talks about addressing patient resistance to a self-management model of care. Dr. Fluent is Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

1. Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, et al. Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA. 2002;288(19):2469-2475.

2. Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model, part 2. JAMA. 2002;288(15):1909-1914.

3. Druss BG, Zhao L, von Esenwein SA, et al. The Health and Recovery Peer (HARP) Program: a peer-led intervention to improve medical self-management for persons with serious mental illness. Schizophr Res. 2010;118(1-3):264-270.

4. Tomkins S, Collins A. Promoting optimal self-care: consultation techniques that improve quality of life for patients and clinicians. London, United Kingdom: National Health Service; 2005.

5. Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996;74(4):511-544.

6. Corbin JM, Strauss AL. Unending work and care : managing chronic illness at home. 1st ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1988.

7. Lorig KR, Holman H. Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26(1):1-7.

8. Schwarzer R. Social-cognitive factors in changing health-related behaviors. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2001;10(2):47-51.

9. Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. In search of how people change: Applications to addictive behaviors. Am Psycholt. 1992;47(9):1102-1114.

10. Clark NM, Gong M, Kaciroti N. A model of self-regulation for control of chronic disease. Health Educ Behav. 2001; 28(6):769-782.

11. Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stock R, et al. Do increases in patient activation result in improved self-management behaviors? Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1443-1463.

12. Lundahl B, Burke BL. The effectiveness and applicability of motivational interviewing: a practice-friendly review of four meta-analyses. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65(11):

1232-1245.

13. Tumur I, Kaltenthaler E, Ferriter M, et al. Computerised cognitive behaviour therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a systematic review. Psychother Psychosom. 2007; 76(4):196-202.

14. Litz BT, Engel CC, Bryant RA, et al. A randomized, controlled proof-of-concept trial of an Internet-based, therapist-assisted self-management treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(11):1676-1683.

15. Holman H, Lorig K. Patient self-management: a key to effectiveness and efficiency in care of chronic disease. Public Health Rep. 2004;119(3):239-243.

16. Williams A, Hagerty BM, Brasington SJ, et al. Stress Gym: feasibility of deploying a web-enhanced behavioral self-management program for stress in a military setting. Mil Med. 2010;175(7):487-493.

17. Woltmann E, Grogan-Kaylor A, Perron B, et al. Comparative effectiveness of collaborative chronic care models for mental health conditions across primary, specialty, and behavioral health care settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(8):790-804.

18. Davison BJ, Breckon E. Factors influencing treatment decision making and information p of prostate cancer patients on active surveillance. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;87(3):369-374.

19. Chewning B, Bylund CL, Shah B, et al. Patient p for shared decisions: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(1):9-18.

1. Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, et al. Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA. 2002;288(19):2469-2475.

2. Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model, part 2. JAMA. 2002;288(15):1909-1914.

3. Druss BG, Zhao L, von Esenwein SA, et al. The Health and Recovery Peer (HARP) Program: a peer-led intervention to improve medical self-management for persons with serious mental illness. Schizophr Res. 2010;118(1-3):264-270.

4. Tomkins S, Collins A. Promoting optimal self-care: consultation techniques that improve quality of life for patients and clinicians. London, United Kingdom: National Health Service; 2005.

5. Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996;74(4):511-544.

6. Corbin JM, Strauss AL. Unending work and care : managing chronic illness at home. 1st ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1988.

7. Lorig KR, Holman H. Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26(1):1-7.

8. Schwarzer R. Social-cognitive factors in changing health-related behaviors. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2001;10(2):47-51.

9. Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. In search of how people change: Applications to addictive behaviors. Am Psycholt. 1992;47(9):1102-1114.

10. Clark NM, Gong M, Kaciroti N. A model of self-regulation for control of chronic disease. Health Educ Behav. 2001; 28(6):769-782.

11. Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stock R, et al. Do increases in patient activation result in improved self-management behaviors? Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1443-1463.

12. Lundahl B, Burke BL. The effectiveness and applicability of motivational interviewing: a practice-friendly review of four meta-analyses. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65(11):

1232-1245.

13. Tumur I, Kaltenthaler E, Ferriter M, et al. Computerised cognitive behaviour therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a systematic review. Psychother Psychosom. 2007; 76(4):196-202.

14. Litz BT, Engel CC, Bryant RA, et al. A randomized, controlled proof-of-concept trial of an Internet-based, therapist-assisted self-management treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(11):1676-1683.

15. Holman H, Lorig K. Patient self-management: a key to effectiveness and efficiency in care of chronic disease. Public Health Rep. 2004;119(3):239-243.

16. Williams A, Hagerty BM, Brasington SJ, et al. Stress Gym: feasibility of deploying a web-enhanced behavioral self-management program for stress in a military setting. Mil Med. 2010;175(7):487-493.

17. Woltmann E, Grogan-Kaylor A, Perron B, et al. Comparative effectiveness of collaborative chronic care models for mental health conditions across primary, specialty, and behavioral health care settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(8):790-804.

18. Davison BJ, Breckon E. Factors influencing treatment decision making and information p of prostate cancer patients on active surveillance. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;87(3):369-374.

19. Chewning B, Bylund CL, Shah B, et al. Patient p for shared decisions: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(1):9-18.